NOTES I

[1]

Notes towards a theory of musical reproduction.

(NB herein lies dissolution of the natural, ‘organic’ aspect of music, which is a mere social appearance)

True reproduction is the x-ray image of the work. Its task is to render visible all the relations, all aspects of context, contrast, and construction that lie hidden beneath the surface of the perceptible sound – and this through the articulation of precisely that perceptible manifestation. The concealment of such relationships, such as the works' own meaning may on occasion demand, is itself but a part of that articulation. This demand relates in particular also to the smallest of units – themes and motives. While the majority of performers effect an articulation of the large-scale form in basic terms, that of the partial units eludes them. For example: a structuring of themes in large-scale – not strophic – forms in terms of antecedent and consequent. Or: that a theme which reappears as a consequent to another has an entirely different meaning, and must therefore be interpreted differently than upon its first appearance. It is the precision and focus with which this micrological work is carried out (the simplest example of this is distinguishing between primary and secondary voices in chamber music) that the sense of the forms – their translation into content – depends on (example 2nd theme from C sharp minor Scherzo by Chopin, or the A flat major theme of the F minor Fantasy). And the problem of interpretation that always returns is the creation of a dialectic between part and whole, one which neither sacrifices the whole for the detail nor entirely annuls the detail through the whole. In the tradition of great Western music, the unity of the basic tempo achieves this. Wherever the unity of the movement is endangered by tempo modifications, even differential ones, articulation must be achieved by other means: phrasing, agogics, dynamics, timbre.

*

[2]

Different dimensions of music-making substitutable. With more highly organized music-making, there are countless occasions upon which a diminuendo, but sometimes also a crescendo, takes the place of a ritardando. Tempo modifications are always the most comfortable, the mechanical device – almost without exception at the cost of unfaithfulness to the text.

*

Against the cliché that one should be faithful to the spirit, not the letter. (NB Toscanini is unfaithful to the letter. Expand)1 NB Goeze and Lessing.2

*

Mimetic aspect of reproduction: the interpolation of details most readily comparable to that of the actor: interpreting means for one second playing the hero, the berserker, hope itself, and this is where the communication between the work and the performer lies.3 Only those who are able to imitate the work understand its sense, and only those who understand this sense are able to imitate. All languages apply the notion of playing to music.

*

Precise analysis as a self-evident precondition of interpretation. Its canon is the most advanced state of compositional-technical insight.

*

Development of the ideal of silent music-making, ultimately the reading of musical texts, in connection with falling silent (NB the utter destruction of the sensual phenomenon of music through mass reproduction). Playing from memory – ‘thinking the music to oneself’ – as a preliminary stage to this.

*

Begin with the question: what is a musical text. No set of performance instructions, no fixing of the imagined, but rather the notation of something objective, a notation that is necessarily fragmentary, incomplete, in need of interpretation to the point of ultimate convergence.

*

What is the relationship between musical notation and writing? One of the most central questions, inseparable from: what is the relationship between music and language?

*

[3]

Two fundamentally incorrect notions of the nature of musical interpretation need to be refuted: 1) that of the musical text as a set of performance instructions 2) that of the musical text as the fixing of the imagined. In a more profound sense, it is not the work that is the function of imagination, but rather vice versa (derive from the subject–object dialectic of the work. NB also the epistemological argument of the unknownness of the imagined – ‘thing-in-itself’. NB Schönberg's attitude to the text versus my own view. Yet it must be said that the ideal of the work incorporates the imagined and the performance instructions as extremes of the spectrum).

*

The concept of musical sense – as that which is to be represented – needs to be developed. Whereas the sense is not absorbed within the phenomenon, the possibility of its representation – as also of its self-representation – consists exclusively in the phenomena. But this means: within their context. Fulfilling the sense of music means nothing other than rendering all aspects of the context visible. This can be shown with reference to ‘senseless’ music-making, as the difference between what is living and what is dead. The dead elements are always those whose function in the musical context does not become evident. The concept of expression is itself to be understood in these terms (though not entirely: i.e. as an ideal; and in Beethoven's last works it is discarded.). This theory should be related both to the theory of music as a non-intentional text and the theory of x-ray images. Determining this relationship is the real concern of the study.

*

There will have to be an analysis of Toscanini's style of presentation. ‘Interpretation in the Age of Uninterpretability’.4

Motifs:

Separation of text (merely apparent faithfulness) and expression (context of effect).

‘Streamlining’: fetishism of smooth functioning without musical sense and construction. [Additional note in the left margin:] Functioning comes to replace function.

Relates to the compositions in the same manner that Zweig's biographies of writers relate to the writing.

[4]

Galvanization of the uninterpretable as ‘effect’: music becomes a form of consumption and an educational artefact at the same time.

Function of naïveté: infiltration of music by barbarism. Sibelius.5

The motifs of the conducting essay from Anbruch6 should be treated in this context.

*

The dignity of the musical text lies in its non-intentionality. It signifies the ideal of the sound, not its meaning. Compared to the visual phenomenon, which ‘is’, and the verbal text, which ‘signifies’, the musical text constitutes a third element. – To be derived as a memorial trace of the ephemeral sound, not as a fixing of its lasting meaning. – The ‘expression’ of music is not an intention, but rather mimic7-imitative. A ‘pathetic’ moment does not signify pathos etc., but rather comports itself pathetically. Mimetic root of all music. This root is captured by musical interpretation. Interpreting music is not referred to without reason as music-making – accomplishing imitative acts. Would interpretation then accordingly be the imitation of the text – its ‘image’? Perhaps this is the philosophical sense of the ‘x-ray image’ – to imitate all that is hidden. Actors and musicians.

*

Introduce the mere reading of music as a conceptual extreme. Perhaps – as a residue of unsublimated mimesis – the ‘making’ of music is already no less infantile than reading aloud (comes to the fore in choir). Silent reading as the legacy and conclusion of interpretation. It is this possibility – playing complex chamber music from memory, as inaugurated by Kolisch,8 and as asserting the absolute primacy of the text over its imitation – in comparison to which essentially all ‘music-making’ already sounds antiquated. – In the realm of composition, the works of Anton Webern are decidedly close to this idea. / Cf. Schumann9

*

[5]

Two statements made by Kolisch: ‘Even the virtuosic conducting arts of Bruno Walter were not able to incite the NBC orchestra to imprecision.’ – ‘The best thing about the cellist A.10 was his ugly tone.’ A critique of the ‘culinary’ element of musical interpretation should be carried out dialectically. It is not simply to be negated, but is only captured as something negated. The negation of the ‘beautiful tone’ is the true achievement of all musical mimesis – this is what ‘characteristic’ means.

*

The musical work undergoes similar change through being heard, renowned, exhausted, to the image under the scrutiny of the countless people who have pored over it. The work ‘in itself’ is an abstraction. The pure work-in-itself probably coincides with the uninterpretable. To be shown through the example of Schreker:11 today it is already light music.

*

The mimetic characters in the works are historical ciphers, and they escape from them. What Nägeli12 perceived in Mozart (analyse), and Hoffmann13 in Beethoven, is no longer within them. In Nägeli's day, Mozart was objectively ‘impure in style’, that is according to the state of the musical material. Today he no longer is. The historical change affecting the works as such always ensues in relation to the state of the material – one of the most important categories. This can also be expressed in the following terms: that every later commensurable work objectively alters every earlier one. Reproduction registers this alteration, and at the same time causes it. The relationship between it and the work is dialectical.

*

Not only do characters escape from the works; new ones also develop. The empire-classicist element in Beethoven that disappeared from Romanticism, which considered him one of its own, has today been translated into the very same constructive, economic, and integral properties that are central to true interpretation. This unfolding in time is true, more than of any other, of Bach.

