5

Region-Free Media

Collecting and Selling Cultural Status

“Good cinema is culture, but really all kind of knowledge is good and it’s important to have access to knowledge.” Bootleg DVD salesman Santos Demonios utters these words in a short video by Vice Media’s Motherboard about the pirate DVD trade in Lima, Peru. Titled “Peru’s DVD Pirates Have Exquisite Taste,” the report at times reflects Vice’s customary exoticizing gaze on illegal and surreptitious activities in the Global South, but it also sheds light on how distributors and retailers in certain parts of the world make do when they are cut off from formal media circulation networks. The first words of the video, spoken by Demonios, emphasize the personal, cultural, and economic importance of media access: “One has to adapt to their own economic possibilities. Unfortunately, our economy only allows us to afford piracy. Yes, piracy is illegal, but in a country that’s hungry for access to knowledge, which is also a form of development, we have to embrace illegality.”1 There is a lot to unpack in this short statement. For one, Demonios indicates that the state of media distribution networks in a particular place can be a barometer of broader economic circumstances. An intertitle expands on his suggestion that Peruvians can only “afford piracy,” telling us that Peru’s informal DVD trade stems from a combination of slow internet speeds, high costs of formally distributed DVDs, and a general lack of officially distributed films in the country.

Demonios also stresses a key premise of this book: that media products like DVDs represent cultural resources that people use to attain knowledge and participate in broader conversations about art and popular culture. Thus, informal media networks like this one respond and contribute to cultural conditions as much as economic ones. The rest of the video portrays the business practices of a DVD stand in a Lima shopping mall, where we observe Demonios and two other salesmen burning (assuredly region-free) copies of DVDs and discussing topics like their approach to packaging and their relationship with the local police. In particular, the report highlights the popularity of independent and global art films such as Blue Is the Warmest Colour (2013), The Act of Killing (2012), and Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) as well as films by French New Wave directors like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Eric Rohmer, a development the video presents as somewhat surprising (indeed, consider the attempt at irony in the video’s title, “Peru’s DVD Pirates Have Exquisite Taste”). On the one hand, the video points to some of the overlaps between informal media trades and cinephilia. On the other, the implied incongruity between the informal trade practices of the Global South and global high culture indicates that many in the West see cinephilia as a predominately Western, Anglo-American, or European experience.

The video captures two sides of region-free media that this chapter will explore further: the way region-free DVDs have sustained both informal bootleg economies and global film culture. As I have shown in chapters 2 and 3, media audiences routinely figure out ways to get around regional lockout systems. Exploring these trends, I analyze region-free media use among two broad and overlapping cultural perspectives, each of which embodies a different set of power relations within the global mediascape: diasporic media culture and cinephilia. By showing that region-free media use is not just one thing but rather a heterogeneous series of practices, I argue that the cultural politics of region-free media are more ambivalent than many of its promoters or detractors—whether film critics, copyright activists, consumer rights groups, lawmakers, or media industries—might suggest. Focusing primarily though not exclusively on the use of region-free media forms in the Global North, I begin with an analysis of region code circumvention and region-free DVD use by diasporic video retailers in the United States. Drawing in part on interviews with several owners and employees of diasporic video stores, I show how the circumvention of DVD region codes can represent both a bottom-up challenge to the distribution routes and global space-time relations of dominant media industries as well as a more everyday practice of making cultural resources available to local immigrant populations. When media important to these communities are not released in the United States through formal means, such retailers import and create region-free DVDs for their consumers. While this research reveals uses of region-free media by the less powerful, the next case study shows how region-free DVD cultures can also reflect an ironic yet common blend of cosmopolitanism and cultural dominance. I illustrate this through the long-standing use of region-free DVD by cinephiles, collectors, and cultists who seek out global film culture. Often, such practices represent an admirable desire to engage the wealth and diversity of global cultural production. At the same time, they can manifest as cultural tourism laced with overtones of masculinized cosmopolitanism and a commoditizing collector’s mind-set.

Figure 5.1. Bootleggers offer Peruvians access to film. Screenshot: Motherboard, “Peru’s DVD Pirates.”

This chapter shows that digital regulation’s effects are not always uniform. Even if a particular form of technological regulation has a relatively simple and straightforward impact on the affordances of a media technology, the way users take up, understand, interact with, talk about, and circumvent it will reflect a multitude of viewpoints and user practices following different political trajectories. The unauthorized trade and consumption of, say, The Blue Angel (1930) or Floating Weeds (1959) from the UK’s Eureka Entertainment / Masters of Cinema line can function both as an act of cinephilic, completist consumption and as an action that retains some bit of control over distribution routes traditionally shaped by formal media industries. Even more so, the existence of bootleg copies of Senegalese films in a shop in Harlem, New York, operates at least in part as a media “contra-flow” that exists alongside and even in opposition to formal circulation networks.2 Still, by ending on a note of critique levied at the ways region-free media culture can in fact reinforce dominant cultural power, I argue broadly that we should not always and necessarily presume that media practices are politically progressive simply because they seem to oppose powerful industries and copyright regimes. Such practices certainly can be resistant or subversive, but often they simply reflect consumerist logics that view access to media products as a benchmark for equitable participation in the global mediascape. And while this chapter primarily explores the use of region-free media to access various kinds of nondominant or niche media, it similarly shows that regional lockout and its circumvention by users exist on a more complex axis of cultural politics than one that would simply posit “lockout = bad, circumvention = good.”

If the previous four chapters emphasized cultural industries’ regulation of media technologies, this chapter focuses more on how people have responded. In analyzing the meanings of region-free media, I provide sketches of a history of region-free media culture, focusing in particular on the emergence and adoption of region-free DVD players while touching on other circumvention practices. These histories complement earlier analyses of the DVD region code (chapter 1), region-hacking gamers (chapter 2), the use of proxies and VPNs to get past geoblocking restrictions (chapter 3), and the perceptions of digital media’s cosmopolitan potential (chapter 4) by illustrating how region-free DVD’s popularity resulted in a broader global conversation about regional lockout’s economic, regulatory, and cultural effects. DVDs offer an instructive case study of region-free media culture for a couple of reasons. For one, they provide a historical perspective on both region-free media and forms of cultural regulation more broadly. Indeed, DVD was the first medium to provoke widespread public discussions of regional lockout systems, and its relationship to the DVD’s CSS encryption meant that it was often incorporated into public discourses about copyright, digital rights management, and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Second, I have touched on circumvention practices around other media forms in the previous chapters, and so this chapter affords an opportunity to focus more closely on the cultural politics of one particular region-free medium in a few different cultural and political-economic contexts. As a result, the chapter adds further layers to my argument about the DVD’s significance as an institutionalizing force for regional lockout and a forebear for the lockout systems that would come to be installed in streaming platforms even as the world supposedly moved out of an era dominated by “physical” media.

