The consumption and sociable use of alcohol in eighteenth-century Ireland

Department of History, St Patrick’s College, Dublin City University

[Accepted 28 April 2015. Published 19 June 2015.]

Abstract

A tabulation of the amount of duty-paid spirits, wine and beer produced in and imported into Ireland is the starting point for any engagement with the consumption and sociable use of alcohol in Ireland in the eighteenth century. Since a large volume of whiskey and beer, upon which duty was not paid, was also consumed, alcohol was inevitably a subject of much critical contemporary comment. Yet there is another perspective, which is more in keeping with the reality of a world in which alcohol was integral to domestic as well as public life. This paper engages with this subject in two parts. The first seeks, using official figures as its point of departure, to quantify the volume of duty-paid alcohol (specifically spirits, wine and beer) in circulation, and the pattern of illicit distillation. It also seeks to identify the retail structures that merchants, grocers and others evolved in order to meet public demand. The second part engages with consumption. A large proportion of the wine that was imported was consumed in a domestic setting. This was consistent with the view that, consumed in moderation, it was not only an aid to nutrition but also possessed of tangible medicinal benefits. In the public realm, alcohol was imbibed in the inns, taverns, alehouses and dram shops that were to be found in every part of the country. It was also integral to the commemorative, celebratory calendar of the Protestant elite and the popular calendar of the masses. However, it was alcohol’s augmented usefulness in the political realm from the 1750s, and its centrality to the rapidly expanding world of male sociability that enabled it to play a central role both as a social lubricant and as a means of forging political and organisational commitment during the remainder of the century.

Introduction

The volume and variety of forms in which alcohol was available are the most tangible evidence of the central place it occupied in Irish life in the eighteenth century. This has generally been portrayed in negative terms. Even before Fr Theobald Mathew embarked in the 1830s on his culturally defining temperance crusade, there was a strong current of commentary—religious, sociological, economic and political—that advanced or echoed the opinion that the patterns of alcohol consumption pursued in Ireland were socially deleterious.1 Its identification with poverty, violence and anti-social conduct ensured that alcohol was a compelling target for those who promulgated a vision of an improved and economically productive society populated by polite and mannered subjects. Encouraged by this vision, opinion formers at local as well as national level advocated intervention as a means of regulating consumption, and if parliament and the Revenue tended for fiscal reasons to be more reticent, municipal officers, MPs and peers were increasingly disposed from the 1770s to give statutory expression to the contention that regulation would ameliorate the heavy consumption of spirits by the ‘lower classes’.2 The consumption patterns of the elite did not pass unnoticed either as commentators as diverse as Samuel Madden (Fig. 1), George Berkeley and William Henry drew on traditional religious values, the virtues of improvement and the culture of politeness in order to elaborate a powerful condemnation of the patterns of alcohol consumption that were normative in Irish life. However, there is another perspective, which has been overlooked amidst the tsunami of criticism that prevailed in the public sphere. Implicit in the actions of the many who raised a glass either to the ‘Glorious Memory’ or to ‘The Pretender’, of those who participated in political gatherings in which toasting was de rigeur, and of those who raised a glass on the still more numerous occasions in which people dined in company was an acknowledgement that alcohol was integral to the forms of sociability and the patterns of association that shaped and defined how people interacted in the eighteenth century. This was certainly facilitated by the gustatory, social and mood-altering pleasures it afforded, but it was not the only consideration. Alcohol was a standard accompaniment with meals; while people of all ages and rank, persuaded of its therapeutic value, ingested it as a medicine.

