Metropolitan Scene

“There are just three big cities in the United States that are ‘story cities’—New York, of course, New Orleans, and best of the lot San Francisco.”

—FRANK NORRIS

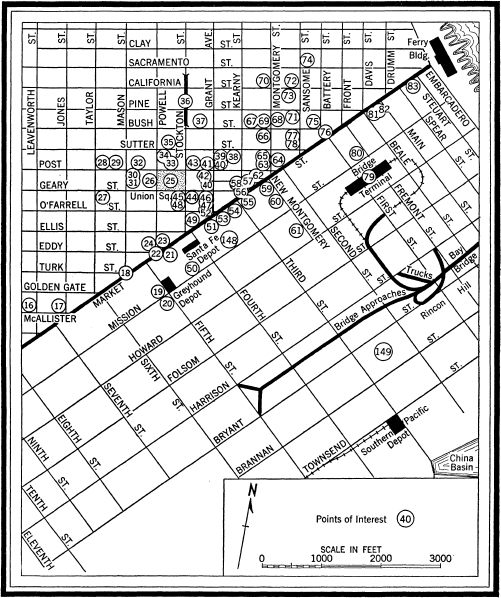

TIMES SQUARE and Picadilly Circus recall the metropolitan grandeur of New York and London. Although San Francisco has no single spectacular landmark by which the world may identify it, the greatest cities have long since welcomed it into their company. Portsmouth Square, the Palace Hotel, and the Ferry Building, which served successively as symbols of civic vanity, no longer resound with much more public clamor than many another plaza, hostelry, or terminal. Only Market Street accents for the casual observer San Francisco's metropolitan character.

Southwestward from the Ferry Building to Twin Peaks Tunnel, Market Street's wide, unswerving diagonal bisects the city. To Market Street, as to Rome, lead all downtown streets, converging from north, southeast, and west at wedge-shaped intersections where traffic tangles bewilderingly. Northward, where slopes rise steeply to hilltops, are shops, clubs, theaters, office buildings, luxury hotels, and apartment houses—the center of San Francisco's commercial activities and vortex of its social whirl. Southward—in what is still “South of the Slot” to old-timers—abruptly begin the row upon row of pawn shops, flyspecked restaurants, and shabby lodginghouses that stretch over level ground to the warehouses, factories, and railroad yards along the Bay's edge.

Jasper O'Farrell's survey, a Century ago, laid the foundation for Market Street's development. Long before the forty-niners paved it with planks, the tallow and hides of Peninsula ranchos rolled down its rutted trail in Mexican oxcarts to Yerba Buena Cove. Hundred-vara lots along the street's southern side were considered ideal business locations; and the width of the thoroughfare determined its future. Steam-cars, in the 1870’s and 1880’s, brought along it passengers to be deposited in frock coats and crinolines before the Palace Hotel. Before the disaster of 1906, cable cars went careening up the Street, like diminutive galleons riding on waves of basalt pavement whose sand foundation sank unevenly beneath the traffic.

A hundred and twenty feet wide, Market Street epitomizes Western spaciousness. At its upper end soar the crests of Twin Peaks, green with grass in spring. Flooded with sunlight on clear days, it contrasts sharply with the dingy canyons of neighboring streets devised for shopping and finance. After dark, gleaming with neon fluorescence of lighted signboards, it is a broad white way. Thanks to the fire of 1906, which piled the thoroughfare high with debris of baroque monstrosities, its contours are obstructed by few grotesque domes and fantastic facades, once the pride of the bonanza generation. With its streamlined array of neon signs, movie-theater marquees, neat awnings, and gleaming windowglass, Market Street's predominant tone is one of settled progress housed in masonry and concrete.

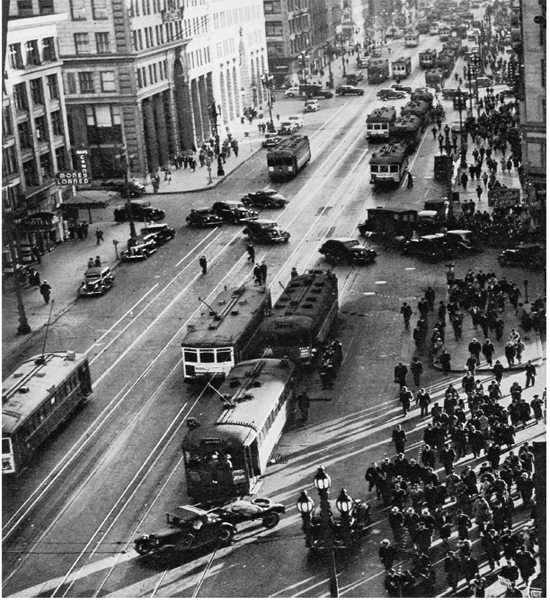

To millions of visitors who have ventured through the portals of the Ferry Building at its southern end to set foot for the first time in the city of St. Francis, Market Street must have seemed a little frightening. After a cairn leisurely ferryboat voyage from the main railroad terminals across the Bay, the visitor plunged into what was obviously a traffic engineer's nightmare. A huge three-track trolley loop—encircling a forlorn plot of bush and grass—routes a succession of clanging electric juggernauts past the Ferry Building and back up Market Street. Unfortunately for streetcar riders, Market Street is wide enough to accommodate four tracks—a pair for each of the city's two Systems. Boarding cars which ride the inner pair cells for a dauntlessness peculiar to San Francisco pedestrians. When two cars come thundering abreast down the tracks, the cautious commuter waits for both to stop, then darts around the back of the outside car to board the inside one; but hardier souls take a firm stand in the narrow gap between tracks, breathing in as two cars roar by on either side. Market Street at five o'clock on a workday afternoon is a deafening concourse of streetcars plunging through swirling eddies of pedestrians, passengers bulging from doors and agile youths swarming over rear fenders.

Along both its upper and lower reaches, Market Street has little of that dynamic tempo which marks its middle stretch. The first few blocks southwest of the Ferry Building pass between low buildings—railroad and steamship offices, nautical supply stores, transient hotels—before skyscrapers begin flinging lofty heads heavenward. Beyond the reach of shoppers, this section is never crowded; late at night, it is gloomy and deserted except for an occasional streetcar, a lone roisterer, or a solitary patrolman. Where it skirts the Civic Center on its southwestward route, the solid phalanx of office buildings, theaters and stores begins to show gaps, thinning into strings of paint stores, second-hand book shops, and parking lots, until the black mouth of Twin Peaks Tunnel swallows the streetcar tracks. That Market Street along whose broad sidewalks moves the informal pageant of San Franciscans on parade comprises nine blocks between Hyde Street on the west and Montgomery Street on the east.

The windswept corner at Powell and Market begins a gay, devil-may-care Street that has for better than half a Century fascinated and delighted both native and visitor. Unlike the tiny slow cable cars that clang up and down the Powell Street hill to be reversed on the turn-table at Market Street, life always has run fast and a little loose along this narrow urban canyon. On the east corner of Powell and Market stood the Baldwin Theater, housed within a hideously ornate hotel of the period. Around the corner on Eddy Street was the Tivoli Theater, where patrons sat at tables and ate and sipped refreshments while watching the performance. Although the fire of 1906 razed the entire area, Powell Street and environs maintained their reputation by immediately rebuilding. The district became known as the “Up-town Tenderloin.” Until the Eighteenth Amendment relegated pleasure spots to back rooms, it was replete with lively restaurants, saloons, and cabarets—whose names make older residents yearn for the “good old days.” Techau Tavern stood on the site of the present bank at the southwest corner of Powell and Eddy; the Portola Louvre, across the Street. Around the corner at 35 Ellis Street was the Heidleberg Inn, and at 168 O'Farrell Street, the famous old Tait-Zinkand cabaret, across from the Orpheum Theater where vaudeville was born. Fabulous Tessie Wall kept her red plush and gilt bagnio on the southwest corner of Powell and O'Farrell Streets—Tessie Wall, who reigned before Prohibition as “Queen of the Tenderloin,” whose answer to her husband, gambler Frank Daroux, when he asked her to move to a suburban home in San Mateo is still quoted: “San Mateo! Why I'd rather be an electric light pole on Powell Street than own all of the county.” Mason Street, one block west of Powell, was the “White Way,” sparkling with the lights of Kelly's place, Jimmy Stacks’ cabaret, the later Poodle Dog, and Billy Lyons’ saloon, “the Bucket of Blood.”

Powell Street, now relieved of suggested rowdiness by smart hotels, shops, and bars, has outlived its past. The hilarious uptown tenderloin which rivalled the Barbary Coast has receded to streets immediately west. This newer, downtown tenderloin is a district of subdued gaiety that awakens at nightfall—a region of apartment houses and hotels, corner groceries and restaurants, small night clubs and bars, gambling lofts, bookmakers’ hideouts, and other fleshpots of the unparticular. Techau's, the dine-and-dance place renowned for “an appearance of Saturnalia,” is today the name of an ultra-modern cocktail bar at another Powell Street address. The old Portola-Louvre at Powell and Market—described as “that which takes the rest out of restaurant and puts the din in dinner”—is now a quiet Cafeteria more modestly named. Whatever remains of the great tradition of such theaters as the Baldwin is preserved at the city's only two legitimate houses, on Geary Street west of Powell.

