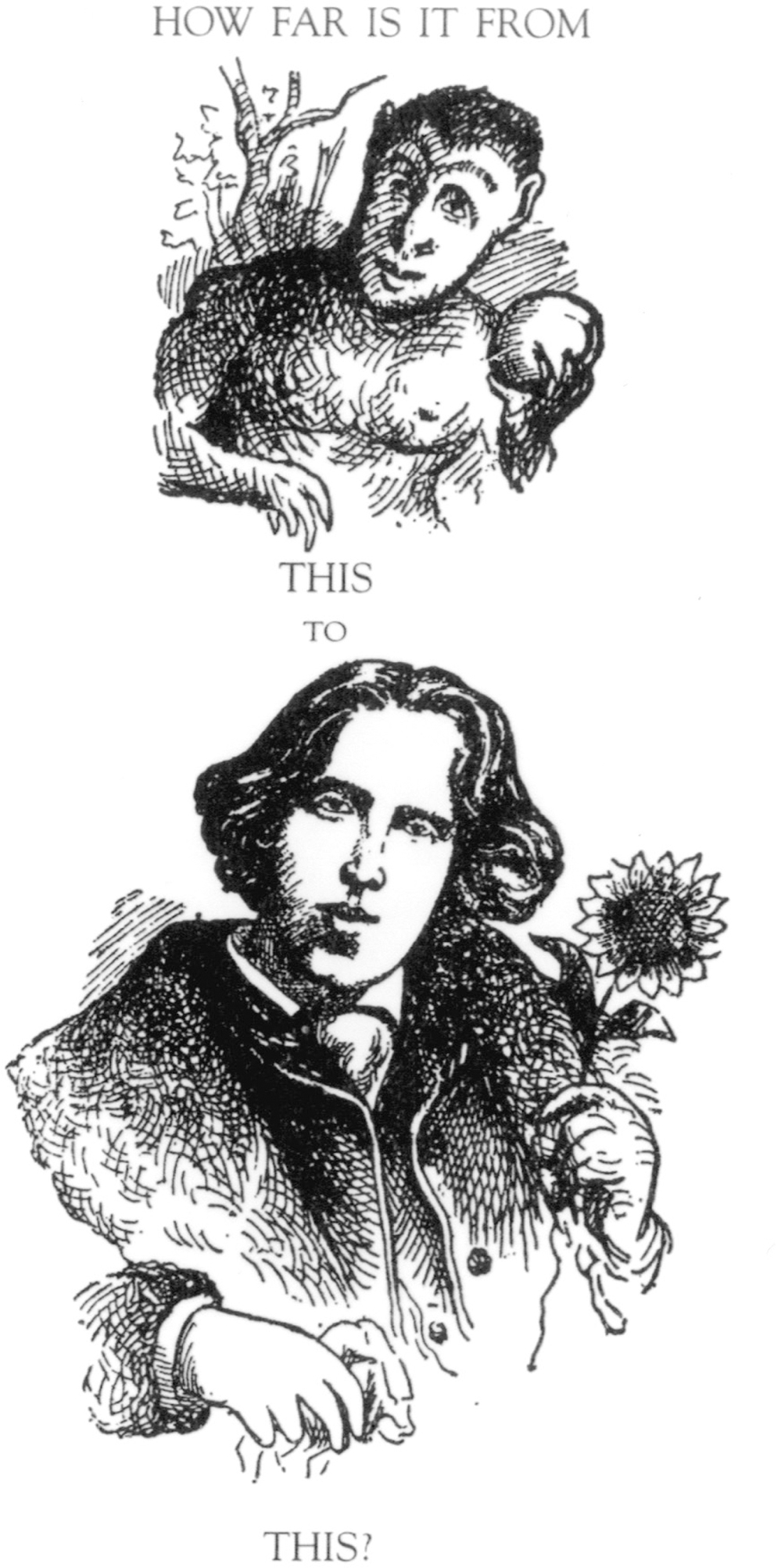

Frontispiece of Sabine Baring-Gould’s The Book of Were-Wolves (1865). (John Moore Library)

Frontispiece of Sabine Baring-Gould’s The Book of Were-Wolves (1865). (John Moore Library)

You go into the woods, where nothing’s clear,

Where witches, ghosts and wolves appear.

Into the woods and through the fear,

You have to take the journey.

— Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine, Into the Woods

There are many stories about how Bram Stoker came to write Dracula, but only some of them are true.

According to his son, Stoker always claimed the inspiration for the book came from a nightmare induced by “a too-generous helping of dressed crab at supper”—a dab of blarney the writer enjoyed dishing out when asked, but no one took seriously (it may sound too much like Ebenezer Scrooge, famously dismissing Marley’s ghost as “an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese”) But that hasn’t stopped the midnight snack of dressed crab from being served up as a matter of fact by countless people on countless occasions. While the nightmare aspect may well have some validity—Stoker’s notes at least suggest that the story might have had its genesis in a disturbing vision or reverie—it exemplifies the way truth, falsehood, and speculation have always conspired to distort Dracula scholarship. An unusually evocative piece of storytelling, Dracula has always excited more storytelling—both in its endlessly embellished dramatizations and in the similarly ornamented accounts of its own birth process.

Some Dracula creation myths are easier to believe because they contain partial truths, although they quickly begin to enable improbabilities and impossibilities. For example, it is an undisputed fact that Stoker spent at least seven years working on Dracula, from conception to publication, but this leads to a number of unsupported assumptions. First, that it was his masterwork largely because he spent seven years on it, and that the book is deservedly renowned for the endless care Stoker took in its crafting. Second, that a work span of seven years indicates, ipso facto, unusually painstaking and authoritative research, which uncovered, among other things, the grisly true story of a bloodthirsty fifteenth-century Wallachian warlord, Vlad Tepes˛, “the Impaler,” who was also known as Dracula. The name was not well known outside Romania, but Stoker would make it world-famous as the historical source and embodiment of the vampire mythos. In reality, Vlad’s connection to Stoker’s character was more fortuitous than inspirational, and the author’s research was surprisingly thin, but over time, and especially with the release of Francis Ford Coppola’s misleadingly titled film Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), Vlad’s story is now universally misunderstood as Stoker’s central source and impetus, and the novel itself as an overheated romance about Dracula’s quest over the centuries for the reincarnation of his long-lost love. The motif appears nowhere in Stoker’s book or his foundational notes.

Like the unending parade of dramatists and filmmakers who have not been able to resist tinkering and altering and “improving” his story, Stoker initially had trouble recognizing the essential elements that would make his tale click. The reason Dracula took seven years to write was that Stoker had great difficulty writing it, especially cutting through the overload of his own imaginative clutter. The process was twisted, arduous, and constantly interrupted. He stopped to write other books. He questioned himself. He censored himself. He had second, even third thoughts about almost everything.

In the end, he wondered if the book would even be remembered.

Apart from his long-standing interest in the occult, the best reason we can deduce for Stoker’s apparently sudden interest in writing an out-and-out supernatural novel at the end of the 1880s was his working association with Hall Caine. Since they had many discussions about legends of living death, demonic love, and life unnaturally prolonged as possible stage vehicles for Henry Irving, it is not surprising that Stoker began mulling over a similar theme. Caine may even have suggested a modern-day vampire adventure as something with a good chance for commercial success. Traditional Gothic novels were always set in the past, or at least stripped of the trappings of modernity. But what if the present was pitted against the past? No one had attempted such a thing, and there was a good chance it might catch the public’s fancy. The literary vampire canon then extant was fairly small, comprising familiar works like Polidori’s tale “The Vampyre,” wherein a vampire sets up shop in London society; Varney the Vampyre, the rambling penny dreadful serial in which key scenes in Dracula have obvious antecedents; Carmilla, of course; and the sometimes overlooked but nonetheless strong inspiration of the German short story “The Mysterious Stranger” (1844) by Karl von Wachsmann, best known from its anonymous English translation of 1854.

While we have no letters from Stoker to Caine asking for editorial advice on any of his books, since Caine was already highly successful and would soon be the best-selling British novelist of his time, Stoker would have taken any recommendation seriously. So perhaps their discussions of wandering Jews and demon lovers did stray into vampire country. We do know, at least, that the beginning of his professional relationship with Caine coincided with his own renewed determination to become a successful novelist. Around the time he began making notes for the yet-untitled vampire story, Stoker had finished and was in the process of publishing The Snake’s Pass, a straightforward romantic melodrama, well paced and still entertainingly readable. The villain is Black Murdock, a “gombeen man,” or shady moneylender, who wants to foreclose on a certain property because he knows something its cash-strapped owner does not: the land (situated on the pass to the sea through which St. Patrick drove out Ireland’s snakes) contains a hidden treasure. The property is also surrounded by a dangerous, all-engulfing peat bog, which catches up with Murdock when he ignores its perils in his greedy quest for gold.

Then the convulsion of the bog grew greater; it almost seemed as if some monstrous living thing was deep under the surface and writhing to escape. By this time Murdock’s house had sunk almost level with the bog. He had climbed on the thatched roof, and stood there looking towards us, and stretching forth his hands as though in supplication for help. For a while the superior size and buoyancy of the roof sustained it, but then it, too, began slowly to sink. Murdock knelt and clasped his hands in a frenzy of prayer. And then came a mighty roar and a gathering rush. The side of the hill below us seemed to burst. Murdock threw up his arms—we heard his wild cry as the roof of the house, and he with it, was in an instant sucked below the surface of the heaving mass.

The cataclysm strongly recalls the climax of Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” which Stoker admired and always thought might be an excellent basis for an opera. The image of a domicile being engulfed in geological turmoil was one he would revisit more than once in his writing.

Although work for Irving and Caine was already threatening to swallow Stoker himself up, in London, on Saturday, March 8, 1890, he found time to write the first of only two dated notes for the new novel’s plot.* A certain “Count——” in Styria, who wishes to buy property in England, has written the president of the Incorporated Law Society, who refers the matter to the solicitor Abraham Aaronson, who in turn selects an unnamed but “trustworthy” young lawyer who

is told to visit Castle—Munich Dead House—people on train knowing address dissuade him—met at station storm arrive old castle—left in courtyard driver disappears Count appears—describe old dead man made alive waxen colour dead dark eyes—what fire in them—not human—hell fire—Stay in castle. No one but old man but no pretence of being alone—old man in waking trance—Young man goes out sees girls one tries to kiss him not on lips but throat Old Count interferes—rage & fury diabolical—This man belongs to me I want him. A prisoner for a time . . .

The notes contain three separate references to the Old Count’s intention to possess his male visitor; in addition to the March 8 “This man belongs to me I want him,” a March 14 notation reads “Loneliness” followed by “the Kiss—‘This man belongs to me.’ ” When he begins to formally outline his chapters, he identifies Dracula’s brides as “the visitors,” followed by “is it a dream—woman stoops to kiss him—terror of death—suddenly Count turns her away—‘This man belongs to me.’ ” The importance of the line to Stoker is also evidenced in the novel’s final typescript, where the typist has mistakenly entered something other than the word “man” and Stoker has emphatically restored it—the largest, boldest single-word hand emendation in the final typesetter’s manuscript.

