East Bay: Cities and Back Country

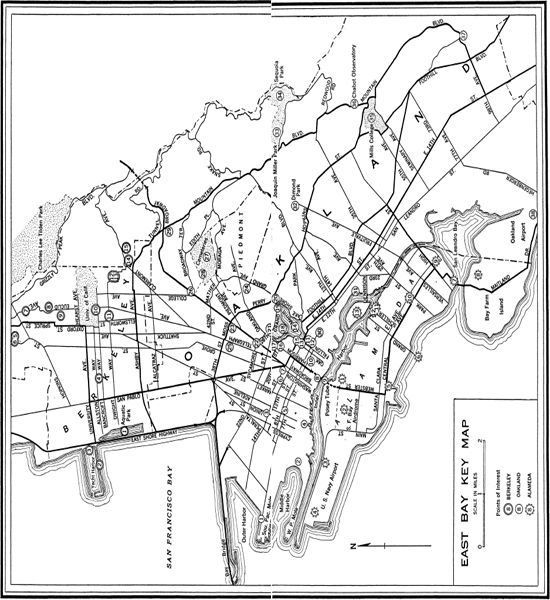

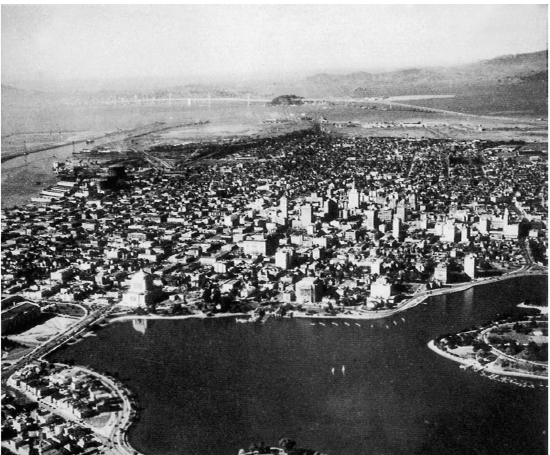

IN SPANISH times the distant shoreline opposite the Golden Gate was “la contra costa” (the opposite coast), to the conquistadores. Today between the shimmering cables and steel girders of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, the eastward traveler sees a continuous panorama of home and industry, extending north and south with hardly a break and almost to the crest of the wooded hills in the background. The “opposite coast” is now the East Bay, a heterogeneous urban area comprising ten municipalities in two counties. The bridge is itself both a practical and a symbolical evidence of its close relationship to the other metropolitan areas on the western shore.

The hills seem to recede as the traveler speeds down the eastern half of the bridge: he sees a flat rectangular strip of land on which most of the industrial and business sections of the East Bay rest, as on a stage to which the residential hills are the backdrop. Ahead and to the right are the tall buildings of downtown Oakland, key city of the area, where the industrial district crowds down to the Outer Harbor in the foreground. Across the water to the far right a ferryboat dock—reminiscent of a vanishing era in Bay transportation—affords the only glimpse of Alameda, the island city. Far to the southeast, beyond the traveler's range of vision, are San Leandro and Hayward. Although the vast panorama of homes and business buildings shows no visible gaps, it is a jig-saw puzzle of independent communities closely fitted together—Piedmont, a residential community in the hills almost directly ahead; Emeryville, an industrial town crowding to the shore in the left foreground; Berkeley to the left, best identified by the white campanile and stadium on the university campus, spreading up the slopes beyond; El Cerrito, and Richmond, residential and industrial towns far to the left. With a combined population of over a half-million, these municipalities form a continuous urban unit, yet maintain their political independence.

Its scenic attractions and garden climate—slightly more extreme in summer and winter than San Francisco's—make the East Bay the family homesite of more than 30,000 commuters, who ebb and flow daily across the bridge to business and professional offices. The panoramic setting of the entire Bay region is nowhere better seen than from the Grizzly Peak and Skyline Boulevards, which follow the crest of the hills above Berkeley and Oakland. With impressive authority, a noted traveler has Cited this tour as “the third most beautiful drive in the world.” It follows for a distance the boundary line between the two counties which share the east side of the Bay—Alameda and Contra Costa, the old Spanish name having adhered to the latter, although its meaning is generally lost on the monolinguistic inheritors of the ranchos.

Oakland

Information Service: Oakland Tribune, 13th and Franklin Sts. Chamber of Commerce, 14th and Franklin Sts. Dep't of Motor Vehicles, 1107 Jackson St. California State Automobile Assn., 399 Grand Ave. Alameda County Development Commission, County Courthouse.

Railroad Stations: Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe. Ry., San Pablo Ave. and 40th St. Sacramento Northern Ry., Shafter Ave. and 40th St. Southern Pacific R. R., W. end of 16th St. and Broadway and 1st St. Western Pacific R. R., Washington and 3rd Sts.

Bus Stations: Greyhound and Peerless Lines, Union Stage Depot, 2047 San Pablo Ave. Santa Fe and Burlington Trailways, 1801 Telegraph Ave. All American Bus Lines, 1901 San Pablo Ave. Dollar Lines, 2002 San Pablo Ave.

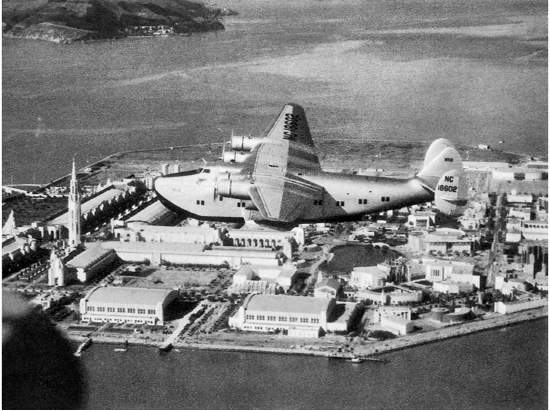

Airports: Oakland Municipal Airport, Bay Farm Island, for United Air Lines (about Jan., 1941 base will be moved to San Francisco) and TWA. Treasure Island for Pan-American Airways.

Taxis: Average rates 20¢ first ¼ m., 10¢ each additional ½ m.

Streetcars and Buses: East Bay Transit Co. to all points in Oakland, Berkeley, and Alameda, 10¢ or one token (7 for 50¢); to Hayward, El Cerrito, or Richmond 20¢ or 2 tokens; transfers free. Transbay electric trains to San Francisco, 21¢.

Bridge: San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge approaches: 38th and Market Sts. and 8th and Cypress Sts.; toll 25¢, 1 to 5 passengers.

Traffic Regulations: Speed limit 25 m.p.h. in business and residential areas, 15 m.p.h. at intersections. Parking limit 40 min. in business district. No all-night parking.

Accommodations: Eight medium-priced hotels downtown; apartment hotels; Y.M.C.A., 2501 Telegraph Ave.; Y.W.C.A., 1515 Webster St.; eight tourist camps.

Radio Stations: KLX (880 kc.), Tribune Tower; KLS (1280 kc.), 327 21st St.; KROW (930 kc.), 464 19th St.

Concert Halls: Auditorium Theater, Civic Auditorium; Women's City Club.

Motion Picture Houses: Five first-run theaters downtown.

Amateur and Little Theaters: Oakland Theater Guild, Women's City Club, 1428 Alice St.; Faucet School of the Theater, 1400 Harrison St.; East Bay Children's Theater, Junior League, Hotel Oakland.

Burlesque: Moulin Rouge, 485 8th St.

SPORTS

Archery: Peralta Park, 10th and Fallon Sts.

Auto Racing: Oakland Speedway, E. 14th St. and 150th Ave.

Baseball: Oakland Baseball Park (Pacific Coast League), San Pablo and Park Aves. Auditorium Field, 8th and Fallon Sts. Bay View, 18th and Wood Sts. Bushrod, 60th St. and Shattuck Ave.

Boating: Lake Merritt.

Boxing: Oakland Civic Auditorium (Wednesday nights).

Cricket: Golden Gate Playgrounds, 6142 San Pablo Ave.

Golf: Knoll Golf Course, Oak Knoll and Mountain Blvd. Lake Chabot Municipal Golf Course, end of Golf Links Rd.

Ice Skating: Oakland Ice Rink, 625 14th St.

Lawn Bowling: Lakeside Park, N. shore Lake Merritt.

Riding: Bridle paths in hills; horse rental $1.00 per hour up.

Softball: Exposition Field (lighted), 8th and Fallon Sts. Wolfenden Playgrounds (lighted), 2230 Dennison St. Allendale School, Penniman and 38th Aves. Goldengate Playground, 6142 San Pablo Ave. Manzanita School, 24th Ave. and E. 26th St. Poplar Playground, 32nd and Peralta Sts.

Swimming: Lion's Pool, Dimond Park, Fruitvale Ave. and Lyman Rd.; children 15¢, adults 25¢; no suits or towels furnished. Lake Temescal . Forest Park Pool, Thornhill Dr.; children 15¢, adults 250; suit 10¢, towel 5¢, caps 10¢ to 25¢.

Tennis: 31 municipal courts; daytime free, 250 per court per ½ hour nights. Athol Plaza, Lakeshore Blvd. and Athol Ave. Bella Vista, 10th Ave. and E. 28th St. Brookdale Plaza, High St. and Brookdale Ave. Dimond Park, Fruitvale Ave. and Lyman Rd. Mosswood Park, Moss Ave. and Webster St. Davie Tennis Stadium, 188 Oak Rd.

Wrestling: Oakland Civic Auditorium (Friday nights).

Yachting: Oakland Yacht Harbor, foot of 19th Ave.