Region-Free Media Cultures

Region-free media refers to any media technology, text, or experience that consciously and intentionally rejects regional lockout systems. It can manifest in multiple ways across a host of media technologies: multi-region DVDs and DVD players; video game consoles that have been hacked to play game discs and cartridges from around the world; and VPN and proxy services that allow users to connect to streaming video and music platforms unavailable in their area. As this indicates, region-free media operate at the levels of both hardware and software (and in the interactions between the two). Furthermore, as I showed in chapter 2, region-free media are not new. Methods of hacking regional lockouts and incompatibilities existed in video game culture as far back as the 1980s, and users have adapted lockout circumvention practices to virtually every media delivery technology that has come into existence since.

Region-free media embody a number of practices revolving around particular technologies that allow users to circumvent regional lockout. The region-free DVD can thus be considered its own kind of format, existing in relation to but still distinct from “region-coded” DVD, with its own set of meanings and protocols. Jonathan Sterne argues that the concept of a “format” “names a set of rules according to which a technology can operate.”3 Although it is an offshoot of the DVD format, region-free DVD operates according to its own set of rules different from those of region-coded DVD. Furthermore, region-free DVD’s social and cultural meanings are different from those of region-coded DVD, suggesting an entirely different set of viewing and distribution practices. With this in mind, considering region-free media as not simply a technology but as a cluster of cultural practices offers a fuller illustration of how it shapes media tastes and circulation networks.

Many who engage in or promote region-free media cultures present them as clandestine and subversive antiestablishment practices. This viewpoint is evident in some of the pioneering scholarly work on region-free DVD. In his piece on DVD region codes, for example, Brian Hu sees the use of region-free DVD players as, in part, a form of “fan agency” against Hollywood’s distribution routes and technological standardizations.4 Drawing on Hu’s reading, Tessa Dwyer and Ioana Uricaru point out that the practice of hacking region-coded DVD players was key to accessing uncensored and native-language fan subtitles and pirate media in Romania.5 Without explicitly drawing on it, such framing recalls John Fiske’s de Certeauian view of popular culture as “using their products for our purposes.”6 In this formulation, the power of popular culture comes from how people mobilize it against dominant orders.7 Extending this to unauthorized media uses (not much of a stretch given that Fiske illustrates his analysis through the example of shoplifting), piracy and lockout circumvention can be read not simply as acquiring a product through different means but as an affront against the systems of markets and power within which that product exists. The interactive affordances of digitally networked technologies, which easily enable piracy and lockout circumvention through proxy servers, seemingly intensify the possibility of making consumption productive.

Thus, with piracy and lockout circumvention, the lack of consideration for traditionally understood global space-time relations is just as potentially transgressive as the theft of a product. Given global cultural industries’ reliance on controlled distribution, the space, place, and time of consumption become important for accumulating capital. Whether critical or celebratory, the circumvention of regional restrictions is often rhetorically presented as placeless—as a transgression of geography and the social and consumptive norms that accompany geographical rootedness. One critic of geoblocking notes that “the makers of music videos, TV shows and movies still think nationally . . . but file sharing already knows no borders . . . Technology will roll right over those ‘Not available in your country’ notices in due course.”8 The material threat to media industries’ bottom lines is obvious, but there is a broader, more abstract form of transgression taking place here. If recognition as a subject partly relies on one’s location within a matrix of power and signification informed by geographic structure, lockout circumvention on some level represents a challenge to these structures. David Morley points out that placelessness and mobility tend to be pathologized as “geographical deviance” in a world that places individuals and groups in fixed locations and categories.9 Writing specifically about the circumvention of regional restrictions on media, Morley reminds us that “in an era of electronic communications, conflict is conducted by the invasion not only of geographical but also of virtual territory.”10 Such conflict results in what Ramon Lobato calls the “proxy wars,” or the policies and mechanisms developed by a platform like Netflix to push back against VPNs and proxies as means of unauthorized global access.11 As evidenced in the BBC iPlayer example from chapter 3, this conflict can take place between users and forces of power, but it can also take place between users residing in different territories.

A more celebratory take on placelessness and geographical deviance is apparent in the websites and brand logos of file-sharing, proxy, and VPN services. Often, these draw on diverse images of global travel: seafaring pirates, cosmopolitan globalism, freedom from the shackles of bondage, clandestine disguise, and even guerilla warfare. Drawing on the popular image of the “pirate” as a pillager roaming through international waters and unmoored from normative geography, the Pirate Bay torrent site famously presents an emblem of a pirate ship in which the Jolly Roger has been replaced by the logo for the 1980s “Home Taping Is Killing Music” anti-copyright-infringement campaign. The logo for the proxy database site Xroxy.com was at one time a globe adorned with several national flags. This not only suggests an image of global communities ignoring corporate-defined borders, it promotes a more open internet as a window to an engagement with global culture. Adopting a more antiauthoritarian approach, another proxy site, PublicProxyServers.com, uses as its slogan “Breaking chains since 2002.” The logo for the VPN service Hide My Ass! puns on its name by presenting a donkey adorned in a Sam Spade–like trench coat, fedora, and sunglasses. The logo for the proxy service Proxify likewise incorporates a camouflage fatigues color scheme.

Nevertheless, many who buy and sell region-free media products do not do so with the goal of undermining more formal networks of circulation; they simply want to access the media they want to watch or listen to on the consumer end and make some money in meeting that demand on the supply end. On the part of torrent and VPN services, the use of clandestine and subversive imagery is as much a branding strategy as it is a pronouncement of taking up arms against oppressive corporate forces (the informal flip side of Spotify’s cosmopolitan global brand discussed in chapter 4). This is not to minimize the political power of region-free media—particularly when it comes to issues of identity, taste, and cultural globalization—but simply to complicate it. Region-free DVD uses among cinephiles and diasporic groups offer more than simplistic David-and-Goliath, consumers-versus-studios stories.

Region-Free DVD

Region-free DVDs and DVD players have been around as long as the DVD itself. In some places, they even preceded the format’s launch. One trade report from 1998 notes that region-free players were beginning to show up in London even before the DVD was introduced formally to the UK.12 By this point, UK and European consumers in particular were used to the headaches that could come with living in a secondary market for global home video, and they were keen to avoid many of these same issues with the introduction of DVD. Given the prevalence of region-free players throughout Europe, and the fact that Hollywood could not use language as a natural barrier against import as easily as it could in other regions, the region became particularly problematic for Hollywood’s maintenance of its distribution windows. One estimate from 2000 suggested that 75 percent of DVD players in Europe were region-free.13 A trade report from the same year suggested that in Europe, region codes were “almost a non-issue” due to the widespread use of region-free players across the continent.14 Usually, because many major films at this time were emanating from Hollywood, which was still engaging in staggered global release dates, many region-free DVDs or parallel imports manifested as bootlegged Hollywood products entering overseas territories before a film’s official release. While region-free discs and players were often sold and adopted to play imported Region One DVDs, there are plenty of examples of region-free media flowing in the other direction. In 2001, for instance, reports surfaced of official Region Three and bootlegged region-free DVDs of Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon making their way to the United States while the film was still in theaters, as the title had been released in Singapore theaters five months before its American debut.15

