Haute cuisine restaurants in nineteenth and twentieth century Ireland

School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology, Dublin Institute of Technology, Cathal Brugha Street, Dublin 1

[Accepted 13 October 2014. Published 13 March 2015.]

Abstract

Historically, Ireland has not been associated with dining excellence. However, in 2011, the editor of Le Guide du Routard, Pierre Josse, noted that the Irish dining experience was as good, if not better, than anywhere in the world. This was a signal achievement for, as Josse also observed the disastrous nature of Irish public dining thirty years ago, when they first started the Irish edition. Thus it may come as a surprise to many that Ireland had a previous ‘golden age’ of haute cuisine—the benchmark for which was set by Restaurant Jammet which traded in Dublin between 1901 and 1967. Indeed, Ireland experienced an influx of gastro-tourists during ‘the Emergency’ (1939–45), and in the 1950s, The Russell Restaurant joined Restaurant Jammet as one of the most outstanding restaurants in Europe. In addition, both Dublin and Shannon airports housed two of Ireland’s finest restaurants in the early 1960s. Cashel, Co. Tipperary, had two Michelin-starred restaurants during the early 1980s. From 1975 to 1988 Cork was the centre of fine dining in Ireland. The opening of Roscoffs in Belfast in 1989 spawned a cluster of Michelin-starred restaurants in Northern Ireland. Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud in Dublin was awarded its first Michelin star also in 1989, signalling a rebirth of fine-dining restaurants in the capital. This paper will discuss the history of Ireland’s haute cuisine restaurants, identifying the various phases that led to our current standing: equal to if not better than any global competitors.

Introduction

Historically, Ireland has not been associated with dining excellence. However, in 2011, the editor of Le Guide du Routard, Pierre Josse, noted that ‘the Irish dining experience is now as good, if not better, than anywhere in the world’. This was a signal achievement for, as Josse also observed, ‘thirty years ago, when we first started the Irish edition, the food here was a disaster’.1 This paper begins with a brief outline of the development of French haute cuisine and the emergence of restaurants in Paris. Its main focus is to track the emergence and development of haute cuisine restaurants in Ireland which began in the second half of the nineteenth century. The influence of foreign-born chefs and restaurateurs will be discussed drawing on evidence from trade directories, advertisements, oral histories, material culture and the 1901 and 1911 Censuses.

Key players such as the Jammet family will be profiled and a little-known ‘golden age’ of haute cuisine (1949–74) centred on Dublin will be discussed.2 Dublin was home to two of the most outstanding restaurants in Europe during this period.3 From 1975–88 Cork emerged as the new ‘gourmet capital’ as the focus of fine dining shifted from Dublin to country house hotels such as Arbutus Lodge and Ballymaloe House. The arrival of the Egon Ronay guide in 1963 and the Michelin guide in 1974 allows for patterns in Ireland to be compared with Great Britain and Europe. From the 1960s, a number of trends and culinary movements challenged the Georges Auguste Escoffier orthodoxy which had pervaded since the Edwardian era. Irish haute cuisine restaurants negotiated yet never fully embraced trends such as nouvelle cuisine, fusion cuisine and molecular gastronomy in order to arrive at a new ‘golden age’ (1994–2014) when the Irish dining experience was described in 2011 by the editor of Le Guide du Routard as being ‘as good if not better, than anywhere in the world’.4

Origins and spread of French haute cuisine

French haute cuisine originated in the large kitchens of the aristocracy during the seventeenth century, and the pattern spread from there in the eighteenth century to the kitchens of wealthy households across the European continent. It is noteworthy that in most of Europe, up until the development of restaurants, food served in public premises was less spectacular than the fare available in the houses of the wealthy. This was the pattern also in Dublin where the restaurant was preceded by taverns, coffee houses and clubs.5

Haute cuisine has experienced a number of paradigm shifts since its inception. This paper uses the term to cover the evolving styles of elite cuisine produced and served in restaurants by professional staff spanning the Escoffier orthodoxy of the early twentieth century through the ‘nouvelle cuisine’ movement of the 1970s and 1980s, to the ‘molecular gastronomy’ or ‘modernist’ movement of the early twenty-first century. French haute cuisine in the public realm can be said to have originated in Paris with the appearance of restaurants during the second half of the eighteenth century. This phenomenon was greatly boosted during the French Revolution when the number of restaurants increased dramatically.6 Restaurants have been differentiated from a tavern, inn or a table d’hôte by a number of factors. Firstly, they provided private tables for customers; secondly, they offered a choice of individually priced dishes in the form of a carte or bill of fare; and thirdly, they offered food at times that suited the customer, not at one fixed time as in the case of the table d’hôte?7 The spread of restaurants from Paris to London, Belfast and Dublin was slow, due primarily to the abundance of gentlemen’s clubs which siphoned off much of the prospective clientele for restaurants in these cities.8 A number of factors helped to create a more congenial environment for the opening of restaurants in both Ireland and England in the second half of the nineteenth century. They include the widespread adoption of service à la Russe, and the introduction of the Refreshment Houses and Wine Licences (Ireland) Act 1860.9 Service à la Francaise was the method of service practised at the aristocratic upper end of French and other European cuisine from medieval times until the mid-nineteenth century in which food was served not in courses as it is now, but in services. Each service could comprise a choice of dishes from which each guest could select what appealed to him or her most. The service subordinated flavour and the enjoyment of food to making an impression of wealth and power. Service à la Russe replaced service à la Française in Britain and elsewhere in Europe in the course of the nineteenth century. This new style of table service provided for dishes being served to guests at their seats by servants who handed them round. The meal was served in courses starting with hors d’oeuvres, soup, fish, entrée, etc. and required more servants, and also table decorations to fill the spaces which the dishes themselves would have occupied under the old system.

Restaurants such as the Café Royal in London and The Burlington in Dublin, which both opened in the 1860s, were male bastions. Separate ladies rooms appeared in certain restaurants during the final decades of the nineteenth century but it was not until French chef Georges Auguste Escoffier (1846–1935) and Swiss hotelier César Ritz (1850–1918) developed the Savoy Hotel dining room in London in 1890 that it became acceptable and fashionable for genteel ladies to dine out publicly in mixed company.

The emergence of restaurants in Ireland

The first specific evidence of a French restaurant serving haute cuisine in Ireland is provided by an advertisement in the Irish Times for the Cafe de Paris, Lincoln Place, Dublin, in 1861. Establishments using the term ‘restaurant’ became common in the second half of the nineteenth century but the term was not used by Thom’s directory until 1909 in which the category ‘Restaurants and Tea Rooms’ was first listed. There is one listing for the Imperial Hotel Restaurant, Donegall Place, Belfast, in Henderson’s directory for 1846–7, and The Belfast directory for 1887 lists fourteen establishments under the heading ‘Restaurants’ although only three use the word restaurant in their title.10 Over 26 different Dublin-based restaurants advertised in the Irish Times between 1865 and 1900, which notices included an advertisement announcing the opening of a ‘High-Class Vegetarian Restaurant’ at 3 and 4 College Street.11 There was also a vegetarian restaurant in Belfast at this time and in 1908 an ‘Indian Restaurant and Tea Rooms’ opened in Dublin predating by three years the first twentieth-century Indian restaurant in London.12 The establishment of The Hotel and Restaurant Proprietors’ Association of Ireland (1890) also predates its English equivalent by a number of years.13 The Irish Tourist Association was established in 1893 by F. W. Crossley, the Irish manager of Thomas Cook and Sons in order to develop Ireland as a tourist destination.14 Growth in tourism, enabled by the expansion of railways, assisted the emergence of the hospitality sector by providing more customers for restaurants and hotels. One English-born chef, G. Frederick Macro, is given credit by The Chef in 1896 ‘for the part he has taken in raising the status of Irish hotels in the estimation of the English public’.15 Macro trained in Paris and later at the Russian Embassy in London. He travelled widely prior to becoming chef at the newly opened Grand Hotel in Belfast in the 1890s and taking the position of chef de cuisine at the Imperial Hotel in Cork. The twelve-course Christmas dinner that he served in Cork in 1897 (Fig. 1) is a good example of service à la Russe and of Escoffier-style French haute cuisine with the accompanying wines.16

FIG. 1—Christmas Menu, 1897, from G. Frederic Macro, Imperial Hotel, Cork. (Source: The Chef and Connoisseur, 18 December 1897.)

