Bram Stoker as a child, circa 1854. Photographer unknown.

Bram Stoker as a child, circa 1854. Photographer unknown.

THE CHILD THAT WENT WITH THE FAIRIES

— Dracula

“In my babyhood,” Bram Stoker wrote of his early years in Victorian Dublin, “I never knew what it was to stand upright.” Mysteriously bedridden “until nearly the age of seven,” he would eventually grow into a robust giant of a man, a prizewinning athlete bigger and taller than his father or brothers, looming over his entire family from a height of six foot two, at a time when the average height of men in Britain at the age of twenty-one was only five foot five. Stoker directly attributed the uncanny growth spurt to “long illnesses, as a child,” according to his son, writing on the one hundredth anniversary of his birth in 1947. But this only adds another mystery, since medical statisticians correlate adult height as much with early childhood health as with genetics.

Stoker’s story, therefore, defies medical science, just as it defies common sense. Nonetheless, both he and his family insisted it was true. However, as Stoker’s late-life friend Sir Arthur Conan Doyle opined on more than one occasion through the fictional mouthpiece of Sherlock Holmes, “When you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

Or, at least, there might begin an understanding.

The history of ancient Ireland is inextricably bound to its folklore. The earliest Irish settlers arrived sometime around 7000 BC, by sea or, as many historians speculate, via a land bridge to Scotland lost to rising waters at the end of the Ice Age. Neolithic Irish tombs predating the Pyramids of Giza by five hundred years and Stonehenge by a thousand offer enduring testimony of a primitive society that left no written accounts of its beliefs, only a rich archaeological repository recording an agrarian culture as keenly attuned to the presence of death and the supernatural as it was to the circles of the seasons and the transit of the stars. Funeral rites had a central prominence. Located northwest of Dublin near Kells is Newgrange, Ireland’s oldest structure and most monumental tomb. A mound of earth and stone three hundred feet wide, Newgrange was ingeniously designed by ancient astronomers to have its interior illuminated by the rising sun every winter solstice, marking the beginning of a new cycle of life and its harvest. Newgrange’s intricate Stone Age carvings of circles, spirals, and undulating waveforms are today universally recognized as “Celtic” design motifs, even though the Celts did not arrive on Irish shores until much later, during the Iron Age. Ireland had never been invaded by the Roman Empire, whose people called the island Hibernia—the land of winter—and considered it wild, barbaric, and impervious to civilizing. The farthest western outpost of Europe was, for all practical purposes, the end of the world.

When the Roman Empire crumbled, the Celts moved into Britannia and Hibernia from central Europe, bringing with them a hierarchal society with no small amount of its own barbarity. Classical writers, including Julius Caesar, described harvest rituals of human sacrifice performed by Celts and supervised by their priestly class, the Druids. The whole Celtic world, according to Caesar, was “to a great degree devoted to superstitious rites.” He took particular note of the Celtic belief “that souls are not annihilated, but pass after death from one body to another, and they hold that by this teaching men are much encouraged to valor, through disregarding the fear of death.”

The most important Celtic crop festival was Samhain, or November Eve, at which time the worlds of the living and dead were permitted to mingle. At harvest time, sacrifices to pagan gods were made to assure passage through the winter. With the coming of Christianity to Ireland by way of St. Patrick and other missionaries beginning in the fifth century AD, pagan holidays began to blur with Christian, and in the ninth century, the better to encourage conversion, Pope Gregory’s calendar realigned church holidays to coincide with the old pagan festivals. Christmas was moved from the spring to coincide with the Roman festival of Saturnalia, and the Feast of All Saints now fell on November 1, encouraging an alternate kind of communion with the dead to compete with Samhain, which was never completely suppressed, and survives to the present day as Halloween.

Irish folklore was not at all diminished by Christian teaching, from which it often drew a good deal of inspiration. Old pagan gods were transmogrified into a delirious variety of fairy folk, while the Christian God and the devil not infrequently made sideline appearances. The Catholic Church made no real effort to discourage Irish folk beliefs, and the populace evidenced no inability to balance two supernatural belief systems. The resulting oral tradition became one of the most richly textured in the world.

Catholic monasteries in Ireland introduced the Roman alphabet and kept alive literacy and scholarship throughout the Dark Ages—some have gone as far as saying they saved civilization—and their transcription and preservation of Irish sagas and legends, as well as the production of extraordinary illuminated Latin gospels like the Book of Kells (circa 800) speaks to a profound love of language often regarded as the wellspring of a bottomless Irish capacity for storytelling. No other country of Ireland’s size has made such an enormous contribution to world literature, and no other can boast of four Nobel Prize–winning writers, all in the twentieth century: W. B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett, and Seamus Heaney. The achievement of the medieval scribes is all the more impressive in that it overlapped with more than a hundred years of Viking raids beginning in the early ninth century, in which monasteries were regularly sacked. Before they were absorbed into Irish society, the Vikings built settlements that would evolve into major cities, especially Dublin, Wexford, Limerick, and Cork.

The Irish language, like Scottish and Manx, is Celtic/Gaelic, descending from the same Indo-European roots. Middle English was introduced to Ireland in the twelfth century, but no form of English predominated in Ireland until the nineteenth century, and then only after centuries of English/Irish political and religious strife. Seven centuries of Norman and English rule began in 1169, when mercenaries invaded the island. The English Reformation set off a brutal period of Catholic suppression, including the confiscation of land and wholesale massacres. By the end of the eighteenth century, 95 percent of Irish land was owned by Protestants.

By the nineteenth century, Dublin, Ireland, was one of Britain’s largest cities and centers of trade, sometimes called the Second City of the British Empire. Its intractable problems with overcrowding, squalor, and disease were equally oversized and, in fact, among the worst in Europe. Death was a living presence, even if that grim vitality was expressed indirectly, through the sullen exertion of gravediggers, the unceasing procession of mourners, and the incessant writhing of worms.

On October 8, 1847, a letter from the local cleric Richard Ardille was published in the Dublin Evening Mail, addressing a perceived central issue: “The evil to be remedied, which I think demands the serious attention of the government, and of every person, is the practice that now prevails of having burial in church yards within the city, surrounded as they are by neighborhoods densely populated, the inhabitants of which are constantly inhaling an atmosphere noxious in its character and effect.” Ardille continued with some direct observations:

I have attended funerals where the remains of seven bodies were exhumed to make room for an eighth about to be interred; and I would ask any rational man if he could expect that a city could be healthy where such scenes were of frequent recurrence? In no country, save in Great Britain and Ireland, do interments take place within the walls of cities or towns. . . . On the continent of Europe such an offence against propriety is unheard of. Amongst barbarous natives, as they are termed, the dead are either consumed by fire, or interred at a distance from their dwellings; but in refined and civilized England the pernicious system is yet tolerated.

There was no proven connection between putrefaction in Dublin cemeteries and any outbreak of disease. But crowded cemeteries did produce noxious smells, which much occupied the minds of early nineteenth-century promulgators of “miasma theory,” ever anxious to find environmental—even meteorological—reasons for confounding health problems in congested urban centers. Disease, in the miasmic worldview, was, in essence, understood as the mysterious action of wafting phantoms. In the case of cemeteries, the ghostly analogy is particularly apt, for just beneath the pseudoscientific surface of miasma theory percolated ancient, stubborn superstitions about the fearful powers of the dead to reach out from their graves and weaken the living.

In point of fact, it was not uncommon for dead bodies in Victorian Dublin to leave their graves. When Bram Stoker was born, only fifteen years had passed since Britain’s Anatomy Act was made law, allowing corpses to be donated for medical dissection. Previously, surgeons were dependent on “resurrection men”—that is, grave robbers—to provide cadavers for study and instruction. Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery, Ireland’s largest, was a natural target. Two stone watchtowers had been built into its walls for nighttime surveillance, and they stand to the present day, their purpose already enshrined in Irish memory when Stoker was a boy. The Anatomy Act had been fiercely debated for years before its passage. The bodies ultimately liberated to laboratories were overwhelmingly procured from hospitals, jails, and workhouses, as they were all throughout Britain (Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1884 story “The Body Snatcher,” based on the notorious crimes of Burke and Hare in the 1820s, was set in Scotland). Much opposition to the anatomy law fell along class divides. The noted journalist and pamphleteer William Cobbett questioned whether the act was really necessary for the purposes of medical science. “Science? Why, who is science for? Not for poor people. Then if it be necessary for the purposes of science, let them have the bodies of the rich, for whose benefit science is cultivated.” Needless to say, Cobbett’s modest proposal was never considered, much less adopted. Fear and anxiety about nineteenth-century science would persist as an essential ingredient of the Gothic literary energies that would eventually catapult the name Bram Stoker to worldwide fame.

