‘Whipt with a twig rod’: Irish manuscript recipe books as sources for the study of culinary material culture, c. 1660 to 1830

John Hume Institute for Global Irish Studies, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4

[Accepted 1 September 2014. Published 12 March 2015.]

Abstract

From the mid- to late seventeenth century on women from the elite classes in Ireland started to write and exchange recipes, which they recorded in domestic manuscripts. Cultural imports to Ireland at this time, these manuscripts are excellent sources for the study of food, giving us a window into the early modern kitchen during a period of great culinary change. This paper will begin by briefly outlining the development of recipe writing as a genre in Ireland, considering issues such as chronology, authorship and content. The second part of the paper will focus more specifically on what these sources can tell us about material culture relating to cookery within high-status Irish homes of this period. By considering the objects mentioned, as well as the way in which they were described, the paper will discuss not simply what people owned, but also, what patterns of naming can tell us about these people’s changing relationships with goods, and an emerging consumer identity.

Introduction

During the seventeenth century women from elite backgrounds in Ireland started to write and exchange recipes—a practice which was common over the next 200 years. The manuscripts in which they recorded these recipes are an excellent source for the study of food and the material culture of the kitchen, from the mid-seventeenth century to the close of the Georgian period (1830). Furthermore, they reveal a great deal about the lives of the individuals who wrote these books, their work, concerns and social networks. This paper will briefly outline the development of recipe writing as a genre in Ireland, and what it reveals about material culture relating to cookery within high-status Irish homes. By focusing on the objects mentioned in manuscript recipe books, and the way in which those objects were described, the paper will engage not simply with what people owned, but also with how their relationships with goods and, ultimately, their worldview, evolved. Over the course of the eighteenth century people began to exhibit a heightened engagement both with food and the objects associated with it. Historical archaeologists have, to date, focused on the material culture associated with dining and food service as evidence of this rise in materialism and consumerism,1 but, as this analysis will demonstrate, these same patterns are also observable in the production and preparation of food, as instructed by contemporary recipe books.

Food and recipe writing in Restoration and Georgian Ireland

Recipe writing2 commenced in Irish houses in the mid- to late seventeenth century, and was maintained at a steady pace until the late eighteenth century. From the 1780s their number increased markedly and accelerated further over the course of the nineteenth century.3 Despite the fact that manuscript recipe books are in many ways a distinct genre, in that they obey a basic cultural template, include similar categories of material and frequently share stylistic norms, it would be wrong to see them as homogenous. Each manuscript is a distinctly personal and flexible object in its own right, and it was structured and written according to its various owners’ needs, which may have changed over time. So, manuscript recipe books from Ireland vary dramatically in physical terms, ranging from elaborately decorated organised volumes, which do not show signs of daily use, to rough folders of notes which assisted in the running of a busy kitchen. The manuscripts also vary greatly in terms of their content. They may include writings on a host of subjects beyond food-related recipes, such as cures and prescriptions (an integral part of the genre); beauty, gardening and housekeeping advice; newspaper clippings; scientific, Biblical and literary excerpts; household accounts; table and menu plans; sketches and drawings; and even diary entries.4

In terms of authorship, prior to the Victorian period the authors were almost exclusively members of the elite classes, and were predominantly women. Servants and men certainly made contributions, and we see recipes attributed to them, but there is no clear evidence that they were generally the primary authors in Ireland. There are numerous manuscripts written by anonymous hands, so of course there is the possibility that the identity of authors was more diverse, but as the class and gendered pattern observed in Ireland is consistent with studies from Great Britain and the United States of America,5 it seems fair to say that elite women were the primary producers of recipes in the period under review.

It is generally true to say also that the authors were primarily from ‘New English’ families, who had settled in Ireland from the sixteenth century on. This is not to say that families of ‘Old English’ and Gaelic origins did not participate in recipe writing, but it was certainly a new and imported practice for them, as there was no tradition of this in Ireland. It was also an adopted custom which could help them to absorb English culinary norms as necessary. Significantly, the recipe books in the collection of the Inchiquin O’Briens of County Clare, who were one of the most important Gaelic noble families in Ireland, were largely written by English women who married into the family. These women brought their cultural traditions with them at a time when it was necessary for the O’Brien family to adopt central elements of English culture, and food and foodways were fundamental to that process. For example, one of their exquisite volumes, which was in use for generations, was probably started by Catherine O’Brien (née Keightley), who was born in Ireland, but whose family and connections were chiefly English aristocrats. There is also a possibility, based on a later attribution, that this manuscript contains sections transcribed from Catherine’s mother, Lady Frances Keightley’s (née Hyde) earlier volume.6 Lady Keightley—the youngest daughter of Edward Hyde, the first earl of Clarendon—came to Ireland after her marriage. Her sister was the duke of York’s (later James II) first wife, meaning that Lady Frances was the aunt of both Queen Mary II and Queen Anne.7

Jane Ohlmeyer has recently discussed the role of marriage as an important means whereby elite Gaelic and Old English families became both anglicised and ‘civilised’, and were enabled to retain their position and status at a time of great social flux. According to Ohlmeyer, it was hoped that English women would teach the next generation of Irish elites their language, culture, manners and religion; ultimately, that they could ‘make Ireland English’.8 Based on my analysis of surviving family papers in the National Library of Ireland, it is clear that, upon coming to Ireland, many women brought their food culture with them, and that manuscript recipe books, which had been an established genre for generations in Britain, were an important component of that.

The cultural significance of recipe writing in Britain was not limited to manuscript keeping; it can also be seen in the production and consumption of printed texts. While they are by no means a genre unique to England, published recipe books were hugely popular in that country and more titles were produced there from the seventeenth to nineteenth century than elsewhere. The popularity of published recipe books also helped to forge a distinctly and consciously British cuisine.9 These published models not only influenced food and cookery, but also the writing behaviours of elite women, encouraging a lively manuscript culture within houses. As women’s gender roles came to be redefined in Britain, and a less active role in the running of the house was promoted, in line with the genteel and meek model put forward in the Georgian period,10 writing became a central component of housewifery.11 A literate and yet passive mistress sitting at her desk was much more desirable than one with her sleeves rolled up sweating away in the kitchen, and so writing household manuals became a central component of this idealised femininity. Considering the identity of the authors, the nature of manuscripts, the distinctly British cuisine that they promote and the chronology of their arrival in Ireland, it seems reasonable to say that recipe writing was an important signifier of class, culture and gendered identity for the new arrivals, and that it subsequently became one for the elite classes already established here.12