Availability of alcohol: volume and varieties

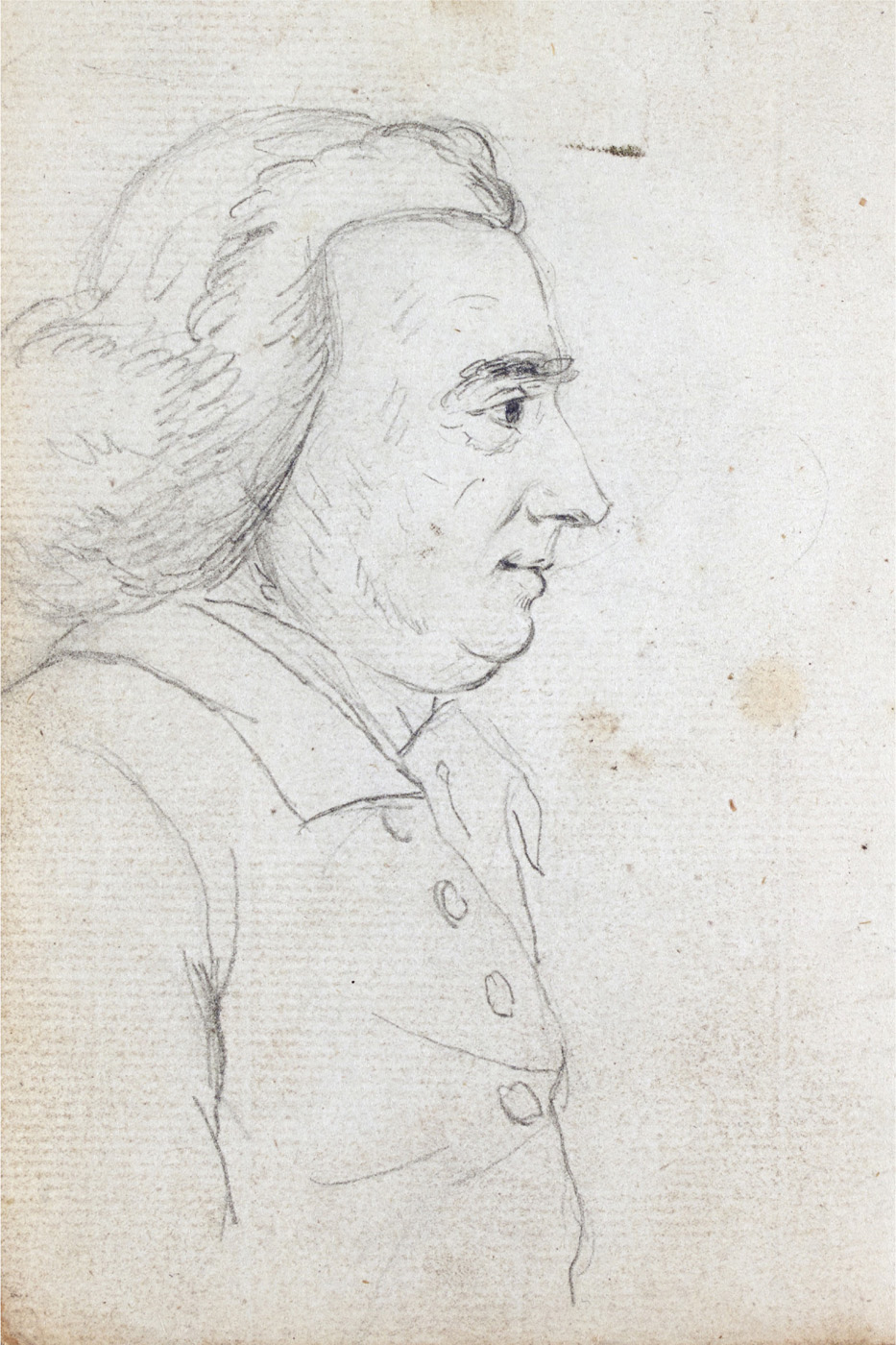

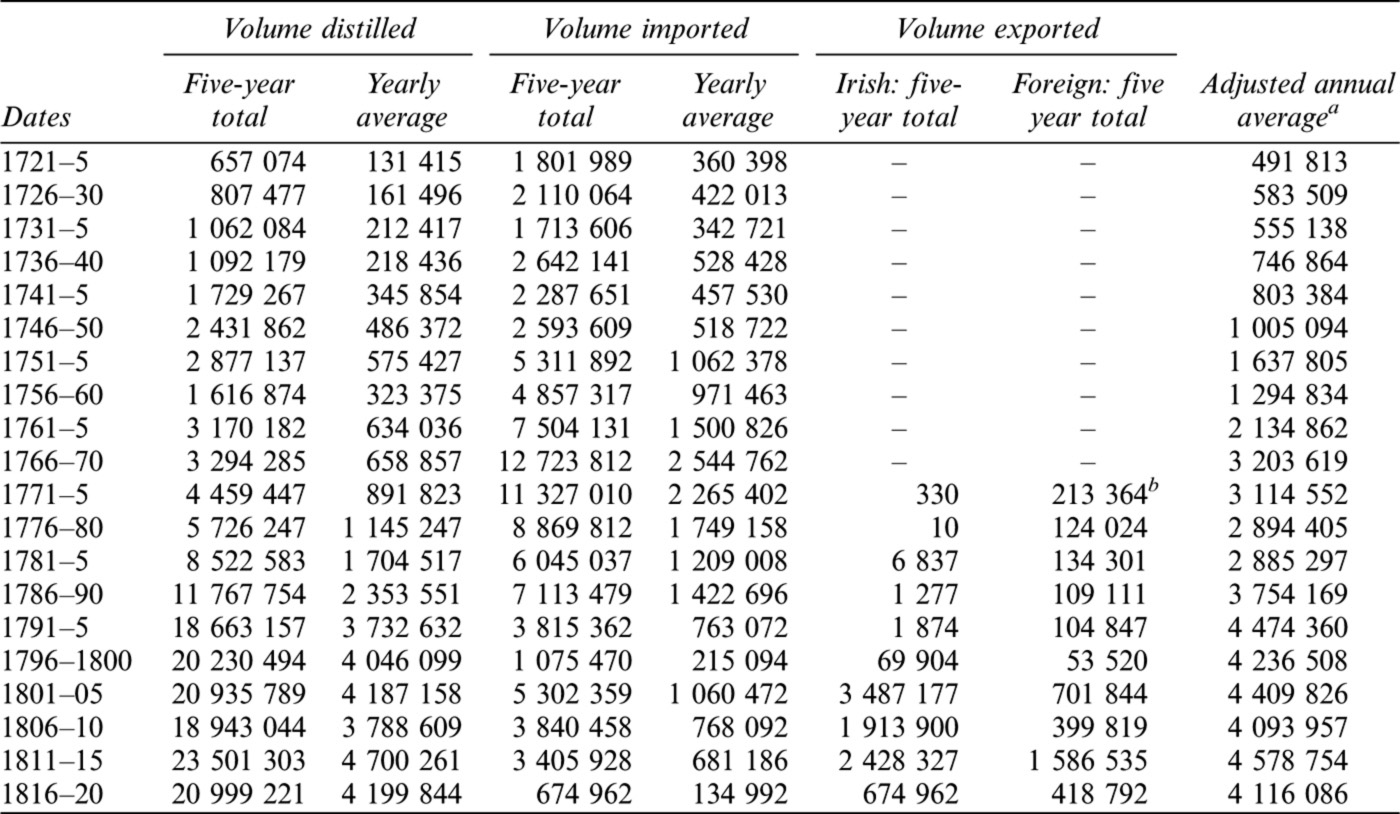

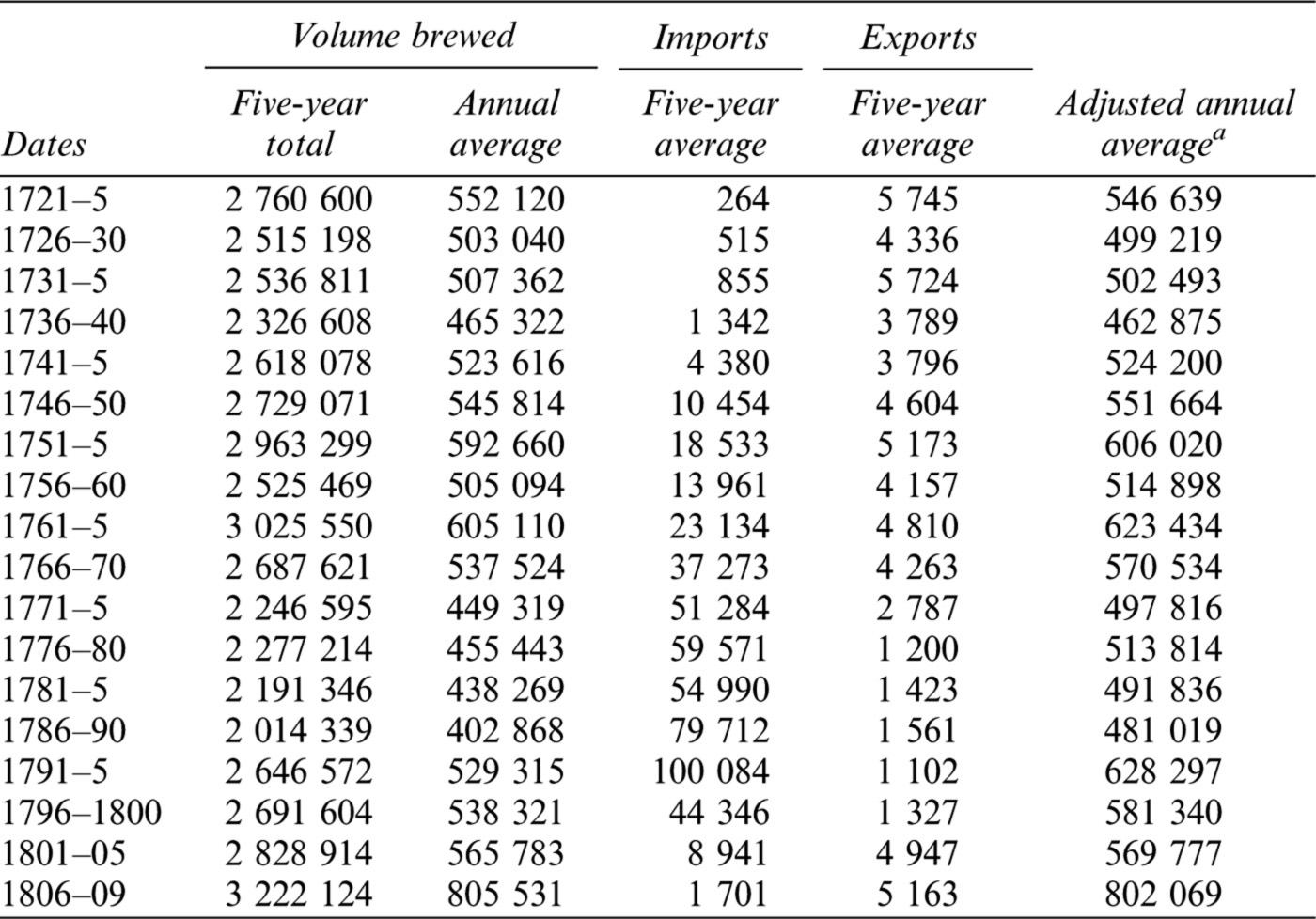

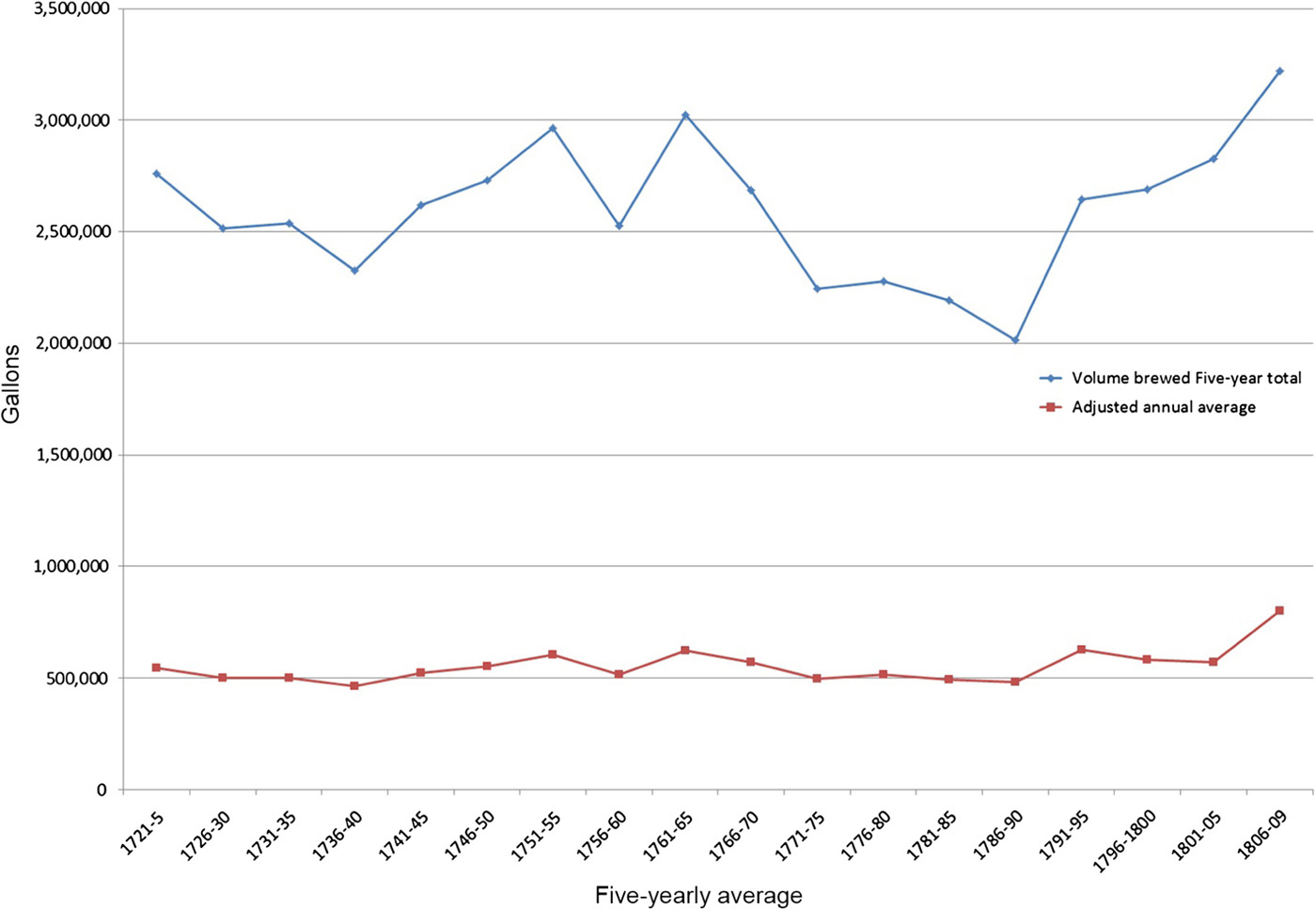

The import and export figures assembled by Samuel Morewood are a useful starting point to any attempt to establish the order of alcohol consumption in eighteenth-century Ireland.3 Taking 1720—the second year of Morewood’s series—as a starting point and spirits as the focus, duty was paid on 463,157 gallons of spirits, 30% (136,075 gallons) of which was domestically distilled and 70% (327,082 gallons) of which was imported.4 A majority of the duty-paid spirit traded, and consumed, in Ireland was of foreign origin until the late 1770s when the combination of a decline in the availability of foreign produce and a surge in whiskey production signalled the commencement of a phase that was to long endure, when Irish-produced whiskey predominated (see Table 1 and Fig. 2). Unsurprisingly, the primary stimulus of this growth was domestic demand. During the 1720s, 1730s and 1740s the volume of duty paid on domestically produced and imported spirits both sustained an unspectacular upwards trajectory. The five-year averages presented in Table 15 suggest that the volume of duty-paid spirits rose from just below half a million gallons per annum in the early 1720s to a million gallons in the late 1740s. This increase mirrored broader improvements in the economy,6 and it is notable that, as well as a significant increase in domestic production, the ‘strong upsurge’ in economic activity that occurred in the second half of the 1740s sustained the surge in spirit imports, already a decade old, which peaked in the second half of the 1760s when the annual average volume of imported spirits exceeded 2.5 million gallons. The level of demand remained vigorous for several decades thereafter though the trajectory was now downwards, as it coincided with record levels of domestic production, which had embarked on a phase of rapid growth in the 1760s. At nearly 4.5 million gallons, domestic spirit production during the five years of 1771–5 accounted for 28% of the total volume of spirits (15.78 million gallons) upon which duty was paid. A decade later, fuelled by a fall in imports and by the Revenue Commissioners’ realisation that it was more efficient (from a revenue-raising perspective) to concentrate production in a smaller number of large capacity stills, domestically produced duty-paid spirits exceeded imports.7 During the quinquennium of 1781–5 more than half (58.5%) of the spirits upon which duty was paid (14.568 million gallons) was home produced, and this trend was sustained. In the late 1790s an imposing 95% of the spirits upon which duty was paid was domestically produced. The volume of spirits imported recovered somewhat in the first decade of the nineteenth century but it was insufficient to alter the balance, as domestic production now comfortably exceeded importation (Table 1; Fig. 2).

FIG. 1—Portrait of Reverend Samuel Madden, by James Brocas, c. 1754–80. Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Ireland.

TABLE 1—Irish alcohol, 1721–1820: spirits (in gallons)—official figures (per quinquennium).

Source: Samuel Morewood, A philosophical and statistical history of the inventions and customs of ancient and modern nations in the manufacture and use of inebriating liquors (Dublin, 1838), 726–7.

a This figure has been generated by adding the average of the totals of domestically distilled and imported spirits, minus, where the figures are available, the volume of exported spirits.

b Export figures are only available from 1772.

FIG. 2—Ireland’s alcohol consumption, 1721–1820: duty-paid spirits (gallons).