CHURCHES

(Only centrally located churches of most denominations are listed)

Baptist. First, 530 21st St. Buddhist. Japanese Buddhist Temple, 6th and Jackson Sts. Christian. First, 29th and Fairmount Sts. Christian Science. First Church of Christ, Scientist, 1701 Franklin St. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, 3757 Webster St. Congregational. First, 26th and Harrison Sts. Episcopal. St. Paul's, Bay Place and Montecito Ave. Evangelical. St. Mark's, Telegraph Ave. and 58th St. Free Methodist. First, 459 61st St Greek Orthodox. Holy Assumption, 920 Brush St. Hebrew Orthodox. Temple Sinai, 28th and Webster Sts. Lutheran. St. Paul's, Grove and 10th Sts. Methodist. First, 24th and Broadway. Presbyterian. First, 26th and Broadway. Roman Catholic. St. Francis de Sales, Grove and Hobart Sts. Salvation Army. Salvation Army Citadel, 533 9th St. Seventh Day Adventist. Oakland Central Church, 531 25th St. Unitarian. First, 685 14th St.

OAKLAND (0-1600 alt., 304,909 pop.), seat of Alameda County, occupies roughly the central part of the East Bay metropolitan area. Berkeley and Emeryville to the north and Alameda, across the Estuary, limit its expansion, but to the east and southeast it sprawls without let or hindrance over hills and Bay-shore flats.

From the tall white City Hall in the heart of the city, streets, once country roads, radiate: San Pablo Avenue striking northwest to industrial Emeryville and West Berkeley; Telegraph Avenue and Broadway, north through the newer residential sections to the University of California; Fourteenth Street, west through shabby neighborhoods toward the Bay, and east and southeast by zigzags past Lake Merritt and an interminable series of local retail shops supplying the small, neat but monotonous rows of white houses which make up East Oakland, Fruitvale, Melrose, and Elmhurst.

Closely hemming the downtown section, where a few tall office buildings loom over squat business structures, are two- and three-story homes of the “gingerbread” era, slightly down-at-the-heel. Spreading north and east toward the hills from Lake Merritt in the heart of the city are thousands of wood and stucco houses, each with its shrubs and lawn. The one reminder of Oakland's Spanish heritage is the modern homes in the restricted districts—Rockridge, Broadway Terrace, and Claremont Pines—constructed in a modified Mediterranean style of architecture, tile-roofed and stuccoed, with wide arches, studio windows, and sunny patios. Semitropical trees—camphor, acacia, pepper, dracena, and palm—ornament city parks and sidewalks, and figs and citrus fruits ripen in the warm sunshine in many backyards.

Warmer in the summer than its metropolitan neighbor across the Bay, Oakland's climate is nevertheless tempered in summer by cooling winds and fogs from the ocean. This has attracted many San Francisco business men and office workers who, even before the building of the great bridge, came here.

In the springtime, the hills become green backgrounds for wildflower mosaics of scarlet and purple, blue ánd yellow. Besides the Coast live-oak for which the city was named, the Monterey pine and the eucalyptus are abundant, the latter introduced from Australia in 1856 and planted by thousands in the hills to create a wooded watershed. Vivid with color during the spring months, the uplands are seared to silver-brown through summer and fall because of lack of rain.

Around the City Hall spread the 70 blocks of the retail shopping district. Oakland's department stores and speciality shops draw patronage from the entire East Bay region, but they also yield a certain percentage of such trade to the transbay metropolis, as San Francisco trade names on the doors of local shops indicate. Influenced by the close commercial tie-up between the two cities, Oakland's tempo of living varies with the time of day: by dawn commuters are on the move, feeder highways to the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge are alive with speeding cars, and interurban trains clang through the streets, crossing and re-crossing the great span. After the early morning rush, life in the downtown section settles into a somewhat more moderate pace. At the end of the day, as automobiles, buses, and streetcars carry thousands home from work, the main thoroughfares come to noisy life again.

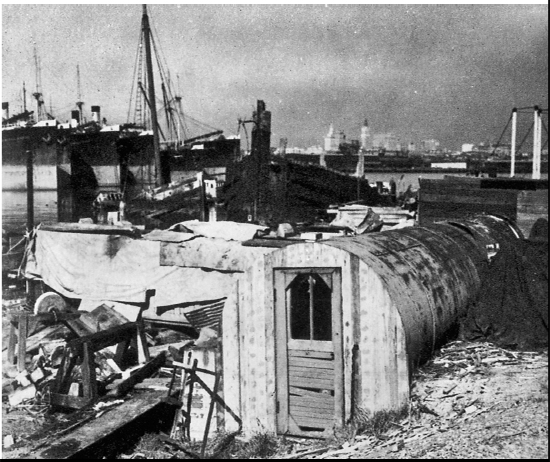

South of the central business district, the section between Tenth Street and the shore of the Estuary, oldest quarter of the city, is now given over to bargain stores, second-hand shops, and workers’ homes. On lower Broadway is a section of honky-tonk beer parlors and skid-road soup houses, where a burlesque show with lurid lobby portraiture is neighbor to a hole-in-the-wall pawnshop and an old-clothes emporium, where panhandlers linger on street corners and at entrances to penny arcades. Southward, interspersed with unpainted, grimy dwellings, are wholesale houses.

Along the Estuary itself, resounding to the grating squeak of winches and the staccato chug of wharf tractors are huge docks, a part of the Port of Oakland's Inner Harbor—one of the three on the city's 32-mile water front : Outer Harbor, between San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge approach and the Southern Pacific mole; Middle Harbor, bounded by the Southern Pacific and Western Pacific Railroads; and Inner Harbor, comprising the six miles of tidal estuary between Oakland and Alameda. Into the narrow Inner Harbor come freighters from the seven seas. Here are held crew races of the University of California, and here pleasure craft and fishing boats nose in and out.

West of downtown Oakland, extending from Market Street to the Bay and from the Estuary to Twentieth Street, is the West Oakland district. Crowding close about railroad yards and manufacturing plants are unsightly and dreary-looking dwellings. On some of the streets spacious old homes still maintain an air of shabby and aloof gentility, but many have been partitioned into crowded, rabbit-warren housekeeping rooms. Throughout the district are rows of ugly cottages with blistered paint and rickety stairs and porches, many of which are now being demolished to make way for new projects of the United States Housing Authority. Along Seventh Street, intersecting this district east and west, rumble the interurban trains.

In West Oakland is the city's Harlem, home of the large Negro population attracted by Oakland's position as the western terminus of two overland railway systems, which employ in great numbers waiters, cooks, and porters. West Seventh Street is the center of Negro life. Here are dance halls, restaurants, markets, barber shops, and motion picture theaters for Negroes.

Although Oakland's population includes thousands of Portuguese, Italians, Mexicans, and Chinese, its various national groups are scattered throughout the city rather than settled in well-defined foreign quarters. But their customs and their cuisine lend colorful variety to the city's life.

The Portuguese have been here for three generations, and yet they still hold to such national customs and festivals as the Feast of the Holy Ghost, celebrated annually. A large number of Portuguese-Americans in the environs are truck farmers and dairymen. The Italians, largest foreign language group, have influenced the culinary art of the community. Numerous Italian restaurants feature various antipasti with which to whet the appetite; polenta, a thick porridge of corn meal; and such delicacies as fried artichokes or squash blossoms dipped in batter and fried in deep olive oil. The Mexican population maintains a few restaurants which serve native Mexican foods—enchiladas, tacos en tortillas, and chili rellena—and an occasional hole-in-the-wall shop where strings of chorizo (Mexican sausage) hang from gray rafters and three-bushel jute bags of purple and crimson peppers stand in corners. Chinatown, with its dangling lanterns and picture word signs, houses its 3,000 Chinese in a loosely knit community centering in the wholesale district near Eighth and Franklin Streets. Up and down its sidewalks the soft-soled slippers of Old China shuffle along beside Young China's tapping occidental heels. On market pegs hang exotic fruits and vegetables, dried ducks and transparent octopuses; from gaudy chop suey establishments issue strains of modern “swing.”

Although the site of Oakland was first visited by white men in 1770, when Lieutenant Pedro Fages led an expedition here seeking a land route to Point Reyes, a half century passed before the land was first colonized. In 1820 Spain's last governor of Alta California, Pablo Vicente de Sola, granted to one Sergeant Luis Maria Peralta a tract of land in recognition of conspicuous military service in the Spanish Colonial Army. This grant became known as the Rancho San Antonio. Covering 48,000 acres, it included the area now occupied by Oakland, Berkeley, and Alameda. Threescore years of age at the time he received this prodigious grant, Don Luis never actually lived on it, preferring to remain at his home on a grant he had obtained in 1818, Portados la Rancheria del Chino, near the pueblo San Jose. He had four grown sons whom he placed in charge of Rancho San Antonio. Not only was this the first, but it was also the most valuable, of the land grants on the east shore of San Francisco Bay. Lean years were few. The soil was rich, and herds multiplied rapidly; but agriculture was confined to the raising of a few staples grown in limited quantities.

In 1842 Don Luis, then past 80, divided his grant among his sons. To Jose Domingo he gave what is now Berkeley; to Vicente, the Encinal de Temescal (now central Oakland); to Antonio Maria, the portion to the south (East Central Oakland and Alameda); and to Ignacio, what is now Melrose and Elmhurst. Realizing the danger of future family altercations, he adjured them: “I command all my children, that they remain in peace, succoring each other in their necessities, eschewing all avaricious ambitions, without entering into foolish differences for one or two calves, for the cows bring them forth each year; and inasmuch as the land is narrow, it is indispensable that the cattle should become mixed up, for which reason I command my sons to be friendly and united.”

To this sage advice his sons listened with respect. During the golden years of the Peraltas’ reign over Rancho San Antonio, business was seldom allowed to interfere with pleasure. There were innumerable fiestas, and, on Antonio's share of the grant, bull fights were held. But while the Spaniards complacently watched their grazing herds of fat cattle “without entering into foolish differences for one or two calves,” a new economic order was emerging. Gold had been discovered. Across the Bay the sleepy settlement of Yerba Buena had become a lusty brawling town crowded with men of all descriptions, including trigger-quick adventurers.

