I talked about the synchronicity that hits when you start writing books. People with the same name, doing the same job sometimes. Real-world events that parallel fictional ones. Here’s a true story from the publication of my second book, Epiphany. At the beginning there’s a scene where a character is walking down University Avenue in Palo Alto, northern California, and notices the strong smell of cinnamon waving out from a bakery.

Not long after the book came out in the UK I got a letter from someone in San Francisco who’d bought it while in London and loved it.

‘I particularly liked the scenes in Palo Alto,’ he said. ‘This is quite a coincidence but you know something? My grandfather owned and ran that bakery you wrote about there.’

I sent a polite and grateful reply and never told him the truth: I made it up. I never knew there was such a bakery, not consciously anyway. I knew University Avenue vaguely. I knew what kind of area it was. It made sense to put the place there, with a couple of other stores that fitted the story.

Here’s another anecdote about location that tells you something too. I was at a book signing in the mid-west of America once when a fan came up and said to me, ‘I love your books. They make me feel as if I’m right there, in Rome, alongside the characters.’

‘Do you visit Italy a lot?’ I asked.

The lady shook her head and said, ‘No. I’ve never set foot in Europe.’

When fictional locations work they spark something in the reader. There’s a sense of recognition. An act of relocation. Point of view puts the audience inside your character’s head. A successful location places them in their world too. If you can make your fictional place come alive, if your reader can’t just see it but smell it and feel it too, then half your battle in this first act is done.

Places rise from the page in two different ways, through the connections readers feel for them, and the way they’re painted.

‘I’ve never set foot in Europe,’ said the woman from the mid-west. Yet the books made her feel she was in Rome. I’d like to think some of this was down to my own skill as a writer. But let’s be honest. Rome has done quite a lot of the work for me already. It’s a city everyone’s heard of, a place we can all picture to some extent in our heads. Rome gave us much of the language we use, many of our concepts about law, justice, society, good and evil. Simply by setting my stories there I immediately forge a bond with the reader. It wouldn’t be the same if they were located in Bologna, say. A beautiful city, full of history and interesting tales. Nothing there sparks that same frisson of familiarity. That doesn’t stop anyone setting a story in Bologna, but it does mean your world doesn’t come partly built before you’ve even written a word.

Fictional locations come in four basic flavours: big, well-known places; big, little-known ones; small, unknown ones; and worlds that are created out of nowhere, fictional to the last detail. All pose different challenges but in each case you face the same fundamental problem: how do you convince the reader to step into the page and believe in the world you’ve invented? How do you make them connect?

Big, well-known places, especially those in the English-speaking world – New York, London, LA, San Francisco – look easy. There’s a reason why so many stories are set in familiar locations. They’re cinema lots, with a familiar visual appearance, waiting to be populated by the writer’s imagination. Their celebrity works against you too. Set your book in Oxford and people will soon be asking whether your version is as convincing as the one Colin Dexter created for Inspector Morse. Place a private detective in New York or LA and a whole host of established rivals will walk out of the shadows and ask, ‘You looking at me?’

Going back in time can help. Imagine a detective story set in late Victorian London. Everyone will compare it with Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes but in a way that scarcely matters. Conan Doyle has long since departed to the writing room in the sky. Holmes is out of copyright and in the public domain. You could, if you wanted, have him walk in to your story and no one will sue (though you’d best do it well or the purists will reach for their daggers). The past is a foreign country, as L. P. Hartley wrote, familiar but also malleable.

Most stories are set in the present. Pick one of those familiar, well-trodden cities and you will have to work to make it yours. There are plenty of possibilities. Set your story in a little-known neighbourhood, for example. Look at the world from the perspective of a character type who isn’t associated with the place. Invention and originality can get writers out of all manner of holes.

