Landmarks of the Old Town

“Cities, like men, have their birth, growth and maturer years. Some are born Titans, and from the beginning promise to be mighty in their deeds, however wilful and destructive.”

—The Annals of San Francisco (1852)

THE MARVEL is not that so little but that so much of the city's venerable and homely architecture has escaped time's vicissitudes—of which not the least was the fire of 1906. Recalling the great fire of 1851—in which the El Dorado gambling saloon was saved by the citizenry's desperate stand—one may suppose that the area around Portsmouth Square was spared, less by a shift of wind, than by San Franciscans stubbornly defending the cradle of their traditions. Unlike the carefully preserved Vieux Carré of New Orleans, however, it survives, not through care, but through sheer neglect.

On the muddy shores of a little cove at the southeastern base of a rocky hill (Telegraph Hill), San Francisco was born. A short distance inland, Francisco de Haro marked out his Calle de la Fundacion, skirting the shore on its way north-northwest over the hill toward the Presidio (along the present Grant Avenue). Just north of Washington and Montgomery streets was an inlet from which the shoreline ran diagonally southeast to Rincon Hill (western terminus of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge). From the rocky headland north of the inlet, first called Punta del Embarcadero and later Clark's Point (now the intersection of Battery Street and Broadway), William S. Clark built the first pile wharf in 1847. The line of anchorage was the present Battery Street, where the Russians loaded grain and meat for their Alaskan colonies, where the frigate Artemisia—first French ship to enter the Bay—anchored in 1827, and the San Luis—first American warship to enter the harbor—in 1841. When the warship Portsmouth dropped anchor July 8, 1846, Captain John B. Montgomery disembarked at what is now the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay streets (see plaqu'e on Bank of America Building, 552 Montgomery St.). The Plaza (later Portsmouth Square) was only 500 feet west of the water's edge.

West of the Plaza, facing the Calle de la Fundacion between the two cross streets (now Clay and Washington streets) which ran east-ward to the line of Montgomery Street along the water's edge, “the first tenement” (reports The Annals of San Francisco) had been “constructed in the year 1835 by Captain W. R. Richardson, and up to the year 1846, there might not be more than twenty or thirty houses of all descriptions in the place.” Richardson's dwelling (see plaque between 823 and 827 Grant Avenue) was “a large tent, supported on four redwood posts and covered with a ship's foresail.” Near by on July 4, 1836, Jacob Primer Leese completed Yerba Buena's first permanent dwelling—”a rather grand structure, being made of frame sixty feet long and twenty-five feet broad.” (The plaque at the southwest corner of Clay Street and Grant Avenue states incorrectly that here Leese “erected the first building in San Francisco,” birthplace of “the first white child in San Francisco… April 15, 1838.” The first building was erected at the Presidio in 1776, and the first white child was born at the site of Mission Dolores August 10, 1776.) Not to be outdone by Leese, Richardson erected his adobe “Casa Grande.”

Soon after United States conquest, Americans had built a sprawling town on the cove; by 1847 there were “22 shanties, 31 frame houses, and 26 adobe dwellings.” City Engineer Jasper O'Farrell laid out the streets in checkerboard fashion, swinging De Haro's Calle de la Fundacion into line with the north-and-south streets, and extending the town's limits far beyond the district surveyed by Jean Vioget in 1839 (bounded by Montgomery, Dupont, Pacific, and Sacramento Streets)—westward to Leavenworth Street, north to Francisco, south to Post, and southeast beyond Market Street. The year 1848 marked the first building boom. According to The Annals of San Francisco, “A vacant lot…was offered the day prior to the opening of the [Broadway] wharf for $5,000, but there were no buyers. The next day the same lot sold readily at $10,000.” Long before lots could be surveyed, the area was “overspread with a multitude of canvas, blanket and bough covered tents,—the bay was alive with shipping…”

The community soon pushed eastward beyond the shore line, supporting itself with piles above the water and over rubble dumped into the tidal flats. Most of Commercial Street was then Long Wharf, built 2,000 feet into the Bay from Leidesdorff Street in 1850. A narrow plank walk, connecting Long Wharf with the Sacramento Street pier, was the beginning of Sansome Street. Into abandoned ships, dragged inland and secured from the tides, moved merchants and lodgers. Of these vessels, perhaps the most famous was the windjammer Niantic— one of the first to sail through the Golden Gate after 1849—abandoned by crew and passengers bound for the “diggin's.” Doors were cut, the hold was partitioned into warehouses, and offices were built on deck. When the superstructure was destroyed by fire in 1851, the Niantic Hotel (replaced in 1872 by the Niantic Block) was erected on the site (see plaque at NW. corner Clay and Sansome Sts.). Among other vessels claimed were the General Harrison, at the northwest corner of Clay and Battery streets, and the Apollo, at the northwest corner of Sacramento and Battery streets.

