Preface

Ernest Gowers was born in 1880 into a well-heeled London family. His father, Sir William Gowers, was a celebrated neurologist, one of the founders of the discipline, whose immense body of work on the subject is today described by Oliver Sacks as ‘matchless’. But this work—minute, illustrated observations of disorders ranging from syphilis to writer’s cramp—was not the only comprehensive record he left behind. He also kept delightful accounts of all the larks and entertainments that he provided for Ernest and his siblings. They went to the river for steamer rides, to Lord’s for the cricket, to the Zoo to see Jumbo the Elephant, and to the Egyptian Hall for performances by the amazing automaton artist, Zoe; they took in magic displays where people’s heads were cut off, ladies disappeared and electric storms ripped round the room; they even visited the famous Wild West show, where Annie Oakley shot glass balls out of the air while Buffalo Bill commanded massed ranks of rough riders.

But these pleasures had been hard earned. William Gowers’s own upbringing was impoverished by comparison. His father, a Hackney bootmaker, died when William was only eleven, catapulting the boy into a world marked by graveyards, gun shops and gelatine factories. This misfortune for the child, compounded by the death of all his siblings, seems to have led him to seize almost with desperation on whatever chances came his way. There is scant record of his early education, but he started his career in medicine aged sixteen as the apprentice of a country doctor, at the same time studying by correspondence for the London University matriculation. Diaries he kept at the time show him to have been exhausted and sometimes harrowed by this existence, one requiring an effort of will on his part of a kind we now associate with the young Charles Dickens. And it is therefore perhaps little surprise that when the time came—beyond the cowboys and elephants and other jollifications—Dr Gowers would take great care over the formal education of his sons.

Ernest Gowers was sent to Rugby in 1895. He went on to read Classics at Cambridge, and in 1903 passed what was by then a genuinely competitive exam for the Home Civil Service. Though he also soon afterwards qualified as a barrister, he did not take up law. Instead, he remained in the Civil Service, advancing rapidly, until in 1911 he was appointed Principal Private Secretary to Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer.

This was, as Gowers would later recall, a stormy period in which to take up post. Lloyd George was attempting against the odds to usher a ‘socialist’ National Insurance Bill through Parliament: he faced virulent public opposition, not least from the British Medical Association and the Northcliffe Press. And getting the Bill passed was merely the start. In short order, Gowers found himself one of a crack team of young civil servants charged with the immense task of making the resulting Act work. These young men were nicknamed the ‘loan collection’ because they had been drawn from across several departments, but Gowers called them a ‘desperate remedy’. Not only were they being asked to implement from scratch an entire system of health and unemployment insurance, and somehow to explain its complexities clearly to the public, but they were also being required to do so in a matter of months. Difficult as this task was, however, those to whom it had fallen would soon view it as having been good preparation for the yet greater challenges that came with the outbreak of war.

In 1914 most members of the loan collection were reassigned. Though Gowers continued to work at Wellington House, the building where the National Insurance Commission was based, this was now a front: ‘Wellington House’ became the code name for a covert propaganda unit. Gowers started as its General Manager, but within a year had risen to the position of Chief Executive Officer. The job of the unit was to make the case for going to war. Many writers secretly agreed to give their services, among them H. G. Wells, J. M. Barrie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, John Buchan, Arnold Bennett, A. C. Benson, Robert Bridges, G. K. Chesterton, John Galsworthy, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, Henry James, Hilaire Belloc, Rudyard Kipling and Thomas Hardy. A. S. Watt, the prominent literary agent, was drawn in both as an adviser and as a go-between conducting undercover negotiations with sympathetic publishing houses. It was important to the credibility of the works sponsored by the unit—initially books and pamphlets, in many languages—that its existence should remain unknown. Within nine months ‘Wellington House’ had more than ninety titles in print, with two and a half million copies of these titles circulating at home and abroad.

When the war ended, Gowers was appointed permanent head of the Department of Mines; his working life between the wars would be almost entirely devoted to coal. He was knighted for these labours, but found the work intensely frustrating. The coal owners left him, he said, in ‘despair’: he described the ‘force of self-interest’ among them as ‘centrifugal’. He was relieved, therefore, in the aftermath of the General Strike, to be given three years as Chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue. There he began a campaign to ensure that tax officials should seem approachable and should be easy to understand in their letters to taxpayers. But he was soon returned to coal.

