The social significance of game in the diet of later medieval Ireland

School of Science, Institute of Technology, Sligo

[Accepted 1 September 2014. Published 9 March 2015.]

Abstract

While the vast majority of the meat consumed in later medieval Ireland (c. 1100–1600) was from domesticates such as cattle, sheep and pig, the hunting of game was important as a social marker. Access to game varied depending on social status, occupation and geographical location, and could be used to mediate social relationships. This paper focuses mainly on the zooarchaeological evidence from eastern Ireland, examining castles, and urban, rural and ecclesiastical sites of mainly Anglo–Norman origin. It will review this evidence for both truly wild mammal species such as red deer, wild pig and hare as well as for species such as fallow deer and rabbits, which were maintained in a managed environment before being hunted for food.

Introduction

In later medieval Ireland, the vast majority of meat consumed—generally well in excess of 95%—came from the three main domesticates: cattle, sheep and pig, regardless of geographical location or social status. Nevertheless, game meat could supplement these everyday foods on an occasional or regular basis and was an important element in the diet of the time. In examining status and social groupings within later medieval society, access to hunted meat is a key marker, both because of the diversity this provided in the diet and because of restrictions in access to such foods.1 In common with the nobility of both continental Europe and England2 the Anglo–Norman elite sought to restrict access to hunted foods, by limiting hunting rights for many sections of society. This control over who could hunt, and when and where hunting could take place meant that consumption of game became a status symbol for the elite. The restrictions effectively resulted in venison and other game meats being possessions that could be gifted to favoured individuals and institutions. The act of giving created cycles of obligation and further gift-giving, so binding members of the elite social group more closely together. Paradoxically, these stringent social controls also made game a potential target for poaching by the lower social classes.

Background

In both Ireland and England, in the later medieval period, there were four types of landscape in which restrictions over hunting were enforced: forests, chases, parks and warrens. ‘Forests’ were defined as land in which the timber and the hunting of certain game were reserved for the king.3 The animals protected by forest law were red, fallow and roe deer as well as wild pigs, although roe deer were not found in Ireland. ‘Chases’ or ‘chaces’ were similar to forests but were under the control of a member of the nobility who had received a ‘right of free chase’ from the king; however, the terms ‘forest’ and ‘chase’ were sometimes used interchangeably.4 ‘Parks’ were relatively small enclosed areas of land in which to keep deer, graze cattle and sheep, raise horses, supply timber for construction and provide a location for fish ponds and rabbit warrens.5 The word ‘warren’ had two meanings in the later medieval period: the first relates to an artificial construction for rearing rabbits.6 The other context in which this word was used was in a ‘right of free warren’. This meant that a landowner had the exclusive right to hunt the ‘beasts of the warren’ on his land and that others were forbidden by law to do so.7 The ‘beasts of the warren’ included the hare, rabbit, fox, wild cat, badger, wolf and squirrel.8 In addition there were a number of ‘birds of the warren’ including pheasant, partridge and woodcock, and occasionally plover and lark.9 All species could be hunted at will outside of the bounds of a forest, chase or warren and hence these land designations were hotly sought after.10 They were seen as marks of royal favour, a way of demonstrating prestige, and also a way of controlling access to hunting activities.11

Methodology

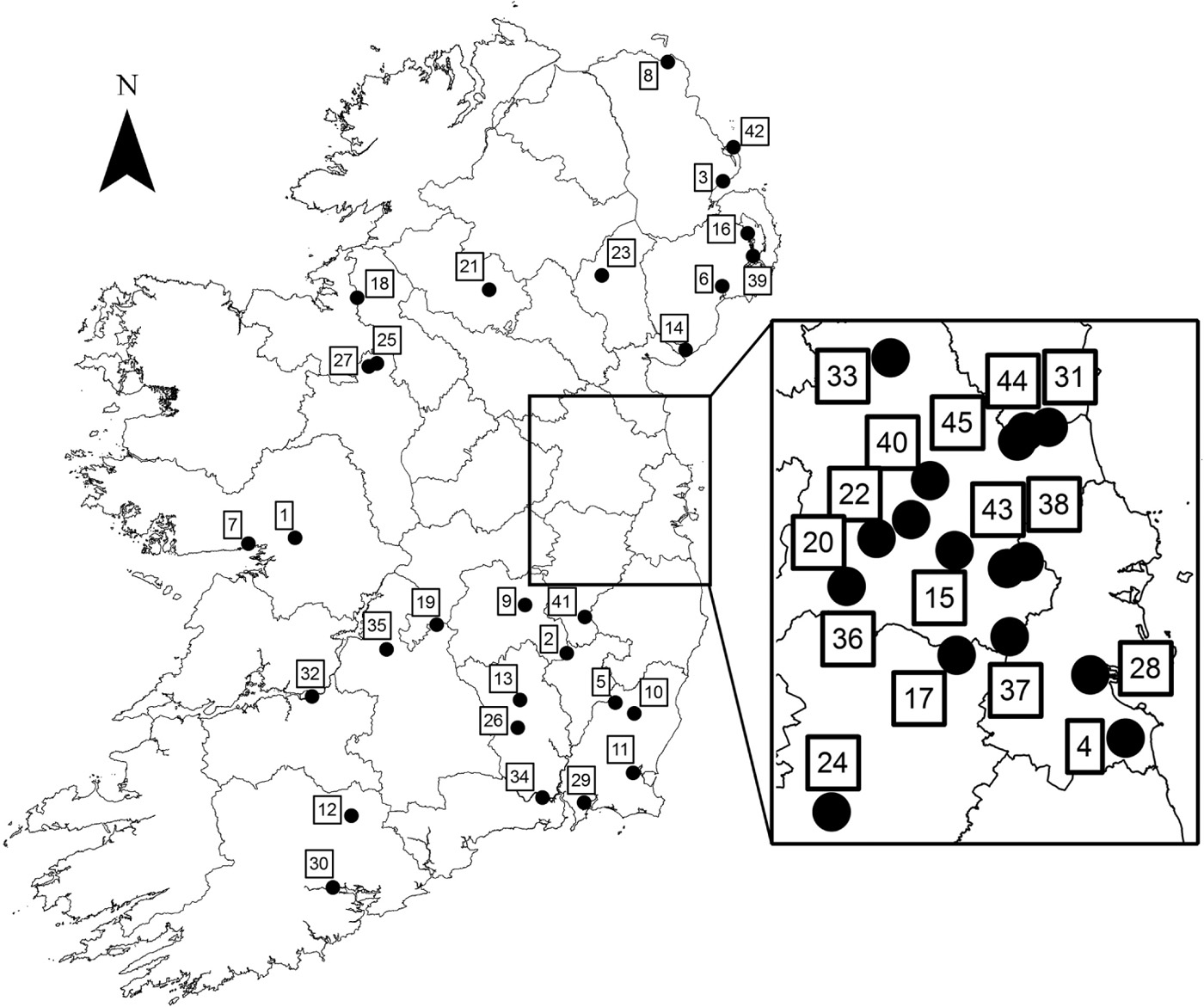

Based on these restrictions it would be expected that the zooarchaeological evidence from different site types would show varying levels of wild species and that the relative proportions of the various species would also vary. To test this hypothesis, data from a range of published and unpublished excavations of later medieval sites have been reviewed. These were classified into four categories: castles, ecclesiastical sites, urban sites and rural sites. This review included red deer (Cervus elaphus), wild pig (Sus scrofa) and hare (Lepus timidus) as well as badger (Meles meles), hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus), red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris), seal (Pinnipedia) and also cetaceans (Cetacea) such as dolphins and whales, since all of these were considered edible. In addition to the truly wild species, the analysis also included fallow deer (Dama dama) and rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), which during the medieval period were essentially farmed in parks and warrens respectively. The analysis excluded animals hunted as vermin or for their fur and also amphibians and birds. The number of identified specimens present (NISP) was used throughout this analysis. NISP is a count of bone fragments that can be positively identified as coming from a particular species, genus or order. Sites with phases dated to between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries were included, and some small assemblages were excluded since these were not statistically significant. In some cases it was necessary to estimate the overall site NISP from inferences made in the faunal report if this was not clearly quantified; however, numbers of wild mammals were not estimated.

Unfortunately, the sample sizes and number of sites available in the various categories of site type differed. Urban and castle excavations often produce large animal bone assemblages and due to public interest and the quantity of other material discovered they are most frequently published, so that these site types are well represented. Ecclesiastical sites are also often published; however, as O’Connor12 noted for England, these sites often yield relatively little animal bone, possibly due to very organised waste disposal within monastic communities, and as a result relatively few zooarchaeological reports have been included in publications on these sites. In this case, the majority of the sites are monastic in character, with one parish church: St Audoen’s, Dublin, and one bishop’s cuirt or palace: Kilteasheen, Co. Roscommon. Also included was Cathedral Hill, Armagh, where various pits and a substantial ditch were found to surround the cathedral. Many rural settlement sites are small, and therefore produce small assemblages; they also have poor above-ground visibility and therefore are often only found during development works. As a result, few have excavation reports published in full and even fewer include zooarchaeological reports of any substance. The sites included here are mainly from the author’s own work and from the site reports included on CDs in the National Roads Authority (NRA) Scheme Monograph series, which provide a valuable source of information on these smaller, lower profile excavations. Separate samples from particular excavations were generally from distinct phases of activity or physical areas within the site.