As this indicates, Europe was far from the only region with a high demand for region-free DVD. Many places with less geocultural capital in global film markets found themselves stocked with players and discs to get around regional lockout. If anything, such resources could be more common in spaces that Hollywood did not track as closely as they did their secondary markets. A report from late 1998 notes that the Middle East saw an increased demand for imported European DVDs, and region-free players were beginning to become available to consumers.16 As early as 1999, region-free players could be found easily in Mexico and throughout the rest of Latin America.17 Soon enough, they became accessible to consumers around the world. One trade report from 1998 noted, “Retailers in [the] Far East already are doctoring Pioneer players before sale to consumers, while [the] European company Techtronics will modify [a] variety of brands for [a] $65 service fee.”18 North American trades, industry types, and news sources often discursively construct region-free DVD players as threatening to industrially sanctioned distribution, and Western press discourse about region-free DVDs and DVD players posits these technologies as bootleg products invading trade routes from far-off regions. Trade and news reports refer to “cheaper DVD players from the Far East,” and in 1999 a number of studios stopped adding Spanish-language tracks to Region One DVDs because they feared these discs were making their way to Latin America through unauthorized distribution routes.19 Here, region-free DVD players stand in for a potentially dangerous, immigrant Other, invading places they do not belong, a common trope in talk about bootleg technology. In chapter 1, I argued that DVD region codes were a system of representation as much as one of regulation because they offered a means by which powerful institutions could represent the rest of the world. The characterization of region-free technologies as emblematic of leaky borders is not just an issue of media economics; it also reflects broader anxieties surrounding border transgression.

Around this time, people began using the internet to access instructions on how to purchase region-free players or hack their players in order to play region-free DVDs.20 Websites like the now-defunct DVD Utilities Resource Center spread information on hacking, and like-minded message boards figured as spaces where users could circulate knowledge on the various methods of circumventing regional lockout systems.21 For DVDs, one can buy discs without region codes, purchase a region-free player, or hack a conventional player in order to make it multi-standard. The latter involves a number of different technological fixes that range from physically rewiring the player to simply pressing a combination of buttons on the remote control that result in an overriding of the region coding system. Among other things, this functioned as an opening up of hacking and other unauthorized media practices and competencies to a broader base of consumers, even well before the concept of “lifehacking” made the relative democratization of hacking culture more banal. These extended well beyond the DVD. Although Blu-ray has in some ways loosened regional restrictions (as some studios simply do not bother region-coding their discs), it is in many ways more difficult to circumvent regional locks on Blu-ray players and discs. One Australian writer describes his experience of paying $1,000 for a region-free player before stumbling on a cheaper player that included a firmware disc that let him reset the player for different region codes.22 Furthermore, as shown in chapter 2, gamers have long undertaken rather involved measures to ensure that cartridges or discs from one part of the world can play on consoles from another.

As these examples indicate, it would be far too easy to suggest that media distribution routes have always followed the contours of regional lockout maps. At the same time, the question of whether region-free media made the region code system dysfunctional is a complex one. Brett Christophers argues that this conclusion is too simplistic: “The studios, surely, would not be investing large quantities of time and money in lobbying for the continued application of region coding if they believed that they were not longer realizing meaningful economic benefits from doing so.”23 This constant push and pull between control and resistance characterized public battles over region-free DVD. In the context of the format’s emergence and popularization, cultural commentators and advocacy groups framed region-free media as an issue of consumer rights. Examples abound of popular references to region-free DVD players giving consumers “more choice,” and consumer rights groups have long been critical of region codes.24

Consumers did not always have to take it on themselves to learn how to hack region-free technologies. Often, they had help from media retail establishments. Although the trade in region-free media has many connections to informal, bootleg media networks, locating region-free players and discs did not prove particularly difficult for people in larger metropolitan areas. While the importance of retailers in region-free media culture is particularly evident in the bootleg production and circulation practices of video stores catering to diasporic groups, more formal retailers and big-box stores (particularly outside the United States) have also had a hand in helping consumers overcome regional lockout. This is because it is often more lucrative for local distributors and retailers to ensure that consumers have the hardware and software they want rather than adhere to the distribution routes of the Hollywood studios. As the Sydney Morning Herald reported in the first few years of DVD’s existence, “Local DVD retailers say the demand for multi-region DVD players is so high they regularly premodify players to ensure a minimum of delay for consumers.”25 Reports of major chains like Tesco in the UK and Circuit City in the United States selling region-free players were common in the late 1990s and early 2000s.26 Around this time, Tesco wrote a letter to Warner Home Video president Warren Lieberfarb, unsuccessfully lobbying for the elimination of region codes.27 Indeed, such retailers have helped users get around regional lockout systems for as long as DVD players have been around. As early as 1998, a report on region-free players in London discusses one shopkeeper who eagerly demonstrates to the writer how to hack certain players to bypass region locks and explains which studio’s discs are harder to hack.28

Furthermore, the emergence of online media retailers like Amazon, Deep Discount DVD, and region-specific sites like YesAsia made accessing global media even easier. In the early years of DVD, such online retailers were similarly nascent, and the potential riches of borderless online purchasing and the desire to gain greater access to digital media culture through region-free media seemed a perfect match. Indeed, part of the reason manufacturers and retailers began making and selling region-free DVD players was to meet the demands of non-US consumers who ordered Region One DVDs from online retailers.29 Much of this discourse promoted a vision of digital distribution that Chris Anderson would famously theorize as “the long tail,” the idea that online distribution would focus less on big hits and instead help reach niche consumers by eliminating scarcity and making obscure and specialized products more easily available.30 Here, those served by the long tail were the consumers who would push against Hollywood’s will and seek out region-free DVD.

Region-Free DVD in Diaspora

On the whole, a fairly diverse group of consumers make use of region-free media: cinephiles interested in global film; anime fans in East Asia, North America, and elsewhere; gamers using physical and digital hacks to import and play discs and cartridges; ex-pats and people in the military; and ultimately anyone who has the motive and the initiative to access media from across borders.31 One of the more prominent audience segments for region-free DVD has been immigrant and diasporic communities. The reason for region-free media’s popularity among diasporic people is evident enough: they enable viewers to more easily consume media from other territories, such as one’s home country. Likewise, burning and converting region-coded DVDs into region-free DVDs and DVD-Rs make the circulation of films and television programs from one’s homeland or from another part of the world much easier. The histories of diasporic home video circulation are multiple, heterogeneous, and impossible to catalog in any cohesive manner, but they generally reveal communities building up semiformal and informal distribution and retail infrastructures that circulate films and film culture otherwise ignored or blocked by formal, dominant media distribution routes.