Only when the Second World War loomed would Gowers again be diverted, asked to give some of his time to planning for civil defence. Then, very shortly after the war began, he was appointed Senior Regional Commissioner for London. What this meant in practice was that for almost the whole of the war, and the worst of the Blitz, he coordinated the civil defence of the capital.

His base was a bunker beneath the Geological Survey Office at the Natural History Museum. Churchill’s instructions to him were daunting: ‘If communication with the Government becomes very difficult or impossible, it may be necessary for you to act on behalf of the Government … without consultation with ministers’. In this event—particularly if the Government had fled London—it would be Gowers’s duty to govern the city directly himself. Its seven million people would be his responsibility, and he could order any emergency measures he thought fit. ‘Such action, duly recorded,’ explained Churchill, ‘will be supported by the Government, and the Government will ask Parliament to give you whatever indemnification may subsequently be found necessary.’ Gowers speculated in a speech of 1943 that if he were ever forced to assume these powers, the matter would end with him dangling from a lamp post. His bunker was supplied with three separately laid telephone lines, and he could only hope that they would never all be blown up at once.

Gowers wrote after the Blitz, ‘Everyone expected that we should infallibly be bombed like hell’, but noted that, despite this, when the war actually began, London was ‘thoroughly unprepared’ because ‘what had to be prepared for was unknown’. If it was impossible to work out in advance all the measures that would be needed in any attempt to counter the damage done by the bombing, it was equally impossible to grasp ahead of time the huge administrative challenge of implementing these measures. Gowers was forced to take swift decisions in what he called ‘hideous’ and ‘desolating’ circumstances with very little useful precedent to guide him; but he would come to be praised for the inspiringly imperturbable way in which he went about his duties as Commissioner. When he wrote later about his admiration for the Londoners he had served, he said simply this, ‘We withstood’.

Gowers, writing in the midst of war, described himself as ‘but a transient and embarrassed phantom flitting across the stage of history’. Once the war had ended, his name was added to a Treasury list of those increasingly referred to as ‘the Great and the Good’, people who were thought suitable for such posts as chairing advisory committees and Royal Commissions. Several of these appointments came his way in quick succession. He chaired the New Town Development Corporation for Harlow, one of the towns built to relieve homelessness among London’s bombed-out East Enders. He also chaired a wide array of committees. One investigated allowing women to join the Foreign Service; another, shop opening hours; a third, the preservation of historic houses; a fourth, measures to combat foot-and-mouth disease. Most prominently, though, starting in 1949, he chaired a Royal Commission into Capital Punishment. The Commission was asked to consider whether there were rational arguments for imposing tighter limits on Britain’s use of the death penalty, but Gowers controversially breached these terms in the Commission’s report, where he raised the idea that the best policy might be—as he found himself passionately believing—to abolish it altogether.

PLAIN WORDS

Gowers undertook his many chairmanships at the same time as doing the work for which he was destined to be best remembered. He had spoken out about baroque official English at least as early as 1929, when he remarked in a speech that he gave on civil servants:

It is said: first, that we thirst for power over our fellow-men and lose no opportunity of sapping the freedom of the public by extending the tentacles of bureaucracy; secondly, that in our administration we are unimaginative, rigid, cumbrous, and inelastic; and thirdly, that we revel in jargon and obscurity.

Gowers agreed at least in part with these criticisms, and he returned to the theme in a talk that he gave in 1943 to civil defence workers. There had been a fear, once a lull set in after the Blitz at the start of the war, that the various civil defence services would be unable to keep their members at ‘concert pitch’ against further aerial bombardment (which was indeed to come). Gowers’s talk was one of many designed to entertain these workers and keep them from getting too ‘browned off’. He pointed out to his audience with humorous regret that, in the innumerable circulars they all received daily, examples of verbal ‘mistiness and grandiloquence’ were ‘as plentiful as blackberries’, and argued for a new style of official writing, both friendly and easy to understand. These comments caught the attention of Whitehall, and three years later the Treasury invited him to produce a training manual for civil servants on the art of writing plain English.

The slim volume that Gowers first produced on the subject was deemed by those who had commissioned it to be a success, so much so that the idea was mooted that it should now be published as a book for general sale. Gowers was offered a flat fee of £500—normal for the time and even generous by Treasury standards. But he demurred, turning for advice to his old friend A. S. Watt, the literary agent with whom he had worked secretly on propaganda during the First World War. With Watt’s encouragement, Gowers asked instead for a royalty. The Treasury was enormously displeased by what would come to be characterised as his wish to have a ‘flutter’. Letters went back and forth. Acid remarks were scribbled in the margins of file notes. When at last Gowers won the day, the decision was unprecedented. One of those negotiating with him wrote to him in a letter, ‘Like you, I hate arguments about money—although I must admit you do it frightfully well’.