*

[6]

Records of such famed and indeed authentic performers as Joachim,14 Sarasate,15 even Paderewski,16 have actually taken on the character of inadequacy. Joachim's quartet, which established the style of Beethoven interpretation, would today probably seem like a German provincial ensemble, and Liszt like the parody of a virtuoso. The dreadful streamline17 music-making of Toscanini, Wallenstein,18 Monteux,19 Horowitz,20 Heifetz21 – certainly the decline of interpretation – proves a necessary decline[,] to the extent that everything else already seems sloppy, obsolete, clumsy, indeed provincial (and at the same time it is not – both! Formulate with the greatest care)

*

Writing and instrument, the poles of interpretation.

*

Singing. The thought that no Steinway grand would ever conceive of giving a concert on account of having so beautiful a tone – whereas a singer would. The elimination of the sensual pleasure at sound is the idiosyncrasy in which the death of interpretation asserts itself. – Though the comparison between grand piano and singer is not entirely true – but has become true through vocal fetishism. The parting of the sensual and intellectual aspects of music.

*

In what respects is the musician a ‘player’, and in which not. There is not one musical interpretation that lacks the aspect of ‘missing the mark’ – without any risks. Interpretative freedom inseparable from risk.

*

Rubato, ‘stealing time’ – what does that actually mean? All problems of interpretation rightfully centred on this.

*

To the extent that music is ‘interpreted’, it is always ‘rubato’.

*

[7]

Supply a historico-philosophical interpretation of the dominance of interpretation over the matter itself. Appearance versus true nature; means versus end; person versus matter as the ideological reflex of reification.

*

The fetishization of interpretation is an attempt to break free from reification – appearance of immediacy – which leads only to a deeper entanglement in reification.

*

The objectivity of reproduction presupposes depth of subjective perception, otherwise it is merely the frozen imprint of the surface. This is one of the primary theses.

*

Ad Dorian22

Interpretation as a historical problem 23 The relationship between the performing and the creative artist, however, has changed profoundly in the history of music and continues to do so.

Zone of indeterminacy in notation (fermata23 and meaning) 27 Logically, the objective interpreter of the Fifth will perform the opening measures according to metronomic and other objective determinations, as indicated by the score and not by his personal feelings. If we turn from the particular case of the Fifth Symphony to any classical score, in fact to a score of any period, the inevitable question arises as to whether the score should be interpreted literally or whether the performer should have carte blanche in general interpretation, on the ground that, besides the script of the score, its background must also be freely taken into consideration. […] In spite of this, it would still be conceivable to insure what we call authenticity of interpretation, namely, the objective realization of the author's wishes, if the score as such were explicit enough to protect the composer's intentions against any misrepresentations on the performer's part.

Inadequacy of writing (28) Of course, great composers have superbly transformed their ideas into scores, making the best possible use of musical notation. But it is this very notation that is imperfect and may remain so forever, notwithstanding remarkable contributions to its improvement. There are certain intangibles that cannot be expressed by our method of writing music – vital musical elements incapable of being fixed by the marks and symbols of notation. Consequently, score scripts are incomplete in representing the composers' intentions. No score, as written in manuscript and published in print, can offer complete information for its interpreter.

Objectivity = interpretation of the meaning through the writing (and conversely: interaction, where writing is the ‘given’ that categorially attains sublation 28) The farther we go back in the different periods of history, the more difficult it becomes to read and know the score, to understand its graphic marks and symbols, and to supplement its meagre directions, if any – all of which is necessary for the faithful performance of the work. Instructions of a type considered indispensable today, such as those for the main tempo of a composition, were frequently omitted in early scores. This means that, from the very start, the interpreter has to supplement the material of the score with his own good judgement. Consequently, even the interpreter of truly objective spirit is bound to find himself occasionally on subjective terrain, irrespective of his loyal inclinations.

Lack of indication = not yet reified (here centred on division of labour 29) Sketchy as the old score may seem to the modern performer, it fulfilled its function by offering the necessary information in its own day, when the composer and the interpreter were so often one and the same person. Palestrina conducted his own masses, Handel his own oratorios, Mozart his own operas, and Bach himself sat on the organ bench of the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, playing his fugues and chorales. Even as late as the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was rather the exception when the composer was not his own interpreter. Chopin dreamed his nocturnes at the piano; and Paganini displayed his demoniacal virtuosity in the rendition of his music on a priceless violin.

Tendency towards unambiguity in modern notation 29 Today, the interpreter of contemporary works frequently has little or no personal choice, as he is forced to follow the very strict directions of the composer.

Stravinsky's ‘Sergeant’ 30. Stravinsky does not hesitate to compare a good conductor with a sergeant whose duty it is to see that every order is obeyed by his player-soldiers.

Connect my argument against background (style) to 30f. As things are, performers can roughly be divided into two groups. They are, according to their attitude toward the score, either objective or subjective executants. And any interpretation, at its very beginning, has to be one or the other. Suppose an interpreter – as many of the best of our day have already done – decides in favour of objective interpretation. If his task is the rendition of a new score of the elaborated type he may secure sufficient clues for his goal of work-fidelity. If he interprets an old work with few or no instructions, then a most difficult task confronts him. He must, because of the elasticity of the old score, reconstruct the work in terms of its musical background. As every score is an integral part of the age in which it is created, every detail of its performance depends upon knowledge of the manners and customs of a particular period.

Difficulty of the ‘composer's intention’ 31 Nothing is more difficult than his task of rethinking the old works, on the basis of the original elastic score script, in terms of the great masters who wrote them. There are three paths that will lead the interpreter out of this labyrinth. First, he must learn how to read the script and to understand its language. Second, his fantasy must discover the musical essence, the inner language behind the written symbols. Finally, the interpreter should be fully acquainted with the background and the tradition of a work – with all the customs surrounding the score at the time of its creation.

Rigid division into subjective and objective. But: an objective interpretation of the sense requires a subjective experience of the context. Against naïve musical realism. Objectivity (31 cf. Hegel Phenomenology)24

NB on the subjective side of interpretation, one must distinguish between intention and realization. Today, i.e. in the absence of a binding tradition, the latter takes priority. But realization has a dimension of its own: that of the relationship of the text to the instrument, or [to] the voice.

[8]

Relief (rationalization) through notation and increasing mindlessness of the performer 42. Things are made far more comfortable for the performer today. Unquestionably, there has been a downward trend as regards what the average musician must know. The general present-day level of his training is, in many respects, far lower than that set for his earlier colleague's ambition in his craft. (NB this is a total-historical tendency. Cf. fetish study)25

The ascetic element in the beginning of modern music and ‘interpretation’: ‘tone language’: 44 Caccini's interpretation attacked whatever seemed opposed to genuine emotional expression. Now, with the humanistic attitude of respect toward the word, the new interpretative goal was to express clearly the true effect of the ‘tone language’, as music was significantly called. This permitted a performance of the new monodic compositions on the basis of a broad subjective treatment of the text as the performer's guide. Emphasis was exclusively on the dramatic meaning of the poem and not on beautiful tone rows.

Voce finta, esclamazione 45f. Caccini recognized only two registers: voce plena e naturale (full and natural voice) and voce finta (artificial voice). In his interpretation he wished to restrict male singers to the use of natural voice, rejecting their falsetto as ugly; but sopranos and altos, boys as well as women, were permitted to use both registers. The use of the female falsetto was even considered enjoyable for esclamazione, a singing device of the Renaissance that retained its importance for centuries. Originally the term designated the reinforcing of the voice at the moment when it was about to diminish – a crescendo at the end of the tone. Metaphorically, not only the final crescendo but the whole figure is called esclamazione. Its importance may be judged from the fact that a representative British account of the new style, written as early as 1655, quotes from the Le nuove musiche as follows: […] ‘Because Exclamation is the principal means to move the Affections; and Exclamation properly is no other thing, but in slacking of the Voice to reinforce it somewhat.’

Music as language at the start of the modern age and the central problem of interpretation. 46 The fact that all these references appear at the beginning of Caccini's Le nuove musiche shows how much importance was attached to these devices as a principal means of expression. First and foremost, Caccini expressed his main idea of interpretation in the watchword, una certa nobile sprezzatura di canto – a ‘certain noble subordination of the song.’ The singer's task was to speak musically, as it were.

