Civic Center

“Above all the dome, seen so often like that of St. Paul's but dimly through the fog”

—MAURICE BARING

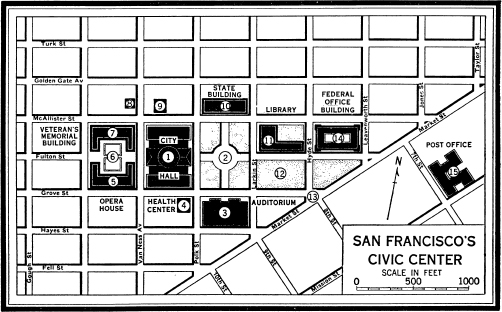

SAN FRANCISCO'S Civic Center constitutes a Beaux Arts monument to the city's cultural tradition, its achievements in democratic government, and its proud position among the commercial centers of the Nation. Dominated by the massive, symmetrical pile of the City Hall—whose dome, surmounted by a gilded lantern, soars high above the city—the wide plaza with its fountains, its trim shrubbery and acacias, its central concourse paved with red brick has been for the last quarter-century the focal point for all public demonstrations. The Civic Center has been the scene of welcome for so many celebrities and so many parades that henceforth—as Charles Caldwell Dobie has suggested—it is likely to become the most popular and historic of the city's landmarks.

The present group of eight buildings, built of California granite in variations of the massive style of the French Renaissance, is an example of city planning to contradict the city's once-famous reputation for letting things run wild. One by one these substantial structures have risen on those blocks within the apex of that angle formed by the convergence of Market Street and Van Ness Avenue which was cleared of debris and ashes after 1906. The $8,000,000 bond issue voted in 1912 laid the foundation for the project. As further funds become available and a need for new units arises, other structures will be added. Perhaps in time the dream of the Civic Center's original designer, D. H. Burnham, will be realized by the extension of its monumental plan to include the entire city.

Municipal government in San Francisco was not always so well-housed or so well-ordered. For more than a half-century after 1776 the seat of local government was a tiny dirt-floored two-room hut, home of the military comandante at the Presidio. Here in 1834 met the voters of the district of San Francisco to decide on eleven electors—who later chose the first ayuntamiento (town Council), consisting of an alcalde, two regidores, and a syndico. These officials entered upon their duties on January 1, 1835. In 1839 the Council was abolished. When the State came under American rule in 1846 Lieutenant Washington A. Bartlett of the United States Navy was appointed alcalde. Publicly charged in 1847 with misappropriating town funds (amounting to $750), he was acquitted but nevertheless was withdrawn to the Navy. At a meeting of the common Council of six members elected a few months later—which first convened in September 1847—the alcalde was permitted to preside over, but not participate in, the discussion. The governmental Situation was so confused that the editor of the California Star complained plaintively, “we have alcaldes all over…who claim Jurisdiction over all matters for difference between Citizens.”

There were to be many complaints, more vociferous, before the government of the growing town became orderly and predictable. At one time no less than three Councils each claimed sole right to govern. In 1847 an ordinance provided that two constables should “strictly enforce the law” and “receive for the service of any unit or other process, one dollar, to be paid out of the fines imposed upon cases.” In 1848 an ordinance was passed ordering the seizure of all money found on gambling tables, the money to go into the town coffers, but in that same year the lure of gold drained the town of so many inhabitants that at one time not a single officer with civil authority remained. Only 158 people were on hand to cast votes at the election held in October to reestablish some kind of civic administration. Too impatient to wait for the reestablishment of State government, the people met at a public mass meeting in February 1849, organized the Legislative Assembly, and proceeded merrily to make their own laws. The Assembly met 35 times before it was dissolved on June 4 by decree of the military governor of the State, General Bennet Riley. At an election held on August 1, 1,516 votes were cast, all for John W. Geary for alcalde. Later that month the ayuntamiento purchased the first public building under the American regime—the brig Euphemia, which it converted into a jail.

Anticipating by more than four months California's admission to the Union, the city was incorporated April 15, 1850. Under the charter adopted by the already functioning State legislature, a mayor, recorder, and Council of aldermen were elected on May 1. The police department was enlarged—but “not to exceed 75 men”—and a fire department headed by a chief engineer was established.