Throughout much of the world, the destination points for many of these region-free imports are the video stores that cater to diasporic people. On one level, these video stores are spaces of niche, narrowcast migrant media culture.32 On another level, as businesses woven into immigrant communities as well as spaces of neighborhood gathering and discussion, they are part of what Stuart Cunningham calls diasporic “public sphericules,” or community-based public spheres sustained in part through engagement in diasporic media culture. Video stores—and diasporic media more broadly—can help fulfill public sphericules’ charge to “provide a central site for public communication in globally dispersed communities, stage communal difference and discord productively, and work to articulate insider ethno-specific identities—which are by definition ‘multi-national,’ even global—to the wider ‘host’ environments.”33 Because video stores function as nodes in the circulation of diasporic media, they offer cultural resources that viewers can use as sites of identity affirmation and negotiation.34

As several studies have shown, diasporic video retailers do not trade only in video. Often, they are more generally focused retail establishments such as grocery stores or electronics and housewares stores that also sell videos. Dona Kolar-Panov’s survey of video stores in various Australian suburbs showed that while few formal video stores contained material in languages other than English, other kinds of business establishments like newsstands, delis, and pharmacies contained non-English-language videos, usually “determined by and directly linked to the ethnic background of the shop owner.”35 Writing about the Indian-American diaspora, Aswin Punathambekar points out that a period of intensified migration in the 1980s saw a boom in family-owned Indian grocery stores that also sold bootlegged videocassettes of Hindi films.36 As Bart Beaty and Rebecca Sullivan show, Asian diaspora communities were in large part responsible for the proliferation of region-free DVDs and players as a way to more easily import Pacific Rim cinema to Canada.37 Writing earlier, Glen Lewis and Chalinee Hirano show in their study of Thai video stores in Australia that such establishments began popping up in the 1980s, with grocery store proprietors asking relatives in Thailand to send recordings of Thai television programs.38 Together, these portraits of global diasporic video culture indicate a combination of formal and informal distribution networks linked to family, national identity, and transnational distribution routes.

Region-free DVDs move among diaspora communities in ways that reflect Arjun Appadurai’s vision of commodity flow as “a shifting compromise between socially regulated paths and competitively inspired diversions.”39 When they diverge from media industries’ preferred paths, they are part of the “shadow economies” of media distribution existing alongside (and even in place of) more formal distribution and retail infrastructures.40 These operate as crucial points of media access for many around the world, and particularly for those living in and hailing from the Global South. Indeed, trade journals and industry lore about region-free media connected the circulation of region-free DVD players to a broader network of informal commodity trade. In 1999, the US-based trade magazine Audio Week reported on a Hong Kong–based electronics company that represented a “one-stop source for ceiling fans, vacuum cleaners, lighting fixtures—and DVD players whose regional code settings can be changed or overridden.”41 Audio Week’s occasionally pathologizing invocation of these players’ “mysterious origin” characterizes the view that the Global South’s media manufacturing and distribution institutions operate outside the domain of accepted, traceable, and knowable media industries. Indeed, beginning in the late 1990s, customs officials in the UK and the United States began to seize shipments of DVD players from Asia. These officials claimed that this had more to do with the players’ “lack of compliance with electrical standards” than their lack of regional encoding, but the hardware’s ability to violate intellectual property regulations assuredly played a part.42 Whatever the reason, such seizures indicate an anxiety surrounding the unauthorized import of cultural products.

To understand region-free DVD’s specific role in diasporic media access, I observed and interviewed employees and proprietors of diasporic video stores serving a variety of Global Southern diasporic communities in the United States—specifically, in the metro areas of New York City, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Madison, Wisconsin. In general, I found that the impacts and cultural politics of regional lockout and region-free media on diasporic media cultures are a mixed bag. For some, regional lockout is a minor annoyance—ripping and burning DVDs in order to overcome such restrictions is a regular part of the workday. For others, it hardly registers at all, particularly for those stores that receive shipments of DVDs that are already region-free. For still others, however, it affects their consumers’ ability to gain access to resources that can figure as an important site of “cultural continuity” or negotiation, in the words of Lewis and Hirano.43

Of course, not all diasporas are equal and thus cannot be fully understood through one explanatory or analytical framework. This is to say that the observations here are more a comparative survey of region-free practices than a sustained study of one particular group. This view reveals some differences in diasporic DVD retail practices, but it highlights one thing many of these stores have in common: a predilection toward bootleg DVDs stripped of region codes. The pervasiveness of region-free media in diasporic life illustrates a complicated mixture of the subversive and the everyday. While some have argued that piracy and parallel imports transgress media conglomerates’ mechanisms of spatial control, the presence of parallel imported and region-free DVDs in these stores seems far more ordinary.44 The hard-to-find shelves, bootlegged tapes, and handwritten labels discovered by Lucas Hilderbrand in his own analysis of Korean video stores in Orange County, California, are readily apparent, but these conditions are common realities of media distribution in diaspora communities more than overtly transgressive pirate practices.45 Part of this reality is a common awareness of regional lockout and how it works. Shelves and DVDs are regularly marked with signs or stickers that either indicate which region the DVDs come from or note their region-free status. A Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, store specializing in Russian goods includes large “PAL” stickers to indicate DVDs that will not work on NTSC players and televisions. One store in the Koreatown neighborhood of Manhattan includes some region-free DVDs, but it also includes many Region Three DVDs, which are labeled as such. These are common sights in stores that offer media products from around the world.

The perceived impact of these regional lockout systems on the customer depends on the individual establishment. While many stores do what they can to instruct customers on what region codes are and how to circumvent them, others simply eschew region-coded DVDs altogether in favor of region-free discs. Whether regional lockout is a headache for such stores seems to be determined by how easily they can rip and burn DVDs, how easy it is for their customers to do so, or whether they can acquire DVDs without region codes. Often, this will depend on which national or regional industry produced them. The manager of an Indian / South Asian DVD shop in the basement of a shopping center in Jackson Heights, Queens, told me when I asked if his DVDs were region-coded, “The DVDs that we have, you can watch it anywhere in the world . . . [region codes] are only for India. If you go to India then you get it in PAL, and the VCD you get it in PAL. The English original movies that they sell down there where they have the rights in India, everything is in PAL, but Indian movies are not. Indian DVDs are not. They’re region-free.”46 Although understandably evasive on where his DVDs come from, his response stresses that not all region-free DVDs are bootlegs. Indeed, some are legitimately produced and formally distributed discs wherein the publisher has opted to use discs without region codes, as in the Indian DVDs he discusses. Some stores were careful to point out that their region-free discs were on the up and up. When I asked an employee of a Milwaukee-based Indian grocery store about region codes, he stressed, “These are all region. I know other places have copies that are pirated, but we don’t. Only legal copies.”

