19

The Pacification Program (1967–1968)

Failing to Change Behavior

While MACV’s main-force strategy and Rolling Thunder missions gained momentum between 1965 and 1968, until 1967 less emphasis was placed on counterinsurgency efforts to defeat the revolutionary movement in the countryside. There was a reason for this lack of attention: a COIN strategy had already failed in Vietnam in the early 1960s.

The US-supported GVN in the early 1960s had implemented the Strategic Hamlet Program, modeled after the British success in defeating the Malayan insurgency. Between 1948 and 1960, the British had fought a successful counterinsurgency campaign in Malaya against the Malayan Communist Party. Nagl describes the organizational and operational learning by the British army over the decade of the 1950s.1 Britain was able to employ all the elements of counterinsurgency—diplomacy, information operations, intelligence, financial control, and military power—“remarkably well in Malaya” to achieve the political objectives of establishing a stable national government by 1957 that could secure itself against internal and external threats.

The man selected to defeat the Malayan insurgency was General Sir Gerald W. R. Templer, a World War II veteran who had commanded a division and had served as the director of the military government in Italy and as the director of military government in the British zone of occupied Germany after the war. Templer understood the principles of the indirect approach and accepted the “Five Principles of Counterinsurgency” prescribed by Sir Robert G. K. Thompson, serving as secretary of defense for Malaya.

- The government must have a clear political aim: to establish and maintain a free independent and united country which is politically and economically stable and viable.

- The government must function in accordance with law.

- The government must have an overall plan.

- The government must give priority to defeating the political subversion, not the guerrillas.

- In the guerrilla phase of an insurgency, a government must secure its base area first.

Thompson (at the time a British lieutenant colonel) and Templer worked closely together in developing and implementing successful counterinsurgency plans. Their success led Americans into a “blithe sense” that defeating communist insurgencies was feasible.2

Nagl paints a fairly rosy picture of British Malayan COIN policy and execution. He argues that the British in Malaya took the approach of separating villagers from the guerrillas. The Malayan version of “New Villages” evolved as

settlements for the Chinese squatters, estate workers, and villagers that protected them behind chain link and barbed wire fences, lit with floodlights and patrolled by Chinese Auxiliary Police Forces. More than concentration camps, the New Villages would include schools, medical aid stations, community centers, village cooperatives, and even Boy Scout troops. As the locals gained confidence in the determination of the government to protect them, they would progress from serving in an unarmed Home Guard through to keeping shotguns in their homes, ready for instant action. . . . By the end of 1951 some 400,000 squatters had been resettled in over 400 “New Villages.”3

Porch’s recent scholarship indicates that the British COIN goal of “resettling” half a million Chinese squatters into New Villages did little to earn the locals’ confidence; what happened was coercion.4 The British prevailed in the Malayan Emergency with a force that had been doubled to twenty-one battalions, “more men than the British had seen fit to deploy to defend Malaya and Singapore against the Japanese in 1941.”5

Birtle, in his own equally researched work on the evolution of COIN doctrine, made this observation about early American enthusiasm for British practices in Malaya:

All too often Americans saw only what they wanted to see in [COIN] episodes. They tended to overestimate the ease and extent to which resettlement programs and political reforms had won the hearts and minds of the people while ignoring contradictory evidence and minimizing the role that coercion had contributed to the success of [the campaign].6

David French’s recent scholarship indicates that reusing the elements of a seemingly effective COIN strategy from a successful colonial power’s template, no matter how well intentioned, risks failure and frustration.7 During the early 1960s, the Americans designed their own version of the Malayan New Villages program and rebranded it the Strategic Hamlet Program without thinking through all the elements of the Templer-Thompson indirect strategy.

