Henry Irving as Mephistopheles in Faust (1886). Illustration by Bernard Partridge.

Henry Irving as Mephistopheles in Faust (1886). Illustration by Bernard Partridge.

’TIS THE EYE OF CHILDHOOD THAT FEARS A PAINTED DEVIL.

— Lady Macbeth

One night in the 1880s—or so a story goes—during an otherwise uneventful evening at the Lyceum Theatre, a couple sitting in the dress circle glanced down into the stalls and were startled to see an elderly woman holding in her lap a man’s grinning, severed head.

Alarming though the sight was, the couple chose not to cause a scene, or even quietly alert theatre personnel to summon the police. Instead, with all the British reserve and self-reliance and restraint they could muster, they waited until the intermission to venture downstairs and investigate for themselves. Alas, both the lady and the head that had glared up at them had disappeared. It is a shame they didn’t inform Bram Stoker, always on duty during performances to handle such exigencies. The paranormal nature of the incident surely would have interested him, though whether he could have actually apprehended the spectral vision is another matter. It would, however, have been another colorful anecdote to add to his bottomless hoard of stories about the Lyceum’s unstopping parade of eccentric personalities, droll production mishaps, near-fatal accidents, and visiting dignitaries almost wandering out onstage during performances. (The clueless Chinese ambassador in flowing yellow robes who very nearly interrupted Hamlet and Ophelia’s “Get thee to a nunnery” scene may be the best of all.)*

In fact, Stoker biography and commentary is often swamped and deflected by the sheer volume of Lyceum lore. Stoker himself emerges from history as a barely glimpsed spectre, lurking in Irving’s shadow. Until the mid-1880s, little of Irving’s work sparked Stoker’s own creativity, and just dealing with Irving’s output was a constant impediment to his writing. But now, supernatural happenings at the Lyceum—if only on the stage and not in the stalls—were becoming more frequent, and giving Stoker ideas. Previously, subjects like ghosts and mesmerism had been confined to Hamlet and The Bells. Irving, at the age of forty-seven, dropped the prince of Denmark (along with his revenant father) from the Lyceum repertoire in the spring of 1885. But it was quickly replaced with even more saturnine characterizations—Mephistopheles in Faust (1885) and the title role in Macbeth (1887) opposite Ellen Terry. These productions powerfully intersected with Stoker’s early passion for the Christmas pantomimes, works that turned and soared on fearful fantasy and wondrous spectacle, and both Faust and Macbeth would be dramatically reflected and refracted in Dracula.

Bram Stoker and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe both discovered Mephistopheles innocently, in the entertainments of childhood. Stoker first encountered the character as the omnipresent Demon King of pantomimes around the age of eight; Goethe’s introduction came at the age of four at a traveling puppet-show rendition of the medieval Faust legend, about an alchemist who unwisely sells his soul to the devil for knowledge and power. The prince of darkness would preoccupy each author, in his own way, for the rest of his life and figure prominently in both writers’ masterworks. Goethe began work on his verse drama in 1773 and published the first part of Faust in 1808 and the second near the end of his life, in 1832. The towering meditation on man’s quest for knowledge and the nature of good and evil is an achievement so massive that it has only rarely been staged. Faust gained a much-amplified cultural currency through operatic adaptations, especially Charles Gounod’s opera Faust (1859) and Hector Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust (first performed in 1846, though not successfully or regularly until 1877). The dramatic adaptation by W. G. Wills, produced by Henry Irving in 1885, would be the Lyceum’s greatest commercial success and have an outsized impact on Stoker’s imagination vis-à-vis all things diabolical, and is therefore an important key to Dracula’s meaning and importance.

W. G. Wills was the West End’s lucky penny, a reliable source of successful if often formulaic historical plays and adaptations for himself and others since the Bateman years, including Charles I (1872) and Eugene Aram (1878). Olivia (1878) was the dramatization of The Vicar of Wakefield that had originally showcased Ellen Terry and brought him to Irving’s attention; the Lyceum’s 1883 revival would star both Irving and Terry and have an especially successful run. Only Wills’s Vanderdecken (1878) had been a fizzle, but the actor liked the spooky leading role (Stoker, of course, adored it) and hadn’t given up on another possible dramatization of the Flying Dutchman story. The Lyceum coffers were fairly flush after the first few seasons, and Irving paid Wills the handsome sum of £600 to write Mephisto, based on the first part of Goethe’s Faust and tailoring the part of Mephistopheles to Irving’s most sardonic and saturnine side. Purists would shudder at the kind of wholesale cuts the German masterpiece would endure, including the elimination of Goethe’s sixty-page prologue and its monumental debate between Mephistopheles and God. There were no waltzes by Gounod to set audiences humming, and Wills’s blank verse was pedestrian indeed compared to the complicated German rhyme scheme of the original and the ambitious 1835 English verse translation of John Anster, which could have been freely adapted, but wasn’t.

But, as the actor’s grandson observed, “Irving’s intuition as a showman had not failed him. Although the inadequacy of the text was plain to all, although Irving’s most ardent admirers admitted that his demon teetered dangerously on the edge of pantomime, and although the whole affair offended the genuine and professed students of Goethe, this consummate confection of villainy and piety, of beauty and fearsome hideousness, of claptrap and culture, was the greatest financial success Irving ever had. For many years it was a seemingly inexhaustible source of wealth which subsidized his other more admirable but less rewarding ventures.”

As Stoker related, “When Irving was about to do the play he made a trip to Nuremberg to see for himself what would be most picturesque as well as suitable.” It’s not at all clear that a research dig was even necessary. A single photographer on assignment could have provided more than enough scenic and architectural references. Instead, Irving, Terry, Stoker, Loveday, and scenic designer Hawes Craven embarked on what was much less a business trip than a holiday junket, one that afforded Irving and Terry a relatively private vacation in Bavaria, far from prying eyes and gossiping tongues. Although Prime Minister William Gladstone had wanted to give Irving a knighthood in 1883, advisers cautioned him that it might be inadvisable, given scandalous whisperings about Irving’s ambiguous relationship with his leading lady. Irving preferred to say he had declined the honor out of modesty, rather than propriety.

