Social Heritage

“San Francisco knows how”

—PRESIDENT WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT

OF ALL the arts San Franciscans have practiced, the one they have most nearly perfected is the art of living, but hedonism is only one of the elements of which San Francisco's civilized social tradition is compounded. Omar Khayyam's “Take the Cash and let the Credit go” has been as freely accepted for a motto, perhaps, as his “jug of wine” and “loaf of bread”—and more freely than the spiritual precepts of the city's official patron, the gentle St. Francis.

Yet all through this materialism runs a fugitive thread of humanitarian tenderness; a reverence for culture, often uncritical; a fundamental urbanity. Every viewpoint has had its say in the city's long succession of journals and newspapers. Enriched also by this democratic quality is the whole history of the city's devotion to the theater, to musical performances and art exhibits, to restaurants and cabarets and bars. Where so much of living has vitalized a popular culture, the social heritage is bound to have a special richness.

HIGH LIFE AND LOW LIFE

A “sort of world's show of humanity”—such was that San Francisco which so impressed the visiting Britisher, J. D. Borthwick, in 1851, with its “immense amount of vitality compressed into a small compass.” Around the same table in the gambling saloons he found “well-dressed, respectable-looking men, and, alongside of them, rough miners fresh from the diggings, with well-filled buckskin purses, dirty old flannel shirts, and shapeless hats; jolly tars half-seas over… Mexicans wrapped up in their blankets smoking cigaritas… Frenchmen in their blouses smoking black pipes; and little urchins, or little scamps rather, ten or twelve years of age, smoking cigars as big as themselves…” Along the streets, old miners were to be seen loafing about “in all the glory of mining costume… Troops of newly arrived Frenchmen marched along…their persons hung around with tin cups, frying-pans, coffee-pots, and other culinary utensils… Crowds of Chinamen were also to be seen, bound for the diggings, under gigantic basket-hats…”

After the first rush to the mines, most of this mob of immigrants returned to San Francisco to stay. Careless of the professions to which they had been trained, doctors and dentists became draymen, barbers, or shoeblacks. Lawyers and brokers turned waiters or auctioneers or butchers; merchants became laborers and laborers, merchants. Any and all of them kept lodginghouses and gambling saloons, speculated in real estate and merchandise—always ready to embark on some new enterprise.

Not without reason did the Argonauts boast that no coward ever started for California and no weakling ever got there. The Gold Rush was composed almost entirely of young men, many in their ‘teens, with a lust for adventure as strong as their lust for fortune. In this adventurers’ paradise, ladies of joy reveled in a degree of latitude rarely heard of in American history. While cribs and brothels catered to the unfastidious, more sumptuous parlors enticed the discriminating. When “the Countess,” San Francisco's leading courtesan of 1849, opened her establishment, she sent cards of invitation to the town's leading citizens, not excluding the clergy. Full dress was the rule at this fasionable rendezvous, and six ounces of gold dust, or $96, was the price of an evening's entertainment.

Any talents used to entertain the public were handsomely appreciated. Dr. D. G. Robinson, part-owner of the Dramatic Museum, was elected alderman in 1851 to reward him for the pleasure he had given by renditions of his “Random Rhymes.” No one thought it strange in 1849 when the Commissioner of Deeds, Stephen C. Massett, resigned from his job to compose songs and to give recitations and imitations. A strolling piper with “cymbal, triangle, accordion and bass-drum” gathered a “harvest,” and “Dancing Billy” earned enough to buy drinks all around each time he stopped, and was able to pay his musician $50 an hour. The musicians “blew and scraped, thrummed and drummed, jingled and banged throughout the live-long day and night.”

In every saloon were tables for monte and other card games, or for rondo and roulette and chuck-a-luck. Gambling facilities were the main source of revenue in all hotels. Merchants had to bid against their operators for places to do business; the resorts spilled over onto the wharves. Most of the gold which miners brought to town made its final disappearance over the tables, for the men had a superstition that it was bad luck not to be flat broke when they started back to the mines.

In 1853, the editors of the Christian Advocate made a survey of the town and “found, by actual count, the whole number of places where liquor is sold in this city to be five hundred and thirty-seven.” Of these, 125 places did not even “keep an onion to modify the traffic.” Forty-eight were “dance-houses and such like, where Chinese, Mexicans, Chilean, and other foreign women are assembled.” Contemporary writers describe the saloons as “glittering like fairy palaces.” The outlying taverns were spoken of with no less warmth: “A jolly place to lounge in easy, ricketty, old China cane chairs and on bulgy old sofas” was MacClaren's, on the lane to the Mission. Little inns with similar charm were strung along all the rural roads.

On Sunday, the Spanish village at the Mission was aglitter with the silver trappings of hitched horses, whose owners, having ridden out from the commercial settlement, were spending the day in the Spanish taverns. The Russ Gardens, along the Mission Road, were taken over on holidays and Sundays by national groups who “leaped, balanced and twirled, danced, sang, smoked and made merry.”

Though the 1850’s saw no abatement in gambling, drinking, and carousing, the more discriminating element of the population was gradually withdrawing from the more popular saloons and restaurants. New hotels and cafes were being established to meet their demands. The Parker House with its elegant appointments, its apple toddy, and its painting of Eugenia and Her Maids of Honor, vied for popularity with the Pisco Punch and the Samson and Delilah of the Bank Exchange. Around these, the Tehama, and the St. Francis gathered those who were groping toward refinement and that privacy which their lack of homes denied them. Private gambling dens were set up and a process of social selection began.

Steve Whipple's gambling house on Commercial Street was transformed, in 1850, into the first gentlemen's club, its clientele girded in swallowtails and flashing diamond cuff links. Such devices for “drawing the line” were not without painful consequences to that spirit of camaraderie which the average forty-niner had naively come to expect of his fellow men. An anecdote of this period tells of a miner, wearing the rough clothes of the “diggings,” who wandered inside and was politely informed by a waiter that he had strayed into a private club.

“A private club, eh?” retorted the miner. “Well, this used to be Steve Whipple's place and I see the same old crowd around!”

Nevertheless, San Francisco's leading citizens were determined to create some kind of orderly and civilized social pattern; and this tremendous task was finally solved by elevating the saloon, the cafe, and the theatre to places of social distinction. Even before 1851 there had been attempts to stage decorous balls and parties where “fancy dress” was required, but even the most successful of these affairs could not attract more than 25 ladies. A record was set in June, 1851, by the attendance of 30 fair maidens at the first of a series of soirées given at the St. Francis; and when 60 ladies showed up at the July soirée, the newspapers commended the St. Francis for the “social service” it had rendered.

But this hotel (which also first introduced bed sheets to the city) was to be the scene of an even greater triumph. This was a grand ball organized by the Monumental Six, the city's first company of volunteer firemen, at which no less than 500 ladies were present. It was said that California was ransacked for this array of femininity, and that some of them were brought by pony express from as far east as St. Joseph, Missouri. The press declared that at last “the elements were resolving themselves into social order.”

Since the brilliance of this affair was not immediately repeated, the process of social cohesion threatened to give way once more to the roughshod individualism of the forty-niners. Even the respectable women of San Francisco complained of the high cost of party dresses and avoided going out into the muddy and rat-infested streets. The men started attending the theater, but it offered little attraction. The rainy season set in and brought monotony to the city which, until then, had never known a dull moment.

In this social emergency, some enterprising individuals hit upon the idea of presenting a series of “promenade concerts.” “A large crowd was present on the first evening, but…there were no ladies present to join in the ball at the close of the concert; and such a scene as was presented when the dancing commenced beggars description.… The music commenced; it was a polka; but no one liked to venture. At last two individuals, evidently determined to start the thing, ladies or no ladies, grappled each other in the usual way…and commenced stumping it through the crowd and around the hall… As dance after dance was announced more and more joined in, until…the whole floor [was] covered with cotillions composed entirely of men, with hats on, balancing to each other, chassezing, everyone heartily enjoying the exhilarating dance…” Whether or not the affair was a “failure,” as McCabe's Journal called it, the promenade concerts were abandoned.

What civic-minded San Franciscans could never quite accomplish in the battle for social cohesion was brought about by natural and dire necessity. As a result of the conflagrations that had almost destroyed the city on six successive occasions, there had sprung up a number of companies of volunteer firemen, to which it was generally considered an honor to belong. A parade of San Francisco's firemen was the occasion for the whole State to go on a Roman holiday. Preceded by blaring bands and the gleaming engines decked with flags, the parades stretched a mile in length. Each fireman marched proudly to the martial music, attired magnificently in his red shirt and white muffler, his shiny black helmet, and his trousers upheld by a broad black belt. Each firehouse, on parade days, was thrown open to the public. The city's leading breweries gave kegs of beer, and other firms donated crackers, cheese, and sandwiches.

The engine houses themselves were furnished as lavishly as the hotels and restaurants of the later fifties. Howard Engine, to which Sam Brannan gave allegiance, was one of the most splendid of them all and was especially noted for the brilliance of its social functions. The Monumental Six and the High Toned Twelve might boast more elegant houses, but the “Social Three,” as Howard Engine was popularly known, had the only glee club and the first piano. Long afterwards, San Franciscans recalled with pride that magnificent dinner the “Social Three” once gave for the visiting firemen from Sacramento. The menu on that occasion, still preserved in the M. H. de Young Museum, was “of cream satin, a foot and a half long and a foot wide, highly embossed, and elaborately decorated in red, pink, and blue, the work of the finest ornamental printers in the city.”

