Emporium of a New world

“… San Francisco…the sole emporium of d new world,

the awakened Pacific…”

—RICHARD HENRY DANA

HARDLY had the dead hand of Mexican rule been lifted from the Bay region when the Gold Rush struck it like a hurricane. The thousands who flocked to the shores of San Francisco Bay in 1848 at first asked little. But when the excitement died down the little gold frontier town had become a city, and its people demanded much: wharves, and dry paved streets; homes and stores, with firm foundations on which to build them; and a transportation system that would encompass not only the land about the Bay, but the Bay itself. Almost overnight the fleet of steamers and sailing ships which glutted with the manufactured products of Eastern merchants the wharves of San Francisco, Stockton, and Sacramento established the Bay's maritime supremacy on the Pacific Coast.

Mining camps developed into towns and cities amid the rich agricultural lands of the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys; and around the old pueblos of San Jose and Santa Clara the vast ranchos of the Mexicans and Spaniards became orchards, fields, and vineyards. From these, and from the soil of Sonoma County, from Napa Valley and from the counties of the contra costa, would come the “green gold” which a vast system of canneries and packing houses now prepares for distribution all over the world. To supply this populous hinterland with commodities, and to bring down to the harbors of the Bay its tons of exports, a network of railroads and highways, bridges and improved inland waterways had to be established. Throughout almost a century Bay region industrialists, farmers, and shippers have had to struggle with problems of engineering to overcome deficiencies in an area otherwise ideally suited to the building of prosperous communities and metropolitan centers.

For all its magnificence and its utility, San Francisco Bay was, until completion of its two great bridges, an obstacle to transportation which prevented development of large sections of Marin County; and it isolated the industrial centers of the East Bay from financial and distribution facilities of San Francisco. Phenomenally rapid as its progress has been, this new unity, which engineering has accomplished, assures a future of more intense and orderly development for all communities of the Bay region.

Today, the San Francisco Bay region is the market place and workshop for a population of nearly 2,000,000 people—a great harbor ringed with factory smokestacks, sheltering vessels from all ports of the globe, terminus of transcontinental railroads and airlines and home base of the Pacific Clippers flying to the Orient. Ranking second in value of water-borne commerce of all United States ports, the San Francisco Bay area has become the Pacific Coast's largest distribution center and the West's financial capital. Among 30 industrial areas of the Nation, it ranked sixth as a manufacturing center, with an industrial output of more than $800,000,000 in 1935. Its wholesale trade volume of $1,353,710 the same year was larger than the value of its water-borne commerce; and the value of its retail trade was half as large.

WORLD PORT

John Masefield's “dirty British coaster with salt-caked smokestacks” is but one of the myriad craft, from nations all over the world, which have come and gone through the Golden Gate since Lieutenant Manuel de Ayala's little San Carlos first dropped anchor in San Francisco Bay in 1775. Across the racing tides of that narrow channel have swept the white sails of the clipper ships that brought the Argonauts; through it have steamed sidewheelers and modern freighters, sleek liners and palatial yachts, naval armadas and army transports; and casting brief shadows of the future upon it, and upon the mighty bridge which spans the strait, the silver wings of clipper planes go soaring out across the Pacific.

The pioneer Pacific Mail Steamship Company's 1,000-ton side-wheeler, California, already had sailed from New York for the Pacific Coast by way of Cape Horn, with no passengers, when the news of the discovery of gold in California reached the East. When the California anchored at Panama on January 30, 1849, she found hundreds of frenzied gold-hunters who had made their way across the Isthmus awaiting her. On February 28, topheavy with several times her capacity of 100 passengers, she steamed through the Golden Gate—the first vessel to round Cape Horn under her own steam and sail into the Bay of San Francisco. Pacific Mail promptly hurried completion of two sister ships; but these were not enough. Its fleet rapidly grew to 29 steamships destined to carry 175,000 people to San Francisco within a decade.

During the height of the Gold Rush, however, demand so far outdistanced supply in the maritime industry that chaos reigned, retarding for several years development of regular and systematic commercial facilities. The rapid increase in population—from about 860 to almost 42,000 by the end of 1852 in San Francisco alone—brought a wide and insistent demand for manufactured goods, tools, machinery and food products which undeveloped local industry could not supply. Eastern shippers, without accurate knowledge of local requirements, sent tons of merchandise for which San Francisco could find no use. The market was glutted; prices crashed; goods of every description were left to rot in the holds of ships, on the wharves, and in the city streets. Fully as demoralizing to maritime commerce was the wholesale desertion of ship's crews, who joined the wild rush to the mines. San Francisco Bay in the early fifties presented a sight seldom seen in the history of the world: a veritable forest of masts rising from hundreds of abandoned ships.

With the gradual stabilization of trading conditions, however, maritime commerce was revived until the rapid increase in shipping made necessary the immediate building of extensive piers and docking facilities. Prior to the Gold Rush all cargoes had been lightered ashore in small boats, usually to the rocky promontory of Clark's Point at the foot of Telegraph Hill. When in the winter of 1848 the revenue steamer James K. Polk was run aground at the present intersection of Vallejo and Battery Streets—at that time part of the water front—the narrow gangplank laid from deck to shore was considered a distinct advance in harbor facilities. The brig Belfast was the first vessel to unload at a pier: she docked in 1848 at the newly completed Broadway Wharf—a board structure ten feet wide. Others were soon built. By October 1850, 6,000 feet of wharfage had been constructed at a cost of $1,000,000. As the tidal flats were filled in, the piers were extended: Commercial Wharf, at first extending only 30 feet into waters only two feet deep, became Long Wharf as it was lengthened to 400 feet to provide docking facilities for deep water shipping.

During the boom years of the 1850’s competition between Eastern shippers became so sharp that a type of sailing vessel faster than the old schooners and barques constructed on the lines of whaling ships had to be built. Between 1850 and 1854, 160 fast clipper ships were launched on the Eastern seaboard to supply the demand for speed and more speed to the Pacific Coast.