It is often said that death is a normal part of life, and this was especially true in Victorian Ireland. People mostly died as they were born—at home, amid familiar persons and surroundings. The processes of death were not clinically sequestered; in fact, a definite social stigma was attached to the very idea of dying “in hospital.” Not without cause, medical institutions were often seen, and feared, as de facto death houses, shelters of desperate and truly final resort. Life expectancy in midcentury Dublin was miserably short; to live much past what we now consider middle age could be a pleasant surprise in even middle-class households, and among the artisan classes and the poor an impossible dream. Grimmer still were the infant mortality rates. Nearly a quarter of all children born died before the age of five, and among the poorest of the poor, the death rates could approach half. Although infant fatality served to skew downward all life expectancy statistics, the overall numbers were dismal in any case. Many working-class children in Great Britain were routinely enrolled in so-called burial clubs at birth, to guard families against ruinous funeral expenses, or the shame of a pauper’s grave.

Mount Jerome Cemetery, Dublin, Stoker family burial site.

Cenotaph with Celtic serpent, Mount Jerome Cemetery. (Photographs by the author)

At the age of twenty-nine, Charlotte Matilda Blake Stoker (née Thornley) was an intelligent, educated, forward-minded woman from a military family in the northwest of Ireland. She married Abraham Stoker, a Dublin civil servant eighteen years her senior, in 1844; by 1847 the couple already had two children, William Thornley (born in 1845 and known as Thornley) and Charlotte Matilda (born in 1846, known as Matilda). Their third, Abraham Jr., familiarly and later famously called Bram, followed on November 8, 1847, at 15 the Crescent (now Marino Crescent), Clontarf, a seaside parish in north Dublin. Four more children would follow: Thomas (1849), Richard (1851), Margaret (1853), and George (1854).

The Stokers identified strongly with the Protestant Ascendancy, though just how far they ascended themselves during the children’s formative years is another matter entirely. Abraham was a product of the commercial artisan classes (his father manufactured corset stays) and the first in his family to achieve a foothold in the Dublin middle class, or at least step up to its lower and more precarious rungs in the civil service. His progress was hampered, however, perhaps due to a certain lack of personal and professional assertiveness, but also because of the escalating presence of Roman Catholics in the commercial and public spheres.

Bram Stoker came into the world midway through a century of scientific and technological change more rapid and destabilizing than human beings had previously experienced. The tension between religious and scientific worldviews was especially pronounced, and Stoker’s own intellectual development and literary output would amount to a lifelong juggling act of materialism versus faith, and reason against superstition. In the sciences, 1847 witnessed the births of Thomas Alva Edison and Alexander Graham Bell, the first use of chloroform as a surgical anesthetic, and the first sighting by telescope of a comet invisible to the naked eye.

In 1847, the world of arts and letters welcomed the premiere of Verdi’s opera Macbeth and saw the publication of Emily Brontë’s Jane Eyre and Charlotte Brontë’s Wuthering Heights,* two novels highly pertinent to Stoker studies for depicting the Gothic grip of childhood traumas. Interestingly enough, both books make references to vampires. In Jane Eyre, the title character, is kept apart from the man she loves, Edward Rochester, by his wife, Bertha, a raving madwoman locked in an attic and from there ruining everything. She reminds Jane of “the foul German spectre—the Vampyre” and is duly described like the fluid-fattened undead of folklore, with “a discoloured face,” “lips swelled and dark,” and “bloodshot eyes.” Vampires in the folk tradition were ruddy peasants; only in literature would they eventually achieve a deathly aristocratic pallor. Bertha growls and bites like an animal and, like many a vampire of legend, is ultimately destroyed by fire. In Wuthering Heights, the über-Byronic antihero Heathcliff, after having every other demonic epithet imaginable flung at him, finally prompts Nelly Dean, the narrator, to wonder (just about the time he is digging up the grave of his lost love), “Is he a ghoul, or a vampire?”

Undated portrait of Bram’s mother, Charlotte Stoker. Photographer unknown.

Abraham Stoker, Bram’s father (1865). Photographer unknown.

The same year, thirsty nocturnal creatures were the subject of the book publication of the rambling penny-dreadful serial Varney the Vampyre; or, The Feast of Blood by the anonymous and prolifically prolix writer James Malcolm Rymer. The absurdly attenuated narrative, luridly illustrated, occupied popular attention in much the same way as would television’s Dark Shadows—a similarly endless Gothic soap opera of the late 1960s, with a vampire named Barnabas Collins more or less standing in for Lord Francis Varney, in new installments five days a week. At some point many years later, Stoker would encounter a no doubt well-thumbed copy of Varney and closely adapt material for key scenes in Dracula.

Charlotte may easily have read Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights but almost certainly did not read Varney. Then again, she might not have had time to read any of them, for Charlotte’s pregnancy with Bram would have been anxious indeed. William Thornley had been born in the first year of an ominous potato crop failure, and Matilda during the second, worsening year. It was the beginning of a nightmarish national tragedy no one could have anticipated and would never forget. On Christmas Eve 1846, when Matilda was barely six months old, an alarmed official report was published in the House of Commons Sessional Papers, detailing miserable Irish scenes “such as no tongue or pen could convey” but nonetheless going on to describe a family of “six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead” who were “huddled in a corner with some filthy straw.”

The disturbing firsthand account continued, with descriptive details that evoked the language of Gothic romances but were based on fact: “I approached with horror, and found by a low moaning that they were still alive—they were in fever, four children, and what once had been a man. It is impossible to go through the detail. Suffice it to say, that in a few minutes I was surrounded by at least 200 such phantoms, such frightful spectres as no words can describe, either from famine or from fever. Their demoniac yells are still ringing in my ears, and their horrible images are fixed upon my brain.”

By the time Charlotte was pregnant with Bram, the effects of the potato famine were being fully felt throughout Ireland; starving and evicted tenant farmers flooded into the city slums and workhouses, and with them dysentery, famine fever, and typhus. Terrifying accounts reached Dublin from County Mayo, where workhouses had begun the inexorable transition into death houses. About the time of Bram’s conception, the Mayo Constitution reported the grim effects of fever: “In Ballinrobe the workhouse is in the most deplorable state, pestilence having attacked paupers, officers, and all. In fact, this building is one horrible charnel house. . . . The master has become the victim of this dread disease; the clerk, a young man whose energies were devoted to the well-being of the union, has been added to the victims; the matron, too, is dead; and the respected and esteemed physician has fallen before the ravages of pestilence, in his constant attendance on the diseased inmates.”

The Stokers endured the appalling health crisis within the bulwark of their Clontarf row house. Still standing, it has a deceptively simple façade, but its three stories are filled with handsome decorative moldings, marble fireplaces, and a distinctive bowed back wall not typical of Georgian construction; its rear windows give onto a long, sunken backyard accessible through the basement kitchen. Infant food prepared in this heavy-beamed room would have consisted mainly of gruels and porridges made of grain and water, and sometimes sugar. Commercial baby foods were still decades away, as was pasteurization. Milk, despite its nutritive benefits, was still a risky business. The basics of child nutrition weren’t even comprehended—fruits and vegetables, for instance, were widely considered unhealthy for the very young. Given this ignorance, the scourge of infant mortality and early childhood disease becomes much less surprising.

James Malcolm Rymer’s penny-dreadful serial Varney the Vampyre, published in 1847, the year of Bram Stoker’s birth.

Ironically enough, the very kitchen that provided less-than-sumptuous sustenance to the three Stoker children would, in the early twentieth century, serve as the closely guarded hiding place for an unparalleled visual feast: the Russian crown jewels, acquired as collateral for a $25,000 loan by the Irish Republic to the Bolsheviks, who had no practical use for such an extravagant reminder of the Romanovs. In 1920, Catherine Boland, mother of Irish patriot Harry Boland (who helped broker the loan), was called upon to secrete the hoard at 15 Marino Crescent, which she had recently purchased. It was not an ostentatious house and would not draw attention. The jewels included the legendary crown created for Catherine the Great in 1762, adorned with five thousand Indian diamonds, pearls, and the second-largest spinel in the world. The precious stash remained hidden at Bram Stoker’s birthplace until 1950, its location revealed to no one until after the Soviet Union repaid the original loan. This outlandish but true story was not unlike an incident in one of the adventure novels Stoker loved as a boy and would eventually write.

Above the kitchen, the first floor boasts a long entry hall leading to a reception parlor flanked by a formal sitting room and dining room. The upper two floors contain several bedrooms, though no one has ever determined exactly which were occupied by which of the three Stoker children. Bram might have shared a room with his brother, or might well have had his own dedicated sickroom-nursery. It has been imagined that Bram’s room might have faced the street, overlooking the handsome iron-gated park opposite, with a glimpse of the Irish Sea beyond, fueling his dreamy imagination, the park itself being the spot to which he remembered being carried to lie “amid cushions on the grass if the weather was fine.”

However idyllic, this is also unlikely. Episodic memories before the age of two (the approximate time the family moved from the Crescent) are universally irretrievable, subject to the well-studied phenomenon of infantile amnesia, a normal part of childhood development. Bram’s memories of cushions and grass had their origins later and elsewhere. Also, the Clontarf waterfront, which previously attracted swimmers and sunbathers, was now becoming an odiferous slobland at a time when “vapors” and “miasmas” were blamed for all manner of disease; in later years, owing to concerns about sewage dumping, the sea frontage would be completely landfilled. Despite its close proximity, the mouth of the Liffey was hardly the place a concerned parent would take a sickly child.

