Food plants, fruits and foreign foodstuffs: the archaeological evidence from urban medieval Ireland

Department of Archaeology, Connolly Building, Dyke Parade, University College Cork

[Accepted 4 December 2014. Published 15 May 2015.]

Abstract

The historical record is largely used to qualify the consumption of cultivated crops, and other food plants, such as fruits, vegetables, herbs and imported goods in the medieval Irish diet. Despite our rich literary sources, evidence for horticulture as well as the use of collected and exotic foodstuffs in medieval Ireland is still under-represented, and the remains of such plants rarely survive to make any inferences on the subject. The increase in archaeobotanical research in Ireland is producing a valuable archaeological dataset to help assess the nature, composition and variation of food plants in the medieval diet. Botanical remains preserved in anoxic deposits provide a unique snapshot of the diversity of plants consumed at a site, including information on processing techniques, storage and seasonality. With particular reference to urban medieval sites dating from the tenth to the fifteenth centuries, this paper will present and appraise the archaeological evidence for the use and consumption of cultivated, wild and imported foodstuffs, and the areas of research that still need to be addressed.

Introduction

The main source of information for the types of food plants consumed in medieval Ireland, including agricultural production, is documentary evidence.1 Over the last 20 years however, the increase in archaeobotanical studies has contributed greatly to research in the areas of arable agriculture, diet and food-processing in Ireland.

The main advantage of using documentary sources is the precisely dateable data that exists providing a calendrical marker for the archaeological record. Early medieval law tracts such as the eighth century AD Bretha Déin Chécht2 and literature associated with saints’ lives3 also provides details on crops and food plants based on a hierarchical system. From the thirteenth century records on land use, landholdings, agricultural practices and food liveries featured prominently in the accounts of Anglo-Norman demesnes, manorial holdings and monastic estates in Ireland.4 While reference to crop yields, and gardens and orchard produce are found in these sources, explicit details on fruit, vegetable and herb consumption is scarcer.5 These accounts only provide information on land managed directly by the estate rather than on the people who held individual leasings. The content of these records can be selective in what was recorded, with more emphasis on food consumption from rich households and imported goods. Evidence, therefore, for food consumption is more likely to be available for the upper social classes with little regard for other social groups, such as the tenant farmer, the peasantry and urban populations.6

Since the 1980s, archaeobotanical studies in Ireland have been on the increase, largely driven by Mick Monk’s work on charred macroscopic cereal remains.7 In the last fifteen years the nature of infrastructural projects and commercial developments greatly changed archaeological excavation practices in Ireland. These practices included strategic and rigorous sampling of archaeological features and deposits for the recovery of environmental material, such as plant macrofossils.8 As a result, the archaeobotanical evidence for field crops is now well represented and this new corpus of environmental data has contributed greatly to our knowledge of past agricultural practices. In order to facilitate the analyses and synthesise of this data, research projects such as the Cultivating Societies Project9 and the Early Medieval Archaeological Project10 have been influential in disseminating much of this unpublished work. This information is playing a pivotal role in redefining our understanding of past agricultural practices as well as their impact on societal and landscape change.

Archaeobotanical studies also play a vital role in interpreting urban life in medieval Ireland due primarily to the organic matrix11 of these sites. The Viking Dublin excavations carried out by the National Museum of Ireland12 represent the most prominent work undertaken in this area. These campaigns provided a unique opportunity to implement sample strategies for the recovery of animal and plant remains in an attempt to interpret the food-processing practices and diet of a growing urban centre in the ninth and tenth centuries AD. Fruits, vegetables, lesser-known field crops and imported foodstuffs, were among the plant remains recorded, offering new insights into the variety of food available and consumed during the medieval period. The archaeobotanical works carried out by Frank Mitchell13 of Trinity College Dublin and later by Siobhán Geraghty14 produced a body of archaeological information that was central to understanding daily life in medieval Dublin and became a paradigm for other urban medieval projects that followed.15

Archaeobotany is now recognised as an essential component of archaeological interpretation and historical justification, and can complement documentary sources to offer important contributions to the study of medieval agriculture, horticulture and the use of wild food plants. While both sets of evidence suffer from differential survival and varying degrees of preservation, the disparity between these sources must also be appreciated as they will inevitably provide conflicting sets of evidence. Despite this, it has become apparent that a multidisciplinary approach is required in order to fully understand medieval food economy and the theoretical and taphonomical problems facing archaeological interpretation.

The documentary and archaeobotanical evidence presented for cultivated plants has focused predominantly on cereals in the medieval Irish diet. This can result in a poorer understanding of the role of other food plants, such as fruits, vegetables, pulse crops, herbs and imported foodstuffs. Historical sources for food produce from orchards and gardens as well as gathered wild plants are scarce and are often discussed generically as ‘fruit’ and ‘vegetables’.16 Archaeobotanical evidence has revealed more about the variety of non-cereal food plants and garden produce through the diverse plant remains that have survived in waterlogged and organic deposits in both rural17 and urban18 contexts. Through these physical remains, we can garner a much better understanding of how garden produce, imported fruits and wild plants were processed, utilised and consumed. This is especially significant when charting the diet of the lower classes and urban populations, which often went undocumented.

In order to gain a better understanding of the variety of food plants consumed in medieval Ireland, we need to consider the archaeological evidence that survives which represents these foodstuffs. In particular the evidence for fruit, vegetables, herbs and lesser known field crops, all of which can be underrepresented in both the historical and the archaeological records. The emergence of the Norse towns in the ninth and tenth centuries and their subsequent growth during the Anglo–Norman settlement in the late twelfth and the early thirteenth centuries stimulated a growing urban population which required a sustainable source of readily available foodstuffs. The increase in trade also had a major contribution in diversifying food in medieval Ireland where foodstuffs and other commodities were exchanged at a local and international level. To understand the range of food plants consumed by urban dwellers, this paper will present archaeobotanical evidence from known urban medieval sites in Ireland, such as Dublin, Cork, Waterford, Drogheda and Wexford, including new additions from Cashel, Co. Tipperary, and Kilkenny City. The results will be evaluated in order to interpret how harvested, gathered and imported foodstuffs were utilised by urban settlers, and what new information they can contribute to medieval food and drink practices.

Urban living

The period from the late twelfth century to the early fourteenth century saw a vast and rapid increase in the establishment of boroughs and urban markets as a consequence of the economic growth that was developing under the Anglo–Norman administration. Cashel and Kilkenny, which began as early medieval ecclesiastical settlements, were two such towns that grew into prominent urban centres under the new Anglo–Norman economic system.19 This rise in urban living promoted a commercial economy trading in both local and foreign commodities, which included a variety of foodstuffs. In Cashel, for example, the granting of an eight-day annual fair by King Henry III would have greatly encouraged a market economy, opening up the town to foreign traders.20 In order to encourage urban settlement, new occupiers were given a burgage plot upon which to build a house, including subsidiary buildings, sheds, cesspits, wells, an orchard, and a garden for herbs and vegetables.21

This rise in urban living would have required a strategic system of waste management. While rivers and lakes22 would have been considered the most convenient way of disposing of domestic refuse, including faecal remains and sewage in urban areas, the main feature to contain a wealth of information concerning diet, waste disposal, health, hygiene and settlement history were cesspits.23 While the historical record merely mentions their presence as part of a burgage plot, interpreting such features requires a combined understanding of the archaeological and biological record to help with their interpretation.24 0nce they fell into disuse, cesspits were rarely emptied; instead they were covered over to save on the cost of disposal. This accumulation of organic material becomes inert and sterile, providing the perfect anoxic environment for plant preservation. Cesspits could be simple cut features or lined with wood or stone (Pl. I).25 Since cess material was often dumped into open drains, ditches and pits, and mixed with occupation layers, interpreting medieval plant debris which has accumulated under urban conditions must be done with caution.