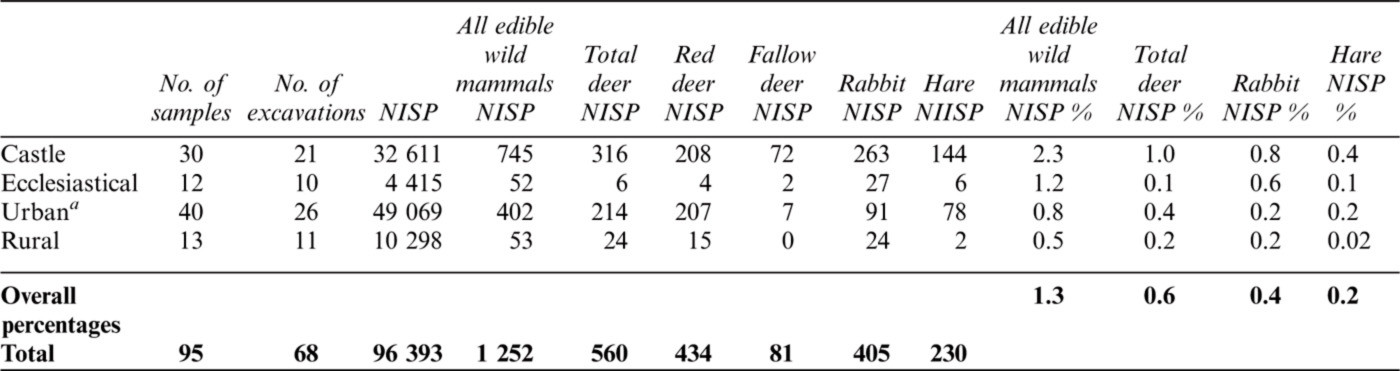

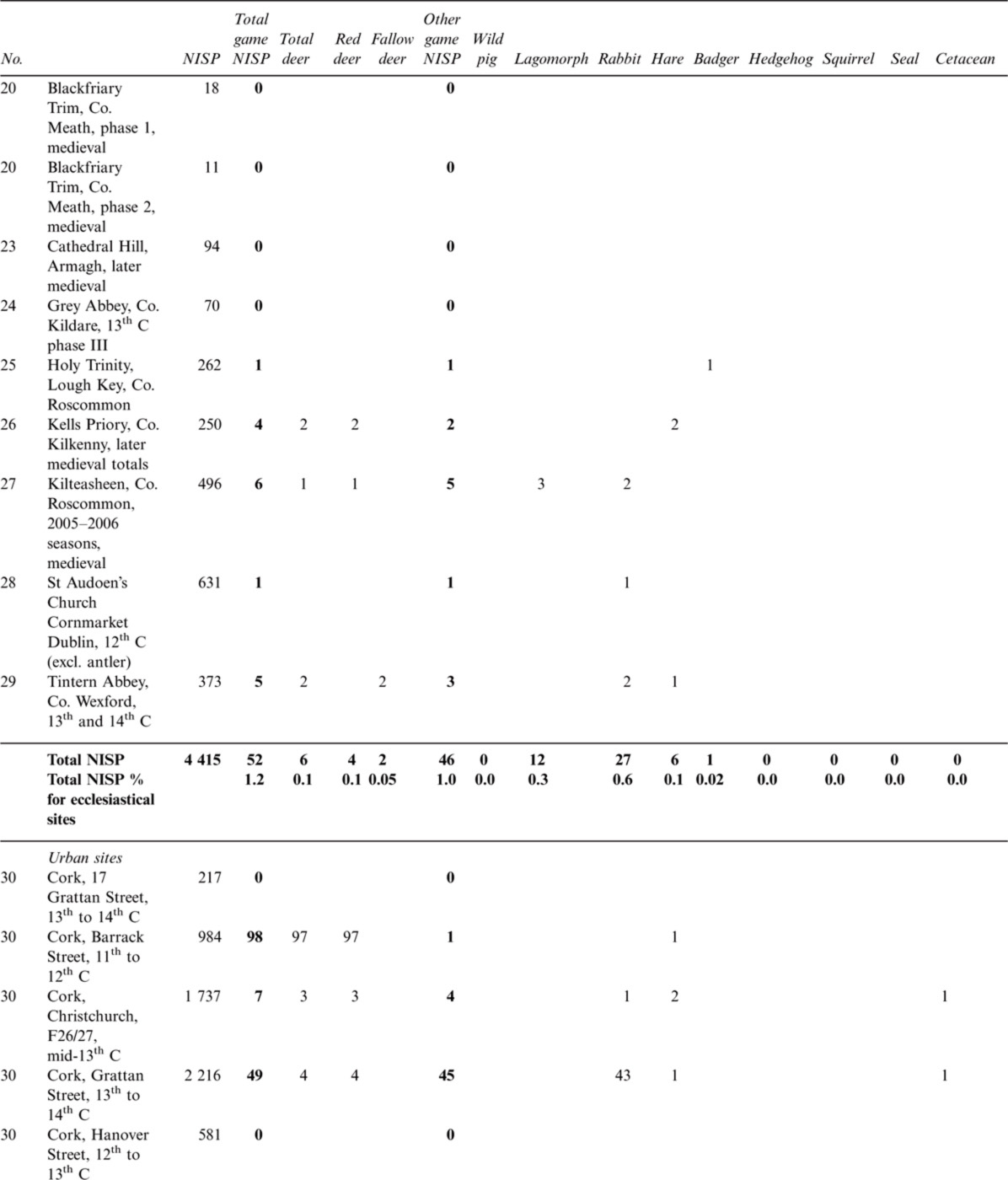

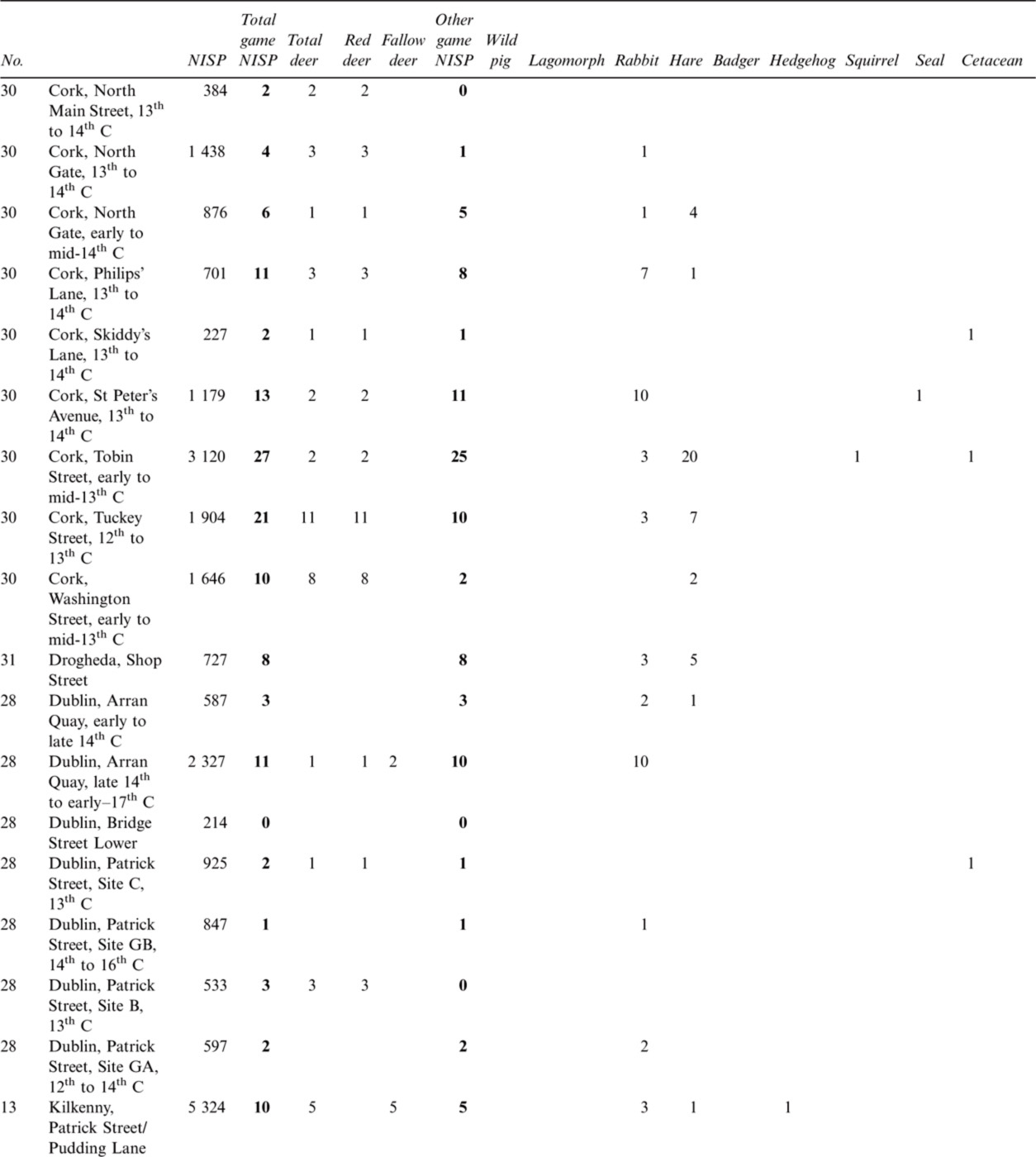

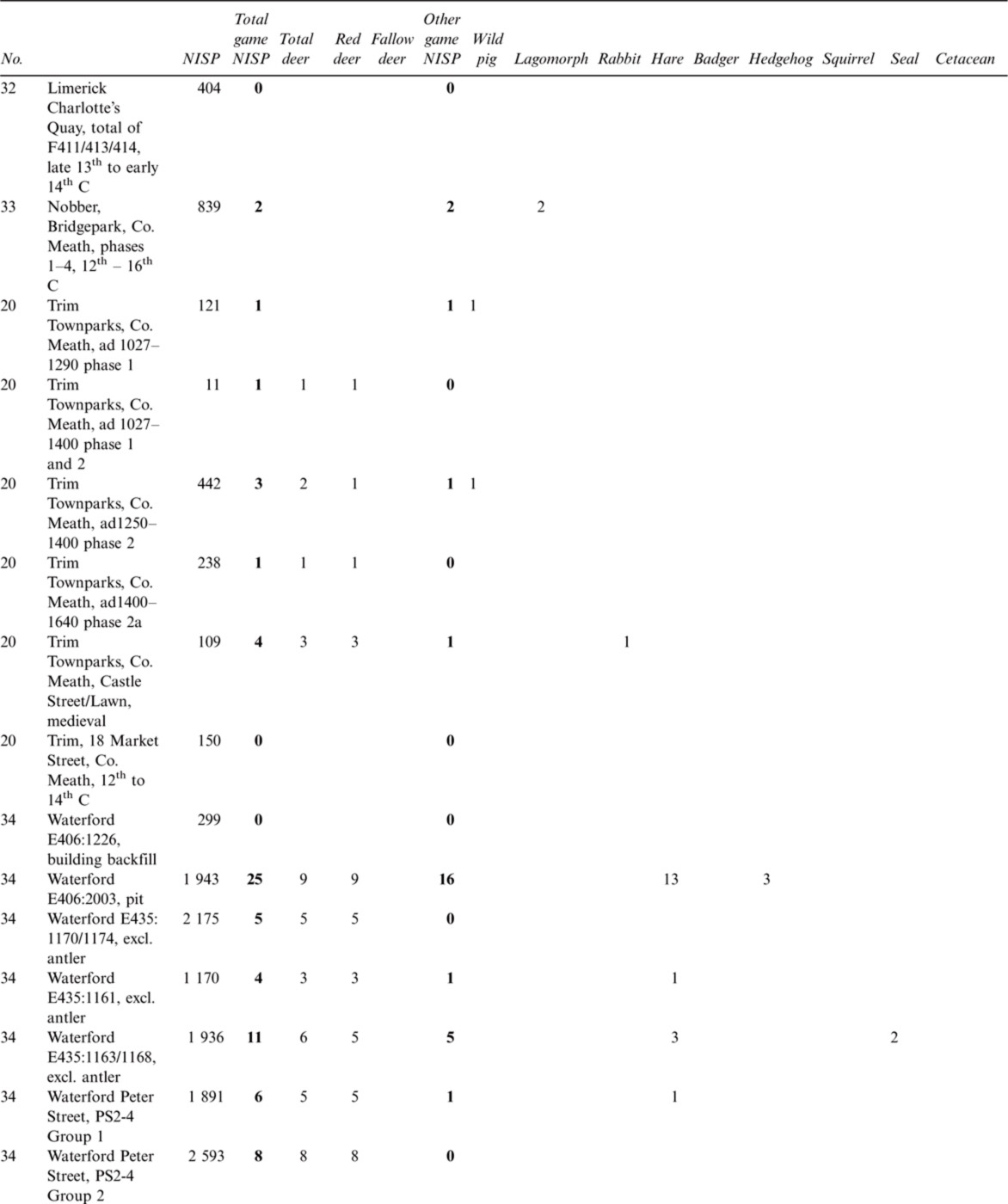

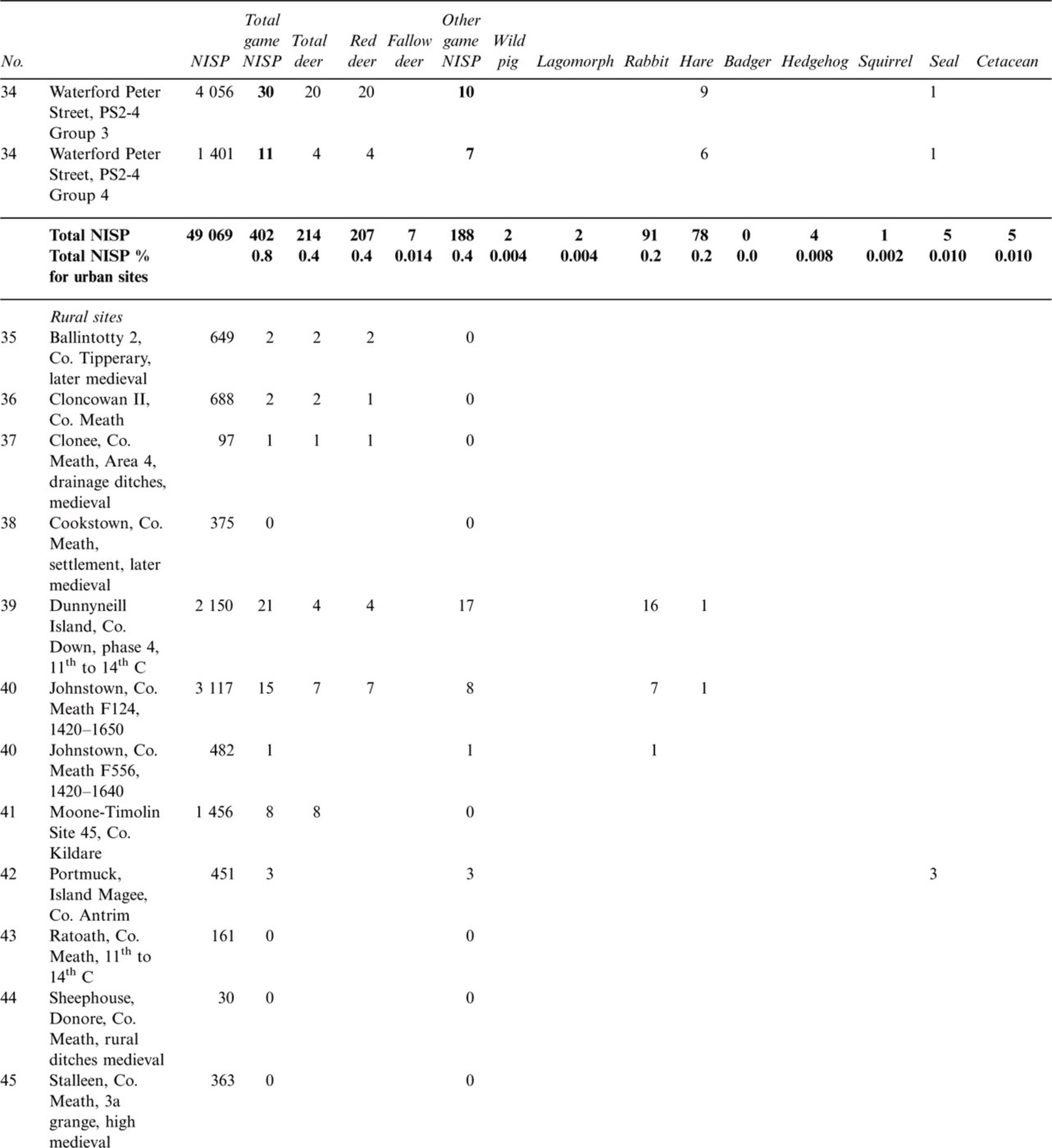

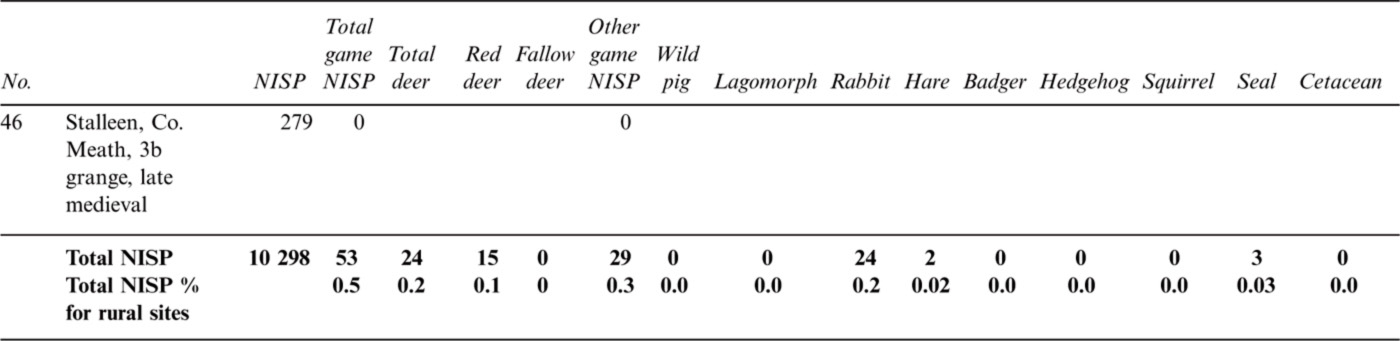

TABLE 1 —Summary of the recorded presence of edible wild species at later medieval sites.

Abbreviation: NISP = number of identified specimens present.

a Note that the urban figures exclude quantified caches of antler-working waste.

Zooarchaeological and historical data

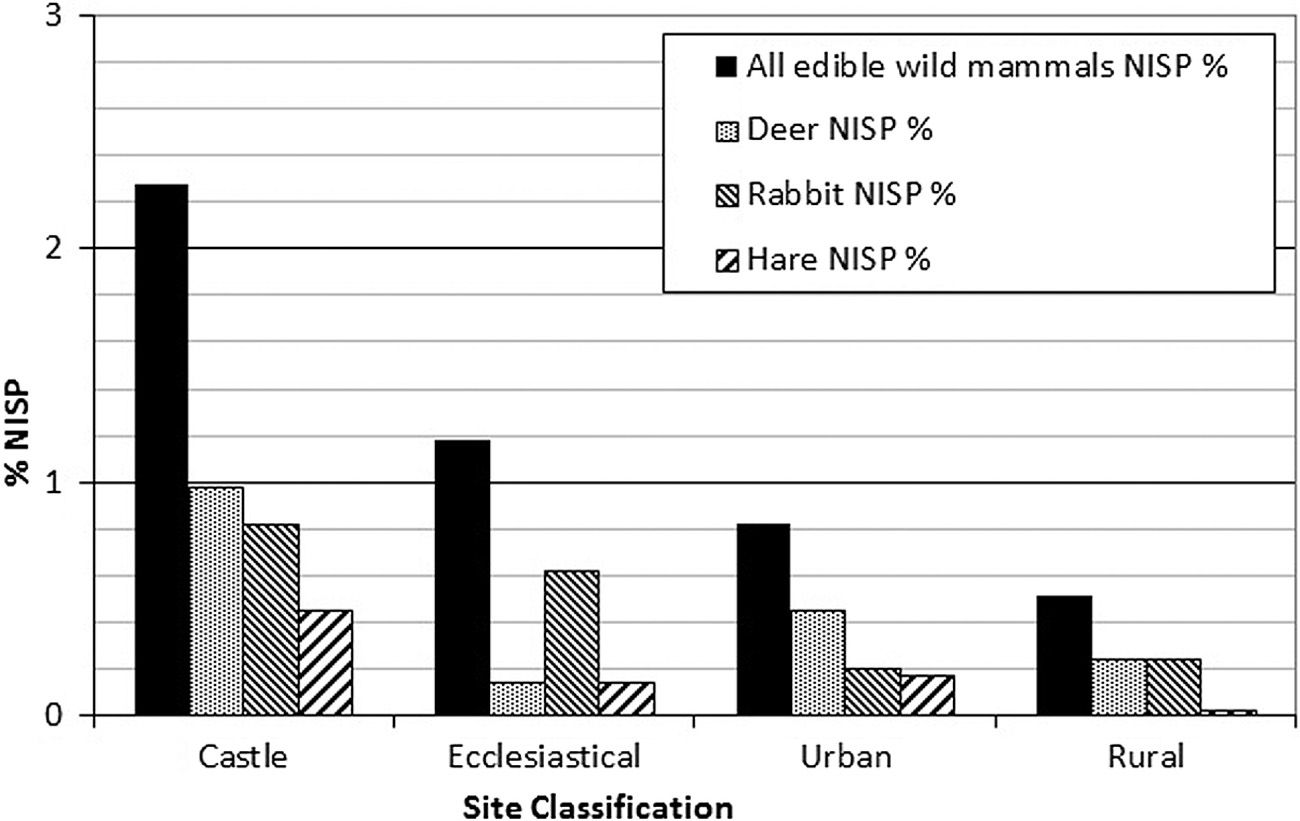

In all, 95 samples from 68 separate excavations and a total of 96,393 individual bones were considered. From this sample a total of 1,252 bones were from edible wild mammal species, yielding an average of 1.3%. Deer, rabbit and hare made up the vast majority of the wild species, with only occasional examples of the other species (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 1).

While edible wild mammals constituted an average of 1.3% of the assemblages overall, this rose to 2.3% (745/32,611) on castle sites, where they were the most common (Fig. 2). Ecclesiastical sites were the next most frequent, with an average of 1.2% (52/4,415) of the total assemblage being wild mammals. Surprisingly, urban sites yielded a higher percentage of wild elements than rural sites, with deer elements making up the bulk of the total. In urban sites, antlerworking waste is common so where body part distributions have been reported this has been disregarded. However, it was also stated that the majority of the material from the eleventh-century to fourteenth-century excavations in Cork City were antler,13 but as no figures were given it was not possible to eliminate these. If these sites are disregarded entirely then the ‘urban’ figure drops from 0.8% (402/49,069) to 0.5% (270/49,069). As a comparison, in England, wild mammal bones were also most likely to come from elite sites, where they constituted 13% of the assemblages14 so the above-mentioned total figure of 2.3% for Irish castle sites is very low. There are a number of possible reasons for this including the availability of game animals as well as warfare, economics, politics and absenteeism;15 nevertheless, it is a figure that is considerably higher than that for other site types.