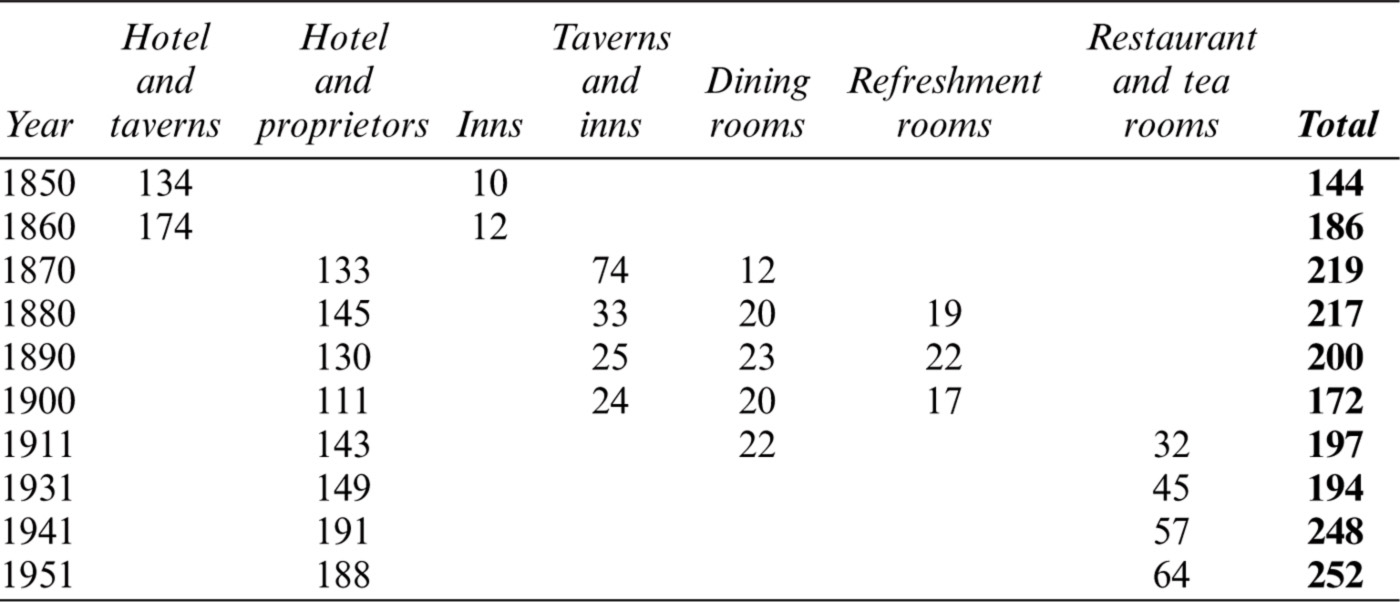

Trade directories such as Thom’s, Guy’s and the Belfast and Ulster directory give listings but the fact that catering premises are listed under different headings makes direct comparison between cities difficult (Table 1).17 Despite possessing a smaller population than Belfast, Dublin’s position as the focal point for the elite who ruled the country from Dublin Castle meant that it possessed a higher proportion than the former of haute cuisine restaurants by the early twentieth century.18 The 1901 and 1911 Censuses indicate that Dublin, Belfast and Cork were the urban centres with the largest number of restaurants and that smaller clusters were to be found in Killarney (Co. Kerry), Limerick, Londonderry, Waterford and Galway.19 Of the 24 establishments listed under ‘Restaurant, Tea, Luncheon and Dining Rooms’ in Cork for 1910, only two (The Mall, Tivoli) use the word restaurant, although an advertisement appears for Leech’s Hotel and Restaurant on a separate page. Also listed is the famous Oyster Tavern and Dining Rooms in Market Lane.20 Cross-referencing Guy’s with the 1911 Census shows a German manager, Henry J. Koenigs, in the Great Southern Hotel in Killarney, and reveals an Austrian assistant manager, Italian chef, and both Austrian and German waiters. It also reveals an English manager in the Imperial Hotel in Cork with Swiss, German and French chefs listed as ‘Hotel Cook’, and waiters from Austria and Germany. For much of the twentieth century, haute cuisine restaurants were associated with grand hotels.21

TABLE 1—Dublin food dining premises listed in Thom’s directory 1850–1951. (Source: Thom’s directory (Dublin, 1850–1951).)

Data from census reports

The 1911 Census shows that the leading chefs, waiters and restaurateurs in Dublin during the first decades of the twentieth century were predominantly foreign-born. Most had trained in the leading restaurants, hotels and clubs of Europe.22 On the assumption that foreign chefs and waiters are potential indicators of haute cuisine in Irish restaurants, a thorough search was made of the 1901 and 1911 Censuses. Of the 89 chefs listed in the 1901 Census, nearly half were foreign-born. The main countries of origin were England (14), France (9), Switzerland (9), Germany (7), Scotland (3), and one each from Austria and Holland. The 1911 Census lists 168 chefs more than half of whom were foreign-born. They came from England (33), France (18), Switzerland (12), Germany (8), Scotland (6), Italy (4), and one each from India, Belgium, Malta and Jersey. Within Ireland in 1911, Dublin was the birthplace of 37 chefs; 8 chefs were born in both Cork and Belfast, and the remainder were born elsewhere in the country. The keyword ‘waiter’ yielded 1,106 results in the 1901 Census and 1,200 results in the 1911 Census. The foreign-born waiters in 1901 came from England (111), Germany (49), Scotland (14), Austria (12), and Switzerland (5). In 1911 the foreign-born waiters came from England (137), Germany (37), Austria (26), Scotland (29) and France (6).

Gender is another method of differentiating haute cuisine restaurants from other restaurants, particularly in the first half of the twentieth century. Searching the 1901 and 1911 Censuses using ‘restaurant’ as a keyword revealed 195 and 211 results, respectively, but this masked a broad array of employment categories. These embraced restaurant proprietor, keeper, manager and cook, waitress and porter. The vast majority were female as most restaurants at the lower level of the market, as opposed to haute cuisine restaurants, were owned, managed or run by Irish women. Similarly, a search for ‘café’ revealed 58 entries, the majority of which embraced female café attendants, managers, superintendents, waitress or assistants. In 1901 there were 531 waitresses listed in Ireland; this had risen to 821 by 1911.23 The word ‘cook’ was associated more with women, and when associated with men it was usually in the context of ship’s cooks or army cooks. Indicatively, only 561 of the 15,878 cooks listed in the 1901 Census, and only 635 of 14,592 listed in the 1911 Census were male.

