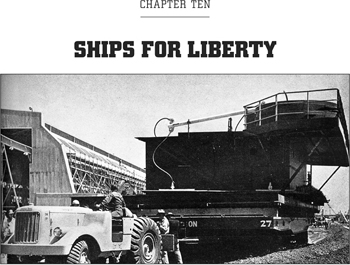

Moving a prefab deckhouse section, Richmond Shipyard No. 2, 1942. Copyright 2012, Penton Media, 84595: 112SH

We see a greater America out here.

—Henry Kaiser

“THE FOUNDATION OF all our hopes and schemes was the immense shipbuilding program of the United States.”

Those were Winston Churchill’s words, describing the situation at the start of 1942.1 Merchant ships were no longer just the lifeline for Britain in its struggle against the Axis. They were now essential to America’s ability to project its power across two oceans, the Atlantic and Pacific.

The coming of war meant big changes for the Liberty ship program, as well. How many ships were being made suddenly became a decisive factor in their chances of victory. It was American as well as British ships that were being taken out by German U-boats—more than 6.4 million tons’ worth in the first half of 1942. The Germans’ Operation Drumbeat set up patrols of U-boats to catch merchant ships as they came out of every harbor on the East Coast, their victims framed against the coastal lights like silhouettes in a shooting gallery.2

With losses like this, Knudsen’s and Admiral Land’s estimate before Pearl Harbor of needing five million tons of shipping in 1942 and seven million for 1943 looked out of touch with reality.

Something had to be done to expand the program once again—even though every shipyard in America was going flat-out building war vessels. The pressure of events, however, was inexorable. During Churchill’s visit to DC shortly after Pearl Harbor and just before Christmas 1941, the goalposts were moved yet again. The politicians agreed there would now have to be eight million tons built in 1942, and ten million in 1943.3

The powers that be brought in Admiral Howard Vickery, the Maritime Commission’s head of construction. “Can you do it?” they asked.

Vickery was a large, intense man who was most comfortable with a pipe in his mouth. He looked over the figures. “If I can get to eight million tons in ’42,” he said, “ten will be no problem for ’43.”

It was an astonishing prediction. But like Bill Knudsen, Vickery understood that the real issue was not the numbers but the momentum. Once the yards got up to a certain pace of production, increasing it would be easy. As with a marathon runner, it was the pace that mattered.

Still, existing Liberty shipyards were slammed. New ones would have to be built, and Vickery knew whom to turn to for that. On March 3 he sent seven identical telegrams to Kaiser and the other heads of the Six Companies. He asked each of them to draw up a proposal for construction of a new yard that could start producing ships in 1942. It may have seemed an impossible task, but Vickery concluded, “The emergency demands all within your power to give your country ships.”4

The first telegram he got back was at 11 P.M. that night, from Steve Bechtel. “We are studying the problem tonight,” it read, “and will give you our sincere best judgment tomorrow.” Steve put his younger brother Kenneth in charge of the task force and gave him twenty-four hours to plan out the yard and find a place to build it. On March 4, Ken showed his brother the results and Steve wired back to Washington. Nine days later the Bechtels had their contract.

The place they had found was in Marin County, on the other side of the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, near Sausalito. It was a stretch of deserted land along the shore of Richardson Bay belonging to the Northwest Pacific Railroad. The railroad leased the land to the Bechtels, the Marin County Board agreed to the terms, and on March 28—little more than three weeks after Vickery’s telegram—bulldozers broke ground.

“I’m betting on you fellows,” Vickery told them. “I expect you to produce.” They did. Even with the fierce competition for local labor from Richmond and their own Calship, the Bechtels managed to scrape up enough live bodies to put them to work in the new yard, dubbed Marinship. The marine architect described his supervisor staff as “an orchestra leader, a nightclub proprietor, and a cabinetmaker.” Some of his draftsmen had never drawn a ship before. Many of the workers were disabled.5 Still, with skilled hands on loan from Calship along with booms and equipment, and a crash seventy-hour training program for the rest, the Bechtel brothers were able to lay their first keel before the summer was out. Before 1942 was finished, Marinship would launch five ships just as promised—an astonishing feat even by Richmond standards.

All the same, if the United States was going to meet the desperate new goals, Henry Kaiser’s yards were going to be at the center of the effort.

