One sunny spring day in the mid-1990s, Ms. Fletcher stopped me on the brick walk outside my office just as I was opening the front door. With only a few minutes before the start of afternoon office hours, I was feeling pulled by a couple of phone calls that still needed to be returned. She asked if I was Dr. Abramson. When I said yes, she said that the HMO she had just enrolled in had required her to choose a primary care doctor. Ms. Fletcher wanted to know if she could list me as her doctor because she had heard that I was interested in alternative medicine. I said that was partially true; I am interested in any kind of treatment that helps. But I also made it clear that I was interested only in therapies—alternative or not—that were supported by good scientific evidence.

Ms. Fletcher, who appeared to be a healthy though harried woman in her mid- to late forties, then told me that she had breast cancer. The pressure I was feeling to get to the telephone faded. She quickly added that the only therapy she had received, or wanted to receive, was alternative therapy—no surgery, no radiation, and no chemotherapy.

My mind flashed back to Ms. Card (who had insisted I call her by her first name, Wendy), a woman I had taken care of several years before who had made the same decision. By the time I got involved in her care, the tumors in her breast and under her arm were growing quickly, and actually eroding through the skin. I prescribed medication to control her pain and the local infection around the tumors, but there was little chance that any therapy could control her underlying disease. As her physical condition deteriorated over the next few weeks, I made several house calls. We talked about what could be done to make her more comfortable; she told me about her friends and her spiritual practice, both of which were very important to her; and we talked about her family. She had been estranged from her parents for several years and was struggling with the decision about whether to let them back into her life. She invited her parents to visit for a couple of days. During their visit she decided to go home to New York with them, to let them take care of her in her last few weeks. I arranged for hospice to get involved as soon as she got to her parents’ home. Wendy’s capacity to heal the wounds in her life as best she could in preparation for her death brought a sense of hope to the tragedy of her situation.

My attention returned to Ms. Fletcher. I suspected that in this seemingly casual conversation—interrupted as it was by office staff, patients, and the Fed Ex guy walking between us on their way into the office—she was asking for my approval of her decision to use only alternative therapy. After visualizing what Wendy’s upper chest and underarm had looked like before she left for New York, I wanted to be careful not to leave Ms. Fletcher with the impression that I supported her decision to forgo conventional therapy. I told her that I would be happy to be her doctor, and that she should make an appointment so that we could get to know each other and discuss her options.

Ms. Fletcher did sign up as my patient, but she never came in for an appointment. I think she knew that I would try to engage her in a discussion about her medical situation and that I had reservations about her approach. Sometimes just the process of engaging in a doctor-patient relationship is the most effective alternative medicine—using the safety and trust of the doctor-patient encounter as an opportunity to connect with deeper concerns, to be able get these issues out on the table so that they can be addressed and progress made: physical, emotional, or both. But I also thought it was her right to choose not to engage in this kind of relationship with me.

I had not heard from Ms. Fletcher for about a year, when I got a message that she had called my office requesting a referral to see an oncologist in Boston. To avoid creating an uncomfortable telephone encounter, I suggested through a nurse that she come in to see me first. She declined. I approved the consultation.

The oncologist soon called to inform me that Ms. Fletcher’s breast cancer had metastasized widely throughout her body and asked for my approval, as Ms. Fletcher’s primary care physician, for her to receive high-dose chemotherapy followed by bone marrow transplantation. The goal of this treatment is to administer an otherwise lethal dose of chemotherapy—enough to destroy all of the rapidly dividing cells in the body, including the blood-forming cells in the bone marrow—in the hope of destroying all of the cancer cells in the process. Before the therapy, bone marrow cells from Ms. Fletcher would be “harvested.” After the chemotherapy, Ms. Fletcher would then be “rescued” by “reseeding” her marrow with her own bone marrow cells, thereby restoring her ability to make red and white blood cells. The procedure required about two weeks in a sterile room, to avoid infection while her immune system was suppressed, and up to a month in the hospital. This was a rough ride, with the volume turned all the way up on all the discomfort and risks of chemotherapy: hair loss; nausea and vomiting; ulcers on the inside of the mouth and the gut; possible damage to the heart, kidneys, and nerves; and the risk of serious infection until the immune system recovers.

