Towards a new domestic architecture: homes, kitchens and food in rural Ireland during the long 1950s1

Department of Design and Computation Arts, School of Canadian Irish Studies, Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec, H3G 1M8, Canada

[Accepted 16 November 2014. Published 22 May 2015.]

Abstract

An understanding of food habits and rituals is deeply enriched by factoring in the impact of the spaces in which they take place. This study explores the effects on the domestic foodscape—the physical built environment of home including its contents—primarily during the 1950s, when rural Irish households were in the midst of transformations to the visual, material and spatial experiences of the kitchen brought on by new foods and/or technologies. The life-changing potential of this modernised environment was acknowledged by certain influential public agents such as the Electricity Supply Board of Ireland, the Irish Department of Agriculture, the Irish Countrywomen’s Association, and the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland, and they actively sought to ameliorate housing conditions in order to address quality-of-life issues, contribute to agricultural productivity and help to curb the flow of emigration. This modernisation strategy necessarily took into account certain proclivities in terms of food choices or preparation methods as well as wider cultural practices that were deeply embedded in Irish everyday life. Hence what emerges is a juxtaposition of the traditional, with new tastes, practices and expectations.

Introduction

Readers of the REO News (published by Ireland’s Electricity Supply Board (ESB)) were treated, in December 1950, to an updated version of the Cinderella story in image and verse (see Fig. 1). The scene opens with the unfortunate maiden in her traditional Irish dwelling, with its small window, shadowy kerosene lamp and a three-legged iron pot hung over an open fire. She is ‘[w]orn with all the work to do’ and hence ‘[s]taying home without a fella’, which would have been read as an unfortunate circumstance in 1950s rural Ireland.2 Hope is at hand, however, as the Prince Charming of this edition, the cartoon mascot of the ESB, Johnny Hotfoot, is both ‘elegant’ and ‘quite fond of farming’, and his vast and fertile acreage, proof of his stature and prowess, is picturesquely portrayed complete with castle ruins in the distance. A perfect specimen of the traditional male hero, then, he nevertheless also subscribes to the most up-to-date principles of domestic modernity, evidenced by his kitchen replete with mod cons: electric light, an electric kettle, a cooker, an iron and a washing machine, and an enormous refrigerator by the standards of the time. Such entangled hybridity of traditional and modern ethos—surprising even to the cow that ventures into this idyllic domestic scenario—drives the happy-ever-after narrative. Johnny’s fondness for ‘labour saving’ has precipitated a lavish use of electricity, and ‘[p]lugs and sockets around the place’ enable Cinderella to transform into a kind of mid-twentieth-century domestic icon, a glamorous, affluent, comfortable, married, lady of leisure.3

FIG. 1—‘The Adventures of Johnny Hotfoot: No. 2. The Transformation of Cinderella’ (REO News IV: 1 (December 1950), 14). Reproduced by permission of the Electricity Supply Board.

Given that this essay sits within a volume devoted to food and drink in Ireland, what is most relevant in the aforementioned parable is its depiction of an idealised transition brought on by modernisation impulses, from hearth (or other solid-fuel cooking) to electric (or gas), and from the multipurpose living space of the kitchen in the vernacular Irish ‘cottage’ to the specialisation, in the modern home, of zones for food preparation and the separation of domestic spaces related to eating and leisure. This study explores the effects on the domestic built environment brought on by evolving Irish and international food systems during the 1950s (a momentum that continued through to the 1970s), when families throughout Ireland were experiencing—if not necessarily to Mr and Mrs Hotfoot’s advanced degree—the life-changing alterations that new technology brought to their dwellings, especially their kitchens.4 Electric or gas cookers, refrigerators, fitted (built-in) cabinets, running cold, and, later, hot water made their way into and transformed the visual, material, and spatial experience of the kitchen and, in the wider context, what Seamus Heaney called ‘[t]he rooms where we come to consciousness’, that most essential space that humans occupy out of the womb—home.5

Food-related interactions within the household fundamentally motivate the practices of everyday life. An understanding of food habits and rituals is deeply enriched by taking into consideration the impact of the spaces in which they take place. In mid-twentieth-century Ireland virtually every family (except those in the most remote areas) gained the capacity to alter food and drink traditions honed over generations, if only through the purchase of an electric kettle: most homes were electrified by the 1970s and this small appliance was a very popular and early electrical purchase even in the most modest households.6 In a country where the phrase ‘put on the kettle’ still ubiquitously rings through kitchens, and where hospitality to visitors often begins with a cup of tea, the true magnitude of even this seemingly small change deserves contemplation.

The Cinderella story of the ESB is only one of a myriad of advertisements, pamphlets, lectures, demonstrations, contests and other attention-gathering phenomena in circulation in the Irish popular culture of the period, and these echoed parallel campaigns in Europe, North America and Australia.7 The Rural Electrification Scheme that began after the end of the Second World War was an additional driving force, and so were initiatives to pipe running water into rural homes.8 Carried into the public consciousness by a variety of stakeholders including the ESB, were modifications in food-related thinking and activity at a range of scales: tools and other aids to facilitate new cooking methods and new foods were popularised and made available for appropriation; new food-related performances—how and where to cook, what to cook, and how and what to eat—were routinely discussed and demonstrated; and a broader culinary gaze, a curiosity about what and how, for example, American women were cooking in their appliance-laden kitchens, was valorised and activated.9

There is compelling evidence that the life-changing potential of the modernised domestic foodscape was acknowledged by at least some influential public agents in Ireland during this period. This term takes as its point of departure the assumption that the physical space of the home and the objects which it contains—the layout of rooms and furniture; the juxtaposition and intermingling of spaces for work and leisure; or the selection and arrangement of the contents of the home, for example—play a dynamic role in the food-related experiences of members of the household. Working from the perspective that Ireland was predominantly a rural and agricultural society and economy, organisations and bodies, such as the ESB, the Irish Department of Agriculture, the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (ICA), and the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland (RIAI), initiated and supported projects aimed at rural dwellers, that showed a perceptive appreciation of the inextricable link between the acts of cooking and eating, and the environment in which they occurred. Moreover, these agents recognised that the quality of that environment had a significant bearing on the well-being of Irish families especially in rural parts of the country. Consequently, the narrative of Irish culinary modernity that these stakeholders appropriated from the international models with which they were acquainted, and strove to activate, was carefully and consciously mediated through a range of projects in order to try to accommodate the widest array of households of the time. Equally worth examining is the fact that this modernisation strategy for food in Ireland necessarily took into account certain proclivities in terms of food choices or preparation methods as well as wider cultural practices which were deeply embedded in Irish everyday life, and these vestiges are reflected in fascinating ways in the output of the campaigners. Hence what emerges is a juxtaposition of the traditional with new tastes, practices and expectations. Mid-twentieth-century Irish domestic food culture was a domain of ‘and’, rather than ‘or’; indeed, that one can still find an Aga-type stove sitting next to the electric or gas cooker in a few present-day Irish kitchens is testament to the durability, in the nation’s collective domestic foodscape, of tradition within the paradigm of the modern.10