Between Geary and Post Streets, where Powell Street begins its climb up Nob Hill—that climb which leads it up, up, and up to where stood gaudy mansions of the bonanza “nabobs”—the solemn gray-green stone facade of the St. Francis Hotel faces eastward over the sloping green turf and venerable palms of Union Square. Here the benches are packed the day long with successful men and failures feeding pan-handling pigeons or humming together at one of the semi-weekly WPA Music Project's noonday concerts. Clerks and nurses, salesmen and stenographers, eat their lunches on the grass. Chinese boys scurry along the paths, shouldering bootblack kits, alert for dusty shoes. Along the wrought-iron picket fence on the south side, drivers of long limousines lounge in their cars, waiting for sightseeing customers.

Union Square is the heart of that area of shops and hotels which represents to an international clientele and to San Franciscans the city's traditional demand for quality. Here department stores have for so many decades been custodians of public taste—their founders being patrons of the arts and bon vivants—that their very buildings are considered public institutions. Along Grant Avenue, Geary, Stockton, Post, and O'Farrell Streets, the gleaming Windows of perfume and jewelry shops, travel bureaus, art goods and book stores, apparel and furniture shops entice throngs of shoppers. Near these stores flower-vendors have the sidewalk Stands so dear to San Franciscans. Along Sutter Street are offered rugs from India and Afghanistan, books, art objects from Europe and the Orient, household fixtures and antiques. Here San Franciscans pay gas bills and see dentists, and here are the commercial art galleries.

Kearny Street is the shopping district's eastern boundary. At its wide, windy intersection with Market Street the new San Francisco meets the old. Glowering down upon Lotta's Fountain Stands the ungainly red-brick De Young Building (San Francisco's first “skyscraper”), and facing it across the intersection is the modernized tower of the old Spreckels Building. “Cape Horn” the city's rounders dubbed this breezy crossing, back in the era of free lunches and beer for the common run and champagne for the elite. Here lounged young wastrels whose delight it was to observe the skirts of passing damsels wafted knee-high by sudden gusts.

“All bluffs are called on Kearny Street,” wrote Gelett Burgess. Running north from Market Street to the Barbary Coast, it was an avenue of honky-tonks and saloons frequented by racetrack tipsters and other shady Professionals. On election nights it was the scene of torchlight parades and brass bands. Of early theaters, the Bush, the Standard, and the California were situated near Bush and Kearny Streets. Among the restaurants that gave San Francisco a name were the Maison Dorée on Kearny between Bush and Sutter Streets, the Maison Rich, a block west at Grant Avenue and Geary Streets, the Poodle Dog at Grant Avenue and Bush Street, and Tortoni's, two blocks west at O'Farrell and Stockton Streets. All served French dinners that were gastronomical delights to a city that always has known how to eat. Another famous restaurant was Marchand's, at Grant Avenue and a little two-block alley called Maiden Lane. Now chaste and obscure, Maiden Lane has been renamed a half-dozen times, but the original name sticks, inducing a wry smile from old-timers who remember when its “maidens” were ladies of little or no virtue.

The inglorious past is slipping fast from Kearny Street. Streamlined clothing establishments for men, smart shops, and cocktail bars are marching northward against the tawdry remains of an era of architectural horror and moral obliquity. Its awakening comes late but it comes with a vengeance. A few blocks northward its businesses and buildings decline in class and size to pawnshops, bailbond offices, and the hangouts of dapper, black-haired Filipinos.

Not even the most farseeing mind could have imagined, in San Francisco's toddling days, the narrow canyon between skyscrapers that is present-day Montgomery Street. Being then the water front, it was the city's doorstep to the world. The doorstep was gradually moved eastward as filled-in land pushed back the Bay waters, but San Francisco went on doing business in the original location. Into Montgomery—and later Kearny Street, one block west—were compressed most of what the city possessed—banks, customhouse, post office, business houses, newspaper offices, dance and gambling halls, theaters, livery stables, saloons, and restaurants. The streets were ungraded. Kearny was paved with sticks and stones, bits of tin, and old hatch coverings from ships that had tramped the world. The going was difficult, if not downright dangerous, for both pedestrian and rider. In 1849 the site of the Palace Hotel's present magnificence, across from the southern end of Montgomery Street, was Happy Valley—host to a tent settlement of poor immigrants. Market Street was a dream in the brain of young Jasper O'Farrell, who was to engineer San Francisco's Street design.

Montgomery Street has thrown off its old boisterous and willful ways. Neat and austere between sheer walls of stone, glass, and terra cotta, it is visible evidence of San Francisco's financial hegemony over the far West. But the past that dies hard in San Francisco still lingers on. Old-fashioned and with clanging bell, the cable cars go lurching through the cross streets that intersect Montgomery, past insurance companies and foreign consulates. All day the street's great office structures are beehives, humming with business; its sidewalks are populated with businessmen carrying briefcases, and lined with parked shiny automobiles. But at dark, when the skyscrapers are deserted but for their watchmen and scrubwomen, the deep canyons are black and silent, and the clank of cables, pulling their freight uphill toward the lighted hotels and apartment houses atop Nob Hill, echoes in the stillness.

POINTS OF INTEREST

16. Looming over the Civic Center and uptown San Francisco, the soaring shaft of the 28-story HOTEL EMPIRE, NW. corner Leavenworth and McAllister Sts., embodies the spirit of a new era rising from the old, like the Phoenix of the municipal seal. Built through the united efforts of the city's Methodist churches, it was opened in the late 1920’s as the William Taylor Church and Hotel, named for the noted Street preacher of the 1850’s, since it housed a built-in Methodist Church.

17. Founded a decade after ‘49 by John Sullivan, the HIBERNIA SAVINGS AND LOAN SOCIETY (open 10-3), NW. corner McAllister and Jones Sts., has survived eight decades of prosperity and panic to become one of San Francisco's oldest banks. Its classic, one-story building (Albert Pissis, architect)—whose granite facades were gleaming white when finished in 1892 but have been weathered to a dull gray—survived even the fire of 1906. It is topped by a gilded dome surmounting the Corinthian colonnade which rises at the head of the curved granite steps of the corner entrance. Inside, marble pilasters spring from a floor inlaid with mosaic to represent a mariner's compass card.

18. The bronze angel atop the NATIVE SONS MONUMENT, Market, Turk, and Mason Sts., holds aloft a book inscribed with the date of California's admission to the Union: September 9, 1850. Beside the granite shaft a youthful miner shouldering a pick, armed with the holstered six-shooter of his day, waves an American flag. Gift of James D. Phelan, the monument (Douglas Tilden, sculptor) was unveiled on Admission Day, 1897.

19. The austere UNITED STATES BRANCH MINT (not open), NW. corner Fifth and Mission Sts., now houses temporary offices of various departments of the Federal government. Its basement walls of Rocklin granite and upper facades of mottled British Columbia bluestone, its pyramidal flight of granite steps climbing to a portico of Doric columns are blackened with grime. Built in 1870-73 to sup-plant the first branch mint, established in 1854 on Commercial Street, the $2,000,000 structure (A, B. Mullett, architect) was itself sup-planted in 1937 by a still newer mint. In 1906, while flames gnawed at its barred and iron-shuttered windows, mint employees aided by soldiers fought a seven-hour battle with a one-inch fire hose and saved $200,000,000 from destruction. One-third of the Nation's entire gold reserve was housed here in 1934.

20. “Industrial Gothic” is the three-story CHRONICLE BUILDING (visitors shown through plant by appointment), SW. corner Fifth and Mission Sts., with tall arched windows and high corner clock tower. A morning paper with a circulation of approximately 110,000, the Chronicle issues five regular editions daily, the first appearing on the streets at about half past seven o'clock in the evening.

21. On the highest assessed piece of land in the city is San Francisco's largest department store, THE EMPORIUM (open 9:45-5:25), 835 Market St. The massive, gray sandstone facade, its three arched entrances opening onto a quarter-block-long arcade, is ornamented with columns in half-relief rising from the fourth-story level to the balustrade at the roof edge. Inside, an immense glass-domed rotunda, 110 feet in diameter and 110 feet high, ringed by a pillared gallery, rises through four stories to the roof garden. Its present building, replacing one built in 1896 and destroyed by the 1906 fire, Stands on the site of St. Ignatius College, now the University of San Francisco.

22. Traffic waits goodnaturedly at the CABLE CAR TURNTABLE, Market, Powell, and Eddy Sts., where a careening southbound car comes to a halt every few minutes, while conductor and grip man dismount and push the car around until it faces north.

23. Traces of discoloration in the sandstone near the entrances of the FLOOD BUILDING, NE. corner Market and Powell Sts., recall the earthquake and fire of 1906, which broke windows and blackened the walls of the structure a year after its completion. Named for bonanza king James C. Flood, the building Stands on the site of the Baldwin Hotel and Theater, built by his contemporary, E. J. (“Lucky”) Baldwin in 1876-77 and destroyed by fire in 1898. Of gray sandstone, the 12-story structure is wedge-shaped to fit the site, its two facades converging in a rounded corner ornamented with columns in half-relief.

24. Head office of the Nation's fourth largest bank is the BANK OF AMERICA (open Mon.-Fri. 10-3, Sat. 10-12), NW. corner Market and Powell Sts., whose resources topped $1,500,000,000 at the end of 1939. “Statewide Organization, Worldwide scope” is the motto carved beneath Giovanni Portanova's bas-relief, personifying the bank as a female figure enthroned between a Mercury (commerce) and a Ceres (agriculture), above the corner entrance. The seven-story structure, faced with white granite and decorated with Corinthian pilasters, was erected in 1920.