The recipes

As with the genre itself, the recipes contained within seventeenth- and eighteenth-century manuscripts reflect the close cultural connection that existed between the authors of these manuscripts and the English upper classes.13 The most important point to make is that the food, tastes and fashions are remarkably similar to those represented in contemporary English recipe manuscripts and published books. There is a basic suite of recipes which are common and obey a general cultural template. Only a few recipes can be seen as particularly ‘Irish’ in any real sense. One such example appears in the mid- to late eighteenth century section of a volume authored by women from the Inchiquin O’Brien family:

To make an Irish stew of mutton

Season the bones of a neck of mutton with pepper and salt, put it down with a layer of onions, put them in covered stewpan, to keep in the steam & as much water as will cover it—the chops must be very tender but as they are all put down together, the potatoes must be taken out first, as they burst.14

Notwithstanding examples such as this, the rarity of expressly ‘Irish’ recipes says much about the nature of the culinary culture of the Anglophone elite of society. The manuscripts depict the cuisine, or at least that which was aspired to, of the elite classes, and they need to be interpreted in that context. Furthermore, the commonalities that they share with English manuscript and printed recipe books indicates that authors from Ireland had access to, and were inspired by, English texts.15 In some instances we have direct evidence for the influence of printed models. For example, Jane Burton’s eighteenth-century manuscript diligently references the original authors of the recipes it contains. Her volume includes recipes attributed to famous published authors such as William Ellis and Hannah Glasse, as well as excerpts from the Scot’s Magazine.16

The chief classes of recipes recorded can be categorised as sweet dishes (a large category which can be broken down further as discussed below), savoury dishes, preserved goods, alcoholic beverages, bread making, dairying advice and substitutes for expensive ingredients. Culinary historians may choose to group these recipes differently and more precisely. Ultimately, there are countless ways of breaking down a recipe book depending on the type of questions one seeks to ask. My intention here is to consider the broad ‘function’ of a recipe in terms of running an efficient and fashionable household. The function may have been to assist in the creation of a rounded and phased meal system based on contemporary fashions, with sweet and savoury flavours required at different stages. Alternatively, a recipe’s function may relate to how it assisted with the completion of certain household tasks and provisioning (bread making, distillation, food preservation and dairying). Each of these categories will be outlined below in order of the frequency of their presence. This will help to illustrate the nature of the recipes within the manuscripts, and will demonstrate their similarity with British models.

Sweet dishes are by far the most common category of recipe in Irish manuscript recipe books of this period. This large category can be broken down more meaningfully into baked goods, whipped and set desserts, and confectionery. Sweet baked goods, which were served at breakfast, with tea or at the end of the meal, depending on the recipe, are standard inclusions. Such recipes include cakes, biscuits and macaroons (Pl. I). Although not strictly baked and therefore somewhat distinct, steamed puddings can also be put into this broad grouping in terms of their function within the meal system. The following example, which comes from a seventeenth-century manuscript from the collection of the Smythe family of Barbavilla, Co. Westmeath, demonstrates one such recipe from this category:

A caraway cake

A quarter of a peck of flower dryed [sic] a pound of butter a pound of caraway comfits a pint of cream a pint some sake [sack] of yest [yeast] ye yolks of 6 eggs on nutmeg mingle it when you begin to heat your oven and let it rise and when you go to put it in mingle in the caraways.17

PL. I—Recipe for ‘Ratifie puffs’ from the National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 41,603/2 (2 of 2), Papers of the Smythe family of Barbavilla, Co. Westmeath. Courtesy of the NLI.

This example demonstrates a cake very typical to the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, both in terms of flavour and method. Such recipes are found throughout the Irish collection and are also common in contemporary British examples.

Whipped and set treats such as blancmanges, jellies, creams, syllabubs, flummeries and possets, which would mostly have been served as desserts at the end of the meal, are also common. A vast range of different types of confectionery such as candied fruits and flowers were familiar, conserves and marmalades (‘marmalets’) were popular too. These may also be seen as forms of preservation, albeit expensive ones given the high cost of sugar, particularly in the earlier part of the study period.

Recipes associated with food preservation are the second most common category, and they demonstrate the importance of this task. Meat and fish could be salted, smoked, potted and pickled. Fruit and vegetables were preserved as jams, marmalets and conserves (also forms of confectionery), but also as chutneys, pickles and even powders. The following recipe is taken from a second volume written by members of the Smythe family of Barbavilla:

To pickle cauliflowers

Take the clossett [sic] and whitest cauliflowers that you can and break them into little knots as you please then put them into salt and water as much as will cover them let it be as strong as will bear an egg and let them stand in it 48 hours then drain them well from the brine and have as much white wine vinegar as will cover them boiled with some nutmeg cut in quarters and some mace so pour it boiling hot upon yr cauliflowers cover them up close and in 3 or 4 days they will be fit to eat.18

This example demonstrates just one of the numerous entries for a wide variety of pickled vegetables which appear in manuscripts from the seventeenth century on, most of which use a similar method.

Savoury recipes, which would have formed part of the main meal, are the third most frequently occurring recipe type. Soups, broths, forced meat, roasts, stews, puddings and pies are commonly encountered. ‘Ragoos’, ‘fricassees’ and ‘cullis’ are also regular inclusions and attest to the influence of courtly French food fashions on the cuisine of the elite classes in Britain and Ireland in this period.19

Alcoholic beverages are the next major recipe category. These include various types of flavoured wines, liqueurs, mead (or ‘meath’), cordials and ales (Pl. II). The proliferation and diversification of such recipes demonstrates that there was an active brewing and even distilling culture within elite Irish houses during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The final three categories are encountered infrequently. These include recipes for bread making, which appear on occasion, but are not common place. Other sources, such as account books, tell us that many baked goods, but particularly bread, were frequently bought in ready-made. Furthermore, the absence of bread recipes may relate to the purpose and use of recipe books. As Carol Gold has observed in her analysis of Danish published cookery books dating from 1616 to 1901, the recipes found within such manuals tend to record information and directions with respect to recipes that people need assistance with. Gold, one of the only scholars to have written on this subject, suggests persuasively that baking bread was such a commonplace daily task that it did not require written instruction.20 The next of these infrequent categories is dairying (mostly relating to soft cheeses in this period) (Pl. III), and the rare but intriguing category of creating substitutes for expensive luxury ingredients such as tea, coffee and chocolate.21 For example, the recipe book by Jane Burton includes directions for ‘Artificial Coffee’ which instructed the reader to burn a piece of bread until it was black, grind it, and add it to hot water.22

PL. II—‘To make orange wine’ from the National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 14,786, Inchiquin Papers. Courtesy of the NLI.