“On to the mines” was the order of the day for both passengers and cargoes landed on San Francisco's water front. The fastest way to the mines was by water—through San Pablo Bay, Carquinez Strait, and Suisun Bay, and up the San Joaquin River to Stockton, or up the Sacramento to the town named for it. The first steamboat in the Bay, the 37-foot sidewheeler Sitka, imported in sections from the Russian settlement at Sitka, Alaska, and reassembled, had already attempted the trip to Sacramento, requiring six days and seven hours. Vessels better equipped for the journey were soon imported. Meanwhile, lighter craft were pressed into traveling service. Since 1835, when William A. Richardson had begun operating two 30-ton schooners with Indian crews to transport the produce of missions and ranches from San Francisco and San Jose to trading vessels anchored in the Bay, a variety of small vessels had plied the waters inside the Golden Gate. In 1850 Captain Thomas Gray's propeller steamer Kangaroo began the first regular run, twice weekly, between San Francisco and San Antonio Landing (now Oakland) in the East Bay. On September 2, 1863, the San Francisco and Oakland Railroad Company, first in the Bay region, began running the Contra Costa six times daily from its Oakland wharf to Broadway Wharf in San Francisco; and the following year, the San Francisco and Alameda Railroad Company inaugurated train-ferry service from Alameda Wharf with the Sophie McLane. At the Alameda Wharf, on September 6, 1869, the steamer Alameda took on the first boatload of passengers arriving on the Pacific Coast by transcontinental railroad.

After the opening of ferry slips at the two-mile Oakland Long Wharf in 1871 and at a new San Fransisco passenger station at the foot of Market Street four years later, the ferry fleet grew rapidly in size. In 1879 the world's largest ferry, the Solano, began transporting whole railroad trains across Suisun Bay from Benicia to Port Costa. The ferry system was extended until by 1930 the 43 boats operating between San Francisco and Oakland, Alameda, Berkeley, Sausalito, and Vallejo comprised the largest transportation enterprise of its kind in the world; in that year they carried a total of more than 40,000,000 passengers.

The lifting of the Mexican regime's restrictive measures against foreign trading brought the Pacific whalers to San Francisco. As early as 1800, whaling vessels had begun to anchor in sheltered Richardson's Bay, then known as Whaler's Bay, off the site of Sausalito, where they took on wood and water. The first captain of the port, shrewd William A. Richardson, had collected fees for piloting the whalers to their anchorage. But Mexican regulations and tariffs forced the whaling industry to base its operations in the Sandwich Islands. After American occupation, San Francisco merchants, foreseeing profits to be gained from yearly outfitting of the whalers and their crews, made hardy efforts to center the industry here. They succeeded to such an extent that by 1865 a total of 34 whalers, with a combined tonnage of 11,000 tons, anchored in the Bay.

As late as 1888, San Francisco was still Pacific Coast whaling headquarters. But the whaling fleet dwindled rapidly after 1900—as tugboats for pursuit (“killer” ships) and steam-driven processing plants (factory ships) supplanted sailing vessels—until in 1938 the California Whaling Company, sole survivor in the industry, called in for the last time its remaining ships.

Within two decades after the building of its first wharf, the tip of the San Francisco Peninsula was saw-toothed with piers. The water front had been pushed into the Bay as the shallow waters of Yerba Buena Cove were filled in. In 1873, two years after control of the San Francisco water front had been acquired by the State, the construction of a great sea wall was begun by the State Board of Harbor Commissioners; and in 1878, the 200-foot wide Embarcadero was laid out. San Francisco's great era of maritime commerce was entering into the full stride of its phenomenal development.

While shovels and picks and gold pans rusted in thousands of back yards, the State turned from gold mining to agriculture and manufacturing. Sacramento and Stockton, great mining centers during the Gold Rush, became agricultural capitals of northern California. The two great rivers sweeping inland to these cities became arteries of commerce. Barges and river boats stopped at numberless docks and landings to pick up the diversified products of the rich land that swept for miles on either side of the broad rivers. And the products of the great agricultural hinterland, flowing into San Francisco Bay, contributed heavily to its export trade. From 1860 to 1875 exports from San Francisco grew in value from $8,532,439 to $33,554,081. By 1889 the figure had increased to $47,274,090 and imports had grown correspondingly in value.

The era of the clipper ships, which had abandoned the San Francisco run and entered the China trade, had given way to a new phase of shipping which called for the transport of heavy industrial products and for the expansion of foreign trade. Successors to the clipper ships were square-rigged sailing vessels, sturdily built, with spacious holds, for carrying heavy cargoes of freight, fish, and agricultural products. Only when displaced by the fast freight steamers of the late nineteenth century did the square-riggers pass from the shipping lanes and from San Francisco Bay. The ships of the Alaska Packers’ fleet, last of these great windjammers, were dismantled early in the 1930’s. Meanwhile the first of the roving cargo carriers known as “tramp steamers” had passed through the Golden Gate in 1874. By the end of the following year more than 30 of these vessels had arrived. Their number increased rapidly until the rise late in the century of the great modern steamship lines, which absorbed the independent shippers who had dominated the pioneer era. By the middle 1870’s the growth of logging camps and sawmills in the timber regions of the State had also created a demand for large fleets of freighters.

Regular monthly service for freight and passengers was established between San Francisco and the Orient in 1867 by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, which had for several years prior been transporting thousands of Chinese coolies to supply the demand for cheap labor during the building of the Central Pacific Railroad. By 1878 the Pacific Mail had established regular sailings to Honolulu, carrying merchandise which was exchanged for raw sugar, pineapples, coffee, and hides. Five years later the Oceanic Steamship Company entered this lucrative field of trade, and in 1885 extended its service to the ports of Australia and New Zealand. Within the following decade the names of William Matson and Robert Dollar were becoming known in maritime circles. As sea-borne commerce expanded during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, other lines developed. Among these pioneers of American shipping on the Pacific Coast were the American-Hawaiian, United Fruit, and Panama-Pacific Lines. The Kosmos Line, later absorbed by the Hamburg-American Steamship Company, inaugurated the first monthly sailings to Hamburg and other European ports in 1899. By 1916 the American-Hawaiian Steamship Company's fleet of 26 steamers with a capacity of 296,000 tons was said to be the largest tonnage under single ownership operating under the flag of the United States.

When the Panama Canal was opened in July 1914, the maritime commerce of San Francisco Bay entered its modern epoch of expansion. Along San Francisco's Embarcadero, until the outbreak of the war at the end of 1939, were represented almost 200 steamship companies whose vessels, both of domestic and foreign registry, called at nearly every port of the seven seas. Of these, at least half were engaged in coastwise, intercoastal, or transatlantic trade service (via Panama Canal); the others trade with Mexico and Latin America, Hawaii, Australia and the Orient, the African coasts, or offered round-the-world passenger service. From Puget Sound to Madagascar are known the huge dollar-sign insignia of Dollar Steamship Company ships (lately superseded by the spread eagle of the American President Lines), the blue-and-white smokestacks of California and Hawaiian, and the Matson Line's substantial “M.” No less familiar to San Franciscans and other Bay region residents are neat Dutch liners and freighters bound for Rotterdam or Antwerp out of Batavia in the East Indies, for which San Francisco was a regular port-of-call. The ships of Japan, British ships from India and east African ports, ships from the Scandinavian countries and the Balkans were seen alongside piers of San Francisco's water front or in other harbors around the Bay. Most commonplace of all, however, are those coastwise freighters which butt in and out of ports all the way from Vancouver to Valparaiso.

