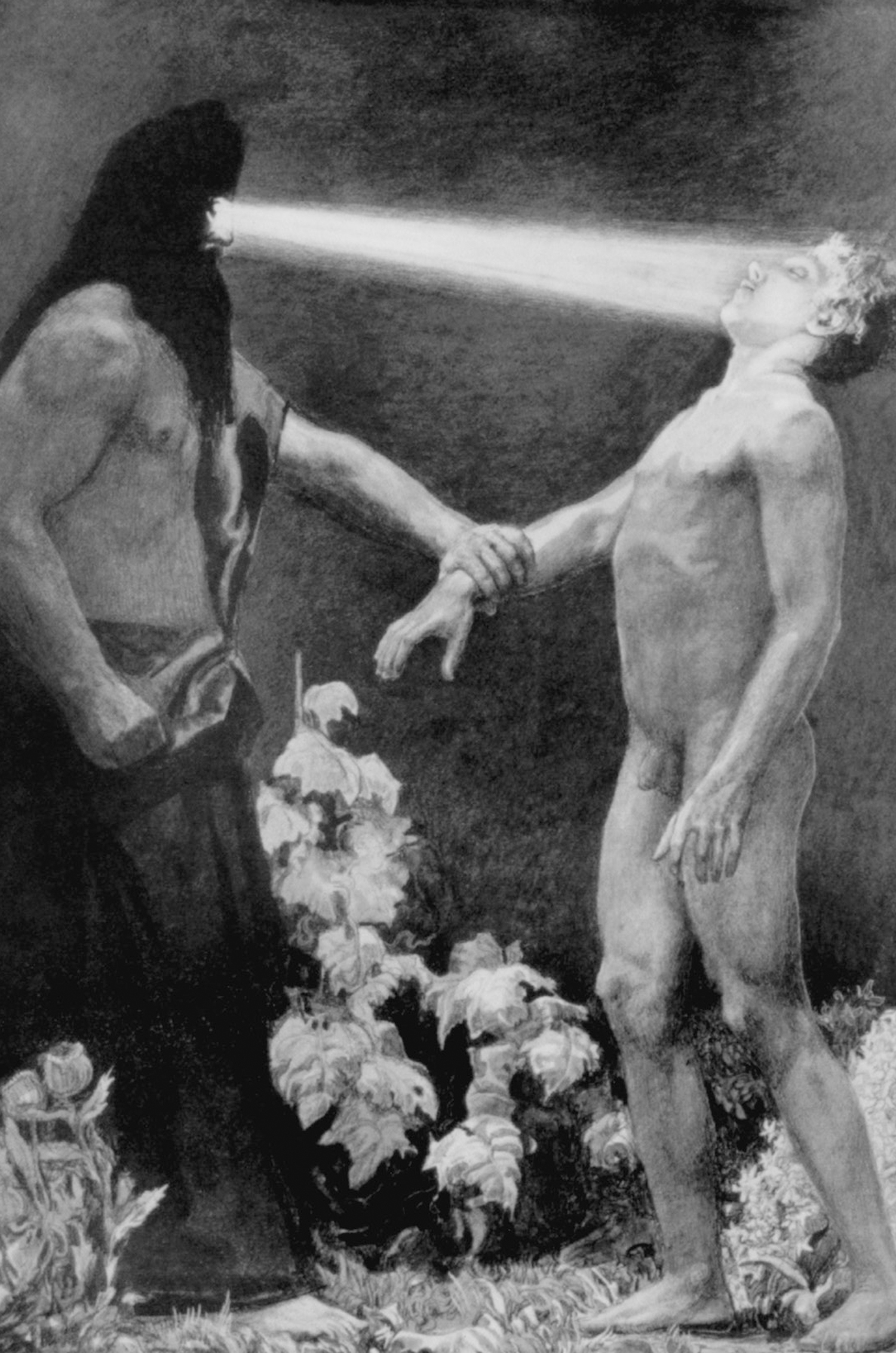

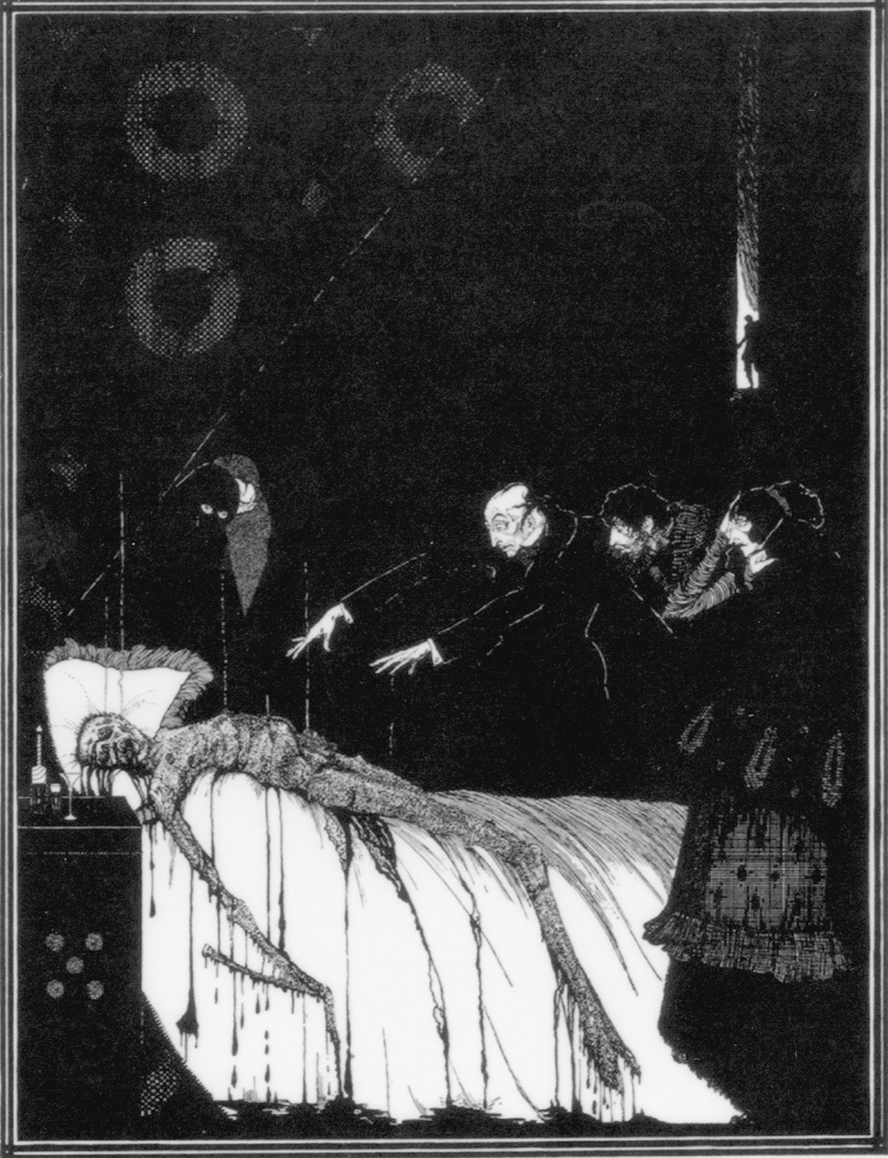

“Hypnotism” by Sascha Schneider (1904). During his student years at Trinity College, Stoker was drawn to pseudoscientific theories of mind, body, and eros.

“Hypnotism” by Sascha Schneider (1904). During his student years at Trinity College, Stoker was drawn to pseudoscientific theories of mind, body, and eros.

HE WANTED TO MEET IN THE REAL WORLD THE UNSUBSTANTIAL IMAGE WHICH HIS SOUL SO CONSTANTLY BEHELD.

— James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Despite Stoker’s early imaginative leanings, his parents had more practical plans, and his early adolescence was devoted to intense preparation for the daunting entrance examination at Trinity College, Dublin. Trinity was, and remains, the sole constituent college of the University of Dublin, the youngest of the seven Ancient Universities of Britain (the oldest being Oxford and Cambridge).* The revered institution was founded in 1591 by Queen Elizabeth as “the College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, near Dublin.” Trinity was a bastion of the Protestant Ascendancy, and Stoker’s parents—especially his mother—were determined that their sons rise in the world.

Admission to Trinity in 1864 required passing a competitive entrance examination for which almost no sixteen-year-old today would be even remotely prepared. According to the Dublin University Calendar, “At the Entrance Examination, Candidates will be examined in Latin and English Composition; Arithmetic; Algebra (the first four rules, and Fractions); English History; Modern Geography, and any two Greek and two Latin books, of their own selection” from a list including, in Greek, such works as the Gospels of St. Luke and St. John, Homer’s Iliad, Euripides’s Orestes, Sophocles’s Antigone, Plato’s Apologia Socratis, Xenophon’s Anabasis, and, in Latin, Virgil’s Aeneid, as well as the Odes, Satires, and Epistles of Horace. Stoker’s selections are not known, but given his already strong interest in theatre and wonder tales, it would be surprising if he hadn’t favored the epics and dramas.

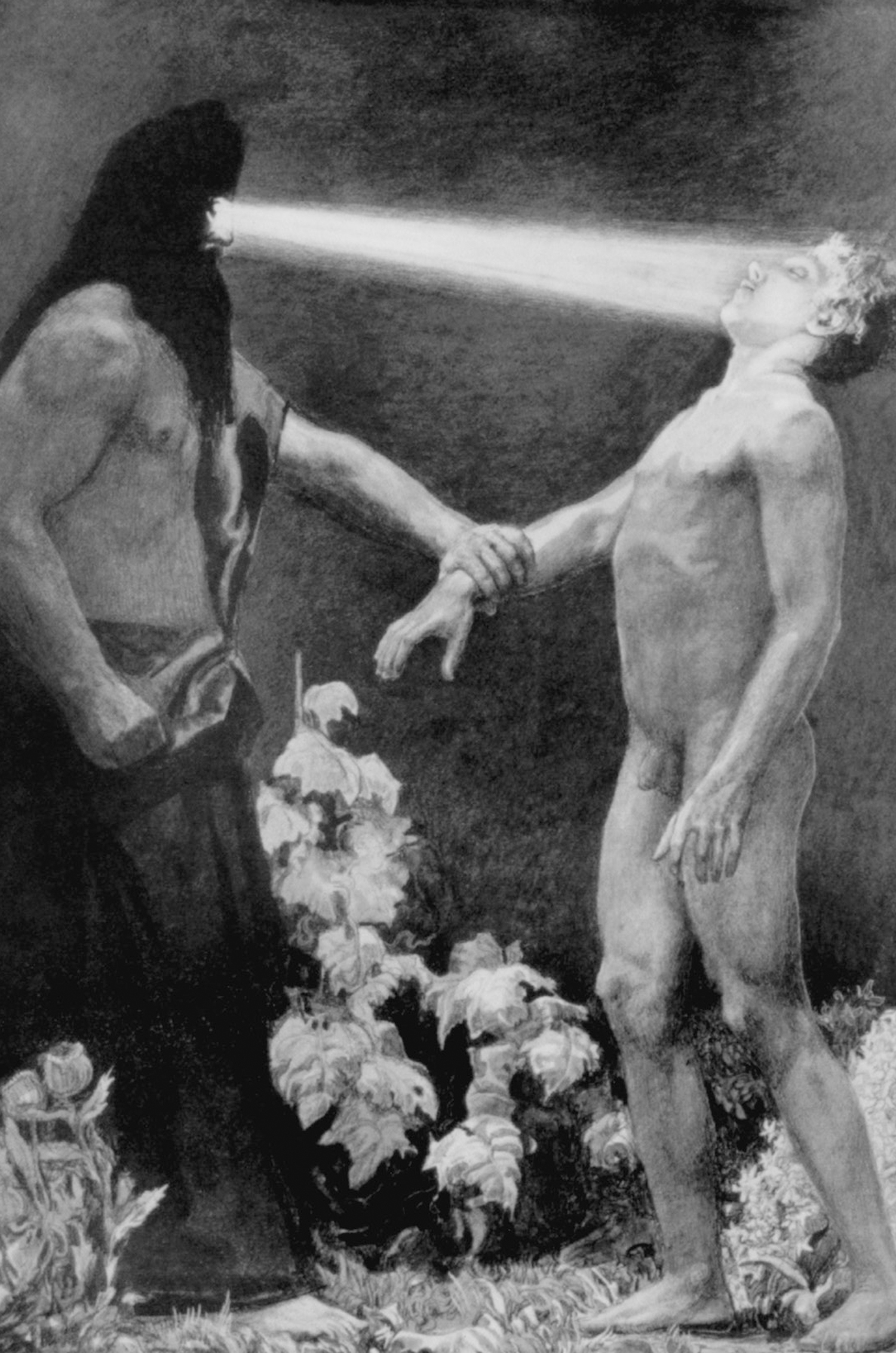

Trinity College Dublin entrance examination room as it appeared in the late nineteenth century.