However much or little the trip to Germany informed Faust, it definitely inspired one of Stoker’s most chilling short stories, “The Squaw” (1893), in which a young English couple on their honeymoon—possibly fictional stand-ins for Bram and Florence on the honeymoon they never had—stumble upon an old German torture chamber, now a tourist attraction, where an obnoxious, talkative, pistol-packing American named Elias P. Hutcheson relates a story about the grisly revenge taken by a Native American woman for the abduction and murder of her child. The foreshadowing is more than a bit over-obvious as Hutcheson accidentally drops a rock on the head of a frolicking kitten, smashing out its brains. The kitten’s mother flies into a demoniacal rage and pursues the tourists into the torture exhibition, where the American insists on being bound inside the “Nurnberg Virgin,” the notorious spiked sarcophagus more famously known as an Iron Maiden, its heavy lid lined with deadly spikes. As the exhibit’s custodian slowly lowers the lid toward the morbidly delighted thrill-seeker, the mother cat reappears and hurls herself not at Hutcheson but at the custodian, clawing his face and causing him to drop the rope. “And then the spikes did their work,” Stoker’s first-person narrator tells us. “Happily the end was quick, for when I wrenched open the door they had pierced so deep that they had locked in the bones of the skull which they had crushed, and actually tore him—it—out of his iron prison till, bound as he was, he fell at full length with a sickly thud upon the floor, the face turning up as he fell.” The cat takes her place on the dead American’s head, lapping the blood that wells from the emptied eye sockets. “I think no one will call me cruel,” the narrator tells us, “because I seized one of the executioner’s swords and shore her in two as she sat.”

Set rendering of German village for Irving’s Faust.

Bavaria is also home to Munich, a reasonable place for additional exploration on a research holiday. For Stoker, a side trip may have uncovered additional horrors to fuel his fiction. His preliminary notes for Dracula make reference to the notorious Munich “Dead House,” a municipal morgue to which, partly for sanitary reasons but also as a gruesome kind of entertainment, all the city’s dead, rich and poor, from infants to the aged, were taken for voyeuristic public viewing, as well as to be monitored, via electrical wires attached to a ring on each corpse’s finger, for any sign of life that may have been missed. The terror of premature burial was still alive and well forty years after Edgar Allan Poe raised the alarm on a peculiar and stubbornly persistent nineteenth-century phobia.† As described by the American Magazine in 1892, the Deadhouse (as the periodical spelled it) was “a spectacle sufficiently ghastly to cause any foreigner to grow faint. It is an awful and repulsive sight.”

On each side of the rectangular room is arranged a row of slightly inclined biers, on which rest the yellow-covered coffins containing all that is mortal of from twenty to forty human beings. The faces of the emaciated old women with their sharp, cronelike chins and sunken eyes, their open mouths disclosing one or two discolored teeth, are enough to sicken most spectators at a glance. Indeed, the Müncheners regard going to the Deadhouse on holidays as a standard recreation, and always recommend it to visitors with a weird sort of pride.

In his undated Dracula notes, Stoker has his protagonist, Jonathan Harker, visit both Munich and its morgue: “Sees old man on bier, describe—then to babies—then hears talk & listens—man went to fix corpse—place taken—returned on inquiry & find corpse gone—Harker has seen the corpse but does not take part in discussion.” The corpse, of course, is the Count himself, who has found the perfect place to hide in plain sight as he makes longer and bolder exploratory trips from Transylvania in anticipation of his triumphant relocation to England. The incident does not appear in the finished book, but a deleted line later in the Dracula typescript—“and he thought now the Man of the Munich Dead House and Count Dracula were one”—is clear evidence that the morgue episode was part of an major excision early in the book, only a hint of which survives in Stoker’s posthumously published short story “Dracula’s Guest” (1914).

The Faustian theme in Dracula emerges when Van Helsing informs his fellow vampire hunters that the Dracula family “had dealings with the Evil One. They learned his secrets in the Scholomance, amongst the mountains over Lake Hermanstadt, where the devil claims the tenth scholar as his due.” Why the nine other students got a free education in evil isn’t explained, but the arrangement is described in greater detail in Emily Gerard’s article “Transylvanian Superstitions” (1885), a primary reference for Stoker. According to Gerard, the Scholomance is a “school supposed to exist somewhere in the heart of the mountains, and where all the secrets of nature, the language of animals, and all imaginable magic spells and charms are taught by the devil in person. Only ten scholars are admitted at a time, and when the course of learning has expired and nine of them are released to return to their homes, the tenth scholar is detained by the devil as payment, and mounted upon an Ismeju (dragon) he becomes henceforward the devil’s aide-de-camp, and assists him in ‘making the weather.’ That is to say, preparing the thunderbolts.” The name Dracula derives from drac, or dragon, and Stoker dramatized the vampire’s power to drive storms in the Tempest-like manner by which he shipwrecks himself in Whitby Harbor.

A moment more derivative of the Wills Faust can be found in Stoker’s final Dracula typescript, though not in the finished book. During the notorious scene in which Van Helsing and Seward, bearing crucifixes, barge in on the bloody ménage à trois between Dracula, Mina, and Jonathan, Stoker deleted Seward’s line “Even then at that awful moment with such a tragedy before my eyes, the figure of Mephistopheles in the Opera cowering before Margaret’s lifted cross swam up before me and for an instant I wondered if I were mad.” Here, despite the opera reference, Stoker is referring not to Gounod’s Faust but to the Wills version, wherein Margaret (Marguerite in Gounod) is menaced by Mephistopheles while at her spinning wheel:

MAR. [Aside. Stopping her spinning].

Sooth, this man is an enemy to God,

With every shuddering instinct I can feel it.

MEPHIS. But if you disobey my counsels, maiden,

And talk of the redemption, faith, and prayer,

Your happiness will turn to must and blight:

Despair, disgrace, and ruin will o’ertake you,

Then, should you turn for help—

[MEPHIS. Sees her cross, his eyes fix on it, and he half-rises to move away.]

MAR. [Observing, starts up]

If you are evil, and God’s enemy,

Then let this holy symbol drive thee hence.

[She stands up, and lifts cross. He cowers away out of the door, looking devilishly, behind.]

When Faust enters, Margaret informs him of what the audience already knows about the crucifix’s power.

MAR. Part from that man—that demon—part from him.

Before you came he sat there by my side,

I felt like a poor bird before a snake,

But when I lifted up this sacred cross,

He shrank away, unmasked, and horrible.

He is a devil, and God’s enemy!

Prior to Dracula, there were many folkloric testimonials to the power of religious objects against evil, but the specific image of a crucifix held aloft to stop the approach of evil was not a set piece in vampire fiction until Stoker, and the place it came from was Irving’s Faust. Both the cross and holy water—each also effectively employed by Van Helsing in Dracula, along with the communion wafer—are referenced in the dramatic clash at the end of act 2, when Mephistopheles forbids Faust from seeing Margaret again.

FAUST. By what pretence canst thou forbid me, fiend?

MEPHIS. Thou answer’st me

As if I were some credulous, dull mate.

I am a spirit, and I know thy thought.

You think you may be fenced round by-and-by

With sprinkled holy water, lifted cross—

While you and your pale saint might hold a siege

Against the scapegoat—’gainst the devil here.