Among San Francisco's chief imports today are copra, sugar, coffee, and vegetable oils; paper and burlap; fertilizer and nitrates. Chief exports are petroleum products; canned, dried, and fresh fruit; lumber; flour and rice; canned and cured fish; explosives and manufactured goods. Between 1926 and 1936 San Francisco shipped 63 per cent of the total volume of canned, and 70 per cent of the dried, fruit exported from the Nation. In return for the goods which it ships away, San Francisco Bay receives from the whole Pacific Basin its products for distribution throughout the West. Of the 35,000,000 tons of inbound and outbound cargo cleared by California ports in 1935, San Francisco Bay handled 17,000,000. In total commerce it ranked fourth among all commercial centers in the country.

The Port of San Francisco is much more than the 17½ miles of berthing space which flank San Francisco's Ferry Building on either side. Actually it consists of the series of bays extending northeast from the Golden Gate to the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers and southward almost to San Jose. Harbor facilities are supplied by the half-dozen cities and industrial centers scattered along 100 miles of shoreline enclosing 450 square miles of water. These ports within a port are as interdependent as are the economies of the different cities and towns of the Bay region.

Thus a vessel in from the Hawaiian Islands may discharge pineapple at San Francisco and raw sugar at Crockett before proceeding to the Port of Oakland to take on a cargo of canned and dried fruits for the Orient, or a coastwise vessel up from Nicaragua or Honduras with a hold full of green coffee will unload at San Francisco before crossing to Oakland for automobiles for South or Central America. A tanker coming in through the Gate may steam directly to the Standard Oil docks at Richmond, or the Shell pier at Martinez; or it may make for the Selby Smelting Company's wharf at Selby.

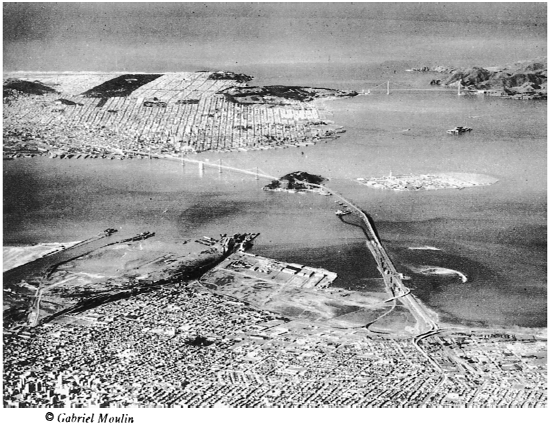

An air view of San Francisco Bay's littoral—its miles of public and private wharfage; its manifold industrial plants crowding the water's edge; its deep-water anchorage for warships; its airports and islands and dockyards—will alone reveal the stupendous picture of this port. And in October 1936 travelers to and from San Francisco Bay were provided with such a view when Pan-American Airways launched the first transpacific commercial passenger flight to Manila. To the historic roll call of ships which have sailed through the Golden Gate—San Carlos, California, Flying Cloud, galleons and square-riggers, whalers and tramp steamers—was added one more name: China Clipper.

SMOKESTACKS AROUND THE BAY

Less than a century spans the interval between the primitive looms and forges, kilns and winepresses of the missions around the Bay and the giant factories, shipbuilding yards, and refineries with their soaring smokestacks that congregate about the water's edge today. Where cattle grazed the lonely hills—almost within the memory of living men—furnishing hides for the illicit trade with Yankee sea captains, now rise Contra Costa's sugar and oil refineries, steel mills, explosive and chemical plants. Where whaling boats embarked from San Antonio Landing to carry wild fowl, bear, and deer across the Bay to market, now spreads the East Bay's crowded belt of canneries and factories. And where whalers and hide traders once tied up on the other side of the water, San Francisco's printing and coffee roasting plants, meatpacking and canning establishments crowd to the shore.

The infant city by the Golden Gate grew rich overnight as industries sprang up to supply and outfit the Gold Rush population. Within little more than a decade after Stephen Smith had established his steam-powered grist- and sawmill—California's first—at Bodega in 1843, San Francisco had built stagecoach and wagon factories, flour mills, and breweries. Boot and shoe factories and plants for the grading and manufacture of wool endeavored to fill the need for clothing and blankets. As was natural in a city which was in the habit of burning down two or three times a year, lumber mills flourished. To supply the miners’ demands for picks and shovels and pans, the Donahue Brothers established their foundry (later the Union Iron Works) as early as 1849. Since metal was scarce, San Francisco's pioneer machine shops and iron moulders were soon hammering iron wagon wheel rims and harness chains into miners’ tools.

After the overland railroad began providing transportation to and from the East for both freight and passengers in 1869, San Francisco's industries expanded rapidly. The development of quartz mining and the growth of large-scale agriculture spurred the manufacture of mining and milling equipment. Other leading industries during this era, in order of importance, were breweries and malt houses, sash and blind mills, boot and shoe factories, tin-ware manufacturing, flour milling, and wool grading and manufacture. Of lesser importance were the tanneries, coffee and spice processors (now one of the city's leading industries), rolling mills, box factories, soap works, cracker factories, and packing plants. Over all, annual industrial output for the two decades of 1870-90 rose from $22,000,000 to $120,000,000.

The rapidly expanding mining industry had created a tremendous demand for special mining machinery. By 1860 San Francisco had 14 foundries and machine shops employing 222 men and turning out nearly $1,250,000 worth of products annually. With the development of quartz mining and the growth of mining in Nevada, it became the undisputed Western capital for mining machinery. But mine machinery did not long remain the sole concern of local industry and soon, with typical audacity, the comparatively inexperienced machine shops of San Francisco blithely were turning out such complex pieces of workmanship as railway locomotives, flour mills, steamships and lesser objects of everyday utility. By the end of the nineteenth century, San Francisco's machine shops constituted an industry of international stature, supplying flour-milling machinery and equipment for the entire Pacific area, including such widely separated places as South and Central America, Japan, China, Mexico, New Zealand, Siberia, and Australia.