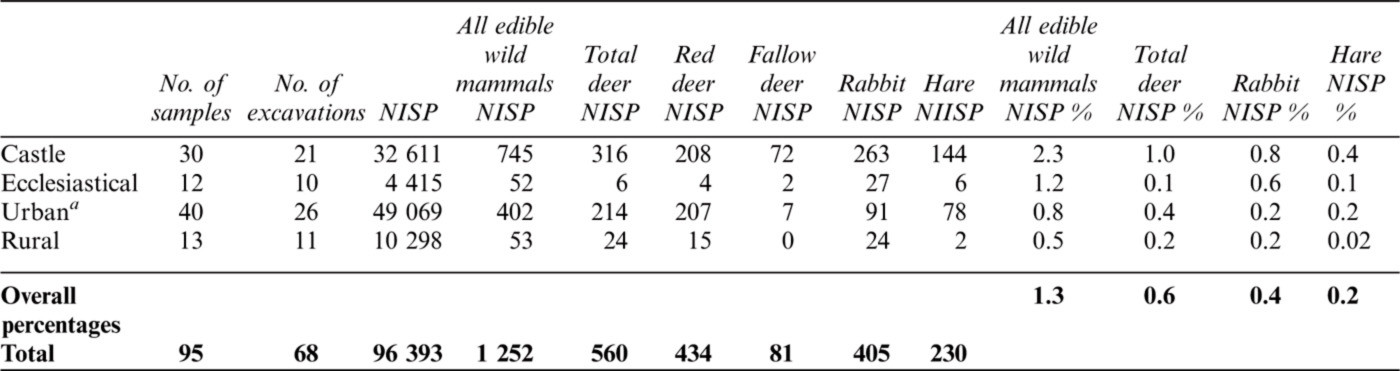

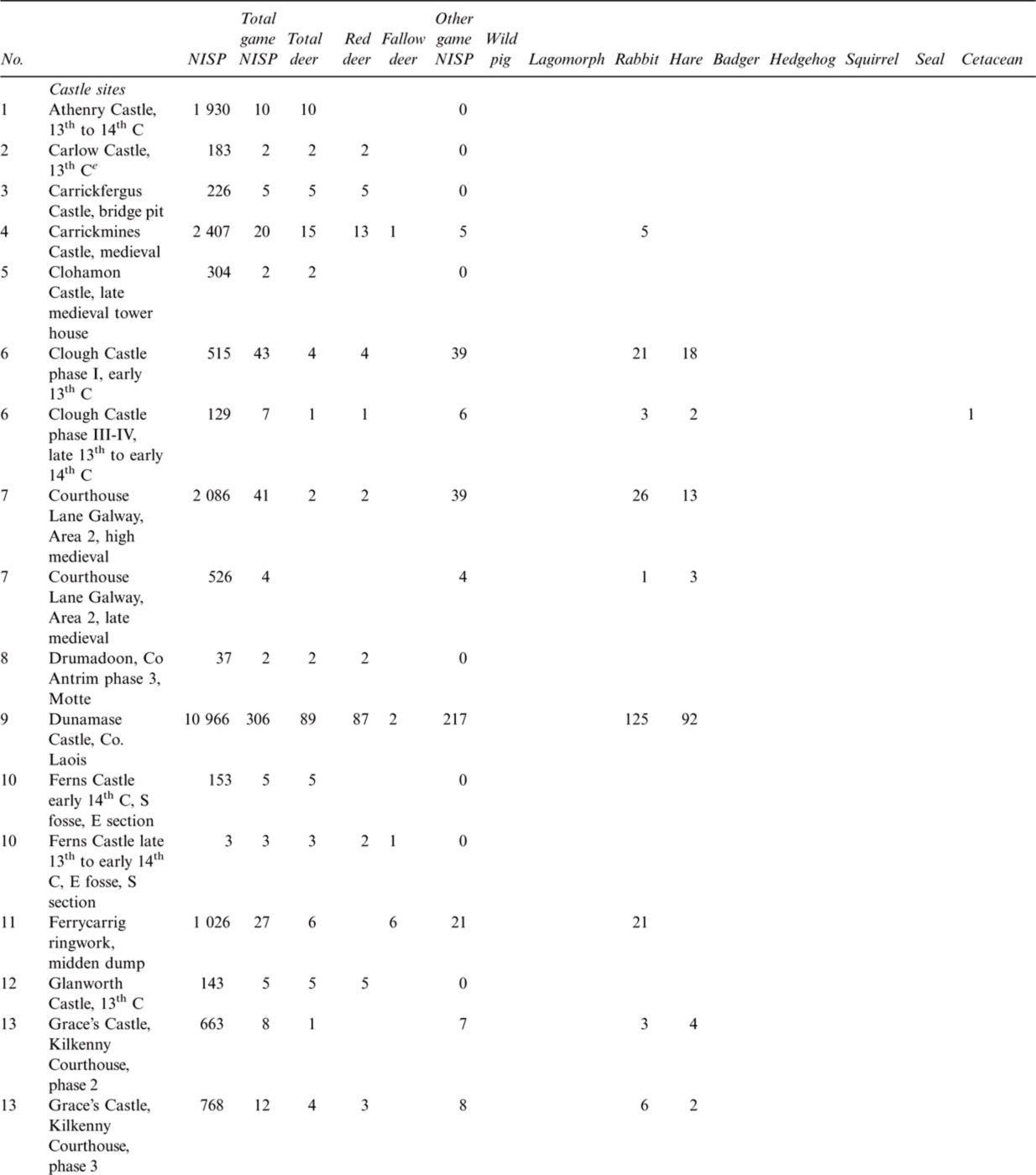

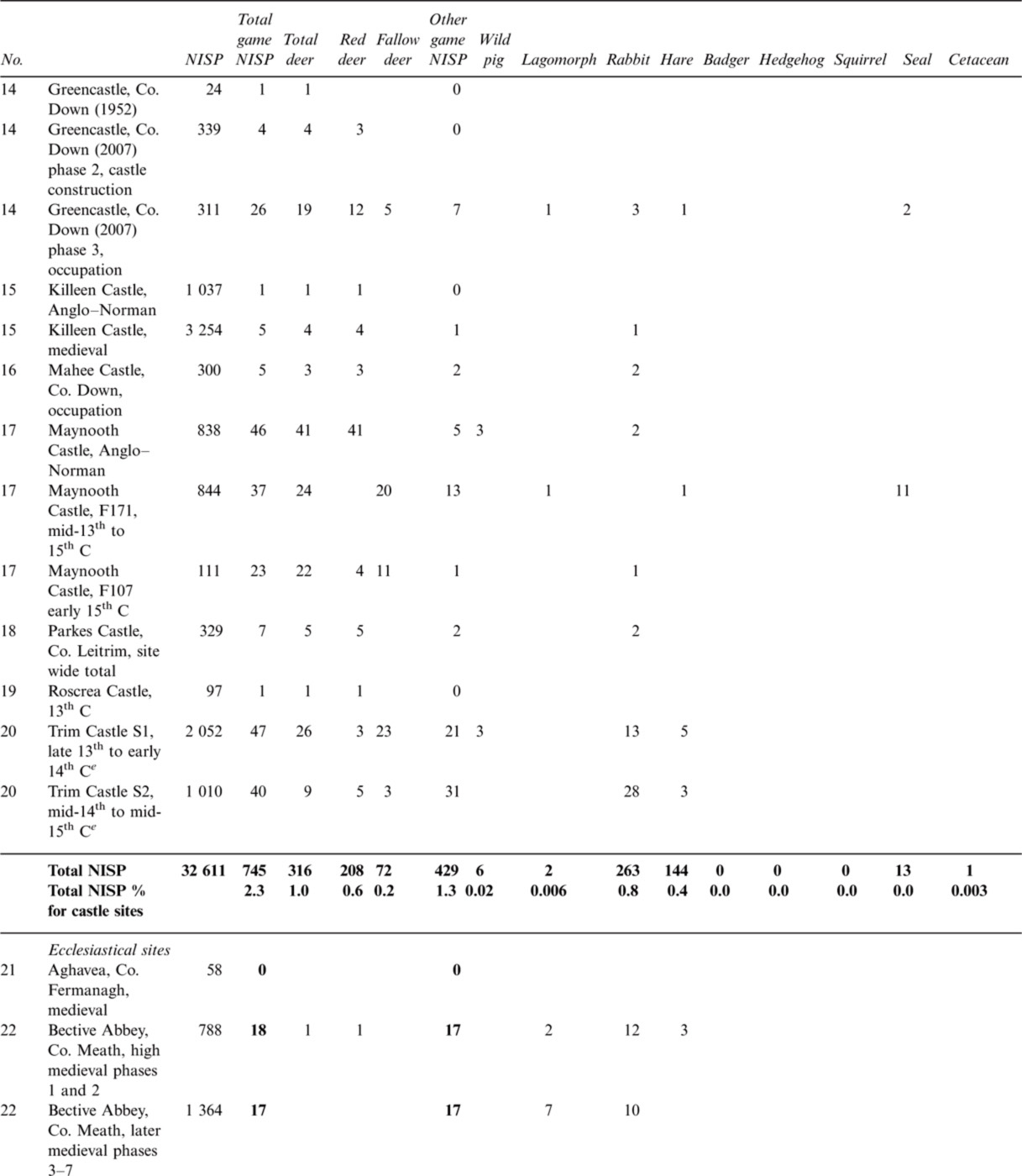

TABLE 2—Zooarchaeological data for the sites included in the study, classified into castle,a ecclesiasticalb, urbanc and rural sites.d

Abbreviation: NISP = number of identified specimens present.

a Margaret McCarthy,‘Faunal report’, in Cliona Papazian, Brenda Collins, and Margaret McCarthy, ‘Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway’, Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society 43 (1991), 27–43; Patricia Lynch, ‘Animal bone report: Carlow Castle, Co. Carlow 96E105’, unpublished report for K.D. O’Conor, n.d.; Margaret Jope, ‘Animal bones from Carrickfergus Castle bridge-pit’, in D.M. Waterman, ‘Excavations at the entrance to Carrickfergus Castle, 1950’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology 15 (1952) 103–18; Sean Denham and Emily Murray, ‘The animal bones from medieval and post-medieval contexts at Carrickmines Castle, Co. Dublin’, unpublished report for Margaret Gowen and Co., n.d.; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Clohamon Castle, Castlequarter, Co. Wexford. Licence number: 09E0393’, unpublished report for James Lyttleton, 2012; Margaret Jope, ‘Animal remains from Clough Castle’, in D.M. Waterman, ‘Excavations at Clough Castle, County Down’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology 17 (1954), 150–6; Emily Murray, ‘Animal Bone’, in Elizabeth FitzPatrick, Madeline O’Brien and Paul Walsh (eds), Archaeological investigations in Galway City 1987–1998 (Dublin, 2004), 562–601; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Drumadoon: Licence no. AE/03/105’, unpublished report for Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork (CAF), Queen’s University Belfast, 2005; Vincent Butler, ‘Preliminary report on the animal bones from Dunamase, Co. Laois, 93E150. 1994 season’, unpublished report for Brian Hodkinson, 1995; Vincent Butler, ‘Preliminary report on the animal bones from Dunamase, Co. Laois, 93E150. 1995 season’, unpublished report for Brian Hodkinson, 1996; Vincent Butler, ‘Preliminary report on the animal bones from Dunamase, Co. Laois, 93E150. 1996 season’, unpublished report for Brian Hodkinson, 1996; Vincent Butler, ‘Preliminary report on the animal bones from Dunamase, Co. Laois, 93E150. 1997 season’, unpublished report for Brian Hodkinson, n.d.; B. Whelan, ‘Report on animal bones’, in D. Sweetman, ‘Archaeological excavations at Ferns Castle, Co. Wexford’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 79C (1979), 244–455; Finbar McCormick, ‘The mammal bones from Ferrycarrig, Co. Wexford’, unpublished report, n.d.; Pam Crabtree and Kathleen Ryan, ‘Faunal remains’, in Conleth Manning (ed.), The history and archaeology of Glanworth Castle, Co. Cork: Excavations 1982–4 (Dublin, 2009), 117–22; Margaret Jope, ‘Report on animal bones from Greencastle Co. Down’, in D.M. Waterman and A.E.P. Collins, ‘Excavations at Greencastle, County Down, 1951’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology 15 (1952), 101–02; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Greencastle, Co. Down, 057:003, Licence no. AE/01/13’, unpublished report for CAF, Queen’s University Belfast, 2007; Siobhán Duffy, ‘From castle to gaol: analysis of the animal bones from Kilkenny Courthouse, Kilkenny, Ireland’, unpublished MA thesis, University of Southampton, 2010; Jonny Geber, ‘The faunal remains’, in Christine Baker (ed.), The archaeology of Killeen Castle, Co. Meath (Dublin, 2009), 131–56; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Mahee Castle. Licence nos. AE/01/58 and AE/02/79’, unpublished report for CAF, Queen’s University Belfast, 2007; Emily Murray, ‘Faunal remains from Maynooth Castle’, unpublished report, n.d.; Fiona Beglane, ‘Animal bone’, in Claire Foley and Colm Donnelly (eds), Parke’s Castle, Co. Leitrim: archaeology, history and architecture (Dublin, 2012), 109–20; Nora Birmingham, ‘The animal bones’, in Conleth Manning (ed.), Excavations at Roscrea Castle (Dublin, 2003), 144–5; F. McCormick and E. Murray, ‘Animal bones’, in Alan Hayden (ed.), Trim Castle, Co. Meath: Excavations 1995–8 (Dublin, 2011), 421–33.

b Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Aghavea, Co. Fermanagh, Ferm 231:036’, unpublished report for CAF, Queen’s University Belfast, 2007; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Bective Abbey, Co. Meath. Licence no. E4028’, unpublished report for Geraldine Stout, 2013; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Blackfriary, Trim, Co. Meath: consent no. C150, licence no. E2398’, unpublished report for Cultural Resource Development Services (CRDS), 2009; Valerie Higgins, ‘The animal remains’, in Cynthia Gaskell Brown and A.E.T. Harper, ‘Excavations on Cathedral Hill, Armagh, 1968’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology 47 (1984), 154–6; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Grey Abbey: licence no. 04E0233’, unpublished report for Margaret Gowen and Co. Ltd, 2006; Miriam Clyne, ‘Archaeological excavations at Holy Trinity Abbey Lough Key, Co. Roscommon’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 105C (2005), 23–98; Finbar McCormick, ‘The faunal remains’, in Miriam Clyne (ed.), Kells Priory, Co. Kilkenny: archaeological excavations by T. Fanning and M. Clyne, Archaeological Monograph Series 3 (Dublin, 2007), 477–82; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Kilteasheen, Co. Roscommon: licence no. 05E0531: 2005’, unpublished report for Chris Read, 2006; Vincent Butler, Animal bone report’, in Mary McMahon (ed.), St Audoen’s Church, Cornmarket, Dublin: archaeology and architecture (Dublin, 2006), 115–17; Finbar McCormick, ‘Appendix IV: the faunal remains’, in Ann Lynch (ed.), Tintern Abbey, Co. Wexford: cistercians and colcloughs. Excavations 1982–2007 (Dublin, 2010), 227–32.

c Margaret McCarthy, ‘The faunal remains’, in Rose Cleary and M.F. Hurley (eds), Excavations in Cork City 1984–2000 (Cork, 2003), 375–90; Margaret McCarthy, ‘Faunal remains: Christchurch’, in Rose Cleary, M.F. Hurley and Elizabeth Shee Twohig (eds), Skiddy’s Castle and Christ Church. Cork. Excavations 1974–77 by D.C. Twohig (Cork, 1997) 349–59; Margaret McCarthy, ‘The faunal remains’, in M.F. Hurley (ed.), Excavations at the North Gate, Cork (Cork, 1997), 154–8; Finbar McCormick, ‘The animal bones’, in M.F. Hurley and O.M.B. Scully (eds), Late Viking Age and medieval Waterford (Waterford, 1997); Finbar McCormick, ‘The mammal bone’, in Alan Hayden, ‘Excavation of the medieval river frontage at Arran Quay, Dublin’, in Sean Duffy (ed.), Medieval Dublin V (Dublin, 2004), 221–41; Finbar McCormick, The mammal bones from Arran Quay, Dublin, unpublished report, n.d.; Vincent Butler, ‘Report on the animal bones from C46, C48, C50, C53, C54, C56, C58, C60 and C62’, in Mary McMahon, Vincent Butler and J. Collins, ‘Archaeological excavations at Bridge Street Lower, Dublin’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 91C (1991), 41–71; Finbar McCormick and Eileen Murphy, ‘Mammal bones’, in Claire Walsh (ed.), Archaeological excavations at Patrick, Nicholas and Winetavern Streets, Dublin (Dublin, 1997), 199–218; Eileen Murphy, ‘Osteological report on the mammal bones from Patrick Street/Pudding Lane, Kilkenny (Licence 98E0092)’, unpublished report, 1999; Finbar McCormick, Appendix 1: the animal bones’, in Ann Lynch, ‘Excavations of the medieval town defences at Charlotte’s Quay, Limerick’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 84C (1984), 322–30; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Bridgepark, Nobber, Co. Meath. Licence no. 07E0345’, unpublished report for CRDS Ltd, 2009; Fiona Beglane, ‘Meat and craft in medieval and post-medieval Trim’, in Michael Potterton and Matthew Seaver (eds), Uncovering medieval Trim: archaeological excavations in and around Trim, Co. Meath (Dublin, 2009), 346–70; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Townparks South, Trim, Co. Meath. Excavation licence no. E2016. Ministerial consents C121, C139’, unpublished report for CRDS Ltd, 2007).