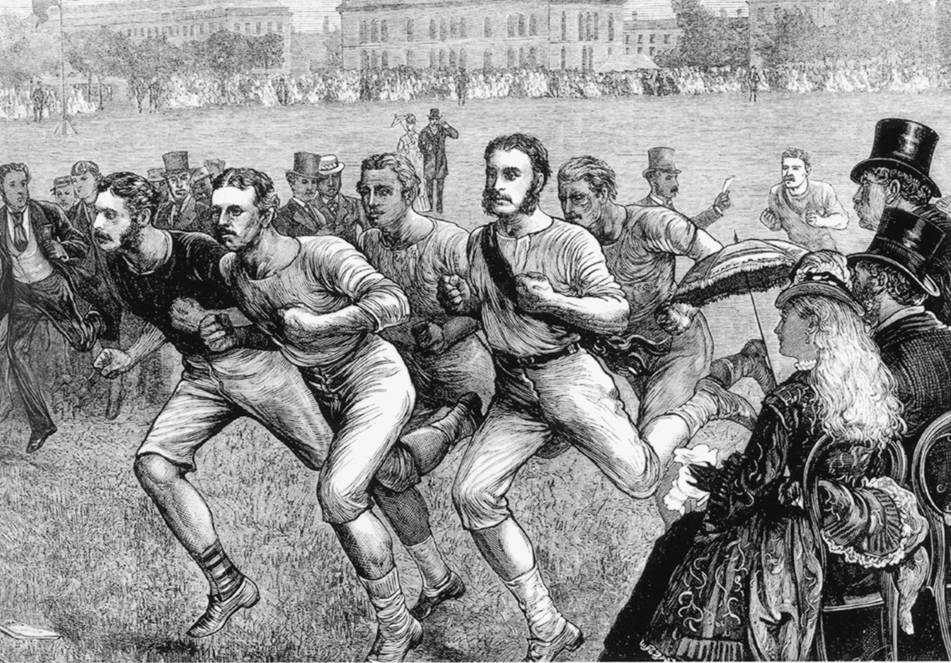

He identified his only teacher prior to Trinity College as the Reverend Dr. William Woods, who ran a day school on Rutland Square (now Parnell Square) and was associated with the Bective House College. Originally the Bective House Seminary for Young Gentlemen, the preparatory academy was long favored by families with an eye on Trinity College for their sons. Woods himself would later buy the school, but in the mid-1850s he took students privately. Rutland Square itself was ideally located for the Stokers; the family had moved yet again, to 17 Buckingham Street, Summerhill, only blocks away. Thornley had previously been sent to Wymondham Grammar, a well-regarded boarding school in England; that expense may well have necessitated a less costly option for Bram, and an independent tutor was far less expensive than the faculty and resources of a full school. One special feature of Rutland Square, on the site presently occupied by the Garden of Remembrance (commemorating the 1916 Easter Rising), was a large playing field, easily accessible to the students. Here they eagerly sharpened their skills at rugby football, a game then rapidly gaining popularity in Britain, especially among students and enlisted men. Stoker would later be an enthusiastic player at Trinity.

What did Reverend Woods make of the odd boy presented to him around the age of eleven? Stoker had possessed normal motor skills for only about three years. Yet, since he had already been presented with his own inscribed Bible, his basic reading skills were presumably in place, giving credence to Charlotte’s possible role as homeschooler. And by the age of twelve his verbal gifts, mathematical aptitude, and generally prodigious capacity for assimilating and organizing information would have been more than evident.

But on a purely developmental level he was unusual indeed. Illness had robbed him of many basic formative experiences and socialization, and now, with only thirty-six months of anything approaching normal volition and mobility, he was about to become a prototypical “little adult,” faced with daunting responsibilities. It was the beginning of a life pattern of punishing overwork and an obsessive drive to overachievement.

At the cusp of adolescence, Stoker was lucky to be a member of the middle class, however tentative and precarious. His counterparts in the artisan and working classes faced brutal conditions in an age that placed almost no regulations on child labor. The mills and factories exploited children as a grueling matter of course. Perhaps the most horrible occupations for young children were those of “apprentice” chimney sweeps, who began work as early as the age of three, whose skills were useless after they had grown too big, and who were often permanently incapacitated by skeletal deformities and respiratory ailments brought on by their toil.

What Stoker had in common with these unfortunate youngsters was a harsh Protestant work ethic (for poor Catholics, less a value than a cruelly imposed condition of political and economic life). Everyone had to work and strive. Survival of the family often depended upon all members pulling their own weight, and more. In the case of the Stokers, the education of their sons was more about long-range stability than immediate survival, although in the end even several successfully educated sons would never provide true economic security for their aging parents.

Bram passed the Trinity entrance examination but placed only fortieth in a class of fifty-one. Ranking just under the twentieth percentile—less than half the average score—did not bode well, at least under Charlotte’s exacting standards. One might have expected an imaginative boy who was “already a bit of a scribbler” to pursue a moderatorship (an honors degree) in literature at college, but in his distracted dreaminess he may not have had any particular goals except those his parents, who were paying the bills, dictated. For the Michaelmas term in the autumn of 1864 he was enrolled in the no-nonsense, dry-as-dust Ordinary Course of Studies, emphasizing Greek, Latin, mathematics, and physics. Not until the third year, as Junior Sophisters, were students scheduled to have cursory exposure to classical Roman drama, and even then nothing beyond Euripides’s Medea and Terence’s Adelphi. Nowhere in his assigned reading could Stoker expect to encounter such stirring and essential classics as Euripides’s The Oresteia or Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex, the comedies of Aristophanes, the basic dramatic and literary concepts of Aristotle’s Poetics, nor anything whatsoever of Shakespeare or English literature. The young man who later spent much of his career immersed in the Shakespearean Sturm und Dräng of Sir Henry Irving would discover the Bard of Avon on his own.

Tuition, exclusive of room and board, was charged by social and economic rank. Noblemen paid £60 upon entrance and another £33 at half year; Fellow Commoners £30/£16; Pensioners £15/£8; and Sizars £5/£0. The Stoker family qualified as Pensioners. Bram lived at home during his studies and avoided the costs of boarding.

Religious observance was a strict daily requirement (“Roman Catholics† and Dissidents excluded”), with students expected to attend morning and evening prayer services. According to the Dublin University Calendar for 1865, “On Sundays and holidays, and also at Evening Prayer on Saturdays, and the eves of such holidays as have vigils, all students must wear surplices, with the hoods belonging to their degrees, if they be Graduates. But on Ash-Wednesday and Good Friday gowns are worn.” The rules were ritualistically enforced, as the Calendar made clear: “Correction.—at half-past eight o’clock on Saturday evenings the junior Dean attends in the hall, and reads out the names of all students who have been punished for neglect of duties or other offenses during the week. It is in the interest of those who can excuse themselves to be present, and if the excuses are extended to the Dean, the fines are taken off.”

Since Stoker had been raised in an observant Protestant home, including daily prayers and a mother who maintained a formal list of the “Rules for Domestic Happiness” according to Christian principles, religious obligations wouldn’t have been particularly burdensome. It is interesting, however, that his later first-person, nonfiction writings contain no mention of his personal religious convictions or practices. But repeated references to God, prayers, and praying would erupt in nearly all the twenty-seven chapters of Dracula.

“Every day let your eyes be fixed on God through the Lord Jesus Christ,” Charlotte’s first rule reads, “that by the influence of his Holy Spirit you may receive your mercies as coming from him, and that you may use them to his glory.” Although it is not clear whether she wrote these commandments herself or, far more likely, transcribed them from another source, “domestic” in Charlotte’s usage means “marital,” and the rules all speak to the relations between husband and wife. They outline an approach to life that is strikingly at odds with family descriptions of Charlotte’s willful, dominating personality. “Whenever you perceive a languor in your affections, suspect yourself,” “Always conciliate,” and “Forbearance is the trial and grace of this life” are not sentiments that comport well with the legend of a woman who relished cracking the whip. For all her supposed disappointment at Abraham’s lack of career drive, she reminded herself on paper, at least, “Forget not that one of you must die first; one of you must feel the pang and charm of separation. A thousand little errors may then wound the survivor’s heart.” An element of humility and even contrition runs through Charlotte’s “Rules,” although nowhere in her papers is there evidence of any regret for the ax murder she committed in Sligo at the age of twelve. Surely the nameless cholera victim whose hand she severed bled out and died. A doomed, disease-maddened mob breaking into the family’s house would hardly have carried tourniquets, much less the necessary tools to cauterize a spurting stump. Is it possible that her fervent rules, with the self-exhortation to “Pray constantly, you need much prayer, prayer will engage God on your behalf,” helped her address conflicts outside her marriage as well?

Like most young people in their inaugural college terms, Stoker was exposed to a more expansive number of ideas, religious and otherwise, than at any time in his sixteen years on earth. For nearly half his natural life before freshman matriculation, his universe had been constricted to a sickroom and his mother’s hovering apprehension. At Trinity there were Dissenters and Catholics, politics both worldly and academic, and generally more things in heaven and on earth than his family’s domesticated, Protestant, nose-to-the-grindstone virtues had ever made room for. With clockwork regularity, he had moved with his always-struggling clan every few years, never developing a strong sense of place or permanence, but now he was part of a university and traditions that had held their own for 175 years.

His assigned tutor was Dr. George Ferdinand Shaw. In the first year, reading for Junior Freshmen included, in Greek, the three Olynthiac Orations of Demosthenes and, in Latin, Cicero’s Milo. Euclid’s mathematics, including arithmetic, algebra, and trigonometry, filled out a somewhat dreary curriculum. His second year, from November 1865 through the spring of 1866, offered considerably more mental stimulation, with the requisite courses in logic (via John Locke), Plato’s Socratic Dialogues, more Cicero, and revisitation of Virgil and Homer (the Aeneid, as well as the Iliad and the Odyssey), the latter two authors almost certainly having been part of Reverend Woods’s curriculum.

But the most interesting second-year text for Stoker was Victor Cousin’s Elements of Psychology, a work not much referenced today but seminal in its time. Its lasting impact on Stoker is evidenced by the mention of Cousin more than four decades later in the introduction to his penultimate book, Famous Impostors. Cousin was a French philosopher and educator who offered a strong rebuke to creeping materialism, arguing for the concurrent existence of an immaterial, immortal soul and an innate “natural intelligence” independent of the body and sensations.

Cousin’s philosophical eclecticism bridged many of the divisions between science and religion that would intensify throughout the nineteenth century, especially after the publication of Darwin’s The Descent of Man in 1871. Cousin’s view of God was expansive: “He is one and several, eternity and time, space and number, essence and life, individuality and totality, beginning, middle, and end; at the top of the ladder of existence and at the humblest round; infinite and finite both together; a trinity, in fine, being at once God, nature, and humanity.” Cousin’s scriptural cadences were rhetorically compelling, but some detractors accused him of promulgating pantheism rather than Christianity. The idea of a God who didn’t sit remotely on a celestial throne but instead permeated everything made Cousin attractive to the American transcendentalists, especially Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In the lengthy introduction to Elements of Psychology by its English translator, Caleb S. Henry, Stoker became acquainted with the concept of “sensualism,” also known as “sensationism” or “sensationalism.” In his critique of eighteenth-century thought, Cousin rebuked as dehumanizing the notion of all reality and meaning being reduced to sensory stimulation: “Sensualism was the reigning doctrine,” wrote Henry. “All knowledge and truth were held to be derived from Experience; and the domain of Experience was limited exclusively to Sensation. The influence of this doctrine spread to every development of intellectual activity—art, morals, politics, and religion, no less than the physical and economical sciences.” This “new faith” managed to supersede “the forgotten or ill-taught doctrines of Christianity. It was in all books, in all conversations; and, as a decisive proof of its conquest and credit, passed into instruction.” The resulting degeneration of intellectual and educational standards, Cousin suggested, had led directly to the chaos of the French Revolution.