Subjectivism and identification 49 STILO RAPPRESENTATIVO. The difference between the old and the new style of madrigal is demonstrated by Sachs: ‘The sixteenth-century composer dealt with love through the medium of a madrigal in several parts. No one found any fault in the basses playing the role of a young girl or the sopranos that of a wooer. The music did not try to achieve illusion. In the seventeenth century the singer was merged with the imaginary character to whom the poet's verses were ascribed. The singer had to identify himself with him whose joys and sorrows were depicted in the words. […] After the polyphonic style of the past, les jeunes, around 1600, aspired to a stilo recitativo or rappresentativo, imitating natural diction and expressing even the most delicate and secret emotions of the soul.’

Freedom as an instruction already 1614 Frescobaldi. 54–55 Girolamo Frescobaldi, in the preface to his Toccate published in Rome in 1614, gives a most comprehensive description of organ interpretation. A digest of his rules follows. ‘1. First, this kind of performance must not be subject to strict time – as in modern madrigals, which are sung, now languid, now lively, in accordance with the affections of the music or the meaning of the words.’ We learn, thus, that Italian madrigals were sung with liberty of tempo […]. Obviously, the vocal style influenced the instrumental music. A singing bel canto performance on the instrument was the ideal.

On the prehistory of mass culture and its connection to problems of interpretation 55 ‘2. In the Toccate, I have attempted not only to offer a variety of divisions and expressive ornaments, but also to plan the various sections so that they can be played independently of one another. The performer can stop wherever he wishes, and thus does not have to play them all.’ This almost dangerous admission on the part of Frescobaldi would seem to open up new vistas for subjective interpretation. […] ‘5. The cadences, though written as rapid, must be performed quite sustained; as the performer approaches the end of the passage of cadence, he must retard the tempo gradually.’ […] We see that rubato and phrasing, in interpretation, were not invented with the employment of signs designating these features […].

Main source for the subjectification of interpretation as a function of reification 56f. From these rules emerge main principles of interpretation for the seventeenth century that also were to prove basic for centuries to follow: (a) subjectivity of reading, as good taste and fine judgement become rules of performance; (b) the special differentiation of types, such as the dances, according to their characteristics; (c) a general necessity of individual decision, changing almost with every passage; (d) the impossibility of generalizations applicable in more than the broad aspects indicated in rules 1 to 9.

Written music and printing 61 The most sweeping change occurred in the sixteenth century, when it became possible to print scores.

Renaissance, functional division, quantification, functional unity, jazz 62f. From the system then adopted to the complicated scores now in use, the way is long and the process is one of logical development. Today it is taken for granted that the orchestra is a group of performers of which each one plays an individually prescribed part. In fact, the young musician who joins an orchestral group can hardly conceive that it could ever have been otherwise. In the early days of the orchestra, however, the employment and grouping of instruments followed no definite order whatsoever. Apparently the only principle was not to have a principle. In those bygone days, whoever happened to be present at a performance played any available instrument. The method was one of extempore and improvisation. […] The conductor in the early days acted simultaneously as his own arranger. His responsibility was not limited to rehearsing and directing performances. First of all, he had to adjust the res facta, that is, the composer's written score and its tone rows, to the vocal and instrumental forces at hand. How such a metamorphosis of an original score into a variety of versions was brought about, is demonstrated in Syntagma musicum, a treatise published in 1619 at Wolfenbüttel, Germany, and containing invaluable information in many respects. […] We observe here the method called variatio per choros, variations designed for two contrasting choirs.

Emancipation of the violin from the voice 66 Monteverdi also fully realized the potentialities of the violin as the leading melodic instrument of the orchestra. Augmenting its compass from the third to the fifth position, he progressed from the point where the vocal mind of Gabrieli stopped. In other words, he liberated the violin from its function as a substitute for the soprano, and made it an independent orchestral instrument with individual expression.

absolutist style of presentation: stamping 69 Here, in front of his musicians and visible to all, stood Maître Jean Baptiste [Lully], pounding the beat with a heavy, decorated stick – a musical commander with military manners, insisting upon instrumental discipline and utmost rhythmical precision. […] Generations later, Jean Jacques Rousseau protested against the noisy beating of conductors in the theater. Rationalist that this philosopher-musician was, he finally became resigned to the idea that without the noise the measure of the music could not be distinctly felt by the singers and orchestra players.

Reification of composition (NB Beethoven's shorthand)26 70 The nineteenth-century opera composer Halévy pictured Lully sitting in his studio inventing only melodies and basso continuo, while two favorite apprentices, Lalousette and Colasse, took one sheet after another from the hand of their master to finish the orchestration – the first assembly-line system in musical history.

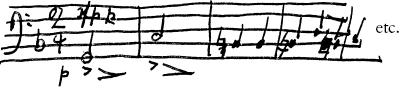

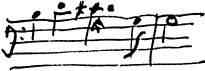

Convention governs divergence from notation + execution 72f. In the following illustration Muffat clarifies the considerable contrast that existed between notation and performance.

We see how rhythm is altered in the performance; script and execution are strikingly inconsistent. Such discrepancies cannot be comprehended from the modern point of view, with its striving for utmost clarity in notation. Yet alteration of rhythm was a common trend in the old practice of music. Therefore, the present-day interpreter, eager to perform these old masterpieces correctly, must reorientate himself in the intricate notation of this music. If the composer wrote those rhythmic patterns as he did – differently from the way they were to sound – he depended on the performer's knowledge of tradition.

No Bach tradition 76f. There is clearly a void of one hundred years in which Bach's scores were rarely played, and consequently no tradition of Bach performance could be handed down from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century.

Ad Bach: problem of the exploitation of later resources for earlier music 81 At the same time, to obtain a completely authentic picture of the problems in performing Bach, we must not overlook the facts, first, that today's performances take place in large concert halls and not in the St. Thomas Church, and that therefore the acoustics are different; second, that the master himself might have welcomed an opportunity of increased equipment. The question remains, however, how far he might have gone had he had the facilities of today's conductors. Could he, in his wildest dreams, have imagined the vast orchestral forces that perform today?

NB double stand against wilfulness and historicism (derive from the internal history of the works)

The ‘functional ornament’ (good idea of Dorian's, with many further consequences. The function of all that is accidental.27 The performance itself is accidental, after all, in a manner of speaking the ornamentation of the text that is entirely subsumed by the text, as it were. The reading of the ornament is the schema of all music's decoding. Ad 89) To put it paradoxically: ornaments are functional. In other words, they are neither mere embellishments nor musical tapestry.

[9]

On the key character of ornaments: ad figured bass. 91f. Bach's greatest son, with his Versuch [über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen], contributed to the musical world something of far more than academic and musicological importance. This volume, coming as it does directly from the workshop of the practical musician […] offers us in fact a veritable encyclopedia of the interpretative problems of its period. […] They contain a realization not only of the style and interpretation of the two great baroque masters, Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach, but also of all preceding and contemporary instrumental styles as expressed in English, French and Italian scores. Thus, the eclectic quality of the treatise becomes obvious and proves to be one of the great advantages of the Versuch. For all these historical and practical reasons, it is convenient to use this treatise as a ground plan for our presentation of ornaments. In the following pages, the different types of graces will be taken up in accordance with Philipp Emanuel's nine chapters on Manieren.

Standardization of dance 107 In dance music, likewise, ambiguity surrounds the meaning of different type names, and to a surprisingly intensified degree – surprising because, naturally, the dance music accompanied specific step patterns that were inevitably standardized, as in the case of minuet.

Pulse and tempo 115 Not only in the ever changing minuet, but in all the other fluctuating dance forms, the first and principal question to be settled is: What is the correct tempo? […] It was the methodical mind of Quantz that solved this problem half a century before the advent of Maelzel's invention. In his Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversière zu spielen, Quantz presents a method based on the human pulse. He assumed that there are eighty beats to the minute. This figure, in turn, is analogous to eighty time units on the metronome. Taking full advantage of Quantz's scheme, we easily translate his pulsations into the standard units of Maelzel's metronome. By mutual adjustment, any tempo can be stated precisely, eliminating ambiguity.