Ere that should be I’d tear thee limb from limb,

Thy blood I’d dash upon the wind like rain,

And all the gobbets of thy mangled flesh

I’d scatter to the dogs, that none should say

This carrion once was Faust!

Yon cottage would I snatch up in a whirlwind,

At dead midnight, like a pebble in a sling,

And hurl it leagues away, a crumbled mass,

With its crushed quivering tenant under it.

Dost know me now?

FAUST. Fiend, I obey.

MEPHIS. When hell’s aroused in me, beware!

Although Ellen Terry admitted she “never cared much for Henry’s Mephistopheles, a twopence colored part, anyway,” she did single out the ultimatum given to Faust as a particularly hair-raising moment. On the booming declaration “I am a spirit,” she recalled, “Henry looked to grow a gigantic height—to hover over the ground instead of walking on it. It was terrifying.”

To one degree or another Irving was always playing some version of himself, so it isn’t surprising that another celebrated role could be discerned around the edges of Mephistopheles’s aura. Wills could only have had Irving’s Hamlet in mind during the scene in Faust’s study where he peers at an iconic prop from under his long-plumed, princely hat. But unlike Hamlet, Irving’s devil doesn’t waste time brooding over the mysteries of mortality.

FAUST . . . See here this skull—

Canst thou set eyes within these hollow sockets,

Give it a tongue to tell its earthy secret?

MEPHIS. [taking skull] Who knows? I might,

If these two jaws could wag again to words.

There is no secret worth the telling. Merely

’Twould say—“Doctor, I’m dead and damned.”

Although Wills considered the Anster translation so fine as to be “unapproachable,” and claimed to have worked directly from Goethe’s original text with the aid of a German dictionary, he had no qualms about lifting rhymes verbatim from Anster when it suited him, and blank verse be damned, as when Mephistopheles summons vermin to eat away the edge of a chalked pentagram in which he is trapped:

MEPHIS. The lord of the frogs and the mice and the rats,

Of the fleas and the flies and the bugs and the bats,

Commands you with your sharp tooth’s saw

The threshold of this door to gnaw.

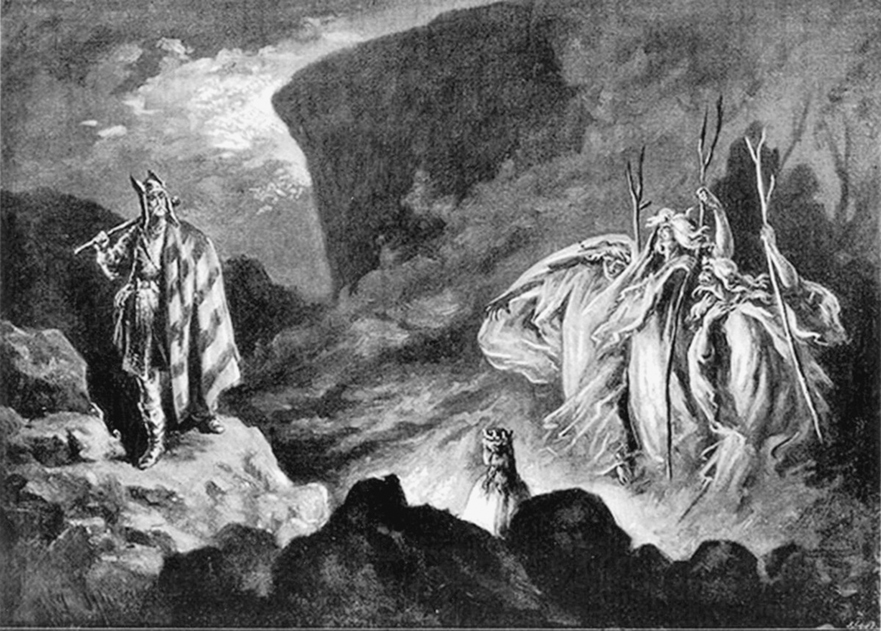

Stoker never gave an opinion for the record on the quality of Wills’s script, but his handwritten corrections appear all through a printer’s proof of the play, which was subsequently published and may also have been used in printed form by the Lyceum company, which, for Faust, included hundreds of technicians and extras in addition to twenty-three speaking parts. Hand-copying scripts for all who needed them would have been a daunting task, but Irving had the money available for typesetting. It’s impossible to know whether Stoker had actual creative input or was recording changes requested by Irving and/or Wills. The latter makes more sense. Since he claimed to have helped Irving improve Vanderdecken, surely he would have tried to snare some credit for Faust, but he never did. The most substantial material in Stoker’s hand is a revision of the Brocken scene opening, deleting Mephistopheles’s lines to Faust as they climb to the summit: “Dost thou not wish you had a broomstick, friend? / I wish I had a tough he-goat to ride! / Hark! to the crashing woods! / The affrighted owls are on the wing; / Oohoo! Shoohoo! Oohoo! Shoohoo! / Cling to my cloak—fear nothing.” Stoker begins the scene with “Grasp my shirt and fear nothing,” allowing the flying witches and owls to speak for themselves.

Ellen Terry as Margaret in Faust.

Whatever editing he may or may not have contributed, Stoker worried justifiably about the production’s viability. “I began to have certain grave doubts as to whether we were justified in the extravagant hopes which we had all formed of its success,” he wrote. “The piece as produced was a vast and costly undertaking; and as both the decor and the massing and acting grew, there came that time, perhaps inevitable in all such undertakings of indeterminate bounds, as to whether reality would justify imagination.” His doubts were only deepened after a partial dress rehearsal that ran long into the night. “It was then, as ever afterwards, a wonderful scene of imagination, of grouping, of lighting, of action, and all the rush and whirl and triumphant cataclysm of unfettered demoniacal possession. But it all looked cold and unreal—that is, unreal to what it professed.” By the time the devilish revels ended, the gray morning was breaking (rather appropriately, given the scene just rehearsed). “I talked with Irving in his dressing-room, where we had a sandwich and something else, before going home. I expressed my feeling that we ought not to build too much on this one play. After all it might not catch on with the public as firmly as we had all along expected—almost taken for granted. Could we not be quietly getting something else ready, so that in case it did not turn out all that which our fancy painted we should be able to retrieve ourselves. Other such arguments of judicious theatrical management I used earnestly.”

After weighing Stoker’s points, Irving was not swayed. “That is all true,” he said, “but in this case I have no doubt. I know the play will do. To-night I think you have not been able to judge accurately. You are forming an opinion largely from the effect of the Brocken. As far as to-night goes you are quite right; but you have not seen my dress. I do not want to wear it till I get all the rest correct. Then you will see. I have studiously kept as yet all the colour to that grey-green. When my dress of flaming scarlet appears amongst it—and remember that the colour will be intensified by that very light—it will bring the whole picture together in a way you cannot dream of. Indeed I can hardly realise it myself yet, though I know it will be right. You shall see too how Ellen Terry’s white dress and even that red scarf across her throat will stand out in the midst of that turmoil of lightning!”‡

Poster for the original production of Irving’s Faust.