When the miners turned away from the creeks and climbed the hills to follow the quartz ledges, they needed explosives. It was in San Francisco in 1867 that Julius Bandmann took over exclusive rights to manufacture dynamite under the Nobel patents. At his plant in Rock Canyon he put together and discharged two pounds of dynamite—the first, so far as can be determined, ever to be manufactured in the United States. In 1888 he moved his plant to Contra Costa County, where it became the Giant Corporation, a subsidiary of the Atlas Corporation. As the West began tearing down whole mountains to dam rivers and blasting highways along granite cliffs, other explosive manufacturing plants were opened—the Hercules at Pinole and the Trojan at Oakland.

In 1865 Thomas Selby, a San Francisco hardware merchant, built a tall tower at First and Howard Streets for the purpose of dropping lead shot. But the lead ore, mined in California and Nevada, had first to make the long trip to Europe for smelting. Selby began to smelt the ore himself in a small plant in North Beach. The business grew and he moved, first to Black Point, then to Contra Costa County. In 1905 the Selby plant was taken over by the American Smelting Company. Its tall chimney can be seen for miles around. Some of the ore from the famous mines of California and Nevada has been treated there—antimony, lead, silver, and gold, including all of the latter two metals needed by the United States Mint in San Francisco.

Another industry which had gained an early foothold in San Francisco was sugar refining. The story of how a German immigrant boy, Claus Spreckels, graduated from his small San Francisco grocery business to become a millionaire sugar tycoon is typical of the swashbuckling manner in which many robust San Francisco pioneers acquired fortune and fame. Captain Cook, discovering the Sandwich Islands—later the Hawaiian Islands—in 1788, commented on the size and fine quality of the sugar cane he found growing there. Until Spreckels became interested, all the cane from the Islands passed through San Francisco on its way to the East to be refined. Acquiring an early interest in Hawaiian plantation lands when he won part of the island of Mauai in a poker game with Kalakaua, the island king, Spreckels built a refinery here in 1863. Dissatisfied with results, he sold out and went to Germany, France, Austria, and Belgium to study the latest methods of refining. Returning to San Francisco, he built a second refinery. In 1882 he moved his plant to the water front at the foot of Twenty-third Street, where ships from the Islands could unload the cane directly into the refinery. There he installed improved methods of refining. It is this plant, enlarged and reorganized, which today is the home of the Western Sugar Refinery.

The California and Hawaiian Sugar Refinery at Crockett in Contra Costa County, a comparatively late comer, has developed into a giant corporation that grows, mills, refines, and distributes—as sugar and sugar products—nearly 80 per cent of all the cane that comes from the Hawaiian Islands.

Men who had come to dig gold in California had remained to farm. Soon California's fertile inland acres were sprouting the “green gold” for which the State was to become world famous. Even before the great wheat farms of the 1870’s and 1880’s had been supplanted by fruit and vegetable ranches, a few men had foreseen that this “green gold” might be shipped to the whole world if only it could be preserved against perishability, and packaged.

In 1854 Daniel R. Provost, member of an Eastern fruit preserving firm, had stepped ashore in San Francisco to represent his company here. He rented a small building on Washington Street, where he repacked Eastern jellies in small glass containers. Two years later he enlarged the business and began to make preserves and jellies from California fruits. This was the first time native fruit had been preserved commercially on the Pacific Coast.

Francis Cutting came three years later. He went into the fruit and vegetable-preserving business on Sacramento Street, where his unusual window displays attracted hungry customers. He added tomatoes to his line of products and in 1860 received a shipment of Mason jars which were well received in San Francisco. People began to refer to San Francisco as a fruit-packing center.

In 1862 Cutting received from Balitmore his first shipment of tin plate, at a cost of $16 a box. That year he shipped California canned fruit to the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City, to the Continental Hotel in Philadelphia and to the Parker House in Boston. He canned 5,400 cases of California fruit in 1862. California's giant canning industry was born. In 1899 eleven pioneer companies merged to become the California Fruit Canners Association. The industry expanded rapidly.

San Francisco developed a luxury line of fruits and vegetables put up in glass containers and the Illinois Glass Company arrived in Oakland to provide the jars. Typical of the canning industry today is the California Packing Corporation—Calpak—which owns 71 canneries, warehouses, and dried fruit plants, and many thousands of acres of fertile California lands. In the delta region, where the two great rivers empty into the Bay, Calpak owns 9,000 acres, 5,000 of which are planted to asparagus. According to a 1937 census the product of Bay area canneries that year was valued at $49,920,161.

Despite the fact that no oil is produced within 300 miles of the Bay, the center of its oil industry, Contra Costa County, has developed, in the brief interval since a China-bound steamer sailed west with a cargo of oil in 1894, the clearing house for one-eighth of the entire world's supply of gasoline and petroleum products. All the way from the San Joaquin Valley's southern end, where oil was discovered late in the nineteenth century, pipes were laid to connect with Bay shore refineries. Standard Oil was the first of the large companies to build one; its Richmond plant was opened soon after the first ferry connection was made with San Francisco. It put out one of the early wharves at Point Orient, linking the East Bay directly with the Far East by means of its tankers. Today four of the world's largest refineries overlook the water from San Pablo Bay's southern shore.

Sugar, canning, oil—these are the Bay region's industrial giants. For the most part, their operations are centered across the Bay from San Francisco. Long the West's chief industrial center, San Francisco had passed its zenith as a manufacturing city by the turn of the century. In its place, the East Bay came forward as factories found industrial sites cheaper and rail connections more convenient on the mainland. The city of San Francisco itself assumed its present role of financial and marketing center for an industrial area embracing the whole Bay region—that of front office for the plants across the water. Although outranked in economic importance by both wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing nevertheless contributed 22 per cent of the city's annual pay roll in 1935. As befits a commercial and financial center, the printing and publishing industry—important ever since the Pacific Coast's first power press was set up in April 1850—leads all the rest, with an output valued in 1937 at more than $40,000,000. The city's next most important industries are those of food-processing—the coffee and spice (by far the most important), bread and bakery products, meat packing, and canned fruit and vegetable industries.