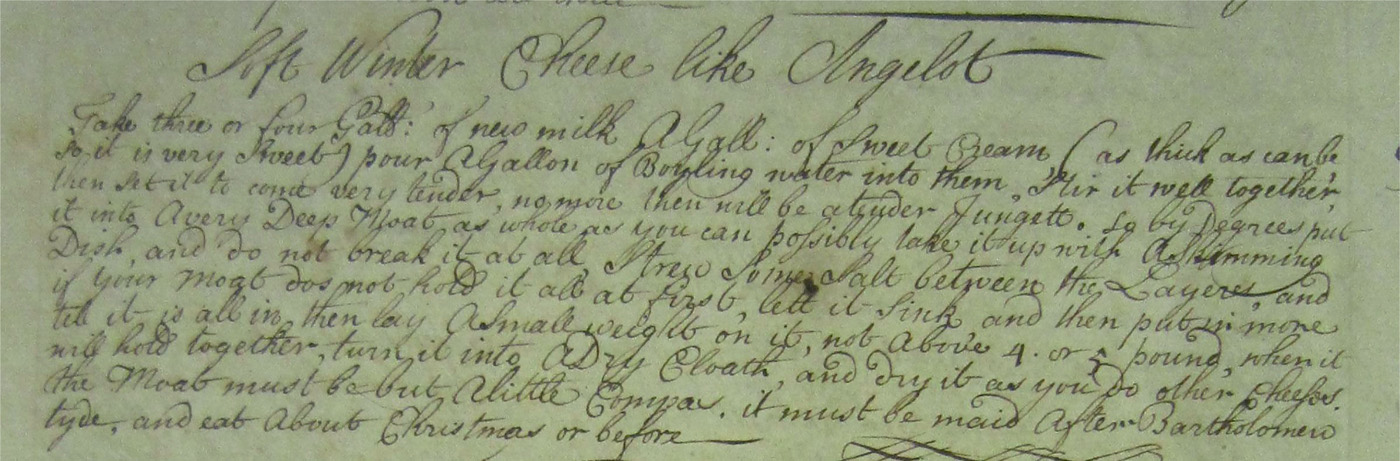

PL. III—‘Soft winter cheese like Angelot’ from the National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 14,786, Inchiquin Papers. Courtesy of the NLI.

It is evident from this brief outline of the recipe types recorded in the Irish recipe books that the cuisine represented was broadly similar to that consumed in Britain at the time. The elite classes in Ireland shared a common cuisine with their British counterparts, just as many of them shared ethnicity, marriage bonds, language, religion, architecture and other aspects of culture. This should not be seen as particularly surprising given that they had such close familial and cultural bonds with their counterparts there. What is interesting though, is how the practice of recipe writing was used to articulate this close cultural and class connection across the water. The elite classes did not simply import a cuisine alone, but also an important and fashionable cultural object, which was an integral part of the food system—the recipe book. This was an item closely associated with the British household, foodways and gendered identity. As discussed earlier, recipe writing was a well-established practice in upper-class-British households, and it was one that helped to forge a consciously British cuisine, as well as a new model of idealised femininity characterised by the image of the passive, genteel and literate housewife. In this sense then, both the dishes conveyed within recipe books from this period, as well as the very mode of communication itself, were means through which a definitively English food culture was established in Ireland.

Manuscript recipe books as sources for the study of material culture

Manuscript recipe books contain a high level of detail on life within Irish houses from the mid-seventeenth century. As stated earlier, they contain a range of different types of information in addition to the recipes themselves, and it is perhaps surprising that they have not yet been scrutinised in more detail by archaeologists and historians interested in material culture. Manuscript recipe books help us to understand not simply what items were expected to be in the kitchen, but also how they were used. They show us that simple objects often had a variety of functions. Past studies of material culture relating to kitchens have shown that items associated with food processing, not just food service, proliferated during the eighteenth century in England.23 The analysis that follows demonstrates that a similar pattern can be identified in Ireland. Finally, they also indicate that kitchens contained a range of inexpensive organic and naturally occurring materials which were regularly used in a variety of tasks. As they were of little value, such items would rarely have been mentioned in inventories. They would be difficult to detect archaeologically, making recipe books, which can tell us a great deal about the range of ephemeral, cheap and disposable items not generally discussed elsewhere, an invaluable source.

The remainder of this paper will focus on the objects mentioned in ten recipe books.24 As the table below, which lists the objects mentioned in a recipe book maintained by members of the Inchiquin O’Brien family between the late seventeenth and mid-eighteenth centuries, demonstrates, manuscript recipe books from this period contain a wealth of information in relation to cookeryrelated material culture. Comparable lists were made for each of the ten casestudy manuscripts, with a view to characterising the contents of kitchens over time.25 These lists help us to consider how the equipment within kitchens may have changed during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but they also indicate changes in the way in which people described material culture over time, notably an increasing trend towards specification in terms of size, form and composition. However, before continuing in this discussion, some of the challenges of using these sources in this manner must be outlined.

TABLE—List of items mentioned in food-related recipes and inventories in the National Library of Ireland manuscript, Ms 14,786, from the Inchiquin Papers.

| Objects mentioned in NLI, Ms 14,786 | ||

| bag | bag, flannell | bag, jelly |

| bag, paper | barrel | bason |

| bason, cheney | bason, earthen or silver | bason, large white |

| bason, silver | bladder | board, [. . .. . . ] round |

| boards | bodkin | bottle |

| bottle, china | bottle, wide mouthed | bottle, wide mouthed glass |

| bowl | bowl, black and white | bowl, large coulerd |

| bowl, plain | bowl, small Japend & covers | box |

| bread basket | candels | candlesticks |

| canvas | cheese bason | cheese cloath |

| cheese-vat | chocolet mill | churn vessels |

| cloth | cloth, coarse | cloth, fine |

| cloth, straining | cloth, thin | cloth, very thick |

| coffee pott and plate | cork | crock, glazed |

| crock, small | cullender | cullender, earthen |

| cup | cup, chocolate | cup, tea |

| cups, large chocolate china, netted over | cups, large coulerd burnt china with cover | cups, large with covers |

| cups, [. . .. . . ] stone | cups, white chocolate cups with raised flowers, china | decanters for water without covers |

| decanters with covers | dish | dish, broad silver |

| dish, china | dish, deep | dish, earthen |

| dish, large coulerd | dish, long lobster china | dish, pewter |

| dishes of blue china, four different sizes | dishes, round coulerd and gilt | dishes, shallow |

| drudging box | fish kettle | flannell |

| flat drying pans | flat iron | forks |

| frying pan | glass | glass, deep |

| glass, large | jar, large blue & cover | jar, large coulerd & cover |

| jar, stone | jug | kettle |

| knife | knife, very sharp | ladle, punch |

| ladle, soup | leather | linen, very thin |

| milk pan | mille | mortar, marble |

| mortar, stone | muslin | napkin |

| needle, great | paile | pan |

| pan, earthen | pan, large | pan, tin |

| paper, white | papers | papers, brandy |

| paper coffins, little square | patty pans | pepper box, small |

| pin | plate, thin | plates |

| plates, coulerd and gilt | plates for caudle cups | plates, octogon blue and white |