Irish domestic foodscapes and the ‘spatial turn’

Key stakeholders who promoted change in the Irish domestic foodscape during the 1950s and 1960s were cognisant of the crucial relationship between the nature of those physical spaces as sites of food (and other kinds of) activity and fundamental quality-of-life issues of their inhabitants. The very sensitivity of these agents to the spatially and materially driven stimuli of everyday life in rural Ireland deserves careful investigation, and resonates with recent work by researchers in architecture and design studies (and other fields) who have devoted attention to what has been called the ‘spatial turn’.11 For scholars undertaking such investigation, architecture is not simply a passive backdrop of walls, floor and ceiling within which people go about their everyday lives— not simply a ‘collection of preexisting points set out in a fixed geometry, a container, as it were, for matter to inhabit’ as Karen Barad puts it. Instead, a particular building may be explored as an ‘iterative (re)structuring of spatial relations’, as a universe dynamically comprised of the relationships, or interactions, between the people who occupy a particular space, the objects it contains, and the forces that operate within it.12 Arising out of the spatial turn, then, is a conceptual framework through which to study the continuous engagement through which each of these elements both gives and receives stimuli in a continuous exchange. It allows us to think about how the physical properties of a kitchen, for example, induce particular behaviours or reactions on the part of those who occupy it—different reactions at different times, under different circumstances, by different people. Branko Kolarevic takes this analytical approach one step further by highlighting two variables that stimulate interactions in the built environment, namely pervading cultural practices and existing technological infrastructures. From his perspective, then, ‘culture, technology, and space form a complex active web of connections, a network of interrelated constructs that affect each other simultaneously and continually’.13 Understanding space in this way, as continually made and remade in a (re)active web of connections that transpire between people, material culture, energies such as light, heat and electricity, and so on, allows us to appreciate in a granular way the implications of mid-twentieth-century efforts to address the link between home, food, comfort and cultural aspirations. Such an understanding thus creates opportunities, in turn, to ponder the complexity of food-related activities in Irish domestic space.

Incentives toward modern kitchen design with particular attention to rural areas

The temporal focus of this essay is primarily the 1950s, a period of social and economic hardship for many in Ireland, especially in rural areas. For most of the decade the Irish economy was stagnant.14 In addition, according to Enda Delaney, ‘[e]xpectations, aspirations and other elements of socio-cultural change’—such as real as well as anticipated standards of living amongst young people—were such that emigration seemed the most reasonable alternative to remaining in rural Ireland.15 The result was the highest emigration rate of Irish citizens, during this decade, in both absolute and relative terms, since the 1880s.16 Rosemary Cullen Owens points out that ‘[t]he effects of post-Famine marriage patterns involving late and low rates of marriage, allied to high celibacy and female emigration rates, [the highest of any European country between 1945 and 1960] were still being felt in rural Ireland into the 1960s’.17 Moreover, Caitriona Clear explains that at this time most women gainfully occupied by working on farms were employed by relatives; she concludes that ‘[o]ral and other evidence suggests that women who were working as assisting relatives [sisters, daughters and daughters-in-law of farmers, for example] up to the 1950s felt themselves to be unusually disadvantaged’.18

Inferior housing conditions were deemed to have played a role, and various social agencies sought to remedy matters. As Mary McCarthy observes, ‘from 1942 onward both northern and southern Ireland began to consider housing as an issue that required serious attention’, and ‘[b]oth governments were willing to improve housing conditions, took steps to quantify the problem and focused on the best way to achieve set targets’.19 Rural electrification in the Republic was one consequence, and the rhetoric of the ESB, as we have already seen, reflected strategies to enhance facilities in the farmhouse itself through electrical interventions, in addition to promoting inducements to install electrical apparatuses in barns or dairies. Two other agencies with social and cultural obligations stand out in this regard, namely the RIAI and the ICA. Working together, these bodies were instrumental in proposing adaptations to the rural domestic foodscape that would raise the quality of life in rural households and augment the experience of women undertaking domestic duties including cooking.

The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland and its members participated in important strategies to recast the experience of the domestic foodscape, by offering advice about and encouraging architectural and designbased remedies. Predominant in this regard was Patrick Delany, an architect with a Dublin practice but an interest in rural issues. In a five-part series of articles on rural housing that appeared in 1953–4, in a magazine called Homeplanning meant for a general (rather than professional-architectural) audience, Delany argued that ‘[i]f within the term “Housing” we agree to include not only four walls and a roof, but also decent services such as piped water, sewerage, electricity, telephone and transport, then lack of housing amenities [in rural areas] is one of the prime causes of the Drift from the Land’.20 Having elicited and received feedback from readers of his series, Delany was further disheartened by what he learned. ‘[F]ar too many of our people are living in the country without even the essential minimum of services’, he wrote, ‘and at great distances from their shops, their neighbours and their work. It is as one would suspect; but the picture painted by their replies is one of deep gloom’.21 Delany consequently set out to offer readers succinct and basic advice regarding how best to undertake new construction in the countryside. Issues that were addressed included the orientation of the dwelling for optimal sunlight and warmth as well as techniques of insulation, and these instructions were meant to stimulate reflection on the part of homeowner and builder alike. It goes without saying that these issues of utility as well as comfort also fundamentally affected the house as a food workspace or site of commensality.

