V: CAMPAIGN FOR PRESIDENT,

JUNE-NOVEMBER 2008

The general election campaign set Obama’s call for change against John McCain’s pledge to continue the policies of the Bush administration with respect to deregulation, tax cuts, and the war in Iraq. Obama led at the outset, fell behind after Alaska Governor Sarah Palin was nominated for Vice President at the end of August, then pulled ahead for good when the economy nosedived in the middle of September. A steady and disciplined campaign, continued Internet-based fund raising success, and strong turnout by his supporters ensured his historic victory in November.

June and July were all Obama. The candidate led national polls by about six points and had a convincing margin in electoral college projections. The constitution stipulates that each state get one electoral vote for each Representative and one for each Senator: 535, plus three for the District of Columbia, for a total of 538. Thus, 270 are required to be elected President. Every state, except Maine and Nebraska, uses a “winner-take-all” system that grants all of its electors to whichever candidate gets the most votes. Presidential campaigns thus focus their efforts on “swing” states, where polls show support is split and the final vote could go either way, to the exclusion of states where the outcome seems clear.

The Obama campaign worked feverishly, despite their lead, to prepare for the coming contest. On 12 June the web team launched FightTheSmears.com to centralize responses to future attacks. In the same month, volunteer coordinators recruited, trained and deployed 3,600 “Obama Organizing Fellows,” each of whom had offered to work full-time for six weeks for free, to 17 swing states in what it called the largest grass-roots organizing effort in U.S. electoral history. Donors contributed $52 million in June, one of the Illinois senator’s best months ever and more than double the $22 million raised by McCain.

The dynamic changed at the end of July when Obama made a whirlwind four-day tour of Kuwait, Afghanistan, Iraq, Jordan, the West Bank, Israel, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. He capped the trip with a speech in Berlin to an estimated 200,000 cheering Germans.

The expedition initially seemed like a good idea. Obama had been to Iraq only once, and had never been to Afghanistan. McCain had criticized him for this parochialism, and sardonically offered to escort him to Kabul. In a Washington Post-ABC News poll released on 18 July, 72 percent of respondents said McCain knew enough about world affairs to be an effective president, compared to just 54 percent for Obama. The trip promised enormous coverage: dozens of top newspaper reporters and three of the network news anchors accompanied the frontrunner.

In practice, however, the overseas voyage created an opening for McCain. The Berlin crowd was the largest of the campaign. “People of Berlin—people of the world—this is our moment. This is our time,” Obama said. McCain’s reply was an ad released in Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin the following week that began, “He’s the biggest celebrity in the world.” The screen showed the Berlin rally, followed by images of Britney Spears and Paris Hilton. “But, is he ready to lead?” the voice-over continued. “With gas prices soaring, Barack Obama says no to offshore drilling. And, says he’ll raise taxes on electricity. Higher taxes, more foreign oil, that’s the real Obama,” the spot concluded. Watchdog groups said the ad was false because Obama had not said he would raise taxes on electricity, but the idea of Obama as an immature egotist was planted. McCain hit the same theme when he hammered Obama for what he called a tentative response to an incursion into U.S. ally Georgia by Russia. Obama’s poll numbers started to decline. McCain’s rose.

The media attention Obama received, it emerged, was not always flattering. The Illinois senator got more than twice as much coverage on the CBS, ABC and NBC evening newscasts as his Arizona rival from mid-June to the end of July, analyst Andrew Tyndall reported—but it was more negative. A study by the Center for Media and Public Affairs at George Mason University found that when network newscasters ventured opinions during this period, 28 percent were positive for Obama and 72 percent were negative; by contrast, 43 percent of opinions were positive for McCain and 57 percent negative. A response to the “Celebrity” ad by Paris Hilton on 5 August in which she attacked “wrinkly, white-haired guy” McCain, “the oldest celebrity in the world”—“old enough to remember when dancing was a sin and beer was served in a bucket”—and declared her own candidacy for president (“I’m just hot”) did little to change opinions.

The critical news coverage and negative advertisements coincided with the release of two nationwide bestsellers that were harshly critical of Obama. Jerome Corsi’s The Obama Nation: Leftist Politics and the Cult of Personality, an intentional play on the word “abomination,” jumped to number one on the New York Times bestseller list, boosted by bulk purchases, on 1 August. The book alleged that Obama was corrupt, driven by “black rage,” and possibly Muslim, among other charges. Corsi authored a similarly provocative attack against John Kerry called Unfit for Command in 2004 that received wide publicity and was perceived to have contributed to his defeat.

