Photo courtesy of the Detroit News Archives

America is in production now.

—William S. Knudsen, January 16, 1942

A LITTLE BEFORE 2 P.M. on December 7, 1941, the phone rang in the secretary of war’s house. It was the president, who said excitedly, “Have you heard the news?”

“Well, I have heard the telegrams which have been coming in about the Japanese advances in the Gulf of Siam,” Stimson replied.

“Oh, no, I don’t mean that,” Roosevelt cried. “They have attacked Hawaii. They are now bombing Hawaii.”1

The next day, December 8, Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States. War had come to America without warning, and from both directions.

No one had quite figured out how this was going to work. At the prompting of Undersecretary Robert Patterson, the Army had finally worked out its so-called Victory Plan in September 1941, which for the first time envisaged the United States going full out in a war in the Atlantic and Europe. It still saw Japan as a problem to be put off until at least July 1943.2

That timetable had suddenly, catastrophically speeded up. Japan’s strike at Pearl Harbor had left eight battleships either sunk or smoldering wrecks, plus two cruisers and four destroyers. On December 10 the first Japanese troops landed on Luzon in the Philippines, after Japanese bombers had flattened the U.S. air force there on the ground. When Knudsen had asked General Marshall back in the summer of 1940 what was the most important thing he needed to get ready for war, he replied without hesitation, “Time.”3 Time had just run out.

On the Tuesday after Pearl Harbor, a somber Roosevelt summoned Knudsen to the White House. He had already seen Knudsen’s report on production in 1941. The numbers were impressive: 19,290 planes, 50,684 aircraft engines, 97,000 machine guns, 9,924 40mm Bofors antiaircraft guns, 3,964 tanks, and more.4 Now the president said he wanted those numbers accelerated. He needed 30,000 planes in 1942 instead of the 18,000 Knudsen and his team had projected. He wanted 45,000 tanks, and 75,000 in 1943; 20,000 antiaircraft guns; and 8 million tons of merchant shipping instead of the 1.1 million tons produced in 1941.

“Can we do it?” Roosevelt wanted to know.

“Yes, sir,” Knudsen answered at once. He and his team had figured out that 45,000 planes of all types for 1942 was not out of the question.

“And the other stuff—ships, guns, ammunition, all the other things. You can step up them, too?”

Knudsen assured him he could.

The next day, Roosevelt told the country in his State of the Union speech that America would produce 60,000 warplanes in 1942 and 125,000 the following year, and threw a couple of zeroes onto the other production numbers, as well. “These figures,” the president said with dripping irony, “will give the Japanese and Nazis an idea of what they accomplished in the attack at Pearl Harbor.”5

If those numbers didn’t shock Hitler and Tojo, they certainly shocked Knudsen’s assistants. Babe Meigs, his airplane man, was particularly miffed. “I am astounded,” he blurted out, “at the scheduling of 60,000 airplanes and 125,000 for next year. I presume this is done for propaganda purposes.” Every expert had told him 45,000 “is an all-out, almost impossible, figure to shoot at.”6 How in the world were numbers like that possible?

Knudsen told him what he had reminded the president: that he had promised Roosevelt 18,000 planes in 1941 and exceeded it. They could do this, too, now that the plants, machine tools, and small tools were up and running. “After that’s settled,” Knudsen added, “the manufacturer himself can do much more for successful production than any number of committees that can be set up”—including OPM itself.

Those numbers were a way for the president to get the maximum effort out of American industry and the rest of the country, to show the rest of the world that America meant business. “Let’s go ahead on the basis of what the president wants,” Knudsen said, “and adjust our plans” accordingly.7 America’s industrial might would do the rest.

But that wasn’t all that was bothering Meigs. Merrill Church Meigs was the ex-publisher of the Chicago Herald and Examiner, and just four years younger than Knudsen. He had grown up on a farm in Malcolm, Iowa, and worked as a threshing machine salesman for a company in Racine, Wisconsin, but his true passion was for the internal combustion engine. Racing cars had managed to gratify that urge until one day in 1927, when he learned about Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic. “I had never been on an airplane in my life,” he later said. Now he became obsessed by them. He flew on American Airlines’ first flight from Chicago to New York, and paid the airlines to fly on their regular airmail routes. Babe Meigs became the country’s first great advocate of civilian air travel, running ads in his newspaper and pushing for creating a passenger airport in downtown Chicago, only ten miles from the Loop (known today as Meigs Field).8

He passed his exam for a pilot’s license in 1929 at the ripe age of forty-six. When rival publisher Colonel McCormick did the same, Meigs did him one better by getting a commercial pilot’s license. He would offer to teach flying to anyone with a passing interest, and often did (one of his students was a senator from Missouri, Harry S. Truman).

