Greeba Castle on the Isle of Man, private lair of novelist Hall Caine (on staircase).

Greeba Castle on the Isle of Man, private lair of novelist Hall Caine (on staircase).

HEAVEN SAVE ME FROM THIS FIEND THAT TAKES HOLD OF ME AND POSSESSES ME!

— Hall Caine, Drink

Bram Stoker and Thomas Henry Hall Caine met for the first time at the glittering premiere of Hamlet at the Lyceum on December 30, 1878. Caine, an ambitious twenty-six-year-old journalist and budding novelist from Liverpool who had been one of Henry Irving’s most vocal public supporters in the provinces, had received a note earlier that day from stage manager Henry Loveday. “Delighted to see you tonight,” it read. “See Mr. Bram Stoker—he has a seat in a box for you. Come round later.”

Caine was in good company. Among those assembled to bear witness to the christening of Henry Irving’s new temple of culture were the Prince and Princess of Wales (and, seated quite separately, the prince’s mistress, the actress Lillie Langtry), the politicians Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone, the painters James McNeill Whistler and John Everett Millais, and the writers Algernon Charles Swinburne and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Oscar Wilde, who had not yet officially relocated to London but was nonetheless in town to get a start on his social climbing, was also there, only a few weeks after Stoker’s Dublin marriage to Florence Balcombe, a social ceremony he pointedly did not attend. There is, sadly, no record of what interesting words of greeting may have transpired between Wilde and Stoker. It is highly unlikely that Stoker arranged for Wilde’s ticket, and more plausible that he attended as the guest of Mrs. Langtry.

Irving’s courtesy to the Liverpool theatre critic was both gracious and strategic; like Stoker, Caine had provided Irving with invaluable press agentry in the guise of theatre criticism on the pages of the Liverpool Town Crier and might well be very useful again. There were so many parallels between Stoker and Caine that it is surprising they didn’t meet much earlier. Dublin and Liverpool were sister cities on opposite sides of the Irish Sea, and between them was the Isle of Man, Caine’s ancestral home, where he spent large stretches of his boyhood. For both young men, an early interest in folk and fairy lore led to a bottomless appetite for books and a special fascination for the theatre. In the 1870s they saw all the same touring productions at roughly the same time; because of their geographical proximity, a theatre company’s stop in Dublin was often followed by one in Liverpool, or vice versa. They were both admirers of Henry Irving, Whitman, Swinburne, Rossetti, and Edward Dowden—Stoker’s mentor and Caine’s correspondent. Stoker was born sick, and Caine grew up thinking he was sick; hypochondria and vague nervous complaints dogged him all his life, sometimes prompting him to seek out dubious cures.

Where Stoker’s major interest in fairy tales rose from his exposure to Christmas pantomimes, Caine attributed his own baptism in folklore to his Manx grandmother. “She believed in every kind of supernatural influence,” wrote Caine. “I think of her now feeding the fire with the crackling gorse* while she told me wondrous tales.” She claimed to have seen fairies with her own good eyes as a girl, and told how, in the light of the moon, she was beset by a “multitude of little men, tiny little fellows in velvet coats and cocked hats and pointed shoes, who ran after her, swarmed over her and clambered up her streaming hair.” It was Caine’s grandmother who gave him the Manx nickname “Hommy Beg,” meaning “Little Tommy.”

For all the similarities between Stoker and Caine, there was one major difference, which must have been all the more exaggerated as Caine ascended the dozen carpeted, brass-railed steps that led to the Lyceum main lobby—an architectural feature that always reminded audiences, at least on a subliminal level, that they were meant to have an elevated experience. But there was nothing subliminal about Stoker’s imposing presence. He was a big, bearded bear of a man over six feet tall, while Caine was nervous, slight, and diminutive—five feet three inches tall by some accounts, five-four by others. “Little Tommy” was right. Their first encounter at the theatre must have been like a scene between a giant and a dwarf in a pantomime. Had Punch cartoonist Harry Furniss been there, his efforts, no doubt, would have resulted in something very much like his satirical sketch of Lady Wilde and Sir William.

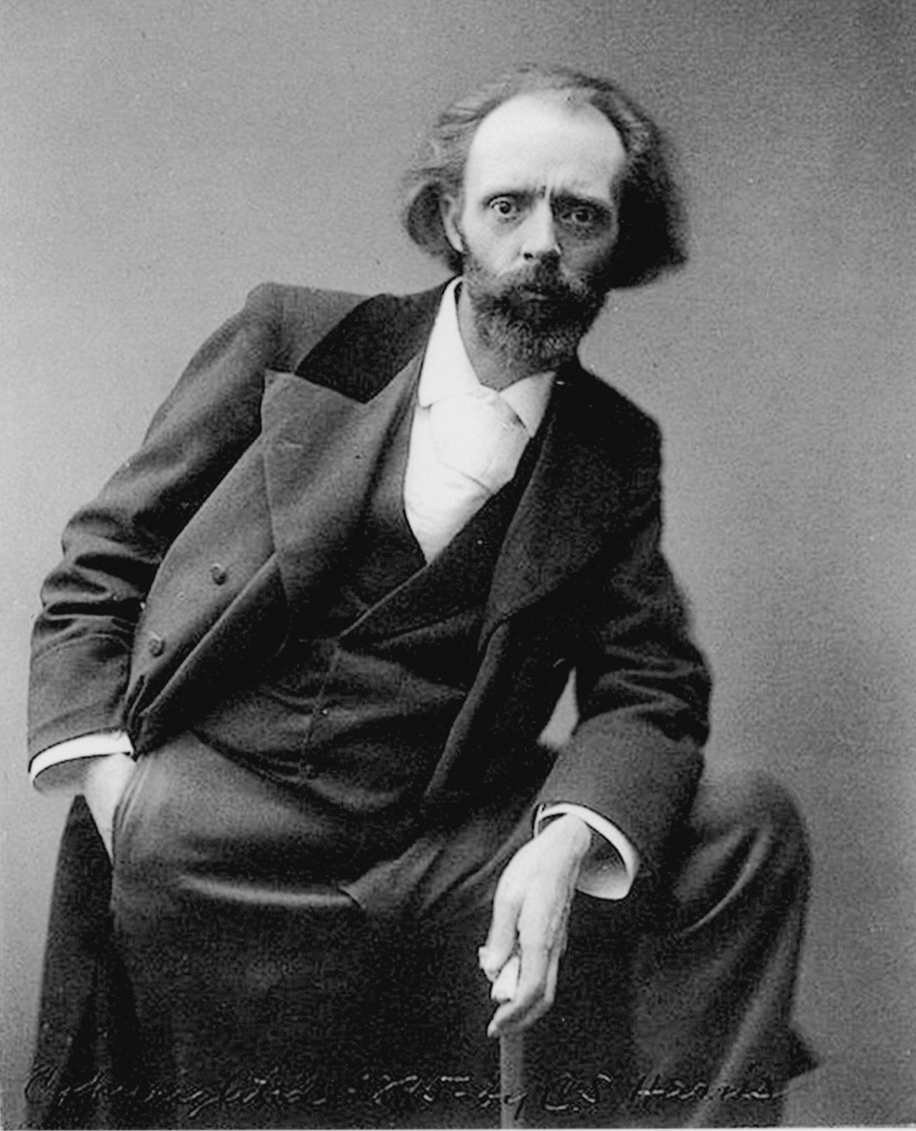

Hall Caine as a rising author.

Caine’s first impression of Stoker may have been a bit like that recorded by author Horace Wyndham, even if, on this particular night, his gatekeeper persona had yet to be buffed to a high polish. “To see Stoker in his element was to see him standing at the top of the theatre’s stairs, surveying a ‘first night’ crowd trooping up them,” wrote Wyndham. “A Lyceum opening could be counted on to draw an audience that was really representative of the best of the period in the realms of art, literature, and society. Admittance was a very jealously guarded privilege. Stoker, indeed, looked upon the stalls, dress circles and boxes as if they were annexes to the Royal Enclosure at Ascot, and one almost had to be proposed and seconded before the coveted ticket would be issued.”