Knowing how sick Ms. Fletcher would become from the therapy itself and sadly aware of how advanced her breast cancer was, I asked the oncologist if she was sure this was the right thing to do. She said that high-dose chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation was the best therapy for women like Ms. Fletcher, that is, women with advanced breast cancer. I had little experience with this and had to trust the oncologist’s opinion. I certainly wanted my patient to get the best therapy available.

As this conversation was going on, I was thinking about the contrast between Ms. Fletcher’s complete rejection of conventional medicine and her abrupt return to the most aggressive therapy in the face of her advancing disease. Even though she had eschewed conventional therapy early on, now it seemed that she may have been taking comfort in the belief that modern medicine could rescue her if her disease got out of control. I also thought about her unwillingness (or inability) to engage in a doctor-patient relationship with me, and wondered whether she had been able to explore with anybody the important issues in her life. And I wondered whether her oncologist thought of death as the final defeat against which all-out war must be waged, even though there was no real hope of winning.

Although the decision to go forward had already been made and the oncologist seemed to be calling more as a courtesy than for a real discussion, I still regret that in that rushed moment on the telephone I was so deferential. I feared that Ms. Fletcher and her oncologist were, each for her own reasons, grasping at straws, and I hoped I was wrong. In the end I kept my doubts to myself, approved the procedure, and got back to the patient I had left to take the phone call.

In retrospect, I realize that there was something else going on. Ms. Fletcher, her oncologist, and I were all emboldened by our implicit trust in the efficacy of the most advanced medical care that was to be provided in a top-notch academic medical center. Most Americans share this great faith in the superiority of American medicine. It is easy to see why. During the twentieth century alone longevity in the United States increased by 30 years. During the last 50 years medical science has made tremendous progress in improving health and the quality of our lives.

The elimination of polio, the most feared disease of my childhood, is a perfect example of the triumph of American ingenuity. In 1953 about one out of every 100 Americans below the age of 20 had experienced some degree of paralysis caused by polio. Then, with well-deserved fanfare, the Salk vaccine was launched for use on April 12, 1955, exactly 10 years after the death of our most famous polio victim, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The vaccine was immediately put into widespread use. I remember lining up in the elementary school gym as a third-grader to get my first polio shot, my childhood fear eased (mostly) by the understanding that I would no longer have to worry about getting polio.

Huge strides have also been made in biomedical engineering and surgical techniques in the last 50 years. The cardiopulmonary bypass machine, which pumps blood through an artificial lung, replacing carbon dioxide with fresh oxygen, and then back into the body, allows surgeons to perform intricate heart surgery. The first successful surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass was done in Sweden in 1953, on an 18-year-old girl with a congenital heart defect. By 1960, surgery to bypass blockages in the arteries that supply the heart muscle with blood (coronary arteries) could be performed with relative safety. Surgical replacement of poorly functioning heart valves soon followed. By the time I was in medical school, in the mid-1970s, these operations had become routine.

Dialysis, to filter the blood of people with chronic kidney failure, became a reality in the 1960s. In 1972 the Social Security Act was amended to extend Medicare coverage to all patients with end-stage renal disease, covering all the costs of chronic dialysis. About 250,000 Americans are alive today because they have access to ongoing dialysis. Successful transplantation of hearts, lungs, and livers have been lifesaving. Transplantation of kidneys and corneas allows people to live normal lives. Hip and knee replacements have restored comfort and function to millions of Americans.

There has been great progress with new drugs, too. Tagamet first became available when I was just starting my two years in the National Health Service Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service, in 1977. I remember the first patient I treated with Tagamet: a state policeman who had already had one stomach operation because of an ulcer and was developing the same symptoms again. He thought he was headed for a second and more extensive operation, but Tagamet suppressed the acidity enough for the lining of his stomach to heal. Zantac was perhaps a slight improvement, reputedly causing fewer side effects. The vast majority of people with ulcers and ulcerlike symptoms improved with these drugs. In 1989 Prilosec came on the market, the first of the proton-pump inhibitors, suppressing acid formation many times more powerfully than Tagamet or Zantac.

