By nightfall we had arrived in New Westminster, a collection of wooden buildings strung out along one broad street. Our search for a room proved fruitless—in New Westminster not even a place underneath a billiard table could be found.

“Best erect a tent, lads,” Mr. Emerson said, his pudgy hands cupped around the bowl of his pipe. Bart and I set to work, but before we were quite finished, the clouds opened and soon we were soaked through.

“Hurry, boys,” Mr. Emerson said, puffing on his pipe. Rather than help, he took shelter in a saloon doorway.

“How long do you suppose before he goes inside?” Bart asked, struggling to lift a sack of flour onto the top of a wooden box.

“Not long,” I said, tipping my head toward the now empty doorway. I swung my arms to try to warm up.

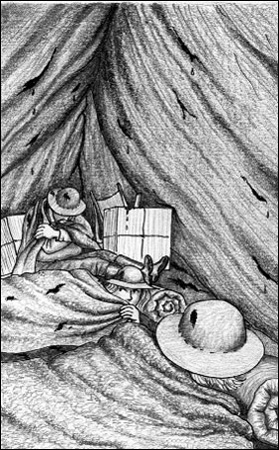

We wasted no time in pulling out our bed-rolls. Bart slipped outside to relieve himself. Back inside the tent, he rubbed his hands together and hopped up and down. Teeth chattering, he tugged off his soaked shirt and dug through his bag until he found another that was a little drier.

“You ain’t going to sleep in that?” he asked, nodding in my direction. Like Bart, I was wet as a dog that’s chased ducks into the pond.

“No. Course not,” I said, though I was stricken with the horrifying vision of stripping off my wet shirt in front of him. I had developed a certain talent at turning my back and changing quick as a wink, but in such close quarters, it was tricky to do something as simple as change a wet shirt without being seen. And recently, even my skinny body was starting to show curves in places no boy had them. I hunched my shoulders and thought fast. “I ain’t been outside yet,” I said.

Wrapped up in his blanket, Bart disappeared completely.

Another blast of rain pelted the tent. Waiting for a break in the downpour, I found a dry shirt and laid it on my blanket.

Pulling on my coat, I slipped outside, jogged a little way behind the last row of houses to find a quiet place to squat and relieve myself, and then sprinted back to the tent.

In the near darkness, the lump that was Bart had stopped shivering.

I hung my coat over a barrel and pulled the blanket around me. Awkward though it was, I struggled out of my wet shirt and into the dry one, all the while staying securely wrapped up. If Bart asked what I was doing, I would tell him I was too chilled to change without the blanket around me. Maybe Bart was too busy trying to stay warm himself or maybe he was already asleep, but he didn’t say anything and I soon burrowed deep into my blankets and concentrated on nothing more than warming up.

Near everything we owned was wet, and we slept very little as streams of water dripped through the canvas tent on all sides. Bundled in our increasingly soggy blankets, Bart and I rolled from one side of the tent to the other in search of dry ground.

Mr. Emerson was oblivious to the miserable weather. When he staggered into the tent in the wee hours of the morning, the stink of whiskey and tobacco was thick on his breath. He did little more than tug a blanket around his shoulders and his hat down over his eyes. Propped against a crate of tools, he fell into a drunken sleep and didn’t awaken again until Bart and I had loaded most of our supplies onto the Colonel Moody, the riverboat bound for Port Douglas by way of the Fraser River.

I was pleased that Mr. Emerson had decided to splurge on the riverboat fare. Like every-one said, it wouldn’t be long before we would come to the end of the road, so to speak. Riverboats could only go so far before rapids made it necessary to continue by foot.

For a day and a night, we traveled like kings, a role Mr. Emerson seemed happy to play.

“Magnificent,” Mr. Emerson declared on a regular basis during the first hours on the river. Despite the thick head and swollen eyes caused by his late night of whiskey drinking, he felt compelled to share his observations with anyone who would listen. “That there is Mount Baker,” he declared, waving his unlit pipe toward a snow-capped peak to the south of us. “In United States territory.”

Bart and I weren’t the only ones to breathe a sigh of relief when Mr. Emerson pulled his hat down over his face and fell asleep in a sheltered place against the cabin wall.

When his head slumped forward and the snores began, Bart and I slipped away and joined a group of younger men who watched the water splash over and off the great paddle wheel as it pushed the boat steadily up the river.

“How far away is Douglas?” I heard one man ask another.