Big, little-known locations are problematic in a very different way. They may be provincial cities in the English-speaking world, Manchester, or Melbourne or Memphis. Or foreign places, Oslo, Beijing, Jeddah, Buenos Aires. We’ve all heard of them but, unless we have some direct experience or they’re particularly famous, as is Rome, we’ve no idea what they’re like. An author’s personal connection with a place does not translate into a connection for the reader. In fact it can be decidedly dangerous to write about somewhere you know intimately. It’s easy to take the location for granted and skip the details readers need to make it real. If you are going to set your story in a real-life place that is unfamiliar to most readers you will have to establish its look and feel and atmosphere thoroughly, and tell them why the tale is set there, not somewhere else.

Here’s the good news, though. When obscure places work they can work wonderfully, in ways that set conventional book-world wisdom on its head. Fifteen years ago anyone predicting that the next hot location for crime and thriller stories was going to be Scandinavia would have been regarded as a lunatic. Today novels set in these cold, unfamiliar and – let’s face it – unlikely climes fill the charts. There’s always hope in this business, and sometimes it lurks in the last place you’d expect to find it.

Small, unknown locations and those that are invented entirely are, to the reader, very much the same thing. They’ve no idea where they are, no clue what they look like. There’s a lot to be said for pitching your tale somewhere like this. You have free rein to do what you like without bumping up against the dead, cold hand of ‘reality’. It’s a lot easier to mess with the truth in Llandudno than in London – fewer people will know the original. Nor will there be such an expectation of ‘accuracy’, except for those who live in Llandudno, some of whom will doubtless point out the ‘errors’ in your portrayal.

There is a simple, instant answer to this kind of complaint, a whine authors get all the time. We write fiction. It’s not true. Your Llandudno isn’t their Llandudno. If that idea worries you, find a fictional name and simply think to yourself, ‘This is Llandudno really.’ While I wouldn’t worry about getting the real place ‘right’ in terms of geographical detail, I would take some care to make sure the cultural feel remains true. There’s no point in setting a story in north Wales if people speak and behave as if they’re in south Wales. That is a different kind of inaccuracy, and one to be avoided. The connections you make to unknown places need to possess the same kind of conviction that comes for free with large, familiar international locations. You’re not going to be tied by the geographical and cultural restrictions of the real world. You are going to have to work to make this invented one three-dimensional, sufficiently alive to fill the reader’s head with images of what it’s like.

The invented seaside town where Charlie Harrison has met a strange girl standing in the water beneath a wrecked pier fits into this last category. It’s been a while now since I first wrote down that story ‘seed’ and began exploring the possibilities of where it might lead. I’ve recalled the seaside town where I grew up myself. I’ve looked at photographs of a few shabby resorts. The more I mull this over, the more I think it could be a great location for the book.

It’s an old cliché in this business that locations are characters too. A true cliché for once. If you’re inventing a place it’s no bad idea to give it a quick profile just as you would for one of the players in your story. Let me do that now.

Charlie’s town (which has yet to acquire a name and may not need one) is a small, rundown seaside resort in England. It was once genteel, but the economy has been devastated as holidaymakers have moved to foreign parts. There’s little employment beyond a depleted fishing fleet working from the harbour. The pier was burned down years ago and the seafront, once a bustling tourist destination, has been reduced to a couple of squalid arcades and a few fairground rides.

In summer there are a few sad donkeys on the beach and a steady stream of impoverished visitors who turn up and don’t spend much. The grand Edwardian houses on the promenade which were once hotels and posh residences are now flats for people living on benefits, many of them asylum seekers who form a separate, mistrusted sub-group. There’s a park that’s got a dodgy reputation for drug dealing and prostitution. But when the sun shines and the sea’s fresh Charlie’s happy enough there, and loves swimming in the freezing grey sea.

Most English readers will have some experience of a place like that. So will many in other countries too. Seaside towns everywhere have a curious, seasonal character, and often slip from wealth to economic decline with a sudden, shocking ease. There’s a connection, and one is all I need.

Books are made from words. Those twenty-six letters of the alphabet and a few punctuation marks are all we have. That’s one reason we have to learn to milk them for all they’re worth. If there’s one abiding mistake that novice writers make about location it’s in the way they create that essential canvas, the living background against which their story will take place. All too often it’s approached in a very one-dimensional way, through nothing more than visual description. What the place looks like, precious little more.

