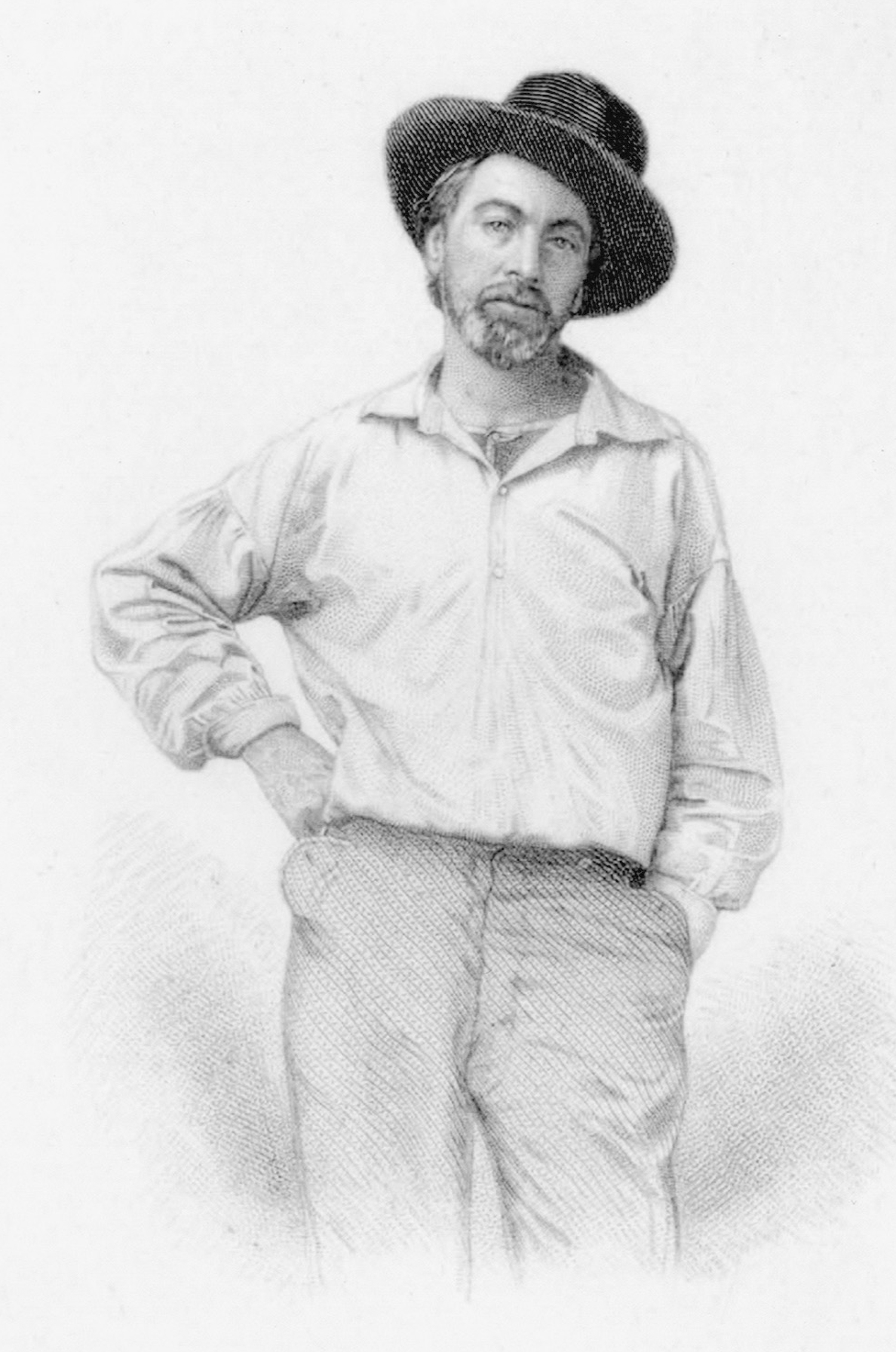

Walt Whitman’s poetry electrified Bram Stoker’s generation. Frontispiece engraving for Leaves of Grass (1854).

Walt Whitman’s poetry electrified Bram Stoker’s generation. Frontispiece engraving for Leaves of Grass (1854).

SONGS OF CALAMUS, SONGS OF SAPPHO

LET SHADOWS BE FURNISHED WITH GENITALS!

— Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

Gypsy-like as ever, the Stoker family continued their series of Dublin relocations during Bram’s college years. By the age of twenty-four he had known seven family homes, moving an average of once every three years and four months, and always, presumably, because of money. The household had pulled up stakes again in the mid-1860s, taking a new address at 5 Orwell Park, Rathgar, on Dublin’s south side, and by the beginning of the 1870s they were back in the city center at 43 Harcourt Street, an address that would be retained by Thornley until his successful medical practice earned him an exceptionally handsome house at one of Dublin’s best addresses on St. Stephen’s Green.

The rest of the family would never be quite so comfortable. Abraham retired from the civil service in 1865 on a modest pension. He remained heavily in debt after putting four sons through college—three through medical school—and having borrowed against a life insurance policy. The family’s special attention to finances is reflected in Charlotte’s meticulous ledger of expenditures, in which the rising monthly cost of meat is clearly recorded. Her monthly payments to the Rathgar Road butcher Edward Flynn rose sharply in a five-year period, from £29 in early 1867 to £70 at the beginning of 1872, and even more as the year wore on. The inflationary pressure must have been horrendous, and a prime reason for the family’s constant relocations over two and a half decades.

Among the most prominent themes in Irish history are emigration and expatriation. By 1872 Charlotte had determined that the cost of Abraham, Matilda, Margaret and herself living abroad in Italy, France, and Switzerland, in pensiones, would be more advantageous than remaining in Dublin. While the move might be glamorized (or rationalized) as some grand and well-earned retirement tour of the Continent, it appears to have been a move dictated primarily by money, not wanderlust, and they put off saying their farewells repeatedly. Charlotte must have chafed at the ugly irony of personally facing the kind of economic exile she had once fervently advocated for the most destitute Irish women. Now she confronted a genteel version of their banishment herself. Abraham and the Stoker women finally said good-bye to Bram and his brothers in the summer of 1872. For Abraham, the leave-taking would be permanent.

The family departure also marked a year in which Stoker would have yet another of his life-changing epiphanies, this time the momentous discovery of an American poet. In 1868, William Michael Rossetti had published Selected Poems of Walt Whitman, the British debut of selections from Leaves of Grass (1855, but revised and expanded for the rest of the poet’s life). To Whitman’s chagrin, the volume was heavily edited, but even a bowdlerized Whitman shook the literary world with lyrical blank verse that embodied the voice of the American everyman. “Embodied” is the operative word, for the Whitman cosmos, as unforgettably proclaimed in “I Sing the Body Electric,” revolved around a physical self that transcended all dualities of mind and spirit: “And if the body does not do fully as much as the soul? / And if the body were not the soul, what is the soul?”

Evoking transcendentalism, pantheism, and the all-pervasive “electricity” of mesmerism, Whitman tackled the nineteenth century’s struggle to reconcile the spiritual with the material. In an age when communication with the ethereal dead was all the rage, and “materialization” provided the big bang at séances, Whitman’s poetry effectively coaxed together protoplasm and ectoplasm. These were also interests of Stoker’s, prompted by his first-year college readings of the philosophical writings of Victor Cousin, which urged him not to forget that the soul was bodiless and immortal, whatever science might say. Such ideas dovetailed with a growing fascination with pseudoscientific belief systems, especially mesmerism and phrenology/physiognomy. Whitman was an avid phrenologist, believing that human personality traits had physical locations within the cranium. It helped that his own phrenological readings indicated a superior character.

Stoker heard a great deal about Leaves of Grass before he ever read it. He first read of Whitman three years earlier, in the October 1869 issue of the London magazine Temple Bar, which featured an anonymous essay titled “The Poetry of the Future.” The piece began as a seemingly evenhanded evaluation of the American poet but quickly took sides. Some of Whitman’s partisans had rapturously embraced the poet as the second coming of Homer, and the critic was determined to provide a corrective. Whitman’s style had “nothing in common with either the Bible, Shakspeare, or Plato.”*

Stoker related, “For days we all talked of Walt Whitman and his new poetry with scorn—especially those of us who had not seen the book.” But when he met a man on campus actually carrying a copy, he asked to see it. “Take the damned thing!” was the man’s reply. “I’ve had enough of it!” Stoker took the book to College Park, the site of most of his athletic events, “and in the shade of an elm tree began to read it. Very shortly after my own opinion began to form; it was diametrically opposed to that which I had been hearing. From that hour I became a lover of Walt Whitman.”

