“That was the first sentence. The problem was that I just couldn’t think of the next one.”

—CHARLIE IN THE PERKS OF BEING A WALLFLOWER, BY STEPHEN CHBOSKY

What makes a great opening sentence?

In response to a question on Twitter about her favorite first sentence in literature, novelist Margaret Atwood answered: “ ‘Call me Ishmael.’ Three words. Power-packed. Why Ishmael? It’s not his real name. Who’s he speaking to? Eh?”

Many consider the opening to Moby Dick to be the best first sentence of all time. It’s one of a handful of openers that people are expected to know and recognize. Almost any list of either the best or most iconic novel first sentences ever written will include Call me Ishmael.

Atwood’s justification—“Three words. Power-packed”—tapped into a common sensibility. Stephen King, in a 2013 interview with The Atlantic, cited his favorite three openers, and they averaged a mere six words long. Brevity can make for a phenomenal opening.

But what do the numbers say? In each book, a writer only gets one first sentence. What do you do with that opportunity? Do you go long or do you keep it short? Is one better, statistically, than the other?

As a first step, I looked at what each writer in my sample has chosen to do throughout his or her career. The results, to no surprise, vary enormously.

The median opener in Atwood’s 15 novels is a compact nine words. Her first lines to The Handmaid’s Tale (“We slept in what had once been the gymnasium”) and MaddAddam (“In the beginning, you lived inside the Egg”) are typical of her style. And openers like “Snowman wakes before dawn” and “I don’t know how I should live” lower her tally even further.

Nine words, as a median length, is on the extreme low end of the scale when it comes to first sentences. Atwood’s median is just one-third that of a writer like Salman Rushdie, whose median opener measures 29 words. Here’s his 29-word opening to Shame.

In the remote border town of Q, which when seen from the air resembles nothing so much as an ill-proportioned dumb-bell, there once lived three lovely, and loving, sisters.

That’s a lot more clauses than any of Atwood’s. Much like Rushdie, Michael Chabon goes long, holding a median length of 28 words. Out of the seven novels he has written, three have had openers of lengths of 41, 52, and 62 words. Only one of the seven has an opening sentence shorter than the average sentence length in the rest of the book.

Chabon and Rushdie are closer to typical than Atwood. Compared to the 31 other writers in my sample with at least five books to their name, Atwood comes in as the writer with the second-shortest first sentences, just behind Toni Morrison.

MEDIAN LENGTH |

|

Toni Morrison |

5 |

Margaret Atwood |

9 |

Mark Twain |

11 |

Dave Eggers |

11 |

Chuck Palahniuk |

11.5 |

AUTHORS WITH LONGEST FIRST SENTENCES |

MEDIAN LENGTH |

Jane Austen |

32 |

Vladimir Nabokov |

29 |

Salman Rushdie |

29 |

Michael Chabon |

28 |

Edith Wharton |

28 |

Only authors with five books were included. The variation is high when each book only has one data point.

Some authors have no set pattern in their first sentences: The first sentence in Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (the one that starts off “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”) measures in at 119 words, 17 commas, and an em-dash. The first sentence to his A Christmas Carol is six words: “Marley was dead: to begin with.” Both sentences are classics.

But the data reveals definite choices in other authors’ careers. Including her 2015 novel, God Help the Child, Toni Morrison has written 11 books. Here are her opening sentences—she likes to keep it brief.