The Case Against Barack Obama: The Unlikely Rise and Un-examined Agenda of the Media’s Favorite Candidate by David Freddoso, a reporter for the conservative National Review Online website, debuted on 4 August at number five on the New York Times bestseller list. Its ranking also was helped by bulk purchases. Freddoso alleged that Obama supported de facto infanticide because he voted against “Born Alive” bills in the Illinois state senate from 2001 to 2003; used his clout as a U.S. Senator to help save “the corrupt Cook County Political Machine;” and had repeatedly steered taxpayer money to campaign donors, among other charges.

The Obama campaign responded on 15 August with both old and new techniques. First, a spokesperson commented, “These books are cut from the same cloth, made up of the same old debunked smears that have been floating around the Internet for months.” Second, the campaign posted Unfit for Publication, a 22,000 word reply to Corsi’s book packed with scathing reviews, detailed refutations of specific points, and background information about the author intended to undermine his credibility, on FightTheSmears.com. The title was a play on the author’s 2004 book. Traditional media was interested in the point-counterpoint. They wrote some 1,060 stories about The Obama Nation, and cited Unfit for Publication about 670 times. Blogs were obsessed: they posted about 5,820 stories that cited the book, and 2,464 pieces that noted the campaign’s rebuttal.

The attacks were effective. Obama’s support fell at the beginning of August and remained flat through the middle of the month. McCain’s popularity rose. Polls released just before the Democratic convention in Denver showed the frontrunner’s lead had been cut in half, to about three percent nationwide.

The convention began unofficially on 23 August when Obama declared that Delaware Senator Joe Biden, a 3 year Congressional veteran with extensive foreign policy experience, would be his running mate. The news was released through a text message to supporters. The gimmick made a political point about new possibilities for direct communication, created additional media interest in the story, and allowed the campaign to collect mobile telephone numbers. Biden, “brings extensive foreign policy experience, an impressive record of collaborating across party lines, and a direct approach to getting the job done,” Obama said. The choice of the veteran senator, a Catholic who grew up in the swing state of Pennsylvania, was seen as savvy and judicious by many. The McCain campaign, however, trumpeted criticisms of Obama made by Biden during the primary campaign. “Biden has denounced Barack Obama’s poor foreign policy judgment and has strongly argued in his own words what Americans are quickly realizing—that Barack Obama is not ready to be President,” a spokesman said.

The keynote speeches at the convention stressed themes of reconciliation and unity and attacked McCain as a continuation of the Bush-Cheney government. Michelle Obama made the first major address on 25 August. “He’ll achieve these goals the same way he always has,” she said of her husband. “By bringing us together and reminding us how much we share and how alike we really are. You see, Barack doesn’t care where you’re from, or what your background is, or what party—if any—you belong to. That’s not how he sees the world. He knows that thread that connects us—our belief in America’s promise, our commitment to our children’s future. He knows that that thread is strong enough to hold us together as one nation even when we disagree,” she added.

Senator Clinton spoke the next night. She laid to rest any concern that she might not wholeheartedly support Obama after the grueling primary contest—a subject of fevered speculation in the media. “No way, no how, no McCain,” she began. She made an adroit reference to the historical nature of her candidacy as a woman, and her legions of female supporters: “To my supporters, my champions—my sisterhood of the traveling pantsuits—from the bottom of my heart: Thank you.” Finally, she tied Senator McCain to the deeply unpopular Bush administration—and linked Obama to the best accomplishments of her husband’s presidency: “But we don’t need four more years … of the last eight years…. When Barack Obama is in the White House, he’ll revitalize our economy, defend the working people of America, and meet the global challenges of our time. Democrats know how to do this. As I recall, President Clinton and the Democrats did it before. And President Obama and the Democrats will do it again,” she said. Former President Clinton echoed these themes the next night. “He has a remarkable ability to inspire people, to raise our hopes and rally us to high purpose. He has the intelligence and curiosity every successful president needs,” he said of Obama. Finally, on the last night of the convention, Obama accepted the party’s nomination before a thunderous crowd of 84,000 at Denver’s Mile High Stadium. He tied McCain to Bush; attacked him for excessive devotion to individualism in contrast to his own affirmation of community; reviewed a list of policy specifics; and closed with a call for rededication to individual and collective responsibilities. “The record’s clear: John McCain has voted with George Bush ninety percent of the time. Senator McCain likes to talk about judgment, but really, what does it say about your judgment when you think George Bush has been right more than ninety percent of the time? I don’t know about you, but I’m not ready to take a ten percent chance on change,” he said.

“For over two decades, he’s subscribed to that old, discredited Republican philosophy—give more and more to those with the most and hope that prosperity trickles down to everyone else. In Washington, they call this the Ownership Society, but what it really means is—you’re on your own. Out of work? Tough luck. No health care? The market will fix it. Born into poverty? Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps—even if you don’t have boots. You’re on your own,” he continued. By contrast, he said, the promise of America is, “The idea that we are responsible for ourselves, but that we also rise or fall as one nation; the fundamental belief that I am my brother’s keeper; I am my sister’s keeper.”