Nevertheless, during 1962, the Diem regime was reporting major progress with the Strategic Hamlet Program, which was expanding rapidly in almost every province. In the Mekong River delta by the end of 1962, the GVN had built four thousand strategic hamlets out of a program goal of sixteen thousand. The Diem regime and its American sponsors were claiming that the program had enabled the GVN “to gain effective control over one-third of the rural population in the Mekong delta and two-thirds of the people living between Saigon and the 17th parallel.” General Paul D. Harkins, the first commander of MACV and General Westmoreland’s predecessor, predicted in early 1963 that South Vietnam would enjoy a “white Christmas” in 1963 because insurgent activity would be reduced to the point that the ARVN’s color-coded maps would show all provinces as white (the color that designated an area under firm government control).8

One might conclude that the American and South Vietnamese optimism in 1962–1963 was grounds for believing that the Diem regime was winning the war, but the North Vietnamese reacted to the Strategic Hamlet Program with a strategy of their own. The official NVA history acknowledges the scope, scale, and effectiveness of the Strategic Hamlet Program. The strategic hamlet number in the Pribbenow translation of the NVA official history is 3,250 and concurs with the GVN conclusion that it controlled two-thirds of the rural population. At this stage, the North Vietnamese politburo decided to send major NVA reinforcements to South Vietnam, forty thousand cadres and soldiers by the end of 1963.9

The Strategic Hamlet Program was an early instance of how the American and Vietnamese governments viewed their respective concepts of nation building. Edward Miller’s recent research shows that although the GVN with American help had built thousands of strategic hamlets,

there was precious little evidence that hamlet residents had embraced the self-sufficient outlook that [Ngo Dinh Diem and his close adviser brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu10] had defined as the raison d’etre of the program. Indeed, Nhu frequently complained to his subordinates, the government’s own officials had largely failed to understand the ideological goals behind the program. In lieu of such understanding, these officials concentrated on the construction of hamlet fortifications and on the physical control of the population via coercive and even brutal methods. . . . Most retrospective studies of the Strategic Hamlet Program at the provincial and local levels in South Vietnam have underlined the program’s coercive character, as well as the gulf that separated the theories formulated in Saigon from the regime’s actual practices in the countryside.11

One of the sources Miller cited is Race, who described the program’s collapse in Long An:

The strategic hamlet concept exemplifies in clearest form the government’s reinforcement strategy. It might be said that the program gathered into one effort all the government strategic errors: the incentives for living in the strategic hamlet were not relevant to the reasons for assistance to the revolutionary movement (and in fact these incentives, irrelevant as they were, never materialized in any case); the program devoted its resources to a physical reinforcement of the existing social system and of those who held power under it; the form of physical reinforcement adopted was founded on an explicit conception of security as the physical prevention of movement; security was explicitly intended to apply to the population in general, although the population was not the object of attack; and the thinking which led to the adoption of the strategic hamlet program was based on a severe miscalculation of its conflict aggravating consequences. . . . The strategic hamlets . . . represented no positive value to the majority of their inhabitants—on the contrary, as the testimony of even government officials showed, they were a terrific annoyance, through controls on movement which interfered with making a living, through demands for guard duty which interfered with sleep, through the destruction of homes and fields.12

The recognition was growing within the US government and among some officers in MACV that South Vietnam could not ultimately sustain itself as an independent state unless it undertook serious “political reform and true self governance prevailed at the top while also working its way up from the bottom.”13 This recognition failed to identify the differences between preemptive policies that might have motivated the rural population to turn away from the revolutionary movement and reinforcement policies that focused on providing physical security for a rural population that neither sought it nor needed it.

This dichotomy did not diminish official American enthusiasm for a comprehensive program. President Johnson in May 1967 assigned one of his senior and most vigorous White House aides, Robert W. Komer,14 to pull together government-wide resources into a new pacification organization, Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS), with the rank of ambassador.

Known as the “Blowtorch,” Komer’s “hyperkinetic” bureaucratic style was regarded as effective among some Americans, but much less so with the Vietnamese.15 Having been handpicked for the job by President Johnson, he was extremely confident in his position, unused to being challenged, and very powerful as long as he lasted. His deputy, Ambassador William E. Colby, a veteran intelligence officer whose career dated back to the World War II Office of Strategic Services and who had served in Saigon as CIA chief of station in the early 1960s and who also ran the Phoenix Program, succeeded Komer in November 1968. Phoenix was designed to identify the civilian cadres supporting the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, often and more commonly referred to as the Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI), and to neutralize it by capturing Viet Cong operatives and persuading them to defect to the GVN side or killing them. Colby directed the Phoenix Program under CIA funding.16

The creation of CORDS was “perhaps the most remarkable example of American institutional innovation during the Vietnam War” because it incorporated personnel from the CIA, US Information Agency (USIA), US Agency for International Development (USAID), State Department, White House, MACV, and all of the military services into one theater-level organization numbering at its peak eight thousand staff and advisors.17 The effectiveness of CORDS is a continuing point of debate among a number of Vietnam War scholars.18