Shaken by the momentous events which were threatening the destinies of the Peralta clan, Don Luis called its members together—sons and grandsons—and spoke with grave earnestness, imparting final words of wisdom: “My sons,” he said, “God has given this gold to the Americans. Had He desired us to have it, He would have given it to us ere now. Therefore, go not after it, but let others go. Plant your lands and reap; these be your best gold fields, for all must eat while they live.”

In 1849 there arrived the first American settler in this region, a former sea captain, Moses Chase. Soon thereafter three newcomers, Robert, William, and Edward Patten, who had leased land from Antonio Peralta, added Chase to their group and became the first American farmers in this district, raising good crops of hay and grain.

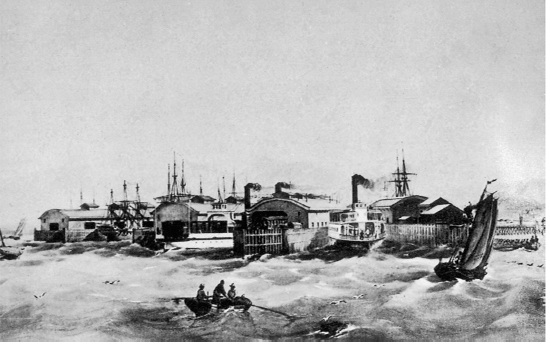

With these tenants the Peraltas had come to terms, but a steady stream of new squatters also dotted their holdings. Unsuccessful in several attempts in 1850 and 1851 to eject the newcomers, they were forced at length to compromise by granting leases. Among these squatters was a man whose name was to be closely linked with the early history of Oakland—Horace W. Carpentier, who recently had been graduated from Columbia College in New York. Associated with him in the enterprises that were destined to make him many times a millionaire were A. J. Moon and Edson Adams. Having acquired with his partners a townsite where present downtown Oakland is situated, Carpentier in 1852 succeeded in having the town of Oakland incorporated, with himself seated securely in the mayor's chair. When the citizenry, who were seldom advised of what their mayor was doing, awoke, he held—among other concessions—a franchise for a ferry to San Francisco, the fare to be one dollar a trip.

Carpentier obtained absolute title to the entire water front in exchange for building a small frame schoolhouse and three tiny wharves. The water-front deal resulted in prolonged litigation, known as the “Battle of the Waterfront,” by which the city tried to regain title to its doorstep. The fight was not ended until 1910, when assignees of Carpentier agreed to waive title to the water-front property in exchange for long-term leases.

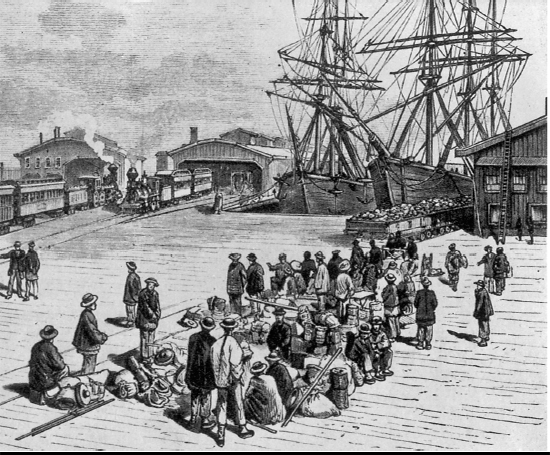

The first combination rail and ferry service began operation to San Francisco in 1863, although ferry service alone had started as early as 1850. During the 1860’s the “Big Four”—Stanford, Huntington, Crocker, and Hopkins—started building the Central Pacific Railroad, for which Oakland was the proposed western terminus. When in 1867 they asked the city for water-front rights, the city was unable to comply, having presented all such property to Horace Carpentier. However, the next year Carpentier founded a corporation known as the Oakland Waterfront Company. Associated with him in this enterprise, among others, was Leland Stanford, one of the “Big Four.” Carpentier deeded to the corporation his water-front holdings and the corporation in turn conveyed to the railroad 500 acres of tideland. The railroad later appeared as the chief defendant, and loser, in the suit wherein Oakland regained these properties.

At one time the railroad officials had considered the Government-owned Yerba Buena Island as a western rail terminus. The citizens of San Francisco objected violently. It was feared “that the real intention was, by leveling the island and constructing causeways to Oakland, to rear up a rival city on the opposite shore that would be in substance owned…by the railroad company.” The plan died when the Senate refused to approve the scheme. All obstacles finally surmounted, the first overland rail service began in 1869.

By 1870 there were two banks, three newspapers, and a city directory. Gas lamps illuminated lower Broadway. The first paving had been laid—at a cost of $3.40 per square foot. The University of California (later moved to Berkeley) was “spreading light and goodness,” and a seminary for young ladies—now Mills College—was about to open.

The Central Pacific had entered the city, and the Oakland Railroad, already connecting with ferries to San Francisco, had been granted the right “to run horse-cars from the end of Broadway to Temescal Creek, and thence to the grounds of the College of California, for thirty years.” Southeast of Lake Merritt the villages of Clinton, San Antonio, and Lynn had been consolidated into the town of Brooklyn—now East Oakland.

The social life of the town, also, had seen great change. No longer were posters seen such as the one which had announced in earlier days:

“There will be a great bear fight in front of the American Hotel, Oakland, between the red bear Sampson and a big grizzly on Jan. 9th.”

By 1870 this form of entertainment had been banned, and less sanguinary pleasures had taken its place: baseball instead of bullfights and typically Yankee “dime parties,” socials, and church bazaars instead of Spanish fiestas.

In its growth as a suburb, it gained some distinction from the artists and writers who lived here. Jack London was developing from a water-front loiterer into an internationally known novelist. Joaquin Miller, the “Poet of the Sierras,” was vaingloriously displaying his long hair and longer beard. Edwin Markham, while teaching in an Oakland school, awoke to find himself famous for “The Man With the Hoe.” William Keith was painting the East Bay hills and trees. George Sterling, the lyric poet of whom London, his contemporary, said, “he looked like a Greek coin run over by a Roman chariot,” lived in Oakland from 1890 to 1905, and Ina Coolbrith, who as librarian of the Oakland Public Library guided the early reading of Jack London, and who was a poetess in her own right, was here from 1873 until 1897.

Oakland's growth was greatly accelerated by the earthquake and fire that overwhelmed San Francisco in 1906. Although itself damaged by the earthquake, it escaped the fire which overwhelmed the neighboring city.

Up to 50,000 refugees fled to the East Bay region in one week. Not a few remained as permanent residents. This influx caused such a building boom that by the following year the population had jumped to 125,000. Industrial growth also was stimulated. During the World War, industry boomed as four large shipbuilding companies operated at peak capacity. By 1920 the population was 216,000.

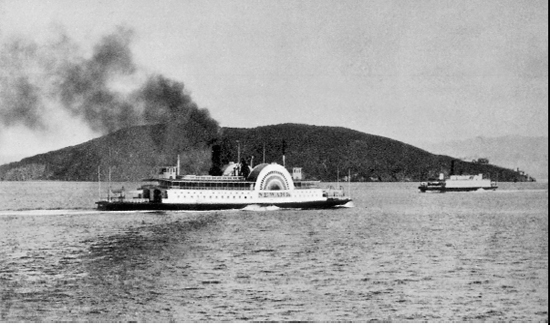

The rapid growth of Oakland shortly after 1900 is credited largely to Francis Marion “Borax” Smith, of Death Valley fame. With the huge profits from his borax mines, Smith invested heavily in the future of Oakland. He tied together the numerous street railway systems of the East Bay and founded the Key Route Ferry System in opposition to the Southern Pacific; he acquired control of the East Bay Water Company, and in partnership with Frank C. Havens, pioneer capitalist, established the Realty Syndicate as a holding company for their many real estate properties. Land in every region of Alameda County was bought and developed, residential and industrial tracts were opened up, and interurban train service was extended into each new era. Smith came to own an estimated one-sixth of Alameda County.

In December, 1910 the $200,000,000 United Properties Company was formed by a merger of money and properties owned by Smith, William S. Tevis, and R. G. Hanford. This corporation, perhaps the largest in California history (excepting the Eastern-controlled Southern Pacific Railroad), was to absorb and develop the railways, ferry system, public utilities, and real estate of the East Bay. However, the company collapsed in 1913 because of unsound financial methods, carrying with it the fortunes of the three founders. Smith, the heaviest loser, saw $24,000,000 slip from his fingers almost overnight. But the company's loss was the city's gain, for its developments remained.

In the Bay region, Oakland's port ranks second to San Francisco in value of cargo handled, and third to Richmond and San Francisco in tonnage. Coordinated water-rail-truck facilities handle the 3,500,000 tons of cargo that pass over the water front annually. Principal exports are dried and canned fruits and vegetables, lumber, grain, salt, and petroleum. Imports include copra, coal and coke, paper, iron and steel, and fertilizer. Fir, pine, cedar, spruce, and redwood arrive from the Northwest and the interior of California to be made into finished lumber or wood products before distribution.

Oakland's water front is well-equipped not only to repair bay, river, and oceangoing vessels but also to lay down such craft and to launch and outfit them. Yachting, commercial fishing, towing, and general boatbuilding and repairing call for many smaller shipyards. Construction work on large yachts and other boats is facilitated by the proximity of large Diesel engine works.

Fortunate in having ample room for residential expansion, Oakland is still growing. On the outskirts, where garden space is available, files of newly built homes spread into the countryside. Thus Oakland, despite the encroachment of industry, retains its identity as a city of homes.

POINTS OF INTEREST

1. The ALBERS BROTHERS MILLING COMPANY PLANT (tours for visitors Tues., Wed., Thurs., 10 a.m., 2 p.m), west end of Seventh St., manufactures a wide variety of packaged food products and feeds for animals.

2. The NAVAL SUPPLY DEPOT, end of Middle Harbor Rd., will be the largest in the Nation when completed sometime after 1942 at an estimated cost of $15,000,000. It will have 49 buildings; immense warehouses will provide storage space sufficient to hold a two-year supply of food, clothing, equipment, and other materials for the entire United States Navy. Two wharves, capable of handling six battleships, will be reached through a channel and turning basin.