Although both men were status conscious and relished elbow-rubbing with the glitterati, in 1879 they were still in the early stages of their writing careers. People were struck with Caine’s resemblance to certain portraits of William Shakespeare, and he enjoyed the comparison (what young writer wouldn’t?), trimming his beard and brushing his hair back from his high forehead accordingly. The look became a central part of his self-presentation, so much so that when a shipboard barber once took a bit too much off his beard, he hid in his cabin for the duration of the trip. Caine had published essays on the supernatural element in poetry and Shakespeare. Neither had published a novel, but Caine would beat Stoker to the punch beginning in 1885 with a well-received first thriller, The Shadow of a Crime, quickly followed by She’s All the World to Me: A Manx Novel (1885), A Son of Hagar (1886), and the best-selling The Deemster (1887). His Recollections of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1882) and Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1887) did not fare as well. Oscar Wilde had taken no note of Caine at the Hamlet premiere, but later as a reviewer dismissed the Rossetti memoir out of hand, and wrote of the Coleridge biography, “So mediocre is Mr. Caine’s book that even accuracy couldn’t make it better.” Wilde complained that “never for one single instant are we brought near to Coleridge[;] the magic of that wonderful personality is hidden from us by a cloud of mean details, an unholy jungle of facts. . . . Carlyle once proposed to write a life of Michael Angelo without making any reference to his art, and Mr. Caine has shown that such a project is perfectly feasible.” On another occasion Wilde’s contempt was far more general and sweeping: “Mr. Hall Caine, it is true, aims at the grandiose, but he writes at the top of his voice. He is so loud that one cannot hear what he says.”

For a pair of men who would be remembered legendarily as closest friends and confidantes, Caine and Stoker seem to have remained only acquaintances during the 1880s. Bram and Florence were nearly Caine’s neighbors when they moved to Chelsea. At 10 Cheyne Walk, Caine lived with the declining Rossetti, serving as secretary, companion, and drug-dispensing nurse (a chronic insomniac, Rossetti was hopelessly addicted to chloral hydrate) until the death of the painter in 1882, shortly before the Stokers relocated to number 26. Caine provided Bram with some secondhand intimacy to one of the most ghoulish episodes in art history. Rossetti had founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and his mistress Elizabeth Siddal was one of the movement’s more important models, helping to define for the Victorian mind how, exactly, medieval maidens ought to look. In 1862, not long after she finally married Rossetti, Siddal died of a laudanum overdose. She was buried in Highgate Cemetery with a notebook of her husband’s unpublished poetry, with a strand of what William Michael Rossetti described as her “lavish heavy wealth of coppery golden hair” wrapped around it before the coffin was closed. Seven and a half years later, Rossetti wanted the poems back. Friends oversaw the exhumation by torchlight, and as legend tells it, Siddal’s corpse was like that of an uncorrupted saint, and her beautiful hair had continued to grow, filling the casket. The fact that the notebook was drilled through with wormholes argues against a flawless state of preservation—one explanation, that she had been essentially pickled by laudanum use, was scientifically absurd. In all likelihood the story was told to Rossetti to assuage the guilt of a grave robber. If the body was beatific, it could be, perhaps, a sign of approval from the beyond.

Stoker would echo the incident in two pieces of fiction. In Dracula, Lucy Westenra, with her “sunny ripples” of hair, is interred in a cemetery very much like Highgate, and when the vampire hunters open her coffin, her features still have the blush of life. In Stoker’s short story “The Secret of the Growing Gold” (written circa 1897, published 1914), a murdered woman’s shorn golden hair continues to grow, pushing up through fireplace stones beneath which it lies buried, causing the killer husband to die of fright. The vengeful undead propensities of blond female hair were also prominent in Magyar folktales Stoker consulted while researching Dracula and appear in Irish legends as well.

We don’t know when Stoker first heard the exhumation story from Caine, and he almost certainly first heard it somewhere else. Although Caine was a notorious pack rat—nearly ninety years after his death, an enormous volume of his personal papers has yet to be cataloged by its repository, the Manx National Heritage Library and Museum. At the personal request of the present author, in 2010 the library conducted a half-year effort, including the aid of volunteers, to uncover previously unknown correspondence between Stoker and Caine. Although scores of new letters and some telegrams were found, almost none include personal or literary revelations about Stoker, and they are overwhelmingly about Caine’s publishing interests, for which Stoker acted in a significant way as adviser, editor, and agent. The letters also reflect a shifting intimacy. Sometimes Stoker opens his correspondence with stiff formality (“My dear Hall Caine,” “Dear Caine,” or just “Caine,” even after he has begun making jokes and using the salutation “Hommy Beg,” alternately “Hommybeg”). Stoker’s astute contract advice, supplementing any opinion Caine received from his own lawyer, begins in 1887, before Stoker has negotiated any novel contract on his personal behalf—but exactly during the period he was reading for the London bar and completing his own first novels. Since it is impossible to believe Stoker worked for free or waived commissions on Caine’s increasingly substantial earnings—how could he afford to?—we are led to only one conclusion: that Stoker’s income from literary management and editing was sufficiently lucrative and flexible to preclude choosing between his Lyceum job and conventional, day-consuming work as a barrister.

The Rossetti gravesite, Highgate Cemetery. It was here that Dante Gabriel Rossetti exhumed his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, to retrieve a book of poetry he had buried with her. (Photograph by the author)

Illustration for Stoker’s “The Secret of the Growing Gold” from Famous Fantastic Mysteries (1947).

In early 1887, Stoker pointed out to Caine that he had made ill-advised concessions to a newspaper syndicate for serial rights and subsequent hardcover options for his first books, and suggested remedies for his forthcoming novel, The Deemster (the Manx term for “judge”; the book dealt with hothouse criminal intrigue on the Isle of Man, where it created an uproar, even though Caine set it in the eighteenth century to avoid controversy).

In a long typewritten letter dated February 1887, Stoker concludes, “You see, my dear Hall Caine, that I write on the typewriter so that you may be able to follow the important business without stopping to swear—necessarily—at my calligraphy!” It is a rare, and perhaps the only, acknowledgment of the frequent illegibility of his rushed, headlong handwriting, which was surely a chronic symptom of the difficulty Stoker had simply keeping up with his own thoughts.

The Deemster was a bona fide best seller, and Caine immediately set about dramatizing it. Irving wanted to produce the play but was too late in making an offer, and it was successfully staged at the Princess Theatre instead of the Lyceum. This led to Caine and Irving discussing a variety of projects on which they might collaborate. According to Stoker, “the conversation tended towards weird subjects.” It was only appropriate, since today both Hall Caine and Henry Irving are summoned forth from their graves by the public mostly because of their association with Stoker and Dracula. When, one night in the Beefsteak Room, Caine told of having once seen in a mirror a reflection that wasn’t his own, Irving responded by telling how an accidental effect in a mirror gave him an inspiration for the materialization of Banquo’s ghost in Macbeth. As Caine later wrote, “During many years I spent time and energy and some imagination in an effort to fit Irving with a part. . . . I remember that most of our subjects dealt with the supernatural, and that the Wandering Jew, the Flying Dutchman and the Demon Lover were themes around which our imagination constantly revolved.”

Irving, always thinking big, thought the prophet Mohammed might be an excellent part. He engaged Florence Stoker, fluent in French from her Dublin education, to translate Henri de Bornier’s successful play Mahomet for Caine to review. Although a paying job for the Lyceum, it was hardly the kind of artistic employment she had once expected from Irving, but on which she had long given up. Caine didn’t find the de Bornier play useful and came up with his own scenario, which he preferred to perform for Irving rather than submit a preliminary script. The night before, staying with Bram and Florence Stoker, he memorably rehearsed his pitch. As Stoker described the recital:

Now in the dim twilight of the late January afternoon, sitting in front of a good fire of blazing billets of old ship timber, the oak so impregnated with salt and saltpetre that the flames leaped in rainbow colours, he told the story as he saw it. . . . That evening he was all on fire. His image rises now before me. He sits on a low chair in front of the fire; his face is pale, something waxen-looking in the changing blues of the flame. His red hair, fine and long, and pushed back from his high forehead, is so thin that through it as the flames leap we can see the white line of the head so like Shakespeare’s. . . . His hands have a natural eloquence—something like Irving’s; they foretell and emphasize the coming thoughts. His large eyes shine like jewels as the firelight flashes. Only my wife and I are present, sitting like Darby and Joan† at either side of the fireplace. . . . We sit quite still; we fear to interrupt him. The end of his story leaves us fired and exalted too.