Account of the accelerando in the Rococo (116f., ad new tempi) A cross section of rather confusing courante designations can be gleaned from the following: ‘swift corantos’ (Shakespeare); ‘largo’ (Bassani); ‘rather quickly’ (Kuhnau); ‘pompously’ (Quantz). The reason for the variety of modes is the fact that the old dance has practically nothing in common with the later types called by the same name. As the Rococo lightened everything up, so the stately court courante gradually developed a moderate and eventually a fast tempo.

Affektenlehre, the mimetic element of interpretation and the context of their effect 139 Modern renditions of eighteenth-century music, aspiring to recall the spirit of that old time, cannot ignore substantially the ramifications of the Affektenlehre. Today it must be remembered that its laws controlled the old interpretation and that every eighteenth-century performer was expected to obey its rules. Reviewing first the general statements of various authorities, we learn that the musical expression of human emotions emerges as the final goal of interpretation.

Recognition and imitation of the affect 140 Unequivocally, Quantz demands that the performer recognize the affections expressed in a piece, always keeping his rendition in conformity with them. Thus, only interpretations based on an appropriate scrutiny of the affections, and their suitable musical application, are sanctioned.

Interpretation as imitation 144 As Lohlein in his Supervision in Violin Playing, Sulzer in his General Theory, and others have concluded, it is only when the performer fully experiences the composer's feeling that he is capable of arousing the corresponding emotion in those who listen to his performance.

crescendo: unity of composition and interpretation 149 However, beginning with Jommelli, the choice of modulation to piano or forte, crescendo or decrescendo, no longer resided in the will of the performer, but had to be sought in the instructions of the composer himself.

crescendo as a speciality (division of labour) 151 The difference between the earlier interpretations and those of Mannheim, as Rosamond Harding, G. Schünemann, and others show, is that an already recognized type of dynamic performance achieved a new tone-poetic effect and finally became a speciality, celebrated through the splendour of the Mannheim orchestral renditions.

End of figured bass and end of interpretative freedom 157 The comparison of the classical score with its predecessor reveals a further departure: the basso continuo has vanished from the script. In the orchestral and vocal scores of preclassical times, we see the figured bass part as an inevitable characteristic of concerted rendition. Thus, the keyboard part was executed ad libitum, interpreted in an improvisatory way. But improvisation, as the art of making music extemporaneously, ceases to be a factor in classical interpretation.

Dorian's undialectical view of subject and object [157] If interpretation as a subjective art could not become fully entrenched in music prior to the Renaissance and the awakening of individualized expression, then objective interpretation found its logical inception in the classical score. It is only since the latter part of the eighteenth century that sufficient clues had been made available, by the new classical script, to provide all the information necessary for a performance of work-fidelity.

Phrasing 159 (NB phrasing one of the core problems of ‘sense’). Phrasing is a feature common to both speech and music: it serves the same purpose in the language of words as in the language of tones. What may be called articulation in music is equivalent to diction in speech. Thus it is clear that phrasing occurs everywhere: in the tune of the torch singer and in the aria of Caruso; in the speech of the idiot and in that of Shakespeare. While phrasing is universal and ageless, in the sense that it has been exercised since Adam and Eve and the archbeginnings of musical utterance, the applied discipline of phrasing in the performance of music is young.

Sulzer's warning about the strong beats 162 (on the aging of modernity) In Sulzer's encyclopedia, General Theory of the Fine Arts, the following explanation is provided: ‘After the first note of each measure, the other strong beats should be less marked. The first note of a bar within a phrase must not be overaccentuated. Failure to heed this may spoil the whole performance. The caesuras are the commas of the song, which, as in speech, must be made manifest by a moment of relaxation.’

Connection between dynamics and phrasing: unity of elements (NB this unity is musical sense. This is one of the central theses). 162f. In 1834, Pierre Baillot (with Beethoven's friend Kreutzer, a leading exponent of the French violin school) states in L'art du violon: ‘Slight separations, such as rests of short duration, are not always indicated by the composer. The player must therefore provide them, when he sees that it is necessary, by letting the last note of the phrase die away. Indeed, in certain cases he must even let it end shortly before the completion of its normal duration.’

Good passage against false objectivity 163. Today there are many interpreters who, in a conscientious attempt to be objective, believe that the omission of bowings in the manuscript forces them to make the same omission in their playing.

Concept of musical sense and phrasing (central: 164) It suffices to quote Rousseau's Dictionnaire de musique (1775), which contributes the following on the topic ‘phrase’: ‘A singer who feels his phrases and their accent is a man of good taste. But one who renders only notes, keys, scales, and intervals, without comprehending the meaning of the phrases – even if he be precise otherwise – is nothing but a “note-gobbler” ’ (n'est qu'un Croque-sol).

Strength and dissonance (ad Wagner study.28 168) Further clues to dynamic distinction are provided by the harmony as such. Philipp Emanuel Bach points out that every tone foreign to the key can very well stand a forte, regardless of whether it occurs in dissonance or consonance. This is very convincing: the dissonance had been the enlivening element of all music since the era of medieval counterpoint.

‘Theme’ and dynamics: connection between form and dynamics 168 He [Quantz] also explains that the theme of the composition calls for dynamic emphasis.

Haydn and progress 177 However ‘Papa’ certainly has no place as a clue to Haydn interpretation today, in an attempt to produce an old fashioned gemütlich atmosphere of music-making, whereas in reality Haydn's scores represent the spirit of progress, depth, and artistic courage.

Dorian's rule of tempo (the musicological tempo) 180 The life-work of Mozart and Haydn falls into a time before the invention of the metronome, and so the difficult task of determining the right tempo in classical and earlier scores can be based only on the musical material in the script, in conjunction with musicological facts.

historical relativity of the text 181 (ad new tempi) In other words, notes that look long to the modern eye meant something quite different in their day: the brevis  , the semibrevis

, the semibrevis  , and the minim

, and the minim  are laden with connotations of slowness only in the minds of certain modern interpreters.

are laden with connotations of slowness only in the minds of certain modern interpreters.

Acceleration through repetition (ad historicity of tempo 185f.) Hence Quantz's precept: ‘When a composition (especially a fast one) is repeated (for instance, an allegro of a concerto or a symphony), it must be somewhat quicker the second time, in order not to put the listener to sleep. […]’ On the contrary, it is almost a criterion of acceptable classical performance that the tempo primo be resumed at every recapitulation.

NB the abstractness of the term espressivo must be retrieved. It relates not to the expression of something determinate, but rather to the speech-character of music.

Mozart's rubato 189 (criticize) [Dorian (p. 188) cites from a letter by Mozart of 24 October 1777:] ‘No one seems to understand the tempo rubato in an adagio, where the left hand does not know anything about it.’ First, it now becomes clear that Mozart himself played rubato – a discovery of great importance, since the majority of acclaimed performers strictly avoid the rubato as absurd in Mozart, which in turn is in keeping with the point of view of the dictionary on this very problem. Second, an insight is gained into the specific rubato technique of Mozart, according to his own description. The master himself discloses the secret – ‘the left hand does not know anything about it’. This, as will become apparent later, is the foundation of any rubato playing. Moreover, if one substitutes melody for the right hand and accompaniment for the left hand, it becomes a general prescription for performing music rubato.

Rubato as expression 190 The purpose of his [Pier Francesco Tosi's] technique of ‘robbed’ time was expression. Rubato was thus used where a particular phrase required special expressive emphasis.