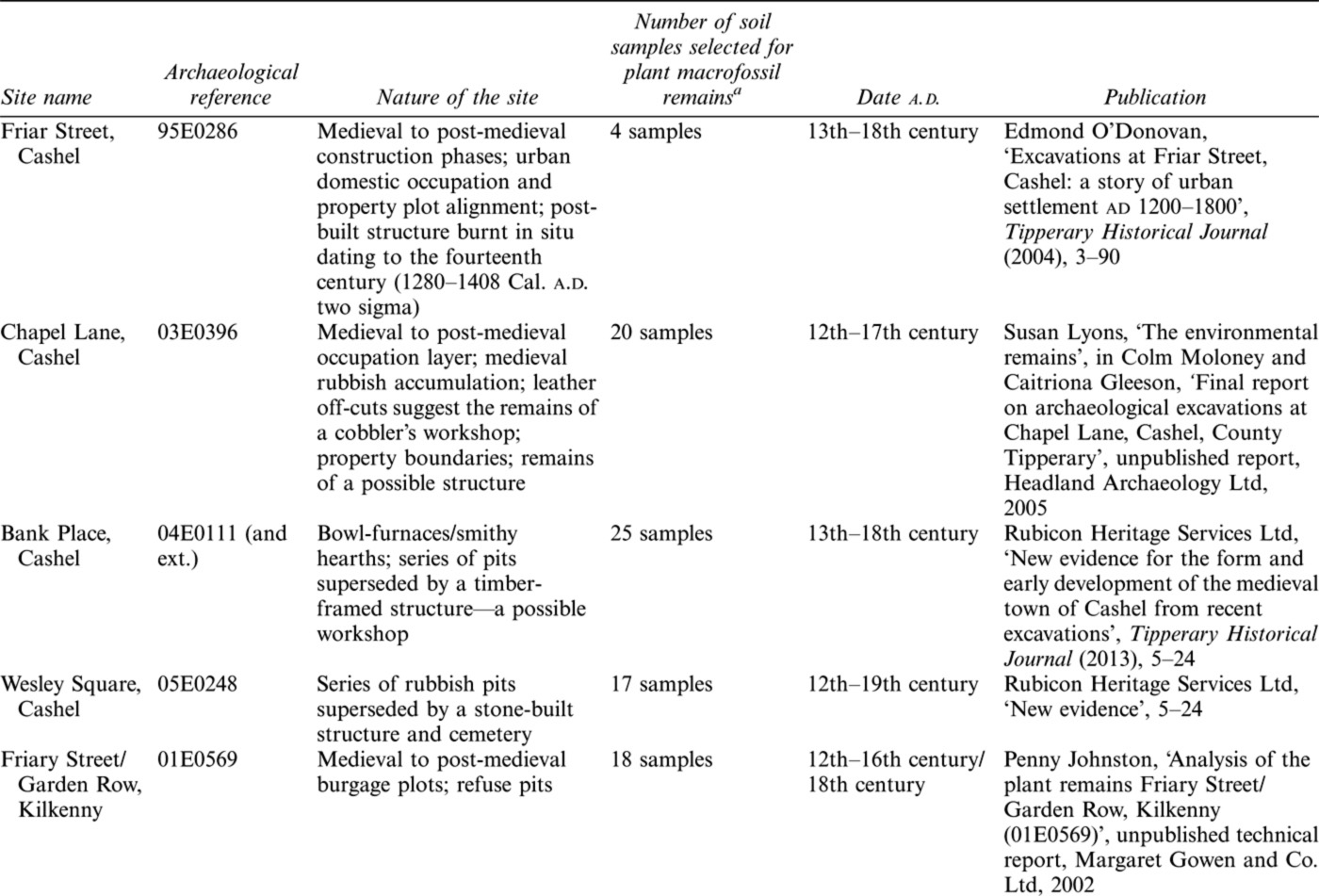

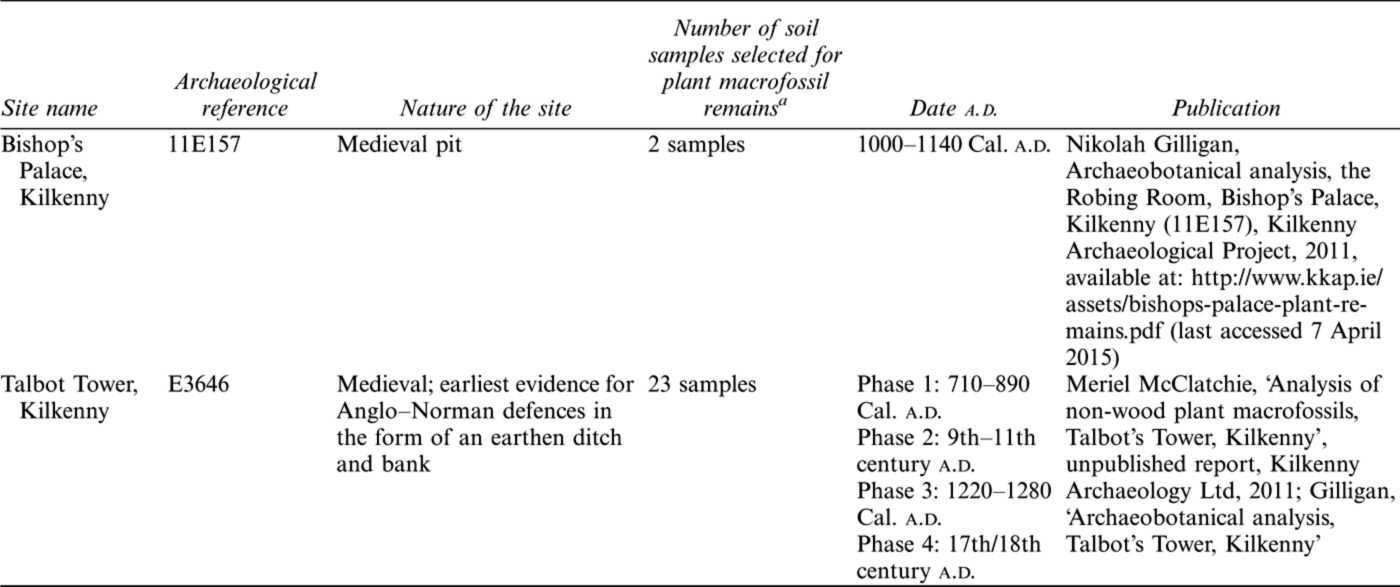

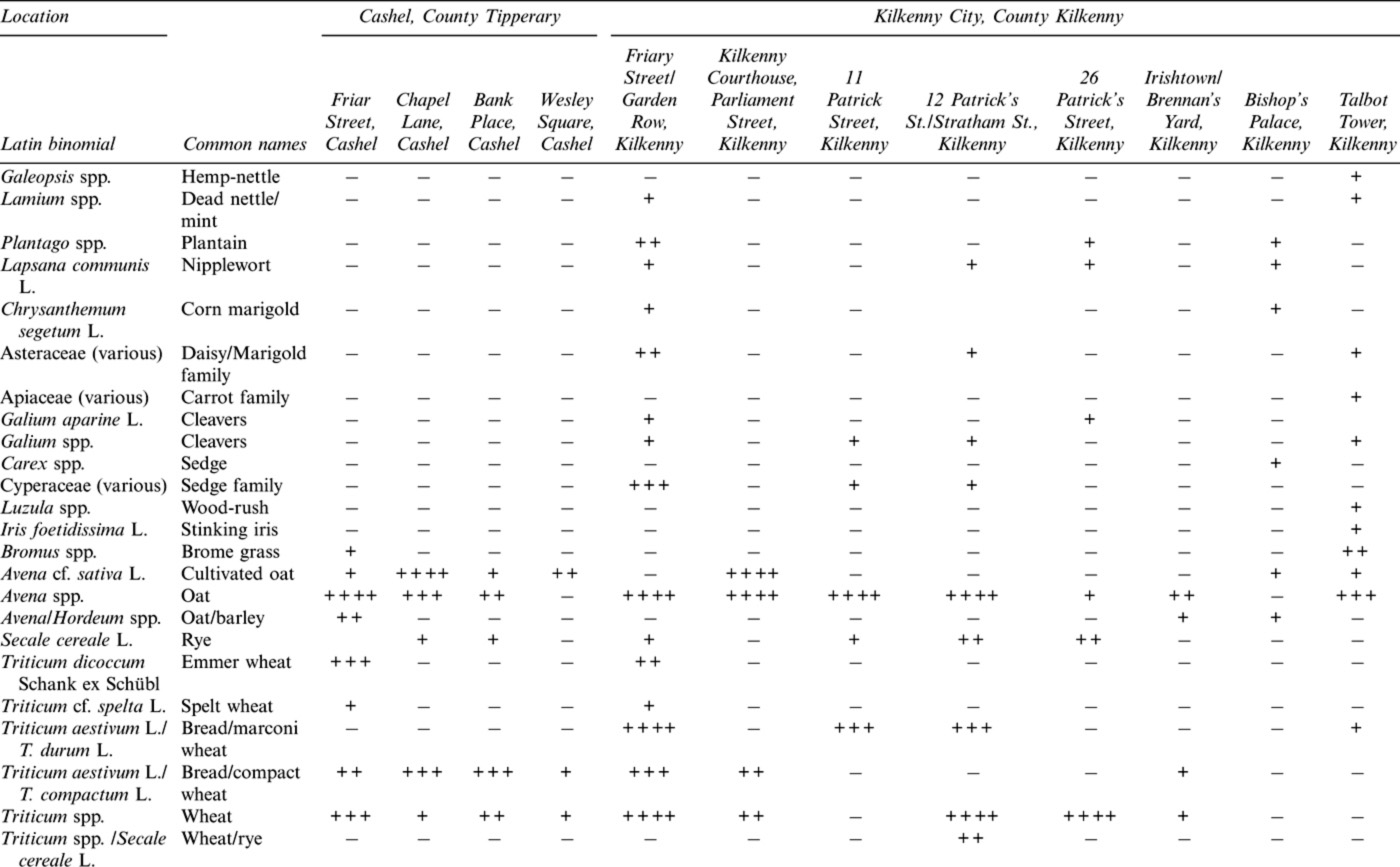

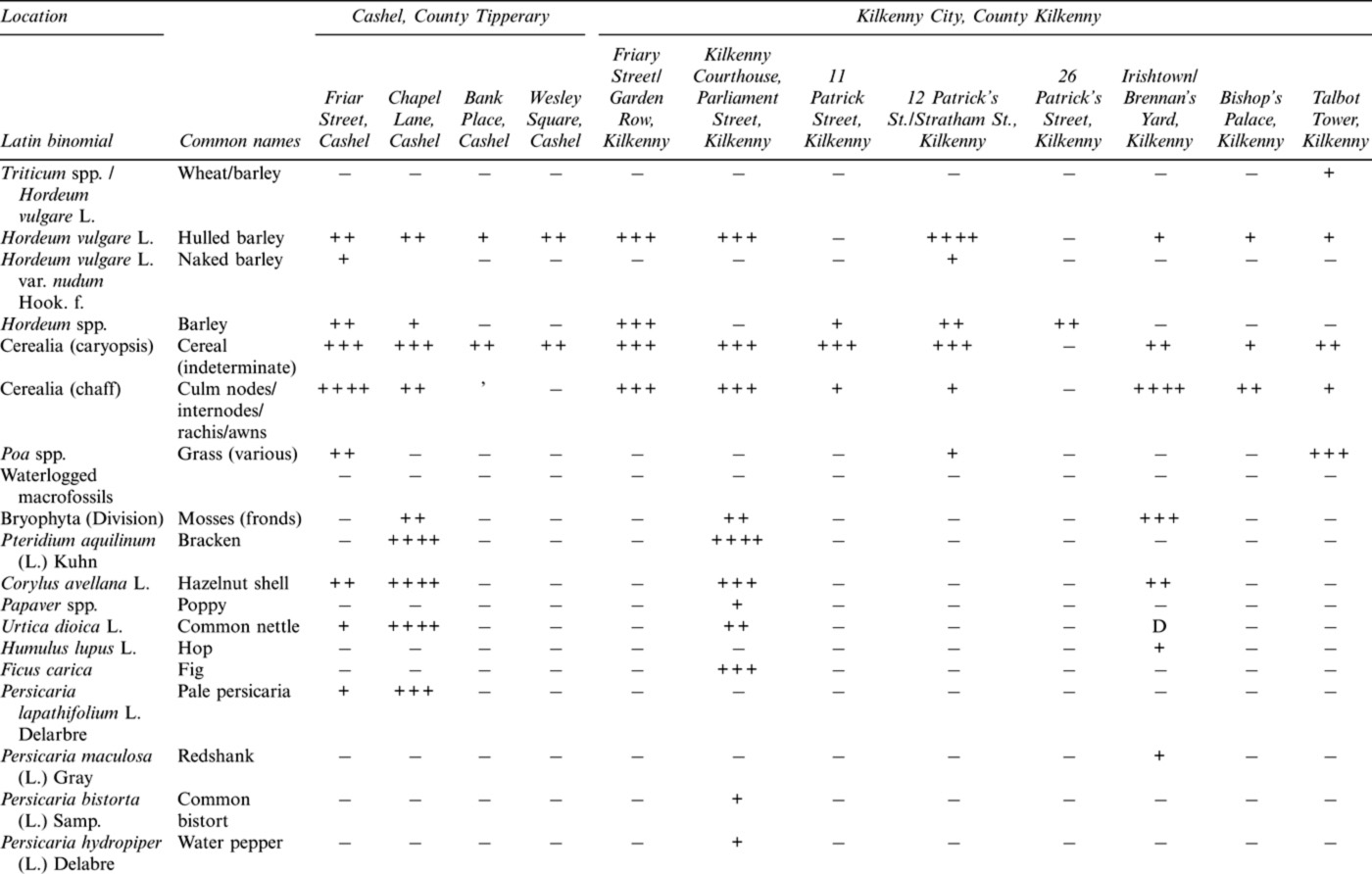

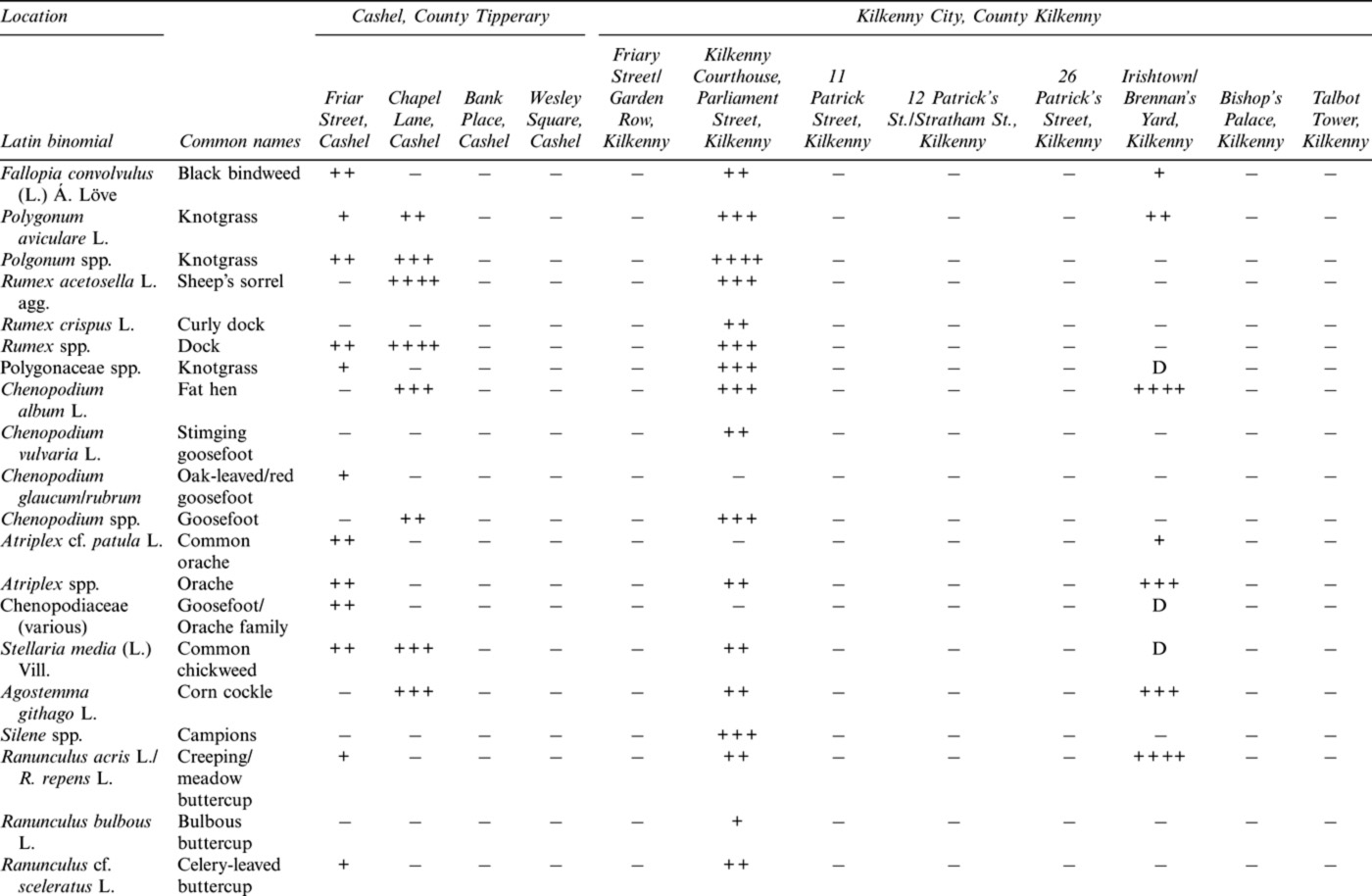

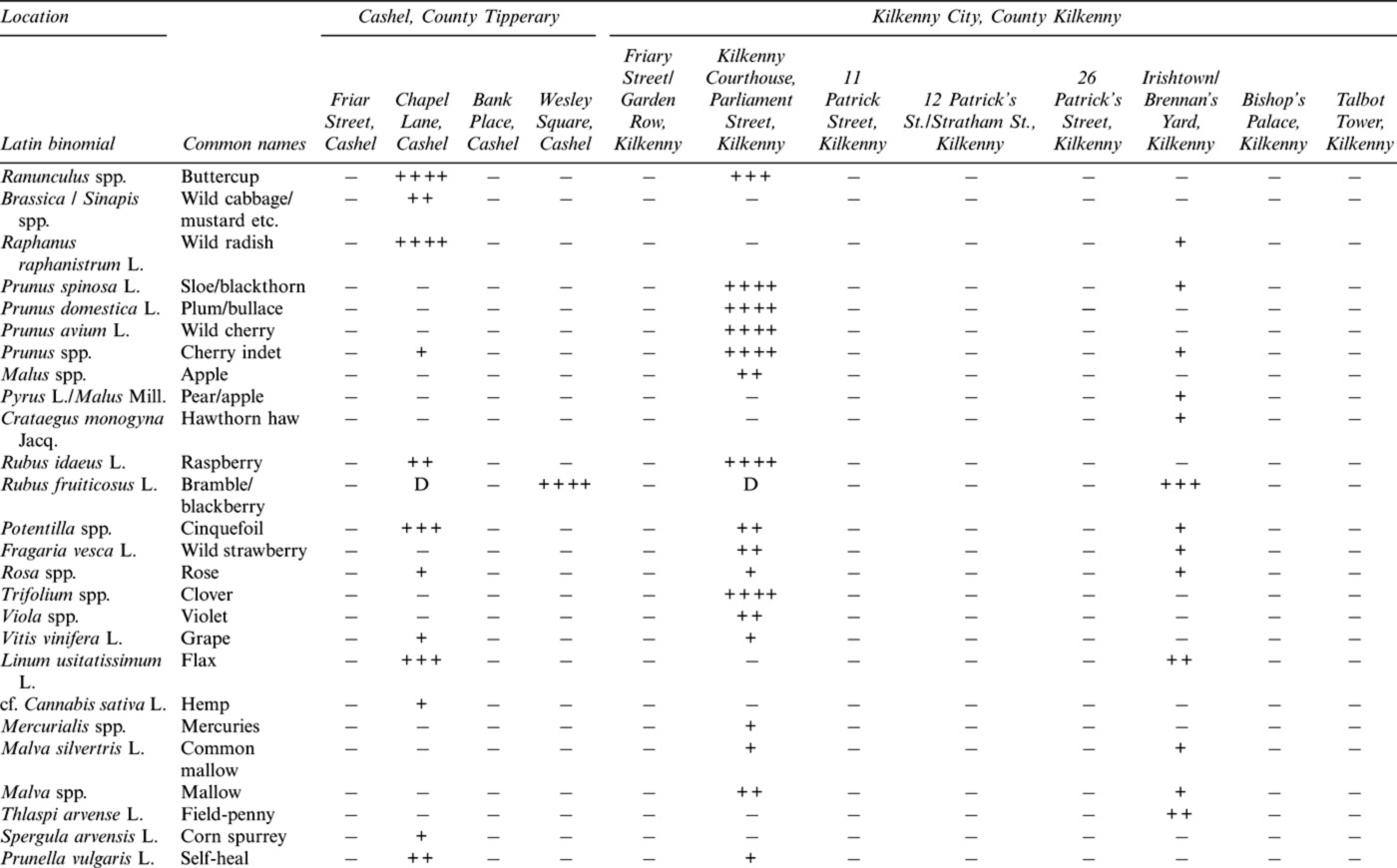

As part of this paper, four sites from Cashel and eight sites from Kilkenny City will be referenced and discussed in the context of other urban centres in Ireland (Table 1). The archaeological excavations at these sites were carried out in advance of commercial development, including alterations and extensions to existing buildings. Cashel and Kilkenny are both listed as historic towns in the Record of Monuments and Places26 and are therefore protected under the National Monuments Acts 1930–2004. This includes their historic core, which contains numerous sub-elements of archaeological and historic interest, as described in the Urban Archaeological Surveys for County Tipperary and County Kilkenny. Any proposed development works within the confines of these areas are, therefore, subject by law to appraisal in order to determine the impact and affect that the works may have on archaeological heritage. To facilitate the archaeological interpretation of these sites and in line with archaeological licensing procedures, strategic sampling of archaeological deposits was undertaken. The programme of post-excavation works from these locations included archaeobotanical analysis of the soils sampled, the results of which have been collated for the purpose of this paper (Table 2).

In Cashel, the sites at Chapel Lane and Bank Place fronted onto the north side of Main Street, Wesley Square on the south side of Main Street and the site at Friar Street located at the eastern side of that Street (Fig. 1). While medieval to post-medieval activity was recorded, the majority of archaeological evidence was centred on thirteenth- and fourteenth-century burgage activity. At Friar Street, the remains of a post-built rectangular structure including a possible cesspit were recorded. At Wesley Square, a series of pits were identified along with the remains of a later stone structure and cemetery. Evidence for industry was found, at Chapel Lane, where a cobbler’s workshop and possible occupation was evident, while iron-working or a smithy was located at Bank Place.27