Toni Morrison’s First Sentences |

|

The Bluest Eye (1970) |

Here is the house. |

Sula (1973) |

In that place, where they tore the nightshade and blackberry patches from their roots to make room for the Medallion City Golf Course, there was once a neighborhood. |

Song of Solomon (1977) |

The North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance agent promised to fly from Mercy to the other side of Lake Superior at three o’clock. |

Tar Baby (1981) |

He believed he was safe. |

Beloved (1987) |

124 was spiteful. |

Jazz (1992) |

Sth, I know that woman. |

Paradise (1997) |

They shoot the white girl first. |

Love (2003) |

The women’s legs are spread wide open, so I hum. |

A Mercy (2008) |

Don’t be afraid. |

Home (2012) |

They rose up like men. |

God Help the Child (2015) |

It’s not my fault. |

While individual authors vary widely in their choices about first sentences, a larger trend emerges when we look at the 31 authors as a whole. Of all the books they’ve written, 69 % of these books begin with first sentences that are longer than the average sentence throughout the rest of the book. That is, the standard choice for authors is to write long rather than short for their openers.

Does this disprove the theory that short is better, boiling it down to just a matter of personal choice? Or does this mean that most authors should cut down on their winding introductions?

To find out, I decided to go one step further and look at what are considered the “best” opening lines in literature. I’ve gone through eight different publications that ranked the “best” or “most memorable” first sentences. Twenty openers were on four of these lists, a consensus. Below are those twenty openers.

The 20 Best First Sentences in Literature |

|

BOOK/AUTHOR |

FIRST SENTENCE |

Pride and Prejudice / Jane Austen |

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife. |

Moby Dick / Herman Melville |

Call me Ishmael. |

Lolita / Vladimir Nabokov |

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. |

The Bell Jar / Sylvia Plath |

It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York. |

Anna Karenina / Leo Tolstoy |

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. |

1984 / George Orwell |

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. |

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn / Mark Twain |

You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter. |

Murphy / Samuel Beckett |

The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new. |

Ulysses / James Joyce |

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed. |

The Stranger / Albert Camus |

Mother died today. |

All this happened, more or less. |

|

A Tale of Two Cities / Charles Dickens |

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only. |

Gravity’s Rainbow / Thomas Pynchon |

A screaming comes across the sky. |

One Hundred Years of Solitude / Gabriel García Márquez |

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice. |

The Trial / Franz Kafka |

Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything truly wrong, he was arrested. |

The Catcher in the Rye / J. D. Salinger |

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. |

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man / James Joyce |

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo. |

Their Eyes Were Watching God / Zora Neale Hurston |

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. |

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader / C. S. Lewis |

There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it. |

The Old Man and the Sea / Ernest Hemingway |

He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish. |

Note: Not all the novels above were originally published in English. A translated version was used to compile the length comparison statistics.

Again, the variation is very high, with several ultra-short sentences and several winding ones, such as The Catcher in the Rye’s 63-word opener. The median length of these openings is 16 words. Although it’s a painfully small sample, we do find that of the top 20 openers 12 (60 %) were shorter than the average sentence in their respective books. In the broader sample used above, just 31 % had an opener shorter than the book’s average sentence.

It seems that Atwood and King were on to something when praising the power of a concise, direct opening: Shorter openings do tend to be more memorable.

But it’s also important to note that the data in this section is saying far more than just short is good. The first sentence is only as popular as the rest of the book, and brevity alone will not make a first sentence great. In addition to “Call me Ishmael” Herman Melville also started novels off with the quick “Six months at sea!” and “We are off!” But nobody goes around praising the openings of Typee or Mardi.

Looking at the top twenty sentences, we can see that what each of the best openers have in common is not length but a certain originality or novelty that makes them memorable. This can be accomplished briefly or at length—but if anything it’s the shock of the unpredicted and the unpredictable that makes them stick.

While looking at the stats can help us shed light on the question of what makes a good opener, it can’t solve the question for us—because the great openers succeed by intentionally breaking patterns. Perhaps Stephen King put it best: In his Atlantic interview he said, “There are all sorts of theories and ideas about what constitutes a good opening line. . . . To get scientific about it is a little like trying to catch moonbeams in a jar.”

We may not be able to reverse-engineer the perfect opener, but what do we find if we look at the other end of the spectrum—at bad first sentences? There are certain tropes, for instance, that have fallen into cliché, and that many an author would be wise to avoid.

