11. Cyclicals And Turnarounds

Most companies benefit from an upturn in the economy and suffer if the economy turns down. However, a really great growth stock will usually manage to produce increased earnings even in the depths of a recession. Some companies with strong business franchises seem to be amazingly unaffected by the gloom and despondency around them. Cyclical stocks suffer much more than most – building and construction companies, steel companies and automobile manufacturers and distributors cannot buck the trend. The most they can hope to achieve is that at the top of the next cycle, they will be ahead of their previous peak, and at the bottom be better placed than last time around.

Hair-raising stuff, but there is plenty of money to be made if you can get your timing right. To do this you have to understand the anatomy of business cycles. Let us take house building for example. At the bottom of the cycle a few survivors in the business will benefit from reduced competition and begin to turn the corner. They would be finding that prime land and labour were far easier to acquire and, therefore, much cheaper than during the boom. Fewer houses would be under construction, so the prices of those being sold would be more favourable to the builder, providing healthier margins and better profits. Other entrepreneurs aware of the growing opportunity would set up as builders or expand their existing building businesses and would compete for both labour and land. Cost pressures begin to increase. Some of the builders borrow to stock-pile land which is becoming more difficult to acquire and therefore more expensive. Very soon, there is over-capacity in the business, so some house builders slash prices to maintain market share. Margins erode due to lower prices and increased costs. The banks, fearing their loans are in jeopardy, foreclose on the more marginal businesses, which become bankrupt. Some of the more entrepreneurial builders decide that there may be better opportunities elsewhere. Competition falls away, pricing pressures ease and profits begin to improve. The cycle starts all over again.

Clearly, the time to buy is before profits rise and the time to sell is when conditions are obviously improving. The important point to grasp is that a cyclical stock should

never

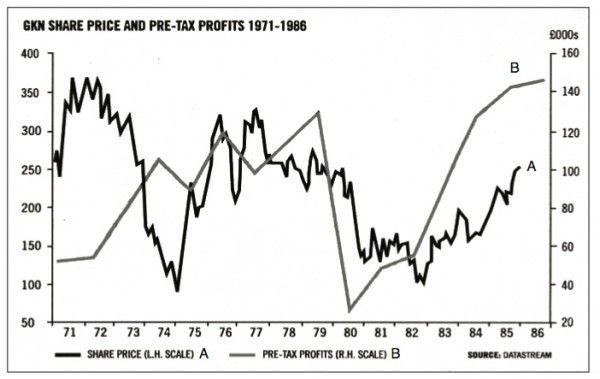

command a very high multiple and a low dividend yield near to the top of the cycle. Let us look at GKN, a typical cyclical stock, to see how its profits and share price were affected by the last two business cycles.

Obviously, you want to time your purchases so that you buy near the bottom of the cycle, but you also want to make sure that your selection is going to survive. Of course, you would enjoy a far bigger gain if you invested in an unlikely candidate for survival which surprised everyone by coming through the recession unharmed. The greater the risk the greater the potential reward. The riskier companies usually have very high borrowings at the bottom of a cycle. When they run out of money, much may depend upon the attitude of their bankers and loan stockholders.

Here are some guidelines that should help you with your selections:

-

- Companies with well-known, national names have a better chance of survival, if only because there seems to be greater reluctance to let them fail. They are an important part of the fabric of our society, so the bankers, loan stockholders and other creditors involved may stretch a few points to be helpful. In some cases, this may be to avoid the undesirable publicity of being accused of pulling the plug, and in others a genuine desire to help the company.

-

- Usually, a company with a well-known name will have already attracted a stockbroker of high calibre and some strong institutional shareholders, who are more likely to help place stock to finance a reconstruction. You must make sure that the company stockbroker is a leading one.

-

- Seek out companies with familiar brand names and other kinds of strong business franchises. Look particularly for those companies which usually have a high return on capital employed.

-

- The calibre of management is obviously crucial. If the old guard remains totally in charge you should be more cautious. A change of management with someone able becoming Chairman or Chief Executive, obviously bodes well for the future and makes your investment a better bet.

-

- Keep an eye open for major competitors going out of business. This is always a very good sign. Your selection should, as a result, be able to secure a larger and more profitable piece of the eventual pie.

-

- Seek out companies with asset backing in excess of market price. These assets should help to generate earnings when the economy recovers. Meanwhile, they may catch the eye of a predator. With the hope of a takeover in mind, you should give preference to companies with a widely based shareholding and no control blocks.

-

- As usual, there is no escape from a little arithmetic. What is the brokers’ consensus forecast in the event of a recovery? What was the P/E ratio at the top of the last cycle? With these two figures in mind, you can easily calculate your potential upside, which for a company with containable borrowings (see 8. below) should be at least 100% and possibly much more.

-

- The magic word ‘borrowings’ brings me to another important point. You should draw the limit at total indebtedness exceeding the net asset value. In other words, gearing should not be more than 100%. In the rare cases when you find that the rest of your criteria are overwhelmingly satisfied, you could stretch the 100% limit, but in that event you should be looking for upside potential in excess of 100%. The extra risk must be balanced by the promise of extra reward.

-

- It is absolutely essential that the forecast for the year ahead shows rising profits or a return to profits. Losses could produce the kind of fatality you are seeking to avoid.

-

- Timing is of the utmost importance. If someone throws a safe out of a window from the penthouse of a skyscraper, you will be severely damaged if you lean out of a window on the third floor and try to catch it. Wait until you are really sure that the cycle has hit bottom. You are looking for the first glimmer of a change – the first hint of good news after the gloom. You will pay a little more this way but look upon the extra cost as an insurance premium.

-

- You want your selection to benefit massively from the upturn. Therefore, you need to ensure, as far as you possibly can, that the company’s main infrastructure has remained intact throughout the recession. The brokers’ consensus profit forecast reflects this in arithmetical terms, but here are a few further specific pointers:

-

a) Ensure that the company has maintained capacity and that major factories have not been sold off.

b) Look for turnover being largely upheld with only margins suffering. This is an excellent indicator as margins can recover quickly.

c) Check if there has been substantial cost cutting. You want your company to be lean and mean in the upturn.

d) Look for companies that are usually good cash generators. If tax losses are allowable for set-off against future profits, short-term debts could be repaid very speedily.

-

- Directors’ share dealings are very important when considering cyclical situations. Seeing a number of Directors buying shares near the low point of the cycle is obviously a very encouraging sign. They might be wrong, but they ought to know.

-

- Buying at the time of a rights issue can be a very attractive way of participating in a recovery. You have the great advantage of being able to study an up-to-date circular to shareholders in which you can see what the Directors are doing with their entitlement, see how much debt remains, and obtain an instant fix on the outlook for future profits.

-

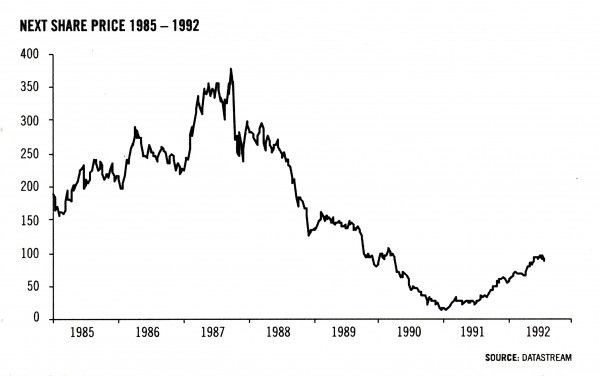

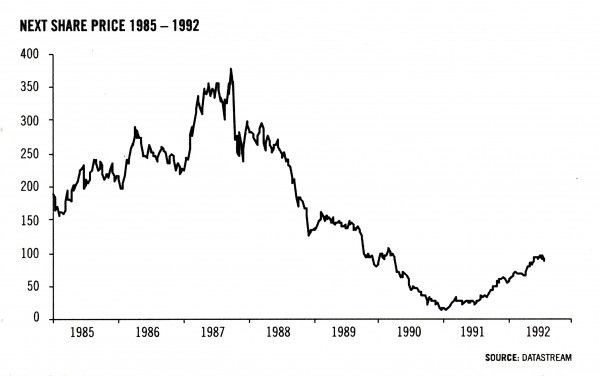

- Above all, you are looking for a company that under normal conditions is a substantial force in its chosen field. One of the best measures of this is sales in relation to market capitalisation. Anything over five times is relatively cheap. Next is a good example. In 1985, sales were £146m and the market capitalisation was £195m. A sales to market capitalisation ratio of 0.75. By December 1990, the market capitalisation had slumped to £24m, although sales were forecast at £800m. The ratio of sales to market capitalisation had become a very attractive 33 times. In the event, the shares subsequently rose from 6.5p in December 1990, to 95p in June 1992.