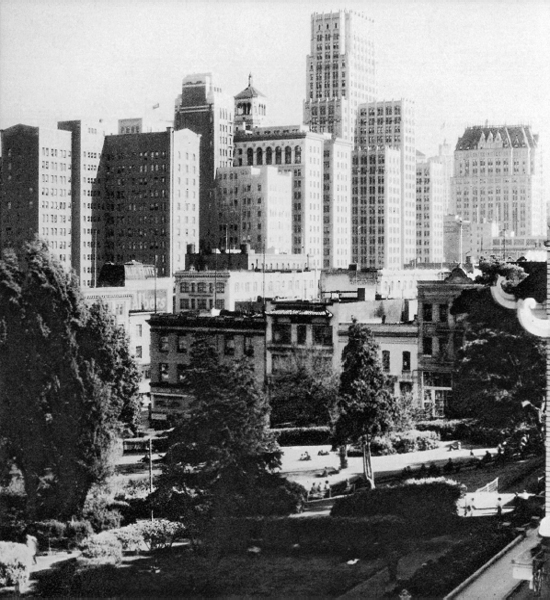

25. A grassy haven in the midst of the downtown bustle, UNION SQUARE, Powell, Geary, Post, and Stockton Sts., spreads 2.6 acres of green lawns around the 97-foot-high granite shaft of the NAVAL MONUMENT (Robert Ingersoll Aitken, sculptor), whose bronze female Victory, armed with wreath and trident, commemorates “the Victory of the American Navy under Commodore George Dewey at Manila Bay, May First, MDCCCXCVIII.” President William McKinley broke ground for the monument in 1901 and President Theodore Roosevelt dedicated it in 1903. Union Square was presented to the city in 1850 by Mayor John White Geary. Mass meetings held here on the eve of the Civil War by Northerners demonstrating their loyalty to the Union gave the Square its name.

DOWNTOWN SAN FRANCISCO

26. The ST. FRANCIS HOTEL, Powell, Geary, and Post Sts., is the 14-story, block-long, steel-and-concrete successor to the hotel opened here in 1904 and razed in 1906. The building (Bliss and Faville, architects), is an adaption of the Italian Renaissance style to the modern skyscraper. Its main facade, weathered a somber gray, has three wings, the central one flanked above the second story by deep open courts separating it from the others. The spacious lobby with vaulted ceiling and Corinthian columns is one of the city's most popular meeting places. Near the entrance to the Mural Room, under the great Austrian clock which controls 50 smaller clocks throughout the building, under-graduates from Stanford and the University of California—who sometimes refer to the hotel as “The Frantic”—have kept appointments for three decades. In the Mural Room (named for Albert Herter's seven murals, The Gifts of the Old World to the New), whose black columns, mirrored walls, and blue and gold ceiling provide a pleasant setting, socialites have met for two decades to dine, dance, and attend Monday luncheons and fashion reviews. Occupying an entire wall of the largest of the hotel's banquet and meeting rooms, the Colonial Ballroom, is Albert Herter's mural portraying American Colonial life.

On the second floor are the headquarters and library of the COMMONWEALTH CLUB (open to members and certified students Mon.-Fri. 9-5 Sat. 8:30-12), founded in 1903 by Edward F. Adams of the Chronicle. The club's motto is “Get the Facts”—and it maintains a permanent fund of $270,000 for research in subjects of public interest. More than 1,500 distinguished visitors have addressed the club during its career.

27. The modern 17-story white-brick and stone CLIFT HOTEL, 495 Geary St., was opened in 1915 by attorney Frederick Clift. Three new stories and an additional wing were added in 1926. Lobbies and public rooms are combined Spanish and Italian Renaissance with high beamed ceilings. The Redwood Room is panelled with highly burnished 2,000-year-old California redwood and its 30-foot bar is made entirely of redwood burl.

28. “Weaving spiders come not here” admonishes an inscription over the Taylor Street entrance of the five-story red brick Italian Renaissance home of the BOHEMIAN CLUB (private), NE. corner Post and Taylor Sts., erected in 1934. Across J. J. Mora's bronze bas-relief on the Post Street facade troop a procession of Bret Harte's characters. The club grew in 1872 from informal Sunday breakfasts at the home of James Bowman, editorial writer on the Chronicle. Artist friends sketched so freely on Mrs. Bowman's tablecloths her husband decided that San Francisco intellectuals needed an official club.

For the first few years, quarters were shared with another club, The Jolly Corks. The atmosphere was casual, the furnishings meager. Members who complained of the lack of tables and chairs were reminded that “when a man gets tired of holding his drink all he has to do is to swallow it.” The club's monthly “High Jinks”—their name derived supposedly from Sir Walter Scott's Guy Mannering—were debates followed by suppers. The more or less serious “High Jinks” (later burlesqued by “Low Jinks”) were sometimes exciting occasions. The story persists that one speaker opened his manuscript to show a wicked-looking revolver, which he placed on the table in front of him, saying: “This is to shoot the first Bohemian galoot who stirs from his seat before I end this paper.” In 1877 the Bohemians moved into quarters of their own on Pine Street. Among the honorary members elected to the club have been Mark Twain, Bret Harte, and Oliver Wendell Holmes.

The Bohemian Club now has a world-wide membership of about 2,000 and a waiting list of hundreds. Once a year they come together for a midsummer frolic in the club's Bohemian Grove, where an original play has been produced since 1880, when the first Midsummer Jinks—an open-air picnic accompanied by speeches and celebrations—was held.

29. The winged “O” of the OLYMPIC CLUB (private), 524 Post St., oldest amateur athletic Organization in the United States, has been worn by many star athletes, including “Gentleman Jim” Corbett, the San Francisco bank clerk who became world's heavyweight champion after practice as the club's boxing instructor, and Sid Cavill, one of a famous family of Australian swimmers, who introduced the Australian crawl to America as the club's swimming instructor. Nucleus of the Olympic Club, formed May 6, 1860, was the group which Charles and Arthur Nahl invited to use the gymnastic apparatus they had assembled in their Taylor Street backyard. The Organization now has 5,000 members. The five-story brick clubhouse is equipped with a gymnasium, a solarium, squash and handball courts, an indoor track, a billiard room, a marble plunge piped with ocean water, dining halls, a library, and a lounge.

30. The Corinthian - pillared FIRST CONGREGATIONAL METHODIST TEMPLE, SE. corner Mason and Post Sts., was founded in 1849 in the schoolhouse on the Plaza, led by a missionary from Hawaii, the Reverend T. Dwight Hunt. Having outgrown the frame structure built at Jackson and Virginia Streets in 1850, the congregation spent $57,000 raised largely by pew rentals on a structure at Dupont (Grant Avenue) and California Streets. In 1872 it moved into a tall-spired red brick Gothic Church on the present site, and in 1915 into the present building; here it was joined in 1937 by the Temple Methodist Church, which gave up its William Taylor Church.

31. The eight-story red brick and buff tile NATIVE SONS OF THE GOLDEN WEST BUILDING (open daily 7 a.m.-12 p.m.), 414-30 Mason St., houses an Organization founded in 1875. J. J. Mora's terra cotta bas-reliefs between the upper windows depict epochs in pioneer history. Above the entrance are bas-relief portraits of Junipero Serra, John Charles Frémont, and John D. Sloat. Around the balcony of the auditorium, which seats 1,250, are intaglios portraying California writers.

The (fourth-floor) FRENCH LIBRARY (open 1-6, 7-9; fee, 50¢ monthly), conducted by L'Alliance Française, the largest French library in the United States, contains 21,000 volumes. It was founded in 1874 as the Bibliothèque de la Ligue National Française, under the patronage of Raphael Weill, through the efforts of a society of French residents formed after 1871 to protest appropriation of Alsace and Lorraine by Germany.

32. Against the dark panelling of the JOHN HOWELL BOOK SHOP (open 9-5:30), 434 Post St., gleam the rich colors of the rare old volumes which line the walls. The collection is especially rich in early Californiana and Elizabethan literature. Beyond the main room, a large studio displays the West's largest collection of rare Bibles. It includes a Venetian Latin Bible printed in 1478; the Bible printed by John Pruss at Strassburg in 1486, one of four in America; one of the nine copies of the first issue of the Martin Luther Bible, printed at Wittenberg in 1540-41; the Great “She” Bible of 1611; and the family Bible of Sir Walter Scott, hand-ruled in red. Also displayed is the first American edition of the Koran, printed in 1806. On the wall is a rare parchment containing 24 panels painted by a Buddhist priest which depict the story of Buddhist worship.

33. NEWBEGIN'S BOOK SHOP (open 8:30-6), 358 Post St., was founded in 1889 by John J. Newbegin, friend of Ambrose Bierce, Ina Coolbrith, Jack London, and George Sterling. Mr. Newbegin is an authority on rare books; his collection of material dealing with shipping is said to be the world's largest.

34. The vertical lines of the 22-story SIR FRANCIS DRAKE HOTEL, 450 Powell St., culminate in a six-story, set-back tower overlooking city and Bay. The structure (Weeks and Day, architects) was completed in 1928. Four great panels by local muralist S. W. Bergman, depicting the Visit of Sir Francis Drake to the Marin shores, decorate the English Renaissance lobby. Name bands play nightly in the Persian Room, whose low illuminated ceiling plays changing lights on the Persian murals of A. B. Heinsbergen.