So rapidly did the city grow that by 1856 all its aspects of intolerable crudity had disappeared. Plank sidewalks brought a measure of safety to pedestrians, and substantial new buildings were going up in every street. The custom of promenading took hold on everyone; and Montgomery Street became for the next 30 years an avenue filled with the endless pageantry that was old San Francisco.

It was a gay and motley crowd that paraded there every day of the week in the 1850’s and 1860’s—a crowd utterly democratic and unconventional. From the fashionable quarter at California and Stockton streets came the wives and daughters of San Francisco's wealthy set. “Tall, finely proportioned women with bold, flashing eyes and dazzling white skin” came from the half-world of Pike Street (now Waverly Place). Lola Montez was known to pass along this street, her bold admirers kept at a distance by the riding-whip she carried. Men were still in the majority; bankers, judges, lawyers, merchants, stock brokers, gamblers—all wearing silk hats, Prince Albert coats, ruffled shirts, fancy waistcoats, and trousers fitted below the knee to display the highly polished boot.

Mingling with this passing show were strange public characters whom everyone accepted as part of the parade. “George Washington” Coombs, who imagined himself to be the father of his country, paraded the streets in coat, waistcoat, and breeches of black velvet, low shoes with heavy black buckles, black silk stockings, and a cocked hat. The tall disdainful figure of “The Great Unknown,” clad in the height of fashion and impenetrable mystery, was the cynosure for all eyes, but never was he known to stop or talk to anyone in the years he followed this solitary course. The street beggars, “Old Misery” (also known as the “Gutter Snipe”) and “Old Rosey” each morning appeared, gathering odds and ends from refuse cans—”Old Rosey” always wearing a flower, usually a rose, in his dirty coat lapel. There were also the two remarkable mongrels, “Bummer” and “Lazarus,” whose relationship transcended ordinary animal affection; together they trotted the same course as the paraders.

Also allowed a certain patronage was Oofty Goofty, the “Wild Man of Borneo” in a sideshow, who walked the sidewalks of the Barbary Coast, in a garb of fur and feathers, and emitted weird animal cries. Later he launched into new fields, allowing anyone to kick him for 10¢, hit him with a cane or billiard cue for 25¢, with a baseball bat for 50¢. When the great pugilist John L. Sullivan tried his luck with the bat, Oofty Goofty was sent to the hospital with a fractured spine. After his recuperation, he engaged in freak shows as the companion and lover of “Big Bertha.”

The era was a heyday of street preachers: evenings and Sunday mornings would find “Old Orthodox” and “Hallelujah Cox” delivering orations to accumulating multitudes. Stalking them would be “Old Crisis,” a vitriolic freethinker of the times, who would mount the rostrum when they had vacated. The itinerant patent-medicine distributors also did a thriving business. Of these, the “King of Pain,” attired in scarlet underwear, a heavy velour robe, and a stovepipe hat decorated with ostrich feathers, rode in a black coach drawn by six white horses. Found daily on the sidewalks around the financial district was a greasy figure, old and lonely, displaying a large banner reading, “Money King, You Can Borrow Money Cheap”; he charged his borrowers exorbitant rates of interest.

Last, but by no means least, came the Emperor Norton attired in his blue Army uniform with its brass buttons and gold braid and his plumed beaver hat. Everybody knew and liked this mildly insane little Englishman, who, after heavy financial reverses had wrecked his mind, styled himself “Norton I, Emperor of North America and Protector of Mexico.” For two decades, traveling from one part of the city to another, he saw to it that policemen were on duty, that sidewalks were unobstructed, that various city ordinances were enforced. He visited and inspected all buildings in process of construction. The newspapers solemnly published the proclamations of this kindly old man, and his correspondence with European statesman. When in need of funds, he issued 50¢ bonds, supplied by an obliging printer, which were honored by banks, restaurants, and stores. His funeral, in 1880, was one of the most impressive of the times, with more than 30,000 attending the ceremony in the old Masonic Cemetery. When, only a few years ago, his remains were removed to Woodlawn Cemetery, down the Peninsula, an infantry detachment fired a military salute, and “taps” were blown over his grave.

The “golden sixties” saw the flowering of a Western culture, wherein the uncouth, violent San Francisco of Gold Rush days evolved to the tune of Strauss waltzes and polite salutations from carriage windows; and the grand social events of the Civil War period brought to the Oriental Hotel, the Lick House, and the St. Francis a social pageantry, splendid and refined. The tobacco-spitting, gun-toting forty-niner was being taken in hand by such arbiters of propriety as Mrs. Hall McAllister and Mrs. John Parrott. Nouveau riche citizens of Northern sympathies were succumbing to the gracious mode of living taught by the Secessionists. The aristocratic Southern set, which insisted on a certain formality, could, however, always forgive those who violated its discipline with charm and wit and good taste. Gradually the fashionable parade of carriages outshone the promenade of Montgomery Street; and the exodus toward Market Street began, which was to erase the most distinguished feature of San Francisco as the city of the Argonauts. But it was in the large ball rooms of private homes that the magnificence of San Francisco's social life was shown to best advantage. Here, seemingly oblivious of the civil strife, San Franciscans gave full rein to their natural gaiety.

The completion of the transcontinental railroad put an end to the splendid isolation in which San Franciscans had reveled for two decades. Soon the fantastic wooden castles of the Big Four were to rise on the summit of Nob Hill, to announce to an astonished citizenry that San Francisco was at last an American city. “California has annexed the United States” was the prevailing opinion, but it was only the final and defiant expression of the pioneer spirit that refused to admit its heyday was over. With money running plentifully, society in the seventies and eighties was tempted to relax, to catch what lavish silver-toned enjoyment emerged from its pompous realm.

Marking the first official get-together of writers, artists, and dilettantes, the Bohemian Club was founded in 1872, with quarters on Pine Street above the California Market. Under the guidance of art-loving Raphael Weill, the club opened its portals to Sarah Bernhardt and Coquelin the Elder and, later, entertained with elegant breakfasts, luncheons, and dinners in the Red Room of its building at Post and Taylor streets. Other notables sampling the Bohemian Club's correct and charming hospitality, which was acknowledged to speak for all San Francisco, were Nellie Melba, Ellen Terry, Rudyard Kipling, Henry Irving, Helena Modjeska, and Ignace Paderewski.

During this era and the “Gay Nineties” San Francisco was to achieve its reputation as “The Wickedest City in the World.” The potbellied little champagne salesman, Ned Greenway, led society through the artful steps of the cotillion. Sprightly Lillie Hitchcock, as honorary member of the San Francisco Fire Department, aroused disapproving thrills among smart matrons by wearing the resplendent badge presented her by the Knickerbocker 5. Returning from entertainment furnished in the rose-tinged Poodle Dog at Bush and Dupont Streets or from Delmonico's, famous for its soundproof rooms and discreet waiters, railroad builders and Comstock financiers chatted of rare vintages and made inward plans for “private” suppers.

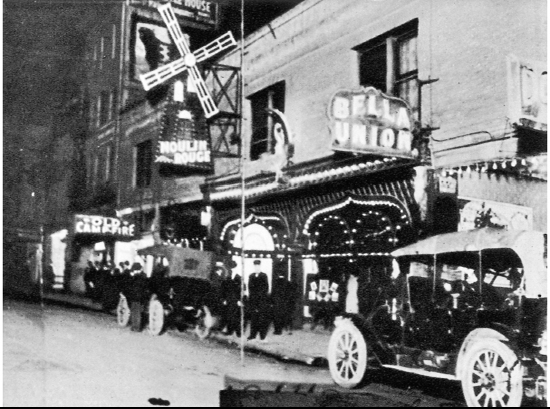

Along the Barbary Coast, the underworld whirled in fantastic steps to the rhythmic tunes of banging pianos, banjos, tom-toms, and blaring brass horns. It was the era of checkered suits, derby hats, and bright turtleneck sweaters. The police patrolled the district in pairs. Assisted by honky-tonk pianos grinding out “Franky and Johnny,” gamblers fleeced their victims with inscrutable calm. From Barbary Coast dives to the Hotel St. Francis came the banjo, with Herman Heller as orchestra leader, soon to be followed by Art Hickman's introduction of the saxophone, which would bring jazz to the modern era.

It was into this phantasmagoric atmosphere that Arnold Genthe brought Anna Pavlowa on a slumming tour. At the Olympia, a glittering dance hall, she watched the rhythmic sway of the dancers. Fascinated, soon she and her partner were on the floor. No one noticed them, no one knew who they were. Feeling the barbaric swing of the music, they soon were lost in the oblivion of the time-beats of the orchestra. One couple after another noticed them and stepped off the floor to watch. Soon they were the only dancers left on the floor, the other dancers forming a circle around the room, astonished, spellbound. The music stopped, Pavlowa and her partner were finished, there was a moment of silence. Then came a thunderous burst of applause, a stamping of feet, a hurling of caps. The air was filled with yells of “More!” Pavlowa was in tears.

San Francisco “remembered” the sinking of the battleship Maine with characteristic gusto in 1898. While transports clogged the Bay, the boys in blue camped in the Presidio hills and daily marched down Market Street to the troopships to the tunes of “There'll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” and “Coon, Coon, Coon, Ah Wish Mah Color Would Fade.” The Spanish War to San Franciscans was almost one continuous fiesta. Too late for the war, the battleship Oregon steamed into the Bay to celebrate the victory. Public subscription erected a monument to Admiral Dewey in Union Square.

Soon the “ridiculous” horseless carriage was snorting along the roads in Golden Gate Park; later it ventured timorously downtown to frighten the bearded or bustled citizens, who viewed the “newfangled contraption” only to maintain that horse and cable cars “were fast enough.”