| plates, square of old china | plates, tin | platter |

| porringer | pot, deep earthen | pot, earthen & well glazed |

| pots | pottles | preserving pan |

| preserving pan, copper | pressing pan | punch bowl, large |

| punch bowl, small | quill | rolling pin |

| salamander | sallatt dishes, long blue and white | salvers, round |

| sauce boats | sauce pan | saucers |

| saucers for chocolate china cups | saucers, small deep | saucers, [. . .. . .]stone |

| sa[u]cers, three cornered | scallop shells | shape |

| sieve | sieve, coarse | sieve, fine |

| sieve, hair | sieve, large | sieve, silk |

| silver knives | silver thing | skillet |

| skimmer | skimming dish | skimming dish full of holes |

| soop dish | soop tureen | soup dish, very large coulerd china |

| soup kettle and cover, large | soup terene with a cover | spoon |

| spoon, copper or plate | spoon, dessert | spoon, marrow |

| spoon, table | spoon, tea | stand for middle of table |

| stew pan | stew pan, broad | stew pan, small |

| sticks | strainer | strainer, canvas |

| string | tankards with lids | tea kettle and lamp |

| tea pot | tea pot, [. . .. . . ] stone | [tea?] pott, blue and white with a silver spout |

| tea pot, old brown in the shape of a crab | tea pott, old cracked | tea pot, small old china brown |

| tea pott, very large brown | [tea?] pott, very small blue with a silver spout | thread |

| tray for the snuffers | tub | tub, little |

| tundish | vats, small | vessel |

| vessel, deep | vessel, earthen | vessel, silver |

| wafers or papers of any shape you like | water bottle, coarse china | weight |

| weight, quarter of a hundred | weight, two or three pound | whisk |

Firstly, a recipe and an inventory are not the same, being compiled for fundamentally different purposes. A recipe book does not necessarily tell us what people owned at a point in time as an inventory does; rather, it tells us what they were expected to own. However, given that these were personal texts, we can be confident that they present a more accurate guide as to what was in the kitchen than published books.26 An individual may have taken down notes on a recipe which they never subsequently made, but it would be odd for them to have listed a range of expensive items required in their own book if they had no expectation of having access to them. In truth, they are theoretical inventories rather than actual ones. That said, it would be wrong to ignore the information recorded within these books relating to material culture. Food historians have not shied away from using them as sources simply because the food was not necessarily an accurate reflection of everyday meals; they have simply taken cognisance of that fact and used them cautiously.

Secondly, it is difficult to generate a meaningful database of items linking different manuscripts. Many books were kept in use for generations, with the result that the items mentioned in them may demonstrate change over time. Furthermore, as precise dates cannot be ascribed to all entries, it is rarely possible to generate precisely dated lists in the way that it is possible for individually dated inventories. Similarly, recipe books vary dramatically in length. Since some contain merely a handful of recipes, they refer to a few items only. For these reasons, and because these were ultimately profoundly personal items, it is best to interpret any list of material culture within the context of each book and if possible, each house and period in which it was made. With this understanding, we may hope to identify patterns of change from house to house, which are chronologically and socially grounded.

In the account of kitchen artefacts that follows, I have attempted to uncover some broad patterns of change based on the goods mentioned. This is less about quantitative analysis, and more about looking at the way in which people described material culture over time, and what this says about their relationships with those objects. It has been arranged in terms of categories of kitchen tasks: food storage, ingredient measurement, food preparation, cooking and food service.

Food storage

A variety of different types of food storage vessels are mentioned in each of the ten manuscripts, and there is a general consistency in the terms employed to describe them throughout the period. The generic term ‘vessel’ was commonly used; sometimes with added information regarding material or size, but more specific objects are mentioned as well. Barrels, which are regularly referred to, were used primarily to store alcohol, but stored larger preserved goods like hams as well. Kegs and casks were also used for alcohol storage, but unlike the term barrel, more information is included about their nature. Descriptive terms for casks refer to the type of wood desired, such as oak, or the method of manufacture, with some recipes calling for a cask with ‘iron hoops’.27 Other recipes call for casks that are scented or for those suitable for the storage of specific drinks such as sherry or brandy. So, whereas the term ‘barrel’ appears to have been used as a generic large storage container, ‘kegs’ and ‘casks’ are terms which applied to more specialised uses.

Smaller quantities of alcohol and other beverages were stored in bottles, but they were also used to store preserves, pickles and condiments. So, given that bottles were multipurpose small storage containers, more specific advice is often provided to indicate which type was needed. The size and shape of bottles is commonly specified in recipes (such as quart, large, wide mouthed) and sometimes the material that is preferable for a particular recipe is mentioned (such as china, glass, stone). There does not seem to be any remarkable pattern observable here in relation to the recipes themselves, but it is significant that from the later eighteenth century on there is a much wider variety of descriptive terms, with a range of different adjectives applied to bottles from the second-half of the eighteenth century (coarse, china, wide-mouthed, wide-necked, water, glass, stone, quart, large, small). When we consider that seventeenth-century manuscripts rarely employ adjectives for bottles, there is a clear observable pattern here, the meaning of which could be explained in two ways. Firstly, this may be evidence that people had an increasing range of objects in their houses and at their disposal which, given what past studies have shown regarding the proliferation of goods in this period, seems likely.28 Secondly, this pattern may also demonstrate an increasing fixation with material goods, and a more prescriptive mentality on the part of recipe writers. There was a growing compulsion to specify exactly what type of object should be used, coupled with a raised interest in the different properties of each of the varieties available.

Crocks are another storage item referred to in all the manuscripts and throughout the period under review. They were most commonly associated with butter storage, but they had a variety of other storage uses as well. ‘Earthen’ is the only descriptive term employed in reference to crocks in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century entries, but by the later eighteenth century they are described both in terms of their composition (earthen, stone), finish (glazed, black-glazed) and form (deep, large, wide-mouthed, closed-mouthed, with cover). So again, there is evidence not only that a greater range may have existed, but also that writers were becoming much more specific. Crocks were also used in cookery, so, like many items, they appear to have been important multifunctional objects in the kitchen. Clare McCutcheon and Roseanne Meenan have discussed the multifunctional use of black-glazed crocks and utilitarian ceramic vessels for storage and preservation purposes in their recent review of domestic pottery. They describe the large black-glazed vessels with heavy rims and horizontal lug handles commonly found on excavations relating to this period, citing Dublin Castle as one such example. It is likely that some of the forms mentioned in recipe books correspond to the artefacts found on such sites, both sources informing our understanding of the nature and use of objects in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century kitchen.29