There’s plenty of opportunity in the case of Charlie’s town: the beach, the colour of the sea and sky, the lines of dilapidated buildings, the closed, boarded-up pier and those blackened stanchions, like petrified crane’s legs, sticking into the water. All this will be needed but it’s only one part of a larger whole. Human beings don’t come to know their environment through their eyes alone. We use all our senses: smell and hearing and touch. Fictional worlds need to be a rich brew of sights, sounds, aromas and physical sensations, just like the environment that surrounds us in life. Description, however beautifully executed, is rarely sufficient on its own.

A seaside town offers so much when you move beyond the visual. The salt smell of the sea, the rank stink of seaweed at the foot of the pier legs. Candy floss and hot dogs, bad drains and fetid rubbish waiting to be collected. I want to hear the sound of the waves on the shingle, and I know it will be different depending on whether the tide is coming in or going out. There’ll be the jingle of the fruit machines and tinny music from the last working arcade on the promenade, the cries of the seagulls, the shouts of the bingo-callers, the drone of the engines from the fishing boats pulling out of the harbour day and night.

Seasons matter. When I set a story in Rome the time of year is one of the first things I think about. In summer the city is desperately hot and languid, in winter freezing cold and inward-looking. Romans respond to those changes in their moods, the way they live, the clothes they wear.

In Charlie’s town it’s summer and at times baking hot, the way seaside resorts can be. But I get the impression this town is on the east coast somewhere, perhaps Lincolnshire or Yorkshire. That cruel North Sea wind is going to blow at times and that will leave you shivering if you’re wearing too little. There could be morning sea mists, ‘frets’ we used to call them, which make a hot day gloomy and bone-chilling. Charlie likes to swim. He doesn’t mind the cold or the goosebumps on his flesh from time to time. The town is a part of him, and vice versa. Its icy, bleak character infects his. You could state that plainly, and perhaps will.

Charlie liked this town, admired the way the buildings on the promenade seemed to lean into the blustery wind off the sea as if to say, ‘Not with me you won’t. I don’t bend.’ All the other kids couldn’t wait to flee, to go to the big cities, to Leeds or Manchester or even London. Not him.

Even better, we can also allow his relationship to the place to be revealed through his own, private experiences.

The bitter sea fret came out of nowhere. It was as if the waves had somehow risen up and taken physical form, choking the promenade and the streets behind, casting a shroud over the long, wrecked form of the pier, enveloping its shattered frame completely. He was still in his T-shirt and shorts, shivering wildly, teeth chattering, head hurting from the numbing cold. The salty fog entered him, slid through his nostrils, his mouth, wound into his lungs, made him cough and gasp and gag the way he did when he was swimming and something went wrong, a simple mistake, sent him slipping beneath the surface, briefly out of control. This freezing fever racking his body was like drowning on dry land, trapped inside the opaque fog of the sea as it trespassed briefly, hunting for any victim it could find with its cold, damp breath.

This is where those photographs you’re collecting in the book journal start to earn their pay. I snap everything when I’m dreaming of locations: street scenes, signs, advertisement hoardings, markets, menus, people going about their lives. I go into cemeteries and photograph headstones. They’re always wonderful inspiration for character names. In small communities you can see the different tribes too, surnames that often span centuries. Looking very closely at your preferred location – in real life or through your imagination – helps seal it inside your head. You can refer back to this material later when you need it. After a while it should help make this place so three-dimensional in your own head that you can re-create it in an instant. If it’s not alive to you, it never will be to the reader.

When you’re writing a story set in a real city, one that is tightly integrated into its geography and buildings, as many of mine are, you will invariably find yourself consulting a map. Partly this is to be ‘accurate’, if you can use such a word about fiction. Maps help turn a flimsy notion into stone and bricks, streets and landscapes. If your location’s imaginary, it will still possess some geographical structure, even if it’s one that never progresses from the page.

