The next day Mr. Emerson was adamant that we push on. But late that morning when we found ourselves struggling to free Honey from where she lay belly deep in a swamp, I think we all regretted not having had a better rest at Williams Lake.

“You poor beast,” Joshua murmured, giving the sorrel mare a pat on the neck. “Let’s give her a hand,” he said.

Nigel and Bill held ropes attached to either side of Honey’s halter to hold her head up out of the water. Careful not to plunge into the deep spot where Honey had sunk, Joshua eased his way to her rump with another rope in hand. Reaching down into the water behind her, he passed the rope over to Mr. Emerson, George and a fellow by the name of Louie on the far side.

The rest of us watched, swatting at the cursed insects swarming everywhere. They crawled over our skin and into our noses, eyes and ears. Some were flies so small you could scarcely see them, though their bites were almost as bad as those of the monstrous horseflies.

“Ready?” Joshua asked.

The men at the mare’s head nodded. Mr. Emerson’s eyes narrowed.

“One. Two. Three.”

The men heaved on the ropes and the exhausted horse, still fully loaded, struggled out of the deep hole and staggered forward to come to an unsteady halt just a few feet farther on.

The mare didn’t even bother to shake herself but stood, head down, panting.

“Good girl,” Joshua said.

I raised my hand to shade my eyes from the sun. The swamp stretched in all directions as far as we could see. The only way to get through this horrible place was to try to step from hump to hump of drier grass. But the humps were often small and unsteady, and unless one were quick and nimble, sliding off into the swamp was a regular occurrence. The going was painfully slow, made all the worse by the clouds of insects that buzzed, hummed and bit.

It was bad enough to drive a good man to drink. It was so bad that we lost a horse, which was unable to get up after he slid into the mud, despite three ropes and eight of us hauling on him to get him going again.

Joshua cut the horse’s pack free and, without speaking, we divided up as much of the load as we could carry and continued on, not even looking back when the crack of a rifle signaled the end of the horse’s life.

“I wouldn’t have believed that anything could make me think the swamp looked good,” Bart said. After hiking up and around a steep hill thick with trees and down into a ravine on the other side, we had come to a dead stop at the end of a rickety log bridge. The water was so high it licked at the bridge, splashed and spilled over the slick logs, white bubbles frothing and foaming as we stood and stared.

“We could stop here,” Louie said, though it was impossible to make camp on the narrow ledge beside the angry creek.

“Don’t be a damned fool, Louie,” Mr. Emerson said. “Get on over the bridge.”

At that moment we heard a shout, and four men, bedraggled, bearded and carrying little more than their bedrolls on their backs, staggered out of the trees on the other side of the ravine.

“Hold up!” the first in line shouted at us over the roar of the raging torrent below.

It seemed that nothing could stop those men as they ran across the bridge.

“Turn back,” the first one urged as he moved past us. “Ain’t nothin’ there worth dying over.”

Bart took hold of my forearm and watched the four men pass us without even a backward glance. I knew he wanted to go with them. I could feel it in the way he gripped my arm. The very idea that Bart might leave filled me with a dark dread.

Two men from our party turned and trotted after the retreating miners.

My mouth went dry and my heart raced, as if I were the one running back down the trail. If Bart turned now, would I stay or would I go?

“Bart,” I said, “we’re almost there—” I choked back the pleading words that threatened to flood the space between us. Bart knew as well as anyone the risks as well as the rewards. He had to make his own decision, just as I had to make mine.

“Boys—help Joshua get these animals over the bridge.” For once I was glad to do as Mr. Emerson commanded. I turned away from Bart and back to the bridge, my heart skittering and jumping beneath my ribs.

Bridge. To call it a bridge was madness. To think horses could get across was insane. If Mr. Emerson thought it was such a fine idea, he should lead the animals over.

“With respect, maybe we should see if there’s a better place to—”

“Who’s paying your wages, Joshua?”

“Sir, these animals —”

“These animals will do what you tell them.”

Joshua’s hand closed on the lead rope of one of our four remaining horses. He looked skyward and his lips moved in silent prayer.