The precise onset of Bram Stoker’s debilitating illness is not recorded, but his baptism was delayed nearly seven weeks, until December 30, and then conducted at the Protestant Church of St. John the Baptist, which still half-stands in Clontarf as a picturesque ruin. The site is appropriately suggestive of the Gothic masterpiece Stoker would publish fifty years later. Dracula is the overwhelming reason for most people’s interest in Bram Stoker today, and since Stoker chose to leave us no full accounting of his own life, only his fictions, it is not surprising that biographers, critics, and essayists have long employed imaginative (and often overreaching) speculation to link the king of vampires to a sickness and symptoms initially as baffling to onlookers as those endured by Dracula’s victims.

Vampirism involves bloodletting, which, in the mid-nineteenth century, was an ancient medical practice still widely used. Henry Clutterbuck, MD, whose “Lectures on Blood-Letting” appeared in the London Medical Gazette in 1838, told his readers that “blood-letting is a remedy which, when judiciously employed, it is hardly possible to estimate too highly. There are, indeed, few diseases on which, at some periods, and under some circumstances, it may not be used with advantage, either as a palliative or curative means.” The most cursory look at the medical literature of the day confirms the universality of the prescription, even for conditions like childhood asthma and adolescent acne. Clutterbuck especially advocated “prompt and vigorous application of the remedy” to “inflammatory affections of the brain that are so common in early life.” The concept of “brain fever” in the 1800s was remarkably elastic and seems to have comprised everything from meningitis to simple moodiness. A child so afflicted “loses his appetite, complains of thirst, is languid and spiritless, his sleep is scanty and disturbed,” Clutterbuck observed.

Bram Stoker’s Clontarf birthplace. (Photograph by the author)

A languid boy like Bram Stoker, showing signs of chronic motor weakness, would have been a prime candidate for phlebotomy. Bloodletting physicians no longer invoked the principle of balancing “humors,” an idea dating from antiquity, but the similarly ancient idea of “plethora,” or excess blood, as a cause of illness was still very much in vogue. If Bram was treated by doctors, it would have been at home. Hospitals, especially during the time of famine fever, were resorted to cautiously, if at all. Bloodletting was performed by three means: by lancet, by “cupping” with a heated glass that created a siphoning vacuum, and by medicinal leeches. Great Britain at the time imported nearly forty million medicinal leeches annually from France. Since Dracula himself is described by Stoker as “a filthy leech, exhausted in his repletion,” one wonders about his personal experience or observation of the bloodsucking worm, or how a helpless boy might process or reconcile the ritual threat of having of his flesh being penetrated and bled by an imposing male figure wielding a lancet. When Stoker’s alter ego Jonathan Harker wanders into a forbidden room at Castle Dracula and meets the Count’s undead wives, he experiences a powerful erotic thrill as he anticipates imminent penetration by bladelike teeth:

The skin of my throat began to tingle as one’s flesh does when the hand that is to tickle it approaches nearer—nearer. I could feel the soft, shivering touch of the lips on the supersensitive skin of my throat, and then the hard dents of two sharp teeth, just touching and pausing there. I closed my eyes in a languorous ecstasy and waited—waited with beating heart.

There is an old adage, “When the blood flows, the danger is past,” which goes a long way to explain ancient practices of human and animal sacrifice, and the relief of sexual tension through blood fetishism. As a young man, Stoker would be powerfully attracted to the poetry of Walt Whitman, who wrote almost ecstatically about bleeding in Leaves of Grass: “Trickle drops! My blue veins leaving / Oh, drops of me! Trickle, slow drops . . .”

Bloodletting, with its inevitable relationship to vampires, is not only a possibility in Bram Stoker’s early life but a probability. For all the nineteenth-century advances in anatomical studies (considerably abetted by grave robbing) and surgery, when it came to healing the sick, early nineteenth-century doctors had an extremely limited bag of tricks. A well-regarded doctor’s reputation typically required a comforting bedside manner, a judicious dose of bluster and professional mystification, and a certain generosity with opium, not to mention a surfeit of sustained good luck.

And leeches.

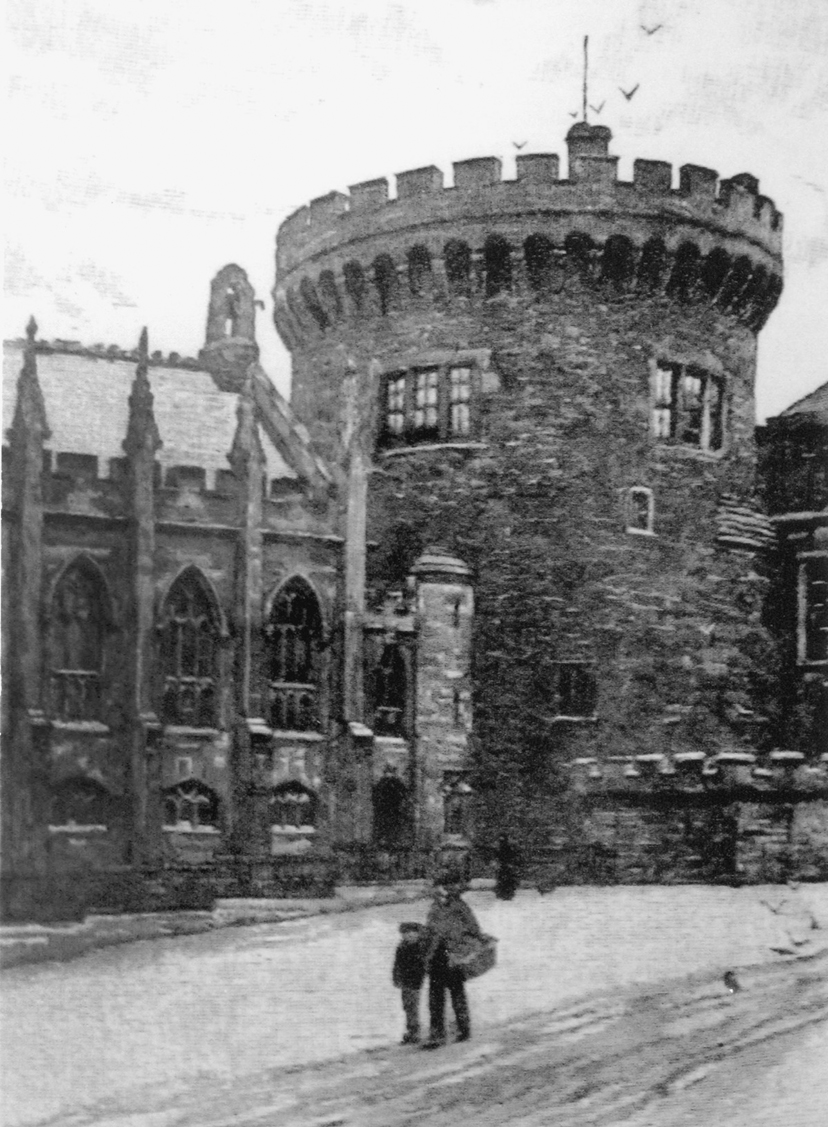

Befitting a boy whose childhood was destined to be shaped by fairy tales, his father, Abraham Stoker Sr., actually worked in a castle—Dublin Castle, the seat of government administration, where he was a career civil servant. The vestiges of an impressive Norman fortification no doubt carried strong legendary associations for his son; the castle’s medieval Record Tower (the oldest surviving part of the much-renovated complex, dating to 1204) once displayed the freshly impaled heads of Irish traitors on its battlements. Still vigorous in middle age, the elder Stoker is said to have walked to work each day, a brisk daily journey of an hour and a quarter from Clontarf, down the North Strand Road and into the commercial hurly-burly of Talbot Street, then down Sackville Street and over the Carlisle Bridge (today O’Connell Street and the O’Connell Bridge) into the city center on the south bank. Family accounts of Abraham’s daily perambulations may well be exaggerated, or refer to a later time when the family lived in the city center. The nearly three-mile walk would be almost impossible as a daily matter in winter, and Clontarf was one of the first Dublin suburbs to be serviced by horse-drawn omnibuses and trams, as well as trains. But the story does illustrate the Stoker family’s characteristic emphasis on discipline, thrift, and self-reliance.

Charlotte Stoker was a practical, no-nonsense woman who nonetheless had a countervailing and lifelong weakness for things irrational, fantastic, and macabre. County Sligo, where she was raised, is one of Ireland’s richest repositories of Celtic folklore, and Charlotte partook of a vibrant oral tradition—the same legacy that would powerfully inspire Ireland’s greatest poet and folklorist, William Butler Yeats, who spent much of his childhood in Sligo and claimed it as his muse and spiritual home. Northwest Ireland can boast of the country’s most romantic and soul-stirring landscapes, including the purported Neolithic rock-pile tomb (or cairn) of Queen Mebh or Maeve, her name meaning “she who intoxicates.” Mebh is the warrior monarch of Celtic mythology commemorated in English literature as the fairy Queen Mab evoked by Edmund Spenser, William Shakespeare, and Percy Shelley. Legend has it that Mebh is buried upright, alert and ready to take on enemies, even after death.

Dublin Castle in the nineteenth century.