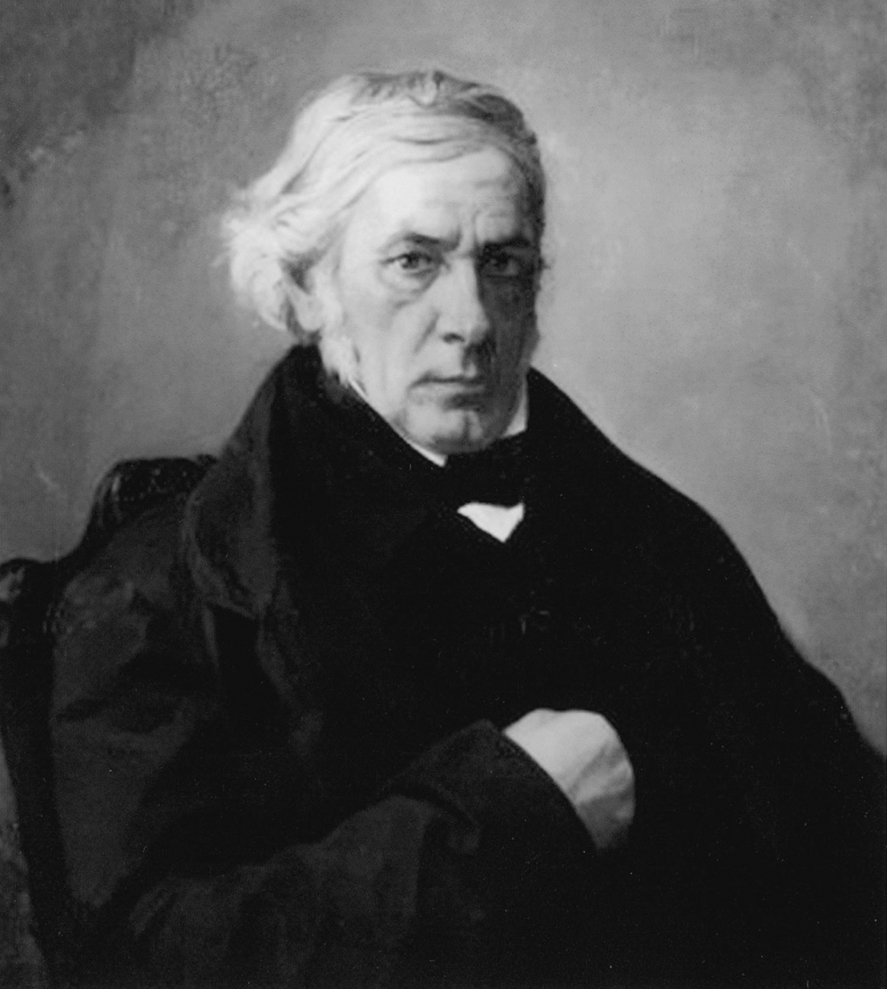

Stoker’s second-year reading at Trinity College included the French intellectual and educator Victor Cousin, whose philosophical psychology attempted to bridge a widening gap between materialism and spirituality.

Although Cousin considered the reign of philosophical sensualism/sensationism at an end, the descended, secondhand idea of literary sensationalism was by the early 1860s coloring the reception of wildly popular novels like Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White (1859–60) and Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1861–62). Stoker knew both books well, and each dealt with female insanity, asylums, and sociopathic crime. Sensation novels had successfully appropriated the popular-reading niche formerly occupied by writers like Ann Radcliffe and Matthew Lewis. Unlike the Gothic novel, sensation fiction took place in the very modern present, the past figuratively represented by atavistic criminality instead of ancient, moldering castles. A psychological primitivism replaced histrionic history. Dracula, of course, would draw upon both traditions, pitting modern characters against medieval menace in a single, compulsively readable narrative.

Critics of sensation novels worried that mere descriptions of extreme emotions and actions could be as mentally overstimulating as the actual experiences themselves, with potentially dehumanizing effects. In a nutshell, the perceived harm of such entertainment was the fear of literally becoming what you consumed or beheld—a very primitive response, but one endlessly echoed even today by censors of all stripes. It was a rather crude reduction of the concerns of Cousin—who at least believed in the power of God-given moral knowledge—but Victorians who felt religion slipping away were inclined to distrust encroaching materiality as a simple matter of caution.

Critiques and condemnations of sensationalism constituted a kind of pseudoscience closely aligned to the nineteenth-century cults of mesmerism, phrenology, and spiritualism. All made grandiose claims about the connections between the material world and the besieged citadel of the self or soul, increasingly and alarmingly viewed by conventional science as a mere by-product of the brain. Phrenology (the purported revelation of personality through cranial analysis) amounted to a kind of physical mind reading or divination. The theatrical rituals and protocols of séances and mesmerism employed faux-methodologies that seemed to offer a vernacular competition to the scientific method and access to ethereal realms. Pseudoscience reassured the anxious that there was still an unseen yet accessible transcendent reality, that the afterlife did exist, that the human mind was something greater than the physical brain. Pseudoscientific and supernatural inquiry intrigued Stoker all his life. And, of course, crises of religious faith and existential riddles of the “who am I, what am I” variety, and the seeking of alternatives to conventional religion, are common among college students and young adults, especially those who have lived sheltered lives.

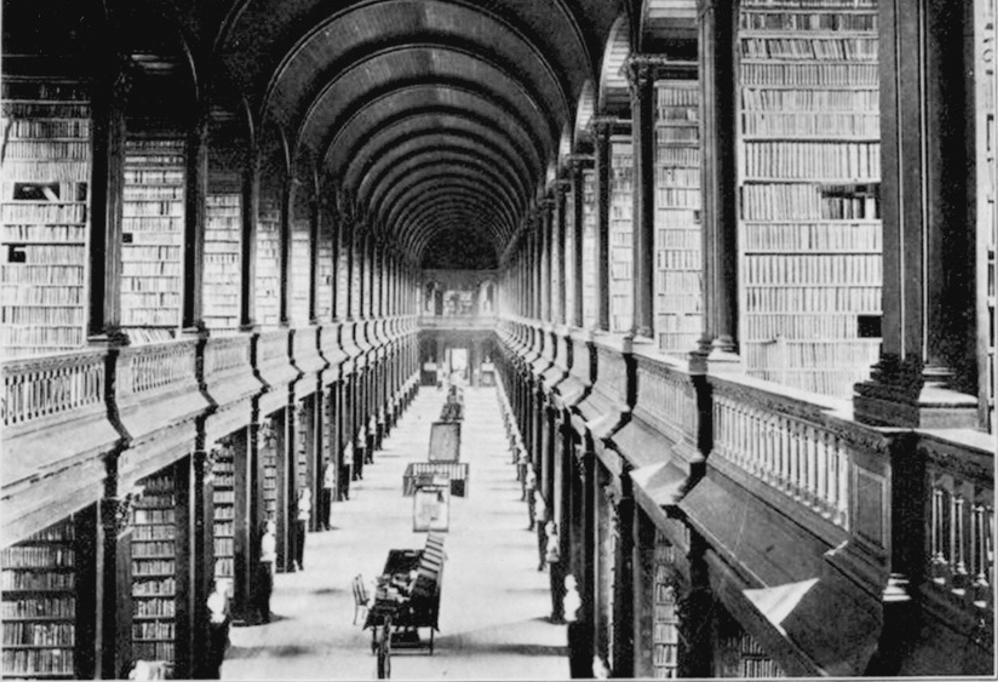

As a child, Stoker practically inhabited a cocoon. But as a college student, he had privileged access to one of the great repositories of knowledge in Great Britain—the Trinity College Library—and it must have been a revelation akin to his sudden ability to walk. Only four years before his matriculation, the ceiling of the library’s stately, nearly two-hundred-foot Long Room had been raised to its present, barrel-vaulted height, the first level lined with white marble busts of the greatest thinkers and writers in history. The Long Room today is one of the most iconic and atmospheric scholarly spaces in the world. The library was one of the designated copyright depositories for books published throughout Great Britain; however, it was exempted from accepting acquisitions automatically and chose very selectively. While the institution’s long-standing refusal to catalog the complete poems of Walt Whitman (a writer soon to put a mesmeric spell upon Stoker) was clearly censorious, it also more generally reflected a bibliographic blind spot for whole swaths of nineteenth-century writing, even titles now considered canonical. The library’s printed catalog for 1872 reveals that Stoker would have looked elsewhere to discover Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, for instance (though her travel writings and edited volumes of her husband’s writings had made the grade), or anything of Poe except his poetry. John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” (1818) was there, and Gothic classics like Horace Walpole’s seminal The Castle of Otranto were likewise present, while Ann Radcliffe and Matthew “Monk” Lewis were completely ignored. Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights was also conspicuous by its absence. Sensation novels were available in a wafer-thin sampling including Lady Audley’s Secret and The Woman in White.

In poetry, Baudelaire’s notorious Les fleurs de mal (1857) with its “Metamorphoses of the Vampire” seems to have been repellant enough to be repelled itself, though Henry Thomas Liddell’s “The Vampire Bride” (1833) had accepted its invitation to cross the Trinity threshold:

He lay like a corse ’neath the Demon’s force,

And she wrapp’d him in a shround;

And she fixed her teeth his heart beneath,

And she drank of the warm life-blood!

Several of the nonfiction books Stoker consulted for Dracula were available to him as a Trinity undergraduate, though it is an open question whether his fascination for the paranormal, already keen, would have led to curious perusal. Augustin Calmet’s The Phantom World (1850), including an important historical treatise on vampires, was there, along with Sabine Baring-Gould’s The Book of Were-wolves (1865) and Curious Myths of the Middle Ages (1866). Two other books on the occult, Joseph Taylor’s Apparitions (1815) and Fiends, Ghosts and Sprites by John Netten Radcliffe (1854; author no relation to Ann Radcliffe), also escaped embargo by Trinity’s gatekeepers.

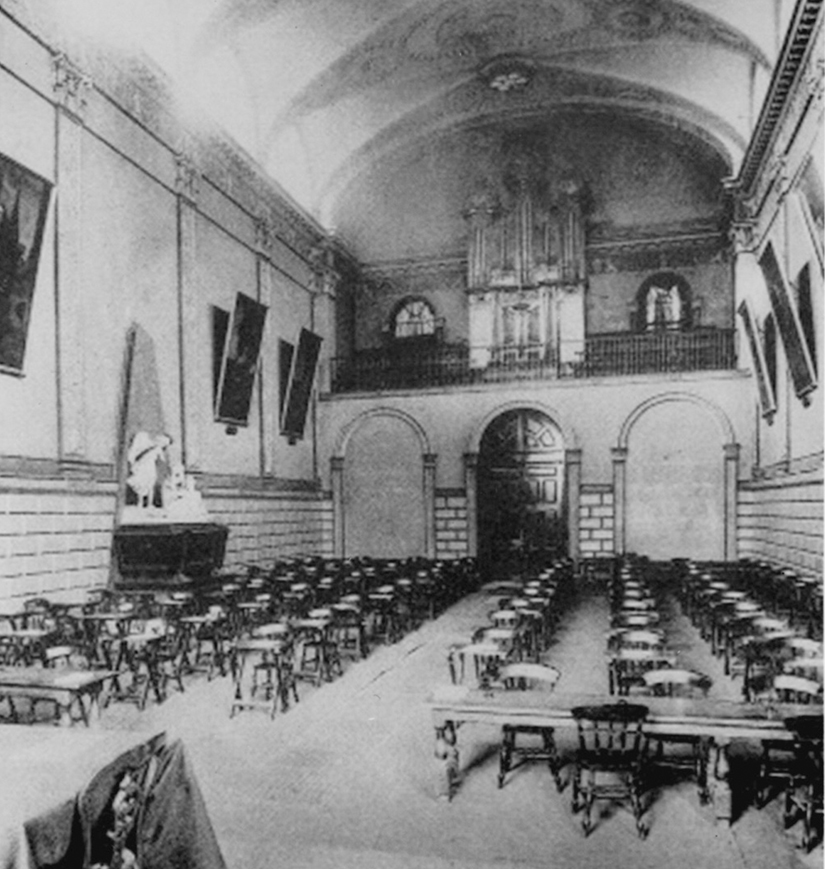

The Long Room at Trinity College Dublin Library as it appeared in the 1860s.