Near the corner of Powell and Market streets, in 1914, stood some of the most famous of the cabarets and taverns in the West. On Powell Street were the Odeon, the Portola Louvre, and the Techau Tavern. Around the corner was the Indoor Yacht Club. On Mason Street flourished the Black Cat, the Pousse Café, and Marquard's, and within walking distance were famous bars, such as the Waldorf and the Orpheum, and innumerable foreign restaurants. While the graft investigation scandals of 1906 had forced the toning down of the city's night life, it was not until the war years and the advent of Prohibition that the death knell of San Francisco's gaiety was sounded.

Most of the cabarets closed, never again to reopen. San Franciscans disdained grape juice and patronized the bootlegger; they escaped, however, the curse of the gangster, who in most cities crept in with temperance. The Odeon became a cafeteria, as did the Portola Louvre. The Techau Tavern became a candy store; Marquard's became a coffee shop. Over old San Francisco, twilight had fallen, from which it never would emerge. San Francisco would be the same city when the era of sobriety came at last to its end, but, like wine in a bottle once opened, then corked and laid away, its flavor would be gone.

BEFORE THE FOOTLIGHTS

Through the ingenuous emotions of a child of the eighties, a famous San Franciscan has tried to lay a finger on the special and intrinsic values that have caused San Francisco to be considered a great theater city: “Actors in those days liked to go out to the Coast, and as it was expensive to get back and not expensive to stay there they stayed… Uncle Tom's Cabin…was very nearly my first play… Then I enormously remember Booth playing Hamlet but there again the only thing I noticed…is his lying at the Queen's feet during the play…although I knew there was a play going on there, that is the little play. It was in this way that I first felt two things going on at one time.”

The theater-goer here probing back into her childhood was a longtime resident of San Francisco—Gertrude Stein—later associated with the stage herself as the author of Four Saints in Five Acts. And the conclusion she draws may be extended to all the theater-goers and actors of San Francisco, who have never lost the feeling of two things going on at one time: that active co-operation of audience and actor.

The Americans who came with their banjos ringing to the tune of “O Susanna!” were not content for long with wandering minstrelsy. By the middle of 1849, they had lined their pockets with gold, were dressed up, and wanted some place to go. In an abandoned school-house, from which the teacher and trustees had departed for the mines, on June 22, 1849, Stephen C. Massett, “a stout red-faced little Englishman,” adventurer and entertainer who also called himself “Jeems Pipes of Pipesville,” gave a one-man performance of songs and impersonations, for which the miners were happy to pay him more than $500. Following Massett came the first professional company—”h”-dropping Australians—who presented on January 16, 1850, Sheridan Knowles’ touching drama, The Wife. The excellence of this performance may be judged from the leading lady's speech, quoted from another play, The Bandit Chief: “ ‘is ‘eart is as ‘ard as a stone—and I'd rayther take a basilisk and wrap ‘is cold fangs around me, than surrender meself to the cold himbraces of a ‘eartless villain!” The theater was filled with curious, excitable miners, who paid as high as $5 for admission. Yet the miners soon learned to order such hams out of town at the pistol point.

The circus had already come to town, even preceding the Australians. Wandering by way of Callao and Lima, the enterprising Joseph A. Rowe brought his troop to a lot on Kearny Street, opening October 29, 1849. Here materialized a curious phenomenon, the alternation of circus performances with the tragedies of Shakespeare. Rowe on February 4, 1850, put on Othello—the first of a long series of Shakespearean performances.

The early 1850’s were noted for a series of off-stage tragedies that periodically snuifed out the stage performances. Six disastrous fires brought theater buildings down with the rest of the city. In the period from 1850 to 1860, there were three Jenny Linds, two Americans, two Metropolitans, two Adelphis, to say nothing of structures not rebuilt—the Dramatic Museum, the National, the Theatre of Arts, the Lyceum, and countless others. But with pioneer courage the city rebuilt.

And struggling through these fires to make theater history in San Francisco were Tom Maguire and Dr. David G. “Yankee” Robinson—utterly unlike except for their power as impresarios. With Dr. Robinson came the first crude stagecraft and the first real satires on the local scene. On July 4, 1850, he opened his Dramatic Museum on California Street, with a localized adaptation of Seeing the Elephant, a popular circus deception. He started the first dramatic school in San Francisco. An actor himself and a kind of playsmith, he was the life-blood of his theater. One of his plays, The Reformed Drunkard, has had many revivals under the title Ten Nights in a Barroom.

Beginning as an illiterate cab driver, gambler, and saloon keeper, Tom Maguire came to be one of the country's great impresarios. This man, like the city itself, was fiery, good-natured, both acquisitive and generous; ignorant, uncouth, eager for novelty and yet animated by a childlike passion to be a patron of “culture.” Sleight-of-hand artists, opera singers, sensational melodramas, jugglers, minstrels, Shakespeare, leg-shows: all these succeeded each other swiftly at Maguire's Opera House during its eighteen years of existence. The only man comparable to him in his time was P. T. Barnum.

The roaring fifties saw a cavalcade of exits and entrances on the San Francisco stage: James Stark, that ambitious young tragedian; Mrs. Sarah Kirby Stark, his wife, and a noted actress-manager; the prolific and talented Chapman family, headed by William, Caroline and George; the perennial Mrs. Judah as Juliet's nurse; and the unsurpassed family of Booth, magniloquent Junius Brutus and the adolescent Edwin. The “Sensation Era” of the 1860’s brought Lola Montez, Adah Isaacs Menken, and Lotta Crabtree, those glamor girls of the Gold Coast. And late in the 1860’s came Emily Melville, of musical comedy fame, whose subdued style of the French school usurped the place of the “sensation” manner.

San Francisco's By-gone Days

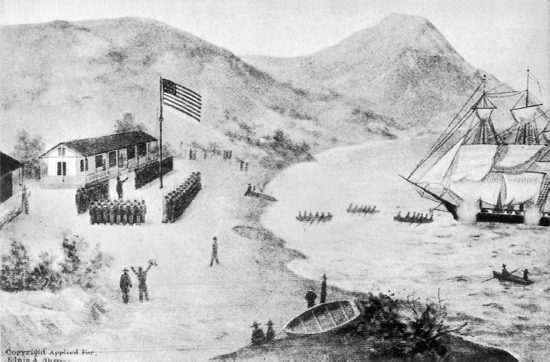

AMERICAN FLAG RAISED AT YERBA BUENA (1846)

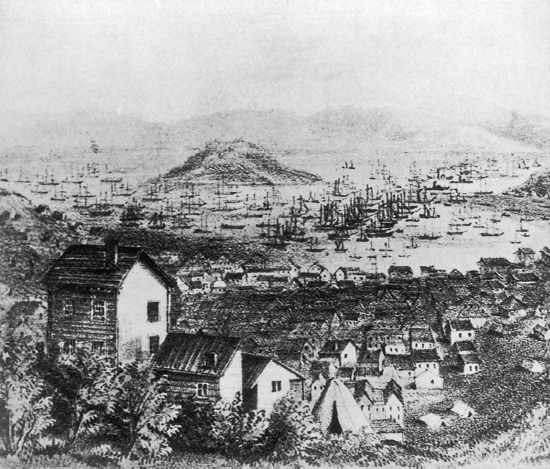

YERBA BUENA COVE CROWDED WITH SHIPS (1849)

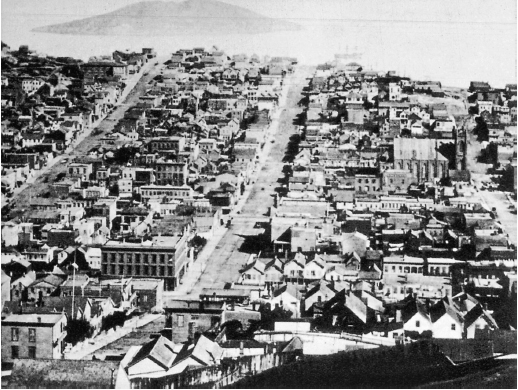

PANORAMA FROM RUSSIAN HILL | George Fanning |

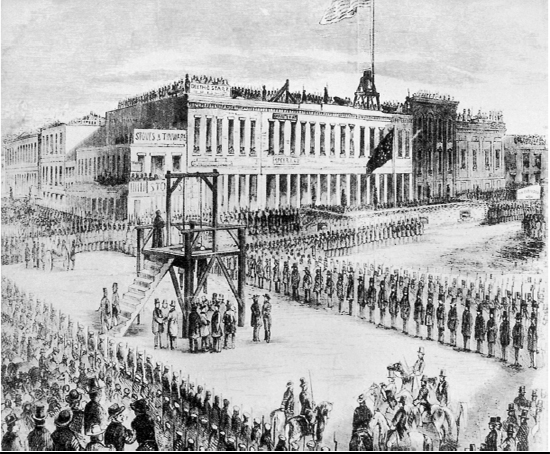

EXECUTION BY THE SECOND VIGILANCE COMMITTEE (1856)