Because a proportion (usually small but as high as 46% in 1811–15) of imported foreign spirits was re-exported (see Table 1), the underlying increase in the consumption of duty-paid spirits was less striking than the gross figures suggest, but annual consumption more than doubled, from c. 2.1 to c. 4.5 million gallons, between the late 1760s and the early 1790s (Table 1). This was not the full story, however. The efficiency with which the revenue service enforced the regulations favouring bigger stills and, by decreeing, first (1732), that licenced producers must be located proximate to, and subsequently (1758) within ‘market towns’, created an environment in which illicit distillation flourished.8 It has been conjectured that drunkenness and illicit distillation emerged as a problem together in the second half of the eighteenth century,9 but, if so, reports from the middle decades of the century to the Revenue Commissioners indicate that illicit production was already entrenched. The account conveyed in 1748 by an officer located in the Sligo district of ‘some distillers who carry on a clandestine trade . . . removing their stills to the mountains’ demonstrates that the cat and mouse game in which they were long joined was already under way, but since there were ‘upwards of 150 private stills’ in that district at that time, and the seizure of ‘unstatutable’ stills was commonplace, it can be concluded that (‘illicit’) whiskey was readily available.10 This is not to suggest that the 1758 act, and the energy with which it was applied, did not push many distillers into illegality, but it served to intensify a trend that was already in being and not to inaugurate a new one.11 The report of William Parsons, who had charge of the Augher revenue walk in mid-Ulster in 1759, that whiskey was ‘the liquor mostly used there, [and] with which the people are supplyed in great abundance by sixteen stills, or more, which work in the glinns of the mountain between Augher and Fivemiletown’ (both in County Tyrone) is another pointer to its pervasiveness. Parsons could identify, based on visible smoke trails, the proximate locations of these stills, but he was unable to get close ‘enough to make a full discovery’ because he was prevented from doing so by the ‘people in arms’.12 Others officers had comparable experiences, for though the application of the law progressively reduced the number of enterprises producing spirits legally,13 demand was sufficient to sustain a vigorous pattern of illicit distilling in rural and in increasingly remote locations.14

Clandestine distilling probably accounted for the bulk of the ‘illicit’ whiskey produced in rural Ireland, but one did not have to be unlicensed in order to produce whiskey upon which duty was not paid. The testimony of the distillers, who gave evidence to a parliamentary inquiry in 1805, that they declared only half their production, not only implies that illicit production was then island-wide, but also that its volume may have equalled that of its ‘legal’ equivalent.15 In any event, the conclusion based upon official figures that ‘Irish spirit consumption in 1790 was made up of 66% whiskey, 26% rum, 6% brandy and 1% gin’ is built on insecure foundations. Yet, it does offer some statistical support for claims that increased whiskey production fuelled the surge in spirit consumption that was then taking place. The fact that the respective figures for duty-paid spirits in 1770 were 51% rum, 25% whiskey, 14% brandy and 10% gin is revealing of its impact on consumption patterns.16

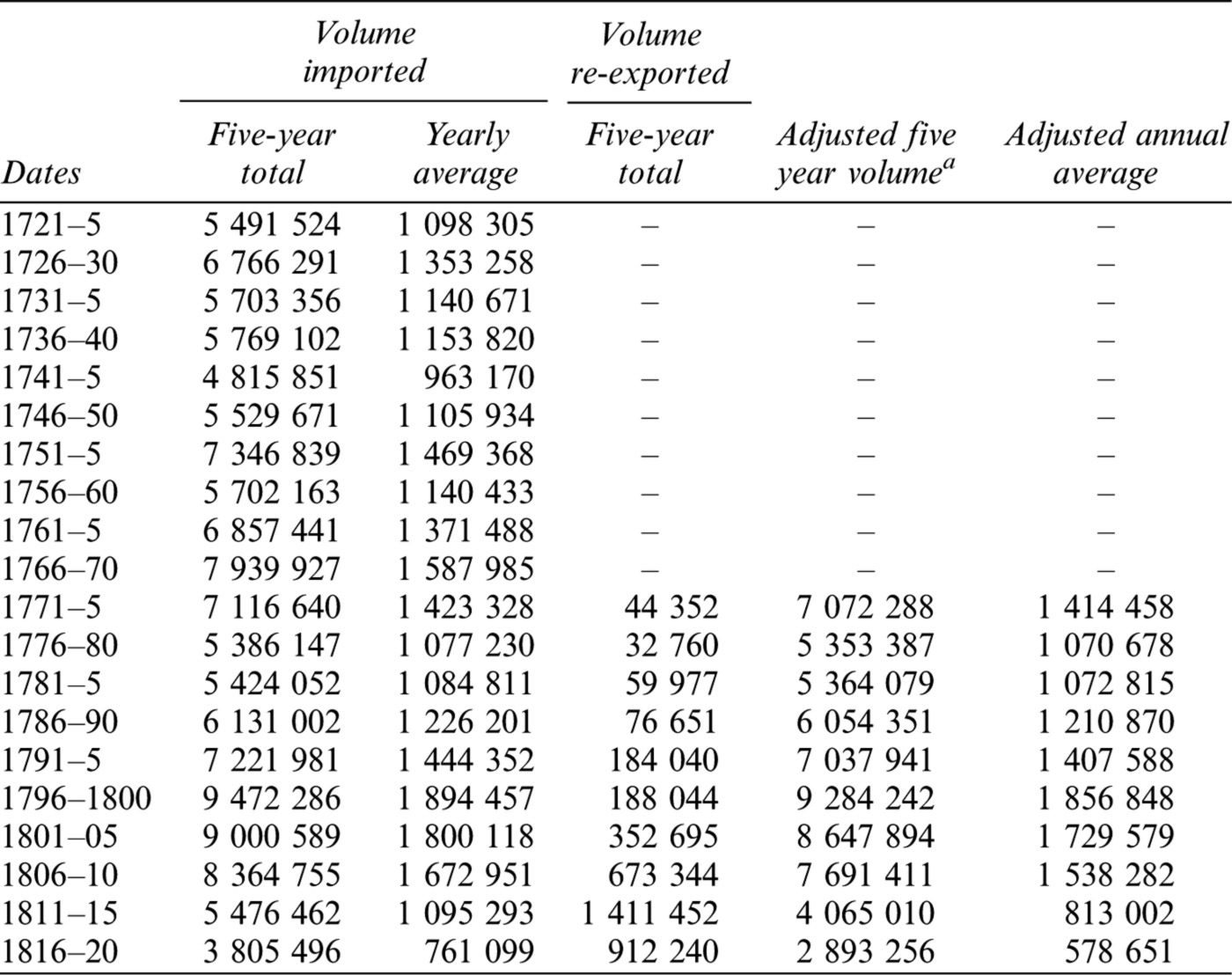

From the perspective of the sundry moralists, divines, improvers and concerned commentators troubled by these trends, it would have been beneficial if the population replaced whiskey with beer, ale or porter. Each possessed champions, but the pursuit of private and unlicensed brewers by the Revenue and the disadvantageous regulatory environment that had existed since the beginning of the century had taken a heavy toll. As a result, the volume of beer brewed domestically per quinquennium only once exceeded three million barrels in the course of the eighteenth century.17 The fact that annual production barely exceeded 400,000 barrels per annum in the 1780s (when spirits production surged) indicates that it possessed only modest appeal for the mass of the population which drove the increased demand for Irish whiskey, or for those with more refined palates who accounted for the bulk of the foreign spirits and wines that were consumed. Nor did the enhanced availability of better-quality English imports, which were heavily advertised in the press in the final quarter of the century,18 alter the picture much. The volume of imported English ales, beers and porter remained modest, exceeding 50,000 barrels per quinquennium for the first time in the early 1770s, and 100,000 barrels for the first time in the early 1790s (Table 2; Fig. 3). Since beer travelled badly, it is tempting to assume that large households and institutions brewed for their own use. Some did, but the observation by a well-informed visitor in 1792 that ‘the brewing regulations make it so difficult . . . that even in great families it is rarely attempted’ suggests otherwise.19 Moreover, the fact that consumption remained at or about half a million barrels annually between the mid-1760s and late 1780s, when the constant endorsement of the virtues of brewed alcohol over spirits registered a (modest) improvement (Table 2; Fig. 3), indicates that demand was largely static.

TABLE 2—Irish alcohol, 1721–1820: beer and ale (in barrels)—official figures (per quinquennium).

Source: Samuel Morewood, A philosophical and statistical history ofthe inventions and customs of ancient and modern nations in the manufacture and use of inebriating liquors (Dublin, 1838), 726–7. a This column is calculated by adding imports to, and subtracting exports from, the five-year average.