“America, now is not the time for small plans,” Obama said, as he outlined his proposals for reform of virtually every sector of the economy, from energy to education and health care to Social Security.

Finally, he said, “We must also admit that fulfilling America’s promise will require more than just money It will require a renewed sense of responsibility from each of us to recover what John F. Kennedy called our ‘intellectual and moral strength.’ Yes, government must lead on energy independence, but each of us must do our part to make our homes and businesses more efficient. Yes, we must provide more ladders to success for young men who fall into lives of crime and despair. But we must also admit that programs alone can’t replace parents; that government can’t turn off the television and make a child do her homework; that fathers must take more responsibility for providing the love and guidance their children need. Individual responsibility and mutual responsibility—that’s the essence of America’s promise,” he concluded.

The next day John McCain dropped a bombshell that tore the country’s attention away from Obama and gave the Republican the lead for the first time: he selected Sarah Palin, the relatively unknown 44-year-old governor of Alaska for two years, as his running mate. Palin’s only significant government experience before becoming governor had been as Mayor of the town of Wasilla, population about 5,500 at the time, for six years, and a member of its city council for four years before that. “She’s not from these parts, and she’s not from Washington, but when you get to know her, you’re going to be as impressed as I am,” McCain told 15,000 people in a basketball arena in Dayton, Ohio when he made the announcement.

Republicans initially applauded the selection. Palin was an evangelical Christian, hunter, happily married wife and mother of five, and the first woman nominee for Vice President in party history. Enthusiasm spread after her speech to a television audience estimated at 37 million—nearly as many as tuned in for Obama’s acceptance speech—at the Republican convention in St. Paul, Minnesota the following week.

She was, she said, a hockey mom: “You know [what], they say the difference [is] between a hockey mom and a pit bull? Lipstick.” She mocked Obama and the news media. “I guess a small-town mayor is sort of like a community organizer, except that you have actual responsibilities,” she said. “Here’s a little newsflash for those reporters and commentators: I’m not going to Washington to seek their good opinion. I’m going to Washington to serve the people of this great country,” she added. She praised people from small towns: “I grew up with those people. They’re the ones who do some of the hardest work in America, who grow our food, and run our factories, and fight our wars. They love their country in good times and bad, and they’re always proud of America.” She proposed new drilling for oil and gas to chants of “Drill, baby, drill!” and a renewed commitment to the Iraq war; promised lower taxes and spending; and presented her administration as defined by simple tastes and frugality. “I got rid of a few things in the governor’s office that I didn’t believe our citizens should have to pay for. That luxury jet was over-the-top. I put it on eBay” she said. “I told the Congress, Thanks, but no thanks,’ on that Bridge to Nowhere,” she added, referring to a plan to build a $398 million bridge with federal funds to an island with population of 50 full-time residents and a small airport. “This lady has turned it all around … from now on, on this program John McCain will be known as John McBrilliant,” conservative radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh said the next day.

McCain continued the themes of lower taxes and spending, more drilling, and an unwavering commitment to the war in Iraq when he accepted the nomination the next night. “I will cut government spending. He will increase it. My tax cuts will create jobs; his tax increases will eliminate them,” he said. “We will drill new wells off-shore, and we’ll drill them now,” he continued. “I’ve fought for the right strategy and more troops in Iraq when it wasn’t the popular thing to do…. I’d rather lose an election than see my country lose,” he declared. Finally, he stressed his experience. “I have that record and the scars to prove it. Senator Obama does not,” he said.

The speeches resonated. Support for Obama in averages of multiple national polls peaked at around 47 percent at the end of August just before the Democratic convention, stayed flat though the end of the month, then dropped during and immediately after the Republican confab to about 45 percent. Enthusiasm for McCain jumped from about 44 percent at the end of August to about 46 percent in the first week of September.

The Republican surge was short-lived. On 7 September Fannie Mae, the Federal National Mortgage Association, and Freddie Mac, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, private firms supported by an implicit government guarantee that underwrote many of the nation’s home mortgages, became insolvent and were taken over by the government. On 14 September the Wall Street investment bank Lehman Brothers declared the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history. Its debts were larger than the gross domestic product of Poland. On the same day, Bank of America acquired brokerage firm Merrill Lynch in a forced sale brokered by the government. Thousands of jobs were lost. Commentators compared the crisis to the Depression of the 1930s. The polls reversed almost immediately: Obama’s numbers began to rise, and McCain’s to fall.

McCain’s first public response to the economic crisis was a speech in Jacksonville Florida on 15 September at which he said, “The fundamentals of our economy are strong.” Obama responded immediately: “It’s not that I think John McCain doesn’t care [about] what’s going on in the lives of most Americans. I just think he doesn’t know. Why else would he say, today, of all days, just a few hours ago, that the fundamentals of our economy are strong? Senator, what economy are you talking about?” McCain later claimed that by “fundamentals” he meant American workers.