-

When should you sell a cyclical? With a growth share you might stay to enjoy a long ride, but with a cyclical your target price tends to be more limited. You certainly sell immediately when you see press or broker comment suggesting that the company in question is a growth share. You also sell when the multiple on the forecast profit in the second year of recovery has risen to 75% of the highest multiple the company has ever achieved. In essence, you sell on general recognition that the company has survived the downturn and is now enjoying far better trading conditions. Do not wait until there is an inevitable increase in competition, costs are beginning to rise again and demand is on the brink of flagging. You are trying to operate with a substantial safety margin, so sell well before the top of the cycle.

Although I dislike arithmetical formulae for selling, I would also suggest that for anything other than a very highly geared situation (in which you took a substantial risk with the hope of a disproportionate reward) you should at least consider selling when the shares have doubled.

Now comes the more difficult question of how to cut losses. Remember you were only buying when you thought the cycle was turning up. If this has not happened and the cycle is still going down or you are disappointed in some other major way, you must obviously re-appraise the situation. As with all my other systems of investment, if the story has changed substantially for the worse, sell immediately. Inexplicable falls in price have to be assessed on their merits and become more a question of judgement and feel. I have covered this particular problem more fully in Chapter Seventeen on Portfolio Management.

I rarely invest in cyclicals as the upside seems to me to be limited to a one-off gain. There are, however, large profits to be made if you are expert in both timing and selection.

This is well illustrated by Next, which is worth studying in more detail. Although it was easy to miss investing at the low of 6.5p, there were several further opportunities a little later on in the saga. Along with most of the retail sector, Next over-expanded during the latter part of the eighties, adding to its chain of shops at a phenomenal rate and branching out into credit finance and mail order.

By December 1988, the group warned of a coming ‘significant drop in profits’ and George Davies, previously a star in retailing, was asked to resign. By December 1990, investors were close to despair, with the company moving into heavy losses and with the prospect of two convertibles being near to redemption for £150m. By March 1991, Next had sold Grattan for £167m which, together with a few other minor sales, took the company out of debt. At that date, Next measured up to most of our criteria reasonably well:

-

- Next is a well-known company and would have been a very high profile failure had it been allowed to go under.

-

- Next had a well-known and influential stockbroker.

-

- Next is an excellent brand name.

-

- George Davies had been replaced by David Jones and Lord Wolfson of Sunningdale, both of whom are very able, financially-orientated men, who were determined to restore Next’s balance sheet to health.

-

- Major competitors such as Burton were also under considerable pressure.

-

- After the Grattan deal, debt was no longer a problem.

-

- Losses stopped and improving profit forecasts became the vogue with brokers.

-

- The intention was to restore the core business. Shops were being closed, stock controls improved, and product lines overhauled. Turnover was reduced in the process and margins improved dramatically.

-

- The sales to market capitalisation ratio was still high. Even after the disposal of Grattan, sales were forecast at £450m. At 30p, the ratio was more than four times the market capitalisation of £110m.

-

The most obvious time to buy Next was after the sale of Grattan, when the fear of bankruptcy was removed. You could have bought the shares then for between 25p and 30p for several months, and by June 1992 you would have at least trebled your money.

Turnarounds are not far removed from cyclicals and asset situations. An asset situation that has been neglected for years and allowed to deteriorate to the brink of failure becomes a turnaround. A badly-managed cyclical often becomes a turnaround at the bottom of the cycle. A badly-managed growth company that experiences an unexpected disaster might also become a candidate.

There is no precise definition of a turnaround. I use the expression to describe a company that I hope is going to come back almost from the dead. A company that has been bewitched, battered and bewildered to such an extent that its capacity to survive is in real doubt. The market often exaggerates hopes on the way up and exaggerates fears on the way down. Frequently, a fall in share price can be overdone as institutions and other shareholders rush for the exit.

Most of the criteria for selecting a turnaround are the same as those I have suggested for a cyclical. Many turnarounds at their lows are suffering from a downturn in their own circumstances, sometimes less to do with their basic business than changes in management and direction. Really bad management can bring any company to its knees, and really good management can quickly put things right. You do not want to waste valuable time and risk precious money waiting for new management to arrive on the scene. A major change in management (for the better you hope) is usually an excellent buying signal, although sometimes things have to get worse before they can get better.

For example, let us examine that well-known company English China Clays, which for some inexplicable reason diversified away from a wonderful core business and decided to change its attractive name to the horrible acronym – ECC. A new chief executive, Andrew Teare, who had successfully run Rugby Group for several years, took charge on 1 July 1990. The acquisition of Georgia Kaolin in the US had already been announced in May, and Teare decided to use this purchase to build up the core business and dispose of all the previous diversifications. In September 1991, the company announced its gradual withdrawal from the UK house building sector and a rationalisation programme in the core kaolin operation. Other changes included moving head office, introducing a wide-ranging management incentive scheme, selling ten businesses within eighteen months and cutting the workforce from 13,800 to 10,800. In February 1992, the company had a rights issue to redeem some fancy debt financing in the USA. A month later, the board announced pre-tax profits up more than 50% and proposed that the company’s name should be changed back to the much more popular English China Clays.

In July 1990, the shares were 414p, on a historic P/E of 9.2 and a prospective P/E of about 18. Towards the end of 1990, the shares were very weak at 275p as the company bore the brunt of worries about the recession in construction work. However, by June 1992 the shares reached 555p when the benefits of the reorganisation came through.

Another kind of turnaround can arise from unexpectedly horrific financial results or a disaster like the Union Carbide plant blowing up in Bhopal. I recommend against investing in turnarounds which arise from happenings that are impossible to quantify and may be a bottomless pit. The Bhopal incident has no doubt given rise to claims of unimaginable proportions from relatives of disaster victims. I am not sure about the present state of play, but I suspect that years may go by before the full financial effects will be known.

Similarly, if there is ever a case of a successful claim against a major tobacco company for damage to health of third parties from passive smoking (such as being in the same office as other people who are smoking and dying from cancer as a result) the effects would be immeasurable. With happenings like these, I suggest that you allow plenty of time for the dust to settle before you risk your money. Do not go bottom-fishing – you can drown that way.

As you can see from the examples of Next and English China Clays, there are very large gains to be made by identifying a promising cyclical or turnaround, especially when new management has taken charge. There is of course a risk, so you should never put more than 10% of your portfolio in any one situation of this kind. The safety criteria I have outlined should also help to protect you.

The time to sell a turnaround is delightfully obvious – when the company has turned around and is making good profits. Institutions are no longer ashamed to own the stock and are beginning to invest cautiously: the brokers’ consensus profits forecast is well up on last year and there are perhaps a few comments about the company becoming recognised as a growth stock. Do not be greedy – let the market have your shares. You may well have made at least 100% on your money and possibly much more.

12. Shells

I once compared a very large company with an elephant by making the comment that ‘Elephants don’t gallop’. The main reasons are obvious – to double the size of a very large company capitalised at say £10bn takes years of hard work. A small and obscure company finds doubling much easier, and a shell company, with a market capitalisation of a few million, has an even easier task. I have searched for an analogy for shells to contrast with my elephant ambling along most of the time and just occasionally charging. The best suggestion I can offer so far is a flea, which can jump over two hundred times its own height – equivalent to a man jumping over St. Paul’s Cathedral. Let us have a look at our flea in action and see how shells work and how you can benefit from the process.