PL. I—Top left: a reconstruction of a cess disposal (illustration prepared by Henry Buglass (David Smith, ‘Defining an indicator package to allow identification of “cesspits” in the archaeological record’, Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013), 526–43: 540, Fig. 3); top right: unlined medieval cesspit (photo: Cóilín Ó Drisceoil, Kilkenny Archaeology); bottom: medieval stone-lined cesspit (photo: Cóilín Ó Drisceoil, Kilkenny Archaeology).

TABLE 1—Summary of sites discussed from Cashel and Kilkenny.

a Soil samples averaged 10 litres in volume. Samples were selected and processed in consultation with an archaeobotanist as part of the post-excavation programme for each site. Two types of processing techniques were employed; Dry samples rich in charred remains were processed using a system of flotation. Flots were collected in sieve meshes measuring 300 microns, retents were collected in sieve meshes measuring 1mm; Samples from obvious anoxic deposits or those deemed to be potentially waterlogged were processed using a wet-sieving technique through a bank of sieves, with meshes measuring 250 microns to 2mm, in order to ensure the recovery of small seeds and finer plant parts. Considering other environmental material, such as insect remains, wood, charcoal and mollusca, a subsample of approximately 3-5 litres was processed for the purpose of archaeobotanical analysis. Examinations of these residues were carried out using a stereo microscope ranging in magnification from × 4.8 to × 56. Archaeobotanical material was identified using comparative seed collections and illustrative seed keys (e.g. A-L Anderberg, Atlas of seeds part 4: Resedaceae-Umbelliferae (Stockholm, 1994); W. Beijerinck, Zadenatlas der Netherlandsche Flora (Wageningen, 1947); N. J. Katz, S.V. Katz and M. G. Kipiani, Atlas and keys of fruits and seeds occurring in the quaternary deposits of the USSR (Moscow, 1965). Soil samples were processed in line with industry standards and guidelines as outlined in the Institute of Archaeologists of Ireland (IAI), Environmental sampling guidelines for archaeologists (Dublin, 2006); and D. Pearsall, Palaeoethnobotany: handbook of procedures, 2nd edn (San Diego, CA, 2000).