Along the shores of Alameda and Contra Costa Counties stretches an industrial belt of bewildering complexity. At Emeryville, for instance, are situated no less than 35 concerns of national reputation, with products ranging from light globes to corsets, from canned fruit to preserved dog food. Oakland is coming to be known as the “Detroit of the West,” for Eastern automotive tycoons, to pare transportation costs, have built their assembly plants here. There are three General Motors plants in Oakland, a Ford plant in Richmond, and a Chrysler plant in San Leandro. Fageol trucks of Oakland are found high up among the mines of the Andes Mountains; huge tractors built by the Caterpillar Tractor Company of San Leandro are shipped all over the world. In 1921 the Atlas Imperial Diesel Engine Company of Oakland built the first solid injection marine Diesel engine to be manufactured with commercial success in America. The Union Diesel Engine Company, which has been building gas engines since 1885, supplies the means of motive power for boats of the United States Navy, the United States Bureau of Fisheries, and of the Arctic Patrol of the Canadian Northwest Mounted Police. The 400-acre plant of the Bay region's steel center, Pittsburg, recalling the giant mills of its Pennsylvania namesake, provides steel for many of the West's biggest construction jobs. Organized in 1910 by a group of San Francisco financiers, Columbia Steel (now a subsidiary of United States Steel) owns its own coal and iron mines, blast furnaces and coke ovens in Utah.

In 1940, only a few years short of the hundredth anniversary of gold's discovery, more than 3,000 industrial plants crowd the shores of San Francisco Bay, employing nearly 90,000 workers and producing goods valued at more than $1,000,000,000. Almost 71 per cent of central California's population of 3,000,000 people live within a 75-mile radius of San Francisco—still the hub of a great marketing area as it was in Gold Rush days. Now as then it is the San Francisco Bay region's job to supply their needs—and now, too, the needs of millions more beyond the horizons of a wider expanse, the whole Pacific.

ENGINEERING ENTERPRISE

The discovery of gold brought thousands clamoring to the muddy shores of the shallow indentation known as Yerba Buena Cove, which extended in an arc from the foot of Telegraph Hill to the present Montgomery Street and around to the foot of Rincon Hill. One of the first acts of the newcomers as a corporate body was to begin grading away the sand hills along Market Street and dumping them into the mud flats of the cove. The project was many years in completion. Before it was finished, about 1873, they had already begun building a sea wall several blocks east of the shoreline so that ships could unload directly upon the wharves without the aid of a lighter.

The construction of the sea wall, a stupendous project for its time, took many decades to complete. A trench 60 feet wide was dredged along the line of the proposed water front, and tons of rock blasted from Telegraph Hill were dumped into it from lighters and scows. The rocks were allowed to seek bed-rock of their own free weight; when settling ceased, a layer of concrete two feet thick and ten feet wide was laid on top of the resulting embankment.

While this work was going on, the reclamation of the mud-flats and shallows of the original cove was progressing. Some of the city's lesser hills were dumped bodily into the area between the old water front and the new sea wall until the business and financial district of lower Market Street—everything east of Montgomery Street—arose from the sea.

Agitation for rail connections to link the Bay with the outside world had begun as early as 1849. By 1851, $100,000 worth of stock had been sold for a projected line between San Francisco and San Jose. Three successive companies achieved little; but the fourth not only reached Menlo Park, but extended its line down the Peninsula to San Jose and was completed January 16, 1864. September of 1863 had seen completion of the San Francisco and Oakland Railroad Company's line from downtown Oakland to the Oakland ferry wharf.

Meanwhile, San Francisco's “Big Four” were pushing their Central Pacific rails over the mountains to join the Union Pacific in Utah. The first transcontinental railroad, completed in May 1869, extended only as far west as Sacramento. But the “Big Four,” determined that San Francisco should be the focal point of a country-wide network of railroad lines, systematically acquired control over every means of entry to the Bay region from all directions. Having bought a short railroad between Sacramento and San Jose, they built a branch to Oakland, purchased the two local roads connecting Oakland and Alameda with the East Bay water front; and taking over another line between Sacramento and Vallejo, they extended it to Benicia, where they inaugurated ferry service to carry their trains across Suisun Bay, installing the world's largest ferryboat for the purpose. Finally they bought the San Francisco and San Jose Line. The Bay was encompassed by the tracks of the “Big Four.”

“The railroad has furnished the backing for a great city,” reported the San Francisco Bulletin, “and the need now is for a thousand miles of local railroads in California.” The four went about answering the need. They completed a line southward to Los Angeles through the San Joaquin Valley on September 5, 1876. Their monopoly of rail transportation was unchallenged until completion in 1898 of a competing line financed by popular subscription, which was sold in the same year to the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad Company. The “Big Four,” meanwhile, were gradually extending the original San Francisco and San Jose line until in 1901 it stretched all the way down the coast to Los Angeles. On August 22, 1910 the Western Pacific line from Oakland through Niles Canyon, Stockton, Sacramento, and the Feather River Canyon to Salt Lake City was opened to traffic. By joint agreement in 1904 the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe began consolidating a group of short lines in the northern coast counties—including the San Francisco and North Pacific from Tiburon to Sherwood and the North Shore from Sausalito to Cazadero—into one line extending from the tip of the Marin Peninsula northward to Trinidad, near Humboldt Bay, finally opened November 17, 1914.

Meanwhile a growing San Francisco had spread beyond the limits set for it in the imagination of its first settlers. Tycoons of mine, ship, and railroad began to build grotesque, grey wooden mansions, tired-looking beneath their burdens of architectural bric-a-brac, on the city's highest elevations. They then were confronted with a new, and purely local, problem of transportation—that of devising a vehicle capable of surmounting hills too steep for horses. The result was the invention, by local manufacturer Andrew S. Hallidie, of the cable car. The inaugural trip of the first car, over the newly laid line on Clay Street between Kearny and Jones Streets, was a civic event. On the morning of August 2, 1873, the unfinished car was sent down the hill and back. That afternoon a public trial trip was made: many people climbed into and upon the car, which was intended to hold only 14, but in spite of the overload, it literally made the grade. Thirty days afterward the line was put into regular operation. The principle of cable traction was not new. The crowning engineering achievement lay in adapting it to street transportation—in solving the problem of how to make a moving cable follow the contour of the street and how to devise a grip which could not tear the cable apart by too sudden a jerk. The cars promised in their day to become the prevailing type of public conveyance in all of America's larger cities. They still survive in the city of their birth, an antique touch in a streamlined world.