Charlotte claimed to have personally heard the wail of the Bean-sídhe, or banshee, the ghostly Irish harbinger of mortality, heralding her own mother’s death. Some modern observers have linked the rise of banshee legends in the eighteenth century to the collective grieving of traditional Irish culture under an increasingly heavy Protestant heel. According to Yeats, “An omen that sometimes accompanies the banshee is the coach-a-bower (cóiste-bodhar)—an immense black coach, mounted by a coffin, and drawn by headless horses driven by a Dullahan [headless coachman]. It will go rumbling to your door, and if you open it . . . a basin of blood will be thrown in your face.” Haunted coach rides are a common motif in horror fiction, perhaps archetypally so in Dracula, as a living-dead figure associated with blood and with an affinity for coffins drives a mysterious coach with four black horses through wildest Transylvania.

When young Charlotte Thornley wasn’t hearing banshees, she might have occupied her time like the voraciously literate heroine of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (1818), when coming-of-age popular reading for young women included the Gothic novels of Ann Radcliffe (The Mysteries of Udolpho, 1794, and The Italian, 1797), Matthew Lewis (who had barely come of age himself when he published The Monk at the age of nineteen in 1796), and the Irish cleric Charles Robert Maturin (Melmoth the Wanderer, 1820). For Irish Protestant readers, these books distilled the complicated sentiments of long sectarian strife. The Gothic novels portrayed Catholicism with a lurid—and alluring—savagery. The cruel debaucheries of villains like Ambrosio, the lustful Capuchin in The Monk (some of whose description and demeanor would be appropriated almost verbatim in Stoker’s delineation of Count Dracula), were sensationally attractive to readers like Charlotte, and later her son, exuding all the dependable fascination of the forbidden, a dynamic the Irish historian R. F. Foster describes as “a mingled repulsion and envy” for “Catholic magic.”

Charlotte also read the works of Edgar Allan Poe, and near the end of her life would compare her son superlatively to the world-famous author of Tales of Mystery and Imagination. “Poe,” she would write in 1897, upon the publication of Dracula, “is nowhere.” That is saying much, since the terrors of both “The Masque of the Red Death” and “The Premature Burial” were very nearly eclipsed by the events of Charlotte’s own childhood. As a thirteen-year-old girl in Sligo, she had personally witnessed the horrors of the 1832 cholera epidemic that claimed more than twenty-five thousand lives. At Bram’s request, she put the story to paper in 1873.

In the days of my early youth so long ago . . . our world was shaken with the dread of the new and terrible plague which was desolating all lands as it passed through them. And so regular was its march that men could tell where it next would appear and almost the day when it might be expected. It was the Cholera, which for the first time appeared in Western Europe. And its utter strangeness and man’s want of experience or knowledge of its nature, or how best to resist its attack, added if anything to its horrors.

British landlords and Roman Catholics provided vampire metaphors for Irish political cartoonists in Victorian Ireland.

Charlotte knew how to tell a tale, and the written version of the chilling oral account she gave to her children included the italicized inflections she must have given it vocally, building suspense and gooseflesh with equal calculation: “But gradually the terror grew on us, as time by time we heard of it nearer and nearer. It was in France, it was in Germany, it was in England, and (with wild affright) we began to hear a whisper pass[:] ‘It was in Ireland.’ ”

Sligo was one of the worst-afflicted areas. Charlotte’s later reading of Poe’s ruminations on live burial would no doubt have triggered memories of a specific victim: “One I vividly remember, a poor traveler was taken ill on the roadside, some miles from the town, and how did those Samaratines tend him[?]” she asked. “They dug a pit and with long poles pushed him living into it and covered him up alive. But God’s hand is not to be thus stayed and severely like Sodom did our city pay for such crimes.” In total, five-eighths of Sligo’s citizens would perish.

Premature burial, or its threat, especially haunted her. She recollected two instances of souls who narrowly escaped the fate. One was a woman whose husband recognized her red neckerchief; she had already been piled over with corpses awaiting a mass grave. Another was a man who awoke from a deathlike stupor only when undertakers attempted to break his legs to fit an undersized coffin.

“One house would be attacked and the next spared,” she wrote. “There was no telling who would go next, and when one said ‘good-bye’ to a friend, he said it as if forever.” This was vividly demonstrated when a family the Thornleys visited one night were dead—and buried—the following morning. She remembered throwing a jug of water on a persistent coffin maker who would not stop banging at the door.

Cholera brings on a hideous death, beginning with fever and cramping, blue and puckered lips, then uncontrollable and fatal diarrhea. The disease was all the more frightening because the exact means of transmission—contaminated drinking water—was then unknown, and would remain unknown until the 1850s. In 1832, censers of burning tar and other substances were employed, much as they were during medieval plagues, in a desperate attempt to purify the air. Plates of salt moistened with vitriolic acid were laid outside windows and doors.

All the Thornleys, including Charlotte, took a daily morning dose of ginger-thickened whiskey, and she believed the nostrum was largely responsible for her family’s survival. Without this desperate, home-mixed concoction, “no one moved a yard.” The Jesuit priest Theobald Mathew of Cork, later one of the great figures of the nineteenth-century temperance movement, had nothing to offer the sick and dying but Irish whiskey. Elsewhere, opium was liberally used. Those tending to the sick inexorably sickened themselves. “The nurses died one after another,” Charlotte wrote, “and none could be found to fill their places but women of the worst description, who were always more than half drunk.” The constant sound of bells attached to the cots of the dying and the carts conveying the dead would never leave Charlotte’s memory.

Famine in nineteenth-century Ireland, personified as malignant invading phantom.

At the height of the epidemic the entire Thornley family fled Sligo and narrowly escaped death, not from the disease but from the wrath of a mob outside of Donegal who dragged them from their carriage, determined to “burn the cholera people” in a fiery exorcism atop their own luggage.

In 1971, Tom Stoker’s great-grandson Daniel Farson, a colorful London journalist and television personality, consulted with Hammer Films, the British studio that had already produced seven Dracula-inspired movies and was now interested in developing a biographical drama based on Stoker’s life. Farson shared some additional family lore regarding Charlotte’s cholera ordeal, omitted from her written account but vividly recalled by Farson’s own grandmother—that “on one of the last, desperate days” of the epidemic, the Thornley family was under siege by a zombie-like horde of cholera victims, and Charlotte was forced to take extreme measures. Hammer screenwriter Don Houghton wrote a treatment involving young Bram directly in the trauma by moving the action to a fictional cholera epidemic of the 1850s when Charlotte is already a mother, fiercely protecting her son. The climactic scene strikingly anticipated the house-under-siege motif of countless modern horror films:

A man, his face yellow, drawn and ghastly . . . his teeth bared in fury, appears at the window, forced forward by the mob behind him. In terrible detail the child sees the horror of what happens next. The MAN thrusts his arm through the glass to tear at the boards barring the window. The arm, white with disease, gropes into the room, like an ugly tentacle, wavering like a monstrous worm.

On the table in front of CHARLOTTE there is a knife. In a fit of angry panic, she takes hold of it. The child screams as she hacks at the arm. Blood spatters over her. The fingers tear at her fingers as she continues to slash at it.

In what Houghton calls “the final, terrible picture,” Bram backs away screaming from the squirming, severed arm that has fallen to the floor, and his mother rushes to comfort him. But it does no good, for “her clothes are red with gore. . . . She is like a spectre of death.”

Farson’s grandmother put an ax in Charlotte’s hand in place of a knife, and it’s a bit surprising that Houghton chose to pull the extra visual punch. It would have been a perfect Hammer moment. But for all of its melodramatic excess, the never-filmed scene underscores a certain psychological truth. Young children can be acutely attuned to parental anxiety, with lasting emotional effect. And, in a fact previously overlooked by Stoker biographers, Bram’s early bonding with his mother did take place during a cholera epidemic, one even more deadly than the 1832 plague, reaching Dublin during the winter of 1847–48. Only days before Bram’s birth, Charlotte could have read an ominous account in the Dublin Evening Mail headlined CHOLERA MORBUS. The correspondent in Malta described the spread of “this scourge of mankind” from the Black Sea and warned that “experience has proved the utter inutility of resorting to quarantine.” More than thirty-five thousand Irish would perish, a death toll exacerbated in a population already weakened by hunger and fever.

It is also surely significant that Stoker’s seven-year illness coincided almost exactly with the worst years and immediate aftermath of the Great Famine, Ireland’s towering trauma in a notoriously tumultuous history. His birth year became known as “Black ’47,” with the total failure of the potato crop. By the mid-nineteenth century, Ireland’s predominantly Catholic population of rural tenant farmers had become almost totally dependent on the potato for subsistence. Many earned no money at all, working as indentured sharecroppers in exchange for primitive housing and meager patches of land on which they could cultivate potatoes.

Scientific plant breeding was then unknown, and the tubers had no immunity against a virulent fungus, Phytophthora infestans, that had crossed the ocean from North America on steamships. For all that was understood about fungal life in 1847, the organism might as well have been supernatural in origin. It was believed that funguses were—impossibly—a living by-product of organic decomposition, a concept with roots in medieval alchemy (the idea, for instance, that flies were directly generated by rotting meat). The mechanism of fungal parasitism amounted to a kind of vegetable vampirism: telltale surface marks, easily overlooked, yielded quickly to a fatal corruption.