d Margaret McCarthy, ‘Faunal analysis Ballintotty E2935 - A026/445’, in ‘Aegis M7 Limerick to Nenagh animal bone reports’, unpublished report for the National Roads Authority (NRA), n.d.; Alan Pipe, ‘Report on animal remains’, in Christine Baker, ‘Excavations at Cloncowan II, Co. Meath’, The Journal of Irish Archaeology 16 (2007), 98–120; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Clonee Townland, Clonee, Co. Meath. Licence no. 08E0840’, unpublished report for Archtech Ltd, 2009; Emily Murray, ‘The animal bones’, in Richard Clutterbuck, ‘Cookstown, Co. Meath: a medieval rural settlement’, in Chris Corlett and Michael Potterton (eds), Rural settlement in medieval Ireland in the light of recent research (Dubin, 2009), 27–47; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Dunnyneill’, unpublished report for CAF, Queen’s University Belfast, 2005; Fiona Beglane, The faunal remains from Dunnyneill Island, Strangford Lough, Co. Down, unpublished MSc thesis, Queen’s University Belfast, 2004; Catherine Boner, ‘Johnstown 1: analysis of mammal bones’, in Neil Carlin, Linda Clarke and Fintan Walsh (eds), The archaeology of life and death in the Boyne floodplain on CD (Dublin, 2008); Patricia Lynch, ‘Bone report’, in Valerie Keeley and Hillary Opie, ‘Archaeological excavations site 45: N9 realignment Moone-Timolin-Ballintore Hill, Co. Kildare 99E202’, unpublished report for NRA, 2001, 121–66; Eileen Murphy, ‘The animal bone’, in Sue Anderson and A.R. Rees, ‘The excavation of a medieval rural settlement at Portmuck, Islandmagee, Co. Antrim’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology 63 (2004) 76–113; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Ratoath Co. Meath: licence no. 03E1781’, unpublished report for Archtech Ltd, 2005; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Sheephouse, Donore, Co. Meath. Licence no. 06E1164’, unpublished report for CRDS Ltd, 2008; Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Stalleen townland, Donore, Co. Meath. Licence no. 08E0456’, unpublished report for CRDS Ltd, 2012.

e Modified from the original reports to include re-identification of fallow deer to other species.

Deer

Throughout medieval Europe the main animals of the hunt were deer, with red and fallow deer relevant to Ireland.16 Red deer may have arrived in Ireland as early as the Late Glacial period after the Ice Age, although a recent review of the data suggests that they were introduced during the Neolithic period.17 By contrast, fallow deer were introduced by the Anglo–Normans in the early thirteenth century.18 Red deer were essentially wild animals that were hunted in open country, while initially at least, fallow deer were kept in parks that could be used as venues for hunting or as ‘live larders’ depending on their size and the inclination of their owner.19

FIG. 1—Location of castles, and urban, rural and ecclesiastical sites discussed in the text. The numbers are cross-referenced in Table 2.

FIG. 2—Number of identified specimens present (NISP) of wild mammals from a range of site types.

Giraldus Cambrensis,20 writing in the twelfth century was uncharacteristically positive in his view of Irish red deer, stating that they ‘are not able to escape because of their too great fatness’ and that they had particularly impressive heads and antlers. He also noted though, that in common with the other wild species of animals they were small. Four centuries later, Philip O’Sullivan Beare21 again commented on the ‘most dense herds of fat deer’ in Ireland and the protection afforded to them by their antlers, which they used against both dogs and people. Red deer are a common image on wall paintings and tapestries and in carvings, and, in Ireland, they appear on a number of hunting scenes. They were tightly bound into a complex symbolism with religious, kingly and erotic connotations. For example the shedding of the blood of the deer was compared to the Blood of Christ which is commemorated in the Eucharist and the blooding of new hunters was compared to the rite of baptism.22 The death of the deer could symbolise both the consummation of erotic love, with the symbolic shedding of virgin blood, and the capture of the heart,23 while white deer in particular were associated with immortality and a rightful lineage of kings controlling the land and people back through time.24

The Romans first introduced fallow deer to Western Europe from the eastern Mediterranean, as exotica to be kept in parks. Their numbers declined markedly after the fall of the Roman Empire, but with the spread of Norman culture along the Atlantic seaboard, they were reintroduced to north-western Europe, again as a park animal.25 As a result, the species first came to Ireland with the Anglo–Normans. The earliest mention of the species in connection with Ireland was in 1213 when the archbishop of Dublin was granted 30 fallow deer from the king’s park of Brewood in England.26 They are therefore not mentioned by Giraldus Cambrensis who was writing a generation before this, but are discussed briefly by O’Sullivan Beare,27 writing in the early seventeenth century, who comments that they are smaller than red deer and ‘protected by simple, but bigger horns, bent over their foreheads; here, sometimes you may see them fighting bravely’. There was much less symbolism attached to fallow deer than to red deer, and much of this was shared with, or more likely, borrowed from red deer.28

The analysis included a total of 560 deer bones, excluding quantified caches of antler-working waste from St Audoen’s and from urban Dublin, but including the unspecified quantities of antler from Cork City. Of these, 434 were from red deer, 81 were from fallow deer and the remainder had not been separated into species in the zooarchaeological reports. Deer were uncommon at all site types, but they were found in the greatest numbers at castle sites. While they achieved only an average of 1.0% of the identified bones at castle sites, it is significant that this is more than twice the level achieved at urban sites, and more than four times that at rural sites. All of the castles yielded some deer bones apart from the very small assemblage from the late medieval tower house of Clohamon Castle, Co. Wexford. Nine out of 21 castles yielded fallow deer and all except Clohamon and Ferrycarrig ringwork, Co. Wexford, produced red deer remains.

Ecclesiastical sites were the only site type on which deer were not the largest group of edible wild mammals, with only four out of ten sites yielding deer bones. Tintern Abbey, Co. Wexford, was the only ecclesiastical site to include fallow deer, a metatarsal from the early fourteenth century and a long bone shaft from the thirteenth or early fourteenth century. All other deer bones identified to species were from red deer. Urban sites yielded a large number of deer bones and antler fragments, with the majority of these being from red deer. Only two sites, Patrick Street/Pudding Lane, Kilkenny, and Arran Quay, Dublin, produced fallow deer remains. Six out of eleven rural sites yielded deer, however, these were in small numbers. Only red deer was identified to species, with fallow deer not found, and a total of only 24 specimens was recorded.

Deer body part distribution

Having reviewed the overall finds of deer bones, a more detailed analysis can shed further light on social differentiation in food supply. There were a number of methods of deer hunting used during the medieval period, including the par force chase, the drive, or bow-and-stable hunting and the use of traps and nets.29 These often included ritual steps, some of which depended on the method of hunting, and some of which were more generally applicable. The process of dismembering or unmaking the carcass was one of the most ritualised of the stages and in France this was often carried out by the most senior person present. In England, this was more usually delegated to a professional huntsman, or to the person who killed the deer, although in the late sixteenth century, Queen Elizabeth I, a keen hunter, was willing to undertake the feat herself. Special sets of knives were sometimes used and certain organs were reserved for the lord by being set up on display on forked sticks stuck into the ground (Fig. 3).30

Hunting manuals of the period state that it was standard practice for the left shoulder of the carcass to be given to the person doing the ‘unmaking’ or dismembering, the right shoulder to the forester, and the haunches, or back legs, were reserved for the lord.31 Depending on which source is consulted, the head was either reserved for the lord or given to the lymer, or ‘scenting hound’ that tracked the deer. The os courbin, which may have been the pelvis or possibly the sternum, was given to the ravens.32 By contrast with England, where this introduction of a structured distribution has been dated to the later medieval period,33 an early Irish judgement that was preserved in a law text and poem refers to similar customs extant in the seventh or eighth centuries:

the first person who wounds the deer is entitled to the classach, which presumably refers to some part of its body, the person who flays the deer gets its shoulder (lethe), and the owner of the hounds gets the haunch (cés). Another person—perhaps he who actually kills the deer— gets the neck (muinél), and the hounds themselves get the legs (cossa). The last man on the scene gets the intestines (inathar) and the rest of the hunting-party get the liver (áe). Finally, the landowner gets the belly (tarr).34

FIG. 3—Ritual breaking of the stag carcass as shown in BNF MS 619, Le Livre de chasse, p. 59r. Reproduced courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France

This would suggest that in both later medieval England and in early medieval Ireland, a shoulder was given to the person dividing up the carcass. In Ireland the owner of the dogs was given the haunches, and in England the lord received this portion, but since dogs were expensive to maintain, they presumably belonged to the lord, and therefore the same distribution can be inferred. This distribution reflects the quality and tenderness of the meat. In cattle, for example, the hind limb includes the topside and silverside whereas the forelimb includes the much tougher clod and shin of beef. Similarly, leg of lamb is much higher quality, more tender meat than the shoulder of lamb from the forelimb. 35 A number of researchers have examined the prevalence of hind limb bones in the zooarchaeological record of England36 and detailed study has shown that this distribution is valid for both red and fallow deer, with a disproportionate amount of bones from the rear of the animal present at elite sites, and forelimbs over-represented at the homes of foresters, parkers and huntsmen.

It was therefore to be expected that, given these customs in both early medieval Ireland and later medieval England, a similar tradition was likely to be maintained in later medieval Ireland. Using the Irish data, an analysis was carried out of the body-part distribution. In the rural and ecclesiastical sites small numbers of bones were identified and patterns were mixed so that it was impossible to interpret the results in a meaningful way. Rural sites included some antler fragments, as well as teeth, two radii and a humerus from the forelimb, and an astragalus from the hind limb. The ecclesiastical sites included a metacarpal from the forelimb, a tibia, astragalus and metatarsal from the hind limb and a partial skull.

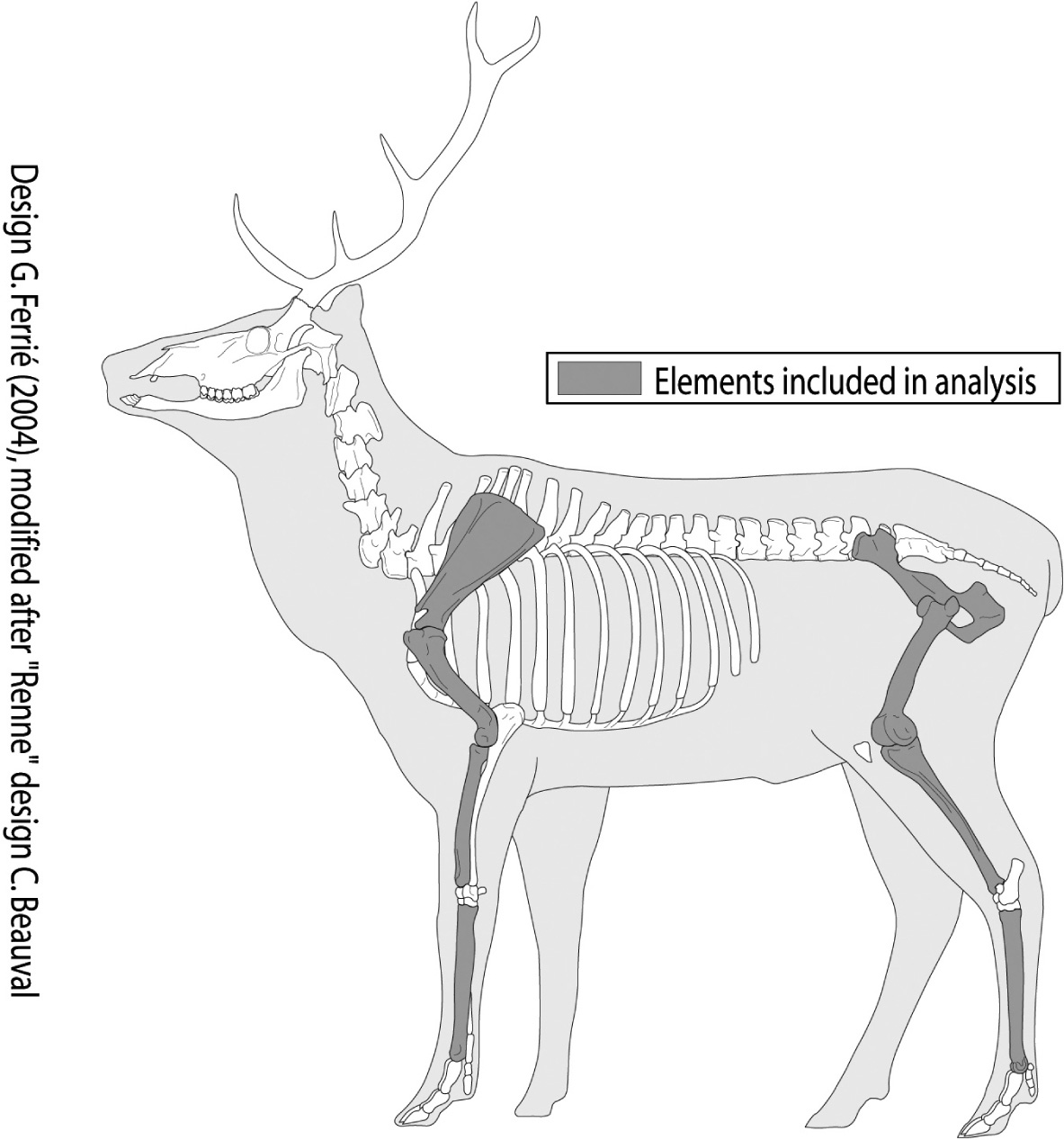

More useful results were obtained from the castles and urban sites. In total, this involved 28 samples from 16 castle sites and 28 urban samples from Dublin, Kilkenny, Galway, Trim and Waterford. One further limitation is that the summaries included in the published reports of these results do not always include body-part distribution, and so some sites could not be included. The frequency of the four main bones of the front and hind limbs were compared (Fig. 4). In the case of the front limb, the scapula, humerus, radius and metacarpal were included. The ulna was not included since the equivalent bone in the hind leg of a deer is extremely small and rarely quantified by zooarchaeologists. In the case of the hind limb, the pelvis, femur, tibia and metatarsal were used. Most zooarchaeologists do not record all of the individual carpals and tarsals (wrist and ankle bones), however, they do generally record the calcaneus and astragalus, which are the two largest tarsal bones. It was decided to exclude these as otherwise the analysis would be weighted in favour of identifying hind limb bones, purely because more of them are systematically recorded. In addition, the phalanges (toe bones) of the front and hind limbs cannot easily be separated except where they are excavated from an articulated skeleton; therefore these bones were excluded from the measure.