At its first meeting on May 9 the Council members promptly rifled the treasury by voting to pay the mayor, recorder, marshal, and city attorney annual salaries of $10,000 and other officials including themselves, $4,000 to $6,000. Later in the year, anticipating the celebration of the admission of the State into the Union, they each awarded themselves a handsome gold medal to cost $150, the expense to be borne by the city. Unfortunately the medals were not completed in time for the celebration; when they did arrive, the town fell into such an uproar that the councilmen prudently paid for the medals out of their own pockets and promptly melted them into “honest bullion.” Despite this, sacrifice, the city was $1,000,000 in debt before the end of the year.

The adoption of a new charter by the Legislature in 1851 did little to halt the extravagance of the officials or the depredations of the increasing criminal element. But the Consolidation Act passed by the State Legislature in the same year, which authorized merger of the City and County of San Francisco, creating a Board of Supervisors to replace the double board of aldermen provided for by the charter of 1851, served to establish a more stable civic government. It was to be San Francisco's organic law for 44 years. When the heat of the vigilante movement had subsided, a reform movement headed by the People's Party gained power and held it long enough to put comparatively capable men into office.

When the old city hall burned down, the idea of transforming the Plaza into a reputable center of municipal government moved the Council, in 1852, to purchase the Jenny Lind Theater, at Washington and Kearny Streets, for a new seat. So exorbitant was the $200,000 paid for the theater, however, that a storm of public criticism broke out. But the building had to serve. In 1865 the Board of Supervisors refused to pay the city's gas bill. The company promptly removed its lanterns from the Street posts and turned off the gas at the city hall. That evening the city fathers, each carrying a flickering candle, stumbled upstairs to discuss the lighting Situation.

Finally, in 1870, construction was begun on a new city hall “away out on Larkin Street” at a site then known as Yerba Buena Park (now the site of the Public Library). Originally a tangle of chaparral, this tract had become in 1850 Yerba Buena Cemetery. Economy was the watchword. The city fathers planned construction on the installment basis, paying each installment out of an annual special tax levy. But the piecemeal method of construction boosted costs to more than $7,000,000, far beyond original estimates, and delayed completion for many years. As the city grew it became apparent that the Consolidation Act no longer sufficed to serve its needs. Twice James Phelan, who headed the reform movement that swept him into the mayor's chair in 1897, attempted, with the aid of a Committee of One Hundred, to secure adoption of a new charter, but without success. But in 1900 the electorate accepted at last a freeholders’ charter which loosened the State Legislature's grip on municipal affairs, outlined a definite policy of municipal ownership of public Utilities, and substituted civil Service for the spoils system in civic administration.

But the new charter was not enough to protect the city government from the Ruef-Schmitz ring, into whose hands it fell in 1902. When the old city hall came tumbling down in less than 60 seconds at the first shock of the earthquake on April 18, 1906, municipal wrath gave impetus to the already gathering movement for cleaning house. In 1908 a Supervisors’ committee solemnly reported that “so far the most rigid inspection of the standing and fallen walls…have (sic) failed to disclose any large voids or enclosed boxes, barrels or wheelbarrows that have been told in many an old tale as evidence of lax supervision and contractors’ deceits.” But many San Franciscans went on believing “many an old tale.” And when they decided to build a new city hall, they were determined that its occupants should be more worthy of the public trust and more responsible for the public welfare.

The urgency of rebuilding the ruined city defeated the city planning efforts of Daniel H. Burnham, whose vision of a system of great boulevards encircling and radiating from the intersection of Market Street and Van Ness Avenue (and the extension of the Golden Gate Park panhandle) was not to be realized, but when the city began, in 1912, to plan for the Panama-Pacific Exposition, a part of the scheme was revived in modified form. A permanent staff of architects for the Civic Center (John Galen Howard, Frederick H. Meyer, and John Reid, Jr.) was appointed and a bond issue of $8,800,000 voted for purchase of land and construction of buildings.

Under the municipal ownership provisions of the new charter, Mayor Phelan's dream of “a clean and beautiful City” began to be realized. San Francisco became the first large municipality in the Nation to establish a city-owned Street railway system, which opened December 28, 1912. Under the supervision of veteran City Engineer Michael Maurice O'Shaughnessy, construction was begun at Hetch Hetchy of the great dam which bears his name and of the 168-mile aqueduct which brings Tuolumne River water to the city. The work continued over the next two decades until 1934. In 1913, under O'Shaughnessy's direction, the first comprehensive system of boulevards was formulated. In 1927 the San Francisco Municipal Airport was opened. By 1940, the city-owned Utilities system was valued at approximately $167,000,000.