Plain Words was first published in April 1948 by His Majesty’s Stationery Office, which crucially had access to paper supplies. By Christmas the book had gone through seven reprints, selling more than 150,000 copies. The Treasury, surprised and encouraged by this, asked Gowers to write a new book, an ABC of Plain Words, designed as a reference manual with its entries arranged in alphabetical order. When this work came out in 1951, it too was a success, again taking the Treasury by surprise. Nearly 80,000 copies sold in the first year alone, even as the earlier work continued to sell: by this point Gowers’s ‘flutter’ had netted him roughly ten times the sum the Treasury had first offered. But though the ABC did well, Gowers was unhappy with its layout, believing it to be an awkward fit with his more discursive notes on style. The best answer, all agreed, would be to find a way to combine the ABC with the original Plain Words, creating a new book under the title The Complete Plain Words. When this third, definitive version of Gowers’s work came out in 1954, it was yet again swiftly a bestseller, rapidly taking the total sale of the ‘Plain Words’ titles to well over half a million copies. Remarkably, it has remained in print ever since.

Taxes, May 1948

In 1951, after an approach from Oxford University Press, Gowers agreed in principle to be ‘a sort of ganger’ overseeing a party of workers engaged in the monumental task of revising Henry Fowler’s idiosyncratic classic, A Dictionary of Modern English Usage. After hesitations that lasted half a decade, OUP went further and asked Gowers to be the editor. He accepted this commission at the age of seventy-six and finished the job when he was eighty-five. A year after his edition of Fowler was published, Gowers died of throat cancer caused by a lifetime of smoking. Not long before, however, in an interview with the New Yorker, he remarked with typical good humour that although living such a long life was ‘all rather deplorable’, his recent labours had given him ‘rather the sensation’—an agreeable one, he admitted—that he would be going out with ‘a bang’.*

THE COMPLETE PLAIN WORDS REVISED

Had Gowers survived a little longer after revising Fowler’s work, he might have revised his own. He had discussed the idea with his publisher, writing, ‘there is quite a lot in the book that I should like to alter’. But with his death, The Complete Plain Words languished, and it was several years before another civil servant, Sir Bruce Fraser, was invited to take on the job. In Fraser’s preface to the second edition, published in 1973, he called Gowers’s work elegant, witty and ‘eminently sensible’, and explained that he had tried to keep the flavour and spirit of the original. In a line he threw into Gowers’s own prologue, Fraser compared ‘flat and clear’ writing to ‘honest bread and butter’, and warned against spreading it with either the ‘jam’ of eloquence, or the ‘engine-grease’ of obvious toil.

There was no question, two decades on, that the book needed an overhaul, and Fraser had a good go at it, supplying some excellent new jokes (‘I have discussed the question of stocking the proposed poultry plant with my colleagues’). But in his cheery assault on the text, he went considerably beyond the bread-and-butter plainness that he himself advocated. He introduced into the book the phrase ‘the guerdon of popular usage’, spoke of ‘flatulent’ writing, and described Hemingway’s imitators as sounding as though they were ‘grunting’. Where Gowers had written about the attraction between certain pairs of words, Fraser wrote of words that ‘walk out with other charmers’. He coined the needless term ‘pompo-verbosity’, only to contrast it (to no understandable effect) with ‘verbopomp’; and in order to shoehorn ‘verbopomp’ into the text, he took out ‘Micawberite’, a word Gowers had used, not unreasonably, after quoting Mr Micawber.* So it went on. Towards the end of his edition, Fraser threw in a sentence criticising writing that reminded him of ‘an incompetent model flaunting a new dress rather than a sensible woman wearing one’. But he himself was far from a perfect match for his imaginary sensible woman.

The most unfortunate single sentence that Fraser added to the book, one for which there is no evidence Gowers would have felt the slightest sympathy, was this:

Homosexuals are working their way through our vocabulary at an alarming rate: for some time now we have been unable to describe our more eccentric friends as queer, or our more lively ones as gay, without risk of misunderstanding, and we have more recently had to give up calling our more nimble ones light on their feet.