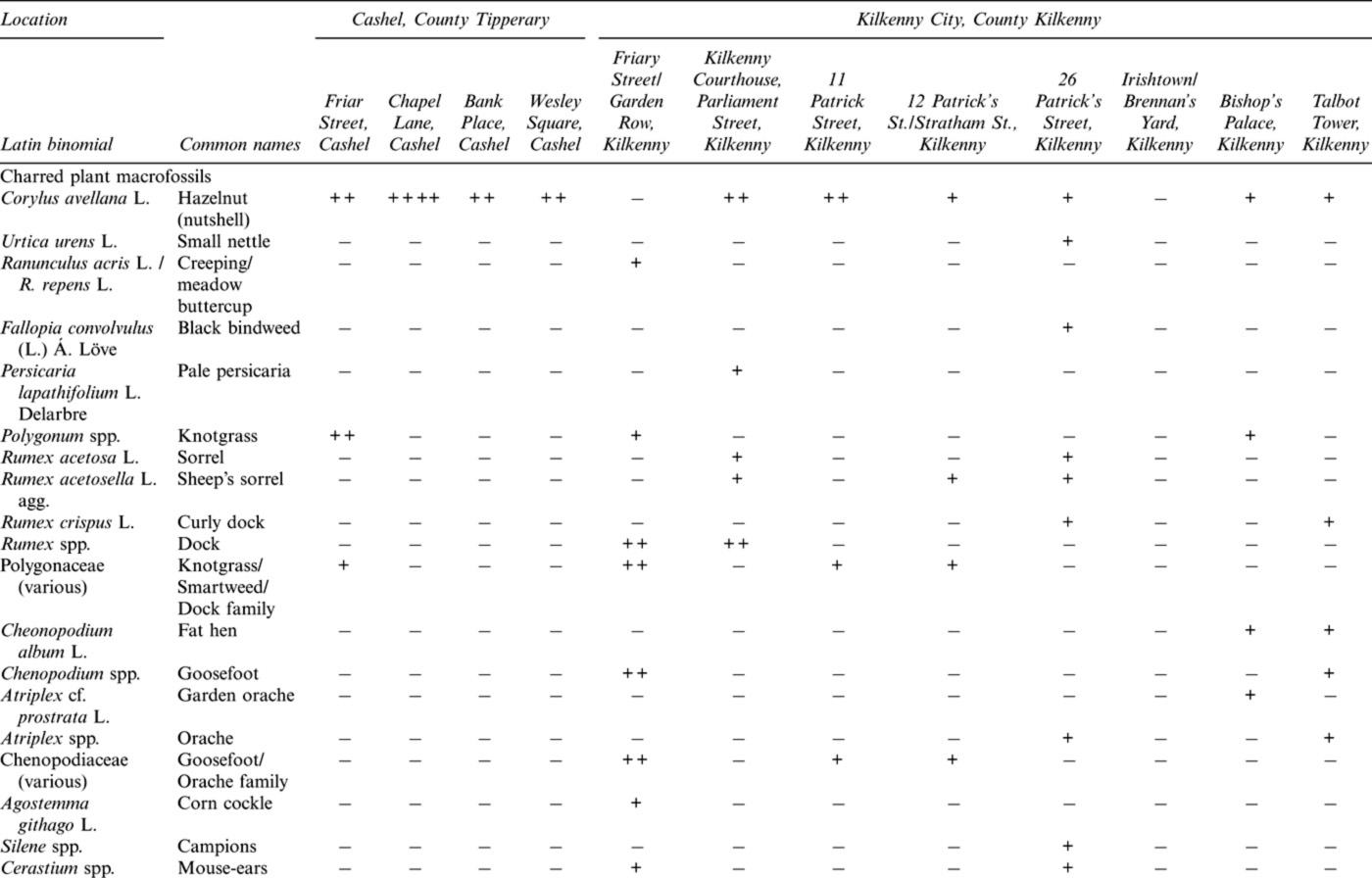

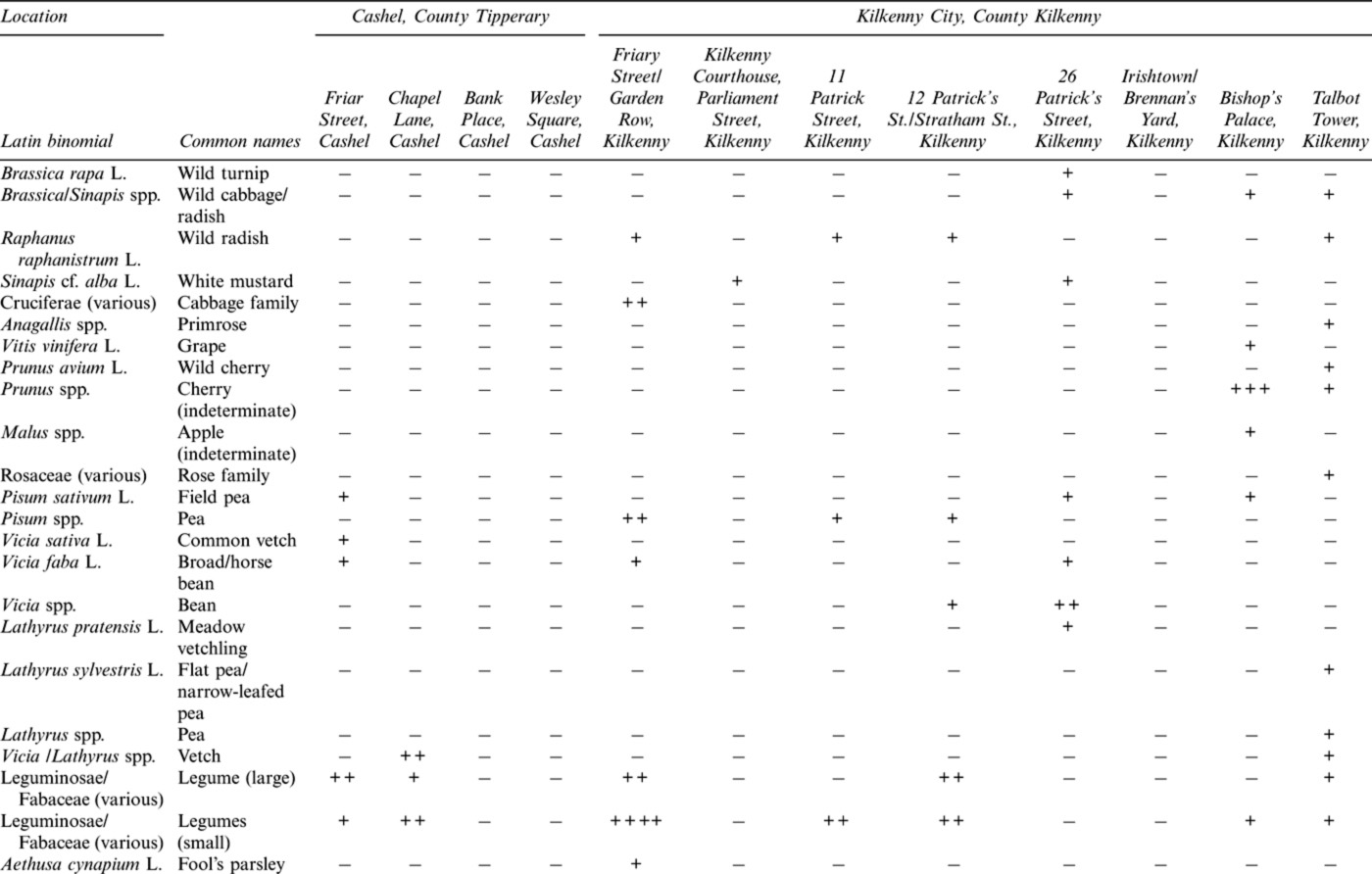

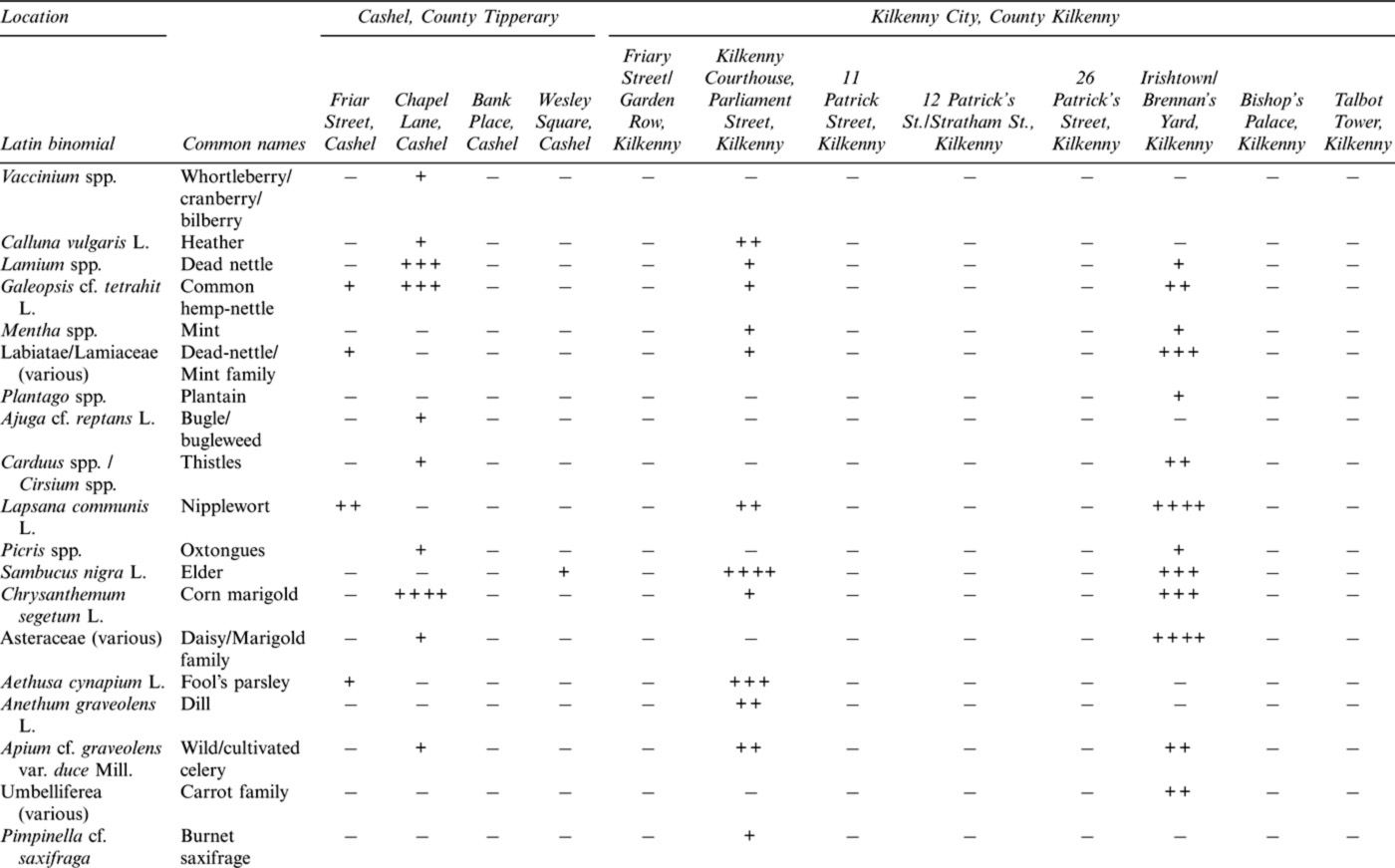

TABLE 2—The plant macrofossil remains recovered from sites in Cashel and Kilkenny.a

a Nomenclature and taxonomic order follows Clive Stace, New Flora of the British Isles (Cambridge, 2010).

The identifications refer to seeds unless otherwise stated; ’cf.’ denotes a tentative identification; since sampling and methodological procedures differed bewteen each site. For the purpose of this paper, the quantification of individual seeds is based on relative abundance using an abundance key (+, ++, +++, ++++ and D) where + = rare (< 10); ++ = occasional (11 - 50); +++ = frequent (51–100); ++++ = abundant (> 100); D = dominant (500+).

FIG. 1—Location of sites discussed from Cashel, Co. Tipperary (after Rubicon Heritage Services Ltd./Headland Archaeology Ltd); inset: aerial view of archaeological excavation at Chapel Lane, Cashel (looking south). (Photo: Rubicon Heritage Services Ltd/Headland Archaeology Ltd.)

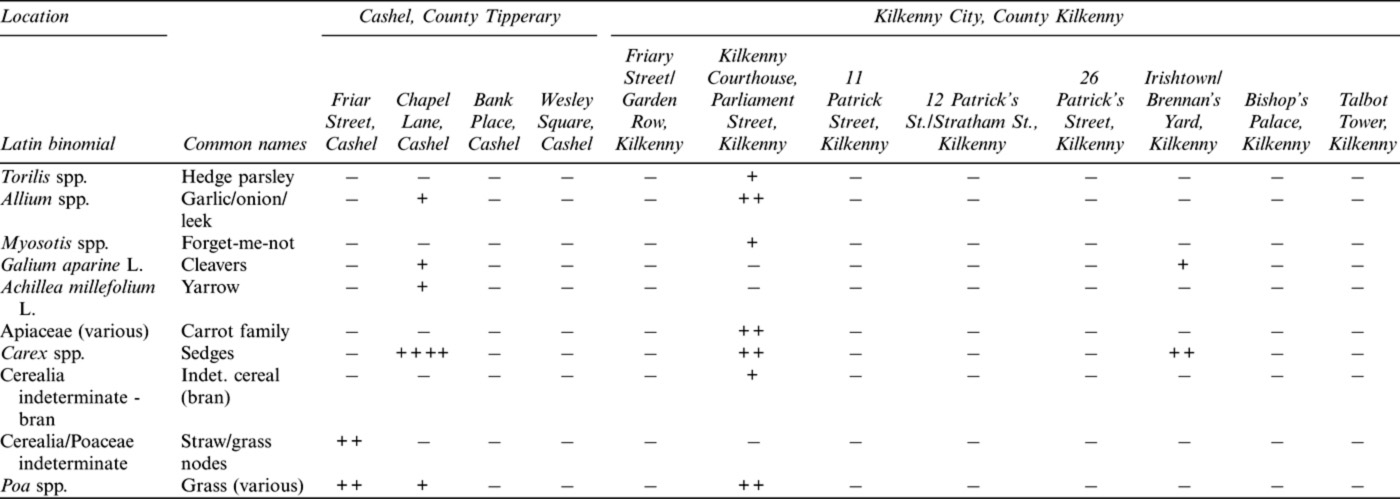

The sites from Kilkenny fall within the two main boroughs established in Kilkenny—Irishtown and Hightown. Bishop’s Palace and Brennan’s Yard were located to the north-west in the borough of Irishtown; Parliament Street was situated adjacent to the commercial High Street at the centre of the borough of Hightown, while Friary Street/Garden Row and 11, 12 and 26 Patrick Street were located to the south-west of Hightown. Talbot Tower formed part of the south-western extremity of the medieval town (Fig. 2). With the exception of Bishop’s Palace and Talbot Tower, the sites were characterised as typical medieval burgage plots, where refuse pits and plot boundaries were identified. A drying kiln was present at Friary Street/Garden Row, while cess deposits were recorded from Irishtown/Brennan’s Yard. The site at Parliament Street, which once housed the thirteenth-century Grace’s Castle, later became a gaol in the sixteenth century before its conversion to a courthouse in the eighteenth century. The excavation revealed numerous refuse medieval pits, cesspits, a wood-lined cesspit and long, shallow linears comprising domestic debris and cess material (Pl. II). The programme of environmental analysis from this site included an assessment of the plant macrofossils, insect, pollen and wood remains, and is the most extensive and comprehensive environmental project undertaken for medieval Kilkenny to date.

FIG. 2—Location of sites in Kilkenny City, Co. Kilkenny (after John Bradley, ‘The early development of the medieval town of Kilkenny’, in William Nolan and Kevin Whelan (eds), Kilkenny: historical and society interdisciplinary essays on the history of an Irish county (Dublin, 1990), 63–74, Fig. 3.1).

PL. II—Left: medieval levels at Parliament Street, Kilkenny; top right: series of linear medieval ditches at Parliament Street, Kilkenny; bottom right: medieval wooden-lined cesspit at Parliament Street, Kilkenny. (Photos: Arch-Tech Ltd.)

Daily fare of starchy staples

Crop harvest and cereal-based products

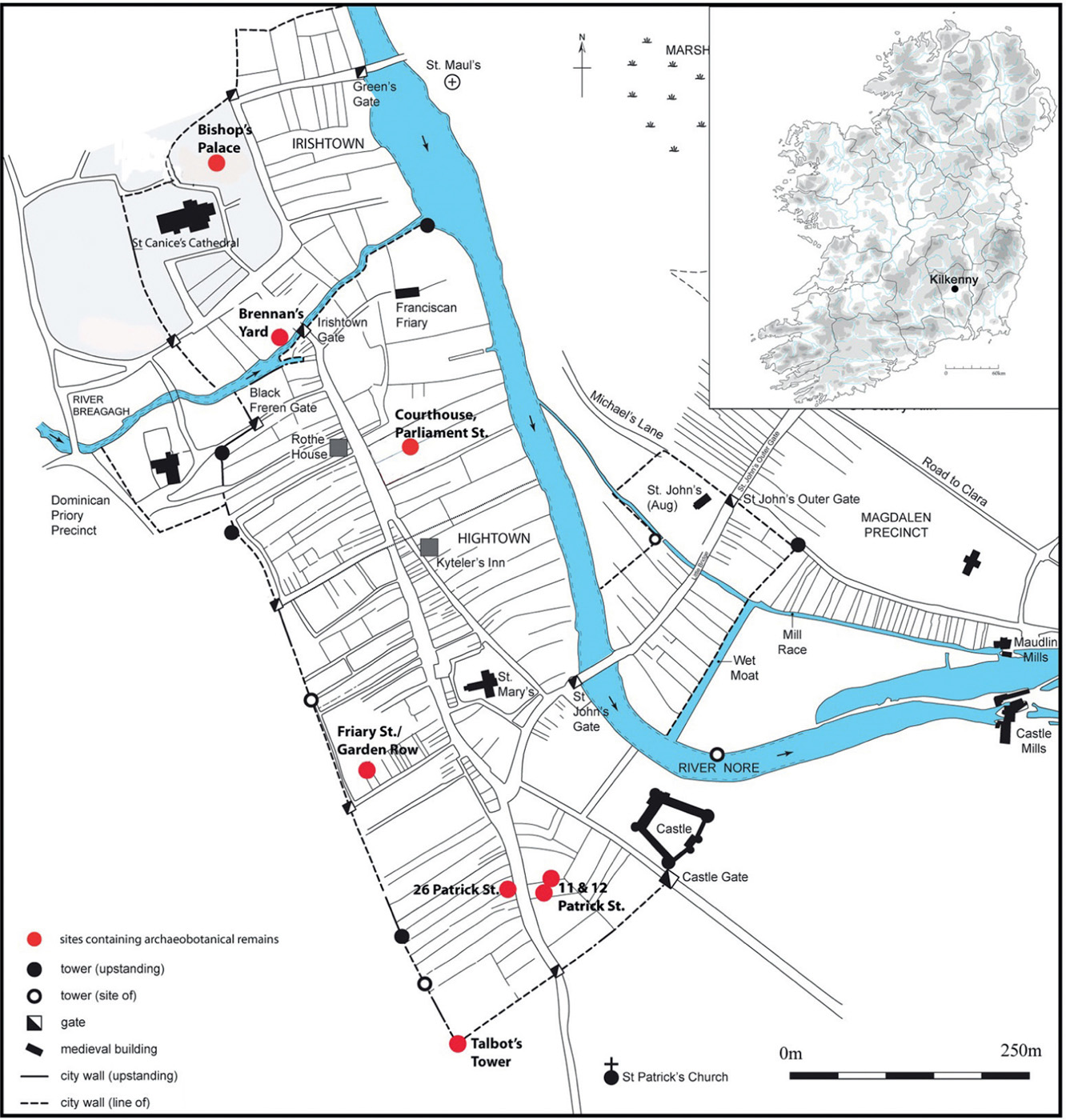

Irish texts dating from the early medieval period to the later medieval period refer to a well-balanced and healthy diet.28 This diet comprised bread and milk, providing the main source of carbohydrates and proteins required by the body. Cereals were the principal food consumed from the early to the later medieval period primarily through pot-based dishes, ale and breads29 and this differed considerably from person to person. The documentary evidence30 provides extensive information about cereal-based products and this is supported by the growing corpus of archaeobotanical evidence from Irish archaeological sites.31 Cereal remains (grains and chaff), including other field crops, such as legumes, commonly survive on archaeological sites in charred form as a result of exposure to fire. The frequency with which they appear to have been exposed to firing events ensures their relative ubiquity and abundance on archaeological sites. Wheat, oat, barley and rye were all typical crops cultivated during the medieval period, but vary in frequency and composition depending on location, environmental conditions, cultural preference and use (Pl. III).

PL. III—–Charred macrofossil remains of cultivated cereals and pulse crops recorded from medieval archaeological sites in Ireland. Wild radish is a wild plant often recorded with cereal crops in archaeobotanical assemblages. (Photos: Susan Lyons.)