Meanwhile the park system was increased to a total of 45 parks covering 3,170 acres (one-ninth of the city's area). Since the establishment in 1907 of a Playground Commission (since 1932 the Recreation Commission), municipal playgrounds have increased to a total of 45 (exclusive of 28 school playgrounds), where during the fiscal year 1937-38 nearly 4,500,000 persons participated in such activities as athletics, gardening, handicrafts, music, and dramatics. The San Francisco Unified School District in the same fiscal year (its 87th) was operating 102 public schools, including ten junior high and eight high schools and a junior college, enrolling an average of 81,297 students. The library system was extended to a total of 22 branches serving 130,000 persons. The M. H. de Young Memorial Museum and the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, a city-subsidized symphony orchestra and the only city-owned opera house in the Nation, San Francisco Yacht Harbor, Aquatic Park, and the municipal Fleishhacker Zoo—all added to San Francisco's attractions. And meanwhile, as San Francisco became a more healthful and attractive city, it also was becoming a safer one. Its decreasing crime rate—between 1938 and 1940 it was the only large city to register a decrease—attested to the efficiency of its police department; a study of 86 cities made in 1935 showed that San Francisco, although 11th among American communities in population, stood 20th in number of robberies and 35th in homicides.

Just as the city had outgrown the Consolidation Act of 1856, drawn up for a city of 40,000, so it outgrew the freeholders’ charter of 1900, drawn up for a city of 325,000. Beginning as a comparatively short document, the old charter had grown by process of amendment to 304 pages of articles, chapters, and subdivisions. In 1930 the voters elected a board of 15 freeholders to frame a new charter. Having studied the various forms of municipal government, the freeholders formulated a “strong mayor” plan which was adopted in March 1931 and put into Operation in January 1932, under the administration of Angelo J. Rossi. Under the new charter the mayor—writes Chief Administrative Officer Alfred J Cleary—is made “a strong and responsible executive, with the power of appointment of the principal officials and members of boards.” Officials whose duties are primarily governmental (policy-making) were continued in elective positions; those whose duties are primarily ministerial (carrying out policies), in appointive positions. To the Chief Administrative Officer was entrusted responsibility for supervision of departments headed by the latter and for long-range planning; to the Controller, responsibility for financial planning, management, and control. Under the new charter's provisions, the city's business must be Conducted on a cash basis and its budget balanced annually. An eleven-member Board of Supervisors was retained as the legislative branch of government and relieved of administrative duties.

POINTS OF INTEREST

I. Dominating the Civic Center, the CITY HALL, Van Ness Ave., Polk, McAllister, and Grove Sts., lifts its gold-embellished dome 308 feet above ground level—16 feet 25/8 inches higher than the National Capitol in Washington, D. C., as Mayor James Rolph used to boast. It was Rolph who broke ground for the new structure with a silver spade April 5, 1913. Second unit of the Civic Center to be completed, the City Hall was dedicated December 28, 1915, having cost $3,500,000. In the great rotunda under the dome, Rolph welcomed the world, receiving a long procession of celebrated visitors: the King and Queen of Belgium, Queen Marie of Rumania, Eamon de Valera, William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson. Here San Francisco made merry all night long to celebrate the Armistice in 1918. Here the funeral of President Warren G. Harding took place in 1923, and here, in 1934, Rolph himself lay in state.

Of gray California granite with blue and gold burnished ironwork, the building conforms to the French Renaissance style of the Louis XIV period, its east and west facades consisting each of a central pediment supported by Doric pillars and flanked on either side by Doric colonnades. Rising four stories high and covering two city blocks, it was designed by architects John Bakewell, Jr. and Arthur Brown, Jr. as a hollow rectangle, 408 by 285 feet, enclosing a square centerpiece covered by the dome.

On the Polk Street pediment, the symbolic statuary represents San Francisco standing between the riches of California and Commerce and Navigation; on the Van Ness Avenue pediment, Wisdom between the Arts, Learning, and Truth and Industry and Labor. The interior, with its marble tile flooring, is lavishly finished in California marble, Indiana sandstone, and Eastern oak. Grouped around the great central court are the offices of the Registrar, Tax Collector, and Assessor. From the center of the lobby a wide marble staircase leads to the second-floor gallery, off which are the Mayor's office and the chamber of the Board of Supervisors. Similar galleries overlook the court from the third and fourth floors. The vast dome, 112 feet in diameter, weighs approximately 90,000 tons and will withstand a wind load of 30 pounds per Square foot.