Whitman’s disregard for traditional poetic conventions and structure offended many, but what really disturbed certain readers from 1855 onward was his frank discussion of sex, and not just ordinary male-female sex, but seemingly endless references to affectionate male-male camaraderie and “manly love,” including men kissing and embracing, and perhaps even more, given all the blunt talk about “man-balls” and “man-root” along the way. The rigid stalks of calamus grass, evoked in the particularly controversial section of poems entitled “Calamus,” were quickly understood by many to be phallic symbols, while other readers were much slower on the erotic uptake.

To modern sensibilities, Whitman is tame indeed, but in the mid-1800s his language was unprecedentedly shocking to general readers, and unprecedentedly liberating to a specially intended audience. Whitman’s verses often referred to women, but they were evoked in a muscular, ambiguously earthy language. It was Whitman’s manner of winking at male readers in the know.

“The bitter-minded critics of the time absolutely flew at the Poet and his work as watch-dogs do at a ragged beggar,” Stoker wrote. “In my own university the book was received with Homeric laughter, and more than a few of the students sent over to Trübner’s† for copies of the complete Leaves of Grass—that being the only place where they could then be had. Needless to say that amongst young men the objectionable passages were searched for and more obnoxious ones expected.”

However, as he had to admit, “unfortunately, there were passages in the Leaves of Grass which allowed of attacks.”

The initial, most vociferous barrage had come in America, from Rufus Griswold in the pages of the Criterion. Griswold had been the dubious, self-appointed literary executor of Edgar Allan Poe and was largely responsible for the sordid, slanted accounts of Poe’s alcoholic death, which a good number of scholars now question. Griswold had even less regard for Whitman’s character. He called Leaves of Grass “a mass of stupid filth” that “serves to show the energy which natural imbecility is occasionally capable of under strong excitement.” He accused the poet of promulgating the “degrading, beastly sensuality, that is fast rotting the healthy core of all the social virtues.” In simply describing the book, Griswold “found it impossible to convey any, even the most faint idea of its style and contents, and of our disgust and detestation of them, without employing language that cannot be pleasing to ears polite; but it does seem that some one should, under circumstances like these, undertake a most disagreeable, yet stern duty. The records of crime show that many monsters have gone on in impunity, because the exposure of their vileness was attended with too great indelicacy. “Peccatum illud horribile, inter Christianos non nominandum.”

Griswold couldn’t bring himself to describe homosexuality—“That horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians”—but he clearly interpreted passages as doing so. He wouldn’t be alone. The following lines from “Song of Myself” in particular have long been interpreted as a paean to oral sex between men:

I mind how once we lay such a transparent summer morning,

How you settled your head athwart my hips and gently turn’d over upon me,

And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my bare-stript heart,

And reach’d till you felt my beard, and reach’d till you held my feet.

As Stoker recalled, “From these excerpts it would seem that the book was as offensive to morals as to taste.” His Trinity friends “did not scruple to give the ipsissima verba [exact words] of the most repugnant passages.”

Stoker never divulged his own favorite sections, or commented in any way on the content or meaning of Leaves of Grass. But it means something that his Whitman epiphany coincided with the height of his athletic obsession with his own body and the bodies of other competitive young men. Whitman spoke in a private poetic code to a wide audience of male readers discovering, or grappling with, troublesome emotions. In “Two Vaults,” he wrote: “These yearnings why are they? These thoughts in the darkness why are they? / I hear secret convulsive sobs from young men at anguish with themselves.”

Other lines, more open about secret yearnings, may have spoken directly to Stoker the sportsman: “For an athlete is enamored of me—and I of him, / But toward him there is something fierce and terrible in me, eligible to burst forth, / I dare not tell it in words.”

Although universally recognized today as an icon of gay history, Whitman never openly acknowledged his affairs with men. Indeed, the language barely existed to do so. In the 1870s, the word “gay” described heterosexual promiscuity in general, and female prostitution in particular. Same-sex attraction and behavior between men was almost universally condemned as aberrant and immoral, but was also considered a moral failing that could potentially entrap anyone. In this sense the Victorians, usually considered narrow-minded, were actually rather expansive in their understanding of the sexual spectrum, even if they disapproved of one end. The word “homosexual” was coined in Germany by Karl Maria Kertbeny in an 1869 pamphlet advocating the repeal of Prussian sodomy laws and didn’t appear in English until the 1891 translation of Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis, where it was used as a clinical adjective; it was never used as a noun designating a person or class of persons with an innate orientation during the lifetime of either Whitman or Stoker. The term and concept of “heterosexuality” were similarly confined to obscure medical usage until the 1920s, when it first appeared officially in the Merriam-Webster dictionary and popularly in the New York Times Book Review (as “hetero-sexuality.”)

In the many public controversies it generated, Walt Whitman’s poetry received no overt support for its homoeroticism, but it accrued more palatable accolades for the proxy values of freedom, progressiveness, comradeship, and red-blooded manliness. At Trinity College, Whitman received a spirited defense from growing ranks of students, including Stoker. “Little by little we got recruits among the abler young men till at last a little cult was established,” he wrote in his reminiscences. “We Walt Whitmanites had in the main more satisfaction than our opponents. Edward Dowden was one of the few who in those days took the large and liberal view of the Leaves of Grass, and as he was Professor of English Literature at the University his opinion carried much weight.”

Only four years older than Stoker, Dowden today would be considered an academic rock star. He blazed across the Trinity firmament, being elected professor of oratory and English at the age of twenty-four. He was personally attractive as well as intellectually formidable. One of his students wrote that his appearance “recalls the features which Vandyke so loves to paint. He has a handsome, dreamy face, with pointed beard and a soft, somewhat melancholy voice. He is surrounded by a coterie of literary and would-be literary people. . . . By his admirers, he is regarded with an almost idolatrous affection.”

At a meeting of the Phil on May 4, 1871, Dowden brought the topic of Whitman’s poetry to an audience Stoker called “the more cultured of the students” with his paper “Walt Whitman and the Poetry of Democracy.” Stoker was given the honor of opening the debate that followed.

Edward Dowden, academic wunderkind of Trinity College Dublin, and Stoker’s mentor.

Dowden couldn’t avoid talking about Whitman and sex, but a truly honest discussion of the kind of sex the poet was writing about—much less a defense of it—would have been a public impossibility. And we honestly don’t know what Dowden privately thought or felt on the subject of male-male sex, only that in public he adopted the roundabout, ultimately disingenuous approach that would color Whitman studies for decades to come. “If there be any class of subjects which it is more truly natural, more truly human not to speak of . . . then Whitman has been guilty of invading that sphere of silence,” Dowden said in his paper.

He deliberately appropriates a portion of his writings to the subject of the feelings of sex, as he appropriates another, “Calamus,” to that of love of man for man, “adhesiveness” as contrasted to “amativeness,” in the nomenclature of Whitman, comradeship apart from all feelings of sex. That article of the poet’s creed, which declares that man is very good, that there is nothing about him which is naturally vile or dishonourable, prepares him for absolute familiarity, glad, unabashed familiarity with every part and act of the body.

“Adhesiveness” and “amativeness” were concepts drawn from phrenology, which located love for men (adhesiveness) and love for women (amativeness) at specific places in the brain, readable in the shape and bumps and ridges of the skull. However odd it seems today, phrenology had an enormous following and deep cultural penetration in the nineteenth century,‡ and it seems to have been useful for people who wanted to parse their personalities and categorize, analyze, and control troubling drives and passions.

In the year that followed Dowden’s lecture, Stoker had ample time to examine his mind, body, and soul in light of Whitman’s revelatory worldview. He learned from Edward Dowden that Whitman was planning a visit to England to meet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Dowden had asked him to extend his trip with a stay in Dublin—and share the visit with Dowden and himself. “Dowden was a married man with a house of his own. I was a bachelor, living in the top rooms of a house, which I had furnished myself. We knew that Walt Whitman led a peculiarly isolated life, and the opportunity which either one or other of us could afford him would fairly suit his taste.” Offering a bed to Walt Whitman? Could it actually happen? Time passed and there was no confirmation of Whitman’s trip. Finally, when Stoker could no longer contain his feelings, he spilled them all into a letter to the poet himself.