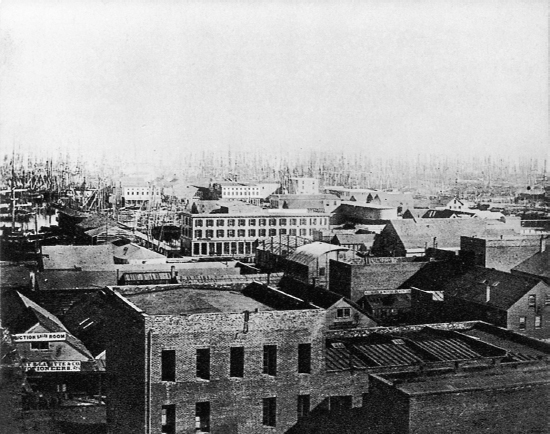

BUSINESS DISTRICT IN 1852

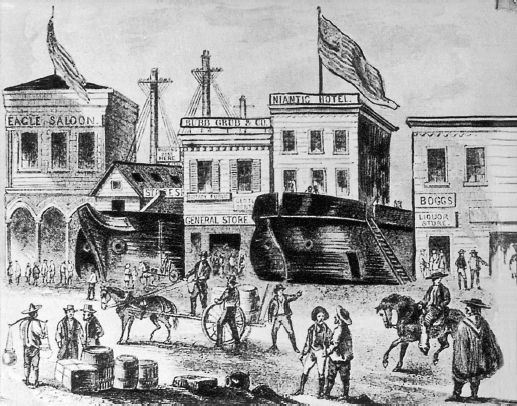

ABANDONED SHIPS ON WATERFRONT PRIOR TO 1851

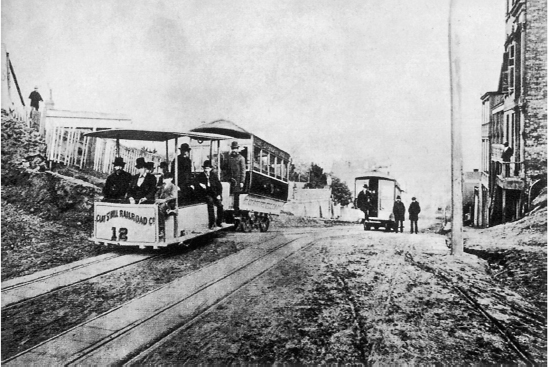

THE FIRST CABLE TRAIN (1873) | J. W. Harris |

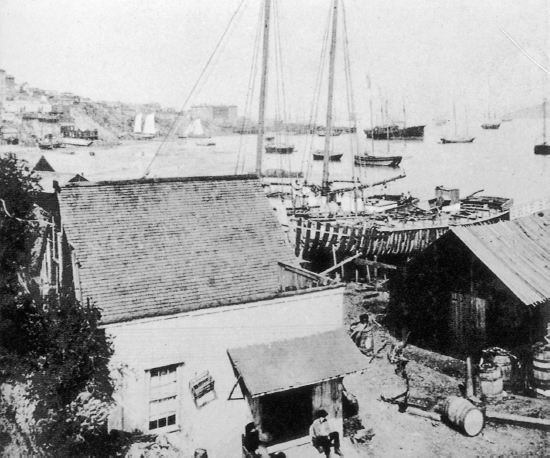

SHIPBUILDING SOUTH OF RINCON POINT (1865)

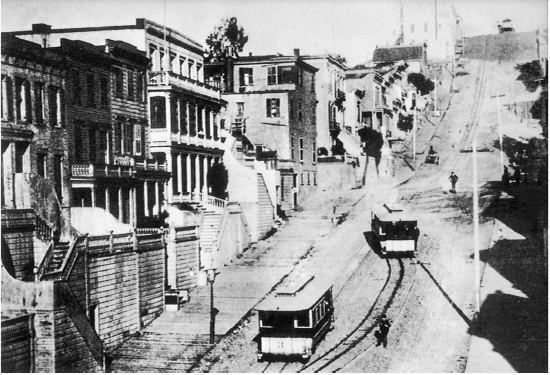

GREENWICH STREET CABLE CAR CLIMBING TELEGRAPH HILL (1884)

VALLEJO STREET WHARF IN EARLY SIXTIES

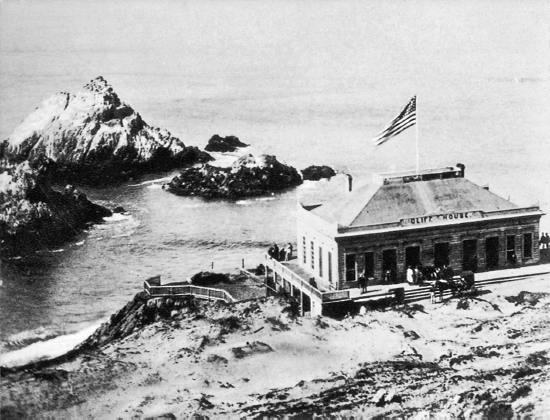

CLIFF HOUSE (1866)

James Hall | BARBARY COAST (1914) |

LOOKING DOWN KEARNY STREET TOWARD MARKET

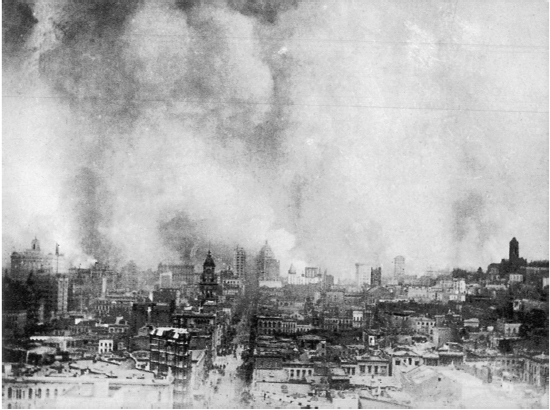

GREAT FIRE OF 1906

AFTERMATH

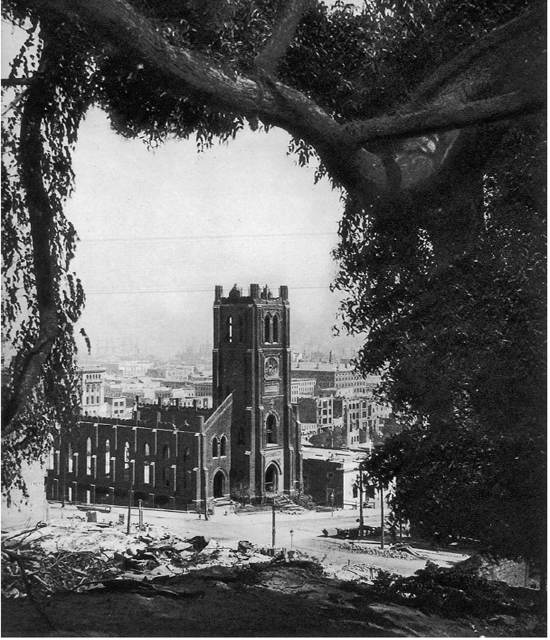

RUINS OF OLD ST. MARY'S CHURCH (1906)

It was the “Sensation Era” which saw the rise of the melodeons or variety houses, whose insouciance and camaraderie of atmosphere were to be found nowhere else but in San Francisco. They reflected the life of the city as the more respectable, more resplendent theaters did not. The girls who so cavorted might be found variously at the Bella Union, Gilbert's, and the other melodeons, in such extravaganzas as The British Blondes, The Black Crook, The Black Rook, or The Black Rook with a Crook.

The “big time” theaters of the city came and went, and the “inquitous” Bella Union outlived them all, impudently mocking the pretensions of the great. There were other melodeons: the Alhambra (later the Bush Street Theatre); Gilbert's Melodeon (later the Olympic); the Temple of Music (later the Standard); Buckley's Adelphi; the Pacific Melodeon and hosts of others of less importance. But of all these the Bella Union was the prototype. In the burlesques was the healthy spirit of satire; the minstrels alone had the temerity to deflate the balloon pretensions of the tycoon age. Many of the performers are still remembered: Lotta Crabtree, Joe Murphy “The Great,” Joseph and Jeff de Angelis, Eddie Foy, Ned Harrigan, Eliza Biscaccianti, Ned Buckley, James Herne, and the incomparable Harry Courtaine. A periodic drunkard, irresponsible, incurable, the despair of managers and the delight of audiences, Courtaine always returned and was always forgiven because there was no performer like him in the city.

The curtain went up on a new era, when William C. Ralston opened his new California Theater in 1869. In the audience were Bret Harte, Leland Stanford, James Fair, James Flood, John Mackay, and Emperor Norton. The name of the play was Money. A Bulletin reporter said rapturously of the drop curtain: “…the lookers-on were held breathless…with a thrill of surprised delight…” No less thrilling had been the scene outside the building, where grandes dames in full silk gowns had been met by the host, Lawrence Barrett. Presently they heard from his lips the dedicatory poem—a rapturous incoherency from the pen of Bret Harte.

The building of the California Theater was the signal for Tom Maguire's decline. The actors for whom Ralston built this sumptuous house, John McCullough and Lawrence Barrett, had both, ironically enough, been brought to San Francisco by Maguire. When his Opera House, on Washington Street, now “out of the way,” was destroyed in 1873, along with its rival Metropolitan, Maguire took over two theaters in the Bush Street district. But the old magic touch was gone. Ralston's entry into the theatrical world was the sign for other wealthy men to follow. In 1876 E. J. “Lucky” Baldwin built the Baldwin Academy of Music. Maguire, finding it harder to raise capital than in the old reckless days, became manager of Baldwin's Academy; but, in 1882, he threw up the sponge and departed for the East, never to return. With him departed an era.

Later houses were chiefly notable for their actor-managers, the excellent stock companies which played there, and the world-famous actors who appeared: Edwin Booth, Lawrence Barrett, Adelaide Neilson, Helena Modjeska, John Drew, Maurice Barrymore, and a host of others. San Francisco was, and long remained, the only city in the United States, outside of New York, where a high-salaried player could be assured a long and lucrative stay.

