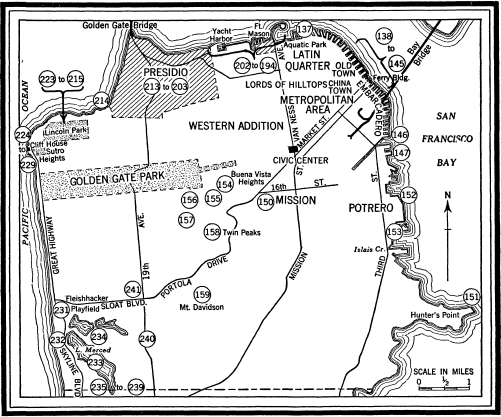

Embarcadero

“…that harbor so remarkable and so spacious that in it may be established shipyards, docks, and anything that may be wished.”

—FATHER PEDRO FONT (1776)

THE story of San Francisco is largely the story of its water front. As if it had grown up out of the sea, the original town clung so closely to the water's edge that one might almost have fancied its settlers—newly landed from shipboard, most of them—were reluctant to take to dry land. For years all the city's traffic passed up and down the long wooden wharves, sagging with business houses that ranged from saloons to banks. Many of the old ships lie buried now beneath dry land. Above the level of the tides that once lapped the pilings, streetcars thunder. Even old East Street, last of the water-front thoroughfares, has gone the way of the sailing vessels which once thrust proud figureheads above the wharves’ wooden bulkheads. Around the Peninsula's edge, from Fisherman's Wharf to China Basin, sweeps the paved crescent of the 200-foot-wide Embarcadero, lined with immense concrete piers. Where the four-masters and square-riggers once disembarked, cargo-ships and luxury liners rest alongside vast warehouses, unloading their goods from all the corners of the earth.

By night the Embarcadero is a wide boulevard, dimly lighted and nearly deserted, often swathed in fog. Its silence is broken by the lonely howl of a fog siren, the raucous scream of a circling seagull, or the muffled rattle of a winch on a freighter loading under floodlights. The sudden blast of a departing steamer, the far-off screech of freight-cars being shunted onto a siding by a puffing Belt Line locomotive shake the nocturnal quiet. The smells of copra, of oakum, raw sugar, roasting coffee and rotting piles, and mud and salt water creep up the darkened streets.

Even before the eight o'clock wail of the Ferry Building siren, the Embarcadero comes violently to life. From side streets great trucks roll through the yawning doors of the piers. The longshoremen, clustered in groups before the pier gates, swarm up ladders and across gang-planks. The jitneys, small tractor-like conveyances, trailing long lines of flat trucks, wind in and out of traffic; the comical lumber carriers, like monsters with lumber strapped to their undersides, rattle along the Street. Careening taxis, rumbling underslung vans and drays, and scurrying pedestrians suddenly transform the water front into a traffic-thronged artery.