A shell is a very small company that usually owns a small and nondescript business of little account and which, above all, has a stock market quotation. The idea of the incoming entrepreneur is simply to obtain a backdoor quotation for his own company, which usually has too short a record or some other shortcoming that precludes obtaining a stock market quotation by a more conventional route. Often, the previous management makes a quick exit shortly afterwards and the original business is sold off as it becomes less relevant to the main activity of the new group. The incoming entrepreneur then has effective board control of the business together with the quotation he was seeking. The shares often rise sharply in price in the hope that there will be plenty of activity. Using the high-flying shares, the company then makes some acquisitions. The share price goes up again in anticipation of more action, and the process is repeated. That is the shell game at its best. The private investor benefits by being in the shell in the first instance, or shortly afterwards, by participating in one of the early placings of stock or by buying in the market.

To find out about companies that are likely to be used as shells or have just started their career as a shell, I recommend to you two newsletters that specialise in shell operations –

The Penny Share Guide

and

Penny Share Focus

. Both are helpful publications and review each month the progress being made by most shells. They also feature potential shells together with a wide range of other very small companies, often called penny stocks. Their comments will keep you abreast of the main developments on the shell scene. Another possible source of information is the

Fleet Street Letter

, which often mentions shells in its Portfolio C section, but concentrates in the main upon medium-sized to larger companies.

Your broker may also know of some interesting shells. Ask for his views – he will be anxious to help you. Newspapers, especially the Sundays and the

Daily Mail

, frequently comment on shells. Michael Walters, who is Deputy City Editor of the

Daily Mail

, has written a comprehensive book,

How To Make A Killing From Penny Shares

, which gives valuable advice and outlines the pitfalls. If you intend to concentrate upon shells, you should read this.

It is important to understand how an acquisitive shell can be such a good investment for early shareholders. Take the example of a property company (when they were all the rage) with one million shares in issue priced on the Unlisted Securities Market (USM) at 50p each, having a market capitalisation of £500,000. The net asset value might be only £250,000, and the 100% premium of £250,000 would be the hope factor – hope that the company will be used as a shell.

The incoming entrepreneur injects his own property business worth say £2m for 4 million shares. The result is a quoted property company with assets of £2.25m and 5 million shares in issue, so by strict arithmetic, if the share price remained at 50p the market capitalisation would by then be £2.5m. However, the accompanying publicity would probably boost the share price to say 100p, capitalising the company at £5m. This is a very small jump for our flea, as there are only one million shares from the original shell that form the market float, and many of these will be in the firm hands of believers and supporters. There might be only 200,000-300,000 shares that are available to the market, and these will usually be sold quickly at higher levels to new converts. The key to a successful shell operation is for there to be more demand for the shares than can be satisfied by the relatively limited supply. That is why very small companies make the best shells.

At this point, our shell makes a substantial acquisition with net assets of say £2.5m. The purchase consideration is satisfied by £1m in a deferred loan secured on the property, and the rest is funded by an issue of 1.5 million ordinary shares which are placed by the company’s brokers with friends, business associates and institutions. The extra 1.5 million shares that are being issued will add to the float, but this problem will be restricted as in the early stages many of the places will be friends and business associates who will hold the shares as a long-term investment.

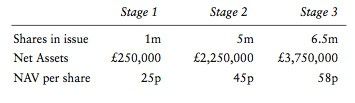

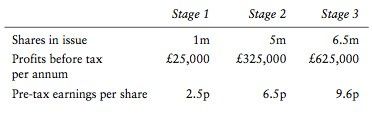

The effect of all this is to increase net assets per share. There have been three distinct stages:

In the column for Stage 3 I have increased the net assets by £1.5m, which is the £2.5m of assets acquired less the £1m deferred loan. The sense of progress from the net asset growth from 25p to 58p per share will usually be accompanied by the feeling that the new £2.5m acquisition is very astute and that the property in question is really worth very much more, especially if planning permission can be obtained for an exciting new development.

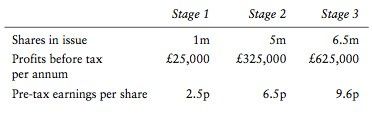

I have given first the example of a property shell because the arithmetic with net assets is easier to follow than with earnings. In fact, earnings situations lend themselves to shell operations much more readily, as future earnings estimates are essentially hopes that may or may not be realised. Taking a similar example with an industrial company, shares would be issued on a high P/E ratio for profits valued on a lower multiple. Let us assume that the same initial shell company had £250,000 worth of assets which could be converted into cash yielding £25,000 per annum. The incoming entrepreneur reverses in his business for the same 4 million shares, but instead of his business having assets of £2m, there are profits of £300,000 per annum before tax. In anticipation of deals to come and hopes for the future of the underlying business, the shares again double to a pound. Then another business is purchased for the same £2.5m, but in this case the profits before tax are £400,000 per annum. Again the vendor agrees to £1m of deferred consideration, and the balance is satisfied by the issue of 1.5 million new shares of £1 each. Our three stages look like this:

Tax has been ignored, as rates vary for companies at lower levels and I do not want to complicate the issue. I have deducted £100,000 per annum from profits to allow for interest on the deferred consideration. The £625,000 pre-tax profits per annum figure is the sum of £25,000 plus £300,000 plus £400,000 less £100,000. You will readily appreciate that as a result of the takeover of the shell and the first acquisition, the earnings per share on a pre-tax basis rose dramatically from 2.5p to 6.5p and finally to 9.6p. Shareholders’ pre-tax earnings per share almost quadrupled. In addition, as more acquisitions in the same industry are made, there will be scope for rationalisation and, in some cases, for radical improvement by re-organisation. Plenty of new hope – the raw material of a high multiple.

You should be aware that, with a highly acquisitive company, there is also the likelihood of profit enhancement by creative accounting. For example, by writing down the cost of acquisitions, capital can be transmuted into future revenue profit. Another simple ploy would be for the shell company to pay a little more for the business it is acquiring and arrange for the deferred loan to be interest-free. This would add £100,000 per annum to pre-tax profits. Very acquisitive companies frequently do this kind of thing, so bear in mind that often their profits are not all they seem to be at first sight. Not many people read the small print. Investing in shells is more of an art than a science. To decide whether a company is a shell or simply a very small business with a quotation is very much a matter of opinion. The key point is that whoever is reversing their business into the company invariably takes board control, and their underlying motive is to obtain a backdoor quotation. In some cases the original business may be retained and developed. To find a worthwhile asset inside a shell is a bonus for the incoming entrepreneur, rarely his reason for doing the deal.

One of the Oxford dictionary definitions of the word shell is:

‘Unimportant firm made the subject of a takeover bid because of its status on the Stock Exchange’.

Another more pertinent meaning is

‘outward show, mere semblance’

.

To give you a better idea of both the attractions and the dangers of shells in the last twenty years, let us look at four well-known examples and see how they have fared in the market.

You can invest in shell companies at four distinct stages of their development, when:

-

- They are waiting for a deal but there is nothing in sight.

- A deal is rumoured and speculation is beginning.

- A deal is announced and the company returns to the market.

- The new managers have been operating for a few months or even longer and are beginning to show their paces.

The first two stages are too nebulous and dangerous for most investors. You are quite likely to invest inadvertently in a genuine company in distress which will soon become insolvent. Alternatively, you might have a very long wait for new management to arrive and take control. Therefore, I recommend that you concentrate upon the last two methods so that, when you invest, you will know for certain that the company is being used as a shell. You will know the name and background of the incoming entrepreneur and have a firm idea of his objectives and the fundamentals of the company. A number of uncertainties will have been removed.

After the successful reversal of the new business into a shell company, the shares are invariably suspended for about six weeks. During this time a prospectus is prepared setting out details of the deal, which also often includes a placing of more shares for cash. When the shell returns to the market, the fundamentals tend to be ignored and the opening market price is usually related to the pre-suspension price. For example, if a company’s shares have an underlying value of 5p and are suspended at 8p, you might well hear that the shares “have a 10p look about them”. With a shell, fundamentals like assets and earnings per share are frequently of lesser importance. Much more attention is rightly focused upon the new man at the helm, his track record, his backers and what he is likely to achieve by acquisition, rationalisation and the occasional spectacular deal.