DUBLIN, IRELAND, FEB 18, 1872

If you are the man I take you to be you will like to

get this letter. If you are not I don’t care whether you

like it or not and only ask that you put it into the fire

without reading any farther. But I believe you will like

it. I don’t think there is a man living, even you who

are above the prejudices of the class of small-minded

men, who wouldn’t like to get a letter from a younger

man, a stranger, across the world—a man living in

an atmosphere prejudiced to the truths you sing and

your manner of singing them. The idea that arises in

my mind is whether there is a man living who would

have the pluck to burn a letter in which he felt the

smallest atom of interest without reading it. I believe

you would and that you believe you would yourself.

You can burn this now and test yourself, and all I will

ask for my trouble of writing this letter, which for

all I can tell you may light your pipe with or apply to

some more ignoble purpose—is that you will in some

manner let me know that my words have tested your

impatience.

What an opening. Stoker repeatedly challenges Whitman to destroy his letter, with four incendiary references: to “put it in the fire,” “have the pluck to burn a letter,” “You can burn this now,” and “You may light your pipe with [it].” That last suggestion, to use the paper “for some more ignoble purpose,” went beyond self-effacement, essentially reducing himself to toilet paper. Perhaps he is trying to appeal to Whitman’s earthiness. But in one sense he is talking to himself as much as to Whitman, both messages implying “Stop me before I write more.”

Put it in the fire if you like—but if you do you will

miss the pleasure of the next sentence which ought

to be that you have conquered an unworthy impulse.

A man who is certain of his own strength might try

to encourage himself by a piece of bravo, but a man

who can write, as you have written, the most candid

words that ever fell from the lips of a mortal man—a

man to whose candor Rousseau’s Confessions is

reticence—can have no fear for his own strength. If

you have gone this far you may read the letter and I

feel in writing now that I am talking to you. If I were

before your face I would like to shake hands with

you, for I feel that I would like you. I would like to

call YOU Comrade and to talk to you as men who are

not poets do not often talk. I think that at first a man

would be ashamed, for a man cannot in a moment

break the habit of comparative reticence that has

become second nature to him; but I know I would not

long be ashamed to be natural before you. You are a

true man, and I would like to be one myself, and so

I would be towards you as a brother and as a pupil

to his master. In this age no man becomes worthy of

the name without an effort. You have shaken off the

shackles and your wings are free. I have the shackles

on my shoulders still—but I have no wings. If you are

going to read this letter any further I should tell you

that I am not prepared to “give up all else” so far as

words go. The only thing I am prepared to give up

is prejudice, and before I knew you I had begun to

throw overboard my cargo, but it is not all gone yet.

More mysteries. Almost as if he is teasing his idol to guess, or intuit, exactly what he isn’t ready to “give up.”

I do not know how you will take this letter. I have not

addressed you in any form as I hear that you dislike

to a certain degree the conventional forms in letters.

I am writing to you because you are different from

other men. If you were the same as the mass I would

not write at all. As it is I must either call you Walt

Whitman or not call you at all—and I have chosen

the latter course. I do not know whether it is usual for

you to get letters from utter strangers who have not

even the claim of literary brotherhood to write you.

If it is you must be frightfully tormented with letters

and I am sorry to have written this. I have, however,

the claim of liking you—for your words are your own

soul and even if you do not read my letter it is no less

a pleasure to me to write it. Shelley wrote to William

Godwin and they became friends. I am not Shelley

and you are not Godwin and so I will only hope that

sometime I may meet you face to face and perhaps

shake hands with you. If I ever do it will be one of the

greatest pleasures of my life.

After an extraordinary preamble—a former athlete’s warming up, perhaps—Stoker finally introduces himself properly.

If you care to know who it is who writes this, my name

is Abraham Stoker (Junior). My friends call me Bram.

I live at 43 Harcourt Street, Dublin. I am a clerk in the

service of the Crown on a small salary. I am twentyfour

years old. Have been champion at our athletic

sports (Trinity College, Dublin) and have won about a

dozen cups. I have also been President of the College

Philosophical Society and an art and theatrical critic

of a daily paper. I am six feet two inches high and

twelve stone weight naked and used to be forty-one

or forty-two inches around the chest. I am ugly but

strong and determined and have a large bump over

my eyebrows. I have a heavy jaw and a big mouth and

thick lips—sensitive nostrils—a snubnose and straight

hair. I am equal in temper and cool in disposition and

have a large amount of self control and am naturally

secretive to the world. I take a delight in letting

people I don’t like—people of mean or cruel or

sneaking or cowardly disposition—see the worst side

of me. I have a large number of acquaintances and

some five or six friends—all of which latter body care

much for me. Now I have told you all I know about

myself.

All he knew about himself? Perhaps he believed Whitman would immediately glean what he needed through his knowledge of phrenology. If Whitman spoke in code, than so could Stoker. The disclosure of a bump on his forehead is intriguing, since it was a trait that did not bode well under phrenological scrutiny. Some practitioners would have said it indicated a tendency toward murder. The details about his jaw, nose, and mouth might also have been associated with “degenerate” behavior of various kinds by criminal physiognomists. Stoker might well have been signaling his own anxiety over the possibility of hidden negative tendencies. He also seems to have a peculiarly distorted self-image: no photograph of him reveals lips that are particularly thick (they actually look rather thin), the small protuberances above his eyes look completely normal, and by no stretch of the imagination does any Dublin portrait support his self-description of being “ugly.” And as for that “worst side of me”—what on earth were those unpleasant people shown, and surprised to see?

I know you from your works and photograph,

and if I know anything about you I think you

would like to know of the personal appearance

of your correspondents. You are I know a keen

physiognomist. I am a believer of the science myself

and am in a humble way a practicer of it. I was not

disappointed when I saw your photograph—your late

one especially.

It is not clear which photos Stoker references, or how “late” the more recent one was. The famous daguerreotype of a rugged, behatted young Whitman from the original 1855 Leaves of Grass was reproduced in Rossetti’s Selected Poems of Walt jWhitman. Photos early in the Civil War show a ruggedly handsome Whitman strongly resembling Ernest Hemingway; from the end of the war onward he assumes the more familiar persona of a long-bearded, Gandalf-like sage.

The way I came to like you was this. A notice of your

poems appeared some two years ago or more in the

Temple Bar magazine. I glanced at it and took its

dictum as final, and laughed at you among friends.

I say it to my own shame but not to regret for it has taught

me a lesson to last my life out—without ever having seen

your poems. More than a year after I heard two men

in College talking of you. One of them had your

book (Rossetti’s edition) and was reading aloud some

passages at which both laughed. They chose only

those passages which are most foreign to British ears

and made fun of them. Something struck me that I

had judged you hastily. I took home the volume and

read it far into the night. Since then I have to thank

you for many happy hours, for I have read your poems

with my door locked late at night and I have read

them on the seashore where I could look all round me

and see no more sign of human life than the ships out

at sea: and here I often found myself waking up from

a reverie with the book lying open before me. I love

all poetry, and high generous thoughts make the tears

rush to my eyes, but sometimes a word or a phrase of

yours takes me away from the world around me and

places me in an ideal land surrounded by realities

more than any poem I ever read. Last year I was

sitting on the beach on a summer’s day reading your

preface to the Leaves of Grass as printed in Rossetti’s

edition (for Rossetti is all I have got till I get the

complete set of your works which I have ordered from

America). One thought struck me and I pondered

over it for several hours—“the weather-beaten vessels

entering new ports,” you who wrote the words know

them better than I do: and to you who sing of your

land of progress the words have a meaning that I can

only imagine. But be assured of this, Walt Whitman—

that a man of less than half your own age, reared a

conservative in a conservative country, and who has

always heard your name cried down by the great mass

of people who mention it, here felt his heart leap

towards you across the Atlantic and his soul swelling

at the words or rather the thoughts. It is vain for me

to quote any instances of what thoughts of yours I like

best—for I like them all and you must feel you are

reading the true words of one who feels with you. You

see, I have called you by your name. I have been more

candid with you—have said more about myself to you

than I have ever said to anyone before.

If the last statement is true, Stoker was truly secretive. Despite its emotionality, the letter actually says very little about him, but much about his unwillingness to reveal anything more than brief biographical detail, a physical description, and a passionate admiration for Whitman’s poetry.

You will not be angry with me if you have read so far.

You will not laugh at me for writing this to you. It was

with no small effort that I began to write and I feel

reluctant to stop, but I must not tire you any more. If

you would ever care to have more you can imagine,

for you have a great heart, how much pleasure it

would be to me to write more to you. How sweet a

thing it is for a strong healthy man with a woman’s

eyes and a child’s wishes to feel that he can speak to a

man who can be if he wishes father, and brother and

wife to his soul.