Street Scenes

CALIFORNIA STREET STILL CHALLENGES THE CABLE CAR

CHINESE NEW YEAR CELEBRATION

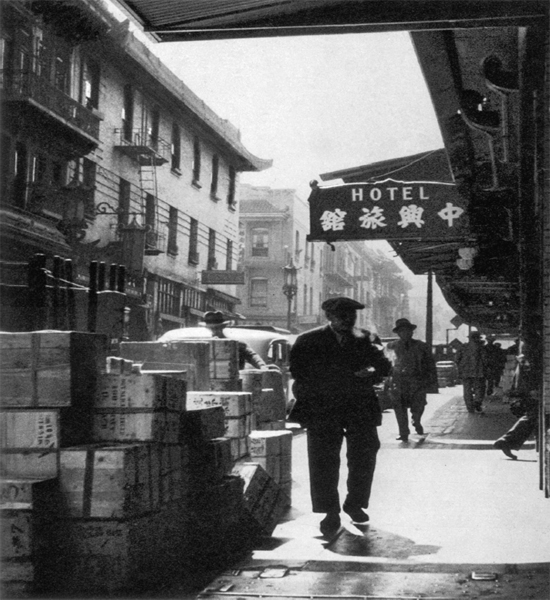

CHINATOWN

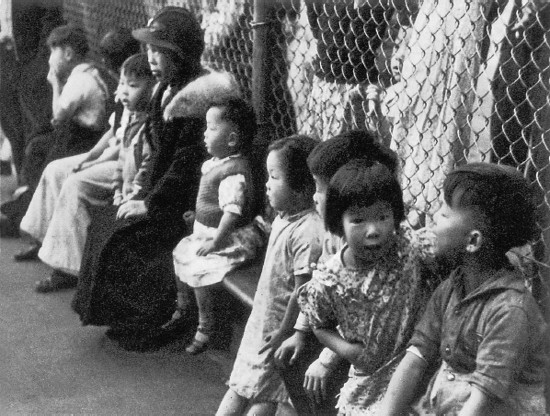

CHINESE CHILDREN AT THANKSGIVING PLAYGROUND PARTY

GRANT AVENUE

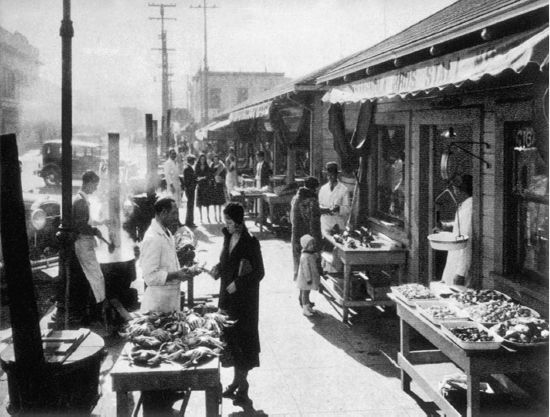

FISHERMAN'S WHARF

SS. PETER AND PAUL CHURCH

PACIFIC UNION CLUB, MARK HOPKINS AND FAIRMONT HOTELS ON NOB HILL

TELEGRAPH HILL FROM THE PRECIPITOUS SIDE

OCTAGONAL HOUSE ON RUSSIAN HILL, BUILT IN 1854

PACIFIC HEIGHTS

A never-ending stream of vehicles brings the exports of the Bay area and the West and the imports of both the hemispheres. Stored in the Embarcadero's huge warehouses are sacks of green coffee from Brazil; ripening bananas from Central America; copra and spices from the South Seas; tea, sugar, and chocolate; cotton and kapok; paint and oil; and all the thousand varieties of products offered by a world market. Here, awaiting transshipment, are wines from Portugal, France, and Germany; English whisky and Italian vermouth; burlap from Calcutta and glassware from Antwerp; beans from Mexico and linen yarn from northern Ireland.

North of the Ferry Building dock the vessels of foreign lines. Here, too, are berths for many of the old stern-wheelers, and of barges and river boats of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers which bring to San Francisco the products of central California's great agricultural plains.

South of the Ferry Building dock the big transpacific passenger ships. Near China Basin are several piers from which sail the around-the-world boats of the American President Line (formerly Dollar Lines). Sailing and docking days bring a fleet of taxis to the pier head with flowers, passengers, and dignitaries. When the Pacific Fleet is anchored in Man-o’-War Row, the bluejackets disembark from the tenders at Pier 14.

Around China Basin and the long narrow channel extending inland from the Embarcadero's southern end are railway freight yards, warehouses, and oil and lumber piers. Of the bridges that span the channel, most important is the trunnion bascule lifting bridge at Third and Channel Streets, built in 1933, one of the largest of its type. On the south side of the channel entrance are the Santa Fe Railway Company's wharves, with a mechanically adjustable ramp that can be raised or lowered with the level of the tide. To adjoining piers are moored many large purse-seiners, driven south by winter storms, whose home ports include such places as Chignik, Nome, Sitka, Juneau, and Gig Harbor. Fishing in southern latitudes during winter, they utilize San Francisco as their base.

Busiest section of the Embarcadero is the stretch between the Ferry Building and the Matson Line docks. Opposite the great concrete piers is a string of water-front hotels, saloons, cafés, billiard parlors, barber shops, and clothing stores. The one sail loft which remains has turned long since to making awnings. In the block between Market and Mission Streets the atmosphere of the old water front lingers in the saloons, lunch rooms, and stores where seafaring men and shore workers gather.