To others, Irving would bemoan the fact that, being caught up in the middle of it, he would never personally be able to witness the finished effect. His vanity was such that he never even considered the eminently practical solution of simply having a costumed stand-in demonstrate the spectacular stage picture. Company members recalled Irving as more than usually autocratic, impatient, and demanding during the play’s preparation. Alice Comyns Carr, wife of the critic, playwright, and gallery owner J. Comyns Carr, was an author in her own right, as well as a costume consultant, who had traveled with the company on the German research trip. Now, with Faust in rehearsal, she was appalled at the Jekyll-and-Hyde transformation that had overtaken him. “Gone was the debonair, cheery, holiday companion,” she remembered, “and in his place was a ruthless autocrat, who brooked no interference from anyone, and was more than a little rough in his handling of everyone in the theatre.” The roughness included the actual hitting and slapping of other actors.

Irving had intended to unveil Faust early in the season, in September instead of around Christmas (which might have deflected at least some of the inevitable pantomime comparisons), but the physical production was on a scale the Lyceum had never attempted. “Many of the effects were experimental and had to be tested; and all this caused delay,” wrote Stoker. “As an instance of how scientific progress can be marked even on the stage, the use of electricity might be given.” Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience had been the first stage production entirely lit with electricity, but Irving still relied primarily on gas and limelight, saving electricity for lightning and other special effects. Like Nikola Tesla, that supreme showman of the early electrical age, he understood the value of exploiting electricity for its theatrical rather than utilitarian qualities.

The sword fight between Faust and Valentine (Marguerite’s brother, outraged after Faust impregnates her) employed an “invisible” Mephistopheles as a third participant. A century before the dawn of lightsabers, Irving’s Faust startled audiences (and at times the actors) with electrified swords that threw off blue sparks when they touched. “This effect was arranged by Colonel Gouraud, Edison’s partner, who kindly interested himself in the matter,” Stoker remembered. “Two iron plates were screwed upon the stage at a given distance so that at the time of fighting each of the swordsmen would have his right boot on one of the plates, which represented an end of the interrupted current. A wire was passed up the clothing of each from the shoe to the outside of the indiarubber glove, in the palm of which was a piece of steel. Thus when each held his sword a flash came whenever the swords crossed.” A certain number of shocks to the actors were unavoidable, but when they happened Irving would just ad lib a delighted cackle.

In addition to the sparks, there was a startling variety of sudden blue flames that erupted periodically throughout the show, and which Stoker surely remembered when he sent Dracula looking for treasure-heralding blue fire during a coach stop in the Borgo Pass—fire that rendered him transparent when he walked in front of it. “The arrangement of the fire which burst from the table and from the ground at command of Mephistopheles required very careful arrangement so as to ensure accuracy at each repetition and be at the same time free from the possibility of danger,” Stoker noted. “Altogether the effects of light and flame in Faust are of necessity somewhat startling and require the greatest care. . . . The methods of producing flame of such rapidity of growth and exhaustion as to render it safe to use are well known to property masters. By powdered resin, properly and carefully used, or by lycopodium§ great effects can be achieved.”

The Witches’ Kitchen scene from Faust (1886).

Beyond pyrotechnics, Stoker noted that “steam and mist are elements of the weird and supernatural effects of an eerie play.” In the 1880s, dry ice and chemical fog had not yet been developed for stage effects, but there was still a trusty standby. “Steam can be produced in any quantity, given the proper appliance,” Stoker wrote. “But these need care and attention, and on a stage, and below and above it, space is so limited that it is necessary to keep the tally of hands as low as possible. . . . Inspecting authorities have become extra careful with regard to such appliances; nowadays they require that even the steam kettle be kept outside the curtilage¶ of the building.” Steam also had the drawback of making noise as it was produced, but except for the less than satisfactory use of scrims and dim lighting, fogs were otherwise impossible to reproduce, or even indicate. There was a certain kind of hissing in the theatre Irving would simply have to endure.

Fortified with a battery of stage tricks unparalleled outside of pantomime, Faust premiered on December 19, 1885, with every seat taken; the Prince and Princess of Wales were among the first-nighters. According to Stoker’s meticulous record keeping, between 1885 and 1902, the play “was performed in London five hundred and seventy-seven times; in the provinces one hundred and twenty-eight times; and in America eighty-seven times. In all seven hundred and ninety-two times, to a total amount of receipts of over a quarter of a million pounds sterling.”

Such impressive statistics meant little to critical observers like the British-American writer Henry James, who was already predisposed not to like Wills’s work. In 1878, he had written that the popularity of Olivia “could only be accounted for by an extraordinary apathy of taste on the part of the public, and a good-natured disposition in the well-fed British playgoer who sits in the stalls after dinner to accept a pretty collection of eighteenth-century chairs, buffets, and pottery . . . as a substitute for dramatic composition and finished acting.” As for Faust, he found it baffling that, to Henry Irving, so many of the play’s essential aspects simply “wouldn’t matter.”

It wouldn’t matter that Mr Wills should have turned him out an arrangement of Goethe so meagre, so common, so trivial (one must really multiply epithets to express its inadequacy), that the responsibility of the impresario to the poet increased tenfold, rather than diminished. . . . It wouldn’t matter that from the beginning to the end of the play, thanks to Mr Wills’s ingenious dissimulation of the fact, it might never occur to the auditor that he was listening to one of the greatest productions of the human mind. It wouldn’t matter that Mr Irving should have conceived and should execute his own part in it the spirit of a somewhat refined extravaganza; a manner which should differ only in degree from that of the star of a Christmas burlesque—without breadth, without depth, with little tittering effects of low comedy.

James thought it best to “confess frankly that we attach the most limited importance to the little mechanical artifices with which Mr. Irving has sought to enliven Faust.”

We care nothing for the spurting flames which play so large a part, nor for the importunate limelight which is perpetually projected upon somebody or something. It is not for these things that we go to see the great Goethe, or even (for we must, after all, allow for inevitable dilutions) the less celebrated Mr Wills. We even protest against the abuse of the said limelight effect: it is always descending on some one or another, apropos of everything and of nothing; it is disturbing and vulgarizing. That blue vapors should attend upon the steps of Mephistopheles is a very poor substitute for giving us a moral shudder.

At times, though, James was willing to admit—however grudgingly—that Irving did manage to achieve a few “deep notes.”