[10]

NB The problem of interpretation lies in the dialectic of expression and construction

Beethoven's ambivalence towards the metronome 198 On the manuscript of his song Nord oder Süd, Beethoven wrote the notation, ‘100 according to Maelzel. But this must be applicable only to the first measures, for feeling also has its tempo and this cannot be entirely expressed in this figure’. NB Dual nature of reification. Protest of ‘life’. Cf. later Debussy-Bergson 300).

espressivo as ritardando 207 We can find nowhere in Beethoven a specifically prescribed rubato. As we shall see in a later section, the literal instruction, tempo rubato, was introduced by Chopin. Yet there are evidently passages where the aggregate of Beethoven's markings amounts to what the rubato instruction represents in later periods: a variation of time with gradual modification. For example, in the opening movement of Opus 111, the original instruction, allegro con brio ed appassionato, dissolves completely upon the very first appearance of the second theme. Here, meno allegro appears in the second half of the measure, followed by two measures marked ritardando.

Element of imagination and fidelity 220 In striking contrast to the attitude of wilfulness toward the score, there also prevails, during the nineteenth century, the contrasting thought of allegiance to the score.

The original manuscript 224 One of the most characteristic features in modern interpretation is the increasing tendency to turn to the original manuscripts of great composers as the dependable basis for proper rendition. Studying the composer's manuscript, rather than the printed edition, is the ideal way of approaching a master's score. Schumann's critique 224f. Nevertheless, while Schumann stresses the objective approach by insisting upon reference to the manuscript, he at the same time warns the interpreter against blind acceptance of every detail of the manuscript and against an exaggeration of the conception of objectivity.

Character through musical content 227 central (NB find passage in Schumann) In the composer's own view, then, the Schumann interpreter must, first of all, grasp the character of his scores from the musical content – from the very structure of the score. […] If we trace Schumann's ideology further, we see how he stamps himself as an aesthete of the Affektenlehre, with the following viewpoint on tempo: ‘You know how I dislike quarrelling about tempo, and how for me only the inner measure of the movement is conclusive. Thus, an allegro of one who is cold by nature always sounds lazier than a slow tempo by one of sanguine temperament. With the orchestra, however, the proportions are decisive. Stronger and denser masses are capable of bringing out the detail as well as the whole with more emphasis and importance; whereas, with smaller and finer units, one must compensate for the lack of resonance by pushing forward in the tempo.’

Wagner's supple tempi (ad vitalism)

functional rubato 239 Another observer of Chopin's time variation is Ignaz Moscheles, who explains Chopin's rubato as a specified means of gliding over harsh modulations in a fairy-like way with delicate fingers. Thus, rubato was applied in a purely functional way, so unlike the abuse of it by many modern executants with whom it degenerates from slight variation into a disregard of time – a vulgarized licence of meter and confusion of rhythm smuggled into the Chopin performance in the guise of so-called tradition.

‘objective’ interpretation precisely of subjectivist music 246f. In spite of the obvious emphasis on the composer's subjective experience, there is, in his expressed views, an insistence on objectivity in interpretation. It is strictly demanded that the interpreter regard himself as nothing more than the loyal medium of the composer.

Tempo as a central problem 280 Taking literally Beethoven's word ‘tempo is the body of performance’, Wagner demonstrates how the technique of correct interpretation centers around the setting of the right tempo […].

extreme adagio + allegro. ‘Tempo variation’ in Wagner 281f. The true adagio can hardly be played too slowly; the naïve allegro is usually a quick alla breve. […] After considering the problem of tempo primo, Wagner approaches that of tempo modification, bitterly complaining that the technique of time variation was utterly unknown to performers. But to his mind this very factor was the vital principle of all music-making.

Meistersinger prelude 282 For the modern interpreter, the composer's own illustration of the proper rendering of his Meistersinger prelude, in a flexible four-four time, is most important. Here modifications serve the purpose of exposing discriminately the diverse themes as interwoven in the polyphonic web.

Wagner in favour of tempo modifications 283 Wagner demands tempo changes in the course of the opening movement; yet this was generally treated by conductors as a single unit.

The subjective element of objective interpretation (against Dorian 284) Summing up, we realize that Wagner's interpretative ideology is that of his age. All the traits of Romanticism are embodied in this one great mind: extreme subjectivity seeks the strange company of a passionate striving for extreme loyalty.

Dorian's undialectical view 285f. The fact is, Verdi went even farther in emphasizing radical objectivity of rendition than did Wagner. Not torn like the latter between antagonistic ideologies (of work-fidelity on the one hand, and the claim to the interpreter's right to re-create on the other), Verdi was most tyrannical in demanding unconditional obedience to his scores.

Against the opposition ‘theatrical/historical’ 293 Bülow believed, however, in a third power also, namely, in himself. And so he sails in completely subjective waters, recklessly changing eternal words, such as Bach's Chromatic Fantasy, and showing, in his editing of Scarlatti or Beethoven, his own theatrical showmanship rather than a true historical approach.

Virtuoso and circus (control over nature) 299 The attraction of the virtuoso for the public is very much like that of the circus for the crowd. There is always hope that something dangerous may happen. M. Ysaye may play the violin with conductor Colonne on his shoulders, or M. Pugno may conclude his piece by lifting the piano with his teeth. [Claude Debussy, La Revue blanche, 1 May 1901]

Debussy's anti-mechanism 300 In La revue blanche [of 15 May 1913], we read his [Debussy's] comment: ‘At a time like ours, in which mechanical skill has attained unsuspected perfection, the most famous works may be heard as easily as one may drink a glass of beer, and it only costs ten centimes, like the automatic weighing machines. Should we not fear this domestication of sound, this magic that anyone can bring from a disk at his will? Will it not bring to waste the mysterious force of an art which one might have thought indestructible?’

Satie, Dada, jazz 304f. If one reads the list of instruments intended to be used for background noises in the performance of Satie's ballet Parade – sirens, typewriters, airplanes, dynamos – it becomes clear that our machine age has fully entered the realm of performance.

historical correctness: severing of the dialectical relationship 311 The principle of historical correctness, one of the most significant trends in modern interpretation, had its beginning long before the dawn of the twentieth century: we have only to recall the work-fidelity of the romantic era to realize that the objective approach is not an achievement of our age. […] Supported by great scores, important ideologies, undreamed-of technical accomplishments, the trend to correctness in musical rendition is now an established principle.

| NB | Objectivity is not historical correctness. Today, this latter is mostly decorative, candle light – subjective in the bad sense, i.e. in contradiction of the terms of the objective spirit. |

No pre-stabilized harmony between composition and the historically available means of interpretation (against historicism 312) With such a general turning to the past world of music, emphasis on a legitimate old style of performance is but the logical consequence. If baroque scores are to be played with historical correctness, then the historical instruments actually used in readings by their composers, and not our modern ones, must be employed.

Schönberg's Bach29 312f. Not only the need for the return to the old sound ideal, but simultaneously the absurdity of certain modern arrangements is indicated: it is historically incorrect to substitute the modern orchestra palette for the old one […].

Discuss problem 318 Probably the best-known example [of Beethoven's use of the horn] is found in the opening movement of the Fifth Symphony. In the fifty-ninth measure, the theme is given to the horns; the analogous passage of the recapitulation, however, is given only to the bassoons. Why Beethoven resorted in the second version to bassoons is obvious: since he could not use the stepped notes of the E flat horn for the expressive power of this phrase in C major, the only alternative available was to substitute bassoons for horns. With the advanced technique of the instrument today, conductors do what Beethoven could not have done in 1805, and use the horn in both cases, relieving the bassoons from a task for which they are not well suited.

Stravinsky's positivism30 329 For the schooling of the young interpreter, Stravinsky's suggestion is noteworthy that it would be wiser to start the education of the young musician by first giving him a knowledge of what is, and only then tracing backward, step by step, to what has been.

Schönberg's ideal of insight 333 The romantic method necessarily consists of a heightening of the surface luster, rather than what Schönberg demands – balance and symmetry of presentation, where true insight into the construction governs the outline as well as all the details of the interpretation.

[11]

Elimination of the interpreter as ‘middleman’ (342) We have only to think of the possibility of an apparatus that will permit the composer to transmit his music directly into a recording medium without the help of the middleman interpreter.