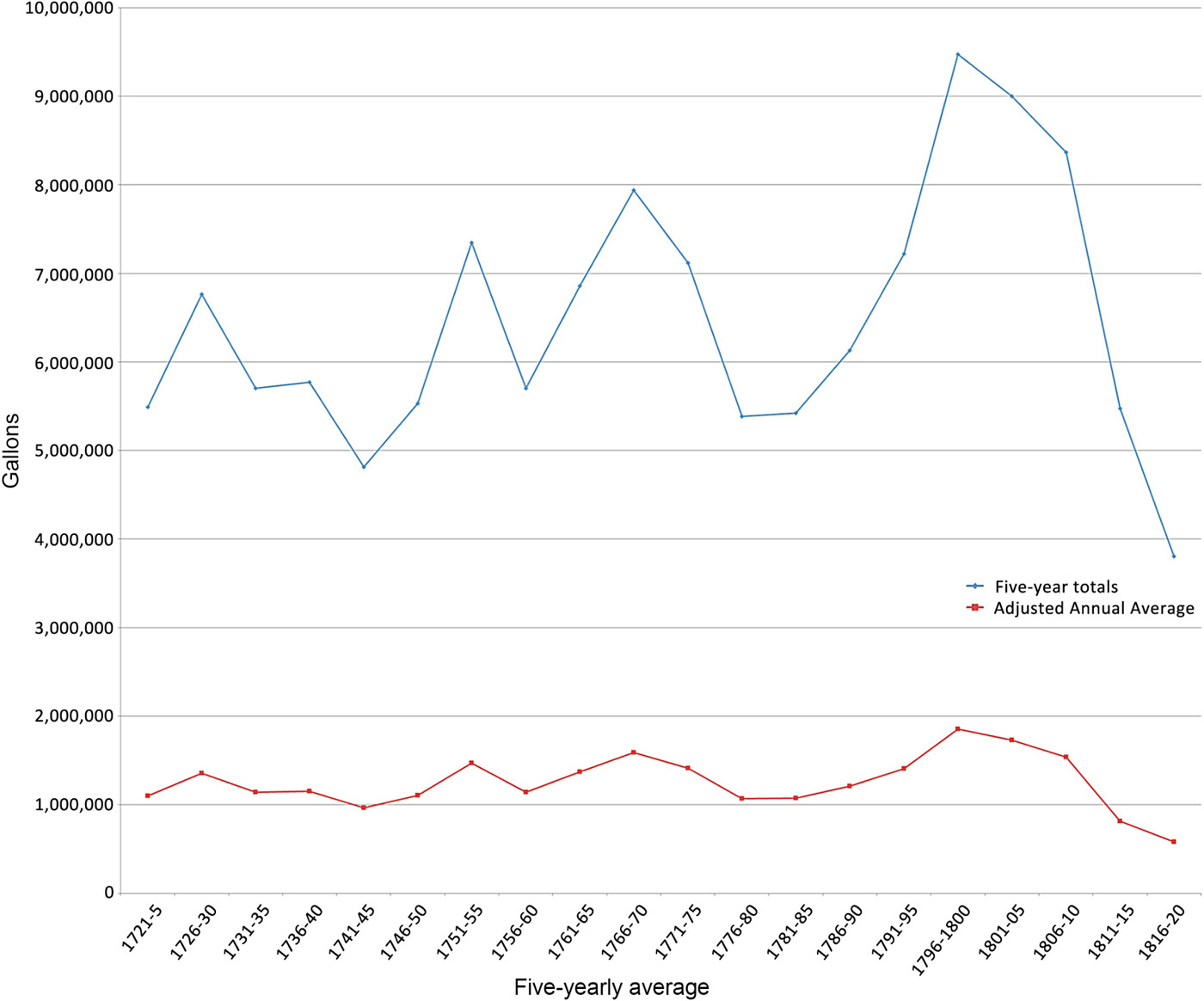

The pattern of wine consumption was comparable, though it was held in much higher esteem because it was the alcohol of choice of the gentry and aristocracy. In contrast to their English peers, Irish wine drinkers favoured French over Portuguese and Spanish wine, and claret over port.20 Anglo-French rivalry meant that the volume of wine imported fluctuated, but the import figures (Table 3; Fig. 4) suggest that the Irish market required between 1 and 1.5 million gallons per annum until the 1790s when imports, and re-exports, reached record levels, and the strong preference hitherto shown for French wines altered.21 Wine was also smuggled, of course. Louis Cullen has properly cautioned against assuming that it was a major part of the contraband trade, on the grounds that ‘bulky’ hogsheads filled with wine were unsuited to surreptitious trading, but this did not discourage all movement of this kind. Wine was certainly a less attractive option for smugglers than brandy, as the seizures reported by Revenue officials attest,22 but there was a market for those who took the chance, and evidence from the south-west suggests that enough individuals did so to permit the conclusion that some landed families were regularly supplied with quality French wine by this means, until targeted interventions by the Revenue upset this traffic.23 It is likely also that innkeepers and allied retailers, who cultivated the custom and patronage of members of the gentry and middling sort, were also beneficiaries of wine-smuggling, if the recollection of John O’Keeffe (1747–1833), the dramatist, that ‘good claret . . . was to be had at every thatched ale-house all over the kingdom’ possesses even a passing acquaintance with reality.24

FIG. 3—Ireland’s alcohol consumption, 1721–1820: beer (gallons).

TABLE 3—Irish alcohol, 1721–1820: Wine (in gallons)—Official figures (per quinquennium)

Source: Samuel Morewood, A philosophical and statistical history of the inventions and customs of ancient and modern nations in the manufacture and use of inebriating liquors (Dublin, 1838), 726–7. a Calculated by subtracting re-exports from the five-year totals.

FIG. 4—Ireland’s alcohol consumption, 1721–1820: wine imports (gallons).

While the trade in and production of alcohol provide a framework within which the consumption and sociable use of alcohol can be placed, it is necessary to move beyond the figures in order to identify patterns of consumption. This is less than entirely straightforward for though one may locate pertinent contemporary observations, such as those offered by Charles Abbot, the future chief secretary who visited Ireland in 1792, that ‘whiskey is the constant drink . . . [of] the lower class’ in support of this conclusion, whiskey drinking was not exclusive to individuals of this rank.25 A comparable reservation may be entered with respect to Elizabeth Malcolm’s imaginative attempt to calculate per capita wine consumption at the end of the Napoleonic era. Based on the assumption that the number of wine consumers mirrored that of the ‘number of borough and county electors’—220,000, or c. 3.2% of the population—Malcolm proposes ‘a per capita consumption of five gallons per annum at the very least’, which she concludes was ‘substantial’. This seems reasonable by modern standards, but it is well in excess of L. A. Clarkson and E. Margaret Crawford’s calculation that the pattern of wine consumption among the elite followed an upwards graph from 14 pints per person per annum in 1700 to 24 pints in 1750 only to fall back to 13 pints by 1800.26 The truth is we are insufficiently informed of the patterns and habits of consumption to sustain much more than general conclusions as to who consumed what. Moreover, conclusions based upon the volumes presented in Tables 1–3 to the effect that consumption was at a (damagingly) high level across Irish society may well be wide of the mark if, as can be argued, consumption was not only less strictly socially determined than it is generally assumed, but was also more fully integrated into the prevailing patterns and habits of dining, recreation and social congregation.

It is possible, using the advertisements placed in the press by auctioneers, merchants and retailers to paint a fuller picture of the range and varieties of alcohol offered for sale, and to show that the patterns of consumption were less firmly socially defined than observers such as Abbot aver. Focusing in the first instance on the marketing of alcohol in early eighteenth-century Dublin, one could in 1711–12 purchase white or red wine (Lisbon white, Barrabar white and Graves claret) by the dozen bottles or by hogshead, and brandy by the gallon from the house of William Hutchinson, a merchant based on Blind Quay.27 The advertised range available at The Sign of the Ton on Lower Essex Street was larger (‘good white’, claret, canary, mum, Barcelona wine and brandy), but since it sold primarily by the quart or gallon it evidently functioned as a tavern as well as a retail outlet.28 This was not unusual. Nearly two decades later one might purchase ‘good Graves claret’, ‘good Margoes [Margeaux]’, ‘good Canary’ and ‘good sherry’ either by the quart, gallon or in larger volumes at a discount at The Mighty Tun in Smithfield.29 However, in a more revealing development, echoing that pioneered by the purveyors of patent and proprietary medicine and emulated by the promoters of horse racing, the retailers of alcohol increasingly had recourse to the press as a medium through which to inform the middling sort as well as the elite of the expanding selection of wines and spirits that could be purchased in denominations ranging from a gallon to a pipe.30 Once this had begun, it was destined to expand, and 40 years later the retail sector was sufficiently developed to sustain outlets catering for an ever larger portion of society.

The most notable pointer of the extent to which alcohol became a staple commodity for middle- as well as upper-class households in the eighteenth century is provided by the emergence of retailers like Bensons and Hamilton of Cork, where in 1773 one could purchase coffee as well as madeira wine in ‘convenient’ quantities for ‘home consumption’, and Dillon (subsequently Duffey) of 43 Castle Street, Dublin, who in the 1790s targeted ‘housekeepers’ as the most likely consumers of a variety of ‘teas, sugars, wines and spirits’, the most notable of which was his ‘family whiskey’—a ‘rectified old spirit whiskey, engaged to bear 7 waters’.31 Even regular alcohol retailers got in on the act. The Bordeaux Warehouse, which was based on Werburgh Street, Dublin, advertised its blend of ‘old spirits of whiskey’ as suitable ‘for private families use’.32 A still more compelling insight is provided into the centrality of alcohol in the diet and lifestyle of the households of the ‘middling sort’ as well as the elite by the presence of alcohol among the stock in trade of grocery outlets. Thus in Cork city, Cornelius Murphy stocked old rum, brandy, Geneva and whiskey alongside ‘sugars and teas of all kinds, coffee, raw and ground’, and a wide variety of other commodities in his ‘grocery business’ on Mallow Lane in 1780.33 John Phelan of Bridge Street, Dublin, maintained a still more extensive selection of teas (seven types), coffees (five) and sugars (eleven) alongside an impressive inventory of wines and spirits; so too did John Leech and John Lee at their premises on Abbey Street, also in Dublin, but the intimacy of the link that had grown between grocery and alcohol is best exemplified by the ‘tea, wine, spirit, and grocery warehouse’ maintained by Andrew Carr at 71 Dame Street in Dublin where various wines and porters could be purchased in standard quantities of a dozen bottles and spirits by the gallon.34

There were, of course, still more dedicated alcohol retailers, catering primarily for the elite, who contrived to broaden their customer base. The most striking feature of the enterprise operated by Charles Carrothers at 6 Lower Jervis Street, Dublin, through the 1770s and 1780s was his attentiveness to price and quality. Able, because he sold for ‘ready money’ only, to undersell retailers who accepted credit, he maintained an extensive stock of ‘superior quality’ as well as ‘choice’ wines, amounting in 1779 to ‘1,000 to 1,500 hogsheads in wood and bottle’, which meant he was in a position ‘to supply the wholesale buyer as well as the retailer or customer on the very best terms’. It was a formula that worked since his outlet was, with John Wilson’s ‘vaults’ on Grafton Street, one of two major houses in the city in the late 1780s that advertised the availability of ‘first growth’ (premier cru) wines of the houses of Lafitte, Latour, Chateau Margeaux and Hautbrion; and it is a measure of Carrothers’ success that he ‘entered into partnership’ in 1789 with William Boyd, whose long established house included Dublin Castle among its clients.35

Boyd and Carrothers were not the only upper-end wine merchants operating in Dublin in the late 1780s, but equivalent claims were made with less justification by others.36 It was then commonplace to assert that one stocked wines, port and, increasingly London porter, of ‘superior’ or ‘best’ quality, since this was the practice in this competitive sector. Indicatively, the advantage that Charles Carrothers accrued by prioritising ‘ready money’ customers spawned imitators. Thomas Conroy, who sold wines from his premises on Capel Street through the 1770s and 1780s, emblazoned his advertisement with the slogan ‘wines for ready money only’, but since he stocked madeira, hock, sherry, claret, port (red and white), mountain, carcavella and other grape varieties ‘in pipes, hogsheads, quarter casks and bottles’ in the 1790s, it was evidently a successful formula.37 It certainly helped if the retailer was seen to be responsive to his customer’s needs. Conroy’s promise that he would supply fourteen bottles for every dozen purchased, and John Wilson’s offer to those ‘who buy wines in wood, and choose to have it bottled in his vaults’ that they would ‘be accommodated with clean new bottles at glass-house price’ was a well-judged scheme to capitalise on the fact that many householders found the task of bottling wine disagreeable. Promises that wine would be made available in bottles of a standard size, incentives to encourage the purchase, circulation and return of empties, and the availability for purchase of wine labels indicate that those offering ‘choice claret’ by the hogshead and fine ‘old port’ by the pipe, hogshead and quarter cask did so in the expectation of making sales.38 Moreover, it was not only high-quality wines, and upper-end retailers, that employed such practices in order to ensure that bulk purchasing (in pipes, hogsheads and quarter casks) continued in the face of the increased availability of bottled wine, which was generally sold in units of a dozen bottles.39 There was certainly enough variety from which to choose. For example, if in the late 1780s one entered the ‘vaults’ of John Wilson, as well as the claret, port and white wines that were his stock in trade, one could purchase ‘claret, burgundy and champagne of the first growths of France, old sherry, Lisbon, carcavella, hock, madeira, frontiniac [sic], vin de Grave, white port, Malaga etc equally cheap’, and ‘best London porter and sweet sparkling English cider in wood and bottle’.40 Indeed, the demand for wine was perceived as sufficiently robust to justify the establishment, in the 1790s, of a Bordeaux Warehouse on Werburgh Street, and of Birney’s Portugal Warehouse on South Great George’s Street, though this was evidently a step too far as neither enterprise flourished.41

Apart from those at the higher end, few retailers focused exclusively on wine. Most small and medium-sized retailers stocked popular wines as well as spirits (arrack, rum, rum shrub, whiskey of all types, brandy and Geneva) and, increasingly, English beers, ales and porters, and Irish and English cider consistent with their broader customer base.42 Interestingly, the mounting appeal of porter prompted Birney to rename his flagging Portugal Warehouse the ‘London Porter Stores’ in 1791, but it did not prove any more successful, and after a short-lived reversion to the Portugal Warehouse, the outlet was known simply as ‘Birney’s stores’ in 1794.43 Subsequently, John Wilson rebranded his premises as ‘Wilson’s wholesale wine vaults and London Porter Stores’ but it too seems not to have fulfilled its proprietor’s expectations.44 It seems as if the customer base that these retailers appealed to was not sufficiently wealthy to justify this degree of specialisation.