As on most American water fronts, store windows are stuffed with dungarees, gloves, white caps, good luck charms, cargo hooks, and accordions. A tattoo artist decorates manly arms and chests with glamour girls, cupids, and crossed anchors. Gone today are the bum-boatmen, who once climbed aboard incoming ships from rowboats with articles to sell; but peddlers patrol the Embarcadero, some pushing carts with candy and fruits, mystic charms and shoestrings, lottery and sweepstakes tickets. In many cafes or saloons a longshoreman can cash his “brass,” the small numbered metal token given him for presentation at the company pay windows. For cashing it, the charge is usually five cents on the dollar.

Scalers, seamen, longshoremen, warehousemen—all have their hiring halls and union headquarters in the small area bounded by the Embarcadero, Market, Clay, and Drumm Streets, known to seafaring men and dock workers as the “Front.” Here the men congregate between shifts and between jobs awaiting their turn for new jobs handed out through union dispatchers. Their talk is interminably of union contracts, politics, jobs, lottery tickets, and horse racing. From the various hiring halls the men are sent out, the longshoremen sometimes hurrying to docks and ports as far away as Crockett in Contra Costa County and the seamen packing their suitcases of working “gear” to the ships. All dispatching is done by rotation: this is the hiring hall system for which the men fought in the 1934 maritime strike.

The longshoremen with their white caps and felt hats, their black jackets and hickory shirts, their cargo hooks slung in hip pockets, outnumber the workers of any other craft in the maritime industry. As soon as a ship is tied up, they go aboard, and as the winches begin to rattle, unloading is under way. The jitney drivers pull up alongside with their trucks; checkers keep track of every piece of cargo. Meanwhile, ship scalers are aboard cleaning out empty holds, boiler tubes and fire boxes, painting sides and stacks, scraping decks, and doing the thousand jobs required to make a vessel shipshape.

The produce commission district, a stone's throw from the water front in the area bounded by Sacramento, Front, Pacific, and Drumm Streets, also bustles with activity in early morning. A district of narrow streets lined with roofed sidewalks and low brick buildings, it is the receiving depot for the fresh produce that finds its way into the kitchens, restaurants, and hotels of the city. Long before daybreak—in the summer, as early as one o'clock—trucks large and small begin to arrive from the country with fruits and vegetables. From poultry houses come the crowing and cackling of fowls aroused by the lights and commotion. The clatter of hand-trucking and a babel of dialects arise. About six o'clock the light delivery trucks of local markets begin to arrive. By this time a pedestrian can barely squeeze past the crates, hampers, boxes, and bags along the sidewalks.

The stacks of produce dwindle so rapidly that by nine o'clock the busiest part of the district's day is over. Then come the late buyers, known as “cleaners-up,” to take advantage of lowered prices; street peddlers with dilapidated trucks, and poverty-stricken old men and women, carrying bags, to search the gutters for fruit and vegetables dropped or flung away. By afternoon this district is almost deserted.

“San Francisco is the only port in the United States,” reports the United States Board of Engineers for Rivers and Harbors, “where the water front is owned and has been developed by the State, and where also, the public terminal developments have been connected with one another and with rail carriers by the Belt Line, owned and operated by the State.” In 1938, the State Board of Harbor Commissioners, celebrating its control of the water front since 1863, reported the port of San Francisco had “43 piers available for handling general cargo; 17.5 miles of berthing space; 193 acres of cargo space; terminals and warehouses for special cargo—a grand total of 1,912 acres owned by the State of California. A shipside refrigeration and products terminal equipped with modern facilities for handling and storing agricultural products and perishable commodities in transit; a grain terminal for cleaning, grading and loading grain for export; special facilities for the promotion and development of the fishing industry at Fisherman's Wharf; tanks and pipelines for handling Oriental vegetable oils and molasses; fumigating plants for cotton; lumber terminals. The entire water front and adjacent warehouses and industries are served by the State Belt Railroad, which has 66 miles of track and direct connection with all transcontinental and local railroads…. The Port's ensemble of wharves, piers, terminals and commercial shipping facilities virtually as they exist today, have been constructed during the last 28 years and are valued at close to $42,000,000. All the facilities of the port are appraised at $86,000,000.”