Still, bootleg practices abound. For many stores, when DVDs do arrive with region codes intact, they find measures to get around them—usually by ripping and burning new copies of the region-coded DVDs. An employee of an African DVD store I visited in Harlem’s Le Petit Sénégal neighborhood indicated somewhat vaguely that the store owns a “converter” that can change the region code (presumably, this would simply be a process of ripping and burning the DVDs onto different discs rather than a process of “converting” the hard-coded Regional Playback Control encryption). Indeed, many of these stores are not shy about their methods—a woman sitting outside the above-mentioned Jackson Heights store was actively burning DVDs and printing cover art from a laptop computer. In another indication of the small, one-room store’s informal nature, the shop also included an older woman tailoring clothing for sale next to the racks of DVDs.47 Another Milwaukee store—an Indian grocery store/restaurant that also sold a handful of DVDs—presented its inventory as haphazardly organized stacks of DVD-Rs with handwritten labels in a few small plastic baskets. When asked about region codes, the manager told me, “These are all copies, so they will play on any DVD player. Back when we opened the store, we had to buy a bunch of convertors . . . and we spent $500–$600. And now those are sitting in my garage.” Though the specific methods may change, the practice of finding region-code workarounds remains.

The common reminders of regional lockout (as well as its circumvention) speak to the diasporic video store’s status as a hybrid space, one existing on a spectrum from formal to informal and reflecting the complex geography of global cultural interaction. Indeed, many stores contain a blend of various national and regional cinemas (like Telugu, Tamil, and Bengali films, for instance, in South Asian video stores, and Senegalese and Nigerian films in a Harlem Senegalese DVD store) alongside bootlegged versions of mainstream American films. Getting around region codes thus helps make the DVD a more fundamentally global medium, in the sense that it enables easier access to a diversity of films from various parts of the world. These transnational dynamics were apparent in discussions with the managers and owners even as they were generally vague about precisely where their DVDs originated. Indeed, many of them spoke to both formal and informal networks of transnational commodity distribution. After the Milwaukee employee stressed the legality of the store’s product, he proceeded to explain that their DVDs come from wholesalers based in Chicago’s Devon Avenue Indian neighborhood who received their shipments from India or elsewhere in South Asia.

This reference to local and translocal distribution, however, reveals the significance of local communities in region-free media culture in addition to transnational ones. Diasporic video stores serve as important sites of gathering for people to gain access to culturally proximal media and cultural resources—resources that would be difficult if not impossible to access without region-free media.48 Speaking to the idea of diasporic media as part of a “public sphericule,” workers reiterated that their customers are mostly members of the diasporic communities in the immediate area. Although they are different in their urban and diasporic character, these establishments have similarities to the small-town American video stores analyzed by Daniel Herbert in his book Videoland, in that they “interweave movie culture with a wide variety of local conditions and concerns.”49 By serving particular, localized, and usually ethnically specific populations, diasporic video stores are saturated with and help structure the cinematic tastes and broader cultural matters of the surrounding community. Catering to what James Clifford refers to as the “crucial community ‘insides’ and regulated traveling ‘outsides” of diasporic neighborhoods, their proprietors and employees see themselves as serving a simultaneously local and transnational community.50 This is especially the case in a place like New York, where the size of the city and the development of diasporic neighborhoods has resulted in the existence of particular ethnic enclaves (e.g., Greeks in Astoria, South Asians in Jackson Heights, Latinos in East Harlem). As spaces of reterritorialization amid the deterritorializing processes of globalization and migration, these neighborhoods are at once differentiated communities and spaces influenced by global processes.

Because these stores carry hard-to-find films and television programs from around the world, their customers occasionally spread beyond their relative diasporic customer base.51 Indeed, part of what gives the United States (and particularly large cities like New York) a wealth of geocultural capital in the global entertainment environment is the opportunities it gives to find relatively rare cultural products. One employee of a Japanese book and video store in Midtown Manhattan told me that while the Japanese-American diaspora made up a large part of his customer base, he also regularly sells DVDs to American anime collectors. In Milwaukee, the manager of an Indian grocery store told me, “Some whites come to buy spices or to eat, and they say they’re interested in Bollywood,” and a manager of an Indian DVD store in Jackson Heights, Queens, similarly said, “I have Spanish and white customers in here as well, watching Indian movies.” These dynamics became even more apparent to me in my interviews: in general, interviewees met my questions with less reticence once I expressed knowledge about the directors, films, and genres for sale or rent at these establishments. For example, the employee of the store in Le Petit Sénégal opened up and talked with me quite a bit more once I mentioned the legendary Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène. He seemed to acknowledge my awareness of Senegalese cinema as a genuine interest in the workings of his store and the flows of African film culture rather than rote or suspicious information gathering. As a result, we had a conversation that lasted quite a bit longer than some of my interviews in other stores, and he gave me two (bootlegged, region-free) Sembène DVDs as a parting gift when I left. Similarly, in many stores catering to the Indian-American diaspora, proprietors were more likely to talk to me once it was clear that I understood that “Bollywood” is not synonymous with “Indian cinema.” My awareness of other regional cinemas in India and Senegalese directors like Sembène is also indicative of my own privilege and cultural capital, as I have had access to a film and media education that has contributed to my interest in and knowledge about these global film cultures. All this is to say that while diasporic video stores’ trade in region-free DVD helps sustain the cultural practices of particular diasporic communities, it also taps into a broader circuit of global film viewing that sees such video stores as sites for the accumulation and trade of cultural capital.

Region-Free Cinephilia and Cosmopolitanism

Throughout the late 1990s and the 2000s, much resistance against DVD region codes articulated two schools of thought. The first is the idea that cinema is a purely global art form that should encourage the free flow of films across borders and the appreciation of cinema from other countries. The other, discussed throughout this book, is the notion that the internet and digital media technologies more broadly would open up the world and make this free flow possible. The former is in part an outgrowth of cinephilia, a particular mode of film spectatorship and thought represented by a transnational cluster of like-minded film critics and appreciators. Cinephilia corresponds with a certain approach to taste that encompasses art house and cult movies and comes about in part through a privileged relationship to film. Scholars have pointed out similarities to the “art critical discourse of connoisseurship” and called it “a kind of aristocratic cine-literacy.”52 In other words, cinephilia requires not only the time and financial capital to seek out and watch as many movies as possible, but the cultural capital to appraise and appreciate particular films, directors, and national cinemas. In this vein, it involves a recognition of the “globalness” of cinema as an art form and space of cultural engagement. Thomas Elsaesser points to the transnational routes endemic to the cinephile experience when he writes, “Cinephilia . . . is not simply a love of the cinema. It is always already caught in several kinds of deferral: a detour in place and space, a shift in register and a delay in time.”53 In addition to the temporal deferrals of rediscovery and nostalgia, cinephilia functions as a geocultural and spatial kind of detour—an engagement with emblems of international culture that follow various transnational distribution paths on their way to the audience. In this way, it intersects with what Henry Jenkins has called “pop cosmopolitanism,” the cultivation of a kind of global awareness through media and popular culture. While cinephilia and pop cosmopolitanism have different relationships to taste, they both speak to media culture’s ability to offer opportunities for intercultural engagement.54