35. Looming in monumental grandeur above the business district, the FOUR-FIFTY SUTTER BUILDING, 450 Sutter St., rises—a massive shaft with rounded corners, faced in fawn-colored stone—25 stories above the Street. A striking adaptation of Mayan motifs to functional design, the structure (Timothy L. Pflueger, architect), completed in 1930, required more than two years and $4,000,000 to build. Its wide entrance, topped by a four-story grilled window in a tree-like Mayan design, is in nice proportion to the facade's severe lines. Large Windows, flush with the exterior, flood the offices with light—especially the corner suites, which have six bay windows. The building provides its tenants—doctors, dentists, pharmacists, laboratory technicians, and others of allied professions—with a solarium, a doctors’ lounge, and a 1,000-car garage.

36. December, 1914 saw completion of the $656,000 STOCKTON STREET TUNNEL (Michael O'Shaughnessy, engineer), boring 911 feet through Nob Hill from Bush almost to Sacramento Street to connect downtown San Francisco with Chinatown and North Beach. The tunnel is 36 feet wide and 19 feet high; sodium vapor lights were in-stalled in 1939.

37. NOTRE DAME DES VICTOIRES (Our Lady of Victories), 566 Bush St., serves San Francisco's French colony. The church, completed in 1913, is of Byzantine and French Renaissance architecture, constructed of brick with groined twin towers and high arched stained-glass windows.

38. Since 23-year-old Leander S. Sherman in 1870 bought the shop where he had been employed to repair music boxes, SHERMAN, CLAY AND COMPANY, SW. corner Kearny and Sutter Sts., has ministered to the city's musical wants. Since the 1870’s, the firm—known as Sherman, Hyde, and Company until Major C. C. Clay bought out F. A. Hyde's original interest—has been selling music lovers their supplies and tickets to concerts and recitals.

39. Ici on parle Francais (French spoken here) was the legend which Messrs. Davidson and Lane, founders of THE WHITE HOUSE (open 9:45-5:25), Grant Ave., Sutter, and Post Sts., hung in the window of their small shop on the water front when they hired 18-year-old Raphael Weill as a clerk in 1854. When Richard Lane went into gold mining in 1858, young Weill took his place as partner of J. W. Davidson and Company. As San Francisco grew rich, the store began to dazzle shoppers with costly and daring Paris importations. When Raphael Weill asked one of the newspapers for a full-page advertisement, he was indignantly refused. “What does he think we're running, a signboard or a newspaper?” demanded the editor. “He gets two columns, no more!” But Weill got his full-page advertisement, the first in the history of the retail business.

When the store moved to its own three-story brick building at Kearny and Post Streets, Weill persuaded his partner to name it after the famous Maison Blanche in Paris. By 1900, when The White House was outfitting the women of the city in high-button shoes and Ostrich boas and filling homes with sofa pillows and table throws, its fame had spread up and down the Coast. The 1906 fire reduced it to a heap of ashes. Weill promptly wired New York for carloads of merchandise, which he distributed to 5,000 women. Having vowed that he would not shave until the store reopened, he let his beard grow for three months while quarters on Van Ness Avenue were prepared. When the present five-story structure, faced with white terra cotta (Albert Pissis, architect) opened March 15, 1909, it was one of the first to reopen in the old shopping section. Weill lived to see the store overflow into two adjoining buildings before his death in 1920 at the age of 84.

Philanthropist, epicure, and patron of the arts, Weill left his impress on the Organization. Employees celebrate his birthday annually and the store still closes on the birthday of Abraham Lincoln, whom he greatly admired. In the street-floor MEMORIAL OFFICE (open business hours), which Weill set aside as a place to greet his old friends, fresh flowers are still placed among the honors heaped on Weill: old photo-graphs, citations, and plaques—a little museum of old San Francisco.

40. Around the show windows of the florists’ shop of PODESTA AND BALDOCCHI (open weekdays 8-6, Sun. 8-11 a.m.), 224 Grant Ave., passersby Cluster to admire flaunting sprays of rare orchids, exquisite lilies, or rich-textured camellias, arranged with spectacular artistry among many kinds of blossoms. In the early spring, the shop is embowered in pink and white flowering branches of fruit trees; at other seasons, in great masses of trailing greenery.

41. One of the Nation's oldest jewelry establishments, SHREVE AND COMPANY (open 9-5), NW. corner Grant Ave. and Post St., have been dealing in precious stones and rare objects of gold and silver since 1852. It is the only large downtown store still operating whose advertisement appeared in the San Francisco City Directory of 1856—when its address was No. 139 Montgomery St.

42. Book and art lovers frequent PAUL ELDER AND COMPANY (open 9-5:30), 239 Post St., established in 1898. Eider not only sells current literature, rare editions, and used books in a shop whose Gothic decorative motifs were suggested by Bernard Maybeck—designer of the Palace of Fine Arts—but also presents lectures, dramatic readings, and book and art exhibits in the second-floor galleries.

43. To collectors the world over, the name of S. G. GUMP AND COMPANY (open 9:45-5:25), 250 Post St., means jade, but the firm's agents have scoured the world for more than jade. Show rooms are styled to conform with the rare objects they contain. Since Solomon and Gustave Gump founded the firm in 1865, it has grown into an institution whose buyers gather items for collectors throughout the Nation. In its show rooms are displayed modem china, pottery, glass, linens, silverware, and jewelry; silks, brocades, and velvets; Siamese and Cambodian sculpture; porcelain and cloisonné, rich-textured tapestries, bronze temple bells, hardwood screens ornamented with jade, and rugs from Chinese palaces acquired after the overthrow of the Manchu government. In the Jade Room all of the eight colors and 45 shades of the stone are represented, including the rarest, that most nearly resembling emerald; pink, so rare that only small pieces have been found; and spinach green, a dark tone flecked with black, used for large decorative pieces. The collection of tomb jade, recovered from mounds in which mandarins were interred, includes pieces 2,000 years old. The Jade Room also contains figurines carved of ivory, crystal, rose quartz, white and pink coral, rhinoceros horn, and semiprecious stones.

44. Fluctuat nec Mergitur (It floats and never sinks), Paris’ own municipal motto, has been the slogan of the CITY OF PARIS (open 9:45-5:25), SE. corner Stockton and Geary Sts., since the spring of 1850, when Felix Verdier hung up—over an edifice constructed largely of packing cases the sign:

“LA VILLE DE PARIS

Felix Verdier, Proprietor

Fluctuat nec Mergitur”

The motto was appropriate, for the contents of “La Ville de Paris” had been afloat ever since Verdier had left France in a ship whose cargo he bought with profits from his silk-stocking factory at Nimes. (A republican, he had preferred exile to the new emperor.) Destroyed several times by fire, the store moved each time to larger quarters. When Felix was succeeded, at his death in the late 186o's, by his son Gaston, it was moved into its own building at Geary Street and Grant Avenue. It came to its present location in 1896.

Twenty-four-year-old Paul Verdier had scarcely taken over in 1906 when the building was destroyed. First store in town to reopen, it resumed business in a mansion on Van Ness Avenue. The present six-story building—with its glass dome rising above balconies, its Louis XVI window frames of white enamel and carved, gilded wood—was opened in the spring of 1909. At the peak of the dome appear the original crest of Paris, a ship in full sail, and the motto. Author of A History of Wine, Paul Verdier personally selects the more than 1,000 choice vintages which stock the cellars.

45. When the NATHAN-DOHRMANN COMPANY (open 9:45-5:25), SW. corner Stockton and Geary Sts., opened in 1850 (as Blumenthal and Hirsch), it sold mining equipment. By 1886, when Bernard Nathan, manager since the founder's death, took as his partner Frederick W. Dohrmann, the firm was stocking oil lamps, basins, ewers, and shaving mugs. Still managed by descendants of Nathan and Dohrmann, it now sells wares and Utensils of all descriptions.

46. In a studio penthouse the COURVOISIER GALLERIES (open 9-5:30), 133 Geary St., present shows of contemporary American and foreign art. Founded as an art shop in 1902 by Ephraim B. Courvoisier, the business was burned out in 1906. Courvoisier recouped his losses by restoring the fire-damaged paintings of wealthy collectors. The friend of such artists as Charles Rollo Peters, Thomas Hill, and William Keith, he developed a large clientele which followed him even when reverses forced him for a while to a Kearny Street alley. The firm was taken over by his son in 1927. After its exhibition in 1938 of the original water colors on celluloid for Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, it acquired the exclusive agency for sale of the Originals from Disney's future productions.

47. Behind a shining all-glass three-story facade, the ANGELO J. ROSSI COMPANY (open weekdays 8-6:30, Sun. 8-12 a.m.), 45 Grant Ave., streamlined florist's establishment owned by the Mayor of San Francisco, displays masses of fragrant bloom against mirrored walls.

48. A neo-Gothic eight-story building houses O'CONNOR, MOF-FATT AND COMPANY (open 9:45-5:25), NW. corner O'Farrell and Stockton Sts., founded in 1866 by Bryan O'Connor, newly arrived from Australia. O'Connor was so impressed with the city's prosperity that he sent to Melbourne for his friend, George Moffatt. Since the death of O'Connor and retirement of Moffatt in 1887, the business has been carried on by descendants of the first employees. The original dry-goods store moved in 1929 to its present building and expanded, becoming a department store.