In the published book, Dracula additionally says to his wives, “Back, back to your own place! Your time is not yet come. Wait. Have patience. To-morrow night, to-morrow night is yours!” In the 1899 American edition, Stoker changed the last sentence, rather significantly, to “To-night is mine. To-morrow night is yours!” There can be no doubt that the Count intends to make a very personal claim on Harker. On the way to his room, Harker notes that “the last I saw of Count Dracula was his kissing his hand to me; with a red light of triumph in his eyes.” The Count has already told his wives that “when I am done with him you can kiss him at your will.” Dracula’s parting gesture—his own gloating kiss blown to the young man—makes his intentions fairly explicit. Christopher Craft, in his frequently cited essay “Kiss Me with Those Red Lips: Gender and Inversion in Dracula,” suggests that the whole novel “derives from Dracula’s hovering interest in Jonathan Harker; the sexual threat that this novel first evokes, manipulates, sustains but never finally represents is that Dracula will seduce, penetrate, drain another male.”

In the end Dracula never touches Harker—it is Harker who, searching for a key, touches the Count’s body, which is tumescent and blood-gorged, like a postmortem erection. Harker might as well be looking for the key to his own sexual ambivalence; his repulsion for the act is matched only by his compulsion to carry it out. “I shuddered as I bent over to touch him, and every sense in me revolted at the contact,” Harker writes in his journal, “but I had to search, or I was lost. The coming night might see my own body a banquet in a similar way to those horrid three.” Has he already forgotten the exquisite sexual thrill, the “languorous ecstasy,” he experienced during the vampire woman’s oral ministrations? Harker continues: “I felt all over the body, but no sign could I find of the key. Then I stopped and looked at the Count. There was a mocking smile on the bloated face which seemed to drive me mad.”

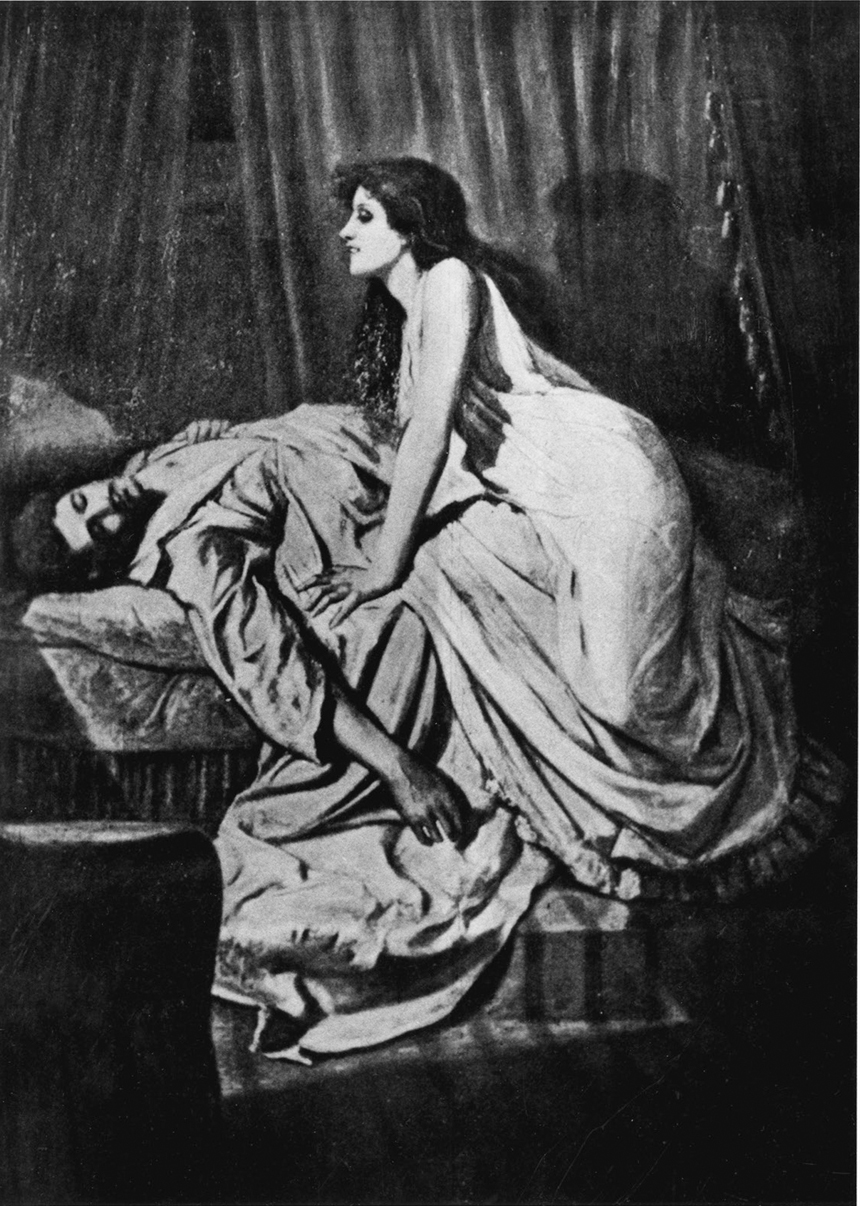

If the homoerotic dimensions of Dracula are largely subliminal, a matter of Stoker’s “unconscious cerebration” (the pre-Freudian term for involuntary thought processes operating beneath the level of awareness), several earlier works consciously presented vampires frankly attracted to the same sex. The lesbian intrigue of Le Fanu’s Carmilla is front and center, at least to modern readers, and almost certainly to Stoker. Karl Heinrich Ulrichs’s short story “Manor,” published in Germany in 1885, concerns the love of a dead sailor (the title character, turned into a vampire at the age of nineteen) for a younger boy who equally adores him. There is nothing at all malignant about Manor—Ulrichs was a pioneering crusader for homosexual rights—and the real villains are the townspeople who dig up the beach to locate his resting place and destroy him and his relationship. Ulrichs’s story was not translated into English during Stoker’s life, and he was unlikely to have even heard of it. Far more accessible to Stoker was Count Stanislaus Eric Stenbock’s “A True Tale of a Vampire,” included in his 1894 collection Studies in Death, which frankly equated vampirism with pederasty. The story opens with a clear reference to the setting of Carmilla: “Vampire stories are generally located in Styria; mine is also.” Stenbock was a well-known figure to literary London, if only because he pursued the grotesque with an almost religious fervor. Arthur Symons recalled him as “one of those extraordinary Slav creatures, who, after coming to settle down in London after half a lifetime spent in traveling, live in a bizarre, fantastic, feverish, eccentric, morbid and perverse fashion. . . . He was one of the most inhuman beings I have ever encountered; inhuman and abnormal; a degenerate, who had I know not how many vices.” In life, Stenbock seems to have preferred adult men over boys, but the monstrous Count Vardalek of “A True Tale” would have been perfectly at ease dragging children home in bags to satisfy his appetites.

Since Stoker’s time, vampires have reliably aligned themselves with changing fashions in sexual and social transgression. In folklore, simply existing outside the tribe in any discernable or annoying way could be enough to stoke suspicions of vampirism or witchcraft. The village idiot, the village drunk, the village whore—all were excellent candidates for supernatural scrutiny and scapegoating, especially when the crop failed, or mysterious illnesses transpired. Stoker told an interviewer that he had always been interested in the vampire legend, because “it touches both on mystery and fact.” He went on to explain how prescientific peoples might conjure vampires to explain poorly understood natural phenomena. “A person may have fallen into a death-like trance and been buried before the time. Afterwards the body may have been dug up and found alive, and from this a horror seized upon the people, and in their ignorance they imagined that a vampire was about.” Those prone to hysteria, “through excess of fear, might themselves fall into trances in the same way; and so the story grew that one vampire might enslave many others and make them like himself.”

Almost every culture has some variation of the myth of the hungry dead, and the rules by which these creatures are created and killed are so varied and diverse that no work of fiction could utilize them all and remain coherent or plausible, even taking into account a heavy dose of suspended disbelief. Stoker wisely steered clear of some of the more ludicrous beliefs (for instance, that vampires, seemingly driven by obsessive-compulsive disorder as much as by bloodlust, could be stopped by strewing poppy seeds in their path, which they would be compelled to individually count—a laborious process sure to last until dawn). In order to create at least a degree of believability, Stoker judiciously adapted the basics of vampirism as set forth in the accounts of eastern European vampire panics by the French biblical scholar Dom Augustin Calmet in Dissertations sur les apparitions des esprits et sur les vampires (1746, translated as The Phantom World in 1850). Here he found the time-honored methods of vampire disposal, actually used on suspicious corpses: a sharp stake through the heart, decapitation, and cremation. Variant methods included the removal of the heart rather than its staking. These were all physical measures taken against a physical threat. For the most part Stoker intended his vampires to be reanimated corpses, not (as some traditions held) the body’s astral projection of its ghostly double, which in its nocturnal wanderings collected blood that was somehow dematerialized and physically reconstituted in the grave-bound corpse. The 1888 edition of the Encyclopedia Brittanica presented this view, but Stoker went his own way; he retained the vampire’s power of dematerialization but never raised the conundrum of blood transport. He gave Dracula the ability to shapeshift into a bat (or batlike bird), a trait not found in folktales, and the additional ability to assume the form of a wolf, something he found in Sabine Baring-Gould’s The Book of Were-Wolves (1865). Baring-Gould described the Serbian vlkoslak, a vampire-werewolf hybrid, and related the Greek belief that werewolves became vampires after death. Stoker was sufficiently impressed by some of Baring-Gould’s descriptions of werewolf traits that he incorporated them almost verbatim into his description of Dracula. (Baring-Gould, for instance, says the werewolf’s “hands are broad, and his fingers short, and there are always some hairs in the hollow of his hand”; Dracula’s hands “are rather coarse—broad, with squat fingers. Strange to say, there were hairs in the centre of the palm.”) Baring-Gould also gave Stoker his descriptions of werewolf eyebrows meeting above the nose and sharp white teeth protruding over the lips. A blurred boundary between human and animal forms was especially resonant for late Victorian readers, still reeling from Darwin’s unsettling theories.

Since so many film adaptations of Dracula have depicted the vampire being incinerated by sunlight, readers are often surprised that in Stoker’s novel the Count walks the streets of London by day, unscathed, although his powers are diminished in the light. In folklore, the vampire, like other evil spirits, retreats into hiding by day but is never destroyed by the sun. This particular vulnerability made its first appearance in F. W. Murnau’s unauthorized Dracula adaptation, the German Expressionist classic Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu: A Symphony of Terror) in 1922. Stoker discovered the curious word nosferatu in Emily Gerard’s 1885 essay “Transylvanian Superstitions,” which first appeared in the journal The Nineteenth Century and was later included in her book The Land beyond the Forest (the title refers to Transylvania’s literal meaning, “across the forest”). Although she claimed the word as the Romanian term for vampire, nosferatu appears in no Romanian dictionary, or any dictionary in any language. To date, it has been found in only two other published sources, a German account of Transylvanian traditions published in 1865 by Wilhelm Schmidt, and an 1896 article by the Hungarian-Romanian folklorist Heinrich von Wlislocki, in which it appears in the variant, capitalized form Nosferat, describing an illegitimate child of illegitimate parents, who becomes a bloodsucking spirit. The word’s elusive etymology has prompted numerous origin theories, none completely convincing.†

Folklorist Emily Gerard.