That suited Kaiser. The month before Pearl Harbor, he and his Todd partners had bought back the Richmond yards from the British. They would be producing for the American cause now. The arrival of war only sharpened his own appetite for work, and his two key lieutenants, his son Edgar and Clay Bedford, were working flat-out, seven-day-a-week schedules to hit the numbers.6

So were their workers. The historian Carlo D’Este’s father worked the graveyard shift in the Richmond yards. He still remembers driving down at night to meet his father, with strings and strings of arc lights brightening up the sky like daylight while hundreds of workers milled around the unfinished hulks.7 A British visitor, the radio commentator Alistair Cooke, compared them to characters in a Disney cartoon, who “rush forth with welding guns and weld the parts into a ship as innocently as a child fits A into B on a nursery floor.”

Cooke had seen normal shipyards in places like Philadelphia and the Mersey in his own country. He was a bit bemused at how clean and neat Kaiser’s yard was. Everything was laid out with meticulous attention. “Sheets of steel are marked VK2 and MQ3, to indicate to a moron where they fit on a ship,” since these were workers who had never built ships before. Cranes would swing overhead to gather a sheet, lay it down where drillers and fillers would break it up into the parts traced in outline in yellow chalk, then move it on into the lofts where the real work of assembling the ship was done.8

Inside the hull, the noise could be catastrophic to a newcomer. A woman who worked as a welder at Yard No. 1 remembered when the chippers would get under way and two shipfitters would start swinging sledgehammers at opposite sides of a steel bulkhead, “and you wonder if your ears can stand it.” The sound “will seem to swell and engulf you like a treacherous wave in surf-bathing and you feel as if you are going under.” Yet after a few days she became used to it and never gave it another thought—nor thought it was strange that she could sing popular songs at work at the top of her lungs without anyone hearing a sound.9

She grew to deal with it. So did the other welders, chippers, grinders, reamers, flangers, shipfitters, loftsmen, air-compressor operators, bolters, flanger-shrinkers, plate hangers, pneumatic drill and punch and shear operators, and riggers of cranes, machines, and planes—along with forty or so other trade workers who labored to get the plates assembled, the boilers erected and installed, and the ships ready for launching.10 It was incredibly dangerous work. The same woman welder remembered having to jump three-foot gaps with a forty-foot drop below, welding torch in hand. She did it, but “my knees were a little shaky under the welding leathers.”

Then there were the swinging scaffolds. Our lady welder never quite had the nerve to try, but others learned to ride up on one scaffold as it rose, then jump to another as it swung past on its way down, without a thought—even though a slight slip meant a neck-breaking plunge to the bottom of the hull. Working out on the far end of what would be the main deck was like standing atop a six-story building, with no restraints or guardrails. There were electrical wires to trip on or to be electrocuted by; red-hot rivets to drop on a foot or 250-pound-per-square-inch metal presses in which to flatten an unwary hand or finger; plus the hazards every welder faces, of searing burns that leave arms and legs covered with scars.

All this for an average of sixty dollars a week.11

But the workers came. In 1942 the growth of the Richmond yards was explosive. In the summer of 1941, there were still only 4,000 employees working there, most living in ramshackle shacks thrown up on the barren flats surrounding the yards. Pearl Harbor brought floods of new faces, many from as far away as New York and Boston. By the end of 1942, some 80,000 men and women were employed in the yards; a year later there were 100,000. The Portland yards trailed only slightly behind in numbers. At least 60,000 simply climbed into their cars and drove across the country. Many of them were destitute laborers from the Dust Bowl states, like characters from The Grapes of Wrath. When they arrived, they found an entire city being built by Kaiser and his Permanente Shipbuilding Company, complete with restaurants, movie theaters, schools, and hospitals. Eventually Henry Kaiser even began chartering a special train service to bring prospective workers to the Richmond site.12

It was a willing workforce, unionized by prior agreement with the Maritime Commission and the AFL, and backed by a production staff who blinked at nothing. All the same, when Admiral Vickery broke the news to Kaiser and his men that they now were expected to hit 105 days for completing a ship (60 on the ways, 45 for outfitting), their minds boggled. Work on Edgar Kaiser’s first ship, Star of Oregon, was begun on May 19, 1941, and delivered on New Year’s Eve: a total of 253 days. How would they ever reach the new totals? But forty-eight hours later, they were signed on.13

Kaiser’s approach was to concentrate on pure production. It was a classic front-end philosophy. He set Clay Bedford on the case, whose teams were already building the new Richmond No. 2, while Edgar was building the brand-new yards on Vancouver Island.