Another way for an entrepreneur to move into a shell is simply by invitation. A substantial shareholder with effective board control might invite a well-known personality to become chief executive. Shortly afterwards, there would be a rights issue and placing to give the new man a chance to acquire a significant shareholding. He would also be rewarded and incentivised with share options.

To give you the full flavour of the different methods of acquiring control of a shell, let me show you details of three recent shell operations:

1. Clarke Foods

An American businessman, Henry Clarke, together with his family, acquired effective control of Yelverton Investments – a small investment company which he turned into a cash shell. In 1991, he acquired the ice cream businesses of Hillsdown Holdings and Lyons Maid from Allied Lyons. Although trading profits are still awaited, overnight the company became a leading UK manufacturer and distributor of quality ice cream. Before the venture into ice cream was announced, the shares were 39p; by June 1992, they had risen to about 150p.

2. Maddox Group

In February 1992, Hugo Biermann and Julian Askin alighted upon Pathfinders and injected two telephone cable businesses for cash and shares, acquiring in the process a 26% stake in the company, which was re-named Maddox Group. The two men had previously turned Thomson T-line from a £900,000 company into a group they sold to Ladbroke for over £180m. Shares in Pathfinders/Maddox rose after the announcement to 12.5p, though they have slipped back to 8p in June 1992 as the market waits for another deal.

3. Wharfedale

In December 1991, Wharfedale announced that a new management team was moving in headed by Sir Gordon Brunton, who had sixteen years as Chief Executive of the International Thomson Organisation, during which time annual operating profits increased from next to nothing to over $500m. Other members of the team were Pieter Totte and Gordon Owen, who was Group Managing Director of Cable & Wireless.

At the same time, the company indicated that there would be a £2.25m placing of shares at 12.5p to repay some of Wharfedale’s excessive debt. At the annual meeting in March 1992, the management outlined their plans for reorganising the business and gave details of their progress on cost-cutting and rationalisation. The market price has been as high as 24p but by June 1992 had dropped back to 16p to await further developments.

As you can see, all three of these companies are priced on expectations of things to come. In contrast, a new issue of a straightforward business might be valued strictly on fundamentals like the growth rate, current earnings per share, the forecast, the P/E ratio, asset backing, dividend yield and liquidity. You will readily appreciate that giving you guidelines for judging the value of a shell and selecting a suitable one to add to your portfolio is almost impossible. I say almost because I am going to try:

1. First, second and third is the provenance of the incoming management. Look for quality. Look for a heavyweight board joining a lightweight company. Look for previous positive achievement upon which to build your future hopes. Full details of the incoming management should be contained in the prospectus, and there will usually be plenty of press and newsletter comment about any well-known personality.

Your new chief executive may not have run a company of his own before – he could have been working for another well-known group for many years. An excellent stable is one of the best auguries.

Before Greg Hutchings joined F.H. Tomkins he worked as head of UK corporate development at Hanson Trust. When he first became Chief Executive of Tomkins the shares were 12p with a capitalisation of £6m. In June 1992, the shares stand at just under 500p with a market capitalisation for the company of £1.4bn. After making allowance for rights and scrip issues, Tomkins’ shareholders have enjoyed an enormous capital gain so far, and Greg is still going strong.

Bernard Taylor was chief executive of Glaxo before he joined Medeva. The shares were 80p at the time and in June 1992 less than three years later stood at 220p, a gain of 175%. Hanson and Glaxo are obviously top class stables, but there are other similar shell situations in which you can tell that the odds are very much in your favour.

I have dwelt at length upon the desirability of top quality management for a shell because that criterion is far more important than all of the others. If the incoming entrepreneur is absolutely first class, the rest of the criteria should be given much less weight.

2. As an important adjunct to my first criterion, I like to make sure that the new management is buying a substantial stake in the company. This is almost always the case, but keep a close eye on Directors’ buying and selling and regard substantial selling as a clear signal to do the same, almost irrespective of any accompanying explanations.

3. As the future progress of the shell will depend to a large extent upon share placings, the calibre of the company’s stockbroker, merchant banker and investing institutions is a material consideration. A first class incoming executive team will usually attract substantial support.

4. The record of the business being reversed into the shell has to be one of increasing profits and earnings per share, unless of course it is a property company, when different considerations apply. If the new Chief Executive is relatively unknown, the record of the business he has been managing is often the only way for you to judge past achievements.

5. Make sure that, following the merger, the shell has resultant earnings per share sufficient to provide a reasonable starting base for the company. You cannot use the PEG factor to measure the price you are paying. You have to take a broader view with shells, but at your entry price try to avoid paying too much for hope.

It is the absolute amount of the premium over real value that should worry you, not the percentage. This is of course another argument in favour of small shells. For example, if a shell company has profits after tax of £200,000 and the multiple for that type of business would normally be 15, the company would be capitalised at £3m. However, with the hope factor for a really good new Chief Executive, the multiple might be as high as 25, capitalising the company at £5m. The extra £2m is a premium of 66.7%, but really you should not focus on the percentage but on the £2m which is the ‘hot air gap’ that has to be replaced with value. With a high P/E ratio and good backing it would not be too difficult. Now let us contrast this with a company capitalised at £50m with true worth of only £30m. Closing a hot air gap of £20m, with the same percentage premium, would be a far more onerous task for the incoming management, especially as they would also have to worry about a much larger market float of shares.

6. From the above comparison, you will readily appreciate that a little shell, capitalised at £1m and with an underlying business worth £500,000, might be a gem. A 100% premium, but a hot air gap of only £500,000. I very much prefer small companies. I like a shell with a starting market capitalisation of under £10m. The smaller the better – remember our flea.

It is very instructive to note the history of WassaIl. Christopher Miller and Philip Turner, who had been key executives of Hanson, joined the board of Wassall plc together with a business associate David Roper from Dillon Read. There was an immediate rights issue, and institutions came in heavily, together with Hanson, which bought 20%, and the three executives, who each purchased a £1m stake. The market capitalisation at the rights issue price of 125p was over £18m.

Most of the ingredients for a successful shell were in place: above all, three very able entrepreneurs with superb track records and wonderful backing. The shares soared and several acquisitions were made, most of which were very successfully reorganised and rationalised afterwards. The share price of 180p (after a one for two scrip issue) in June 1992 is now well backed by earnings and compares with 125p for the rights in September 1988. A gain of 116% in just under four years – very good for a conventional industrial company but modest for a successful shell. The management, which is excellent (and will, I am sure, do very well in the future), did not put a foot wrong except for their very first one – starting with much too large a vehicle, at too heavy a price for a shell. Take my advice and avoid big shells. Stick to fleas – elephants don’t gallop.

7. I much prefer low-priced shares. Companies often lose their shell-like quality as their share prices rise over £1. We all know that the price of a share makes no difference really and that owning four shares with a nominal value of 25p is the same as owning one share at £1. Nevertheless, when a share becomes ‘heavier’ and the price rises over £1, the press and brokers are more likely to have a serious look at the company and analyse the fundamentals. Shells thrive on future hope and a hint of mystery. Shells are about travelling, not arriving, so from the investment point of view arrival should be postponed as long as possible. My favourite price for a shell is between 5p and 10p. My second choice would be under 15p, then 20p and then 25p. The smaller and more like a flea the better.

A problem with shells priced at very low levels is the spread in the market, and that is one reason for not going below 5p. A 3p share, for example, would, probably, be priced at 2.75p-3.25p, giving the market makers a colossal turn of 0.5p – equivalent to 16.7%. In spite of this drawback, I prefer low-priced shares for a shell. An 8p share could easily rise to 10p in a few hours and 12p by the following day – that would be an increase of 50%. Very few shares of 80p could rise to 120p in the same 48 hours and certainly an £8 share would find it very hard going to reach £12 in six months, never mind a couple of days. For a shell, any price from 5p to 50p is highly attractive, as the first major psychological barrier of £1 is still some distance away. The moment of truth can sometimes be postponed, even with the shares trading at much higher levels of £2 to £3, but as the share price becomes heavier, so the share begins to lose one of the essential characteristics of a shell. At £3, they are in grave danger of someone deciding that they are a serious company and should be valued accordingly.