Ambassador Komer’s tenure as Westmoreland’s (later Abrams’s) civilian commander of “the other war” lasted eighteen months (May 1967 to October 1968). Komer’s record as President Johnson’s director of the CORDS pacification program has until recently been relegated among the group of “second-echelon” officials largely ignored because of their association with an unpopular war under Johnson and, no doubt in Komer’s case, because of his aggressive, overbearing personality. He clashed with both American and Vietnamese leaders and military commanders, eventually clashing directly and publicly with General Abrams. Komer thus became a transitional figure in Vietnam. But his organizational skills, leadership, and understanding of the criticality of the GVN’s responsibility for pacification enabled him to hand off to his deputy, Ambassador Colby, a functioning organization that continued to operate. The CORDS organization that Komer created not only imposed horizontal integration of the civil and military components of pacification but also ensured vertical integration through the establishment of lines of control and communication from the embassy in Saigon to the districts in the countryside. Komer also tried to impact the GVN bureaucracy by increasing the authority, responsibility, and competence of Vietnam’s forty-four provincial governments.

Komer in 1972 wrote a Rand monograph about his and CORDS performance in Vietnam, Bureaucracy Does Its Thing: Institutional Constraints on U.S.-GVN Performance in Vietnam.19 It is a remarkably candid and insightful document both for what its author believes was the war’s flawed strategy and for what he ignores. The phrases “institutional constraints” or “bureaucratic inertia” and their variants are mentioned sixteen times in the nine-page summary (of a much longer report) as a way of explaining the US “lack of unified management” in Vietnam. Indeed, Komer spends four out of nine chapters on this subject.20 Bureaucracy reads like a primer on the frustrations of public administration for US agencies operating abroad, but not on how to align policy, strategy, and operations to win a war. Race’s incisive analysis of the revolutionary movement’s theory of victory made no impression on Komer. It was as if he were reading something by someone from another empirical universe.21

Among the many programs brought under CORDS management and control, Komer viewed one of his principal jobs as that of measuring the effects between pacification efforts in the countryside and what the military was accomplishing in the field. One of CORDS’ key measurement systems was the Hamlet Evaluation System (HES). No one during the Vietnam War was more involved in quantification and measurement than Secretary McNamara. McNamara’s focus on statistics to evaluate progress during the Vietnam War included number of operations, number of enemy killed, number of captured weapons, and, in the case of HES, scoring the effectiveness of pacification progress. Komer’s CORDS evaluation systems emulated McNamara’s quantification. The Hamlet Evaluation System placed Vietnam’s thousands of rural hamlets in one of six categories: A, B, C, D, E, or V. The A–C categories denoted degrees of hamlets being relatively secure, while D and E meant they were contested. Those designated V, for “under VC control,” were considered to be under enemy control. The HES, launched in January 1967, involved some 250 MACV or MACCORDS district advisors completing monthly evaluation worksheets for 12,700 of South Vietnam’s hamlets using a worksheet of eighteen equally weighted indicators: nine relating to physical security and nine relating to development.22 Despite its data-gathering problems, HES was considered more accurate than the subjective system it replaced.23 The HES designers believed they could identify and measure major pacification trends and problems.24 At the end of 1967, HES indicated that two-thirds of the population were living in “relatively secure” areas, though that figure was open to interpretation and debate.