Before introduction of the cable car, horse cars and omnibuses had been the prevailing means of street transportation. The first such line, starting in 1852, had been the “Yellow Line,” a half-hourly omnibus service which carried 18 passengers at a fare of 50¢ apiece from Clay and Kearny Streets out the Mission Street plank toll road to Mission Dolores. In 1862 the first street railroad on the Pacific Coast had begun providing service from North Beach to South Park. A steam railway began operation on Market Street in 1863, but sand and rain repeatedly filled the cuts, and omnibuses constantly obstructed the tracks and in 1867 horse cars were substituted. Even after cable car tracks were installed on Market Street (hence the name “South of the Slot” for the district south of Market) a horse car line paralleled them until 1906. An electric line was in operation on Eddy Street as early as 1900. In 1902 began the unification of all the city's lines, except the California Street cable, into one system, predecessor of today's Market Street Railway Company. The first line in the long-planned Municipal Railway—first city-owned street railway system in the United States and second in the world—was the Geary Street, put into operation in 1912. There are now 378.35 miles of street railway and bus lines in San Francisco.

On September 11, 1853, the consciously progressive city by the Golden Gate had made another—and very different—stride toward conquering the distances that lay between the communities of men. On that date was opened for use the first electric telegraph on the Pacific slope, connecting the San Francisco Merchants’ Exchange with six-mile-distant Point Lobos. It was built to announce the arrival of vessels at the Gate (previously signalled to the town by the arms of the giant semaphore atop Telegraph Hill). Two days later, James Gamble started out from San Francisco with a party of six men to put up wire for the California State Telegraph Company, which had obtained a franchise from the Legislature for a telegraph from San Francisco to Marysville by way of San Jose, Stockton, and Sacramento. On September 25th the wire was in place. On October 24, 1861, the first direct messages between New York and San Francisco passed over the wires of the first transcontinental telegraph line.

One year after Alexander Graham Bell had invented the telephone, in 1876, Frederick Marriott, Sr., publisher of the San Francisco News-Letter, had a wire installed between his office and his home. In February 1878 the American Speaking Telephone Company began regular service with 18 subscribers. Soon afterwards the National Bell Telephone Company offered competition. The early switchboard consisted of two boards affixed to the wall, each with a row of brass clips into which holes were drilled to receive the plugs making the connections. In the National Bell Telephone Company's office, bells above these boards notified the operator of a call. Since the bells sounded exactly alike, however, a string had to be attached to each bell tapper and a cork to each string; the antics of the cork called the attention of the operator to the line that demanded attention.

On January 25, 1915, the first transcontinental telephone line was opened. Dr. Alexander Graham Bell in New York spoke to his former employee, Thomas Watson, in San Francisco, repeating his sentence of an even more memorable occasion: “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you!” In December 1938, San Francisco had 282,204 telephones—more connections per capita of population than any United States city except Washington, D. C.

A still greater stride in communication was made on December 13, 1902, when the shore end of the first transpacific cable was laid in San Francisco by the Commercial Pacific Cable Company (organized in 1883 by Comstock king John W. Mackay).

A more homely problem—a vexatious one for San Francisco since 1849—was that of its water supply. In early years water had been brought from Marin County on rafts and retailed at a dollar a bucket. Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, local sources of supply were exploited by private companies. When these failed to keep pace with the requirements of the rapidly growing metropolis, the City and County of San Francisco began in 1914, after a long and bitter struggle with monopolistic interests, the construction of the Hetch-Hetchy system.

Heart of the system is O'Shaughnessy Dam, towering 430 feet high across the granite-walled course of the Tuolomne River, high in the Sierra Nevada in Yosemite National Park. The mountain waters impounded are piped to San Francisco by gravity through tunnels and steel pipes over 163 miles of mountains and valleys. Besides the main dam and reservoir at Hetch-Hetchy, the system includes a number of subsidiary storage reservoirs and power stations with a combined capacity of more than 150,000 horse power. The dam was completed in 1923, the aqueduct in 1934.

The East Bay, too, had been faced with a similar situation regarding its water. From several wells in the vicinity and the surface run-off of San Pablo and San Leandro Creeks the region long had drawn a water supply whose quality was impaired by the inflow of salt water from the Bay and whose quantity was estimated at about one-sixth of that soon to be required. In the same year the O'Shaughnessy Dam was completed to impound waters for thirsty San Franciscans, the East Bay Municipal Utility District was organized. Eight years later it had completed the 358-foot-high Pardee Dam on the Mokelumne River in the Sierra foothills, a 93.8-mile aqueduct, two subsidiary aqueducts, and auxiliary storage reservoirs.

Long before the waters of the Sierra Nevada were generating power to light the homes of the Bay region—on the evening of July 4, 1876—Reverend Father Joseph M. Neri presented electricity to San Franciscans, operating on the roof of St. Ignatius College three large French arc searchlights with an old generator that had seen service during the siege of Paris in 1871. This was an occasion surpassing even the lighting of the city's first gas lamps on February 11, 1854—illumination provided by gas manufactured from Australian coal by the San Francisco Gas Company (first of its kind on the Pacific Coast).

George H. Roe, a local money broker whose interest in electricity had been aroused when he found himself owner of a dynamo taken as security for a loan, organized in 1879 the California Electric Light Company and erected a generating station on a small lot near the corner of Fourth and Market Streets. Early consumers paid $10 a week for 2,000 candlepower of light—which was turned off promptly at midnight. By 1900 a number of other companies had been organized. Through a merger of two of the largest, in 1905, was incorporated the Pacific Gas and Electric Company, which now operates four steam-electric generating stations in San Francisco and two in Oakland. Now the third largest public utilities system in the United States, P.G. and E. serves an area of 89,000 square miles on the Central Pacific Coast. It controls 49 hydroelectric generating plants and ten steam generating plants, all interconnected, with a total installed capacity of 1,676,902 horsepower. Radiating from hydroelectric generating stations installed on 30 different streams of the Sierra Nevada and supporting steam powerhouses, the electric system forms an interconnected network of transmission and distribution lines from the mountains to the sea, more than 500 miles in length.