8. Avoid any shell unless it has a full listing or is on the USM. Bulletin Board quotations and shares that trade by matched bargains are not good enough for your purposes. Institutions avoid them like the plague and it is almost impossible to deal either way if you are in a hurry.

9. My last criterion is the liquidity of the company. Shells are obviously a much riskier kind of investment than leading companies. They find it more difficult to borrow in recessionary times – they are more likely to run out of money. Make sure that yours at least start off with a net cash balance or containable borrowings.

The high risk of investment in shells can be reduced by good portfolio management. Do not be fooled by remarks like ‘5p is only option money’ and ‘all you can lose is 5p.’ If you have invested 5p and you lose 5p, you have lost all your money on that investment. It can happen very easily and must be expected more frequently with shells than with more established companies.

The first rule of shell portfolio management is to spread your investments over at least ten shares, preferably in equal amounts. A few more if you like, but never less than ten.

The second rule is to cut losses when shares drop by 40% from your cost. This may seem to be a very high limit but the market maker’s turn can account for 10%-15% and shells are very narrow market, volatile stocks. You do not want to be taken out of your carefully selected investments by a minor and temporary blip. When your 40% limit is reached, simply cut your loss. The new managing director might have dropped dead or moved on to another company, or there could be some other major adverse development. Needless to say, when you know for certain that the story has changed for the worse, you should always sell immediately.

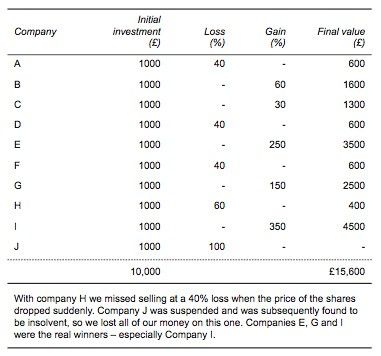

The third and most difficult rule is to run profits. Before we decide how far to run them, let us look at the arithmetic of the performance of a notional shell portfolio containing ten shares over a period of one year:

With ten well-selected shares I would normally expect three big winners, four moderate winners and three losers. To be conservative, I assumed that we had five losers, one of which cost us more than might have been expected. On the plus side, I assumed that we had five winners, three of which had an average gain of 250%. We only enjoyed these large gains because we ran the profits. Most of the losses were contained because we cut them before they became more serious.

Our average gain over the year was 56% – a very worthwhile performance. Even if we had lost everything on the five losing shares, the average gain would still have been a satisfactory 34%. The credit for these above average gains must be attributed to the policy of running profits. There is no other explanation. Imagine the horrific performance if we had followed the much more natural policy of clinging to losses in the hope that the shares would recover, and snatching profits, nervously and prematurely, because we were frightened that they would disappear. We would almost certainly have lost money.

There is no easy guide for when to take a profit. Frequently, I add to my profit-makers when they have done well for me and are on all time highs, but you might find this very difficult psychologically. My simple suggestion to you is to allow your profits to run for a year, unless of course the story changes. The most important consideration is to let your little flea jump as high as it can. Give your flea a year to show how well it can perform. You will be very happily surprised sometimes.

After the year is up, check the fundamentals and assess each share for what it is really worth. What are the press, brokers and investment newsletters saying about the shares? Would you buy the shares now? What are the prospective earnings, the P/E ratio and the asset backing? Is there a large float of shares, and have any of the directors been selling? These are the kind of questions to ask yourself. If it has been a successful investment, the company is almost certainly no longer a shell, and should be reviewed like any other investment, strictly on its merits, in comparison with other shares in the same sector of the market.

Bear in mind that there is an extra advantage of running profits and cutting losses – you will keep your tax bill at a minimum. In a way, the Government is giving you an interest-free loan of the tax that will be due when your profits are realised. With shell investment, in particular, this can be a factor to take into account, but tax considerations should never over-ride a strong feeling that shares should be sold.

When in doubt, you can always sell half your holding in a big profitmaker. I do not like being half right and half wrong, but some people find this makes it easier to have the courage to run the residual profit. What are they so worried about anyway? Whether or not to take a very large profit is a great luxury to be enjoyed, so never agonise too much over the decision. Investing in fleas should be fun.

13. Asset Situations And Value Investing

Investors who concentrate upon asset situations are not so interested in immediate earnings. They reason that if a company holds the right kind of assets, earnings will flow from them eventually. If the existing management fails to deliver, new management or a predator will arrive on the scene to put the assets to work.

Determining the real asset value of a company is not an easy task, especially nowadays. At one time, you could rely upon substantial assets like major properties being understated in the balance sheet. In a very recessionary climate the reverse is often the case. In June 1992, Speyhawk has just announced a write-down of its assets of a massive £205m. The shares were 140p at their 1991 peak and were 2.5p after the news. Before the collapse, the shares were already trading at an 87% discount to their last published net asset value. Investors were obviously aware that the previous set of accounts were not to be relied upon.

How could this kind of over-valuation have occurred? There are a number of ways. Individual properties might have been valued based on the rents being received by other landlords of comparable buildings. However, in some cases there might have been substantial inducements to incoming tenants, such as a couple of years rent-free occupation and payment of the tenants’ costs for fitting out offices. Meanwhile, the disadvantages of high gearing were becoming more apparent as property values tumbled during the year.

Another asset that is difficult to value is plant and machinery. On a going concern basis the valuation might be substantial, but if a factory is closed down and machinery has to be sold, the proceeds can be derisory, especially in a difficult trading climate. Even Warren Buffett had a few problems on this score, when he decided to close the New Bedford textiles plant that was one of his earliest acquisitions. The management was hoping for a good figure for the sale of the machinery, which had a book value of $866,000. They were due for a surprise – at a public auction the proceeds were only $163,000.

Brand names are difficult if not impossible to value. In some balance sheets they are included almost for nothing but in others they are valued at hundreds of millions of pounds. Most companies do not value brands in their balance sheets. The few that do usually have a specific reason – RHM, for example, was prompted by the threat of being taken over.

The recommended treatment of goodwill and intangibles on acquisition is that they be written off against reserves in the first year. However, accounting guidelines are due on this difficult subject shortly, and meanwhile, from the investor’s viewpoint, the key is to be certain that the brand names you are examining are very strong in their own right and will continue to provide an independent earnings stream for the company in the future.

Goodwill is another thorny issue. I recommend writing it off when you calculate the net asset value of a company in which you are interested. At the very least your valuations will be consistent and understated.

There is a new accounting proposal, which attempts to make the balance sheet show current or market values rather than the present mix of historic and ad hoc re-valuations. At the moment, the rule for fixed assets, such as properties, is that they should not be included at values in excess of market price. However, we have already seen that valuers interpret marketprice in many different ways.

When investing in an asset situation, look for net assets to be at least 50% more than the present share price. Do your best to double-check that the net assets are accurately stated, but remember this is not an easy task.

There are also a number of further protective criteria, which have to be satisfied:

-

- Total debt must not be more than 50% of net asset value.

- There must be moderate earnings. Do not buy into substantial loss makers, however strong the asset position.

- The basic business of the company must be reasonably attractive and there must be obvious scope for recovery. Avoid shipbuilders for example.

A great additional inducement is to see executive directors buying some shares. Not a mandatory criterion, but an excellent pointer.

Companies of particular attraction to predators are those that have several disparate parts. The ideal is one with a substantial loss-maker that almost cancels out the other profit making activities of the group. A predator would not take long to find a buyer for the loss-maker, even if he had to almost give away the offending subsidiary. The resultant swing in profitability is often spectacular.

I am not over-keen on asset situations and prefer to concentrate upon growth stocks, shells and turnarounds. At Slater Walker, I could usually arrange for an asset situation to be activated. Nowadays, like other investors, I have a long and boring wait, whereas growth stocks and turnarounds usually give much more immediate satisfaction.