The last sentence is the one most often cited by Stoker commentators. It wasn’t the first time he had expressed almost the identical sentiment, if only in his private journal the year before. On August 1, 1871, he made the entry “Will men ever believe that a strong man can have a woman’s heart & the wishes of a lonely child?” In another, undated entry he writes, “I felt as tho’ I were my own child—I feel an infinite pity for myself—Poor, poor little lonely child.” His letter to Whitman is shot through with a sense of loneliness, even if he never uses the word. He is reaching out for a different kind of friend than those he knows in Dublin.

I don’t think you will laugh, Walt Whitman, nor

despise me, but at all events I thank you for all the

love and sympathy you have given me in common

with my kind.

BRAM STOKER

Although he managed to finish the letter—and we have no idea how many false starts may have been involved—he could not bring himself to mail it. At least not then. He kept it hidden—in a drawer, or perhaps folded in a book—for the next four years. The letter remains the most personal and passionate document Stoker ever wrote (or, at least, that has survived), but until now it has never been quoted in full for any biography or Stoker critical study. This may well be because it raises as many questions as it seems to answer.

On first reading, the letter does seem to support the notion that Stoker is making a bold psychosexual disclosure—especially given everything we know about Whitman today. But Stoker’s description of himself as having “a woman’s eyes” is curious; since we already know he considers himself unattractive, he’s surely not talking about prettiness. Rather, it suggests a strongly transgender perspective (“eyes” here intended as “viewpoint”) that is not necessarily homosexual. Perhaps it was not Whitman’s barely disguised descriptions of male-male lust that attracted Stoker to Leaves of Grass as much as the poetry’s all-pervasive androgyny. On the other hand, one of the common “explanations” of homosexual desire at the time, first advanced by pioneering German activists of the 1860s in a plea for tolerance, was that a female soul had somehow become trapped in a male body. For anxious men of Stoker’s generation, with no other real model for understanding contrarian sexual feeling, the idea of “inversion” sounded plausible and became deeply ingrained.

A major difficulty in making modern sense of sexual identities from the horse-and-buggy age is the tendency to wear twentieth- and twenty-first-century horse blinders. Today’s popular understanding of sexual orientation is an either/or, gay/straight template, seemingly drawn from the off/on binary switching of digital information. Computers are actually terrible models for understanding the human mind and body, much less the subjectivity of emotional attractions, but the idea is stubborn and pervasive. And, although the acronym LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) is used ubiquitously today, suggesting some monolithic homogenization, there is often a contentious and suspicious relationship between the comprised groups. Despite recent clinical studies finally affirming the existence of bisexuality, and decades of research indicating that human sexuality falls on a wide and often ambivalent spectrum many gays and straights still reject the idea that true bisexuality even exists.

Understanding Bram Stoker’s mind and imagination may require a willing suspension of this kind of psychological straitjacketing. (In the final analysis, after honestly considering the vastness and variety of human attraction and the infinite shadings of desire, it may be a fair conclusion that we are all sexual minorities of one.) Stoker lived in a time when the lines between same-sex friendship and same-sex sex often blurred, and people didn’t necessarily worry about it. As historian Jonathan Ned Katz notes in Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality, “The universe of intimate friendship was, ostensibly, a world of spiritual feeling. The radical Christian distinction between mind and body located the spiritual and the carnal in different spheres. . . . And yet, from our present standpoint, we can see that these intimate friendships often left evidence of extremely intense, complex desires, including, sometimes, what we today recognize as erotic.” Katz cites evidence of “a surprising variety of physical and sometimes sensual modes of relating among male friends in the nineteenth century.”

Stoker’s circle of friends and acquaintances in the worlds of theatre and literature would include a significant number who could be easily described with such Victorian euphemisms as “bohemian,” “confirmed bachelor,” “female bachelor,” “artistic,” “intensely private,” “hero worshipper,” and many other circumlocutions for persons with unconventional affectional preferences, many of whom would not fit easily into our present-day system of sexual pigeonholing.

Or, to alter only slightly one of the most famous lines from Hamlet, one of Stoker’s favorite plays, “There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in your sexology.”

By the end of 1872, Stoker had two publications appear under his byline, “Abraham Stoker.” His first known short story, “The Crystal Cup,” was published in the September number of London Society magazine. An unnamed first-person narrator is held against his will in a castle, anguished over the fate of his beloved, Aurora. He channels all his life energy—literally—into the creation of a beautiful crystal vase, which absorbs his soul upon its completion. The vase is displayed at a royal event, the Festival of Beauty, where the narrator (or his ghost) sees the heartbroken Aurora, now the dejected consort to a morose King. The exquisite beauty of the crystal moves Aurora to sing.

Sad and plaintive is the song; full of feeling and tender love, but love overshadowed by grief and despair. As it goes on the voice of the singer grows sweeter and more thrilling, more real; and the cup, my crystal time-home, vibrates more and more. . . . The monarch looks like one entranced, and no movement is within the hall. . . .The song dies away in a wild wail that seems to tear the heart of the singer in twain; and the cup vibrates still more as it gives back the echo. As the note, long-swelling, reaches its highest, the cup, the Crystal cup, my wondrous home, the gift of the All-Father, shivers into millions of atoms.

A metaphysical maelstrom engulfs the narrator. “Ere I am lost in the great vortex,” he concludes, “I see the singer throw up her arms and fall, freed at last, and the King sitting, glory-faced, but pallid with the hue of death.”

A striking example of Stoker’s juvenilia, the story owes a strong debt to Poe, indicating a youthful familiarity with the American master of the macabre. The story takes place in a kingdom by the sea, where two lovers have been separated and one imprisoned, an homage to “Annabel Lee;” the words “never more” appear repeatedly, clear echoes of “The Raven;” and the device of a soul transmigrating into a work of art provides the climax of Poe’s story “The Oval Portrait” (“And then the brush was given, and then the tint was placed; and, for one moment, the painter stood entranced before the work which he had wrought; but in the next, while he yet gazed, he grew tremulous and very pallid, and aghast, and crying with a loud voice, ‘This is indeed Life itself!’ turned suddenly to regard his beloved:—She was dead!”) The overwrought atmosphere of storm and struggle in “The Crystal Cup” also points to a familiarity with Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, and German Romanticism in general.

The second publication was the text of his November 13 Hist address, “The Necessity for Political Honesty.” Although it included an explicit allusion to one of his favorite pieces of dark literature, Macbeth, “The Necessity” couldn’t have been a more different piece of writing than “The Crystal Cup.” The lecture was a rhetorical tour de force, and a bit of a humorous jab. The Hist’s bylaws prohibited outright political debate, but Stoker cleverly contrived to talk about politics without bringing up a single political argument (although he almost crossed a line with some thoughts on Ireland that effectively declared his nationalism). The society’s proscription on politics was outdated and counterproductive, Stoker argued.

Oratory is not in itself a sufficient object for a body like ours. It is an art as well as a science—it needs practice as well as theory; and the aspiring speaker must have some materials with which to work. We can no more practice oratory, as an art by itself, than we can chisel a statue from the air, or work an engine without fuel. Not the mere articulation of syllables, but the expression of ideas makes an orator, and, without ideas to express, his words are as

—a tale

“Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

The address then turned to Irish identity. “The Celtic race is waking up from its long lethargy, and another half century will see a wondrous change in the position which it occupies amongst the nations of the world,” he wrote, echoing the sentiments of Lady Wilde without explicitly calling for home rule. Instead, he predicted that a Celtic revival would be most fully realized in the United States. The Irish people, “this leavening race of future America—this race which we young men may each of us directly and indirectly influence for good or ill, may become in time the leading element of Western civilization.” Stoker’s romantic fascination with the American experiment, fueled by his fascination with Walt Whitman, would only continue to grow. After the address, he received a certificate for oratory, and his tutor George Ferdinand Shaw made the successful motion to have the address printed at the Hist’s expense.

The following year brought sad news. Walt Whitman had suffered a debilitating stroke at his home in Camden, New Jersey, and was now partially paralyzed. “He could at best move, but a very little; the joys of travel and visiting distant friends were not to be for him.” Stoker already considered Whitman a friend, even though he had never mailed his letter of introduction.