Though the cultivation by wine merchants such as Charles Carrothers of clients outside Dublin, and the discounts that Dublin-based retailers were prepared to offer, was a factor in accounting for the dominance of the capital in the retail of fine wines in eighteenth-century Ireland, an impressive range of imported alcohol could be purchased in most of the country’s larger towns. A survey of the advertisements in Finn’s Leinster Journal for the late 1760s suggests that the citizenry of Waterford and Carlow had comparable access to Continental wines and West Indian spirits, if not the same choice of outlets in which to make their purchases.45 This is true also of Clonmel, which was largely supplied through Waterford. The availability at Michael Luther’s store in Clonmel in March 1792 of 150 tierces of the ‘best London porter’, of ‘first quality’ claret, red and white wine, sherry, and red and white port in ‘pipes, hogsheads and quarter casks’ and ‘in prime order in wood and bottle’ provides an indication of the range that he, John O’Keeffe, who operated out of Limerick, and James Sexton, who was based in Ennis, Co. Clare, offered customers.46 This is not to imply that the quality of the wine available regionally was ordinary, though it is noteworthy that those who engaged in the retail of wine and foreign spirits (Spanish and French brandy, Holland geneva and Jamaica rum) in such locations were more likely to do so as part of a combined ‘grocery, wine and spirit business’, to target the custom of ‘housekeepers’, and to ‘sell upon the most reasonable terms’.47 Indicatively, James O’Brien of Limerick, advertised in September 1795 that he could supply ‘his friends and the public with [claret] the most capital growth of the years ’86, ’88, ’90 and ’91’, pipes or hogsheads of vintage red port, and ‘a good supply of madeira, frontignaca [sic], barsac, vin de Grave, sherry, Lisbon and Mountain’.48

As the second city on the island, and an international port that routinely admitted ships from France and Portugal bearing brandy and wine, and from the West Indies carrying rum, the variety of alcohol available for purchase in Cork bore closer comparison to Dublin than any other regional hub.49 The main identifiable differences between it and the capital was the greater range of rum that was available (Jamaica, Antigua, Barbados, Granada and St Kitts), and the more frequent opportunities to purchase alcohol at auction.50 It is reasonable to assume that a majority of those who purchased brandy, wine, rum (perhaps even porter) by the pipe, puncheon, and hogshead (quarter cask) at auction were retailers. Yet, the fact that Hugh Jameson and Sons, of Morrison’s Island, who imported wine in significant volumes from France and Portugal for auction, also advertised the sale of ‘red and white port wine’, Malaga wine, sherry and Cognac brandy by the pipe and hogshead from their cellars, and that others merchants did likewise indicates that the wholesale and retail markets overlapped.51 The decision of Stephen and Martin Auster, who maintained a wholesale ‘grocery, spirit and wine warehouse’ on Mallow Lane, to auction 500 dozen bottles of different wines in 1785 is consistent with this, though Dennis Sullivan, Main Street, a ‘grocery, wine and spirituous liquor seller’, was more representative of this type; he sold a more limited range of wines, brandy and rum alongside sugar, tea, spices and other staples.52 It is not possible without further inquiry to establish the relative proportions of those who engaged in this dual trade, and those who concentrated on the sale of alcohol, but the impression provided by the local press is that the latter exceeded the former. The closest late eighteenth-century Cork came to the high-end wine specialists to be found in Dublin was the house of Boyd and Maziere whose ‘extensive wine cellars’ opposite the Custom House were modelled on ‘the much approved plan of. . . houses in London and Dublin’. In practice, both they, Samuel Cooper and Co. of Cook Street, and Robert and J. Nettles of George’s Street replicated the sales model (in offering discounts and requiring ‘ready payment’) rather than the inventory of the London and Dublin houses they claimed to emulate, but they did promise those who sought good wine that they could secure the same at ‘cheap’ prices in units of a dozen bottles.53

For those who sought to secure large quantities, there was plenty of opportunity to buy wine and spirits in traditional wood. The flimsy evidential footprint that remains of most of the enterprises that sold wine in bulk in Cork suggests that they operated as general merchants, who moved in and out of the alcohol trade.54 They also presumably targeted different clients than the retailer. The delightfully named Sober Kent sought out ‘private families’; he announced in 1770 that he had ‘choice claret, rich old sack, Lisbon, frontiniac [sic], French white wines, red and white port, genuine Jamaica and Antigua rum, Cognac brandy and choice French cherry brandy’ in stock ‘at his cellars on the Coal Quay’. Others simply advertised that they had wine for sale and awaited customers.55 It remains to be established which strategy was most effective, but it is reasonable to conclude that the diversity of retailers identifiable in Cork and Dublin would not have existed if the market was not growing; the surge in advertisements in the final decades of the century announcing the availability of London porter (specifically Whitbred’s and Thrale’s), Taunton beer (in tierces), spruce beer and Irish cider (in hogsheads), and of locations where they might be purchased is consistent with this. It also cautions against fixedly correlating types of alcohol and social class.56 This point may be made also in respect of the marketing and consumption of spirits.

The most persuasive evidence that money could be made retailing spirits to those with above average purchasing power is provided by its availability in a variety of outlets. Much of the whiskey consumed by the ‘common people’ may well have been procured in the ‘whiskey shops’ that were decried so passionately in the public sphere, but one cannot conclude from this that whiskey was only consumed by those at this social level.57 Such outlets, and the multiplicity of licensed and unlicensed ‘dram shops’, were integral to the supply of whiskey, illicit or duty paid, to the populace, and thus to the commercial infrastructure that traded in this commodity; but distillers and others also engaged actively in refining and modifying spirits to suit a broader palate that embraced the elite. There is no information on the proportion of spirits that was consumed in a diluted or softened form. However, the plenitude of retailers who advertised raspberry and cherry brandy, orange and raspberry rum shrub, pineapple rum, blackcurrant Geneva, and raspberry and blackcurrant whiskey is illustrative of the popularity of these varieties, and of the fact that a proportion of each of the main spirits was consumed in a sweetened or diluted form.58 This encouraged specialisation by a number of regular and ‘compound’ distillers in the preparation of ‘distilled liquors and cordials’. Some of these ‘cordial drams’—notably aniseed, wormwood and tansy waters—served a primarily medicinal purpose, though whether that was the focus of the distillery operated by Catherine Higgins at Southgate, Cork, whose output in 1770 embraced ‘raspberry brandy, whiskey shrub, aniseed water, wormwood water, hot surfeit water, [and] usquebaugh’, is unclear.59 Usquebaugh was the most famous Irish cordial. Flatteringly described as ‘the richest cordial in Europe’ in the early eighteenth century, it was perceived to have dis-improved by the 1740s when it was described as ‘not so good as it used to be’. Be that as it may, Drogheda usquebaugh was held in sufficiently high esteem for Katherine Conolly, the chatelaine of Castletown, Co. Kildare, to convey it to her sister in England when she was indisposed, and for John, Baron Wainwright, a judge in the Court of Exchequer, to send it to Charles, second duke of Grafton, who had served for a time as lord lieutenant of Ireland.60 Moreover, though it lost some of its lustre thereafter, it continued to be manufactured and sold, and to evade the criticisms increasingly targeted at punch.61

A combination of whiskey, water and sugar, whiskey punch had arrived at such a point of popularity by the 1790s (it was claimed that ‘three fourths of the spirits drank in Ireland are consumed in the form of punch’) it was condemned as ‘pernicious’. This was alarmist, but the popularity of punch, grog (which combined rum and water) and concoctions composed of spirits and fruit served not only to increase the appeal of spirits across social and gender boundaries but also to normalise their usage.62 The perception of high-end tavern and innkeepers that they required ‘the best assortment of all kinds of wines and good liquors’ also contributed to the process of normalisation by introducing particular varieties to new consumers. Though the alcohol that was available spoke volumes about the clientele that an inn aspired to attract, the fact that they retailed spirits as well as wines increased the likelihood of their being consumed by a broad social catchment. This was true also of the kingdom’s first dining houses which boasted that their ‘wines [we]re of the best description’ and their port was ideal for ‘single gentlemen’.63

This is not to deny the validity of the generalisation that wine was the preferred drink of the elite, and whiskey the preference of the masses. It is rather to suggest that since alcohol was readily available, and society manifested no inclination to embrace temperance, it was not only permitted but also facilitated admission to a prominent place in private as well as public life among all social classes. The negative implications of this, which the appreciating number of critics of alcohol (and particularly whiskey) insistently evoked, included increasing drunkenness, alcohol-fuelled violence and lost productivity, but it also possessed tangible benefits, which contributed in an important way to the well-being of the population at large.

Consuming alcohol

Despite its bounteous availability, and its centrality to life and lifestyle, alcohol consumption was regarded with mounting suspicion by commentators and politicians in eighteenth-century Ireland. Opposition to spirituous liquors’, specifically whiskey, which the speaker of the House of Commons (John Foster) condemned in memorable terms in 1789 as the demolisher of industry, morals and subordination’,64 increased exponentially in the 1780s and 1790s, and informed the attempts by the legislature in the 1790s to reduce the multiplicity of dram shops’, boozing shops’, whiskey houses’ and tippling houses’, and to confine their hours of opening.65 Yet, as the preoccupation with the demeanour and deportment of the lower class’ and the money they squander[ed]’ on alcohol attests, most comment was from on high, and it echoed the inherent hierarchical assumptions that shaped contemporary attitudes on virtually all questions. Disapproval was expressed on occasion of the violent behaviour of the drunken young buckeens’ who sometimes terrorised the streets of Dublin, and, still more cautiously, of the half mounted gentlemen’ (immortalised by Jonah Barrington) whose propensities for over-indulgence was hardly less developed.66 It is a measure of the fundamentally elitist perspectives that were articulated that there was little or no open discussion of the place of alcohol in life or acknowledgement of the reality, since alcohol was safer than water, that alcohol was consumed daily in most households, and that its provision was a priority for households—domestic and institutional. Indicatively, Dublin Corporation authorised the construction of a brewing facility (‘brewhouse’) by the Blue Coat School in 1707 ‘whereby the number of poor boys maintained there may be encouraged by the frugal management of brewing their own drink’.67 A minority of domestic households also brewed beer, but since beer and cider were normally consumed by servants, and the extant regulations discouraged the domestic production of beer, it did not liberate them from the need to purchase wine and spirits.