On the fourth floor is the SAN FRANCISCO LAW LIBRARY (open. Mon.-Sat. 9 a.m.-10:45 p.m., Sun. 10:30-4:30), a free, city-supported, reference and circulating library of about 30,000 volumes.

Near the Polk Street entrance is a bronze STATUE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN (Haig Patigian, sculptor), seated in meditative pose, one hand resting on his knee. Facing the Street named for him is a bronze STATUE OF HALL MCALLISTER (Earl Cummings, sculptor), a distinguished pioneer attorney.

2. The CIVIC CENTER PLAZA, Grove, Polk, McAllister, and Larkin Sts., with its broad red brick walks, its fountains playing in circular pools, its great flocks of pigeons, its flowerbeds and box hedges, is surrounded by a row of acacia trees and lined, along Larkin Street, by flagstaffs.

3. Since the CIVIC AUDITORIUM, Grove St. between Polk and Larkin Sts., was presented to the city by the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, events as diverse as political rallies, automobile shows, balls, prize fights, operas, symphony concerts, bicycle races, and circuses have been held here. Memorable have been the “Town Meetings,” where employers and union men met in amicable debate; the “dime” symphony concerts of the WPA Music Project; monster mass meetings demanding freedom for Tom Mooney; the National Conventions of the Democratic Party in 1920 and of the American Federation of Labor in 1934; and Max Reinhardt's presentation of The Miracle, for which the main auditorium was converted into a gigantic cathedral. Designed by Arthur Brown, Jr., the structure is four stories high, with a facade of California granite ornamented in carved stone and a pyramidal tile roof topped by a great tile-covered octagonal dome. Besides the main auditorium, seating 10,000, and the two companion auditoriums—Polk Hall and Larkin Hall, each seating 1,200—which flank it, it contains 21 smaller halls and twelve committee rooms. Over-hanging the vast arena, 187 by 200 feet, which can be enlarged to include the two companion halls or diminished by use of electrically operated curtains, is a spectacular canvas canopy painted to simulate sky and clouds, bordered by Gleb and Peter Ilyin's mural insets. From three sides great balconies overlook the 90-foot stage. The four-manual console of the great organ controls the six distinct parts: great, swell, choir, solo, pedal, and echo organs. The largest pipe is 32 feet long and 20 inches in diameter.

4. The city's public health supervision centers in the four-story HEALTH CENTER BUILDING (open weekdays 8-5), corner Grove and Polk Sts., erected in 1931-32. It houses various clinics, the Central Emergency Hospital, and offices of the Health Department of the Bureau of Inspection.

5. Twin structures—the OPERA HOUSE (open weekdays 10-4), NW. corner Van Ness Ave. and Grove St., and the Veterans’ Building (see below)—form the War Memorial of San Francisco, erected in 1932 as a tribute to the city's war dead. The buildings are similar in external appearance, patterned in classic style to conform with other Civic Center structures. Against the rusticated terra cotta of their facades, rising from granite bases and steps and surmounted by mansard roofs, are placed free-standing granite columns.

This, the Nation's only municipally-owned opera house (Arthur Brown, Jr., architect; G. Albert Lansburgh, associate), represented the achievement of years of struggle by San Francisco music lovers for an opera house of their own. It was opened on October 15, 1932 with Lily Pons singing Tosca. The auditorium, seating 3,285 persons, is richly decorated. The floor of the orchestra pit can be raised and lowered. The stage is 131 feet wide, 83 feet deep, and 120 feet from floor to roof. At the 30-foot-long switchboard, all the lighting combinations required for an entire performance can be set in advance and released in proper order by the throwing of a single switch.

6. Beyond massive gilt-trimmed iron fences stretch the green lawns of MEMORIAL COURT, separating the Opera House and the Veterans’ Building. Severely formal, it was designed by Thomas Church with planting in long fiat masses to conform to its architectural setting.