When Knudsen’s original airplane expert, Dr. George Mead, became too ill to continue, Meigs was probably the best-known amateur aviator in America after Lindbergh himself. Babe Meigs’s intimate knowledge of airplanes, his enthusiasm, and his commanding presence and voice made him an unusual but brilliant replacement. “He could make any cloud look bright,” said one Ford executive who worked closely with him.9*

Meigs didn’t just know advertising and aviation. He also understood the ways of Washington, and worried Knudsen didn’t. So after the meeting, he went down to Knudsen’s office and explained the facts of life.

“You’ve made enemies here,” Meigs told his boss, “even though you don’t know it.” And now that America was in the war, he said, “if you think the New Dealers are going to let anyone from private industry, and you especially, get credit for this production job—”

“I don’t care who gets the credit,” Knudsen interrupted, “just so this job gets done.”

“Yes,” Meigs fired back, “I am sure that is how you feel—but they don’t feel that way. You’re my boss, and I have no business talking to you this way, but I was a publisher before I came here and I know how these New Dealers operate. They have already started to smear you, and they are getting ready to take over this defense program.”

Knudsen scoffed at the idea. But Meigs reminded him that the liberals’ dislike went further back than just the heat they were applying now. The CIO had fought bitterly with Knudsen when he was at General Motors. New Dealers didn’t like it when he had dared to criticize the Wagner Act.† They especially didn’t like the way he sought to prevent the outright conversion of the auto industry—even though Big Labor’s man on OPM, Sidney Hillman, supported his decision.

“Whether you believe it or not,” Meigs went on, “they are out to get you—and they are shooting to kill.”

“Why should anyone be shooting at me?” Knudsen wanted to know.10

Meigs could see he wasn’t getting through. But CIO conspiracy or not, the criticism of Knudsen and the OPM’s methods reached a crescendo after Pearl Harbor, starting with the unions.

“Why should the agencies of government in Washington today,” said CIO chief Philip Murray, “be virtually infested with wealthy men who are supposedly receiving one-dollar-a-year compensation?” Such men were only using war mobilization to pad their old companies’ profits and those of their cronies, the critics said. “Patriotism plus 8 percent,” they called it, while others argued that the only way to overcome the conflict of interest was to create a British-style Ministry of Supply with complete powers over all wartime production.11

Knudsen had a very different take on who posed the main threat to an all-out war effort. He knew that Sunday, December 7, was supposed to mark the start of a nationwide railway strike, until the news from Pearl Harbor intervened.12 He also knew that on December 16 a strike was called at Reuben Fleet’s Consolidated plant in San Diego, where engineers were desperately trying to get a new heavy bomber, the B-24, out the door and into the air—anyone who thought the American labor movement was going to forget its grievances in order to go all out against the Axis was about to get a cold dose of reality.

Knudsen, however, had no time to deal with critics. On January 2 the Japanese took Manila. Three days later Knudsen booked a plane to Detroit. That afternoon he assembled every automobile executive he could get hold of, including some who had been there for the dramatic meeting at the New Center back in October 1940.

He said he knew many of them were already under contract for war production, from tanks to aircraft engines. The numbers were rising rapidly; they would rise even faster in 1942. Now he was going to ask them to make one more effort.

From his pocket he pulled out a memorandum from Undersecretary Patterson. It was titled “Items of Munitions Appropriate for Production by the Automobile Industry.” He produced another from the Navy from the other pocket.

This was about getting the automakers to figure out ways to produce another $5 billion in additional war materiel that had no obvious connection with car production, Knudsen declared.

“We want to know where some of these things will flow from,” Knudsen said. “We want to know if you can make them or want to try and make them. If you can’t, do you know anyone who can?”

Knudsen put his glasses—an old-fashioned pince-nez with a thick black ribbon—firmly on his nose and began reading.

“We want more machine guns,” he said. “Who wants to make machine guns?”

A couple of hands went up hesitantly. Knudsen went down the list.

Who wanted to make turbine engine blades? “Someone ought to be able to forge these things.” More hands went up. And so on, until Knudsen had checked off every item on his list.13

A secretary recorded each company executive’s name as he made his selection. Knudsen’s friend Charlie Wilson of GM, for instance, pledged to take on some $2 billion worth of contracts, including building tanks at four different plants. Chrysler and Ford took another $2 billion, while Ford offered to help out others with the machine tool bottleneck by supplying certain simple parts for new tools.14

Knudsen was pleased, but when he returned to Washington, the outrage was palpable. Bureaucrats were shocked; commentators were volubly outraged. The director of OPM was accused of putting the nation’s defense “up for auction,” as Time magazine phrased it. The same voices who criticized what he had done wanted to know why all this hadn’t been done a year ago, so that every company capable or willing to manufacture important war materiel was already hard at work at it.