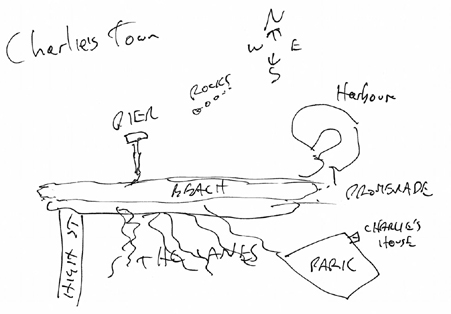

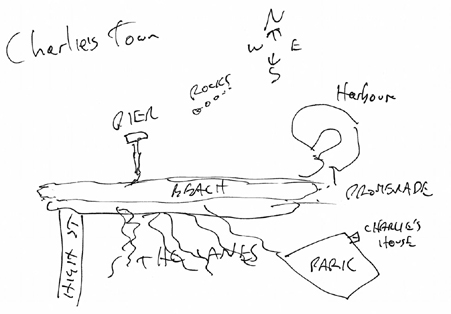

Why not sketch out a map of it yourself so that you know which way’s north, which south, the names of the main streets and topographical features, the look and feel of the place? Fantasy writers do this all the time, and their working map sometimes makes it into the final book. There’s no reason why this useful trick can’t be used by anyone who needs it. We’re not talking publication quality – just a quick sketch like this, one you can add to and amend as the story develops:

Committing ideas to paper gives you a reference point but, just as importantly, helps flesh out this world in your own imagination. The scribble above may seem meaningless but it’s not to me. I’ve a mental idea of what the harbour looks like, and that tangle of narrow alleys called The Lanes. I can begin to see Charlie’s modest terraced house overlooking a rundown park where dodgy drug dealers hang out looking for customers.

Does the town need a name? Not at this stage. If I needed one I’d look at some possibilities later, perhaps by playing with the names of real seaside towns in England. Yarborough or Scarness. It’s not important right now. But I’d probably find names for some of those streets, and perhaps an area too. If characters speak confidently and knowledgeably about places – Charlie held out his hand and said, ‘I’m going up to the chippie in Belltown. Want to come?’ – you add more bricks and mortar to that flimsy invented cosmos in your head.

Whatever kind of location you choose for your story it needs to be an integral part of the book, tied directly to the story. Here we return to a variation of the test you need to use on your dialogue, applying it candidly to your work as it progresses.

Could this story be set somewhere else? Could I move it from, say, Singapore to New York, California to Massachusetts, or Yorkshire to Dorset, and no one would much notice or care? If the answer’s yes then your world lacks conviction and substance. It needs more work.

Here’s a wonderful myth, one you’ll hear retold from writing class to university up and down the land. It’s that old chestnut … write about what you know.

I almost fall off my chair laughing typing those words. Shakespeare never set foot in Denmark but he wrote Hamlet. He almost certainly never visited Italy, yet he wrote Othello, The Merchant of Venice, Romeo and Juliet, Two Gentlemen of Verona, Julius Caesar and scattered Italian references throughout his work. Was he crippled by his ignorance? You tell me.

Writing about what you know may work for some people. For lots it doesn’t. A while back I was teaching at a writing school when someone showed me a wonderful opening she’d written for her book. It was atmospheric, beautifully phrased, had interesting characters and wound up with a dramatic and violent scene that … died on the page. I couldn’t quite believe this. Everything that went before worked fine. What should have been the denouement was written with all the verve of a business report.

I asked this budding author, ‘What happened here?’

She looked at me and said, ‘Oh, that part’s real. I do that job. I see that happen a lot. That’s how it is.’

Boring, in other words. To her anyway. Most of us take for granted what we know. We don’t see the uniqueness in what lies around us all the time. If we try to turn that world into fiction we may drain it of colour and life because it’s so familiar we scarcely notice those essential elements are there.

Except for one book, everything I’ve written has been set abroad, normally in the Mediterranean. There’s a reason for this. The Mediterranean is foreign. To a child from colder climes like me it’s exotic, interesting, cryptic, a world waiting to be explored. When I decided to write the Costa books I took the plunge and moved to Rome, enrolled at a language school to study Italian, trying to see the city through the eyes of a native. I was ignorant of the city beneath the surface. I wanted to look more deeply than was possible through some brief visit as a tourist. Most writers who use foreign locations view their stories through the eyes of a fellow countryman, an outsider. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted my characters to be, as far as I could make them, Roman through and through.