Fraser first makes the vocabulary of English ‘ours’ and not ‘theirs’, then imperiously blames homosexuals for hijacking ‘our’ vocabulary. Even had this claim to ownership of the language been legitimate, the blame was misconceived: the word queer only came to mean ‘homosexual’ because those whom he calls ‘we’ made it a derogatory term, while ‘light on his feet’ was an insult designed to imply that a man was suspiciously good at dancing. For all that, the second edition of The Complete Plain Words was a success, and many readers preferred it to what came next.

The third edition, published in 1986, and edited by the linguist Sidney Greenbaum and the lexicographer Janet Whitcut, showed evidence not of Fraser’s ‘jam’ so much as of the ‘engine-grease’ that he considered equally dangerous. It was Greenbaum and Whitcut’s idea of being judicious, for example, to amend Fraser’s comment above so that it now began: ‘Homosexuals and lesbians are working their way through our vocabulary at an alarming rate …’. It is hard to imagine one editor making this change, let alone a second agreeing to it. It is even harder to imagine lesbians being grateful for the nod.

Greenbaum and Whitcut revised directly from Fraser; they seem never to have considered reinstating material from the original that Fraser had cut. Among other drawbacks, this led to ever greater confusion in the matter of voice. Fraser had said of Gowers’s friendly use of I that it ‘would clearly be wrong to flatten the tone of his book by depersonalising his views’. Fraser therefore simply threw in his own I and lofty we as well, roughly indicating in his preface which parts of the second edition were his alone. But Greenbaum and Whitcut found this too much, and in the third edition did systematically depersonalise the writing. Gowers’s ‘I like to think’ becomes their ‘it would be pleasing to think’, and so on. Elsewhere, they substituted their own we.

It is true that there were two of them, but this change had unhappy results. First, they effectively appropriated Gowers’s role as author—to show their approval, they explained, of what he had said. Second, with their we spread far and wide, they introduced a coercive, patronising tone into the third edition. Gowers himself had sometimes used we, but when he did he almost always meant ‘you the reader and I the person writing this sentence’ (e.g. when he says of certain types of adverbs, ‘we have all seen them used on innumerable occasions’). Greenbaum and Whitcut, by contrast, regularly deployed we as here: ‘We are to prefer, in fact, conclude rather than “reach a conclusion” …’. The advice may be good, but Gowers would never have dreamed of expressing it this way. The tone of we are to prefer is what he called ‘chilly’ (and fought against: see p. 19). The words in fact, as used here, he would have struck out as padding (see pp. 112–18). We are to prefer X rather than Y is unidiomatic (see p. 69) and therefore needlessly risks distracting the reader (see p. 36): Gowers would have written of preferring word X to phrase Y. And rather than, being a longer way of saying to, is a waste of paper (see p. 24). In short, Greenbaum and Whitcut were so far immune to the advice of the book they were editing that they managed to violate four of its precepts in half a sentence.

Their other main change to the book’s written style may have been a better idea, but it was one they also failed to implement convincingly. Though they kept in the advice that said (in their own wording) ‘you may sometimes find it least clumsy to follow the traditional use of he, him and his to include both sexes’, they set about removing this use from the text. No doubt they recognised it as fusty. Yet their campaign was erratic. On some pages they substituted indigestible spates of he or she; on others, they left he to stand, as though the effort of changing it suddenly defeated them. And where they rewrote whole sentences to get round the problem, the results could be leaden. As an example, Gowers had opened with the remark that: ‘Writing is an instrument for conveying ideas from one mind to another; the writer’s job is to make his reader apprehend his meaning readily and precisely’. Under Greenbaum and Whitcut, this became ‘the writers’ job is to make the readers apprehend the meaning readily and precisely’.

The second and third editions obscured more than Gowers’s authorial voice. When Fraser revised the book in 1973, he also stripped out a great many of the examples Gowers had given of poorly handled English, not because the substitute examples were clearer or more helpful, but because Fraser hoped to do away with the original version’s ‘dated air’. The effect of this, naturally enough—with brand-new references to Edward Heath and the expanded EEC—was to give the work a 1970s air instead, which it kept through the third edition. It is inevitable that in the twenty-first century this improvement has become the literary equivalent of brown varnish.