At the very top of the list is: It was a dark and stormy night . . .

It’s one of the most famous openings in literature, and it was original when it was first penned, almost 200 years ago by Edward Bulwer-Lytton in his 1830 novel Paul Clifford. Here’s its complete form:

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents, except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the house-tops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

But the sentence has since become an object of ridicule. Ray Bradbury mocked it in the opening to his novel Let’s All Kill Constance:

It was a dark and stormy night.

Is that one way to catch your reader?

Well, then, it was a stormy night with dark rain pouring in drenches on Venice. . . .

Likewise, for the last thirty years, the San Jose State University English department has been hosting a Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest, in which competitors try to create the worst opening sentence “to the worst of all possible novels.”

Here’s a recent winner:

Folks say that if you listen real close at the height of the full moon, when the wind is blowin’ off Nantucket Sound from nor’ east and the dogs are howlin’ for no earthly reason, you can hear the awful screams of the crew of the “Ellie May,” a sturdy whaler captained by John McTavish; for it was on just such a night when the rum was flowin’ and, Davey Jones be damned, big John brought his men on deck for the first of several screaming contests.

Bulwer-Lytton got the short end of the stick by having the contest named after him. And while it might be unfair to call out an author from 1830 for falling into a cliché before it existed in full, it has become an old trope to open a book with a description of the weather. Elmore Leonard’s first rule on writing, in fact—his number one rule—was “Never open a book with weather.”

I wanted to find out who, among the authors we’ve looked at in this book, relied on the weather most often to set the scene. In other words, who is our Bulwer-Lytton award winner?

When I ran the numbers, a runaway champion leapt out from the pack. It turns out that when it comes to breezy weather openings, our leader also happens to be the author who has sold more books than any other living writer: Danielle Steel. (If you haven’t read her, check out the line-up of romance novels at your local grocery store. She’ll be there.)I

Here, in the first sentence of her first novel, she started to dabble with the weather opening:

It was a gloriously sunny day and the call from Carson Advertising came at nine-fifteen.

And it worked. So why not go back to the well? By 2014, Danielle Steel had written 92 novels, and a shocking 42 of these mention weather in the opening sentence. Read through them on the following pages at your own discretion.