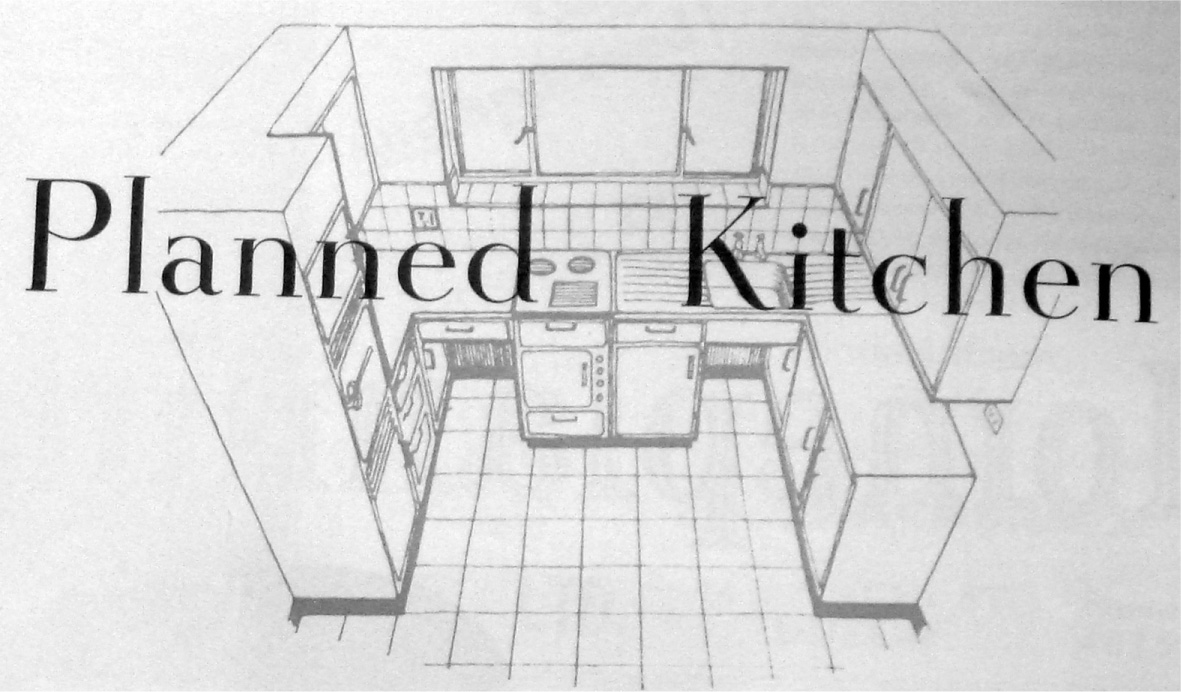

Delany’s next intervention in Homeplanning was a five-part series entirely devoted to kitchen design (not confined to rural homes), called ‘Planned kitchen’. The series was conceptualised as an analysis of general subject matter in the first two parts, with special attention being given to kitchen design in which the cooker was electric, gas and solid-fuel, respectively, in parts three to five. Delany opened the series by asserting that

No one needs to be reminded of the importance of good kitchen design for the comfort and convenience both of the housewife and of her family, no matter how large or how small that family’s income may be. Directly or indirectly, the kitchen affects family nutrition and family life as a whole in a way that no other part of the house can—as is recognized in the clichés ‘the woman’s workshop,’ ‘the hub of the house,’ and so on.22

Kitchen size, layout, storage, lighting and finishes were discussed, and complemented by an illustration on the cover of the February 1954 issue, the one in which the first instalment of his series of articles appeared (see Fig. 2). The image’s caption outlines the kitchen’s pivotal features: a Rayburn cooker embedded in a sleek and efficient space, with ‘[b]uilt-in presses from floor to ceiling [to] avoid dust traps’, and a ‘working table top runs from wall to wall [. . .] bordered by [a] tile surround to avoid splashes’. Storage is made possible through ‘enamel kitchen cabinet[s]’ and a ‘glass-doored china press’ as well as shelves hung under the table surface. On a third wall, not shown, a hanging place rack plus an additional ‘hanging china cupboard with folding table below and a storage cabinet from floor to ceiling’ also helped keep the kitchen organised and efficient. The refrigerator is visible in the image, and the ‘sink with mixer tap’ implies hot and cold running water. Aesthetic features may also be discerned: patterned window curtains are in view, a plant sits on the windowsill, and the reader was advised that the cabinets are cream-coloured and the floor made of red tiles.23

FIG. 2—Front cover of Homeplanning, February 1954.

Notwithstanding this definitive rendering of an idealised foodscape, Delany took a surprisingly flexible view on kitchen planning, thereby making his articles more accommodating to a wider audience in need of design advice. With regard to kitchen layout, for example, he pushed back against the extreme views of international experts who advocated the compartmentalisation of kitchens into discrete and rigid zones, and argued instead that the:

saving of steps, while undoubtedly important, is an aspect [of design] that tends to be over stressed by the ‘scientific’ designer who will quote impressive statistics to show that a housewife can walk 4 miles per day in a badly laid out kitchen and only 2½ miles per day in the same kitchen if well laid out.24

In the article devoted to the all-electric kitchen, Delany offered readers one sample architectural plan, a small kitchen of 10 feet 9 inches × 8 feet 6 inches, realistically intended for a family of four or five of limited budget (see Fig. 3(a) and (b)). In his breakdown of the drawings, Delany created an opportunity for readers to negotiate, for themselves, pragmatic rather than perfect kitchen design, by listing both the advantages and disadvantages of this compromise. Hived off from the other living areas of the house rather than part of an open plan, this space ‘can be small enough to be kept tidy easily’, was ‘planned to secure almost a “laboratory” degree of efficiency’, and ‘takes up a relatively small area, so that in the limited area of the modern small home, more space is left over for other rooms’. However, its ‘chief disadvantage is psychological rather than practical—that is, it is rarely large enough to seem like a room at all, and can be a little depressing to work in for long periods’, although this can be ‘mitigated by giving the window a pleasant outlook’. Also problematic is that it offered no room at all for even the ‘most hurried’ meal, and so ‘the apparent saving of total floor-space is something of an illusion’. Delany also admitted that there was a limited amount of food storage allowed in the design, which had ‘little room for reserve stocks of anything’, and would therefore require ‘[c]areful budgetting [sic] and ordering’. He also warned that while ‘the general lighting is good, the positions of window and cooker make it difficult to see what is in the oven’. Readers may have been left bewildered by this ultimately unresolved kitchen plan, but this approach seems to have been an intentional encouragement to take matters into one’s own hands and to consider the unique needs and particularities of one’s own household. As Delany reminded his audience; ‘[t]here is of course no “ideal” kitchen any more than there can be an “ideal” house’.25 A year later, by the summer of 1955, Delany was broadening his own knowledge by working with members of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association as a representative of the RIAI studying rural kitchen design, and listening to the experiences and recommendations of this team of highly experienced collaborators.

FIG. 3(a)—Axonometric drawing of a small all-electric kitchen designed by Patrick Delany, Homeplanning, April 1954.

FIG. 3(b)—Plan of a small all-electric kitchen designed by Patrick Delany, Homeplanning, April 1954.

The ICA took a leadership position vis-à-vis rural housing that included extensive attention to the introduction of modern methods of cooking and new foods into the kitchen.26 This was achieved through a variety of means. The association was instrumental, for example, in advocating the introduction of running water in rural homes, a necessity that was far from commonplace at the time: even in 1961 only one rural household in eight had running water according to Mary E. Daly.27 In 1954—the same year that Delany prepared his articles for Homeplanning—the organisation obtained financial support from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation in the United States of America, and opened An Grianán, its residential campus located in Termonfechin, Co. Louth. As its ICA organisers proudly noted, ‘through An Grianán, we look forward to promoting national and international co-operation in the field of rural betterment’.28 The agenda included lectures and courses of several days’ duration, and, amongst other facilities, there was a ‘demonstration kitchen . . . to encourage members in the use of electrical and other labour saving equipment, for courses in fruit and vegetable preservation, in dietetics, and in general household cookery’.29