Irving liked it as well, but an actual production was never to materialize. “I spent months on ‘Mohammed,’ ” Caine wrote, “and think it was by much the best of my dramatic efforts; but immediately it was made known that Irving intended to put the prophet of Islam on the stage, a protest came from the Indian Moslems, and the office of the Lord Chamberlain intervened. This was a deep disappointment to Irving, for the dusky son of the desert was a part that might have suited him to the ground.”

Caine proposed a stage adaptation of his poem “Graih my Chree” (Manx for “Love of My Heart”), a retelling of the Scottish legend “The Demon Lover,” about an unhappily married woman who takes to the sea with a former suitor, only to learn he is a cloven-hoofed demon who offers hell in place of a honeymoon. The actor thought the part would be too young for him. Could Caine do something with the similar Flying Dutchman story instead? He still wanted to redeem the failure of Vanderdecken. Caine tried, but to no avail: “In spite of the utmost sincerity on both sides, our efforts came to nothing, and I think this result was perhaps due to something more serious than the limitation of my own powers.” He felt that Irving had become so used to playing the part of “Henry Irving” that “it stood in the way of his success in a profession wherein the first necessity is that the actor should be able to sink his own individuality and get into the skin of somebody else.”

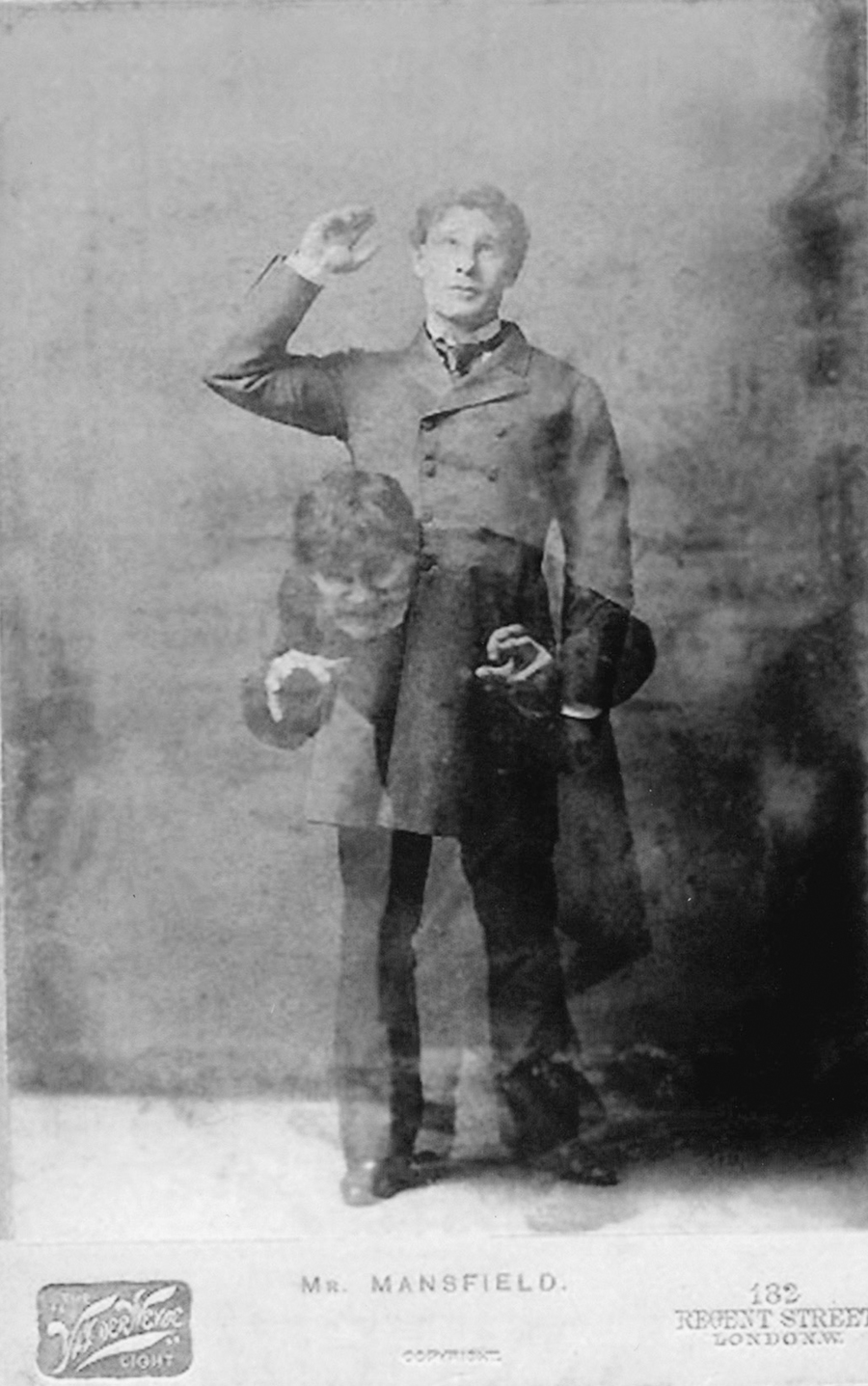

The American actor Richard Mansfield was a performer who had no difficulty changing his skin, as he proved with the great stateside success of his adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novella Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Irving rented him the Lyceum in the late summer and early autumn of 1888 to present the show in London while Faust toured the provinces. Mansfield shapeshifted in plain view of the audience, using colored lighting that made his preapplied reddish makeup, imperceptible under warm illumination, horrifying apparent as the light shaded toward blue. Irving himself had passed up the chance to perform the dual role himself, though his son H. B. Irving would make a hit of it years later. Mansfield’s production was terribly ill timed. Only a few weeks after it opened, East London experienced the first of what would initially be called the Whitechapel Murders—and then, as the body count of gutted prostitutes relentlessly increased, the perpetrator would be immortally christened as Jack the Ripper.

Souvenir postcard of Richard Mansfield in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, produced at the Lyceum at the time of the Jack the Ripper murders.

The events in Whitechapel quickly dampened the public’s appetite for imaginary horrors, and Lyceum box office receipts fell precipitously. Mansfield himself came under suspicion—at least by one impressionable theatregoer who wrote to the London police that he “went to see Mr Mansfield Take the Part of Dr Jekel & Mr Hyde I felt at once he was the Man Wanted & I have not been able to get this Feeling out of my head. . . . I thought of the dritfull manor we works himself up in his part that It might be possible to work himself up So that he would do it in Reality.” Professional critics weren’t quite so suggestible. “There is but little scope for acting in what has been described as Mr. Stevenson’s ‘psychological study,’ ” opined the Times. “Mr. Mansfield’s appearances, now in the one part and now in the other, involve no more psychology than the ‘business’ of a ‘quick-change artiste’ in the music halls.” The Times reviewer cited Henry Irving’s role in The Bells as a far superior study in divided psychology.

For all the publicity it generated, the Mansfield engagement at the Lyceum was not lucrative, and the actor ended up heavily indebted to Irving. Some commentators worried that the grisly play itself had inspired a real-life madman, while the East End Advertiser felt the public was affected “the same way as children are by the recital of a weird and terrible story of the supernatural.” In a piece called “A Thirst for Blood,” the paper observed that “the mind turns unnaturally to thoughts of occult force, and the mysteries of the Dark Ages rise before the imagination. Ghouls, vampires, bloodsuckers, and all the ghastly array of fables which have accrued throughout the course of centuries take form, and seize hold of the excited fancy.”