It was a gloriously sunny day and the call from Carson Advertising came at nine-fifteen. | The weather was magnificent. | The early morning sun streamed across their backs as they unhooked their bicycles in front of Eliot House on the Harvard campus. | Hurrying up the steps of the brownstone on East Sixty-third Street, Samantha squinted her eyes against the fierce wind and driving rain, which was turning rapidly into sleet. | When it snows on Christmas Eve in New York, there is a kind of raucous silence, like bright colors mixed with snow. | The house at 2129 Wyoming Avenue, NW, stood in all its substantial splendor, its gray stone facade handsomely carved and richly ornate, embellished with a large gold crest and adorned with the French flag, billowing softly in a breeze that had come up just that afternoon. | The sun sank slowly onto the hills framing the lush green splendor of the Napa Valley. | The heat of the jungle was so oppressive that just standing in one place was almost like swimming through thick, dense air. | The sun reverberated off the buildings with the brilliance of a handful of diamonds cast against an iceberg, the shimmering white was blinding, as Sabina lay naked on a deck chair in the heat of the Los Angeles sun. | Everything in the house shone as the sun streamed in through the long French windows. | The rains were torrential northeast of Naples on the twenty-fourth of December 1943, and Sam Walker huddled in his foxhole with his rain gear pulled tightly around him. | Zoya closed her eyes again as the troika flew across the icy ground, the soft mist of snow leaving tiny damp kisses on her cheeks, and turning her eyelashes to lace as she listened to the horses’ bells dancing in her ears like music. | The birds were already calling to each other in the early morning stillness of the Alexander Valley as the sun rose slowly over the hills, stretching golden fingers into a sky that within moments was almost purple. | The snowflakes fell in big white clusters, clinging together like a drawing in a fairy tale, just like in the books Sarah used to read to the children. | It was a chill gray day in Savannah, and there was a brisk breeze blowing in from the ocean. | The air was so still in the brilliant summer sun that you could hear the birds, and every sound for miles, as Sarah sat peacefully looking out her window. | The sky was a brilliant blue, and the day was hot and still as Diana Goode stepped out of the limousine with her father. | Charles Delauney limped only slightly as he walked slowly up the steps of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, as a bitter wind reached its icy fingers deep into his collar. | It was one of those perfect, deliciously warm Saturday afternoons in April, when the air on your cheek feels like silk, and you want to stay outdoors forever. | The weather in Paris was unusually warm as Peter Haskell’s plane landed at Charles de Gaulle Airport. | The sounds of the organ music drifted up to the Wedgwood blue sky. | In the driving rain of a November day, the cab from London to Heathrow took forever. | The box arrived on a snowy afternoon two weeks before Christmas. | It was a brilliantly sunny day in New York, and the temperature had soared over the hundred mark long before noon. | The call came when she least expected it, on a snowy December afternoon, almost exactly thirty-four years after they met. | Marie-Ange Hawkins lay in the tall grass, beneath a huge, old tree, listening to the birds, and watching the puffy white clouds travel across the sky on a sunny August morning. | The sun glinted on the elegant mansard roof of The Cottage, as Abe Braunstein drove around the last bend in the seemingly endless driveway. | It was a perfect balmy May evening, just days after spring had hit the East Coast with irresistible appeal. | The sun was shining brightly on a hot June day in San Dimas, a somewhat distant suburb of L.A. | It was one of those chilly, foggy days that masquerade as summer in northern California, as the wind whipped across the long crescent of beach, and whiskbroomed a cloud of fine sand into the air. | It was a lazy summer afternoon as Beata Wittgenstein strolled along the shores of Lake Geneva with her parents. | The sailing yacht Victory made her way elegantly along the coast toward the old port in Antibes on a rainy November day. | The sun was brilliant and hot, shining down on the deck of the motor yacht Blue Moon. | Olympia Crawford Rubinstein was whizzing around her kitchen on a sunny May morning, in the brownstone she shared with her family on Jane Street in New York, near the old meat-packing district of the West Village. | It was a beautiful hot July day in Marin County, just across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, as Tanya Harris bustled around her kitchen, organizing her life. | It was a quiet, sunny November morning, as Carole Barber looked up from her computer and stared out into the garden of her Bel-Air home. | It was an absolutely perfect June day as the sun came up over the city, and Coco Barrington watched it from her Bolinas deck. | Hope Dunne made her way through the silently falling snow on Prince Street in SoHo in New York. | Seth Adams left Annie Ferguson’s West Village apartment on a sunny September Sunday afternoon. | There was a heavy snowfall that had started the night before as Brigitte Nicholson sat at her desk in the admissions office of Boston University, meticulously going over applications. | The two men who lay parched in the blistering sun of the desert were so still they barely seemed alive. | Lily Thomas lay in bed when the alarm went off on a snowy January morning in Squaw Valley.

Compared to all other authors I searched through, including all 26 authors in my sample who have penned at least ten books, no one comes close to Steel’s weather rate. Even compared to her closest peers who rival her popularity and prolific nature, Steel is far and away the leader of using weather to open her books.

Steel uses the weather trope almost twice as often as her closest competitor. By my count, half the time the weather is dreary, rainy, or stormy in some way. The other half, the weather is of the more pleasant or perfect variety (“perfect deliciously warm Saturday afternoons,” “perfect balmy May evening,” “absolutely perfect June day”). It’s still working for her, even if it verges on some Bulwer-Lytton Award–winning candidates (my favorite is simply: “The weather was magnificent”).