Probably the most dramatic incident in the history of the San Francisco theater attended the production of The Passion Play at the Grand Opera House in 1879. Written by Salmi Morse, a Jew, it was announced for March 8 and 9, with James O'Neill, a Catholic, as the Christus. A storm of protest followed—mostly from clergymen—and the Board of Supervisors threatened to prohibit the performance. They were forestalled by the production of the play on March 3. Riots broke out which threatened the safety of any recognizable Jew appearing on the streets. The production of the play continued, however, with interruptions, until April 21, when Morse withdrew it “in deference to public opinion.” The storm so affected him that a few months later he took his own life in New York.

The end of the century saw David Belasco, a humble prompter at the Baldwin Theatre, laying the foundation for his career. It saw little Maude Adams, aged nine, in Fairfax; Lillian Russell, a youthful unknown, in Sparks at the Standard; and Maurice Barrymore's talented daughter, Ethel, with a company including John Drew. Adelina Patti came to count out her $5,000 in cash every night before going on the stage, and Sarah Bernhardt, cooing, cursing, and dying in 130 roles; Anna Held augmented her theatrical prestige with publicity about beauty baths in milk; and Edith Crane, who appeared as Trilby, had full-sized photographs of her number 3 shoes published in the San Francisco papers. And that same Mauve Decade saw Henry Irving and Ellen Terry; a very risqué play at the Baldwin entitled Lady Windermere's Fan; and Blanche Bates in The Darling of the Gods. Marie Dressier came to dance the buck and wing, and Harry Houdini to make his mystifying escapes.

All but one of the city's theaters, both elegant and rowdy, were eliminated at a single stroke by the fire of 1906. By that time the early millionaire angels were dying and leaving their money to more sedate institutions such as art galleries, so the local drama began its struggle back with less assistance than it had enjoyed before. The possibility of its recovering an important place in the life of San Franciscans was doomed by the advent of moving pictures. Since then there have been many nights when no curtain rose anywhere in a once-great theatrical town.

In most of San Francisco's schools and recreation centers, however, amateur casts are unceasingly busy learning lines, making costumes, and staging performances. Hundreds of young San Franciscans have an exceptional appreciation for the drama because Maxwell Anderson, hoarding a trunkful of unproduced plays, put them through their Shakespeare at Polytechnic High. Many have worked with Dan Totheroh in the Mountain Play on Mount Tamalpais. Babies make their first acquaintance with the theater in fairy stories staged by The Children's Theater Association.

The Theater Union, a permanent amateur organization of the socially conscious type, staged John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men in their Green Street Theater in the Latin Quarter, long before that play became a hit on Broadway. In the fine little theater in Lincoln Park overlooking the Golden Gate, Maestro Guilo presents rarely heard opera bouffe. Jack Thomas’ Wayfarers have an esthetic slant; Barney Gould's Civic Repertory Theater plays in the Theater of the Golden Bough. The Federal Theater, too, until closed by Congressional law, presented such successes as Run Little Chillun and The Swing Mikado.

In every section of the city amateur performances may be seen regularly in Russian, German, Yiddish, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Arabic, Czech, Finnish, Polish, Japanese. Of professional interest are the French and Chinese theaters. The Gaité Française, or Théatre d'Art, of André Ferrier, at 1470 Washington Street, is the only permanent French theater in America, San Francisco's Chinese theater was professional from the outset, and it set out very early—in the 1850’s. Two Chinese theaters now operate in San Francisco, the Great China and the Mandarin—the only two in America—and companies still come from China to San Francisco under special permit.

For San Franciscans the theater has never been a shrine for the cult of indifferentism. Many were the nights when Lola Montez heard cries of “Bravo”; and many were the nights when she was pelted with vegetables. The spontaneity of theater audiences continues to draw comment from both sides of the footlights. John Hobart of the San Francisco Chronicle has stated succinctly San Francisco's distinction as a theater city: “New York audiences are quick, but easily bored; in Chicago, they are over-boisterous; in Boston, they are over-refined; in Los Angeles, they are merely inattentive. But in San Francisco the rapport between the people out front and the players behind the footlights is ideal, for there is stimulation both ways, and a kind of electricity results.”

MUSIC MAKERS

In one of San Francisco's gambling saloons, the El Dorado, a female violinist, “tasking her talent and strength of muscle,” alternated musical offerings with exhibitions of gymnastic skill. At the Bella Union five Mexicans strummed the melodies of Spain. At the Aguila de Ora a group of well-trained Negroes gave the city's first performance of spirituals. Meanwhile, from lesser bars and shanties issued a cacophony of singing, stomping, and melodeon-playing.

This was the town with hundreds of suicides a year, the town that stopped a theatrical performance to listen to an infant crying in the audience. It was the town of Australia's exiled convicts, of professors turned bootblacks, of a peanut vendor wearing a jurists's robes. Men outnumbered women twelve to one, had built a hundred honky-tonks but only one school. Here was humanity suspended in an emotional vacuum—or what would have been a vacuum but for the lady gymnast tripping from trapeze to violin and the Negroes harmoniously invoking glory. The demand for music was furious—and furiously it was supplied. Eventually normal living conditions were established; but the stimulus of music had been accepted as one of the permanent necessities.

The Gold Rush ballads had a tranquil prelude in the Gregorian chant taught by the Franciscan friars to the mission Indians. An observer, visiting one of the missions in later years, spoke of these choirs: “The Indians troop together, their bright dresses contrasting with their dark and melancholy faces… They pronounce the Latin so correctly that I could follow the music as they sang…” The friars next taught the Indians to play the violin, ‘cello, flute, guitar, cymbal, and triangle, and their neophytes surprised them by producing a lyrical rhythm unlike either the religious or secular.

Meanwhile, the Spaniards on their ranchos accompanied the day's activities with singing. In the midst of weaving, cooking, planting, and riding, the rancheros found time to celebrate at seed time as well as at harvest; they danced at all three meals. But the Spaniards’ lively and nostalgic airs were destined to be silenced by lusty throats crying for gold.

As early as 1849, the city's cafes began to cater to their patrons’ diverse musical tastes. At the El Dorado, an orchestra “played without cessation music ranging from Mendelssohn and Strauss to the latest dance trot”; and Charley Schultz, who enticed customers into the Bella Union with his violin and singing, brought to San Francisco the Hawaiian tune, “Aloha,” to which he sang, “You Never Miss Your Sainted Mother ‘Till She's Dead and Gone to Heaven.”

More to the miners’ liking were songs that celebrated their own exploits, like “The Days of Old, the Days of Gold, and the Days of ‘49,” first sung by Charles Benzel (known on the stage as Charles Rhodes), who came with the Argonauts. Another favorite was “A Ripping Trip,” sung to the tune of “Pop Goes the Weasel”:

“You go aboard a leaky boat

And sail for San Francisco.

You've got to pump to keep her afloat,

You've got that by jingo.

The engine soon begins to squeak,

But nary a thing to oil her;

Impossible to stop the leak,

Rip goes the boiler.”

Other concerns of the miners were chronicled with “The Happy Miner,” “The Lousy Miner,” “Prospecting Dream,” “The Railroad Cars Are Coming,” “What the Engines Said,” “What Was Your Name in the States?” These ballads were supplemented by songs brought from foreign homelands.

But many citizens soon demanded more cultivated fare. San Francisco's first concert was performed at the California Exchange on Monday afternoon, December 22, 1850—an exquisite execution of the classics on a trombone by Signor Lobero. Shortly after this the Louisiana Saloon gave a concert. But the attempt to uplift was only half successful; later the Alta California felt it necessary to admonish the audience: “We would respectfully advise gentlemen, if they must expectorate tobacco juice in church or at the theatre that they…eject it upon their own boots and pantaloons…” The Arcade Saloon announced a series of “Promenade Concerts a la Julien.” The Bella Union countered with the following invitation: “Grand vocal Concert with Accompaniment—to the lovers of Music of Both Sexes—”

The Germans of San Francisco contributed their substantial talents to the city's musical development. Turnverein organizations became the center and stimulus of choral societies; by 1853, four German singing societies were in full swing and had held their first May Day festival.

Miska Hauser, Hungarian violinist, originated the first chamber music group. His own words, appearing in his collected letters, tell the story: “The Quartett which I organized so laboriously gave me for a long time more pleasure than all the gold in California…the Quartett in its perfection as Beethoven saw it, this mental Quadrologue of equally attuned souls.… My viola player died of indigestion—and for some time I will miss the purest of all Musical pleasures.… Too bad that the other three were not solely satisfied with the harmonies of the Beethoven Quartett. They want a more harmonic attribute of $15 each for two hours…”

Mr. Hauser may have had some difficulty in sustaining enthusiasm among his attuned souls, but, in the fifties and sixties, opera burst the town wide open. Eliza Biscaccianti, Catherine Hayes, and Madam Anna Bishop gave the city its first reputation as an opera-loving community. When Biscaccianti opened her first opera season on March 22, 1852, at the American Theatre, there were more calls for conveyances than the city could provide. According to the Alta California of March 24: “…the evening marked an era in the musical, social and fashionable progress of the city.” Despite such appreciation, Mme. Biscaccianti returned to San Francisco six years later to find that her place had been taken by Kate Hayes, press-agented as the “Swan of Erin.”

San Francisco lionized these singers in a manner befitting the legendary heroines whose lives they portrayed. When Madam Biscaccianti sang Rossini's Stabat Mater, “Fire companies came out in full uniform to honor her and on one occasion their enthusiasm was so great they unhitched the horses from her carriage and pulled her to her hotel.” To Miss Hayes also the volunteer firemen gave undeniable proof of their delight.