3. The PACIFIC COAST SHREDDED WHEAT COMPANY PLANT (visiting hours 9-11, 1-4; guides furnished), Fourteenth and Union Sts., ships much of its large output to countries around the Pacific. In the process of making shredded wheat, hard wheat is dry-cleaned, steam-cooked, and stored in steel tanks for ten hours. Shredded between grooved rollers under 1,700 pounds pressure, it emerges in twenty-nine threadlike layers which are cut into biscuits and baked for twenty minutes at 550° F.

4. The MOORE DRYDOCK (no visitors), foot of Adeline St., in 1939 laid keels for four cargo steamers under a $12,000,000 contract with the United States Maritime Commission—the first sizable vessels to be built in San Francisco Bay since the World War. The concern's 300- and 500-foot floating drydocks and marine railway docks provide for building and repairing vessels and for such special jobs as constructing the caissons used in the piers of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. This firm, since it laid in 1909 the keel of the first steel ship built in Oakland, has launched 200 such craft. During the World War 58 vessels were constructed, six of them sliding down the ways in 1918 on a single morning tide.

5. At ST. JOSEPH'S CHURCH, Seventh and Chestnut Sts., occurs the annual Portuguese Festival of the Holy Ghost, which originated in Portugal in the thirteenth century when Queen Saint Isabel had a vision of the Holy Ghost. To her He indicated a desire that a church be built in His honor. The ceremonial of the dedication of that church, with its procession, its crowning of a queen, and its placing of the crown on the Altar of the Third Person of the Blessed Trinity, has survived among the Portuguese to this day. The festival, centering around Pentecost Sunday, is celebrated with feasting on barbecued meats and sopas and dancing of the chamarita.

6. The OAKLAND PUBLIC LIBRARY, Fourteenth and Grove Sts., contains 275,000 volumes and 200,000 pictures and prints. Over the main stairway and on the walls of the second floor are murals by Marion Holden Pope and Arthur Matthews.

7. Oakland's tallest structure, the CITY HALL, Washington St. between Fourteenth and Fifteenth Sts., is a 17-story building rising 360 feet, completed in 1914, and was designed by the New York firm of Palmer, Hornbostel, and Jones, winner in a National competition. Faced with white granite and terra cotta in mingled Doric and Corinthian design, it has three set-back sections, capped by a baroque cupola adorned with four clock faces. The clock was donated by Dr. Samuel Merritt, former mayor.

Opposite the City Hall, overlooked by towering downtown buildings, is the triangular MEMORIAL PLAZA, dedicated to American war heroes.

8. Famed as the cradle of Jack London's genius, the FIRST AND LAST CHANCE SALOON, 50 Webster St., near the Oakland Estuary, has also warmed many another literary celebrity, including Robert Louis Stevenson, Joaquin Miller, and Rex Beach. A guest book bears the signatures of hundreds of the great and near-great. The small, weathered, dilapidated structure, built over 60 years ago from the timbers of an old whaling boat, was first used as a bunkhouse for men working the oyster beds along the East Bay shore. As a saloon, especially in the 1890’s, it was a popular hangout for ready-fisted seafarers who crowded its bar and gambled at its card tables. Jack London, in his early teens, found a friend in the proprietor, the late Johnny Hein-old, through whose encouragement and financial assistance his genius flowered in adventure tales woven around the lives of South Sea traders, Arctic whalers, and Alaska sourdoughs. Today the tinder-dry boards of the old building are blotched with cracked grey paint. The scarred mahogany bar is still in service. The old gambling tables on which young London often wrote are used for refreshments. On a wall, guarded from souvenir hunters by chicken wire, are letters and photographs, including a picture of Jack in knickerbockers poring over Heinold's tattered old dictionary, and a letter, written years later, inviting Heinold to the author's famous Glen Ellen home.

9. The POSEY TUBE, 4,436 feet long, passing under the 42-foot-deep channel of the Oakland Estuary between Harrison St. in Oakland and Webster St. in Alameda, when completed at a cost of $5,000,000 in 1928 was the world's largest under-water tube for vehicular traffic (its 32-foot diameter has since been surpassed by the Mersey Tunnel at Liverpool, England). It is still the only such bypass west of Detroit, Michigan. Its unusual method of construction drew the attention of engineers the world over. In the Oakland Portal, administrative and operating center, are meters that automatically count passing vehicles, control boards that govern the ventilating system, and delicate instruments that register the percentage of carbon-monoxide gas from automobile exhausts in every part of the tunnel. A staff of 17 engineers, mechanics, and traffic policemen is always on duty. Only two fatal accidents occurred in the tube during its first 11 years, in which time 70,500,000 trips were recorded.

10. The BUDDHIST TEMPLE, Sixth and Jackson Sts., with its courtyard and school, is the center of Buddhist social and religious life in the East Bay. Here American-born Japanese children, after attending public schools, spend two hours daily learning their mother tongue and old-country customs.

11. The 32-acre PERALTA PARK, facing Lake Merritt across Twelfth St., is dominated by the $1,000,000 steel and concrete, granite-finished MUNICIPAL AUDITORIUM, built in 1915 on ground once occupied by a group of houses collectively known as the “House of Blazes”—a not very select bagnio. The building is in classical style, the main facade facing the lake ornamented by a series of bas-reliefs in terra cotta set in the alcoves above the entrance doors. Besides the arena, seating 10,000, which is used for conventions and sports events, it contains a large theater for dramatic and musical performances. The ART GALLERY (open 1-5) on the upper floor houses a permanent collection of paintings. Except for about 30 canvases by Russians, the work is chiefly that of California artists, including Charles Rollo Peters, Xavier Martinez, and William Keith.

12. Across Tenth St. from the auditorium, in Peralta Park, is the EXPOSITION BUILDING, a one-story, concrete and steel structure used chiefly as an armory by the California National Guard, and for civic events. Within the park are a playfield, a militia drill ground, and the shooting ranges and lodge of the Oakland Archery Club, whose members meet and shoot every Sunday morning.

13. The ALAMEDA COUNTY COURTHOUSE, facing Lake Merritt on Fallon St. between Twelfth and Thirteenth Sts., is a steel and concrete structure of neoclassic design, built in 1936 at a cost of $2,500,000. Inside the main entrance, on opposite walls, are two murals designed by Marian Simpson and executed by the WPA Federal Art Project, which depict Alameda County in Spanish days and in Gold Rush times in more than 50 colors of marble.

14. LAKE MERRITT, a 155-acre body of tidal water extending northeast from Twelfth St., named for Dr. Samuel Merritt, ex-Mayor of Oakland who helped create it, occupies the once marshy, muddy lagoon adjacent to San Antonio Creek, dammed and dredged in 1909. Hydraulic gates control the water level. A boulevard, a macadam footpath, and a chain of lights encircle the lake. Directly north of the Oakland Public Museum is the large, concrete, brown-gabled BOAT-HOUSE (open 8-12 midnight; rowboats, canoes; around-the-lake water tour, 10¢, children 5¢), containing a dining room, crew quarters and meeting rooms.

15. The OAKLAND PUBLIC MUSEUM (open weekdays 10-5, Sun. and holidays 1-5), beside the lake at 1426 Oak St., housed in a brown, two-story frame building, contains exhibits in natural science and the ethnology of the Pacific Coast. The American history display includes relics of the Nation's wars. Indian, Spanish, and pioneer articles are shown in the California room. In the two Colonial rooms are reproductions of that period, and a “whatnot” once owned by Abraham Lincoln.

16. The SNOW MUSEUM (open 10-5 weekdays, 1-5 Sun. and holidays), 274 Nineteenth St., displays habitat groups of birds, animals, and other native life collected on various expeditions by the donor, Henry Adelbert Snow. In 1919-21, on one of these field trips, Hunting Big Game in Africa, the first wild-animal picture to be released by a major exchange, was filmed. A recent addition is the Cave Room, whose miniature dioramas of prehistoric animal life portray dinosaurs, mammoths, mastodon, great long-horned bison, saber-toothed cats, and other beasts. The collection includes about 50,000 bird eggs.

17. Amid gardens of Old-World tranquillity, the COLLEGE OF THE HOLY NAMES, 2036 Webster St., stands in an eight-acre campus on Lake Merritt's western shore. This liberal arts Catholic college for women grew from a high school founded in 1868 by the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, through the efforts of Reverend Michael King, pioneer Catholic priest, and received in 1880 a charter to award bachelor of arts degrees. Its scholastic department issued in 1872 the first high school diplomas granted in Oakland.

18. The 88-acre LAKESIDE PARK (bowling greens, tennis courts, golf putting greens, boating), Grand Ave. between Harrison St. and Lakeshore Ave., covers a blunt peninsula thrust between two arms of the lake. A granite boundary marker of the old Rancho San Antonio stands near the Bellevue and Perkins Sts. entrance. In a grassy amphitheater near the beach the Municipal Band gives concerts (Sun. 2:30, July-Oct.). A mounted torpedo porthole from the battleship Maine and a memorial tablet cast from metal recovered from the vessel stand about 200 yards northeast of the bandstand. The nine-foot McElroy Fountain of white Carrara marble on the south-central part of the esplanade walk was built in “Commemoration of the Public Services of John Edmund McElroy,” Oakland attorney. Near the southern end of the peninsula is a brown-gabled canoehouse (canoes for rent) and landing, where privately owned sail boats of the Lake Merritt Sail Club are quartered.

19. East of the canoehouse and landing is the LAKE MERRITT WILD-FOWL SANCTUARY (feeding hours Oct.-Mar., 10 and 3:30). In 1869 the California Legislature designated Lake Merritt as a migratory water-fowl sanctuary, and in 1926 it became a banding station of the United States Biological Survey. From four to five thousand fowl are present during the winter months, and many nest on the small wooded island built in the lake by the city in 1923. Besides many species of ducks and geese, other visitors to the lake include the coot, egret, cormorant, grebe, gull, killdeer, loon, heron, swan, tern, plover, and snipe. Fowl tagged here have been shot as far afield as Siberia and Brazil.