Before there was an Embarcadero the shoreline of a circling lagoon swept inward from Clark's Point at the base of Telegraph Hill and outward again to Rincon Point near the foot of Harrison Street. From August, 1775, when Lieutenant Juan Manuel de Ayala first sailed the San Carlos through the Golden Gate until September, 1848, when the brig Belfast docked at the water-front's first pile wharf, cargoes were lightered from vessel to shore. The favored landing place was Clark's Point, the small, rocky promontory sheltering Yerba Buena Cove on the north, first known as the Punta del Embarcadero (Point of the Landing Place). Here in September, 1847 William Squires Clark persuaded the Town Council to authorize construction of a public pier (see bronze plaque on wall of Montevideo and Parodi, Inc. Building, 100-110 Broadway). Sufficient only to pay for the pier's foundations, the $1,000 appropriated was exhausted by the following January. In 1848 the Town Council agreed to appropriate $2,000 more for continuance of the work. This, when completed, was the first wharf built on piles on the Pacific Coast north of Panama.

“The crowd of shipping, two or three miles in length, stretched along the water…” wrote globe-trotter Bayard Taylor before the end of 1849. “There is probably not a more exciting and bustling scene of business activity in any part of the world, than can be witnessed on almost any day, Sunday excepted, at Broadway Street wharf, San Francisco, at a few minutes before 4 o'clock p.m. Men and women are hurrying to and fro; drays, carriages, express wagons and horsemen dash past.… Clark's Point is to San Francisco what Whitehall is to New York.”

First wharf for deep-water shipping was Central or Long Wharf, built along the line of Commercial Street, which by the end of 1849 had been extended to a length of 800 feet. It was used by most of the immense fleet of vessels from all the world which anchored in the Bay in the winter of 1849-50. By October, 1850, an aggregate of 5,000 feet of new wharves had been constructed at an estimated outlay of $1,000,000. The wharf building was accomplished in haphazard fashion. Not until May 1851, when the State legislature passed the Second Water Lot Bill, was the city empowered to permit construction of wharves beyond the city line. No less than eight wharves, however, had been built by this time. Nearly one half of San Francisco rose on piles above water. The moment a new wharf was completed, up went frame shanties to house a gambling den, provision dealer, clothing house, or liquor salesman.

Soon, however, more substantial structures were being erected. Of these, perhaps the most famous was Meiggs’ Wharf, built by Henry Meiggs in 1853. From the water line (then Francisco Street) at the foot of Mason Street, Meiggs’ L-shaped pier, 42 feet wide, ran 1,600 feet north to the line of Jefferson Street and 360 feet east. Long after its builder had absconded to Peru (where he made a fortune building a railway through the Andes), following discovery of his embezzlement of $800,000 in city funds, the wharf was a terminal for ferryboats plying to Alcatraz and Sausalito. From the foot of Sansome Street, in the shadow of Telegraph Hill, ran the North Point Docks, built in 1853, where for many years landed most of the city's French and Italian immigrants.

The ten-year leases under which most of the important wharves operated expired in 1863—and in that year was appointed a State Board of Harbor Commissioners, which refused to grant renewals. Not until 1867, because of litigation with wharf-owners, was the board able to proceed with harbor development. A channel 60 feet wide was dredged 20 feet below low tide level, in which loads of rock dumped by scows and lighters were piled up in a ridge reaching the level of mean low tide. On top of the embankment were laid a foundation of concrete and, on top of the concrete, a wall of masonry. But the protracted litigation with water-front property owners, the decline in shipping caused by competition of the newly completed transcontinental railroad, and the grafting of private contractors who had undertaken to build the sea wall—all combined to hold up the work. Within two years after construction had been resumed in 1877, a thousand feet of the wall west of Kearny Street had been completed. From the scarred eastern flanks of Telegraph Hill, long lines of carts transported rock. In the course of construction, tons of rock were gouged from the hill's slopes, and tons more (more than 1,000,000) were ferried from Sheep Island, off Port Richmond. Not until 1913 was the sea wall finally completed.

The Belt Line Railroad was first debated in 1873, but not until 1890 was a mile-long line with a three-rail track built for both narrow-and standard-gauge cars. At first confined to the section north of Market Street, the road was extended southward in 1912 to link the entire commercial water front with rail connections to the south and thereafter westward through the tunnel under Fort Mason to the Presidio and southward to Islais Creek Channel.