The actor, of course, at moments presents to the eye a remarkably sinister figure. He strikes us, however, as superficial—a terrible fault for an archfiend—and his grotesqueness strikes us as cheap. We attach also but the slenderest importance to the scene of the Witches’ Sabbath, which has been reduced to a mere hubbub of capering, screeching, and banging, irradiated by the irrepressible blue fire, and without the smallest articulation of Goethe’s text. The scenic effect is the ugliest we have ever contemplated, and its ugliness is not paid for by its having a meaning for our ears. It is a horror cheaply conceived, and executed with more zeal than discretion.

James’s thoughts on Faust’s leading lady were more gently put, though just barely. “It seems almost ungracious to say of an actress usually so pleasing as Miss Terry that she falls below her occasion, but it is impossible for us to consider her Margaret as a finished creation. Besides having a strange amateurishness of form (for the work of an actress who has had Miss Terry’s years of practice), it is, to our sense, wanting in fineness of conception, wanting in sweetness and quietness, wanting in taste.”

It may have been James’s review, and many similar harsh appraisals, that prompted Irving to take the unusual step of defending his Faust publicly at a meeting of the Goethe Society at the Madison Square Theatre on March 15, 1888, and in populist terms that no doubt scandalized many Germanists in attendance. “Goethe endeavored to give practical life to an ideal which still haunts many earnest minds—the ideal which places the functions of the stage entirely beyond and above the taste of the public. That,” Irving insisted, “is impossible.” In the actor’s view, Goethe erroneously dismissed the popular desire for amusement as “degrading,” and therefore his conception for staging Faust, Part I was a completely misguided attempt to elevate ordinary human passions

into a rarefied region of transcendental emotion; and the actors, who naturally found some difficulty soaring into this atmosphere, he drilled by the simple process of making them recite with their faces to the audience, without the least attempt to impersonate any character. His theory, in a word, was that the stage should be literary and not dramatic, and that it should hold up the mirror, not up to nature, but to an assemblage of noble abstractions. It is needless to say that this ideal was predoomed to failure.

Irving insisted “that there is a great popular demand for a kind of entertainment which would have excited Goethe’s disgust, and which does not appeal very strongly to your sensibilities or to mine.” Stoker’s very probable hand in writing this speech is evidenced by a digressive defense of popular fiction, in which Stoker had a far stronger interest than Irving.

You sometimes hear to-day that the popularity of entertainments which are not of the highest class is evidence of the incurable frivolity, or coarseness, or ignorance of the vast mass of playgoers. I always wonder why the argument is applied only to the stage. You never hear any pulpit orator denounce the enormous sale of fiction which appeals to the ineradicable taste for exciting narrative. . . . No rational being believes that imaginative literature is hopelessly degenerate because the best novels are not as widely read as their inferiors.

Irving’s impersonation of Mephistopheles brought the devil down to earth and made him accessible in a way Goethe simply didn’t. “He is with out the traditional horns and tail; and cloven feet. . . . He is not the Satan of Milton, but a ‘waggish knave.’ He represents not the grandeur of revolt against the light, but everything that is gross, mean and contemptible. He delights not in great enterprise but in perpetual mischief. Sneering, prying, impish, he is the heartless skeptic of modern civilization, not the demon of medieval superstition.”

Members of the Goethe Society might have easily retorted that Irving was playing Mephistopheles to his audience as much as to his Faust, tempting them with a crude approximation of high culture and laughing as they congratulated themselves on their sense of being elevated. If Irving’s devil sneered, some of the sneers were directed at audience members themselves. He didn’t claim their souls, but at least he collected their money, and in a crass bourgeois sense, perhaps it was the same thing. However, on a completely different level, the enormous popularity of Faust in England and America spoke to its spectacular, if kitschy, reaffirmation of God, the devil, and the possibility of an afterlife in the face of the nineteenth century’s materialist juggernaut. Spiritualism attracted followers for similar reasons. And so, of course, would Dracula.

As Stoker attested, Irving never forgot a slight—or a hiss—and many of his critics were canny in their perception that he might be treating his audiences badly with Faust, if not with outright contempt then at least with some level of condescension. He had keenly felt the sting of audience disapproval while learning his trade in the provinces, and never really trusted the public. His grand goal of raising the standards of British audiences also amounted to withering judgment on the taste and intelligence of those audiences. Irving’s inability to let go of a grudge was seen nowhere as vividly as in the treatment of his estranged wife, Florence. After she responded to his breakthrough triumph in The Bells by asking him if he intended to make a fool of himself forever, he broke off all communication with her and their children, one not yet born. Although he eventually reconciled with his sons, Harry and Laurence, and saw to their educations, he condemned his marriage to Florence to a living death. Now that he was successful, she craved the shared public spotlight of her husband’s fame, even as she hated him, and missed no opportunity to ridicule him to their boys. She could call herself “Mrs. Henry Irving” as much she liked and be received socially as such, but never again in his company. No doubt she was aware that others knew the truth. As part of her separation agreement she was always assigned an opening-night box; this was in addition to her “allowance”—polite terminology for ongoing blackmail payments made on the condition that she never speak of Irving’s relationship with Ellen Terry. It fell to Stoker and Irving’s secretary L. F. Austin to greet the ogress at openings, show her to the box, coo over the children, and conduct backstage tours.

Program for Irving’s Faust.

Florence Irving loathed Stoker and Austin at least as much as the men loathed each other. About eight months before, Austin had prepared an address for Irving to deliver at Harvard University—one he said brought tears to the actor’s eyes when it was read to him—but to his horror he discovered, and disclosed to his wife in a letter, “That idiot Stoker wrote a speech for the same occasion and I was disgusted to find it on the Governor’s table. When I read mine to Henry, he said: ‘Poor old Bram has been trying his hand but there isn’t an idea in the whole thing.’ ” Austin replied, “I should be very much surprised if there was.” To his wife, he went on:

The fact is Stoker tells everybody that he writes Henry’s speeches and articles, and he wants to have some real basis for this lie. This is why he worried H.I. into putting his name to an article which appeared in the Fortnightly Review, a fearful piece of twaddle about American audiences that B.S. was three months in writing. . . . I am not vindictive, as you know, but such colossal humbug as this . . . makes me a little savage. The misfortune is that in my position as a very private secretary compels me to keep in the background. I cannot tell the truth about my own work for that would not be right. Luckily, I have a faithful friend and ally in [George] Alexander, who knows everybody in London worth knowing and will prick Stoker’s bubble effectively.

George Alexander had replaced H. B. Conway as Faust after a disastrous opening, at least for the actor. Conway, hampered by illness, played the character like a deer in the headlights, tears welling in his eyes as he struggled through. It was testimony to the degree to which the title role was overshadowed by Irving, the stage effects, and the general hoopla surrounding the production that Conway’s performance itself drew little fire except within the Lyceum, where he was literally fired. Alexander would go on to greater fame as a major West End producer, whose stagings of Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Importance of Being Earnest (in which he also starred) propelled Oscar Wilde to his greatest fame.