Even without Whitman on hand, the general subject of blurred gender was not too difficult to find in Dublin in 1873. Stoker reviewed, with apparent pleasure, an “Operatic Boufferie” at the Gaiety called Kissi-Kissi, a topsy-turvy confection about transvestism. The Persian princess Kissi-Kissi “has evinced a strong partiality to strong sports and exercises, greatly to her father’s horror.” The father doesn’t know his daughter is actually a son, his sex concealed from birth by his mother, fearful of her boy being conscripted. Kissi-Kissi, who also believes she is a girl, has a “timid lover” named Kikki-Wikki. But Kissi-Kissi’s masculine side “makes up for her lover’s shyness, and they vow eternal devotion to each other. Alas for the course of true love!”

A less amusing treatment of impossible love took shape the following year in Stoker’s unpublished poem “Too Easily Won,” entered in his private journal. Sexually ambiguous, it is addressed to a male object of adoration who rejects the poet’s declaration of love:

So ends my dream. My life must be

One long regret and misery

Loved not, though loving, what care I

How soon I die.

For whilst I live my wail must ever run

Too lightly won! Too lightly won.

His heart when he was sad & lone

Beat like an echo to mine own

But when he knew I loved him well

His ardour fell.

Love ceased for him whene’er the strife was done

And I was won. Too lightly won.

Had I been fickle, false or cold

His love perchance I might still hold

Alas! To grieve for spoken truth

For blighted hope—for ruined youth

Oh life of woe and anguish soon begun

Alas! For love too lightly won—too lightly won.

Whether the poem is read as a man’s heartbreak over another man, or as Stoker experimentally writing from a woman’s point of view, normative gender boundaries are provocatively blurred.

As if he didn’t have enough to occupy himself, in late 1873 Stoker accepted the position of editor for a new four-page daily, the Irish Echo. The paper mixed general news and commentary with digested pieces from other papers and telegraph services, colorful local vignettes, and, not surprisingly, drama criticism, or at least the space to expand on his shorter pieces in the Evening Mail. Correspondence with his family indicates that the work was remunerative, if undependably so, unlike his ongoing work for the Mail, and it supplemented his civil service income until the spring of 1874, when the overall demands on his time and energy may well have reached a breaking point and he resigned.

At this juncture one might ask: Exactly what constituted a breaking point for Stoker? The Echo job was an editorial one-man show, the original writing being all his. It is impossible to imagine a daily schedule entailing a full-time civil service job and work for two daily papers that required him to attend two of Dublin’s major theatres several nights a week—including frequent return visits to let readers know about improved performances and technical problems overcome; the endless, enthusiastic follow-up reports on his beloved pantomimes especially suggest an almost literal camping-out at the Theatre Royal and the Gaiety night after night after night. He was also writing fiction, more than he actually published; his first encounter with Walt Whitman occurred serendipitously in the pages of the Temple Bar magazine, which he initially read for its light fiction, and to which he would soon, albeit unsuccessfully, submit his own fledgling stories.

How could any human being accomplish this much work? By some fantastic ability to complete work in a special dimension outside the constraints of time? Via some supernatural skill at being in more than one place at the same time, through astral projection? Through an unknown form of permanent, high-functioning insomnia? By helpful intervention of the fairies? In the real world, only one thing makes sense—that Stoker simply stole the time for journalism, criticism, and fiction writing during his day job at Dublin Castle. It would not be difficult for a man with prodigious mental organizational skills and almost effortless capacity for quick written expression to run rings around the typical bureaucrat, a species notorious for stretching all work to the maximum time allotted. He completed his daily assignments in record time, discreetly maintained his personal notebooks, and simply didn’t let anyone be the wiser. Why should he?

While the Echo job lasted, Stoker infused the paper freely and anonymously with his own personality; beyond the stage reviews, the paper was peppered with humorous filler and anecdotes that often read suspiciously like many of his own droll journal entries. On November 25, 1873, he entertained readers with a secondhand account of another sea monster first reported by the San Diego Union, in which a certain Captain Charlesworth and his crew, hunting curlew along the coast, instead encountered in a cove

a frightful monster, fully thirty feet in length, shaped like a snake, with three sets of fins, a tail like an eel, and a head like an alligator’s. The head was a little wider than the neck, but very thick at the base, and had small eyes, which appeared to be covered with a dark skin, which assumed a yellowish cast on the belly. The three pairs of fins were shaped like those of a sea lion, were each between three and four feet in length, the forward pair being much the heaviest, and situated about two feet back of the neck. . . . [Charlesworth] said the terrible looking thing had drawn itself nearly out of the water, and was lying motionless on the sand when he first saw it. At his approach the serpent fish raised its head and swung it directly towards him, and as he was not more than a couple of rods off, his only thought was to increase that distance.

The crew fired at the thing, but since their guns were loaded with birdshot, the result was predictable. Stoker’s taking notice of a monstrous snake story may have been prompted by the simple novelty of the report, but the material also resonated with him on an imaginative level. Every child in Ireland grows up with snakes, or at least images of them. The serpent is extraordinarily prevalent in Irish folklore, even if the reptile is not native to the island. As a symbol of paganism imported by the Celts, serpents were supposedly banished by St. Patrick, but they have never left Irish art and iconography. The familiar, decorative Celtic knot is a stylized snake symbol, and it slithers all over the form of many a Celtic cross. Decorative serpents abound in the illuminated pages of the Book of Kells. Snake imagery had already begun to appear in a cycle of fairy tales Stoker was writing, even though he wouldn’t publish them for another decade. His novel The Snake’s Pass would evoke Ireland’s legendary past, and his final book, The Lair of the White Worm (1911), would use the snake as an image of overwhelming, nightmarish horror. But in the case of the San Diego monster of 1872, his attitude is skeptically humorous.

Another tongue-in-cheek report in the Echo recounts an EXCITING SCENE IN ST. JAMES CHURCH, in which a London vicar “worked up one of those sensational sermons now too often delivered in churches. The subject was ‘Death.’ Gradually, and undoubtedly fluently, he had nearly disposed of every member of different families, when a lady, who appeared to be a widow, about sixty or seventy years of age, went into hysterics.” She fainted and was removed to the vestry. The sermon continued, resulting in two more women collapsing and being carried out, “after which the service was obliged to be closed, otherwise there is no doubt there would have been some danger of an accident occurring, as the people had risen from their seats and were getting very excited.” Had Stoker lived to review the West End stage adaptation of Dracula, produced fifteen years after his death, he would have been similarly amused by the fainting/collapsing stooges attending his own strange sermon on mortality.

Stoker ran another mordantly funny item, PINCHING AN ACTRESS. It told of an actor in Plymouth who, unhappy with the capability of an actress playing the Marquise de Pompadour to convincingly die in his arms, gave her a sharp pinch to induce the appropriate convulsion. “We have heard that ‘the gallows is the only thing to put life into an Irishman and make him quicken his paces,’ although this was the first occasion on record in which a pinch in the side has been found necessary to make a lady die properly. The magistrates dismissed the case, as well they might. It would never do just at Christmas time to make an assault on the stage a punishable offense, and even in our most quiet seasons Macbeth must not indict Macduff for a murderous attack.” Stoker concluded that “if it is a part of a woman’s business to die on stage before a provincial audience,” she should “show at least as much physical distress in the region of the heart as a pinch in the side will help her to do.”

But the most significant personal contribution Stoker made to the Echo was a hitherto unknown short story, “Saved by a Ghost,” which appeared on December 26, 1873. Boxing Day was also the usual debut date for the annual pantomimes, which were hardly the only fantastical tradition associated with an English Christmas. The telling of ghost stories on or around Christmas was a venerable British ritual, a persisting vestige of pagan times, when the winter solstice, the longest, darkest night of the year, was believed to be especially attuned to the supernatural.

Stoker published “Saved by a Ghost” anonymously, like everything else he wrote for the Echo, but it has many of the features of his later fiction, including a fascination with seafaring, supernatural or otherwise, and male comradeship. The story begins with an unidentified speaker asking simply, “Do any of you believe in ghosts?” The person addressing us is Captain Charles Merwin, “standing with his back to the fire in the coffee room of the Royal Hotel, Liverpool,” who has clearly secured his audience’s attention, as well as the reader’s. “The reason I ask,” he continues, “is because a ghost was a principal cause of a sudden reformation, which has been the making of me.”

Then, in an unbroken monologue, he recounts an incident from seventeen years past. At the age of eighteen, the captain tells us, he was already “a thorough sailor and a thorough drunkard.” Homeward bound from the East Indies, with “an unusually hard crew, all of them, except myself, being taken out of gaol and put on board the ship in irons,” he suspects foul play when the third mate, Billy McLellan, goes into convulsions while Charles writes a letter for him, and dies in his arms. Charles himself is named as the dead man’s replacement while a plot is hatched among the discontented crew to poison the officers with arsenic and force a landing for replacement officers. Then, one night, Billy returns.