For many cinephiles, digital platforms like the DVD promised a democratization of global film culture, something seemingly impeded by region codes.55 Thus, it was only natural that they would begin to get around this form of DRM. A 1999 editorial from The Australian with the demonstrative headline “Studios Divide and Rule to Keep Movie Disc Titles Scarce” makes a case for circumventing regional restrictions on cinephile grounds: “The film studios eventually will have to come to their collective senses and realize that film, the most universal of the arts, should be region-free and truly international. Until then, it gives great satisfaction to thwart them.”56 The editorial points to region-coded DVDs as an impediment to “film junkies” with “catholic” tastes, as the author describes himself. Around the world, critics and cultural commentators with similar preferences extolled the virtues of region-free DVDs and DVD players as a way to access global film culture. New York Times critic Manohla Dargis wrote in 2004 that cinephiles had to take on some agency in the face of a homogeneous cultural market and “become their own cultural gatekeepers, to reach beyond the multiplex and chain video store. You have to seek—sometimes quite resourcefully—in order to find.”57 As she explains, part of that resourceful engagement involves finding and purchasing region-free DVD players. Throughout the 2000s, cinephilia-minded film critics in the United States like Jonathan Rosenbaum, J. Hoberman, and Dave Kehr regularly promoted region-free media, and Rosenbaum in particular has long been one of the United States’ premier champions of region-free film cultures. His long-running Cinema Scope column “Global Discoveries on DVD” acted as a consumer report of differently encoded DVDs for cinephiles who owned region-free players. In his initial installment of the column he writes, “The word is still getting out about the riches that are currently available to cinephiles owning DVD players that play discs from all the territories.”58 With the flourishing of film criticism on blogs and the development of social media platforms that could connect viewers and critics from different parts of the world, knowledge about different global film movements as well as ways of accessing and appraising films from these movements (including through region-free DVD) circulated among this loose community.59

This mode of region-free consumption often involves an auteurist mode of cinephilia, wherein many who hunt down region-free DVDs collect international art films and the works of certain directors. Region-free DVD is essential to these completists: not only because of the wealth of films that have not been released in various markets around the world, but also because North America’s premier distributor of high-quality DVDs of classic and global art films—the Criterion Collection—encodes its DVDs and Blu-rays as Region One and Region A, respectively. In fact, the Criterion Collection remains steadfast in region-coding its Blu-rays, even as other distributors have eschewed region codes. The reasons for this are that Criterion sees its market as North America specifically and does not own the international home video distribution rights for many of the films in its collection (hence its now-defunct streaming VOD service, FilmStruck, also being made available only in the United States). Because Criterion serves cinephiles primarily—what Barbara Klinger calls a “true upper-crust niche market”—the line’s region coding has become a topic of debate and discussion among its fans.60 As a response to Criterion’s region codes, some users bristle at what seems to be a contradiction between the line’s celebration of films, directors, and cinemas from all over the world and its propensity to lock down its products for the North American market. As one blogger puts it: “There’s something fundamentally wrong with The Criterion Collection ending up as an exclusively American endeavour, because the series has always prided itself on recognising global contributions to cinema. The films are selected from around the world, reflecting different eras and perspectives, and they represent the whole world. These films are an encapsulated example of world-wide cinema at its very best, so it’s hypocritical to restrict access like this.”61 The author goes on to invoke the commonly held idea that digital distribution technologies should forge easier connections across geographic borders and that technologies like region codes betray these possibilities. He argues that Criterion would do well to follow the “general trend . . . towards a region-free world, which is great from a conceptual point of view—the free market and the global village in action, the notion of a global film community becoming closer to a reality.”62 This kind of rhetoric, which marries the free-market tech utopia of the Californian Ideology with a vision of cinephilia as a transnational community, takes up region-free media as essential to film culture reaching its full potential of cosmopolitan globalism in a digital age.63

If Hollywood would not rethink its commitment to region codes, then local video stores took up the charge of selling region-free film culture to consumers. In addition to the diasporic stores described above, establishments like Scarecrow Video in Seattle, Washington, and I Luv Video in Austin, Texas, serve the aforementioned cultist and cinephile groups with their shelves stocked with obscure cinematic texts in a variety of different region-coded and region-free conditions. This exemplifies the relatively high geocultural capital of the United States as well as particular cities within it: they are places where people can access a range of different films from around the world, some of them rare or impossible to find outside of informal economies. Indeed, these sorts of stores are often located closer to the metropolitan centers of cities rather than the ethnic enclave neighborhoods that (as in the case of many of the neighborhoods visited in New York) often develop in the peripheries of urban areas. Such locations better exemplify what Herbert calls “video capitals,” or well-known, often independently owned video stores that carry a wide variety of videos and “exhibit a highly detailed, comparatively sophisticated understanding of movie history and aesthetics” in part through their cinephile employees and detailed, knowledgeable methods of categorizing their titles.64

Although cosmopolitan cinephilia has generally been centered in major metropolitan areas, DVD opened up the possibilities of global film viewing to cinephiles who did not live near repertory theaters or art houses—a trend exacerbated by the relatively easy accessibility of region-free players. This is evident in a letter to the cinephile-oriented magazine Film Comment by a reader from Grand Rapids, Michigan, who writes, “I continue to be grateful and impressed for/by the ever-increasing accessibility of undistributed and neglected films on DVD. With a region-free player, people who live in cities without major festivals can catch up with major films a lot faster than they were able to before.”65 Similarly, Joan Hawkins argues in her mid-2000s work on art horror that the “mainstreaming of exploitation [film]” was taking place not in art house theaters but “at the level of DVD sales and stock” because it is easier for farther-flung fans to gain access to obscure media that way.66 In this context, region-free players are often appealing to fans of particular global film and media movements, and distributors and retailers who address these fans ensure that such consumers will be able to watch region-coded DVDs. As Hawkins points out, various boutique DVD dealers like Facets Multimedia, Luminous Film and Video Wurks, and Nicheflix (now defunct) regularly stock and distribute DVDs from all regions and point their customers toward sites where they can purchase region-free players.