49. Young Adolphe Roos, who founded the clothing firm of ROOS BROTHERS (open 9:45-5:25), NE. corner Stockton and Market Sts., arrived in San Francisco from France in time for the stampede to the Virginia City (Nevada) mines, where he made his stake by outfitting miners. Returning to San Francisco, he sent for his younger brother, Achille; together they opened the first Roos Brothers store on Leidesdorff Street in 1865. Since 1908 the firm, now guided by the founder's son, Robert Roos, has occupied its present five-story building. Remodeled (1936-38) at a cost of $1,000,000 (J. S. Fairweather, building architect; Albert R. Williams, interior architect), it was transformed into a series of individually designed shops, its Street entrances equipped with doors automatically opened by electric beams and its interiors with fluorescent illumination simulating daylight. The various shops are panelled with rare woods—hairwood from the British Isles, Yuba wood from Australia, Jenisero from Central America; in one shop is a mosaic in which more than 48 varieties are used.

50. Largest daily circulation in the city is boasted by the paper published in the SAN FRANCISCO NEWS BUILDING (visitors shown through plant by appointment), 812 Mission St., whose twelve presses grind out eight regular editions daily. The first edition is released at 11 a.m., the last at 5 .30 p.m. The paper is one of the Scripps-Howard chain.

51. The 18-story gray-green HUMBOLDT BANK BUILDING, 785 Market St., capped by a fantastically adorned dome, was built in 1907 (Meyer and O'Brien, architects). Under construction when the earthquake and fire destroyed it, it was completely rebuilt—the first architectural contract placed after the disaster. Bronze doors lead into the banking room of the Bank of America (open Mon.-Fri. 10-3:30, Sat. 10-12), ornate with white Ionic columns, warm Sienna marbles, and buff mosaic floor.

52. The domed, granite AMERICAN TRUST COMPANY BUILDING (Savings Union Office; open 10-3 Mon.-Fri., 10-12 Sat.), NW. corner Market St., Grant Ave., and O'Farrell St., was erected in 1910. The pediment above the Ionic-pillared portico is adorned with Haig Patigian's bas-reliefs of the head of Liberty between flying eagles (based on Augustus St. Gauden's design for $20 gold pieces). Corinthian columns, Travernelle marble pilasters, and Caen stone walls lend richness to the 65-foot-high banking room. The American Trust Company was formed through successive mergers of older institutions, one of which, the Savings Union Bank and Trust Company, was the city's oldest surviving savings bank, dating back to foundation of the San Francisco Accumulating Fund Association in 1854.

53. The ageing six-story buff-brick BANCROFT BUILDING, 731 Market St., is named for the Bancroft brothers—historian Hubert Howe and publisher Albert L.—who conducted in its five-story predecessor (second brick building erected on Market Street) a book-selling and Publishing firm. In partnership with George L. Kenny, Hubert Howe Bancroft previously had gone into the book-selling business in quarters on Montgomery Street. Joining the firm, his brother Albert planned the new Market Street office building, opened in 1870. In 1875 the firm announced: “Bancroft's Historical Library is the basis of important scientific and descriptive works of a local nature, and maps or books of reference relating to the Pacific Coast.” In the same year appeared the first of Hubert Howe Bancroft's histories, Volume I of his Native Races of the Pacific Coast of North America. In the fifth-floor Publishing department, Bancroft went ahead with his prodigious labors of compiling in detail the history of all Western America. One of the pioneers of mass production methods in literature, he directed a large staff of anonymous collaborators. In 1884 he published the first of his seven volumes on the history of California—carrying a list of quoted authorities 66 pages long. Before his death in 1918, he had accumulated a library of 500 or more rare manuscripts and 60,000 volumes, now housed in the Bancroft Library at the University of California.

54. The 22-story steel-and-concrete CENTRAL TOWER, SW. corner Market and Third Sts., defies detection as the old Claus Spreckels Building. It was remodeled along functional lines in 1938. The simply decorated entrance relieves the severity of the unornamented vertical shaft with its six-story tower. In the lobby, the walls are vitriolite brick. In 1895 Claus Spreckels bought the site and erected a 19-story building in which the Call was published for a time. During the Spanish-American War, a cannon thundered news of American victories from the roof. Only bright spot in a darkened and devastated area, during the days after April 18, 1906, was the light kept burning in the partly destroyed cupola. In its report the Geological Survey said “the general behavior of this structure demonstrates that high buildings subject to earthquake can be erected with safety even on sand foundations.”

55. The 12-story HEARST BUILDING (visitors conducted on two-hour tour 7-9 p.m.), SE. corner Market and Third Sts., of white terra cotta with polychrome ornamentation, houses the San Francisco Examiner, first paper in the Hearst chain. The first of its five regular daily editions appears on the streets about seven o'clock in the evening. On this site was the Nucleus Hotel, first brick building on Market Street, which surprised everyone—contrary to the woeful predictions of skeptics—by surviving the earthquake of 1868 almost unscathed.

56. Beloved to old-timers is LOTTA'S FOUNTAIN, corner Market, Geary, and Kearny Sts., the cast-iron shaft presented to the city in 1875 by little laughing, black-eyed Lotta Crabtree, who won the adoration of San Francisco in the era of gallantry and easy money that followed the age of gold. The 24-foot fountain within its granite base, conventional lion heads, and brass medallions depicting California scenes is commonplace, but its donor was one of the sensational personages of the last Century.

In 1853 when Lola Montez visited Rabbit Creek, a small gold camp near Grass Valley, she taught singing and dancing to the eight-year-old daughter of one of the prospectors. Not long afterward her pupil made a sensational first appearance in a Sierra mining town: gold as well as applause was showered upon the young Lotta by generous Argonauts. Her subsequent debut in San Francisco was no less encouraging. At the age of 17 she appeared on the New York stage, and at 44 she retired. Fortunate real estate investments augmented her fortune, which at her death (1924) exceeded $4,000,000. After her retirement her fountain was neglected, and its site, a busy downtown intersection, became known as Newspaper Square from the large number of newsboys who congregated there. In 1910, however, another—and perhaps a greater—singer brought Lotta's Fountain once more into prominence. At midnight on Christmas Eve, hushed thousands massed as Louisa Tetrazzini sang “The Last Rose of Summer” beside the fountain. In remembrance of the event, a bas-relief portrait of the singer by Haig Patigian was added to the monument.

57. When the De Young brothers, proprietors of the San Francisco Chronicle, decided in 1890 to put up the ten-story red brick DE YOUNG BUILDING, NE. corner Market, Geary, and Kearny Sts., they were considered optimistic. On a site then rather far west of the business district, they proposed to erect a steel-frame structure—the first in San Francisco. Chicago architects Burnham and Root designed an edifice whose simple lines reveal the Romanesque style of their teacher, Henry Hobson Richardson. Wiseacres were convinced the structure would not survive an earthquake—but the disaster of 1906 proved them to be wrong. A 17-story annex just completed at the time was repaired and the interior of the original structure rebuilt. Here, until 1924, was the home of the Chronicle.

58. One of the dozen sidewalk booths shaded by gay umbrellas which enliven the streets of the shopping district is the FLOWER STAND, Market, Geary, and Kearny Sts., standing on the location where the first flower vendors stood in the 188o's. When the De Young Building was erected, Michael de Young allowed the vendors—most of whom were boys of Italian, Belgian, Irish, or Armenian descent—to sell their flowers in front of the building, protecting them from the policemen. The curbside Stands were first licensed in 1904. All attempts to suppress them have been halted by storms of protest from press and public. Their wares change with the seasons—from January, when the first frilled golden-yellow daffodils and great armfuls of feathery acacia with its fluffy tassels make their appearance, to December, when hosts of flaming crimson poinsettias and great bunches of scarlet toyon berries herald the advent of the holidays.

59. The original PALACE HOTEL, Market and New Montgomery Sts., was (according to Oscar Lewis and Carroll Hall) “at least four times too large for its period and place, but the town had never had a sense of proportion and no one was disturbed.” Least disturbed was its builder, William C. Ralston. This “world's grandest hotel” would cover two and one-half acres; it would soar to the ingressive height of seven stories and contain 800 rooms; its marble-paved, glass-roofed Grand Court (about which the rectangular structure was designed) would face Montgomery Street through an arched driveway; artesian wells drilled on the spot would supply its Storage reservoirs with 760,000 gallons of water; its rooms would contain “noiseless” water closets and gadgets designed to make life at the Palace effortless and luxurious.

But three years’ advance Publicity satiated even a town reared on superlatives, and before the hotel opened San Franciscans had chuckled at the announcement of local columnist “Derrick Dodd”: “The statistician of the News Letter estimates the ground covered…to be eleven hundred and fifty-four Square miles, six yards, two inches… A contract is already given out for the construction of a flume from the Yosemite to conduct the Bridal Veil fall thither, and which it is designed to have pour over the east front…. The beds are made with Swiss watch Springs and stuffed with camel's hair, each single hair costing eleven cents…. There are thirty-four elevators in all—four for passengers, ten for baggage and twenty for mixed drinks. Each elevator contains a piano and a bowling alley…” Of the dining room the News Letter predicted: “All the entrees will be sprinkled with gold dust…”

For once, San Francisco was to be treated to reality that exceeded even the exaggerations of its humorists. Ralston, desirous of developing local industries, financed many factories to supply the hotel's needs until his cautious associate, Senator William Sharon, finally asked: “If you are going a buy a foundry for a nail, a ranch for a plank, and a manufactory to build furniture, where is this going to end?” Ralston continued to pour millions into the structure—and died before its completion, owing the Bank of California $4,000,000. Sharon, who had wondered “where it was going to end,” found himself in possession of the hotel.