On Christmas Eve, 1849, fire destroyed the ramshackle city. By May 4, 1851, it had been burned five times. So reluctant were men to invest in San Francisco building enterprises that the East Bay enjoyed a tremendous growth. To restore local confidence, bankers and realtors combined to erect fire- and earthquake-proof buildings. First was the Parrott Block, built of granite blocks imported—cut and dressed—from China, on the present site of the Financial Center building at the northwest corner of Montgomery and California streets. Along Montgomery and adjoining streets arose a series of office buildings—solid, dignified, well-proportioned—which still remain.

The life of the town for more than three decades revolved around San Francisco's first “Civic Center,” Portsmouth Square—the Plaza of Mexican days. At its northwest corner stood Yerba Buena's government building, the adobe Customhouse, where Captain John B. Montgomery quartered his troops in 1846. Authorized by the Mexican Government in 1844, the four-room, attic-crowned structure with veranda on three sides, was not finished at the time. Soon afterwards occupied by the alcalde and the tax collector, it became the seat of city government. (From the beams of the south veranda, in 1851, the first Vigilance Committee hanged the thief, John Jenkins.) At the behest of the newcomers from the Portsmouth, Captain John Vioget, the town's first surveyor, changed the name of his Vioget House, the town's first hotel, to Portsmouth House. In the bar and billiard saloon of the wooden building, at the southeastern corner of Clay and Kearny streets, hung Vioget's original map. Across the Street on the southwest corner was the long, one-story adobe store and home of William Alexander Leidesdorff, the pioneer business man from the Danish West Indies, of mixed Negro and Danish blood, who was the American Vice-Consul under Mexican rule. At the first United States election held here on September 15, 1846, Lieutenant Washington A. Bartlett was chosen alcalde. Leidesdorff's house was transformed in November by John H. Brown into a hotel, later known as the City Hotel. On the west side of the Square was built in 1847 the first public schoolhouse, which soon served also as jail, courthouse, church, and town hall, grandiloquently called the “Public Institute.”

Around Portsmouth Square clustered in the early 1850’s the noisy saloons, theaters, and gambling houses of the city's first bawdy amusement zone. Not only the first public schoolhouse and the first hotel, but also the first theater faced the plaza : Washington Hall, on Washington Street along the north side, where the city's first play was presented in January, 1850. In the same block were built the Monumental Engine House No. 6, and the Bella Union Melodeon. The famous Maguire's

Opera House (see Social Heritage: Before the Footlights) rose on the east side of the Square. To the east, on the site of the present Hall of Justice, were the rowdy Eldorado gambling house and the Parker House, which became the Jenny Lind Theatre in 1850 and the first permanent City Hall two years later.Today the cradle of old San Francisco is a half-mile inland. Its ageing landmarks, hemmed in by Chinatown and North Beach on the north and west, by the financial and commission districts on the south and east, are all but overlooked. Persistent indeed must be the observer who can discover the few remaining landmarks of the vanished village of Yerba Buena.

Montgomery Street, the water front of ‘49, commercial artery of the roaring boom town, relaxed into a bohemian quarter long before 1906; artists’ Studios still occupy buildings which housed journalists and bankers, gamblers and merchants and bartenders, miners and sailors and stagecoach drivers. Realtors, printers, lawyers, and pawnbrokers occupy outmoded structures wherein their forbears speculated on fabulous “deals” in a boom era. Here, Chinese, Filipinos, Italians, Frenchmen, all sorts of Americans, still congregate and engage in business. But sailors from the seven seas gather no more on the slope of Portsmouth Square.

Something of the relative simplicity of the Argonauts—not the gaudy pretentiousness of their bonanza successors—survives in those old buildings with square cornices and simple facades, whose cornerstones were laid upon redwood piling and filled-in land during 1849 and the early 1850’s. A few bronze plaques here and there are all that identify San Francisco's memorable landmarks of the Gold Rush era. A few names of defunct firms, in obscure letters across weatherbeaten facades, tell legends which only those knowing the city's lore may fully comprehend. A few steep and narrow streets, a quiet plaza, an odor of decay, and a few scattered relics are all that remain of that once crowded area.