For the castle sites, 73.7% (101/137) of the identified bones were from the hind limb. By contrast, only 50% (25/50) of the bones from urban sites were from the hind limb. The evidence suggests that the general body-part distribution found in English elite sites is mirrored in Irish later medieval castle assemblages, with the majority of bones being from the hind limbs. When the analysis was conducted separately for red and fallow deer it showed that for red deer 71% (64/90) of the identified bones were from the hind limbs, whereas for fallow deer 76% (26/34) were from this part of the body, clearly demonstrating that the same procedure was being undertaken for both species. Although the same general distribution is found on Irish castle sites as on English elite sites, some differences do occur. Thomas37 demonstrated that forelimbs were either absent or were present only at extremely low levels, arguing that where they were present, this was evidence for occasional lapses in the systematic division of the carcass. By contrast, the Irish evidence is for the presence of approximately three hind limb bones to every one forelimb bone at castle sites.

FIG. 4—Elements included in the body-part distribution analysis.

The urban results suggest that there are generally equal numbers of fore and hind limbs present in Irish towns. In England, Sykes38 also found that urban assemblages contained both fore and hind limb bones. She further argued that the other body parts present, including head elements, were evidence of organised poachers who were known to operate out of taverns and alehouses. These poaching gangs worked on a commercial basis, supplying venison to relatively wealthy individuals such as merchants, who did not have official access to this high-status meat. The presence of all body parts in the urban assemblages from Ireland suggests that illicit poaching was also occurring here and there is documentary evidence to support this.39

The ability to make a direct comparison between elements from medieval burgage plots at the urban site of Kiely’s Yard in Trim Townparks, Co. Meath, and the immediately adjacent Trim Castle is highly revealing, although the sample of deer bones from the burgage plots is small and could therefore be argued to be unrepresentative. Nevertheless, for the castle, 71% (15/ 21) of the assessed elements were from the hind limb, whereas in Kiely’s Yard there was a humerus and a scapula, both of which are from the forelimb. Kiely’s Yard also yielded a tooth and a phalanx or toe bone, which could have come from either. An astragalus from the hind limb was found in the ‘Castle Lawn’ area immediately outside the castle. This area also yielded a scapula from the forelimb, an antler fragment and another phalanx. Given that this location is outside the castle, it may well be that debris produced by the inhabitants of both the town and the castle was deposited there. In a separate excavation at High Street, Trim, Lynch40 found a single deer metacarpal, which again is from the forelimb.

This comparison of results from the town with those from the castle supports the idea that systematic body-part distribution was being undertaken in Trim. As the town is immediately adjacent to the castle, the forelimb bones found in the burgage plots could potentially have come from poached animals, or could have been legitimate meat. The size of the bones suggests that they were from male red deer. For aristocratic hunting, males would have been deemed to provide the best sport, but for poachers, looking for a simple and quick hunt, a mature male would not necessarily have made the best target as a young individual or a female without antlers would have been easier to capture and kill. Coupled with the presence of only forelimb elements at Kiely’s Yard and at High Street, the evidence suggests that this meat had come from huntsmen. This may have been in the form of gifts, or the huntsman’s share if he lived in the town, or could potentially have been illicitly sold on by a huntsman who had obtained it legally.

Ireland had far fewer forests and parks than England and communities were smaller.41 As a result, many professional huntsmen probably lived either in a castle or immediately adjacent to it. In this case, their share of the deer may have been consumed in the castle and/or their refuse may have been disposed of with the castle waste. As a result, it is reasonable that higher proportions of front limb bones are to be found at Irish castle sites than at elite sites in England. Furthermore, this suggestion of the professional hunters living adjacent to the aristocratic hunters is borne out in Trim where forelimb elements were found in urban excavations.

Rabbit

Rabbits and hares are both members of the order Lagomorpha, and the bones of both species are sufficiently similar that, particularly in the case of juvenile elements, some individual toe bones and loose teeth, they cannot always be easily separated. Since their bones are relatively small, they are less likely than those of larger animals to be preserved due to poor soil conditions, destruction by carnivores such as dogs and waste disposal into fires. Furthermore, their small size makes them less likely to be recovered during excavation, especially if soils are not routinely sieved. This means that rabbit and hare bones are likely to be under-represented in zooarchaeological assemblages compared to those of, for example deer.

Rabbits were not native to Ireland; instead they originated in the western Mediterranean. They were probably originally introduced to Britain by the Romans and then reintroduced by the Normans42 who subsequently brought them to Ireland. The original rabbits were not the hardy creatures of today, which, through natural selection, have become able to withstand northern European winters. Instead, artificial warrens, often earthen mounds, were constructed to house these delicate creatures, and until the mid-fourteenth century these were usually termed ‘coneygarths’.43 Initially, ownership of a warren was the preserve of the elite, but as the animals multiplied, possession widened to the gentry classes, and as rabbits became naturalised, feral colonies developed, leading to increased availability of wild rabbits. Later medieval coneygarths were often situated in parks or on islands where the rabbits could be protected from predators, with Lambay Island, Co. Dublin, being a good example of the latter.44 Pillow mounds, which are cigar-shaped earthworks, are a common archaeological feature of the English countryside that have been interpreted as coneygarths, and some may date to the later medieval period, however, many of those that have been excavated have been found to date to the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries.45 Few, if any, pillow mounds have been found in Ireland, and a search of the database of Irish excavation reports46 suggests that none have been excavated. O’Conor47 suggested that in Ireland deserted ringforts and islands may have been used instead. As with deer, rabbits also had a symbolic meaning in medieval iconography. Rabbits were seen as weak creatures that huddled together in communities and were managed by a warrener. Through this they were viewed as emblems of meek, lowly humankind who could be brought to salvation by Christ.48

Rabbits were the second most common single species identified in the assemblages, however, since they burrow, it can be difficult to determine whether they were truly present in a context or if the bones were intrusive and the animals had merely burrowed into the context later. There were 405 rabbit bones, and again castle sites yielded the largest number and proportion of these. It is notable, however, that while red and fallow deer combined were the most important food source at castle sites, rabbits were dominant on ecclesiastical sites. There are references to rabbit warrens being maintained by monastic communities and by bishops in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries,49 and the medieval church considered foetal and newborn rabbits to be acceptable foods for fast days because of their enclosure within the liquid environment of the womb.50

Rabbits were also present at moderate levels in urban sites, where small numbers were found in a wide range of excavations. These rabbits are likely to have been brought in from warrens in the countryside. They could have been poached, however, there is also evidence that towns had legitimate access to rabbits either sold as surplus by the manors or produced specifically for sale in the towns. For example, in November 1393 an order was sent ‘to the sovereign, provost and community of the town of New Ross’ to supply various foodstuffs to James Butler, earl of Ormond and Justiciar of Ireland, who planned to spend Christmas in the town. This included large numbers of cattle and pigs as well as birds, fish and 100 pairs of rabbits.51 Notably this list did not include deer or hare, as the inhabitants would not have had legitimate access to quantities of these species.

Only two rural sites yielded rabbits: Dunnyneill Island, Co. Down, and the late medieval contexts at Johnstown, Co. Meath, which produced eight bones. Sixteen rabbit bones came from later medieval occupation contexts at Dunnyneill, however c. 70 further elements were recovered from the topsoil. Given the island location and the large numbers of elements present in the topsoil, it is quite possible that many of these are intrusive.

Hare

Hares are native to Ireland, they are related to rabbits and have similar skeletons but are larger. They occupy a wide range of habitats, including pasture and arable land as well as uplands and bogs. Unlike rabbits, they do not burrow, but instead they conceal themselves in forms, which are depressions in heather, rushes or hedgerows.52 Hares were hunted using dogs or by being caught in nets and traps and were valued for sport, fur and food.53 Since hares were a beast of the warren, there were restrictions on hunting them, and penalties could be severe. For example, in 1230 Nicholas de Verdun received a right of free warren for his manor of Ferard and it was specifically stated that ‘No one is to hunt hare without Nicholas’ license on penalty of 10l’.54

Hares are the third most common edible mammals in the assemblages reviewed and again, the majority are found on castle sites. Relatively few are found on ecclesiastical sites with only a total of six bones identified from Tintern Abbey, Co. Wexford and Bective Abbey and Kells Priory, both Co. Meath. This is very low, especially by comparison with rabbits and suggests that monastic orders did not have regular access to hare meat. By contrast, urban examples of hare bones are almost as common as rabbit bones and although the numbers were small, they were widely distributed. The low numbers of hare bones on rural sites was surprising since they can be caught using nets and so could potentially be targeted relatively easily outside restricted areas or by poachers. It also raises the possibility that hares caught legitimately by rural inhabitants or by poachers were sold in towns for money, rather than being consumed domestically.

Other species

Small numbers of other edible wild species were found. The most common of these were seal bones, which were found at Greencastle, Co. Down; Maynooth Castle, Co. Kildare; Peter Street and E435, Waterford; St Peter’s Avenue, Cork; and Portnamuck, Co. Antrim. Apart from Maynooth Castle, all of these are coastal locations where seal bones can reasonably be expected, either as natural intrusions or as a result of deliberate exploitation for food. Since seals live in water, their meat was considered acceptable food to eat during times of fasting. Seal bones were also found at the early medieval monasteries of Ilaunloughan, Co. Kerry, and Iona, Scotland.55 In 1555 Olaus Magnus recorded that the church in Sweden considered seal meat as acceptable for consumption during Lent.56 While live seals have been found to have travelled considerable distances inland,57 Maynooth Castle is 25km from the sea so that it is likely that this was a definite decision to import seal to the site.

Wild pigs are woodland animals, and are omnivores, eating roots, seeds, fruit, plant material, carrion and eggs.58 They could be hunted using dogs but could also be trapped, and were considered to be the most dangerous of the animals hunted.59 There is controversy regarding their fate, since the latest zooarchaeological example of wild pig is from thirteenth century or fourteenth century material at Trim Castle,60 but O’Sullivan Beare refers to wild pigs.61 This led Finbar McCormick to suggest that O’Sullivan Beare may have seen feral domesticated pigs, since these are essentially the same species. Since wild and domesticated pigs are the same species, only size can be used to identify the presence of wild pig in an assemblage. Three wild pig bones were found in late thirteenth century to early fourteenth century deposits at Trim Castle, and two possible examples came from the burgage plots at Kiely’s Yard in Trim Townparks that also yielded red-deer elements. Three possible wild pig bones were also found in Anglo–Norman contexts at Maynooth Castle.