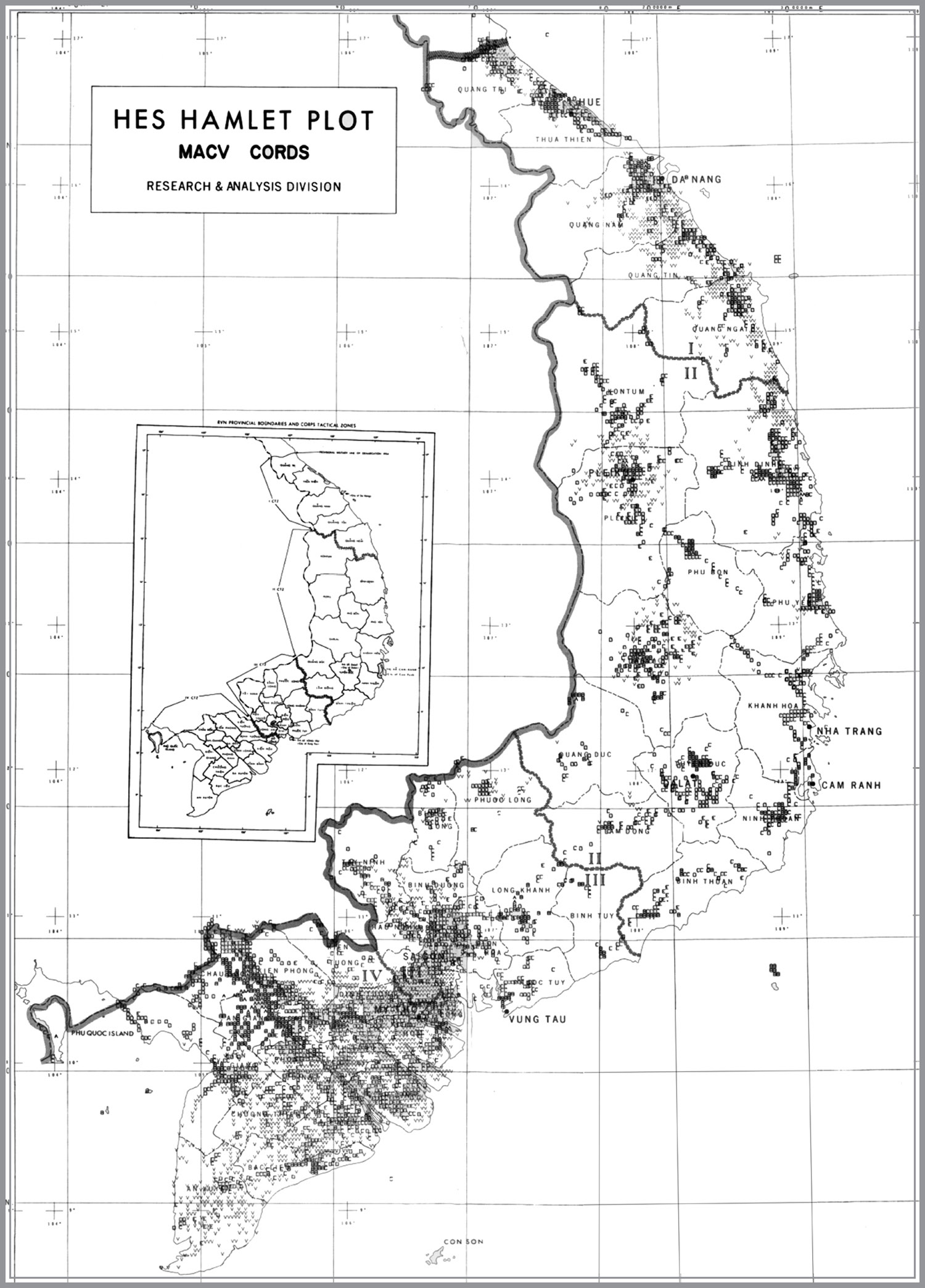

By 1968, HES reports also included a countrywide map (map 19.1) indicating that 67 percent of Vietnam’s population lived in secure hamlets, towns, or cities. The January 31, 1968, HES map plotted 5,300 color-coded letters in blue for A, B, and C (secure), green for D and E (contested), and red for V (under VC control), representing 12,700 hamlets.

Map 19.1. The CORDS Hamlet Evaluation System map plot for January 1968 showed that 67 percent of Vietnam’s population lived in secure hamlets, towns, or cities.

Source: Map acquired by author from MACV headquarters, Ton Son Nhut Air Base, Saigon, in March 1968. Shown is a black-and-white electronic scan of the original color-coded computer-generated output of 22.5 × 29 in. plot; darker data points are V-scored (under VC control) hamlets.