How the firemen found time from drilling, fighting fires, and attending luminaries to make music of their own is a record of ingenuity. Several companies, however, gave band concerts both in and outside the city. Many other amateur groups often augmented professional offerings. Instrumental ensembles and singing societies were formed by immigrants from France, Great Britain, Switzerland, and a little later by Italians, Finns, and other Scandinavians. Professional musicians, amateurs, and audiences were en rapport during the invigorating epoch of the Gold Rush. Thus, by 1860, a rich musical tradition was well on its way to becoming permanent.

The development of symphony music was given its initial impulse by Rudolph Herold, pianist and conductor, who came to California in 1852 as accompanist to Catherine Hayes. The first of Herold's concerts of notable magnitude occurred in 1865, when he conducted an orchestra of 60 pieces at a benefit concert for the widows and children of two musicians. In 1874 he began his annual series of symphony concerts with an orchestra of 50 pieces, continued, with no financial succor to speak of, until 1880. After Herold's retirement, symphony concerts were given more or less regularly under such conductors as Louis Homeier, Gustav Hinrichs, and Fritz Scheel. Scheel, who later founded the Philadelphia Orchestra, was a musician of genius, esteemed by such renowned contemporaries as Brahms, Tchaikovski, and Von Bülow.

No American theater did so much to popularize opera as the Tivoli, best remembered of all San Francisco's theaters, which Joe Kreling opened as a beer garden in 1875, with a ten-piece orchestra and Tyrolean singers. Rebuilt in 1879, it became the Tivoli Opera House. Its career began happily with Gilbert and Sullivan's Pinafore, which ran for 84 nights. For 26 years thereafter it gave 12 months of opera each year, never closing its doors, except when it was being rebuilt in 1904: a record in the history of the American theater. For eight months of the year light opera—Gilbert and Sullivan, Offenbach, Van Suppé, Lecoq—was performed, and for four months, grand opera, principally French and Italian, occasionally Wagner. From the Tivoli chorus rose Alice Nielson, the celebrated prima donna.

William H. Leahy, familiarly known as “Doc,” who became manager of the Tivoli in 1893, was a keen judge of musical talent. His greatest “find” was Luisa Tetrazzini, whom he discovered while visiting Mexico City, where she was a member of a stranded opera company. In 1905 Tetrazzini made her San Francisco debut at the Tivoli as Gilda in Rigoletto and became forthwith the best-beloved singer in the city. When San Francisco was rebuilt after the earthquake and fire of 1906 (as was the Tivoli), Tetrazzini returned to sing in the street, in front of the Chronicle office at Lotta's fountain, on Christmas Eve, 1909. Jamming the streets in five directions was the densest crowd ever seen in the city. She also sang at the fourth Tivoli, opened in 1913. But the heyday of the famous theater was over; and on November 23, 1913, it gave its last operatic performance with Leoncavallo conducting his own I Pagliacci.

How permanent was the city's musical tradition was proved some 75 years later, when the citizens of San Francisco made their symphony orchestra the first and only one in the Nation to be assisted regularly with public money. Since its debut concert in 1911, the San Francisco Symphony had enjoyed more than local respect, under the successive direction of Henry Hadley, Alfred Hertz, Basil Cameron, Issay Dobrowen, and Pierre Monteux. But during the 1934-35 season, conditions became so acute that of the playing personnel only the director, concert-master, and solo ‘cellist remained. The situation was remedied by taxpayers who gave a half-cent of every dollar that found its way into the municipal coffers.

Pierre Monteux, conductor since 1935, an ex-associate of the Metropolitan Opera and a former conductor of the Boston Symphony and several European organizations, has done much to reaffirm the orchestra's position. Beginning in 1937, the season—curtailed during the depression—was increased to 12 concert pairs, carrying over 18 weeks. The San Francisco Symphony was the first major orchestra to admit women to the playing personnel. It has also taken an interest in such youthful prodigies as Yehudi Menuhin, Ruggiero Ricci, Grisha Goluboff, and Ruth Slenczynski.

The San Francisco Opera Association owes its existence largely to Gaetano Merola, its general director, who came to California with an organization headed by Fortune Gallo, one of the many traveling companies that visited San Francisco following the twilight of the Tivoli. The present San Francisco Opera Company made its inaugural bow before the public in September, 1923, in the cavernous Civic Auditorium, originally built for convention purposes. In 1932, after 20 years of personal and political wrangling, the War Memorial Opera House—first municipal opera house in the United States—was completed.

The season at the present time is divided into a regular subscription series of 11 performances and a popular Saturday night series of three. In its 17 years of existence, the San Francisco Opera Company has produced no single star of the first magnitude from its own ranks, but it has imported such singers as Lawrence Tibbett, Lotte Lehman, Lily Pons, Elizabeth Rethberg, Kirsten Flagstad, Lauritz Melchior, and Giovanni Martinelli. The popular-priced San Carlos Opera Company's performances, during the unfashionable late winter months, invariably sell out.

The “quadrologue of equally attuned souls” that Miska Hauser tried vainly to keep together is come to life in the present San Francisco String Quartet, a lineal descendant of the earlier Persinger, Hecht, and Abas ensembles, which played for many years in and near San Francisco. The San Francisco String Quartet has held the leading position among the city's chamber music artists since 1934.

The NorthenrCalifornia Music Project in San Francisco (formerly the Federal Music Project), now under the direction of Nathan Abas, not only has performed standard choral and symphonic works, but has resurrected with acute musical vigilance the opera bouffe, so popular with Europeans. Erich Weiler has given the operas English librettos, their humor pointed up with modern colloquialisms; and the artists have caught their spirit of hilarious pasquinade. The project also maintains a free school of musical instruction for those unable to afford private training.

Gaston Usigli, who directs the Bach festival each summer at Carmel, has been heard as guest-conductor with the project's orchestra, as has Dr. Antonia Brico, one of the few women in the world to wield a baton effectively. Arnold Schönberg directed the orchestra in the San Francisco premiere of his own tone poem, Pelleas and Melisande. San Franciscans had to wait for the project orchestra's performances to hear Dmitri Shostakovich's First Symphony, and Paul Hindemith's Mathis der Maler. The project's chorus, as well as its orchestra, has composed its programs with imagination and initiative. But perhaps the most significant value of these musical organizations has been the opportunity they have given San Francisco composers and audiences to appraise music written locally. Exciting events were the world premieres of Ernst Bacon's Country Roads (Unpaved), Nino Comel's The Conquest of Percy, and Tomo Yagodka's Sonata for Piano and Orchestra.

The impact of the modern environment on the sensibilities of the artist has seldom been better expressed than by San Francisco's Henry Cowell. Though most audiences have been staggered, technically trained composers recognize the theoretical value of Cowell's contribution to modern music. In the Marin hills overlooking the city, Ernest Bloch composed his rhapsody America, while serving as director of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Ray Green and Lew Harrison, local exponents of the modern experimental school, have written instrumental music and brilliant compositions for dance groups. John St. Edmunds, composer of nearly 400 songs somewhat more traditional in technique, received in 1937 the Columbia University Bearns Prize.

To many, the Barbary Coast's unbroken hum of melodeon, piano, Mexican orchestra, and singer was only San Francisco's brawling night voice. But one man caught in these sounds the musical implications of a future rhythm. This man was Ferdinand Rudolph van Grofe—Ferde Grofe—incomparable arranger of jazz, composer of Grand Canyon Suite and other notable interpretations of the American scene. As an extra piano player on call at the Old Hippodrome and Thalia, Barbary Coast resorts, he recorded in his mind a medley of folk songs, Negro dance tunes, and sailor's chanties. “The new music in the air along Pacific Street…did something to me!”

When Grofe left the Barbary Coast to play the piano with Art Hickman's band at the St. Francis Hotel, the two arranged music that was different and sparkling. Other orchestra leaders who played in San Francisco—Paul Whiteman, Rudy Seiger, and Paul Ash—became conspicuous exponents of this new music. Recent band leaders who have taken off from San Francisco on their musical flights include Paul Pendarvis, Dick Aurandt, Frank Castle, Carl Ravazza, and Ran Wilde.

Home music makers in San Francisco often aspire to the highest professional standards. Amateur groups frequently meet to forget the tensions of the day in the sanity of Brahms or Bach, or in the work of local composers. Both the playing and the composing are marked with a strong beat of self-reliance, in whose echo can be heard the promise of San Francisco's musical future.

SAN FRANCISCO GOES TO CHURCH

For 60 years before the founding of Yerba Buena, the padres of Mission Dolores heard their Indian converts recite the Doctrina Christiana, watched their Mexican parishioners lumbering over the sand hills in oxcarts to celebrate saints’ feast days. And hardly had the first Argonauts pitched their tents around Portsmouth Square before a Protestant clergyman rose to deliver the doctrine of Methodism. Today nearly 300 churches, representing more than 50 denominations, exert a vast influence over the lives of thousands of San Franciscans. Many were founded amid the turbulence of the Gold Rush, others in the era of industrial expansion. Some have accepted high responsibilities in the city's struggles for public order. Issues of the Civil War, of State and municipal politics were declared from their pulpits.

Sam Brannan's Latter-Day Saints assembled in harbor master William A. Richardson's “Casa Grande” in 1847, internal dissension—and the Gold Rush—soon caused them to lose their influence. Throughout the winter of 1848 Elihu Anthony, a layman, preached to packed audiences in the Public Institute. His rival, who drew a like number of listeners to this town meeting-house in the Plaza, was the Reverend Timothy Dwight Hunt, a Congregationalist missionary who followed his Argonaut flock from the Sandwich Islands. On his arrival in San Francisco, an enthusiastic citizenry elected him chaplain of the city for one year at a salary of $2,000.

