“Don’t you wish sometimes that writing were just like sports? That you could just go out there and see who’d win? See who’s better. Measurably. With all the stats.”

—DUB TRAYNOR IN THE INFORMATION BY MARTIN AMIS

When I was a ten-year-old I wrote a series of eight superhero “books,” each taking up between 40 to 100 handwritten pages. There were two protagonists, one of whom was named Bubonic Boben Blaster after myself (Bubonic Boben Blaster). He was like me in every way except for his one superpower: the ability to infect his enemies with the bubonic plague.

It was bad.

Here’s a passage (bolded for emphasis):

Then Bubonic Boben Blaster took over control of the airplane. Then he kept flying until he saw grass and he put the plane on autoland. Then Bubonic Boben Blaster helped everyone jump off the plane with their luggage. No one knew where they were. Then Bubonic Boben Blaster looked at a map and saw they were in South Carolina.

I remember the day in the year 2000 when I read this page to my fourth-grade class. Of all the possible feedback a teacher could have offered up after that passage, I was told: “Do not start two sentences in a row with the same word.”

For years this advice stuck with me, and it became a simple rule that I followed in essays. Changing the first word around was a surefire way to make sure consecutive sentences did not have identical structure. Many writing guides offer the same advice.

But if you’re not a ten-year-old with weak control of the written word, it’s clear that repeated words can have strong rhetorical power. While the recurring Then in my own childhood writing is cringeworthy, in other cases repetition has a clear rhetorical purpose. Consider the famous line below, from one of Winston Churchill’s World War II speeches.

We shall go on to the end . . . . We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender. . . .

The repetition is what makes it memorable. When done well such repetition allows for a sense of rhythm and power. Here’s a literary example from Charles Dickens’s Hard Times with the repeated sentence beginnings in bold.

He was a rich man: banker, merchant, manufacturer, and what not. A big, loud man, with a stare, and a metallic laugh. A man made out of a coarse material, which seemed to have been stretched to make so much of him. A man with a great puffed head and forehead, swelled veins in his temples, and such a strained skin to his face that it seemed to hold his eyes open, and lift his eyebrows up. A man with a pervading appearance on him of being inflated like a balloon, and ready to start. A man who could never sufficiently vaunt himself a self-made man. A man who was always proclaiming, through that brassy speaking-trumpet of a voice of his, his old ignorance and his old poverty. A man who was the Bully of humility.

The technical term for this device—repeating a word or phrase at the beginning of consecutive sentences—is anaphora. And Dickens is the master. You may be familiar with the opening to A Tale of Two Cities—“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times . . .”—which is one of the most memorable examples of anaphora in all of English literature. His longest string of sentences starting with the same word lasts 26 sentences in a row, all starting with when in his novel A Haunted Man.

So far, this book has been filled with big-picture perspectives on whole genres and collections of authors, deep dives into overlooked but universal elements such as word frequencies and sentence lengths. But sometimes the unique quirks, whether they be special words or literary devices, are what make a reader remember an author’s voice. Data can shed light on these smaller questions as well. There are rules for writing, but every good rule has been broken by a good author. Anaphora is one of those rules.

In this chapter I’ll be looking at writers’ eccentricities. In honor of Dickens and the opening of A Tale of Two Cities, I’ll start by presenting a data-driven case study on anaphora: a tale of two columnists.