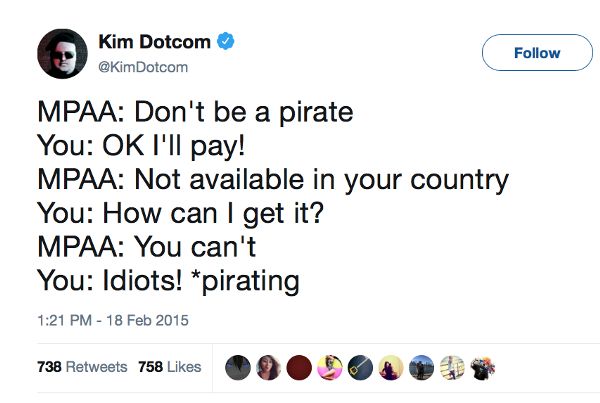

While region-free players were not particularly difficult to find (or produce by hacking a region-coded machine), awareness of global film culture and technological acumen were necessary to know that DVDs were region-coded in the first place, much less that region-free players existed. Although some might point to the possibilities of DVD for the democratization of media culture, region-free DVD represents a space where people in particular taste cultures share obscure knowledge that may be inaccessible to outsiders. The subcultural capital of region-free media culture manifests as insider knowledge expressed through an awareness of not only particular directors and filmmaking communities, but also the political economics and cultural geography of global media circulation and one’s place within it.67 By eschewing dominant tastes, cinephilic region-free DVD culture often positions itself as a refusal of the industrial (read: Hollywood) logics imposed by region codes. Here, a distaste for Hollywood mass culture blends with a like-minded rejection of corporate industry practices. In a published letter from 2003 that also speaks to the cinephilic and auteurist inclinations of region-free culture, Rosenbaum says: “It’s pretty easy to buy a tristandard VCR in Europe, but to get one in Chicago I had to order it from New York—a media equipment outlet that Jim Jarmusch sent me the catalogue for. It’s much easier to find DVD players in the US that can accommodate all the territories. Of course, this drives the Jack Valentis of the world nuts, because the rights to certain films are supposed to be territorialized along with their access—which is presumably why I had to buy my DVD of Johnny Guitar in Paris.”68 Rosenbaum’s writing reflects a cinephile’s orientation to film through not only the reference to Nicholas Ray’s 1954 cult classic Johnny Guitar but also in his espoused friendship with indie director Jarmusch. It marries a film-loving mind-set to a vision of critics and independent filmmakers traversing the world, angering the arbiters of Hollywood’s intellectual property. This taps into a broader understanding of unauthorized media access as a violation of Hollywood hegemony, which is also apparent in the hacker and pirate cultures that occasionally overlap cinephilia communities. Kim Dotcom, the eccentric founder of the file-hosting platforms Megaupload and Mega, crystallized this argument in a tweet mocking the Motion Picture Association of America (the Hollywood studios’ trade group and lobbying arm, of which Jack Valenti, mentioned by Rosenbaum, was president from 1966 to 2004).69 Dotcom frames regional lockout as an injustice against consumers that had foolishly been put in place due to the misconceived priorities of Hollywood’s primary governing body. In response, he presents measures undertaken to circumvent regional lockout—even file sharing and piracy—as natural responses to an unjust system.

Figure 5.2. Kim Dotcom mocks Hollywood. Screenshot: Dotcom, “MPAA.”

Gendering Region-Free DVD

Region-free media thus serves as an unlikely meeting point for diasporic groups, cultist popular culture fans, globally oriented cinephiles, and libertarian digital freedom advocates. As a result, its heterogeneity highlights power dynamics more complex than simple resistance. For one thing, many (though by no means all) cinephiles looking for region-free media hail from North America and Europe. Indeed, while it carries romantic overtones, cinephilia remains in tension between cosmopolitan engagement in global cultures (a zeal for global difference that Ethan Zuckerman calls “xenophilia”) and a commodifying impulse that sees international films and filmmakers as collectibles.70 This orientation to global media culture comes from a place of privilege, made easier if one lives in an area of the world with a significant amount of geocultural capital. Indeed, geocultural capital is symbolized in part by the degree to which people have access to media culture from across borders.

Other related dimensions of cultural power are at play here. In particular, it will not surprise anyone who read chapter 2 that region-free media culture shows up in media practices that are often aligned with masculinity. Namely, region-free media is gendered as an extension of often-masculinized cultures of cinephile film criticism.71 This moves beyond the traditional trope of travel-as-masculine and into the question of how cosmopolitans treat and comprehend other cultures. As Anna Tsing has argued, many nominally cosmopolitan projects in fact “enlarge the hegemonies of Northern centers even as they incorporate peripheries.”72 One of these hegemonies is that of dominant masculinity, and self-described cosmopolitans can incorporate peripheries in ways that flatten and minimize fine-grained cultural specificities and Orientalize the global Other. Although the two forms of informal trade are very different in obvious ways, we can nevertheless find an analogue to this gendering of global travel and consumption in Felicity Schaeffer-Grabiel’s work on the cyberbride industry. Here, Schaeffer-Grabiel observes a particular “transnational masculinity” that does not rely on a simplistic white-Other binary but rather tries on a kind of colonialism presented in the guise of “corporate multiculturalism.”73 It goes without saying that even the most commoditizing DVD collector mind-set is not in the same league as cyberbride purchasing vis-à-vis the issue of human exploitation. However, region-free media culture occasionally embodies similarly contradictory ideals of colonial knowledge/control and cosmopolitan multiculturalism. Indeed, such dynamics are apparent in how the diasporic storeowners I interviewed talk about the white consumers who enter the stores looking for Bollywood films to purchase along with their spices.

Region-free media’s blend of global consumption and technical mastery reflects two phenomena often represented in masculine terms: global travel/consumption and control of digital technologies. In the transnational distribution networks of region-free media technologies, as well as the accompanying knowledge-sharing networks surrounding technological “how-tos” and hacks for lockout circumvention, the body of the consumer, hacker, or instructor is often gendered male. Part of this builds on a long-standing home video culture that, as Ann Gray has shown, is gendered along lines of masculine control over the viewing space and experience.74 Years later, these same expressions of dominance manifest in talk about region-free DVD players as crucial to a high-quality home theater. Indeed, the ability to bypass regional lockout systems embodies these twin masculine ideals of mastery over technology and the ability to maintain control over time and space. Barbara Klinger refers to this as a mode of “contemporary high-end film collecting” that expresses a “white male technocratic ethos” from which women and people of color are often excluded.75 Because region-free DVD and Blu-ray players actually go above and beyond the usual affordances of the media equipment found in the average home, they are the perfect adornments for the top-of-the-line home theaters that help constitute a certain mode of contemporary Western masculinity.

Bookending chapter 1’s argument that region codes were systems of representation that expressed global inequalities, we can consider how advertisements, message board chatter, and other forms of discourse represent region-free DVD’s normative user. These often invoke the “man cave”—that is, a domestic space such as a garage, den, or home theater where no women are allowed—as an appropriate space for one’s region-free player, indicating that such technology belongs in a men-only space. Indeed, references to man caves pop up on websites and message boards devoted to cult film viewing that also regularly promote region-free DVD use. One typical poster on the message board Geekzone includes as his signature a list of the technology he keeps in his “man cave” (including a region-free Blu-ray player) and another post on the AV forum VideoHelp asks about hacking a region-coded DVD player that is also a piece of Star Wars merchandise: “I already have several region free DVD players—but it’s not about being able to play my R4 DVDs . . . it’s about being able to play my R4 sci-fi dvd’s in my ‘Man Cave’ on my R2-D2 DVD projector.”76 Across a number of message boards and blogs relating to film fandom and AV technology, similar examples abound of a relationship between region-free home video technologies and man cave home theater configurations. In the eyes of the men that want and build them, man caves and their AV setups serve as sanctuaries from a domestic space marked by femininity.77