Pots and jars are other frequently mentioned multi-use storage items. Seventeenth-century pots are described as deep, earthen, glass or well-glazed, but the term ‘jar’ was not employed in manuscripts until the mid- to late eighteenth century. Jars were then described in a variety of ways, including earthen, glazed, large, blue, covered, coloured, small-mouthed, wide-mouthed, stone, sweet and half-pint. Pots from this later period are similarly given a wide range of adjectives relating to their size, material, form and function. ‘Gallipots’ (also galy pots) are mentioned occasionally as well. These are generally thought of as small earthenware jars for storing ointments and medicine, but as McCutcheon and Meenan have suggested, many were used for food storage as well,30 and this analysis strongly supports their assessment. Tundishes are also cited throughout the period and, although they are not storage vessels themselves, they were used like a funnel, to fill other containers. Finally, a large variety of vessels and storage containers such as vats, boxes, jugs, pitchers, basins, dishes, pottles, tubs and glasses are encountered. Many of these had a range of functions in the preparation and serving of food. Corks, string, fabric and paper were commonly called upon to seal vessels.

Ingredient measurement

The measurement of ingredients tells us a great deal about the way people used and followed recipes, the cook’s assumed skill level, the degree of specification they required, and the level of authority assumed by the author. Units of measurement for weight and volumes such as pounds, ounces, bushels, pints, quarts, gallons, pottles, mutchkins, chopins, naggins and hogsheads were commonly employed. However, the utensils used to measure these amounts are rarely mentioned, although some of the measurement terms were interchangeable as objects in their own right. Physical weights to help measure quantities are referred to very occasionally, but little can be said regarding how frequently they were actually used. The term ‘table spoon’ is used in seventeenth-century recipes as a unit of measurement, but the term ‘tea spoon’ does not appear until the mid-eighteenth century. During this period these gradually became formal units of measurement, but it is not clear how standardised they were at this time. Other ingredient quantifications are less formal, but still relatively precise. For example, recipes from the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries sometimes call for the quantity of spice that would cover a shilling. Less precise still are references to generic spoons, cups and glasses, which were not yet standardised measures. Sometimes the recipe quantified the amount of a given ingredient required in terms of cost, such as a penny or shilling’s worth of an item, which could have resulted in dramatic variation depending on market fluctuations over time. Finally, recipes from all manuscripts frequently called for ‘pinches’ and ‘handfuls’ of an ingredient and for seasoning, spice or sugar simply ‘to your taste’.

The principal findings regarding the units and utensils of measurement employed in recipes are that this is a transitional period between a more organic system of quantification, which relied on the cook’s discretion and skill, and a modern system which reflected empirical science. The recipes are by no means fully fledged ‘modern recipes’ with precise measurements for every ingredient, but there was movement in that direction, and terms such as ‘tablespoon’ and ‘teaspoon’, which are central to modern cookery, were beginning to appear with increasing regularity. By the mid-Victorian period the changes noticed in this earlier phase had reached their ultimate expression, by which time recipes had become much more prescriptive and authoritative; less knowledge was assumed and more commands and instructions were given.

Food preparation

Common kitchen tasks such as mixing, whisking and whipping are mentioned frequently without guidance being provided regarding the specific utensils that should be used. Presumably, it was obvious what one should use to mix a batter and so on. There are some references to mixing and whisking utensils; these include spoons (sometimes wooden, but also metal), whisks and interestingly, twigs and sticks. The mention of organic objects is particularly important as these are largely undetectable archaeologically, and were too disposable to be mentioned in an inventory or similar historical document. It would also be interesting to know how often hands were used for tasks such as mixing as opposed to utensils, but the absence of specification makes this question difficult to answer.

Chopping, cutting and slicing are again common kitchen tasks for which you may expect a variety of related objects to be mentioned. Again, however, these appear to be so commonplace that recipes rarely suggest which items should be used. Knives and boards are mentioned, but are rarely described in more detail. However, in some instances, knives are described as silver, very sharp or thin.

Grinding and crushing were also important tasks in the kitchen. Mortars and pestles were used to grind a variety of ingredients, including sugar (which was still sold as solid sugarloaves), spices, herbs and nuts (usually almonds). Mortars and pestles were also vital in the preparation of medicines. Mortars are described as both stone and marble, but little more information is provided. Mills are mentioned and were also used to process hard ingredients. It is notable that chocolate mills are mentioned in one late seventeenth-century to early eighteenth-century manuscript, since chocolate was still a relatively new luxury ingredient at the time.31

A variety of vessels, many of which were multifunctional, were used to prepare and mix food. It is difficult to establish to what extent certain terms are interchangeable, but they include basons (basins), bowls, dishes and pans. Once again, size (deep, shallow, large, ‘common sized slop’32); material (wood, earthen, pewter, silver, brass, china); and quality (fine, coarse) are sometimes specified, depending on the recipe and the task at hand. For example, metal bowls made out of materials like brass, pewter and copper react with acidic ingredients, so earthenware was preferable for some recipes. Similarly, metal can be advantageous when whisking egg whites, so it is specifically recommended in other instances. It should be noted that, as observed in other categories thus far, the same pattern of increasing specification in respect to materials, size and form, from the later eighteenth-century on, is noticed in relation to these mixing vessels.

A variety of moulds from the eighteenth century are also listed. These were used to set the various sweet jellies and creams which were popular and fashionable dishes at the time. Moulds may also have held savoury dishes such as terrines, and they demonstrate the fashions for elaborate food presentation. Little information is included in respect of the shape and materials of the moulds themselves, but copper is specified on occasion.

Cloth was used for a wide variety of food preparation tasks and must have been a very common kitchen material. The kinds of tasks in which it was used include straining liquids, cleaning foodstuffs, rubbing during the salting and curing process, holding and steaming puddings, and cheese making. It was also used in storage to form bags and covers for vessels. Sometimes a recipe simply called for the use of a generic ‘cloth’ or ‘rag’, but additional information is given in some instances. From the mid-eighteenth century the type of fabric is sometimes specified, including muslin, linen, flannel, crêpe or canvas. In other instances, the quality or texture of the fabric is specified, such as very coarse, coarse, very thick or fine. Sometimes a specific object made of cloth is called for, such as a bag made from a particular type of fabric, a napkin or a salting glove. The criteria specified related to the task for which the cloth/cloth item was needed. For example, fine muslin would be employed when a liquid needed to be carefully sieved, whereas a coarse cloth was more ideal for rubbing salt into hams. Finally, different types of thread or string were used for a variety of tasks, including binding and stuffing meat, tying up bunches of herbs, and sealing containers for storage, amongst a myriad of other uses. The frequency with which cloth and string are mentioned is important, because they are the type of relatively cheap materials that are seldom mentioned in sources such as inventories, and they are rarely visible in the archaeological record. This means that manuscript recipe books give us a much more detailed image of the types of objects always within reach of the cook than we would otherwise be aware of.