Of course Knudsen knew the truth. A year ago, a month ago, America had not been at war. No one had had the authority to compel anyone to do anything, not even participate in surveys of the national inventory of machine tools or available factory space for conversion to defense work.15 And no one had had the authority to tell industries to go ahead and retool for war work in ways that would have involved a breach of existing union contracts. Indeed, doing that would have invited even more labor trouble.

Indeed, no one had that authority even now. The consequences of Roosevelt’s refusal for the past year and a half to cede authority over rearmament to any single person or agency—his insatiable desire to keep his options open—had finally been exposed. Yet it was Knudsen’s head on the public chopping block.

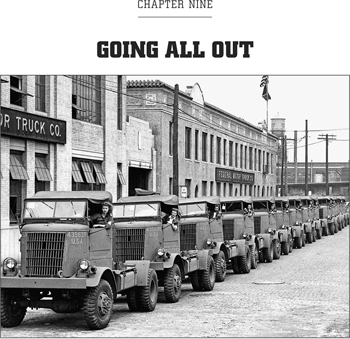

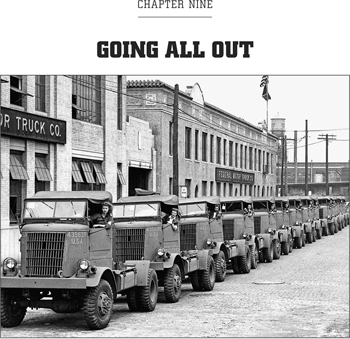

Then a new problem arose. Days after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt had given SPAB some authority to close down unnecessary civilian production. The man in charge was Leon Henderson, who was also the head of Office of Price Administration, and the industry he targeted was everyone’s favorite target, the auto industry. Henderson ordered the complete cessation of new car and truck manufacturing as of January 15. The 450,000 civilian vehicles now in the carmakers’ inventory and the other quarter million still on the assembly line were not to be sold through dealers, Henderson decreed. Instead, they would be rationed out to high-priority users like doctors, hospitals, fire and police departments, and the like.

This was the kind of bold action critics of Knudsen had been urging for more than a year. The results were exactly what Knudsen would have predicted. More than 400,000 auto workers suddenly found themselves out of work, and 44,000 auto dealers around the country had to lay off employees. Many, if not most, had to shut their doors. Instead of speeding the nation toward readiness, stopping civilian car production had led to chaos.16

Still, the blame fell not on Henderson but on Knudsen. Why hadn’t he forced Detroit to convert to war production faster, to prevent it hitting it all at once—or at least taken steps to protect these workers thrown out of work and their families, who were facing a future without a paycheck? One of the most vociferous critics was America’s best-known protector of the afflicted and downtrodden, the First Lady herself, Eleanor Roosevelt. One day, quivering with indignation, she cornered him at the White House. What was he going to do about this?

Knudsen gave her a look “like a great big benevolent bear,” she said later, “as if to say, ‘Now, Mrs. Roosevelt, don’t let’s get excited.’ ”

“I wonder if you know what hunger is?” she wanted to know. “Has any member of your family ever gone hungry?”17

Knudsen could have replied no, because he had been working since the age of eight, including setting rivets in a Bronx shipyard. He also could have told her that those unemployed workers and their families would soon enough have plenty to do, as the war production schedule he and his colleagues had hammered out began to take effect and jobs became plentiful and workers scarce, but he didn’t. Yet he would have been right.

Thanks to war work, by D-day total employment in the Detroit area would more than double. The big migraine for Michigan’s war contractors was a worker shortage as their employees headed for more lucrative jobs in the Kaiser shipyards and elsewhere. Without the migration of thousands of rural newcomers from the South and Appalachia—for whom war work represented a huge economic opportunity—it was hard to see how the big production numbers the automakers eventually made could have ever been achieved.18‡

At the time, however, Mrs. Roosevelt was not mollified. She described her encounter with Knudsen in a speech to a national meeting of 4H directors, adding this: “The slowness of our officials in seeing ahead … is responsible for the whole [defense] mess.”