The volume of wine purchased by households varied greatly, but most acquired what they needed to permit its daily consumption. Even the Cosbys of Stradbally, Co. Laois, when the abstemious Pole Cosby was head of the household, consumed two hogsheads annually (or 2.8 pints a day) in the 1710s. By comparison, the £260 spent on wine by the de Vescis of Abbeyleix, Co. Laois, in twelve months over the period 1752–3 would have allowed them to purchase fifteen hogsheads of choice claret’ which equated to 21 pints daily.68 This may not seem far removed from the bibulous world of Barrington’s half mounted gentlemen’ but it was not excessive for a household of this size. Saliently, the Bakers of Ballaghtobin, who maintained a palpably smaller household in nearby County Kilkenny at the beginning of the nineteenth century, purchased their claret in bottles; they ordered it ten dozen at a time, along with sherry, madeira and Lisbon in slightly smaller quantities and port by the pipe.69 This would have provided plenty of opportunity for excess had they been so minded, but like Jonathan Swift, who purchased six hogsheads a year, the most striking feature of their alcohol intake was not its scale but its regularity. Swift drank, he admitted, on occasion to encourage cheerfulness’ and because he found it eased the vertiginous condition that long bothered him. Yet, his normal daily intake of a bottle (c. 1.25 pints) a day, was well within the parameters of what was perceived as normal.70 Women were assumed to drink less, but since Katherine Conolly advised her sister Jane Bonnell that ‘2 or 4 glasses a day will nather doe you nor me hurt, for that is my stint at dinner’, it is not surprising that a hogshead of wine was a welcome gift or that it was customary to maintain a substantial stock in the home since the consumption of alcohol was almost as routine as tea drinking became in the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries.71 Moreover, the habit extended well beyond the ranks of the elite. When the household effects of Nicholas Walsh, a medical doctor with a practice in Cork, were auctioned in 1778, they included two hogsheads of choice claret, one in bottle and one in timber’.72 Even successful tradesmen prided themselves on the quality of the wines they served: when the traveller Courtney More was invited to dine by a wealthy tailor’ in Dublin in 1806 his meal included an excellent claret’.73

The ease and familiarity with which alcohol was treated in the domestic spaces of the elite and middling sort was encouraged by the prevailing perception that, consumed in moderation, it was possessed of therapeutic qualities.74 Echoing Katherine Conolly’s advice to her sister, Richard Lovell Edgeworth alerted Josiah Wedgeworth in 1788, when the latter experienced indisposition’, that he had twice restored myself to tolerable health by relaxation, and by increasing my quantity of daily stimulus in the form of three or four glasses of claret, not port, and half a pint of porter’.75 Given his dislike of excess, Edgeworth’s advice was noteworthy, and it dovetailed with that of some of the best physicians in the land. Some 50 years previously, Edward Barry (1696–1776), who later became the physician general, counselled a patient not to exceed’ a quart of brandy a day, and though this instruction was offered cautiously as the beneficiary was disposed to greater self-indulgence, Barry’s unwillingness to attempt dissuasion was telling.76 It was indicative of the belief, anchored in humoral medication, that the regulated consumption of alcohol on its own or in tandem with other ingredients was intrinsically beneficial. Significantly, Thomas Sheridan, the author and schoolmaster, imbibed a concoction that included whiskey as well as garlic, bitter orange, gentian root, snake root and wormwood to treat asthma.77 It is not clear if this remedy relieved Sheridan’s pulmonary travails, but the desire for relief that caused him to have resort to it was no different to that which encouraged others to have recourse to usquebaugh, or rectified spirits of whiskey for family use’ for making into tinctures and other medical potions.78

If the alimentary and medical benefits to be derived from alcohol provided a foundation upon which a case in support of its consumption could be constructed, there is no denying that it was also consumed because of its mood-altering qualities. As well as Swift, many were thankful for a healing brimmer of claret’ at moments of personal difficulty such as the bereavement of a trusted friend or colleague.79 The inclusion of ‘drinking’ among the recreations of the inhabitants’, both native and settler, of County Fermanagh in an account of life in the early eighteenth century demonstrates that this attitude was not exclusive to the elite, but it is also clear that drinking was not simply a recreational activity—it was integral to the familiar occasions and the festive calendar that punctuated the routine cycle of living. It was, for example, appealed to equally to mark birth as well as a death:

They bury none except a beggar without a good store of dram; and if the deceased be not of substance to order his burial solemnity, his friends and neighbours do meet and make a contribution among themselves to see him buried with credit, these inhabitants generally being so united in manners and customs that a poor cotter would sooner venture the ruin of his poor family before he would see his child christened without a good store of a dram, to see his neighbours and landlord merry with him.80

Signally, the empathy manifested by the author of this narrative was rarely present in the accounts of those of a higher social station who commented on Irish funeral customs. Indeed, unease with the quantity of whiskey and tobacco consumed upon these occasions’ dovetailed over time with specific antipathy to the great vice . . . [of] drinking spirits’.81

It may be that the transition whereby the consumption of alcohol by the population at large evolved from an occasional pursuit, as it was in County Fermanagh in 1718, to become a daily activity, which was the position as the eighteenth century drew to a close, was already underway in the early 1740s when Isaac Butler offers a rare insight into the way in which whiskey was consumed by the rural population of County Cavan:

Aquavitae or whiskey, which is greatly esteemed by ye inhabitants, as a wholesome balsamic diuretic, they take it here in common at and before their meals. To make it the more agreeable they fill an iron pot with ye spirit, putting sugar, mint and butter and when it hath seeth’d for some time, they fill their square cans which they call meathers, thus drink out ym to each other.82

Though Butler noted that drinking might continue until those present were intoxicated, the reference to the fact that it was consumed in a modified form with food suggests that the population had not entirely forsaken the approach described in 1718. If so, it was not to continue, as reports of the drinking practices of the populace in the second half of the eighteenth century indicate that drinking in excess’ was endemic in town, city and country. It was made possible by the plentiful supply of cheap’ whiskey, which was the most striking consequence of the surge in spirit production that characterised the later decades of the eighteenth century.83 This provides a context for Charles O’Conor’s claim, made in his ‘statistical account of the parish of Kilronan’, Co. Roscommon, in 1773, that annually every cottier distilled his oats into spirits, and every cabin became a whiskey house until the spirit was drunk’. Many smallholders doubtlessly followed this pattern and distilled for their own consumption, but others, as the inhabitants of Manorhamilton’, Co. Leitrim, made clear in 1782 when they protested against the 1779 act against distilling’, did so ‘to support themselves and family . . . [as] the distilling of whiskey . . . brought an immediate return to them in cash’.84

As well as the greater availability of home-produced poitín and duty-paid whiskey, popular drinking was facilitated by the greater willingness of those who participated in the rich calendar of festive and celebratory occasions that the populace observed to drink heavily,85 and by a sharp increase in the number of drinking establishments. The numbers of the latter in contemporary accounts are probably inflated, yet claims by Isaac Butler that almost every house’ in the early 1740s on the great road’ between Belturbet, Co. Cavan, and Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh, have for public sale, aquavitae or whiskey’ are supported by a similar observation from Strabane, Co. Tyrone, nearly two decades later.86 Even discounting for hyperbole, these impressions echo accounts that suggest that most of the country’s cities and towns sustained large numbers of taverns, alehouses and dram shops. John Rutty’s often cited computation that there were 300 taverns, 2,000 alehouses, and 1,200 brandy shops in Dublin in 1749 cannot be corroborated but it is not inconsistent with assertions that there were 240 dram shops’ in Limerick in 1790 and ‘500 alehouses and taverns in Cork’ in 1806.87 Furthermore, this was not identified by the populace as a problem; on the contrary, they were more likely to express unease at improving landowners who sought to limit the number of such premises. This was the experience of Sir Thomas Prendergast, 2nd baronet, whose decision to ‘allow but six houses to sell liquors’ in the town of Gort, Co. Galway, in the 1750s, was regarded as a great hardship’.88

Given the difference between the prices charged by the retailers of whiskey and claret,89 and the care that tavern proprietors took to make it known that they stocked the nicest wines and spirits’,90 it was inevitable that the venues to which different categories of customers were drawn also varied even if the outcome—intoxication—was shared. Based upon the little that is known of the ‘dram shops’, and allied low-end alcohol retailers, there is good reason to believe that they were rude establishments that sold alcohol (primarily whiskey and its punch derivatives) at a cheap price without alimentation to the artisans and labourers that were their customers.91 This was a style of imbibing quite different to that pursued by the elite and middling sort, who when they frequented premises that sold alcohol, were more likely to do so in the company of likeminded individuals that dined together. As the frequent reference in the advertisements inserted in the press by tavern owners to the availability of rooms’ for large or small parties’, and to the availability of dinner’ by arrangement, taverns catered for a clientele that could afford to eat and drink, and which frequently did so as part of a club or society.92 The consumption of alcohol was, as this suggests, integral to the emergence and growth of the recreational, associational and political world of the elite and middling sort. Moreover, it served a crucial purpose since it was integral to the forging and maintenance of personal relationships that were necessary for the conduct of civil and political activity. These certainly took different forms. In the recreational realm, it can be perceived in operation in the gatherings that filled the long evenings that followed a day’s racing, hunting or cockfighting. Much that has survived of these bacchanalian occasions may not always reflect well on the participants. Arthur Stringer’s cautionary tale of the good huntsman’ who first drank himself out of his expert sense, secondly out of his money, thirdly out of his service and, consequently, out of his head, fourth, out of his reputation, fifthly, out of his health, and lastly, out of his life’ was clearly apocryphal.93 Yet, accounts of identifiable figures such as John, Lord Eyre, whose gatherings at Eyrecourt, Co. Galway, were famously bibulous, were grounded in real encounters. Moreover, he was not atypical, as individuals such as Eyre bear more than a passing resemblance to the archetype immortalised by Arthur Young, who hunt in the morning, get drunk in the evening, and fight the next morning’.94 Such figures were not unique to Ireland, of course. George Edward Pakenham’s observation after a delightful’ season hunting in County Westmeath in the 1730s that the fox hunters [in Ireland] live much after the same manner as in England and drink as hard’ offers a proper caution against stereotyping the Irish aristocracy and gentry as exceptional in this respect.95 Even individuals like Eyre, who was personally very limited (as Richard Cumberland’s memorable pen portrait attests), and those who were regular presences at his bacchanals contributed in a practical way to the nurturing of the sports of racing, hunting and cockfighting by combining purposeful recreational association with self-indulgence. This is not how it was seen by contemporaries (who promoted improvement of the self as well as society) and has generally been presented by historians since, but one would be hard pressed to demonstrate that such revelries served a less useful purpose than the bibulous electoral entertainments that punctuated the century, which, for all the criticism properly directed their way, facilitated the operation of the deferential politics that defined the era.96