Standardization of performance through the gramophone record 342f. One of the direct consequences of recordings is the means they provide for improving the average interpretative standards. With the renditions of the great musicians available on disks, the mediocre performer has a priceless opportunity to orientate himself by model performances. […] But there is another side of the picture: such a second-hand interpretation, accomplished through imitation, is bound to lack the conviction of a personalized conception. The student, before the convenient availability of the gramophone, was forced to acquire his knowledge of a masterwork by direct study of the score, playing it on the piano, or just reading it. This approach sharpened his ear and imagination.

On the end of musical interpretation 343–44

- the works' process of becoming uninterpretable31

- the ‘writing’ of the sound

- the standardization of interpretation

- no interaction between performer + listener Such interaction of artist and audience does not exist in the case of the electric rendition. Neither is the interpreter before the microphone stimulated by an audience, nor can the listener to a record or a broadcast performance be influenced beyond the aural sensation.

*

On Richard Wagner's ‘Über das Dirigieren’ [On Conducting] (G.S. 8, p. 261ff)32

| 264: | As even the great theatre managers, according to the laudable taste of their courts, have the very highest opinion of these favourite operas, it is not surprising that the demands of works entirely unpopular among these gentlemen could only be fulfilled if the conductor happened to be an important man with a serious reputation, and if he himself knew very well what is required of an orchestra today. |

| Emphasis on the authority of the conductor. (NB with the growth in the sense of reproduction, its repressive character also grows: ad philosophy of modern music. In other words: the fetishization of reproduction, the senseless Toscanini ideal, is in fact produced by the radical pursuit of musical sense itself. The ‘monopolization’ of music arises from within its own confines). | |

| 268f.: | I received my best instruction regarding the tempo and delivery of Beethoven's music from the soulful, securely accentuated singing of the great Miss Schröder-Devrient; since that time, for example, I have found it impossible to let the oboe reel off its cadenza in the first movement of the C minor Symphony [bar 268] in as helpless a manner as I have never heard elsewhere; indeed, I then also felt, retracing my steps from the delivery of this cadenza now that I had understood it, what meaning and expression should already be lent to the first violins' [g] [bar 21] that is sustained as a fermata at the corresponding point, and through the profoundly moving impression that I acquired of these two so apparently unassuming moments, I gained an entirely new insight that breathed life into the whole movement. |

| retrospective interpretation (starting from the oboe cadenza in the 5th). I.e. totality as looking forwards and backwards. The meaningful interpretation transcends the mere present. The mark of poor interpretation is its fulfilment in the representation of whatever is present: the positivistic withering of memory. Definition of effect as mere present. Cf. Wagner's ‘cause without effect’33 (NB Wagner contradicts this p. 285 [None of our conductors dare to afford the adagio this quality to the proper degree; from the very start they are on the lookout for some figuration within it so that they can then set the tempo according to the supposed movement of the same.]) | |

| 269: | From a very early age, the orchestral performances of our classical instrumental music left me with a marked feeling of dissatisfaction, and this feeling has returned whenever I have attended such performances in recent times. Things that seemed infused with such soulful expression at the piano, or while reading the score, were barely recognizable to me as they rushed past listeners, for the most part quite unnoticed. |

| ‘infused with soulful expression’: musical sense first of all defined by expression for Wagner. | |

| 271: | The orchestra had just learned to recognize the Beethovenian melody in every bar that had entirely escaped our well-behaved Leipzig musicians at that time; and this melody was sung by the orchestra. |

| the requirement to ‘recognize the melody’. Regarding this: 1) interpretation as insight. 2) melody here essentially means the ‘running thread’, i.e. context. (Proof 286 [The most significant of Beethoven's allegros are largely dominated by a basic melody that belongs, in a deeper sense, to the character of the adagio, and this lends them the sentimental meaning that sets them so clearly apart from the earlier, naïve form of the same.]) | |

| 273: | How were those Parisian musicians able to reach the solution to this difficult task so infallibly? First of all, obviously, only through the most conscientious diligence, as is native to those musicians who are not content to pay each other compliments, who do not imagine that they can understand everything by themselves, but rather feel timid and concerned in the face of something not yet understood, and attempt to grasp what is difficult from the side upon which they are at home, namely the side of technique. |

| on the interaction involved in true interpretation: ‘Grasp what is difficult from the side of technique.’ Through a conversion of representational problems into technical ones, the subjective element of interpretation asserts itself by necessity. (Reification – subjectivity). But therein at the same time the positivistic element so characteristic of the progressive Wagner (separation of meaning and technique; therefore Gesamtkunstwerk etc.) | |

| 274: | But only a correct grasp of the melos also dictates the correct tempo: the two are inseparable; one conditions the other. […] If one wishes to provide a summary of all that is required of a conductor for the correct performance of a musical work, it lies in his always supplying the correct tempo; for the choice and determination of the same allow us to recognize immediately whether the conductor has understood the musical work or not. The correct tempo almost guides good musicians, once they have become closely acquainted with the musical work, towards the correct delivery, for the former is already based on a recognition of the latter on the part of the conductor. But the difficulty of determining the correct tempo becomes clear from the fact that the correct tempo can only be found through a recognition of the correct delivery. |

| [12] | |

| tempo as a function of the ‘melos’ (context) and a criterion for understanding. The mutually contradictory statements made by Wagner (show contradiction) at the bottom of the page are the most precise expression of a dialectical state of affairs, which the anti-Hegelian Wagner would have been the last to admit. | |

| 275: | In this, the musicians of old had such a good instinct that, like Haydn and Mozart, they were normally very general in their tempo indications: placing ‘Andante’ between ‘Allegro’ and ‘Adagio’, with its most simple of increases by degrees, covered almost everything they considered necessary. With S. Bach, we finally encounter an almost complete absence of tempo indications, which for true musical sense is the most correct of all. For this sense might well ask itself: if someone does not understand my theme, my figuration, its character and expression, what good can one of these Italian tempo indications still do for him? – To speak from my own very personal experience, I shall mention that the early operas I had performed at various theatres contained quite elaborate tempo indications, which I proceeded to fix infallibly (or so I thought) through the metronome. Now, whenever I heard a ridiculous tempo in a performance, for example of my ‘Tannhäuser’, the persons in question defended themselves against my recriminations by assuring me that they had followed my metronome indication with the utmost scrupulousness. From this, I saw how unreliable a means mathematics is in music, and henceforth not only left the metronome off, but also restricted my instructions for the main tempi to very general indications, being meticulous only about the modifications of these tempi, as our conductors know next to nothing about these. |

| the romantic thesis of the primacy of sense over notation. Wagner's centrepiece, the theory of ‘tempo modification’, is directly contingent upon this. | |

| 282: | Herein lies that most crucial aspect, which we must seek to understand very clearly if we are to move beyond a rendition of our classical works of music that is so often neglected and spoilt through bad habits towards a fruitful communication. For bad habit apparently has the right to insist upon its assumptions regarding the tempo, on account of a certain agreement that has developed between it and the common delivery, which on the one hand conceals the true vice from the parties it affects, but on the other hand tolerates a clear deterioration owing to the fact that the accustomed mode of delivery, when subjected only to one-sided changes in the tempo, normally becomes quite unbearable. |

| Wagner's concession of the relative – historical – validity of incorrect interpretation (as second nature. Has very far-reaching consequences). | |

| To clarify this through the most simple of examples, I shall choose the opening of the C minor Symphony [by Beethoven]: our conductors pass over the fermata in the second bar after lingering there briefly, and linger thus almost entirely for the purpose of directing the musicians' concentration towards a precise rendition of the figure in the third bar. The note E flat is not normally sustained any longer than the duration of a forte on stringed instruments when played with a careless bow. Now let us assume that Beethoven's voice called out to a conductor from the grave: ‘Will you hold my fermata long and grimly! I did not write fermatas for my own entertainment or for lack of ideas, to pause for thought about what should come later; but rather to cast into the intense and rapidly figured Allegro, as I might require it, what in my Adagio the tone, which should be wholly and fully absorbed, means for the expression of sensual revelry, as something blissful or a dreadfully sustained convulsion.’ | |

| [In the left-hand margin, crossing the subsequent note:] NB Rheingold prelude. | |