Through the doors of the Palace, opened in October 1875, passed “the great, the near-great, and the merely flamboyant…bonanza kings and royalty alike… Grant, Sheridan, and Sherman were feasted in the banquet halls; and the Friday night Cotillion Club danced…in the ballroom…” Here the graceful manners of Oscar Wilde charmed a local “lady reporter,” and James J. Jeffries gave a champagne party for a sweater-clad coterie. Here royalty was impressed (said Brazil's emperor, Dom Pedro II, in 1876: “Nothing makes me ashamed of Brazil so much as the Palace Hotel.”) and royalty died (King David Kalahaua of Hawaii, January 20, 1891).

For more than a quarter of a Century the Palace played host to the world. As its marble halls became less fabulous its reputation grew more so. Tales related of its “great and near-great” were echoed in a hundred cities. Climax to them all were the stories told of the early morning of April 18, 1906 when the hotel's scores of guests were shaken violently from slumber and sent wide-eyed into debris-strewn streets. Among the most alarmed was Enrico Caruso; the great tenor joined fellow members of the Metropolitan Opera Company carrying a portrait of Theodore Roosevelt and wearing a towel about his famous throat. Although it suffered only minor interior damage by the ’quake, the Palace succumbed, its elaborate fire-fighting system useless against the raging inferno.

Rebuilt in 1909 on the same site, the present eight-story tan-brick and terra cotta structure is in the Beaux Art tradition. There are low grills at the windows and several ornate iron balconies. The eighth floor is surmounted by an elaborate frieze. Reminders of the past are a porte cochere on the site of the carriage entrance to the Grand Court, facing (across the lobby) the present glass-roofed Palm Court; the Comstock Room, a duplicate of the room wherein the “Nevada Four” opened their poker sessions with a “take-out” of $75,000 in ivory chips; the Happy Valley cocktail lounge with its Sotomayor murals of Lotta Crabtree and “Emperor” Norton; and the Pied Piper Buffet (for men) with its mahogany fixtures and Maxfield Parrish painting (modeled by Maude Adams). No less illustrious than the guests of the old Palace have been the patrons of the new. In 1923 the hotel was the saddened host to Warren G. Harding, who died in the presidential suite.

A corridor leads from the Palace lobby to the Studios of KSFO (entrance at 140 Jessie St.), constructed in 1938 at a cost of $400,000. The interior is effectively decorated in soft blues and grays highlighted by chromium trim. A circular staircase leads to the second-floor reception lounge, executive offices, master control room, and broadcasting Studios. The third floor is devoted to the engineering, script, music, art and advertising departments.

To prevent vibration, each studio is suspended on springs, with walls and ceilings constructed so as to form no parallel lines, thus eliminating echoes. A layer of spun glass fibre underlying perforated walls soundproofs each studio.

60. San Francisco's oldest surviving newspaper, the Call-Bulletin, is published at the CALL BUILDING (visitors shown through plant by appointment), 74 New Montgomery St., its presses turning out four daily editions (the first appears about 10.45 a.m.) with an average circulation of 110,000.

61. The gray stone walls, sometimes floodlighted in gleaming yellow splendor by night, of the monolithic PACIFIC TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH BUILDING, 140 New Montgomery St., enclose the head offices of a telephone network embracing all the far West. Largest building on the Pacific Coast devoted to one firm's exclusive use at the time of its completion in 1925, it was built at a cost of $3,000,000 (J. R. Miller, T. L. Pflueger, and A. A. Cantin, architects). From each of the four facades of its four-story tower, two huge stone eagles survey the city from their 26-story perches. The terra cotta facade, with its lofty piers and mullions tapering upward in Gothic effect, cloaks but does not hide the structural lines. The building's 210,000 square feet of floor space provide working room for 2,000 employees.

62. A monument to San Francisco's early-day regard for learning is the nine-story MECHANICS INSTITUTE BUILDING, 57 Post St., erected in 1910 (Albert Pissis, architect), which houses the Mechanics-Mercantile Library (open weekdays 9 a.m.-10 p.m., Sun. 1-5). On December 11, 1854, a group of Citizens met in the tax collector's office to found a Mechanics’ Institute for the advancement of the mechanic arts and sciences; and on March 6, 1855, they adopted a Constitution providing for “the establishment of a library, reading room, the collection of a cabinet, scientific apparatus, works of art, and for other literary and scientific purposes.” With four books presented by one S. Bugbee—The Bible, the Constitution of the United States, an Encyclopaedia of Architecture, and Curtis on Conveyancing—the library began its activities in June, 1855.

Progress of the association began with the inauguration of annual Mechanics’ and Manufacturers’ Fairs, September 7, 1857, in a pavilion on Montgomery Street between Post and Sutter Streets. As the fairs became civic events of prime importance, one sprawling wooden pavilion after another was built to house them—six in all, of which the third and fourth occupied Union Square; the fifth, Eighth Street between Mission and Market Streets; and the sixth, the site of the Civic Auditorium. The last of the fairs was held in 1899.

In 1866 the Institute built its first structure on the present site. By 1872 it had collected a library of 17,239 volumes. In January, 1906 it merged with the Mercantile Library Association, organized in 1852 by a group of merchants. The merger of the two associations, whose combined library numbered 200,000 volumes, had scarcely been affected, however, when the fire of 1906 destroyed books, equipment, and building. Hard hit, the Institute nevertheless had acquired a new library of 40,000 volumes by 1912, when it realized from the sale of its pavilion lot to the city the sum of $700,000. Its present (1940) collection of 195,000 volumes is especially notable in the fields of science and technology. The Mechanics’ Institute also provides for its members a chess and checker room and a lecture series.

63. The 13-story CROCKER FIRST NATIONAL BANK, NW. corner Post and Montgomery Sts., Stands on the site of the old Masonic Temple. Oldest national bank in California, it is a merger of the First National Bank, opened in 1871 with James D. Phelan as President, and the Crocker National Bank, organized in 1883 by Charles Crocker (one of the “Big Four”). The two banks were Consolidated in 1926. Of Italian Renaissance style, its entrance is distinguished by a rotunda supported on granite pillars (Willis Polk and Company, architects).

64. Prosaic monument to a story-book past is the 12-story granite NEVADA BANK BUILDING, NE. corner Montgomery and Market Sts., housing the Wells Fargo Bank and Union Trust Company. A lively chapter in the history of the West is the story of its parent institution, Wells Fargo and Company. A year before its incorporation in New York the express firm was buying and selling “dust,” receiving deposits, and selling exchange. One of the few institutions to survive the “Black Friday” of February 1855, it operated its banking business until 1878 in conjunction with its express activities. In 1905 the Wells Fargo Bank was Consolidated with the Nevada Bank and in 1924, with the Union Trust Company. The present building, built in 1894, was raised to a height of ten stories in 1903 and to twelve in 1907-08. The History Room on the tenth floor houses a historical library and a museum of pioneer relics including a stagecoach, Veteran of the Overland Trail; the golden spike which Leland Stanford drove at Promontory, Utah, in 1869; and a gold scale that weighed $55,000,000 worth of the gold dust mined in the Mother Lode.

65. The neo-Gothic, gable-roofed ONE ELEVEN SUTTER BUILDING, SW. corner Montgomery and Sutter Sts., since 1927 has reared its buff-colored terra cotta facades 22 stories above a site which was worth $300 when James Lick bought it and $175,000 when he died. The marble-inlaid lobby and corridors of the interior (Schultze and Weaver, architects)—the pillars adorned with green and white Verde Antique from Greece, the lobby floor with Hungarian red, the corridor floors with Italian Botticino, Tennessee pink, and Belgian Hack marbles—rivai the luxurious interior of the Lick House, which Lick built here in 1862. The latter hostelry boasted $1,000 gas chandeliers, mirrored walls, and mosaic floors of rare imported woods. Trained as a cabinet-maker, the eccentric millionaire finished with his own hands the woodwork of the luxurious banquet hall.

The building houses offices and studios of the National Broadcasting Company's stations KGO and KPO (open 8:30 a.m.-11 p.m.). On the second and third floors are the reception lobby, executive and business offices, and production departments. The broadcasting studios, each with its own control room and monitor's booth, occupy the 21st and 22nd stories. Sharing these top floors respectively are the music library, largest of its kind west of New York, and the master control room, distributor for incoming broadcasts.

66. Because of well-balanced construction, the 16-story ALEXANDER BUILDING, SW. corner Montgomery and Bush Sts., a simple shaft faced in buff-colored brick and terra cotta whose vertical lines give it a towering grace, is considered ideal for studies of earthquake stresses on skyscrapers. Seismographs installed at top, center, and bottom of the structure by the U. S. Geodetic Survey furnish research data for the University of California and Stanford University. The building was erected in 1921 (Lewis Hobart, architect).