As much grief as the old weather opening gets, it remains a standby for many authors. Sometimes you just have to set the scene, after all. Consider the opening to 1984, considered one of the greatest first sentences of all time: “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” Weather isn’t necessarily a death-knell, especially when (as Orwell does) it’s used to play with the reader’s expectations. Even in the most well-regarded writing, weather is still a common opening motif: In the 86 Pulitzer Prize winners for fiction, 13 openings rely on the weather.

Franklin Dixon got his start in the book-publishing world in 1927 as the author of The Tower Treasure, the first book in the Hardy Boys series. Dixon found immediate success with The Tower Treasure and its sequels. The first five books in the Hardy Boys series all ranked in the top 200 on Publishers Weekly 2001 list of “All-Time Bestselling Children’s Books.” Dixon went on to write more than 300 more Hardy Boys books, up until Movie Mission in 2011.

But if Franklin Dixon was old enough to write the first Hardy Boys novel in 1927, how was he still writing books 84 years later?

The truth is there was no person named Franklin Dixon. The name was a creation of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a book-packaging company created by Edward Stratemeyer. In its first fifty years of operation following its creation in 1899, the company cranked out 98 different series. Everything about these books was thought out in detail, including the use of pseudonyms like Franklin Dixon. By writing under a single fake name, the ghostwriters had little control over the series or their payments. If a writer wished to discontinue writing, the series could continue without anyone (mostly the children readers) having any idea that there had been a change.

We’ve already seen that the series was able to hold together for so long in part because of strict rules about length and structure. But these were far from the only rules. Ghostwriters were given plot outlines by the syndicate (often penned by Edward Stratemeyer) and told to keep their writing within certain guidelines. One of the most important rules was that each chapter had to end mid-action—with a cliffhanger.

Consider the first seven Hardy Boys books. If you pick up any of these books today you’ll notice they all have exactly 20 chapters.II They are all between 32,000 and 36,000 words. And they all like to end their chapters mid-action. Below is a chart showing the last sentence in each chapter of the first Hardy Boys book, The Tower Treasure.

CHAPTER |

LAST SENTENCE |

1 |

In a few moments the boys were tearing down the road in pursuit of the automobile! |

2 |

The same thought was running through Frank’s and Joe’s minds: maybe this mystery would turn out to be their first case! |

3 |

“Follow me!” |

4 |

The detective stood by sullenly as Frank pulled out a penknife and began to scrape the red paint off part of the fender. |

5 |

“Come on, everybody!” |

6 |

“My dad is innocent!” |

7 |

“Slim, we’ll do all we can to help your father.” |

8 |

“And this time a swell one!” |

9 |

And were they about to share another of his secrets? |

10 |

“But where is he now?” |

11 |

“Mother’s pretty worried that something has happened to Dad.” |

12 |

With that he arose, stumped out of the room, and left the house. |

13 |

“Where’s some water?” |

14 |

The brothers raced from the house, confident that they were about to solve the Tower Treasure mystery. |

15 |

Frank and Joe, tingling with excitement, followed. |

16 |

“I’ve found a buried chest!” |

17 |

It came from the top room of the old tower! |

18 |

“This must be the place!” |

19 |

Without warning the trap door was slammed shut and locked from the outside! |

20 |

“An excellent idea!” |

Skimming the list, it’s easy to see some patterns, especially when it comes to punctuation. Fourteen of twenty chapters end with either an exclamation point or a question mark. The cliffhanger rule is maintained in a very obvious way: either through obvious excitement (!) or obvious mystery (?).

The Hardy Boys are not exactly a model of subtle writing. Earlier in this book we looked at Elmore Leonard’s advice about exclamation points: “no more than two or three per 100,000 words.” The Hardy Boys use more than 900 exclamation points per 100,000 words.