Influence of foreign chefs/ restaurateurs

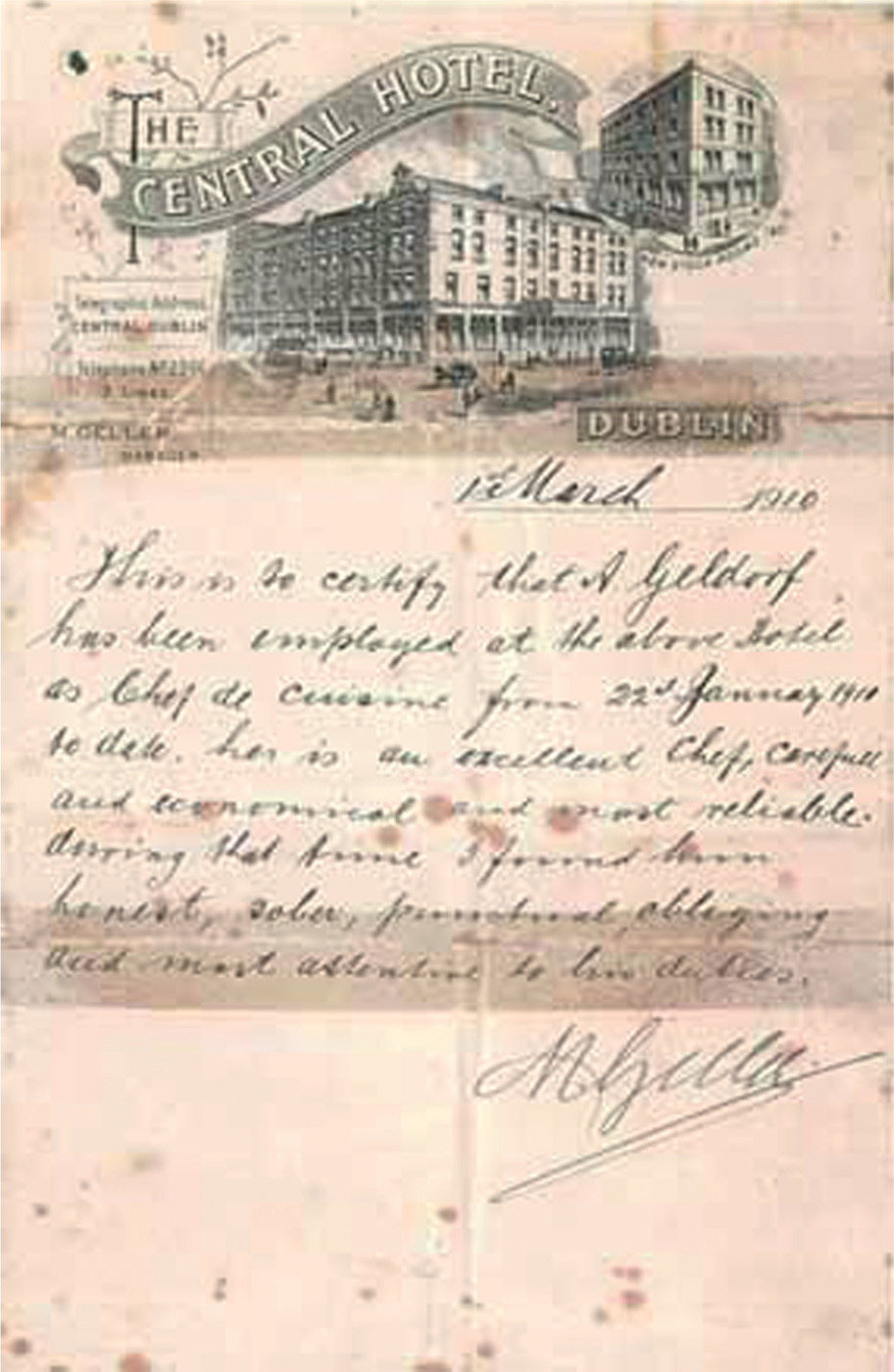

Haute cuisine was advertised as being available in the dining rooms of the best hotels in Dublin (Gresham, Shelbourne, Metropole and Royal Hibernian), Belfast (Royal Avenue, Grand Central and Midland), Cork (Imperial, Metropole and Victoria) and elsewhere in the country (Slieve Donard, Co. Down, and Great Southern, Killarney) in the first half of the twentieth century. These premises, along with select restaurants, were the preferred workplaces of immigrant chefs and waiters. The 1911 Census return for 47 Royal Avenue, Belfast (Avenue Hotel) is illustrative. It reveals an American, Ernest Everest, as head of the family (hotel manager) living with his English wife (hotel manageress), and 20 staff which embraced hotel waiters from Germany, Bohemia, Austria and France, and a night porter from Switzerland.24 The Grand Central Hotel, 9 Royal Avenue, Belfast, had an English manager, a Swiss pastry chef and an Italian second chef. Head chefs and senior chefs often did not live-in which complicates issues. Triangulating with other sources (newspaper reports, advertisements and material culture) reveals patterns of movement throughout the country. For example, M. Geller who wrote a reference for the Belgian chef, Zenon Geldof, before resigning as manager of the Central Hotel in Dublin (Fig. 2) in 1910, re-emerges as Martin Geller, the German-born hotel manager in 16 Donegall Place, Belfast, where he oversaw 20 live-in staff which included a German chef, and waiters from Germany and Switzerland. The 1901 Census lists Geller as ‘Hotel Proprietor’ on Main Street, Cavan Town, with six live-in staff (all Irish-born). Sources such as directories and the census can provide the answers to the who, where, and when questions, but it requires associated information from oral histories, interviews and obituaries to reveal the how and why?25

Along with the Jammet brothers, other European families, such as the Geldofs, Oppermanns, Gygaxs, and Bessons, were influential in developing the restaurant business in Ireland.26 Paul Besson came to Dublin from the Hotel Cecil, London, in 1905 to serve as manager of The Royal Hibernian Hotel on Dawson Street. Over a number of decades, Paul Besson, his son Kenneth and other members of his family took control of The Royal Hibernian Hotel, The Russell Hotel, The Bailey Restaurant in Dublin and the Old Conna Hill Hotel in Wicklow.27

The most notable foreign chefs were the Jammet brothers. Michel (1858–1931) and François (1853–1940) Jammet were born in St Julia de Bec, near Quillan, in the French Pyrenees. Michel first came to Dublin in 1887 as chef to Henry Roe, the distiller. Following four years working in London for George Henry, sixth earl Cadogan, he returned to Dublin in 1895, becoming head chef at the Vice-regal Lodge when Cadogan became Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.28 In 1888 François became head chef of the Café de Deux Mondes, rue de La Paix, Paris; he subsequently moved to the Boeuf à la Mode, Rue de Valois, Palais Royal, where he married the owner’s daughter, Eugenie. In 1900 Michel and François Jammet bought the Burlington Restaurant and Oyster Saloons at 27 St Andrew Street, Dublin, from Tom Corless. They refitted, and renamed it The Jammet Hotel and Restaurant in 1901, and it became preeminent among the restaurants of Dublin. Its clientele included leading politicians, nobility, actors, writers and artists. These included Harry Kernoff, whose painting of the restaurant (Pl. I) now hangs in Dublin’s Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud. Jammet’s Hotel and Restaurant traded at 26–27 Andrew Street and 6 Church Lane until the lease reverted to the Hibernian Bank in 1926. Michel Jammet acquired Kidd’s Empire Restaurant and Tea Rooms at 45–46 Nassau Street at this time and brought some of the fittings from the original premises. When he retired in 1927, his son Louis took over the running of the business while Michel returned to Paris where he was a director and the principal shareholder of the Hotel Bristol until his death in 1931.The new Restaurant Jammet on Nassau Street traded successfully from 1927 until its closure in 1967. It became the haunt of artists and the literary set, and the Jammet’s took pride in the fact that it was Dublin’s only French restaurant.29

FIG. 2—Reference for Zenon Geldof, March 1910, signed M. Geller. (Source: Geldof Family Private Collection.)

PL. I—The Jammet Hotel and Restaurant (Andrew Street) by Harry Kernoff. (Source: Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud—The Merrion Hotel, Dublin.)

The interwar years and the ‘Emergency’