Washington insiders sadly shook their heads. If the First Lady felt free to criticize the director of OPM this openly, his days must be numbered.19

Knudsen remained oblivious to what was happening. When a staffer offered him a list of talking points with which to respond to media critics, Knudsen tossed it in the garbage. He was only focused on the growing demands of his job and on January 16 was huddled with the SPAB people going over the new production numbers. At four o’clock the door popped open and a messenger handed a note to Vice President Wallace. He read it and passed it along to Don Nelson. Then both men rose and announced that they had an urgent call at the White House, but urged everyone to continue the meeting.

The remaining men talked for another hour or so, then Knudsen headed for his office. John Lord O’Brian, former federal judge and general counsel for OPM, was working down the hall. Like Meigs, O’Brian had been urging Knudsen for months to publicly defend OPM’s record and himself from the flurry of attacks in the press. O’Brian had finally gotten Knudsen to agree to go on the radio and give the American people a concise report on what OPM had achieved in the ten months of its existence, and what it was planning to do next. The live broadcast was scheduled for that evening, on CBS radio.

Suddenly O’Brian looked up to see Knudsen standing in his door with a torn piece of news ticker paper in his hand and a dazed look on his face.

“Look here, Judge, I’ve been fired!”20

It was true. The ticker paper said that President Roosevelt had announced the creation of a new defense production agency, called the War Production Board, and the abolition of both its predecessors, OPM and SPAB. The chairman of the new agency, the news report said, would be none other than Donald M. Nelson.

As O’Brian read the news, Knudsen asked him, “Let me use your telephone, will you, Judge?”

“What are you going to do?”

“Call the president.”

“I wouldn’t do that,” O’Brian warned. “Sit down, and let’s talk this thing over.”

But Knudsen had the receiver in his hand. “I’m going to call the president. I tried to get him before I came in here, and Hopkins said he had left his office and he was not to be disturbed. I’m going to call him anyway.”

O’Brian finally dissuaded him from making the call, sensing Knudsen would never get through. The only other thing left to do was to cancel the CBS broadcast. Knudsen said he had already had his secretary, Bill Collins, make the call.21

O’Brian sat with the disconsolate Knudsen until the former head of America’s defense effort went home. What hurt most was that the president hadn’t had the stomach to fire him to his face. Just a month ago, two days after Pearl Harbor, FDR had declared, “This country now has an organization in Washington built around men and women who are recognized experts in their own fields … and are pulling together with a teamwork that has never before been excelled.”22 Too late, Knudsen realized Roosevelt’s promises, both public and private, always carried an expiration date.

One of the first to get word of what had happened was Jesse Jones. He went straight to Knudsen’s Rock Creek house. When one of the Filipino houseboys opened the door, Jones found Knudsen sitting at the piano, disconsolately picking out a tune.

Earlier Jones had been on the phone with Harry Hopkins, who told him about the firing. “It was done in a brutal way,” Hopkins said. “I know it must have hurt Knudsen deeply. Get hold of him at once and ask him not to make any statement.”23 Hopkins thought they might be able to get Knudsen a brigadier general’s commission to go to the War Department to help out Patterson and Stimson with their production problems.

That was poor recompense for a man like Knudsen, Jones retorted.

“I have heard Knudsen make two-minute speeches and I have heard him speak for an hour,” Jones said, “and he is one of the most inspiring speakers I have ever heard.”24 There had to be someplace where he could be useful, not only to businessmen but to “the fellow in overalls.”

Jones stayed for dinner and tried to get Knudsen to think about the future, but the big Dane was “a brokenhearted man. I think he would rather have died than to have been ejected at so desperate a stage in the war.” Jones coaxed him into a game of cards, but Knudsen’s mind wasn’t in the game, so they stopped. At midnight Jones said he was going home. But first he found himself impulsively picking up the phone. “Give me the White House.”

With Knudsen listening, Jones got Harry Hopkins on the line.

“Knudsen will accept a three-star generalship in the Army and report to Bob Patterson to help in promoting production for wartime production.”

Hopkins was incredulous. No one could give away a military commission bigger than a one-star brigadier.

“I repeated that it would have to be lieutenant general,” Jones wrote later in a memorandum.25 Jones was used to getting his way at the White House, but it is doubtful his ultimatum would have worked—except that exactly the same idea had occurred to Stimson and Patterson. Both were less than thrilled when they heard the news about Nelson heading the new war production agency; and both agreed that Knudsen had been shabbily treated. It was Patterson who thought there should be a place for him in the War Department’s procurement system as a mobilization troubleshooter. “He’s just the man we need,” Patterson firmly said.26

So with Jones pushing and the War Department pulling, Knudsen got his appointment—the only civilian in history to be made a three-star general. “If you want me to stand sentry downstairs, or anywhere else, I will do that,” the big man told Roosevelt in their final interview at the White House. They shook hands and parted satisfied, Roosevelt because Knudsen hadn’t made a major stink about his dismissal; Knudsen because he still had a job to do, one that would take him back where he always wanted to be: on the factory floors of America.