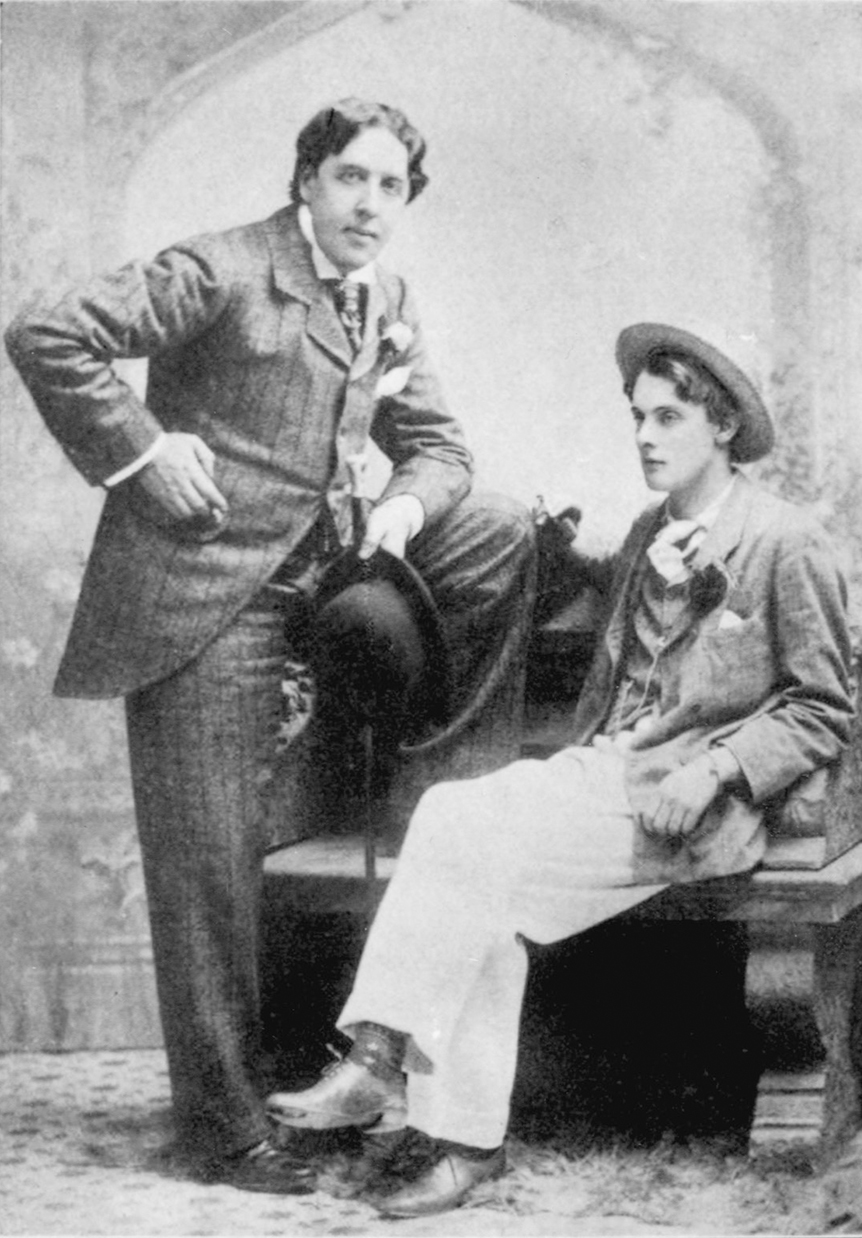

At roughly the same time Stoker made his earliest notes, Oscar Wilde delivered a handwritten manuscript of his own horror story to Miss Dickens’s Type Writing Office, just a block away from the Lyceum on Wellington Street. Ethel Dickens (granddaughter of Charles) would produce the typescript for the first version of Wilde’s only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which appeared in the July 1890 issue of Lippincott’s Magazine, an American periodical distributed simultaneously in England.

The title character is a privileged young man “of extraordinary personal beauty.” His portrait has been painted by a society artist, Basil Hallward, whose admiration of his model borders on obsession. The portrait’s subject, however, has an unexpected reaction to the canvas. “How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrible, and dreadful. But this picture will remain always young,” Dorian pouts. “If only it were the other way! If it were I who was to be always young, and the picture that was to grow old! For that—for that—I would give everything! Yes, there is nothing in the whole world I would not give! I would give my soul for that!” There is a convenient stand-in for Mephistopheles at hand, Lord Henry Wotton, who doesn’t directly broker the deal but tacitly approves Dorian’s descent into darkness with an engulfing tsunami of cynical epigrams. (“The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick.”) Wilde saw himself in all three characters: “Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry what the world thinks me: Dorian is what I would like to be.” There is also more than a hint of Frank Miles in the doomed, fictional Hallward; both painters are killed, in their own ways, in the pursuit of masculine beauty.

The Picture of Dorian Gray caused a furor when it first appeared in the July 1890 edition of Lippincott’s Magazine.

As Dorian retains his youth, the painting begins to show signs of both age and moral corruption, until at last it resembles a hideous, ancient satyr and has to be shut away in an attic room. Meanwhile, Dorian callously drives an actress who loves him to suicide, but mostly he ruins the lives and reputations of other males. “Why is your friendship so fatal to young men?” Basil demands, after he has aged eighteen years and Dorian none at all. “There was that wretched boy in the Guards who committed suicide. You were his friend. There was Sir Henry Ashton, who had to leave England, with a tarnished name. You and he were inseparable. What about Adrian Singleton, and his dreadful end?” The list goes on and on. Like a vampire, Dorian feeds on the lives of others to maintain his unnatural existence. When Basil Hallward finally discovers the secret of the painting, its original beauty eaten away by “the leprosies of sin,” he begs Dorian to pray with him for mutual forgiveness. “The rotting of a corpse in a watery grave was not so fearful” as the cursed, corrupted painting he had created. Instead Dorian stabs the artist to death and arranges for his corpse to be destroyed by acid.

In the end he has covered all his crimes. The painting is the only witness. In a final frenzy, he stabs the canvas, somehow imagining the act will set him free. It does, but not in the way he hoped. The painting returns to its unblemished state, and Dorian lies dead before it with the knife in his own heart, “withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage.”

The critical reaction to Dorian Gray was swift and savage. The London Daily Chronicle’s notice amounted to a neat distillation of the general outrage that descended on the book. “It is a tale spawned from the leprous literature of the French Décadents—a poisonous book, the atmosphere of which is heavy with the mephitic odours of moral and spiritual putrefaction—a gloating study of the mental and physical corruption of a fresh, fair and golden youth, which might be horrible and fascinating but for its effeminate frivolity, its studied insincerity, its theatrical cynicism, its tawdry mysticism, its flippant philosophisings, and the contaminating trail of garish vulgarity.”

The New York Times Sunday correspondent reported how Dorian Gray “had monopolized the attention of Londoners who talk about books. It must have excited vastly more interest here than in America simply because [of] last year’s exposure of what were euphemistically styled the West End scandals.” Also called the Cleveland Street affair, the scandals were a series of trials involving sensational charges against high government officials for covering up a male brothel in Cleveland Street, which procured telegraph boys for wealthy and aristocratic clients. As the Times correspondent explained, “Englishmen have been abnormally sensitive to the faintest suggestion of pruriency in the direction of friendships. Very likely this bestial suspicion did not cross the mind of one American reader out of ten thousand, but the whole town here leaped at it with avidity.”

(top and bottom) The artist Majeska illustrated Horace Liveright’s 1932 deluxe edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

For most of August 1890, Bram, Florence, and Noel vacationed in the picturesque fishing village of Whitby, North Yorkshire. Vacation may not be the best word to ever describe Bram’s time away from the Lyceum, for as usual he was still preoccupied with work—his writing—and he spent uncounted hours taking notes from books at the local museum and subscription library. It is not inconceivable that Whitby was chosen for the holiday because Bram had already decided it might make an ideal location in his novel, the English port of entry for his still unnamed vampire menace; he had first chosen Dover, then wisely reconsidered. Whitby provided a more surreptitious route, and considerably more atmosphere. Stoker came alone to Whitby for the first week, and it was therefore likely that he did the bulk of his research and note taking then. Not far from the guesthouse was the storefront studio of a local photographer, Frank Sutcliffe, who sold prints and postcards of Whitby and environs. His sepia-toned views of the abbey and the adjacent church and cemetery overlooking the sea were especially striking, but the Sutcliffe photo that commanded Stoker’s attention depicted the dramatically beached wreck of the Russian schooner Dmitry, run ashore in Whitby on October 24, 1885. (Henry Irving was in rehearsals for Faust at the time.) His curiosity piqued, Stoker sought out and had a conversation with a Coast Guard boatman, William Petherick, who gave him details on various wrecks, including the Dmitry, and seems to have transcribed a complete account of the incident from official records and given it to Stoker. If the idea of Count Dracula arriving via a deliberate shipwreck, instead of merely by sea, had never occurred to him before, it did now. He only slightly disguised the name of his fictional vessel, the Demeter.

The ruins of Whitby Abbey, photographed by Frank Sutcliffe in the 1880s.

Whitby’s harbor is situated at the mouth of the River Esk, which divides the town into two promontories, east and west. The Stokers stayed at an ideally located guest house at 6 West Crescent owned by a Mrs. Veazy, with an excellent view of both the harbor and the east cliff dominated by the imposing ruins of Whitby Abbey, founded in 1078 on the site of an original monastery dating to the year 657 and destroyed by Viking invaders in the late ninth century. The ghost of its medieval abbess, Saint Hilda, was believed to haunt its empty windows and is mentioned in passing by Mina Harker in Dracula.

Stoker was fascinated with the wreck of the Russian schooner Dimitri near Whitby in 1885. His name for the vampire-haunted ship in Dracula was the Demeter.

Max Schreck, the first screen Dracula, takes to the sea in F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922).