Bay Region: Today and Yesterday

THE BAY AND ITS CITIES

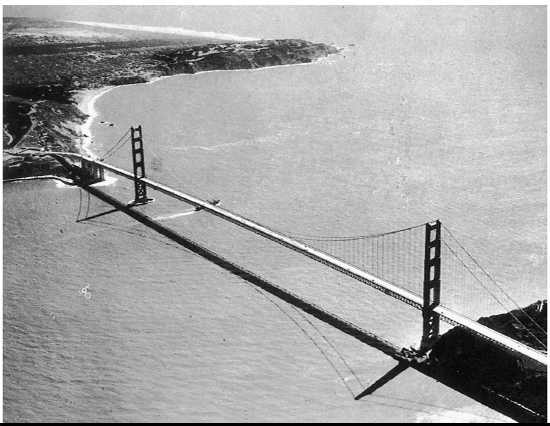

GOLDEN GATE BRIDGED BY WORLD'S TALLEST, LONGEST SPAN

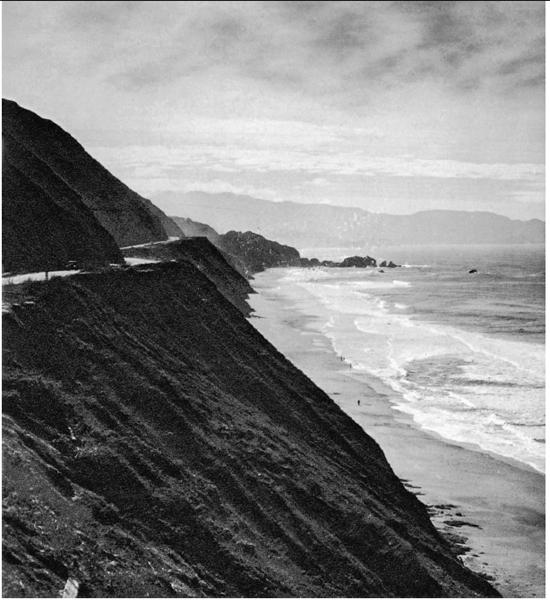

PENINSULA CLIFFS

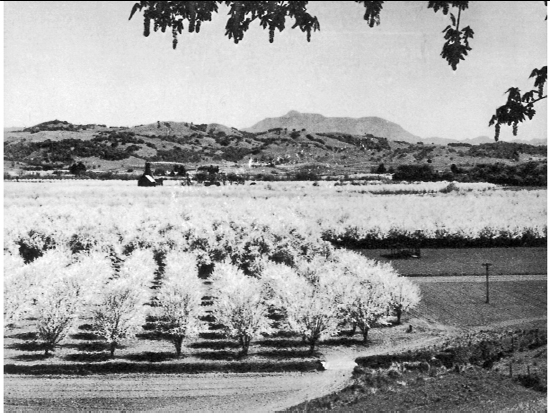

ORCHARDS CARPET THE VALLERYS

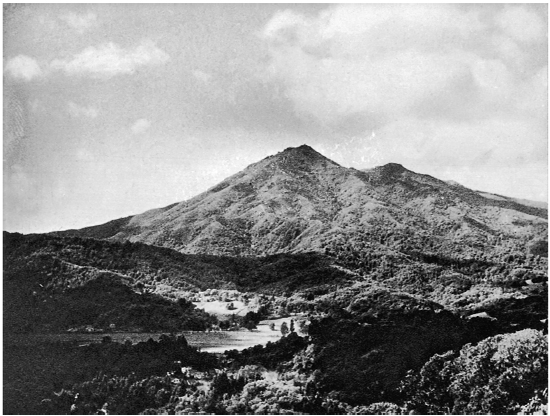

MOUNT TAMALPIS LOOMS OVER MARIN COUNTY

THE PRESIDIO IN 1816

Drawing by Louis Chorts

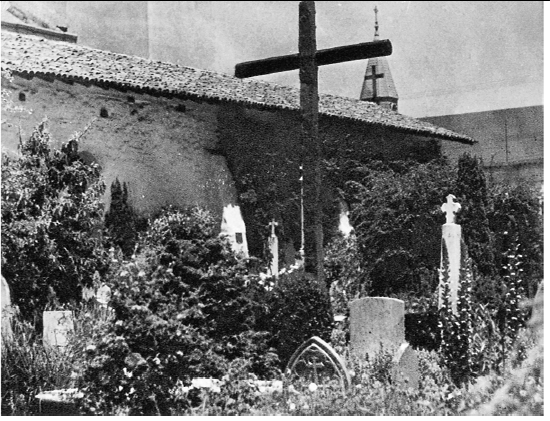

GRAVEYARD, MISSION DOLORES

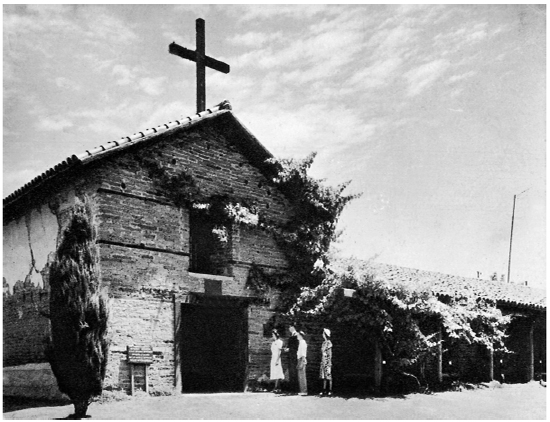

NORTHERNMOST MISSION AT SONOMA (1824)

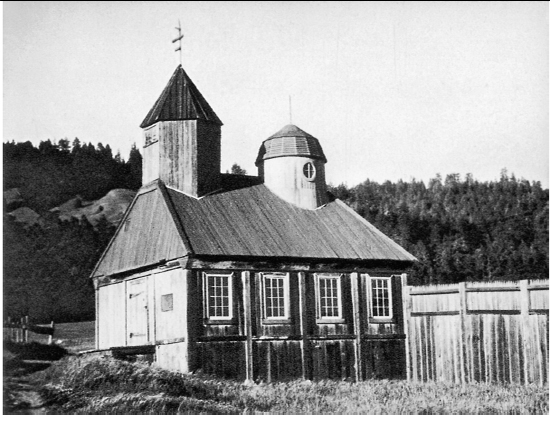

RUSSIAN CHAPEL AT FORT ROSS (1812)

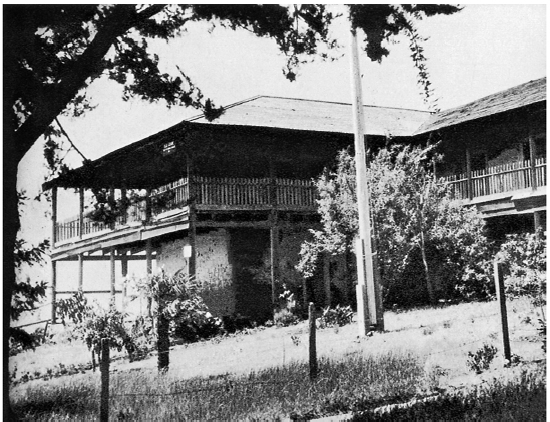

VALLEJO'S CASA GRANDE NEAR PETALUMA

PEDRO FONTS MAP OF SAN FRANCSICO BAY (1777)