HES Hamlet Plot

The January 1968 HES data, plotted as 5,300 data points representing 12,700 hamlets on a 1:1,000,000 map, indicated that 67 percent of the population lived in “secure” (A+B+C) hamlets.

|

A |

Adequate security forces, infrastructure, public projects underway, economic picture improving. About 18 percent of total hamlets are A and contain about 5 percent of the total hamlet population. |

|

B |

Not immune to VC threat but security is organized and partially effective, infrastructure partially neutralized, self-help programs underway and economic programs started. |

|

C |

Subject to infrequent VC harassment, infrastructure identified, some participation in self-help programs. |

|

D |

VC activities reduced but still an internal threat. Some VC taxation and terrorism. Some local participation in local hamlet government and economic programs. Contested but leaning toward GVN. |

|

E |

VC are effective although some GVN control is evident. VC infrastructure intact. GVN programs are non-existent or just beginning. |

|

V |

Under VC control. No GVN or advisors except on military operations. Populace willingly or unwillingly support VC. |

Note: Population is a far better measure of GVN control than hamlets. Countrywide, approximately 67 percent of population (including urban) is in A+B+C categories, i.e., secure. Yet only about 40 percent of hamlets are secure. “A” hamlets average 3,000 people each; VC hamlets average 710.

Source: Printed by the 66th Engr Co (TOPO) (CORPS)

It was CORDS work products like the HES map plot that prompted General Westmoreland to express optimism about the war’s progress in a November 1967 speech to the National Press Club in Washington and a press conference at the Pentagon. While he never publicly used the phrase “light at the end of the tunnel” to characterize the progress, others in the administration did. In fact, Westmoreland used it in a military cable to his deputy, General Abrams.25 This phrase lingered in the public mind long after the war ended as an expression of the perceived bankruptcy of the Johnson administration’s military and pacification strategy. If HES was intended as a way to measure the effectiveness of the administration’s strategic architecture in Vietnam, by implying that its quantitative scores were the basis for claiming a light at the end of the tunnel, it had failed.

The Tet Offensive, which the NVA and VC launched on February 1, 1968, initially appeared to make the HES plot irrelevant for accurate measurement of the security situation. Nevertheless, there was a frenetic rush to get district advisors back into the field in the following weeks to produce a new map plot. The classification of countrywide HES reports and map plots went from pre-Tet “For Official Use Only” to post-Tet “Top Secret,” limited to a small group of senior MACV and CORDS personnel under very strict “need-to-know” criteria among those cleared for TS, signifying to many informed sources in Saigon that the administration’s credibility would be further damaged if the HES reports were released to a wider distribution.

Ironically, the pre-Tet ratings had put 67 percent of the population in the relatively secure categories. The post-Tet measurements indicated that the figure was knocked down to 60 percent during the offensive but rebounded back to 66 percent by August 1968.26 So release of the HES work products might have helped bolster the administration’s and MACV’s positions on the merits, but its top-secret classification rendered public release moot.

In the late fall of 1968, Colby succeeded Komer. His service as CORDS deputy under Komer had already established a strong working relationship with General Abrams as COMUSMACV, who had succeeded General Westmoreland in July 1968, and Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker, who had succeeded Henry Cabot Lodge in 1967. Three recent Vietnam War historians regard Abrams, Bunker, and Colby as an effective triumvirate that dramatically reversed a deteriorating situation between 1968 and 1972.27

Although designed to operate in a series of advisory and support roles, CORDS began to assume the form of a parallel structure to the GVN itself. While CORDS officials in the field served as advisors and enablers of pacification, they were never intended to assume governance roles in the society hosting them, although many of them probably wanted to.

Colby initiated an “accelerated pacification program” to increase security in all hamlets. In December 1969, HES scores were showing that 90 percent of hamlets merited C ratings or better, half of them in the A and B categories. By late 1972, this figure reached 97 percent. As John W. Root observes,

Unquestionably, much of this “progress” was due to a drop in the intensity of the war, increasing the Regional and Popular Forces, and the success of the Phoenix Program. Retrospective studies show that HES figures suffered from inflation caused principally by command pressure and undervaluing security. Surveys of former district advisers revealed the existence of “gut HES” parallel reports that were more realistic and pessimistic, but these never got into the computer.28

Another possible explanation for inflated HES scores is that they were an important factor in American military advisors’ Officer Efficiency Reports (OERs). Having good OERs in one’s service jacket was essential to promotion. So there was an inherent conflict of interest built into the HES insofar as the scorers could influence their OER evaluations by fudging HES scores in a positive direction. There is no evidence that this happened on a systematic basis, but the opportunity to manipulate scores to one’s advantage was built into the system.