Elsewhere in the library were back numbers of the Dublin University Magazine, in which Stoker could have found solemnly credulous essays on mesmerism as a bridge between life and death, as well as the ghostly short stories and serialized novels of J. (for Joseph) Sheridan Le Fanu, one of Dublin’s literary luminaries, if not its most prominent contemporary star. Great-nephew of the Restoration playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and Trinity educated himself, Le Fanu had purchased the Dublin University Magazine in 1861, the better to showcase his own work. An Irishman of Huguenot extraction, Le Fanu was greatly influenced by the eighteenth-century mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, whose philosophy embraced extradimensional angels, demons, and even extraterrestrial entities.

Stoker entered Trinity College just as the Dublin University Magazine finished its serialization of Le Fanu’s sinister novel Uncle Silas, which was then immediately published in book form. Le Fanu added a defensive introductory note, arguing that his novel—a story of an orphan’s peril at the hands of her cadaverous guardian and her equally unpleasant governess—did not deserve the label of “sensation” fiction, despite its being exactly that. Whether Stoker read Uncle Silas immediately or later, it had a strong effect on him. A few decades later, he would specifically recommend the book to his son—the only literary endorsement ever reported by his family. The book was a teeming storehouse of macabre metaphor and description, which he would add to the wealth of otherworldly words and images he began mentally amassing in childhood.

In particular, Le Fanu’s description of Silas Ruthyn would eventually merge seamlessly in Stoker’s mind with that of Ambrosio, and the licentious Capuchin of The Monk (a hawkish profile, conjoined eyebrows, and a flamelike, penetrating gaze) with Silas’s own unearthly presence: “a face like marble, with a fearful monumental look,” “dazzlingly pale” and “bloodless,” like a “ghost” with “hollow, fiery, awful eyes!” Silas’s voice is “preternaturally soft,” his aspect “spectral,” and he dresses in “necromantic black.”

Although Le Fanu stopped short of identifying Silas as one of the walking dead (the novel was a chilling thriller, but not one of his ghost stories), the vampiric evocations were made complete in his villain’s surname, Ruthyn — a barely altered version of Ruthven, the eponymous character of Polidori’s “The Vampyre.” Polidori’s story was the first, and most imitated, vampire narrative in English, having inspired several popular stage adaptations in England and France, as well as a German opera. Later, Le Fanu, and Stoker especially, would give Polidori a memorable run for his blood money.

In his memoir Seventy Years of Irish Life, Le Fanu’s brother, William, gives an illuminating anecdote about Joseph’s youthful imagination: “At an early age my brother gave promise of the powers which he afterwards attained. When between five and six years old a favourite amusement of his was to draw little pictures, and under each he would print some moral which the drawing was meant to illustrate.” One William recalled especially and regarded as “a masterpiece of art, conveying a solemn warning. A balloon was high in the air; the two aeronauts had fallen from the boat, and were tumbling headlong to the ground; underneath was printed in fine bold Roman letters, ‘See the effects of trying to go to heaven.’ ”

Elsewhere in his book, William gives an interesting account of his own experiments in the “electro-biology” of hypnotism. “I have made a lady, who had the greatest horror of rats, imagine that my pocket-handkerchief, which I had rolled up in my hand, was one, and when she rushed away terrified, I made her think she was a cat, and she at once began to mew, seized the pocket-handkerchief in her teeth, and shook it,” he boasted. “I have made people believe they were hens, judges, legs of mutton, generals, frogs, and famous men; and this in rapid succession. Indeed so complete was their obedience, that I have again and again refused, when asked, to suggest to them that they were dead.”

Having a keen interest in mesmerism, the younger Le Fanu could not have been unaware of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” (1845), a sensational cautionary tale about the dangers of mixing death and hypnosis, in which prolonged suspended animation reduces the title character, upon waking, to an alarming condition. Poe’s breathless narrator recounts, “As I rapidly made the mesmeric passes, amid ejaculations of ‘Dead! dead!’ absolutely bursting from the tongue and not the lips of the sufferer, his whole frame at once—within the space of a single minute or even less, shrunk—crumbled—absolutely rotted away beneath my hands. Upon the bed, before that whole company, there lay a nearly liquid mass of loathsome—of detestable putridity.”

The story was published in England in pamphlet form the following year as “‘In Articulo Mortis.’ An Astounding and Horrifying Narrative Shewing the Extraordinary Power of Mesmerism in Arresting the Progress of Death.” Since “Mr. Edgar A. Poe, Esq., of New York” was a known working journalist, and the piece was not labeled as one of his fictions, many took the story as fact. Poe’s creepy spin on the dangers of mesmerism was additionally startling because it threw cold water on the pseudoscientific claims about trance communication with the dead, a major feature of the spiritualism movement rapidly growing in both America and Europe. Death was death, M. Valdemar’s story seemed to say, and in the end we all went to dust—or its loathsome liquid equivalent.

A growing interest in extracurricular esoterica may have caused a precipitous drop in Stoker’s grades toward the end of his second year. His interest in the fantastic and occult certainly took him to a cabinet of curiosities just across the street from the Trinity campus that advertised regularly in the Dublin Evening Mail.

MAGIC PHANTASMAGORIA AND DISSOLVING VISION LANTERNS

A large collection of Dioramic Effects, Astonishing Mechanical Contrivances and Illusions, including Ghosts, Acrobats, Magic Visions, and other novelties.

Mr. E. Solomons, Optician, Mathematical and Philosophical Instrument Maker (Established in Dublin 50 years) 19 Nassau Street

But it was Stoker’s college career that was becoming a real “dissolving vision.” Thirty years later, he would claim that he “graduated with honours in pure mathematics.” This wasn’t a small distortion of the truth—it was simply a lie, completely unsubstantiated by the records. The claim was all the worse in light of criticism that, in poor comparison to other British universities, Trinity’s “average number of mathematical honourees has been a fraction over three. And this in a mathematical university!” In Stoker’s year of graduation, only two such honors were bestowed.

Irish illustrator Harry Clarke’s nightmarish rendering of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar.”

Even in today’s world, such a misrepresentation of one’s college record might have serious professional repercussions. Perhaps making the claim so late in his life (1906, six years before his death) did not seem to him a substantial risk. It is also possible that decades of theatrical press-agenting made routine puffery such a second-nature reflex that he came to believe his own publicity. Granted, he had some reason, if not an excuse, to fudge the record. Stoker didn’t merely fail to graduate cum laude. He was an uninspired and mediocre student; his low entrance exam scores had been prescient. One can only imagine his mother’s disappointment. Stoker fell painfully short of Charlotte’s expectations, coming nowhere near the “second out of a thousand” status she would have disdained anyway. As the narrator of one of his later novels, The Mystery of the Sea (1902), would explain, “At school I was, though secretly ambitious, dull as to results.” In college he seems to have been positively bored.

He achieved only middling examination grades for two years, after which his attendance became erratic and finally nonexistent. The academic archives themselves are intact; it is only Stoker’s records that are missing. No doubt with his family’s encouragement—or outright insistence—and through his father’s connections, he applied for and received a civil service post at Dublin Castle in 1866. It was a full-time, six-day-a-week position, so it’s not surprising that his academic status was “downgraded” in 1867. At this point, his academic career appears to crash completely.

But after a year’s absence, he would return—as an utterly changed person who would complete his education in a thoroughly unorthodox way.

First and foremost, all vestiges of the sickly child who couldn’t control his limbs were gone. Growth spurts in very late adolescence are not unknown, and in Stoker’s case might well explain the sudden, keen interest in athletics two years into his college career. There is no indication whatsoever that he participated, or had any interest, in sports before 1866, when his involvement in physical culture became both time-consuming and obsessive for the next four years. As he would observe of himself fictionally in The Mystery of the Sea, at college “my big body and athletic powers gave me a certain position in which I had to overcome my natural shyness.”

With no prior challenges or visibility, he suddenly scored a victory in the Dublin University Foot Races of 1866. For the university’s general sports competition on May 22 and 23, 1867, Stoker won the champion cup, an engraved silver tankard, one of many still proudly owned by his descendants. The next year saw him win the seven-mile walking race. He demonstrated impressive expertise on the trapeze, in vaulting, and in rowing. In rugby, he played on both the Trinity and the Civil Service teams.

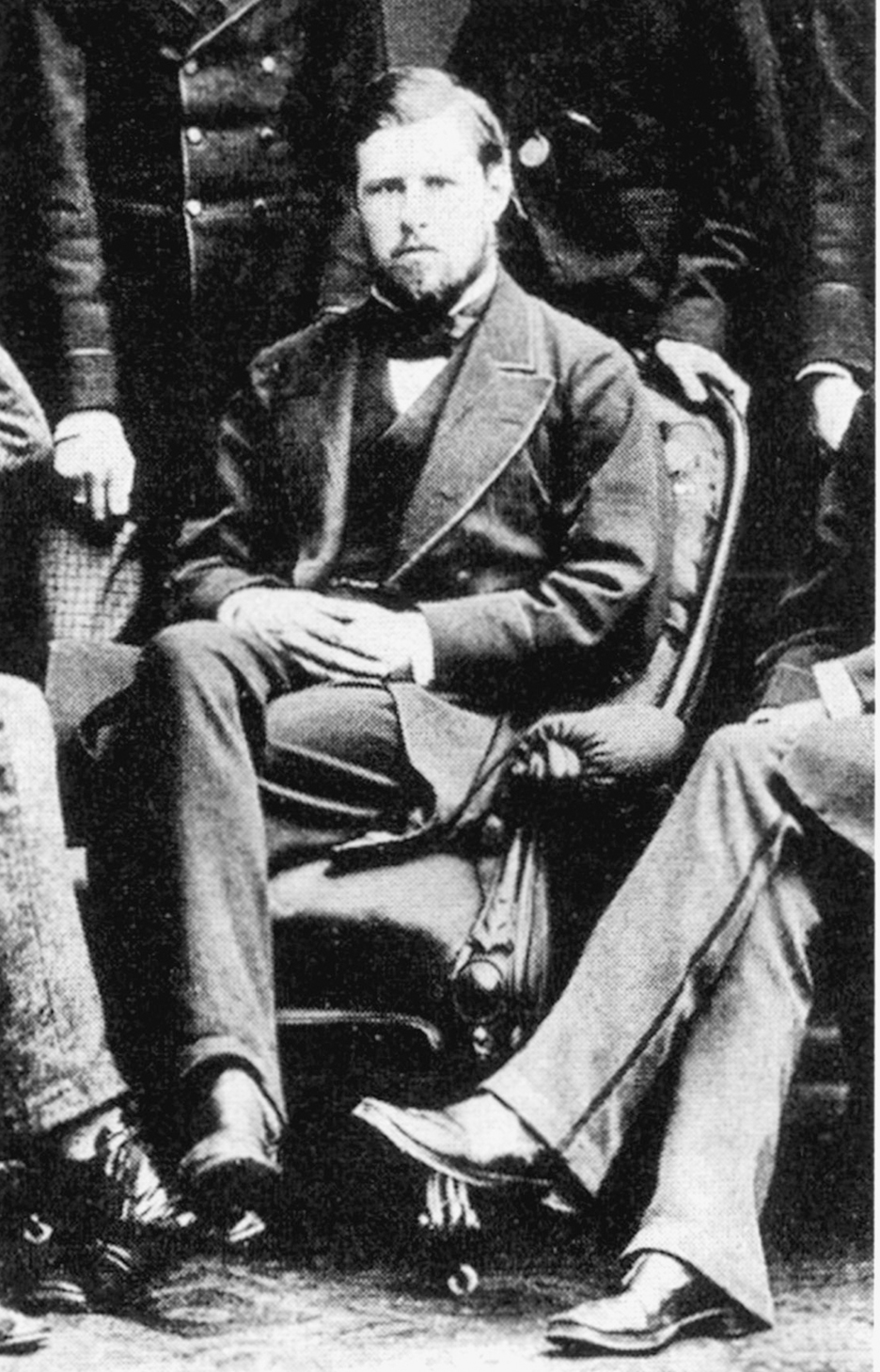

While academic records of his last four years are nil, there is ample documentation of ambitious extracurricular activities that extended far beyond sports. He was the only Trinity man to have served as both auditor of the College Historical Society and president of the Philosophical Society, the top positions attainable. The Hist and the Phil (as they were informally known) were Trinity’s extracurricular organizations dedicated to discussion and debate. In addition to undergraduates, both groups included as members prominent and influential figures such as Sir William Wilde (father of Oscar, and a distinguished eye surgeon, statistician, and ethnographer), John Pentland Mahaffy, Trinity’s leading classicist and later its provost, and Edward Dowden, an academic wunderkind who would become the college’s first professor of English Literature and a special mentor to Stoker. Given his interests, it is not surprising that Stoker chose “Sensationalism; in Fiction and Society” for the title of a paper he delivered at the Phil in the spring of 1868. Among the literary topics debated at the Hist was the proposal “That the Novels of the Nineteenth Century are more Immoral in their Tendency than those of the Eighteenth.” Stoker opposed the motion. Intriguing as these and many other topics are, Stoker’s paper on sensationalism has not survived, and the substance of the debate argument was not recorded.