One may be less equivocal as to the usefulness of official entertainments mounted to receive visiting dignitaries be they lords lieutenant or judges of assize, or the private celebrations such as greeted the birth of an heir to a landed estate.97 With respect to the former, the Corporation of Kilkenny was aware that it had exceeded what was proper in 1703 when it directed that the conduits [should] run with claret’ to mark the arrival of the recently sworn lord lieutenant, James, duke of Ormonde, to the city. However they, and other local authorities, sustained the ‘customary’ practice of entertaining judges on circuit, while royal anniversaries, military victories and traditional commemorative occasions were often accompanied by the provision of generous amounts of alcohol which, as instanced by the celebration in Dublin of Admiral Edward Vernon’s achievements in the War of Jenkins’ Ear in 1740–1, might lead to overt displays of public drunkenness.98 Be that as it may, officials were predisposed to regard these events indulgently, because such exhibitions of public euphoria had manifested their value since they were inaugurated in England in the sixteenth century, and introduced into Ireland in the early seventeenth.99 Furthermore, they continued to look benignly upon such displays. When Charles Abbot stayed the night at the best inn’ in Armagh in 1792 he noted that the commissioners in the town for the purpose of executing in an Equity cause’, brought their own piper from Dublin’, and that, as in England upon such occasions’, the night was marked by ‘drinking and singing’.100

Such events could be difficult for an outsider to comprehend, as evidenced by the angry reaction of an American visitor to successive nights at an inn in Castleisland, Co. Kerry, in August 1797 when ‘a parcell of the noiseyest drunken savages . . . kept up their dissipate[io]n with carousing and singing, or rather screeching and roaring, ’till break of day’.101 There was, as this suggests, a lot of socialising and frequenting of taverns that seemed only to result in raucousness and inebriation, but drinking (whether it resulted in intoxication or not) was seldom purposeless or without implication.102 Shortly after his arrival to take up a law office in Ireland in 1725, the future lord chancellor, John Bowes, observed of those of his peers for whom ‘drinking is the business of their leisure hours’, that they were incentivised to interact in this manner by an awareness of the value of networking.103 As someone who preferred to stay at his desk, Bowes identified alternate means to preserve my rank in business’, but there were many for whom this was either not an option or who (unlike Bowes) found drinking congenial. Major General Thomas Earle was one. As a newly appointed lord justice, it was in his interest to get to know the gentlemen with whom he would have to engage. With this in mind, he reported to his colleagues from County Kilkenny in 1702 that he was ‘hard at work “buckhunting” together with an application of as much drink as I am reasonably able to perform in order to familiarise myself in such manner with the gentlemen of the country’.104

William Wogan and Katherine Conolly offer still another perspective on the positive usages to which alcohol was put. Both possessed an intimate familiarity with the dining and drinking habits that Earle embraced and Bowes disliked, and both were sufficiently aware of its import to perceive the value of alerting absent friends that they had recently raised a glass to their good health.105 Toasting was, as this suggests, a matter of consequence in the private as well as the public realm. Calling toasts could be still more significant. It was, for instance, the means by which Henry Boyle demonstrated the sincerity of his apology when, having misread the intentions of the ailing William Conolly, he made it publicly known by calling a toast to the speaker that he had only expressed interest in the speakership of the House of Commons because he believed Conolly was not going to seek re-election.106

Though they had much in common when it came to such matters, Irish practices were not always accurately read by officeholders and visitors from England, whose arresting characterisations of the culture of drinking and, in particular, the manner in which toasting seemed to lend itself to egregious excess, has been invoked to support the conclusion that Irish Protestant society was alcohol fuelled. There can be no doubt but that certain English visitors, schooled in the culture of politeness then in the ascendant in Great Britain, were appalled by their encounters with excess. The vivid, and often quoted, descriptions of John Boyle, fifth earl of Orrery (Fig. 5), in the mid-1730s, and the sharply critical observations of the fourth earl of Chesterfield, who was briefly lord lieutenant in the mid-1740s, of the link then obtaining in Ireland between the ‘quantity of claret’ that was put on the table and ‘mistaken notions of hospitality and dignity’, suggest that they had cause.107 Orrery’s accounts are certainly arresting, as the following description of an event in Cork in 1737 attests:

FIG. 5—John Boyle, 5th earl of Cork and Orrery, attributed to Isaac Seeman, c. 1735–45. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

I have been at a feast. . . .Nonsense and wine have flowed in plenty, gigantic saddles of mutton and Brobdingnaggian rumps of beef weigh down the table. Bumpers of claret and bowls of white wine were perpetually under my nose, till at last, being unable to bear the torture, I took advantage of a health, at which we were all obliged to rise, and slipt away. . .. This short sketch may give you some faint idea of our entertainments in this part of the world. They are esteemed according to the quantity, not to the quality of the victuals, be the meat good or be it bad, so that there is as much as would feed an army . . . I . . . cannot help wondering what mansions in the Elysian fields allotted to those heroes whose delight consists in variety of folly, distraction and drunkenness.108

Orrery’s repugnance at this display is unambiguous. It is also not unique. However, his arresting characterisation of the ‘glorious memory Hibernian’ as ‘a Yahoo that boasts the glorious and immortal memory of King William in a bumper without any other joy in the Revolution [of 1688] than that it has given him a pretence to drink so many more daily quarts of wine’ is also a caricature.109 When William Taylor, Viscount Perceval’s agent, addressed this issue in advance of the arrival in Ireland in 1731 of the heir to the Perceval estate he presented a contrary perspective. He advised Viscount Perceval that though Ireland possessed a deserved reputation for ‘hard drinking’, this was no longer justified: it was, he explained, ‘reckon’d churlishness to withhold liquor from a person who likes to drink, yet it is accounted ill manners to press it upon those who show a dislike to it’.110 Moreover, this remained the case, as both the urbane chief baron of the Court of Exchequer, Edward Willes, and Arthur Young confirmed by their personal experiences.111 Additionally, when Henry Penruddocke Wyndham visited the country in 1759, he noted that even when the bottle circulated freely, individuals were not required to charge their glass other than at their own pace.112 Clearly, Orrery’s experience was not true of every company.

This is not to suggest that the practice of political toasting did not permit excess, but it may be that Orrery’s political as well as behavioural antipathy to what he encountered caused him to exaggerate (Fig. 6). If he was more attuned to the contested nature of political toasting in Ireland, he might have better understood the passion with which the ‘glorious memory’ was saluted, and the import of so doing. Saliently, Irish Jacobites risked a fine, imprisonment, a stretch in the pillory or assault ‘for drinking the Pretender’s health’ or calling other treasonable’ toasts,113 while Irish Tories chose either to avoid toasting altogether or, emboldened by Peter Browne, bishop of Cork, sought to discourage the fast growing cult of William of Orange by questioning the appropriateness ‘of drinking in remembrance of the dead’.114 Irish Whigs, by contrast, used every occasion available to them to assert their identity, and as attested to by the publication in 1712 of an ‘exact’ list of the healths drank’ to honour King William’s birthday in Dublin in that year, and, following his accession in 1714, of those drank on George I’s birthday, they precociously perceived the usefulness of publishing lists of the toasts called.115 Furthermore, in the quarter century following the inauguration of the Hanoverian succession, when their brand of political Protestantism was firmly in the ascendant, the pressure to be seen to conform was so compelling that a man who declined a loyal bumper’ in public company took the risk of having his constant and good affection to the present happy settlement’ questioned.116 As a result, political toasting achieved such symbolic and practical ascendancy in the anglophone public realm in the 1730s and 1740s that when fissures appeared in the 1750s it was logical, such was its usefulness in generating group identity, that the toast was appealed to in a new and novel way.

FIG. 6—Gentlemen singing and drinking toasts around a table by Henry Brocas, 1762–1837. Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Ireland.

Though it can reasonably be portrayed as a power struggle in order to determine which faction was in the ascendant politically, the money bill dispute of the mid-1750s stirred ideological currents that were to possess a central place in Irish political discourse for two generations. Questions were posed at the time as to the extent to which the Patriots who seized the political initiative in the 1750s subordinated personal ambition to the virtue they routinely invoked in the toasts they called, but these are of lesser import here than the manner in which the coalition of factions, interests and individuals that rallied round Henry Boyle took political toasting from the preponderantly communal Protestant world in which it had been located since 1715 into the more contested arena of factionalised politics.117 The key to this was the Patriot Club, a new departure in Irish political life, which provided a structure in which those who supported Boyle could assemble and, through the medium of the political toast, promulgate a political message that served the purposes of advancing a statement of policy and binding those present in a common cause. Thus drinking answered two purposes; it united the company and sharpened the wit or malice of the individual against the common enemy’, Edmund Sexten Pery noted perceptively.118 Credit for this has been assigned to Anthony Malone, the MP for County Westmeath, though the reality of the matter is that toasting would not have succeeded so spectacularly but for the fact that it synergised with the burgeoning associational impulse then gathering pace.119 In any event, the establishment of Patriot Clubs across the kingdom, and the adoption of the tactic of raising toasts to the individuals, interests and, most importantly of all, to the complex of political convictions, statements of sincerely held principle, and shibboleths that defined contemporary patriotism was an idea that had found its time. Initiated in the febrile atmosphere of the winter of 1753–4, freeholders, independent electors’ and individuals came together across the kingdom to affirm their traditional commitment to protect and secure their liberties against popery and arbitrary power’, and their more recently acquired resolve that those whom they unjustifiably defined as ‘the enemies of the nation’ would not prevail.120 Given that the toasts, which were the form in which these convictions were conventionally articulated, bore closer comparison to slogans than developed political statements, it can be suggested that this tactic was ideal for a community that was already familiar with this medium, and which was practised at assigning meaning to such phrases as ‘the glorious memory’ and Popery and arbitrary power’. However, this would be to sell these events short. Toasts, then and later, were not called for singly or in isolation. A typical meeting might produce 40, 50 or even 60 toasts. Furthermore, while it is the case that a substantial proportion of those called at a Patriot gathering in the 1750s were little different to those uttered at a typical Williamite anniversary, what gave them a distinct register was the manner in which they combined traditional Whig slogans, loyalty to the Hanoverian monarchy and the Protestant succession, statements of Patriot principle, professions of fellowship, and personalised abuse directed at their opponents into a comprehensive, if not entirely coherent or intellectually subtle, message.121 It is improbable that those who were present were equally persuaded of the merits of all the toasts to which those who assembled raised their glasses, but it was acknowledged by critics, sympathisers and neutrals alike that the combination of alcohol and toasts served very effectively to unite those present in support of their champions, to reinforce them in their determination to adhere to their position, and to provide them with a corpus of ideologically informed slogans to which they, and those of like mind, could, and did, appeal. Furthermore, the fact that the toasts uttered were the central focus of the reports of those gatherings published in the popular press ensured that the message was not confined to those present.122