20. From the site of EAST SHORE PARK at the easternmost tip of the lake, the Peraltas shipped hides and tallow. Their embarcadero is marked by concrete columns bordering a crescent-shaped brick wall, built in 1912.

21. The VETERANS MEMORIAL BUILDING, N. side of Grand Ave., adjoining Lakeside Park, has an auditorium seating 700 and a collection of war trophies.

22. The FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, Broadway at Twenty-sixth St., a fine modern adaptation of perpendicular Gothic architecture (William C. Hays, architect), has stained-glass windows designed by Stetson Crawford, a pupil of James McNeill Whistler.

23. A public recreation center, MOSSWOOD PARK (8-8 daily), Moss Ave. between Broadway and Webster St., contains playfields, tennis, roque, and croquet courts, horseshoe-pitching ranges, and a shrub-bordered garden theater. A little arroyo spanned by rustic bridges and bordered by flowering shrubs and ferns meanders beneath fine old oaks past the RESIDENCE OF JOHN MORA MOSS, built in the 1860’s, which is now used as a clubhouse and tea room.

24. The MUNICIPAL ROSE GARDENS, in Linda Vista Park, Oakland and Olive Aves., eight acres in area, contain approximately 8,000 bushes.

25. The STATE INDUSTRIAL HOME FOR ADULT BLIND, 3601 Telegraph Ave., occupies a group of white concrete buildings in mission style. In the display room are reed furniture, baskets, pottery, brooms, and other articles made by the blind.

26. Founded in 1907, the CALIFORNIA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND CRAFTS, 5212 Broadway, which occupies several buildings on a four-acre campus, claims distinction as “the only art institution on the Pacific Coast authorized to grant college degrees” and as the only one in California “where, on a single campus, students may complete their work for state teaching credentials…[while] gaining their professional art training.” As the former California School of Arts and Crafts, a nonprofit, coeducational institution, it served the West from 1907-37. In the Divisions of Fine Arts, of Applied Arts, and of Art Education are studios and exhibition halls. The campus with its flowers, shrubs, and trees, its native birds and small animals for art models is the setting for outdoor sketching and painting. Since 1909 the Aztec Indian pupil of Whistler, Xavier Martinez, born in 1873 in Guadalajara, Mexico, has taught painting here. Dressing primitively in hand-woven materials, his black hair bound by a leather thong, “Marty” is unconventional as a teacher, bold and direct as a painter.

27. Entered through a massive stone gateway, MOUNTAIN VIEW CEMETERY, head of Piedmont Ave., on a beautifully landscaped hillside, has a fine view of San Francisco Bay. The pioneer Dr. John Marsh, Washington Bartlett, Governor Henry Haight, Joseph Le Conte, and Francis Marion “Borax” Smith are buried here.

28. In ST. MARY'S CEMETERY, Roman Catholic, head of Howe Street, are the graves of many Spanish pioneers, among them members of the Peralta family.

29. LAKE TEMESCAL REGIONAL PARK, Chabot and New Tunnel Rds., is an abandoned reservoir converted by WPA labor into a recreation center. From the brick boathouse (open May-Sept.; 8:30-7; lockers 10¢; swimming free; canoes and boats 50¢ per hour) juts a long float, equipped with springboards for swimmers. Another float has water targets for casting practice and tournaments.

30. First frame dwelling in Oakland, The MOSES CHASE HOME (private), 404 E. Eighth St., retains only one of the four rooms built in 1850, but several additions have been made. Original ceiling beams, shaped by hand and joined by wooden pegs, are still firm and strong. The Massachusetts Yankee was Oakland's first settler from the “States.”

31. The OAKLAND YACHT CLUB, foot of Nineteenth Ave., established in 1913, has berths for about 100 yachts and motorboats. Each year its members contest for three trophies: the Wallace Trophy for sailboats, the Craven Trophy for “star”-type sailboats, and the Tin Cup Derby for motorboats (an engraved tin cup is the winner's award). At one time Jack London was an honorary member. For the club's annual midsummer party, “A Nite in Venice,” to which the public is invited, the harbor is strung with colored lights.

32. DIMOND PARK (horseshoe court, picnicking, tennis, swimming), Fruitvale Ave. and Lyman Rd., lies in a canyon shut in at its northern end by precipitous slopes. The 12-acre tract, green with eucalyptus, oak and acacia, extending along Sausal Creek, was named for Hugh and Dennis Dimond, who became owners of this part of Rancho San Antonio. The 105-foot LIONS POOL (bath house; sand beach) is Oakland's principal outdoor plunge. In the park is the DIMOND COTTAGE, built in 1897 of adobe bricks from the original home of Antonio Maria Peralta, which stood at 2501 Thirty-fourth Avenue. The adobe, 16 by 28 feet, built by the Dimond brothers, is now the headquarters of a Boy Scout troop.

33. JOAQUIN MILLER PARK (THE HIGHTS), Joaquin Miller Rd. near Mountain Blvd. (hiking trails; community kitchen; picnic areas), is a 67-acre highland area purchased by Oakland as a memorial park in 1917. The 75,000 eucalyptus, pine, cypress, and acacia trees were planted by Miller—who resided here from 1886 to 1913—with the aid of friends and visitors. A native of Indiana, Cincinnatus Heine Miller (1839-1913), after a career of Indian-fighting and small-time politics—during which he took the first name of the bandit Joaquin Murietta—became California's white-haired “Poet of the Sierras.” Participation in the Alaska gold rush and the Chinese war added more color to his last years. Eccentric in dress and demeanor, Miller was much beloved in England as a poet of the American frontier. He is best-known for his school-text poem, “Columbus,” although he wrote prolifically. At “The Hights” (as he spelled the name of his estate), he provided homes for the poets, Yone Noguchi and Takeshi Kanno. George Sterling, Jack London, Harr Wagner, and Edwin Markham were among his frequent guests. Buried in the little cemetery here is Cali-Shasta, his daughter by a Pitt River Indian woman. Later in Oregon he married a young poetess, who bore him three children before she divorced him. A daughter by a still later marriage to Abbie Leland now resides at “The Hights,” having reserved a life tenure in it when she sold the property to Oakland.

THE ABBEY, built in 1886, is a small, low gray frame building consisting of three one-room structures interconnected to form a single unit, each room roofed with a shingled peak. Miller said it was inspired by Newstead Abbey in England and spoke of it as a “little Abbey for little Abbie,” his wife.

A loop trail beginning at the park's souvenir shop, which is flanked by “Juanita's Sanctuary” and “Juanita's Wigwam,” leads past the stone funeral pyre on which Miller wished to be cremated (but was not), the “Pyramid to Moses,” the “Tower to Browning,” and the “Frémont Monument.” Miller was his own mason in building these oddly asymmetrical monuments of native rock. In the center of the park are cypress trees planted in the shape of a cross.

The WOODMINSTER MEMORIAL AMPHITHEATER, constructed by WPA labor under the direction of the Oakland Board of Park Directors, is a memorial to California writers. A cascade beginning near the rear of the amphitheater flows through eight flower-bordered pools to an electric fountain illuminated by constantly changing colors.

34. The 182 acres of SEQUOIA PARK, Joaquin Miller Rd. and Skyline Blvd. (picnicking, outdoor grills, bridle paths), are shaded by towering redwoods. Sequoia Point, within the park, a circular landscaped point, provides a panorama of the Bay to the south, bringing into view East Oakland, Alameda, San Leandro, San Leandro Bay, the Oakland Airport, and the Estuary.

35. Best-known women's college west of the Mississippi, MILLS COLLEGE, Seminary Ave. between Camden St. and Calaveras Ave., is also one of the oldest in the United States. The present residential, non-sectarian college began as the Young Ladies Seminary in 1852 in Benicia. In 1865 Dr. and Mrs. Cyrus Taggart Mills purchased the school and six years later removed it to the present beautifully wooded campus of 150 acres at the base of the San Leandro hills.

Mills was patterned after Mount Holyoke Seminary in Massachusetts. As a college of liberal arts, it has schools in fine arts, language and literature, social institutions, natural sciences, mathematics, and education, leading to the A.B. degree, and a school of graduate studies which gives an M.A. or M.Ed. degree. The faculty of 100 members, serving about 600 students, is large enough to permit small classes and individual attention. Visiting faculty members in the graphic arts have included Leon Kroll, Alexander Archipenko, Frederic Taubes, and the Bauhaus group; in music, Henry Cowell, Luther Marchant, and members of the Pro Arte Quartet; in dancing, Martha Graham, Hanya Holm, and Charles Weidman.

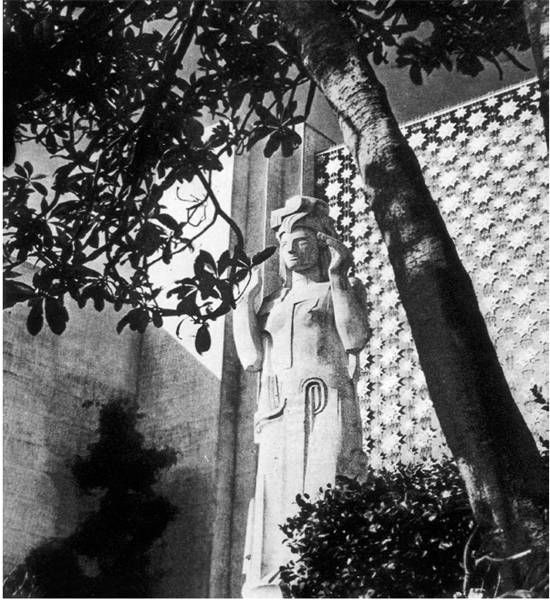

The campus buildings are notably successful adaptations in concrete of Spanish Colonial design. Through the Wetmore Gate on Seminary Ave. a winding road leads to EL CAMPANIL, a buttressed tower of tan-colored concrete, the gift of Francis M. “Borax” Smith, in whose pierced belfry is a chime of ten bells cast for the Chicago World's Fair of 1893. A number of residential halls in an informal style are grouped about beautifully landscaped courts and terraces. The MUSIC BUILDING, in the style of a Spanish Renaissance church, has a fine doorway with ornate carving and an auditorium with murals by Ray Boynton. Graceful triple arches lead to the foyer of LISSER HALL, whose auditorium seats 600. Before a lofty open arcade leading to the ART GALLERY (open Wed. and Sun. 2-5) are two marble Dogs of Fu, Chinese carvings of the Ming dynasty in white marble. In addition to a permanent collection of oils, etchings, bronzes, textiles, and oriental objects d'art, the galleries have occasional loan exhibits. The 77,000 volumes in the LIBRARY (open to visitors), include the collection of about 5,000 rare books and manuscripts given by Albert M. Bender. The WOODLAND THEATER, a natural amphitheater in a eucalyptus grove, is the scene of outdoor plays. Bordering LAKE ALISO near the northern boundary of the campus is an outdoor stage used for dance programs.