As both an undergraduate and graduate, Stoker excelled athletically at Trinity College Dublin competitions, depicted here in the Illustrated London News, 1874.

Both societies were excellent places for Stoker to network and curry favor with some of the most powerful men in Dublin. He may have needed to. With all his time devoted to his job at Dublin Castle, athletics, and the Hist and the Phil, he completely neglected formal academic study. Yet, on Shrove Tuesday in April 1870, he was—somehow—conferred his baccalaureate.

How on earth was it possible for Stoker to circumvent a normal course of lectures and examinations and nonetheless receive a degree? The Dublin University Calendar makes no mention of the possibility of such an unusual arrangement. All histories of Trinity College in the nineteenth century emphasize the central importance of examinations. But at Trinity, a certain amount of self-tutelage could lead to advancement. For example, J. P. Mahaffy contemptuously called Edward Dowden “an autodidaktos” who “never worked under a Master.” According to Max Cullinan, an especially harsh critic of the institution in the Fortnightly Review, “A most distinguished Dublin ‘grinder’ [an academic coach] recently told this writer that his pupils frequently ask him whether they ought to attend lectures. His answer is, that, if they have plenty of time to spare, lectures can’t do them any harm.”

Stoker’s interpersonal skills and personal magnetism certainly had something to do with his receiving what was essentially an honorary degree based on his extracurricular activities and personal popularity. The role of his tutor, Dr. Shaw, is unknown, though they stayed on friendly terms long after Stoker’s graduation. But he certainly knew how to deploy personal charm, and he must have deployed it strategically and could easily have played the role of teacher’s pet if necessary. He was unusually bright, tall, athletic, and while not extraordinarily handsome was more than passably good-looking and, by 1870, quite accustomed to impressing people with both his brain and his body. He would later write, “I represented in my own person something of that aim of university education mens sana in corpore sans [from Juvenal: a sound mind in a sound body].” As one female acquaintance in Dublin remembered him, “He was an excellent ‘party’ young man, and of course, always had heaps of invitations.” She described his confident, imposing physicality: “When he stood up to dance, [he] had a way of making a charge, which effectively cleared a passage through the most thronged ball-rooms. Everyone made way for Stoker—his coming was like a charge of cavalry, or a rush of fixed bayonets—nobody dreamed of not giving way before him, and so he and his partner had it all their own way. How my heart used to jump in my dancing days when Bram Stoker asked me for a waltz! I knew that it meant triumph, twirling, ecstasy, elysium, ices, and flirtation!”

Bram Stoker, age twenty-five, serving as auditor of the Trinity College Historical Society for 1872–73.

He would have been attractive to men as well, on any number of levels, and in ways that were not overtly homosexual. However Stoker understood or found advantage in the homosocial dynamics of Trinity College, he knew how to work the all-male environment effectively enough to achieve an all-important objective: the validation of a college degree. By whatever means he used, he succeeded.

Because everyone made way for Bram Stoker.

Nonetheless, he would soon turn the trajectory of his own life over to the spell of a man far more charismatic and persuasive than himself, a legendary exercise in male bonding that would control and dominate his life for the next three decades.

Stoker’s interest in the theatre had continued straight through his Trinity years. He attended and greatly admired Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, the Theatre Royal’s pantomime for 1867. His love for wonder tales brought to life onstage had never left him. The other holiday offerings at the Theatre Royal during his college career included The House That Jack Built (1864), Beauty and the Beast (1865), Sinbad the Sailor (1866), Little Red Riding Hood (1868), Robinson Crusoe (1869), and The White Cat (1870).

At the end of August 1867, Stoker attended a production of Sheridan’s comedy classic The Rivals, performed by a London company at the Theatre Royal. It is a bit surprising Stoker had not chosen another of the company’s offerings—an adaptation of Lady Audley’s Secret, which had proven just as much of a sensation on the stage as on the page. But had he chosen the frightening charms of Lady Lucy Audley over the verbal manhandling of Mrs. Malaprop, he would have missed a performance destined to change his life.

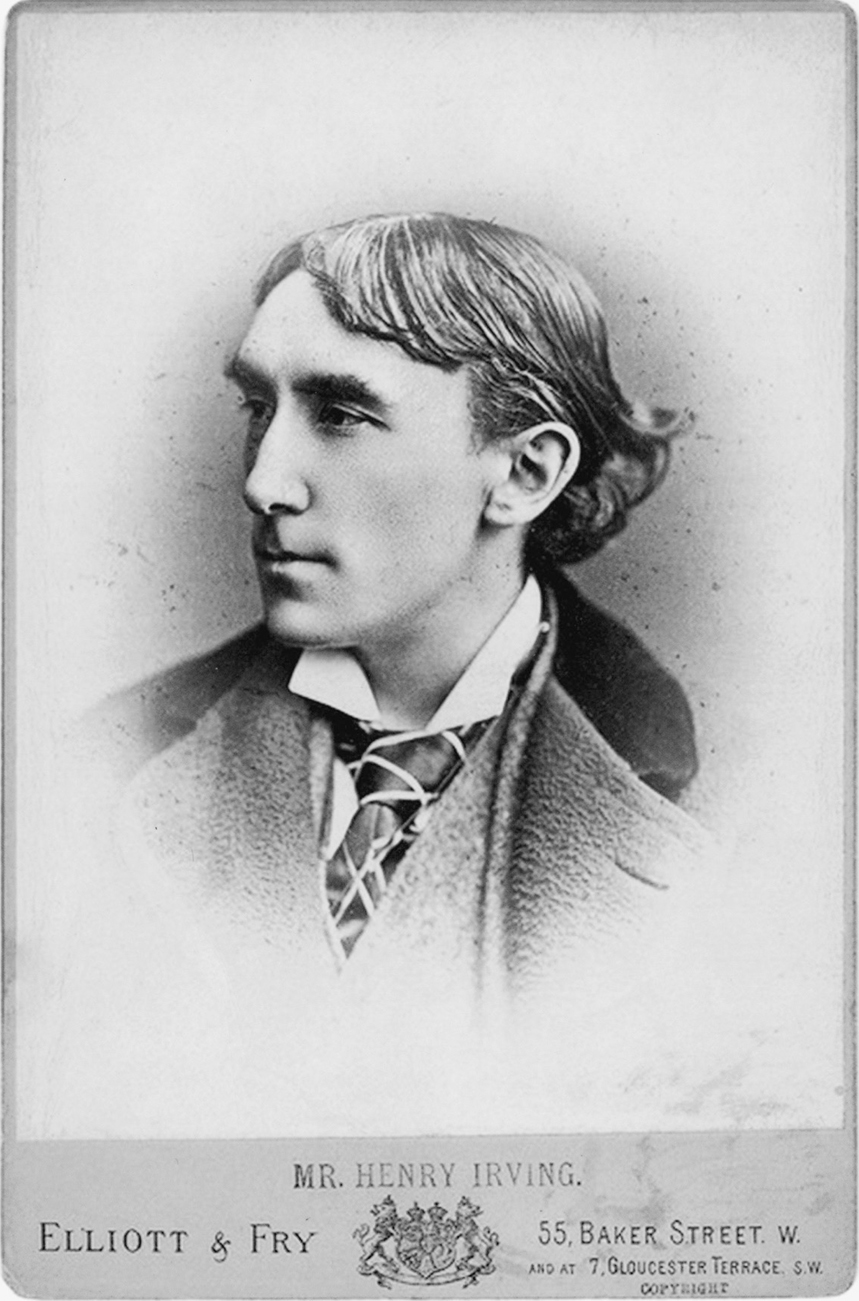

In the leading role of Captain Absolute, who woos the beautiful Lydia Languish under the assumed identity of a lowly ensign, was an actor whom Stoker found absolutely riveting. His stage name was Henry Irving. Born John Henry Brodribb (who had considered—and wisely rejected—“Henry Baringtone” as a professional moniker), Irving was a self-trained performer from the provinces who, like Stoker, had become infatuated with the theatre as a young boy. Unlike Stoker, who had fallen under the spell of the pantomime, Irving had a stage epiphany at a production of Hamlet.

Watching Irving act, Stoker had an epiphany of his own, one that exceeded even his discovery of the Christmas pantos, where his life had become real. Pantomime had introduced him to the theatre as a spectator, and now he was beholding the transformative figure who would invite him to step across the threshold. He was stunned, though hardly rendered speechless, by the impressively tall, angularly handsome thespian. “What I saw, to my amazement and delight, was a patrician figure as real as the persons of one’s dreams, and endowed with the same poetic grace . . . handsome, distinguished, self-dependent; compact of grace and slumbrous energy. A man of quality who stood out from his surroundings on the stage as a being of another social world. A figure full of dash and fine irony, and whose ridicule seemed to bite; buoyant with the joy of life; self-conscious; an inoffensive egoist even in his love-making; of supreme and unsurpassable insolence, veiled and shrouded in his fine quality of manner.”

To Stoker, Irving was a supreme, swashbuckling presence that “could only be possible in an age when the answer to insolence was a sword-thrust; when only those dare to be insolent who could depend to the last on the heart and brain and arm behind the blade.”

Souvenir postcard of Henry Irving as a rising actor in the 1870s.

Today, Stoker’s first-sight, swept-away infatuation with Irving might well be described by discreet circumlocutions of “man crush” or “bromance,” but they don’t do justice to a fixation that would eventually swell into an all-consuming, lifelong preoccupation. Stoker’s later, intimate friend Hall Caine commented on the Irving connection, “I say without any hesitation that I have never seen, no do I expect to see, such absorption of one man’s life in the life another,” and called Stoker’s devotion to the actor “the strongest love that man may feel for man.” The homoerotic implications were not openly commented upon during Stoker’s lifetime, but it is significant that the words “love” and “loving,” in Stoker’s personal writing and in his correspondence, are used almost exclusively to describe relationships with men. Though women could be greatly admired, closely befriended, or even married, depictions and discussions of heterosexual romance would remain within the constructs of Stoker’s fiction.

The Irving epiphany roughly coincided with the crumbling of Stoker’s academic work, and a general distraction with activities unconnected to formal study can easily be inferred. It would be nearly five years before Irving returned to Dublin—five years in which Stoker would throw himself into as much extracurricular distraction as his day job at Dublin Castle would allow, and that amounted to quite a bit. His modest salary still allowed him pit seats at the Theatre Royal. The surfeit of theatrical interests, athletic achievements, and go-for-broke commitments to the Hist and the Phil (with all the nighttime reading and preparation they demanded) raises the question: When, exactly, did “Abraham Stoker, Jnr.” ever sleep?

He didn’t directly witness Irving’s spectacular rise during this period, but the actor’s growing fame was steadily noted in the press. Irving reached a major professional plateau in 1871 with The Bells, a melodrama about an innkeeper, Mathias, whose carefully concealed murder of a Polish Jew is involuntarily revealed by court-ordered hypnotism and a truly show-stopping confession. The overwhelmingly positive reception of The Bells reflected not only Irving’s increasingly dazzling artistry but also the degree to which the general public enthusiastically responded to the claims made for mesmerism and pseudoscience in general.

What Stoker didn’t know about Irving included the tumultuous details of his hero’s domestic life. Irving had been married to the former Florence O’Callaghan since 1869. She had pursued him in the face of her father’s disapproval, only to be disappointed by the realities of the theatrical life, particularly the long hours and Irving’s garrulous actor friends, whom she found unbearable. After having their first child, the couple separated, then reconciled. Pregnant again, Florence was tired, resentful, and venomous. On the very night of his London triumph in The Bells, she snapped at him on the carriage ride home: “Are you going to keep making a fool of yourself like this for the rest of your life?”

Irving responded by abruptly quitting the carriage at the very corner of Hyde Park where he had proposed to her. He never forgave Florence, and never lived with or even spoke to her again. When his second son was born, he refused to attend the christening. The Irvings would remain married in name only.