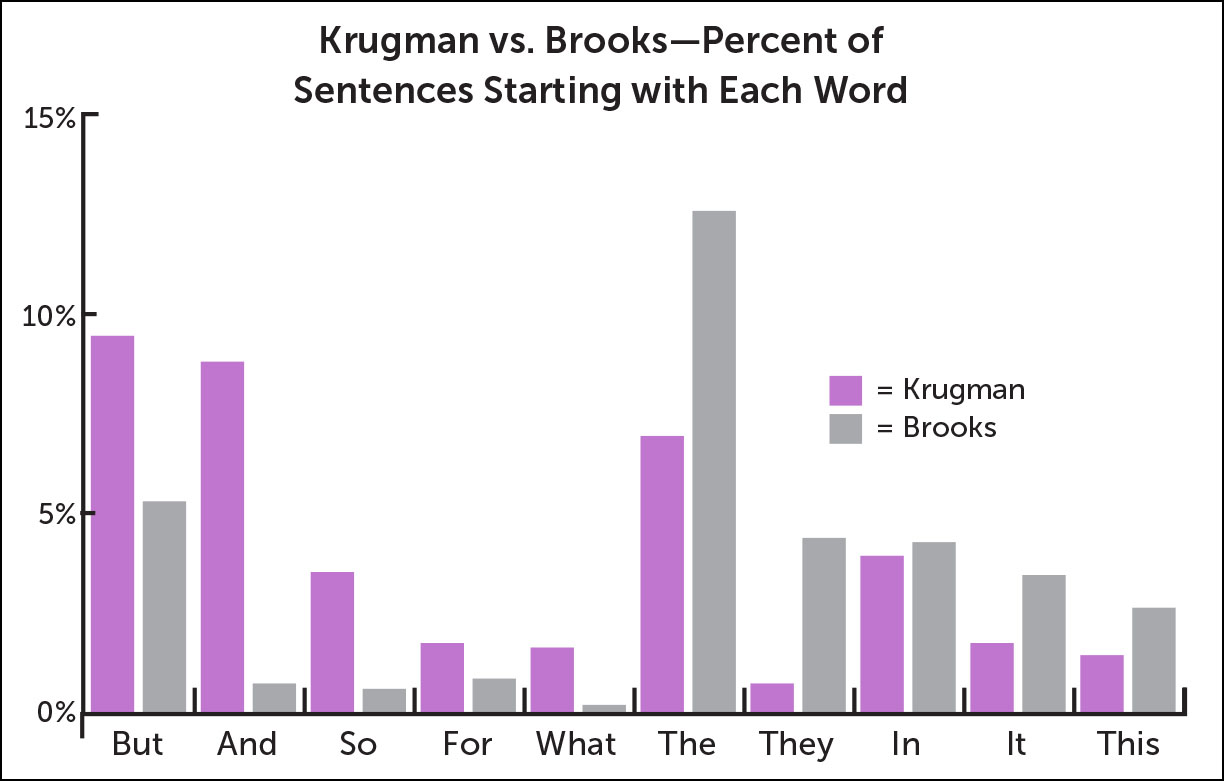

Paul Krugman is a left-leaning professor and Nobel Prize winner. David Brooks is a right-leaning journalist and author of several books. Both are noted for their opinion columns in the New York Times.

I collected the most recent year’s worth of opinion columns from both Krugman and Brooks. Next time you read one of Brooks’s columns, keep your eyes open for anaphora. In 91 out of all 93 David Brooks columns from that year-long period, he had at least two sentences in a row that started with the same word. It’s rare for Brooks not to employ anaphora in some form. Here’s the start of one of his columns, a short but pointed example: Some people like to keep a journal. Some people think it’s a bad idea.

Or consider these six consecutive sentences that all start off with the same four words:

It used to be that senators didn’t go out campaigning against one another. It used to be they didn’t filibuster except in rare circumstances. It used to be they didn’t block presidential nominations routinely.

It used to be that presidents didn’t push the limits of executive authority by redefining the residency status of millions of people without congressional approval. It used to be that presidents didn’t go out negotiating arms control treaties in a way that doesn’t require Senate ratification. It used to be that senators didn’t write letters to hostile nations while their own president was negotiating with them.

In total 9 % of all Brooks sentences start with the same word as the previous sentence. This is a rough metric for anaphora, but an informative one. In contrast to Brooks, only 2 % of Krugman’s sentences fall into that criterion.

While over 95 % of all Brooks columns had at least one example of anaphora, less than half of Krugman opinion columns did. It’s not like Krugman and his editor avoid anaphora like the (bubonic) plague, but it’s rare. When he does start off consecutive sentences with the same word it’s rarely the rhetorical choice that it is for Brooks.

If I were to offer my own reaching theory as to why Krugman shies away from the strong rhetoric it would be from his academic background. In a need to be comprehensive, he hedges, negotiates, and qualifies all his points. The most common words that Krugman and Brooks use to start their sentences offer evidence of this theory.