It did not frighten me, but I was considerably astonished. There he sat, natural as in life, with his night dress on, and the right sleeve of his shirt rolled up above the elbow. His eyes were cast down, and he was occupied with his pocket-knife cutting a notch on the top of my chest. I was so astonished that I was not sure whether I was asleep or awake, but after pinching myself several times, I concluded I was in full and perfect possession of my senses. I then tried to speak, and asked, “Is that you, Billy?” As soon as I had spoken the apparition looked up and full at me with a smiling face. This gave me more courage, and after a moment I asked, “What do you want, Billy?” At this question the smile on the face turned to a scowl, such as I had often seen in life when something displeased him.

Billy thereafter becomes a protective spirit, repeatedly alerting Charles to fights brewing on the ship, which, to all observers, he has an uncanny ability to anticipate and stop. But he doesn’t foresee the difficulties that follow his captain’s request that Charles personally hold twenty-seven thousand rupees in freight fees. A bank failure in Bombay prevented him from depositing the money. “He did not dare to leave it on shore, or change it into notes and keep it on his person, for fear of robbery; and the banks were all slinkey, and on the verge of breaking; bills of exchange were worthless.” Actually, he sees the chance to steal the rupees by blaming their loss on Charles, whom he knows to be a drunkard, previously dismissed from more than one seafaring position. Charles came to this ship sober after Mary Tracey, the daughter of an Irish hotelier in Bombay, promised to marry him if only he could prove himself reformed. The money scheme is a Faustian bargain, almost literally, since the captain is being advised by a mysterious man from Bombay: “The stranger was introduced to me as the ship’s agent. I had seen the man’s face before, but could not tell where. It was an intelligent but evil-looking countenance, made more sinister by the carefully-waxed and jet-black Mephistophelian moustache which decorated his face. Liquors were put on the table, the doors closed.”

For the moment, Charles abstains, but the pact includes a key to the captain’s cabin, where he is encouraged to help himself to a drink anytime he likes.

Left to myself, I became very lonesome, very blue, and very beat, and in a moment of weakness I thought that a bottle of “Bass’s Pale Ale” would be good company and act as an antidote to the blues, and cool me off. I only thought twice of it before I got a bottle and drank it. It acted like a charm. My loneliness and the blues disappeared in company, and I didn’t mind the boat a bit. In about ten or fifteen minutes I drank another pint, and a dim recollection entered my mind that there was a decanter of brandy somewhere on board.

The captain returns, and this time insists on sharing the brandy. After an uncounted number of additional drinks, Charles goes back to his bunk to pass out atop the chest containing the freight money. Hours later, the sound of breaking wood startles him, but even more disquieting is the sight of Billy’s ghost standing next to his bunk, pointing at the captain and his henchman—the same sailor who had poisoned Billy—who has begun to break open the chest with a hatchet. In the ensuing struggle, the hatchet man is killed—Charles seizes the weapon and axes him several times in the head—while the captain begins to stab Charles. He hears a gunshot as he slips into unconsciousness.

Weeks later he awakens in the Traceys’ hotel and finally understands what happened. After giving Charles drugged brandy, the captain and the ominous agent had met onshore at the same hotel and were overheard by Mary discussing the details of their plot, including the fact that Charles had been drugged. She takes her father’s revolver and follows them back to the ship in a dinghy. Coming upon the captain raising his knife over Charles for a final, fatal thrust, she shoots him. We learn that he lives to stand trial and be sentenced for life to a chain gang in Pulo Penang. The owners of the ship make Charles captain, and a year later he and Miss Tracey marry.

“Not until I fully established my reputation for sobriety did I tell my wife I had drank liquor on that day,” says Charles, “and as she had learned to trust me, it did not cause her much trouble then.” He assures his listeners that he never took another drink, and that Billy McLellan never again appeared to him. “Now, gentlemen,” he finishes, “my story’s told; you know how I was saved from the gutter, got command of a ship, and gained a wife—all through a ghost.”

“Saved by a Ghost,” only his second published piece of fiction, already evidenced Stoker’s keen interest in the fictional possibilities of the returning dead, as well as a fascination with the Faust legend, which would only grow. As a holiday tale of supernatural redemption, Stoker’s story observed the template of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1843). Dickens continued to entertain readers with spooky Yuletide offerings in his popular newspapers Household Words and All the Year Round. Although Marley’s ghost is the best-remembered vestige of the tradition, it had its roots in the early juxtaposition of Christmas with the winter solstice, which, like November Eve, had great supernatural significance to pagan cultures. In The Winter’s Tale (circa 1611), Shakespeare tells us, “A sad tale’s best for winter: I have one. Of sprites and goblins.” Christopher Marlowe, in The Jew of Malta (1589), writes of the seasonal tales of old women “that speak of spirits and ghosts that glide by night.” In the late Victorian era, best-selling writer Jerome K. Jerome’s Told after Supper (1891) assured readers that “whenever five or six English-speaking people meet before a fire on Christmas Eve, they start telling ghost stories. Nothing satisfies us on Christmas Eve but to hear each other tell authentic anecdotes about spectres.” As he noted, “There must be something ghostly in the air of Christmas—something about the close, muggy atmosphere that draws up the ghosts, like the dampness of the summer rains brings out the frogs and snails.” The tradition enjoyed an Edwardian revival at Cambridge after World War I, when the King’s College provost, M. R. James, supplemented his prodigious scholarship with legendary, exclusive-invitation Christmas Eve gatherings at which he would read aloud the ghost stories he wrote for his own pleasure, and which became classics of the genre. First collected and published in 1931, they have never been out of print.§

Aside from ghost stories—a plentiful British commodity in the 1870s—Stoker had frequent exposure to uncanny themes in the operas he reviewed for the Evening Mail. Bellini’s La Sonnambula was presented twice at the Theatre Royal during Stoker’s tenure as critic. Like mesmerism, sleepwalking would be a significant plot element of Dracula; in his review of the 1875 Hawkins Street production, Stoker took special notice of the character Amina, a Swiss ingénue whose uncontrollable night-wandering takes her smack into the bedroom of a mysterious, recently arrived count. Evaluating one Mlle. Albani, in her Dublin debut in the title role, Stoker found her singing “little short of perfection, and if we selected items for special notice we should be tempted to praise everything. She is fascinating in style, and she acts gracefully and intelligently.” If it isn’t already obvious, the name Amina is extraordinarily close in spelling and sound to Mina, the embattled heroine of Dracula, who deals with her own and others’ problems of sleepwalking, mesmerism, and the attentions of a certain elusive count.¶

Dracula suggests that vampirism results from dealings with the devil, and so may have been somewhat influenced by Stoker’s familiarity with the opera Robert le diable (1831), which combined Mephistophelian machinations with a central spectacle of the dead resurrected. Little produced since the nineteenth century, Robert was extraordinarily popular and much imitated in its time. Composer Giacomo Meyerbeer and librettists Eugène Scribe and Germain Delavigne loosely adapted a medieval legend about a young man sired by Satan and stalked by one of his emissaries into a sumptuous production that stabilized the standard conventions of grand opera as we enjoy them today.

First produced at the Paris Opéra, Robert proved a dependable, money-spinning repertory favorite throughout Europe and the Americas. Stoker thought highly enough of Meyerbeer to rank him alongside Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi, and presumably researched the Theatre Royal archives to make note of two previous Dublin productions, one five years earlier (which he may well have seen as a student) and one dating to his bedridden years as a child.# Robert borrowed elements from Goethe’s Faust nearly twenty years before Gounod’s opera and recounted the story of the title character, shadowed by a sinister companion, Bertram. The latter knows of Robert’s half-diabolical heritage and is eager to have him sign over his soul for purposes of eternal damnation. In the end, it is Bertram who faces a fiery recall to regions below.

The opera is more or less bisected by a show-stopping ballet in which white-shrouded nuns rise from their tombs for a haunting danse macabre—one of the first examples of ballet blanc, the now-familiar convention of costuming ballerinas completely in white. Degas famously commemorated the original scene, and its audience. White skirts and tutus would become a standard fixture of ballet, especially in supernaturally themed works like Les sylphides, Giselle, and Swan Lake.