Stoker, who would ultimately prove more unconditionally supportive of Irving than any wife, keenly anticipated the actor’s return to the Theatre Royal in late spring 1871, not with The Bells but with a meticulously studied character turn in James Albery’s comedy Two Roses. Once more, the local press couldn’t have cared less. According to Stoker, “There was not a word in any of the papers about the acting of any of the accomplished players who took part in it; not even their names.”

In Stoker’s telling it was a personal last straw, the culmination of “my growing discontent with the attention accorded to the stage in the local newspapers,” in whose pages he could find no reflection of his own keen appreciation of the theatre, and most particularly his feelings about Henry Irving. While Stoker would have us believe that the public was being deprived of his hero, Irving himself had a very different account of the Dublin engagement. “Two Roses has created in Dublin a theatrical excitement unknown for many years,” he wrote. “The dress circle (there are no stalls) which is the largest in any theatre out of London, holds 300 persons (and during our engagement the price has been raised from 4s. to 5s.) and on Saturday night it was crowded and on Friday too, with the elite and fashion of the city. This is here unprecedented. The dress circle, I am told, and sometimes with the most popular stars, is generally empty—comparatively and excepting Italian opera, which is here a great institution, such audiences as we have had are never drawn to the theatre.”

Stoker overestimated the power of the local press. And it was probably not the goal of motivating audiences as much as an ego-driven hunger to be published and read and recognized and, above all, become part of a world where giants like Henry Irving strode that led him to become a drama critic. He had begun keeping a journal of colorful local sketches and story ideas, and by this time had a drawer full of fictional juvenilia—the “scribblings” later described by his son. His burning desire to express himself on the printed page couldn’t have been less intense than his quest for athletic prizes, an activity that was now coming to an end.

Some might have considered his opinions (both of the theatre and of himself) prematurely lofty for a twenty-three-year-old, but at some time between May and November of 1871 Stoker took his grievances and ambitions directly to Dr. Henry Maunsell, co-proprietor of the Dublin Evening Mail.

The fact that it took him nearly half a year to approach the Mail suggests that he tried other publications without success. Since Maunsell’s ownership partner was J. Sheridan Le Fanu, it has often been suggested that the celebrated author of Uncle Silas, which Stoker greatly admired, somehow took a personal interest in the younger writer and facilitated his employment. But Le Fanu (who, a decade earlier, had also purchased the Dublin University Magazine) had grown increasingly reclusive after the death of his wife, who succumbed in 1859 after a losing struggle with an emotional disorder that included terrifying religious visions. Le Fanu thereafter became known as “Dublin’s Invisible Prince,” rarely venturing out of his Merrion Square residence, where he continued to write in solitude. In 1871, he was nearing his own death while preparing for publication a final collection of stories, In a Glass Darkly, containing the provocative vampire tale Carmilla, a major influence on Dracula. Since he had no hand in the day-to-day running of the Mail, speculation about his acquaintance with Stoker is mostly conjecture to force an interpersonal connection to Carmilla. Given Stoker’s lifelong weakness for name-dropping, had he had even the slightest relationship with Dublin’s leading literary lion, he would surely have been the first to tell.

In Dublin, plays opened on Monday evenings, but due to the time required to typeset and print the paper—the contents had to be “put to bed” around midnight—the timeliest reviews didn’t appear before Wednesday. The aspiring critic pointed out to Maunsell, quite rightly, that such an institutionalized delay was unfair to both the presenting theatre and the touring artists, who were often in Dublin for only a week. Stoker was a speedy writer and offered to quickly prepare first-night reviews for publication the next day, to be followed by more leisurely appraisals later in the week. Maunsell couldn’t have required much arm-twisting. After all, Dublin’s theatres were the paper’s most prominent advertisers, their bills posted each day on page one, top left, just under the masthead—the most advantageous and expensive placement possible. Anything that helped sell tickets helped the Mail as well, especially when snippets of its own reviews were recycled and paid for by the typeset line.

Maunsell told him that there was no money for the work, which was usually assigned to staffers. Stoker accepted nonetheless, later justifying his financial sacrifice as a kind of moral cause: “When the floodgates of Comment are opened, there comes with the rush of clean water all the scum and rubbish which has accumulated.” And, although he would have us believe his high-minded goal was to increase the quantity of clean critical water, another motivation is immediately discernible. Regular theatregoing was expensive on a civil servant’s salary, and about to become more so with the highly anticipated opening of another Dublin playhouse, the Gaiety, which would virtually double the local stage offerings—as well as the cost of attendance for a theatre-smitten young writer. Complimentary reviewer’s tickets were the keys to a kingdom he had long dreamed of entering.

He was also given unusual editorial latitude. “From my beginning the work,” Stoker recalled, “I had an absolutely free hand.”

Two weeks after his twenty-fourth birthday, on Monday, November 21, 1871, Stoker took his first night’s seat as a critic at the Theatre Royal, and his review appeared on Tuesday, a respectful evaluation of Amy Robsart, Andrew Halliday’s adaptation of the Sir Walter Scott novel Kenilworth. The title character was the wife of Robert Dudley, the first Earl of Leicester; the plot involved her clandestine and long-endured rivalry with Queen Elizabeth for his affections, and her ambiguous death, dramatized as murder in both the novel and the play. It is interesting to note, in this inaugural review, that Stoker tipped his hat toward the specific kind of production that first drew him to the stage. “In a spectacular sense it is simply excellent,” he wrote. “The one scene representing the grand pageant at Kenilworth [Castle] will suffer nothing by comparison with the finest scenes in our best pantomimes.”

All of Stoker’s reviews were published anonymously, but his identity was no secret, his authorial voice easily recognizable behind the royal-sounding editorial “we” affected by the twenty-four-year-old, self-appointed cultural arbiter of Dublin.

From the beginning, Stoker’s pieces reflected a keen eye for, and interest in, visual stagecraft—scene painting, costumes (“the dresses,” as they were called, for both male and female performers), and mechanical effects—all the most emphasized features of the pantomimes. “The story may be engaging, the libretto clever, and the acting good,” he wrote, “but still if the scenery and appointments are not in sufficient taste and splendor, the play will be, at best, a negative success—an escape from failure.” His further thoughts reflect an ongoing interest in the senses and sensationalism. “For of all the organs of sense the eye is the quickest and most correct in its working: the untrained ear may allow a discord to pass unnoticed, or the world-hardened body may be touched unknowingly, but the eye is never-failing in its receptive power; it is ever keen to judge of beauty or deformity. . . . The eye will infallibly judge of those minor details, from whose accumulated force the general effect arises.”

Not at all surprising, an emphasis on vivid scene-setting would later characterize his fiction; Dracula’s “general effect” is achieved through a pantomime-like procession of unforgettable imagery. It is difficult to overstate the impact of theatrical pantomime on Stoker. He began his work as a critic shortly before the holidays, and when the panto arrived at the Theatre Royal at the end of December, his newspaper appraisal went beyond normal reviewing into a series of effusive essays on the art and appeal of the beloved Christmas ritual, with the most interesting appreciation saved for a completely offstage aspect: the audience itself.

“To look at the legions of sparkling eyes, the parterres of flushed cheeks and pearly teeth that rise away from the footlights to the gloom beyond the galleries—to note the innumerable types of minds and bodies of those children who are the germs of men and women of the future—is, indeed, a pleasure,” he wrote, finding it “a curious study to observe the component elements of a juvenile audience,” including “numerous copies of young gentlemen [each of whom] considers himself quite a man of the world, and who secretly borrows his sister’s scissors to shave with, in the vain hope that he can force on his moustache by such artificial means.” He then describes the theatregoing youth, who—like the precocious and opinionated theatre critic—has quite an opinion of himself. “This individual appears in very tight gloves and a very large collar. He is at first quite at his ease—very much so, indeed—and gives fierce directions as to the observance of certain of the proprieties to his younger brothers and sisters, sotto voce. Gradually, however, the stiffness wears off as the good fairy who has her home in the Bowers of Orange-peel and Sawdust‡ begins to assert her sway. Our young friend then takes more interest in his brothers and his sisters and less in himself, and, in the expansion of heart, the change comes over him which came to the Ancient Mariner when he saw the water snakes playing around the becalmed vessel, and ‘blessed them unawares.’ ” Completing the Coleridge comparison, Stoker watches approvingly as his young alter ego “finds his reward, and the albatross slips from his neck,” when he discards “boyish snobbishness” and takes “the first step into real manhood.”

Real men are exemplified by the fathers in attendance and described collectively as “papa.” They are conventional middle-class males “who, we think, in our heart of hearts, [do] not care much for ogres, or dwarfs, or fairies. We know quite well that papa could beat any ogre, if he chose. However, papa is with us now, and seems to be enjoying himself. How he laughs at the shadow scene!”

Another less domesticated and less inhibited brand of masculinity was more to Stoker’s liking. Dublin was a major port city, and sailors on leave apparently took their pleasures beyond the local pubs and brothels. Stoker noticed this type with evident appreciation. “Everyone has observed the sailor in the pit, who chooses a juvenile night to go to the pantomime in preference to any other. He seems to take more enjoyment out of the play than anyone else, even the juveniles—for their enjoyment has occasional lapses into awe and fear, but his has not; indeed the giants and murderers are the most mirth-provoking to him. He does not even try to contain himself; he goes into the theatre to laugh, and is not ashamed. . . . He ‘glories in the act.’ He screams, roars, nay, he even chokes and gurgles with laughter, till he infects all around him with his own mirth.” The other audience members “hold rather aloof from him: they are affected with some of the morbid vanity that weights so heavily on the young man with the collar and the gloves, but gradually they join his mirth.” The sailor, wrote Stoker, “enjoys the pelting of the carrots, and the assault and battery of old women and policemen, as much as the wildest schoolboy in the theatre; and when [the actor] throws the policeman’s helmet into the pit, he seizes it wildly and flings it back again.”

Stoker also gives us a discursive theatrical aside on female family dynamics, presumably drawn from his own experience. He repeatedly refers to a boy as a sexually undifferentiated “it” acknowledged as male only in passing, an interesting echo of his own androgynous infancy. “The small child looks up with great veneration to its mother, and has a sort of well-bred affection for its older sister, who is its occasional playmate and the originator of most of its amusements; but it is chiefly to his aunt that it looks for that sympathetic appreciation of and participation in enjoyment which is so pleasant for the young and old.” The mother, perhaps, “is too high above its level, its sister is too near it, but the aunt who calls mamma by her Christian name, and who knows all the little secrets of both boys and girls, she is the real friend and chosen companion of the child.” The evidence? “Look how it clings to her and holds her hand when the roaring of the giants is heard. See how it turns its eyes to her for information when there is anything which it doesn’t misunderstand. Mark how it looks round in the height of its enjoyment, to see if aunty likes it too, and to gather a new joy from sympathy with her. Surely,” Stoker concludes, “there is no such sympathetic relative for a child, in its pleasures, at all events, as an aunt. We don’t count uncles.”

Since so many of Stoker’s observations on pantomimes and children are obviously self-referential, a question immediately arises: Was Stoker himself ever accompanied to the theatre by an aunt, or perhaps an older female cousin? His mother definitely had no sisters. Abraham was the youngest of six children who survived childhood;§ he had an older sister named Frances who married in 1816, but it is his unmarried sister Marian, born in 1778 (one year older than Abraham), who was likely to still be alive during Bram’s childhood.

The possibility of an extended Stoker family, including a stage-struck aunt, is intriguing. It is statistically unlikely that Bram’s grandfather William Stoker was an only child, and any brothers would have had sons, and the sons would have had wives. One of these might easily have been Eliza Sarah Stoker, an otherwise obscure family member represented by a single 1882 letter in the family papers. In the letter, addressed to an otherwise unidentified Mrs. Billington, Eliza describes herself as a former actress, forced into retirement and difficult circumstances after having broken her leg. Theatrical records reveal that an actress (or actresses) identified alternately as “Miss” and “Mrs.” Stoker was (or were) active at London’s Adelphi Theatre between 1850 and 1871. Or is it possible Eliza is the “Miss Eliza Pitt (Mrs. Stoker),” born in 1801 and died in 1885, who worked at the Adelphi under her maiden name from 1821 to 1823? Stoker biographer Paul Murray has suggested that Eliza Sarah Stoker’s difficult life may have been a reason Abraham cautioned his son against a life in the theatre. Another clue to Bram’s knowledge of or acquaintance with Eliza is that he used the name “Billington” for the fictional solicitor who facilitates the shipment of Dracula’s earth-boxes to England. It has been well established that Stoker was fond of using the names of real people in his stories.