The crisis continued to worsen in the third week of September, just six weeks from election day. On the 24th, McCain said he had suspended his campaign, asked Obama to postpone the first debate scheduled for three days later, and flew to Washington, D.C. to help negotiate a $700 billion financial rescue plan proposed by Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. Obama refused to delay the debate. “It’s my belief that this is exactly the time when the American people need to hear from the person who will be the next president,” he said. “It is going to be part of the president’s job to deal with more than one thing at once,” he added. On Thursday the 25th, Washington Mutual Savings Bank collapsed—the largest bank failure in U.S. history—and a White House meeting between President Bush and Republican and Democratic leaders, including Obama and McCain, to discuss Paulson’s proposal broke up in acrimony. The breakdown of discussions, despite McCain’s high-profile rush back to the capital, combined with the fact that his campaign kept its offices open and continued to advertise during the “suspension” made the senator and his team appear hapless and erratic. Obama, by contrast, was unflappable in interviews. His campaign conducted business as usual.

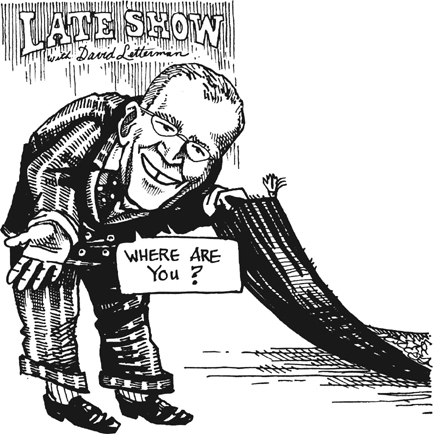

McCain’s campaign was damaged by two additional setbacks during the week. On the 23rd, it emerged that Freddie Mac paid $15,000 a month from the end of 2005 through August 2008—the total was ultimately shown to be more than $2 million—to a lobbying firm owned by McCain campaign manager Rick Davis. The next day McCain’s staff, perhaps confused by the sudden “suspension” announcement, double-booked the candidate for appearances on CBS News with Katie Couric and The Late Show with David Letterman. McCain, a frequent guest on Letterman’s show, cancelled with apologies that he had to return immediately to Washington. Shortly thereafter, however, the talk show host’s staff observed him on a live satellite feed from the CBS studios, a few blocks from their own building in Manhattan, getting ready to appear on Couric’s program. Letterman relayed the CBS feed live on his program and unleashed a torrent of invective. “You don’t suspend your campaign. This doesn’t smell right. This isn’t the way a tested hero behaves … I think someone’s putting something in his Metamucil,” he said. He pummeled McCain relentlessly through November.

The first presidential debate, focused on foreign policy and national security, took place on 27 September at the University of Mississippi. Discussion quickly turned to the economic crisis: a global matter that affected security Obama was decisive. “This is a final verdict on eight years of failed economic policies—promoted by George Bush, supported by Sen. McCain … a theory that basically says that we can shred regulations and consumer protections and give more and more to the most, and somehow, prosperity will trickle down,” he said, in an echo of his convention acceptance speech. “It hasn’t worked,” he continued, “and I think that the fundamentals of the economy have to be measured by whether or not the middle class is getting a fair shake. That’s why I’m running for president.” McCain responded that if he were elected president he would focus first on elimination of pork barrel spending. “I’ve got a pen and I’m going to veto every spending bill that comes across my desk,” he said. In fact, however, as commenters quickly noted, pork barrel projects, while problematic, were a tiny fraction of the overall budget and were not believed to have played a significant role in the crisis.

Obama also attacked on the subject of Iraq. “We’ve spent over $600 billion so far, soon to be $1 trillion,” Obama said. “We have lost over 4,000 lives. We have seen 30,000 wounded, and most importantly, from a strategic national security perspective, al Qaeda is resurgent, stronger now than at any time since 2001.” “We took our eye off the ball,” he added, “and not to mention that we are still spending $10 billion a month when they [Iraqis] have a $79 billion surplus, at a time when we are in great distress here at home.” A national poll of viewers by CNN immediately after the event judged Obama the winner 51 percent to 38 percent.

The House rejected Paulson’s plan two days later by a vote of 228–205. Republicans led the opposition and voted 133–65 against the plan. Democrats voted 140–95 in favor. The Dow Industrial Average stock index fell 777 points in response: its worst single-day drop in two decades. McCain’s poll numbers declined in lock step.