The Ripper targeted prostitutes, at first in dark alleys, cutting their throats (which silenced them instantly) and then mutilating their bodies, especially their bellies. Eleven crimes between April 1888 and February 1891 were classified by police as the Whitechapel Murders, but over time experts have come to consider only five of them—the so-called canonical five—as committed by the Ripper. The first two occurred nine days apart, on August 31 and September 8, when Mary Ann Nichols and Annie Chapman both had their throats cut and abdomens torn open; Chapman’s uterus was taken as a souvenir. The murderer struck for the third and fourth times on the same night, September 30. Elizabeth Stride suffered a cleanly sliced throat with no mutilations, and it was theorized the killer was simply interrupted. (Some modern investigators feel, however, that Stride’s murder may have been a coincidence rather than an unfinished Ripper outrage.) Catherine Eddowes, the night’s other fatality, was attacked far more savagely, and her left kidney went missing, along with most of her uterus.

On November 9, the most horrific killing took place in the shabby boardinghouse room of Mary Jane Kelly, giving the murderer the luxury of time to complete his desecrations unobserved. She was completely disemboweled; her uterus and breasts were arranged behind and about her head and body, and the flesh from her thighs was heaped on a bedside table. The face, hacked to the bone, was virtually beyond recognition as human. On this night the Ripper made a new choice of bloody keepsake—Mary Jane Kelly’s heart.

The murder of prostitute Mary Jane Kelly, the Ripper’s last victim, was especially ghastly.

Neither of the missing uteruses, nor the heart, was ever found, but half of an alcohol-preserved left kidney was sent in a small cardboard box to George Lusk, chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, on October 16 with a short letter. Return-addressed “From hell,” it read:

MrLusk

Sir

I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer.

Signed Catch me when you can

MISHTER LUSK

All over London, women were terrified, regardless of class or location. In the East End, the fear was understandably immediate and visceral. In the West End, women like Florence Stoker were not in danger of being literally gutted; still, their midsections daily endured the assault of the corset, and the murders could only reinforce a more general sense that every presuffrage woman was chattel, always at risk of having her life emptied and diminished by the actions of men.

The Ripper was never caught, but in the ensuing century and a quarter nearly a hundred suspects or theories have been proposed, perhaps none so intriguing as the case made against a Canadian-born American quack doctor, Francis Tumblety, who had both the opportunity and a misogynistic psychological profile that was disturbingly on point. Born in 1833, the son of an Irishman, Tumblety claimed to have studied medicine at Trinity College Dublin—he claimed a lot of things, as quack doctors usually do—but the essence of his education consisted of peddling pornography on the Erie Canal when he was fifteen. A Rochester acquaintance described him as “a dirty, awkward, ignorant, uncared-for, good-for nothing boy.” After an apprenticeship in Rochester with a back-alley abortionist who employed both surgical and medicinal means, Tumblety styled himself as an “Indian Herb Doctor,” and thereafter took his show on the road in Canada and the United States, bilking the public with cure-all elixirs and nostrums and often finding himself just a few steps ahead of the law. The chase seemed to excite him. He made enough money to affect the trappings of wealth and sported phony military garb and decorations. His most prominent feature was an enormous mustache that overpowered his lower face. In 1865 he was accused of aiding John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln; although the charge was false, he relished the publicity.

In short, Francis Tumblety was a character who might have been invented by Mark Twain. He did, in fact, navigate the Mississippi, using St. Louis as a base of operations for a period. In hindsight, the world would have been a better place had his existence been confined to humorous fiction.

First, there was his hatred of women. It was said he was betrayed by a woman he married, who turned to prostitution, although this cannot be documented. According to Colonel C. A. Dunham, a New Jersey lawyer who knew Tumblety in Washington, D.C.:

Francis Tumblety, notorious American quack doctor, and an unhealthy controlling presence in Hall Caine’s early life. In addition to a predatory taste for young men, the Tumblety style included phony military affectations and dress.

Someone asked why he had not asked some women to his dinner. His face instantly became black as a thunder-cloud. He had a pack of cards in his hand, but he laid them down and said, almost savagely, “No, Colonel, I don’t know any such cattle, and if I did I would, as your friend, sooner give you a dose of quick poison than to take you into such danger.” He then broke into a homily on the sin and folly of dissipation, fiercely denounced all women and especially fallen women.

Then, for an unexpectedly grisly nightcap, he invited the guests into his office. “One side of this room was entirely occupied by cases, outwardly resembling wardrobes,” Dunham wrote. “When the doors were opened quite a museum was revealed—tiers of shelves with glass jars and cases, some round and others square, filled with all sorts of anatomical specimens. The ‘doctor’ placed on a table a dozen or more jars containing, as he said, the matrices [uteruses] of every class of woman. Nearly one half of one of these cases was occupied exclusively with these specimens.”

No one knows, or ever asked, where the uteruses came from.

After a while, Tumblety’s ongoing games of cat-and-mouse with the authorities over his dubious medical activities escalated to the point that prosecution and imprisonment were real possibilities. Like a certain Transylvanian vampire, having exhausted the possibilities of his native land, Francis Tumblety set sail for England. When he set up shop in Liverpool in 1874, he advertised as usual and attracted customers as usual, many of them suffering from “nervous” complaints, as well as hypochondriacs with their multiform attendant anxieties. From a business standpoint, bottomless issues were always the best.

Since Tumblety advertised himself as an “electric physician” of international renown, we can comfortably assume hypnosis was also found in his bag of tricks, along with the “blood purifiers,” “pimple-banishing” ointments, and the like. Mesmeric or not, he was a forceful magnet for young men, and an attractive coterie inevitably clustered around him when he arrived in a new city. “He had a seeming mania for the company of young men and grown-up youths,” observed the American lawyer William P. Burr, who added that “once he had a young man under his control he seemed to be able to do anything with the victim.”

One of these young men was Hall Caine, who sought out Tumblety’s services in 1874 and quickly became one of his favorite pets. Opinion is nearly universal among Caine’s chroniclers that the relationship was both sexual and exploitative. Caine had girlfriends, none that lasted, but at least one friend from childhood, William Tirebuck, who showed signs of having been romantically fixated on him. Tirebuck knew about Tumblety and expressed some mild jealousy about his friend’s relationship. Following whatever “medical” advice or treatment Caine received, Tumblety found his new conquest especially useful for writing pamphlets and letters in his defense, for no matter where the herb doctor went, angry criticism and denunciation were sure to follow.