By modern consensus, a million Irish perished, most not from hunger but from diseases attacking the weakened and malnourished. “The actual starving people lived upon the carcasses of diseased animals, upon dogs,” the House of Commons Sessional Papers recorded, “and even in some place[s] dead bodies were found with grass in their mouths.” Over and over, those who were spared starvation would hear harrowing stories of death, and living death. In the countryside, shallow mass graves were rifled by scavenging animals. In Dublin, a few months before Stoker’s birth, Cork Street Hospital was forced to close its doors against new fever victims. A local journal reported that “among the close pestilential atmosphere of crowded lanes and alleys,” victims would “writhe and perish . . . dragging all who come in contact with them to share their untimely graves.”

The tragedy was compounded by continued large shipments of Irish grain to England, despite the need for food at home. The perception that official British policy was deliberately worsening the famine stirred resentment and outrage, and still fuels historical debate. In early 1847, with especially chilly bureaucratic sangfroid, a medical officer reported to the Poor Law commissioners that “it is a well-known fact that many dying persons are sent for admission [to hospitals and workhouses] merely that coffins may be obtained for them at the expense of the Union.”

Lady Jane Francesca Wilde, the mother of Oscar, was a fiery nationalist polemicist and poet who published under the pen name Speranza. In 1848, she wrote “The Famine Year,” protesting unionist inaction:

Fainting forms, hunger-stricken, what see you in the offing?

Stately ships to bear our food away, amid the stranger’s scoffing.

There’s a proud array of soldiers—what do they round your door?

They guard our master’s granaries from the thin hands of the poor.

The years of Bram Stoker’s childhood were filled with oral accounts of horrors attending the famine. Most poignant and tragic were the now-legendary tales of the “coffin ships,” which carried typhus and cholera along with desperate immigrants headed for North America. Many never arrived alive; as many as a hundred thousand refugees were interred in one mass grave at a St. Lawrence River quarantine station in Quebec. Bram undoubtedly heard these stories, told and embellished like folktales, and later could have read published first-person accounts of doomed passengers like Gerald Keegan and his new bride, Aileen, written in 1847:

[30 April] The fever spreads and to the other horrors of the steerage is added cries of those in delirium. While coming from the galley this afternoon, with a pan of stirabout for some sick children, a man suddenly sprang upward from the hatchway, rushed to the bulwark, his white hair streaming in the wind, and without a moment’s hesitation, leaped into the seething waters. He disappeared beneath them at once.

[13 May] . . . I saw a shapeless heap move past our ship on the outgoing tide. Presently there was another and another. Craning my head over the bulwark I watched. Another came, it caught in one cable, and before the swish of the current washed it clear, I had caught a glimpse of a white face. I understood it all. The ship ahead of us had emigrants and they were throwing overboard their dead.

Aileen lasted only a few days in quarantine, Gerald only six weeks. His heartbreaking journal, preserved by his uncle, was finally published in 1895 as “The Summer of Sorrow.” Stoker may or may not have read it, but in any event would have known the basic story by heart from childhood. Not long after, he would incorporate the log of a doomed ship into Dracula, in which a literal “coffin ship” would return to British shores, doomed not by famine or plague but by a spectral figure embodying both terrible hunger and pestilential dread.

Outright starvation did not impact the city the way it did the countryside, but concurrent epidemics knew no geographic boundaries. A concern about unwholesome waterfront air and row-house crowding may have been the reason Charlotte and Abraham chose to move farther inland, although simple financial pressure or the need for larger quarters may also have played a role. As renters, rather than leaseholders, their continued tenancy could have been subject to rising rents or landlord whim. In any event, around the time of Thomas Stoker’s birth in 1849, the family relocated about a mile and a half northeast to Killester, and after the birth of Richard Stoker in 1851, to Artane Lodge in nearby Donneycarry.

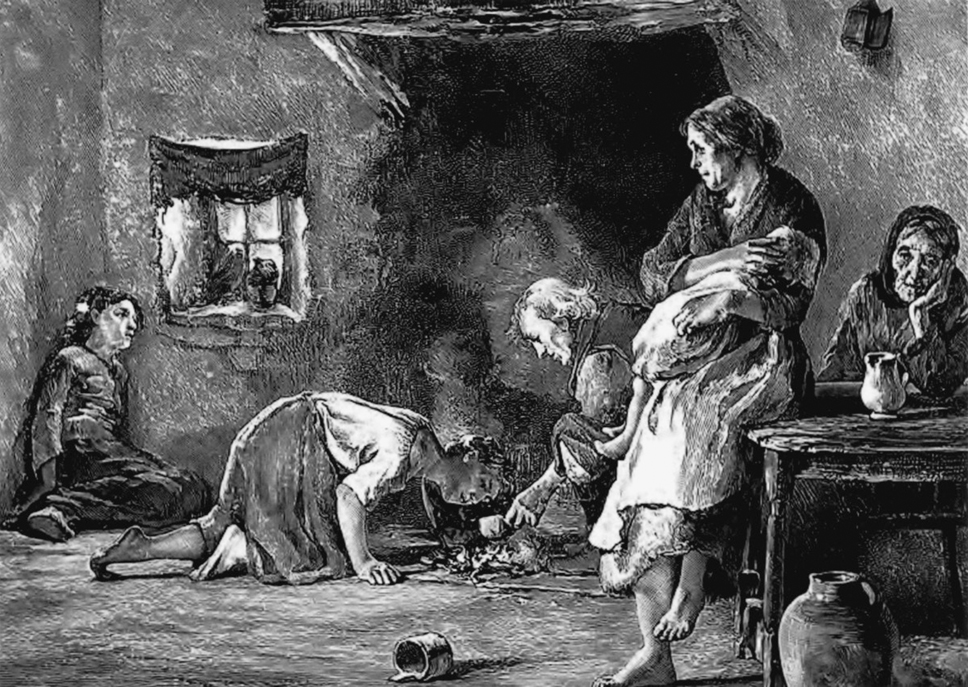

The interior of a peasant’s hut during the Great Famine.

Virtually nothing is known of the Killester address, save for its entry on baptismal records, but Artane Lodge was a residential villa—in the sense of a freestanding house, not because of any grandeur—set on an open parkland that is now the Clontarf Golf Club. If nothing else, the location met Victorian standards for healthy air at a time when miasma theory was still taken on faith. Abraham’s father had roots in the area, and family connections may well have facilitated the move. Whether the change was for Bram’s immediate benefit or not, his childhood incapacitation apparently persisted in three separate homes.

Bram never contracted cholera, or famine fever, or any other disease or condition (such as a spinal injury) that might medically account for his inability to walk. Rheumatic fever weakens the heart, making his later exemplary health and athleticism problematic at best. Asthma creates breathing problems, not immobility. Psychological or psychosomatic conditions understandably provide more fertile ground for sleuthing. Since vampires circle endlessly around any attempt to uncover Stoker secrets, the phenomenon of paralyzing night terrors, long posited as a source of incubus and vampire legends, immediately springs to mind. Night terrors primarily trouble children, are believed to have their roots in developmental biology, and usually disappear as the child matures. Autohypnosis and forms of deep meditation can also freeze the mind and body, but where does a Victorian toddler pick up the techniques? Nonetheless, we know (maddeningly) that Stoker had a lifelong interest in mesmerism and hypnosis, but little else. And somewhere in the vast spectrum of twilight consciousness called hypnagogia, there might well be the key to understanding strange states of suspended animation, but the esoteric subject is nearly as slippery and daunting as the comprehension of consciousness itself.

Sigmund Freud famously cured patients of what used to be known as hysterical paralysis, a condition formally called conversion disorder, in which neurological symptoms such as motor weakness, muscle spasms, aphasia, or even blindness manifest, all in the absence of physical disease. With Josef Breuer, Freud published Studies on Hysteria in 1895; the book introduced the concept of the unconscious as a distinct substratum of the mind and posited the “talking cure” to relieve such symptoms by bringing buried conflict or trauma to conscious examination. Although Freud’s hysteria studies focused almost exclusively on women, conversion disorders are now recognized in men, but very uncommonly in young children of either sex. They are believed to occur most often in response to strict family or institutional structures in which normal emotional expression is repressed, or dysfunctional interactions denied.

That Bram Stoker’s paralysis might have been the result of childhood sexual abuse or incest has been summoned up by a number of commentators, often achieving a near-parody of armchair psychologizing. Certainly, the argument goes, a forced or furtive glimpse of his mother menstruating would have triggered the archetypal image of the vagina dentata—and neatly explain his later literary evocation of the engulfing/penetrating vampire’s mouth, oozing with blood. Alternately/concurrently, could paralysis be a defense reaction to murderous Oedipal rage directed at his brothers or his father?