If ICA members now had a destination away from their homes at which demonstrations of modern methods could be taught, the existence of that facility did not preclude extensive measures to take their message out on the road, to the very doorstep of women on their farms. The goal was to be proactive in making direct contact with households throughout the country in an effort to enhance conditions in the home place—including those related to food—by supplementing the knowledge that was available through more passive means such as newspapers or magazines. In 1956 (after at least five years of discussion with the Irish minister for agriculture) the association received funding from the United States Government through cooperation with the Irish Department of Agriculture under what was known as the Grant Counterpart Scheme.30 The mandate of the ICA was to ‘to advance materially the productivity and amenities of Irish agriculture’ by hiring advisors to crisscross the country for the duration of the project, which lasted into the early 1960s.31 Eleanor Butler, a qualified architect and member of the RIAI, was employed by the ICA as a home planning advisor with the responsibility to ‘make the women of Ireland “Housing Conscious” and this she certainly succeeded in doing’ according to Esther Bishop, the Chair of the Grant Counterpart Committee.32 Butler was called upon to help to develop housing policy and practice, for example the design of three houses at the request of ‘one Agricultural officer’ to be used as residences on three pilot farms.33 However, she considered herself at her most effective when visiting local ICA guilds rather than advising at more remote levels, partly because, as she noted, members of other rural-based organisations such as the Macra na Feirme and Muintir na Tíre would also be present, and also because ‘[v]ery often I am invited to visit the homes and advise on the spot’.34 While dedicated, then, to cut as large a swath as possible through the Irish countryside, she nevertheless took a very realistic view of the impact of her consultations with rural families. Her ambition was to ‘try to ensure that every member of the [ICA] could carry out at least one planning improvement in her home during the period of my service’, keeping in mind the financial and social constraints that she knew would have to be overcome.35

Margaret Crowley, a qualified domestic science instructor, began work as the ICA home economics advisor in 1958. Her first task, funded by the Kellogg Foundation, was to complete a year of additional training at the University of Kentucky and elsewhere in the United States, where she was given the opportunity to learn ‘in particular how the field workers reach the woman in her home, there to advise her on her own specific problems’.36 The report Crowley submitted on the completion of the scheme in 1962 is an impressive account of her activities in all 26 counties of the Republic, and it notes substantial attendance at her lectures, many of which addressed kitchen planning, home decoration (including the kitchen) and cooking methods.37 Crowley worked systematically, county by county, through the auspices of local foundations and guilds that organised events at venues such as schools or town halls. Her audience was not confined to ICA members: students, local members of the Macra na Feirme and Muintir na Tíre as well as other interested parties sat in on her sessions. Additionally, Crowley undertook numerous home visits by invitation of their inhabitants in order to offer even more specific advice, and often regretted, in her report, not having had enough time to respond to all such requests; she was estimated to have declined fully half of those who wished to receive this personalised advice.38 Her reports provide a few opportunities by which to learn more about the nature of such consultations: a visit to a home in Co. Monaghan in October 1959, for example, was a ‘[r]e-planning of kitchen to cut off draughts’, while she advised, in Co. Mayo, regarding the ‘re-organisation of the kitchen to make working conditions simpler’.39

The work and reports of both these women shed light on the overarching goals of the ICA. Butler, like Crowley, began her tenure with a reconnaissance mission, travelling in her case to Scandinavia and West Germany in order to study domestic conditions in other nations whose economies were based on agricultural exports. She noted that agricultural productivity there ‘was in direct proportion to a rise in the standard of home conditions’.40 Indeed, ‘[i]n other countries, where production is low on a farm, the Agricultural Advisor is not allowed to suggest outside improvements until the planning and amenities of the house have been looked into, beginning with the kitchen’.41 By contrast, Irish women suffered and were often forced to emigrate because:

[t]he quite common attitude of farmers of ‘what was good enough for my Mother is good enough for any woman coming into my house’ has confirmed many girls in their opinion that there is no hope of improved living conditions in rural Ireland, and so they often refuse to marry into what they consider primitive conditions.42

Evidence that numerous farm women echoed Butler’s dissatisfaction regarding domestic cooking and other household tasks is demonstrated by those women’s enthusiasm in attending lectures and requesting home visits. It is also suggested qualitatively, for example through the comments of the president of the Corofin, Co. Clare, Guild of the ICA, Proinseas, Bean Mhic Cafaid, who provided an account, in Margaret Crowley’s report, of a series of Crowley’s lectures attended by members of five guilds in March 1960. Pronouncing the lectures a great success, the president wrote:

Special attention was paid to kitchen planning and a receptive audience proved that they took all the points. Apart from the practical value of the lecture, I felt that it was a sound psychology to bring what are usually ones’ private domestic torments and irritations into the open and show that they can be beaten, or treated intelligently, as merely unescapable [sic] monotonies which can be relieved.43

An important outgrowth of concerns about the domestic foodscape that emanated from both Patrick Delany’s work and that of the ICA was a collaboration, beginning in 1955 and continuing into the 1960s, between the ICA and the RIAI (with Delany part of a three-person team representing the architectural institute) in which the ESB also participated.44 Its genesis was at the request of James Dillon, minister for agriculture, and the goal was to design a model farm kitchen that could be visited by anyone curious about rural housing improvements. The kitchen was to be constructed full-scale at the 1956 Spring Show, an annual event hosted by the Royal Dublin Society (RDS), routinely visited by thousands of people from across Ireland. The most remarkable characteristic of this farm kitchen was its blend of traditional and modern elements, no doubt an outcome derived from the experience and aspirations of all participating bodies. As the Homeplanning series suggests, Delany was already predisposed to taking an open approach to kitchen design subject to individual needs; one assumes that this helped to make him responsive to what was described in the Farmers’ Gazette as the ‘critical demand of the farmhouse wife as represented by the [ICA]’.45 Extant information suggests that the collaboration involved a give-and-take approach on both sides: ICA representatives requested modifications to certain design details initially laid down by the RIAI subcommittee, and at least some of these are evident in the final design.46 Compatibility is also implied in a letter of thanks that the honorary secretary of the ICA, Kathleen Delap, wrote to the president of the RIAI, in which she pronounced that ‘we could not have achieved such good results without such generous co-operation from the Architects’.47

The kitchen as built in 1957 is fascinating inasmuch as it reflects a deliberate hybridity that took into account and maintained key characteristics of vernacular domestic design, while striving to create an efficient and pleasant modern zone for food production.48 As the Farmers’ Gazette explained:

[a]ttention here has been paid not alone to work saving, but also to the saving the [sic] thousands of footsteps which is the burden that badly planned kitchens impose on the housewife. Hot and cold water are, of course, an essential feature, but the modernisation has not lost any of the comfort and charm of the good type country kitchen.49