Meanwhile, Edgar’s team was learning rapidly, just as Land had predicted when he said American industry could cut the production time to just four and a half to six months. They were also learning that the faster they worked, the cheaper the cost. The Meriwether Lewis and the William Clark came down the slips in January and February 1942, and by the tenth ship, Robert Fulton in March, they were down to 154 days. Howard Vickery’s goal was almost in sight.

Kaiser’s men were also learning the importance of reorganizing the supply yard so that the seven hundred tons of shapes and materials, including 50,000 castings, were always on hand when crews were ready to install them, with no pause in the production. They were also discovering the importance of getting the subcontractors to deliver their goods on time, from the propeller shaft, two water-tube boilers, and two anchors, to winches, fans, lockers, compasses, chairs, antiaircraft guns, and the six onboard electric generators. And then there was the mammoth three-cylinder, reciprocating engine, standing two stories high and weighing 135 tons of dark gray, well-oiled steel.14

Next to procuring steel plate, the engine became Bedford and Kaiser’s chief headache. Although it weighed 135 tons, the Liberty ship’s engine had an output of only 2500 horsepower. It had long since been outperformed by modern diesel and turbine engines, the ones companies like GM were making for the Navy’s subs and destroyers. It was a relic of a vanished maritime age. But the EC-2 reciprocating engine had one insuperable advantage that made it appealing to Land and Vickery. It could be built fast by a variety of companies and in a variety of conditions. Joshua Hendy Iron Works, of which Henry Kaiser was part owner and whose manager, Charlie Moore, reflected his flat-out, full-speed-ahead business attitude, became the main source for the Kaiser yards, and did it in record time and numbers.15 Before 1942 was out, the Hendy plant was building thirty-five EC-2 engines a month, or one every twenty-one hours.

But the centerpiece of the Kaiser effort was Richmond’s Yard No. 2.

In March 1941 it had been a long mudflat running along the Richmond channel, with a large marsh pond standing in the middle. The ink on Kaiser’s contract with Admiral Vickery was barely dry, however, before a tiny clapboard building appeared on the edge of the pond. The building was the field engineer’s office, thrown together in the driving rain even as Kaiser’s crew were completing their survey of the land. Bedford had put McCoon in charge of construction again, and on April 22, McCoon’s men dug a long drainage ditch to empty the pond. By mid-June they had sunk more than 40,000 piles, 12,000 for the twelve shipways to come and the rest for the massive outfitting docks and buildings where workers and subcontractors would complete the work on getting the hulls seaworthy.

McCoon brought in massive dredges to scour away 2.5 million cubic yards of mudflats in order to create a launching basin, where the completed hulls of Yard No. 2 would be shot out into the channel like bullets from a gun. Each shipway had a set of steel tracks on either side for the cranes that would do the heavy lifting, while huge steel plates were laid out between the shipways on top of a corduroy quilt of timbers laid end to end in the mud. These would provide solid, stable platforms on which the workers and technicians and welders and their supervisors could do their work around the ships—while a system of sliding roofs equipped with arc lights ensured they could work round the clock, in any weather.16

Meanwhile, McCoon dumped the silt on the marshy ground east of the basin, to create a base for sheds and materials storage. North of the shipways, the plate shop took shape, a huge gray steel-trussed building with a concrete floor for the four-ton steel plates that would become the hull subsections of No. 2’s first Liberty ships.

When it was done, Richmond Yard No. 2 covered 185 acres with a dozen shipways, each 87 feet wide and 450 feet long—the same width as the shipways Bedford had built for Yard No. 1 but a good 25 feet longer. On September 17, the crews gathered to watch the laying of the first keels in shipways 3, 4, and 5. Henry Kaiser liked to have a little ceremony for events like this, even by remote control from Washington, so more than two thousand workers and managers had gathered for the laying. Richmond’s mayor was there, as was the city’s Chamber of Commerce president, P. N. Stanford. Todd Shipyard flew in Francis Gilbrick all the way from New York—although the dealings between Todd and Kaiser Permanente were about to undergo a radical shift.17

Three weeks after Pearl Harbor, on December 31, the first No. 2 Yard Liberty ship shot down the slips, the James Otis. On board was a Joshua Hendy reciprocal engine, the very first on a Liberty ship.