That there was no love lost between Stoker and Alexander is evident between the lines of one of Stoker’s anecdotes about Faust. “One night early in the run of the play there was a mishap which might have been very serious indeed,” Stoker wrote. “In the scene where Mephistopheles takes Faust away with him after the latter had signed the contract, the two ascended a rising slope. On this particular occasion the machinery took Irving’s clothing and lifted him up a little. He narrowly escaped falling into the cellar through the open trap— a fall of some fifteen feet on to a concrete floor.” It is interesting that Stoker fails to mention that George Alexander was also dangerously swept off the stage and faced the same potential fate. Perhaps, as Austin hinted, Alexander had indeed been popping Stoker’s bubble around town.

Faust was the highlight of the Lyceum’s third American tour, in the fall and winter of 1887–88. Despite her dreadful experience in the shipwreck off the French coast earlier in the year, Florence Stoker accompanied her husband on the transatlantic voyage, only to face a particularly turbulent crossing on the City of Richmond in late October. She was distraught the entire trip and never again traveled to America. The weather didn’t improve, and the opening night of Faust at the Star Theatre on November 7 coincided with New York’s worst blizzard ever recorded. Most of the sold-out audience managed to get to the theatre anyway.

The production was a huge draw throughout the entire tour, despite some very frank appraisals. “Mr. Irving’s ‘Faust’ was viewed by a very large audience at the Star Theatre with admiration, but also with disappointment last evening. That is the plain truth, and it may as well be admitted at the start,” said the New York Times.

It is a good thing to be courteous to distinguished foreigners, and the courteous attentions (and money) American playgoers have hitherto bestowed upon Henry Irving have not been misapplied; but the expectations derived from the statements of English newspapers, from cable dispatches, and from the effusive descriptions of enthusiastic people who have been abroad concerning this drama, were not fulfilled on the occasion of its first presentation in this country. The scenic effects are often handsome, the groupings picturesque, the dresses suitable, and the changing calcium lights as pleasing and ingenious as all of Mr. Loveday’s efforts in that line. . . . On the other hand, the scenes of magic and mystery are all somewhat ludicrous, and not a bit thrilling. They recall the old comic pantomimes of the Lauri family and Tony Denier.#

Aside from the electrical swordplay and the “impressive and artistic” reproduction of sunset and moonlight, the Times found almost everything that had been praised elsewhere sadly lacking in the first American presentation. The effect of Faust’s rejuvenation was “clumsily managed.” The witches’ revels were presented “with stronger effect” in two different productions of Gounod’s opera recently staged in New York.

The vision of Margaret in the episode, of which so much has been said in praise, was merely Miss Terry walking across a plank like Amina in “La Sonnambula.” The yells of the spirits did not produce a sensation of horror; the temptation of Faust by two or three ordinary-looking girls was neither picturesque nor convincing, and the spectacle of Mr. Irving holding up the corners of his red cloak and gazing about him with a sardonic smile while the supernumeraries jumped and shouted did not inspire awe.

Even though the physical effects were “all good enough,” the Times wondered how the production had been “lauded as the finest spectacle of the age. Hence some of the disappointment.” George Alexander’s Faust was “a mere puppet” who treated the role “in a sing-song, monotonous way.” Irving’s acting was found to be facile: “[He] walks quickly, with a very decided limp, and is fond of stretching his arms before him, as if superintending an incantation. The familiar vocal tricks of the actor are all exaggerated in the character.” And, perhaps most damning of all, “If Mr. Irving’s rank as an actor depended upon his Mephistopheles alone, we do not think, judging from a first view of this work, that he would be the foremost man on the stage of England.”

Happily for the Lyceum coffers, Faust was critic-proof. Stoker felt that American religious attitudes were to be thanked. “In New York the business with the play was steady and enormous. New York was founded by the Bible-loving righteous-living Dutch.” New England was similarly predisposed toward morality tales. “In Boston, where the old puritanical belief of a real devil still holds, we took in one evening four thousand five hundred and eighty-two dollars—$4,582—the largest dramatic house up to then known in America. Strangely the night was that of Irving’s fiftieth birthday. For the rest the lowest receipts out of thirteen performances was two thousand and ten dollars. Seven were over three thousand, and three over four thousand.” In Philadelphia, “where are the descendants of the pious Quakers who followed Penn into the Wilderness, the average receipts were even greater.” In Stoker’s description, the clamor for tickets approached the frenzy of a religious revival run riot.

Indeed at the matinee on Saturday, the crowd was so vast that the doors were carried by storm. All the seats had been sold, but in America it was usual to sell admissions to stand at one dollar each. The crowd of “standees,” almost entirely women, began to assemble whilst the treasurer, who in an American theatre sells the tickets, was at his dinner. His assistant, being without definite instructions, went on selling till the whole seven hundred left with him were exhausted. It was vain to try to stem the rush of these enthusiastic ladies. They carried the outer door and the check-taker with it; and broke down by sheer weight of numbers the great inner doors of heavy mahogany and glass standing some eight feet high. It was impossible for the seat-holders to get in till a whole posse of police appeared on the scene and cleared them all out, only re-admitting them when the seats had been filled.

Mephistopheles on the Brocken. Painting by Amédée Forestier (1886).

Chicago was a completely different matter, a city that “neither fears the devil nor troubles its head about him or all his works,” and where “the receipts were not much more than half the other places.”

No matter where Faust played, picture postcards of Irving’s countenance and costume followed. Always camera-shy, Irving sat for only one photographic portrait, and surviving copies of the resulting postcard show him made up as an archetypal stage villain, with a widow’s peak, exaggerated eyebrows, and sharp, shifty eyes—almost uncannily the image of a twentieth-century movie vampire (though nothing like Stoker’s novelistic description of Dracula). If not inspirational, Stoker found the face of Irving’s Mephistopheles compelling, noting that

there is for an outsider no understanding what strange effects stage make-up can produce. When my son, who is Irving’s godson, then about seven years old, came to see Faust I brought him round between acts to see Mephistopheles in his dressing-room. The little chap was exceedingly pretty—like a cupid—and a quaint fancy struck the actor. Telling the boy to stand still for a moment he took his dark pencil and with a few rapid touches made him up after the manner of Mephistopheles; the same high-arched eyebrows; the same sneer at the corners of the mouth; the same pointed moustache.** I think it was the strangest and prettiest transformation I ever saw. And I think the child thought so, too, for he was simply entranced with delight.