In the context of region-free media, man caves (and gendered viewing more broadly) often align with cultist tastes.78 Although the oppositional stance of cultism might imply an upheaval of the traditional cinephile’s canon, it in fact overlaps with it. After all, the auteurism of the 1950s and 1960s that helped spur on the kind of cinephilia described in the above section was an ancestor of cultism.79 The relationship between this axis of auteurism/cultism/cinephilia and a kind of masculinized engagement with region-free media is exemplified by a YouTube unboxing video for a region-free 3D Blu-ray player by a user who, incidentally, also hosts a livestreamed online video program called The Sausage Factory, billed as a “movie discussion show, featuring a group of opinionated guys who watch WAY too many movies.”80 The video incorporates several signifiers of masculine cultist film fandom: the host makes a show of unboxing the player with his “trusty Joker knife,” a switchblade modeled after the knife used by the Joker in Christopher Nolan’s 2008 film The Dark Knight, then explains that he purchased the player specifically to watch region-coded discs from Arrow Video, a UK-based distributor that specializes in cult and horror films. He also connects this fandom to transnational film-sharing networks, showing off the player’s playback of a Scandinavian Blu-ray of Tobe Hooper’s 1974 horror classic The Texas Chainsaw Massacre that he received from a friend in Sweden. Region-free culture, here, manifests as masculinist totems of fandom and boasts of technological acumen and knowledge of global film movements.

Region-free media, however, is not exclusive to this kind of cultist, auteurist, cinephilia. It also exists in contemporary television fandoms—and occasionally those that focus their energies on “quality” television and new media platforms such as Hulu and Netflix. In an example that expresses a somewhat different relationship to media taste, an Australian blog called The Real Man’s Guide to Absolutely Everything published a post titled “How to Bypass Geo-Blocking in Australia.” Instructing the reader on how to set up a home theater PC and use VPN services to circumvent geoblocks, the article is illustrated with a blood-dripped image of Kevin Spacey as House of Cards’ Frank Underwood, an archetypical male antihero (and a picture suffused with toxic masculinity even before Spacey became an avatar of Hollywood’s culture of sexual abuse). In aligning the presumed male reader (this is The Real Man’s Guide, after all) with a male protagonist known for illegal and surreptitious acts, the article promotes the subversive thrill of hacking technological regulation. This aligns the circumvention of geoblocking and the promotion of platforms like Netflix with what Michael Newman and Elana Levine have called the discursive “legitimation” of television as a higher art form. Key to this is not only a vaunting of “complex,” masculinity-driven narratives but also an articulation of television and interactive digital technologies which promote a “masculinization of television as a newly active experience of mediated leisure” that contrasts against the medium’s feminized history.81 The rest of the article bears out the masculine address, invoking the man cave (if not by name) with references to setting up a home theater in the “lounge room” and a suggestion that one can also use his home theater PC to access the gaming platform Steam or watch pornography.82 Along with the clearly masculinized invocation of porn, mentioning Steam as a potential component of the man cave recalls the gendered dimension of hardcore gamer culture discussed in chapter 2.

It is no wonder that many of the most visible protests against region coding emerge from these masculinized spaces. In global power networks that, quite simply, do not value the voices of women, people of color, and diasporic populations as much, issues that affect those who hold global power and capital are more likely to be taken up as causes for concern. This is why public debates over regional lockout and geoblocking tend to focus on the problem of not accessing major streaming platforms in a country like Australia rather than the need to ensure that immigrant viewers are less disadvantaged in the global media marketplace. For one, in the eyes of many, the former issue is harder to criticize and dismiss than the informal economies of the latter, which are more easily pathologized and dismissed as “piracy.” In addition to the traditional motivators of xenophobia and ethnocentrism, though, this is the case because those who hold more cultural power (i.e., Western white men) are perceived as being able to affect change through their wallets. When so much of the discourse about reforming regional lockout exists at the level of consumers’ rights, economic and market-based incentives for reform suppress those based on eliminating cultural discrimination. That is, consumers’ rights groups and anti-copyright activists are more likely to gain the attention of major regulators and industrial players by appealing to problems they can relate to more easily, such as lacking access to a major platform like Netflix rather than a particular Nollywood video. When criticisms of industry and regulatory practices appeal only to the most powerful, the discursive terrain of regional lockout and its circumvention becomes doubly discriminatory. It reflects the valuation of certain kinds of consumption and circumvention practices over others and ensures that even regional lockout circumvention will align with cultural power.

Still, if this chapter has been critical of how region-free media have at times been incorporated into masculinized forms of media practice, I want to end by emphasizing how regional lockout circumvention negotiates and rejects the wills of dominant media-industrial power. There is a distinction between the ways region-free DVD cultures can be presented in terms that would presume a Western, masculine user and the actual, everyday experiences of lockout circumvention, which circulate among more diverse groups of media users. The dominant gendered representations of media and technology use do not always align with who actually uses media and how they use it (indeed, this is part of what can make these discourses so damaging to broader participation in media culture). In other words, I want to avoid reifying the trope of the young, white, Western, male, tech-head cinephile as the only figure that engages in region-free media. For one, the first half of this chapter cataloged region-free media use by communities who do not represent dominant global powers. However, there are other examples that more clearly contradict the masculine tenor of much of what I have described in this section. For instance, in a study of Japanese women viewing the Korean serial drama Winter Sonata, Yoshitaka Mōri points out that most of them “use media technology adeptly to gather information.” Such media technologies include online streaming services, language translators, and region-free DVD players.83 Lawrence Eng points out that otaku culture—long marked by regional circumvention practices—contains many women who buck the media industries’ preferred demographics.84 Christine Becker has also remarked that unauthorized access to the BBC iPlayer, discussed in chapter 3, is a common practice among fans of Sherlock, a predominantly female group of viewers.85 One could add non-UK-based fans of British soaps like EastEnders to the mix, and on and on. Just because many of the viewing subcultures involved in circumvention have centered the experiences and wishes of men does not mean that the actual practices of circumvention are not more inclusive.

Long-deferred hopes for regional lockout’s disappearance likewise emanate from diverse groups of people. As the conclusion for Locked Out shows, calls for the end of geoblocking arise from a variety of global sites, even if they ultimately represent dreams of a truly borderless internet that likely will not—and cannot—exist. Regional lockout animates a desire in users for a more open media environment, a desire often echoed—cynically or not—by tech companies promoting their own visions of an open worldwide marketplace. Thus, discussions about the end of geoblocking represent a complex blend of desires for pop-cosmopolitan consumption, free-trade global capitalism, and tech-libertarian digital freedom. Where these negotiations can become particularly progressive is through the promotion of media practices and literacies that value engagement with media from other parts of the world. Thus, the book ends with a brief exploration of the “end of geoblocking” discourse as well as how media research and education might take up region-free media in order to promote a broader diversity of global media.