Richmond’s efficient methods and frantic pace had slashed the assembly time of a Liberty ship down to 80 days. At Oregon, however, Edgar Kaiser cut the time to 71, inspiring Washington columnist Drew Pearson to dub him the nation’s shipbuilding ace. But as German torpedoes sank more and more ships, that was still not fast enough.

On February 19, 1942, there was a tense conversation in the White House bedroom, between the president and Vickery’s boss, Admiral Land. For once, FDR did not beat around the bush, and gave Land the bad news. The truth was the Allies would now need 9 million tons of new ships for 1942, not 8; and a staggering 15 million for 1943.18

Land was floored. Until now his entire reputation was based on achieving amazing results with little or no preparation, thanks to men like Kaiser, Bedford, and Moore. But now, precisely because they had succeeded, the bar was being raised to what seemed an impossible level.

“I realize this is a terrible directive on my part,” FDR wrote to Land afterward, “but the great emergency left no options.”

Land called Vickery, who was in the South looking for new shipbuilding sites. Vickery listened and said, “You know that’s impossible.”

“Yes,” Land answered, “all I said was we would try.”19

Meanwhile, the search for new sites had taken Vickery to Wilmington, to Panama City, to Savannah and New Orleans. But even if they opened a half dozen new yards, both men knew another problem was looming. Even with Joshua Hendy swinging into production, a growing bottleneck in engines and steel was threatening to shut the entire program down. Looking at the numbers, a discouraged Stacy May broke the news to Donald Nelson at the War Production Board. The Liberty ship program would never hit its goals for March.20

At the same time, public pressure was growing. Criticism in the newspapers and at the Capitol was flying thick and fast. Rumors circulated that even though the numbers had been reduced, the program was in such chaos that they couldn’t be met.

Land and Vickery were learning what Knudsen had discovered at OPM. The ability to get amazingly quick results simply bred demands for more results, and disappointment when the new ones weren’t achieved. And like Knudsen, Land and Vickery knew that labor problems, plus the shortage of steel, were at the heart of it.

As early as February 1942, Admiral Land had told Congress that strikes in 1941 had cost the Maritime Commission between seven and twelve ships—nearly 150,000 tons of shipping lost as surely as if it had been sunk by U-boats.21 And things were getting worse. In 1942 the CIO and AFL would extend their perpetual battle for supremacy to the shipyards, where clashes over membership turf would divide the workforce and cause major headaches for management, Kaiser included.22*

Then there were the stories of unproductive workers, and absentee ones. Land said bluntly there was “too damn much loafing going on in the shipyards.” Stories were told of managers finding marathon craps games in out-of-the-way corners of the unfinished hulls, and of people having full-time jobs in town and only showing up at the Richmond yard to collect a paycheck. Some said Kaiser’s yards in particular were overstaffed, and that his “soft touch” with labor made him an easy mark with workers and organizers alike. A later Maritime Commission study found that Richmond No. 1 ranked number 33 of 41 shipyards in employee attendance.23

Kaiser hit back hard. “The talk about absenteeism has been grossly overdone,” he bellowed to critics. “Let’s talk about presentism. My hat is off to the 93 percent faithful in the Kaiser-operated shipyards…. With hands and hearts they are fashioning complete victory as surely as if they were on the fighting front.”24

Eventually Kaiser’s record would silence his critics, because at Richmond Yard No. 2, Clay Bedford was changing how ships were made.

Under the traditional methods of shipbuilding, when a ship’s hull was nearing completion and the deckhouses were being added, swarms of welders, electricians, cutters, pipe fitters, burners, and joiners moved in, out, and around the action to do their job—but also getting in each other’s way. This meant the process of building a ship actually slowed down the closer it got to completion, as Kaiser’s men were finding out.

Edgar and Clay tried various ways to speed up the process. But they couldn’t avoid the fact that the shipbuilding process required doing large numbers of tasks at once, rather than in sequence like Knudsen’s auto assembly line.

Bedford decided there had to be a better way—and the place to start was the Liberty ship’s mid and after deckhouses.