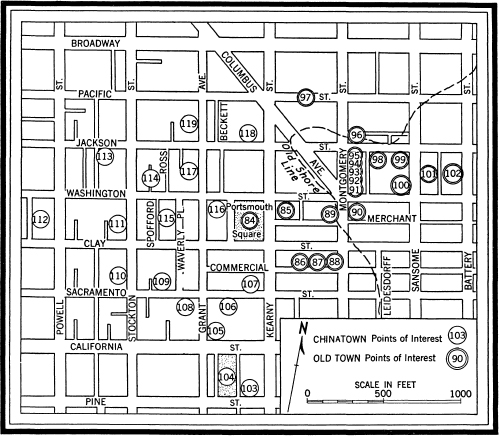

POINTS OF INTEREST

84. Upon the green, sloping lawns of PORTSMOUTH PLAZA, Kearny, Clay, and Washington Sts., Candelario Miramontes, who resided at the Presidio, raised potatoes in the early 1830’s. When the plot became a plaza is not known. Until 1854, when it was graded and paved, it had been graced only with a Speakers’ platform and a cowpen. Most of the stirring events from the 1840’s to the 1860’s took place here—processions, flag raisings, lynchings, May Day fetes. When news of the death of Henry Clay was received, all the buildings surrounding the plaza were draped in black. To hear Colonel E. D. Baker's funeral oration here for Senator David Broderick (fatally wounded in a duel September 13, 1859, by Judge David S. Terry) 30,000 people gathered. From 1850 to 1870 the Square was headquarters for public hacks and the omnibus which ran from North Beach to South Park. In 1873 crowds gathered to gape at Andrew Hallidie's pioneer cable car climbing the hill on its first trip from the terminus at Clay and Kearny streets. Before 1880 the Square ceased to be the center of civic gravity, as the business district moved south and west. Into abandoned buildings moved the Chinese on the west and north, the habitues of the Barbary Coast to the northeast, the residents of the Latin Quarter on the east. Here terrified Chinese ran about beating gongs to scare off the fire demons during the earthquake and conflagration of 1906; here came exhausted fire fighters to rest among milling refugees; here shallow graves held the dead; and thousands camped during reconstruction. The Board of Supervisors, in December, 1927, restored the square's Spanish designation of “plaza.”

Under the boughs of three slender poplars Stands the ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON MONUMENT, the first shrine ever erected to the memory of the man who sought the sunshine here in 1879. A simple granite shaft surmounted by a bronze galleon in full sail, the Hispaniola of Treasure Island (Bruce Porter, architect; George Piper, sculptor), the monument is inscribed with an excerpt from Stevenson's “Christmas Sermon.” Around it are clumps of purple Scotch heather.

Near the square's northwest corner, the MONTGOMERY FLAG POLE marks the site on which Captain John B. Montgomery first raised the United States flag, July 9, 1846. Erected in 1924 by the Daughters of the American Revolution, it has at its base a plaque inscribed in commemoration of the event.

85. On historic ground Stands the HALL OF JUSTICE, SE. corner Kearny and Washington Sts., facing Portsmouth Plaza. Here stood the famous Eldorado gambling house, and here, too, was Dennison's Exchange Saloon, where the first official Democratic Party meeting was held October 25, 1849, and where the first of the city's fires broke out two months later. Destroyed in this fire, the Parker House next door, built by Robert A. Parker and John H. Brown, was rebuilt—only to be twice burned again. Destroyed a third time in 1851, the year after Thomas Maguire had converted it into the Jenny Lind Theater, it was reconstructed. When a fifth fire reduced it to ashes in the same year, it was replaced by the third Jenny Lind Theater, built of stone. This the city purchased in 1852 for a City Hall (see Civic Center), to which it annexed the four-story building on the site of the Eldorado for a Hall of Records. Razed in 1895, the two buildings were replaced by the first Hall of Justice, which in turn was replaced after 1906 by the present somber gray-stone structure (Newton J. Tharp, architect), housing the city police department and courts, Superior Court criminal division, city prison, and morgue.

S. on Kearny St. to Commercial St., E. from Kearny on Commecrial.

86. “To take some worthy works that are in danger of extinction and perpetuate them in suitable form” is the aim of the GRABHORN PRESS, 642 Commercial St., as stated by Edwin Grabhorn. Since 1919 he and his brother Robert—whom the English book expert, George Jones, has declared the world's greatest printers—have been issuing their rare and valuable books in San Francisco. Of the books which first gave them renown, their edition of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass, illustrated with Valenti Angelo's woodcuts, is especially remembered. They have reproduced such items as New Helvetia. Diary. A record of events kept by John A. Sutter & his clerks, at New Helvetia, California, from September 9, 1845 to May 25, 1848 (1939); and Naval Sketches of the War in California, reproducing 28 drawings made in 1846-47 by William H. Meyers, gunner on the U.S. Sloop-of-war Dale (1939). Each year since 1919, at least one of their books (in 1939, three) has been chosen by the American Institute of Graphic Arts as one of the 50 best books published in the United States. The ground-floor office of the old two-story brick building is a repository of Grabhorn publications and historic photographs, prints, and posters dating from Gold Rush days.