7. The four-story VETERANS’ BUILDING (open 8 a.m. to indefinite hour), SW. corner Van Ness Ave. and McAllister St., houses over 100 veterans’ organizations. From the vestibule on the main floor of the building (Arthur Brown, Jr., architect), a long, columned Trophy Gallery with cast stone walls, vaulted ceiling, and marble floor leads to the Souvenir Gallery. Here the coffered ceiling and stone walls give quiet sanctuary to a display of military medals and Souvenirs. Over a granite cenotaph with a bronze urn containing earth from four American cemeteries in France, a light burns perpetually. In the auditorium, seating 1,106 persons, arched panels between the pilasters of the side walls contain eight murals by Frank Brangwyn depicting earth, air, fire, and water. The maple floor can be tilted to afford a clear view of the stage or levelled into a dance floor. On the second floor is the genealogical library of the Sons of the American Revolution. The corridors on both second and third floors are lined with meeting and lodge rooms.

The 13 galleries of the SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF ART (open weekdays 12 m.-10 p.m.; Sun. 1-5), on the fourth floor, are gained by elevator from the McAllister Street side. The permanent collection of painting and sculpture is predominantly the work of modern artists including Van Gogh, Cézanne, Matisse, Hofer, Bracque, Roualt, and Picasso. The Diego Rivera collection, not on display at present (1940), is one of the most important in the United States. There are frequent loan exhibits of the work of contemporary artists. Here also are an art library and lecture room. The San Francisco Art Association opened the museum in 1935 with Dr. Grace McCann Morley as director.

8. The STATE BUILDING ANNEX, 515 Van Ness Ave., a six-story building, houses offices of the California Nautical School; of several divisions of the Departments of Education and of Industrial Relations; and of the Department of Professional and Vocational Standards. Here also is the Hastings College of Law (University of California), founded and endowed in 1878 by Serrano Clinton Hastings, first Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court.

9. In two-story PIONEER HALL, 456 McAllister St. (open Mon.-Fri. 10-4; Sat. 10-12), occupied jointly since June, 1938 by the Society of California Pioneers and the California Historical Society, an exhibit of firearms, mining implements, and poker chips keeps alive memories of the days of ‘49. The Society of California Pioneers, founded in 1850, limits its membership to direct descendants of the early settlers. The California Historical Society, founded in 1852, publishes books, pamphlets, and a quarterly on Western history. The two Organization maintain libraries of some 40,000 volumes and own many manuscripts, documents, and historic prints and illustrations concerning California.

10. The block-long, five-story granite STATE BUILDING, McAllister, Polk, and Larkin Sts., in the Italian Renaissance style, was built in 1926 at a cost of $1,800,000. It houses offices of the Governor and Attorney General and other divisions of the State government.

11. A ragged Senate of unemployed philosophers gathers daily along the “wailing wall’ by the south entrance of the SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC LIBRARY, Fulton, Larkin, and McAllister Sts. (open weekdays 9 a.m.-10 p.m.; Sun. 1:30-5 p.m.). Around the corner, Leo Lentelli's imperturbable heroic-size statues symbolizing Art, Literature, Philosophy, Science, and Law, posed between Ionic columns, wear a calmer mien. Across the granite facade are carved the words: “May this structure, throned on imperishable books, be maintained and cherished from generation to generation for the improvement and delight of mankind.” The 140,000 books on which the library was “throned” in 1906, however, were unfortunately no more imperishable than was the old City Hall's McAllister Street wing, in whose wreckage they were destroyed. For the design of its new home, the architect, George W. Kelham, selected Italian Renaissance as “seeming best to represent the scholarly atmosphere which a library should attempt to convey.” Ground was broken fn March, 1915 and dedication ceremonies held February 15, 1917. Of the $1,152,000 expended on construction and equipment, $375,000 was contributed by Andrew Carnegie (he contributed a like amount for construction of branch library buildings).

The board of trustees who organized the library in 1878 boasted among its 11 members Andrew S. Hallidie (inventor of the cable car) and at least one renowned writer—Henry George, author of Progress and Poverty. With an appropriation of $24,000 from the Board of Supervisors, the trustees bought 6,000 books, installed them in a rented hall, and invited the public to come and read (but not to borrow) them. The library opened its doors June 7, 1879. During the third fiscal year, when books were first circulated, 10,500 persons held cards. The number had almost tripled by the eve of the library's destruction in the wreckage of the City Hall, where it had been installed in 1888. With about 25,000 volumes, returned from homes and branches after the disaster, it continued Operations in temporary quarters. The library's collection had grown by 1940 to 520,000 volumes, the number of card holders to 140,000, and the annual circulation to more than 4,000,000. Besides the main library, the system includes 21 branch libraries and 5 deposit stations.