Stoker called Robert le diable (performed in Italian as Roberto il diavolo) “mystic yet picturesque,” with a “crowded and attentive” first-night house. “The plot of the incidental ballet, which was a prominent feature in last night’s performance,” Stoker wrote, “is in no way inconsistent with the supernatural nature of the plot, [and] although slightly incongruous, is at least novel and ingenious.” The devilish Bertram’s entrance “was greeted with hearty plaudits. His make up in sable and flame coloured habiliments was sufficiently suggestive of the weird mentor.”

Coinciding with the beginning of his work for the Echo, Stoker made the acquaintance of an actress who required absolutely no assistance registering pain or passion—or, indeed, histrionic states of any kind—and who would become a lifelong friend and confidante. In his Personal Reminiscences Stoker describes his first exposure to the work of the American actress Genevieve Ward as having occurred at her performance of Ernest Legouvé and Eugène Scribe’s Adrienne Lecouvreur at the Theatre Royal. In reality, he had already seen her twice during her twelve-night engagement, first in Victor Hugo’s Lucrezia Borgia, then in W. G. Wills’s English adaptation of Legouvé’s Medea (advertised as Medea in Corinth).

Back from the dead: Edgar Degas’s 1871 impression of the haunting danse macabre from the Meyerbeer opera Robert le diable.

It was a rainy night in late November 1873 when Stoker took his favorite reviewer’s seat at the back of the house at the Theatre Royal—“the end seat O.P.” (meaning “opposite prompt,” referring to the prompter’s traditional position in the stage-right wings). The attendants kept the preferred seat open for him whenever possible. That night it wasn’t even necessary; attendance was disappointing, and “the few hundreds scattered about were like the plums in a foc’sle duff.”**

Stoker described Ward’s first-night audience for Lucrezia as only “cordial and appreciative,” a reception he attributed to the role itself. “The character she chose for what may be designated her debut is not one to evoke much sympathy. Of all the wicked women who in every age have wrought evil, none has been represented as exceeding the enormities attributed to Lucrezia Borgia.” And, certainly, using the sleepwalking scene from Macbeth as a curtain raiser for the play did little to make her warm and accessible. But Stoker himself had quite a different response than the other first-nighters. Ward “interested me at once,” he wrote, likening her to “a triton amongst minnows. She was very handsome; of a rich dark beauty, with clear cut classical features, black hair, and great eyes that flashed with fire. I sat in growing admiration of her powers. Though there was a trace here and there of something which I thought amateurish she was so masterful, so dominating in other ways that I could not understand it.”

He wrote in his diary, “(Mem. will be a great actress).”

Ward’s twelve nights at the Theatre Royal were heavy with female ferocity, which Stoker seemed to relish as much as her acting. After Lady Macbeth and Lucrezia Borgia came Medea. In his Echo review (like his separate notice in the Mail, it ran the following day), Stoker wrote: “It is a daring thing for a young actress to make her debut, as Medea, in a Theatre where Ristori has lately performed the same part. . . . A poor performance would appear horribly mean by contrast; and Miss Ward may well consider last night’s applause an omen of high histrionic renown.” Adelaide Ristori was a legendary Italian tragedienne, with whom Ward had trained.

From first to last runs a series of scenes of wild ungovernable passion—love like the love of Swinburne, that bites and strains, hate such as consumes no other woman of fact or fiction; this love, this hate, with rage, despair, fury, revenge, jealousy, all blaze both by turns as though the heart of the woman were but one smoldering fire which needed but a breath to fan into flame.

After the performance of Adrienne Lecouvreur, he was introduced to Ward backstage, and four nights later arranged for a more formal social introduction through the American consulate. “And then there began a close friendship that has never faltered, which has been one of the delights of my life and which will I trust remain as warm as it is now till the death of either shall cut it short.”

Many writers on Stoker have suggested a romance with Ward, perhaps because she is the only female acquaintance in Dublin, other than his mother, Lady Wilde, and the woman he would marry, for which there is any documentation. But this surmise overlooks the fact that platonic friendships between men and women have always been common in the theatre. It also brushes aside obvious general conclusions about Stoker’s sexual interests that might be drawn from his Whitman correspondence. The theatrical world has always been full of young men who idolize and fetishize older, actressy actresses, especially the divas who specialize in “strong” parts: Lady Macbeth, Lucrezia Borgia, and Medea are classic examples. At the age of thirty-six, Ward was twelve years older than Stoker, closer to his mother’s generation than his own, especially given that the age of sexual consent in Victorian Britain was twelve.

And then there is Ward herself, whose own peculiar adventures in heterosexuality, or its contrived simulacrum, paint a picture of a woman with little use for men.

Ward was the American granddaughter of a New York City mayor, Gideon Lee, and the daughter of wealthy, globetrotting parents, Col. Samuel Ward and Lucy Leigh Ward. The family maintained residences in New York, London, Paris, and Rome.

By 1873, when she met Bram, Ward’s life, on and off the stage, already had the makings of a sensation novel, or at least a feverish chamber opera. Years earlier she was, in fact, an opera singer of some note. Her mother had also been a gifted singer, with a four-octave ranged deemed “not human” by one amazed teacher, but she didn’t pursue a professional career, channeling her ambitions instead into her musically talented daughter. Genevieve’s international career was given a huge public relations boost by the tabloidesque melodrama of a star-crossed marriage at the age of nineteen to a Russian aristocrat, Count Constantine de Guerbel of Nicolaeiff, a dashing and magnetic young man said to bear a striking resemblance to Czar Nicholas I, whom he served as aide-de-camp.

What the Wards didn’t know about de Guerbel was that, according to his commanding officer in the Russian army, he “had all the vices of a full grown man, and seemed to know as much.” As an adult, he displayed the makings of a Gothic novel villain. Ward’s biographer Zadel Barnes Gustafson noted that de Guerbel’s “personal power with both men and women was something inexplicably great. He was able to embarrass and lethargize the reasoning faculties, while intensifying the emotional.”

Genevieve Ward as Lady Macbeth (top) and as Margaret D’Anjou (bottom) in Richard III.

Mesmerizing young women came easily to the count, who made an impulsive proposal of marriage in Nice, to the delight of Ward’s ambitious parents. There is no evidence of an actual romantic bond—as Jane Austen, that astute chronicler of nineteenth-century matchmaking observed, real connubial happiness “is entirely a matter of chance.”

Luck was not on Ward’s side, emotionally or practically. The couple was married in a civil ceremony, which, under Russian law, was only a formality of engagement until the union could be consecrated in a Russian church. That never happened, and the count went on to other conquests. A jilted woman in Victorian times was considered to be damaged goods, and the scandalized Wards appealed through an intermediary to the Russian emperor himself to enforce de Guerbel’s promise. Nicholas had neither the power to validate or dissolve the marriage, but he did order de Guerbel to Warsaw to complete the Russian end of the bargain and marry in a church. Ward’s furious father carried a pistol to the “gruesome” service, at which the bridegroom was reported to tremble visibly, and at which the bride wore black. When an attendant questioned Mrs. Ward about the appropriateness of her daughter’s wedding gown, she replied icily, “I consider it a funeral.”

Ward didn’t care; she had what she (or at least her mother) wanted—an aristocratic title to adorn her rising operatic career—and thereafter toured the world as “Madame de Guerbel,” the juicy backstory of her marriage being an essential part of her press kit. Afterward she affected a studied indifference to men. She claimed, for instance, to have received eleven proposals of marriage in the wake of the de Guerbel affair, and sadistically toyed with insistent suitors, assigning them numbers, in the manner of a butcher shop, which they were expected to recite when or if they returned for additional humiliation.

When de Guerbel finally died a miserable death, being widely known as the widow of a syphilitic rake hardly made for good box office. Ward’s stage name was modified to “Madame Guerrabella,” which her mother claimed in interviews was Italian for “beautiful war,” though it was her own coinage. Nonetheless, she meant it as a poignant reference to Genevieve’s battle for her marital honor, a saga that now somehow involved an unnamed recreant husband and the Greek Orthodox Church. Fact-checking in Victorian entertainment journalism was decidedly relaxed, even by today’s slippery standards.

The next improbable (but this time true) melodramatic juncture in Madame de Guerbel/Guerrabella’s singing career was its abrupt conclusion through a fateful bout with diphtheria contracted during an engagement in Cuba in late 1872. Her singing voice was ruined. Not to be undone, she immediately took acting lessons from Adelaide Ristori and re-rechristened herself Genevieve Ward. She had been acting under her own name, to somewhat spotty audiences but increasing critical notice, for less than a year when she met Stoker.