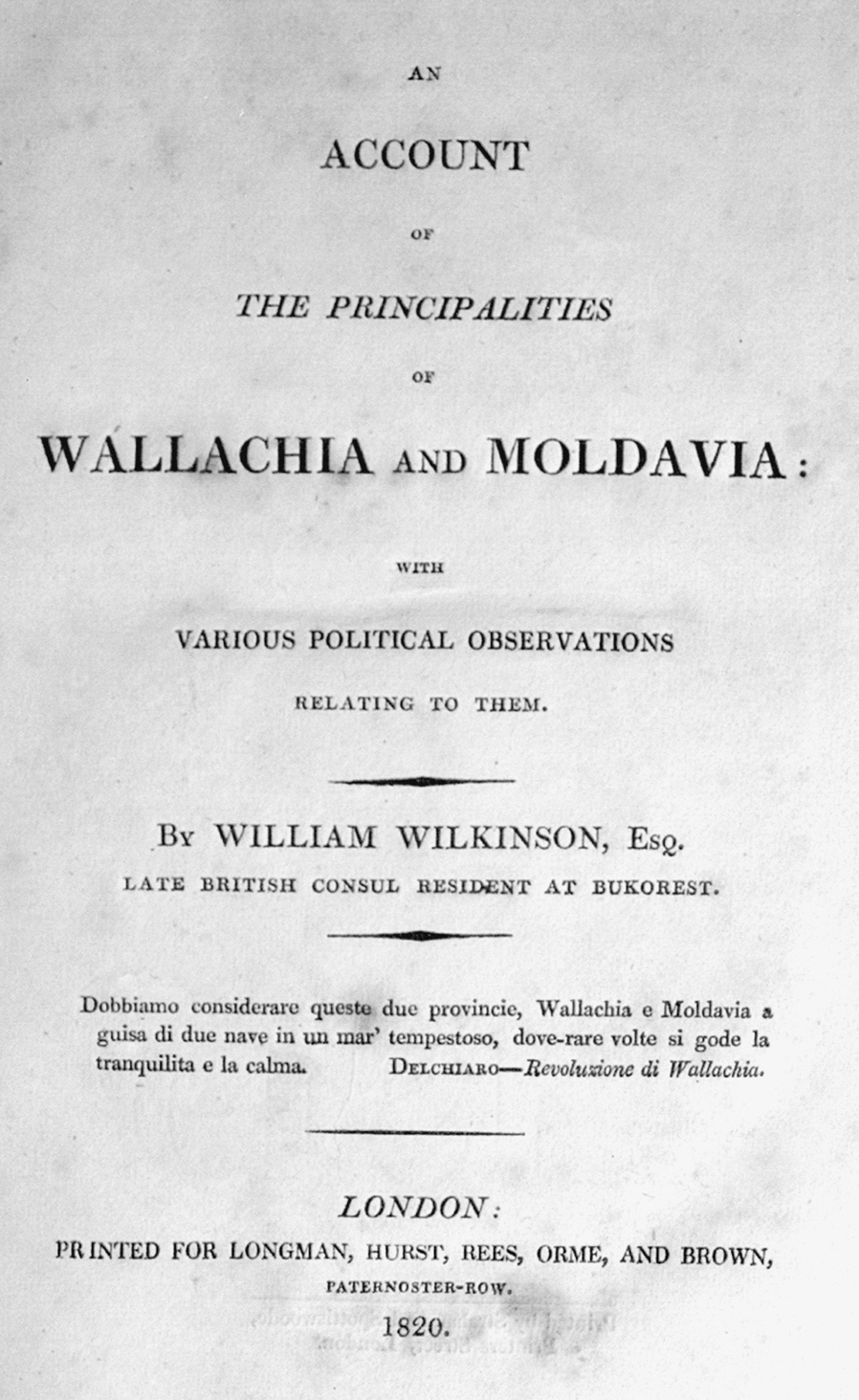

In addition to a location, Whitby afforded Stoker some of his most profitable research. It was his only known visit to the town, and he made the most of it. At the Whitby Museum, he found a glossary of Whitby localisms, a good number of which found their way into his finished book. The museum building also held the Whitby Subscription Library, where he requested an 1820 volume by William Wilkinson, An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia: with Various Political Observations Related to Them. In this book Stoker momentously encountered the name “Dracula,” the sobriquet given to the Wallachian warlord Vlad Tepes˛ (1431–76), legendary for protecting the region from Turkish invasion, and a folk hero in Romania to this day. Stoker paraphrased Wilkinson in his notes and added emphatic capitalization: “DRACULA in Wallachian language means DEVIL. Wallachians were accustomed to give it as a surname to any person who rendered himself conspicuous by courage, cruel action, or cunning.”

Wilkinson erred slightly. “Dracula” in Romanian means “Son of the Devil” or “Son of the Dragon”; Vlad’s father was called “Dracul,” which means both “devil” and “dragon.” There is no evidence Stoker was aware of the warlord’s reputation as Vlad the Impaler, so-called for his favorite and extraordinarily sadistic method of dispatching enemies. On one particularly atrocious occasion, twenty thousand Turkish captives were exterminated in this manner and displayed in a mile-long semicircle outside the capital city of Târgovs˛te. It is nothing but a gruesome coincidence that stakes are also used to kill vampires. And there is no documentation that Stoker ever came across a German pamphlet describing Dracula dining beneath his writhing victims and dipping his bread in their blood. But, since wooden stakes and blood were highly suggestive of vampires, enthusiastic modern scholars have repeatedly asserted that Stoker was far more knowledgeable about Vlad than he actually was, even maintaining that the historical Dracula was the primary inspiration for the fictional one. This is patently untrue; Stoker’s notes show that the book had taken considerable shape in his mind before he struck out his first idea for his monstrous villain’s name—the all-too-obvious “Count Wampyr”—and replaced it with the three crackling, undulating syllables that would forever define the idea of vampirism in the public mind. Professor Van Helsing, enumerating historical documents, notes that “in one manuscript this very Dracula is spoken of as ‘wampyr,’ which we all understand too well.” This is Stoker’s invention; there has been found no manuscript or historical book in any language using the German word for “vampire” in connection with Vlad.

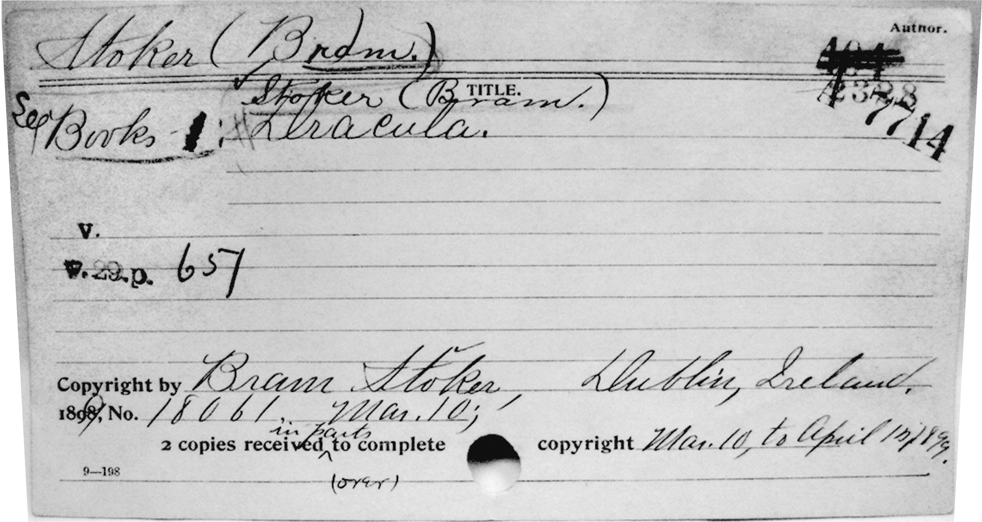

top and bottom Bram Stoker discovered the name “Dracula” in this book, which he found at the Whitby Susbcription Library while on holiday. (John Moore Library)

If Stoker hadn’t taken Lippincott’s Magazine with him to Whitby, he certainly carried the imprint of Dorian Gray in his mind. The firestorm of moral outrage at the book already threatened to make Stoker’s concept of Dracula as an archetypal Gothic novel villain problematic at best. Dorian Gray’s sins, never explicitly identified, paled before the lurid transgressions described in meticulous detail in Gothic novels like The Monk and The Italian. These villains, whose hawklike profiles and blazing eyes made them perfect physical templates for Dracula, were also unashamed sexual predators, their overt, libidinous behavior exceeding anything even hinted at by Wilde. Stoker’s notes indicated Dracula’s power to implant “immoral thoughts” in his victims, and this idea of moral pollution was precisely what critics objected to in Dorian Gray.

Stoker’s first instinct may have been to increase his cast of characters, the better to distract the reader from thinking about matters that were increasingly unspeakable. And so an early page of notes headed “Dramatis Personae” contains a painter, Francis A. Aytown; a “Deaf Mute Woman” and “Silent Man,” both servants to the Count; an unnamed “Texas inventor;” a detective named Cotford; a “Psychical Research Agent” named Alfred Singleton; and a “German Professor,” Max Windshoeffel. These last three seem to have been merged later into one character, the vampire hunter Abraham Van Helsing. It is interesting indeed that Stoker named a discarded preliminary character “Adrian Singleton,” more than slightly similar to Wilde’s “Alfred Singleton.” In Dorian Gray he is one of the title character’s victims, a degraded denizen of a vice den. It is exactly the kind of place Hall Caine described disapprovingly in Drink and claimed to have personally visited—purely in the interest of research, of course. Perhaps Stoker accompanied him.

People have long sought a specific real-world model for Dracula, a part most frequently assigned to Henry Irving, but other candidates have been nominated, some of them less than convincingly. The elderly Franz Liszt visited the Lyceum, and he was a dramatic-looking old man who had composed “The Mephisto Waltz.” (To paraphrase Tennessee Williams, sometimes there was Dracula—so quickly!) Slightly better nominees for Stoker’s prototype have included the Greek-born French actor Jacques Damala, Sarah Bernhardt’s husband at the time she was in London as Irving’s guest in 1882. According to Stoker, the twenty-seven-year-old morphine addict “looked like a dead man. I sat next to him at supper and the idea that he was dead came strong on me. I think he had taken some mighty dose of opium, for he moved and spoke like a man in a dream. His eyes, staring out of his white waxen face, seemed hardly the eyes of the living.”