67. “The Monument to 1929”—thus have financial circles, since the stock market crash, referred to the three-story granite SAN FRANCISCO CURB EXCHANGE BUILDING, 350 Bush St. (J. R. Miller and T. L. Pflueger, architects). Scene of the frenzied speculation of the 1920’s, it housed the San Francisco Mining Exchange until 1928, when it was taken over by the newly organized San Francisco Curb Exchange. Remodeled in 1938, when the Curb Exchange was absorbed by the San Francisco Stock Exchange, it now houses the California State Chamber of Commerce.

68. “An example to all Western architects of a model office building,” wrote Ernest Peixotto in 1893 of the MILLS BUILDING, 220 Montgomery Street, built in 1891 for banker Darius Ogden Mills (Burnham and Root, architects). “It is an architectural composition, and not mere walls pierced by window openings… It consists of a two-story basement of Inyo marble, carrying a buff brick super-structure of seven stories, crowned by a two-story attic. The angle piers…are massive and sufficient; between them piers spring from the third story, crowned in the eighth by arches… The effect of height is strengthened by the strongly marked lines of the piers… The focus for ornament is the Montgomery Street entrance, which rises to an arch…as large and ample as it should be…” So sound was the building's construction that it survived the fire of 1906 with little dam-age to its exterior. Adhering to the original design, Willis Polk supervised its restoration in 1908 and the erection of additions in 1914 and 1918. When the adjoining 22-story MILLS TOWER (entrance at 220 Bush St.)—to which all but the second of the older building's ten floors have direct access—was erected in 1931, architect Lewis Hobart also followed Burnham's design. The same buff-colored pressed brick especially manufactured for the original building was used on its facade. The combined buildings contain 1,300 offices and 350,000 feet of floor space.

On the site of the Mills Building in the 1860’s stood Platt's Hall, a great Square auditorium where people flocked for lectures, concerts, and political Conventions. On its stage, Thomas Starr King lifted Bret Harte from obscurity by reading his poem, “The Reveille.” Among the attractions which drew crowds were Henry Ward Beecher and General Tom Thumb and his wife.

69. Largest office building on the Pacific Coast, the block-long RUSS BUILDING, 235 Montgomery St., Stands on the ground where Christian Russ, in 1847, established a residence for his family of twelve. Here in 1861 the owner of Russ’ Gardens built the Russ House, a hotel long favored by farmers, miners and merchants. Still owned by his heirs, its site, nine decades after Russ acquired it at auction for $37.50, was assessed at $675,000. Construction of today's $5,500,000 skyscraper, begun in July, 1926, was completed in September, 1927. Modernized Gothic, the massive, sandy-hued edifice rises 31 stories, its three wings deployed in the shape of an “E” (George W. Kelham, architect). Its 1,370 offices, comprising 335,245 square feet of floor space, house 3,500 persons. With its 400-car garage and its eleventh-story complete shopping department, the building provides its personnel with every service from a Public Library branch to a language translation bureau.

70. The 15-story FINANCIAL CENTER BUILDING, NW. corner Montgomery and California Sts., marks the SITE OF THE PARROTT BUILDING. The latter, San Francisco's first stone structure, was built in 1852 by Chinese masons of granite blocks quarried in China. When the Chinese struck for higher pay they won their demands because no other available workers could read the markings on the blocks. The old building survived earthquake and fire but was torn down in 1926 when the present skyscraper was built.

71. Ten lofty granite Tuscan columns flanked by massive pylons dominate the temple-like Pine Street facade of the SAN FRANCISCO STOCK EXCHANGE BUILDING (open Mon.-Fri. 7-2:30, Sat. 7-11), SW. corner Pine and Sansome Sts. (public entrance 155 San-some St.). The pylons, carved by Ralph Stackpole, symbolizing Mother Earth's fruitfulness and Man's inventive genius, stand on either side of the steps. Above the Pine Street wing, which houses the Trading Room (members only), rises the 12-story gray granite tower of the administration wing. Above its doorway, carved in high relief, is Stackpole's The Progress of Man, and on the lintel, a sculptured eagle with outstretched wings. The walls of the public lobby are inlaid with dusky red Levanto marble and the ceiling with gold leaf in a geometric star design. A marble stairway ascends to the visitors’ gallery overlooking the Trading Room.

Above the high windows of east and west walls of the Trading Room are Robert Boardman Howard's two groups of three sculptured panels—one portraying development of electric power; the other, development of gas power. Along north and south walls extend the quotation boards, their markers’ galleries equipped with ticker receiving instruments and headset telephones. Beneath, an annunciator signal system summons members to their booths along the sides of the room. At the center of the brown rubber-tiled trading floor is stationed the telegraph ticker transmitting station, which sends reports of every transaction to brokers’ offices along the Pacific Coast. Around it are stationed four oak-panelled hollow enclosures for nine trading posts, each equipped with electrically synchronized stamping devices that indicate the time of every order to a tenth of a minute. Essential to the rapid handling of Orders is the telephone exchange, busiest in San Francisco, which handles an estimated total of 5,000 calls per hour of trading. It can handle 1,800 calls at one time, with a peak capacity of 180,000 words per minute.

The ninth floor of the administration wing houses headquarters of the Governing Board and exchange officials. The solid oak door to the walnut-panelled Governing Board room is carved with a bas-relief by Robert Boardman Howard depicting the steps in construction of a building. The Lunch Club quarters (not open to the public) on the tenth and eleventh floors are decorated with frescoes by Diego Rivera depicting California history.

In the basement of a building a block northward, the Stock and Bond Exchange was organized September 18, 1882, by 19 pioneer brokers. It succeeded several earlier exchanges, of which the first, the San Francisco Stock and Exchange Board (contemporaneously referred to as “The Forty Thieves”), had been established in 1862. Since 1882 the present exchange has stopped functioning as the pulse of business life on the Pacific Coast on only three occasions: April 18, 1906, because of the earthquake and fire; July 31, 1914, because of the World War; and March 2-14, 1933, because of the National bank holiday. Its memberships, which sold for $50 in 1882 and rose to an all-time high of $225,000 in 1928, today sell for varying sums, the most recent sale price having been $16,500.

72. The BANK OF CALIFORNIA (open Mon.-Fri. 10-3, Sat. 10-12), NW. corner Sansome and California Sts., was erected in 1908 (Bliss and Faville, architects). The gray granite building has tall and finely proportioned Corinthian colonnades. The immense banking room, 112 feet long and 54 feet high, faced in Tennessee marble, resembles a Roman basilica. In the rear on either side of a large clock are carved marble lions (Arthur Putnam, sculptor). Less subdued in its magnificence was the palatial edifice erected on this site to house the bank in 1867, three years after its establishment with Darius Ogden Mills as president and William C. Ralston as cashier. To clear the site they moved the Tehama House—which humorist “John Phoenix” celebrated in A Legend of the Tehama House—a popular hostelry among Mexican rancheros and military and naval officers. Ralston built a handsome two-story structure with tall arched Windows surmounted by medallions and framed in marble columns, a cornice crowned with a stone balustrade supporting fretted vases, doors and balcony railings of bronze, and a burnished copper roof. For a decade the bank was the financial colossus of all the territory west of the Rocky Mountains. It reached into Nevada, during the Comstock Lode boom, to establish four branch banks. When the collapse of the silver boom brought it crashing from financial dominance in 1875, the whole State was shaken. But the reorganized bank survived and grew, taking over in 1905 the London and San Francisco Bank, Ltd., with branches in Oregon and Washington.

Downtown

CITY HALL

EXPOSITION AUDITORIUM

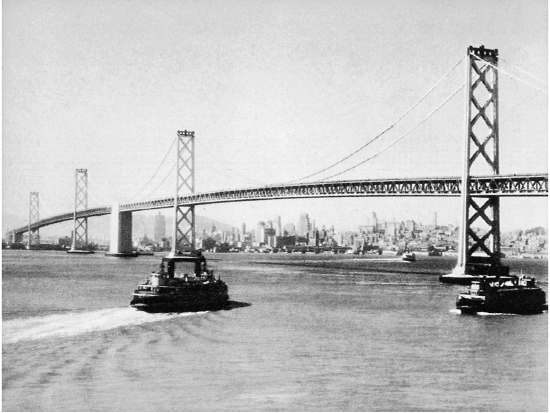

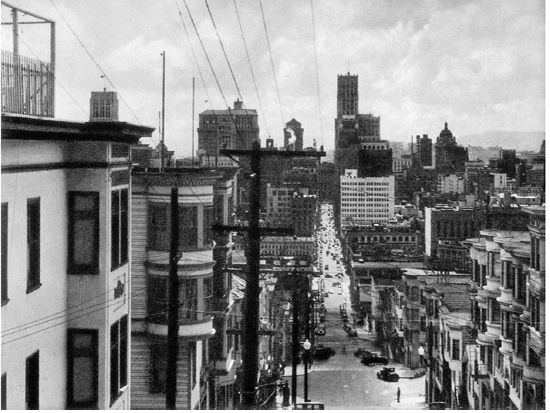

SAN FRANCISCO'S JAGGED TERRACES FROM THE BAY © Gabriel Moulin

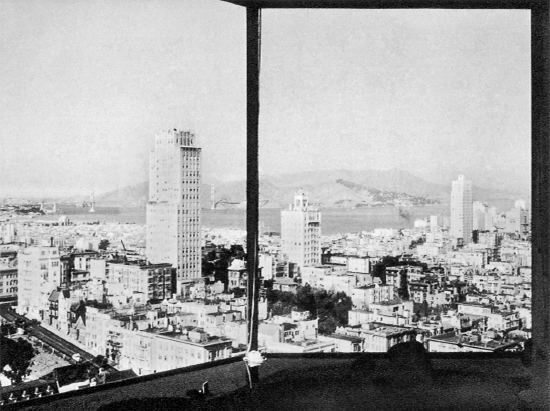

SKYLINE FROM A SKY WINDOW

MARKET STREET AT 5:15

LABOR DAY PARADE UP MARKET STREET

A FIVE-MINUTE WALK FROM THE BUSINESS DISTRICT

FOUR-FIFTY SUTTER BUILDING AND SIR FRANCIS DRAKE HOTEL

PORTSMOUTH PLAZA

MONTGOMERY BLOCK

MONUMENT TO ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON. IN PORTSMOUTH PLAZA

A glass case in the main office contains the scales on which Darius Ogden Mills weighed some $50,000,000 of miners’ gold in the tent which he set up at Columbia in 1849, before Coming to San Francisco to become President of Ralston's bank.