THE RELEVANCE OF THE ORIGINAL BOOK TODAY

The first step towards restoring The Complete Plain Words has therefore been to do away with all the jam and engine grease. The fourth edition disregards the third and second, and instead directly revises the first. It also reverts to Gowers’s preferred title, Plain Words: he confessed late in life that he thought adding ‘The Complete’ had made it sound ‘ridiculous’. Most of his examples of bungled writing are now back in, in the hope that the 1940s world the reader once again glimpses will no longer seem drab and disheartening, but rather will add to the interest of the book. It is not now perhaps so tiresome to come upon references to withdrawn garments, coupons and requisitioning; to German prisoners marrying local girls; to the Trading with the Enemy Act, or the fear inspired by blister-gas bombs. Mention of the stop-me-and-buy-one man selling ice creams from the back of his tricycle may even have a certain charm. What is more, some of the concerns of the original book face us anew. We too have ‘our present economic difficulties’. We too wrestle with deficits and the problems of youth unemployment. A debate continues over whether mothers should be ‘constrained’ to go out to work. And sadly it still strikes home to read of a ‘growth of mistrust of intellectual activities that have no immediate utilitarian result’. Even strictures on wasting paper are once again a feature of the times, though in 1954 paper shortages were a continuing consequence of the war.

Many of the quotations chosen by Gowers to demonstrate poor handling of English were drawn from documents he had encountered in his work, and so we read in passing of National Insurance, tax instructions, coal, New Town legislation, and whether or not it is suitable to execute women by hanging. But though there are also numerous references to the Second World War, his own record is only glancingly touched on when, in an observation about the Blitz, he strikes a sudden personal note: ‘I used to think during the war when I heard that gas mains had been affected by a raid that it would have been more sensible to say that they had been broken’. Even here, the uninformed reader would have no way of knowing that the author of this stray comment had himself led the organisation responsible for ensuring that those ‘affected’ gas mains were mended again.

In the Penguin Dictionary of Troublesome Words (1984), Bill Bryson draws on The Complete Plain Words for an example of misused commas found in a wartime instruction booklet for airmen training in Canada. The booklet’s author had argued for learning to use clear English by warning that, ‘Pilots, whose minds are dull, do not usually live long’. Bryson caps this with the comment, ‘Removing the commas would convert a sweeping insult into sound advice’. Gowers’s own comment had been, ‘The commas convert a truism into an insult’. The shift from one to the other may seem negligible—Gowers’s deadpan ‘truism’ becomes Bryson’s more anodyne ‘sound advice’. But this strongly marks a difference of historical perspective: Gowers’s barb is that of a man for whom the survival of Allied pilots had very recently been a matter of the greatest importance in the fight to keep German bombers from reaching London.

Nor is Gowers’s sardonic reflection on the value of clear English at a time of catastrophic bombing raids on the capital quite as irrelevant today as one might wish. After terrorist outrages in the city in July 2005, the public transport system came to a halt, people were forced to walk for miles, and the city’s hospitals were overrun. While the Blitz spirit of its citizens was immediately vaunted in the press, the coroner subsequently charged with investigating the bombings found that there had been delays in caring for some of the victims because those working for the different emergency services had been unable to understand one another’s jargon. The coroner’s report contains what Gowers would doubtless also have considered a truism: ‘In a life-threatening situation everyone should be able to understand what everyone else is saying’. It is disturbing to discover that the official response to this comment was the promise that a ‘best practice’ ‘Emergency Responder Interoperability Lexicon’ with ‘additional user-relevant information’, though not ‘mandated’, would nevertheless be ‘cascaded’ through various training courses.

If that seems impenetrable, what of the English used by the broad range of today’s civil servants? Does their language also evince functional non-interoperability, and might they too, therefore, still benefit from a little advice in the spirit of Plain Words?

Apparently so. Representatives of the Local Government Association have grown so exasperated by official jargon that they have taken to publishing an annual list of what they optimistically call ‘banned’ words, ones the LGA would like to see eliminated from all documents put before the public. The list is enormous, and includes informatics, hereditament, beaconicity, centricity, clienting, disbenefits and braindump. As for the question of written style in the Civil Service, not long ago the Daily Mail raged against a government minister who had seen fit to waste time concocting an expensive report for ‘mandarins’ on how to write a straightforward letter. This report, according to the Mail, was filled with ‘excruciatingly pedantic’ warnings against, for instance, the use of meaningless adverbs, and of passive fillers such as it is essential to note that.