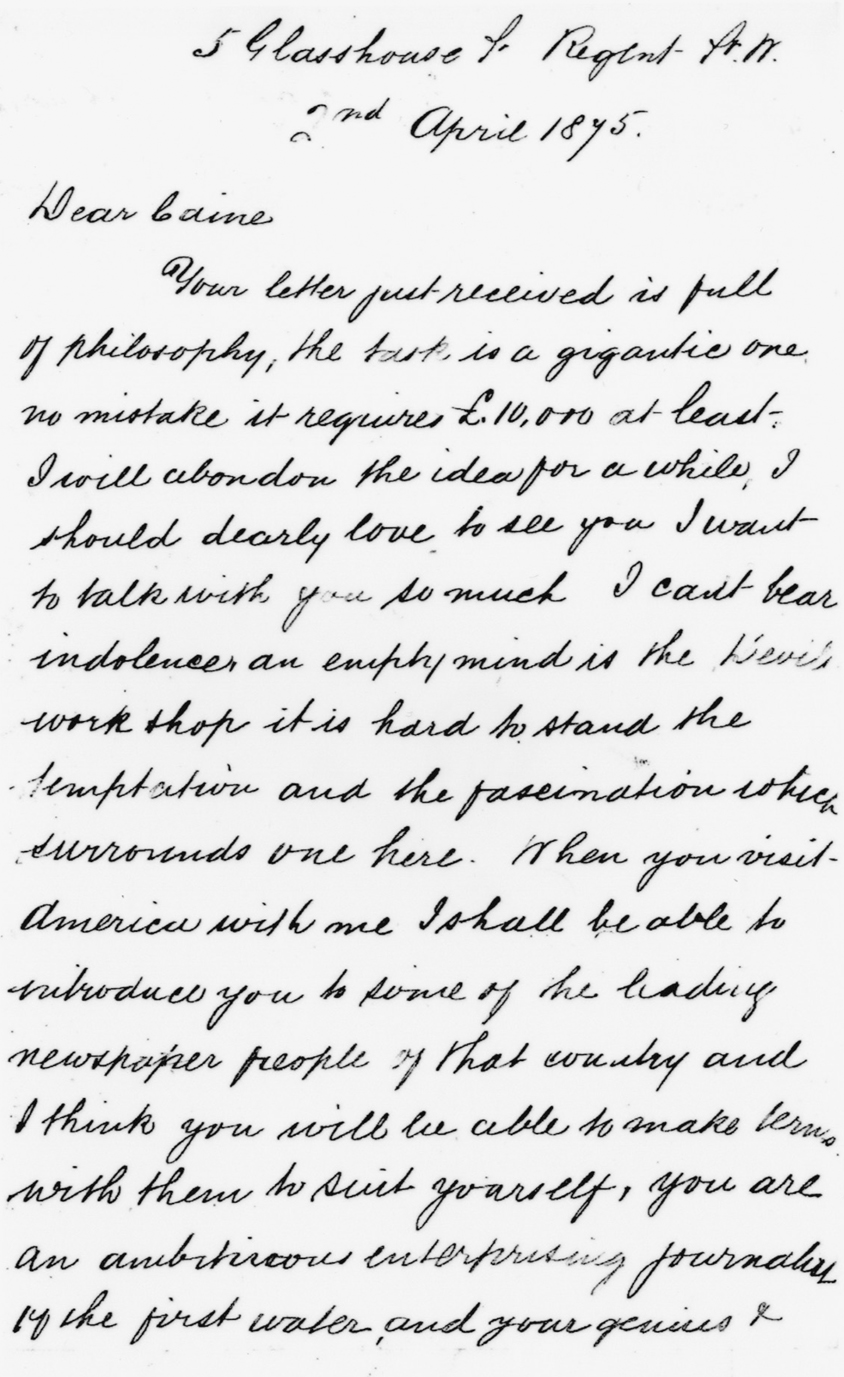

Considering the older man’s overbearing sociopathy, it is doubtful the affair left Caine with idealized notions about the Whitmanesque possibilities of romance between men. Whitman didn’t eroticize master-slave arrangements, or manipulative blandishments meant only to keep the weaker party in control. “Your letter just received is full of philosophy,” reads a typical, unctuously flattering letter from London in April 1875. “I should dearly love to see you I want to talk to you so much. . . . An empty mind is the Devil’s workshop it is hard to stand the temptation and the fascination which surrounds one here.” He doesn’t describe these London temptations, but it is Caine, apparently, who keeps him from partaking. “When you visit America with me I shall be able to introduce you to some of the leading newspaper people of that country and I think you will be able to make terms with them to suit yourself, you are an ambitious enterprising journalist of the first order, and your genius & talent will be appreciated in America. . . . I am interested in everything that concerns your welfare. . . . I have taken pleasure in showing your letter to literary gentlemen of your own profession and you are an ornament to it. The newspaper people here want to see you.”

Advertisement for Tumblety’s “pimple banisher,” a typical quack cure of the time.

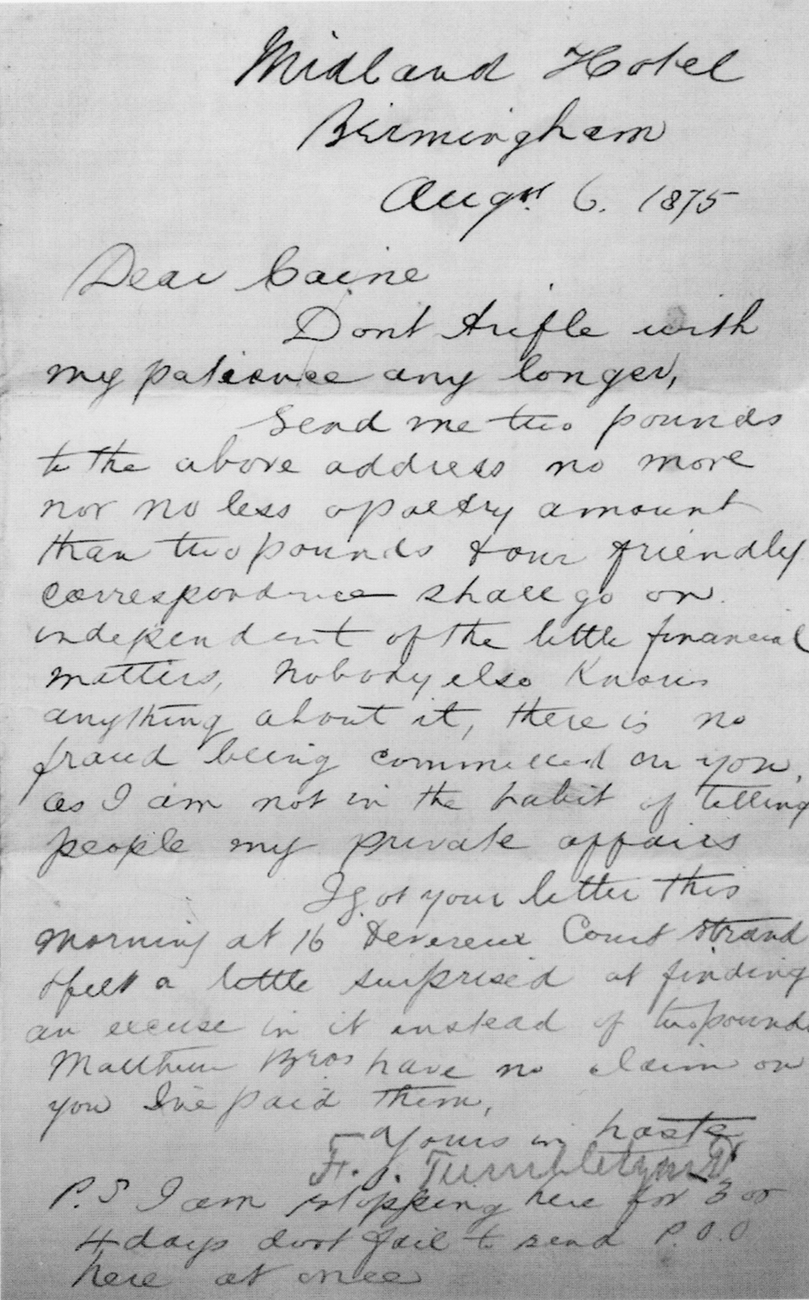

From London, Tumblety repeatedly asked Caine to be his traveling companion in America, invitations he diplomatically evaded. Meanwhile, Caine saw more and more of Tumblety’s darker side. When he balked at the propriety of a requested financial transaction, Tumblety exploded. “Don’t trifle with my patience any longer, send me two pounds & our friendly correspondence will go on independent of the little financial matter, nobody else knows anything about it, there is no fraud being committed on you, and I am not in the habit of telling people my private affairs.” Telegraphs were even less diplomatic: “Dear boy wire at once . . . wire forty wire wire wire wire wire wire.” Or the simple command, with the implicit, imperious understanding that it will not—cannot—be disobeyed: “Come here tomorrow evening. I must see you.”

One of Tumblety’s unctuous, ingratiating letters to Hall Caine. (Courtesy of Manx National Heritage)

The final piece of surviving correspondence from Tumblety to Caine is dated May 31, 1876, and was mailed from St. Louis. The racism and misogyny alone would have been ample cause for Caine to bring the relationship to an end. Writing of his recent experiences in the West, Tumblety rants about the country being overrun by “Asiatic hoards,” which he compares unfavorably to insects.

“Don’t trifle with my patience any longer.” When flattery failed, Tumblety turned imperious and demanding. (Courtesy of Manx National Heritage)

The chinamen are as nasty as Locust, they devour everything they come across, rats and cats, and all sorts of decomposed vegetable matter. . . . The Chinese that are now being landed on the Pacific shelf are of the lowest order. In morals and obscenity they are far below those of our most degraded prostitutes. Their women are bought and sold, for the usual purposes and they are used to decoy youths of the most tender age, into these dens, for the purpose of exhibiting their nude and disgusting persons to the hitherto innocent youth of the cities.