To write these books I had to turn my ignorance into an interior form of fictional knowledge, building my own private Rome, stone by stone, street by street, vista by vista, so that I could then set it down on the page. I wouldn’t have to do that if I located my book in London, a city I’ve known well for three decades. The foreignness of Rome and my ignorance of its true nature make the eventual story, I hope, more vivid and, yes, more ‘real’ than it could ever have been if I’d written about somewhere I knew intimately, somewhere I could summon up without a stroke of work.

The operative word there is ‘work’. There are books that succeed on ingrained personal knowledge, some real-life situation turned into fiction. But for the most part novels are the product of a fertile and adventurous imagination. Setting your story somewhere new, somewhere different, somewhere you have to invent for yourself, tasks your resourcefulness with the creation of a world that will come to enthral and absorb the reader. I can’t imagine doing that with the street round the corner or a place I’ve known for years.

Shakespeare wrote about what he knew in one respect: he knew people, their foibles, their strengths, their weaknesses and cruelty. That insight into the nature of humanity is irreplaceable, essential in anyone who wants to produce writing that strikes a chord with the reader. When it comes to location and plain fact then familiarity all too easily breeds contempt. Sometimes the best stories are not found at home. You have to go out and hunt them.

Just not too much.

Yes, I have cop friends. Yes, I will spend some time researching police procedure, usually in Italy. And yes, I have ways of finding out how cops would respond to a situation in real life. But I don’t hang around cops seeking inspiration or some mythical kind of accuracy for my books. I don’t feel I need to. I don’t think it would make them any better. It doubtless works for some people, but for me hanging round cops could prove to be very bad news indeed. Here are some of the reasons why.

You start to like them. A writer I know once spent six months shadowing a real police force and then wrote a book in which every cop character was so nice the editor threw it out of the window. Writers should not become overly fond of their subjects. That affection can warp your perspective. It stops you doing nasty things to them and them doing nasty things to other people. Fiction, of all kinds, is often about cruelty, our bafflement at why it happens, our struggle to stop it, our tendency to reach for the cruel button ourselves when things go wrong. Take a look at children’s literature and see how much nastiness is there.

Anything that is an obstacle to your portrayal of one human being’s wickedness to another, a portrayal which must be accomplished with the distant, aloof nonchalance of the little deity you are when writing, has to be avoided. Readers need to feel sympathy for your characters. An author requires sufficient detachment to be beastly to them, without the slightest pang of regret, should the occasion demand.

No one really cares how law enforcement agencies work, or wishes to. My stories are usually set in Italy. The law enforcement system there is so complicated that the average Italian has no idea how it functions. Two national police forces, one civilian, one military, local forces, specialist forces, an anti-mafia unit that’s not quite police depending on which way you look at it … Italy seems to invent a new law enforcement agency every year.

If I reflected ‘how things really are’ a third of the book would be spent explaining the structure of the Italian policing system. Who wants to read that? Would it make the books any better if Costa’s arrest procedures mirrored the official state police rulebook down to the last letter? Would anyone really notice? No.

Real policing happens at a snail’s pace, and that sluggishness seems to be getting slower all the time. In the UK some DNA samples can take weeks or months to come back from the lab. Statements have to go through a variety of internal procedures then are placed in front of Crown Prosecution lawyers. In fiction we tend to be obsessed with justice, nailing the culprit, finding some resolution to a tear in the fabric of society. You’d be naive if you thought that’s what police officers do every day. If in doubt, find a few and ask. The guilty regularly walk free for a variety of reasons, from insufficient evidence and an unwillingness on the part of prosecutors to bring the case to court to a procedural error or some local political difficulty.

It’s possible to write fictional stories that take these factors into account, but if you do they have to become at least part of the story. This is what I attempt in The Garden of Evil. We know very early on who the bad guy is. The book is about both the battle to bring him to justice and a broader, hazier struggle to define what, in these circumstances, justice actually is. And I tell some big lies about the speed with which forensic science can take place in that story by the way, alongside some real and accurate chunks of science too.