The mortality rate from AIDS in the developed countries has gone way down as new drugs have been developed that control HIV infection. Gleevac is a true miracle of modern medical science. This treatment for a slow-acting form of leukemia (chronic myelogenous leukemia) specifically blocks the body’s production of an enzyme that causes white blood cells to become malignant. (Unfortunately it’s priced at $25,000 per year of treatment.)

The introduction of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) into clinical practice in the mid-1980s is rated, in a survey of well-respected primary care doctors, as the most important development in clinical medicine over the last 25 years. In the early 1980s, when the chief radiologist at my local hospital first explained how this soon-to-arrive technology produced its images, I thought he was joking. (Nuclei of the body’s hydrogen atoms are aligned by a powerful magnet. FM radio beams are focused on the area to be scanned, causing “resonance” of the aligned nuclei. Minute amounts of energy are emitted as the radio beam is turned off and the nuclei return to random orientation. This energy is measured by sensors and sent to a computer, which produces exquisite three-dimensional pictures of the human body.) Now these scans are commonplace.

A number of my patients are alive only because of recent medical advances: massive heart attacks completely reversed by “clot-busting” drugs, exquisitely delicate lifesaving cancer surgery on a child, successful liver transplantation, and an implanted cardiac defibrillator that senses and automatically treats several episodes of potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmia, to name just a few of the more dramatic examples. After the satisfaction of providing good medical care based on ongoing trusting relationships with my patients and the pleasure of working with an incredibly dedicated group of people in my office, my greatest satisfaction as a doctor has been working with my specialist colleagues to ensure that my patients get the full benefit of the most up-to-date care available.

Clearly these medical breakthroughs have contributed to increased longevity and improved quality of life; this is why I, too, believed that Americans received the best medical care in the world. Then I saw an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, in July 2000, claiming that “the U.S. population does not have anywhere near the best health in the world.” On first read, I thought that surely the author was overstating the case.

In a comparison of 13 industrialized nations that will surprise most Americans—and certainly most American physicians—Dr. Barbara Starfield, University Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, found that the health of Americans is close to the worst on most measures and overall ranked second to last. Contrary to common wisdom, the poor ranking of the United States cannot be attributed to our rates of smoking, drinking, or consumption of red meat. Surprisingly, Americans rank in the better half of the 13 countries on these measures, and have the third lowest cholesterol level. (Deaths due to violence and car accidents were not included in the data.)

The low ranking of Americans’ health reported in this article was so disparate from what I had believed that I started to look for other sources of comparative data to see if this was right. An extensive comparison of the health of the citizens of industrialized countries done by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) confirmed the conclusions presented in Dr. Starfield’s article. The United States again ranked poorly, with 18 industrialized countries having greater life expectancy.*

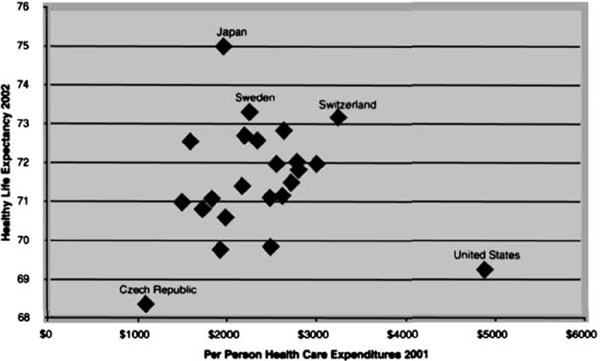

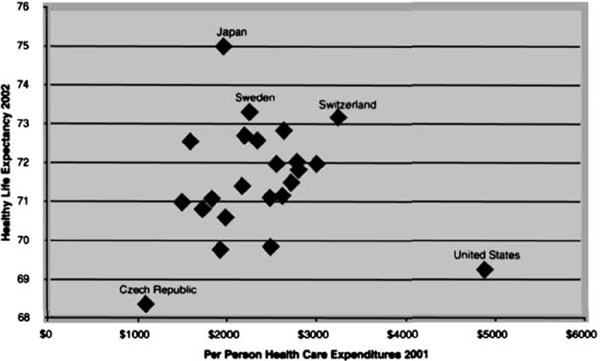

One of the best single indicators of a country’s health was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO); it is called “healthy life expectancy.” This measure represents the number of years that a child born now can expect to live in good health (i.e., total life expectancy minus years of illness adjusted for quality of life). Children born in the United States today can expect to live the equivalent of about 69.3 healthy years of life, while children born in the other 22 industrialized countries can expect an average of 2.5 additional years of healthy life. And children born in Japan can expect almost six more years of good health than Americans. Americans’ healthy life expectancy ranks 22 out of 23 industrialized countries, better only than the Czech Republic.