He talked his idea over with Norman Gindrat. Each deckhouse was made up of separate slabs of steel averaging twenty feet long each—the heaviest weighing 72 tons and the lightest 45 tons. Clay told him to create a prefabricating shop where workmen could weld these sections together and build the deckhouses off-site. Then he and Clay would find a way to move those assembled deckhouses and install them complete, onto the hull—like snapping the lid onto a box.25

What Gindrat came up with was a mammoth 480-foot-long steel-frame shed, with two 90-foot bays with three bridge cranes in each bay, and a 150-foot run out beyond the building where the slabs of steel would be set out—and a vertical clearance below the cranes of 40 feet. Work spaces for the various crafts for outfitting the deckhouses, from joining and pipe fitting to electrical and sheet metal shops, ran along the long sides of each bay.26

Once it was built, Bedford put Elmer Hann, a veteran shipbuilder Kaiser had recruited from Consolidated Steel in San Francisco, in charge and stood by to watch.

Plates and structural shapes went from the various suppliers direct to the warehouse, and then to the prefab center by flatcar or trailer. There three conveyor belts in each bay were set up to handle three deckhouses at a time. The belt was not a belt at all, but a three-foot-high concrete platform, on which were mounted trolley wheels at two-foot intervals—and on the wheels were the enormous mounted jigs carrying the deckhouse and pulled by a two-drum 10-horsepower hoist at the opposite end.

First the decks were laid out, made of thirty-six steel plates, and double-torched and match-marked to fit. Then the plates were set on an “upside down” jig on the conveyor belt, where they were welded together by two welding machines and a pack of Lincoln 300-amp welders.27

Then came the beams, stiffeners, and other shapes that were welded in place, each cut and bent to shape in large numbers ahead of time and stored in the “angle orchard.” Then bridge cranes lifted each deckhouse and turned it right side up and onto a series of jigs, so that the bulkheads, boat decks, bridge decks, house tops—all cut, shaped, and machined ahead of time and stored in racks—as well as piping, plumbing, heating, and electrical wiring, could be installed, station by station, on the belt.28

By the time the deckhouse reached the end of the conveyor belt, it was complete in every detail, including temporary stiffeners and rigging for hoisting each deckhouse into place in the shipway. Then a retractor conveyor picked it up and jacked it up for a trailer. Each trailer was a Trailermobile weighing eighty-five tons, with thirty-two 10×15 tires. Then a Caterpillar DW10 tractor moved it to the ways, where four high gantry cranes lifted the finished deckhouse and slid it into place. Easier said than done, since coordinating all four cranes to lift at the same time took some planning and skill. But like everything else in the Kaiser yards, practice made perfect.

Bedford soon expanded this technique to include the engine room. All the one hundred sections of piping were prefab, which the pipe fitters worked together in a mock-up of the Liberty engine room, complete with a wooden dummy engine. Welders fastened down the flange at one end of each pipe with a complete weld, but the other ends were only spot-welded so that they could be disassembled, then refitted and welded into place in the actual ship.29

Assembly-line production had come to America’s shipyards. By August the prefab yard had 2,500 workers, with 42 women welders and burners—and ships were ready that were 95 percent preassembled.30 The time it took to launch a Liberty ship plummeted, while the man-hours required fell by almost half. The Kaiser yards had already found ways to reduce the time to build a ship from 220 days to 105. Now Clay Bedford was pointing the way to 50 days or less.

At Portland, applying those same preassemblies was transformational. Edgar Kaiser’s tenth ship, Robert Fulton, had taken 154 days. In April the Henry W. Longfellow finished in 86 days, and in May the James Whitcomb Riley in 73. Edgar pushed his team still harder. In July, Hull No. 230, the Thomas Bailey Aldrich, got finished in just 43 days.31

Bedford was unwilling to let that record stand. In August 1942, Yard No. 2 brought out a ship in just twenty-four days. Harold Vickery sent an ecstatic congratulatory telegram, but just as the battle of Guadalcanal was heating up on one side of the Pacific, the battle of the Kaiser shipyards was under way on the other side.

In September, Edgar one-upped Bedford. His assistant general manager, Albert Bauer, found ways to push through the preassembly envelope by increasing production per worker in every department: “More men and equipment are swung into the job,” he explained. “We simply program the erection on a faster schedule.”32 On the twenty-third the Joseph Teal was finished in just ten days. The day before launching, Edgar called Clay Bedford down in Richmond, barely disguising his glee.

“Why don’t you come up for the christening?” Edgar asked.

“Sorry,” Clay replied. “I’m just too busy down here. Can’t spare the time.”

Edgar said, “Do you want me to call my father and have him order you to be here?”33

Clay blanched. He got the message and took the first train up to Portland. He knew there was another, even more important reason he had to be there.