“American ingenuity is at work day and night finding new methods of production…. American industry was raised on a free land, and the spirit of competition that built our machines, which we are now gearing up to a world-record effort, will respond if we all cooperate and keep our thoughts focused on one object—to preserve our American way of life and beat the invaders.”

The words were from Knudsen’s CBS speech to the nation, the one he never got to give.

“We build things in America—that is why most of the world is looking toward us, hoping and praying that we will come through. When we think of our boys in the Arctic or in the jungle standing up to overwhelming odds; when we think of our allies, the British, the Russians, the Dutch, and the Chinese, bravely bearing the brunt of the totalitarians; then we know the tide will turn…. America is in production now.”27

Knudsen was gone. The New Dealers thought they had won. They were too late. America was indeed in production now, with 25,000 prime contractors and 120,000 subcontractors making products they had never dreamed of making, and thousands more to come. And nothing the people in Washington or the Axis could do now would stem the tide. A new “Rule of Three” would take root in the American munitions business. In the first year after a production order, output was bound to triple; in the second, it would jump by a factor of seven; at the end of the third year, the only limits on output were material and labor—whether it was trucks or artillery pieces or bombs or planes.28

Indeed, for the Axis the issue from now until the end of the war would be trying to catch up. Too late, Hitler realized the industrial monster he faced. In May 1941 he had berated generals and industry leaders alike for their failure to coordinate their wartime needs. Germany was already spending one-quarter of its national product on munitions, and two-thirds of all industrial investment, but Hitler sensed they were falling behind in the race to the production finish line.

Four days before Pearl Harbor, he had issued a Führer decree ordering German industry to start a program of “mass production on modern principles,” which meant Knudsen principles. Hitler specifically mentioned the example of Soviet factories—but he was really thinking about the United States.29

In February the Führer named his friend Albert Speer to carry out this production miracle, as armaments minister of the Third Reich. Speer pledged that he would demonstrate to the German people that by converting their entire economy to all-out production of tanks, planes, and munitions, the Third Reich could still win the war. As armaments minister, Speer had the formal power to order which factories would produce what, and to move materials and workers to whatever industry he believed needed them—everything, in fact, that people in Washington wanted for an American production czar. He also had control over wages and prices, and the full resources of Goebbels’s Propaganda Ministry to mobilize public opinion, as newsreels began to show factories turning out munitions in record numbers—just as they were doing in the United States.

What Speer lacked was Knudsen’s secret weapon: America’s prodigious industrial base built around free enterprise, which now was giving its full attention to war production. Speer was an architect by training. He knew nothing about how to lay out a factory or run an assembly line. Likewise, Germanic pride made many key industries resist the transition to American-style mass production. Tank and aircraft factory workers remained faithful to the traditions of quality craftsmanship, as did their managers, which ensured they never made enough. The German car industry, including the Opel factories the government had seized from General Motors, sat half-idle through the entire war.§ And constant meddling and changes of priorities by the German military ensured that time and energy and materials were lost in a limitless bureaucratic maze.

Still, by stripping down every civilian factory and seizing every resource he could lay his hands on, and by grabbing every worker he could round up within the Nazi empire, Speer eventually got his production miracle. German production by 1944 surged by nearly half.30 Yet Germany would still lose the war—and in the process Speer would reduce Europe to a barren wilderness.

Meanwhile, the smoke had cleared around Pearl Harbor. No fewer than eight modern battleships—California, Arizona, Nevada, West Virginia, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Oklahoma—four destroyers, and two light cruisers were either sunk or too badly damaged to operate at sea. Pearl Harbor’s docks, warehouses, and naval facilities had been bombed and left in flames. More than one hundred planes had been destroyed, and more than four thousand Americans were killed or wounded.

Someone would have to rebuild America’s premier Pacific naval base, and get it ready for war on a scale no one had seen before. It was an ideal job for the Six Companies and Henry Kaiser. They had already had one sad reunion in January 1942 in San Francisco. Charlie Shea had finally succumbed to the cancer that had been killing him for years. Among the pallbearers were Kaiser, Felix Kahn, Harry Morrison, and Hoover Dam architect Frank Crowe. With Shea gone and buried, they threw themselves into rebuilding Pearl Harbor with a will.