The World Health Organization also developed several broader measures of health system performance, providing more in-depth comparisons between countries. On “overall achievement,”* the health care system in the United States ranks 15 in the world. “Overall performance” measures the efficiency of a health system by taking into account the per-person health expenditures required to reach its level of achievement. On this measure the U.S. health care system ranking falls to 37. Finally, “performance on the level of health” measures the efficiency with which health care systems improve their citizens’ overall health. On this measure, the United States’ ranking drops to a lowly 72 in the world.

Despite the poor performance of the American health care system, our health care costs are simply staggering. In 2004, health expenditures in the United States are projected to exceed $6100 for every man, woman, and child. How does this compare with other countries? The United States spends more than twice as much per person on health care as the other industrialized nations. Even taking into account our higher per-person gross domestic product, the United States spends 42 percent more on health care per person than would be expected, given spending on health care in the other OECD nations. The excess spending on health care in the United States is like a yearly tax of more than $1800 on every American citizen. (And still the United States is the only industrialized country that does not provide universal health insurance, leaving more than 43 million Americans uninsured.)

The U.S. health care system is clearly alone among the industrialized countries. The following chart shows that Japan and Switzerland stand out for their good health, and the Czech Republic stands out for its low cost and poor health. The United States, however, is almost off the chart with its combination of poor health and high costs (see Fig. 4-1).

FIGURE 4-1. HEALTHY LIFE EXPECTANCY AND PER PERSON MEDICAL EXPENDITURES FOR 23 OECD COUNTRIES

Notwithstanding the tremendous progress and the enormous cost of American medicine, over the last 40 years the health of the citizens of the other industrialized countries has been improving at a faster pace. According to researchers from Johns Hopkins, “On most [health] indicators the U.S. relative performance declined since 1960; on none did it improve.” One of the most telling statistics is the change in the years of life lost below the age of 70, before death due to natural aging starts to become a factor. In 1960, Americans ranked right in the middle of 23 OECD countries on this measure. But despite all of the extra money being in spent on health care in the United States, the health of the citizens in the other OECD countries is improving more quickly. By 2000, men in the United States were losing 21 percent more years of life before the age of 70 than men in the other OECD countries, and American women were losing 33 percent more.

All this does not add up. The United States’ emergence as the world leader in medical research, combined with seemingly bottomless pockets when it comes to health care, does not square with the comparatively poor health of Americans.

One explanation for this paradox is that the United States foots the bill for a disproportionate share of medical innovation, from which the rest of the world then benefits. And indeed, this argument is often used to explain why brand-name prescription drugs cost about 70 percent more in the United States than in Canada and western Europe. But at least with respect to pharmaceutical innovation, the facts tell a different story. From 1991 to 1999, pharmaceutical companies in the United States did not develop more than their share of new drugs on a per capita basis compared with western Europe or Japan. Furthermore, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, of the 569 new drugs approved in the United States between 1995 and 2000, only 13 percent actually contain new active ingredients that offer a significant improvement over already available drugs and therapies.

Another reason why Americans believe they get better health care than any other nation may be that it appears as though we do. According to surveys done by the World Health Organization for its World Health Report 2000, patients in the United States are provided with the best service in the world. These surveys evaluated seven nonmedical aspects of health care—dignity, autonomy, confidentiality, prompt attention, quality of basic amenities, access to family and friends during care, and choice of health care provider. The WHO aggregated these results into a measure called “health system responsiveness,” on which the United States ranks first.