The archaeological evidence for crops on urban sites is surprisingly less than expected32 especially considering the frequency of cereal remains in charred assemblages on rural sites.33 One reason for this may be the plant remains which survived the different stages of food preparation. Since large-scale flour production was carried out in mills located primarily in the rural hinterland, one would expect cereal remains to be a rarity in urban contexts. It has been surmised then that their presence in towns is perhaps for animal fodder, fuel, seed corn or as a consequence of transit.34 The ubiquity of charred cereal remains on rural sites is particularly associated with features such as kilns and hearths, which can provide insights into crop-processing techniques and potentially cultivation at a local level, something often missing from historical records. The evidence for waste products and cooking debris is also more prolific at these sites, since open features such as ditches, pits and gullies were frequently used as a dumping ground for this material. In contrast, crop-processing within urban centres is more difficult to define and therefore interpret, since the character of rural and urban settlement and their use of space clearly differed. It must be stated, however, that the presence of cereal remains does not in itself indicate if a site was a producer (involved with crop cultivation) or consumer (receiving crops in a processed or semi-processed state) site.35 While rural settlement would have engaged in producer/consumer activities, it is most likely that urban communities were largely end consumers where evidence for cereal remains reflects predominantly consumption.

Grain-based products, such as breads, porridges and gruels were consumed by grinding the grain into flour or meal. Evidence for this in an urban context is found in faecal remains from cesspits at Fishamble Street, Dublin,36 Arundel Square, Waterford,37 and similarly at Coppergate in York38 which contained frequent fragments of cereal spermoderm (bran), with wheat/ rye tentatively identified from Dublin and Waterford. During the medieval period the primary use of grain was in bread-making, with most being baked from wheat flour.39 Wheat, in contrast to oat and barley, has a high gluten content, which determines flour quality and is an essential component for producing leavened bread.40 The superior quality of wheaten flour was more desired than the heavy flat coarse breads of oat and barley,41 which were viewed as inferior varieties.42 Wheat was often thought of as a luxury food of the higher social classes in early Ireland43 but became a staple crop from the thirteenth century as part of the Anglo–Norman system of intensive cereal production.44 Monastic/penitential bread, a common staple of the Benedictine rule of the Cistercians and Augustinian orders required coarse flat bread to be consumed.45 This was made from an inferior flour of barley, oats and pulses baked on ashes or made into dried biscuits.46 Only the finest wheat flour was permitted on Sundays and in the making of the wafer-thin sacramental Host.47 Despite the documentary evidence for the use of wheat in bread-making, the recovery of whole wheat grains from urban sites can be low.48 This is based on the assertion that bulk crop-processing, including milling wheat for flour, was a large-scale operation carried out under seigneurial control on rural demesnes.49

While wheat was recorded from most urban medieval deposits, values were generally lower from Hiberno–Norse occupation layers compared to later medieval phases. Instead, barley (six-row) and oat (common, bristle and wild varieties) dominated assemblages from Viking and Hiberno–Norse sites in Dublin, Cork, Waterford and Wexford.50 With a notable increase in wheat values from thirteenth-century occupation layers in Wexford and at a number of sites in Dublin,51 oat predominates from similar phases in Waterford and from Washington Street and South Main Street, Cork.52 Evidence for wheat was low from Cashel, however, it is frequently recorded along with oat from Kilkenny, most notably from a series of thirteenth/fourteenth-century refuse pits on Patrick Street53 and a later medieval/post-medieval crop-drying kiln on Friary Street.54 This trend follows a similar pattern emerging from other archaeobotanical datasets in Ireland, where wheat rarely dominants on sites predating c. AD 1200,55 but more prevalent on late twelfth- and thirteenth-century settlements.56 It was documented as being grown by the Irish population during this period, however it rarely became part of their own diet, instead being used as payment of a tithe or rent to local landlords.57

While hulled wheat, such as emmer and possible spelt wheat have been identified from Friary Street, Kilkenny,58 and Friar Street, Cashel,59 identifications are tenuously based on grains rather than chaff. In the absence of cereal chaff, it can be difficult to distinguish between different species of wheat in the archaeological record.60 In most instances, however, it is naked or freethreshing wheat, such as bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) which are recovered from Irish medieval sites, with some evidence for the bread/club and rivet/durum variety (T. aestivum/compactum L.; T. turgidum/durum Desf.).61 Despite the sheer volume of cereal grains being identified from medieval sites in Ireland, spelt wheat and rye are still grossly under-represented, compared to archaeobotanical records from the Continent.62 In Britain, there is a shift from spelt wheat to naked wheat recorded in Anglo–Scandinavian and later medieval sites, while rye values decrease during this time.63 This increase in naked wheat could be more cultural than environmentally driven. Taste may have been one factor for wheat preference in different locations. Bread and spelt flour is of high quality, producing a light, white bread, which was favoured by northern and western European regions, while rye bread, common in more easterly areas, was flat and coarse.64

From a practical view point, naked wheat requires less processing than hulled wheat, where the grain is difficult to detach from the outer glumes or hulls. In addition, spelt wheat has a lower yield per acre than bread wheat, which would make is less commercially viable.65 Being less labour intensive, naked wheat would therefore produce a high and stable yield, more suited to the rigors of Anglo–Norman agriculture practices. This could go some way to explaining its frequency in some later medieval archaeobotanical assemblages. More locally, archaeobotanical research in Ireland is revealing that higher incidences of wheat are recorded from sites in Leinster compared to Munster66 and the data from urban sites in these regions also supports this pattern. This perhaps reflects the breadth of Anglo–Norman settlement within these areas and that cultural preference was also a significant factor in crop variation at different geographical locations within Ireland.

Crop-drying in an urban context was not unusual as kilns and a possible oven were found in back yards of medieval properties on Peter Street and Back Lane, Waterford. Kilns generally represent large-scale crop-drying, so their presence could reflect a commercial activity, such as baking or brewing. This activity is characterised by the number of bakehouses recorded in Dublin67 in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and in breweries associated with religious houses at Holy Trinity and Christ Church Cathedral and Dublin Castle.68 Bread-baking in Cashel is also documented where a bakehouse is mentioned in a charter dating to 1230.69 In Kilkenny, the grain from the kiln at Friary Street was interpreted as evidence for brewing. A mixed composition of predominantly wheat and oat displayed signs of germination, a feature of malted grains.70 While there is some documentary evidence from Dublin that wheat was used in ale-making, oat was the preferred grain for malting and brewing, certainly up until the fourteenth century.71 Oat was cheap and widely available and used in the brewing of inferior ales, while wheat produced a more superior brew. The preponderance of oat identified from archaeological deposits in Cashel may also signal local ale-making, especially since brewing was a historically attested activity within the town, with some 38 practising brewers recorded.72 In contrast to the brewing industry in England, barley was the preferred brewing grain at this time, seen perhaps as being superior to oatbrewed ales, as reported by English travellers to Ireland in the seventeenth century: ‘scarce outside of Dublin and few other towns will you meet with any good beer or any reasonable bread for your money, only you may have some raw, muddy, unwholesome ale, made solely of oats’.73

Another supporting feature for potential brewing at Friary Street, Kilkenny, was the high frequency of cereal chaff and straw present. The use of certain types of fuel in a kiln permeated various flavours into the malted grain, many of which were considered undesirable. While most brewers used wood, straw imparted the least taste, which helped to produce a clean-tasting ale.74 Since ale was produced without the use of hops, it spoiled quicker particularly ales of ordinary strength. This feature would have greatly affected the trade and transport of ale, prompting ale-making industries, such as those associated with religious houses, to dry malted grains locally. Valued for its nutritional and sustaining abilities,75 ale became a staple in the diet of medieval people, including penitential orders,76 so demand was high.

Whether beer was being brewed in Ireland at this time is uncertain. The practice of brewing beer involves the use of hops and in Britain the transition from unhopped ales to hopped beer is documented from the fourteenth century.77 Archaeological finds of hops do occur but are infrequent and it is difficult to ascertain if they represent a cultivated variety.78 Hops were included in gardens, although they were also grown as a specialist field crop.79 Earliest archaeological finds for hops were recovered from tenth- and eleventh-century deposits at Hedeby, Germany, from Birka, Sweden, and Svendborg, Denmark,80 eleventh- and twelfth-century deposits at Novgorod, Russia,81 and from Anglo–Scandinavian York,82 suggesting that hops came into Northern Europe as early as the tenth century. Flavourings such as sweet gale and bog myrtle were found alongside hops from York, Novgorod and fourteenth-century deposits in Aberdeen,83 however no such combination has been recorded from Ireland to date. The identification of a hop seed from a later medieval cess deposit at Irishtown/Brennan’s Yard84 is an interesting find, since hops were not native to Ireland. At Parliament Street, Kilkenny,85 evidence for hop/hemp pollen was identified from a medieval cesspit on the site, possibly through human waste or domestic rubbish, suggesting it may have been growing locally. While it is difficult to separate hop from hemp pollen,86 the presence of the hop seed from Irishtown/Brennan’s Yard helps to confidently assume that the pollen could have derived from hops. From this evidence, it is possible to infer that hops were growing in urban gardens in Kilkenny and potentially being consumed. In addition to flavouring beer, hops had medicinal uses such as treating skin ulcers and inflammation.87

Since bread and ale were considered the two staples of life, the majority of grain and grain-based products were brought into the towns and sold at city markets for this purpose.88 The purchase of whole grains would also have been important in order to facilitate food supplies through the winter, especially for urban communities, who depended on seasonal produce. Oat was the most prominent grain recorded from both archaeological and documentary evidence during the medieval period.89 Since oat could tolerate difficult growing conditions and damp climates, it became the primary foodstuff for all classes, although it was often associated with poorer communities.90 Oats would have provided more nutrition than wheat or barley, having a higher protein, fibre and amino acid content than any other cereal.91 The recovery of whole grains from occupational layers on many urban sites in Ireland indicates that cereals were stored in towns without having to be milled. One such example is Friar Street, Cashel,92 where a mixture of crops and pulses were recovered from a fourteenth-century burnt structure,93 representing the remains of grains stored for domestic consumption. The presence of oat, barley and wheat in this context may be incidental rather than contamination. Growing a mixed crop, known as dredge or maslin, was well documented in England94 and suggested by Geraghty95 for crop assemblages in Viking Dublin. Sowing mixed crops together had an economic incentive, since it ensured the probability of a decent yield. Interestingly, the oat and barley grains from Cashel still had hulls and chaff attached, while the wheat grains did not, evidence that oat and barley were not fully processed. Oat chaff and a variety of arable weed seeds were also plentiful from samples at Chapel Lane, Cashel; Parliament Street, Kilkenny; and medieval Waterford96 suggesting that oats were being processed within the town or were being stored in a semi-clean state. This can be carried out in a domestic context quite easily, using a quern stone, known as ‘shelling’ or ‘graddaning’, where the grains are parched in a pot over a fire or rolled with hot pebbles in a basket.97 Oat had a number of different uses, which depended on availability, use and personal taste. It could be baked into flat cakes, or added to pottage and stews and malted and brewed into inferior ales, as discussed. It was frequently used in making porridge rather than bread as it was easy to digest, and simple and quick to prepare and cook, compared to barley.98 Porridge was a common dish in the diet of children in medieval Ireland,99 but oatmeal made of water and buttermilk was viewed as an inferior dish and considered an unhospitable dish to serve to travellers.100 Since oat was also commonly used for horse fodder (grain and chaff),101 its preponderance in the archaeological record suggests it was being cultivated for both human and animal consumption. Animals kept in urban areas would have required a constant supply of fodder so unprocessed crops could reflect areas where there was a market for fodder goods, such as poorer consumers and urban hinterlands.102 Food storage was essential to a stable urban economy given that most food plants, including staples such as crops, were produced seasonally in temperate regions. The ability of cereals to be stored for long periods of time added great value to maintaining a balanced diet throughout the winter. A cache of whole grains was therefore a versatile resource, providing a household with much-needed ingredients for a variety of food and liquid dishes as well as feed for animal stock.