Beyond his discussion of aunts (and dismissal of uncles), Bram closed his notice with a most intriguing statement. “Old maids are great at pantomimes,” he wrote, “but we have no time to do them justice now.” Here, the spinster Marian Stoker might fit the bill. Unfortunately, he never found the time to do the complete subject justice, but it would be fascinating to know Stoker’s thoughts about sexual frustration and the wanton allure of the stage.

A final observation on Stoker’s pantomime review is the inclusion of aunts, siblings, fathers, sailors, a curt dismissal of uncles—but no mention whatsoever of mothers as part of the cherished childhood excursion. Did Charlotte, perhaps, regard the theatre as frivolous, or of questionable morality? Such a prejudice was not at all uncommon among observant Protestants. It was the Catholics who went for pomp and theatre. Only five years later Charlotte would explicitly express her dismissive opinion of her son’s idol Henry Irving as “a strolling player.”

Disapproval at home might account for a condescending and slightly pompous tone that creeps into some of his reviews. Unwilling to criticize his parents directly, he can easily criticize Dublin and Dubliners generally. Some of his notices read like lecture notes that are as much demonstrations of his superior taste and theatrical knowledge as they are appraisals of performance. At times his impatience with Dublin and its audiences—already implicit in the know-it-all reviews—boils over into public scolding, as in his review of a particularly unpleasant night at the opera. “One sad drawback, we are sorry to say, is the behavior of the persons in the upper gallery,” he wrote of a Theatre Royal performance of Gounod’s Faust.

It is simply an abominable nuisance to all the rest of the house, and ought to be at once put an end to. We cannot speak of it as anything else than a sort of revival of Donnybrook Fair. The foolish and unmanly persons who create such a horrible din between the acts by their brawling wholly forget that the rest of the occupants of the house would much prefer perfect silence so that the past portions of the opera might dwell in their memories, and assist their pleasurable anticipation of what is to come. But instead of that they are night after night compelled to listen to vulgar attempts at singing, the coarse vanity displayed in which is the most offensive feature of the whole thing. . . . It is high time that there should be an end of what would not be tolerated in any other civilized city.

Stoker may have been especially irked because the disruptions occurred during Faust, an opera that particularly fascinated him and would influence the writing of Dracula. He attended several productions of the Gounod opera in Dublin and eventually witnessed Henry Irving play Mephistopheles in his own dramatic version more than eight hundred times, in London and on tour. Mephistopheles was a character drawn from morality plays and pantomimes and in many ways embodied the magical essence of theatre for Stoker during his formative years.

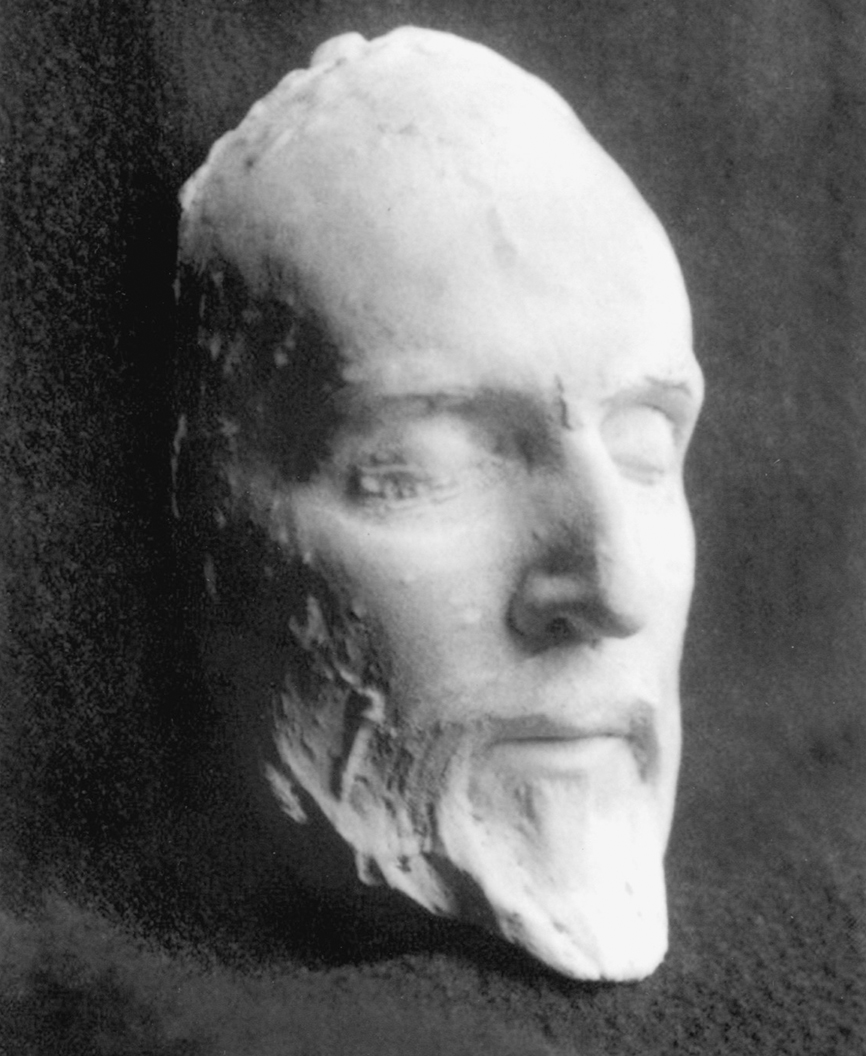

Another work that left its stamp on Stoker’s imagination was J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, about a vampire who cheats death for nearly two centuries. (A supernaturally extended life is also a key ingredient in Faust.) Published when Le Fanu was less than a year away from his own last breath, Carmilla would become his most famous, provocative, and influential piece of fiction—not least of all in the shadow it left upon Dracula. The story drew surprisingly little critical attention when it appeared, and no reviews at all in Dublin. It is set in Styria, a region of Austria, and concerns a mysterious visitor named Carmilla Karnstein, seemingly a young woman, and her passionately malignant fixation on the first-person narrator, Laura. “Sometimes after an hour of apathy, my strange and beautiful companion would take my hand and hold it with a fond pressure, renewed again and again; blushing softly, gazing in my face with languid and burning eyes, and breathing so fast that her dress rose and fell with the tumultuous respiration,” reads one of its more provocative passages. To Laura, Carmilla’s hungry attention “was like the ardour of a lover; it embarrassed me; it was hateful and yet overpowering; and with gloating eyes she drew me to her, and her hot lips travelled along my cheek in kisses; and she would whisper, almost in sobs, “You are mine, you shall be mine, and you and I are one for ever.”

Due to the appalling neglect of Le Fanu’s immediate heirs in preserving his papers, neither the manuscript nor any working notes for Carmilla have survived, so it is not possible to ascertain his precise inspiration for so obviously a lesbian vampire. A fashion for morbid Sapphism had, however, taken root in the poetry of Coleridge, Baudelaire, and others, and Le Fanu may have simply decided to appropriate the exotic conceit in prose. Today, no discussion of Carmilla omits the lesbian theme, but the topic was never raised critically until the twentieth century. A contemporary review by the Saturday Review found the whole idea of vampires unwholesome enough. The anonymous appraiser felt that readers “may be thankful to be spared an account of the most foolish and offensive of all his tales—that, namely, of the Vampire. When an author has the grave opened of a person who had been buried one hundred and fifty years, and describes how ‘the leaden coffin floated with blood, in which, to a depth of seven inches, the body lay immersed,’ we are, we think, more than justified in declining to analyse his silly and miserable story. We should hope that this time he will find he has miscalculated the taste of the subscribers to seaside lending libraries, for whom he probably writes.”

Death mask of J. Sheridan Le Fanu, author of Carmilla.

(Copyright © Anna and Francis Dunlap, all rights reserved)

Given Carmilla’s bloody footprints all throughout the text of Dracula, there can be no doubt that Stoker was thoroughly familiar with the story, even if his personal relationship with the reclusive Le Fanu remains conjectural. As an admirer of Le Fanu’s fiction, he would have eagerly anticipated In a Glass Darkly, the 1872 collection in which it appeared, if he had not already read its 1871–72 serialization in the magazine The Dark Blue. One suggestive piece of evidence that he read the story near the time of its original publication is a curious contemporaneous entry in his journal—the description of a coverlet made of cat skins. In Carmilla, the vampire comes to Laura’s bed, covering her in the form of a cat.

But another previously presumed influence on Dracula, that of Dion Boucicault’s melodrama The Vampire: A Phantasm (1852), may be nonexistent. The Dublin-born Boucicault was a playwright, actor, and manager-producer, and one of the nineteenth century’s leading theatrical personalities in the English-speaking world. Stoker first met and talked with him in Dublin in 1872, during a long repertory engagement at the Theatre Royal. Boucicault is best known today for still-revived plays like London Assurance (1841) and The Shaughraun (1874). The Vampire was written for the acclaimed actor Charles Kean, who rejected it, leaving the acting chores to Boucicault himself.

The reception was mixed—Queen Victoria herself attended the production at London’s Princess Theatre twice, and, while initially impressed with Boucicault’s performance as the bloodsucking revenant Sir Alan Raby (“I can never forget his livid face and fixed look. . . . It still haunts me,” she wrote in her journal), she had second thoughts about the play itself upon a repeat viewing. “It does not bear seeing a second time,” Victoria concluded, “and is, in fact, very trashy.” That didn’t, however, deter the Queen from commissioning a watercolor portrait of Boucicault in costume. “Mr. Boucicault . . . is very handsome,” she admitted, adding that he “has a fine voice” and “acted very impressively.”

Boucicault shortened and revived the play as The Phantom at Wallack’s Theatre in New York in 1856, after which he completely dropped it from his repertory, despite reports of excellent American box office. Neither version ever played Dublin, and if Stoker later read the published script, he would have found little inspiration for his own vampire. For instance, Boucicault’s was brought back from death by moonlight and was dispatched with a gunshot. Stoker would eventually standardize the governing rules of literary vampirism through other, largely folkloric sources. His first and quite possibly his solitary exposure to a vampire onstage, only very recently documented, occurred just after Christmas 1872, when he reviewed a Boxing Day performance of The Vampire, a comic dance piece set to Offenbach, at the Gaiety, calling it “a ballet of great cleverness and novelty.” The Vampire, Stoker wrote, “is a good deal after the manner of a harlequinade in a pantomime, but, at the same time, has perfectly original characteristics.” But the morning performance Stoker witnessed was more than a little slapdash in execution. “Nobody expects a first performance of such an entertainment to in any way approach perfection; but when one finds that stage appurtenances won’t work, or, in plainer terms, are not worked, somebody is surely accountable.” His heart went out to the “Mr. Collier” who invented and performed the piece, for being placed in “an awkward and embarrassing position. These remarks apply mainly to the morning performance of The Vampire; in the evening the improvement was most notable.” Whether he returned for the second show out of concern for Mr. Collier or the simple fascination of the subject matter, we will never know for sure, but we are free to hazard a guess.

Among the stage devices prone to dysfunction were any of the various trapdoors that were a standard feature of pantomimes. The pentagonal star trap was the most spectacular. Actors playing sprites or demons were gymnastically launched from below the boards by a system of counterweights, up through the air above the stage, the jaws of the five-pointed trap snapping shut just in time to catch their landing. The mechanism required dexterity on both the part of stagehands and performers, and casualties were not unknown. Stoker would twice make melodramatic use of star trap mishaps in his fiction. An alternate device, the vampire trap, introduced in (and named after) James Robinson Planché’s The Vampire; or, The Bride of the Isles (1820), was a less tricky affair, employing painted rubber flaps permitting a performer to suddenly enter or exit through an apparently solid wall or floor. When it was combined with strategic lighting, fog, or flash bombs, ghostly appearances and disappearances were startlingly impressive.