The myth of excellence is also sustained by the assumption that advances in medical care are responsible for most of the gains in health and longevity realized in the United States during the twentieth century. I admit that I was dubious when I first read that this was not the case. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Since 1900, the average lifespan of persons in the United States has lengthened by greater than 30 years; 25 years of this gain are attributable to advances in public health.” These include improvements such as sanitation, clean food and water, decent housing, good nutrition, higher standards of living, and widespread vaccinations.

The CDC’s report was based on a 1994 article in the prestigious Milbank Quarterly, written by researchers from Harvard and King’s College, London. They found that preventive care as recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force report—including, for example, blood pressure screening, cancer screening, counseling about smoking, routine immunizations, and aspirin to prevent heart attacks—adds only 18 to 19 months to our lives. Medical care for illness (heart attacks, trauma, cancer treatment, pneumonia, appendicitis, etc.) increases our life span by 44 to 45 months. The overall effect of medical care, then, has been to increase longevity by only about 5 years and 3 months during the twentieth century. (It is also important to remember that many medical interventions—like joint replacement and cataract removal—can produce benefits in the quality of life without improving longevity. These improvements are included in the World Health Organization’s calculation of “healthy life expectancy,” discussed above.)

By looking at the leading causes of death during the twentieth century, we can see just how limited the role of advances in medical care has been in extending life expectancy. In 1900, tuberculosis was the leading cause of death in the United States. Over the next 50 years, the death rate from TB fell by 87 percent.

This dramatic decrease in the tuberculosis death rate may appear to be a great triumph for American medicine, but in truth it was entirely due to improvements in the social and physical environment, such as healthier living and working conditions, better nutrition, more education, and greater prosperity. The first effective medical therapies for tuberculosis, the antibiotics isoniazid and streptomycin, were not even introduced until 1950, well after death rates for tuberculosis had plummeted. Throughout the twentieth century, similar patterns occurred in the death rates from many other infectious diseases, such as measles, scarlet fever, typhoid, and diphtheria. As with tuberculosis, the vast majority of the decline in mortality occurred before the introduction of effective medical therapy, antibiotics, or vaccines—polio and HIV/AIDS being the notable exceptions.

Rene Dubos, a French-born microbiologist who discovered the first two commercially manufactured antibiotics, wrote in his classic book The Mirage of Health, “The introduction of inexpensive cotton undergarments easy to launder and of transparent glass that brought light into the most humble dwelling, contributed more to the control of infection than did all the drugs and medical practices.”

Our experience with cancer during the twentieth century proves the point in reverse. Despite an enormous investment in cancer research, the age-adjusted death rate for cancer in the United States actually increased by 74 percent from the beginning to the end of the twentieth century. And by the end of the twentieth century, the age-adjusted death rate for cancer was the same as for tuberculosis at the beginning of the century: it had become the number one killer among people below of the age of 75.

In 1971 Congress launched a war on cancer by passing the National Cancer Act. President Nixon boasted, “This legislation—perhaps more than any legislation I have signed as President of the United States—can mean new hope and comfort in the years ahead for millions of people in this country and around the world.” In 1984 the director of the National Cancer Institute told Congress that the death rate from cancer could be cut in half by 2000. But two years later, an article published in New England Journal of Medicine, coauthored by a statistician from the National Cancer Institute, concluded just the opposite: Cancer death rates were going up, and “we are losing the war against cancer.”

There have been a few tremendous successes in this war, notably with some of the childhood cancers, testicular cancer, Hodgkin’s disease, and leukemia. Notwithstanding the barrage of news about major breakthroughs in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, the overall death rate from cancer was exactly the same in the year 2000 as it had been in 1971, when “war” was declared.

In 1998, the President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry provided a concise statement of the proper goal of a nation’s health care system: “The purpose of the health care system is to reduce continually the burden of illness, injury, and disability, and to improve the health status and function of the people of the United States.” About 70 percent of the health care in the United States is directed toward meeting this goal.* The other 30 percent is commercially driven health care activity without demonstrable health benefits. The problem for doctors and the public is that there is no clear line of demarcation between these two fundamentally different health care activities, and as the commercial influence on medical practice grows, the line between the two becomes ever more blurred.