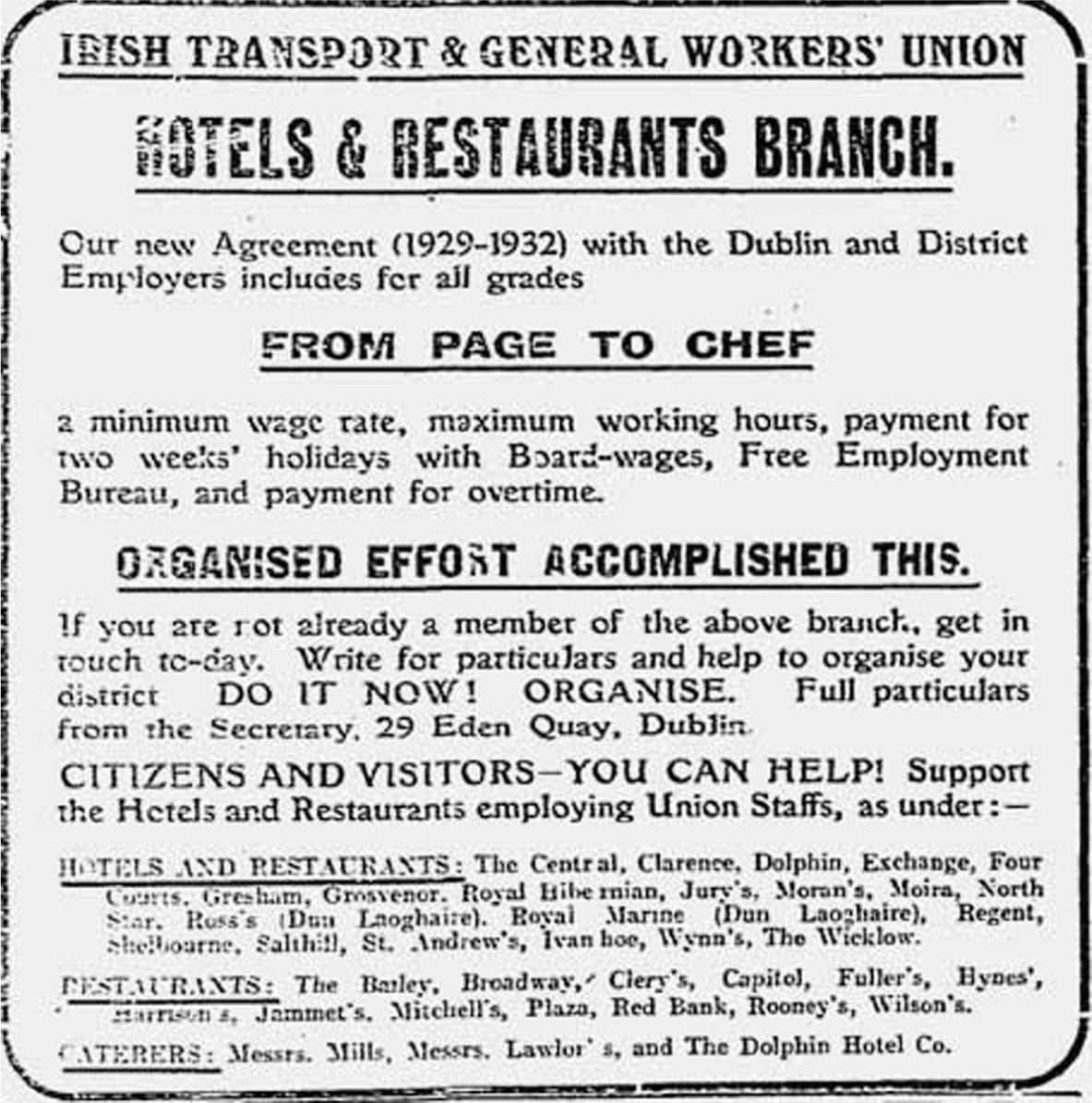

During the interwar years, growth in the restaurant sector in Dublin took the form primarily of large-scale dining rooms similar to those of the Lyons Group in London. An advertisement for Clery’s Restaurant in January 1928 claimed that it was ‘The Largest and Most Popular Restaurant in Ireland’.30 In November 1928 The Plaza Restaurant opened on Middle Abbey Street with six French chefs, with the capacity to serve between 600 and 1,000 diners at one time.31 The Plaza was managed by Zenon Geldof, a Belgian chef and confectioner who owned the Cafe Belge on Dame Street and the Patisserie Belge on Leinster Street. An advertisement for The Plaza in 1929 pronounced that it was ‘The Largest and Most Luxurious Restaurant in Ireland’.32 If so, it soon encountered difficulties and may have closed as in October 1929 it was advertised as a roller-skating rink though the Irish Times carried an advertisement in January 1930 of the reopening of the Plaza Restaurant.33 By 1934 foreign visitors were becoming noticeably more numerous in Dublin. The Red Bank Restaurant’s Ernest J. Hess belonged to the new school of maître d’hôtel; ‘keen, alert, of cosmopolitan outlook, and fluent linguist’, he was ideally adapted to welcoming these visitors from different countries.34 Large restaurants were also attached to theatres and cinemas such as the Savoy, Metropole and Capitol.35 The Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) had a hotels and restaurants branch which was active at this period and had members in most of the leading establishments (Fig. 3).

The Belfast and Ulster directory of 1924 lists 32 restaurants in Belfast. This publication also carried a full-page advertisement for Thompsons (Belfast) Ltd. Located at 14 Donegall Place, established in 1847, it was heralded as the ‘Premier Restaurant in Belfast’.36 There appears to have been a cluster of restaurants on Donegall Place (Carlton, Shaftsbury Tea Rooms, The Savoy), with the Grand Metropole Hotel on Donegall Street. The onset of the Second World War must have affected business in Belfast restaurants but the Belfast Blitz by the Luftwaffe in April and May 1941 was catastrophic. In neutral Dublin, restaurants thrived during the ‘Emergency’ and indeed for a number of years later as diners crossed the border or came over from England to enjoy a solid meal.37 John Ryan recalled that a customer described the ‘fabulous’ fare available in Jammet’s as ‘the finest French cooking between the fall of France and the Liberation of Paris’.38 American servicemen, according to Ryan ‘cigar chomping and in full uniform’, streamed across the border to sample the quality food in the prodigious quantities that it was available here. Tony Sweeney recalled Jammet’s ‘packed with military people during the war’. Garret Fitzgerald remembered American soldiers coming to Dublin as late as 1949 but did not recall them in uniform. Jimmy Kilbride noted that The Gresham Hotel, Dublin, had no shortage of food thanks to the black market activities of its manager Toddy O’ Sullivan. When in 1943 the Daily Express published one of the Gresham’s extensive à la carte menus on its front page, to illustrate how neutral Ireland was not suffering from the effects of war, it unintentionally increased the numbers of off-duty servicemen who dined at the Gresham.39 Such was the Gresham’s reputation that Eleanor Roosevelt once turned up unexpectedly with an entourage of ten airmen.40

FIG. 3—Advertisement for the Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union, Hotels and Restaurants Branch. (Source: Irish Times, 8 August 1929, 7.)

Over many years, Restaurant Jammet maintained its position as the finest restaurant producing haute cuisine in Ireland. Until the appointment of Pierre Rolland as head chef of The Russell in 1949, Jammet’s was also ‘the only restaurant in Dublin with an international reputation’. Indeed, according to Journal l’Epoque in June 1947, Jammet’s was the only place in the British Isles where one could eat well in the grand French tradition, ‘À Dublin, . . . on trouve une cuisine digne de la grande tradition française’.41