“Twenty hours out from New Westminster,” an-other answered. “The Colonel Moody’s the fastest boat on the river. My guess would be we’ve got sixteen hours to go.”

“Want to look around?” Bart asked.

I nodded and we explored the Colonel Moody from one end to the other. The most exciting place was on the forward deck where a group of men gathered in a half-circle around a dice game.

“Dice?” one of them asked as we stopped to see how the game was going.

“I’d like to play,” Bart said as he squatted beside the other men. “If you remind me of the rules.”

“What’ve you got?”

Bart dug in one of his pockets and pulled out a few copper pennies. From another pocket he tugged a crumpled kerchief. I had seen Bart play this game before. He pretended to be a poor orphan who hardly knew how to play. I hid a grin. There was no need to tip the men off.

“I got a little more money,” Bart said, “but not so much as I want to give it to the likes of you.”

“That’s hardly worth bothering with— “said a man with a face as slack and pale as a dead man’s. “But what of it—we ain’t got nothin’ better to do than take what you have to offer us! And you?”

He looked at me and shot a thick stream of tobacco juice past my knee.

“No sir, I don’t have much. Ask again when we travel back down the river.”

“You’ll be a rich man then, will you?” the pale man asked.

I shrugged. Why else would I be on this boat? Why would any of us be here if it weren’t for the gold that lay ahead, ready for the collecting?

“You’d be better off to take a chance with your pennies here—like your friend.”

“Throw then, Black. We ain’t got all day.”

The man with the pale face rolled the dice between the palms of his hands. He closed his eyes, cupped the dice in his hands, and blew a puff of tobacco breath between his thumbs.

“Mary, watch over me,” Black said, and he rolled.

Four hours later, Bart had parlayed his four pennies into nearly five dollars. I badly wanted to leave but couldn’t—it seemed like every man on board had crowded around the game.

“Black, you won’t have enough left to stake a claim, never mind feed yourself!”

“Shut your gob, Williams. You don’t know what you’re harping on about!”

“Two bits the boy don’t win the next one!” Williams countered, and several voices answered with “Three he does!”

After each roll of the dice, money changed hands, and the piles in front of the main players grew and shrank. Knees pressing into my back and boots planted either side of my backside meant I couldn’t put my hands down or move without being stepped on.

“That’s it!” Bart finally said when he had won nearly a whole dollar more.

“Coward!” Black said. “Play again!” Black stood square in front of Bart, one hand on his chest.

Bart said nothing as he dropped the coins into the leather pouch on his belt.

“I said, play again.”

“Maybe tomorrow,” Bart mumbled.

Black’s hand closed on Bart’s shirt and pulled him close.

“Boys shouldn’t play games with men if they ain’t ready to lose.”

“Black—you’ll get another chance at the boy. Here—have some of this,” Williams said, his hand on Black’s arm.

A bottle passed between them, and Black lifted it to his mouth.

Bart seemed stuck to his place, so I grabbed his arm and pulled him away. “Hungry?” I asked.

That got him moving. “Sure am,” he replied.

The men parted to let us pass, and then the shouts and jeers started up again.

“Who is man enough to step up and play?” Black asked. “And don’t think you can walk away like that boy. I’m happy to have men, real men at the table—but cowards! They ain’t got no place —”

The rush of wind as we came around the wall of the cabin drowned out his ranting, and we made our way back to where we had left our things. Mr. Emerson was nowhere to be found.

“Wonder where he is?” Bart said.

“Can’t have gone far. Boat’s not that big.” But neither of us made a move to find him.

We pulled a loaf of bread and a lump of hard white cheese from our packages. “May as well stay right here with our things,” Bart said.

I nodded. Fact was, I knew Bart was scared. Not that he wasn’t brave—he was. Nobody could ride the Pony Express without being brave. But Bart was no fighter, and Black wanted his money back. My pa used to say that no man should wager who wasn’t willing to lose.

“I’ll sit up awhile,” Bart said after we had both tugged our blankets out onto the deck. The spring sun hung in the sky until late, and it still wasn’t fully dark when I lost myself to sleep.

When I rolled over at the first hint of daylight, Bart was still sitting up, leaning against the wall of the wheelhouse, his hand protectively covering his poke full of Black’s coins.

“You want me to sit up a spell?” I asked.

He shook his head. “Go back to sleep,” he said. “No sense the both of us feeling like there’s sand coating our eyeballs!”

I would have argued, but the words didn’t even have time to form on my lips before the toe of Mr. Emerson’s boot was in my side. “Git up. We got work to do.”