36. CHABOT OBSERVATORY (open Tues.-Sat. 1-5, 7-9:30), 4917 Mountain Blvd., named for Anthony Chabot, pioneer, capitalist, and philanthropist, is one of the few California institutions of its kind serving the public schools. Lectures are given to classes from the Oakland schools and from Mills College, which assist jointly in maintenance of the observatory's large lecture hall, reading room, and astronomical library. Illustrated programs for adult astronomy students and meetings of the East Bay Astronomical Association are held here. The two-story stucco building, on the landscaped hillside, houses a spectroscope and 8- and 20-inch refracting telescopes. Connected with the institution is a meteorological station which collects data for Oakland weather reports.

37. The ALAMEDA COUNTY ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS (open 9-6; adm. 10¢; picnicking), Ninety-eighth Ave. and Mountain Blvd., cover 450 well-wooded acres formerly known as Durant Park, now administered by the Alameda County Zoological Society. It contains an arboretum and a small zoo. (In 1940 removal of the Oakland City Zoo from Sequoia Park to a site near the main gate was planned.) Occasional nature-study programs are presented under the direction of Sidney Adelbert Snow, noted big-game hunter and photographer, who lives on the grounds.

38. On the tidal flats of Bay Farm Island in San Leandro Bay is the OAKLAND MUNICIPAL AIRPORT (lunch room), comprising 850 acres. Here are located a unit of the United States Naval Reserve, the western terminals of transcontinental air lines, flying schools, and hangars for privately owned planes and local air taxis. Along Earhart Road, which parallels the airport's southeastern edge, are hangars, the administration building housing the Airport Weather Bureau, and a small glass-enclosed exhibition building, displaying an old pusher-type biplane built in 1910 which placed first in a 1912 international competition. The Wiseman plane, first successful heavier-than-air craft built in California, is suspended in the nearby Navy hangar. Five huge corrugated iron hangars, decorated with brightly painted flying directions, house maintenance shops, schools, and operating offices. The island was first used as a port in 1927 when, in three weeks of day and night work, a runway was built to provide a take-off for the Army's mass flight to Hawaii. The present airport and channel are developments made by the city of Oakland largely with WPA labor.

Berkeley

Information Service: Chamber of Commerce, American Trust Bldg., Shattuck Ave. and Center St. Berkeley Travel Bureau, 81 Shattuck Sq. University of California administrative office, California Hall, U. of C. campus.

Railroad Stations: Southern Pacific, University Ave. and 3rd St. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry., University Ave. and West St. Bus Stations: Pacific Greyhound Lines and National Trailways, 2001 San Pablo Ave. Taxis: Average rate 20¢ first ¼ m., 10¢ each ½ m. thereafter, 1 to 5 passengers. Streetcars and Buses: Fare 10¢ or one token (7 for 50¢); to Hayward, El Cerrito, or Richmond, 20¢ or 2 tokens. Transbay electric trains to San Francisco, fare 21¢. Traffic Regulations: 25 m.p.h. in residential and business districts, 15 m.p.h. at intersections; 1 and 2 hour parking limit in business districts, all-night parking prohibited in all areas.

Accommodations: Ten hotels.

Concert Halls: Wheeler Hall, U. of C. Greek Theatre, U. of C. Women's City Club, 2315 Durant Ave. Radio Stations: KRE (1370 kc), 601 Ashby Ave. Motion Picture Theaters (first-run): Two. Amateur and Little Theaters: Wheeler Hall, U. of C., for university productions. International House Auditorium, Piedmont Ave. and Bancroft Way. Women's City Club Little Theater, 2315 Durant Ave.

Archery: Albany Archers, Tilden Park (straw targets). Archery Range, East Shore Highway, Albany (small fee). Baseball: Diamonds at Berkeley High School, Grove St. and Bancroft Way, and many public playgrounds.

Boating: Berkeley Aquatic Park. Football: D. of C. Stadium, foot of Bancroft Way. Berkeley High School, Grove St. and Bancroft Way. Golf: Charles Lee Tilden Regional Park. Berkeley Country Club, E. end Cutting Blvd. Ice Skating and Hockey: Iceland, Shattuck Ave. and Ward St.

Bowling: Municipal Bowling Green, Allston Way W. of Acton St. Riding: Arlington Hills Riding Academy, Arlington and Brewster Dr. Athens Polo and Riding Stables, 1010 San Pablo Ave. Berkeley Riding Academy, 2731 Hilgard St. Fairmont Riding Academy, Colusa and Fairmount Aves. Softball: City playground, 2828 Grove St. City playground, Mabel and Oregon Sts., and many school playgrounds. Swimming: Berkeley High School, Grove St. and Bancroft Way (open June 15-Aug. 15). Tennis: U. of C. campus. Berkeley Tennis Club (private), Tunnel Rd. and Domingo Ave. Also following recreational areas: City Hall, Allston Way and Grove St.; Grove, 2828 Grove St.; Codornices, 1201 Euclid Ave.; James Kenney, 8th and Delaware Sts.; Live Oak, Shattuck Ave. and Berryman St.; San Pablo, Mabel and Oregon Sts.

Churches (Only centrally located churches are listed): Baptist. First, 2430 Dana St. Buddhist. Hegeshi Honganji, 1524 Oregon St. Christian. University, 1725 Scenic Ave. Christian Science. First Church of Christ, Scientist, Bowditch and Dwight Way. Mormon. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, 2150 Vine St. Congregational. First, 2345 Channing Way. Episcopal. St. Mark's, 2314 Bancroft Way. Evangelical. Mission Covenant, Grove and Parker Sts. Free Methodist. Japanese, 1521 Derby St. Hebrew Orthodox. Hebrew Center, 1630 Bancroft Way. Lutheran. Bethany, 1744 University Ave. Methodist. Trinity, Durant and Dana Sts. Presbyterian. First, Dana St. and Channing Way. Roman Catholic. St. Joseph's, 1600 Addison St. Russian Orthodox. St. John's, 2020 Dwight Way. Seventh Day Adventist. Berkeley Seventh Day Adventists, Dana and Haste Sts. Unitarian. First, 2425 Bancroft Way. Miscellaneous. Apostolic Church of the Faith of Jesus, 829 University Ave.; Immanuel Mission to Seamen, 1540 Lincoln St.; Plymouth Brethren Church, 42nd and Rich Sts.; Reihaisho Hershinto, 1707 Ward St.; Unity Center, 2315 Durant St.

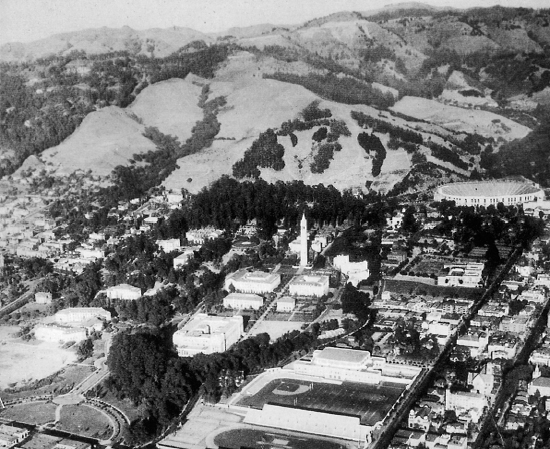

BERKELEY (0-1,000 alt., 84,827 pop.) spreads across a great natural amphitheater opposite the Golden Gate, rising from the shore of the Bay eastward to the crest of the Berkeley hills, over which the fogs often drift in late afternoon. To the alumnus, as to the academic world in general, Berkeley means the University of California. But while the university is its outstanding feature, Berkeley is really three or four towns in one. There is the Berkeley of the retired old men and women who trespass on the wooden senior bench near the student union building on the campus and attend lectures where they can “absorb culture in homeopathic doses,” as the beloved Charles Mills Gayley used to say. There is the world of those who commute to business in San Francisco; and there is industrial Berkeley, clustered along the Bay west of San Pablo Avenue—a two and one-half mile strip of factories bearing well-known trade names. Around the fringe of this section are massed the homes of the factory workers. This part of Berkeley seems spiritually more akin to industrial Emeryville on the south or to oil-refining Richmond on the north than to the gay bustle of the streets surrounding the campus—streets thronged with men students in corduroys and gaudy sweaters, women students in mock peasant head kerchiefs and jaunty little half-socks.

Among the hills on either side of the campus are the handsome new fraternity and sorority houses, the more modest homes of the faculty, and rambling terraced gardens, almost hiding houses clinging perilously to the side of the hill.

The lower sections of Berkeley adjoining the campus, particularly on the southern side, are given over to student lodgings. Here every other house carries a sign, often “Rooms—Men Only.” The men, though harder on the furniture than the girls, are less of a responsibility, because the office of the Dean of Women keeps an eagle eye on the campus homes of undergraduate women. Or the sign may read “Coaching—Mathematics, Russian and Chemistry” or “Typing, Neatly and Cheaply Done.”