David Brooks uses the as his most frequent sentence starter. This is to be expected. Though sometimes bested by he, she, or I in literature, the is almost always the most common sentence lead across writing. Pronouns aside, it’s hard to think of any other word that could top the. Brooks uses the more than twice as often to start sentences as any other individual word.

But what about Krugman? He starts more sentences with but than the. The conjunction but, a word that indicates the writer is about to say something to undermine or qualify a previous statement in some way, is Krugman’s favorite way to start a sentence. While Brooks uses the twice as often as but to start a sentence, Krugman uses but a full 33 % more often than the.

And in the most common three-word sentence openings found in Krugman and Brooks columns, we see Krugman clarifying and chaining his sentences while Brooks favors a more direct approach.

KRUGMAN |

BROOKS |

It’s true that |

Over the past |

At this point |

Most of us |

Which brings me |

If you are |

The point is |

You have to |

As a result |

It is a |

The truth is |

This is the |

As I said |

In X % of |

On the contrary |

On the other |

One answer is |

The people who |

The answer is |

In the first |

Krugman’s affinity for But or So might be part of the reason he cannot use anaphora. There are not many ways to begin consecutive sentences with But without devolving into a tangle of contradictions. On the other hand, Brooks is often guided by larger philosophical arguments, where rhetoric is a crucial element for getting his point across.

When Kurt Vonnegut died in 2007 Time magazine author Lev Grossman started off his eulogy of the novelist with this: The proper length for an obituary for Kurt Vonnegut is three words: “So it goes.”

“So it goes” is a refrain used by the narrator in Slaughterhouse-Five. Vonnegut uses it to tell us that someone is dying, and it also serves as a transition between stories. It is so integral to the author’s most famous novel that the expression has lived a life of its own, as seen in Vonnegut’s obituaries and the title of Vonnegut’s biography by Charles J. Shields.

From a literary point of view the repetition of “So it goes” helps set the tone of the entire story. But the phrase also has a unique property from a mathematical point of view: With 106 uses, it is the most frequent sentence in all of Vonnegut’s novels.

And in my survey of all fifty authors, no other sentence is used as often in a single work. In fact, no other sentence comes close. By my count the second-place sentence comes in at just 35 uses. That sentence? “And so on.” This is used by Vonnegut again in his novel Breakfast of Champions to similar effect.

At more than 100 uses, “So it goes” represents a measurable portion of the entirety of Slaughterhouse-Five. It accounts for 2.5 % of the sentences in the entire book—about one out of every forty.

The repetition of “So it goes” in Slaughterhouse-Five is different from the anaphora discussed above. It’s not a phrase that’s used to open consecutive sentences. However, it is emblematic of Vonnegut’s approach to writing. He used repetition and anaphora often. More than 12 % of all sentences in Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five start with the same word as the previous sentence. Among all the classic and popular novels surveyed, this ranks toward the top.

On the following page the top ten books are ranked when looking at this very basic approximation of anaphora—the percentage of sentences that begin with the same word as the previous sentence.

Most of these names should not surprise you. Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is an experimental novel written in soliloquies. In his book Survivor, Chuck Palahniuk writes: “There are only patterns, patterns on top of patterns, patterns that affect other patterns. Patterns hidden by patterns. Patterns within patterns.” It’s no surprise to see some of his work near the top of this list.

BOOK |

AUTHOR |

ANAPHORA % |

The Waves |

Virginia Woolf |

16.0 |

Survivor |

Chuck Palahniuk |

13.5 |

The Ocean at the End of the Lane |

Neil Gaiman |

13.3 |

Breakfast of Champions |

Kurt Vonnegut |

13.2 |

Slaughterhouse-Five |

Kurt Vonnegut |

12.3 |

The Fountainhead |

Ayn Rand |

12.3 |

Cat and Mouse |

James Patterson |

11.9 |

Slapstick |

Kurt Vonnegut |

11.5 |

Lullaby |

Chuck Palahniuk |

11.4 |

Kiss the Girls |

James Patterson |

11.3 |

“So it goes” aside, Vonnegut speaks in repetition often, and to great effect. Here’s a passage from Cat’s Cradle:

Before we took the measure of each other’s passions, however, we talked about Frank Hoenikker, and we talked about the old man, and we talked a little about Asa Breed, and we talked about the General Forge and Foundry Company, and we talked about the Pope and birth control, about Hitler and the Jews. We talked about phonies. We talked about truth. We talked about gangsters; we talked about business. We talked about the nice poor people who went to the electric chair; and we talked about the rich bastards who didn’t. We talked about religious people who had perversions. We talked about a lot of things.