In his review of Ward’s Medea, Stoker had written, “None but genius of the highest class can touch or attempt ‘Medea’ without failing. The play is a touchstone; and the hush of silence, the shudder of sympathetic fear, and silence, the enthusiastic bursts of applause, that matched the progress of the piece, leave no doubt of the fact that not here alone, Miss Ward’s reputation as the first tragedienne, the successor of Miss Cushman, is made.”

“Miss Cushman” was Charlotte Cushman (1816–76), the leading American actress of her day. “She was a grand woman in every way—a fine, intellectual, big-hearted creature, a great tragic actress—and America may be proud of her,” wrote Ward. “She had not much regular teaching—her genius was innate. She was generous to her fellow actresses, and to me especially; in fact she told a very dear friend of mine that her mantle had fallen on my shoulders. It was the highest and most stimulating praise I ever received.”

Ward’s biographer Richard Whiteing noted the “strange similarity, not so much, if at all, in the genius of the two players as in the mere circumstances of their lives. Both began as singers, both came to grief by trying to do too much with their voices, with the result of incurable overstrain.” Cushman’s musical career was derailed not by illness, like Ward’s, but by bad notices. For both women, losing one’s singing voice to artistic overdedication was a more palatable public relations story. They shared a taste for rarified sensibilities and bohemian personalities far beyond American shores.

“Both felt the tremendous allurement of Europe,” wrote Whiteing. “There was a certain identity in their taste for pieces.” Each actress had interpreted Lady Macbeth to acclaim, Cushman’s especially fearsome portrayal declaimed opposite several prominent actors. (One can only wonder at the shudders later provoked in those who remembered her playing the role opposite John Wilkes Booth as the bloody thane. Two years later Booth followed the dagger of his own mind, straight into Ford’s Theatre.) According to Whiteing, both Cushman and Ward “won their way quite as much by character as by genius—that is, by the determination to succeed. Both had the same passion for the stage even in later life. These sympathies naturally brought them together as friends, and the older woman always spoke with generous confidence of the younger’s career.”

Cushman was also a surprisingly open lesbian, who, much like Walt Whitman, successfully walked a tricky same-sex tightrope throughout her career. Whitman, in fact, was a great admirer; as a newspaperman he declared that “Charlotte Cushman is probably the greatest performer on the stage in any hemisphere.” Audiences were especially fascinated by her highly convincing “breeches” roles, including Romeo, Hamlet, and Orlando in As You Like It (an all-female production), and chose to largely ignore the in-your-face implications of the lifelong lack of a Mr. Cushman and the omnipresence of close female friends. Even when these relationships became publicly tempestuous, the public chalked things up to artistic temperament.

Charlotte Cushman as Romeo.

Like Le Fanu’s Carmilla—never explcitly identified as lesbian—Cushman maneuvered out in the open and under the radar. Unlike sex between men, lesbian relations had never been criminalized, or even acknowledged as “real” sex. How could they be, with no male member involved? Or, to rephrase Stoker’s vampire hunter Abraham Van Helsing, the strength of the nineteenth-century lesbian was that people would not believe in her.

Although she lived until 1922, Ward never made a film or recording. The “bottled orations” of the phonograph, she wrote, seemed “to come from the bowels of the earth, as from gnomes in torture.” But her legacy and technique lived on and can still be observed in the recorded work of younger actresses she encouraged and mentored, like Martita Hunt, another “strong” actress never married or linked romantically to men, and a specialist in eccentric roles like Miss Havisham in David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946), and—of special interest to Stoker connoisseurs—the baroness turned into a vampire by her son in the Freudian-flavored campfest The Brides of Dracula (1960).

Ward socialized in Dublin with the likes of Jane Wilde and Edward Dowden and, when away from the Irish capital, carried on a friendly correspondence with Stoker, but the fact that she began her letters “Dear Mr. Stoker” is more evidence their relationship was not what some would like it to have been. In the summer of 1874 Stoker visited Ward and her mother in Paris, planning to meet his parents in Switzerland afterward, but the City of Light proved to be of much greater interest, and he snubbed them. Charlotte wrote to him afterward, in Dublin, expressing regret that he didn’t visit. But the City of Light had much that might delay his departure, and theatrical Paris must have been a revelation. The Comédie-Française was, once more, the professional home of Sarah Bernhardt, and in 1874 she played Racine’s Phèdre. The Comédie’s director was Émile Perrin, lately of the Paris Opera, who had introduced subscription tickets to attract well-heeled and well-behaved Parisian audiences. There were no Dublin-style donnybrooks in the aisles.

Genevieve Ward’s protegée Martita Hunt was memorable as the vampire baroness in The Brides of Dracula (1960).

Stoker returned to France in 1875 and 1876 and was impressed by aspects of Paris far apart from its stages. During these trips he took notes for one of his most memorable short stories, “The Burial of the Rats” (published in serial installments in 1896, and only posthumously as an intact text, in 1914). In a vast dust heap at the city’s periphery, a first-person protagonist is stalked by a predatory band of rag pickers. The title is creepily misdirecting: it is not rats that are buried, we learn, but rather the human corpses they strip to the bone that are figuratively interred—in their digestive tracts. As one of the dust-heap denizens explains, “He died last night. You won’t find much of him. The burial of the rats is quick!”

The story includes a particularly unsettling sustained metaphor of invertebrate feeding that must have come from Stoker’s study of Parisian maps and plans of the city’s radiating streets, rails, and sewers. In the highly centralized city, he saw “many long arms with innumerable tentaculae, and in the center rises a gigantic head with a comprehensive brain and keen eyes to look on every side and ears sensitive to hear—and a voracious mouth to swallow.” The hunger of this metropolis was highly irregular:

Other cities resemble all the birds and beasts and fishes whose appetites and digestions are normal. Paris alone is the analogical apotheosis of the octopus. Product of centralisation carried to an ad absurdum, it fairly represents the devil fish,†† and in no respects is the resemblance more curious than in the similarity of the digestive apparatus.

Stoker had hopes of becoming a playwright, and Ward encouraged him in the writing of a play based on the life of Madame Roland, a leading figure in the French Revolution. Stoker wrote to his father that he was writing the play for a “Miss Henry,” who has never been further identified. Some have speculated (or hoped for) a romance, but it is far more reasonable to assume that Miss Henry was simply a protégée of Miss Ward.‡‡ Nothing came of Stoker’s Madame Roland play—no script or notes have ever been discovered—but the possibility of writing for the stage stuck with him. In his journal he jotted a note that Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” might be a good basis for an opera, and his instinct was astute. Stoker never developed it himself, but Claude Debussy would partially finish a libretto and score for La chute de la maison Usher between 1908 and 1917; Philip Glass would complete his own version in 1987.

Work for the stage was collaborative and contingent upon many variables and vagaries. For Stoker, fiction was a much more manageable creative outlet, and he had been working steadily at the craft since the publication of his first two short stories. In early 1875, The Primrose Path, a novella by “A. Stoker, Esq.,” was serialized in five issues of the Dublin magazine The Shamrock. The successive and cumulative improvement in Stoker’s narrative skills from “The Crystal Cup” to “Saved by a Ghost” to The Primrose Path suggests a sudden eruption of honed craftsmanship that is probably misleading. We don’t know how closely one composition followed upon the other. “The Crystal Cup” may well have been a very early piece of juvenilia. “Saved by a Ghost” appeared only after he had more than a year of grueling journalism under his belt, an experience sure to improve any kind of writing. Clive Leatherdale, Stoker’s most prolific modern editor, notes that young Bram may have been “hardened to rejection,” submitting an untold number of stories to Dublin and London periodicals in the early 1870s. “It is a safe bet,” Leatherdale writes, “that many of Stoker’s early works languished in drawers, never to be published.” In structure, dialogue, and characterization, The Primrose Path resembles stage melodrama, to which Stoker had regular exposure during his years as a critic.

It also reflects an extraordinary ambivalence about the theatre, which could only have come from Stoker’s own struggle to balance practicality and stability with the powerful pull of his heart’s desire. The protagonist, Jerry O’Sullivan, is a Dublin carpenter struggling to support his wife, Katey, and their baby daughter. He receives an offer of employment from a theatre in London, which revives “a strange longing to share in the unknown life of the dramatic world,” a realm as alluring and esoteric as “the mysteries of Isis to a Neophyte.”

Moth-like he had buzzed around the footlights as a boy, and had never lost the slight romantic feeling which such buzzing ever inspires. Once or twice his professional work had brought him within the magic precincts where the stage-manager is king, and there the weirdness of the place, with its myriad cords and chains, and traps, and scenes, and flies, had more than ever enchanted him.