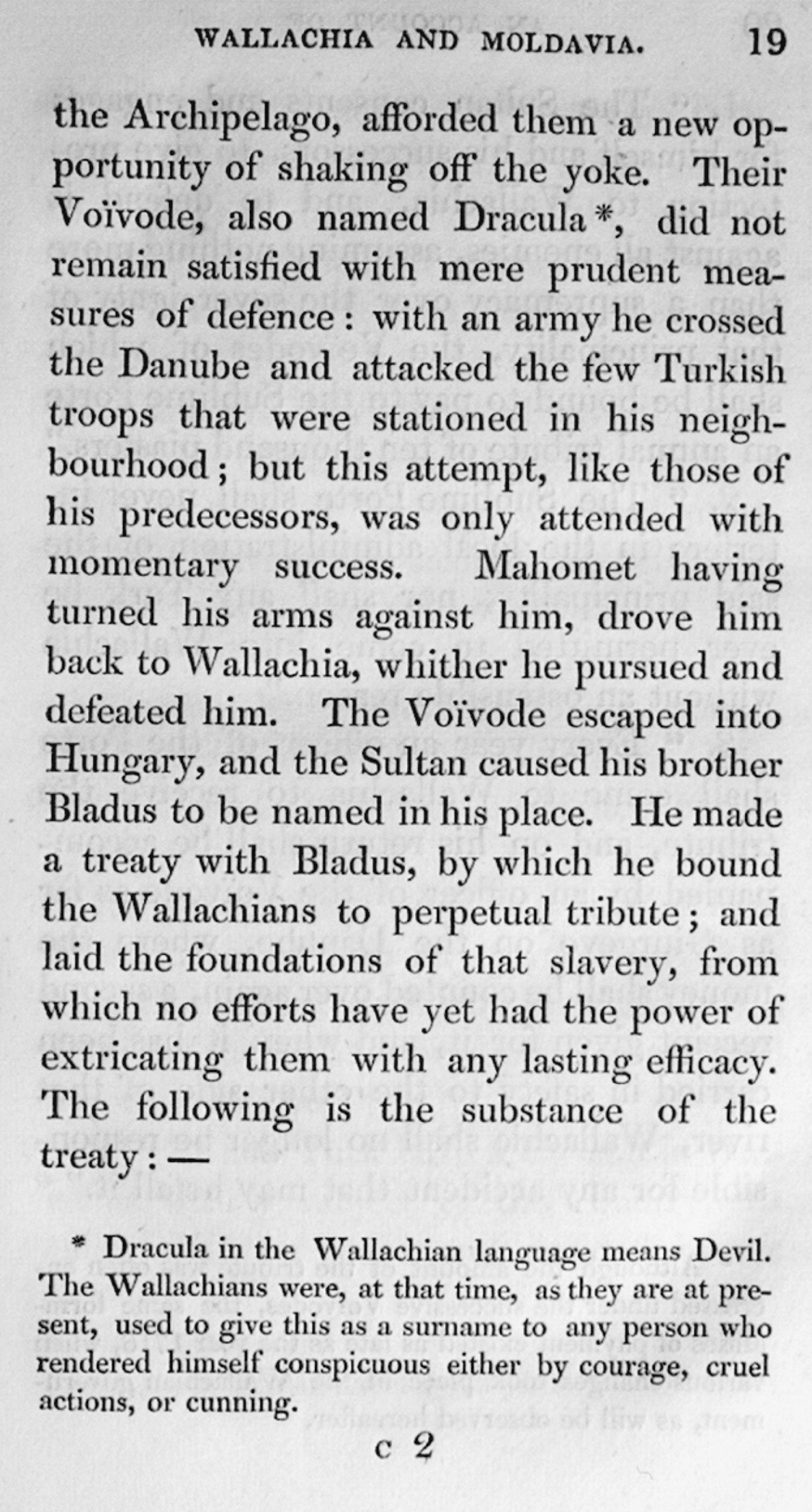

In seven more years Damala would indeed be dead, from the effects of morphine mixed with cocaine. But that night in 1882 during which she entranced Stoker, the Divine Sarah herself might have been actively auditioning for the role of Lucy Westenra, or at least one of Dracula’s Transylvanian brides. In Paris, she had just posed for a series of photographic souvenir postcards showing her sleeping in a coffin. The public had come to expect her dying onstage—her signature roles were tragic heroines, often suicides, including the likes of Phèdre, Cleopatra, Lady Macbeth, and Tosca. The coffin photograph was an inspired publicity ploy, trading on the popularity of Victorian postmortem photography, but also serving another ritual function. At thirty-eight she was precariously close to the dreaded “certain age” of forty. The coffin photo was Bernhardt’s Dorian Gray portrait in reverse, allowing her to freeze her beauty, stage-manage her “funeral,” and have her own last laugh on mortality .

The spectre of aging haunted Victorians almost as much as death. In Aging by the Book: The Emergence of Midlife in Victorian Britain, the historian Kay Heath notes, “The fin-de-siècle preoccupation with degeneration in individuals and the general population also increased age anxiety. Age itself could be considered definitive evidence of degeneration as the human body began to dissolve before one’s eyes, a miniature version of the regression of the populace which was becoming feared.” Bernhardt had been consumptive, or was thought to have been, in her teens. While she mysteriously outgrew her bloody cough, an aura of deathliness still clung to her, and she consciously cultivated it for public attention. A talented sculptress, Benrhardt modeled a bronze inkwell incorporating her own sphinxlike head flanked by bat wings. She was also said to have worn a stuffed bat as a fashion accessory.

While Bernhardt’s eccentricities were morbid enough, her ghoulishness never prompted public objection, perhaps because the unhealthy sexual overtones weren’t sufficiently pronounced. But on March 13, 1891, almost exactly a year after Stoker made his first notes for Dracula, London experienced its worst eruption of censorship hysteria since Dorian Gray when the first English performance of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts, denied a public license by the Lord Chamberlain, was given a legal but private performance at the Royalty Theatre, Soho. The critic William Archer, recounting the event for the Fortnightly Review, recorded “a few of the choice epithets” the press had hurled at the Norwegian play: “Abominable, disgusting, bestial, fetid, loathsome, putrid, crapulous, offensive, scandalous, repulsive, revolting, blasphemous, abhorrent, degrading, unwholesome, sordid, foul, filthy, malodorous, noisome. Several of the critics shouted for the police.”

Sarah Bernhardt, in one of her celebrated coffin portraits, sold as souvenir postcards to morbid admirers. Since so many of Bernhardt’s most famous roles were tragic, audiences expected to see her die onstage.

The story recounted the horrible choice faced by the long-suffering Mrs. Aveling, whose husband has finally died from his endless dissipations, when her grown son, Osvald, returns with the news that he has been diagnosed with a hereditary “softening of the brain”—that is, advanced syphilis. He pleads with his mother to take the life she has given by mercifully administering an overdose of morphine. The play ends with the mother’s horrible choice hanging unresolved, forcing the audience to make a decision of its own. In Dracula, the mercy-killing theme is raised when Mina secures the promise from her protectors to take all appropriate steps if vampirism engulfs her.

The Sporting and Dramatic News claimed that “ninety-seven percent of the people who go to see Ghosts are nasty-minded people who find the discussion of nasty subjects to their taste, in exact proportion to their nastiness.” The Daily Telegraph called Ghosts an “open drain,” a “sore unbandaged,” and “a dirty act done publicly.” The periodical Truth decried the private audience as a pack of “muck-ferreting dogs” and seemed to have Oscar Wilde and other transgressive company in mind when they decried the (assumed) appeal of Ghosts to “effeminate men and male women,” the “socialistic and the sexless,” and, heaping on some gratuitous misogyny, “unwomanly women, the unsexed females, the whole army of unprepossessing cranks in petticoats. All of them—men and women alike—know that they are doing not only a nasty but an illegal thing.”

Stoker needn’t have seen the performance; just reading the reviews and letters to the editor may have prompted him to ask himself if it was really the right time to resurrect an archetypal Gothic villain, his moral outrages made all the worse by way of vampirism, and drop him down into a modern London, especially this modern London, where a reactionary moral crusade was taking hold. Apropos of Ghosts, The Picture of Dorian Gray reads today as an almost transparent syphilis parable, an interpretation first put forth by Wilde’s preeminent biographer, Richard Ellman. Stoker may have dialed back a full elaboration of his vampire’s sins, but Dracula would also contain a discernible allegory of syphilis as its characters, terrified of a blood-borne contagion, obsessively examine the skin for telltale lesions, with pseudoscientific cures like garlic wreaths and wolfbane sprigs in lieu of mercury treatments and “blood purifiers.”

As depicted in the 1945 MGM film version, Dorian’s portrait was a perfect picture of syphilitic corruption.

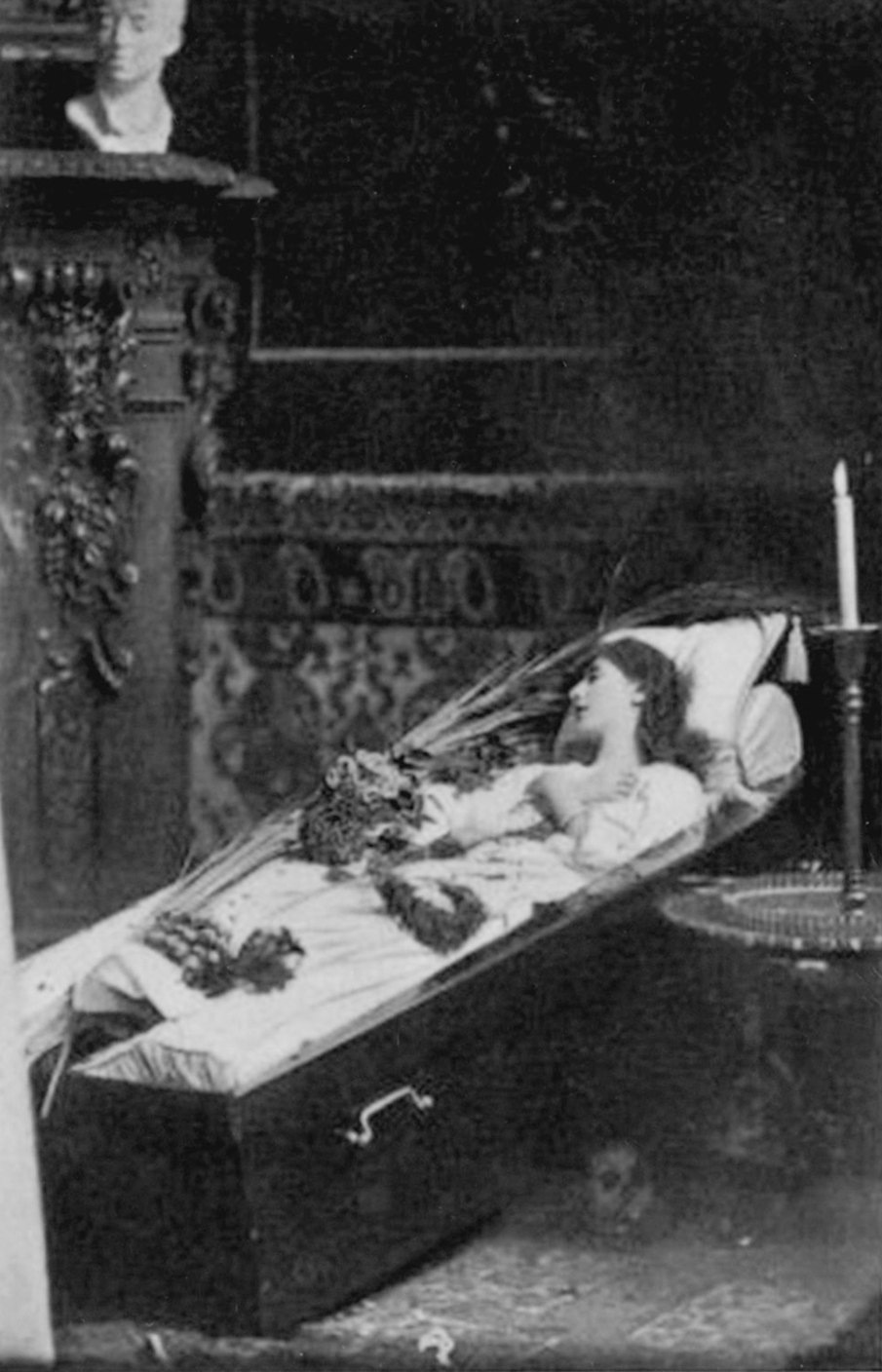

The first of two documented social encounters between the creators of Dorian Gray and Dracula, at least during the developmental stages of Stoker’s book, took place in 1889. Wilde had written a note to Stoker: “My dear Bram—my wife is not very well and has gone to Brighton for ten days rest, but I will be very happy to come to supper on the 26th myself. Sincerely yours, Oscar Wilde.” He had been accepting many social invitations on his own, and his wife’s illness may have been, in part, a reaction to the stress of their leading increasingly separate lives. Since the birth of their sons, Constance Wilde had had to cope with an increasing parade of attractive young men at Tite Street, apparently blind to the extent of Oscar’s involvement with them. One, Robbie Ross, is thought to have been his first extramarital male lover. (The idea, put forth in earlier biographies, that he was Oscar’s first male lover, period, today seems rather quaint.) Robbie remained a close family friend to the very end. But Constance’s denial was so deep she confided to a friend that she was struggling with feelings of jealousy for a woman she suspected might be her husband’s mistress. And she doesn’t seem to have suspected anything about another frequent visitor, Lord Alfred Douglas, the son of John Sholto Douglas, the Marquess of Queensberry. Pale, blond, and strikingly beautiful, Alfred—more familiarly known by his childhood nickname, “Bosie”—was a twenty-one -year-old Oxonian and a budding poet of some talent.