In the meantime, San Francisco's hills again had proven to be—and this time literally—stumbling blocks to the city's progress; for, as they halted further expansion, the town became cramped for space. Answer to the new problem was the construction of a series of five railway tunnels known as the Bay Shore Cutoff; completed in 1907, they brought the Peninsula towns within commuting distance of “the city” and opened up a large new residential area. In 1915 the city's North Beach section was made more easily accessible by a tunnel driven through Nob Hill on Stockton Street. Two years later the completion of the 2¼-mile Twin Peaks Tunnel provided a short-cut to the district west of Twin Peaks, doubled the city's potential residential area, and brought a rich financial return to property owners, business men, and real estate promoters. Another tunnel was bored to carry streetcars under Buena Vista Heights.

By the third decade of the twentieth century the fast-growing East Bay communities were confronted, as San Francisco had been, by the need of making similar improvements on nature. In 1928 a $4,496,000 automobile and pedestrian tube was laid beneath the Oakland Estuary to connect Oakland with the island city, Alameda. The Posey Tube (named for its designer and engineer) is unusual in that it is constructed of twelve prefabricated tubular sections, 37 feet in outer diameter, which were “corked,” towed across the Bay, and sunk into a great trench dredged on the bottom of the estuary. The center one of the tube's three horizontal sections accommodates traffic; the lowest is a fresh air duct; the uppermost, an outlet for foul air.

More than 1,000 men toiled three years to build the impressive Broadway Tunnel connecting East Bay cities with Contra Costa County, which cost $4,500,000 before its completion in 1937. This twin-bore automobile and pedestrian tunnel, an extension of Oakland's main thoroughfare, has two additional lateral approaches from Berkeley and East Oakland. A clover-leaf obviates the crossing of traffic lanes. By day, “twilight zones” at each portal accustom the drivers’ eyes to the change from natural to artificial light.

But when engineers had created a city where mud flats had been, had surmounted the hills of that city and the hills and valleys of the region beyond, had learned to talk over miles of wires and harnessed mountain streams to provide drinking water and electricity for a people, they had still to span the great body of water on whose shores the people lived. Not until 1927 was the Bay first bridged when the narrowest width at its extreme southern end was crossed by the Dumbarton Drawbridge, connecting San Mateo and Alameda Counties.

Carquinez Strait, the narrow entrance from San Pablo Bay to Suisun Bay, was next to be spanned. Carquinez Bridge is a tribute to the imagination and determination of two business men—Avon Hanford and Oscar Klatt. In 1923 their company secured a toll bridge franchise and—despite the admonitions of engineer and layman that the water was too deep and swift to permit a bridge at the site—construction was begun. In 1927 the $8,000,000 structure was opened to traffic. The great double pier rests on sandstone and blue clay at a depth of 135 feet below mean water level, over which the steel construction towers, for four-fifths of a mile, 314 feet above the strait.

March 3, 1929, saw completion of what was then the longest highway bridge in the world—the twelve-mile San Mateo Toll Bridge, crossing seven miles of water a few miles north of the Dumbarton Bridge. The movable, 303-foot, 1,100-ton center steel span—erected in South San Francisco and floated by barge to its resting place—can be raised 135 feet above water level.

The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge was opened in November, 1936. It has six lanes for automobile traffic on its upper deck; three lanes for truck and bus traffic and two tracks for electric trains, on its lower. Its length is 12 miles, including approaches. Clearance above water at the central pier is 216 feet, sufficient to clear the mast of the largest ships. The west crossing—between San Francisco and Yerba Buena Island—consisting of two suspension bridges anchored in the center to a concrete pier, is unique in bridge construction; it is so built that the roadway forms a single smooth arc. Connecting the east and west crossings is the largest diameter tunnel in the world, blasted through Yerba Buena Island's 140 acres of rock. It is 76 feet wide and 58 feet high; through it an upright four-story building could be towed. Three pioneer tunnels were bored through the rock and then broken out until they became one horseshoe-shaped excavation. A viaduct was built 20 feet above the floor of the tunnel to carry the six-lane automobile boulevard; beneath it pass electric trains and trucks. The extraordinary depth of the bedrock to which concrete supports for the towers had to be sunk through water and clay presented bridge builders with an exceptional problem. To solve the problem, engineers devised a new system of lowering the domed caissons, controlled by compressed air. In the case of the east tower pier of the east crossing, bedrock lay at such a depth that it could not be reached. The foundations were laid at a depth greater than any ever before attained in bridge building.

Six months after the opening of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay-Bridge, San Francisco was linked to the northern Bay shore by the world's longest single span, the Golden Gate Bridge. It measures 4,200 feet between the two towers and 8,940 feet in all. Its towers rise 746 feet above high tide; its center span, 220 feet above low water. The tops of the towers rise above the waters of the Golden Gate to the height of a 65-story building. Most spectacular feat in the bridge's construction was the building of the south tower's foundation. Because of the swift tidal flow at this point, spanning the Golden Gate had long been considered impossible. Working on barges tossed continually by swells as high as 15 feet, seasick workmen built from bedrock a huge concrete fender completely enclosing the site. Inside this fender, which later became part of the structure, caissons were sunk.

When the two towers were finished, workmen clambering along catwalks strung between them spun the giant cables from tower to tower. Into the spinning of each of the cables (which measure 36½ inches in diameter) went 27,572 strands of wire no thicker than a lead pencil. To support them, each tower has to carry a vertical load of 210,000,000 pounds from each cable and each shore anchorage block to withstand a pull of 63,000,000 pounds. From these cables the bridge was suspended by traveler derricks invented to perform jobs of this kind.

At about the time the two bridges were being woven into the Bay region's design of living, Treasure Island was rising from the rocky shoals just north of Yerba Buena Island. An outline of the island-to-be was drawn in tons of quarried rock. Inside it were dumped 20,000,000 tons of sand and mud dredged from the bottom of the Bay. When the job was completed a 400-acre island, cleaned of salt by a leaching process, had replaced the shoals once feared by seamen. Built to support the $50,000,000 Golden Gate International Exposition, Treasure Island is destined to become, when the Exposition closes, a terminal for the graceful Pacific Clippers that fly to Hawaii, the Philippines and the Orient.