87. The massive first-story walls of the UNITED STATES SUB-TREASURY BUILDING, 608 Commercial St., erected in 1875-77 on the SITE OF THE FIRST UNITED STATES BRANCH MINT, have resisted earthquake, fire, and dynamite. Of the original structure's three stories of red brick, erected over the mint's steel-lined vaults, only the first remains, now roofed over, its square red-brick columns crowned by weathered gray curlicues. The basement houses still the old vaults with their steel-lined walls and intricate locks.

Here, in what was the young city's financial district, the United States Government in 1852 purchased the property of Curtiss, Ferry and Ward, Assayers, for $335,000, and reconstructed the building as a fireproof, three-story brick structure. On April 3, 1854 San Francisco's first mint was opened, equipped to issue $100,000 worth of currency daily. By 1887 San Francisco had coined $242,000,000—almost half as much money as the Philadelphia mint had issued since 1793. As early as 1859, the first mint proved to be far too small; and, finally, the old building was razed, following completion of a second mint, in 1874.

In 1877 the new United States Subtreasury was opened on the site of the first mint. In April, 1906, the structure was dynamited in an effort to halt the flames. Unshaken by the blast, the 30-inch-thick first-story walls also withstood the fire, as did the basement vaults, which were crammed with $13,000,000 in gold. When, in 1915, the subtreasury was moved to its new building on the site of the San Francisco Stock Exchange, the old building was taken over by private firms.

88. At the heart of the old financial center Stands the B. DAVIDSON BUILDING, NW. corner Montgomery and Commercial Sts., whose first story was built soon after the fire of May 4, 1851 for merchant William D. M. Howard. A few years later, two more stories were added. On the walls of the first-floor tobacco shop are pictures of the structure taken in Gold Rush days. The iron vaults, where pioneer bankers stored their treasure, remain in the basement—so stoutly constructed that they long defied attempts to open them for the present owner.

In excavating a sewer along the Commercial Street side, in 1854, workmen uncovered a coffin with a glass-covered aperture in its lid, through which could be discerned a man's features. A coroner's examination revealed that the man was Hudson's Bay Company's agent, William Glenn Rae, son-in-law of Chief Factor John McLoughlin. Arriving at Yerba Buena in August, 1841, Rae opened his post in the store room, with $10,000 worth of goods. To rebels against Governor Manuel Micheltorena in 1844, he furnished $15,000 worth of stores and munitions. Worried over collapse of the revolt and fearing punishment, Rae took to drinking heavily. On January 19, 1845 be shot himself. He was buried in the garden outside his house.

When the Americans took California in 1846, the Hudson's Bay Company sold its property to the merchants and realtors, Mellus, Howard and Company. Seeing a prosperous future for San Francisco, the Rothschilds of London authorized Benjamin Davidson to open an agency for their banking firm. Of the five banking firms which, according to the Annals of San Francisco, were operating in the city at the end of 1849, three were situated on Leese's old 100-vara frontage—Davidson; Thomas Wells and Company; and James King of William. Early in 1850, when Long Wharf opened into Montgomery Street, the Hudson's Bay Company's old post was the United States Hotel.

When all of the old building but Leese's original adobe kitchen was destroyed by fire in 1851, William Howard had the room roofed with Australian bricks by Chinese laborers. Soon Howard erected a new brick structure (now the first story of the present B. Davidson Building), into which moved the Rothschilds’ agent.

N. from Commercial St. on Montgomery St.

89. Oldest business building in San Francisco is the BOLTON AND BARRON BUILDING, NW. corner Montgomery and Merchant Sts., a three-story fortress-like edifice, with rusty iron fire-escapes hanging wearily from its flat roof. Built in 1849, its brick and cast-iron walls withstood successive fires. Today, geraniums peep from boxes in the deep-set windows of upper-floor studio apartments, and a gaudy black-tile facade adorns the ground-floor tavern.

90. “Halleck's Folly” and “The Floating Fortress,” people called the four-story MONTGOMERY BLOCK, Montgomery, Merchant, and Washington Sts., when Henry W. Halleck (later General-in-chief of the Union Army) began building it in 1853. Wiseacres predicted it either would sink into the ooze of the tidelands or float across the Bay on its foundation of redwood logs. But the structure is still in good repair, though shorn of its heavy iron shutters, the carved portrait heads which adorned its facade, and the wrought-iron balcony which ran along its second story.