The supper to which Wilde had been invited by Stoker would have been held in the Lyceum’s Beefsteak Room, one of its paneled walls then dominated by John Singer Sargent’s life-sized canvas of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth. Some of Frank Miles’s landscapes also hung there, even as the artist was dying in an asylum, very much in the same wretched manner described by Ibsen in Ghosts. Miles would finally succumb to brain syphilis in July 1891.

With the Banquo-like presence of the doomed artist hovering in the air, what literary matters might have been discussed that night? The year of 1889 would culminate in Wilde’s outpouring of Dorian Gray, and Stoker, no doubt, was at least beginning to mull over the possibilities of literary vampires. Irving had not yet given up the idea of resurrecting the living-dead Vanderdecken. If the conversation turned to such matters, Wilde’s thoughts about vampirism would have been fascinating to know. He would have been quick to notice the inherent paradoxes of being simultaneously dead and alive, and could anyone have better encapsulated the transgressive erotics? The subject lends itself easily to an imagined, wickedly Wildean epigram: “The vampire’s mouth—such an ambiguous orifice! So soft and sensual, yet so hard and penetrating . . .”

Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas.

Stoker may well have been reading Wilde’s poetry as well as Dorian Gray in preparation for Dracula. In his opening chapter, upon glimpsing the sharp-toothed coachman who meets Jonathan Harker at the Borgo Pass, a fellow traveler nervously whispers, “Denn die Todten reiten schnell,” a slight misquote of a line from Gottfried Bürger’s death-and-the-maiden ballad “Lenore” (1774), famously and accurately translated as “For the dead ride fast” by the American romantic poet James Russell Lowell in 1846. Though “Denn” does not appear in Bürger, Stoker translates the line as “For the dead travel fast,” as if taking a cue from Wilde’s poem “Fabien dei Franchi,” dedicated in 1882 “To my friend Henry Irving” and named after one of the actor’s dual roles in The Corsican Brothers: “The dead that travel fast, the opening door / The murdered brother rising through the floor.” Stoker certainly knew Wilde’s poem—it was too cloyingly flattering to Irving for anyone to forget. Because of the fame of Dracula, the line from Bürger’s ballad is now almost always quoted in English the way Wilde and Stoker, and not James Russell Lowell, chose to present it.

The next time we can place Wilde and Stoker in the same room is three years later, at the West End debut of Oscar’s Lady Windermere’s Fan, his first theatrical success. The play is a sparking comedy of manners about a young wife confronting the possibility that her husband has been leading a double life. The presumed dalliance is ultimately revealed to be harmless, but the theme reflected Constance Wilde’s anxieties about the state of her marriage that could not be explained away. Her husband would spend more and more time with Bosie, often in hotels, and later with lower-class rent boys, for whom Bosie had a special appreciation.

According to Wilde biographer Neil McKenna, “The audience on that memorable night of Lady Windermere’s Fan constituted an emotional and sexual autobiography for Oscar. There were lovers past, present and even future seated in the auditorium.” Bosie, along with Bram and Florence Stoker, and a host of celebrities, attended the premiere. Oscar had ordered a dozen or so carnations dyed a bright green and distributed them among selected friends. The actor Ben Webster, playing an epigram-spouting, Wilde-like bachelor named Cecil Graham, also sported a green flower in his lapel when he delivered such quips as “We’re all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” In Paris, green carnations had replaced green cravats as signals between members of the homosexual demimonde, and Wilde had learned of the trend. He knew Londoners would talk, and they did, even if they didn’t really know what they were talking about.

Following the curtain call, Wilde strolled languidly onstage, a cigarette dangling between what one critic described as his “daintily gloved” fingers, and the green carnation affixed to his lapel. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “I have enjoyed this evening immensely. The actors have given us a charming rendering of a delightful play, and your appreciation has been most intelligent. I congratulate you on the great success of your performance, which persuades me that you think almost as highly of the play as I do myself.” Some were amused, but many others were revolted by what they regarded as an arrogant breach of decorum—especially smoking in front of the ladies. And that was the least of Wilde’s gender transgressions that night, and in general. Everyone understood that those green flowers meant something . . . something that mocked and subverted traditional notions of masculinity.

We don’t know what words Wilde exchanged with the Stokers that night, but we can assume he always thought of Stoker as something of a prig—the priggishness covering a submerged self Wilde could imagine all too well. It would have been so very easy, at the interval, while complimenting Florence on what a newspaper described as her “marvelous evening wrap of striped brocade,” to discreetly slip a carnation into Bram’s pocket to be discovered later. When he undressed.

It is difficult to understand how Stoker ever found time to write Dracula. In addition to Irving’s London seasons and provincial tours, and a command performance of Becket for Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, there were two more Lyceum tours to America, one in 1893–94 and another in 1895–96. Beyond theatre commitments was his continued involvement in Hall Caine’s literary affairs, including preparing for publication and writing introductions for reprints of Caine’s books. These were part of an ambitious enterprise headed by the publisher William Heinemann called the English Library, which invited established writers in England and America to distribute their work in continental Europe. Stoker was a partner in the imprint, along with publisher Wolcott Balestier and journalist W. L. Courtney. English Library authors included Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle, J. M. Barrie, and, at Stoker’s personal invitation, Mark Twain, who later became a friend when he lived with his family in London.

A letter written by H. P. Lovecraft in 1932, and first noted by Raymond T. McNally and Radu Florescu in 1979, claimed that “Stoker was a very inept writer when not helped out by revisers. . . . I know an old lady who almost had the job of revising ‘Dracula’ back in the early 1890s—she saw the original ms. & says it was a fearful mess. Finally someone else (Stoker thought her price for the work was too high) whipped it into such shape as it now possesses.” The explosive implications were not well received by Stoker aficionados, and the letter has routinely been dismissed as one of Lovecraft’s strange imaginings; the writer’s eccentricities have been exhaustively documented. However, Lovecraft told variants of the same story on at least three other occasions. As early as 1923, in a letter to writer Frank Belknap Long, he named the would-be book doctor as Edith Miniter. “Mrs. Miniter saw Dracula in manuscript about thirty years ago. It was incredibly slovenly. She considered the job of revision, but charged too much for Stoker.” A letter to Donald Wandrei in 1927 offered more information, and gave another decidedly negative appraisal of Stoker as a writer:

Have you read anything of Stoker’s aside from Dracula? . . . Stoker was absolutely devoid of a sense of form, and could not write a coherent tale to save his life. Everything of his went through the hands of a re-writer and it is curious to note that one of our circle of amateur journalists, an old lady named Mrs. Miniter, had a chance to revise the Dracula manuscript (which was a fiendish mess!) before its publication, but turned it down because Stoker refused to pay her the price which the difficulty of the work impelled her to charge. Stoker had a brilliant fantastic mind, but was unable to shape the images he created.

Finally, in a lengthy and heartfelt appreciation of Miniter written following her death in 1934, but not published until 1938, Lovecraft offered a different reason for her rejecting Stoker’s offer. “Notwithstanding her saturation with the spectral lore of the countryside, Mrs. Miniter did not care for stories of a macabre or supernatural cast; regarding them as hopelessly extravagant and unrepresentative of life,” Lovecraft wrote. “Perhaps that is one reason why, in the early Boston days, she had declined a chance to revise a manuscript of this sort which later met with much fame—the vampire novel Dracula, whose author was then touring America as manager for Sir Henry Irving.”

Edith Dowe Miniter (1867–1934) was a New England journalist and amateur fiction writer who published one commercial novel, Our Natupski Neighbors (1916). The amateur press movement to which Miniter belonged emerged after the Civil War as a serious hobby for people interested in writing, editing, and letterpress printing. Its small-circulation newspapers and journals served as social hubs, often extending to regional and national conventions. H. P. Lovecraft became active in the movement in 1920, the year he met Miniter, and the spirit of amateur journalism went on to significantly drive the growth of fantasy and science fiction fandom throughout the twentieth century.

Boston journalist Edith Miniter, who refused Stoker’s offer to edit and revise Dracula.

If Stoker offered Mrs. Miniter the job of revising Dracula, how and when did he meet her? When Henry Irving’s 1893–94 American tour reached Boston in January, Miniter had just joined the editorial staff of the Boston Home Journal, a lively arts and literary weekly. “Its Editorials are pungent and straightforward,” a typical advertisement for advertisers enthused. “Its Society News tells your doings and those of your friends. Its Fiction is of the highest order. Its Dramatic Criticisms are scholarly and its Musical Melange is sparkling. It is as full of interest as an egg is of meat. There is no doubt of the value of an ‘ad’ in the Boston Home Journal.”

The paper obviously had a good opinion of itself, and the promised editorial pungency came out in its reviews. The Lyceum was traveling with nine productions that season: The Merchant of Venice, Olivia, Nance Oldfield, The Bells, Becket, Louis XI, Charles I, The Lyons Mail, and Henry VIII. Early during the three-week engagement, the Journal showed it knew how to damn with faint praise. On the topic of Ellen Terry, an anonymous writer opined, “She is not a great actress in the sense of the word as usually applied to actresses of broad intellectual power and vivid passion—the Medeas and Lady Macbeths of the stage; she does not belong to their rank and fails to suggest even vaguely the scope and splendor of their geniuses. But with those who have seen her, she remains in the memory a dream of youth, beauty and sweetness.” Like Philadelphia, Boston was known for tough, skeptical critics; this may be a reason Broadway producers chose both cities as the most useful out-of-town venues in advance of New York.‡

Stoker was the company’s press contact, and he also bought the advertising. One can imagine he had some diplomatic words to share with the Journal editors, especially after the paper’s appraisal of The Merchant of Venice near the end of the Boston stay. Of Irving’s portrayal of Shylock, the reviewer did not mince words, calling the performance a “grotesque caricature.”

In representing, or attempting to represent, the racial characteristics of Shylock, Mr. Irving goes too far in a line that most actors do not go far enough in. Mr. Irving’s Shylock is the kind of a Jew that in our day we would expect to see upon the streets with a tray hung about his neck whereon would be displayed suspenders, buttons, combs, and other small articles, to say nothing of shoe strings. He is the kind of Jew that one would find in the lowest dives of the North End, by no means the Jew who could bring forth a daughter who could win the sympathy that Jessica demands.

The last comment was presumably a crumb thrown to Terry, who played Shylock’s daughter. But the attack on Irving continued with relish: “He is a dirty Jew, withal, one who deserves the contempt that is heaped upon him, not for his religion or belief, but for his own repulsiveness. . . . It is easy to see how Mr. Irving’s Shylock would be spurned as a rodent, as an unclean thing.” The reviewer also complained that Irving delivered the “Hath not a Jew” speech like “a second-hand clothing dealer disposing of a suit of clothes.”