Cloth was not the only object used to strain liquids and dishes. Colanders (‘cullenders’), strainers and a variety of different types of sieves were used to the same end. ‘Cullenders’ are sometimes described as earthen, and strainers as cotton, canvas or thin. Sieves are described in more detail as fine, coarse, hair, silk, wire and rod, all of which were called upon in different instances. Once again, the material and quality specified related to the task at hand.

Paper was another very commonly used material in the kitchen and it fulfilled a variety of functions. It could seal containers for storage, form a makeshift lid during cooking, line baking tins and be used as a baking case itself. A variety of different qualities of papers are mentioned, these include fine, white, brown, writing, coarse, strong, brandy and stiff card. Paper bags were also mentioned and were used in similar tasks to fabric bags.

Like cloth and paper, a variety of other organic and naturally occurring materials are mentioned throughout the manuscripts. Organic membranes such as bladders and leather are referred to regularly, and were used for many of the same tasks as the different fabrics. Twigs, sticks and rods were frequently used to mix and whisk. Even bunches of feathers were used on occasion, when extra care was needed in stirring things. Finally, straw, sand and pebbles were used, often in preserving and curing, or to help store perishables safely. References to the use of these naturally occurring and organic materials is significant, in that it helps to create a more detailed image of the contents of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century kitchens. Traditional archaeological evidence and more formal documents rarely provide evidence of these types of objects.

Another category of objects frequently mentioned in relation to food preparation are bodkins, needles, pins and skewers. These had a range of uses, but were commonly employed to test the ripeness of fruits and nuts. Multiple recipes explain that if a pin could be pushed through the centre of the fruit or nut, then it was ready to be used.

Finally, one particularly interesting object involved in food preparation mentioned in the late seventeenth- to early eighteenth-century is a ‘drudging box’ (dredging box).33 These were small boxes with a perforated lid that contained breadcrumbs or seasoned flour which could be sprinkled over the top of roasting joints of meat (Pl. IV). It was a method which was rarely used before the start of the eighteenth century,34 so the mention of this item in a manuscript of this age demonstrates that the kitchen was fitted with up-to-date and fashionable utensils. This same manuscript also contained a reference to a chocolate mill at a relatively early date.

PL. IV—Eighteenth-century brass dredger. © Madeline Shanahan.

Cooking

As we would expect, vessels which needed to withstand the heat of the fire, oven or stove were made of metal or were ceramic. Metal cookware mentioned in recipes throughout the period, from the late seventeenth century on, includes pots (‘bellmattle’, brass, tin); skillets (small, great, large, copper, brass); griddles; stewpans (broad, small); saucepans; cauldrons; a variety of pans (preserving, frying, brass, tin); and kettles. Fish kettles and omelette (omelet) pans are mentioned only from the mid-eighteenth century, and demonstrate the development of more specialised, highly functionalised forms in the kitchen. Ceramic cookware forms mentioned include earthen pans, crocks, pipkins, and pots in a variety of sizes, colours and finishes.

Vessels and items used for baking specifically are also mentioned. What we would think of as cake tins today were generally called ‘shapes’ in the manuscripts of this period. These shapes were commonly made out of tin. Copper and tin baking trays or ‘sheets’ are also mention, as are ‘bisket’ pans and patty pans, which were used to bake small cakes.

Food service

Given that recipe books focus more on food preparation than on serving, they provide considerably less information on tableware. However, a few types of vessels are described and the findings are consistent with past studies of such objects undertaken by historical archaeologists in Britain.35 Various vessels such as plates, dishes, trenchers, platters, basons, bowls, ewers, tureens and porringers were used to serve food. However, the references to them demonstrate that many of these terms could be used to refer to multiple, different items. The term ‘dish’, in particular, filled a variety of functions, being used to prepare, cook and store food. However, while ‘dish’ may be a general, ‘catch-all’ term, dishes were not all the same, and they were certainly not used for all purposes. Dishes made out of expensive materials such as silver, pewter and china are listed as serving vessels. Additional details regarding the size, shape and also the colour of ceramic dishes are sometimes provided. Occasionally, the exact food to be served in a dish is specified, so we see butter, soup, trifle and ‘sallat’ (salad) dishes mentioned from the seventeenth century. Lobster and stew dishes are mentioned in the eighteenth century. A variety of differently sized, shaped and coloured bowls are indicated too; these include cheney (decorated earthenware), and fruit and punch bowls from the mid-eighteenth century. The variety of different types of dishes with specific descriptions increased significantly over the period.

Glasses are another type of serving vessel which is mentioned frequently. They were used to hold a variety of jelly- and cream-based desserts, as well as beverages. ‘Jelly glasses’ and ‘wine glasses’ are specifically referred to throughout the period. Silver tankards and goblets are also mentioned, but relate specifically to alcohol consumption.

Chafing dishes were important for ensuring that food arrived to the dining room hot after the sometimes long journey from the kitchen. They also kept the food hot for the length of the meal itself. The manuscripts reviewed here provide little information regarding the material these dishes were made from, but excavated evidence can provide some answers. McCutcheon and Meenan state that ceramic chafing dishes were common from the sixteenth century and were still in use in the seventeenth century. However, there is evidence that metal forms of chafing dishes were in demand from the later seventeenth century.36

A variety of utensils for serving food at the table and types of cutlery have been identified. Ladles are referred to throughout the period and particular forms include punch ladles and soup ladles, which are specifically mentioned from the late seventeenth century. Silver cutlery forms such as spoons and knives are mentioned throughout the period, but forks only appear from the eighteenth century. This is consistent with our understanding of when forks came to be used regularly. Bríd Mahon has suggested that despite their earlier adoption elsewhere, they only came to be used in high-status Irish houses from the early eighteenth century.37 Specific forms of forks are also mentioned from the mid- to late eighteenth century, including dessert, oyster, silver and small forks. Fish, oyster and dessert knives are also mentioned in this same period. There was an even greater variety of spoons, including dessert, marrow, butter, dinner, dishing, egg, gravy, salt and soup spoons.

The emergence of a suite of highly specific serving ware utensils can also be traced over the course of the period in question. While highly specialised tableware such as sauce boats are mentioned in seventeenth-century entries, by the mid-eighteenth century we encounter items such as artichoke cups, asparagus tongs, plates with covers for fish kettles, egg cups and butter boats. Again, this is in keeping with studies which argue that these proliferated in the Georgian period.38

Finally, a suite of items associated with tea and coffee, including teacups, saucers, teapots, teaspoons, coffee pots, coffee urns and coffee cups can be identified. Chocolate pots, and chocolate cups and saucers are also mentioned, although less frequently. The early reference to these is interesting because these items and the beverages they were used to serve were relatively new and important luxuries at this time. Identifying the early use of them is significant, particularly as these became hugely important parts of class culture over the next century. Here we see their early use and absorption into the foodways of elite society, at a household and profoundly personal level.