The percentage of sentences in which the first two words are the same as the previous sentence—what you might call two-word anaphora—reveals a similar pattern to the chart above. It’s not just that Vonnegut, Woolf, or Rand was being lazy and starting each sentence off with a boring the. Two-word anaphora tends not to end up in the final text unless it is intentional. The same authors top the following list, with the arrival of the master himself, Dickens.

BOOK |

AUTHOR |

TWO-WORD ANAPHORA % |

The Waves |

Virginia Woolf |

5.5 |

Survivor |

Chuck Palahniuk |

4.0 |

The Chimes |

Charles Dickens |

3.6 |

Fight Club |

Chuck Palahniuk |

3.3 |

Shalimar the Clown |

Salman Rushdie |

3.2 |

The Torrents of Spring |

Ernest Hemingway |

3.2 |

Slapstick |

Kurt Vonnegut |

3.2 |

The Sirens of Titan |

Kurt Vonnegut |

3.1 |

Atlas Shrugged |

Ayn Rand |

3.0 |

The Battle of Life |

Charles Dickens |

3.0 |

On the other end of the spectrum we can look at the type of book that chooses not to use anaphora very often. Bleeding Edge by Thomas Pynchon has over 10,000 sentences and just 1.6 % of those (163) begin with the same word as the previous sentence. Pynchon’s work makes up five of the top ten slots here.

Books with the Least One-Word Anaphora |

||

BOOK |

AUTHOR |

ANAPHORA % |

Bleeding Edge |

Thomas Pynchon |

1.6 |

Vineland |

Thomas Pynchon |

1.9 |

Inherent Vice |

Thomas Pynchon |

2.2 |

Against the Day |

Thomas Pynchon |

2.3 |

The Children |

Edith Wharton |

2.4 |

A Son at the Front |

Edith Wharton |

2.5 |

Other Voices, Other Rooms |

Truman Capote |

2.6 |

Mason & Dixon |

Thomas Pynchon |

2.6 |

Twilight Sleep |

Edith Wharton |

2.7 |

The Grass Harp |

Truman Capote |

2.8 |

Slaughterhouse-Five has 87 instances wherein three straight sentences start with the same word. If Pynchon were to write in the same exact manner, then Bleeding Edge would be expected (based on its length) to have 230-plus such cases of three consecutive sentences starting with the same word. Instead, there are just eight.

Pynchon favors variety; Vonnegut favors familiarity. I looked at the most common three-word strings to start off sentences in every book. In Slaughterhouse-Five the ten most common cases are:

1. So it goes

2. There was a

3. It was a

4. And so on

5. He was a

6. He had been

7. He had a

8. They had been

9. One of the

10. Now they were

These represent almost 7 % of all sentences in the book.

In Inherent Vice the ten most common openers are:

1. By the time

2. After a while

3. There was a

4. I don’t know

5. It was a

6. Not to mention

7. What do you

8. I don’t think

9. Doc must have

10. Now and then

These represent less than 1.5 % of all sentences in the book.

So Pynchon’s variety is seen not just in his lack of anaphora, but in the variety of his sentences as well. In the sample of all fifty authors seen in the previous chapter, Pynchon ranks near the bottom when we look at the percent of sentences that use his top ten openers.I Only James Joyce beats him for more variety. Vonnegut ranks toward the top, behind only a few authors—Hemingway, Gaiman, Rand, Rowling, and Stephenie Meyer—who rely on their top ten openers more often.

For curiosity’s sake here are the top ten most popular three-word sentence openers for a handful of other notable books. Like Pynchon and his openers, I was looking for variety so I handpicked the examples to be as different as possible. Limited as they may be, each offers a tiny glimpse into the depths of each work.