A study of the kitchen design (see Pl. I) reveals elements of the modern that were to be expected at the time, many of which had been addressed by Delany in his Homeplanning series: fitted cabinets, taps for hot and cold running water, a large refrigerator and electrical appliances, including a cooker, a toaster and a kettle are included, while extensive fenestration is provided to complement the electric lighting, the latter consisting of at least one ceiling fixture as well as an additional fluorescent unit above the countertop that separated the cooking and eating areas. However, unlike Delany’s sample plan with its small, isolated kitchen, this one is open to an eating and leisure area and, as a report on the kitchen in the Irish Press both explained and illustrated (see Pl. II):

PL. I—Photo of model farm kitchen exhibit at the Spring Show of the Royal Dublin Society, 1957. Reproduced by permission of the Electricity Supply Board.

still retains the large open fire place which has now been fitted with a boiler grate which gives constant hot water. Even the old settle still remains in the corner and a large turf box is fitted beside the fire. The old and new are beautifully combined with the traditional furnishings by the I.C.A. and the modern electrical fitments by the E.S.B.50

The plan was conceived as a modification of a typical existing farm kitchen (and therefore 16 × 16 square feet in size) that could be retrofitted either by a builder or as a do-it-yourself project by a handy farmer. Architectural drawings of the design were also made available to interested parties for that purpose.51

PL. II—Photo of model farm kitchen exhibit reproduced in the Irish Press, May 1957. Reproduced by permission of the Electricity Supply Board.

The RDS farm kitchen was deemed a great success by many observers. The ESB estimated that if the number of leaflets that were made available at the kitchen was any indication of attendance by the public, then some 30,000 people visited the display.52 So well received was this initiative, in fact, that the decision was taken a year later to erect one, and, later, a second mobile version. These were designed to be collapsible and thus transportable on a trailer (see Pl. III showing the interior of one of the units). The mobile kitchens were almost exact replicas of the 1957 Spring Show design (and of each other), and were large enough to accommodate 40 visitors who could either explore the design on their own, or attend the lectures and demonstrations held by the ESB, the ICA or other instructors, usually in the evenings. Whereas the units were usually tended by ESB employees, both Butler and Crowley gave demonstrations in them, to enthusiastic audiences. The first model took to the road in March 1958, the second in August 1959, and they were still mobile through to November 1961 at least, having been displayed at some 150 venues throughout the towns and villages of Ireland.53 Accounts of visits from ICA members, and newspaper reports of the arrival of the mobile kitchen were consistently positive. The anticipated visit of the mobile kitchen to Castlebar, Co. Mayo, in September 1958 was deemed by the Connacht Telegraph to be ‘[o]f tremendous interest to all householders’.54 The Irish Independent gave the design a more detailed imprimatur: ‘[e]mbodying many of the essential items and geared to modern standards of efficiency, the kitchen, if even in part transferred to a farmhouse, would be a decided benefit to the housewife’. The popularity of the design was at least in part due to its blend of traditional and contemporary: ‘no matter what new gadgets are purchased, the housewife will be reluctant to part with her keepsakes. It is with this in mind that the travelling kitchen has been planned. A pleasant blending of old and new is embodied in the general aspect with pleasing results’.55 In 1960 the model farm kitchen was replaced, at the RDS Spring Show, by a full-scale all-electric house, the product of another collaboration principally between the ESB and, this time, An Foras Talúntais (The Agricultural Institute). Whereas the updated design was yet a further iteration of electrical and time-saving features embedded in what appeared to be a sleek modern bungalow, the connection between working zone and leisure zone, and the adjacent open hearth, were retained.56

PL. III—Photo of the interior of the mobile farm kitchen. Reproduced by permission of the Electricity Supply Board.

Food within the domestic foodscape of mid-twentieth-century rural Ireland

It is not the intention of this essay to track the implementation of modern kitchen design in mid-twentieth-century Ireland from the perspective of homeowners, or to elaborate on the individual homeowners’ reception of these models or indeed of modern cooking, except to say that the women who were interviewed by this author about their experiences in mid-twentieth-century Irish domestic space expressed enthusiasm about the convenience associated with the new paradigm—especially running water.57 Ethnographic evidence of this nature serves as confirmation of the efficacy of the ICA and others’ work to bring modern practices to the domestic foodscape in Ireland. Such findings are further supplemented and enriched by studies of the architecture itself and the interactions that took place within it, to gain a more complex understanding of how ‘progress’ unfolded in rural Ireland, and how that technological evolution was tempered and mediated by the vicissitudes of time and place. For example, it seems significant that the open fire, while no longer promoted as a site for cooking, remained an integral element of the kitchens proposed by the ESB/ RIAI/ICA collaboration. This reflected an anticipated reluctance of Irish household members to give up sensory-based or historically based experiences of comfort and pleasure, heat and light, disbursed throughout the work and leisure space of the hearth, as compared with the confined heat of a gas or electric cooker that is turned off when not in use (that residual Aga comes to mind here).58 A hesitation about sacrificing the gustatory qualities and indeed heritage value of open-hearth cooking seems also to be a factor for some.59 A profound example of such sentiments can be found in one segment of a weekly column called ‘Cooks’ causerie: By Clare’ that ran during the early 1950s in the Farmers’ Gazette. The author recounted a recent visit to the Wicklow Mountains, and an encounter with a man out hunting rabbit, and it set her into a reverie about what she would have liked to do with the meat:

I’d cook that rabbit and glory be but he’d taste good. I’d have to rake out the turf ashes until they were just nicely hot, then into the pot-oven I’d put the bacon cut in dice t’would sizzle and the smell would be exquisite. In with the rabbit cut in joints I’d poke the pieces around and about until they were all brown, then the little pinch of nutmeg, the salt and pepper and about two tablespoons of water, stir again and put the lid on. ‘Tis a young rabbit I’m cooking, so he won’t take long, half-an-hour—just time for me to wash and cook some new potatoes. Just when the potatoes are cooked and sizzling a minute in a little butter and chopped parsley I’ll take the lid off the pot-oven and add my cup of cream, another good stir and onto a hot dish with the lot . . . If I had a rabbit and a pot-oven I’d do all that. But I haven’t a pot-oven. No! Not any more. I’ve a brightly shining most modern and up-to-date electric cooker, one that would turn up its nose at a ‘black as night pot-oven,’ but I’ll tell you a secret, that cooker would be green with envy if it could only taste the bread baked in the ‘black as night pot-oven’ and if it could but smell the rabbit cooking away on the turf ashes. Ah, well, fair is fair. The electric monarch is a wonder for biscuits and as I’m very fond of biscuits I’ll make some[.]

Not only is the sense of taste engaged in this imagined performance, but those of sight (dicing the bacon), smell, touch (poking the pieces) and sound (sizzling). Nostalgia aside, coming back to present-day reality is still a worthwhile compromise for Clare, and recipes for Florentines and ‘Little Biscuits’ follow.60 Several months later, she invoked another touching replay of a traditional kitchen experience that demonstrated just how essential that space was as an anchor to country life. Especially in the early morning, she recounts,

when I come downstairs and open the door of my neat, spick-and-span kitchen with its gleaming cooker and its scarlet polished floor, I turn the page and look back to a country kitchen I remember years ago, and sometimes in the quiet of the early morning while the electric kettle boils I wink back a tear.