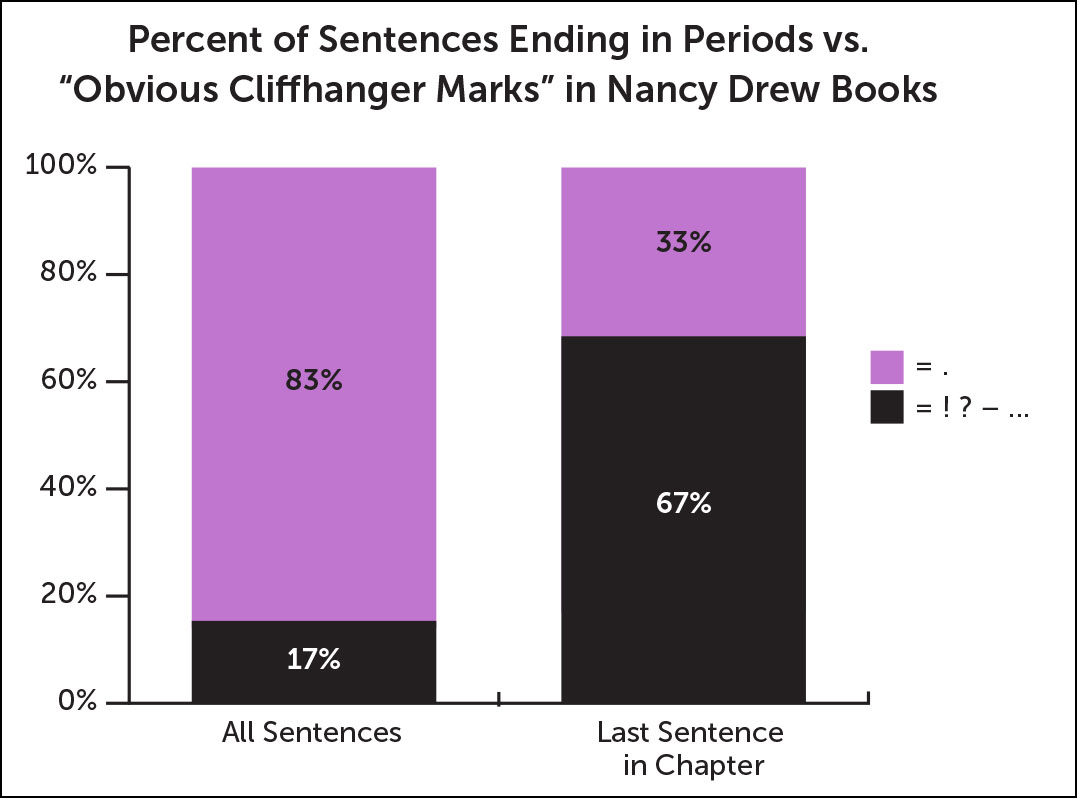

But even if you compare a standard sentence in the Hardy Boys to one of the chapter closers, it’s clear that the chapters are built to go out with a bang. To simplify things let’s call any of the following an “Obvious Cliffhanger Mark”: an exclamation point, a question mark, an em-dash (as in a quote cutoff mid-sentence), or an ellipsis. In the Hardy Boys about 19 % of all sentences end with one of these “Obvious Cliffhanger Marks.” But, among sentences that close out a chapter, 71 % end with the “Obvious Cliffhanger Mark.”

The Nancy Drew books, also produced by the Stratemeyer Syndicate, follow the same level of consistency. Looking at the first seven books as a sample, they are all twenty chapters long and all have between 32,000 and 37,000 words, and they use cliffhangers in the same way.

Below is the same plot for the Nancy Drew books. Chapter endings are almost four times as likely to end with an “Obvious Cliffhanger Mark” compared with the average sentence.

Books run by the Stratemeyer Syndicate weren’t the only ones who used this tactic to make children keep reading. Enid Blyton is a prolific British children’s author who wrote 186 novels, starting in 1922, that would end up selling half a billion copies. The Famous Five, a Blyton series about five kids who go on adventures when back from boarding school, had chapters that ended with the “Obvious Cliffhanger Mark” 83 % of the time. A normal sentence in her book only ended in such excitement 25 %.