Discussion

Manuscript recipe books are a rich and varied source for the study of foodrelated material culture in the Restoration and Georgian periods. They can be used to create detailed lists of objects, and to inform us about how those items were used, their multiple functions within the kitchen, the proliferation of forms over time and, significantly, the range of organic, cheap and natural materials that do not show up in excavations or inventories.

Across the categories of objects mentioned, a consistent pattern emerged. Over the course of the eighteenth century recipes mention a wider variety of goods, and they apply more adjectives and descriptive terminology to the goods that are required. This is consistent with a detailed study of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century probate inventories from the United States of America, made by Mary Beaudry. Her study concluded that terms for food-related objects were modified according to their function (mustard pot, posset pot, teapot and so on) with greater frequency by the middle of the eighteenth century in inventories.39

The pattern identified in Ireland shows that there was an increasing range of goods at the cook’s disposal, and perhaps more importantly, that the increasingly prescriptive terminology employed indicates that the authors were becoming more aware of the range of utensils, and more authoritative in their writing. This change can be interpreted in several ways. Firstly, it has been argued elsewhere that recipes became more authoritative and prescriptive generally, in this period, as there was an increasing loss of culinary knowledge within the house. As a result, cooks began to learn their skills from books rather than by apprenticeship, and so more instruction was required. This change was supposedly intensified as more and more mistresses took a less active role in the kitchen, and manuals stepped in to take on their instructive duties.40 As discussed at the start of this paper, as the idealised gender role of the passive and genteel housewife emerged, upper-class women were increasingly urged to distance themselves from ‘front-line’ duty in the kitchen, and so writing took on a new significance in the management of their homes. In this context we might expect an increasing need for specification in recipe writing, as mistresses could not indicate their precise commands through active demonstration. Usually, this argument is put forward in relation to an increase in precise measurements and more instructions,41 but the same could apply to more prescriptive language surrounding equipment as well.

While this is interesting, and may have been a factor, I believe that both the proliferation of recipe books, and their increasing exactitude had less to do with a genuine need for instruction, and more to do with a changing relationship with food and material culture, which was in many ways profoundly modern. The recipe books themselves helped to promote modern cuisine, but the conscious fixation with food, the need to write about, define, measure, categorise and standardise it, is both significant and meaningful. We can also look at changes in the way recipes were written as symptomatic of a standardising impulse and a heightened fixation with objects at this time. This interpretation is supported by the work of other historical archaeologists, who have examined a range of different categories of material culture and alternative genres of writing connected to them. For example, inventories and etiquette guides have been interpreted as genres which display a heightened concern with tracing and categorising goods in the first instance, and telling people precisely how to relate to them in the second.42 These past conceptualisations are crucial to understanding changes in the way recipes were written and how objects are described. In short, the descriptive terms used, and precision which emerged, do not necessarily tell us that cooks did not know what they were doing, but they do tell us that the writer, who was commonly the mistress of the house, was exhibiting greater authority and was more concerned with the cook’s methods and precise actions. Whether it was necessary or not, the mistress, who was strongly influenced by published models, increasingly felt the need to mediate the relationship between the cook, the food and the utensils involved in its preparation. In this sense, these manuscripts show us not only that food-related forms of material culture proliferated from the eighteenth century on, but also, and more importantly, that people were more aware of goods and how they should be used, and they articulated and formalised this increasingly.

* Author’s e-mail: madelineshanahan@gmail.com

doi: 10.3318/PRIAC.2015.115.04

1 For example, Paul A. Shackel, Personal discipline and material culture: an archaeology of Annapolis, Maryland, 1685–1870 (Knoxville, TN, 1993); Mark P. Leone, ‘Ceramics from Annapolis, Maryland: a measure of time routines and work discipline’, in Mark P. Leone and Parker B. Potter Jr (eds), Historical archaeologies of capitalism (New York, 1999), 195–216.

2 It should be noted that the term ‘recipe’ is anachronistic when discussing manuscripts produced at this time—they were, in fact, called ‘receipts’ during the period under review—but, for the sake of clarity, I adopt the contemporary term ‘recipe’. This decision is in line with other major scholarship in the field, namely Michelle DiMeo and Sara Pennell (eds), Reading and writing recipe books, 1550–1800 (Manchester, 2013). For a detailed discussion of the history of the genre in Ireland see Madeline Shanahan, ‘Dining on words: manuscript recipe books, culinary change and elite food culture in Ireland, 1660–1830’, Irish Architectural and Decorative Studies: The Journal of the Irish Georgian Society 15 (2012), 82–97; Madeline Shanahan, Manuscript recipe books as archaeological objects: text and food in the early modern world (Lanham, MD, 2015). For discussions of the genre in Britain and the United States of America, see DiMeo and Pennell, Reading and writing recipe books; Janet Theophano, Eat my words: reading women’s lives through the cookbooks they wrote (New York, 2002).

3 Shanahan, ‘Dining on words’, 84.

4 Shanahan, ‘Dining on words’, 89–91.

5 Theophano, Eat my words.

6 National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 14,786, Inchiquin Papers, A collection of domestic recipes and Medical prescriptions ‘started by Lady Frances Keightley about 1660’. Despite the later note attributing this to Lady Frances Keightley, it was more likely to have been started by her daughter, Catherine O’Brien, in the late seventeenth century.

7 Ivar C. McGrath, ‘Keightley, Thomas (c. 1650–1719)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford 2012 [2004]). Available online at: oxforddnb.com/view/article/15251 (last accessed 6 May 2012). For a more detailed recent discussion of these individuals see Gabrielle M. Ashford, ‘Advice to a daughter: Lady Frances Keightley to her daughter Catherine, September 1681’, Analecta Hibernica 43 (2012), 17–46.

8 Jane Ohlmeyer, Making Ireland English: the Irish aristocracy in the seventeenth century (New Haven, CT, and London, 2012), 169–210.

9 Stephen Mennell, All manners of food: eating and taste in England and in France from the Middle Ages to the present (Urbana and Chicago, IL, 1996), 83–101.