Clare attributes her present-day dismay to a kind of loneliness: ‘My kitchen of to-day is so quiet in the morning and I am so alone. My kitchen of the past was such a bustly [sic] place at 7 a.m.’, and she narrates the various activities of family members criss-crossing the space to undertake their various pursuits. The boiling kettle brings her back to reality, her ‘kitchen of the past melts into the morning sunshine and I hurry upstairs to call the family. All day long I’ll be a city dweller but at night and in the kitchen to-morrow morning I’ll have my dreams and I’ll slip to the country’.61

What other traits and characteristics can be discerned about food habits and precedents brought on by these inducements regarding modern kitchens? Clare herself included, in a number of her weekly columns, prompts to entice readers to try new or unfamiliar foods and techniques, including recipes such as ‘Chartreuse of Fish’ requiring tarragon vinegar and ‘Chilli’ vinegar, instructions on how to cook the frankfurters that appeared in the ‘delicatessen shop windows’ of the time, and a recipe for ‘Spaghetti in Tomato Sauce’, which she promoted as ‘a very nourishing and very cheap dish’.62 Irish ‘women’s’ magazines such as Model Housekeeping showed similar tendencies, by publishing for example, a conversion table of cooking temperatures for solid-fuel, electric and gas ovens (slow/moderate/hot to degrees Fahrenheit to regulo settings), and explaining what a marinade, and paprika, were to readers who sent in requests for such information.63 Articles in Homeplanning amongst other magazines explored nutritional and hygiene issues, thus locking both food selection and manipulation into the scientific paradigm that also underscored efficient kitchen design.64 Moreover, American and Continental recipes and cooking techniques proliferated, through publications by the ICA, columns such as Clare’s and in cookery books of the time.65

It certainly would be wrong, however, to assume that everyone switched over to modern methods during this period, that they could afford to or even wanted to do so. Nor should the pleasure or satisfaction gleaned by some women using traditional methods be ignored. When the distinguished folklorist Henry Glassie visited Ballymenone, Co. Fermanagh, in the 1970s to study that Northern Irish community, Ellen Cutler was still proudly cooking over a hearth fire, and joyfully exclaimed over the glorious taste of boiled cabbage ‘and it is boiled right’.66 Reluctance to change food tastes and methods stemmed from long-standing habits, reflected for example in the letter sent in to Woman’s Way by one frustrated woman whose husband refused to eat the vegetables she tried to serve him for the sake of good nutrition.67 That the cook of the house could not always unilaterally select the foods for consumption has been recognised by researchers in other areas, and so, inevitably, if incentives to new cooking and eating were to work, they had to be directed at men as well as women.68 Eleanor Butler knew this, and reported requests, ‘at almost every place’, for men-only demonstrations in the mobile kitchen, in the hopes that the males would be more receptive to their contents if they did not have their female relations present.69 The amazing Margaret Crowley knew this too. Even before she was hired by the ICA, in 1953 when teaching at the new vocational school in Banagher, Co. Offaly, she insisted on introducing the male students to cooking. She turned off the running water supply and insisted that they fetch water from the village well; they had weekly classes to learn to cook simple dishes; they were given a voice in planning the menu of the annual Christmas party for the school; and they helped to serve the foods that were prepared by the girls, for more than 80 guests. All the pupils dined, in rotation, in small groups with the teacher to learn proper manners, and they had a school kitchen garden to prove, as an article in the Irish Independent put it, ‘that there are other edible vegetables in Ireland besides cabbage, turnips and potatoes’.70

So mid-twentieth-century incentives to revise the Irish rural domestic foodscape propelled a movement toward a series of goals: a more comfortable and welcoming home that would help to inspire the young generation to stay on the farm; an efficient and hygienic kitchen, in keeping with the latest labour-saving designs emerging from America and elsewhere; a revitalised interest in the taste, nourishing qualities and varieties of foods; and, at the same time, a reappraisal of what was intrinsically Irish about the Irish domestic foodscape, particularly the abiding centrality of the open fire and its continuing capacity to radiate warmth, serve as a nucleus to household activity, and physically as well as symbolically anchor memories of past kitchens, meals and foods. Whereas most Irish kitchens today emerged from a linear progression built on this enthusiasm generated half a century or so ago, that crucially eliminated such physically arduous tasks as fetching water from a well, we know now that some of its promises could not be kept. Rather than precipitate a life of leisure and turn every Irish homemaker into Cinderella Hotfoot, such environments often increased the demands made on the woman of the house and the time she devoted to food-work, through expectations that she would become capable of more lavish homemade treats with all the assistance that new technology could provide—refrigerators, powerful new cookers, electric mixers and blenders, and so on.71 Convenience foods became a factor enabling women to pursue careers elsewhere, but the bean an ti remained the primary food caregiver in the household (the efforts of Margaret Crowley notwithstanding).

This essay on the domestic foodscape was intended to underscore the complexity inherent in cultural and technological transformation, complexity teased out by looking at the anything-but-mute architecture and material culture of the built environment of the home. That complexity certainly adds powerful resonance to the word ‘almost’ in a remarkable report on the arrival of the mobile kitchen to Rathdowney, in February 1960. The article in the Kilkenny People offered a decidedly international perspective in summing up local impressions:

Farmers returning from a fair on Monday and the Mart on Tuesday regaled their womenfolk with the wonders of the mobile all-electric farm kitchen [. . . .] Housewives turned up in big numbers to view with envious eyes the ideal layout, the gleaming paintwork, the built-in cupboards, and the numerous electrical appliances in this labour-saving model kitchen. From the general remarks heard at the exhibition one could almost conclude that modern Irish housewives agree with Carbusiers’ [sic] definition of a house as ‘a machine for living in’.72

Almost, but not quite.

* Author’s e-mail: rrk@concordia.ca

doi: 10.3318/PRIAC.2015.115.12

1 Research for this essay was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. I am grateful to Gerard Hampson, Pat Yeates and Brendan Delany of the Archive of the Electricity Supply Board for their expertise and for permission to access this collection, and to my research assistant Gabrielle Machnik-Kékesi for her enthusiastic and meticulous work on this project.

2 For a description and analysis of the domestic circumstances (particularly in terms of the absence of running water in most rural households of this time) that Irish rural women experienced during the 1950s, see Mary E. Daly, ‘“Turn on the tap”: the state, Irish women, and running water’, in Maryann Gialanella Valiulis and Mary O’Dowd (eds), Women and Irish history: essays in honour of Margaret MacCurtain (Dublin, 1997), 206–19. Low marriage rates and high rates of permanent celibacy are explored in Caitriona Clear, ‘“Too fond of going”: female emigration and change for women in Ireland, 1946–61’, in Dermot Keogh, Finbarr O’Shea and Carmel Quinlan (eds), The lost decade: Ireland in the 1950s (Cork, 2004), 135–46: 141–3.