Noel Stoker never mentioned the incident, so we can’t be sure exactly what he thought. However amusing, there is also something profoundly ambivalent in the act of literally demonizing a child, especially a child whose parents already gave him so many mixed messages about their affections. As if underscoring the point, Stoker published a ferocious short story about demoniacal children in the 1887 Christmas issue of the Theater Annual. Called “The Dualitists: or, The Death Doom of the Double-Born,” the tale concerns two little psychopaths, Harry Merford and Tommy Santon, morbidly and mutually obsessed with knives—more than a decade before Sigmund Freud began talking about the symbolism. “So like were the knives that but for the initials scratched in the handles neither boy could have been sure which was his own,” wrote Stoker. “After a little while they began mutually to brag of the superior excellence of their respective weapons. Tommy insisted that his was the sharper, Harry asserted that his was the stronger of the two. Hotter and hotter grew the war of words. The tempers of Harry and Tommy got inflamed, and their boyish bosoms glowed with manly thoughts of daring and of hate.”

The boys join forces in a game they call “Hack,” which at first involves terrorizing neighborhood girls. As Stoker explains, “It was a thing of daily occurrence for the little girls to state that when going to bed at night they had laid their dear dollies in their beds with tender care, but . . . when again seeking them in the period of recess they had found them with all their beauty gone, with arms and legs amputated and faces beaten from all semblance of human form.” In the time-honored manner of budding serial killers, they escalate to attacking and killing neighborhood pets. The animal kingdom thus decimated, they turn their malignant attention upon a pair of baby twin boys named Zacariah and Zerubbabel Bubb, whom they lure to a stable roof, where Harry and Tommy promptly begin smashing in their little faces. The Bubb parents, horrified and enraged, take aim with a shotgun at the monsters, but blow the heads off their own children instead. The boys play catch with the decapitated twins, then hurl the corpses down upon the mother and father, who are also killed. The parents are posthumously found guilty of murder, buried in unhallowed ground with stakes driven through their hearts, while Harry and Tommy are knighted for bravery.

“The Dualitists” is more disturbing than the darkest tales in Under the Sunset and, like “The Squaw,” hints at an increasingly dark side of Bram Stoker, bubbling like a witch’s brew during the years Irving achieved his greatest successes. These triumphs coincided with unprecedented pressures on Stoker’s time and finances, to the point that a second career as a barrister may have seemed a necessary and reasonable exit strategy—or at least some light at the end of the gravelike tunnel in which all of his own creative aspirations seemed destined to be interred.

One might expect, when it came time for the Lyceum to resurrect Macbeth, that the old superstitious custom of calling the production “the Scottish play” backstage, and never by its actual name, would be a tradition strictly enforced. However, as Shakespeare historian Paul Menzer reveals in Anecdotal Shakespeare: A New Performance History, no “curse” was attached to Macbeth until the early twentieth century, whereupon it arrived with “a fake genealogy” invoking various disasters attending productions dating back to Shakespeare’s time, none of them documented. “The history of Macbeth’s run of bad luck is a lie that sounds like the truth,” Menzer writes. The play has actually been quite lucky for companies that produce it, a perennial crowd-pleaser. Nonetheless, sometime between the First and Second World Wars—the same time, it might be noted, that King Tut’s curse was all the rage—a set of ritual beliefs and practices emerged, including not only the injunction against speaking the name “Macbeth” outside of rehearsal or performance, but an effective “remedy to undo the spell should one transgress,” requiring the violator to “leave the building, spin around three times, spit, curse, and then knock to be let back in.” Given the surprisingly recent nature of the belief, we can safely assume that Henry Irving and all in his company were free to shout or mutter “Macbeth!” as much as they liked and wherever they liked without fear of supernatural retribution.

Even if not cursed, Macbeth is still considered Shakespeare’s darkest play, and draws at least some of its shadowy glamour from being one of the Bard’s handful of late works performed indoors by candlelight, and thereby open to a degree of mysterious atmosphere and illusion impossible at the open-air Globe Theatre, where night could be only roughly indicated by dialogue and props—torches, candles, and lanterns. Indeed, Macbeth was premiered at the Globe in 1603, after the ascension of King James I—it is generally believed that the supernatural element in the play was a nod by Shakespeare to the king’s personal belief in witchcraft—but after 1609 it was also performed at the Blackfriars Theatre, a former priory hall that became the winter home for Shakespeare’s company. Unlike the Globe with its noisy pit, the Blackfriars was an elite playhouse that made use of rapidly advancing stage technology for previously impossible effects like the magical visions Shakespeare imagined in The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest.

Stoker had been familiar with Macbeth since his Dublin years, and he had favorably reviewed both the acclaimed Irish actor Barry Sullivan and the equally laureled Italian tragedian Tommaso Salvini in the role. In October 1873, reviewing Sullivan, he noted that “ ‘Macbeth’ occupies a peculiar position amongst plays—a melo-drama by its action, and more especially by its finale; and a tragedy by its underlying idea. It is no wonder that it is one of the most popular plays performed. What it must have been in the seventeenth century, when the belief in witches still existed, we can understand, when we consider the rapt attention of the nineteenth century audience at the incantation scenes.”

The three witches, virtually synonymous with the play itself in the public mind, interested Stoker enough that he would invoke them as the hungry wives of Dracula who materialize out of moonlit dust to gloat over Jonathan Harker. Even without Macbeth, the world’s mythologies and folklores overflow with triadic female entities; the Gorgons, Fates, Furies, Hours, and Graces, for instance, were all supernatural sisters who traveled in threes. And Stoker needn’t have gone further than his alma mater, Trinity College, to make a basic imaginative connection between things mystical, mysterious, and triplicated.

Irving’s weird sisters took inspiration from Henry Fuseli’s famous painting of 1783.

Stoker found Macbeth an especially, and essentially, sympathetic character. “We sympathize with him as we do with Faust, who, deluded by the powers of Evil, awakes too late to the awful knowledge that diabolical promises are based on sand. . . . The tragedy of ‘Macbeth’ consists in the way in which Fate closes round the hapless Thane, slowly but surely darkening his path by degrees, like the shades of evening.” In a later appreciation of the Sullivan production, he was especially taken with the stagecraft employed in representing Dunsinane Castle. “It was supposed to be vast, and occupied the whole back of the scene. In the centre of the gate, double doors of a Gothic archway of massive proportions. In reality it was quite eight feet high, though of course looking bigger in perspective.” Sullivan entered “thundering” his speech as the huge entranceway effortlessly flew open. “Now this was to us all very fine, and it was vastly exciting. None of us ever questioned its accuracy to nature. That Castle with the massive gates thrown back on the hinges by the rush of a single man.”††

Cartoon of Henry Irving as Macbeth.