A golden age of haute cuisine in Dublin

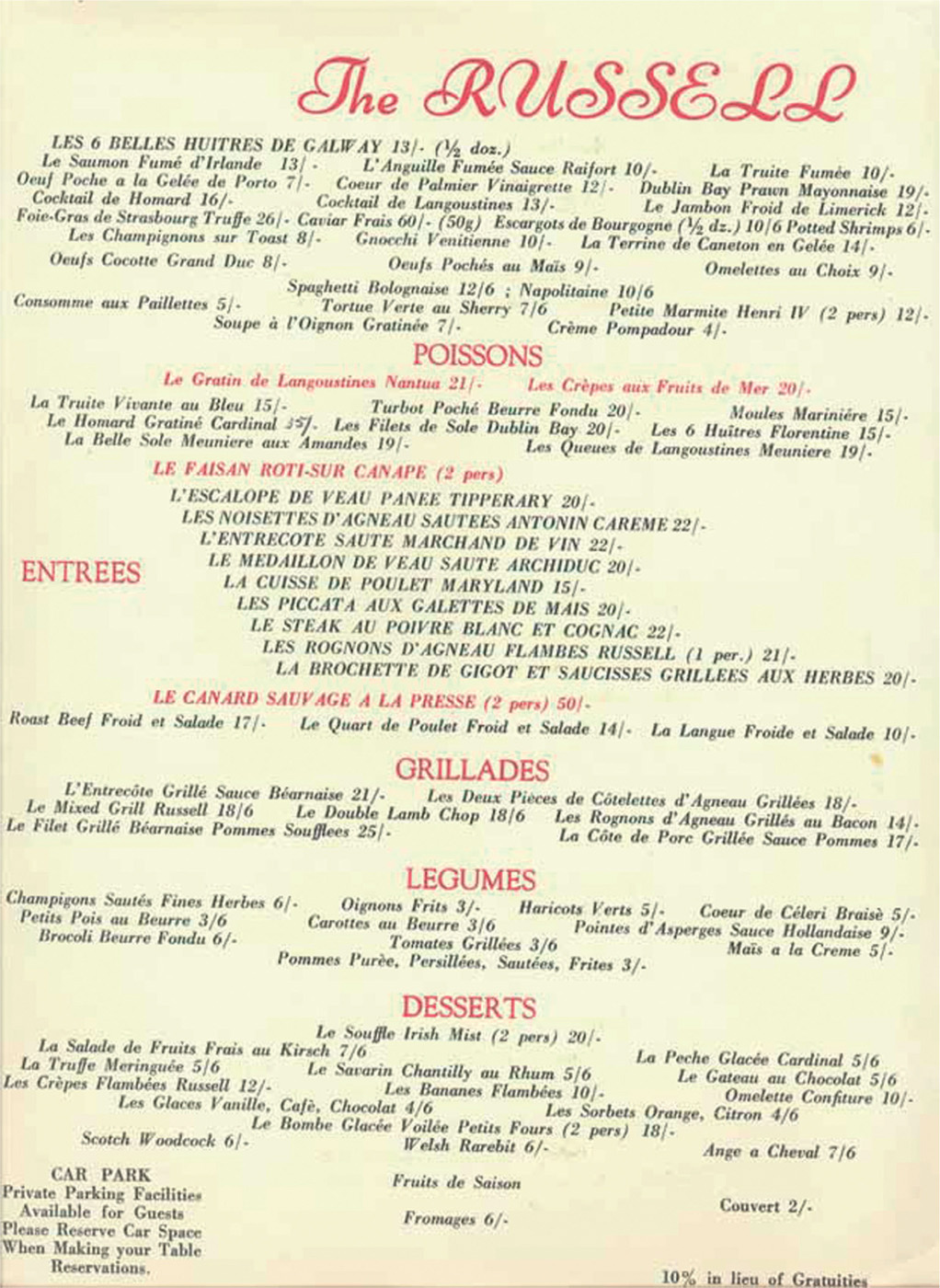

The 1949–74 period can be viewed as a golden age’ of haute cuisine in Dublin, since more award-winning world-class restaurants traded in Dublin during this period than at any previous time. In the late 1940s, The Red Bank Restaurant reopened as a fine-dining restaurant with a French head chef producing haute cuisine. Newspaper reports of gastronomic dinners held by the Irish branch of Andre L. Simon’s Food and Wine Society attest to the growing interest in haute cuisine at this time. Both The Russell Restaurant and Restaurant Jammet received awards from the American magazine Holiday in the 1950s for being ‘outstanding restaurants in Europe’.42 Further evidence of Dublin restaurants’ as culinary leaders is provided by the Egon Ronay guide which first covered Ireland in 1963. By 1965 Ronay suggested that The Russell Restaurant must rank amongst the best in the world’.43 A menu from The Russell in 1966 is shown in Figure 4, and it is notable that when Rolland left full-time employment in The Russell in 1966 to work winters in the Bahamas, the restaurant dropped to two Egon Ronay stars in 1967. The majority of the award-winning Dublin restaurants produced a form of haute cuisine that had been codified by Escoffier; it was labour-intensive and it was silver-served by large teams of waiters in elegant dining rooms.

The beginnings of expertise transfer to Irish chefs can be dated to the early 1950s when an agreement between Ken Besson and the ITGWU allowed foreign-born chefs and waiters to work in Ireland in return for Irish apprentices being indentured in the Besson-owned Russell and Royal Hibernian Hotels under the guidance of chefs Pierre Rolland and Roger Noblet.44 The Irish Hotelier described Rolland as numbered among the ten most distinguished culinary experts in France’.45 Under his leadership, The Russell Hotel kitchen became a training ground for generations of Irish chefs (Pl. II). The number of foreign chefs and waiters working in Ireland fell during the late 1950s and early 1960s. They were replaced by foreign-trained Irish chefs and waiters. During this period the catering branch of the ITGWU strongly opposed the employment of foreign staff. Oral evidence suggests that some Irish chefs and waiters were pressurised by the union to take senior positions, in order to exclude suitable foreign-born candidates.46 Two Irish chefs, Vincent Dowling in Restaurant Jammet, and Joe Collins in Jury’s Hotel, Dame Street, were sent abroad for training—to Paris and Switzerland—before returning to become chef de cuisine in their respective restaurants. The move from French to Irish head chefs, combined with a new Irish culinary aesthetic inspired by An Tóstal, may have influenced the change in listings of certain Dublin restaurants published in the 1965 Egon Ronay guide. In that year the classification of the Shelbourne Hotel Restaurant, The Red Bank Restaurant, Haddington House Hotel Restaurant, Metropole Georgian Room, Intercontinental Embassy Restaurant and Gresham Hotel Grill Room was changed from French’ cuisine to ‘Franco-Irish’ cuisine. Restaurant Jammet and the Royal Hibernian’s Lafayette Restaurant remained listed as ‘French’, whereas The Russell was listed as ‘Haute Cuisine’. However, restaurants such as the Old Ground Hotel in Ennis, Co. Clare, and The Pontoon Bridge Hotel in County Mayo were listed as ‘Plain Cooking’.47

FIG. 4—Menu from The Russell, 13 December 1966. (Source: Arthur McGee Private Collection.)

Pl. II—Pierre Rolland with the Russell Hotel Kitchen Brigade c. 1958. Front row (left to right): Nicky O’Neill, Jackie Needham, unnamed French chef, Monsieur Petrel (general manager), Pierre Rolland (head chef), Monsiuer Maurice (restaurant manager), Roger Noblet (sous chef), Henri Rolland, Arthur McGee. Middle Row (left to right): unnamed trainee manager, Brian Loughrey, Charlie O’Neill, Brendan Egan, Johnny Kilbride, Louis Corrigan, unnamed trainee manager. Back row (left to right): Michael (kitchen porter), unnamed commis, commis Mansfield, Eamon (Ned) Ingram, Mary (vegetable maid). Note: Arthur McGee notes that both Willie Woods and Jimmy Doyle are missing from the photo but were part of the brigade at that time. (Source: Arthur McGee Private Collection.)