Palin’s appeal also was in decline. First, her convention speech claims that she put the state plane “on eBay,” and said “Thanks, but no thanks,” to the federal government about the “Bridge to Nowhere,” did not withstand scrutiny. The jet was listed on eBay but didn’t sell. The state finally sold it to a local businessman at a loss of almost $600,000. The record also showed that she actually supported the “Bridge to Nowhere,” and its pork-barrel federal financing, during her 2006 run for governor.

Second, interviews with ABC News anchor Charlie Gibson on 11 September and CBS News anchor Katie Couric on 24 September raised questions about her preparation to be chief executive. In her interview with Gibson, she asserted that Russia’s proximity to Alaska—“You can actually see Russia from land here in Alaska,”—gave her insight into bilateral relations. She also appeared not to know what the Bush Doctrine was (the doctrine, announced after the 9/11 attacks, asserted that the U.S. could attack other countries preemptively to protect itself). In her interview with Couric, her answer to a question about Paulson’s debt relief plan suggested she didn’t fully understand the issue. “I’m all about the position that America is in and that we have to look at a $700 billion bailout. And as Sen. McCain has said unless this nearly trillion dollar bailout is what it may end up to be, unless there are amendments in Paulson’s proposal, really I don’t believe that Americans are going to support this and we will not support this,” she said. She insisted that McCain had long supported additional regulation of the financial system, but couldn’t cite any examples. “I’ll try to find you some and I’ll bring them to you,” she told the journalist.

The Vice-Presidential debate on 2 October generated enormous interest—over 70 million people watched, far more than tuned in to the presidential debate—but did not help Palin. Post-debate polling deemed Biden the winner 51 percent to 36 percent. Mainstream conservatives were harsh in their criticisms. “If BS were currency, Palin could bail out Wall Street herself,” Kathleen Parker wrote in the National Review Online. Her anti-intellectualism is “a fatal cancer to the Republican party,” said New York Times columnist David Brooks. “What on earth can he have been thinking?” Christopher Buckley wondered of McCain.

As the race entered its final month, Obama’s lead in national polls had widened to about seven points. This matched the largest margin of the campaign and returned the race to where it had been in mid-July Projections showed the Democrat well ahead in the electoral college. Particularly worrisome for the McCain campaign was the fact that their numbers had been in decline since their convention. They sharpened their attack. Palin led the charge. At a rally on 5 October she cited Bill Ayers and described Obama as “someone who sees America, it seems, as being so imperfect that he’s palling around with terrorists who would target their own country.” She repeated the incendiary allegation at subsequent events. Supporters responded. Videos of Palin’s subsequent rallies posted on YouTube recorded shouts of “Treason!,” “Off with his head!,” “He is a bomb!” and, in one instance, “Kill him,” although it was not clear if the comment was aimed at Obama or at Ayers. The governor, although she paused on occasion, did not challenge the statements. She later called the threats “atrocious and unacceptable,” and said she hadn’t heard them.

The second presidential debate continued the focus of the first on economic issues. McCain announced a new proposal to spend $300 billion to buy back bad mortgages from banks—but was vague about the details. His eyes were red and he looked tired. He appeared unwilling to look directly at his opponent and, toward the end of the contest, referred to him awkwardly as “that one.” Obama offered no new proposals, but seemed at ease and collected. CNN’s post-event survey scored the exchange 54 percent for Obama to 30 percent for McCain.

Criticism of Palin mounted on 10 October when a bipartisan panel formed by the Alaska legislature to investigate a controversy dubbed Troopergate concluded she “unlawfully abused her power as governor by trying to have her former brother-in-law fired as a state trooper.” The governor herself, however, categorically dismissed the finding. “Well, I’m very, very pleased to be cleared of any legal wrongdoing … any hint of any kind of unethical activity there,” she said.

Perhaps mindful of the Troopergate report, or concerned by information from the Secret Service about an increase in threats to Obama in September and early October, McCain signaled the same day that he wanted to scale back the attacks. “If you want a fight, we will fight,” he said at a rally in Minnesota. “But we will be respectful. I admire Senator Obama and his accomplishments. I will respect him, and I want—no, no,” McCain said over boos, “I want everyone to be respectful.” The candidate corrected a woman who said Obama was “an Arab.” “No. No, ma’am. No, ma’am. No, ma’am. No, ma’am,” McCain said, “He’s a decent family man, a citizen, that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues; that’s what this campaign is about.” It later emerged that McCain had decided at the beginning of the campaign to avoid attacks based on the Reverend Wright, Michelle Obama, or Obama’s lack of military service.