Gold-mad San Francisco offered opportunities for conversion only to such heroic missionaries as that Reverend William “California” Taylor, who conducted open-air meetings on Portsmouth Square in 1849 and became the most renowned of the city's host of street preachers. This resourceful Methodist's approach to the adamantine hearts of his listeners he described later in his memoirs: “Now should a poor preacher presume to go into their midst, and interfere with their business, by thrilling every house with the songs of Zion and the peals of Gospel truth, he would be likely to wake up the lion in his lair.… I selected for my pulpit a carpenter's work-bench, which stood in front of one of the largest gambling houses in the city. I got Mrs. Taylor and another lady or two comfortably seated, in the care of a good brother, and taking the stand, I sung on a high key, ‘Hear the royal proclamation, the glad tidings of salvation’,…” The good Reverend Taylor's summons brought people tumbling out of saloons and dancehalls “as though they had heard the cry ‘Fire!’ ‘Fire!’ ‘Fire!’ ” Many remained to listen with respect.

In 1854, the Reverend William Anderson Scott, D.D., LL.D., preached his first sermon in San Francisco to a crowd in a dancehall. Neighboring resorts closed during the services, while bartenders, card-dealers, and female entertainers flocked to hear this scholarly Presbyterian from one of New Orleans’ largest churches. Subsequent meetings resulted in the construction in 1854 of a church on Bush Street, in a district then notorious for its dancehalls, gambling saloons, and dens of vice. In 1869 this neighborhood became so boisterous that the congregation had to seek a new home. But the Reverend Dr. Scott was no longer on hand to lead them. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he had preached the right of secession to an outraged membership, while a mob of Northerners stormed the front door of his church. Spirited out a rear exit by a loyal female supporter, he was whisked away in a carriage to a ship that took him to safety in New York.

Among claimants to the honor of having erected the city's first Protestant church, Baptists point with pride to that makeshift affair of lumber and sailcloth into which the Reverend Osgood C. Wheeler led his little flock in March, 1849. The Baptist pastor closed his sermon in the spring of that year with a prediction of the city's great commercial future, urging his listeners to build an organization able to cope with so portentous a destiny. The Baptists were to prove equal to their obligations when the Reverend Isaac S. Kalloch headed the reform movement that elected him mayor in 1879.

Meanwhile the six loyal followers of the Reverend Albert Williams, a Presbyterian clergyman, had met in a tent and laid plans for establishing a church of their own. When the prefabricated place of worship arrived from the East and was dedicated, thirty-two ladies attended the proceedings, much to the amazement of the male population.

Just as the Gold Rush offered opportunities for every profession, it welcomed every creed. In such an atmosphere the timid religionist was as lost as the timid gambler, but for the resourceful there was a place. When the luckless miner or workman had nowhere else to turn, he could find a champion of his rights in the pastor of some friendly church. Even the last hours of the Vigilantes’ victims were cheered by spiritual consolation.

Of the Protestant sects which have accepted leadership in public affairs, none has had so decisive an influence on San Francisco and the State as the Unitarians. This denomination, during the critical period of the Civil War, had as its Abolitionist representative in California the fiery young evangelist, Thomas Starr King. He was only 35 when, in 1860, he took over the pastorate of San Francisco's Unitarian Church. David Broderick, leading opponent of the State's powerful secessionist minority, had been killed the previous year; and Colonel E. D. Baker, having been elected United States Senator from Oregon, had left California with a ringing appeal for the election of Lincoln. Thus the task of holding the State in the Union column fell on the frail shoulders of the young preacher from Boston, whose personal charm and spellbinding oratory were instrumental in saving California with the election of Leland Stanford as governor in 1861. King's death four years later was due to his strenuous efforts collecting funds for the United States Sanitary Commission, the Red Cross of the Northern armies.

While Lincoln hesitated to proclaim the issue of freedom for the slaves, Thomas Starr King appealed with Abolitionist fervor: “O that the President would soon speak that electric sentence,—inspiration to the loyal North, doom to the traitorous aristocracy whose cup of guilt is full!” That King's idealism went beyond the issues of his day is revealed in his lectures in defense of both the Chinese in California and those white laborers whose hand was raised against them.

The Nation observed King's passing with the firing of minute guns in the Bay; flags hung at half mast on foreign vessels in the Bay, on consulates and all public buildings in San Francisco. In 1927 the California Legislature bracketed his name with Junipero Serra's, and, with the $10,000 appropriated for the purpose in 1913, erected companion statues of these two official California heroes in Statuary Hall, Washington, D. C.

The Episcopal Church can lay claim to the most romantic origin of all local religious institutions. Its Book of Common Prayer was used for the first time on American soil by the Golden Hinde's chaplain Francis Fletcher, in the service held on the shore of Drake's Bay on June 17, 1579 (old style). Two hundred and seventy years later, in 1849, the Reverend Flavel Scott Mines from Virginia established Trinity Church; and in the same year Grace Church was founded. When Bishop Kip, in 1863, placed his Episcopal Chair in the latter, he thereby made it the first Episcopal cathedral in the United States. Perhaps no other religious leader in the city's history has occupied quite such social prominence as was accorded Bishop Kip. To a gay generation he represented a serenity of faith and a Christian liberalism in which the innocent frivolities of social life might be reconciled with religion. His successor, Bishop Nichols, lived to see the realization of his dream of a cathedral which, when finally completed, would be worthy of his church's ancient tradition. After the 1906 fire, which destroyed the original Grace Cathedral, wealthy families donated sites of their charred mansions on Nob Hill to the Episcopal diocese; and in 1910 the cornerstone of the present majestic Grace Cathedral was laid.

To Gold Rush San Francisco also came leaders of the Roman Catholic faith; and the establishment of American rule offered an opportunity for the Catholic diocese in Oregon to found a pastorate of the Jesuit Order in San Francisco. That the prospects for this venture were more of a challenge than an invitation is clear from the record kept by a colleague of that Father Langlois who, in 1849, arrived to plant his faith “on the longed-for shores of what goes under the name of San Francisco but which whether it should be called the mad-house or Babylon I am at a loss to determine…” So hopeless appeared all but a handful of French-Canadians among the Argonauts that the good Father resolved to depend on these few strayed parishioners to form the nucleus of his congregation.

With the establishment of Bishop Joseph Sadoc Alemany's diocese at Monterey, however, and the early arrival in San Francisco of Father Maginnis to aid in the work, Father Langlois was able to say Mass and baptize the first convert in a new parish chapel. Soon after the arrival from Ireland, in 1853 and 1854, of several Sisters of Mercy, the city's first parochial school had enrolled 300 pupils. Once St. Patrick's Church was established, the firm foundation was laid for the progress of Catholicism in San Francisco. On Christmas Day, 1854, St. Mary's Church was dedicated as the cathedral seat of newly consecrated Archbishop Alemany, whose spiritual domain included California and Nevada.

Despite its history of missionary achievements antedating the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the Catholic Church in San Francisco had to start from scratch, after the 80 years of comparative prosperity in which Mission Dolores had shared. Though title to the land and buildings of Mission Dolores was not restored to the Church until 1860, it was occupied almost continuously by Franciscan or Picpus Fathers between the date of its secularization (1833) and the advent of American rule. The St. Thomas Aquinas Diocesan Seminary, operated at Mission Dolores between 1853 and 1866, was a pioneer in the revival of education; but its efforts to teach white children resemble the arduous pedagogy of the colonial period. Thus matters stood until, in 1855, the Jesuits began the establishment of the College of St. Ignatius, from which the present University of San Francisco has grown. However great the debt owed by Catholicism to the missions and to Junipero Serra, the church in San Francisco has derived its present prosperity from the Gold Rush and bonanza wealth in which it shared.

Two of the city's Hebrew congregations first assembled near Ports-mouth Square in 1849. Temple Emanu-El, founded by German Jews, and Temple Sherith Israel, whose original congregation, was composed mainly of English and Polish elements, constitute today San Francisco's chief citadels of reformist Judaism. These congregations provide magnificent and modern cultural centers for the city's liberal Jewry. Rabbi Nieto, leader of Sherith Israel congregation for 32 years, played a prominent part in the restoration of the city after 1906. His advocacy of welfare facilities in connection with synagogues resulted in the establishment of “Temple Centers” throughout the Nation. Today in San Francisco the Jews share with the Catholics, in institutions for public welfare which they have separately established, a major responsibility for the city's orphans and aged and destitute; most of the city's hospitals owe their origin and maintenance to Catholic or Hebrew congregations.

Especially characteristic of San Francisco is a host of lesser sects. From few city directories could be compiled such a list of denominations and churches as this: Seventh Day Adventists (both Greek and Chinese), Mexican Baptists, Buddhists (American and Japanese), Molokans (Russian Christians), Armenian Congregationalists, the Christian Spiritualist Church, the Father Divine Peace Mission, the Glad Tidings Temple, the Golden Rule Spiritualist Church, Jehovah's Witnesses (Negro), the Rosicrucian Brotherhood, the Society of Progressive Spiritualists, the Spanish Pentecostal Church, the Theosophists’ United Lodge, the Tin How Temple (Chinese), and the Vedanta Society.

From San Francisco's diverse population, tens of thousands (50,000 in 1940) each Easter morning make the difficult pilgrimage up the city's highest hill, Mount Davidson, to worship at the foot of the great cross on the peak. And, here, all forget their differences of creed in a common reverence to that religious spirit which has remained a social force since the city's earliest days.