The statement “The Irish are impervious to psychoanalysis” (or that the Irish constitute “one race of people for whom psychoanalysis is of no use”) is often attributed to Freud, along with the equally provocative assertion that he split the world into two categories: the Irish and the non-Irish. In reality, there is no proof that he wrote or said any such thing, but the legend lingers, and especially colors the often frustrating challenge of illuminating the inner life of Bram Stoker. The attraction of Freudian theories for Stoker psychobiographers is understandable; many of the twentieth-century stage and film adaptations of Dracula were quite consciously molded around Freud’s ideas, but the approach can be anachronistic and off target if one’s goal is to understand the Victorian world as it understood itself. Ideas about menstrual exhibitionism in Victorian homes aside, much of Freud’s work rests on universal truths. For instance, it is simple fact, not psychosexual theory, that a child first experiences his mother as food and is vulnerable to adult harm, or that for centuries children have been cruelly exploited and abused, and initiated into the dangerous adult world through frightening stories of infanticide and cannibalism. A child’s first smile, it should be remembered, is an automatic reflex, a survival mechanism to reinforce parental care and feeding.

Parenthood in the best of circumstances is stressful, and young children can be preternaturally attuned to parental anxiety. In the case of Bram Stoker and his mother, their early bonding was clearly fraught with fearful emotions, the potential of devastating disease, and the common reality of infant mortality. Charlotte was almost constantly pregnant from 1845 to 1854, with all the attendant dangers to herself and her children. Statistically, she should have expected to lose at least two children to stillbirth, complications of birth, or early childhood sickness. Each surviving child only increased fears for the next. If her pregnancy with Bram had been especially difficult, or his birth an ordeal, extra or even excessive vigilance on Charlotte’s part would be a completely natural response.

Overprotection of Victorian children took some fascinating if surprisingly underexamined forms. A universal childhood custom in Ireland and throughout Western Europe was the practice of dressing both girls and boys in female attire until approximately the age of seven. The practice continued far beyond any practical utility—in toilet training, for instance. Maintaining boys in a sexually undifferentiated or aggressively feminized state until “breeching” into shorts or trousers was a curious, long-lived, and still remarkably underexplored historical custom. Laurence Sterne, in The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759–67) treated the subject humorously, as a kind of tug-of-war between husband and wife, each rationalizing his or her own reticence in finally dealing realistically with their child’s sex. “We defer it, my dear,” Tristram quotes his father, “shamefully.” They both try to convince themselves that the boy looks just fine dressed as he is. And might not male clothing be “aukward”? “When he gets these breeches made,” the father frets, “he’ll look like a beast in ’em.”

Nonetheless, the breeching ritual marked the transference of a child from the mother’s ethereal, domestic realm to the father’s beastly, worldly domain. Some mothers took proactive steps to delay this fall from grace. Not a few Victorian boyhood photographs depict shoulder-length ringlet curls and petticoats under the skirts. Whatever her conscious motivation, many a Victorian mother succeeded admirably in tricking out her darling son like date bait for Lewis Carroll. Oscar Wilde is a case in point. A tinted daguerreotype of Wilde at the age of two shows him dressed in an ornate, off-the-shoulder royal-blue frock, his cascading hair artificially curled. One acquaintance, especially catty, published a memoir after the death of both mother and son maintaining that Lady Wilde, desperate for a daughter, kept Oscar in female dress until the age of ten, transforming him for all practical purposes into “a neurotic woman.”

One Wilde family chronicler found a justification for cross-dressing in Irish folklore: he reported that in parts of rural Ireland boys were traditionally disguised as girls to protect them from being spirited off by the fairies, “for of course, the fairies are only interested in little boys.”† It is intriguing that the first recorded use of the word “fairy” as a homosexual slur occurred in 1895, the same year as Wilde’s notorious trial for “gross indecency with male persons.” In the two short decades following Wilde’s downfall, hundreds of years of tradition were overthrown as parents became acutely vigilant for any sign of effeminacy in their sons. The practice of dressing young boys in skirts all but ended around World War I, except for the yet-enduring custom of christening gowns.

Oscar Wilde as a child.

What does a boy think about, immobilized for years as a kind of fragile female doll? “I was naturally thoughtful and the leisure of long illness gave opportunity for many thoughts which were fruitful according to their kind,” Stoker tells us, which isn’t much. A healthy child would be expected to engage in normal play, but in Stoker’s case he would have been a helplessly passive observer of normally abled children and adults, all of them costumed as female except his father. Among the imaginative fruits of Bram Stoker’s peculiar early years may have been a lifelong fascination with gender instability and ambiguity. Indeed, near the end of his life he would devote a large section of Famous Impostors (1910) to the theory that the “virgin” Queen Elizabeth could have been a man, deliberately raised all her life as a girl in an elaborate plot to secure the throne—an extraordinary gambit, even by the conspiracy standards of the Tudors.

Modern critical studies of Dracula have been dominated by psychosexual investigations into the book’s multiplicity of gender transgressions that all bubble over into horror: “new women,” mannishly assertive, send the male characters into stereotypically “female” hysterics, while the title character, supernaturally frozen in an erotic limbo, absorbs and mingles transfused male fluids sucked from female veins. In his fourth-to-last novel, The Man (1905), a man obsessed with having a son tells his dying wife that the daughter she has just delivered is a boy, whom they name Stephen. The father thereafter experiences “a certain resentment of her sex,” though “he never, not then nor afterwards, quite lost the old belief that Stephen was indeed a son. . . . This belief tinged all his after-life and moulded his policy with regard to his girl’s upbringing. If she was to be indeed his son as well as his daughter, she must from the first be accustomed to boyish as well as to girlish ways. This, in that she was an only child, was not a difficult matter to accomplish.”

Charlotte’s forceful personality also raises questions about her own influence on Bram’s early perception of sex roles and about who actually wore the trousers in the Stoker household. Although the word “mannish” is not used in any family reference, it is clear that Charlotte was not a typical Victorian mother, was outspoken on public issues in a manner more typical of men, and had a dominating influence in her family. Nearly two decades younger and more vigorous than her spouse, Charlotte is described by Stoker editor and critic Clive Leatherdale as “a handsome, strong minded woman who, if she could see no ambition in her husband, was determined to invest it in her sons.” Abraham Stoker would be warmly remembered by family members, but not for a forceful personality or rising career achievements. The first of his family to break above the artisan class, Abraham settled into decades of career complacency as a junior clerk at Dublin Castle between 1815 and 1837, when he finally became an assistant clerk, and only applied for the position of senior clerk in 1853, twelve years before his retirement. This final advancement came amid the pressures of a growing family and the births of their final three children. Certainly, Charlotte would have shared in her husband’s decision, if not demanded it. According to Daniel Farson, his grandmother Enid (married to Thomas Stoker in 1891) “was not a fanciful woman and told me that the family were in awe of Charlotte if not actually afraid of her. When one of the boys failed to come in first in an examination, Charlotte did not conceal her resentment, even though he came second out of a thousand.” Charlotte’s identification with male striving is further evidenced by the opinion of her grandniece Ann Dobbs that she “didn’t care a tuppence” about her own daughters’ schooling and by her own published opinion that, to be honest, female education was mostly a practical matter of “matrimonial speculation.”

Above all, Charlotte believed passionately in the power and importance of language and literacy. A man’s mind without language, she wrote, “is a perfect blank; he recognizes no will but his own natural impulses; he is alone in the midst of his fellow-men; an outcast from society and its pleasures; a man in outward appearance, in reality reduced to the level of brute creation.” Words, to Charlotte, were an essential component of Christian salvation. Take, for instance, deaf mutes (their education became one of her favorite causes), who, through their affliction, could have “no idea of a God.”

Fully half of Ireland was illiterate in the mid-nineteenth century. The famine spurred a huge interest in the teaching of reading, which, increasingly, was understood as a necessity for nonagrarian employment and emigration. Outside the cities, children often learned to read under the charitable auspices of church-run “hedge schools,” so called because many classes were conducted outdoors, or in barns. In urban areas, paid tutors found themselves in high demand. A parent like Charlotte, with a keen interest in education, might well have taken on the responsibility herself.

There are few activities better suited to engaging the attention of an invalid child than reading, and it is safe to assume that Bram Stoker’s early years were occupied by storytelling to a greater degree than those of his normally active siblings. Abraham Stoker proudly collected books, and all manner of reading material would have been at the disposal of Charlotte or the nurse. The Bible, of course, was the central book in a Protestant home (where the Stokers, typical of their class, offered daily prayer), though its vocabulary and diction would present difficulties for children of three and four; Bram was not presented with a personal copy until the age of ten.

However, illustrated chapbooks of all descriptions supplemented the standard textbooks and the Bible, in school and out. According to Yeats, it was a rare Irish household that lacked chapbooks of fairy tales: “They are to be found brown with turf smoke on cottage shelves and are, or were, sold on every hand by the pedlars, but cannot be found in any library.” Among the most popular titles were The Royal Fairy Tales, The Hibernian Tales, and The Legends of the Fairies. By the time of Stoker’s birth, most of the classic German and French fairy tales were readily available in English. Charles Perrault’s Tales of Mother Goose, including “Little Red Riding Hood,” “The Sleeping Beauty,” “Puss in Boots,” “Cinderella,” and “Bluebeard,” had been in translation since 1697. “Beauty and the Beast” by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont appeared in English almost immediately after its French publication in 1756. Edgar Taylor had first translated the Brothers Grimm as German Popular Stories in 1823; Edwin Lane brought The Arabian Nights to English-speaking shores in 1840; Mary Smith translated Hans Christian Andersen’s Wonderful Stories for Children in 1846.