Tumblety, whose return to America somehow didn’t land him in jail, nonetheless grew restless and in time went back to England. As crime historians Stewart Evans and Paul Gainey describe it, “Travel for Tumblety was not a source of amusement or of intellectual enrichment; it was a disease. . . . There was no cure. For most of the rest of his life Tumblety was a man on the run. He behaved like a hunted fugitive even when the police had stopped looking for him. Indeed, he seemed almost to invite their attentions, relishing the role of an international outlaw.” He arrived at Liverpool in the summer of 1888, made his way to London, and secured lodgings in Batty Street in the East End, at the very epicenter of the murders. He drew the suspicion of investigators early in the case, but they only had evidence to charge him in an unrelated matter: acts of gross indecency with four men. He was in custody only a few days when he made bail, just before the Kelly murder. Perhaps knowing he was being trailed, the killer executed his gruesome pièce de résistance indoors. The next day Tumblety was arrested on suspicion of being the Ripper, but again there was no real evidence. It’s not surprising. Modern forensic tools were nonexistent; even fingerprinting would not enter into criminal investigations for another three years.

While awaiting trial on the sex charges, Tumblety broke bail, fled to France, and from there returned to New York City. The eviscerations in Whitechapel stopped. Acts of gross indecency were not extraditable offenses, and he had never been charged with anything else. Tumblety attracted widespread press attention and gave interviews complaining of his mistreatment at the hands of the incompetent London police force. By 1893 he was living again in Rochester, with his sister, and he died ten years later in St. Louis, a wealthy man.

A self-published, self-serving pamphlet showcasing Tumblety’s ability to attract and maintain public attention.

By late 1888 Stoker and Caine were fast friends, and it is inconceivable they didn’t discuss the Ripper, especially after Tumblety’s escape to America was extensively covered in the press. Even without a close connection to the case, everyone in London had something to say about what remains one of the most notorious crime sprees of all time. Scotland Yard was deeply embarrassed at letting Tumblety get away, and it is perhaps not surprising that the original dossier outlining their suspicions has never been found.

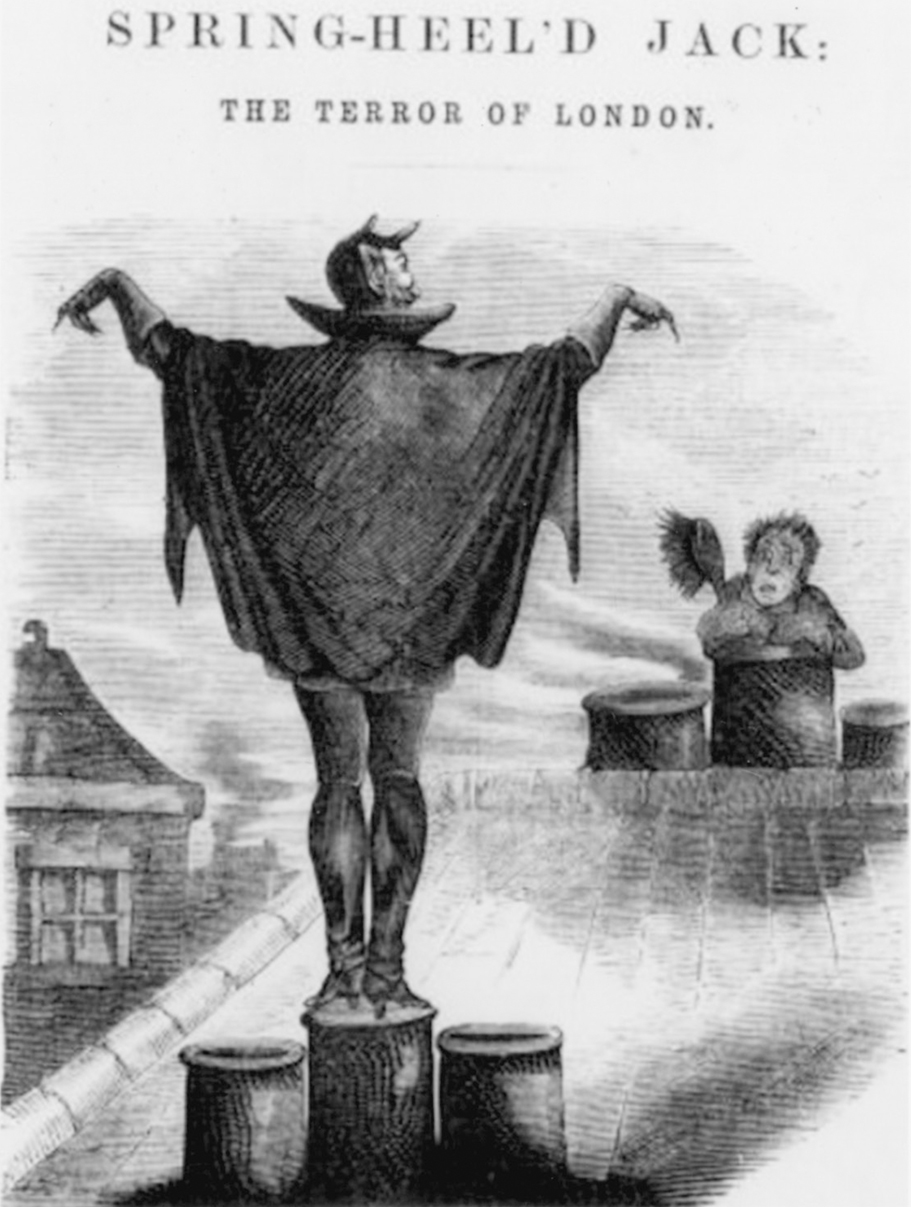

The idea that Jack the Ripper influenced Stoker’s creation of Dracula has been put forward a number of times. Certainly, the simple idea of a bloodletting monster at loose in Victorian London is suggestive enough. A terrifying entity known as Spring-Heeled Jack was a widespread urban legend in Victorian times that theoretically could have been the Ripper’s namesake and have given Stoker a few ideas as well.‡ Spring-Heeled Jack wore a batlike cloak, appeared out of nowhere, and disappeared just as quickly. He attacked women and men alike, had blazing red eyes, and was said to breathe blue fire. A popular penny-dreadful account of Jack’s exploits was serialized in 1886.

Spring-Heeled Jack was a frightening urban legend in Victorian England, which influenced the public’s response to Jack the Ripper, as well as its receptivity to Dracula.

The opening chapters of Dracula, in which Jonathan Harker is held prisoner in the castle, have often been interpreted as a conscious or unconscious representation of Stoker’s hostagelike relationship with Henry Irving, but he could have had Hall Caine’s personal incubus on his mind when he imagined a tall, thin man with a drooping mustache commanding Harker to write letters in a strange castle where women are banished monsters and the master of the house claims the male guest as his special tool and possession.

Few images of Francis Tumblety exist, but they all accentuate one feature: a prominent, overpowering mustache that nearly conceals his mouth. Stoker described Dracula as having a similar appearance.