Although Stoker might well have objected to the review as an affront to Irving—according to almost all other accounts, Irving played the always-problematic role with great restraint and dignity—the degree to which he was offended by the reviewer’s attitude toward Jews is a matter for debate. The great Gothic character then taking shape in Stoker’s mind has, in recent years, been criticized as an anti-Semitic stereotype, and perhaps deservedly. The simple idea of a hook-nosed foreigner who steals babies for their blood, of course, comes straight out of the time-dishonored playbook of the blood libel, not to mention the recoiling from Christian symbols. Stoker drops some casual anti-Jewish sentiment into Jonathan Harker’s journal entry of October 30, when it is discovered that a cargo receiver facilitating Dracula’s escape back to Transylvania in his earth-box is one Immanuel Hildesheim, “a Hebrew of rather the Adelphi Theatre type, with a nose like a sheep, and a fez. His arguments were pointed with specie [money in coin]—we doing the punctuation—and with a little bargaining he told us what he knew.”

Antisemitic Victorian architypes. George du Maurier’s “Filthy black Hebrew,” Svengali.

Henry Irving as Shylock.

Shylock was part villain but mostly victim. If Stoker needed a model for a thoroughly evil Jew, he needn’t have looked any further than a book he would have known well since childhood. Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1838) introduced the repellent character Fagin, who preys on children by turning them into thieves, with nowhere to go outside of his protection. He doesn’t abduct them in bags, but they are held hostage nonetheless, with the threat of a blood sacrifice hovering; when Oliver wakes after the first night in the thief’s house, a suspicious Fagin almost immediately threatens him with a knife. That it is described by Dickens as a bread-knife only intensifies a subliminal connection to the ancient calumny about the blood of Christian children being used to prepare Passover bread.

But the question remains: was Stoker himself anti-Semitic or racist? Probably not beyond the norm for Victorian England, where a basic distrust of foreigners and ideas about racial purity and the great hovering bugaboo of “degeneration” were so fully ingrained into daily life that they were deployed almost unconsciously. His 1886 pamphlet A Glimpse of America makes no mention of slavery or the Civil War, the unresolved social issues of Reconstruction, or the impact of race on American culture and character. He mentions blacks only in the context of being well represented as domestic servants, with the men being subject to immediate lynching if they commit an outrage upon a white woman. The lynched men are grouped by Stoker with a category of “tramps, and other excretions of civilization.” Near the end of his life, Stoker would turn again to the “American Tramp Question” and recommend the establishment of remote labor camps, as well as branding (or, as he put it, “marking the ear”). His final novel, The Lair of the White Worm (1911), would feature a frightening, subhuman manservant, Oolanga, whose fondness for wearing dress coats only underscores his apelike animality. The casual, recurrent use of the word “nigger” throughout the narrative is still a bit startling. Until the end of his life, Stoker’s library contained a history of the Ku Klux Klan’s first incarnation in the 1860s and 1870s.

It may have been in Boston, following the volley of undeserved critical abuse hurled at Irving, that he decided to write an essay on “Dramatic Criticism” and publish it in the North American Review while the American tour was still ongoing. He succeeded only in prompting the New York Times to spend more time in a Sunday column attacking Stoker than it did covering the appearance of Irving and Terry. The piece is remarkably vicious and personal.

Who said anything about dramatic criticism? Who asked Bram Stoker to write anything about it? Of course, everybody knows Bram Stoker’s name, for it has been in print before, and it is a name one never forgets, like Dodge Orlick or Quentin Durward. But few persons in this country have ever associated the name with a clearly-defined personality. If any of the John Smiths or William Browns of the American public, who read the North American Review to learn what public characters do not know about the questions of the hour, have thought of Bram Stoker at all, they have merely thought it was odd that any contemporary human being should be so named, and, being so named, should not ask legislative permission to change his name.

The Times conceded that “he is a gentlemen amply qualified to inform the world on some important subjects, such as the difficulty of keeping one’s temper when selling theatre tickets through a peephole to ungrateful and inquisitive people, and the quickest way to stick up a four-sheet poster on a windy day.” The writer predicted that “sometime in the twentieth century—I trust well along in that century—Mr. Bram Stoker will be of much interest to the biographers of Henry Irving. They will go to him for facts about the distinguished gentleman who employed him, as to his clothes and his food and his dependence on the advice of Bram Stoker.” As to Stoker’s perceived general grievance against drama critics on both sides of the Atlantic, the Times speculated that “perhaps they have too frequently neglected to mention in their notices that during the performance the money at the box office was counted, with his accustomed skill, by Mr. Bram Stoker, who also, after the play, and with great delicacy of touch, filled his hand-wash basin and laid out the towels for Mr. Irving to remove his ‘make-up.’ ”

In his essay, Stoker had quoted an anonymous British critic who wondered if actors should be considered parasites, since they lived off plays, playwrights, and producers. The Times jumped at the chance for a delicious, gratuitous coup de grace: “We can imagine what such a critic, who holds an actor to be a parasite, would call an actor’s business agent. He might even be rude.”

The anonymous Times writer wanted to land a punch, and succeeded. The column was both a merciless caricature of Stoker as Irving’s fawning factotum and a direct attack on his abilities as a writer. He had, of course, seen Irving endlessly assailed and ridiculed, but he was not at all accustomed to being on the receiving end himself. It’s hard to imagine Stoker having knowingly snubbed or otherwise displeased anyone at New York’s leading newspaper, but someone in the employ of the Gray Lady had obviously been offended somehow, and expressed his umbrage in the most humiliating way possible. The attack was so personal that it pricks curiosity about the nature of Stoker’s friendships (and possible intimacies) in America, which almost by necessity would have overlapped with his theatrical responsibilities, and perhaps compromised or complicated them.

For Stoker, the winter of 1894 was not a happy season. Aside from a personal but very public slap in the face from the New York Times, the vampire novel was tied in knots he would have to untangle himself, and his summer holiday would be devoted to yet another book, The Watter’s Mou’, set in Cruden Bay, Scotland, which he had visited for the first time the previous year. As a fallback, he dusted off a short historical novel, Seven Golden Buttons, which he had finished in 1891 but never submitted for editorial consideration. After returning to London he offered it to the Bristol publishing house J. W. Arrowsmith, but it was rejected.

As for the vampire book, it is not known whether Edith Miniter gave him any kind of detailed critique, but from his notes we can surmise the manuscript was likely a now-lost first draft titled either The Dead Un-dead or The Un-Dead. “Undead” was an existing word, derived from the Middle English undedlic but having no supernatural connotation; it was merely a roundabout locution for being alive, that is, “not dead.” Stoker’s hyphenated coinage was the first known use of the term in its now-familiar revenant sense. He must have had the work-in-progress already transcribed by a typing service, in manifold (a precursor to the carbon paper process), since it is inconceivable he would leave the only copy of a handwritten draft in America, even if Miniter had accepted the book-doctoring assignment. And it’s a fair assumption the “fearful mess” of the manuscript resulted from what is apparent in Stoker’s notes: far too many characters with overlapping identities and functions, and a surfeit of subplots. It was the most complicated and ambitious piece of fiction he had ever attempted, but his ambition simply outpaced his technical ability to manage and channel his own imagination.

In order to conceptualize (or at least roughly imagine) what the manuscript that ultimately became Dracula might have looked like in early 1894, it is useful to flash forward six years to Reykjavik, Iceland, when a novel called Makt Myrkranna (or Powers of Darkness) was published under Stoker’s name as a magazine serial in 1900 and as a book in 1901, an apparent translation of Dracula. The translator was Valdimar Ásmundsson, a well-regarded Icelandic journalist and author, but with no other known connection to supernatural fiction. Since the rest of the book was far shorter than the 1897 Archibald Constable edition, it had until recently been assumed that the novel had been abridged. A previously unknown introduction to the book, signed by Stoker, caused stirs in Dracula circles when it was retranslated into English in 1986, largely because it made a tangential reference to the Jack the Ripper murders, sparking overheated speculation about a substantial, inspirational link to the Whitechapel crimes and perhaps even clues to the killer’s identity.

In 2014, the Munich-based Stoker scholar Hans C. de Roos revealed that Makt Myrkranna was in fact a radically different telling of Dracula, 80 percent of its action taking place during Harker’s visit to Transylvania. Dracula is “the leader and financier of an international elitist conspiracy,” according to Roos, who, at the time of this writing, is preparing a full English version of the Icelandic text. Ásmundsson, whose other writings covered both socialism and anarchism, “puts the fiend in the corner of reactionary social-Darwinist forces as the arch-enemy of egalitarianism, at the same time linking him to vile murder, sexual libertinage, incestuous degeneration and satanic cult: at Castle Dracula, Harker sees the Count leading a kind of black mass.” Once Dracula is in England, his home is not a ruin but a splendidly appointed showplace where the Count (under the adopted name of Baron Székély) entertains a band of glamorous and aristocratic co-conspirators who have enabled his relocation from Transylvania.

Could such a strange, truncated and bastardized version of Dracula have actually been approved by Stoker? Roos seems to think so, but there are other factors and possibilities that need consideration. To begin with, why was this text created in Iceland? Stoker had no known contacts or correspondents there. But Hall Caine did. He knew the country extremely well and had friends there, and it provided a major setting for his novel The Bondman (1890). As Stoker wrote in his 1895 introduction to the book’s reissue as part of Caine’s collected works, “Iceland and the Isle of Man are so closely linked by far-back associations, that one cannot deeply study the history of one without being somewhat fascinated by the other.” In The Essential Dracula, Raymond McNally and Radu Florescu first floated the possibility that Caine himself might have been the “someone else” whom H. P. Lovecraft mentioned as having “whipped [Dracula] into such shape as it now possesses.” Given the extent of Caine’s own publishing commitments between 1894 and 1897, this is highly unlikely. But Caine could have given Stoker advice, or recommended another writer to help revise the book. A writer, perhaps, who lived in Iceland.

While no correspondence between Caine and Ásmundsson has yet surfaced, a surprisingly large percentage of Caine’s papers has yet to be sorted or cataloged, and may yet yield surprises about the Icelandic connection to Dracula. Nonetheless, we can be confident that Ásmundsson somehow had access to an early version of the manuscript. The evidence is contained in Stoker’s preliminary notes. The Icelandic book contains a character named Barrington, who does not appear in the finished novel, but does appear in the notes. Likewise, a deaf-mute housekeeper, and a dinner party at which Dracula is the final guest to arrive. None of these elements were available to Ásmundsson via the published version of Stoker’s novel. The retranslated version of the Icelandic introduction reads suspiciously like Stoker’s bloated, overstrained first draft of the terse prefatory note that effectively opens the book as we know it today.§

Is it possible that Ásmundsson, on Caine’s recommendation, took on the formidable job of revising The Un-Dead? And that Makt Myrkranna was the bizarre, off-the-rails, and ultimately rejected result? Even without Stoker’s early draft for comparison, this makes far more sense than the idea that Stoker actually approved the Icelandic adaptation—which, at least according to Roos’s synopsis, reads like a piece of unauthorized fan fiction, with scant regard to the original author’s vision. But no regard or respect was needed. Iceland had not yet joined the Berne Copyright Convention. Neither Ásmundsson nor his publishers needed to seek permission from Stoker or any other foreign national for publication. Their works could be pirated with impunity. Indeed, the initial installment of the serialization in the January 13, 1900, weekly magazine Fjallkonan contains no notice of copyright, describing the work only as “Novel. After Bram Stoker.”