From the main entrance vestibule, where a bronze bust of Edward Robeson Taylor, who was both poet and mayor (1907-10), Stands in an alcove, a corridor leads to the exhibit hall, juvenile rooms, and news-paper room along the south side of the building. A monumental staircase rises to the high-ceilinged delivery room, on the second floor, finished—like both the entrance vestibule and the staircase—in soft beige-colored Roman travertine and an imitation travertine made locally. The main reading room, opening from it, extends along the south side, leading to the Max John Kuhl Memorial Room. Above the desk in the reading room is Pioneers Arriving in the West, one of two large murals by Frank Vincent Du Mond painted for the Panama-Pacffic International Exposition. From the head of the staircase, colonnaded galleries—on whose walls are Gottardo Piazzoni's murals of the California landscape, in low-keyed blues and browns—lead to the reference room and art library along the west front. Both the reading and the reference rooms are finished with cork-tiled flooring, dark oak wood-work, and painted beam ceilings. On the east wall of the reference room is Du Mond's mural, Pioneers Leaving the East. On the third floor are the periodical room, music library, assembly room, patent room, secretary's office, and Phelan Memorial Room. Along the north side of the building are the Stacks.

The library's collection is notable chiefly in the fields of music, fine arts, costume, and world literature. The music library, containing 7,400 volumes of music, 8,000 pieces of sheet music, and 5,000 pictures, is one of the largest in the United States. In the Max John Kuhl Memorial Collection of examples of fine printing and bookbinding are books from the presses of such San Francisco typographical artists as Helen Gentry, John Henry Nash, and Edwin Grabhorn. The collection includes a Kelmscott Chaucer, an Asbendene Spenser, and a Dove's Press English Bible, The collection of Californiana, housed in a room made possible by James D. Phelan, who willed $10,000 for establishment of the Phelan Memorial Room, contains manuscripts, autographs, and first editions of California authors including Bret Harte, Mark Twain, Joaquin Miller, Ina Coolbrith, Ambrose Bierce, Jack London, George Sterling, and Gertrude Atherton.

On condition that they never be removed from San Francisco, the heirs of Adolph Sutro—San Francisco mining engineer, philanthropist, and one-time mayor—presented in 1913 to the State from his private library 70,000 volumes which escaped the fire of 1906. This collection, now in the SUTRO BRANCH OF THE CALIFORNIA STATE LIBRARY (loan desk and catalogue N. end of reference room) is open to qualified scholars. It includes 45 of the 3,000 incunabula in the original collection, among which are the letters of St. Jerome printed by Peter Schoeffer in 1470. In the collection of many thousand Spanish and Mexican books are a compilation of Mexican laws published in 1548 and 42 volumes hearing American imprints of the seventeenth Century. There are copies of the first, second, third, and fourth folios of Shakespeare and first and second folios of Ben Jonson. The religious works include the prayer books of James I and Charles II and a Bible used by Father Junipero Serra. Well-known to Hebrew scholars is the collection of Hebrew manuscripts obtained in Jerusalem, at least one of which—a 90-foot scroll, probably of sheepskin—is attributed to Maimonides. The library also owns a notable collection of pamphlets on biographical, political, and religious subjects—Latin, German, Mexican, Spanish, and English—of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, including the thousands of English pamphlets, documents, and parliamentary Journals collected by Lord Macaulay in writing his history of England.

12. Women air their babies and exercise their dogs, schoolboys play football, and down-and-outers snatch a bit of sun and sleep on MARSHALL SQUARE, Grove, Larkin, Hyde, and Fulton Sts., named for James W. Marshall, discoverer of gold in California. The last of the coffins was removed from the sandy graves of the old cemetery here in 1870. During the following decade the “sand lots” were the meeting place for gatherings addressed by fakirs, phrenologists, and socialists. Unemployed workmen applauded the harangues of an Irish drayman with shouts of “The Chinese must go—Dennis Kearney tells us so!” Sixty years later, in the depression of the 1930’s, the unemployed met here again in great mass meetings.