Taking the lead was Shea’s old firm, Pacific Bridge, which set to work repairing the bombed-out dry docks so that the Tennessee, California, and the other crippled giants could be towed in and repaired. The Japanese bombs had left the battleships wedged against each other in their concrete moorings like broken toys jammed in a drain. Pacific Bridge’s teams joined with workers from Utah Construction to blast each concrete piling to pieces in order to get them out, while being careful not to inflict more damage on the stricken behemoths. Then more teams came in to weld on steel plate patches and make them seaworthy enough to float to safety.31

Pacific Bridge and Utah had the most taxing job, but Morris Knudsen had the most ghoulish. MK’s engineers, cranes, and bulldozers had been hard at work for more than a year on a massive underground fuel facility for the Navy, gouged out of the side of the mountain overlooking Pearl. It was still unfinished when the Japanese bombers hit. Now one of its massive pits served as a mass grave for hundreds of those killed in the surprise attack.

Out of destruction and chaos came new order. Within two weeks new runways on Ford Island had been laid out. Docks were being built that would become home to a fleet of warships four times larger than the one destroyed on December 7 (including every battleship the Japanese thought they had sunk that day except two, Arizona and Oklahoma). Thousands of workmen labored round the clock pouring cement, tons of it, all across the harbor—almost half a million barrels’ worth. As it happened, it was Kaiser cement, which Henry Kaiser had been stockpiling on Hawaii since the previous December. Now, it was vitally needed right where it had been stored.32

It was not there by accident. Three years before the Japanese attack, Kaiser’s partner Harry Morrison saw the Six Companies’ next big opening in government contracts when in 1938 the Navy decided it was time to shore up its presence in the Pacific. It was adding new airfields and submarine bases at various outposts that later would ring with meaning for Americans: Wake Island, Midway, Guam, Cavita, Samoa, and Pearl Harbor’s Ford Island.

The Navy knew someone good was going to have to build those airstrips and facilities, so it asked the biggest corporations it knew to submit bids. The Six Companies were the first.

Morrison flew out to Washington from Boise to press their case. White haired and sunburnt in his Stetson and cowboy boots, he strode into the Navy building looking like a character from a John Ford western. The board was impressed with his presentation, but it was a consortium put together by Turner Construction of New York that finally won the contract worth $15 million.

Morrison shrugged off his disappointment. He knew it was a huge undertaking, and wondered if Turner Construction and its partners were really up to it. They would have to ship materials and heavy equipment thousands of miles to remote parts of the Pacific, then import thousands of laborers and construction crews to get the work started. Even with Felix Kahn’s brother Albert supplying plans from his office in Detroit, the executives at Turner might be in over their heads. Eventually they were going to need him, and Henry Kaiser.

Sure enough, in early 1940—just half a year into the project—Congress decided to triple its size and scope. Worries about aggressive Japanese moves in the Pacific meant the work on Wake, Guam, and Samoa would get top priority, and Turner was crying uncle—their resources were stretched to the limit. The Navy called on the big man from Boise to help out.33

Morrison in turn divided up the work with his Six Companies partners. Steve Bechtel took over the work on Guam and Cavite in the Philippines; Morrison gave himself Midway and Wake. Kaiser had the easy part, supplying everyone’s cement—although he had an enormous row with the Navy when he proposed shipping the tons of his cement around the Pacific not in bags but as bulk cargo. Navy people, with visions of tons of hardened concrete in the ship holds, were flabbergasted. But Kaiser explained that it would not only be cheaper but meant transport ships could be loaded in one-fifth the time. The Navy still balked. So Kaiser silenced their objections by saying he would handle the shipping and assume the risks himself. And so in October 1940 the first shipments of cement began to arrive in Pearl Harbor, on their way to construction sites thousands of miles away in the western and central Pacific.34

On Christmas Day—the president had just given Bill Knudsen his new assignment as head of OPM, and the Arsenal of Democracy speech was still four days away—the first ship carrying Morrison’s people appeared off Wake Island. It was loaded with two thousand tons of materials and machines, in addition to towing a four-thousand-square-foot barge laden with supplies and other equipment. In command was veteran MK engineer Dan Teeters, accompanied by his wife, Florence, who would be one of only three women on the island.