The president of the United States was going to watch the christening.

Roosevelt arrived there after visiting the Seattle Boeing plant and the Bremerton Navy Yard, where five thousand ship workers heard him speak with a hand microphone from his open car. After Bremerton, Roosevelt was excited to see what wonders the Kaisers were performing at Portland. He was not disappointed.

He was greeted by Henry Kaiser himself—“a dynamo,” FDR confessed later to his cousin Daisy Suckley.34 He shook hands with the man of the hour, Edgar Kaiser, who smiled his father’s smile of confidence. Clay Bedford was there, too, and got a handshake and a brief comment from the president. “I remember you from Grand Coulee Dam, when you were one of the men who showed me around there.”35

Then the president toured the great yards. His car rolled past the plate storage area, the plate shop and assembly building, and then down to the pre-erection skids onto the ways, where the Joseph Teal was waiting.

Roosevelt’s car was parked on a high ramp overlooking the christening ceremony. The president was mesmerized. As a former assistant secretary of the Navy, he could remember the long, tedious process involved in building the average ship, which Kaiser and his engineers had now cut by almost 90 percent. Out of desolate marshland, they had built, in little more than a year and a half, one of the country’s most dynamic and innovative industrial centers.

Fourteen thousand workers and six thousand onlookers watched as Anna Boettiger tried three times to crack the champagne bottle on the Teal’s prow. Finally, on the third try, she succeeded, managing to shower herself and the other dignitaries until “they were soaked to the skin,” said onlooker Daisy Suckley—as the crowd cheered and cheered.

The president spoke. “I am very much inspired by what I have seen,” he said, “and I wish that every man, woman, and child in these United States could have been here to see the launching and realize its importance in winning the war.”

Then it was Henry Kaiser’s turn. “Here beside us is this great craft,” he said, “only ten days from keel laying to launching; and in a few days she will be on the ocean bearing cargo to our allies and our soldiers. It is a miracle, no less—a miracle of God and of the genius of free American workmen.”

Later, when the president’s train pulled away and the goodbyes were done, someone asked Kaiser how long the ten-day record would stand.

“I expect that record to go by the boards in the very near future,” he said.36

He was right. As Clay Bedford rode back to San Francisco, he was already planning his next move.

Later that week the workers at Richmond No. 2 were getting off the bus and picking up their copies of the shipyard newsletter, Fore N Aft, when they found a flyer inside. “What’s Oregon Got,” it read, “That We Haven’t Got?”37

In the flyer Clay Bedford asked his crews to think of ways to regain the record they had lost to the yards up in Portland. The flyer set the Richmond crews of Yard No. 2, all three shifts, on fire. Bedford got back more than 250 letters, each suggesting ways to speed up construction.

Bedford couldn’t try them all. But he already had the dynamic key, which was prefabrication. All he had to do was speed up the process—not of putting together the ship itself, as Edgar was doing, but of pre-assembling the separate sections, so that they could be snapped together almost in sequence, like Lincoln Logs.

By now Bedford had the building of decks down to twenty-three separate preassemblies, which would then be lifted by crane into place and welded together. His engineers were now thinking they could manage to reduce that down to just seven.38

The superintendent of Yard No. 2 was J. M. McFarland. Bedford asked him point-blank: Did he think they could build a ship in just five days? McFarland charted out the process on paper and passed his calculations on to the production managers, who all agreed five days was achievable. Bedford was elated. There was only one worry. What would President Roosevelt think if the Richmond yards broke the record set by the Joseph Teal, the ship whose christening the president himself had supervised? Clay put the problem to Henry Kaiser, who put it to the president’s assistant James Byrnes. Roosevelt was delighted. “Build it,” was his response, “and if it can be built in one day, so much the better.”39

On Saturday, November 7, 1942, the preassembled parts of the “five-day ship,” Hull No. 440, were spread all over the yard. Masts, anchor chains, and deckhouses were stacked up in a confusing pile, ready to be taken down to Ship way No. 1, with more than half the ship’s components already finished. The hull was laid out in five huge double-bottom chunks, the heaviest weighing 110 tons, while the deck units came in 250-ton chunks, with piping, hatches, portholes, radiators, and even washbasins and mirrors all preinstalled. On one side stood the trusty Joshua Hendy engine, all three stories of her. The whole thing looked like an abandoned machinery junkyard.