Without the literary equivalent of a major international archaeological dig—funded, exactly, by whom?—the truth may never be known. But there can be no doubt that Ásmundsson had access to some of the earliest notes or drafts of Stoker’s book, upon which he constructed a uniquely curious fantasia. The fact that Makt Myrkranna gives so much play to the Transylvania chapters may indicate that Harker’s visit to Transylvania was the most coherent section of the lost draft, and that Stoker may have had as much trouble getting out of Castle Dracula as a writer as Jonathan Harker did as a character.

Victorian writers were bedeviled by literary piracy, which they rightly considered parasitism—a charged word with many other associations apart from intellectual property theft. In the hierarchy of social Darwinism, the poor, foreigners, the weak, and the infirm were all perceived as sapping power and money from the middle and upper classes. For nervous men, women’s growing independence was experienced as a kind of sexual energy siphon. Arthur Conan Doyle’s novella The Parasite (1894) presented a psychic female vampire: a self-employed, self-possessed, and sexually self-directed occultist who used her powers to seduce and destroy.

Parasitism was also a concern of degeneration theory. In Dracula, Stoker drops the names of two leading degenerationists, the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), author of Criminal Man (1876), and the German cultural critic Max Nordau (1849–1923), author of Degeneration (1892–93; English translation 1895). Lombroso would have interested Stoker because of his own long-standing interest in phrenology and physiognomy, but Lombroso’s direct influence on Dracula has been consistently exaggerated. Criminal Man put forth Lombroso’s taxonomy of the physical characteristics of people he claimed were “born criminals,” and these characteristics, or so it is said, formed the basis of Stoker’s description of Dracula. In fact, Stoker’s vampire bears little resemblance to any of Lombroso’s examples, save for his claim that murderers tended to have hawklike noses, a trait already supplied for Dracula’s villainous precursors in fiction, and that the eyebrows above such noses grew together (as did those of the evil Ambrosio in Lewis’s The Monk and the werewolf as described by Baring-Gould). Lombroso also mentions, almost in passing, that a small protuberance atop the criminal ear is the vestige of an animal’s pointed ear. Dracula, of course, has fully pointed ears—something Stoker had seen on imaginary beings since childhood, when he first beheld the costumes for beloved pantomime characters like the Wolf, Puss in Boots, and Dick Whittington’s Cat. The goat god Pan and the satyr in general were common subjects of nineteenth-century academic painting, reflecting a general cultural delirium about reverse evolution and animal tendencies in humans. Lombroso’s criminal types lacked mythic resonance; they had jug ears, asymmetrical features, prognathous jaws, and receding brows with small craniums—quite unlike Dracula’s “lofty domed forehead,” clearly intended by Stoker to signify superior intelligence and cunning. We can safely conclude that Stoker invoked Lombroso merely as a contemporary, authoritative reference to bolster verisimilitude, however pseudoscientific. Stoker’s description of Dracula’s face ultimately owed much more to Baring-Gould and to his own imagination than to Lombroso.

Nordau’s Degeneration, though formally dedicated to Lombroso, was more concerned with finding evidence of mental and moral decay in cultural productions, not in somatotypes. There was almost nothing in fin-de-siècle arts and letters that met with Nordau’s approval. Pre-Raphaelitism, aestheticism, symbolism, realism, naturalism, mysticism, and everything from the philosophy of Nietzsche to the theatre of Ibsen—for Nordau, all were clear signs of creeping hysteria and insanity, both in their creators and in the public that accepted them. Nordau actually believed that both visual art and the written word had the power to reverse human evolution. “When under any kind of noxious influences an organism becomes debilitated,” he wrote, “its successors will not resemble the healthy, normal type of the species, with capacities for development, but will form a new sub-species.” Degeneration was a contagious disease, even if Nordau could identify no particular agent of contagion. His book was basically a scream against the miasma of modernism in all its forms. In literature, among many other things, Nordau objected to exactly the kind of “rationalized” horror fiction Stoker was writing. According to Nordau, “Ghost stories are very popular, but they must come on in scientific disguise, as hypnotism, telepathy, somnambulism.” Stoker was using precisely these elements, widely accepted as scientific in the 1890s, to give his novel-in-progress credibility.

It should not be surprising that Nordau also had a specific distaste for Oscar Wilde.

“Where, if not from the Impressionists, do we get these wonderful brown fogs that come creeping down our streets, blurring the gas-lamps and changing the houses into monstrous shadows?” Wilde had written. “The extraordinary change that has taken place in the climate of London during the last ten years is entirely due to this particular school of Art.” Nordau was appalled, and completely insensate to Wilde’s humor. “He asserts that painters have changed the climate,” he sputtered. Nordau felt that Wilde’s degeneracy rose from “a malevolent mania for contradiction” and a “purely anti-socialistic, ego-maniacal recklessness and hysterical longing to make a sensation.”

Wilde, of course, reveled in public attention, all the more so with the increasing success of his drawing-room comedies: Lady Windermere’s Fan (1893), A Woman of No Importance (1894), and An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest (both 1895.) But his private life was increasingly disordered and indiscreet. He was seen everywhere dining extravagantly with Bosie, while privately he endured torrents of Douglas’s rage and emotional abuse—which he always forgave, like a clueless battered spouse.¶ Other companions lacked Bosie’s pedigree, comprising a shifting entourage of scruffy young men whose most valuable assets, no doubt, included the endless supply of engraved silver cigarette cases Oscar had given them.

Unlike Stoker, Wilde had never been a college athlete, but from his early years there remain descriptions of a powerful, imposing physique. However, by the early nineties, after more than a decade of gastronomic indulgence and dissipation, he had morphed into a corpulent caricature of himself, subject to the kind of merciless lampooning his mother had endured in Dublin. There can be no doubt that his physical presence caused many people to shudder. The American novelist Gertrude Atherton, in London during the early nineties, turned down the chance to meet him solely on the basis of her visceral reaction to a photographic portrait—the very daguerreotype of Dorian Gray, at least in Atherton’s description. “His mouth covered half his face,” she recalled, “the most lascivious coarse repulsive mouth I have ever seen. I might stand it in a large drawing room, but not in a parlor eight-by-eight lit by three tallow candles. I should feel as if I were under the sea pursued by some bloated sea monster of the deep, and have nightmares for a week thereafter.”

A Washington Post caricature of Wilde as the Missing Link.

For all his intellectual brilliance, Wilde set off atavistic, Darwinian anxieties in his detractors, as well as in his partisans. Again and again he was described as pale and bloodless, a kind of fleshy, engulfing amoeba. Even his admirer Richard Le Gallienne admitted to a “queer feeling of distaste, as my hand seemed literally to sink into his, which was soft and plushy.” “The face was clean-shaven, and almost leaden-coloured,” recalled Horace Wyndham in The Nineteen Hundreds, “with heavy pouches under the eyes, and thick blubbery lips. Indeed he rather resembled a fat white slug, and even to my untutored eye, there was something curiously repulsive and unhealthy in his whole appearance.” Alice Kipling, Rudyard’s sister, quickly detected signs of invertebrate life: “He is like a very bad copy of a bust of a very decadent Roman Emperor, roughly modeled in suet pudding. I sat opposite him and could not make out what his lips reminded me of—they are exactly like the big brown slugs we used to hate so in the garden.” Whistler once caricatured Wilde as a pig. As early as his 1882 American tour, the Washington Post had depicted him outright as an evolutionary throwback, “the Wilde Man of Borneo,” foreshadowing ridicule to come. And capitalizing on the Wildean fondness for the sunflower as an aesthetic prop, many graphic satirists chose to go even further, casting Wilde lower than the animal realm as a human sunflower—a droopy, half-vegetable monstrosity.

As Irishmen in London, Stoker and Wilde were keenly aware of the pernicious and deeply ingrained stereotype of the Irish as brutish, drunken, and subhuman. The shiftless stage Irishman was already a sturdy convention of comedy. It was a caricature often deepened and darkened elsewhere, as in the pages of Punch by artists like Sir John Tenniel (“the Irish Frankenstein,” looking more like a simian Mr. Hyde). The magazine once featured a “satirical” piece called “The Missing Link,” informing readers that “a creature manifestly between the Gorilla and the Negro is to be met in some of the lowest districts of London.” The Hibernian ape stereotype originated before Darwin but quickly drew additional noxious energy from evolutionary theory. Following a visit to Ireland in 1860, the Cambridge historian Charles Kingsley wrote to his wife, “I am haunted by the human chimpanzees I saw along the hundred miles of horrible country.” The Famine years had stoked intolerance as well; if the Irish seemed animalized by hunger, it was because they were animals to begin with.

In the face of British power and intolerance, Wilde’s mother had always asserted her Irish identity. Oscar, by contrast, ingratiated himself with the enemy, shedding his Irish accent at Magdalen College and arriving in London with a comprehensive plan for social climbing. Lady Wilde’s surrogate son Bram Stoker made no such move toward assimilation and retained his rich and musical brogue for life. Unlike his own parents, he supported home rule. Perhaps part of the reason for the New York Times’s personal attack on him was unvarnished antipathy for his nationality. Like their counterparts in London, many New Yorkers in the 1890s reacted to Irish immigrants with a visceral revulsion.

Stoker, of course, never sought the spotlight like Lady Wilde’s real son. Through Henry Irving and his rabid detractors, he became well acquainted with the dark and vicious flip side of public acclaim. Even as Wilde’s sparkling plays earned plaudits and applause, the public sensed his shadow side the way sharks smell blood. Wilde was a constant topic of increasingly nasty gossip, fueled in no small part by a scandalous roman à clef by Robert Hichens, The Green Carnation, published anonymously in 1894. Hichens had slyly penetrated Wilde’s circle the year before and observed Oscar and Bosie at close quarters; in the book he gave them the fictional names of Esmé Amarinth and Lord Reginald (Reggie) Hastings. In a scene parodying the dyed-boutonniere opening night of Lady Windermere’s Fan, a young lady, recently arrived in London, notices the green flowers and comments that “all the men who wore them looked the same. They had the same walk, or rather waggle, the same coyly conscious expression, the same wavy motion of the head. . . . Is it a badge of some club or society, and is Mr. Amarinth their high priest?” The Saturday Review was not so naïve as the naïf and duly made note of the novel’s “allusions, thinly veiled, to various disgusting sins.”

Lord Alfred Douglas’s father had introduced the Queensberry rules of boxing, but the marquess had a personality sufficiently pugnacious to ignore any rules of engagement he didn’t care for. Especially when he felt certain his opponents were guilty of disgusting sins. To the marquess, paranoia came easily; the Douglas clan had a history of psychological instability. By the early 1890s Queensberry was thought by some—perhaps especially those who were scandalized by Ghosts—to be yet another sad victim of long-simmering syphilis. It was not an outlandish idea. He was obsessed to the point of derangement with the idea that the soon-to-be prime minister (Archibald Primrose, the 5th Earl of Rosebery) was having an affair with his eldest son, Francis, who served as Rosebery’s personal secretary. Francis Douglas died in an 1894 “hunting accident” that many suspected was a suicide but has never been proven as such. Queensberry threatened to thrash Rosebery in public and even carried a riding crop to be on the ready.