“Downtown” Berkeley lies along Shattuck Avenue; the main business district, because of the proximity of metropolitan shopping centers, is surprisingly small for a city of Berkeley's size. It changes slowly with the years, although the old steam trains that used to bring students from the city to their eight o'clock classes and the horse-cars that occasionally were derailed by students who wanted an excuse for being late have long since given way to modern electric cars. Even the old red-brick Southern Pacific station, which sat squarely in the middle of Shattuck Avenue, finally gave way to modern stores in 1939.

Berkeley owes its naming to the university. A hundred years ago the site was part of the great Rancho San Antonio of the Peralta family. When it was selected in 1866 as the new location of the College of California, Henry Durant, one of the trustees, gazing out over the Bay, quoted Bishop Berkeley's well-known line: “Westward the course of empire takes its way,” and another trustee suggested that they name the new town for the prophetic English philosopher. The village which grew up around the campus was not incorporated until 1878, organization having been delayed by farmers who rejected the idea of imposing the expense of municipal government upon them. By the turn of the century, however, streets had been paved, a reservoir built and pipes laid, residential tracts opened, and the electric trains supplemented the noisy and smoky locomotives of the Southern Pacific.

The San Francisco fire brought so many new residents that the town by 1908 was large enough to make an effort to get the State capital away from Sacramento. At the same time many attractive homes were being built among scattered clumps of oaks on the rising ground north and south of the campus. In the fall of 1923 a grass fire, starting in the hills, destroyed a large part of North Berkeley. New homes and gardens have gradually hidden the scars of the fire.

In the 1930 census the population figures were: 73 per cent native white, 23 per cent foreign white, 2 per cent Negro, and 2 per cent mixed. But the number of foreign students at the university is relatively high. In 1927, when International House was proposed, approximately 10 per cent of all the foreign students in the United States were registered at the University of California. The governments of Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa send many graduate students to Berkeley at government expense, most often to study soil chemistry or some other branch of agriculture. The Egyptian government sends students every year to study citriculture. Berkeley also draws many foreign students of engineering, particularly of petroleum engineering. Occasionally one sees East Indians of the commercial class walking respectfully behind and out of the shadow of the bearded and turbaned Sikhs of the military caste.

Berkeley became, in 1923, one of the first cities of its size in the United States to adopt the city-manager form of government. Its school department claims to have established the first junior high school in the country. Its standing in public health service is indicated by its proud boast that for two decades it has had one of the four lowest infant mortality rates among places of its size in the United States. But it prides itself most on its police department—built up by Police Chief August Vollmer, now retired—whose fame has extended as far away as Scotland Yard.

Vollmer encouraged his staff to experiment: as a member of the Berkeley police department in 1921 Dr. John A. Larson invented the lie-detector, a machine that records the tell-tale changes in heart action and breathing which usually accompany deviations from the truth. In 1921 Vollmer was elected president of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, and in 1929, although not himself a college graduate, he took leave of his command to head a department of research at the University of Chicago with the title of Professor of Police Administration—perhaps the first ever to hold such a title. Vollmer, who now gives regular courses in police administration at the University of California, is a firm believer in a college education for policemen—a fact which caused his men to be called “super-cops.” During summer sessions, it is not surprising to see a burly cop saunter out of a classroom, his gun on his hip and a student note book under his arm. As a result, Berkeley police have an unusual standing in the community.

POINTS OF INTEREST

1. The BERKELEY AQUATIC PARK (boating free with own craft; rowboats, sailboats, electric boats for hire), East Shore Highway between University and Ashby Aves., is a mile-long, ninety-acre recreational waterfront development built by WPA labor, containing a long, narrow, tide-filled lagoon with a landscaped border. In the southern end of the lagoon, set aside for model-yacht racing, regattas in which the diminutive copies of yachts compete are held occasionally. A small grass-covered island midway along the western shoreline is reserved as a wild fowl sanctuary.

2. The BERKELEY MUNICIPAL FISHING PIER (fee 5¢) extends more than three miles over the mud flats to deep water.

3. The BERKELEY YACHT HARBOR, north of the Municipal Fishing Pier, developed in part with WPA funds, will accommodate 500 small craft in waters protected by rock-faced earthen breakwaters.

4. The LAWN BOWLING GREEN, Allston Way west of Acton St., maintained by the city's Recreation Department, has been the scene of world championship tournaments.

5. MORTAR ROCK PARK, Indian Rock Ave. and San Diego Rd., once the site of Indian assemblages, is dominated by a huge irregular mass of rock, which commands a magnificent view of the surrounding territory. Here Indian women ground corn in the mortar-like rocks, whose smooth cylindrical holes still show the use to which they were put.

6. The seven-acre JOHN HINKEL PARK, Southampton Ave. and San Diego Rd., has an amphitheater seating 400, constructed in 1934 by the CWA, where plays are given by the Berkeley Community Players during the summer months.

7. CRAGMONT ROCK PARK, Regal Rd. at Hilldale Ave., covers four acres surrounding the freak rock formation for which the park was named. From the lookout station 800 feet above sea level is an excellent view of the Bay and its bridges. Easter sunrise services are held here.

8. CODORNICES (Sp., quail) PARK, Euclid Ave. at Bay View Pl., originally a steep, rocky, brush-grown gulch where quail were abundant, has been terraced by WPA workers as a rose garden, with tiers of roses of many varieties. The park has public tennis courts, a playground for children, and a clubhouse for community use.

9. The PACIFIC SCHOOL OF RELIGION (open to visitors on application), 1798 Scenic Ave., is a graduate theological seminary, interdenominational and coeducational, established in San Francisco in 1866 as the Pacific Theological Seminary. Moved the next year to Oakland, it was established here in 1925. Its present name was adopted in 1916 on its 50th anniversary. The school prepares students for all kinds of religious work. One department, known as the Palestine Institute, centers its activity in the Holy Land, where it is engaged in Biblical research.

The ADMINISTRATION BUILDING and the HOLBROOK MEMORIAL LIBRARY are of gray cut stone; the men's dormitory is of gray stucco. The library of 30,000 volumes includes a “Breeches” Bible, printed in Geneva in 1560; a group of Babylonian cuneiform tablets; a collection of fourth-century Biblical inscriptions on papyrus; and a rubbing of the inscription on the Nestorian monument in China. An archeological exhibit in the same building consists of relics dating from 3500 B.C.

For the past few years the Pacific Coast School for Workers has taken over the grounds of the Pacific School of Religion for its summer session. A member of the American Affiliated Schools for Workers, it is sponsored jointly by the Extension Division, labor organizations, the State Department of Education, and other interested bodies. Courses are conducted in San Francisco, but in the summer for six weeks union members come here from laundries, hotel kitchens, the water front, and other places of industrial activity to study economics, parliamentary law, and international affairs, in order to go back and better serve their organizations.

10. The HANGAR (adm. adults 25¢, children 10¢), 2211 Union St., “Mother” Tusch's aviation museum, is a little white cottage which has become a familiar spot to aviation fans. During the World War, when a school of military aeronautics was established on the campus, “Mother” Tusch founded the University Mothers’ Club to look after the boys away from their homes. Overseas flyers remembered the little white house and its motherly occupant, serving coffee and doughnuts, and sent her souvenirs from the battlefields. Among “Mother” Tusch's treasures is part of the fuselage of an Àrmy plane, on which is carved with a penknife the last message of its pilots, Lieutenant Fred Water-house and Cecil H. Connolly, who were forced down on the Mexican border in 1919. One of the most unusual tributes came from a German ace—a pair of silver wings, inscribed: “To the Mother of us all, with love from Capt. Willie Mauss.” Recent additions to the collection are the black sealskin cap worn by Admiral Richard Byrd in Little America and the small Bible which Lieutenant Clyde Pangborn carried on his flight around the world. On the walls of The Hangar are the signatures of Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, Colonel Billy Mitchell, Sir Hubert Wilkins, Byrd, Pangborn, and other famous flyers. Only one woman's autograph is there—that of Amelia Earhart.

11. BARRINGTON HALL, 2315 Dwight Way, is the largest of five co-operative dormitories built on the university campus during the depression. The five are organized into the California Students’ Cooperative Association, housing 365 men and 82 women. All the work is done by the members themselves, aided by one or two paid employees. Each student puts in about four hours of work each week, enabling him to obtain a room and three meals a day for about $22.50 a month.

12. The CALIFORNIA SCHOOL FOR THE DEAF, Warring and Parker Sts., at the foot of the Berkeley hills, is the only residential school of its kind in California. The course of study embraces a 12-year period, three years of which is preparatory work enabling the child to reach the level of the first grade of the public school system. The entire course is intended not only to give the handicapped child a general education, but also to prepare him for some occupation at which he can earn his living.

13. The CALIFORNIA SCHOOL FOR THE BLIND, 3001 Derby St., sharing the campus of the California School for the Deaf, serves visually handicapped children. Begun in San Francisco in 1860 as a private institution for the deaf, dumb and blind, it was taken over by the State in 1865 and moved to Berkeley two years later. Since 1922 it has been an institution solely for the blind.

14. The rambling, stuccoed CLAREMONT HOTEL, at the head of Russell St., erected in 1904, is surrounded by a large old-fashioned garden.

15. At the BERKELEY TENNIS CLUB (tournaments May-June, Sept.-Oct.), adjoining the Claremont Hotel, “Pop” Fuller developed two champion players, Helen Wills Moody and Helen Jacobs.