73. Venerable home of a parent Organization of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce was the 14-story MERCHANTS’ EXCHANGE BUILDING, NE. corner California and Sansome Sts. Here until 1911 the city's moguls of industry and agriculture congregated to regulate and put through huge deals in hay, grain, and shipping. In bonanza days Robert Louis Stevenson used to haunt the Exchange's central board room, where he found material—in such men as John D. Spreckels—for heroes of The Wreckers.

Since 1851 the main-floor MARINE EXCHANGE (always open) has operated continuously except during 1906 and though much of its romantic element was lost with the passing of sailing ships, its function remains virtually the same. Outgrowth of the old Merchants’ Exchange and Reading Room established in 1849 by Messrs. Sweeny and Baugh, who operated the signal station on Telegraph Hill, the Exchange is connected with lookout stations which report every movement of local shipping. It receives and compiles complete information from every Pacific Coast vessel from start to finish of every voyage. Files on the Exchange's mezzanine floor record launchings, cargoes, crews, disasters, sales, weather reports—all marine information required by shippers, ship owners, ship chandlers, warehousemen, exporters, and importers. Before the advent of the telephone a messenger boy on horse-back rushed news of incoming ships from the Exchange to the city's major hotels.

At one end of the Exchange, beneath an arch set at right angles to the south wall, hangs the original Vigilance Committee bell which hung on top of Fort Gunnybags in 1856. The bell, which once tolled the death knell of Cora and Casey, now clangs to announce to the Exchange some mishap to a ship whose home port is San Francisco.

Though grain, shipping, insurance, and similar firms still occupy this building, which survived the fire of 1906, its chief interest lies in such features as evoke its past. Something of its lusty social tradition survives in the Commercial Club occupying three top stories and in the Merchants’ Exchange Club in the basement. Reminiscent of other days are Nils Hagerup's paintings on walls of the main lobby depicting Amundsen's explorations in the Gjoa and W. A. Coulter's ships in port and at sea. The latter's huge painting of the San Francisco fire hangs, draped with red velvet, in the billiard room of the Merchants’ Exchange Club.

74. From ground above the hulls of long-buried sailing ships, the FEDERAL RESERVE BANK (open Mon.-Fri. 8:30-4:30, Sat. 8:30-1), NE. corner Sansome and Sacramento Sts., rears its eight white granite Ionic columns, rising up three of its seven stories to a classic pediment (George W. Kelham, architect). When steam shovels excavated the basement vaults in 1922, they exposed the oaken skeleton of the city's first prison, the brig Euphemia, moored at Long Wharf in the 1850’s. The Sansome Street entrance leads into a Travertine marble lobby with murals by Jules Guerin. From the Battery Street side, ramps descend to the vaults, where trucks discharge treasure for deposit behind 36-ton doors, under the hawk-eyed gaze of guards.

75. By day, bathed in sunlight, the 30-story SHELL BUILDING, NW. corner Battery and Bush Sts., San Francisco headquarters of the Shell Oil Company empire, is a buff, tapering shaft; by night, flood-light-swept, a tower looming in amber radiance. Its Bush Street entrance is enriched with a filigree design in marble and bronze. Erected in 1929 (George W. Kelham, architect), it broke Pacific Coast records for rapid construction, rising three stories each week.

76. With heroic vigor, the bronze figures of the DONAHUE MONUMENT, Battery, Bush, and Market Sts. (Douglas Tilden, sculptor)—five brawny, half-naked workmen, struggling to force by lever a mechanical punch through plate metal—are poised on their granite base, in a triangular pedestrian island. Executed in 1899, the monument is James Mervyn Donahue's memorial to his father, Peter Donahue, founder of San Francisco's first iron foundry, first Street railway, and first gas company. A bronze plaque etched with a map in the pavement at its base marks the shoreline as it was before Yerba Buena Cove was filled in, when Market Street from this point north-east was a 1,000-foot wharf.

77. On what was the shifting sand of a Yerba Buena beach lot towers the 22-story, gray granite STANDARD OIL BUILDING, SW. corner Sansome and Bush Sts., erected in 1921 (George W. Kelham, architect). Its cornice-overhung facade, the upper stories adorned with Doric columns, is a modern adaptation of the Florentine style. The two-story vaulted entrance leads into an ornate lobby of bronze and marble.

78. To trace the origins of the ANGLO CALIFORNIA NATIONAL BANK (open Mon.-Fri. 10-3, Sat. 10-12), 1 Sansome St., is to follow the ramifications of international finance. One of its parent institutions, the Anglo Californian Bank, Limited, organized in London in 1873, took over the San Francisco branch of J. and W. Seligman and Company of New York, London, Paris, and Frankfurt. Three years later Lazard Frères, silk importers and exchange dealers of New York, London, and Paris, opened a San Francisco branch, out of which grew, in 1884, the London, Paris, and American Bank, Limited, of Great Britain. The two were Consolidated in 1909 under the latter name and a new bank, the Anglo-Californian Trust Company, emerged to handle the older bank's savings business. The Fleishhacker brothers, Herbert and Mortimer, gained financial prominence as presidents of the two institutions. By 1920 the Anglo-Californian Trust Company had absorbed four San Francisco banks, and by 1928 it had opened eight local branches. From the merger of the two Fleishhacker banks in 1932 came today's Anglo California National Bank, which soon reached into the rest of the State. By 1939—when the number of banks absorbed by it and its parent institutions had grown to 15—it was operating branches from Redding in the north to Bakersfield in the south.

79. Of the thousands of commuters who once poured daily through the Ferry Building, for six decades San Francisco's chief gateway from the east, most now enter the city through the BRIDGE TERMINAL BUILDING, Mission, First, and Fremont Sts. The low-spreading three-story steel-and-concrete structure, completed in 1939 at a cost of $2,300,000, is the terminal for electric interurban trains carrying passengers over the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge to the East Bay. Through the terminal pass an estimated number of 60,000 persons daily, 21,000,000 annually. During the rush hour, between 4:45 and 5:45 p.m., when 37 trains arrive and depart, the building resounds with the din of shouting newsboys, taxi barkers, and streetcars clanging up the wide ramp from First and Mission Streets to discharge passengers at the entrance. Ramps and stairways ascend to the loading platforms which separate the three pairs of tracks. To diminish noise, the rails are laid on timber ties embedded in concrete which rests on a two-inch insulated cushion. A viaduct carries the trains high above streets and buildings onto the lower bridge deck. Their speed is governed by a code picked from the tracks by a receiver attached near the front axles and transmitted to an indicator in the motorman's cab. If the motorman fails to slow down within two and one-half seconds after a warning bell indicates a slower speed, the train automatically stops.

80. Exponent of fine printing is the firm of TAYLOR AND TAYLOR, 404 Mission St., established in 1896 by Edward DeWitt Taylor, who, since the death of his brother and co-partner (Henry H. Taylor) in 1937, remains sole owner. Types, Borders & Miscellany of Taylor & Taylor, included in the American Institute of Graphic Arts’ “Fifty Books of the Year” for 1940, has been described by Oscar Lewis as having a “classical simplicity of typographical design.” Besides limited editions of Californiana, catalogs for art exhibits, and items for various cultural institutions, Taylor and Taylor are printers of much distinctive commercial advertising. Edward Taylor gained local fame for his work in the installation of the Denham cost-finding system among the printing trades of the Bay region.

In the firm's composing room Stands an ornamental Columbian hand press (1818), a reminder of Taylor's first printing venture in 1882: The Observer—a journal “devoted to general literature and the interests of the Western Addition.”

The firm's typographical library contains two centuries of European type specimens and examples of fine printing from the fifteenth Century to the present. Included are such rare editions as the Keimscott Chaucer from the press of William Morris and one of the world's most comprehensive collections of the works of Homer.

81. On wooden piles driven into the mud of what was Yerba Buena Cove rest the 17 steel-and-concrete stories of the PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC BUILDING, 245 Market St., headquarters of the Nation's third largest Utilities system, which originated with Peter Donahue's gas company (1852) and the California Electric Light Company (1879), both Pacific Coast pioneers. Designed by John M. Bakewell, the building was opened in March, 1925. Over the three-story arched entrance is Edgar Walter's bas-relief symbolizing the application of electric power to man's needs. The granite keystones of the first-story arches, carved by the same sculptor, represent the rugged mountain country whose rushing torrents have been tapped for hydroelectric power.