A small number of cetacean bones were recovered from urban deposits in Cork and Dublin and from Clough Castle, Co. Down, which is less than 2km from Dundrum Bay. These are likely to have come from stranded animals, which were subsequently scavenged for food and craft materials.62

One badger bone came from the monastic site at Lough Key, Co. Roscommon, and a single squirrel bone came from Tobin Street in Cork. Both species were considered edible, however they could also be used for their skins. For example, O’Sullivan Beare says of the badger that ‘its flesh is not unpleasant to eat nor is its pelt to be despised’ and that the blood could be used in a cure for leprosy.63

Three hedgehog bones were found in Waterford E406 and one in Patrick Street/Pudding Lane, Kilkenny. Again hedgehogs were considered edible, however, their presence in urban sites may hint at their use in craftworking, as the spiny skins had been used to card wool since at least classical times.64

Discussion

Both foods and the animals that are the source of these foods are important aspects of the material culture of any society and therefore their study can shed light on social issues such as identity, status and ideology.65 The diet of an individual is determined by a number of factors. Firstly, the food must be available within the society being examined, so that, for example, prior to the introduction of rabbits to Ireland, the absence of rabbit from the diet is not useful in differentiating social groups within Ireland. However, in the case of both rabbit and fallow deer these were introduced by the Anglo–Normans, so providing additional food choices for some sections of later medieval society and creating a new way of expressing their identity through food. As such, for the later medieval period, the presence or absence of these foods becomes significant as an indicator of social identity and status. Within the range of foodstuffs potentially available, the position and role of an individual in society can affect the diet in terms of such factors as what foods are acceptable or taboo to consume, what foods are considered to be desirable and the cost of, or ease of access to the particular food of choice. Finally, diet is partly a matter of personal choice or agency, with individuals preferentially selecting different foods from those that are available and socially acceptable. Individual choice can rarely be identified in the archaeological record; however the other factors can be examined and based on the zooarchaeological evidence for the various species, it possible to differentiate the diet of the various groups within society: nobles, ecclesiastics, rural dwellers and urban dwellers, and from this to examine the role of food in expressing these ideas of identity.

For the reasons discussed above, access to game meats was restricted and hence these foods provided opportunities for individuals to accumulate and display both wealth and social capital.66 In theory, venison could not be sold, so that social capital could be obtained both by the ability to serve venison and by gifting whole carcasses or portions of venison to favoured individuals or institutions. This was true for the lord gifting portions to his retainers or to a nearby abbey, but was also true for the parkers, foresters and huntsmen, who had legal access to this highly prized meat. For them, the opportunity to gift or to illicitly sell this meat was also an opportunity for increased prestige and income. Poachers could gain an income by supplying a willing urban market, with relatively well-to-do individuals keen to sample the meats consumed by the aristocracy and to serve them at feasts as a method of impressing their guests, and in doing so increasing their own social capital.

Game in the noble diet

For a medieval aristocrat, hunting primarily served not just to put food on the table, but instead it was a part of elite culture, positioning the individual within society and creating an aristocratic identity.67 Hunting could be used to create cycles of gift-giving and reciprocal hospitality. There is evidence in Ireland of royal gifts of deer to favoured subjects,68 and invitations to hunts or to feasts serving venison would have been important occasions at which to demonstrate and create allegiances and alliances.

The nobility sought to control access to hunted foods and one question that this study can answer is whether or not they were successful in this aim. The live animals themselves were part of the material culture of the time, particularly the fallow deer and rabbits that lived in semi-domesticated circumstances in parks and warrens. They were considered to be property and therefore possessing them and being able to serve their flesh was a reflection of the owner’s status and position in society. Even wild animals, although not owned as such, were a reflection of the status of the lord, who may have had a right of free warren or free chase on his lands and so had exclusive rights to hunt certain wild animals within certain limits of geography.

Given these restrictions, it is not surprising that castles were the most likely site type to yield wild mammal bones, with 2.3% total game species and 1.0% deer. This equates to approximately 42% of the edible wild mammal bones found at the castle sites being from deer, of which one quarter were from fallow deer. Rabbit (35%) and hare (19%) made up the bulk of the remainder, with other species being found only occasionally. Given the relative size of deer, rabbits and hares, and ignoring differential taphonomic and body part distribution factors, this means that over 96% of the wild meat consumed on castle sites was venison and so it can be stated that venison was the wild meat of choice at these high-status sites.

There is also evidence for the ritual ‘breaking’ of the carcass along prescribed lines, with predominantly hind limbs found at castle sites, which were the portions of the carcass traditionally reserved for the lord. This would have included the prime cuts of meat, equating to the topside and silverside in beef.69 By contrast, the forelimbs should have been given to the employed huntsmen, parkers and foresters, and these were under-represented at castle sites. This demonstrates that these traditions were known, understood and practised in Ireland. Nevertheless, the body-part distribution found at Irish castle sites was not as extreme as in England, where forelimb bones are rare on castle sites. This may be linked to the relative size of households, since in Ireland the huntsmen may have lived within the castles.

Game in the ecclesiastical diet

The ecclesiastical diet was meant to be one of moderation, including regular periods of fasting, and without, or later with only limited consumption of meat.70 Hunting by clergy or monks was discouraged, however, many high-ranking members of the church were of noble birth and would have hunted since childhood.71 The ecclesiastic group inhabited an ambiguous position in society in which they were of relatively high status, some of them had parks or warrens stocked with deer and rabbits, they had access to gifts of red and fallow deer from wealthy patrons and may have taken part in hunting on their own account. Nevertheless, they were meant to abstain from meat consumption at least on certain days of the week and on specific holy days and periods during the year.

This ambiguity is reflected in the zooarchaeological results from ecclesiastical sites. At a total of 1.2% they were the second most likely to yield wild mammal bones, but numerically the bones were dominated by rabbit, with only occasional deer bones. Ironically, as a result of the relative size of the animals, approximately 88% of the wild meat again came from deer with rabbit providing 8%, but it is important to restate that the relatively small size of rabbit and hare bones means that they are less likely than those of deer to be represented in zooarchaeological assemblages. All but three of the sites considered here are monastic in character, and of these only three yielded deer bones. This may have meant that few deer carcasses or joints were gifted to the churches and monasteries and that relatively few ecclesiastics had the opportunity to hunt deer or hare. Venison can therefore be considered to be a minor component of the overall ecclesiastical diet, however, it is important to consider that access to game was not necessarily equal within ecclesiastical circles. The situation of a bishop or archbishop was very different to that of a prior or abbot, who would in turn have had access to a wider range of foods than a junior member of his order. For example, while the archbishop of Dublin is documented as having his own deer, a number of parks and also rabbit warrens, the priory of Holmpatrick, Co. Dublin, had a rabbit warren, which also supplied the Priory of the Holy Trinity, Co. Dublin.72

With limited access to wild meat, it can be suggested that at monastic sites this type of meat was often reserved for the abbot’s table on the occasion of a feast or for high-ranking visitors rather than for general consumption. For example, the Priory of the Holy Trinity in Dublin regularly bought in precooked food and on one occasion paid 6d for ‘one roast goose, a rabbit cooked, and pigeons cooked’ to be served to the prior and selected guests in the private environment of the sacristy.73 Nevertheless, given the likely under-representation of rabbit bones in assemblages, this meat may well have provided occasional welcome variety for the monks in a diet otherwise dominated by beef, pork and mutton.74

Game in the urban diet

The identification of hunting and venison with the aristocracy raises the issue of venison in the urban environment. Sykes75 suggests that most of the fallow deer remains from urban sites in England were the result of poaching or of illicit sales of the forester’s and hunter’s portions. The Irish evidence suggests that poaching was also important in Ireland. Even when antler-working waste is excluded, urban assemblages are second only to castle sites in the number of deer elements found there. Examining the body-part distribution, they have generally similar proportions of forelimb and hind limb bones, as well as containing fragments of skull and mandible. These are indicative of deer that have been slaughtered and dismembered without regard for the formal rules of breaking’ the carcass. Since venison was regarded as meat for the landed nobility, it would have been highly sought after by wealthy, aspirational townsfolk. These rich merchants would have had the financial means to procure illicit, poached venison, and by doing so, and serving it at feasts and banquets they sought to emulate their social superiors. This demonstration of their cultured regard for fine dining would have increased their standing among their peers and as a result they would have gained cultural capital. Trim was a large town by medieval standards, but was small compared to cities such as Dublin or Waterford, and so employment and trade would have centred on the castle. In this case, there are a number of legitimate reasons why the huntsman’s portion of venison could find its way to a burgage plot. This may have been the huntsman’s home, or the home of his family, or he could have illicitly sold his portion on the black market.

Urban excavations also yielded significant quantities of rabbit and hare bones, although these made up only a small proportion of the meat sold in the towns. Hares and rabbits were sold by poulterers, who also sold birds such as geese and chickens.76 While some of their stock may have been legally sourced through sales of surplus rabbits or of hares and feral rabbits hunted outside of restricted areas, some could also have come from poachers. In theory, hunting rabbits and hares was subject to similar restrictions to deer; however, their meat was more accessible than venison. Mature deer are large and can be dangerous to hunt, however, hares and rabbits can be caught legitimately or illegitimately without personal danger using dogs, nets and traps. Having caught them, the smaller carcass sizes made them easier to transport over distances and they required minimal butchery, as a whole hare could be sold to a household. Again, consumption of rabbit and hare would have marked out the urban dweller as aspirational, seeking to emulate the diet of the nobility as far as possible within his means, and certainly in medieval England, urban dwellers served rabbit for feasts and celebrations.77

Game in the rural diet

Because of their low archaeological profile, relatively few rural sites have been published and these have yielded only small assemblages of bone, nevertheless, a sample size of 10,298 is significant and should be sufficient in order to identify patterns. These sites yielded the smallest percentages of wild species, which is counter-intuitive given that rural people would have had legal access to hunting outside areas of forest, free warren and chase and that they could potentially also poach wild animals. When antlers are excluded, very few deer bones were identified, as well as negligible quantities of hare bones, suggesting that they did not target these species. The proportion of rabbits is similar to that of deer but with this species a question mark must be raised since most of the examples came from the island site of Dunnyneill, Co. Down. Overall it can be concluded that rural people rarely ate wild mammals, instead consuming the domesticated cattle, sheep and pig that make up the majority of faunal remains from all site types. There are a number of possibilities as to why this was so. Even outside of areas of forest, free warren and free chase, if rural people were found with game in their possession they would have had to prove that it had been obtained legally and this would have discouraged even legitimate hunting. Hunting would also have taken time that could be spent on risk-free routine tasks that were guaranteed to provide food or an income. Finally, as evidenced by the supply of wild meats in urban areas, any hunting that did take place, either legitimately or illicitly would have been more lucrative as a source of money than as a source of food.

Conclusions

Wild meats were a relatively unimportant source of calories in later medieval Ireland, generally providing only a maximum of a few per cent of the meat, but they did have enormous social significance and can be used as indicators of social identity and status, so providing important evidence for interpreting later medieval society. In common with elites across Europe, the nobility sought to control access to game and largely succeeded in this, with very few deer, hare or rabbit remains found on other site types. For monastic orders, venison and hare were only occasionally available, however they did have access to rabbits which provided variety in the diet for at least the upper echelons. Both documentary and zooarchaeological evidence show that by contrast with the monks, bishops and archbishops had access to game that was similar in nature to that enjoyed by the nobility. For wealthy urban dwellers, these high-status foods were accessible, for a price, and could be used to emulate the upper orders and increase social standing. Nevertheless, they would have been expensive and evidence for their consumption is limited so that it is likely that these were particularly popular for banquets and celebratory meals rather than for everyday meals. This meat could be supplied by urban dwellers with professional access to the castles, manors and their resources, but could also be supplied by poachers or by rural hunters who saw this market as a lucrative source of extra income, and seem to have rarely eaten wild meats themselves.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are due to the zooarchaeologists and licence-holders cited and to the NRA for access to unpublished data, without which this paper would not have been possible.

* Author’s e-mail: beglane.fiona@itsligo.ie

doi: 0.3318/PRIAC.2015.115.02

Much of the data utilised was from the author’s work as a consultant zooarchaeologist.

1 H.C. Kuechelmann, ‘Noble meals instead of abstinence? A faunal assemblage from the Dominican monastery of Norden, Northern Germany’, in Christine Lefèvre (ed.), Proceedings of the general session of the 11th International Council for Archaeozoology Conference (Oxford, 2012), 87–97: 88–9.

2 Aleksander Pluskowski, ‘Who ruled the forests? An interdisciplinary approach towards medieval hunting landscapes’, in Sieglinde Hartman (ed.), Fauna and flora in the Middle Ages (Frankfurt, 2007), 291–323: 291.

3 Oliver Rackham, The history of the countryside (London, 1987), 130; N.D.G. James, A history of English forestry (Oxford, 1981), 3.