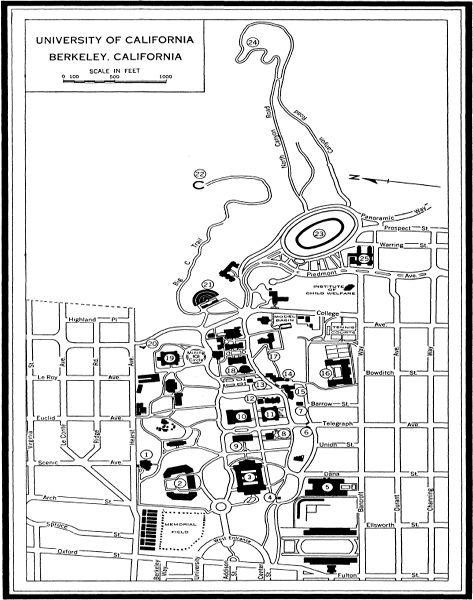

THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

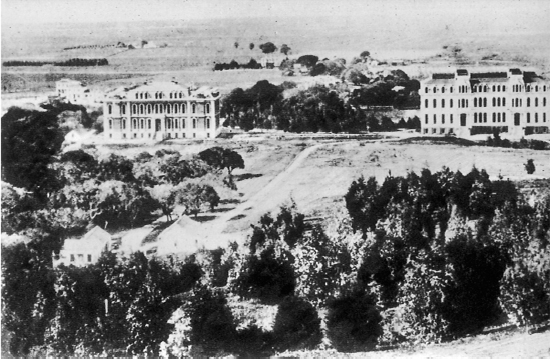

Until the turn of the century the University of California occupied a heterogeneous assortment of buildings at the base of the Berkeley Hills on oak-studded slopes traversed by two branches of Strawberry Creek; but in 1896 Phoebe Apperson Hearst awarded a prize of $10,000 for a campus design to Emile Bénard of Paris, and his general layout, with modifications, has since guided the development of the grounds. In 1902 John Galen Howard, an American architect who had studied at the École des Beaux Arts and had worked with Bénard, came to the university, established a School of Architecture, and became supervising architect. The architecture of the campus strongly reflects his influence. He changed many details of the Bénard plan, but French academic influence is apparent everywhere both in the buildings and in their relation to each other.

The beginning of the university dates to the California constitutional convention of 1849, when a clause was adopted providing for the establishment of a university. A subsequent delay of nearly 20 years was due partly to a controversy between those who wished to establish a “complete university” and those who wanted only a college of agriculture and mechanics. Meanwhile Oakland's College of California was chartered in 1855 by two ministers, Henry Durant and Samuel Hopkins Willey. Absorbing the Contra Costa Academy, it had in 1860 a faculty of six and a freshman class of eight. In 1867 the founders and trustees offered to disincorporate and transfer to the State all their assets—the buildings at Oakland, the 160-acre building site at Berkeley, and a 10,000-volume library. The State accepted the offer and on September 23, 1869 the new university opened in Oakland. In September, 1873 the buildings on the Berkeley campus were occupied by 40 students and a faculty of 10.

For many years the combined student enrollment of the University of California's various schools and colleges has made it the largest university in the country. In 1939-40, the enrollment of 16,199 on its Berkeley campus alone surpassed all others. Academically, the university ranks as one of the Nation's best. A survey made under the auspices of the American Council on Education in 1938 gave it a tie with Harvard for first place in a weighted rating of distinguished and adequate departments.

In the value of its “practical” contributions, the University of California has a fine record. Its benefits to agriculture alone are estimated to save California farmers $100,000,000 annually. In addition to experimental work in animal husbandry, horticulture, viticulture, and irrigation, the agricultural departments have developed and introduced to the farmer the spray plant, a device for spraying fruit trees and vegetation through underground pipes; the solar heater to prevent frost injury to orchard trees; the use of humified air for sterilizing dairy utensils; and a milk-cooling system. Boulder Dam, constructed under the direction of Dr. Elwood Mead, formerly of the university faculty, was built with a special low-heat cement developed in the Engineering Materials Testing Laboratory on the Berkeley campus. In the same laboratory test models of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge were made, while professors of geology were investigating the strata upon which the bridge foundations would rest. Materials used in Boulder Dam, the bridges, and many other public works were first tested by the university's materials testing machine, capable of exerting a pressure of 4,000,000 pounds. The engineering department, cooperating with the United States War Department, compiles data obtained at the university's hydraulic tidal testing basin to aid in the maintenance of ship channels and the preservation of beaches. In its laboratories was developed an improved method of treating leprosy. Vitamin E and the growth- and sex-stimulating hormones of the pituitary glands were discovered by Dr. Herbert M. Evans of the Institute of Experimental Biology. Through experiments conducted in university laboratories, the canning industry overcame botulism, the sugar beet pest was conquered, and the mealy bug eliminated from citrus groves.

Other studies include: consideration of the atmosphere on Mars; a study of living organisms found in a solid rock 225,000,000 years old; translation of a clay tablet from Mesopotamia, which upset accepted theories of how Babylon was governed. Less spectacular are the studies of unemployment, the migrant, and agricultural labor made at the request of State and local authorities by the Bureau of Public Administration, a pioneer in training students for government service.

Perhaps no contemporary piece of abstruse research so captured the imagination of the lay public and the respect of the world's scientists as did the invention of the “atom smasher” or cyclotron by Dr. E. O. Lawrence of the Radiation Laboratory of the Department of Physics. Dr. Lawrence has realized the dream of the alchemist of old, the transmutation of the elements, by bombarding them with his atom smasher. He has already achieved successful production of artificial radioactive elements in sufficient quantities to provide a cheap synthetic substitute for radium. Experiments are still being conducted in the use of the mysterious “neutron ray” in the treatment of cancer. For his work with the cyclotron, Dr. Lawrence was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1939. In the field of medico-therapy Dr. Lawrence and his staff have also developed a new type of X-ray apparatus capable of producing a continuous supply of X-rays with an energy approaching 1,000,000 volts, for treatment of tumorous growths.

Gifts to the university have been the basis for the establishment of its various schools and colleges—all, with the exception of those at Los Angeles and Berkeley, devoted to specialized fields of study. The Medical School, the Colleges of Pharmacy and Dentistry, the Training School for Nurses, and the Hooper Foundation for Medical Research are located in San Francisco, as are the affiliated College of Fine Arts and Hasting's College of Law. The College of Agriculture has, besides the curricula at Berkeley and Los Angeles, a farm at Davis, the Citrus Experiment Station at Riverside, the Institution of Animal Husbandry at Pomona, and the Forest Station in Tulare County. At Mount Hamilton is the Lick Observatory; at La Jolla, the Institution of Oceanography. Perhaps the most significant evidence of growth was the establishment of the southern branch of the university in Los Angeles in 1919. Beginning with freshmen and sophomore work, it added advanced curricula as the need arose, until in 1927 it received equal rank with the Berkeley institution as the University of California at Los Angeles. Today, in the words of a recent university publication, a California student pursues his studies at whatever campus, school, or research station best suits his needs, because California “has grown from a local school to a state-wide clearing house of knowledge gathered from all corners of the earth.”

The Golden Book of the Alumni Association, published in 1936, listed alumni in the four corners of the earth, including a chief engineer for public works in Madras, the manager of a government ranch at Bagdad, a cotton breeder for the Department of Agriculture in Bombay, a chief of the Associated Press for the Balkans, a gold-dredging expert in New Guinea, and a professor in Leningrad College. David Prescott Barrows, Chairman of the Department of Political Science, tells a story which illustrates the way in which alumni bob up in the most unexpected places. In 1917 he was assistant chief of staff in the American Expeditionary Force in Siberia. After an interview with General Semenoff, in charge of White Russian forces at Chita, General Barrows was assigned, as aide-de-camp, a magnificent-looking Cossack dressed in Asiatic splendor. General Barrows was amazed to hear him say mildly, in excellent English, “You don't know me, General, but I have seen you many times on the Berkeley campus. I was a student for two years at your College of Mining.”

CAMPUS POINTS OF INTEREST

I. The PRESIDENT'S HOUSE (private), Hearst Ave. and Scenic Ave., built in 1911 for use as the official residence of the university's executive head, stands on a slight eminence near the north edge of the campus. It is of grey-brown sandstone, with a portico supported by Ionic columns and guarded by marble lions.

2. AGRICULTURE, HILGARD, AND GIANNINI HALLS, built in Italian Renaissance style of white concrete, range around a C-shaped open court near the northwest corner of the campus. They house the College of Agriculture and the Agricultural Extension Division. Nearby are greenhouses (open to students only) for experimental work. In the corridors of Giannini Hall is a display of colored hardwoods from many parts of the world.

3. The LIFE SCIENCES BUILDING, Harmon Way between Axis Rd. and Campanile Way, is a massive concrete structure, completed in 1930. On the facade are panels and rosettes in which have been cast conventionalized representations of fish, reptiles, and mammals. Laboratories, classrooms, offices, and libraries of 13 life-science departments occupy the building, which also houses the Institute of Experimental Biology; the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (for students only) with its 160,000 specimens of mammals, birds, and reptiles; and the herbarium of the Department of Botany (open 8:30-12, 1-5; Sat. 8:30-12), containing some 500,000 plant specimens from all over the world.

4. The TILDEN FOOTBALL STATUE, Campanile Way west of Life Sciences Bldg., is a bronze statue of two rugby players, by Douglas Tilden, presented by Senator James D. Phelan in recognition of the superiority of the university football teams of 1898-99.

5. The GYMNASIUM FOR MEN, Dana St. between Bancroft and Allston Ways, completed in 1933, has large gymnasium floors and swimming pool, special rooms for wrestling, boxing, and fencing and space for badminton and table tennis. Adjoining it are a baseball diamond and the George C. Edwards Memorial Stadium for track and field sports.

6. SATHER GATE, at the head of Telegraph Ave., most used entrance to the campus, is an ornamental structure of concrete and bronze, erected in 1909 with funds provided by Jane K. Sather as a memorial to her husband, Peder Sather. “To go outside the gate” is an established tradition for student assemblies which do not have the sanction of the university authorities.

7. The ART GALLERY (open weekdays 10-5), one block E. of Sather Gate, is a former power house. The two large mosaics on the facade, symbolizing the seven arts, were designed and executed in Byzantine style by Helen Bruton and Florence Swift, assisted by workers of the WPA Federal Art Project. The gallery owns the Albert Bender collection of oriental art and a collection of Russian ikons.