| The magnificent passage on tone. (NB the absolute tone is pure expression that is transformed into the expressionless. It denotes the opposite of sense, i.e. absolute construction, which is transformed into expression), namely: | |

| 283: | ‘And now pay attention to the specific thematic intention I had with this sustained E flat after three turbulent short notes, and what I want to say with all the equally sustained notes in what follows.’ |

| the expressive sense as ‘thematic intention’ (!) | |

| But this evenly sustained tone is the basis for all dynamics, in the orchestra as in singing: only by taking it as a point of departure can one reach all those modifications whose diversity determines the character of the delivery in the first place. | |

| the even tone. | |

| Without this basis [the evenly sustained tone] an orchestra may make much noise, but without any force; and herein lies a first characteristic of the weakness of most of our orchestral performances. | |

| Wagner against ‘weakness’ (within limits: ideal of monumentality) | |

| 285: | Here, then, the Adagio stands opposite the Allegro, like the sustained tone of figural motion. The sustained tone dictates the rules of the tempo adagio; here, rhythm melts away into the life of the tone, which belongs to itself and is content with itself. |

| the famous passage on adagio and the pure tone. | |

| 286: | B. Walter's theory34 of the adagio character of cantabile themes. Even in the Allegro, examining precisely its defining motives, it is always the song borrowed from the Adagio that dominates. |

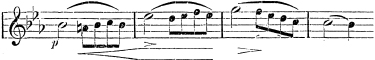

| Misunderstanding of the Eroica theme (expand). [Adorno noted in the margin of Wagner's essay, next to the music example showing the first subject of the first movement of the Eroica: this is not an ‘adagio melody’ – not a ‘melody’ at all.] | |

| 287: | Here [in the finale of Mozart's E flat major Symphony and that of Beethoven's A flat major Symphony], the purely rhythmic movement celebrates its orgies, to a certain degree, and therefore these allegro movements cannot be taken determinedly or fast enough. Whatever lies between these extremes, however, is subject to the law of mutual relations, and these laws cannot be grasped delicately or variedly enough. For they are, at a profound level, the same ones that modified the sustained tone itself in every conceivable nuance […]. |

| the ‘law of mutual relations’. | |

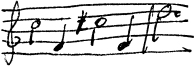

| (288: | The most perfect of this kind [‘Mozart's fast alla breve movements’] are the Allegros of his opera overtures, especially those from ‘Figaro’ and ‘Don Juan’. One knows about these that they could never be played fast enough for Mozart's taste […]. Extremes. Mozart's  ) ) |

| 290: | Initially, I was concerned only to solve the dilemma myself, and to make it clear to all people that, since Beethoven, there has been a very substantial change in the treatment and delivery of music in comparison to former times. Things that used to be held apart in single forms complete in themselves, each living their own life, are here kept together and developed with reference to one another, at least in terms of their innermost main motives, in the most contrasting of forms, and enclosed by these very forms. Naturally this must also be taken into account in the manner of delivery, and the most important way to ensure this is for the tempo to be no less delicate than the thematic fabric itself, which should convey itself through the tempo according to its movement. |

| Main evidence in Wagner for the historical character of interpretation (‘since Beethoven, there has been a very substantial change in the treatment and delivery of music in comparison to former times’) | |

| 292–93: | The real weakness of variation form as the basis of a movement, however, becomes apparent when starkly contrasting parts are juxtaposed without any connection or mediation. […] The most unpleasant effect of this careless juxtaposition can be experienced when, after the quietly measured theme, an inexplicably gay first variation immediately enters. The first variation of the uniquely wonderful theme in the second movement of the great A major Sonata for piano and violin by Beethoven [op. 47] has always driven me to the point of outrage at any further music-listening, as I have never heard a virtuoso treat it any differently than is merited by a ‘first variation’ serving the purpose of gymnastic production. […] So it would therefore seem natural for the performer, who, in such a case as the Kreutzer Sonata, demands the honour of representing the musician entirely, to attempt to establish a gentle connection between the entry of this first variation and the mood of the theme that has just ended, by showing a certain consideration with regard to the tempo through an initially mild indication of the new character in which – according to the unalterable opinion of pianists and violinists – this variation enters: if this were to be carried out with the proper artistic sense, then the first part of this variation, for example, would itself create the gradual transition to the newer, more lively attitude, thus also gaining – quite aside from all that is otherwise interesting in this part – this particular charm of a pleasantly ingratiating, but in fact not insignificant, change of the basic character established in the theme. |

| Wagner's mania for transition. He is incapable of understanding contrast as a means of creating context. It is precisely this common sense of mediation as something gradual that leads to a distortion of interpretation (C sharp minor Quartet [op. 131 by Beethoven]). NB everything ‘over-defined’ in Wagner, the musical drama embodies totality as tautology.35 | |

| 294: | This Allegro [the second movement – marked Allegro molto vivace – of op. 131, which is separated from the first only by a fermata] thus directly follows an adagio of a dreamlike melancholy perhaps unlike any other by the master […]. The question here is now clearly how this [the theme of the second movement] is to approach the frozen melancholy of the immediately preceding Adagio ending, as it were to emerge from within it, so that it does not injure our sentiment more than engaging it through the abruptness of its entry. – Entirely appropriately, this new theme is also initially presented in an unbroken pp, precisely in the manner of a delicate, barely recognizable vision, and soon melts away into a fading ritardando; only then is it animated, so to speak, to reveal its true self, and through the crescendo enters the sphere unique to it. – Here it is clearly a delicate task for the performer, appropriate to the sufficiently clear character of this Allegro, also to modify its first entrance through the tempo […]. – [Adorno notes along the edge of the musical example:] NB as the connection has already been established by motivic means, it would be pleonastic also to keep the tempo constant [?]. It would be distasteful. |

| criticize the example of the C sharp minor Quartet. | |

| 298: | Once I had thus given the introductory Adagio [of the Freischütz overture] back its grimly mysterious dignity, I allowed the wild motion of the Allegro free rein in its passion, being in no way restricted by consideration for the gentler delivery of the delicate second subject, as I was entirely sure that I would be able to curb the tempo sufficiently once more for it imperceptibly to reach the correct level for this theme. |

| Furtwängler as Wagner's heir. | |

| 299: | In order no longer to interrupt my account of that performance of the Freischütz overture with the Vienna Orchestra, I shall now continue by relating how, after the utmost heightening of the tempo, I used the drawn-out song of the clarinet, entirely derived from the Adagio: |

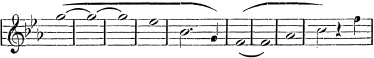

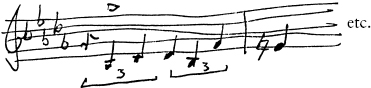

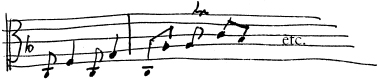

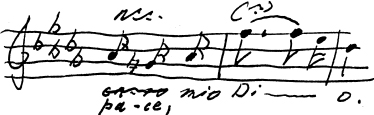

| |

| to restrain the tempo imperceptibly from here on, where all figural movement dissolves into sustained (or trembling) notes, sufficiently for it to arrive, despite the more active intermediate figure: | |

| |

| in E flat major, with the cantilena thus beautifully prepared, in the mildest nuance of the still constant main tempo. | |

| the element of reason in Wagner's modifications. | |

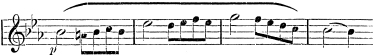

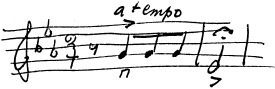

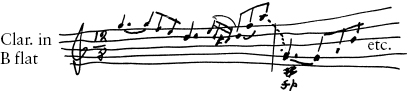

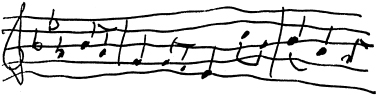

| 299ff.: | [This passage follows on directly from the one cited in the preceding note:] If I now insisted that this theme |