Conceiving of a building constructed upon military lines, Halleck consulted architect G. P. Cummings; together they drew up a design combining the principles of the fortress with those of the Florentine court: four connecting buildings around a courtyard. The four buildings were then linked by wrought-iron bands and adjustable turnbuckles inserted between the floor levels. The building defied every accepted principle of construction.

Dedicated as the Washington Block on December 23, 1853, it was the largest building on the Pacific Coast. It was popularly called the Montgomery Block, and its builders officially changed the name the following year. Within the year it was San Francisco's legal center, housing the city's first law library. Most of the Adams Express Company's gold bullion was placed in the basement vaults. The second floor housed a huge billiard parlor. Here were the offices of the Pacific and Atlantic Railroad, of the United States Engineers Corps, of the Alta California and the Daily Herald. For 30 years, the block housed the portion of Adolph Sutro's library (now in the San Francisco Public Library) that escaped the 1906 fire.

As James King of William lay dying in one of the rooms in 1856, prominent Citizens organized the Vigilance Committee that hanged his assassin, James P. Casey. King was shot in front of the Bank Exchange Saloon on the ground floor, where brokers did business until establishment of a stock exchange in 1862.

On that April morning in 1906, when flames were bearing down upon the block, soldiers stood powder kegs against the walls, ready to blast a fire-break. Oliver Perry Stidger, agent for the building, begged them to wait, appealing to their civic pride in an impassioned speech. Soon the danger had passed. Since this was the only downtown office building undamaged by the fire, it again became a center of business activity.

In the 1890’s various artists of the West had begun setting up their Studios in the Montgomery Block. With them came Frank Norris, Kathleen and Charles Norris, George Sterling, and Charles Caldwell Dobie. Known affectionately as the “Monkey Block” today, the old building consists largely of offices converted into Studios.

91. The SHIP BUILDING, 716-18-20 Montgomery St., supposedly owes its origin to the gold-seeking master and crew of the Georgean, who deserted her in the spring of ‘49. The schooner lay abandoned in the mud near Sansome Street, her cargo of Kentucky “Twist” (chewing tobacco) and New Orleans cotton molding and unsold, until a speculator claimed salvage rights and beached her on the present site. Today the supposed “foc'sle head” of the old schooner houses a Chinese laundry and a plumbing shop; the second floor, artist's Studios.

92. Gay blades haunted the MELODEON THEATER BUILDING, 722-24 Montgomery St., awaiting companions for a “bird-and- bottle” supper. Opening December 15, 1857, the Melodeon drew sea-faring men and miners, who delighted in its musical and minstrel shows. After the Melodeon closed about 1858, the hall was rented infrequently to various groups. Here in 1883, according to Disturnell's Strangers’ Guide to San Francisco and Vicinity, was the “extensive bathing establishment of Dr. Justin Gates…. Special apartments have been nicely fitted up for ladies and families.”

93. San Francisco's oldest sign, hanging from the GENELLA BUILDING, 728 Montgomery St., states in faded black and gold letters that “H. and W. Pierce… Loans and Commissions” once did business here, exchanging paper and coins for gold bullion. The structure was built about 1854 by Joseph Genella, who dealt in chinaware in an upstairs room. On the second floor the International Order of Odd Fellows had its first hall, where Yerba Buena Lodge No. 15 met every Thursday evening. Since the early 1920’s, the second floor has housed PERRY DILLEY'S PUPPET THEATER, which presents an annual season of performances, beginning usually in April. Dilley creates all of his own figures, designs and paints his sets, writes the musical scores, and re-writes classical and modern plays to suit his medium.

94. Named for the first of San Francisco's literary periodicals, the GOLDEN ERA BUILDING, 732-34 Montgomery St., housed on its second floor for more than two years the weekly established in December, 1852, by youthful J. Macdonough Foard and Rollin M. Daggett (see Golden Era: Argonauts of Letters). Its circulation among a Gold Rush populace, starved for reading matter, grew enormously. A “weekly family paper,” it was devoted to “Literature, Agriculture, The Mining Interest, Local and Foreign News, Commerce, Education, Morals, and Amusements.” On March 1, 1857, appeared a poem by an unknown author, “The Valentine”—first preserved published work of Bret Harte. Among other contributors were Ina Coolbrith, Thomas Starr King, Joaquin Miller, Mark Twain, and Charles Warren Stoddard. It survived nearly four decades. Beneath the Era's original offices, on the ground floor, was Vernon's Hall, rented to fraternal societies and theatrical troupes; today it houses a Chinese broom factory. The Era's old rooms are now artists’ Studios.