Revolutionary as the port's physical changes have been in the past century, no less marked have been the differences wrought in the lives of the men who earn their livelihood on its ships and shores. During the years after ‘49, “the Front” gained the reputation of being one of the toughest spots in the world. In the last half of the century the shortage in sailors was so great that kidnapping or “shanghaiing” was practiced. The very expression “shanghaiing” originated in San Francisco in the days when voyages to Shanghai were so hazardous that a “Shanghai voyage” came to mean any long sea trip.

Notorious among the crimp joints of the 1860’s was a saloon and boarding house conducted on Davis Street by a harridan named Miss Piggott. Here operated one Nikko, a Laplander whose specialty was the substitution of dummies and corpses for the drunken sailors the ships’ captains thought they were hiring. Miss Piggott had a rival in Mother Bronson, who ran a place on Steuart Street, She would size up a likely customer, smack him over the head with a bung-starter, and drop him through a trap door to the cellar below where he awaited transfer to a ship.

Shanghai Kelly, a red-headed Irishman who ran a three-story saloon and lodging house at 33 Pacific Street, was probably the most notorious crimp ever to operate in San Francisco. The tide swished darkly beneath three trap doors built in front of his bar. Beneath the trap doors, boats lay in readiness. Kelly's most spectacular performance came in the middle 1870’s. Three ships in the harbor needed crews. One was the notorious hell-ship Reefer, from New York. Kelly engaged to supply men. He chartered the paddle-wheel steamer Goliath and announced a picnic with free drinks to celebrate his “birthday.” The entire Barbary Coast responded. Once in the harbor, Kelly fed his guests doped liquor, pulled alongside the Reefer and the other two ships, and delivered more than 90 men.

During the 1890’s six policemen sent successively to arrest a Chilean, Calico Jim, were kidnapped in turn and put aboard outward bound boats. Ultimately, all six returned to San Francisco, swearing vengeance. The crimp had gone to South America. The policemen raised a fund and sent one of their number to Chile to wreak vengeance. Having found Calico Jim, he pumped six bullets into him, one for each policeman, and returned to duty.

The most famous runner for sailors’ boardinghouses was Johnny Devine, the “Shanghai Chicken,” who had lost his hand in some scrap and had replaced it with an iron hook. Devine was a burglar, footpad, sneak thief, pimp, and almost everything else disreputable. His favorite stunt was to highjack sailors from other runners.

Of all that lively collection of crimps, highjackers, burglars, pimps, and ordinary rascals, the least vicious—if not the least dangerous—seems to have been Michael Conner, proprietor of the Chain Locker at Main and Bryant Streets. Deeply religious, he boasted of never telling a lie. When ships’ captains came seeking able seamen, Conner could swear that his clients had experience—for he had rigged up in his backyard a mast and spars whereon his “seasoned sailors” were put through the rudiments. On the floor of his saloon was a cow's horn, around which Conner would make the seamen walk several times so that he might truthfully say they had been “round the Horn.”

The Embarcadero's reputation for toughness rapidly is being woven into legend, along with the doings of the pioneers. San Francisco's water front is no longer a shadowy haunt, full of unsuspected perils. Today, it occupies a place in the forefront of the city's industrial, commercial, and social life. The water-front men take an informed interest in civic affairs—and many of them own comfortable homes out on the avenues.

POINTS OF INTEREST

137. The MARINE EXCHANGE LOOKOUT STATION, Pier 45, Embarcadero and Chestnut St., whose glassed-in, hexagon-shaped cubicle, equipped with a powerful telescope, commands a sweeping view of the Golden Gate, has been called “The Eyes of the Harbor.” At the dock below lies the launch Jerry Dailey, ready to carry its crew of old-timers through the Gate to meet incoming vessels whenever telephonic reports from the Marine Exchange's other lookout station at Point Lobos announce that a vessel has been sighted on the horizon. The lookout delivers mail and instructions for docking, receives cargo statistics, running time, and other marine news. Returning to the station, he telephones the information to the Marine Exchange, where news of the ship's arrival is listed on the blackboards.

Since its organization in 1851, the Marine Exchange has kept its day-and-night watch for inbound ships, at first with the aid of the lookout station erected by Messrs. Sweeney and Baugh in 1849 on Telegraph Hill, to which signals were relayed from the Point Lobos lookout.