Decline of haute cuisine in Dublin and rise of country house restaurants

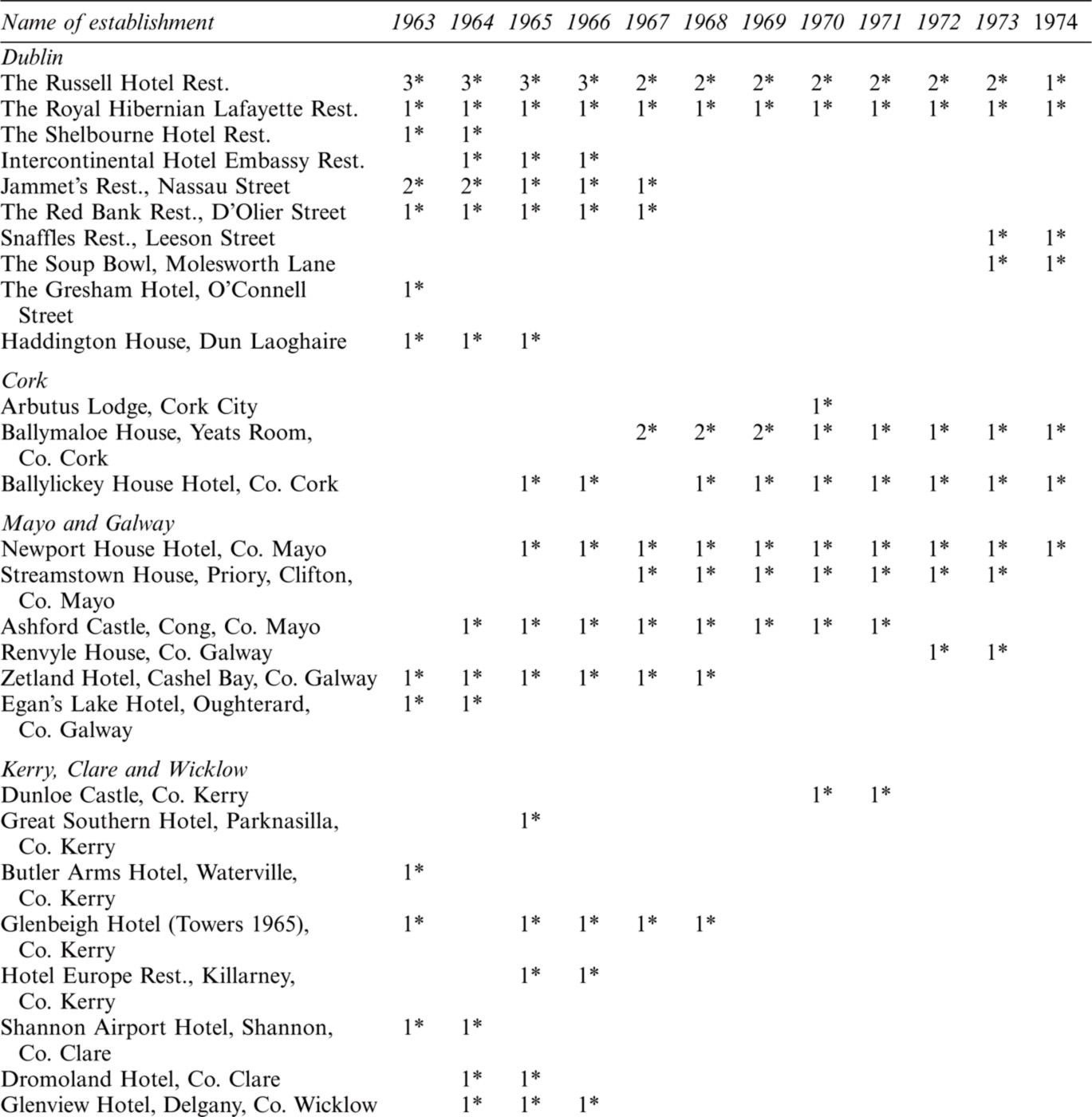

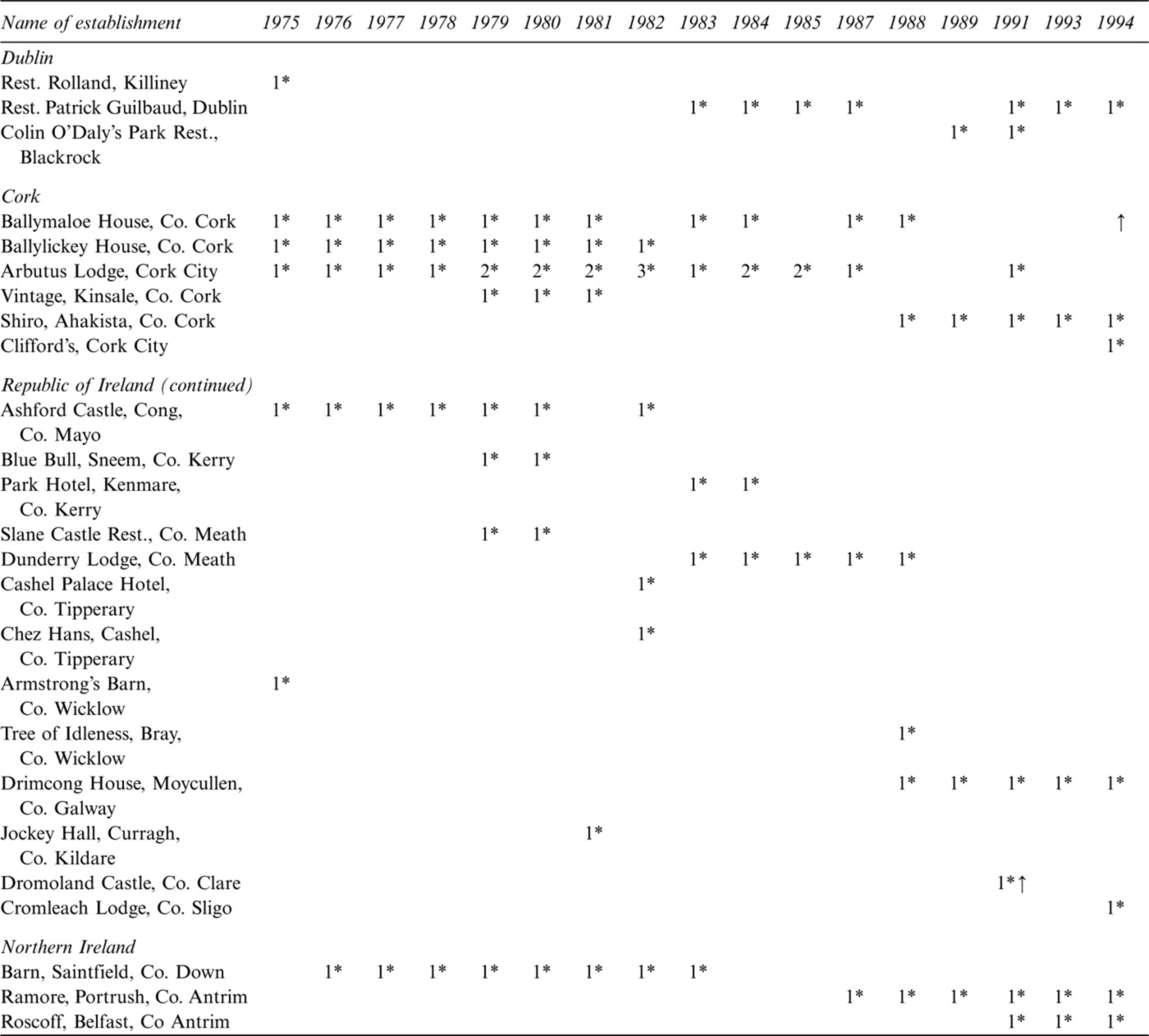

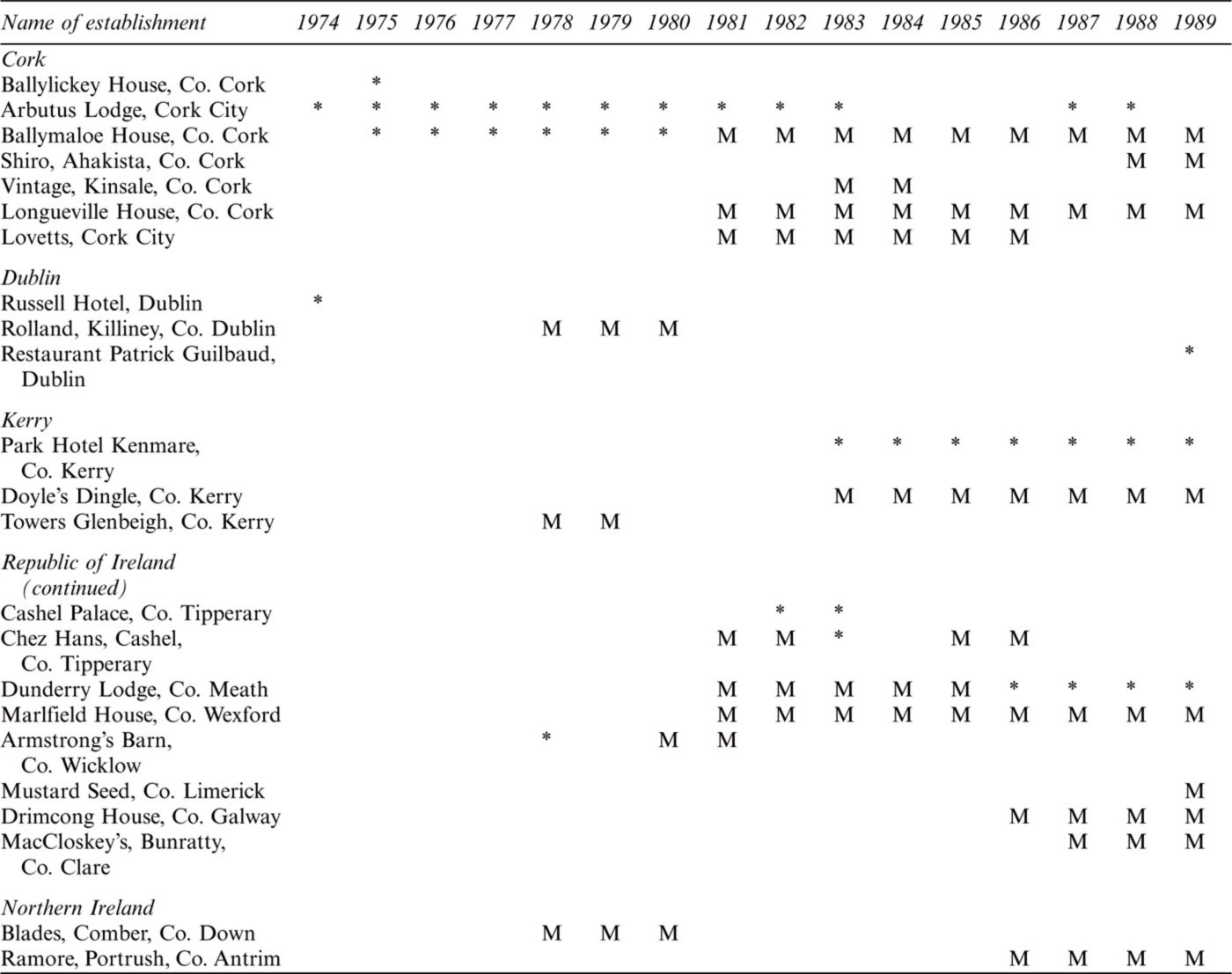

Dublin’s golden age of haute cuisine ended with the closure of Restaurant Jammet in 1967; and the subsequent closures of The Red Bank Restaurant in 1969 and The Russell Hotel in 1974. Dublin had seven starred restaurants in 1963 (Table 2), a number not equalled for more than 40 years (see Table 6). The pattern that emerges from the Egon Ronay and Michelin guides is that haute cuisine restaurants moved thereafter from the capital to country house hotels such as Arbutus, Ballymaloe and Ballylicky in County Cork; The Tower Hotel Glenbeigh, The Park Hotel Kenmare and Sheen Falls in Co. Kerry; Ashford Castle, Streamstown Bay and Newport House Hotels in County Mayo; and to restaurants such as Dunderry Lodge in County Meath, Shiro in County Cork and the Barn in Saintfield, Co. Down, where it remained until a resurgence recommenced in Dublin and Belfast from 1990 onwards.