FIGHT CLUB |

FIFTY SHADES OF GREY |

THE ADVENTURES OF TOM SAWYER |

CHUCK PALAHNIUK |

E L JAMES |

MARK TWAIN |

1. You wake up |

1. Christian Grey CEO |

1. By and by |

2. This is the |

2. I want to |

2. There was a |

3. I am Joe’s |

3. My inner goddess |

3. I don’t know |

4. This is a |

4. His voice is |

4. It was a |

5. I go to |

5. From Christian Grey |

5. What is it |

6. You have to |

6. I have to |

6. There was no |

7. This is how |

7. I shake my |

7. The old lady |

8. The space monkey |

8. I don’t want |

8. Then he said |

9. The first rule |

9. I need to |

9. What did you |

10. Tyler and I |

10. I don’t know |

10. At last he |

PRIDE AND PREJUDICE |

THE GREAT GATSBY |

THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA |

JANE AUSTEN |

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD |

ERNEST HEMINGWAY |

1. I do not |

1. It was a |

1. The old man |

2. I can not |

2. I want to |

2. He did not |

3. I am sure |

3. There was a |

3. I wish I |

4. I am not |

4. She looked at |

4. I do not |

5. It is a |

5. I’m going to |

5. But there was |

6. Mrs. Bennet was |

6. I’d like to |

6. But I will |

7. It was a |

7. He looked at |

7. But I have |

8. I have not |

8. She turned to |

8. There was no |

9. She is a |

9. It was the |

9. I wonder what |

10. It was not |

10. I don’t think |

10. The sun was |

THE DA VINCI CODE |

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD |

|

GEORGE ORWELL |

DAN BROWN |

HARPER LEE |

1. The animals were |

1. The Holy Grail |

1. Jem and I |

2. It was a |

2. I don’t know |

2. There was a |

3. All the animals |

3. It was a |

3. I don’t know |

4. I do not |

4. Find Robert Langdon |

4. It was a |

5. The animals had |

5. Langdon felt a |

5. There was no |

6. None of the |

6. There was a |

6. Aunt Alexandra was |

7. Do you not |

7. O Draconian Devil |

7. It was not |

8. No animal shall |

8. Oh lame saint |

8. Judge Taylor was |

9. Whatever goes upon |

9. Langdon and Sophie |

9. That’s what I |

10. As for the |

10. The altar boy |

10. I don’t want |

Martin Amis hates clichés. When the English novelist published a book of his literary criticism, he decided to call it The War Against Cliché. Amis explains his title by asserting that “all writing is a campaign against cliché. Not just clichés of the pen but clichés of the mind and clichés of the heart.”

Amis is not alone. Clichés, by definition, are overused. No writer considers themselves an abuser of tired language. But what is considered a cliché is open to interpretation. Imagine if we had Amis read thousands of books at once to assign each an Amis Cliché Score. Modern technology is not advanced enough to create Martin Amises to do our work for us, but even if it were it would have limited value. It’s very likely that Martin Amis, an academic from a literary family, would have different standards from anyone else.

And it’s also hard to imagine weighing one cliché against another. A story that ends with the good guy saving the day and getting the girl has a clichéd ending. How do you weigh that clichéd ending with another book that has a more original ending but is full of stock characters? Which book is more “clichéd”? That’s not a question an objective method could answer.

But if we focus on overused phrases, what Amis would consider “clichés of the pen,” it might be possible to answer the narrow question of who writes with the most clichés. Which author uses sayings such as “fish out of water, “dressed to kill,” or “burn the midnight oil” the most?

The above are all expressions found in The Dictionary of Clichés. The book by Christine Ammer published in 2013 contains over 4,000 clichés and, to my knowledge, is the largest collection of English language clichés. Because of its size, and the fact that Ammer had been compiling collections of clichés and colloquialisms for 25 years before The Dictionary of Clichés was published, I’ve chosen her as the official arbiter of what does or what does not count as a cliché.

Every author uses clichés, even if each has a unique voice. For the chart on the next page, I picked an assortment of authors and one cliché (from The Dictionary of Clichés) that each uses at an unusually high rate.