138. A relic of the old days is FLINT'S WAREHOUSE, Filbert, Battery, and Sansome Sts., built in 1854 when the Bay washed at the piles of the Battery Street wharf. Originally two stories high, it was constructed of stone torn from near-by Telegraph Hill; but when the tide lands were filled, the first floor became the basement. Loading beams that served the sturdy square-rigged sailing ships of the 1850’s still hang above the Battery Street doorways. Today, the venerable structure, steel-braced and patched with variegated brick but still equipped with its ancient red iron shutters, is a storage plant for automobiles.

139. One police boat, the D. A. WHITE, moored at Pier 7, serves the entire San Francisco water front. It is a 66-foot, shallow-keeled vessel powered by two Diesel motors of 190 horsepower each which develop a speed of 16 knots; its two-way radio enables it to keep in contact with the Harbor Police Station, under whose jurisdiction it operates. Chief duties include rescuing amateur yachtsmen from the mud flats and grappling corpses from the murky waters of the Bay.

140. The HARBOR POLICE STATION, NE. corner Drumm and Sacramento Sts., a compact, two-story, gray stone building, is headquarters for police control over the water-front area. One of its main concerns is thievery on the docks, commonly known as “poaching the cargo.”

141. The HARBOR EMERGENCY HOSPITAL, 88 Sacramento St., is largely a field hospital for derelicts. Here, prisoners from the City Jail and water-front “sherry bums,” as well as injured sailors and longshoremen receive treatment in two twelve-bed emergency wards. The present hospital, at this location since 1926, is staffed by a surgeon, nurse, steward, and ambulance driver. Its equipment includes a Drinker respirator for use in drowning cases.

142. The oldest maritime organization on the Pacific Coast has its headquarters at the BAR PILOTS STATION, Pier 7, Embarcadero and Broadway; for 90 years, from 1850 to 1940, the San Francisco Bar Pilots have been steering vessels over the San Francisco bar and through the Golden Gate to anchorage in the Bay. All master mariners, the 20 pilots are former sea captains of long experience on the Pacific Coast. They maintain three auxiliary schooners as pilot boats, each of which carries an engineer, a boat keeper, a cook, and three sailors. Day and night one of these vessels stands by, about six miles off the Golden Gate, with sails spread to keep an even keel in high seas. During its five days at sea, the crew is on constant call. To the schooner at sea, the shore station reports ship movements by means of a wireless telephone system—the only one in the world maintained by a pilotage service. Whenever an approaching vessel requires a pilot, the schooner is brought around to its lee. In a small boat the pilot is rowed over to the inbound ship. On the bridge of the vessel, he takes charge, steering a safe course into the harbor. Under the jurisdiction of the State Pilot Commission, the bar pilots are obliged to keep a 24-hour watch on the bar and to provide pilotage service without undue delay to any ship requesting it.

143. More universally accepted as a symbol of San Francisco than any other single landmark, the FERRY BUILDING, Embarcadero and Market St., has served to identify the city in the minds of countless travelers throughout the world. Before the completion of the two bridges across the Bay, this was the gateway to San Francisco, its high clock tower the most conspicuous feature of the skyline to passengers on the lumbering ferries which churned the waters for nearly nine decades. In the years immediately preceding the opening of train service across the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, the long hallways of the historic structure echoed to the footsteps of as many as 50,000,000 passengers in a single year—a volume of traffic exceeded only by Charing Cross Station in London. For 40 years the flower stand on the ground floor was a favored rendezvous where San Franciscans met visiting friends in the midst of a hubbub of talk, newsboys’ shouts, slamming taxicab doors, and rumbling streetcars. Now the stairways and corridors are all but deserted, since only overland railroad passengers and Treasure Island pleasure-seekers come and go from the ferry slips.

Erected by the State Board of Harbor Commissioners (1896-1903) on a foundation of piles beyond the edge of the original loose-rock sea wall, the Ferry Building was hailed at its opening in July, 1898 as the most solidly constructed edifice in California. It was built to replace the old Central Terminal Building erected in 1877, a wooden shed over the three ferry slips operated by the Central Pacific, Atlantic and Pacific, and South Pacific Coast Railways, when the volume of traffic across the Bay dictated an improvement in terminal facilities.