The island itself was not much more than a 2,600-acre strip of sand and coral, without a single hill or natural obstruction for Teeters’s bulldozers. A cluster of huts and other buildings marked the detachment of Marines defending the tiny atoll. Yet everyone knew that in a shooting war, Wake would be of vital strategic significance. Twelve hundred miles southwest of Midway, and almost halfway from Hawaii to Manila, airfields on Wake could resupply the American garrison in the Philippines—while seaplanes and submarines could oversee the Japanese-occupied Marshalls. Teeters knew there was no time to waste, and he set his crew of eighty to work the next day.35

Six months later the number had grown to twelve hundred. By now they were joined by five hundred Marines under Major James Devereux. The work was already half-finished except for the submarine base. When Harry Morrison and his wife flew out in November, they found the place almost ready for operations. The only major job left for the airstrip was the construction of protective bunkers for the Marine planes. The Morrisons shook hands with Teeters and his wife, and greeted the workers, many of whom they knew from previous jobs. One of them was Joseph Crowe, son of Hoover Dam’s designer, Frank Crowe. They talked about Crowe’s prospects when he got back to Boise, and then had a sobering meeting with Major Devereux.36

War was almost certainly coming, he told Morrison, and Wake would be in the middle of it. The tiny island’s prospects were slim if the Japanese attacked. The Navy was ordering the women to leave, but there would not be time to evacuate all the civilian workers. As Harry and Ann took off to return to Hawaii, he must have wondered if he would ever see Teeters and his men again.

Teeters, meanwhile, wasted no time. Since not a single Marine could be spared from his duties, every available construction worker had to help with the defense. Teeters’s construction workers filled sandbags, redistributed and camouflaged Wake’s supplies, and built bomb shelters and revetments. Teeters, a veteran of World War I, pulled together 185 volunteers to serve alongside the Marines. Devereux was in no position to refuse, and soon MK hard hats were taking their place around the five-inch guns and machine gun nests, waiting for the Japanese.37

They didn’t have long to wait. On December 8, just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese bombers seemed to appear from nowhere, the sound of their engines drowned by the pounding surf until they were virtually on top of the island. The island’s squadron of Marine fighters took off but lost the bombers in the clouds as death showered down on the tiny atoll. Eight of the Marine’s twelve Grumman Wildcats were blown up, and two out of three pilots were killed or wounded. Dozens of MK’s workers were also killed in the raid. Some of the survivors panicked and fled into the jungle. But most remained at their post, and stood shoulder to shoulder with the Marines through a second raid two days later, and when the first Japanese warships appeared on the horizon on December 11.38

It was a formidable force of three light cruisers and six destroyers, plus a contingent of transport with 450 soldiers loaded for an amphibious landing. Wake’s chances for survival went from slim to none. Only two things stood between defeat and captivity. One was the Marines’ four surviving Wildcat fighters. The other was the two batteries of five-inch guns, which Teeters’s workers had reinforced with Henry Kaiser’s cement.

As the Japanese troops tried to disembark, those twin batteries ripped into their escorting ships. Four shells hit the light cruiser Yubari; Platoon Sergeant Harry Bedell’s Battery L blew the destroyer Hayate in half with three salvos. Battery B pounded away at three Japanese destroyers, scoring direct hits on two of them.

Meanwhile, the Marine Wildcats had zeroed in on the Japanese light cruiser Kisaragi. None of the young pilots had ever dropped a bomb before, even in a practice run. With sheer courage and determination, however, they scored the Kisaragi with perfect bull’s-eyes. She was already aflame from a previous hit near her ammunition storage when Lieutenant John Kinney pulled his bomb release lever and the one-hundred-pounder hurtled down. It caught the Kisaragi amidships. “A huge explosion engulfed the ship,” Kinney later wrote, “and she rapidly began to sink.”39 A cheer went up around Wake Island. They had held out, against almost impossible odds. But could they hold out the next time?

Miraculously, they did. The island was attacked every day after the eleventh except one, while the MK workers dodged bombs and lived on starvation rations. The four surviving Wildcats shrank to two, which the Marine mechanics kept going by cannibalizing parts and trying out bits from truck and bulldozer engines when the aviation equipment ran out. All America followed the epic struggle on Wake on their radios; President Roosevelt himself got daily bulletins. But on December 22, the last Wildcat was gone.