Ben Graham, who wrote

The Intelligent Investor

, is the American archdeacon of ‘Value Investing’, which is not to be confused with investing in asset situations. Graham’s most famous investment formula is to buy shares at a price that represented not more than two-thirds of a company’s net current assets

deducting all prior charges and giving no credit for any of the fixed assets of the company

such as property, plant and machinery, brand names and goodwill. In other words, buying the assets that are convertible into cash at a discount, with the rest of the business thrown in for nothing! Graham recommended selling when the share price advanced to a price equal to the net current assets less all prior charges. When the formula worked the gain would therefore be 50%. Between 1946 and 1976 Graham found that this method produced a compound annual rate of return in excess of 19%.

Many people believe that the term ‘Value Investing’ only refers to buying assets at a discount. In fact, value investing is broader than that – the essential concept is to look for values with a significant margin of safety relative to share prices.

Graham worked on several different approaches to investment, but buying value in one form or another was always his underlying principle. Before we examine his other ideas, it is important for you to realise that following the other systems I have outlined is also a form of value investing.

When you buy shares in a dynamic growth company on a low P/E ratio, with a consequently low PEG factor, you are buying growth prospects at a discount. You are obtaining better value for money than by buying the market as a whole. Similarly, when you invest in a turnaround just as the action starts or in a cyclical before the cycle turns up, you are buying into a company at a substantial discount to its full potential.

The market price of a share and the underlying value of that share are two very distinct animals. The value is always subjective – what are the assets worth, always open to many different interpretations – what are the future earnings going to be, again very much a matter of opinion. That is why Graham concentrated his first system around net current assets, which could be converted into cash, the one asset that has an indisputable value. Graham believed that the market price would fluctuate without rhyme or reason around the real value, often for a considerable period of time, but in the end value would win through. In the long run share prices move in sympathy with earnings per share, dividends, cash flow and net assets. This is the essential back-cloth for understanding Graham’s other approaches to investment.

Graham’s second most well-known system was to buy shares which had an earnings yield (the reciprocal of the P/E ratio – for example a share on a P/E of 8 has an earnings yield of 12.5%) of not less than double the yield on a triple A bond. If the yield on such a bond was 10% that would mean buying shares on a multiple of only 5. In addition, Graham used an extra protective caveat insisting that the total debt of the company should not exceed its tangible net worth. Analysing the previous thirty years, Graham concluded that this method would also have produced a compound annual rate of return of 19% – far more than the market as a whole over the same period.

Graham’s third approach was to buy shares with a dividend yield of not less than two-thirds of the triple A bond yield. Again he insisted that the companies in question should not owe more than they were worth. The compound annual rate of return was almost the same at 18.5%.

An important feature of Graham’s method was that every qualifying stock had to be bought. Personal likes and dislikes were not allowed. In all three cases, Graham sold stocks either if they had risen 50% or a two year period had elapsed, whichever came first. He also sold if dividends were passed and, with earnings-based shares, if earnings declined to such an extent that the current market price was 50% higher than the hypothetical purchase price.

Graham was a most systematic and ingenious fellow who liked to buy assets at a discount and shares with a low P/E ratio. He then put a protective net under his selections with the safety criterion of limiting debt to tangible net worth. In my system for buying dynamic growth shares I am prepared to buy on a higher P/E ratio than Graham, but I link this with the estimated growth rate and find my value from a low PEG factor. I then erect a far more comprehensive safety net with my other criteria.

Warren Buffett was a disciple of Ben Graham, but modified his approach. It is important to understand that Graham gives no credit in his figures for intangibles like goodwill and brand names. In contrast, Buffett looks for shares that offer good general value and have a strong business franchise, preferably backed by very strong brand names. Essentially, Buffett is seeking a growth share to have and to hold. Graham was looking for immediate and obvious value to be sold as soon as the shares had risen by 50%. Buffett prefers to wait for a decade or so for a gain of a few thousand per cent.

The difficulty of operating Ben Graham’s most famous system (the market price of a share being no more than two-thirds of net current assets, after deducting all prior charges and bringing in nothing for other assets) is that for long stretches of time very few, if any, shares measure up to that incredibly high standard. If Graham was alive today, he might argue that you should simply withdraw from the market for a few years until conditions arise which offer you the value for money that you are seeking. Graham may be right, but my problem is that I would get so bored waiting.

14. Leading Shares

Major companies are no different from smaller companies. You will not find any shells amongst them, but you will find plenty of growth stocks, cyclicals, turnarounds and asset situations. One advantage of dealing in leading stocks is that there is undoubtedly a greater degree of safety. Large stocks are more established, more a part of the fabric of society, and therefore less likely to fail from lack of funds or unexpected disasters. Furthermore, the market in the shares of larger companies is far more liquid. With a small company, you will quite often find that the market has suddenly contracted to only 1000 shares with a very wide spread. With leading shares, you should always be able to deal when you come to take your profits or cut your losses.

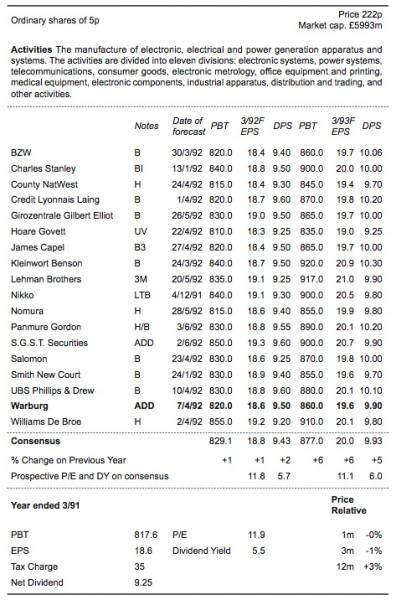

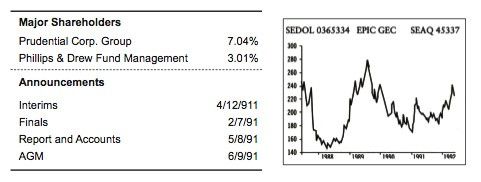

A disadvantage of leading shares is that they are usually more expensive as they have invariably been heavily researched. Overleaf, you will see two extracts from the June 1992

Estimate Directory

– one for MTL Instruments and the other for GEC. Eighteen brokers have researched and written about GEC against only two who have bothered with MTL. The extensive coverage of GEC should give you a more reliable consensus forecast, but the over-exposure, coupled with the attractions of better marketability, tends to result in higher PEGs for blue chips.

A further disadvantage of leading shares is, of course, that elephants don’t gallop, although they do charge occasionally. If you intend to invest in them, you should be looking for one that is about to break away from the herd. You might well ask how you can tell. The answer is simple – apply exactly the same principles to investing in leading companies as you would to small companies. In PEG terms you will have to stretch your limit a little as you will find very few with a PEG of under 0.66, or for that matter 0.75. To keep the formula simple, I suggest a limit of one – the prospective multiple should not be more than the estimated growth rate.

The MTL Instruments Group PLC

The General Electric Company PLC

As you know, I prefer growth shares with market capitalisations of under £100m. Most of the shares in the FT-A 500 Share Index are well over this figure. For the purposes of illustrating my approach to leading shares, I am, however, going to concentrate for the moment upon the FT-SE 100 Index in June 1992. The formidable list shown overleaf needs to be broken down and analysed in detail. Let us first of all identify the super-growth shares – not from their reputation, but from their actual performance in recent years. A Datastream analysis can easily do this for us by applying a few selective criteria:

-

- 15% compound growth in EPS over the last five years.

- At least four years of positive growth.

- EPS up at least 15% last year.

- Dividends paid in each year and not cut at any time during the last five years.

Out of the 100 shares in the Index, there were only seven survivors – Rentokil, Rothmans, Sainsbury, Tate & Lyle, Tesco, Inchcape and Wellcome.