3 Anonymous, ‘The adventures of Johnny Hotfoot, no. 2: the transformation of Cinderella’, REO News IV: 1 (December 1950), 14.

4 See, for example, Michael Shiel, The quiet revolution: the electrification of rural Ireland, 1946–76 (Dublin, 2003); and Maurice Manning and Moore McDowell, Electricity supply in Ireland: the history of the ESB (Dublin, 1984).

5 Seamus Heaney, ‘The sense of the past’, History Ireland 1:4 (winter 1993), 33–7: 33.

6 Shiel, The quiet revolution, 166.

7 See June Freeman, The making of the modern kitchen: a cultural history (Oxford, 2004); Klaus Spechtenhauser (ed.), The kitchen: life world, usage, perspectives (Basel, 2006 and 2013); and two special issues (issues 13:2 and 13:6) of Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography edited by Louise C. Johnson in 2006.

8 Indeed, the REO News was a monthly publication that reported on the progress of this countrywide project, primarily aimed at the Board’s own executive, technical and sales force.

9 For an introduction to such changes, see Rhona Richman Kenneally, ‘Cooking at the hearth: the “Irish cottage” and women’s lived experience’, in Oona Frawley (ed.), Memory Ireland (4 vols, Syracuse, NY, 2012), vol. 2, 224–41; and Rhona Richman Kenneally, ‘Tastes of home in mid-twentieth-century Ireland: food, design, and the refrigerator’, Food and Foodways 23:1–2 (2015), 1–24. To provide additional context, see Joanna Bourke, Husbandry to housewifery: women, economic change, and housework in Ireland, 1890–1914 (Oxford, 1993); and Caitriona Clear, Women of the house: women’s household work in Ireland, 1922–1961: discourses, experiences, memories (Dublin, 2000) as well as Social change and everyday life In Ireland, 1850–1922 (Manchester, 2007).

10 An Aga is a cooker that gives continuous heat for both cooking and the warming of rooms. Usually associated with solid-fuel energy (coal, anthracite or wood), it can now be fuelled by gas or electricity.

11 Examples of works that explore Irish spatiality and materiality include F. H. A. Aalen, Kevin Whelan and Matthew Stout (eds), Atlas of the Irish rural landscape (Toronto, Ont., 1997, second edition 2011); Gerry Smyth, Space and the Irish cultural imagination (London, 2001); Jim Hourihane (ed.), Engaging spaces: people, place and space from an Irish perspective (Dublin, 2003); Elizabeth FitzPatrick and James Kelly (eds), Domestic life in Ireland, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 111C (2011); and Vera Kreilkamp (ed.), Rural Ireland: the inside story (Boston, MA, 2012). Earlier, pioneering advocates were Kevin Danaher (Caoimhín Ó Danachair), E. Estyn Evans and Henry Glassie.

12 Karen Barad, Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning (Durham, NC, 2007), 180–1.

13 Branko Kolarevic, ‘Towards the performative in architecture,’ in Branko Kolarevic and Ali M. Malkawi (eds), Performative architecture: beyond instrumentality (New York, 2005), 204–13: 205.

14 See Gerry O’Hanlon, ‘Population change in the 1950s: a statistical review’, in Keogh, O’Shea and Quinlan (eds), The lost decade,72–9: 74. Diarmaid Ferriter has noted that historians of the period have used words like ‘“doom”, “drift”, “stagnation”, “crisis”, and “malaise” to describe Ireland south of the border in the 1950s’. Ferriter, The transformation of Ireland (New York, 2005), 62.

15 Enda Delaney, ‘The vanishing Irish? The exodus from Ireland in the 1950s’, in Keogh, O’Shea and Quinlan (eds), The lost decade, 80–6: 82–3.

16 O’Hanlon, ‘Population change’, 72.

17 Rosemary Cullen Owens, A social history of women in Ireland 1870–1970 (Dublin, 2005), 165, 323. For a wider sense of the position of the Irish Government on 1950s emigration see Mary E. Daly, The slow failure: population decline and independent Ireland, 1920–1973 (Madison, WI, 2006), especially 183–221.

18 Clear, ‘“Too fond of going”’, 135–46: 139.

19 Mary McCarthy, ‘The provision of rural local-authority housing and domestic space: a comparative North-South study, 1942–60’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 111C (2011), 287–309: 308.

20 Patrick Delany, ‘Rural housing: the vicious circle’, Homeplanning 1:3 (September 1953), 4–5: 4. Homeplanning was a monthly journal published by Harpers Ltd, College Green, Dublin. Its first issue appeared in July 1953, and it ran until at least April 1954.

21 Patrick Delany, ‘Rural housing: a final word’, Homeplanning 1:7 (January 1954), 4–5: 4.

22 Patrick Delany, ‘Planned kitchen’, Homeplanning 1:8 (February 1954), 4–5: 4.

23 Anon., ‘Our cover design’, Homeplanning 1:8 (February 1954), 5.

24 Patrick Delany, ‘Planned kitchen’, Homeplanning 1:9 (March 1954), 4–5: 4. For a discussion of prescriptives targeting kitchen efficiency see, for example, Ellen Lupton and J. Abbott Miller, The bathroom, the kitchen, and the aesthetics of waste (Princeton, NJ, 1992).

25 Patrick Delany, ‘Planned kitchen’, Homeplanning 1:10 (April 1954), 4–5.

26 The ICA, a non-sectarian association of women, was established in 1910. It operated at the local level through guilds of members in towns and villages; these were clustered into federations at the county level and administered nationally from Dublin. For further information see, for example, Patrick Bolger (ed.), And see her beauty shining there: the story of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (Dublin, 1986), and Aileen Heverin, The Irish Countrywomen’s Association: a history 1910–2000 (Dublin, 2000).

27 Daly, ‘“Turn on the tap”’, 207. For further information regarding the role of the ICA (and the ESB) in promoting piped-in water see Shiel, The quiet revolution, 194–212 and Heverin, The ICA: a history, 105–14.

28 Anon, ‘Grianan committee report’, Farmers’ Gazette CXII:15 (10 April 1954), 407–08: 408.

29 Anon, ‘Grianan committee report’, 408.

30 National Library of Ireland (NLI), MS 39,876/8, Esther Bishop, Typescript report of the work of the Grant Counterpart Fund Committee of the ICA entitled ‘Better living’, 1962, 1.

31 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Bishop, ‘Better living’, 1962, 2.

32 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Bishop, ‘Better living’, 1962, 4.

33 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Report of Miss Butler, ‘Better living’, 1962, 30.

34 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Butler, ‘Better living’, 1962, 29–30.

35 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Butler, ‘Better living’, 1962, 19.

36 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Bishop, ‘Better living’, 1962, 5.