95. Disguised beneath its cream stucco finish and its gay red and blue canopies, the PIOCHE AND BAYERQUE BUILDING, SE. corner Montgomery and Jackson Sts., now occupied by an Italian restaurant, is the same structure that was erected in 1853 by the pioneer merchants and bankers, F. L. A. Pioche and J. B. Bayerque. It Stands on the SITE OF THE FIRST BRIDGE, a sturdy wooden structure—the town's first public improvement—which alcalde William Sturgis Hinckley constructed in 1844, over the long-vanished slough connecting the Laguna Salada (Sp., salty lagoon) with the Bay, thus enabling people to cross to Clarke's Point. In the Pioche and Bayerque Building were housed the offices of the city's first Street railroad, of which both Pioche and Bayerque were directors. Horses drew the first car up Market Street on July 4, 1860 (soon replaced by steam).

96. Not since 1857 has the LUCAS, TURNER AND COMPANY BANK BUILDING, NE. corner Montgomery and Jackson Sts., housed banking offices. When the firm of Lucas, Turner and Company, a branch of a St. Louis bank, desired property on which to erect its own building in 1853, William Tecumseh Sherman, then the resident manager and a partner in the firm, found (he later wrote) that “the only place then available on Montgomery Street, the Wall Street of San Francisco, was a lot…60 x 62 feet…” For this he paid $32,000, then contracted for “a three-story brick building, with finished basement, for about $50,000.” As manager of the new Institution, Sherman was overprudent. He refused to allow the occasional over-drafts his depositors demanded and declined to grant credit except on the soundest securities. Finally in 1857 the bank closed.

W. from Montgomery St. on Jackson St. to Columbus Ave.; NW. from Jackson on Columbus to Pacific St.; E. from Columbus on Pacific.

97. The “Terrific Street” of the 1890’s—that block of Pacific Street, SITE OF THE BARBARY COAST, running east from the once-famous “Seven Points” where Pacific, Columbus Avenue, and Kearny Street intersect—is set off now at each end by concrete arches labelled “INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENT.” As Barbary Coast it was known round the world for half a Century, more notorious than London's Limehouse, Marseilles’ water front, or Port Said's Arab Town. The enterprise of Pierino Gavello, restaurateur and capitalist, is today's “International Settlement,” developed in 1939, streamlined with the stucco facades and gleaming windows. Where gambling halls, saloons, beer dens, dance halls, and brothels once crowded side by side, a Chinese restaurant, a night club and cocktail bar, a Latin American cafe, and an antique shop now appear.

One resort of the old “Coast” remains in business—TAR'S, 592 Pacific St., the former Parente's saloon (newly painted and decorated), whose walls are still plastered from floor to ceiling with Parente's famous collection of prize-fight pictures—including champions from James Figg, bare-knuckle artist of 1719, to Joe Louis, 1940 title holder.

“Give it a wide berth, as you value your life,” warned the New Overland Tourist of Barbary Coast in 1878, describing “the precise locality, so that our readers may keep away.” Since the 1860’s it had worn the name Barbary Coast, derived probably from sailors’ memories of the dives of North Africa. But even in the early 1850’s, when the neighborhood was Sydney Town, inhabited by Australian outlaws known as “Sydney Ducks,” the “upper part of Pacific Street, after dark”—reported the San Francisco Herald—”was crowded by thieves, gamblers, low women, drunken sailors and similar characters…” The block bounded by Kearny, Montgomery, and Broadway was known as Devil's Acre, and its Kearny Street side as Battle Row (here stood the Slaughterhouse, later renamed the Morgue). The district contributed a new word, “hoodlum,” applying it to the young ruffians who roamed the “Coast” armed with bludgeons, knives, or iron knuckles (it is thought that the word comes from “huddle ’em!” the cry of the boys as they advanced on a victim). So too the expression “to Shanghai” originated here.

The employment of women in the “Coast's” resorts was strictly forbidden by law as early as 1869, but the “Coast” paid no heed. Besides the brothels of three types—cribs, cow-yards, and parlor houses, all advertised by red lights and some even by signboards—the district contained call houses, cheap lodgings patronized by street-walkers, bagnios over saloons and dance-halls, where variety show performers entertained between acts. Among the most renowned of the “Coast's” attractions in the 1870’s were the “Little Lost Chicken,” a diminutive girl who concluded her songs by bursting into tears (and picked the pockets of her admirers); the “Waddling Duck,” an immensely fat woman; “Lady Jane Grey,” who decked herself in a cardboard Coronet, convinced she was of noble birth; the “Dancing Heifer” and the “Gal-loping Cow,” whose sister act made the boards of the stage creak. “Cowboy Maggie” Kelly, a large blond known as “The Queen of the Barbary Coast,” was proprietress, and bouncer, of the Cowboy's Rest.