“Come on then, Laddy,” he said, giving the rope a gentle tug.

To my amazement the horse followed him over the bridge like a giant dog. He placed each foot cautiously, warily balancing himself and his burden one step at a time until he reached the other side.

The other three horses lifted their heads to watch.

“Come on—one of you has got to come over here and hold Laddy.”

I hesitated for only as long as it took to decide that this was not the end of the trail for me. If Bart followed, it would be on his own account and not because of anything I might have said. Even though I knew this was how it had to be, it took every ounce of willpower I possessed to step onto the bridge and cross without looking back.

Honey was next, followed by Louie. Heart still thumping, I watched the progress of the horses and in silence offered a quick prayer that Bart would choose to continue.

Jacko, the third horse, made it over. One by one the other men wobbled and swayed across the bridge, arms out for balance, faces stern with concentration. When, at last, it came to Bart’s turn, he too stepped onto the log and I muttered, “Thank you.”

At last, only Tucker and Joshua remained alone on the far side.

Convinced he was going to be left behind, Tucker snorted anxiously. “Steady now,” Joshua said to the horse. “Watch where you’re going.” They stepped onto the bridge.

At first I thought it was going to be all right, but when yet another group of men burst through the trees, Tucker threw his head up, his nostrils flaring.

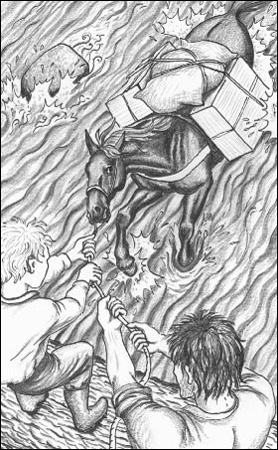

That was all it took for one back hoof to slip off the side of the bridge. His heavy load and exhaustion did the rest. He slithered backward into the churning water, and Joshua threw himself in the other direction so the rope snapped taut over the edge.

Bart and George grabbed for the rope, and the three men yanked and hauled against the weight of the thrashing horse. They did everything they could to hold the panicking animal. Mr. Emerson pulled a length of rope from a pack and scrambled down the steep bank.

“Stop!” I yelled when he landed the first blow on the horse’s back.

If he heard me over the roar of the churning water, he didn’t let on. He lashed the poor beast over and over again, as if by sheer brute force he could will the animal to rise from the water.

Tucker gave one last mighty spasm and then went limp, the water buffeting his hindquarters where they hung in the raging stream.

I turned away, sickened.

“I can’t take no more of this,” Louie said. “You fellows got room for one more?”

The men who had startled Tucker nodded and then, as if nothing untoward had happened, made their way over the bridge, Louie right behind them. Without a word of discussion, several more men from our party followed.

“Cowards!” Mr. Emerson said, gasping. He was bent over at the waist, puffing as if he had run a mile. He straightened up, coiling his rope as he did so, and looked over the rest of us. “Anyone else want to go? Do it now. There is no place in this godforsaken land for weaklings.”

Beside me, Bart stiffened, but he held his ground. If the circumstances hadn’t been so grim, I might have smiled.

As Joshua struggled to cut the dead horse’s burden free, I no longer thought only of my dreams of gold. Yes, gold lay hidden in the rivers and mountains, but in that moment, watching the men salvage what goods they could from the dead horse, I knew that I could leave Mr. Emerson without a shred of guilt. I also knew that I would not abandon Bart. If he decided to return to California, I would travel with him and see him safely back to Emily Rose.

“We’d best be going,” I said, sternly keeping the quaver from my voice. “We’ve got to get these horses a place to rest and eat. Bart? Will you come on ahead with us and find a place to camp?” I turned to Joshua, who was still struggling at his grim chore on the bridge. “We can leave Jacko with you so you can pack on a few extra things.”

Joshua nodded, and Mr. Emerson, having coiled his rope, pulled out his pipe for a smoke.

With one last look at the place where the deserters had disappeared, Bart took the halter rope and we trudged off, leading the two exhausted horses away.