13. The PIONEER MONUMENT, Grove, Hyde, and Market Sts., keeps alive the memory of James Lick, who carne to San Francisco in 1847 and died a multimillionaire in 1876. He left the city a bequest of $3,000,000, of which his will earmarked $100,000 for “statuary emblematic of the significant epochs in the history of California…” The Pioneer Monument (Frank Happersberger, sculptor), whose cornerstone was laid September 10, 1894, is a great central pediment upholding a bronze figure symbolizing California, with her spear and shield and bear, from whose base project four piers, each supporting subsidiary statuary: Early Days, Plenty, In ’ 49, and Commerce. The central pedestal is ornamented with four bronze bas-reliefs—depicting immigrants scaling the Sierra, traders bargaining with the Indians, Cowboys lassoing a steer, and California under the rule of the Mexicans and the Americans—and with five relief portraits of James Lick, John Charles Frémont, Francis Drake, Junipero Serra, and Johann August Sutter.

14. The grayish-white granite walls of the massive five-story, block-square FEDERAL BUILDING, Hyde, Fulton, McAllister, and Leavenworth Sts. (open 8-5 Mon.-Fri.; 8-1 Sat.), newest of the Civic Center group, was completed in 1936 at a cost of $3,000,000 (Arthur Brown, Jr., architect). Its 422 rooms house approximately 1,275 employees of 33 divisions of the Federal government.

15. Situated just outside the orbit of the Civic Center, the weathered four-story UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE AND POSTOFFICE BUILDING (open 6 a.m.-12 p.m.), NE. corner Seventh and Mission Sts., glittered in new white granite grandeur late in 1905. The building on its foundation of piling withstood the earthquake and fire of the following year, but the sidewalk and Street—built over the bed of a former stream—sank several feet, and the building now obviously Stands higher than the original sidewalk level. Having withstood the flames, it was easily refurbished. The building, designed in Italian Renaissance style by James Knox Taylor, cost $2,500,000, to which $450,000 was added for improvements after 1906. (In 1933 a $750,000 annex was added.) After Congress had appropriated the original funds, the price of steel dropped sharply below original estimates and in the absence of any law providing for its return to the Treasury, the surplus was spent in lavish interior decorations. Not only were Carrara, Pavonezza, Sienna, and Numidian marble imported but skilled Italian artisans were imported with them to install the verd antique trimmings of the corridors, the elaborate mosaics of the columns and vaulted ceilings. The court Chambers were panelled in California curly redwood, Mexican Prima Vera mahogany, antique oak, and East Indian mahogany, and immense ornate fireplaces (which never have been used) were installed.

San Francisco's central post office, with its financial and executive offices, occupies the first floor. On the second floor are the offices of the Railway and Air Mail Services; district chief clerks of the third and fourth post office districts and Superintendent of the eighth division; and Post Office Inspector in Charge, whose department includes Arizona, California, and Nevada; Hawaii, Guam, and Samoa.

The United States Circuit Court of Appeals, on the third floor, has the widest territorial Jurisdiction of any circuit court in the Nation, hearing cases from Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington, from Alaska and Hawaii, and from the United State extraterritorial court in Shanghai. Here also are the Chambers of the United States District Courts and the offices of divisions of the Department of Justice, of the Mineral Production and Economics Division of the Bureau of Mines, and of the Naturalization Service.

A far cry from these splendid marble corridors was the city's first post office, the frame building housing C. L. Ross and Company's New York Store at Washington and Montgomery Streets, where in April, 1849 postmaster John White Geary removed a pane of glass from the front window and began dealing out the 5,000 letters he had brought with him on the Oregon. Following the arrival of the fortnightly mail steamer from Panama, wrote the British traveler, J. D. Borthwick, in 1851, “a dense crowd of people collected, almost blocking up the two streets which gave access to the post-office…. Smoking and chewing tobacco were great aids in passing the time, and many carne provided with books and newspapers.… A man's place in the line…like any other piece of property…was bought and sold… Ten or fifteen dollars were frequently paid for a good position… There was one window devoted exclusively to the use of foreigners…and here a polyglot individual…answered the demands of all European nations, and held communication with Chinamen, Sandwich Islanders, and all the stray specimens of humanity from unknown parts of the earth.”

“Steamer Day,” the beginning and middle of each month, which brought not only the mail but also the Eastern papers—only source of news of the outside world—became a San Francisco Institution. For a week the population prepared its letters and its gold dust—of which millions of dollars’ worth were shipped East—for the fortnightly out-going steamer. Even after 1858, when the Overland Stage Line to St. Louis began carrying eight mails each month and the Pony Express to St. Joseph two a week, the custom continued, and business men paid their accounts on Steamer Day. Not until the 1880’s did the custom end.