The next day, Teeters, Kinney, and the others watched a new Japanese flotilla appear, much more powerful than the first. This time there were four heavy cruisers and nearly two thousand Japanese soldiers—plus two carriers, Soryu and Hiryu, flinging in their carrier planes before the final assault. Remarkably, the Marines managed to beat off the Japanese who hit the beach on Wilkes. Captain Wesley Platt ordered his ninety or so Marines to fix bayonets and charge an enemy who outnumbered them five to one. Caught by complete surprise, the Japanese panicked and fled into the surf. Platt’s men killed almost all of them.40

On Wake itself, however, the Marines didn’t have a chance. Pounded by bombs and strafing planes, hammered by the cruisers’ guns, they were helpless to halt the Japanese advance. One of Teeters’s workmen, “Pop,” had served in World War I as a lieutenant and had been a corporate executive until alcohol had cost him his marriage and position and reduced him to menial jobs. Now he grabbed a bag of grenades and waded into the surf. He tossed them into one Japanese landing craft and then another, until he ran out of bombs, and hightailed it back to safety. Workmen and Marines cheered, but Major Devereux knew they were doomed. He fired off an urgent radio message: “Enemy is on the Island. The issue is in doubt.” A few hours later, he was told that the task force on its way to relieve Wake had been ordered back to Pearl. He tied a white rag to a mop handle and marched out to surrender what was left of his command. The battle for Wake was over.41

More construction workers than Marines had died in the fighting—forty-eight, versus forty-seven of Devereux’s hard-pressed men. Two hundred and eight others would die in the brutal conditions of Japan’s POW camps. Twenty or so were kept on Wake Island to work as slave labor for their captors. When it was clear the war was lost and Wake would have to be evacuated, the Japanese shot them all.

Dan Teeters would survive the war, despite leading a desperate escape attempt that led to his recapture and a savage beating. Florence Teeters mounted an unrelenting campaign in Washington to provide money and relief to the workers’ families. Harry Morrison, Kaiser, and their fellow contractors pitched in $300,000.42 The harrowing experience of the Wake Island workers would help to force one of the biggest changes in the Navy’s way of conducting war—the creation of the Construction Battalions, or CBs, known to everyone else as the Seabees. From now on, the men who risked their lives building on the firing line would be in uniform, trained to fight and if necessary die facing the enemy.

The fall of Wake sealed the fate of the Philippines. The Japanese were now undisputed masters of the central Pacific. Yet the sacrifice at Wake had not been in vain. Even though they never sent the radio signal “Send Us More Japs” that rumor said they did, the Marines and Morrison’s men had shown that Americans were ready to fight and die, even against steep odds.

They inspired a nation. They also sent Washington an urgent message.

Give the armed forces the right tools, and in the right numbers, and America just might win. That’s what the Army’s new head of logistics, General Brehon Somervell, was thinking about, too.

Under his boss, Undersecretary Robert Patterson, the Army had grown like a field of mushrooms. From 260,000 men in May 1940, it had expanded to more than a million, thanks to the Selective Service Act. The new U.S. Army had two armored divisions, whereas in 1939 it had none. In 1939 it had 1,500 planes. Thanks to Knudsen and his friends, it now had 16,000, and 22,000 pilots. Already, British and American war production was equaling that of the Axis powers combined.

With the coming of war, Somervell was now looking at an army that was going to expand from a projected one million in 1942 to seven million by the end of 1943. He also figured that the Army’s supply of tanks, trucks, and planes would rise to 50 percent of its Victory Plan goals by the end of 1942. That meant America would be ready to go on the offensive. Until then, he told the War Production Board in one of its first meetings, the U.S. armed forces’ job would be to keep the lines of communication open to our allies Britain and Russia.43

That made Kaiser’s Liberty ship program more vital than ever.

* Meigs, however, was more than just a booster. It was Meigs who proposed forming a Joint Aircraft Committee to standardize the parts and designs of airplanes being ordered by both the British and the Americans, including the Navy. The committee worked out how to supply the fifty-five different types of airplanes in American production with the same screws, parts for landing gears, tires, bombs and bomb releases, and hundreds of other parts—in addition to identifying which were more likely to suffer battle damage and need larger numbers of replacements and which were not. The Joint Committee’s work proved a major step forward in keeping both the RAF and the U.S. air force in the air, and a huge step toward bringing mass production to the world of aviation.

† Passed in 1934, it had legitimated collective bargaining for America’s labor unions and also immunized them from court injunctions.

‡ There were so many migrant workers from the border states that a joke began to circulate around wartime Detroit. “How many states in the Union? Forty-six, because Tennessee and Kentucky are now in Michigan.”

§ The gigantic and ultramodern Volkswagen plant at Wolfsburg, for example, started the war with enough machine tools to produce 200,000 vehicles a year. Barely one-fifth of its capacity was ever used; one worker there recalled “there seemed to be no plans at all” what to do with the rest. Later, bombing by American Flying Fortresses and B-24s made the issue moot.