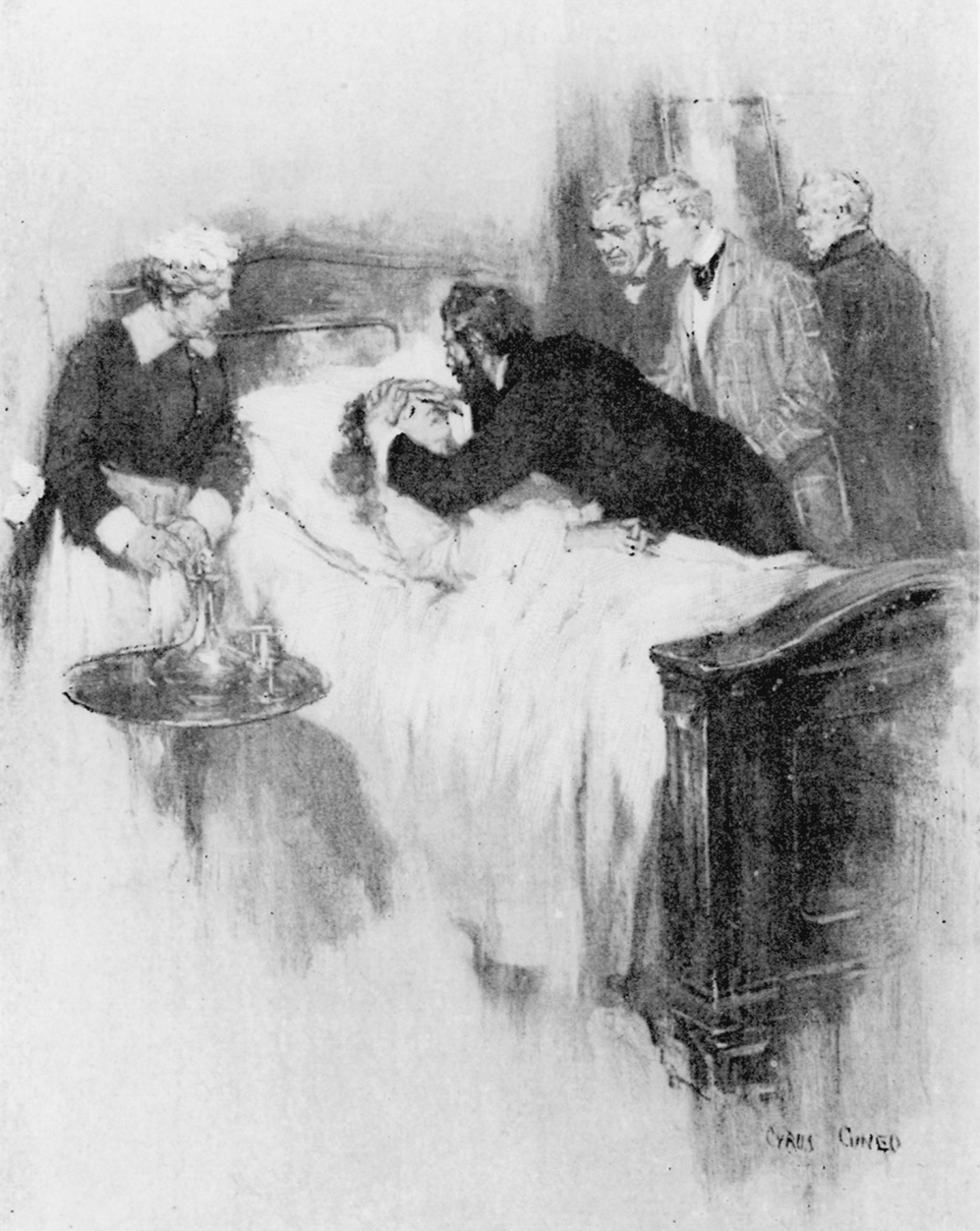

Stoker and Caine shared an interest in mesmerism, and Stoker could not have been unaware of a magazine serial his friend published around 1890, called Drink: A Love Story on a Great Question. Sixteen years later, it would be published as a slim illustrated book, the story unchanged. Heretofore, Drink has not been mentioned among the literary works having influenced Dracula, but the story has a striking number of similarities to Stoker’s novel, and Caine published it roughly the same year Stoker began his Dracula notes. Robert Harcourt (his surname a near-homonym for Harker) travels to the ancestral home of his fiancée, Miss Lucy (Clousedale, in place of Westenra) in the Cumbrian village of Cleaton Moor. En route, he receives ominous warnings about a family curse, which may be descending on Lucy, who has undergone a strange personality transformation. To his horror, Harcourt learns that his beloved suffers the terrible night-thirst of alcoholism, and discovers how she crawls out her window in disguise to seek shameful liquid sustenance in the village below. Confronted, Lucy admits her secret; because of her uncontrollable behavior brought on by polluted blood—her condition is indeed a hereditary, blood-based scourge—their marriage can never be. (At a similar point in Dracula, Mina fearfully renounces her own marriage: “Unclean! unclean! I must touch him or kiss him no more.”)

Harcourt makes the acquaintance of a French mesmerist, Professor La Mothe, who at “a place of popular entertainment” puts people into a blissful suspended animation for periods of a week or more. Although the sleep is peaceful, the trappings are macabre.

It was still an hour earlier than the time appointed for the experiment, but I found my way to the sleeper. He was kept in a small room apart, and lay in a casket, which at first sight suggested a coffin. There were raised platforms at either side, from which the spectator looked down at the man as into a grave. . . . I sat on a chair on the platform and looked down at the sleeper. And as I looked it seemed at last that it was not a strange man’s face I was gazing into, but the beautiful face that was the dearest to me in all the world. Suddenly a thought struck me that made me quiver from head to foot. What if Lucy could sleep through the days of her awful temptation? What if she could be put into a trance when the craving was coming upon her? Would she bridge over the time of the attack? Would she elude the fiend that was pursuing her?

After the performance, at the end of which the refreshed sleeper “vaulted” from the coffin, Harcourt visits the hypnotist in his dressing room. “Dr. La Mothe,” he asks, “has artificial sleep ever been used for the cure of intemperance?” Since La Mothe is a Parisian, Harcourt needs to repeat the question in French. “In the school of Nancy,” he says, “the cure of alcoholism by suggestion is not unknown.” Does he know the form of drinking mania in which the desire is periodical? “Certainly.” Harcourt then puts forth his thesis. “Do you think if a patient were put under artificial sleep when the period is approaching, and kept there as long as it is usual for it to last, the crave would be past and gone when the time came to awaken him?” La Mothe is startled and fascinated. “With a proper subject it might be—I cannot say—I think it would—I should like to try.”

Caine’s Drink advocated hypnosis for the treatment of alcoholism, but the technique was more often used for the control of “contrary sexual instinct.” (Courtesy of Manx National Heritage)

The mesmerist agrees to attend Lucy. Harcourt is overjoyed. “Is it too much to say that I went home that night with the swing and step of a man walking on the stars? If I had found a cure for the deadliest curse of humanity, if I had been about to wipe out the plague of all races, all nations, all climes, all ages, I could not have been more proud and confident. Hypnotism! Animal magnetism! Electro-biology! Call it what you will. To me it had one name only—sleep. Sleep, the healer, the soother, the comforter—.”

As an awe-inspiring if overcredulous fictional demonstration of hypnotic power, Caine’s story bore a surface resemblance to “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar.” Indeed, had he intended a perverse lampoon of Poe, upon awakening, poor Miss Lucy might easily have been reduced to a reeking puddle of gin. But mesmerism won the day, at least within the sunnier universe of Caine’s imagining, aided by a narrative structure drawn from classic wonder stories. Not unlike Sleeping Beauty or Snow White, Lucy wakens from her deathlike sleep free from the curse, ready and eager to marry the prince who brought her a cure. Caine describes drink itself as “the great hypnotizer,” but its awful power is banished and can no longer sap the maiden’s soul. George Cruikshank couldn’t have written a better fairy tale.

Illustration for Drink: Miss Lucy’s uncontrollable night-thirst yields readily to mesmeric suggestion. (Courtesy of Manx National Heritage)

Caine’s motivation for publishing Drink is puzzling, because there is nothing to suggest that he had personally struggled with alcohol. He had watched, of course, as Rossetti’s drug addiction was compounded by the alcohol he additionally drank to mask the taste of chloral hydrate, and his writer friend Wilkie Collins§ had a truly frightening capacity for laudanum. But Caine never advocated conventionally for temperance, on behalf of his friends or the public. When Drink was published, Caine received testimonials from several doctors, attesting to the efficacy of the pseudoscientific treatment. According to Stoker, the 1906 book version sold a hundred thousand copies, but no stampede to hypnotists followed. The public responded to it as melodramatic entertainment, not as medical advice.

Drink was an eccentric outlier among the many books advocating the medical use of hypnosis in the fin de siècle and early twentieth century. If alcohol is even mentioned in the literature, it is mentioned only rarely. The predominant application of hypnosis put forward by medical men, as opposed to novelists, was in the treatment of sexual complaints. In women, the problems inevitably rose from “hysteria,” that catchall condition encompassing everything from frigidity to nymphomania, and supposedly emanating from the uterus. In men, the issues centered largely on controlling masturbation and reversing “contrary sexual instinct.” Books like Therapeutic Suggestion in Psychopathia Sexualis (1895), by Dr. A. Von Schrenck-Notzing, were translated from German into English for medical professionals on both sides of the Atlantic. In America, the leading advocate was Dr. John D. Quackenbos of Columbia University—an occultist as well as a physician—who described his success in mesmerizing away “sexual perversions” as well as smoking, dishonesty, “dangerous delusions,” and “willfulness, disobedience, and untruthfulness in children.”