Ayers and the community group ACORN, however, were considered worthy subjects for discussion. McCain made them a central focus of his argument in the final debate on 15 October. “We need to know the full extent of that [Ayers] relationship. We need to know the full extent of Sen. Obama’s relationship with ACORN, who is now on the verge of maybe perpetrating one of the greatest frauds in voter history in this country, maybe destroying the fabric of democracy,” the Arizona senator said. Obama countered, “Mr. Ayers has become the centerpiece of McCain’s campaign. Let’s get the record straight. Ayers is a professor of education in Chicago. Forty years ago, when I was eight years old, he engaged in despicable acts. I have roundly condemned those acts.” He served on a board with Ayers, he added—along with a former ambassador and the presidents of the University of Illinois and Northwestern University. His only involvement with ACORN, he said, was to help represent them “alongside the U.S. Justice Department” to force Illinois to implement a law to allow people to register to vote at Department of Motor Vehicles offices. McCain also spent a considerable period of time discussing a man he dubbed “Joe the Plumber” who had confronted Obama while the candidate campaigned in Toledo, Ohio the week before. “Joe wants to buy the business that he has been in for all of these years, worked 10, 12 hours a day. And he wanted to buy the business but he looked at your tax plan and he saw that he was going to pay much higher taxes,” McCain said. Obama repied, “I think tax policy is a major difference between Senator McCain and myself. And we both want to cut taxes, the difference is who we want to cut taxes for. Now, Senator McCain, the centerpiece of his economic proposal is to provide $200 billion in additional tax breaks to some of the wealthiest corporations in America…. What I’ve said is I want to provide a tax cut for 95 percent of working Americans.” Viewers found Obama’s arguments more convincing: CNN’s post-debate survey scored the contest 58–31 for the Illinois senator, the widest margin of the three face-offs. McCain’s arguments was further undercut when it later emerged that Joe was not a licensed plumber, had a lien against him by the state of Ohio for unpaid taxes, and made so much less money than he claimed that he likely would have received a tax cut under Obama’s plan.

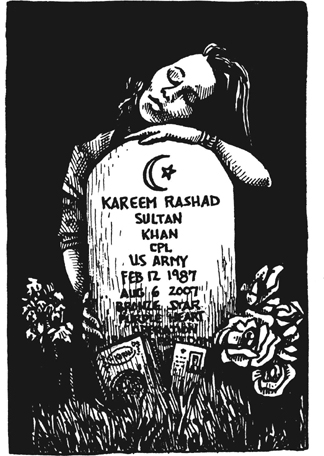

An air of inevitability began to surround Obama’s candidacy when retired General Colin Powell, a former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under President George H. W. Bush and Secretary of State for George W. Bush, and himself a possible Republican presidential candidate, endorsed him on 19 October. “I don’t believe [Palin] is ready to be president of the United States,” he said. Powell added he was “troubled” by the personal attacks on Obama, especially intimations he might be Muslim, because they were untrue and because there was no reason a Muslim-American shouldn’t seek the presidency. “Is there something wrong with being a Muslim in this country? The answer’s no, that’s not America,” he said. “I feel strongly about this particular point because of a picture I saw … of a mother in Arlington Cemetery, and she had her head on the headstone of her son’s grave…. it had [the] crescent and a star of the Islamic faith. And his name was Kareem Rashad Sultan Khan, and he was an American. He was born in New Jersey. He was 14 years old at the time of 9/11, and he waited until he can go serve his country, and he gave his life. Now, we have got to stop polarizing ourself in this way,” he continued. The focus on Ayers, he thought, was inappropriate given the scant contact between the candidate and the professor. Finally, he said he was concerned about McCain’s apparent lack of understanding about how to deal with economic problems. “I truly believe that at this point in America’s history we need a president who will not just continue … basically the policies we have followed in recent years,” Powell said. “We need a president with transformational qualities.”

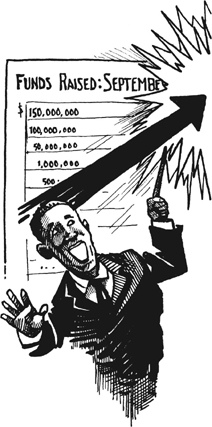

On the day of Powell’s endorsement, the Obama campaign announced it had added 632,000 new donors and raised over $150 million in September. The average donation for the month was less than $100. The total number of donors was now over three million people. On 23 October, NBC announced that Obama’s lead had grown to 52 to 42 percent, up from 49 to 43 percent two weeks before, and the largest margin of the campaign.

Bad news continued for McCain. The website Politico.com reported on 22 October that the Republican National Committee had spent over $150,000 on Palin’s wardrobe since her nomination, including between $20,000 and $40,000 on clothes for her husband. Low-level staffers had been required to use their credit cards to pay for some items. Palin’s representatives said many of the clothes had been purchased in multiple sizes. Unused garments had been returned. All of the items would be given to charity after the election, they said. The spending nonetheless appeared extravagant to many.