Gowers, in this book, agrees with both suggestions. They conform to what would become his most widely quoted maxim: ‘Be short, be simple, be human’. And whatever the Mail thinks, this maxim is still quoted today, even where Gowers himself is forgotten. Harrogate Borough Council, for example, prints it uncredited as a tag at the bottom of every page of its guide to using clear English, a booklet with the uncapitalised title put it plainly.

Merely printing the tag is not enough, of course. To carry out what it proposes requires thought. This is demonstrated by Harrogate Council’s own Corporate Management Team, who declare in what they call an ‘endorsement’ of the guide, ‘Better then to write as if we were speaking to the recipient of our communication’. Though shortish, this sentence is neither simple, with its inflated vocabulary, nor human, with its patronising ‘we’. Had the team absorbed Gowers’s maxim, which they print thirty-one times in their manual, they might instead have said, ‘When you write to someone, use a plain and friendly style’.

In March 1948, in a debate in Parliament on ‘Government English’, Mr Keeling, representing Twickenham, revealed that important official documents had been discovered to be incomprehensible to the general public. He argued that unless something was done about this, the business of various departments would fall into disrepute. He then welcomed the fact that Plain Words was about to be published, and hoped that it would help. Mr Pritt, Hammersmith North, could not resist a cutting response: ‘I have often wondered what the Tory party were interested in. They are not interested in getting anything done. But when we are talking about words their attendance is doubled—there are about seven of them’.

It may surprise the modern reader that Gowers soon found himself criticised for being too liberal in his advice: he discovered for himself, what he would later be told by one of the OUP ‘scrutineers’ who helped him to revise Fowler, that he would have to ‘mediate between the old hatters and the mad hatters’. The old hatters were disgruntled by his willingness in Plain Words to break what they considered ‘the rules’, even as the mad hatters interpreted his advice to write plainly as an example of ‘the snobbishness of the educated’. Meanwhile in odd corners of Whitehall much was made of the impropriety of encouraging junior civil servants to be plain with their superiors.

Though Gowers wrote about ‘rules’, he made it clear that he understood them as conventions. His view in sum was this: ‘Public opinion decides all these questions in the long run. There is little individuals can do about them. Our national vocabulary is a democratic institution, and what is generally accepted will ultimately be correct’. How long a given rule might stand was anybody’s guess. He therefore advised civil servants, who must write comprehensible English for unknown readers, that they should neither ‘perpetuate what is obsolescent’ nor ‘give currency to what is novel’, but should ‘follow what is generally regarded … as the best practice for the time being’.

BRINGING PLAIN WORDS UP TO DATE

That is all very well, but who can say what current ‘best practice’ is? Old hatters and mad hatters continue to broadcast their views. Some believe that Good English, bounded by antique superstitions, is their birthright, to be fought for with the ardour of the Light Brigade at Balaclava. Others dismiss so-called ‘good’ so-called ‘English’ as a risible manifestation of elitism. It is daunting to have to pick a path between these two camps, yet a fresh revision of Plain Words must do just that. Gowers once remarked that if a person were forced to choose, ‘it would be better to be ungrammatical and intelligible than grammatical and unintelligible’, only to add, ‘But we do not have to choose between the two’. Perhaps this new edition of his book is best thought of as being for those who instinctively agree, but who seek guidance on the prevailing conventions—so far as they can be discovered—of clear, formal prose.

When Gowers’s work first came out, he was praised by The Times for his ‘sweetly reasonable’ advice, and by the Daily Telegraph for a prose style that was ‘itself a model of how plain words should be used’. After sixty years, it has of course been necessary here and there to modernise both his advice and his writing, and I have attempted to do so, but lightly. There are instances in the original where Gowers’s style no longer stands. He starts sentences with the word nay, says the trouble about X, and that a railway clerk telephoned to him. He writes of a subject that has not a true antecedent, and of a person’s need to make sure he knows what are his rights of appeal. None of this sounds quite right any more, and so I have made small changes—what the managers of the London Underground call ‘upgrade works’. Habits of punctuation and spelling have also altered over the decades. Gowers’s to-day, jig-saw, mother-tongue and danger-signal become today, jigsaw, mother tongue and danger signal; acknowledgment and connexion become acknowledgement and connection, etc. His fondness for semicolons, which was striking when he wrote, is even more striking today. Though I am fond of them too, and have left many in place, I have removed about a hundred from the book. There are various misquotations in the original that I have attempted to correct, and I have also very slightly reordered the contents where this makes the line of argument clearer.