Where Barry Sullivan was powerful and impassioned, Salvini’s Macbeth was morally weak. Describing the April 1876 performance, Stoker noted that “his dagger soliloquy is done in a much quieter manner than is usual, and in nowise does he confound, as too many tragedians do, the air-drawn dagger with a real thing. He knows throughout that it is a phantom, and no more tries to clasp it than he would seek to wrestle in actual combat with the ghost of Banquo.” As he approaches Duncan’s chamber for the murder, “the thought of fear, awakened by conscience, suddenly strikes him, and he looks round with the glare of a wild animal at bay and then, suddenly finding his resolution, quickly enters with a gesture of impatience at his own weakness.”

Henry Irving had first played Macbeth at the Lyceum in 1875 for the Batemans and, except for the new staging, held to his earlier essaying of the role for his new production in 1887. It was an interpretation both eccentric and, for the actor, more than a little self-serving. Instead of a vacillating thane, goaded by his far more resolute consort to kill King Duncan and take his throne, Irving’s Macbeth is determined from the start. Ellen Terry described him as looking like “a famished wolf” in the part. The witches’ prophecies and his wife’s encouragement merely reinforce the plans he has already formed. This approach, of course, drains the menace out of the witches by making them cheerleaders rather than agents of fate. Worse, it effectively eviscerates the character of Lady Macbeth, reducing her to a swept-along accomplice, a supportive spouse in the middle-class Victorian mold rather than the cold-blooded avatar of feminine evil—a quasi-vampiress—that has traditionally made the role an especially coveted assignment for actresses. Once more, Irving’s willingness to undermine Ellen Terry and relegate her to a less showy part was evident. Terry would still receive plaudits, of course, for her “womanliness” in a role better defined by lines like “Spirits that tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here.” Unfortunately, this Lady Macbeth would be forced to sleepwalk on more than one level.

Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth.

Irving encounters the witches in the Lyceum production of Macbeth.

But on the level of memorable iconography, Terry fared far better than Irving, owing to a stunning costume designed by Alice Comyns Carr. Loosely crocheted from green yarn and blue tinsel to create the appearance of chain mail, and bordered with Celtic designs, the dress was finally gold-embroidered and ornamented with a thousand iridescent wings of the green “jewel beetle,” Sternocera aequisignata. Comyns Carr felt the decoration “would give the appearance of the scales of a serpent.” (Perhaps Stoker still held the image in mind when he concocted a formidable snake-woman for his final novel, The Lair of the White Worm.) A heather-colored cloak decorated in a griffin motif completed the apparel, and Terry additionally wore a massive red wig, its long braids enlaced with spiraling ribbons. As Terry described the look to her daughter, “The whole thing is Rossetti—rich stained-glass effects.”

Oscar Wilde, by then editor of the periodical The Woman’s World, where he gave expert advice on all matters pertaining to decorating and fashion, quipped to his readers, “Lady Macbeth seems to be an economical housekeeper and evidently patronizes local industries for her husband’s clothes and the servant’s liveries, but she takes care to do all her own shopping in Byzantium.”

Henry Irving as Macbeth.

John Singer Sargent’s 1906 memory impression of Ellen Terry in Macbeth.

The painter John Singer Sargent, who attended the opening night, was immediately enthusiastic about the visual impression Terry made, and he proposed to commemorate Lady Macbeth on canvas. Wilde, who watched Terry arrive to pose at his neighbor’s Tite Street studio, commented, “The street that on a wet and dreary morning has vouchsafed the vision of Lady Macbeth in full regalia magnificently seated in a four-wheeler can never again be as other streets: it must always be full of wonderful possibilities.” Sargent and Terry conspired on a pose that never appeared in the production but restored Lady Macbeth to full strength and volition as she raised the slain Duncan’s crown above her head in a triumphant self-coronation.‡‡ Before eventually moving to its permanent home at the Tate Gallery, the life-sized portrait would hang for many years in the Lyceum’s Beefsteak Room, near to some charming but soon to be forgotten landscapes of Frank Miles, that painter now sadly removed from the London art world and languishing in an asylum, waiting for death.

Despite the narcissistic way in which Irving undermined Shakespeare’s conception of Macbeth, the images of an unquenchable evil spawned by the play haunted Stoker powerfully as he gestated his most famous novel: the desolate castle, the three weird sisters, the revenant dead, disturbed sleep and somnambulism, and indelible spots of blood everywhere. Lady Macbeth’s famous comment on the dead king Duncan might well serve as an observation on Dracula himself, in both his supernatural aspect and his cultural longevity: “Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?”

Macbeth: Duncan’s fatal arrival at Dunsinane Castle. A souvenir program illustration for Irving’s production by John Jellicoe.

* As told by Stoker, who physically blocked the ambassador from stumbling into the limelight: “Under ordinary circumstances I think I should have allowed the contretemps to occur. Its unique grotesqueness would have ensured a widespread publicity not to be acquired by ordinary forms of advertisement. But there was a greater force to the contrary. The play was not yet three weeks old in its run; it was a tragedy and the holy of holies to my actor-chief to whom full measure of loyalty was due; and beyond all it was Ellen Terry who would suffer.”

† The magazine also related, “upon authority not traceable, that years ago a Munich butcher came out of a trance in the middle of the night and found himself in the Deadhouse. The shock this discovery gave him is said to have entirely shattered his nerves and though still alive, he is a nervous wreck.”

‡ Although one is tempted to read “scar” as a typographical error for “scarf,” Ellen Terry’s appearance as a vision was intended to foreshadow Margaret’s death; in Wills’s script, Faust explicitly wonders “what means that slender scarlet line / Around her throat—no broader than a knife.” In Goethe, Mephistopheles goes further, comparing her to the beheaded Medusa: “Be not surprised, if you should see her carry / Her head under her arm—’twere like enough; / For since the day that Perseus cut it off, / Such things are not at all extraordinary.”

§ Flash powder, commonly used in magic acts, derived from the flammable dried spores of the lycopodium plant, a kind of clubmoss.

¶ The land area immediately surrounding a structure.

# Charles Lauri was famous for his animal impersonations in pantomimes at the Drury Lane Theatre in London; Tony Denier produced Christmas pantomimes at the Adelphi.

** No images survive of Irving wearing a mustache for the role, but it is quite possible he saw fit to add one in later seasons. The only representations of Mephistopheles—one photograph, one oil painting, several watercolors, and numerous drawings—all seem to have been created for the inaugural production.

†† There is no better location than a castle to divert the imagination and assist the suspension of disbelief. It has been repeatedly asserted that Castle Dracula was inspired by Slains Castle, a landmark at Cruden Bay, Scotland, where Stoker spent holiday time while writing the novel, but to anyone growing up in England or Ireland, real castles were just part of the ordinary landscape, and they had always been central to the virtual landscape of fairy tales. By the time Bram Stoker was in his forties, he hardly needed the poke of inspiration to realize a haunted castle might be a good location for a scary story.

‡‡ Sargent’s painting is reproduced in the color plate section of this book.