37 Recognition of the significance of comfort and aesthetics within Irish domestic space can be noted as early as the turn of the twentieth century, in The Irish Homestead, the publication of the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society. See James MacPherson, ‘“Ireland begins in the home”: women, Irish national identity, and the domestic sphere in the Irish Homestead, 1896–1912’, Éire-Ireland 36:3–4 (2001), 131–52: 138–42.

38 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Bishop, ‘Better living’, 1962, 7.

39 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Report of Miss Margaret Crowley, ‘Better living’, 1962, 120, 123.

40 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Butler, ‘Better living’, 1962, 21.

41 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Butler, ‘Better living’, 1962, 32.

42 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Butler, ‘Better living’, 1962, 32.

43 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Cited in Crowley, ‘Better living’, 1962, 93.

44 Irish Architectural Archive (IAA), Basement E2, Irish Countrywomen’s Association Kitchen Exhibition 1956, Wilfrid Cantwell (honorary secretary of the RIAI) to Francis J. Barry and Patrick M. Delany, 3 August 1955.

45 ‘A modern farmyard at the Spring Show: plenty of ideas for electrification’, Farmers’ Gazette CXV:18 (4 May 1957), 494.

46 Examples of adjustments to the design made on the recommendation of the ICA are the inclusion of two windows on the north wall of the kitchen and the location of the cooker to the left of the sink. IAA, Basement E2, ICA kitchen exhibition 1956, Kathleen A. Delap (honorary secretary of the ICA) to Wilfrid Cantwell, 31 October 1955.

47 IAA, Basement E2, ICA kitchen exhibition 1956, letter from Kathleen Delap to the President of the RIAI, 14 May 1956.

48 The 1956 RDS farm kitchen was the same design as that which was erected a year later (for which substantial documentation remains): this is indicated in an ICA memorandum: see NLI, MS 39,877/3 b, ICA memorandum to the Department of Agriculture, 16 July 1957, 3.

49 ‘A modern farmyard at the Spring Show’, 494.

50 RK, ‘All electric farm kitchen’, Irish Press, 8 May 1957, 3.

51 RK, ‘All electric farm kitchen’, 3.

52 ‘News items’, REO News X:6 (May 1957), 13.

53 ‘A mobile farm kitchen’, REO News XI:4 (March 1958), 4–5; ‘ESB mobile kitchen’ on the Irish Countrywomen’s Association page, Farmers’ Gazette CXIX:47 (25 November 1961), 18. Dates and places of mobile kitchen venues were tracked through Farmers’ Gazette reports, and ICA and ESB documentation. The ideal kitchens displayed at the RDS and their mobile counterparts are the subjects of a future monograph by the author.

54 ‘All-electric exhibition kitchen in Castlebar’, Connacht Telegraph, 13 September 1958, 2.

55 ‘Mobile modern farm kitchen’, Irish Independent, 19 February 1958, 4. The article also noted the aesthetic qualities of the unit, which is described as having ‘delicately off-white walls, with blue flooring’ in order to ‘dispense with the usual dark interior and make the kitchen bright and airy’.

56 ‘Spring Show—1960’, REO News XIII:6 (May 1960), 2. The architect on this project was P. J. Tuite. See ESB, ‘Better living for the farm family’ [1960].

57 These interviews and conversations took place between 2010 and 2014, in counties Cork, Clare, Galway and Kilkenny.

58 Eleanor Butler confirms this in her rationale for keeping the open fire in the 1957 RDS kitchen design: ‘This adaptation of an old kitchen allowed for the continued use of the open fire which forms the focal point of rural home life, but extending its use beyond that of conversation [by adding a system to heat water]’. NLI, MS 39,876/8, Butler, ‘Better living’, 1962, 22.

59 For an analysis of a fictional account of the significance of traditional cooking methods see Rhona Richman Kenneally, ‘The elusive landscape of history: food and empowerment in Sebastian Barry’s Annie Dunne’, in Máirtin Mac Con Iomaire and Eamon Maher (eds), ‘Tickling the palate’: gastronomy in Irish literature and culture (Oxford, 2014), 79–98.

60 Clare [surname unknown], ‘Cooks’ causerie: By Clare’, Farmers’ Gazette CXI:22 (30 May 1953), 658.

61 Clare, ‘Cooks’ causerie’, Farmers’ Gazette CXII:7 (13 February 1954), 174. Similar linkages of cooking proficiency acquired in a traditional kitchen with the skills necessary in a modern kitchen appear in the introductions to cookbooks by Maura Laverty and Theodora FitzGibbon, written in the 1950s and 1960s. See Richman Kenneally, ‘Cooking at the hearth’, 236–7.

62 Clare, ‘Cooks’ causerie’, Farmers’ Gazette CXI:1 (3 January 1953), 22; CXI:12 (21 March 1953), 318; and CXI:43 (24 October 1953), 1226.

63 The conversion chart and question about paprika appear in the anonymous ‘My cookery postbag’, Model Housekeeping (February 1952), 255; the request about marinades is in the April 1952 ‘My cookery postbag’, 379.

64 Regarding nutritional issues see Mary de R. Swanton, ‘Your kitchen: the foods you really need’, Homeplanning 1:7 (January 1954), 9. She addressed hygiene a month later in ‘Your kitchen: waste not food want not food’, Homeplanning 1:8 (February 1954), 9.

65 See, for example, the Danish ‘Foreign recipes’ on the ICA page of the Farmers’ Gazette CXI:16 (18 April 1953), 423; American tart, in Clare, ‘Cooks’ causerie’, Farmers’ Gazette CXI:41 (10 October 1953), 1,178, and a chapter on American-inspired convenience foods in Maura Laverty, Maura Laverty’s cookbook (New York and Toronto, Ont., 1947), 117–23.

66 Henry Glassie, Passing the time in Ballymenone: culture and history of an Ulster community (Philadelphia, PA, 1982), 445.

67 Maura Laverty, ‘Maura Laverty’s letters page’, Woman’s Way (15 May 1963), 58.

68 See Wm. Alex McIntosh and Mary Zey, ‘Women as gatekeepers of food consumption: a sociological critique’, in Carole Counihan and Steven L. Kaplan (eds), Food and gender: identity and power (Amsterdam, 1998), 125–44.

69 NLI, MS 39,876/8, Butler, ‘Better living’, 1962, 23.

70 IM, ‘Answer to your questions’, Irish Independent, 15 February 1958, 9.

71 See Ruth Schwartz Cowan, More work for mother: the ironies of household technology from the open hearth to the microwave (New York, 1985).

72 Anon., ‘All-electric kitchen’, Kilkenny People, 13 February 1960, 8. The reference is to Le Corbusier, the famed modernist architect who did indeed argue that the house is ‘a machine for living in’. This idea was captured in his book Vers une architecture (Paris, 1923), commonly known in English as Towards a new architecture.