Two reasons given for the closure of Restaurant Jammet in 1967 were the growing trend towards suburban living and the rising importance of car parking.48 A number of factors led to the demise of the traditional Escoffier style haute cuisine in the 1970s. Political and economic factors such as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries oil crisis, the Dublin bombings and banking strikes, all contributed. It has also been suggested that the introduction of a ‘wealth tax’ by the coalition government in 1973, resulted in a mass exodus of landed gentry from Ireland. The Shelbourne Hotel, Dublin, witnessed an instant 20% drop in business in 1973,49 and The Russell Hotel was also affected. The latter closed in 1974 after which The Royal Hibernian Hotel then assumed the mantle of Dublin’s last bastion of ‘Escoffier style’ haute cuisine until it too closed its doors in 1982.50 It is more than coincidental that some of the country house hotels and restaurants around the country which became locations of haute cuisine in the following decades belonged to the landed gentry who had departed.51

TABLE 2—Irish restaurants awarded stars (*) by the Egon Ronay guide in 1963–74. (Source: Egon Ronay guide (London, 1963–74).)

The decline in haute cuisine also reflected changes in social attitudes which reflected the emergence of a deferential but respectful outlook that did not leave dining untouched. Egon Ronay’s 1965 guide discussed emerging trends: the rise in Italian restaurants; the decline in the top end of the market, and a rise in the bottom end; and particularly the rise in younger clientele visiting restaurants:

A new type of restaurant clientele is being born—this is the most significant development in our catering scene. Young people eat out very much more often than years ago. They are more critical and outspoken, have less of a complex about walking into restaurants, and a large proportion have palates un-poisoned by public school feeding.52

A new phenomenon appeared towards the end of the 1960s when enthusiastic amateurs opened restaurants such as Snaffles on Leeson Street (Nicholas Tinne) and The Soup Bowl on Molesworth Lane (Peter Powrie), both in Dublin. These restaurants proved popular with a new generation of Irish restaurant clientele typified by emerging businessmen like Michael Smurfit and politicians like Charles Haughey. In Shanagarry, Co. Cork, another enthusiastic amateur, Myrtle Allen, a farmer’s wife, opened up Ballymaloe House in 1964, but she soon became an enthusiastic professional as shall be discussed later. This amateur phenomenon reflected a similar trend that had occurred slightly earlier in England.53

Guidebooks— Egon Ronay and Michelin

Since the advent of the motor car there has been a link between tyre companies and guidebooks. Maurice Edmond Sailland or Curnonsky (1872–1956) is considered the inventor of gastronomic motor-tourism when he encouraged French ‘gastro-nomads’ to explore the regional cookery of their country by automobile. He wrote a weekly column for Michelin in Le Journal from 1907. The introduction of these guidebooks to Ireland brought new discerning customers to Irish restaurants. With the arrival of the Egon Ronay guide in 1963 and the Michelin guide in 1974, it is easier to identify which restaurants were producing haute cuisine within the island and also how they compared to the United Kingdom, and the rest of Europe. Both guides used a one-, two- and three-star rating system, with three-star restaurants considered to be worth a special journey indicating exceptional cuisine. In 1963 Dublin was described by Egon Ronay as a ‘city of good restaurants’, noting that Jammet’s would have had three stars but for the fact that the patissiere was on a day off, and that both the Gresham and the Royal Hibernian would have had two stars except for poor desserts and the over use of table lamps in the Gresham.54 The guide expressed ‘our appreciation of the result an Irish–French team can produce in a kitchen. The Irish touch, we find has a peculiar, mellowing effect on the— sometimes too fancy—French cooking’. In 1963 the Egon Ronay Guide awarded The Russell three stars, the highest possible award, and in the 1965 guide, Egon Ronay wrote: ‘words fail us in describing the brilliance of the cuisine at this elegant and luxurious restaurant which must rank amongst the best in the world’.55 However, by 1974, when the Michelin guide to Great Britain and Ireland was first published, the only star awarded in Dublin appropriate to an exceptional restaurant was to The Russell Restaurant, which closed its doors that very year (Tables 2 and 3).

There are links, however, between the old and the new. For example, Declan Ryan, who achieved stars from both Egon Ronay and Michelin in Arbutus Lodge, Cork, trained for a while under Pierre Rolland in The Russell in Dublin. He and his brother Michael also trained in France with Jean and Pierre Troisgros whose restaurant in Roanne was awarded three Michelin stars in 1968, and voted ‘best restaurant in the world’ in 1972.56 Pierre Troisgros’s son Claude worked as sauce chef in Arbutus for a year.57 The Ryans trained Michael Clifford who would earn them another Michelin star when they took the lease of the Cashel Palace Hotel in County Tipperary in the 1980s. Another Russell-trained chef, Ken Wade, was responsible for the fine cooking in Ashford Castle. Colin O’Daly, the head chef who first won a Michelin star in the Park Hotel Kenmare in 1983, trained under Bill Ryan, another ex-Russell chef, in the Dublin Airport Restaurant and later under Ken Wade in Ashford Castle. When Shannon Airport Restaurant was awarded an Egon Ronay star in 1963 and 1964, the chef was Willie Ryan who had trained in the Besson-owned Royal Hibernian Hotel in Dublin.58

TABLE 3—Irish restaurants awarded stars from the Egon Ronay guidea in 1975–94. (Source: Egon Ronay guide (London, 1975–94).)

a Egon Ronay sold the rights to his guides to the Automobile Association in 1985. The rights were subsequently sold to Leading Guides International, a company that went bankrupt in 1997. Comparisons in this table stop at 1994 because consistency in awards is lacking under the new owners. By 1994 there is a separate Egon Ronay Jameson Guide for Ireland with Georgina Campbell as the regional editor, which eventually becomes the Georgina Campbell guide in 1997 when Egon Ronay Publications ceased publication.

Three Michelin-starred Irish restaurants were run by women who had no formal training. The most significant and influential was Myrtle Allen, whose arrival was announced in 1964 with an advertisement in the Cork Examiner—‘Dine in a country house’. The Irish chef Gerry Galvin, of the Vintage, Kinsale, and Drimcong House, Galway, was greatly influenced by Allen. He once said:

Myrtle served home cooking in a refined environment, using whatever fresh, local foods were available. This is commonplace now, but it was fairly revolutionary then. At the time, anything really good was expected to have been imported. We were still suffering from the notion that anything that was our own was inferior.59

Myrtle Allen published The Ballymaloe cookbook in 1977,60 and in 1981 accepted an invitation to run a restaurant La Ferme Irlandaise in Paris which brought modern Irish food to the French capital.61 In 1986 she became a founding member of the European chef organisation, Eurotoques International. She has arguably been one of the most influential Irish people to date in promoting Irish food.62 Myrtle’s son Tim and daughter-in-law Darina opened the Ballymaloe Cookery School in 1983, and have trained and influenced generations of chefs and restaurateurs.