Other field crops—peas, beans, lentils and flax

Other field crops recorded from medieval Ireland are pulse crops or legumes. Traditionally, they were used primarily for animal fodder, especially vetch103 and as a foodstuff in times of famine or a bad harvest.104 The historical evidence for peas, beans and vetches is a mention in early medieval Irish law tracts of the eighth century and they are well documented in thirteenth and fourteenth-century manorial accounts for food liveries, maintenance agreements and government purveyance records.105 In fourteenth-century Dublin, 50% of peas and beans recorded from the manor at Clonkeen were given to servants and the remainder were sent to Glasnevin and Grangegorman to be used in horse bread.106 If Clonkeen is typical of the settlements in the Dublin region at this time, then legumes played an important part in the diet of the poorer classes. Most legumes are toxic in their raw state (have a negative effect on absorbing nutrients in the body), so they require soaking, fermenting or sprouting in order to ensure that they are safe to eat. Once dried, they could be stored easily for the winter months and were a good source of fat, starch, protein and Vitamins B, C and K. Between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, Spencer’s survey of historical documents pertaining to foodstuffs suggests that dried peas and beans were commonly made into flour or as part of a pottage dish consumed by both the rich and poorer classes107 and archaeological evidence for this practice was recorded from Viking Birka.108 ‘Pottage’ by its very meaning translates to: that which is cooked in a pot’, a common stew-like dish consumed by both the rich and poorer classes.109 This dish could be made from a variety of different ingredients ranging from the simplest plain-boiled cereal gruels to more luxurious stews which included meats, fish and vegetables.110 Beans were commonly used in sweet dishes, such as puddings and are mentioned in many medieval recipe books of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.111

The presence of pulse crops in the archaeological record, however, is less impressive and they rarely survive, possibly as a result of taphonomic factors.112 Their seeds do not preserve well in waterlogged conditions, especially if ground into flour and since their processing does not require them to be dried, their chances of becoming charred is infrequent. Horse/broad bean and probably field pea were cultivated and eaten in Viking Dublin dating from the eleventh century.113 In medieval Waterford, charred field pea fragments were recovered from deposits dating from the eleventh to the thirteenth century114 and from thirteenth/fourteenth-century deposits in Drogheda, Co. Louth. Their frequency in the archaeological record increases from the thirteenth century115 coinciding with the arrival of the Anglo–Norman population, probably as part of their crop-rotation system.116 Both peas and beans were also recorded charred from medieval deposits associated with cess material, refuse pits and occupational layers at Cashel and Kilkenny. Their occurrence in kiln deposits from Friary Street, Kilkenny,117 indicates that they were being dried locally prior to storage in seed form. Storage in a domestic context, alongside other whole grains, as in Friar Street, Cashel,118 represents a cache of foodstuffs for long term use possibly through the winter. As well as cultivated legumes, ‘wild’ legumes were found at many medieval sites in Ireland, particularly vetches (Vicia spp.). While there is no documentary evidence for the cultivation of vetches during this period, there are extensive historical sources for their cultivation in medieval England, principally as fodder and also as famine food.119 It has been argued that by the fourteenth century, the scale and distribution of vetch cultivation on some English demesnes signal their status as a significant field crop.120 This also corresponds with the earliest accounts of vetches being used on a large scale to feed draught animals.121 It is difficult to establish if vetch remains recovered from the Irish archaeological record represent cultivated produce or weeds inadvertently harvested with cultivated legumes, or indeed an uncultivated plant gathered for consumption. Some of the largest vetch assemblages to date (in excess of 100 charred seeds) have been recovered from later medieval settlement sites at Boyerstown, Co. Meath,122 and Busherstown, Co. Offaly.123 The absence of chaff makes it difficult to identify these seeds to species, however based on the size of the seed and the length of the hilum (seed scar), Vicia spp. predominates, with lesser incidences for Lathyrus spp. Similar mixed vetch assemblages have also been recorded from later medieval deposits at Carrickmines Castle, Co. Dublin,124 and the Cistercian Abbey at Bective, Co. Meath.125 Vetch seeds are recovered together with other cultivated legumes and cereal crops from kiln and hearth deposits and as refuse debris in pits, diches and gully features from these sites. While this indicates that they were dried with mixed crops, potentially to be used in grainbased produce, the distinction between human and animal product is still under-researched. While much is still unknown about the use of vetches in the medieval diet, such assemblages should still be considered when interpreting medieval food economy in the context of other cultivated crops and food plants.

Peas and beans were planted in late spring for harvesting in August or September after they had dried in the pod. While there is documentary evidence for cultivation on large rural demesnes126 as a cultivated field crop, it is unknown if they formed part of an intensive cropping regime.127 Other than a foodstuff, legumes have the ability to fix nitrogen in soils, thus making cultivation plots more productive in the long term.128 Wheat occurs frequently on Irish archaeological sites were legumes are also present,129 which is interesting because wheat is a rather demanding crop that requires good-quality nitrogenous soils. Recent research in crop-rotation systems has demonstrated that planting legumes in order to increase crop yields can take many years.130 The apparent association between wheat and legumes in Irish archaeological deposits requires more careful attention, and perhaps further research before it can be determined if legumes were indeed being cultivated to help to improve crop yields.

Despite their low frequencies in urban contexts, there are archaeological signals for legume storage and possible cultivation at a local level. One biological indicator for their presence on site is the bean weevil (Bruchus sp.), a product pest found in stored peas and beans which was identified in cess pits from Parliament Street, Kilkenny,131 and Temple Bar West, Dublin.132 Pollen associated with the pea family (Fabaceae spp.) was also identified from the cesspits at Parliament Street, Kilkenny;133 a potential indicator that legumes were growing on a small scale in urban gardens. While these plants would have been very beneficial at a time when grain was in short supply or after a poor harvest,134 it must also be acknowledged that factors such as seasonality and cultural preference would also have determined how and when legume crops were consumed.

Lentils are extremely rare from Irish archaeobotanical assemblages and to date have been recorded in charred form from just a few medieval sites, namely Clonfad 3, Co. Westmeath,135 and Naas, Co. Kildare,136 although their contextual integrity is ambiguous. The largest lentil cache recorded in Ireland to date was identified from a post-medieval pit at Patrick Street in Dublin.137 While no documentary evidence exists for the cultivation of lentils in Ireland, they are found alongside other pulse crops, which suggest that they may have been grown as part of a mixed legume crop in medieval Ireland. It is also possible that these represent imported crops, as thought to be the case for contemporary lentil finds in Britain.138

The presence of flax from medieval sites adds to the diversity of crops cultivated in medieval Ireland. The cultivation of flax would have provided linen obtained from the stalks by retting, animal fodder from the leaves and oil from the crushed seeds, which had uses in cooking and lighting.139 The presence of flax in cesspits, along with other cess indicators, such as cereal bran, fruit seeds, fish bone and insect ova is a good indication of food debris.140 Linseed was eaten with grains and pulses in breads and stews as archaeological evidence from Viking Birka141 and Coppergate142 can attest. Evidence for flax, together with other food plant remains was recorded from eleventh-century cess deposits at Fishamble Street, Dublin,143 a thirteenth-century cesspit from John Dillon Street, Dublin,144 Waterford and South Main Street, Cork.145 It was also identified from other thirteenth and fourteenth-century sites in Dublin, Cork and Wexford,146 however, its status as a foodstuff is more difficult to ascertain. Its presence alongside cherry and sloe stones, blackberry pips and a grape seed from thirteenth-century refuse deposits in Chapel Lane, Cashel,147 hints at potential food debris, as the seeds were crushed in some cases. While documentary evidence for flax cultivation in the medieval period is rare, later medieval sources from England suggest that it grew as a garden crop, indicating small-scale cultivation on individual holdings and in gardens.148 Flax-drying may have taken place at Friary Street, Kilkenny,149 along with pulse crops, which could imply that it was growing in urban areas and being stored in seed form. Flax would have grown well and produced higher yields on smaller plots where nutrient-rich loamy soils from organic debris were common.150

‘To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose . . .’: seasonal contributions to medieval diet

Written evidence for the consumption of fruit, vegetables, nuts and wild plants in the medieval period is largely under-represented and as Christopher Dyer points out, is often dismissed by historians as a marginal or trivial aspect of the medieval diet.151 Despite the scarcity of horticulture practices in medieval documents, reference to gardens and their produce can be found in many of the later medieval deeds, charters, household accounts, manor surveys and seigneurial records.152 Gardens and gathered wild produce did not constitute the mainstay of food production but provided the population with a proportion of their diet on a seasonal basis. The consumption of many plant-based foods (fruit, nuts, vegetables, herbs and wine) during the medieval period was subject to seasonal fluctuation. Functional and economic factors such as weather, cycle of crop growth, and the storage and distribution of commodities also played a part in affecting food supplies.153 Cultural factors must also be considered, where religious calendars, such as Christmas and Lent, would have impacted on diet and food preferences.

The value of gathered foodstuffs and garden and orchard produce provided both a quantitative and a qualitative element to the medieval diet. In times of food shortage, these natural foodstuffs played a vital role in food production on a seasonal basis. Indeed, this probably led to surplus food supplies, which may have been sold to less self-sufficient consumers, such as the lower classes and urban occupiers. These foodstuffs also supplied people with much-needed nutrition, being a good source of vital vitamins and minerals, which aided balanced eating. The development of an urban market economy and an increase in trade during the later medieval period would have inevitably diversified foodstuffs providing a wider spectrum of fruits and vegetables to a greater number of people.

Historical sources from Ireland document the presence of a vegetable garden outside settlement enclosures as early as the seventh and eighth centuries AD.154 This is supported in the archaeological record, where small enclosures excavated at a number of early medieval sites, such as Cahercommaun, Co. Clare,155 and Boyerstown and Castlefarm, Co. Meath,156 have been interpreted as possible garden plots. Evidence for artificially deepened garden soils has also been identified from early medieval ecclesiastical sites, namely Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly, and Illaunloughan, Co. Kerry.157 The function of gardens whether in rural or urban areas was to supply the household with seasonal additions to their diet. From the thirteenth century large secular and ecclesiastical estates would have had well-stocked managed gardens. The lower classes and urban households had access to a small plot for growing vegetables and fruits and would have engaged in small-scale horticulture to facilitate their own dietary needs.158 In medieval Britain, estates bordering towns were growing garden and orchard produce, which provisioned the urban markets with local fresh supplies.159 It has also been suggested by Dyer that horticulture was being practised more in urban areas than rural settlements.160 This would mean that towns were more self-sufficient in providing themselves with garden produce and did not engage to a great extent with the surrounding agrarian economy. Interaction between towns and rural settlement should be reflected in the archaeological record, however, the physical plant remains may not survive to address these questions. Furthermore, preservation conditions may obscure the picture of garden cultivation on agrarian sites, producing a view that garden history is linked to social class and urban environments. Using the current archaeological evidence, more research is needed in the garden plant spectrum from rural settlements in order to assess their place in the medieval food economy. While archaeobotany can provide evidence for the presence of cultivated, wild and collected food plants from urban areas, contextualising this data can sometimes prove difficult, especially in the absence of defined features or well-stratified contexts. It should not be assumed that samples represent in situ deposits. Long periods of occupation will produce multiple layers of middens, increasing the impact of residual and intrusive remains through mixing and disturbance. Identifying sites with limited occupation as well as with a prescribed use of space may yield the best results for interpreting urban food storage, processing activities and horticultural practices.

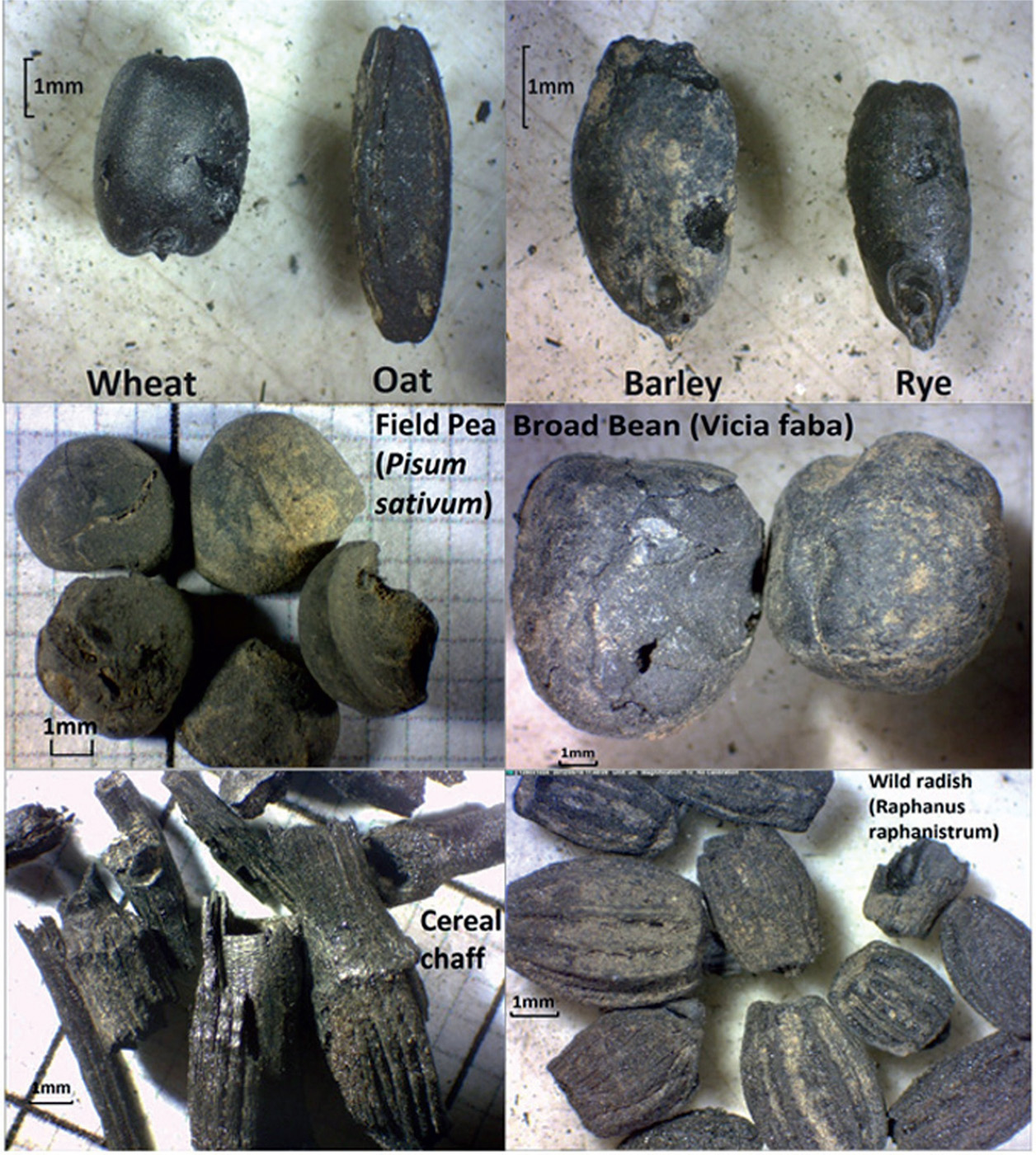

In the archaeological record, the differential preservation of plant parts is largely based on the part of the plant that has survived. Many non-cereal food plants are rarely exposed to fire and are more likely to be found in wet, anoxic deposits. The edible parts of vegetables and some herbs are soft, so their survival in the archaeological record can be scarce. Food plants valued for their leaves and roots are often under-represented in medieval archaeological deposits as they are generally harvested before the plant goes to seed.161 In contrast, seeds of herbs and wild plants—where the seed was the part used— fruit stones and nutshells can be over-represented since their robust woody structure ensures that they survive longer (Pl. IV).162 Even when ‘wild’ plant seeds are recovered in charred form, they are cautiously interpreted and more often dismissed as arable weed intrusions or fuel debris. One such assemblage from thirteenth/fourteenth-century kilns and a well at Clonfad, Co. Westmeath,163 contained a plethora of wild plants, which historically have both culinary and medicinal qualities. While their presence in these features was interpreted as being the remains of crop-processing waste, perhaps more attention should be given to these plants in the context of other known cultivars and to the possibility that they potentially represent food plant debris rather than crop contaminants. One problem with interpreting vegetables is that they may derive from native wild plants and differentiating cultivated varieties from their wild relatives can be difficult.164 Their presence in contexts such as cesspits and deposits containing domestic waste together with a series of other biological indicators should also be considered and appropriately evaluated in order to help to establish if they indeed derive from food debris.165