Polls now showed that Palin, despite her ability to draw large crowds of fervent supporters at rallies, had become McCain’s greatest liability. “Palin’s qualifications to be president rank as voters’ top concern about McCain’s candidacy—ahead of continuing President Bush’s policies, enacting economic policies that only benefit the rich and keeping too high of a troop presence in Iraq,” NBC reported. “For the first time, more voters have a negative opinion of her than a positive one,” the network added.

The campaign entered its endgame. Obama flew home to Hawaii to say farewell to his gravely ill grandmother from 23 to 25 October. On 29 October, his team bought a half-hour of prime air-time for an “Obama infomercial,” as he called it. The $4 million closing argument, the first time a presidential candidate had purchased a large block of network prime time since Ross Perot in 1992, told the stories of four voters, their families, and challenges they faced. Obama offered details about his housing, tax, energy and Iraq war policies in interludes between the documentaries. The promotion ended with live footage of the candidate at a late-night rally for 20,000 people at Sunrise, Florida. Nielsen reported 33.6 million people watched the program. Even later that night, Obama appeared for the first time with former president Bill Clinton at a rally of 35,000 people at Kissimmee, Florida.

The Obama campaign unleashed a barrage of advertising in the days leading up to 4 November, and a get out of the vote operation on Election Day unlike anything ever seen in U.S. politics. In addition to an avalanche of television commercials in swing states, the team’s efforts included a dedicated 24-hour satellite channel that showed nothing but speeches by Obama and promotions for him, commercials inserted in video games, and dozens of daily uploads to YouTube and other Internet distribution channels. The campaign mobilized tens of thousands of volunteers, coordinated by hundreds of field offices, to ensure that supporters—identified by painstaking door-to-door and telephone canvasses prior to Election Day—actually voted. An army of thousands of attorneys recruited by the campaign’s Counsel for Change voter protection program stood watch at polling places to ensure that every eligible supporter was allowed to vote.

The McCain campaign tried to match Obama’s effort. The Republicans countered the Democrat ad-for-ad in key battleground states such as Florida, Ohio, North Carolina, Virginia, and Pennsylvania in the last days of the race. It also mounted its own nationwide “72 hour program” in the days just before the election to get out the vote. The Republican National Committee reported 5.4 million voter contacts in the week before the election, although many were automated telephone “robo-calls” rather than personal visits, compared with 1.9 million in the same week in 2004. McCain appeared at 252 events in battleground states during the general election and Palin at 150, compared to 230 appearances for Obama and 107 for Biden.

In the final analysis, however, Obama’s outreach was significantly greater than McCain’s. The Democrat spent $593.1 million from the beginning of his primary campaign through 4 November, compared to $273.5 million for his rival. Obama ran about 370,000 television advertisements in the general election, compared to around 250,000 by McCain. The Republican National Committee spent $36 million for an additional approximately 71,000 spots, but the differential still was substantial. Reports from Ohio after the election gave an indication of the comparative reach of the campaigns: 53 percent of voters said they had been personally contacted by the Obama team, compared to 36 percent who reported similar contact from McCain’s campaign.

Election Day began auspiciously for Obama: he won the New Hampshire hamlets of Dixville Notch and Hart’s Location, the first places in the country to announce results, by votes of 15–6 and 17–10, respectively. The two candidates voted in their home states, then spent the day at last-minute rallies as their teams swung into action at polls across the country.

Pennsylvania was the first major battleground state to be called for Obama. When Ohio followed a bit later in the evening, the math was clear. It wasn’t until polls closed on the West Coast at 11:00 p.m. eastern time, however, that news organizations declared Obama victorious. Supporters spilled into the streets of major cities. They danced in Harlem, tooted horns in Boston, cheered in Chicago, rejoiced in Atlanta and sang in San Francisco and Seattle, among many other scenes of jubilation. More than 1,000 celebrants shouted “Yes we can!” outside the White House.

The first African American elected president received 66,882,230 votes, 53 percent of the total, to McCain’s 58,343,671 or 46 percent. He won 365 of 538 electoral votes. It was the biggest Democratic victory since Lyndon Johnson in 1964, the first time a Democrat had won more than half of all votes since Jimmy Carter in 1976, and the first time a Democrat won a majority of male voters since Bill Clinton in 1996.

Obama won states that for many years had been reliably Republican, including Indiana and Virginia, neither of which had voted for a Democrat for president since Johnson. He won 68 percent of new voters, two-thirds of voters aged 18 to 29, 95 percent of blacks, 66 percent of Latinos, 54 percent of Catholics and a majority of independents and the rich: voters with incomes over $200,000. He did not win a majority of white voters, or those aged 65 and older. A record 127.5 million people voted, about 61 percent of eligible voters. It was the largest turnout in history in absolute numbers, but almost unchanged in percentage terms from the previous election.