In today’s popular children’s and young adult literature the trend is all but absent. Harry Potter ends with such obvious cliffhangers about 14 % of the time. The Goosebumps series clocks in at 18 %, the Hunger Games series at 4 %, and all 142 chapters of the Divergent trilogy end in a period.

It’s impossible to come up with an objective measure of cliffhanger-ness, though. The Hunger Games may not use loud punctuation at the end of the chapters, but that doesn’t mean there are not cliffhangers. Ending chapter after chapter with a question mark or exclamation point may be too heavy-handed for modern sensibilities. But there is another style choice that almost all popular page-turner writers use to signal a cliffhanger ending.

There are 82 chapters in Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games trilogy. Throughout the books, about 9 % of all paragraphs (not including dialogue) are one sentence long. However, when considering the final paragraph of each chapter, we find that 62 % are just one sentence long.

For example, here are some of the last paragraphs a reader sees before deciding whether or not to flip to the next chapter.

Then the ants bore into my eyes and I black out.

In other words, I step out of line and we’re all dead.

This is one of his death traps.

And his blood as it splatters the tiles.

Right before the explosions begin, I find a star.

It’s hard to get the full effect of such a short chapter ender from the single sentences above. The average paragraph in the Hunger Games is ninety words. It fills more than one-third of a typical page. But for the ends of her chapters, Collins chooses to avoid anything that might look like a wall of text. She gives the reader a short, attention-grabbing plot point to keep them interested.

Collins’s practice of ending chapters on a short, punchy paragraphs turns out to be near universal among thriller writers. Patterson’s 22 Alex Cross books all have shorter chapter-ending paragraphs than the paragraphs throughout. Stephen King is twice as likely to use a single-sentence paragraph when it’s the last paragraph of a chapter.

Note: Some books have clearly titled chapters. Others have page breaks with no markings and some have no page breaks at all. For some books, judgment calls were required to decide what constituted a chapter.

Of the last 40 New York Times number one bestsellers that were thrillers, mystery, or suspense, 36 books had chapter-ending paragraphs that were shorter than the paragraphs within the rest of the chapter. The typical thriller has 60 % more one-sentence paragraphs at the end of the chapter than in the middle.

Not everyone is a fan of these abrupt paragraphs. In a review of Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park Martin Amis criticized the novel for having “one-page chapters, one-sentence paragraphs and one-word sentences.” Even if Amis was not talking about the last chunk of text in a chapter, it’s clear he considers Crichton’s use of short paragraphs a cliché of the thriller genre.

But in The Information, Amis’s novel that came out the same year as his Jurassic Park review, he ends 30 % of his chapters with one-sentence paragraphs. That’s almost twice as often as he uses a one-sentence prose paragraph in the rest of the book. Even some literary writers like Amis find a certain usefulness in ending abruptly to get the reader to keep reading.

The page-turner practice has not in general crept its way from thrillers to literary fiction. In 2013 and 2014, 41 different novels were given at least one of the following honors: New York Times Top Ten Books of the Year, Pulitzer Prize finalists, Man Booker Prize short list, National Book Award finalists, National Book Critics Circle finalists, and Time magazine’s best books of the year. Thirty-eight of these books had chapters. Of these books, just twenty had more one-sentence paragraphs at the end of chapters than in the middle of the chapter. That’s close to half, about what could be considered random.

While there’s no sign that literary writers en masse will be using the device anytime soon, among popular thriller writers the one-sentence ender seems to be the natural evolution of the Hardy Boys’ or Enid Blyton’s Famous Five’s distinctive cliffhanger marks. There’s one very good reason why page-turners keep seeking out punchy endings, and it’s the same reason that the Hunger Games and Alex Cross series each have sold millions of copies. What is it?