This brings us back to the decision about how to treat Ms. Fletcher’s advanced breast cancer. It turns out that in 1996, when I had the conversation with Ms. Fletcher’s oncologist, only one small randomized trial, done in South Africa, showed that women who received high-dose chemotherapy and bone marrow transplants did better than women who received conventional therapy. Nonetheless, bone marrow transplantation had become an accepted therapy (covered by insurance), and big business. A superb article in the New York Times explained that at $80,000 to $200,000 per procedure, the service was a great lure for doctors and hospitals. A for-profit chain of cancer treatment centers, Response Oncology, grossed $128 million in revenues in 1998, mostly from bone marrow transplants. For-profit hospitals were advertising, competing for patients, and even offering to reimburse patients for their transportation costs. Academic medical centers got in on the action. One breast cancer expert told the New York Times, “Bone marrow transplanters are kings. They usually get a higher salary, they usually get more money. And more important, they have security and power.” Even community hospitals started offering the procedure. All this when nobody really knew whether the more aggressive treatment was worth the additional suffering and cost.

The Times article described the dramatic meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology that took place in 1999, three years after Ms. Fletcher received her treatment. The much-awaited results of five randomized trials of bone marrow transplantation for women with advanced breast cancer were presented. The four largest trials reported no benefit. Only the smallest study, done by the same researcher in South Africa, reported a survival advantage.

The response to this bad news provides a peek into how American health care is shaped. A press release issued by the American Society of Clinical Oncologists (including oncologists who perform transplants) said that the studies “report mixed early results.” The president of the society recommended that the therapy continue to be offered. The president of the National Breast Cancer Coalition, Fran Visco, said, “How can anybody look at these data and think this is something we should continue doing or that [the results of the studies] are inconclusive?” But Dr. William H. West, the chairman of the for-profit Response Oncology, said that it was “an oversimplification” to consider discontinuing this therapy.

One year after the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting, American researchers made a site visit to the South African researcher’s laboratory and found that his data were fraudulent. The researcher’s article was retracted by the Journal of Clinical Oncology, and he was fired from his university post. Finally, in 2000, this unfortunate chapter in medical history was brought to an end when the results of a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine failed to show any benefit from high-dose chemotherapy followed by bone marrow transplantation. The accompanying editorial laid the issue to rest: “this form of treatment for women with metastatic breast cancer has been proved to be ineffective and should be abandoned.. . .” But this was four years too late to save Ms. Fletcher from her horrific experience. She never fully recovered from the procedure, and died several months later.

Ms. Fletcher’s experience is not an isolated case. Every day wasteful diagnostic tests and therapies, from the serious to the mundane, are prescribed in the name of “state-of-the-art” health care: heart surgery for which no benefit has been shown; treatment with expensive brand-name medications when drugs costing only one-fifteenth as much are more effective; MRIs performed simply to satisfy patients’ or consultants’ curiosity (and often leading to erroneous diagnostic assumptions); expensive drugs when lifestyle changes would be far more effective at protecting health; tests and consultations that are very unlikely to lead to better outcomes. Multiplied countless times, these tests and therapies show how the U.S. health care system can be so expensive, yet not produce better results.

When I first read of the poor performance of the U.S. health care system I was incredulous. But as I confirmed these findings with data from multiple sources and began to understand the underlying causes, my skepticism gave way to a sense of vindication. I had been trained to believe that carefully reading the medical journals, following experts’ recommendations, and keeping up with continuing education would ensure that I was bringing the best possible care to my patients. I had been practicing mainstream medicine, along with a few clearly effective alternative remedies, but over the last few years, I had become increasingly aware that this wasn’t good enough.

Now I knew why. My discoveries about the myth of excellence in American health care led me to realize that the commercialization of medicine wasn’t just causing doctors to prescribe unnecessary drugs and procedures. It was actually subverting the quality of medical care. I must respectfully disagree with President George W. Bush’s comments about American health care in a speech made to the Illinois Medical Society in June 2003: “One thing is for certain about health care in our country, is that we’ve got the best health care system in the world and we need to keep it that way.” The only thing that appears to be certain about health care in our country is that we aren’t getting the health we’re paying for.