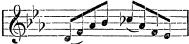

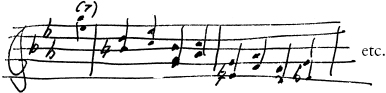

| |

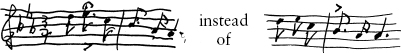

| should be rendered at an even piano, that is to say without the usual accentuation of the ascending figure, and also with even phrasing, so not | |

| |

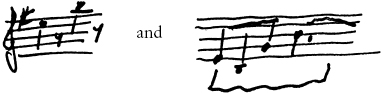

| then this admittedly had to be discussed with the otherwise so excellent musicians first. But the effect of this delivery was then so conspicuous that, when the tempo subsequently increases imperceptibly with the pulsating | |

| |

| I needed only to make the quietest suggestion of this motion to find the entire orchestra equally showing the most insightful enthusiasm for the return of that most energetic nuance of the main tempo and the subsequent fortissimo. | |

| [13] | |

| the superb analysis of the interpretation of the Freischütz overture (esp. 299 below). Here, however, the modification is justified by the constructive defects of the composition. I.e. the space of interpretative freedom is always the fragility of context in the work. One of my main theses. Interpretation is the work's retrieval. | |

| 308f.: | As I have touched upon a number of times above, attempts to modify the tempo for the delivery of classical, that is to say Beethovenian, musical works have always met the resistance of the conducting faction in our times. I showed in greater detail how a one-sided modification of the tempo, without a corresponding modification of the delivery in terms of the tone itself, would appear to give cause for objection; on the other hand, I also revealed here the error upon which this is more fundamentally based, thus leaving no other possible explanation for these objections than the incompetence and lack of vocation of our conductors in general. A genuinely valid reason for criticizing the approach that I find so indispensable in the cases mentioned, however, would be that nothing could be more harmful to those musical works than nuances – also in the tempo – incorporated wilfully into their delivery, of the kind that give free rein to the fantastic whims of every vain tempo-beater aiming for effect or enamoured of himself, and would in time disfigure our classical music repertoire completely beyond recognition. Of course, all that can be said in response to this is that our music must indeed be in a sorry situation for such fears to arise, as this at the same time reveals that people no longer believe in the power of true artistic consciousness, which would immediately defeat such acts of wilfulness, in our collective artistic states. |

| Discussion of the objections to Wagner's subjectivism (NB connect Wagner's theory to the nominalism of his entire oeuvre) | |

| 310: | [One] must now realize what state the manner of these works' delivery, in which they are eagerly conserved according to the laws of that incompetence and dreariness, must be in if one considers without reservation, on the other hand, in what way even a master such as Mendelssohn dealt with the direction of these works! […] And I shall therefore subject this sanctimonious rejection of that spirit which I have termed the correct one for the performance of our great music to closer examination, in order to show in all its poverty the peculiarly recalcitrant spirit which that defensiveness feeds off, and above all to remove the aura of sanctity which it presumes to place around itself as the chaste German artistic spirit. For it is this spirit that inhibits any free progress in our musical life, that keeps every breath of fresh air at a distance from its atmosphere, and which could in time truly blur our glorious German music into a colourless, indeed ridiculous ghost. |

| against historicism: Wagner's insight that it is precisely conservation that is destructive. | |

| 312ff: | In our world, the musician always remained merely a strange being, half wild, half childish, and was employed as such by his patrons. |

| Wagner's sociological theory of the musician. | |

| The ‘new’, ‘elegant’ performer as an agent of circulation (anti-Semitic theory), as a parasite upon the work. ‘Educatedness’ Just as the Jews, for example, have remained strangers to our trade life, our newer musical conductors have not come from the class of musical craftsmen, which was repugnant to them already on account of the strict proper work it entails. This new conductor instead placed himself immediately at the top of the musicians' guilds, just as the banker does with our trade partnerships. To do so, he had to bring something from the start, something which the musician coming from the bottom precisely lacked, or which he could gain only with the greatest difficulty, and rarely to a sufficient degree: just as the banker brings capital with him, this new type of musician brought educatedness. (consider very closely) | |

| 314: | In general, it is a primary characteristic of this educatedness that it does not dwell intensely on anything, does not immerse itself profoundly in anything, or also, as one says, does not make a meal of anything. […] It therefore avoids all that is monstrous, divine or demonic, simply because it cannot find anything in it to imitate, which is why it is common for this educatedness to speak, for example, of excesses, exaggerations etc., which has in turn given rise to a new aesthetic that professes to be influenced by Goethe, claiming that he was also averse to all things monstrous, and therefore invented such a beautiful, calm clarity. Here, then, we find the ‘harmlessness’ of art being praised, while Schiller – who was too intense upon occasions – is treated with a certain degree of contempt, and thus, in prudent accordance with the philistine of our times, a whole new idea of classicism is being developed, one which in other artistic fields the Greeks are finally also drawn into, on account of their being so well attuned to clear, transparent gaiety. |

| Educatedness as conformism, ‘harmlessness’. | |

| 315: | Here it only remains for me to explain the merry Greek quality of this ‘passing over things’ so urgently recommended by Mendelssohn. […] Mendelssohn's aim was: to hide the inevitable weaknesses in the performance, perhaps also in what is being performed; with those [his followers and successors], however, this is joined by that quite particular motive for their educatedness, namely: to conceal things in general, to cause no fuss. |

| Conformist performance as ‘concealment’ (opposite of x-ray photography) NB: ideological character of positivism in particular. | |

| 316: | A large part of their education has always consisted in taking as great a care over their comportment as one who is burdened with the natural impediment of a stammer or a lisp, and who must avoid any arousal in his announcement, lest he descend into the most improper stuttering or bubbling. […] The German is stiff and awkward when he seeks to appear well mannered: but he is sublime and superior to all others when he catches fire. Are we supposed now to restrain this for the sake of those people? |

| Wagner's insight into the classicist style of presentation as repressed mimesis. | |

| 317: | First of all, and most importantly for our investigation, the success of this negative maxim showed itself precisely in the delivery of our classical music. This was now determined solely by the fear of descending into the drastic. |

| ‘fear of descending into the drastic’ (superb) | |

| It was only the great Franz Liszt who fulfilled my desire to hear Bach. Certainly, Bach in particular was also cultivated there; for here, where there was no modern effect or Beethovenian intensity, that joyfully smooth, entirely insipid manner of delivery could seemingly be conveyed particularly well. I once requested a performance of the eighth prelude and fugue from the first part of The Well-Tempered Clavier (E flat minor) from one of the most renowned older musicians and comrades of Mendelssohn […], because this piece had always exercised a particularly magical attraction upon me; I must confess, I had seldom experienced such a shock as I received upon the cordial fulfilment of this request of mine. For there was then certainly no trace of a sinister German Gothic style or any such humbug; on the contrary: under my friend's hands, the piece flowed over the piano with a ‘Greek gaiety’ to such a degree that I was quite speechless at so much harmlessness, and involuntarily saw myself transported into a neo-Hellenic synagogue, from whose musical cult all Old Testament emphasis had been eradicated in the most well-mannered fashion. | |

| the ‘neo-Hellenic synagogue’. | |

| 319: | This aversion [the maxim: ‘under no circumstances any effects’], which, after all, originally merely concealed their own impotence, has now become an indictment of potency, and this indictment draws active force from suspicion and slander. The breeding-ground upon which all this prospers is the poor spirit of German philistinism, of a sense that is caught at the pettiest level of being, and which we have seen also to encompass our musical life. |

| objectivism as resentment (Nietzsche-like theory. Triebschen?) cf. Newman IV, 33736 | |

| 321: | Some time ago, a South German newspaper editor accused me of ‘pietistic’ tendencies in my theories on art: the man clearly had no idea what he was saying; he was simply looking for a scathing word. For according to my experience of the nature of pietists, the peculiar nature of this abhorrent sect lies in its striving after what is delightful and seductive in the most insistent fashion, only to repel true delight and seduction after meeting with their ultimate resistance. |

| ‘pietist’ (Wagner himself!) | |