The Famine years were a mordantly appropriate time for fairy tales, since so many of them are about families and children struggling with hunger. The parents of Hansel and Gretel cannot provide food for their children, and so abandon them in the woods, where they meet an even hungrier nemesis, a cannibal witch. “The Juniper Tree,” sometimes called “My Mother Slew Me; My Father Ate Me,” is one of the most disturbing tales in the Grimm canon. A wicked stepmother kills the boy she hates, then serves him up as a stew to his clueless father. The more he eats the boy’s flesh, the more ravenous he becomes. In the opening lines of “The Children in the Time of the Famine,” a mother gets to the point without artifice or indirection: “There once lived a woman who fell into such deep poverty with her two daughters that they didn’t even have a crust of bread to put in their mouths. Finally they were so famished that the mother was beside herself with despair and said to the older child: ‘I will have to kill you so that I’ll have something to eat.’ ”

Such tales would later inform Stoker’s depiction of a supremely menacing father-figure driven by blood famine from his native land. Echoing a theme of many fairy tales, the threatened characters of Dracula are predominantly orphans.

Endangered children are less often emphasized in traditional Irish stories than are childlike adults. In the view of Lady Wilde, this is only appropriate, since the “mythopoetic faculty” exists “naturally and instinctively, in children, poets, and the childlike races, like the Irish—simple, joyous, reverent, and unlettered, and who have remained unchanged for centuries, walled round by their language from the rest of Europe, through which separating veil science, culture, and the cold mockery of the skeptic have never yet penetrated.” Naïve, wonder-filled adults appeared in the first major collection of Irish lore, T. Croften Croker’s Irish Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland, published in three volumes between 1825 and 1828 and later as a single work.

Given Stoker’s early baptism in gender-bending, it would be revealing to know what he thought of Croker’s opening woodblock illustration, showing an androgynous, even hermaphroditic fairy deity, lifted and adored in an unmistakably Christlike pose. If nothing else, it is a striking example of the fusion of Christian and pre-Christian iconography, strikingly seen in the Celtic cross, which juxtaposes the Christian cruciform and the pagan circle. Christianity figures far more prominently in Irish fairy tales than in those of continental Europe, often featuring priests, the devil, and various tests of faith. The unseen world comprised not only heaven and hell but an abundance of other supernatural dimensions as well.

In German and French compilations, the word “fairy” was used very broadly, including narratives that didn’t feature fairies at all. But in Ireland and Great Britain generally, wonder tales wove an intricate taxonomical skein of fairy-folk, a full spectrum of magical beings including pixies, pookas (possessed animals), leprechauns, banshees, devils, ogres, giants, and witches. For those delving deeply into magical belief systems, Ireland was (and is) an incomparable source for study.

A strong current in contemporary fairy tale criticism argues that oral versions of the classic stories were imbued with a rebellious proletariat spirit that was essentially hijacked and subverted by the bourgeoisie, the published versions repurposed to indoctrinate middle-class children with a materialistic work ethic and respect for established authority. The former may or may not be true, but the latter certainly would be in keeping with Charlotte Stoker’s family values. The Irish folktales she shared with her children were less purposefully crafted but often conveyed messages about miscreants and moral retribution.

Illustration of an androgynous Christ-fairy from T. Crofton-Croker’s Irish Fairy Legends (1825).

Irish tales don’t feature vampires in the sense that Bram Stoker would later depict them, but they are replete with accounts of the returning dead (often walking corpses encountered on churchyard roads) and the succubus-like Leanan-sídhe, whose draining charms prove fatal to poets who embrace her as a muse. A story from Ballinrobe, “The Hags of the Long Teeth,” features shapeshifting crones with gruesomely exaggerated overbites. Victorian folklorist Douglas Hyde notes that “long teeth are a favourite adjunct to horrible personalities” in Irish tales. Toothed or not, one well-documented and definitely blood-drinking demon of Irish folklore is the Dearg-dul. Another sanguinary spectre, repeatedly cited in modern sources but with no historical proof, is the Dreach-fhola (supposedly meaning “bad blood,” and pronounced “Drok-ola”), which more than one observer has found to be a suggestive (if not an overly obvious and even invented) homophone for “Dracula.”‡ Less problematic vampires could be found by young Bram in Perrault’s “Hop o’ My Thumb and the Seven-League Boots” with its evocative description of an ogre’s brood: “They were yet young, and were of a fair and pleasing complexion, though they devoured human flesh like their father; but they had little round grey eyes, flat noses, and long sharp teeth set wide from each other. They promised already what they would some day grow to be; for at this early age they would bite little children on purpose to suck their blood.”

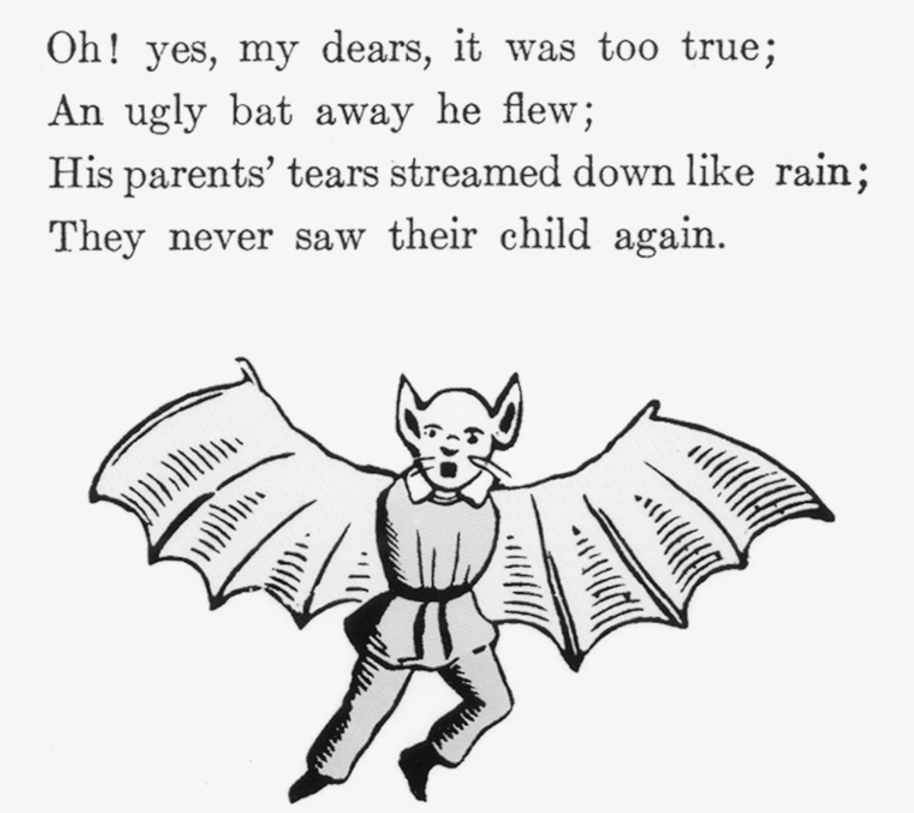

It would be indeed surprising if Stoker did not encounter Heinrich Hoffmann’s Slovenly Peter (also known as Shockheaded Peter) sometime during his childhood. First published as Struwwelpeter in Leipzig in 1845, and translated anonymously into English roughly at the time of Bram Stoker’s birth, the book was one of the best-selling children’s titles of the late nineteenth century; by the 1870s, the German edition alone had no less than a hundred printings. Hoffmann’s illustrated stories, written in rollicking verse, imparted moral instruction by dramatizing the disastrous consequences of even the smallest misbehaviors. In “The Dreadful Story of Pauline and the Matches,” a girl’s fascination with flame leads almost instantly to industrial-strength incineration. “Fidgety Philip” cannot sit still at the dinner table and ends his existence in an avalanche of sharp cutlery and broken china. The copious tears of “The Cry-Baby” loosen her eyeballs, which fall from their sockets, the optic nerves stretched like strings of taffy to the ground. One of the most famous tales, “The Story of Little Suck-a-Thumb,” scares up a spectral tailor to perform a corrective mutilation with giant scissors. Animals and animalism are everywhere, and especially apropos to a discussion of Stoker are the characters of Idle Fritz, whose escape from responsibility leads to his being devoured by a wolf, and Oswald, “the Night Wanderer,” whose repeated nocturnal ramblings transform him, permanently, into a bat: “Oh! yes, my dears it was too true; / An ugly bat away he flew; / His parents’ tears streamed down like rain; / They never saw their child again.”