It’s worth noting that Ammer’s cliché criterion, even with 4,000 entries, is not comprehensive and may be different than Amis’s list of expressions, or mine or yours. When detailing his view on clichés in an interview with Charlie Rose, Amis mentioned as examples “The heat was stifling” and “She rummaged in her handbag.” Neither of these two specific phrases makes its way into the Dictionary of Clichés.

But beyond that, defining a cliché is time dependent. Some clichéd phrases such as “never darken my door again” predate even older authors like Jane Austen. Others are younger. “Yada yada” was repopularized by a 1997 Seinfeld episode and “soccer mom” has a clear modern connotation. “Catch-22,” which Ammer includes, is based on the 1961 Joseph Heller novel. It wasn’t cliché when Heller invented it. Language changes over time, and if Christine Ammer published this list 200 years earlier, in 1813 (the same year Pride and Prejudice was published), the results would look different.

AUTHOR |

WORKS |

CLICHÉ |

Isaac Asimov |

7 Foundation Series books |

past history |

Jane Austen |

6 novels |

with all my heart |

Enid Blyton |

21 Famous Five books |

in a trice |

Ray Bradbury |

11 novels |

at long last |

Ann Brashares |

9 novels |

blah blah blah |

Dan Brown |

4 Robert Langdon books |

full circle |

Tom Clancy |

13 novels |

by a whisker |

Suzanne Collins |

3 Hunger Games books |

put two and two together |

Clive Cussler |

23 Dirk Pitt novels |

wishful thinking |

James Dashner |

3 Maze Runner novels |

now or never |

Theodore Dreiser |

8 novels |

thick and fast |

William Faulkner |

19 novels |

sooner or later |

Dashiell Hammett |

5 novels |

talk turkey |

Khaled Hosseini |

3 novels |

nook and cranny |

E L James |

3 Fifty Shades books |

words fail me |

James Joyce |

3 novels |

from the sublime to the ridiculous |

George R. R. Martin |

8 novels |

black as pitch |

Herman Melville |

9 novels |

through and through |

Stephenie Meyer |

4 Twilight books |

sigh of relief |

Vladimir Nabokov |

8 novels |

in a word |

James Patterson |

22 Alex Cross novels |

believe it or not |

Jodi Picoult |

21 novels |

sixth sense |

Rick Riordan |

5 Percy Jackson novels |

from head to toe |

J. K. Rowling |

7 Harry Potter books |

dead of night |

Salman Rushdie |

9 novels |

the last straw |

Alice Sebold |

3 novels |

think twice |

Zadie Smith |

4 novels |

evil eye |

Donna Tartt |

3 novels |

too good to be true |

J. R. R. Tolkien |

LOTR and The Hobbit |

nick of time |

Tom Wolfe |

4 novels |

sinking feeling |

Note: These clichés are all from The Dictionary of Clichés. The selection in this table was chosen by me for variety and oddity, not by any specific quantitative measure.

The last question to consider, before crowning our champion of clichés, is whether to include clichés that appear in dialogue. If characters are using clichéd phrases, is it clichéd writing? Or just capturing how people talk? Take, for instance, this sample of dialogue from James Patterson’s Mary, Mary, with phrases Ammer lists in her Dictionary of Clichés in bold. The main character, Alex Cross, is the first one to speak below.

“. . . But if it gets you Mary Smith, then everything’s okay and you’re a hero.”

“Russian roulette,” she said dryly.

“Name of the game,” I said.

“By the way, I don’t want to be a hero.”

“Goes with the territory.”

She finally smiled. “America’s Sherlock Holmes. Didn’t I read that somewhere about you?”

“Don’t believe everything you read.”

The short dialogue above has three clichés from Ammer’s set list of 4,000, as well as two other phrases (“I don’t want to be a hero” and “don’t believe everything you read”) that would be strong contenders if Ammer ever expands to 4,002. And while one could argue against including dialogue, I’ve ultimately decided to leave it in. If so much of your main character’s language is tied up in cliché, then at a certain point, so is your main character—and so may be your novel.

Now, with all these caveats out in the open, what do we find? Who is the most clichéd writer?

I’ve counted the total number of times any cliché appeared in an author’s writing, looking at all fifty authors I’ve been using as examples throughout this book.