A few well-known growth shares are missing because the 15% EPS growth target is too harsh for the last recessionary year. If we drop the limit to 12% growth for that year only, one more share, Glaxo, scrapes through. If the limit for compound growth over the last five years is reduced to 12% per annum then four more shares make the grade – Argyll Group, Associated British Foods, British Telecom and Scottish & Newcastle. Reuters, with compound growth of 23%, and Guinness with 19.5%, were unlucky to just fail at the last post, with 1991 EPS growth of 9% and 11% respectively. We will admit them, together with Vodafone and SmithKline Beecham, which had strong growth but short records.

Many well-known names failed to measure up to our criteria. For example, Marks and Spencer and Tomkins, because last year earnings were up only fractionally, and Hanson, as last year’s earnings were down a little.

FT-SE 100 Index on 18th June 1992

|

Company

|

Latest Year End

|

Growth in EPS1987

|

Growth in EPS1988

|

Growth in EPS1989

|

Growth in EPS1990

|

Growth in EPS1991

|

Growth in EPS1992

|

|

ABBEY NATIONAL

|

12/91

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+16.7%

|

+9.3%

|

-

|

|

ALLIED-LYONS

|

2/92

|

+34

|

+17

|

+14

|

+4

|

+8

|

-

|

|

ANGLICAN WATER

|

3/91

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+7

|

-

|

|

ARGYLL GROUP

|

3/92

|

+7

|

-1

|

+17

|

+25

|

+27

|

-

|

|

ARJO WIGGINS APL

|

12/91

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-25

|

-

|

|

ASSD.BRIT.FOODS

|

9/91

|

+20

|

+2

|

+14

|

+21

|

+13

|

-

|

|

BAA

|

3/92

|

-

|

-

|

+30

|

+36

|

+21

|

-

|

|

BANK OF SCOTLAND

|

2/92

|

+21

|

+15

|

+29

|

+13

|

-44

|

-23

|

|

BARCLAYS

|

12/91

|

-71

|

+296

|

-54

|

-13

|

-39

|

-

|

|

BASS

|

9/91

|

+22

|

+12

|

+22

|

+9

|

-1

|

-

|

|

BAT INDS.

|

12/91

|

+1

|

+20

|

+21

|

-64

|

+34

|

-

|

|

BET

|

3/92

|

+19

|

+13

|

+16

|

+11

|

-35

|

-

|

|

BLUE CIRCLE IND.

|

12/91

|

+22

|

+19

|

+5

|

-23

|

-36

|

-

|

|

BOC GROUP

|

9/91

|

+39

|

+22

|

+11

|

+4

|

-15

|

-

|

|

BOOTS

|

3/92

|

+9

|

+7

|

+18

|

+20

|

-3

|

-

|

|

BOWATER

|

12/91

|

+34

|

+26

|

+26

|

-8

|

-2

|

-

|

|

BRIT. AEROSPACE

|

12/91

|

-100

|

-

|

-9

|

+63

|

-56

|

-

|

|

BRIT. PETROLEUM

|

12/91

|

+139

|

-20

|

+60

|

-1

|

-76

|

-

|

|

BRITISH AIRWAYS

|

3/91

|

|

+7

|

+22

|

+42

|

-43

|

-

|

|

BRITISH GAS

|

12/91

|

-

|

-3

|

+8

|

-4

|

+34

|

-

|

|

BRITISH STEEL

|

3/92

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+1

|

-47

|

-

|

|

BRITISH TELECOM

|

3/92

|

+25

|

+10

|

+10

|

+10

|

+13

|

-

|

|

BTR

|

12/91

|

+11

|

+23

|

+27

|

-11

|

-10

|

-

|

|

CABLE & WIRELESS

|

3/92

|

+9

|

-5

|

+35

|

+20

|

-3

|

-

|

|

CADBURY SCHWEPPES

|

12/91

|

+30

|

+23

|

+8

|

+2

|

+7

|

-

|

|

CARLTON COMMS.

|

9/91

|

+35

|

+49

|

+34

|

-16

|

-33

|

-

|

|

COATS VIYELLA

|

12/91

|

+26

|

-41

|

-7

|

-20

|

-6

|

-

|

|

COMMERCIAL UNION

|

12/91

|

+7

|

+3

|

+9

|

-91

|

-100

|

-

|

|

COURTALDS

|

3/92

|

+28

|

+6

|

-12

|

+16

|

+6

|

-

|

|

ENG. CHINA CLAYS

|

12/91

|

+22

|

+27

|

+5

|

-46

|

+24

|

-

|

|

ENTERPRISE OIL

|

12/91

|

+74

|

+5

|

+61

|

+14

|

-19

|

-

|

|

FISONS

|

12/91

|

+14

|

+21

|

+22

|

+18

|

-21

|

-

|

|

FORTE

|

1/92

|

+22

|

+16

|

-

|

-

|

+3

|

-

|

|

GENERAL ACCIDENT

|

12/91

|

+7

|

+25

|

-43

|

-100

|

-

|

-

|

|

GENERAL ELEC.

|

3/91

|

+5

|

+9

|

+14

|

+5

|

-7

|

-

|

|

GLAXO HDG.

|

6/91

|

+42

|

+15

|

+14

|

+21

|

+12

|

-

|

|

GRANADA GROUP

|

9/91

|

+21

|

+2

|

+23

|

-28

|

-47

|

-

|

|

GRAND MET.

|

9/91

|

+18

|

+24

|

+15

|

+16

|

+7

|

-

|

|

GT.UNVL.STORES

|

3/91

|

+24

|

+11

|

+4

|

+5

|

+4

|

-

|

|

GUARDIAN RYL.EX.

|

12/91

|

+6

|

+44

|

-41

|

-100

|

-

|

-

|

|

GUINNESS

|

12/91

|

+6

|

+25

|

+33

|

+24

|

+11

|

-

|

|

HANSON

|

9/91

|

+34

|

+11

|

+18

|

-2

|

-11

|

-

|

|

HILLSDOWN HDG.

|

12/91

|

+38

|

+22

|

+17

|

-19

|

-24

|

-

|

|

IMP.CHM.INDS.

|

12/91

|

+24

|

+13

|

-1

|

-33

|

-16

|

-

|

|

INCHCAPE

|

12/91

|

+48

|

+31

|

+6

|

-15

|

+21

|

-

|

|

KINGFISHER

|

1/92

|

+25

|

+9

|

+17

|

+11

|

+1

|

+0

|

|

LADBROKE GROUP

|

12/91

|

+28

|

+34

|

+24

|

+14

|

-40

|

-

|

|

LAND SECURITIES

|

3/92

|

+14

|

+11

|

+10

|

+16

|

+22

|

-

|

|

LASMO

|

12/90

|

-

|

-42

|

+176

|

+35

|

-

|

-

|

|

LEGAL & GENERAL

|

12/91

|

+6

|

+86

|

+3

|

-43

|

-44

|

-

|

FT-SE 100 Index continued

|

Company

|

Latest Year End

|

Growth in EPS1987

|

Growth in EPS1988

|

Growth in EPS1989

|

Growth in EPS1990

|

Growth in EPS1991

|

Growth in EPS1992

|

|

LLOYDS BANK

|

12/91

|

-100

|

-

|

-100

|

-

|

+5

|

-

|

|

MARKS & SPENCER

|

3/92

|

+22

|

+19

|

+7

|

+12

|

+4

|

-

|

|

MB-CARADON

|

12/91

|

+30

|

+16

|

+12

|

-25

|

-4

|

-

|

|

NAT.WSTM.BANK

|

12/91

|

-39

|

+116

|

-71

|

-25

|

-41

|

-

|

|

NATIONAL POWER

|

3/92

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

NFC

|

9/91

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+4

|

+7

|

-

|

|

NORTH WEST WATER

|

3/92

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+207

|

-

|

|

NORTHERN FOODS

|

3/92

|

+13

|

+10

|

+10

|

+7

|

+16

|

-

|

|

PEARSON

|

12/91

|

+25

|

+7

|

+25

|

-13

|

-24

|

-

|

|

PEN.&ORNTL.DFD

|

12/91

|

+11

|

+21

|

+21

|

-35

|

-22

|

-

|

|

PILKINGTON

|

3/92

|

+288

|

+7

|

+2

|

-7

|

-61

|

-

|

|

POWERGEN

|

3/92

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

PRUDENTIAL CORP.