10 For publications relating to the ‘ideology of domesticity’ and the ‘separating spheres theory’ please see Carole Shammas, ‘The domestic environment in early modern England and America’, The Journal of Social History 14:1 (1980), 3–24; Diana. D. Wall, ‘Secular dinners and sacred teas: constructing domesticity in mid-19th century New York’, Historical Archaeology 25:4 (1991), 69–81; Amanda Vickery, ‘Golden age to separate spheres? A review of the categories and chronology of English women’s history’, The Historical Journal 36:2 (1993), 383–414; Matthew Johnson, The archaeology of capitalism (Oxford, 1996), 155–78; Michael McKeon, The secret history of domesticity: public, private and the division of knowledge (Baltimore, MD, 2005); Karen Harvey, ‘Barbarity in a teacup? Punch, domesticity and gender in the eighteenth century’, Journal of Design History 21:3 (2008), 205–21.

11 Gilly Lehmann, The British housewife: cookery books, cooking and society in eighteenth century Britain (Totnes, Devon, 2003), 66–71.

12 For an extensive discussion of this subject please see Shanahan, Manuscript recipe books as archaeological objects.

13 For a detailed discussion of the contents of Irish manuscript recipe books see Shanahan, ‘Dining on words’, 89–94; Shanahan, Manuscript recipe books as archaeological objects.

14 NLI, Ms 14,786, Inchiquin Papers, A collection of domestic recipes and medical prescriptions ‘started by Lady Frances Keightley about 1660’, mid- to late seventeenth century, 38.

15 For a further discussion of the influence of printed works on food culture in Ireland in this period see Alison Fitzgerald, ‘Tastes in high life: dining in the Dublin town house’, in Christine Casey (ed.), The eighteenth-century Dublin town house: form, function and finance (Dublin, 2010), 120–7.

16 NLI, Ms 19,729, Volume of cookery receipts, medical prescriptions and household hints compiled by Jane Burton [of Buncraggy, Co. Clare?], with index.

17 NLI, Ms 41,603/2 (2 of 2), Papers of the Smythe family of Barbavilla, Co. Westmeath, Box containing two recipe books and four folders of recipes, mid- to late seventeenth century, unpaginated.

18 See note 17 above.

19 The complex subject of French culinary influence in Britain and Ireland has been discussed in Fitzgerald, ‘Tastes in high life: dining in the Dublin town house’.

20 Carol Gold, Danish cookbooks (Seattle, WN, 2007), 11–12.

21 Shanahan, ‘Dining on words’, 94.

22 NLI, Ms 19,729, Volume of cookery receipts, medical prescriptions and household hints compiled by Jane Burton [of Buncraggy, Co. Clare?], with index, eighteenth century, 275.

23 Lorna Weatherill, Consumer behaviour & material culture in Britain 1660–1760 (2nd edition, London, 1988), 44, 155, 205.

24 NLI, Ms 14,786, Inchiquin Papers, A collection of domestic recipes and medical prescriptions ‘started by Lady Frances Keightley about 1660’, mid- to late seventeenth century; NLI, Ms 14,901, Miss (or Mrs) Barnewall, Collection of domestic recipes and medical prescriptions, late eighteenth to early nineteenth century; NLI, Ms 19,332, A book of recipes and medical remedies, also including some verses. [Compiled by a member of the family of Montgomery, of Convoy, Co. Donegal?], late seventeenth century; NLI, Ms 19,729, Volume of cookery receipts, medical prescriptions and household hints compiled by Jane Burton [of Buncraggy, Co. Clare?], with index, eighteenth century; NLI, Ms 34,110, Doneraile Papers, Notebooks with recipes and health remedies such as an ‘elixir for a long life’, accounts and household lists, July and August 1798; NLI, Ms 34,953, Cookery book, 1780–1820; NLI, Ms 34,932(1), Culinary and medical recipe books possibly compiled by member(s) of the Pope family of Co. Waterford, 1823; NLI, Ms 41,603/2 (1 of 2), Papers of the Smythe family of Barbavilla, Co. Westmeath, Box containing two recipe books and 4 folders of recipes, early eighteenth century; NLI, Ms 41,603/2 (2 of 2), Papers of the Smythe family of Barbavilla, Co. Westmeath, Box containing two recipe books and four folders of recipes, mid- to late seventeenth century; NLI, Ms 42,008, Ms cookery book belonging to Abigail Jackson, 10 April 1782.

25 Only one such list has been included here, but for alternative examples please see Shanahan, Manuscript recipe books as archaeological objects.

26 For more on the challenges and the potential uses of published recipe books for the study of material culture see Annie Gray, “‘A practical art”: an archaeological perspective on the use of recipe books’, in DiMeo and Pennell, Reading & writing recipe books, 47–67.

27 NLI, Ms 14,901, Miss (or Mrs) Barnewall, Collection of domestic recipes and medical prescriptions, late eighteenth to early nineteenth century, unpaginated.

28 Weatherill, Consumer behaviour & material culture, 44, 155, 205; Johnson, The archaeology of capitalism, 179–201.

29 Clare McCutcheon and Rosanne Meenan, ‘Pots on the hearth: domestic pottery in historic Ireland’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 111C (2011), 91–113: 105–06.

30 McCutcheon and Meenan, ‘Pots on the hearth: domestic pottery in historic Ireland’,

31 NLI, Ms 14,786, Inchiquin Papers, A collection of domestic recipes and medical prescriptions ‘started by Lady Frances Keightley about 1660’, mid- to late seventeenth century, 3.

32 NLI, Ms 14,901, Miss (or Mrs) Barnewall, Collection of domestic recipes and medical prescriptions, late eighteenth to early nineteenth century, unpaginated.

33 NLI, Ms 14,786, Inchiquin Papers, A collection of domestic recipes and medical prescriptions ‘started by Lady Frances Keightley about 1660’, mid- to late seventeenth century, 8.

34 Sara Pennell, ‘“Pots and pans history”: the material culture of the kitchen in early modern England’, Journal of Design History 11:3 (1998), 201–16: 209.

35 Johnson, The archaeology of capitalism, 179–202.

36 McCutcheon and Meenan, ‘Pots on the hearth: domestic pottery in historic Ireland’, 107.

37 Bríd Mahon, Land of milk and honey: the story of traditional Irish food and drink (Dublin, 1991), 8.

38 Weatherill, Consumer behaviour & material culture in Britain,38-41; Shackel, Personal discipline and material culture; Leone, ‘Ceramics from Annapolis’, 195–216.

39 Mary C. Beaudry, ‘Words for things: linguistic analysis of probate inventories’, in Mary C. Beaudry (ed.), Documentary archaeology in the New World (Cambridge, 1988), 43–50.

40 Lehmann, The British housewife, 156

41 Eileen White, ‘Domestic English cookery and cookery books, 1575–1675’, in Eileen White (ed.), The English cookery book: historical essays, Leeds Symposium on Food History: ‘Food and Society’ Series (Totnes, Devon, 2004), 72–97: 91.

42 Johnson, The archaeology of capitalism, 112.