4 L.M. Cantor and J.D. Wilson, ‘The medieval deer-parks of Dorset: III’, Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society 85 (1964), 141–52: 141; James, A history of English forestry, 5; Raymond Grant, The royal forests of England (Stroud, 1991), 30–1; Leonard M. Cantor, ‘Forests, chases, parks and warrens’, in Leonard M. Cantor (ed.), The English medieval landscape (London, 1982), 56–85: 70.

5 Rackham, The history of the countryside, 125; Fiona Beglane, Anglo–Norman parks in medieval Ireland (Dublin, 2015); Fiona Beglane, ‘Parks and deer-hunting: evidence from medieval Ireland’, unpublished PhD thesis, National University of Ireland, Galway, 2012.

6 Tom Williamson, Rabbits, warrens and archaeology (Stroud, 2007), 17.

7 James, A history of English forestry,6.

8 James, A history of English forestry, 39.

9 James, A history of English forestry, 39.

10 James, A history of English forestry, 3; C.R. Young, The royal forests of medieval England (Philadelphia, PA, 1979), 46.

11 Young, The royal forests of medieval England, 11.

12 T.P. O’Connor, ‘Bone assemblages from monastic sites: many questions but few data’, in Roberta Gilchrist and Harold Mytum (eds), Advances in monastic archaeology (Oxford, 1993), 107–11.

13 Margaret McCarthy, ‘The faunal remains’, in Rose Cleary and Maurice F. Hurley (eds), Excavations in Cork City 1984–2000 (Cork, 2003), 375–90: 380.

14 Naomi Sykes, The Norman conquest: a zooarchaeological perspective (Oxford, 2007), 65, App. Ia.

15 Beglane, Anglo–Norman parks in medieval Ireland.

16 Wilhelm Schlag, The hunting book of Gaston Phébus. Manuscrit français 616, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale (London, 1998), 20–3.

17 Peter Woodman, Margaret McCarthy and Nigel Monaghan, ‘The Irish Quaternary Fauna Project’, Quaternary Science Reviews 16 (1997), 129–59: 152–4; Finbar McCormick, ‘Early evidence for wild animals in Ireland’, in Norbert Benecke (ed.), The Holocene history of the European vertebrate fauna (Berlin, 1998), 355–71: 360–1. Ruth F. Carden, Allan D. McDevitt, Frank E. Zachos, Peter C. Woodman, Peter O’Toole, Hugh Rose, Nigel T. Monaghan, Michael G. Campana, Daniel G. Bradley and Ceiridwen J. Edwards, ‘Phylogeographic, ancient DNA, fossil and morphometric analyses reveal ancient and modern introductions of a large mammal: the complex case of red deer (Cervus elaphus) in Ireland’, Quaternary Science Review 42 (2012), 74–84.

18 McCormick, ‘Early evidence’, 360–1.

19 Beglane, Anglo–Norman parks in medieval Ireland; Fiona Beglane, ‘Deer in medieval Ireland: preliminary evidence from Kilteasheen, Co. Roscommon’, in Thomas Finan (ed.), Medieval Lough Ce: history, archaeology, landscape (Dublin, 2010), 145–58.

20 Geraldus Cambrensis, Topographia Hiberniae: the history and topography of Ireland by Gerald of Wales, ed. J.J. O’Meara (London, 1982), 47.

21 Philip O’Sullivan Beare, The natural history of Ireland c. 1626, ed. D.C. O’Sullivan, (Cork, 2009), 77.

22 Richard Almond, Medieval hunting (Stroud, 2003), 152; John Cummins, The hound and the hawk: the art of medieval hunting (London, 1988), 71–2; J.A. Stuhmiller, ‘The hunt in romance and the hunt as romance’, unpublished PhD thesis, Cornell University, 2005, 132.

23 Stuhmiller, ‘The hunt in romance’, 203.

24 John Fletcher, Gardens of earthly delight (Oxford, 2011), 127–9; Michael Bath, ‘King’s stag and Caesar’s Deer’, Dorset Natural History Society and Archaeological Society 95 (1974), 80–3; Cummins, The hound and the hawk,69–71.

25 Naomi Sykes, R.F. Carden and K. Harris, ‘Changes in the size and shape of fallow deer: evidence for the movement and management of a species’, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 23 (2013), 55–68; Cummins, The hound and the hawk, 84; Naomi Sykes, ‘European fallow deer’, in Terry O’Connor and Naomi Sykes (eds), Extinctions and invasions: a social history of British fauna (Oxford, 2010), 51–8: 51–2, 57.

26 H.S. Sweetman (ed.), Documents relating to Ireland, 1171–1307 (5 vols, London, 1875–86), vol. 1, no. 477.

27 O’Sullivan Beare, The natural history of Ireland, 77.

28 Cummins, The hound and the hawk, 84.

29 Beglane, ‘Deer in medieval Ireland’, 150–2.

30 Cummins, The hound and the hawk,41–3.

31 Richard Thomas, ‘Chasing the ideal? Ritualism, pragmatism and the later medieval hunt in England’, in Aleksander Pluskowski (ed.), Breaking and shaping beastly bodies: animals as material culture in the Middle Ages (Oxford, 2007), 125–48: 128.

32 Thomas, ‘Chasing the ideal?’, 128.

33 Naomi Sykes, ‘Taking sides: the social life of venison in medieval England’, in A. Pluskowski (ed.), Breaking and shaping beastly bodies: animals as material culture in the Middle Ages (Oxford, 2007), 149–60: 150.

34 Fergus Kelly, Early Irish farming: a study based mainly on the law-texts of the 7th and 8th centuries AD (Dublin, 2000), 275–6.

35 S.J.M. Davis, The archaeology of animals (London, 1987), 25.

36 Umberto Albarella and S.J.M. Davis, ‘Mammals and birds from Launceston Castle, Cornwall: decline in status’, Circaea 12:1 (1996), 1–156: 32–4; Thomas, ‘Chasing the ideal?’, 125–48; Richard Thomas, Animals, economy and status: the integration of zooarchaeological and historical evidence in the study of Dudley Castle, West Midlands (c. 1100–1750) (Oxford, 2005), 60, 63; Sykes, ‘Taking sides’, 149–60.

37 Thomas, ‘Chasing the ideal?’, 134–8.

38 Sykes, ‘Taking sides’, 155–7.

39 See for example, Sweetman, Documents relating to Ireland, vol. 1, no. 926.

40 Patricia Lynch, ‘Human and animal osteoarchaeological bone report: High Street, Trim Co. Meath 06E0148’, unpublished report for Carmel Duffy, 2007.

41 Beglane, Anglo–Norman parks in medieval Ireland.

42 Williamson, Rabbits, 11.

43 Williamson, Rabbits, 12, 17.

44 Williamson, Rabbits, 11, 17; J.B. Doughert (ed.), Report of the deputy keeper of the public records of Ireland (59 vols, Dublin, 1869–1921), vol. 39, 62.

45 Williamson, Rabbits, 31, 47–53.

46 www.excavations.ie (17 January 2015).

47 K.D. O’Conor, ‘Medieval rural settlement in Munster’, in John Ludlow and Noel Jameson (eds), Medieval Ireland: the Barryscourt lectures I-X (Cork, 2004), 225–56: 237.

48 David Stocker and Margarita Stocker, ‘Sacred profanity: the theology of rabbit breeding and the symbolic landscape of the warren’, World Archaeology 28:2 (1996), 265–72: 267–8.

49 See for example Charles McNeill (ed.), Calendar of Archbishop Alen’s Register c. 1172–1534 (Dublin, 1950), 30, 44, 178, 180; Paul MacCotter and K.W. Nicholls (eds), The pipe roll of Cloyne (Rotulus pipae Clonensis) (Middleton, 1996), 249–50; James Mills (ed.), Account roll of the priory of the Holy Trinity, Dublin, 1337–1346 (Dublin, 1891), 111.

50 Anton Ervynck, ‘Following the rule? Fish and meat consumption in monastic communities in Flanders (Belgium)’, in Guy De Boe and Frans Verhaeghe (eds), Environment and subsistence in medieval Europe. Papers of the medieval Europe Brugge 1997 conference (Zellik, 1997), 67–81: 76.

51 Trinity College Dublin, CIRCLE, A calendar of Irish chancery letters, CR 17 Rich. II, 11 November 1393.

52 Stephen Harris and D.W. Yalden, Mammals of the British Isles: handbook (4th edition) (Southampton, 2008), 220–8.

53 Cambrensis, Topographia Hiberniae, 48; O’Sullivan Beare, The natural history of Ireland, 79; Francois Avril (ed.), Livre de chasse: the book of the hunt by Gaston Phoebus (Paris, n.d.), CD-ROM: ff12v–13r.

54 Sweetman, Documents relating to Ireland, vol. 1, no. 1829.

55 Emily Murray and Finbar McCormick, ‘Environmental analysis and the food supply’, in Jenny White Marshall and Claire Walsh (eds), Ilaunloughan Island: an early medieval monastery in County Kerry (Dublin, 2005), 67–80: 68; Emily Murray, Finbar McCormick and Gillian Plunkett, ‘The food economies of Atlantic island monasteries: the documentary and archaeoenvironmental evidence’, Environmental Archaeology 9 (2004), 179–88: 184.

56 Alexander Fenton, The Northern Isles: Orkney and Shetland (Edinburgh, 1978), 525.

57 Wildlife Extra, Inland seals: seals reported in Cambridgeshire and Worcester [Online] (2013). www.wildlifeextra.com/go/news/inland-seals.html#cr (last accessed 10 December 2013); R.W. Baird, ‘Status of harbour seals, Phoca vitulina, in Canada’, Canadian Field-Naturalist 115:4 (2001), 663–75: 664.

58 Harris and Yalden, Mammals of the British Isles, 563–4.

59 Schlag, The hunting book of Gaston Phébus, 26.

60 McCormick, ‘Early evidence for wild animals in Ireland’, 361.

61 O’Sullivan Beare, The natural history of Ireland, 79.

62 See for example J.T. Gilbert (ed.), Chartularies of St. Mary’s Abbey, Dublin, with the register of its house at Dunbrody, and annals of Ireland (Dublin, 1884), 375.

63 O’Sullivan Beare, The natural history of Ireland, 79.

64 Paula Correa, ‘The fox and the hedgehog’, Phaos 1 (2001), 81–92: 85.

65 Fiona Beglane, ‘Deer and identity in medieval Ireland’, in Aleksander Pluskowski, Gunther Karl Kunst, Matthias Kucera, Manfred Bietak and Irmgard Hein (eds), Viavias 3. Animals as material culture in the Middle Ages 3: bestial mirrors: using animals to construct human identities in medieval Europe (Vienna, 2010), 77–84; Beglane, Anglo–Norman parks in medieval Ireland.

66 Pierre Bourdieu, ‘The forms of capital’, in N.W. Biggart (ed.), Readings in economic sociology (Oxford, 2008), 46–58: 46–58.

67 Aleksander Pluskowski, ‘The social construction of medieval park ecosystems: an interdisciplinary perspective’, in Robert Liddiard (ed.), The medieval park: new perspectives (Macclesfield, 2007), 63–78: 63.

68 See for example Sweetman, Documents relating to Ireland, vol. 1, no. 3076.

69 Davis, The archaeology of animals, 25.

70 Ervynck, ‘Following the rule’, 71–3. Anton Ervynck, ‘Orant, pugnant, laborant. The diet of the three orders in the feudal society of medieval north-western Europe’, in Sharyn O’Day Jones, Wim Van Neer and Anton Ervynck (eds), Behaviour behind bones: the zooarchaeology of ritual, religion, status and identity (Oxford, 2004); 215–23: 216–17; Barbara Harvey, ‘Monastic pittances in the Middle Ages’, in C.M. Woolgar, Dale Serjeantson and Tony Waldron (eds), Food in medieval England: diet and nutrition (Oxford, 2006), 215–27.

71 Marcelle Thiebaux, ‘The mediaeval chase’, Speculum 42:2 (1967), 260–74: 264–5; Cummins, The hound and the hawk, 10.

72 See for example McNeill, Archbishop Alen’s register, 30, 44, 170–2, 173, 178, 180, 195; Mills, Account roll of the priory of the Holy Trinity; 111, Sweetman, Documents relating to Ireland, vol. 1, nos 316, 477, 1336.

73 Mills, Account roll of the priory of the Holy Trinity, xiii, 117.

74 Fiona Beglane, ‘Report on faunal material from Bective Abbey, Co. Meath. Licence No. E4028’, unpublished report for Geraldine Stout, 2013.

75 Sykes, Taking sides’, 156–7.

76 Melitta Weiss Adamson, Food in medieval times (Westport, 2004), 102; S.A. Epstein, Wage labour and guilds in medeval Europe (Chapel Hill, NC, 1991), 128.

77 Bridget Henisch, The medieval cook (Woodbridge, 2009), 93–5.