Wiped out in 1906, the Barbary Coast was revived for another decade of gaudy life. “The quarter did what every courtesan does who finds her charms and her following on the wane,” wrote Charles Caldwell Dobie. “It decided to capitalize its previous reputation, buy a new false front and an extra pot of rouge. The result was a tough quarter maintained largely for the purpose of shocking tourists from the Chatauqua circuit.” Almost every dance hall put on a good show for the benefit of gaping visitors in “slummers’ galleries.” “Take me to see the Barbary Coast,” said John Masefield—and he was taken, as was nearly every other visiting celebrity, including Sarah Bernhardt and Anna Pavlowa.

“The most famous, as well as the most infamous” of the resorts, reminisced photographer Arnold Genthe, “was the Olympia, a vast ‘palace’ of gilt and tinsel with a great circular space in the center and around it a raised platform with booths for spectators… Below us on the floor…a medley of degenerate humanity whirled around us in weird dance steps.” Of the same description was the Midway (down stairs at 587 Pacific Street)—a training ground for vaudeville acts—its walls decorated with large murals by an unknown Italian artist.

The Seattle Concert Hall (574 Pacific Street), later known as Spider Kelly's, first important resort to reopen after the fire, won local fame for its “key racket.” On the promise of keeping a rendezvous after work, the dance-hall girls sold, for five dollars, the keys to their rooms; the dupes wandered about until morning, vainly seeking doors their keys would fit. The “slummers’ gallery” of the Hippodrome (570 Pacific Street) was crowded nightly by visitors. Chief claim to fame of the Moulin Rouge (540 Pacific Street) were Arthur Putnam's sculptured panels on its facade, depicting figures of complete nudity until churchwomen forced the sculptor to drape the ladies.

No resort was better-known than Lew Purcell's So Different Saloon (520 Pacific Street), a Negro dance hall, where the “Turkey Trot” is said to have originated. The Thalia (514½ Pacific Street), on whose immense rectangular floor the “Texas Tommy” was first danced, lured patrons with a sidewalk band concert every evening. The Thalia's pièce de resistance was hootchy-kootchy dancer Eva Rowland.

But the Barbary Coast's assets as a tourist attraction did not out-weigh its liabilities as a crime center. The Police Commission's revocation of dance-hall licenses in 1913 was a hard blow, but the “Coast” recovered, and two years later licenses had to be revoked again. The Thalia went on operating as a dancing academy. Once more liquor permits were cancelled. As late as 1921, Police Chief Daniel J. O'Brien thought it necessary to forbid slumming parties in the area—but the Barbary Coast was dead.

S. from Pacific St. on Montgomery St. to Jackson St.; E. from Montgomery on Jackson.

98. Once noted for its paintings and well-stocked library, the iron-shuttered HOTALING BUILDING, SE. corner Jackson St. and Hotaling PI., housed the warehouses and stables of the Hotaling distillery. Narrow Hotaling Place, running south to Washington Street, was known as Jones’ Alley between 1847 and 1910. Loaded drays rumbled over the planked Street to the Broadway wharf; heavily guarded express coaches of the Wells Fargo and Company bore their cargoes to sailing ships; and under the dim gaslights silk-hatted dandies waited in hansom cabs for the beauties from the Melodeon. The Hotaling Building survived the fire of 1906 almost unscathed.

99. The hulls of abandoned ships were piled into the mud flats of Jackson Slough to make solid footing for the three-story brick PHOENIX BUILDING, SW. corner Jackson and Sansome Sts., which from 1858 to 1895 housed the factory of Domingo Ghirardelli, pioneer chocolate manufacturer (see Rim of the Golden Gate). Survivor of the 1906 fire, it hides its smoked and weathered facade under a thick coat of buff paint.

S. from Jackson St. on Sansome St.

100. Reared from the mud on a brick and pile foundation, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, NW. corner Sansome and Washington Sts., was constructed some time before 1853, when it was known as Armory Hall. The Golden Era in February of that year carried an advertisement of “Buckley's Original New Orleans Serenaders.” Known there-after as the Olympic Theater, the hall led, according to the Annals of San Francisco, “a brief and sickly existence.” After 1860, the building appeared in city directories as the “Government House Lodgings.” For a time Adolph Sutro lived in one of its furnished rooms.