David W. P. Elliott is a Vietnam War scholar who has studied the utility of HES data products in some detail. While he acknowledges that HES “became a symbol of both the technocratic-managerial mentality of McNamara and his ‘whiz kids’ and their failure to understand the underlying complexities of revolution and social transformation,” he points out that HES gave an indication of the “‘security situation’ in a hamlet, and provided a reasonable indication of the likelihood of a GVN force getting shot at if it operated in the hamlet.” He is equally balanced on what HES did not reveal:

What does HES not tell us? Political loyalties, as opposed to observable behavior are beyond the reach of HES, both in principle and by design. As the HES evolved, it was aimed increasingly at eliminating subjective judgment and concentrating only on verifiable facts. Did the hamlet chief sleep in the hamlet or not? Was a bridge being built or wasn’t it? Both the binary logic of the computer and the desire to standardize local responses so some meaningful national data could be generated dictated this approach. One of the paradoxes of the HES is that as its designers sought less subjectivity, they also increasingly attempted to measure more subtle indicators of “progress” in the complex struggle. When the early versions of the HES merely attempted to reflect the security situation, its rough indicators were suitable to the task, but as it addressed the more abstract questions of socioeconomic development, the rating process seems to have bogged down in the task of measuring the unmeasurable.29

In 1968, thirty-five years before Elliott’s publication, the late Lieutenant Colonel William R. Corson, who commanded the Marine Combined Action Platoon program in I Corps and who was intimately familiar with HES, had published scathing remarks about “measuring the unmeasurable.” His book was withering in its critique of HES and the purposes for which it was used:

Although the HES appears thorough and elaborate, it is accurate only to the extent that those who are using it in the field are accurate. And herein lies another very definite weakness in the system. Each district in which we have advisory teams has between fifty and 100 hamlets. On the average, due to the activity conditions and other demands on the adviser’s time, he cannot visit in a month more than one out of four hamlets, yet he must “grade” each one (except for Viet Cong–controlled hamlets) every month. In addition, the time spent in the hamlets actually visited is about thirty minutes to an hour. As a final straw, the adviser possesses no special skills such as fluency in Vietnamese, experience in development economics, in knowledge of anthropology, sociology, or political science to help him carry out the complex grading task. As a result, the rating assigned to each hamlet is based on the grossest of measurements. In spite of these weaknesses, HES would not lack some utility if it were used to reveal problems rather than trumpet paper progress for political reasons.30

Corson analyzed the ambiguity of the HES grading criteria under the A–E and VC categories. He then drove home his point by illustrating the meaninglessness of the A and B scores by pointing out that a hamlet near the provincial capital of Quang Nam Province in I Corps, Cam An, oscillated between an A and B score throughout 1967. Cam An was used as a pacification showcase for a personal fact-finding visit by Senator Clifford P. Case, briefed by Ambassador Henry L. T. Koren, the deputy for CORDS in the I Corps area. Corson pointedly observed,

In point of fact there had been no [italics in original] overt military incidents for several months against Cam An, but the hamlet’s residents were being taxed regularly by the Viet Cong. Each of the peasants who traveled the four miles to the [provincial] capital to market his fish and rice carried with him a Viet Cong tax receipt to insure his safe conduct through the “enemy lines.” This is the reality of the GVN’s pacification situation—the incidents of terrorism, attacks, and sabotage are only the visible portion of the iceberg. The ubiquitous and pervasive presence of the Viet Cong is evident in the entire fabric of Vietnamese society.31

While these issues of measurement were debated between Saigon and Washington, McNamara’s and Komer’s “war by the numbers” was never reconciled with the visible violence the public was seeing in news reports and telecasts during and after the Tet Offensive. A month into the Tet Offensive, CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite said the following in an unusual and unprecedented “editorial opinion” at the end of the evening news broadcast on February 27, 1968: “For it seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate.”

President Johnson said after watching this broadcast, “That’s it. If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.”32 The Pentagon’s and MACV’s confidence in the CORDS measurement systems and the optimistic outputs they were producing in late 1967 and early 1968 had been fatally undermined, no matter what the numbers were showing. The Tet Offensive had shattered the American public’s confidence in the war, and with it the Johnson administration’s strategic architecture.