GENTLEMEN OF THE PRESS

“Some contend,” said Yerba Buena's first newspaper in 1847, “that there are really no laws in force here, but the divine law and the law of nature; while others are of the opinion that there are laws in force here if they could only be found.” This polite apology for a state of anarchy may have caused some speculation among readers of Sam Brannan's California Star, but it foretold nothing of the militant and decisive role journalism was to play for half a century in the public affairs of San Francisco.

More indicative of this role was California's pioneer newspaper, the Californian, established in Monterey in 1846 and removed to Yerba Buena a year later. Its editor and publisher, when it became the Stars competitor, was that formidable Robert Semple who had helped lead the Bear Flag revolt and published manifestoes of the American occupation. Hardly, however, had Brannan's little sheet begun to ridicule the Californian's mild reports of “Gold Mine Found” and “Doc” Semple's patriotic oratory, when news from Sutter's mill race caused both papers to suspend publication. Their publishers and printers joined the stampede to the diggings.

Late in 1848, Edward C. Kemble acquired the Star, of which he had been editor when its weekly circulation “outside town and other parts of the globe” was a hundred copies; and, soon after, he bought the defunct Californian and combined the two papers under the name Star and Californian. With two new associates, printers from New York, Kemble issued in January, 1849, the Alta California, which became San Francisco's leading source of news for the next 30 years. Not until 1891 did it finally pass from the scene, having published, in its time, the letters written from Europe by Mark Twain in the 1860’s that were compiled in Innocents Abroad. Among its managing editors was Frank Soulé, co-author of the Annals of San Francisco.

The growth of rival journals, which by 1850 forced the Alta to become the first daily, continued throughout the decade with a luxuriance propagated by political factionalism and homesickness among the immigrant population. Not to be outdone, the Daily Journal of Commerce was issuing daily editions within 24 hours after its elder rival began doing so. Before the end of 1850, daily editions of The Herald, the Public Balance, the Evening Picayune, the California Courier, and the California Illustrated Times had appeared.

Despite the high mortality of the press of the Gold Rush era, Kemble in 1858 listed 132 periodicals as having appeared in San Francisco since 1850. Only dailies to survive the decade, however, were the Alta and The Herald.

That the majority of these organs were rather journals of opinion than newspapers is not surprising. Crime, gold strikes, and other sensational matters were so much the subjects of common knowledge that the press had to search far and wide for news of interest to its readers. The huge influx of immigrants from Eastern communities compelled numerous San Francisco papers to employ correspondents on the Atlantic seaboard, who dispatched bulletins by the steamers that brought also large batches of Eastern newspapers. The Overland Stage, reducing communication between St. Louis and San Francisco to 21 days after 1858, somewhat improved news-gathering facilities; and when a telegraph line was strung in 1861, news of national significance was available. The quality of printing, with the introduction of the Hoe cylindrical press in the 1850’s, likewise was improved; and by 1860 a grade of paper better than foolscap was obtainable.

Editorials and classified advertising, however, continued to be the main features of weeklies and dailies alike. Though articles were rarely signed, the style of each editor was instantly recognizable to readers who, according to John P. Young's History of Journalism in San Francisco, “looked not so much for intelligence as to see who was being lambasted.” This highly personal tone was employed also by editors of less slanderous journals, such as the columnist of the Golden Era who addressed his correspondents by their initials and gave fatherly advice. Perhaps this friendly policy had something to do with making the Golden Era the city's leading weekly for 30 years after its establishment in 1854.

In the San Francisco of the Gold Rush era, newspaper editors had to be printers, writers of verse, and hurlers of insults; they had to take sides in political controversies, during which their opponents might at any moment attack them in a fist fight or challenge them to a duel. Catherine Coffin Phillips, in her history of Portsmouth Square, states that above one editor's desk was hung this laconic placard: “Subscriptions Received From 9 to 4; Challenges From 11 to 12 only.”

Bitterness over the slavery issue was the cause of frequent brawls and armed encounters. Duels were of such common occurrence, that newspapers mentioned them only in passing, unless they involved prominent persons. A. C. Russell, an editor on the staff of the Alta California, having escaped harm in a duel with pistols, was subsequently stabbed in an “affair of honor” fought with bowie knives. The Alta's managing editor, Edward Gilbert, was killed in 1852 by a henchman of Governor John Bigler, who defended his boss against an item intended to make him appear ridiculous. In that same year, the Altas support of David Broderick, campaigning for election to the State Senate on an anti-slavery platform, caused the wounding of another of its editors by an editor of the pro-slavery Times and Transcript. An editor of The Herald, a daily fighting corruption in municipal politics, was shot in the leg by a city supervisor. James King of William (a distinction invented to avoid confusion with other James Kings), who founded the Evening Bulletin in 1855, did not survive his first encounter with a spokesman for the embattled politicians. His death, from a wound inflicted by the supervisor who was editor of the Sunday Times, was, however, the signal for mobilization of the Vigilance Committee of 1856. The office of the Morning Herald, the Alta's most potent rival, was stormed by a mob, who burned its editions in the streets for opposing the committee's work.

The close of the Civil War saw the establishment of the only two morning dailies that have survived since 1865: the San Francisco Examiner and the San Francisco Chronicle. The Dramatic Chronicle, edited by two brothers in their teens, was so well received after “scooping” the news of Lincoln's death that Charles and M. H. de Young, in 1868, were able to transform it into the daily Morning Chronicle. For the next 15 years, under the management of the belligerent Charles, the Chronicle entertained its readers with scandal and political onslaughts, while its editor defended himself in duels and libel suits. Following a bitter campaign against the Workingman's Party and its candidate for mayor in 1879, Charles de Young was killed; and for the next 45 years the Chronicle was under the direction of his younger brother. Throughout his long career, M. H. de Young, through his managing editor, John P. Young, made his paper a force for political conservatism and social order. Follower of an anti-slavery tradition, the Chronicle remained staunchly Republican, its viewpoint attracting to its staff such writers as Will and Wallace Irwin and Franklin K. Lane, who was Secretary of the Interior under President Wilson. Not until the 1930’s, however, did it suddenly recapture, under the management of young Paul Smith, the sophisticated quality of its earliest editions.

Leading rival of the Chronicle for morning circulation, William Randolph Hearst's Examiner was founded on the ruins of the pro-slavery Democratic Press, which a mob, provoked by news of President Lincoln's assassination, had wrecked beyond repair. Despite popular indignation, the staff of the Democratic Press was carried over intact to the Daily Examiner. From its appearance on June 12, 1865, until a wealthy miner named George Hearst bought it in 1880, the Examiner defended the interests of Southern Democrats who remained entrenched in California politics. With its transfer to young William Randolph Hearst in 1887, however, began that sensational career which made the Examiner's owner a storm center of American journalism for 50 years.

With bonanza millions at his disposal, and a genius for showmanship, Hearst gathered together a staff that included some of the best newspaper talent that money could buy. S. S. (Sam) Chamberlain, protégé of James Gordon Bennett and founder of the first American newspaper in Paris, became managing editor. The daring resourcefulness of the Examiner's reporters delighted its readers and filled its rivals, especially the Chronicle, with alarm. Unheard-of was its printing of two full pages of cablegrams from Vienna, relating the mysterious death of Crown Prince Rudolph of Austria and the Baroness Marie Vetsera. Examiner correspondents dispatched news from the ends of the earth. Announced with glaring headlines and illustrated with photographs, this dramatization of the news caught the imagination of the public. To the reporting of local news the Examiner brought innovations no less startling. One of its editorial writers, the cynical Arthur McEwen, once remarked that reporters risked their necks for the sake of a story to make the public exclaim: “Gee whiz!”

Jack London was on the Examiner's brilliant staff in the closing decades of the last century. The modern comic strip was born as cartoonists James Swinnerton, Bud Fisher, Rube Goldberg, R. Dirks, and Homer Davenport labored side by side creating the “Katzenjammer Kids,” “Little Jimmy,” and “Mutt and Jeff” (created by Fisher from habitués of the old Tanforan Race Track). Ambrose Bierce's “Prattle” made him the most feared of the Examiner's columnists. One of his malevolent verses, predicting the assassination of President William McKinley, was interpreted afterwards as an incitation to the act. This gave the popularity of the Hearst papers a setback, but Hearst was already on the way toward establishing his powerful chain. Though the Examiner remains one of the leading newspapers on the Coast, it has long since dropped its original pro-labor policy. Vanished also from its offices is that droll atmosphere wherein Hearst himself “would sometimes preface his remarks to his editors by dancing a jig…” And not since H. D. (“Petey”) Bigelow wangled an interview out of three train robbers in a mountain hideout has the Examiner found a sensation to equal either that story or its author.

Of the city's two surviving afternoon dailies, the Call-Bulletin has the longer history. Its ancestor, James King of William's militant Bulletin, fought corruption in politics and finance for half a century. It was saved from oblivion in 1859, three years after its first editor's untimely death, by a publisher from New Orleans, G. K. Fitch, who later sold half his interest to Loring Pickering. Soon afterwards, the partners acquired the Morning Call, a cooperative paper issued by a group of printers claiming to be “men without frills.” Fitch became editor of the Bulletin; Pickering, of the Call. Though both papers were published under the same roof and ownership, their policies were deliberately antithetical. At a time when violent taking of sides was evidence of red blood, Pickering's Call dared to be nonpartisan. Not less outrageous than its objective reporting was its society page, on which the doings of “the Colonel's lady and Mrs. O'Grady” were chronicled side by side. For 30 years Fitch kept the Bulletin alive with caustic editorials and reportage in the crusading spirit of its founder. He fought waste in municipal administration and gambling on the stock exchange, assailed big corporations, and attacked political corruption in both Democratic and Republican parties.