“Five days!” said one old-timer. “Hell, it’ll take ’em five days to even find the keel.”

A huge crowd gathered as midnight approached. Superintendent McFarland, Clay Bedford, and his two sons watched as at exactly 12:01 A.M. the keel was officially laid. Then people began to realize there was method to the madness. One by one the prefabricated pieces began to disappear in the hull shell. By the time the day shift arrived at 8 o’clock on Sunday, November 8, the ship already looked a week old.40

Sunday was a day to remember, even by Kaiser standards. Some seventeen banks of welding machines were hard at work, carrying out some 152,000 feet of weld line on ninety-three separate prefab sections, while chippers were hacking away at plate ends ten at a time. “It was one seething mass of shipfitters, welders, chippers,” one worker remembered, “hose and cable a foot deep…. The biggest problem that first day,” he added, “was persuading the guys in the rest of the yard not to wander down where all the action was.”41

As the Sunday night shift arrived, the hull had taken shape and 1,450 tons of ship had been installed, including the 135-ton engine. “I’ll be blind and deaf by next week,” one worker laughed, “but it’ll be worth it.” By the end of the second day, November 9, the upper deck was done. Now other workers were arriving an hour early to watch the progress: McFarland had to send his men out to clear a path so that the next round of prefab pieces could get installed. Clay Bedford wired Kaiser back in Washington. Because of the thronging crowds, they were going to have to institute a ban on all workers not assigned to Hull No. 440 from coming down to Shipway No. 1.42

At the end of the third day, deckhouses, masts, and deck equipment were all in place. Excitement was building. This ship wouldn’t be finished in five days, they were saying. It’d be done in four. Clay Bedford gave the go-ahead to McFarland to see if he could beat his own estimate.

November 11 saw teams of workmen completing the last installations, including final welding, electrical wiring, and painting. Elated and exhausted, Bedford and McFarland watched as the final pieces of their giant prefab puzzle slid into place. Neither man had slept much in the past seventy-two hours.

Then, at 3:27 P.M. on November 12, the Robert E. Peary was launched, just four days, fifteen hours, and twenty-six minutes after laying the keel. The wife of Jimmy Byrnes, Maude Byrnes, swung the champagne bottle, the crowd roared its approval, and Hull No. 440 entered history. Six minutes later the blocks for laying the keel for the next Liberty ship, Hull No. 443, were in place.43

Bedford got congratulatory telegrams from Henry Kaiser and from Jerry Land. “Every one of you should be proud of the ship which your sweat and energy built in record time,” wrote the admiral. “Keep up the good work.” But the one that meant the most came from Edgar Kaiser and the work crews up in Portland. Their congratulations came with a postscript: “Now if we cut your record in half, what will you do?”44

Bedford laughed. In fact, no one challenged his record then or later. It remained one of the supreme industrial feats of the war.

It took another three days of cleaning, refitting, and rewiring much of the electrical equipment before the Robert E. Peary was truly seaworthy and ready for delivery to the Maritime Commission, and in the end, the accelerated schedule proved too costly to reproduce again. Bedford was already warning Admiral Land that the pace Richmond was setting (Yard Nos. 1 and 2 launched no fewer than eighteen Liberty ships in November, an average of one every other day) couldn’t be sustained because of looming shortages of equipment such as anchor chains, electrical cable, generator engines, and gauges and valves.45 Critics claimed the whole thing had been a publicity stunt, and that all Bedford had done was take two months lining up the ship’s parts and four days to slap it together—although that had been the point.46 All the same, Bedford and the men and women of Richmond No. 2 had proved that the era of mass production had come to shipbuilding.

As for the Robert E. Peary, she showed no signs of being worse for wear by being assembled in just over 111 hours. She would log more than 42,000 miles in both the Pacific and Atlantic theaters of operation, and in May 1943 set a record of her own, loading 10,500 tons of cargo in just under 35 hours. She continued to be a cargo ship long after the war. It wasn’t until June 1963 that the old ship finally headed for the breaker’s yard in Baltimore.47

The ships were ready. What went in them, comes next.

* One of the ugliest would be in the Portland yards, where Edgar became a helpless spectator to the corruption in the AFL Boilermakers Local 72. Its president, Tom Ray, not only promoted racial strife and denied promotion to women, but had spent a quarter million dollars on parties for himself and his buddies. Ultimately the National Labor Relations Board had to strip Ray of his presidency and order a new election.