In a testament to the effectiveness of the Obama campaign’s get out the vote effort, Democratic turnout increased 2.6 points from 28.7 percent of voters in 2004 to 31.3 percent, while Republican turnout declined by 1.3 percentage points to 28.7 percent. The “blue,” or Democratic, shift was nationwide, except for a band of counties in the deep south and along the southern portion of the Appalachian mountains where a larger “red” percentage voted for McCain than had voted for Bush in 2004. Democrats gained significant numbers of seats in the House and Senate and took firm control of both houses.

McCain was gracious in his concession speech. Of Obama he said, “In a contest as long and difficult as this campaign has been, his success alone commands my respect for his ability and perseverance. But that he managed to do so by inspiring the hopes of so many millions of Americans who had once wrongly believed that they had little at stake or little influence in the election of an American president is something I deeply admire and commend him for achieving.” He continued, “This is an historic election, and I recognize the special significance it has for African Americans and for the special pride that must be theirs tonight…. A century ago, President Theodore Roosevelt’s invitation of Booker T. Washington to visit—to dine at the White House was taken as an outrage in many quarters. America today is a world away from the cruel and prideful bigotry of that time. There is no better evidence of this than the election of an African American to the presidency of the United States. Let there be no reason now for any American to fail to cherish their citizenship in this, the greatest nation on Earth.” He concluded, “I wish Godspeed to the man who was my former opponent and will be my president.” Palin arrived prepared to present her own address, even though it is not customary for a vice-presidential candidate to deliver a concession speech, but was not allowed to talk.

Obama strode onto an outdoor stage in Chicago’s Grant Park, named for the Union general who won the Civil War that ended slavery, just before midnight. An exultant crowd estimated at 240,000 cheered. His family joined him. “If there is anyone out there who still doubts that America is a place where all things are possible; who still wonders if the dream of our founders is alive in our time; who still questions the power of our democracy, tonight is your answer,” he said.

“It’s the answer told by lines that stretched around schools and churches in numbers this nation has never seen; by people who waited three hours and four hours, many for the very first time in their lives, because they believed that this time must be different; that their voice could be that difference. It’s the answer spoken by young and old, rich and poor, Democrat and Republican, black, white, Latino, Asian, Native American, gay, straight, disabled and not disabled—Americans who sent a message to the world that we have never been a collection of red states and blue states: we are, and always will be, the United States of America. It’s the answer that led those who have been told for so long by so many to be cynical, and fearful, and doubtful of what we can achieve, to put their hands on the arc of history and bend it once more toward the hope of a better day It’s been a long time coming, but tonight, because of what we did on this day, in this election, at this defining moment, change has come to America,” he continued.

The change that had happened, however, was only a chance, he said, for the change his campaign sought: “This victory alone is not the change we seek—it is only the chance for us to make that change. And that cannot happen if we go back to the way things were. It cannot happen without you…. The road ahead will be long. Our climb will be steep. We may not get there in one year or even one term, but America—I have never been more hopeful than I am tonight that we will get there. I promise you—we as a people will get there.”

He told the story of Ann Nixon Cooper, a 10 year-old woman born one generation after slavery who voted that day in Atlanta. “She was born just a generation past slavery; a time when there were no cars on the road or planes in the sky; when someone like her couldn’t vote for two reasons—because she was a woman and because of the color of her skin,” he said. “And tonight, I think about all that she’s seen throughout her century in America—the heartache and the hope; the struggle and the progress; the times we were told that we can’t, and the people who pressed on with that American creed: Yes we can. At a time when women’s voices were silenced and their hopes dismissed, she lived to see them stand up and speak out and reach for the ballot. Yes we can. When there was despair in the dust bowl and depression across the land, she saw a nation conquer fear itself with a New Deal, new jobs and a new sense of common purpose. Yes we can. When the bombs fell on our harbor and tyranny threatened the world, she was there to witness a generation rise to greatness and a democracy was saved. Yes we can. She was there for the buses in Montgomery, the hoses in Birmingham, a bridge in Selma, and a preacher from Atlanta who told a people that we shall overcome. Yes we can. A man touched down on the moon, a wall came down in Berlin, a world was connected by our own science and imagination. And this year, in this election, she touched her finger to a screen, and cast her vote, because after 106 years in America, through the best of times and the darkest of hours, she knows how America can change. Yes we can,” he continued.

To rolling roars of approval and tear-stained faces he thanked his campaign team (the best “ever assembled in the history of politics”), his parents and grandparents, brothers and sisters, his wife (“the nation’s next first lady”), and his daughters. “Sasha and Malia I love you both more than you can imagine. And you have earned the new puppy that’s coming with us to the new White House,” he said.

He concluded, “America, we have come so far. We have seen so much. But there is so much more to do. So tonight, let us ask ourselves—if our children should live to see the next century; if my daughters should be so lucky to live as long as Ann Nixon Cooper, what change will they see? What progress will we have made?”