You can’t have the average mystery, crime novel or thriller enter the confusing, jargon-ridden and highly frustrating arena of the real-life justice system as a matter of course, running alongside the rest of the story on equal terms. If you do, the time frame of your narrative is likely to become unsupportable as your characters sit around twiddling their thumbs, waiting for the reports to come in – as real-life cops do all the time.

You’re in grave danger of forgetting what this whole business is really about. Remember what the word ‘fiction’ means? We make it up. It’s a fable, a damned lie, a warped mirror held up to the real world in order to make it appear more interesting. Readers understand this implicitly (though you’ll always get a few pedants pointing out so-called ‘inaccuracies’ – that goes with the job). It’s a writer’s imagination that makes a novel work, not his or her strict adherence to that dull old thing called reality.

There’s a wonderful saying in Italian: meglio una bella bugia che una brutta verità. Better a beautiful lie than an ugly truth. Storytellers are in the business of beautiful lies. If you want the ugly truth go and buy a newspaper. Speaking of which …

There’s a common line you see in thriller reviews sometimes: ‘Straight out of tomorrow’s headlines.’

I always wonder when I see that: does it really sell the book?

Fiction and real-world current affairs make awkward bedfellows. I had a really bright idea for my third novel, Solstice. I started writing it in 1996. That meant it was probably going to come out in early 1999. By that time millennial fever was going to be gripping the world, wasn’t it? So why not write a story about the end of the world? How cool would that be? Good timing or what?

Well, Solstice is certainly an end-of-the-world tale, but it’s not tied to any date or event in history. Just as well really. Because being topical in a book is about as dumb as you can get, as an editor cheerfully pointed out to me when I raised this possibility. Time and time again would-be writers make the mistake of thinking real-world news can generate unreal-world fiction. Mostly it can’t.

One practical problem has to do with the calendar. That thing moves on. Your book won’t. Example: the global economic crash of 2008. I’ll bet agents and publishers got a flurry of submissions in the middle of that for popular fiction set directly inside the curiously uncertain world we suddenly found ourselves in. On the surface the idea of a story from that time looks attractive. It’s everywhere: in the papers, on the TV, in people’s heads. When you start writing nothing may make less sense.

Nine months later you finish it. The crisis is still going on. People are thinking, yawn … Even worse, if a publisher accepted your book it would take perhaps twelve to twenty-four months to bring it to the public. The odds are that by then no one in the world will want to read yesterday’s news. Something else real will probably have happened that may have drastically changed the premise of your story. What publisher wants to take that risk?

Here’s a related truth too: people usually read fiction for the internal veracity of a book, not its relation to the real world. When London suffered that ghastly terrorist attack in 2005 some unfortunate soul had a book out just a week or two before, a thriller that depicted a very similar event, bombs and all. I remember someone at a book festival saying to me at the time, ‘What timing – that will sell loads.’ No it won’t, I thought. And it didn’t.

There are some recent events that are just too close for comfort. Writing about terrorism in general is one thing. Imaginary terrorist attacks are fair game too – I use one in The Blue Demon. But the real world is different. No one wants to read much about London getting bombed, about 9/11, Afghanistan (directly anyway) or swine flu. Escapism is a strong motive for picking up a book. Yes, miserable books do sell. But normally they’re miserable in themselves, not miserable about external matters we’re all miserable about already.

It’s certainly possible to set fiction around real-world events. But far better to make them something historic – the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the Bay of Pigs crisis, even the first Iraq war – than something that’s happening right now. And do remember that, if you’re lucky, that book will have a long life. You may only be able to see them a year or two out. If they work they will be around for a lot longer and may get a second wind when they’re republished a decade or so later. Tying them to some specific topical thread or event in the news is like dressing them in today’s fashions. You guarantee that very soon they’ll look jaded and out of date, of interest primarily as a curiosity.

Books exist in a space all of their own. Best to leave them there, not try to drag them kicking and screaming into ours.