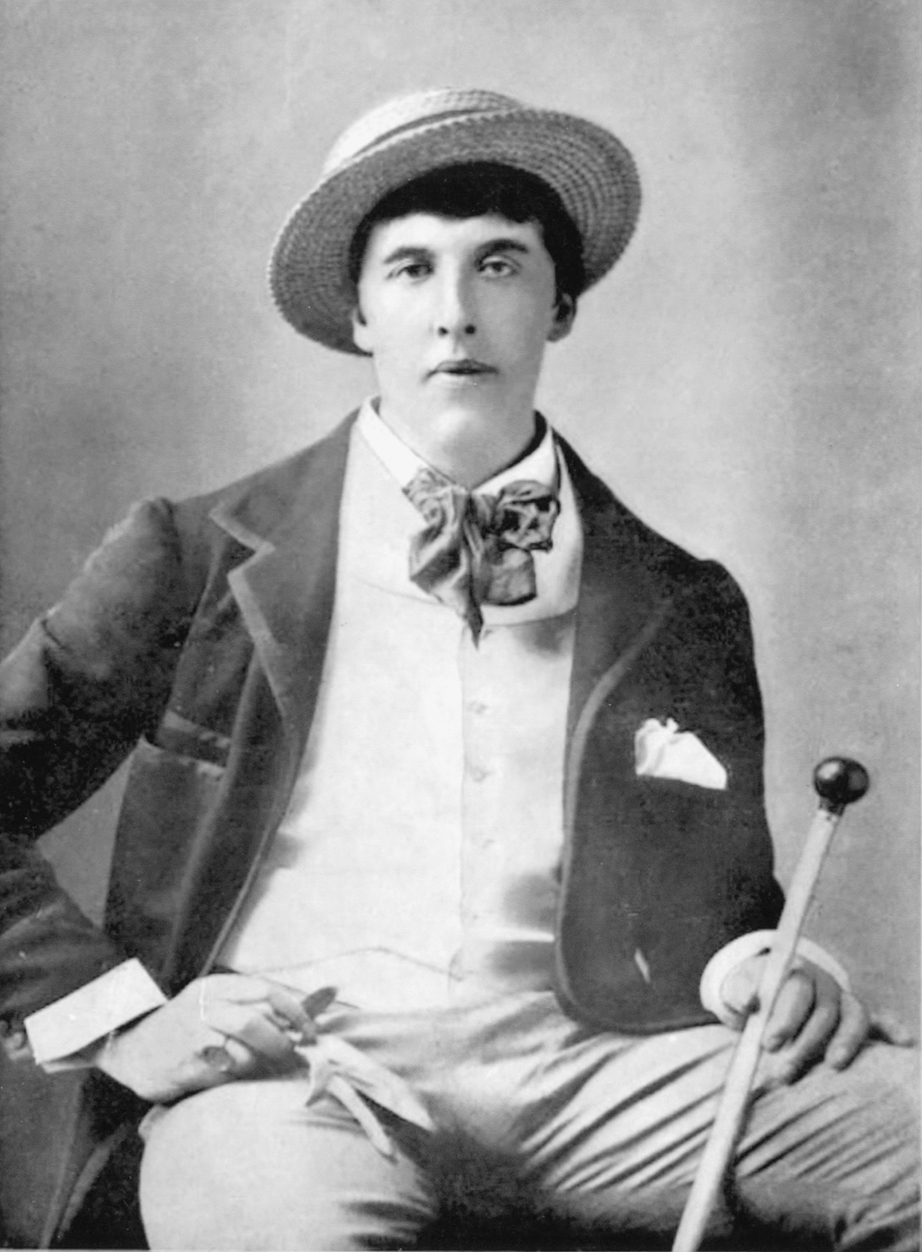

One of Stoker’s new acquaintances, and one who especially adored dramatic entrances, was Lady Jane Francesca Wilde, flamboyant wife of Sir William and mother of two sons: Willie, who attended Trinity at the same time as Bram, and Oscar, who matriculated a bit later. By the early 1870s Stoker had become a regular at her salons. Writing as “Speranza,” Jane was a fiery poetess of Irish nationalism, revolutionary by temperament and outlandish in demeanor, a Catholic-leaning avatar of bohemianism with a quick and acerbic wit, who seems to have been as much drawn to Stoker as he to her.

It is sometimes suggested that Stoker first made the acquaintance of the Wildes through his mother, eager to advance her son in Dublin society. This speculation is based on Charlotte’s reading of her 1864 pamphlet essay “On Female Emigration from Workhouses” at the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland. Sir William Wilde was among the society’s founding members (one of roughly sixty), but it is not known whether he actually attended Charlotte’s January 20, 1864, presentation, or whether he was even aware of her. No doubt, she addressed the society for the simple reason that it was one of the few institutions in Dublin that would permit the equal participation of women.

Charlotte would have known Sir William far better from a messy Dublin scandal in 1864 in which a young woman, Mary Travers, accused him of rape after having been anesthetized by chloroform in his surgery. She stalked the Wildes and distributed defamatory pamphlets in which Sir William was barely disguised as the rapacious “Dr. Quilp.” When Jane publicly denounced her, it was she who was sued for libel. The resulting trial might have taken place in a sensation novel. Travers won the suit, but the court expressed its contempt by awarding her a mere farthing in damages.

Sir William was indeed a notorious philanderer. One of his critics speculated that he “had a family in every farmhouse in Ireland.” He supported one illegitimate son in Dublin and paid for his training as an eye doctor. Two out-of-wedlock daughters had been moved discreetly to County Monaghan and drew little attention, but in November 1871 they died horribly after their dresses were set ablaze at a ball. They were both rolled down the outside steps into the snow, to no avail. In the absence of any effective treatment for serious burns and infection, they lingered miserably for two weeks. The tragedy was quietly kept out of the Dublin newspapers, but that hardly stopped the gossip.

Oscar Wilde as a young dandy.

The personal hygiene of Sir William and his sons was also a regular target of ridicule. A nasty joke circulated among Trinity men: “Why are Sir William’s fingernails black?” The answer: “Because he scratched himself.”

Could Charlotte Stoker’s reaction to Jane Wilde and her family, and her son’s association with them, have been anything but revulsion? Bram had chosen to keep company with a surrogate mother of dubious moral character—her son Oscar flippantly described her salon as “a society for the suppression of Virtue”—and whose every social, cultural, and religious value was the diametric opposite of her own. It was a slap in the face. Bram had been robbed of a normal early life but had found a way to act out adolescent rebellion in young adulthood, establishing his own identity clearly separate from that of his family.

“Portraits of her husband, sons, and dead daughter [Isola Wilde, who died in 1867 at age nine] depended brooch-like from parts of her person,” wrote Wilde family chronicler Joan Schenkar, describing Jane moving among her guests, “dispensing outrageous comments far more liberally than her tea.” The resurrection of Isola as a postmortem fashion accessory led a guest to describe the child’s mother as “a walking family mausoleum.” (It is possible Stoker had his first glimpse of Oscar in one of these pendulous brooches. There are very few photographs of Oscar in his youth; his brooch may well have displayed the three-year-old boy in his dress, next to the real daughter in hers.) Moon-faced and moon-driven, she entered a room as if by tidal propulsion. “She must have had two crinolines on,” one guest observed, “for as she advanced there was a curious, swaying, swelling motion like that of a vessel at sea. Over the crimson silk were flounces of Limerick lace, and round where there had been a waist was an Oriental scarf. In her hands, always gloved in white, she carried a bottle of scent, a lace handkerchief and a fan.”

A fantastical species of feminine female impersonator, Lady Wilde was not far removed from the outlandish dames of the Christmas pantomimes who had captured Bram’s imagination in childhood. And therein may have lain another, potent aspect of her appeal.

If ridiculing her manner of dress didn’t satisfy, critics could, and did, focus mercilessly on her face and body. She wore heavy makeup, “too thick for any ordinary light,” compounded the offense of vanity by covering candles with pink shades, and even in daytime pulled the curtains, the better to “hide the decline of her beauty and the shabbiness of her furniture.” In a further avoidance of bright light, she rarely had guests before five in the afternoon. It is only appropriate that this sun-repelled woman of the shadows provided Bram Stoker one of his most memorable descriptive phrases in Dracula: “children of the night,” the vampire’s evocative description of gathering wolves, was originally her own description, in Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland (1887), of the Berserker-like, wolf-skinned warrior tribes of ancient Ireland.

Oscar Wilde’s friend and biographer Robert Sherard missed any Dracula connection, but definitely saw in Lady Wilde forewarnings of The Picture of Dorian Gray. “Her clinging to youth, her efforts to mask the advance of age, her horror for the stigmata of physical decay,” Sherard wrote, “were all characteristics which she transmitted to her son.” Wilde’s writings, Sherard notes, “are full of rhapsodic eulogies of youth; he never tires of satirising maturity and old age.” Dorian Gray would roundly satirize Victorian vanities, all the while emphasizing stigmata and horror.

Lady Jane Wilde, idealized and in travesty. Watercolor portrait by Bernard Mulrenin (1864).

A particularly vicious caricature by Punch cartoonist Harry Furniss.

Attacks on Lady Wilde were more than skin deep, and were extended with relish to her general person, if not her genetics. George Bernard Shaw, a Dubliner who later came to know the Wildes in London, offered a peculiar biological theory, an odd exercise in full-body phrenology: “You know there is a disease called gigantism, caused by ‘a certain morbid process in the sphenoid bone of the skull—viz., an excessive development of the anterior lobe of the pituitary body’ (this from the nearest encyclopedia). ‘When this condition does not become active until after the age of twenty-five, by which time the long bones are consolidated, the result is acromegaly, which chiefly manifests itself in an enlargement of the hands and feet.’ ” Shaw admitted to never having seen Lady Wilde’s feet, “but her hands were enormous, and never went straight to anything, but minced about, feeling for it. And the gigantic splaying of her palm was reproduced in her lumbar region.”

Given such appraisals, one might well imagine Lady Wilde as a kind of oversized Irish piñata, endlessly bludgeoned with shillelaghs. Punch cartoonist Harry Furniss depicted her and her husband as ridiculous zoo specimens. Seen from behind, her callipygian figure is expanded to elephantine proportions, and Sir William shrunken and shriveled into a kind of clinging monkey. The adjective “simian” was regularly deployed by his detractors; in a letter attributed to Trinity don and classicist Robert Tyrrell, the similar ape-slur “pithecoid” was used.

The year 1871 marked the publication of Darwin’s The Descent of Man, and its explicit linkage of humankind to lower animals had much to do with the ensuing Victorian penchant for atavistic discourse, which would reach an apex (or nadir) at the time of Oscar Wilde’s downfall, when Speranza’s son would be described as something almost literally subhuman. But the cultural preoccupation with animalism was a pump already primed by the dominant view of physical, mental, and spiritual progress as enduring Christian virtues. Mind-body-soul backsliding had long been the stuff of cultural metaphors, even without Darwin.

Lady Jane and Sir William Wilde, caricatured by Henry Furniss.

Oscar Wilde’s preparatory education, at the Portora School in the north of Ireland, coincided almost exactly with Stoker’s academic career at Trinity. The two young men could have met at one of Lady Wilde’s salons when Oscar was on holiday from Portora, but it is more probable that their first encounter occurred after Oscar’s graduation, when he came home to matriculate at Trinity in late 1871. His leave-taking from boarding school had been accompanied by a distinct personal revelation, and the first glimpse of the unconventional life journey that awaited him.

A surprisingly insistent schoolmate had insisted on accompanying him to the train station for his departure to Dublin. As Oscar remembered, “he did not say ‘goodbye’ and go, and leave me to my dreams, but brought me papers and things and hung about.” The friend made it clear he intended on staying on board the train until the sound of the station guard’s whistle. When the signal came and the train began to move, the boy suddenly exclaimed, “Oh, Oscar,” and “before I knew what he was doing he had caught my face in his hot hands and kissed me on the lips. . . . I became aware of cold, sticky drops trickling down my face—his tears.” Oscar wiped his face and experienced an epiphany:

“This is love: this is what he meant—love.”

Disoriented, Oscar trembled, “all shaken with wonder and remorse.”

Whenever Bram and Oscar actually met, their similarities and dissimilarities would have been immediately apparent. They were both blue-eyed, tall, and physically imposing. They were both precocious, ambitious, intellectually gifted young Dubliners with a passion for literature and the arts, but were polar opposites in their response to Trinity’s emphasis on physical culture—in all senses of the term. Oscar had little use for Trinity men, whom he dismissed as “barbarian” and “worse than the boys at Portora. . . . They thought of nothing but cricket and football, running and jumping; and they varied these intellectual exercises with bouts of fighting and drinking. If they had any souls they diverted them with coarse amours among barmaids and the women of the streets; they were simply awful. Sexual vice is even coarser and more loathsome in Ireland than it is in England.”