Still illuminated by gas, Government House shows its age. The first floor was forced underground when Sansome Street was regraded early in the present Century; its basement rooms are now entered through narrow stairways leading from iron trap doors in the sidewalk. Shorn of its once ornate cornices, which began to crumble, the facade is shabby, its faded green paint and grey plaster cracked and peeling.

The oldest drugstore in the city, ALEXANDER MCBOYLE AND COMPANY, still housed on the ground floor of Government House, was opened in 1866. McBoyle, although not a dentist, managed to fill a window of his curious shop waist-deep with the extracted teeth of sea-farers. Grateful seamen repaid with curios and treasures from other lands and with ship models, painstakingly carved and fitted. While other druggists beckoned to the public with green and red globes, McBoyle drew three times the trade with a display of model ships sailing in the sea of teeth. He compounded for years the bulk of medicines shipped to the Orient. The present owners have retained a few faded pictures of sailing ships, and they sell Alexander McBoyle's “Abolition Oil,” to alleviate sprains and bruises, mixed according to the original formula.

101. Oldest structure still used by the Federal Government in San Francisco is the five-story brick and wrought-iron UNITED STATES APPRAISERS BUILDING, Sansome, Jackson, and Washington Sts., erected (1874-81) as one of the Army Engineer Corps’ most boasted construction achievements. Here, until after 1850, the tides lapped at the narrow row of piles marking the line of present Sansome Street. “Upon the head of these piles,” recalled Barry and Patten, “was nailed a narrow plank walk…without rail or protection of any kind…pedestrians passed and repassed in the dark, foggy nights, singing and rollicking, as unconcernedly as if their path was broad Market Street…”

On piles projecting eastward from what is now the corner of Sansome and Washington streets stood the wooden shanty where in August, 1850, Pedar Sather and Edward W. Church—joined nine months later by Francis M. Drexel of Philadelphia—opened a bank. When fire destroyed the structure, their safe fell into the water; it was fished up, however, and installed in a new building at the end of Long Wharf. (The only bank in the city founded as early as 1850 to see the twentieth Century, it was reorganized in 1897 as the San Francisco National Bank and finally absorbed by the Bank of California in 1920.)

Into the blue mud of the old cove bottom, Army engineers in 1874 began driving 80-foot piles, over which they laid a seven-foot thickness of “rip-rapped” concrete. On this foundation they erected the three-foot-thick walls of the Appraisers Building. The roof, fabricated of wrought iron in the manner of a truss bridge, rested on the outside walls, supporting a heavy slate covering. The 90 offices had hardwood doors and bronze hardware. The hydraulic elevator with ornately carved cage, installed in 1878, the first passenger elevator on the Pacific Coast, is still in use.

Having survived the 1906 earthquake, the building was threatened by the fire but saved by the Navy. From two tugs anchored below Washington Street, sea water was pumped through fire lines to save the old structure. In 1909, mud began to ooze from beneath its foundations into a sewer excavation along Sansome Street; the southwest corner sank 11 inches, but the structure remained intact.

In the Appraisers Building, dutiable imports were appraised and stored for payment of duty until 1940, when the structure was ordered razed to make way for a new 15-story building.

E. from Sansome St. on Washington St. to Battery St.; N. from Washington on Battery.

102. The UNITED STATES CUSTOMHOUSE (open 9-4:30), Battery, Washington, and Jackson Sts., has occupied this site for more than 75 years; but the block-long, five-story edifice of Raymond granite, its interior resplendent with marble and oak, erected (1906-11) at a cost of $1,600,000, is a far cry from the three-story customhouse and post office, built of cement-plastered brick in 1854, which stood here until 1903. The town's first customhouse on the Plaza was abandoned in 1849; it survived—its porch railings carved by the jacknives of Yankee newcomers—until 1851, outlasting the second, William Heath Davis’ four-story structure with its white-painted balconies, to which the collector of the port had removed his offices.

From the ruins of this second customhouse, nearly $1,000,000 in specie was rescued from a large safe, which had preserved it from the flames. The removal of the treasure by the collector of the customs, T. Butler King, “created some little excitement and much laughter,” as the Annals of San Francisco reported. “Some thirty gigantic, thick-bearded fellows, who were armed with carbines, revolvers and sabres, surrounded the cars containing the specie, while the Honorable T. Butler King stood aloft on a pile of ruins with a huge ‘Colt’ in one hand and a bludgeon in the other… The extraordinary procession proceeded slowly… Mr. King marching, like a proud drum-major, at the head…peals of laughter and cries of ironical applause accompanied the brave defenders of ‘Uncle Sam's’ interests to the end of their perilous march….”