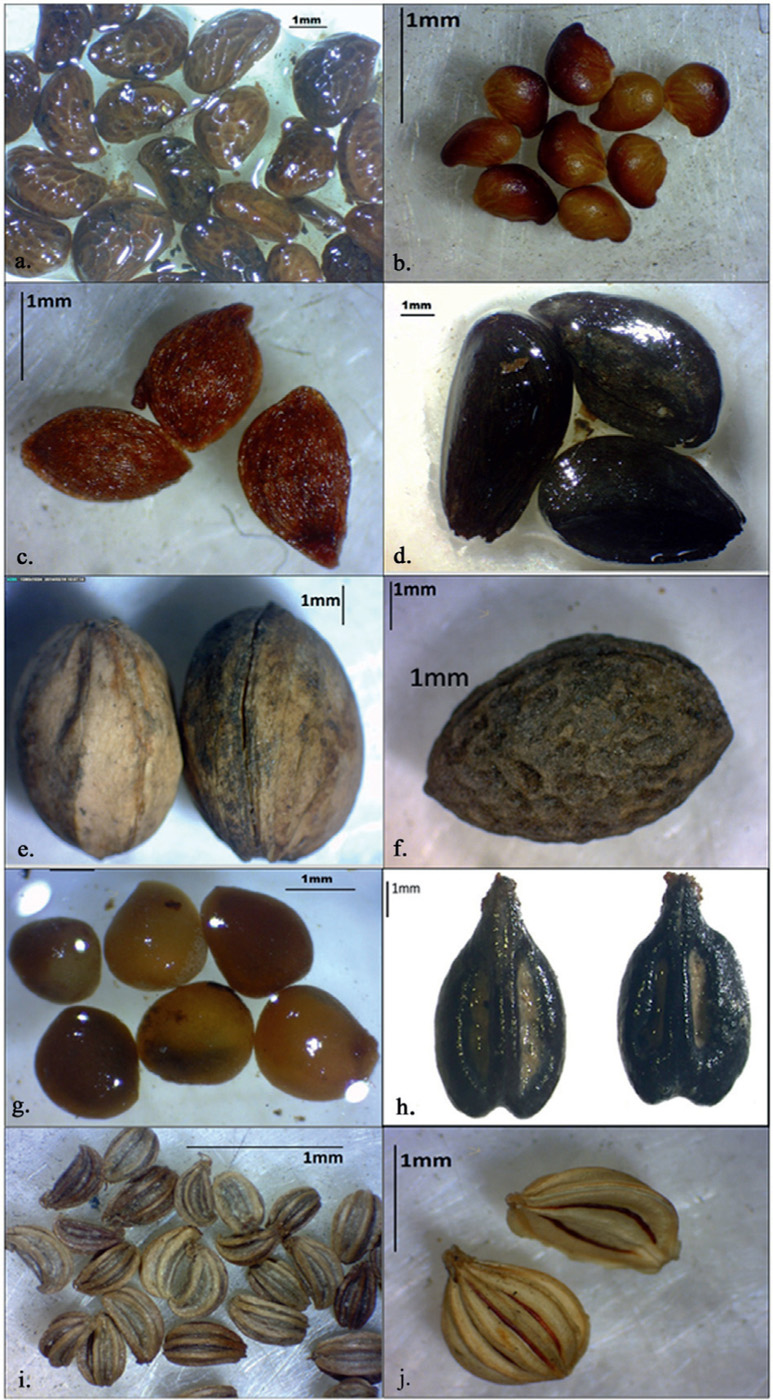

PL. IV—Examples of typical fruits and herbs recorded from medieval archaeological sites in Ireland. (a) blackberry/bramble/raspberry (Rubus fruticosus/idaeus); (b) wild strawberry (Fragaria vesca); (c) bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus); (d) apple (Malus spp.); (e) wild cherry (Prunus avium); (f) blackthorn/sloe (Prunus spinosa); (g) fig (Ficus carica); (h) grape (Vitis vinifera); (i) celery (Apium graveolens); (j) parsley (Aethusa cynapium). (Photos: Susan Lyons.)

Fruits and nuts

One of the most ubiquitous food plants recovered from urban sites, especially from cesspits and cess deposits are fruit remains.166 Their abundance is partly the result of the high seed content in some fruits, such as blackberry and strawberry but also their robust woody structure can survive well in these environments.167 The dominance of fruit seeds has coined the expression for this typical assemblage as a ‘medieval fruit salad’.168 Smaller pips are usually swallowed whole with the fruit, such as blackberry, raspberry, strawberry, apple, grape and fig, so they are most likely the remains of food which had passed through the human digestive tract unaltered. Larger fruits such as cherry and plum may be more difficult to swallow and would have been discarded upon eating, so may not be associated with excrement as much as the former fruits.169 Some of the earliest urban medieval evidence comes from eleventh-century pits at Fishamble Street and Winetavern Street170 where a wide range of fruits were identified. Cherries, sloes, rose, rowan, blackberry, bilberry, apple and haws were commonly recorded in seed form, with apple endocarp also present from Fishamble Street.171 A large mass of faecal matter from Winetavern Street contained abundant sloes, blackberry and strawberry seeds, representing direct fruit consumption.172 Similar fruit assemblage in varying quantities features prominently in later thirteenth and fourteenth-century cesspits and cess deposits from Chapel Lane, Cashel; Kilkenny; Cork; Drogheda; Athenry, Co. Galway; and Waterford.173 With the exception of an early thirteenth-century deposit at High Street, Dublin,174 evidence for bilberry seems confined to earlier Hiberno–Norse occupation in Dublin and Wexford175 similar to Anglo–Scandinavian sites in England, such as Coppergate.176 Whether this signifies a cultural preference in the diet of Viking settlers is unknown. Geraghty makes the point that bilberries grow some 10km south of Dublin City, so effort was required to transport them into the town.177

Fruit species such as bilberry, bramble, blackberry, haws and elderberry and possibly raspberry were scarcely mentioned in the historical record probably since they were gathered wild. The historical evidence suggests that they were being cultivated from the sixteenth century.178 Apples were the most frequently mentioned fruit in both the early Irish texts and later medieval sources.179 Crab/wild apple is native to Ireland and would have provided a good crop of small sour apples.180 The historical records clearly distinguish between sweet, fragrant and wild apples, and in the Betha Brigde from the Book of Lismore, apples were stored in a haggard and given as prized gifts.181 Varieties of apples in later medieval Ireland may have included costards, pearmains and bitter-sweets, the latter being used for cider-making.182 Pears were rarely recorded prior to the Anglo–Norman period, and varieties included wardens, sorels, caleols and gold knopes.183 They were usually cooked and eaten in puddings and pies.184 The use of fruit as relishes and as an accompaniment to dishes is well documented in the early medieval lives of the saints and in the Aislinge Meic Conglinne.185 An eighth-century text An Irish penitential, mentions a herbal broth given to the sick known as brothchán.186 Brothchán was made with oatmeal and herbs and many texts refer to the health benefits of this dish.187 This dish was often served with the addition of relishes on Sundays. These relishes included honey or assorted seasonal fruits, an early form of muesli perhaps.188 It was also viewed as a luxury dish, and was used by penitential monks in lieu of bread and water during times of fasting.189 In addition to apples, other fruits used in this muesli’ dish included blackberries/ sloes/mulberries/hazelnuts and other nuts. Aisling Meic Conglinne mentions purple berries and a little sloe tree, together with cabbage/kale and nuts.190 This implies that blackberries were stewed in gruel, a mix of oatmeal, honey, fruits and nuts which featured regularly in the diet of all classes.191 Despite the historical evidence for apples and pears, their presence in the archaeological record is surprisingly low compared to fruits such as blackberry and raspberry. While taphonomy may play a part here, it is also worth considering how different fruits were being consumed, processed and cooked, altering their physical remains and hence distorting their archaeological signal. For example, eating apples raw was frowned upon by medieval physicians, and common practice in England and the Continent was to press them into cider and verjuice (vinegar).192 In times of surplus supplies, they were also fed to swine.193

Nuts in the form of hazelnuts were commonly recorded in both the documentary and archaeological record194 and their importance in the early medieval diet is highlighted by the numerous historical references to them.195 They would have been gathered in autumn and suitable for storing through the winter. At Fishamble Street, the recovery of both whole and fragmented nuts suggests they may have been consumed as whole nuts and ground into meal, known as maothal.196 While well documented as a foodstuff in medieval Ireland, the ubiquity of hazelnut shells from the archaeobotanical record can perhaps be misleading. A good source of Vitamins A and K, they were certainly a nutritious addition to any dish, however, taphanomy must be considered when discussing how certain fruit and nut remains survive and they should be interpreted with caution.

For fruits and vegetables to be enjoyed out of season, they had to be preserved, generally by drying and, depending on the foodstuffs, using honey and brine.197 Food storage was essential to a stable urban economy given that most food plants, including staples, are produced seasonally in temperate regions. Storage of other plant produce will have been straightforward (hazelnuts, walnuts, linseed, field beans, peas, garlic, parsley and celery) would have been stored dry and could survive for many months. Apples could be harvested slightly later than many other fruits, and were easily dried, which provided a nutritious food source during the winter months.198 Soft fruits, such as raspberry, blackberry, bilberry and strawberries, could only survive storage beyond a day or two, cooking them would ensure that they kept for several days, but longer term storage would require preserving them in honey or in ferments.199 Raspberries, elderberries, blackberries and bilberries were not cultivated because they grew quickly and profusely in wild thickets. Cultivation would not have increased their fruit production either making for an unprofitable return.200 Fruit and berries picked in late summer, could however be preserved in jams and preserves out of season, which can make seasonality difficult to discern in some cases. At Temple Bar West, the fruit stones and insect remains recorded successfully charted the seasonal use of a cesspit at the site.201 In a similar project, a pit from Parliament Street, Kilkenny,202 containing abundant cherry, sloe and blackberry represented seasonal fruit produce deposited in late summer or early autumn. At Chapel Lane, Cashel,203 a deposit of predominantly blackberry and bramble seeds could also reflect seasonal food debris. Haws ripened later in the autumn, and although tougher to digest, may have been eaten as a ‘last resort’ food in the absence of other fruits,204 which could account for their lower occurrence in the archaeological record. Not all fruit remains should be regarded as human food however. Elder tree stumps, for example, where identified in situ at Coppergate, evidence that they grew as part of the urban vegetation.205 Their seeds, therefore, would have entered deposits and become part of the archaeological record.

Evidence for fruit-processing was identified from High Street, Dublin, where the remains of an early thirteenth-century fruit press containing the macrofossil remains of cherry, plum, strawberry, fig and bilberry was found. 206 The debris was interpreted as fruit waste for fermentation, a common method of juice extraction documented in many European medieval sources.207 While juice content can be high (75%), it is a laborious task and may not have been used for large-scale juice production.208 Many religious houses, manorial estates and high-status residences were recorded as having a cider press so as to facilitate their own personal needs.209 This suggests, therefore, that the fruit press from High Street could have been providing produce for a wealthy or religious household.

In Winetavern Street, an eleventh-century pit containing an abundance of fruit debris (cherry, sloe, bilberry, blackberry, apple and haws) with pulp still attached, was also considered to be the waste remains of fruit-processing.210 Whole fruit stones of sloes and cherry identified from medieval Waterford and Parliament Street, Kilkenny, where plums were also identified, were both interpreted as being a possible by-product of food production rather than consumption.211 Parliament Street’s position adjacent to a market on High Street, Kilkenny,212 would have been at the centre of commercial activity in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Food-processing may have been one such activity carried out to facilitate urban demand, including the growing number of monastic orders, friaries and hospitals that were being established.213

The excellent preservation of fruit pulp from Fishamble Street214 and High Street could be the result of the fruit having been pickled in alcohol or acetic acid.215 Some fruits, such as sloes were quite bitter and difficult to digest. It is therefore unusual that they are one of the most ubiquitous fruits found in faecal matter or associated with cess material. Their abundance in the archaeological record therefore deserves some attention. It has been suggested that they are the remains of prunes, rather than sloes in their raw state.216 While prunes may have been imported from warmer climates, they could be easily kiln or oven dried—a process which is used in making acid fruit, such as sloes and crab apples more palatable.217 According to James Greig, this made them easier to digest and could explain the high incidence s of Prunus (cherry/sloes/plum) type species found in faecal remains. Documentary evidence details the juice of sloes, and sometimes of crab apples, in making verjuice.218 This unfermented acidic juice was commonly used as a preservant and, in cooking, it was added to sauces.219 The juice of sloes also had medicinal qualities.220 A seventeenth-century traveller to Ireland who required a remedy for an ailment documented its use: ‘. . . being troubled with an extreme flux . . . the syrup and conserve of sloes well boiled, after they have been strained . . . boiled in water until they be softened, and then strained . . .’221

While the preponderance of fruit stones from many urban pits and cess deposits suggests a diet rich in seasonal produce, it is very possible that these remains represent food-processing, in the form of fruit extraction for juices, preserves and verjuice, as much as direct foodstuffs. Such activities would have been carried out in late summer or early autumn when fruits were plentiful. This surplus of fruit stock may not have been so easily conserved, so converting it to juices and preserves would ensure its longevity. The versatility of verjuice as a common cooking ingredient would have kept demand for this condiment high and since sloes and apples were plentiful in season, both elite and non-elite households may have had access to this product or the makings of it. This could go some way to explaining the high incidence of sloes in the archaeological record.