The titular Slovenly Peter was a feral-looking child with wild, matted hair and curling fingernails. He had no real story of his own; Hoffman presented him as mostly an image and object lesson, an unforgettable distillation of the book’s cautionary crusade. Victorians were already obsessed with the idea of progress as both a religious and secular ideal, and Hoffmann’s supreme wild child emblemized the frightening flipside of progress: social, moral, and physical backsliding. The publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859, and the monumental controversies that followed, would fuel an ever-growing preoccupation with atavism and what would come to be known as “degeneration,” a pseudoscientific catchall term that wormed its way into every nook and cranny of late Victorian social, political, and economic discourse and is one of the most frequently discussed themes of Dracula today. Darwin himself made no case whatsoever for evolution-in-reverse, but no matter—the public’s assimilation of evolutionary theory was a process of freewheeling osmosis, fueled by the pervasive rhythms of repeated cultural metaphor, a dynamic closer to the mechanics of folklore than to the workings of science. To a large segment of the public, Darwin’s theories had the fearful, fantastical appeal of fairy tales, complete with anthropomorphic animals and magical transformations. Like Freud, Darwin shares many of the traits of a good Gothic novelist—both men alarmed the public with compelling narratives about the past’s strange ability to extend a controlling hand into the present.

The English edition of Struwwelpeter by Dr. Heinrich Hoffmann, a frightening best seller for Victorian-era children.

Stoker’s first exposure to the idea of human-into-bat transformation may well have been the story of Oswald, “the Night Wanderer,” in Struwwelpeter.

To a child in Victorian Britain, reading fairy tales was only a prelude to a much more exciting experience: the annual Christmas-season pantomime, a theatrical spectacular enjoyed by young and old alike but intended for the child in everyone. The Christmas “panto” was in no way a religious event, and didn’t utilize even secular Christmas themes, but it did coincide with the holiday calendar and usually ran well into January. Producers typically found the event to be their most profitable attraction of the year. Bram’s father was a stage aficionado and would have taken pleasure in introducing his children to the yearly extravaganza at Dublin’s Theatre Royal, an impressive venue with technical capabilities matching those of any stage in London.

Pantomimes had many antecedents in the theatre, most notably medieval morality plays and the commedia dell’arte. From the morality plays came characters and stories depicting clear conflicts between Good and Evil. Malign characters—often including a Demon King—entered from the sinister stage left, and personifications of goodness from the right. A production often credited as the first recognizable English pantomime was Harlequin Dr. Faustus, produced at Sadler’s Wells in 1723. In place of Bible stories were plots borrowed (sometimes very loosely) from classic fairy tales and The Arabian Nights. From 1855 to 1864, the years between Bram’s first steps and his enrollment at Trinity College, the pantomime offerings at the Theatre Royal on Harcourt Street included Bluebeard (with its Draculean themes of female bloodletting, forbidden rooms, and castle imprisonment), Little Bopeep, Babes in the Woods, Sleeping Beauty, King of the Castle, Jack the Giant Killer, Aladdin, Cinderella, Puss in Boots, and The House That Jack Built.

One aspect of the panto that may have especially resonated for a boy who had just spent years languishing helplessly in female clothing was the centrality of cross-dressing to the whole event. The tradition is usually attributed to the great London clown Joseph Grimaldi, who around 1800 introduced the travesty “dame” character in holiday shows at Sadler’s Wells and Drury Lane. To these rotund, farcical matrons he gave names like Queen Rondabelly and Dame Cecily Suet. One of the most enduring was (and remains) the Widow Twanky, a working-class laundress with a healthy disrespect for authority. The dames provided (and still provide) slapstick fun as the mothers of young male heroes—Jack the Giant Killer, Dick Whittington, or Aladdin—said heroes played by actresses whose tights displayed more leg than would ever have been tolerated in a straight female role. These theatrical precursors of Peter Pan (not portrayed onstage until 1904, but thereafter almost always by a woman) provided dependable and provocative eye candy for adult men attending, be they seasoned theatre devotees like Abraham Stoker or merely seasonal chaperones.

“Going to its first pantomime is the greatest event in the life of a child,” Stoker wrote. “It is to it a great awakening from a long dream. All the rest of life must have been nothing but one continued sleeping vision, and this is the real world in which the dawning imagination has sought and found a home to suit itself.”

Stoker’s initiation into the world of the theatre was liberating and life altering, coinciding with his transgender metamorphosis from a sleeping fairy princess to a real live boy. Appropriately, the highlight of each pantomime was the “transformation scene,” in which the main characters would shed their identities and assume the personae of a traditional harlequinade, accompanied by spectacular stage effects, and in time the figures Harlequin and Columbine gave way to other displays of character morphing. The “real” world Stoker discovered in the theatre was an imaginative realm of illusion; concealed, revealed, and transformed identities; strange creatures and humanized animals; a dreamy, gaslit refuge from grim realities of midcentury Dublin, and an escape from his strange affliction.

(top and bottom) Demon kings and travesty dames were central features of the Christmas pantomimes that captivated Stoker as a child.

Stoker’s childhood was filled with images from the other-land of fairy tales and pantomimes, but he never described the precise content of his reveries. However, one of his later Trinity College classmates, Alfred Perceval Graves (the father of the poet Robert Graves), gave his own striking account of the fantastic interior life of a Dublin boy in the 1850s. Graves had been introduced to Spenser’s The Faerie Queen at a very early age and recounted its “strange effects upon my imagination. Night after night I would see the most vivid processions of knights and ladies, giants and dwarfs moving afoot or on horseback from left to right across the darkened walls of my nursery.” The visions were often far from pleasant. “Often the light on the point of a spear or the jewel on a queen’s crown would suddenly expand into a hideous face” or, even worse, “a phantasmagoria of evil faces bursting out of the darkness.” Other fears were engendered by adults, in the daylight. “I was an imaginative and no doubt a troublesome child,” Graves wrote, recalling that “when I was naughty the servants threatened to hand me over to the coal man, who would carry me away in his empty sack. This was a real terror that seemed always impending, for the great, grimy fellow bending under his weight of coal often came staggering up the staircase to pitch his load with a thundering crash into the wooden bin outside the nursery door.” The idea of a fearful creature dragging a sack who whisks children away to a terrible fate is such a deeply ingrained legend in cultures throughout the world that it might well be considered an archetypal fixture of childhood nightmares. Examples are to be found in Germany, Austria, Spain, and India, as well as Central and South America and Asia. In Ireland it is mostly subsumed by a large body of lore concerning the child-stealing tricks of the fairy-folk. It is a resilient narrative, and modern, unembellished variants can still be found. As recently as 2008, in Lance Daly’s coming-of-age film Kisses, a pair of runaway Dublin preteens worry explicitly about a lurking “sack man” who, once the children are bagged, kills them by smashing the sack against a brick wall.

Whether originally related by Stoker’s parents, his nurse, or siblings, some version of the universal sack-man tale eventually inspired the following passage in Dracula—one of the most chilling scenes in all of horror fiction—in which the Count drives back his hungry wives as they prepare to make a buffet of his half-conscious guest, Jonathan Harker:

“Are we to have nothing to-night?” said one of them, with a low laugh, as she pointed to the bag which he had thrown upon the floor, and which moved as though there were some living thing within it. For answer he nodded his head. One of the women jumped forward and opened it. If my ears did not deceive me there was a gasp and a low wail, as of a half-smothered child. The women closed round, whilst I was aghast with horror, but as I looked they disappeared, and with them the dreadful bag.

It’s understandable how a Freudian folklorist might interpret the bag as a symbolic uterus, and the whole constellation of sack-man tales as a collective return-to-the-womb nightmare—a child’s frightened response to overwhelming separation anxiety and the terrors of individuation. As a near-paralytic, Stoker was bound to his mother in a deeper way than other children. It’s difficult to return to a womb one hasn’t really left. A distinctly “uterine” view of the Irish mind and imagination was put forth by Freud’s disciple Ernest Jones in his 1923 book Essays in Applied Psycho-Analysis. Jones described the Irish mind as a problematic case, owing to the island country’s unique “geographic insularity” unconsciously associated with the idea of uterine confinement. According to Jones, “All aspects of the idea of an island Paradise are intimately connected with womb phantasies,” a sentiment indirectly—if endlessly—echoed in countless literary and popular descriptions of the Irish as childlike and escapist, whether by means of poetry, storytelling, and fairy legends or the alternate, liquid womb of alcohol. In another book, especially interesting apropos of Stoker’s sickly dependence on his mother, Jones maintained that the incest complex fueled Eastern European vampire lore.§

Charlotte Stoker would have had the same difficulty understanding her son’s illness as modern readers have deciphering his psychology. With no other remedies at hand, many mothers like Charlotte turned to readily available drugs. The possibility that Bram’s paralysis was induced by a drug like opium is not as outlandish as it might at first sound. Charlotte’s true-believer experience with whiskey-based nostrums during the cholera plague would have predisposed her for stronger medicine during the far more cataclysmic famine. By the mid-nineteenth century, the administration of laudanum—a mixture of alcohol and opium—to children, even infants, as a cure-all and prevent-all, was frighteningly common. The homespun concoctions of the Thornley family in 1832 had by the 1840s been replaced by wildly popular commercial laudanum preparations such as “Godfrey’s Cordial,” “Infant’s Preservative,” and “Mrs. Wilkinson’s Soothing Syrup.” Some advertisements even carried reassuring endorsements from Queen Victoria.