Despite the fact that the money bill concluded in a manner that many of those who engaged in political toasting found disappointing, the episode had a long-term legacy. Traditional loyalist toasting, in the manner of that pursued during the first half of the eighteenth century, continued largely unchanged, but the second half of the century spawned an array of bodies for whom the toast was as one of the key means through which they forged organisational unity and conveyed their views both to their members and to society at large. These included loyal societies of Protestant tradesmen for whom this was a convenient way of recalling the welcome defeat of Jacobitism in the rising of 1745.123 It was put to still better use by reform-minded organisations such as the Society of Free Citizens and the Volunteers. Each appealed actively to the toast as a means of generating esprit de corps, and elaborating an identifiable political strategy by invoking current as well as historical issues, individuals as well as events, and major issues of principle as well as passing controversies. They also used the toast as a medium to promulgate their message. Given that the Society of Free Citizens subscribed on one occasion to a forbidding 92 toasts, it might seem that such displays were self-defeating, but the enduring capacity of improper toasts . . . drank at public meetings’ to excite disquiet in the highest corridors of power indicates otherwise.124 Moreover, the practice not only survived, it flourished in the still more participatory milieu of the 1780s and 1790s, and beyond, as organisations as diverse as the Lisburn Constitutional Club, the Aldermen of Skinner’s Alley, the Volunteers and the United Irishmen, and following the change of mood in the wake of the 1798 Rebellion, conservative interests perceived the manifold benefits of structured, purposeful drinking.125

Occasionally, voices, ill at ease at the connection between toasting and drunkenness were raised in protest, but they were battling against the prevailing behavioural tide.126 The burgeoning associational impulse, which contributed to the emergence of the Patriot Clubs, also contributed to the foundation of scores of non-political clubs which made dining, and by implication, drinking their raison d’etre. Though each possessed its own character and purpose, the evidence of the Bar Club, which was established in 1771 to meet the nutritional and convivial requirements of young barristers in Dublin, indicates the centrality of drinking to male sociability. Given the age, status and comparative wealth of its members, it may be that this club was not typical. There were others, which demanded that their members behaved with greater probity, but the links that one can draw between the conduct of members of the Bar Club and the young men whose revels were chronicled by Jonah Barrington cautions against concluding that these were an unrepresentative minority disposed to bacchanalian excess. What can be stated is that the link, noted by John Bowes in the mid-1720s, between drinking and recreation, and between dining and drinking by Henry Penruddocke Wyndham in 1759, had not just survived, it had been boosted by the proliferation of clubs and societies that made dining and drinking their defining activities. It was increasingly commonplace in the second half of the eighteenth century for bodies of men to assemble in clubs and in societies at 4 p.m. to conduct business, and having done so to commence dining at about 5 p.m. and to continue eating and drinking until 9 or 10 p.m., by which time those who had lasted the pace were as likely as not ‘very drunk’.127 This was how many liked it. It is a fair measure of the depth to which a culture of drinking had penetrated even respectable society by the mid-1780s that it was difficult on occasion, even for those like Lord Charlemont who were studiously proper, to avoid getting drunk.128 Indicatively, this culture was firmly rooted in the political sphere with the result that lords lieutenant and chief secretaries with little interest in drinking were at a palpable disadvantage by comparison with those who did. The frequency with which senior office holders were called upon to demonstrate their capacity to drink heavily varied from administration to administration, but the fact that one could not draw a clear distinction between the consumption of alcohol and work in spheres as diverse as sport and politics is revealing of the extent to which it had penetrated everyday life.129 It was possible in England in 1791 to assert that drinking healths was growing out of fashion’.130 It was not possible to make a similar claim for Ireland, for though the elite devoutly wished that the lower classes would forsake whiskey for the good of the country, the patterns of sociability that all classes pursued were too closely bound up with the heavy consumption of alcohol to mean it was practicable at this time.

Conclusion

The volume of alcohol imported into and manufactured in Ireland in the eighteenth century permitted its utilisation by every grade and rank of society. Signally, other than the consumption of spirits associated with the lower classes, this was not perceived as a social problem, since alcohol was regarded as an essentially benign commodity. This was most manifest in its usage as a medication, primarily in the form of cordials. Usquebaugh was the best-known Irish cordial, but since whiskey was also perceived (by the populace at least) to possess therapeutic value, it may also have contributed to its consumption mixed with fruit and medical herbs across society. Moreover, the therapeutic value of alcohol also embraced wine, which helped to insulate it from the harsh criticism targeted at spirits in general, and whiskey in particular, and which sanctioned the daily consumption by women of three to four glasses, and by men of a bottle (1.25 pints) of wine a day. Though more inquiry is required, it can be suggested that because alcohol was safer to drink than water (mineral waters excepted131) it was perceived by all classes and interests as a convenient and essentially palatable source of liquid nutrient. The fact that it was also an intoxicant was a complication, but since the stages and implications of intoxication, and its physiological and psychological implications, were far from properly understood, this was insufficient on its own, prior to the surge in whiskey consumption in the later eighteenth century, to inhibit its full integration into private and public life. The alimentary benefits of consuming alcohol in a dining milieu were broadly recognised; its potential as an intoxicant appreciated; its value as a social lubricant acknowledged. In most societies, and at most times, these inducements to consume alcohol are policed, and sometimes kept apart, by law or by custom. This was hardly the case in Ireland in the eighteenth century. One may invoke the impoverishment of the native population, the compelling need for the settler community—Presbyterian as well as Church of Ireland—periodically to affirm their social and political bonds, and new and emerging trends such as associationalism and male sociability in seeking to account for this. However, alcohol’s intrinsic appeal should not be overlooked. The fact that society has chosen for nearly two centuries to give precedence to the negative consequences of alcohol consumption, ought not to obscure the reality that, viewed in the round, life in eighteenth-century Ireland was more endurable because of its availability.

* Author’s e-mail: james.kelly@spd.dcu.ie

doi: 10.3318/PRIAC.2015.115.14

1 See Elizabeth Malcolm, Ireland sober, Ireland free: drink and temperance in nineteenth-century Ireland (Dublin, 1986), 21–55 for an excellent account.

2 E. B. McGuire, Irish whiskey: a history of distilling in Ireland (Dublin, 1973), 91–212 passim; Patrick Given, ‘Calico to whiskey: a case study of the development of the distilling industry in the Naas revenue collection district, 1700–1921’, unpublished PhD thesis, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, 2011, 66–118.

3 Samuel Morewood, A philosophical and statistical history of the inventions and customs of ancient and modern nations in the manufacture and use of inebriating liquors (Dublin, 1838), 726. Others, notably L. A. Clarkson and E. Margaret Crawford, have tabulated the ‘retained imports into Ireland’ in wine (tuns) and spirits (gallons) based upon the Ledgers of import and exports, Ireland (CUST15) in The National Archives (TNA). Their table does not allow one to distinguish between domestically produced and imported alcohol: Clarkson and Crawford, Feast and famine: food and nutrition in Ireland 1500–1920 (Oxford, 2001), 53–5.

4 The precise figures are 29.4% and 70.62% calculated from the data provided in Morewood, A philosophical and statistical history, 720.

5 The preferred temporal measure employed to date has been the decade. The decennial totals generated by Malcolm, Ireland sober, Ireland free, 22ff have been cited and used by S. J. Connolly, Toby Barnard and Breandán Mac Suibhne, and her summation that ‘during the 1720s . . . duty was paid on some 5.2 million gallons of spirit, 5.3 million barrels of beer and 12.4 million gallons of wine’ has informed the conclusion that alcohol consumption was high. Connolly has described the wine figure as ‘astonishing’ (Religion, law and power: the making of Protestant Ireland 1660–1760 (Oxford, 1992), 66); Barnard terms it ‘startling’ (‘Integration or separation? Hospitality and display in Protestant Ireland, 1660–1800’, in Laurence Brockliss and David Eastwood (eds), A union of multiple identities: the British Isles c. 1750-c. 1850 (Manchester, 1997), 137). It has also shaped Breandán Mac Suibhne’s interpretation: ‘Spirit, spectre, shade: a true story of an Irish haunting or troublesome pasts in the political culture of north-west Ulster 1786–1972’, Field Day Review 9 (2013), 154–7, and Table 1. By my calculations, duty-paid wine imports in the 1720s amounted to 12.257 million gallons (see Table 1), which, assuming there were 200,000 wine consumers, amounted to a less than remarkable 1.3 pints (or c. 1 bottle a day). Decennial figures tend by reason of their order to encourage the conclusion that Ireland was gripped by a major alcohol problem; I think the evidence is more ambiguous.

6 See L. M. Cullen, ‘Problems in and sources for the study of economic fluctuations 1660–1800’, Irish Economic and Social History 41 (2014), 8, 18; L. M. Cullen, ‘The Irish food crises of the early 1740s; the economic conjuncture’, Irish Economic and Social History 37 (2010), 1–23.

7 McGuire, Irish whiskey, 128–34; Malcolm, Ireland sober, Ireland free, 23.

8 Legislation approved in 1758 (31 George II, chap. 6) raised the minimum size of stills to 200 gallons, while greater rebates were offered in 1779 to those with a capacity of over 1,000 gallons (19 and 20 George III, chap. 12). One compelling index of the efficacy of the Revenue Commissioners, and of the impact of regulation on the production of spirits is provided by the decline in the number of licensed stills. According to evidence given to the House of Commons in 1791, the number declined from 1,212 in 1781 to 246 in 1790: The parliamentary register, of history of the proceedings and debates of the House of Commons of Ireland (17 vols, Dublin, 1782–1801), vol. xi, 73. The figures assembled by Patrick Given from papers submitted to parliament show some variation from these, but they confirm the trend, and they demonstrate that the pattern of decline continued; by 1800 the number of licensed stills stood at 165, and it had fallen further, to 51, by 1806: Given, ‘Calico to whiskey’, 200. See McGuire, Irish whiskey, 127–32; 5 George II, chap 3, section 13; 11 and 12 George II, chap 3; Malcolm, Ireland sober, Ireland free, 23; Minutes of the Revenue Commissioners, 23 February 1733, 17 September 1744, and 10 February and 1 April 1748 (TNA, CUST/1/25, f. 53, 1/38 ff 3, 9, 55v, 1/44 ff 32, 93); Aidan Manning, Donegal poitin: a history (Letterkenny, 2003); K. H. Connell, ‘Illicit distillation’, in Connell, Irish peasant society (Oxford, 1968), 1–50.

9 Mac Suibhne, ‘Spirit, spectre, shade: a true story’, 154–7.

10 Minutes of the Revenue Commissioners, 27 February 1748 and 11 December 1756 (TNA, CUST, 1/44 f. 50, 1/59 f. 84v); Public Gazetteer, 30 July and 9 August 1763, and 3 May 21 October and 15 November 1766.

11 Minutes of the Revenue Commissioners, 20 March, 7 July, 9 August and 11 September 1758 (TNA, CUST, 1/59 f.126v, 1/62 ff 59, 95v, 129v).

12 Minutes of the Revenue Commissioners, 19 October 1759 (TNA, CUST, 1/63 ff 144v-5).

13 Sixteen stills were seized by the gauger of Naas district, in Trim and Naas districts in the summer of 1759, for example: TNA, CUST1/63 f. 110.

14 Manning, Donegal poitín, 105–19; Connell, ‘Illicit distillation’, 1–50; McGuire, Irish whiskey, 388–408. For evidence of the endurance of illicit distillation into the 1790s and beyond on the eastern seaboard see: Dublin Morning Post, 1 June 1790; Ennis Chronicle, 2 February, 20 April and 14 May 1801. It was much more commonplace in County Clare, for example: see the Ennis Chronicle, 14 July and 22 December 1796; 19, 22 and 26 January, 2, 9 and 23 February, 23 March and 25 June 1801.