It is also worth mentioning that during the medieval period, fruit consumption had a somewhat medicinal fervour and was classified on a sociological scale depending on dietetic considerations. This was borne out of the classical theory that food was categorised by energy patterns which effected general well-being.222 To maintain health and balance, certain foodstuffs were classified as amicable, while others could cause aggravation. For example, fruits such as plums, cherries, blackberries and grapes were ‘cold’ foods and difficult to preserve, so should be eaten at the beginning of a meal, and were considered unhealthy for the ill, the young and the elderly.223 It was believed that different fruits held qualities to treat specific conditions—bilberry was used for blurry vision; cherry and elder for coughs and colds; blackberry for stomach complaints; plum for indigestion; apple pulp was applied to swellings and smallpox scars; while strawberry juice was used to clean teeth.224

Herbs, vegetables and edible plants

Since the early medieval period documentary sources mention the use of vegetables such as leek, onion/garlic,225 celery and cabbage/kale as well as herbs like sorrel, cress and parsley.226 The importance of vegetables in the diet of the sick and ailing is repeatedly mentioned in the early documents. Celery is particularly valued, as it prevents sickness, relieves thirst and does not affect wounds.227 The frequency with which these plants are referred to in early medieval texts strongly implies that they may have been subjected to some degree of cultivation.228 Archaeological evidence for celery, watercress and cabbage/mustard/turnip, and garlic/onion seeds were also recorded from Hiberno–Norse and medieval Dublin, Cork, Waterford, Cashel and Kilkenny sites.229 Vegetative remains are unusual on archaeological sites, however, leaf tissue of the onion family and cabbage/turnip remains have been recovered from faecal remains in medieval York230 and Chester,231 but not in Ireland to date. Root vegetables such as carrot are cited in Aislinge Meic Conglinne,however archaeological evidence is scarcer. Wild carrot was identified from medieval Dublin232 as at Anglo–Scandinavian York233 but their status as a root vegetable is dubious. Other wild plants with ethnographic references include goosefoot or fat hen, sorrel, knotgrass, black bindweed, redshank, nettle and wild radish or charlock.234 Many of these were served as condiments with bread and seasonal foodstuffs.235 Early medieval documentary sources, such as the saints’ lives contain numerous references to the consumption of nettle and sorrel. A. T. Lucas postulates that nettles and charlock may have been a common feature in the diet of the poorer classes, especially in times of severe food shortages, and that this knowledge of famine foods may have been borne out of antiquity.236 Wild garlic and watercress also get a special mention in the twelfth-century poem Buile Suibhne,237 while cabbage, which features particularly in monastic diets, was frequently mentioned as a foodstuff in Aisling Meic Conglinne.238 During Lent, garlic/onion and celery were permitted and encouraged to be consumed as these would preserve other valuable food stocks, such as butter and salted meats.239

Sheep’s sorrel is also a common find from these sites and is documented as a salad ingredient and as a flavouring for fish.240 Cabbage/mustard/turnip was also present in Drogheda. Herbs such as fennel, dill and black mustard were recovered from Drogheda, Wexford and Kilkenny,241 while mint was identified from Dublin, Kilkenny and Cork.242 Seeds of marjoram were also present from mid-twelfth to thirteenth-century house deposits at Washington Street, Cork.243 Another common plant recorded from urban deposits in Ireland was yarrow. Although a wild plant, yarrow was grown for medicinal purposes in a vicar’s garden in Glasgow in the sixteenth century.244 In addition, dead nettle species, nettle, plantain, water bistort, cinquefoil and elder are other wild plants that were used in fifteenth-century herbal medicines.245 Some herbs grown specifically for their leaves, such as parsley, are also represented by their seeds perhaps from herbs gathered in autumn and dried. Since the seeds from many of these herbs provides their distinctive flavours, their occurrence in the archaeological record, especially in cess deposits suggests strongly that they were ingested.246

Fat hen and knotgrass were frequently recorded from Dublin, Cork, Waterford, Cashel and Kilkenny.247 Fat hen has edible leaves similar to spinach and was a common vegetable eaten in Ireland up until the eighteenth century.248 Another common wild plant recorded from urban deposits is nipplewort and while often interpreted as a weed of cultivation, may have been eaten in salads and used for treating chest complaints.249 It is possible that fat hen, knotgrass and redshank were being cultivated separately as food grains by the late medieval period,250 and their preponderance on archaeological sites collectively with known cultivars would certainly help to support this. They may have been ground into flour as flavour enhancers,251 used as a foodstuff to provide gruel or coarse bread for the poorer classes and as a supplement to grain when crop yields were low.252 Direct evidence for such consumption was found in Dublin, where faecal matter containing a high quantity of fat-hen seeds was recorded from eleventh-century occupation deposits at Fishamble Street, Dublin.253 Similar remains comprising the crushed seeds of knotgrass, fat hen and chickweed were identified from the pelvic area of a skeleton at High Street, Dublin, both of which were interpreted as the remains of a gruel dish.254 The term ‘condiment’ suggests that they were used to add flavour to bland or less palatable foods. Herbs were important in providing flavour to foods prepared with grains or dried legumes.255

Another common plant recovered with known foodstuffs from Cork, Dublin, Waterford, Drogheda, Cashel and Kilkenny in the medieval period was corncockle. A former cereal weed, it is now extinct in Ireland, however, its presence from a number of medieval cess deposits shows that it was consumed, possibly in a milled product like bread or flour.256 Corncockle was often processed with grains during milling probably because its seeds were quite large and may have escaped sieving. This species is also a farinaceous food, containing starch, so it would have been easily incorporated into flourprocessing.257 The remains found in Irishtown, Kilkenny, and Chapel Lane, Cashel,258 were generally fragmentary, suggesting that they were ground with cereals. Similar results have been obtained in faecal remains from Fishamble Street, Dublin,259 containing finely ground fragments of corncockle, probably as a result of being milled, consumed with cereal food and passed through the digestive system.260 Fragments of corncockle were also obtained from pit samples together with other cultivars and wild taxa at Waterford and Temple Bar West.261 Interestingly, this species contains the toxic githagin which can cause illness, such as gastrointestinal problems, when eaten in large amounts.262 Its presence in milled products could represent rudimentary cereal-processing associated with domestic rather than industrial milling,263 however, it may also be intentional, becoming an acquired taste or supplementing grain reserves during periods of bad harvest or food shortages. While it is difficult to establish herb cultivation through archaeobotany, their presence in deposits collectively with known food waste may not be incidental and needs more attention. Their documented use as culinary and medicinal ingredients makes them a credible foodstuff. A statistical approach to interpreting these datasets may help to highlight patterns in the records in order to establish the relationships between different plant communities and their cultivated counterparts.

Foreign foodstuff

Not all sources of garden produce were local, wealthier households enjoyed foods from the Continent and around the Mediterranean, imported in dried or preserved form, such as grapes, dates, figs, raisins, walnuts and almonds. In wealthy households in England, preserved fruits and nuts were often bought in preparation for the Christmas season and before Lent, as these luxuries were a relief to the mundane fish and cereal dishes consumed during this period, making dishes more palatable.264

While there is no direct evidence for grape-growing in medieval Ireland, it has been surmised that vines were grown by early medieval monasteries based on historical sources.265 Documentary sources describe a wine trade between Ireland and Biscay from the seventh century AD266 and early Irish texts make reference to wine imported from Bordeaux for the celebration of the Eucharist and church feasts.267 The establishment of the Norse towns in the ninth and tenth centuries stimulated trade, including the importation of wine, however, no archaeological evidence for grape dating to this period is known, despite finds in York and Norwich.268 The earliest evidence for grape to date has tenuously been recorded from an early twelfth-century pit excavated at Bishop’s Palace, Kilkenny,269 and from late twelfth-century (Hiberno–Norse) pit deposits at South Main Street, Cork,270 where fig was also identified. These finds were in low numbers so intrusive action cannot be ruled out, especially in light of later occupation, which was recorded at these sites. For the most part, archaeological evidence for grapes dates from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and finds have been recorded from Cork, Waterford, Wexford, Drogheda, Cashel and Kilkenny.271 Interestingly, this coincides with economic prosperity in these areas272 and the arrival of many European monastic orders.273 Grapes would have been imported as a luxury product probably in dried form, with wine or cork wood.274 Late medieval purveyance and administrative records contain abundant information on the wine trade to Ireland.275 This is also supported by the corpus of ceramic wares from excavations in France and England,276 a byproduct of the flourishing wine trade that existed between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. Most wine imported into Ireland, as in England would have been consumed within fifteen months of the grape harvest, so consumers would have been influenced by the agricultural cycle and trade on the Continent.277 In England, wine fleets arrived from Gascony in France in late autumn with households receiving their first barrels around November and then subsequently in spring.278 Throughout the year wine consumption would fluctuate depending on availability and religious occasion; with high wine consumption at Christmas, Easter and Corpus Christi,279 while reserves were lower prior to harvest in October and during Lent in February and March.

Another luxury item frequently recorded from urban sites is fig. While identified from Anglo–Scandinavian York, fig remains from archaeological sites in Ireland emerge at about the same time as grape in the early thirteenth century and often together in the same features.280 The fig recorded from late twelfth-century deposits at South Main Street, Cork, however, could be one of the earliest finds in Ireland.281 Based on their frequent recovery from sewage/ cess material, it has been suggested that figs may have been more accessible than other luxury foodstuffs at this time.282 Figs were the cheapest of all food imports from Europe, with the exception of the Lenten period, when demand for fruits and nuts, which were out of season, were higher.283 They would have been imported dried for long-term storage and records document that they arrived from Europe by the shipload.284 Furthermore, as a food known for its blood pressure lowering and blood thinning properties, they were eaten after bloodletting, a regular feature of monastic life.285 Whether they were consumed by all social classes is difficult to interpret, however, using the archaeological evidence alone. Fig, as well as grape, was recovered from largely domestic contexts in Wexford, Drogheda, Cork, Dublin and Waterford, where high status occupation was difficult to define in most cases. In Kilkenny, however, the presence of fig from occupation deposits at Grace’s Castle, Parliament Street,286 and a grape seed from Bishop’s Palace strongly signifies high status in both cases. In contrast, fig and grape were absent from Cashel, where more utilitarian settlement was recorded overall. While this could reflect the sampling strategies employed, it is possible that these goods were not as widely consumed here, due, in part perhaps, to their availability but also to distribution. Port towns had more access to foreign goods, so transport to inland centres would have been an onerous and laborious task. Kilkenny’s position on the River Nore would have eased the transporting goods from the port of Waterford for example, however, the absence of a river system through Cashel, made imports less readily available, which, in turn, may have increased their market value, allowing access only to those who could afford them.

Walnuts were another luxury imported into Ireland during this time, possibly from France or Germany.287 Archaeological evidence is rare, however, their recovery from eleventh and twelfth-century deposits in Fishamble Street, Dublin,288 and Waterford289 suggests that imports to Ireland may have been slightly earlier than fig and grape. Walnut macrofossils were also recorded in a thirteenth-century culvert on Winetavern Street alongside grape and in a sixteenth-century deposit with fig on John’s Street, Drogheda.290 The accumulating evidence for walnut macrofossils and pollen records on many British sites suggests that walnut was grown in Britain during the medieval period,291 and may have found a market in neighbouring Ireland. Unlike Britain, evidence for walnut in the pollen record is unknown for medieval Ireland, so it is difficult to ascertain if it was growing here. While ground walnuts, recorded as an ingredient in soups and sauces,292 may not survive in the archaeological record, the scarcity of walnut husks or hulls is more unusual, considering their robust nature. Since it is unknown whether walnuts were imported in their husks or not, it is worth mentioning that their hulls were commonly used in order to produce a brown/black dye, as recorded from Viking sites in Britain and Denmark (Hedeby)293 and in later medieval documents as a component of ink.294 This non-culinary use for walnuts could also account for their general absence from archaeological deposits, particularly features containing cess and faecal remains. On a more holistic note, walnuts were documented as a medicinal cure for gallstones and to treat ringworm.295

Archaeological evidence for almond is also relatively absent in Ireland and Britain, despite the numerous finds from European sites dating from the thirteenth to the eighteenth centuries.296 Almond shell recovered from Shrewsbury Abbey and from a drain in Plymouth are just a few published accounts from British medieval sites,297 while the only known archaeological finds from Ireland are from post-medieval Cork.298 Documentary evidence does exist, however, for almonds being brought into Ireland from the twelfth century, including the purchase of almonds in Kilkenny c. 1400.299 Historically, almond kernels were ground down into flour and milk.300 Similar to walnut, as a result, these would not be easily identified archaeologically. In addition to their use as a foodstuff, burnt almond shells produce a black pigment, which was highly prized by medieval painters301 and, while not historically attested may have also been included in animal feed.