Architect Arthur Paige Brown designed a two-story building with an arcaded front extending along the water front for 661 feet. The clock tower, rising 235 feet above the ground—a respectable height in its day—was modeled after the famous Giralda Tower of Spains’ Cathedral of Seville. Like the rest of the building, it was faced with gray Colusa sandstone until the 1906 earthquake shook off the stone blocks and they were replaced by concrete. Into the grand nave extending the whole length of the building on the second floor lead corridors giving access to the upper decks of the ferryboats.

For a year after April 18, 1906, the great hands of the clock dials on the tower pointed to 5 :17—the time at which the earthquake struck. When first installed, the clock was operated by a long cable wound on a drum, and a 14-foot pendulum; it has since been equipped to run by electricity. Each of the four 2,500-pound dials on the four sides of the tower measures 23½ feet in diameter; each of the numerals, 2½ feet in height. The hour hands are 7 and the minute hands 11 feet long.

Extending the entire length of the grand nave on the second floor is a PANORAMA MAP in relief of the State of California, modeled from United States Geological Survey maps by 25 artists, engineers, electricians, and carpenters, who spent two years (1923-25) fabricating it from cardboard, magnesite, and paint at a cost of $100,000. An automatic electric control regulates a lighting system simulating daylight, sunrise, and sunset and operates a miniature Mount Lassen in eruption. The map is 600 feet long and 18 wide, on a scale of 6 inches to the mile. It is backed by a cyclorama of the Sierra Nevada.

Opposite a huge mosaic of the Great Seal of California in the floor of the nave is the mezzanine stairway leading to the CALIFORNIA STATE MINING BUREAU MINERAL MUSEUM (open Mon.-Fri. 9-5, Sat. 9-12), its laboratory, and the John Hammond Mining Library of 9,000 volumes. The museum, fifth largest of its type in the United States, contains specimens of minerals from every part of the world, facsimiles of all of the important nuggets unearthed in California, and models of gold and diamond mines and ore crushers. The institution has been supported by the State and by individual contributors ever since its inception in 1897. J. C. Davis, member of the first board of trustees, has been the principal donor.

Flanking the main entrance to the Ferry Building are two short SECTIONS OF BAY BRIDGE CABLES, the Golden Gate Bridge section to the north and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge section to the south.

144. From the NAVY LANDING, Pier 14, Embarcadero between Mission and Howard Sts., launches ply back and forth between landing stage and shipside, transporting crowds of blueclad Navy men and sightseeing visitors, whenever the United States Pacific Fleet is tied up along “Man-o’-War Row.”

145. Alongside the two-story engine house of the EMBARCADERO FIRE DEPARTMENT, Pier 22, Embarcadero between Folsom and Harrison Sts., are anchored one of the harbor's two gleaming red and black, brass-trimmed fire boats, and one of its two auxiliary tugs. The harbor firefighting unit of 23 men is maintained jointly by the State Board of Harbor Commissioners and the city. The fire boats are each equipped with monitor batteries, more than 5,000 feet of hose, and water towers which can be raised to a height of 55 feet above deck. They respond to emergency calls from all parts of the Bay and its islands.

146. Overlooking the China Basin Channel, the STATE REFRIGERATION PLANT, between Embarcadero and Third Sts., offers storage and transfer facilities for immense quantities of fresh fruit and vegetables awaiting shipment to foreign markets. In the refrigeration plant's 450,000 cubic feet of space, more than 200,000 packages of fruit can be precooled simultaneously. The fruit is unloaded from trucks on a second-floor platform along the land side and loaded aboard ship from a platform on the water side.

147. At the UNITED FRUIT COMPANY DOCKS, south side of China Basin Channel west of Third St. Bridge, one of the fruit company's banana boats from Central America ties up each Thursday. Occasionally, a frightened monkey or small boa constrictor, half frozen from long hours in refrigerated hatches, comes out of the dark with the fruit. The firm operates three freight and passenger steamships between San Francisco and Puerto Armuelles, Panama. Of Danish registry, the vessels are specially constructed for transporting bananas, each having a cargo capacity of 60,000 stems. The unloading equipment on the pier includes electrically operated traveling conveyors and belts. Issuing from the vessel's holds in endless streams, the banana stems are sorted according to degrees of ripeness and then loaded into refrigerator cars. The capacity of the unloading equipment is 30,000 stems in eight hours.