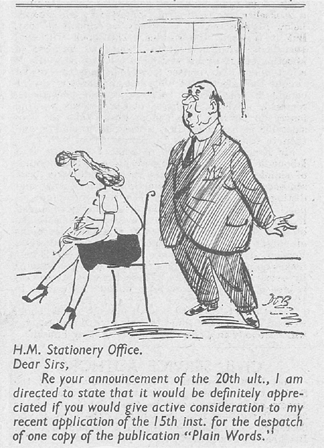

News Chronicle, 14 April 1948

Then there is the matter, mentioned earlier, of the use of he, him and his to stand for everyone. In the line referred to above, ‘make sure he knows what are his rights of appeal’, Gowers happened to be invoking the taxpayer; and in 1954 (though of course women also paid taxes) it was standard to use an indeterminate he to do so. There are those who still use this ‘makeshift expedient’, as it is called later in these pages, but there are others who would never think of it, and yet others who reject it on purpose. (Anyone who vaguely assumed of the London coroner mentioned earlier that she was a man, or who wrongly imagined likewise of the government minister excoriated by the Daily Mail that she was a man, must concede that supposedly neutral terms are not necessarily neutral in practice.) In 1965 Gowers admitted that he had spent ‘an awfully long time’ worrying over how to revise what he considered Fowler’s old-fashioned pronouncements in this area. Half a century on, opinions have moved further still. The indeterminate masculine pronoun, which Gowers eventually settled on calling a ‘risk’, is now so widely taken to be in breach of the very friendliness that he so keenly advocated, that I have removed all examples of the use from his writing.

Few revisers faced with decisions of this kind can be so lucky as to have a manifesto by the original author to draw on, but Gowers’s preface to his revisions of Fowler provided me with just such a guide. OUP had instructed him to keep as much of Fowler’s original work as possible, but asked him to remove any false predictions, and to make sure that no dead horses were being flogged. Gowers wrote in his preface: ‘I have been chary of making any substantial alterations except for the purpose of bringing him up to date’. And this has been my approach too.

The saddest instance of a false assumption made by Gowers is found in a defence he gave of the word ideology. He believed it to be a useful alternative to creed, ‘now that people no longer care enough about religion to fight, massacre and enslave one another to secure the forms of its observance’. A few remarks of this kind, and the odd digression that is no longer apropos, I have quietly edited out of the text. I have also removed examples of obsolete advice, such as that a casualty is properly an accident and not the accident’s victim. But though it was easy to class various small points of this kind as dead horses, where I could not feel sure, I chose to be cautious.

If I have left advice in the book that strikes readers as superfluous, I hope they will feel pleased that they did not need to be told rather than cross that they were. And if some of the current abuses that I mention go rapidly out of date, hurrah for that too. Many people who argue that ‘correctness’ is not of the utmost or even ‘upmost’ importance will still flinch at ‘organisationalised suboptimalism’, and agree that it is worth resisting new words of the type that Gowers called ‘repulsive etymologically’.

In this edition of Plain Words, I, other than in these few paragraphs of the Preface, is always Ernest Gowers’s authorial voice. Any interjection of mine, designed to bring a subject up to date, is clearly marked as a ‘Note’, or is a footnote, and finishes with a tilde glyph: ~.

Of course a person revising a usage guide lives in fear of being caught out and found wanting. In his private letters, Gowers wrote anxiously of captious, zestful critics waiting to pick out errors in his work.* I have had scrutineers of my own attempting to save me from this fate, to whom I am extremely grateful, but all flaws of revision in these pages remain my responsibility alone. I do not doubt that I will be thought of by today’s old hatters as a mad hatter, and by today’s mad hatters as an old hatter, and by both, probably, as a bad hatter: because I dared to tinker with a much loved work, because I bothered to do so, because I did not tinker with it enough. And there is no way to proof oneself against all these objections at once. But what I can say is that in revising a book known over decades for making people smile, my greatest wish was that it should continue to do so a little longer.

For the sheer hard work on this project by many of them, and the encouragement given to me by all, I would like to thank Ann Scott, Patrick and Caroline Gowers, Timothy Gowers and Julie Barrau, Katharine Gowers, Tanglewest Douglas, Raymond Douglas, Helen Small, Mark Kilfoyle, Derek Johns, Bryan Garner, Rebecca Lee and Marina Kemp.

Rebecca Gowers

October 2013