In 1899, he presented some of his case studies to the New Hampshire Medical Society. “A gentleman of twenty-five, occupying a position of great trust with one of our great life insurance companies, came to me, and wept with mortification as he recounted the story of his abnormal attachment to handsome young men,” wrote Quackenbos. “As he described it, nature had given him a woman’s brain.” Schrenck-Notzing borrowed language from Krafft-Ebing to describe such cases as “psychical hermaphrodites.” Quackenbos gave hypnotic suggestions to the young man that “portrayed ‘unnatural lust’ as moral, mental and financial ruin, and the results of a happy marriage were depicted as involving the greatest human happiness.”

After only a few treatments, the insurance agent “felt no longer drawn toward a fellow clerk who had previously caused him a great deal of trouble” and “was enabled to throw off the influence with comparative ease. The object of treatment to come will be to eradicate it completely.” Schrenck-Notzing recounted a more colorful patient. “In one case of complete effemination,” he wrote, hypnosis was followed by “an unmistakable weakening of feminine peculiarities. Powder and paint were no longer used; the pictures of urnings disappeared from the wall; the feminine articles of toilet were given away.”

Stoker had used alcohol euphemistically in his novelette The Primrose Path to work through his anxieties about what temptations might await a young man who leaves his Dublin wife and mother for a curiously all-male theatre world where actresses almost don’t exist. So, too, does Caine seem to be making an argument about something that doesn’t seem to really be the point, but a subject that could not be spoken about openly in commercial fiction of the 1890s. In Maurice, a novel written in 1913 but not published until 1971, E. M. Forster draws honestly from his own experience as a turn-of-the-century Oxford undergraduate. The title character, madly in love with a classmate, confesses to a conventional doctor that “I’m an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort” but receives no useful advice or information. He tries again with a hypnotist, Lasker Jones,¶ who gives him the suggestion to visualize the portrait of an imaginary beautiful woman and eroticize it. The session ends with Maurice in tears, and he has the good sense to abandon the treatments entirely and get on with the life he has, not the one he thinks he should have. According to the historian Graham Robb, in Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century, “These hypnotic cures sometimes lasted several years and more than 100 sessions. They were the Victorian equivalent of long-term, voluntary psychoanalysis. Their apparent popularity is understandable: the price of normality was always just out of reach, and the length, cost and futility of the treatment gave patients a good reason to feign success.” As Robb notes, “The idea that homosexuals were constitutional liars was usually set aside when they claimed to be cured.”

Caine’s biographer Vivien Allen notes that the Isle of Man was a small community, prone to small-town gossip. It was good that he married a decade before acquiring the turreted, faux-medieval island residence known as Greeba Castle; the odd circumstances behind the marriage would have truly set tongues wagging. Caine had been more or less blackmailed by the stepfather of a pregnant thirteen-year-old girl, Mary Chandler, to take her off his hands. Caine wasn’t the father, but the girl delivered meals to his rooms at Clement’s Inn, and he was friendly toward her. He was an easy target and yielded easily to pressure. Caine lied about Mary’s age, saw to her education, and let people assume they were married for several years. While he didn’t mind the comparisons to Shakespeare, he didn’t need to be likened to Edgar Allan Poe and his legendary child bride, Virginia Clemm. Caine and Mary had one child of their own out of wedlock before finally tying the knot in 1886. She was seventeen, but the marriage certificate said she was twenty-three. After they had a second child, their marriage became a largely companionate affair. Mary would never feel she was part of his real life, his literary life, and his obvious preference for the company of other men was a sore spot for decades. Eventually she would have her own house in London, on Hampstead Heath.

As the Caines’ frequent separations became more evident, Allen notes, the whole island suspected that Caine “was conducting a series of torrid love affairs, of which there is no evidence whatsoever, but many of the Manx—and some folk from further afield—thought Caine lived the love scenes and romances he wrote about. More sophisticated people noted the stream of male visitors to Greeba Castle when Mary was not present and drew other conclusions.” No one has ever suggested any physical intimacy between Stoker and Caine, and it is far easier to imagine them intimately and endlessly commiserating about their mutual attraction to men than actually doing anything about it. Caine, Stoker, Wilde, and many other youthful acolytes of Walt Whitman had, by the 1880s and 1890s, made their compromises with middle-class respectability and settled into marriage and parenthood, however problematic. The Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 had greatly expanded the range of homosexual behavior that could be prosecuted in England by only vaguely defining what constituted “gross indecency.” In this light, Stoker’s appeal to Whitman to censor his work begins to make some sense. Let there be two Walt Whitmans—a sanitized one for the masses, but, entrez nous, a more rarified and private understanding.

Hall Caine’s highly strung personality is well captured in a bug-eyed caricature for Vanity Fair.

The friendship between Bram Stoker and Hall Caine will forever be to some degree impenetrable because so many letters that should exist between them appear to no longer exist. It was not uncommon for “very private” Victorians to edit their lives for posterity by destroying their letters, but it is still the bane of biographers. One of the few appreciations of Stoker and his friendship was put to paper by Caine on the dedication page of his 1893 novel Cap’n Davy’s Honeymoon:

When in dark hours and in evil humours my bad angel has sometimes made me think that friendship as it used to be of old, friendship as we read of it in books, that friendship which is not a jilt sure to desert us, but a brother born to adversity as well as success, is now a lost quality, a forgotten virtue, a high partnership in fate degraded to a low traffic in self-interest, a mere league of pleasure and business, then my good angel for admonition or reproof has whispered the names of a little band of friends whose friendship is a deep stream that buoys me up and makes no noise; and often first among these names has been your own.

The upswing in Caine’s career buoyed both men, though neither could imagine that a decade later the sales of Caine’s books would be exceeded only by Dickens and Thackeray. In addition to assisting Caine, Stoker returned to work on his own languishing projects and began new ones. His first full-length novel, The Snake’s Pass, his only novel set in Ireland, appeared as a serial in 1889 and as a book in 1890.

Sharing in Caine’s productive energies stimulated his own creativity, and his mind was newly awash with ideas for stories. One was an especially strange dream fueled by the love of folklore and the supernatural he shared with his friend, as well as a storehouse of images and ideas dating to his babyhood: children spirited away by dark entities, revenants in haunted castles, mesmerism and deathlike sleep, shipwrecks, storms, and coffin-ships. The battle between science and religion—a fantastical dreamworld anchoring Darwin’s magical pantomime theatre, where animals could become human or slide back again. The fear that there might not be anything beyond death. And the even more terrifying possibility that there might. And above all there was the magic of blood, the mysteries of blood, the dangers of blood . . .

Out of the dream-maelstrom coalesced an archetypal, beckoning figure dressed completely in black. Tall, thin, waxen-faced, and cadaverous, it approached with a singularity of purpose, sweeping away three weird women with voluptuous red lips who bestowed their languorous kisses on the throat instead of the mouth. Old Count interferes—rage & fury diabolical—This man belongs to me I want him.

The Snake’s Pass (1890) was Stoker’s only novel with an Irish setting..

Bram Stoker, the boy who went away with the fairies and never completely returned, had finally been chosen by the Demon King himself to write Dracula.

* A spiny, yellow-flowered weed, prolific in Great Britain and France, where it is commonly used for burning; its bursting seed pods give off a crackling sound.

† A pair of devoted homebodies in an eighteenth-century poem.

‡ “Jack” was not a name invented by the police but first appeared in a gloating letter sent to a London newspaper, purportedly from the killer. It was signed “Yours truly, Jack the Ripper.”

§ Collins, whose seminal novel The Moonstone (1868) was a clever arrangement of diaries and letters, is generally believed to have inspired Stoker’s similar use of the epistolary technique in Dracula.

¶ Memorably played by Ben Kingsley in the Merchant Ivory film adaptation of 1987.