|

12/91

|

+35

|

+31

|

+19

|

-53

|

+0

|

-

|

|

RANK ORG.

|

10/91

|

+25

|

+28

|

+2

|

-4

|

-41

|

-

|

|

RECKITT & COLMAN

|

12/91

|

+20

|

+23

|

+10

|

+12

|

+1

|

-

|

|

REDLAND

|

12/91

|

+29

|

+20

|

+38

|

-12

|

-41

|

-

|

|

REED INTL.

|

3/92

|

+18

|

+15

|

+1

|

+9

|

-16

|

-

|

|

RENTOKIL GROUP

|

12/91

|

+24

|

+38

|

+24

|

+21

|

+27

|

-

|

|

REUTERS HOLDINGS

|

12/91

|

+34

|

+23

|

+36

|

+14

|

+9

|

-

|

|

RMC GROUP

|

12/91

|

+38

|

+39

|

+17

|

-18

|

-36

|

-

|

|

ROLLS-ROYCE

|

12/91

|

-

|

+20

|

-0

|

-20

|

-51

|

-

|

|

ROTHMANS INTL.'B

|

3/92

|

+30

|

+16

|

+19

|

+23

|

+22

|

-

|

|

RYL.BK.OF SCTL.

|

9/91

|

-17

|

+132

|

-31

|

+5

|

-71

|

-

|

|

ROYAL IN.HDG.

|

12/91

|

-33

|

-15

|

-40

|

-100

|

-

|

-

|

|

RTZ CORP

|

12/91

|

-

|

-

|

+18

|

-19

|

-25

|

-

|

|

SAINSBURY J

|

3/92

|

+21

|

+23

|

+17

|

+24

|

+20

|

-

|

|

SCOT.& NEWCASTLE

|

4/91

|

+11

|

+11

|

+14

|

+20

|

+17

|

-

|

|

SCOTTISH POWER

|

3/92

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

SEARS

|

1/92

|

+12

|

+9

|

+12

|

-18

|

-27

|

-

|

|

SEVERN TRENT

|

3/91

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+2

|

-

|

|

SHELL TRANSPORT

|

12/91

|

+13

|

+3

|

+46

|

-7

|

-43

|

-

|

|

SIEBE

|

3/91

|

+13

|

+36

|

+16

|

+15

|

-19

|

-

|

|

SMITH & NEPHEW

|

12/91

|

+14

|

+11

|

+11

|

-10

|

-7

|

-

|

|

SMITH,WH GP.'A'

|

5/91

|

+20

|

+18

|

+13

|

+10

|

-2

|

-

|

|

SMITHKLINE BHM.A

|

12/91

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+14

|

+21

|

-

|

|

SUN ALL.GP.

|

12/91

|

-

|

-

|

-15

|

-100

|

-

|

-

|

|

TATE & LYLE

|

9/91

|

+35

|

+23

|

+29

|

+11

|

+16

|

-

|

|

TESCO

|

2/92

|

+40

|

+19

|

+13

|

+21

|

+27

|

+14

|

|

THAMES WATER

|

3/91

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+24

|

-

|

|

THORN EMI

|

3/92

|

+50

|

+40

|

+17

|

+11

|

-19

|

-

|

|

TOMKINS

|

4/91

|

+71

|

+42

|

+35

|

+21

|

+0

|

-

|

|

TSB GROUP

|

10/91

|

+62

|

+45

|

+13

|

-34

|

-100

|

-

|

|

UNILEVER

|

12/91

|

+15

|

+3

|

+30

|

+8

|

+7

|

-

|

|

UNITED BISCUITS

|

12/91

|

+14

|

+15

|

+5

|

+2

|

+5

|

-

|

|

VODAFONE GP.

|

3/92

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

+91

|

+42

|

-

|

|

WELLCOME

|

8/91

|

+33

|

+38

|

+29

|

+18

|

+25

|

-

|

|

WHITBREAD'A'

|

2/92

|

+9

|

+14

|

+13

|

+18

|

+11

|

-

|

|

WILLIAMS HDG.

|

12/91

|

+31

|

+32

|

+10

|

-24

|

+1

|

-

|

|

WILLIS CORROON

|

12/91

|

-26

|

-37

|

+33

|

+17

|

-18

|

-

|

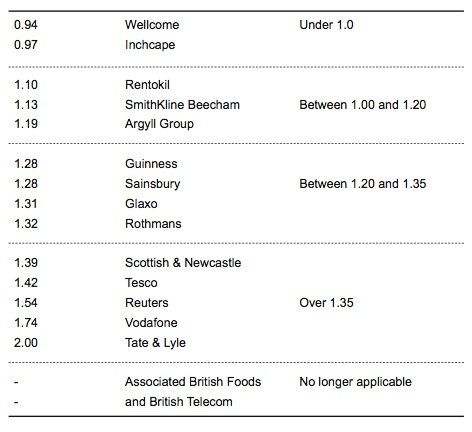

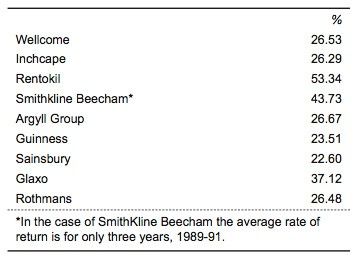

Our final list is only sixteen shares – about one in every six from the FT-SE 100 Index. Remember Chapter Seven on Competitive Advantage and notice the common characteristics of the sixteen shares. Five are in food retailing and manufacture, two are brewers and distillers and three are drug businesses with well-patented products. Rothmans has excellent international brand names and Rentokil has a very strong business franchise.

We will use the June 1992

Estimate Directory

prices and future forecasts to see how the prospective PEGs of these fine companies measure up to our increased limit of one:

1. Argyll Group

Consensus forecast for the year ending 3/93 of EPS growth of 11%. Prospective P/E ratio at 350p equals 13.1, giving a PEG of 1.19.

2. Guinness

Consensus forecast for year to 12/92 of EPS growth of 11% and 13% in the following year. At 608p the average prospective P/E ratio for 1992/3 is 15.4 against average growth of 12%, giving a PEG of 1.28.

3. Rentokil

Consensus forecast of year to 12/92 of 21% growth and 19% in following year. Prospective P/E ratio for 1992 at 179p is 23.9 and 19.9 for 1993. The average prospective P/E for the year ahead is therefore 21.9 against average growth of 20%, giving a PEG of 1.10.

4. Rothmans

Consensus forecast growth for year to 3/93 of 9%. Prospective P/E ratio at 1100p about 11.9, giving a prospective PEG of 1.32.

5. Sainsbury

Consensus forecast growth for year to 3/93 of 13%, giving a prospective P/E ratio of 16.6 at a price of 475p. The PEG is therefore 1.28.

6. Tate & Lyle

Consensus forecast for year to 9/92 of 1%, and for year to 9/93 of 10% – say 5.5% on average. At 392p, on a prospective P/E ratio of 11 with a very high PEG of 2.

7. Tesco

Consensus forecast for year to 2/93 of 9% growth with a prospective P/E ratio at 281p of 12.8, giving a prospective PEG of 1.42.

8. Wellcome

Consensus forecast for year to 8/92 of a further 24% growth with 23% forecast for following year. Prospective P/E ratio at 971 p of 21.8 for 1993, giving a prospective PEG of 0.94. A clear system buy.

9. Glaxo

Consensus forecast for 1993 of 15% growth with a prospective P/E ratio at 771p of 19.7, giving a prospective PEG of 1.31.

10. Associated British Foods

Negative forecast of minus 31% in EPS for year ending 9/92. Forget it.

11. British Telecom

Fall in earnings forecast for year to 3/93. Forget it.

12. Scottish & Newcastle

Consensus 4/93 forecast of 9%, giving a prospective P/E ratio at 467p of 12.5 and a PEG of 1.39.

13. Reuters