The second amateur, Catherine Healy, was dubbed ‘Ireland’s greatest female chef’.63 She was running a playgroup, and, when her husband Nicholas was made redundant, they opened Dunderry Lodge, which was tremendously successful throughout the 1980s and only closed when Catherine became terminally ill.64 The third Michelin-starred restaurant, Shiro, was run by Japanese-born Kei Pilz and her German husband Werner Pilz in their house in Ahakista, Co. Cork, and again the restaurant closed following her death in 2001.65 Other award-winning female chefs/restaurateurs include Mary Bowe (Marfield House), Maura Tighe (Cromleach Lodge), Cath Gradwell (Aldens), Mercy Fenton (Jacobs on the Mall), and ‘three well-travelled ladies’ (the Barn in Saintfield, Co. Down).66

Declan Ryan credits discerning French tourists with being the arbiters of taste at his Cork City restaurant and their arrival was facilitated by the establishment of a direct Rosslare–Le Havre ferry link in 1973. It is important also not to overlook the impact that President and Madame Charles de Gaulle’s Irish holiday in Killarney and Cashel House in Galway in 1968 had on encouraging growing numbers of discerning French diners to visit Ireland in the early 1970s. Georgina Campbell notes that leading French chefs such as Paul Bocuse and Jean Troisgros came on regular fishing holidays and that Bocuse once related that a slightly undercooked dish of wild salmon served in Ernie Evans Towers Hotel in Glenbeigh was ‘the birth of Nouvelle Cuisine’.67

Nouvelle cuisine and the rise of the chef/proprietor

The nouvelle cuisine movement was rooted in the ‘cuisine de marché’ which originated with Fernand Point as a rebellion against the Escoffier orthodoxy, particularly as it was practised in international hotel cuisine. Point trained a generation of young French chefs such as Paul Bocuse and the Troisgros brothers after the Second World War who went on to become chef/proprietors championing this new aesthetic. In many ways, Myrtle Allen was following many of the rules of ‘nouvelle cuisine’ by composing her Ballymaloe menu daily based on the best local available market ingredients. By the mid-1970s and early 1980s, however, the term ‘nouvelle cuisine’ had acquired a pejorative meaning of small portions artistically presented and of inflated prices. This artistic aspect reflected Japanese influence following French chefs’ experience at the Tokyo Olympics in 1964 and at the Osaka Expo in 1970. This latter aesthetic reached Ireland in the early 1980s.

A synopsis of Henri Gault’s ‘ten commandments’ of nouvelle cuisine includes: reduced cooking time for fish, game, vegetables and pasta; smaller menus based on market-fresh ingredients; new dishes; advanced technology; the aesthetics of simplicity; and a knowledge of dietetics. Stephen Mennell has pointed out that Gault and Millau omitted one key characteristic common to most nouveaux cuisiniers, that they were mostly chef/proprietors of their own restaurants. The significance of chef/proprietors mirrors the gradual rise in the status of chefs and their changing public profile. This would culminate in the 1990s with the cult of the ‘celebrity chef’. In cities, many of the new restaurants opened not in the centre but in the affluent suburbs.68 Analysis of both the Egon Ronay and Michelin guides show that many of the award winners were either chef/proprietors, and/or grew much of the produce they cooked in their kitchen garden, often attached to a country house hotel. One may instance, Egon Ronay’s description of Armstrong’s Barn in Wicklow in 1975:

the chef owes his training and success to the proprietor, Peter Robinson, who spent ten years in France and Switzerland before buying the Barn two years ago. . . . Everything is fresh and Mr Robinson scours the countryside for produce; even driving daily to meet trawlers landing their catch. The result is the best local materials available with meticulous care and attention to detail.69

Robinson subsequently moved to Sneem, Co. Kerry, and was awarded stars for the Blue Bull in 1979 and 1980 (Table 3).

The magic combination seems to have been Irish ingredients, French culinary practice, and warm Irish hospitality. Ballylickey House Hotel at the head of Bantry Bay in County Cork developed from the Franco–Irish Graves family’s seventeenth-century private home. Egon Ronay noted that Mrs Graves’s French touch showed in the chic décor, the antique furniture, flower arrangements and exquisite lighting. He concluded ‘where three French chefs set to work on fine ingredients so plentiful in Ireland the results are likely to be memorable: that is what happens here. . . . Things like fresh salmon in sorrel sauce, terrines, soups, follow each other from the kitchen in a tantalising procession, served by charming, gentle girls’. In Newport House in County Mayo, ‘young French and Irish chefs under the close supervision of the proprietor’s wife Mrs. Momford-Smith’ cooked locally caught salmon and trout, the hotel’s own livestock and garden produce.70 Few city restaurants possessed kitchen gardens but specialist suppliers of game, fish and herbs began to respond to demand from haute cuisine restaurants both urban and rural.71

One of the first Dublin restaurants to be opened by a chef/proprietor was The King Sitric (Aidan McManus) in Howth (1971 to the present). This was followed by The Mirabeau (Sean Kinsella) in Sandycove (1972–84), Johnny’s (Johnny Opperman) in Malahide (1974–89), Le Coq Hardi (John Howard) in Ballsbridge (1977–2001), The Guinea Pig (Mervyn Stewart) in Dalkey (1977 to the present), and Rolland (Henri Rolland) in Killiney (1974–c. 1986).72 Most of these chef/proprietors were classically trained in Dublin and abroad. Sean Kinsella is widely regarded as Ireland’s first ‘celebrity chef’ as he actively courted media attention. His style was emulated by Mervyn Stewart who realised that restaurateurs also needed to be active in marketing their business.73 Three restaurants, all of which opened in the 1980s, can be said to best represent the nouvelle cuisine movement in Dublin. They are Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud, The Park (Colin O’Daly), and White’s on the Green (Michael Clifford) (Table 3). The 1980s were a difficult time for fine-dining restaurants in Ireland, as cheaper establishments such as pizzerias and ethnic restaurants became popular.

Patrick Guilbaud, a French-born chef, trained in the leading restaurants in Paris before moving to the Egon Ronay one-starred Midland Hotel, Manchester, in order to learn English. He eventually opened his own restaurant in Cheshire where one of his customers, Barton Kilcoyne, invited him to visit Dublin. He soon moved to Dublin and opened a purpose-built restaurant, designed by architect Arthur Gibney, which set standards in dining that had been missing since the Jammet era.74 A description of Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud in the Irish Times in 1982 is brief: ‘the restaurant is bright and elegant with French staff serving French food’.75 The restaurant did not enjoy immediate commercial success; it took a while for the Irish clientele to become accustomed to the small portions and la nouvelle cuisine d’Irlande served by Guilbaud. However, the restaurant did receive critical acclaim, being awarded an Egon Ronay star in 1983. The early 1980s proved to be a difficult time for Irish restaurateurs due to a combination of general economic conditions and fiscal changes made by the government (23% value added tax on meals). Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud ran into financial difficulties in the mid-1980s, but an investment by two wealthy clients cleared the restaurant’s debts. Their trust was rewarded when the restaurant won its first Michelin star in 1989—the first Dublin Michelin star since the closure of The Russell Hotel in 1974 (Table 4). The restaurant was awarded two Michelin stars in 1996 and it moved premises in 1997 to the five-star Merrion Hotel where it is now located.76 During the last two decades of the twentieth century Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud set the standard of haute cuisine that other restaurants emulated. Its kitchen and dining room also acted as nurseries for young talent, both Irish and foreign-born. Some restaurants even advertised that their chef was ‘ex-Patrick Guilbaud’s’ as a marker of the high standard of food that they served.

TABLE 4—Irish restaurants awarded Michelin star (*) or red ‘M’ 1974–89. (Source: Michelin Guide to Great Britain and Ireland (Watford, Herts, 1974–89).)

Many young Irish chefs and waiters emigrated during the 1980s although some, such as Kevin Thornton, Michael Clifford, Ross Lewis, Robbie Millar and Paul Rankin, returned during the late 1980s and early 1990s with knowledge of nouvelle cuisine and fusion cuisine gained in the leading restaurants of London, Paris, New York, California and Canada.77 They brought a new energy and confidence to the Irish restaurant industry on their return. Both Rankin and Clifford trained with the Roux Brothers in London, and Thornton with Paul Bocuse in Lyon.78 In 1988 Clifford left White’s on the Green to open his own restaurant in Cork. The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the opening of exciting new restaurants in Dublin such as The Wine Epergne (Kevin Thornton) and Clarets (Alan O’Reilly), both of which produced fine dining in difficult economic conditions. They were joined by Ernie Evans of the Towers Hotel in Glenbeigh, who opened Ernie’s in Donnybrook. During the 1990s clusters of award-winning restaurants appeared in Dublin, Cork, Kerry and Belfast with individual restaurants emerging in a number of other counties around Ireland (Table 5). Restaurants run by a chef/proprietor were now the norm, though not all were financially successful.79 One factor, which led to the growing popularity of dining out in Irish restaurants and the rising status of Irish chefs, was the growth in food writing in the national press from the 1980s. Restaurant reviewers such as Helen Lucy Burke in the Sunday Tribune became powerfully influential in the industry. Publications such as Food and Wine Magazine also profiled Irish chefs and reviewed restaurants and presided over annual award ceremonies.80

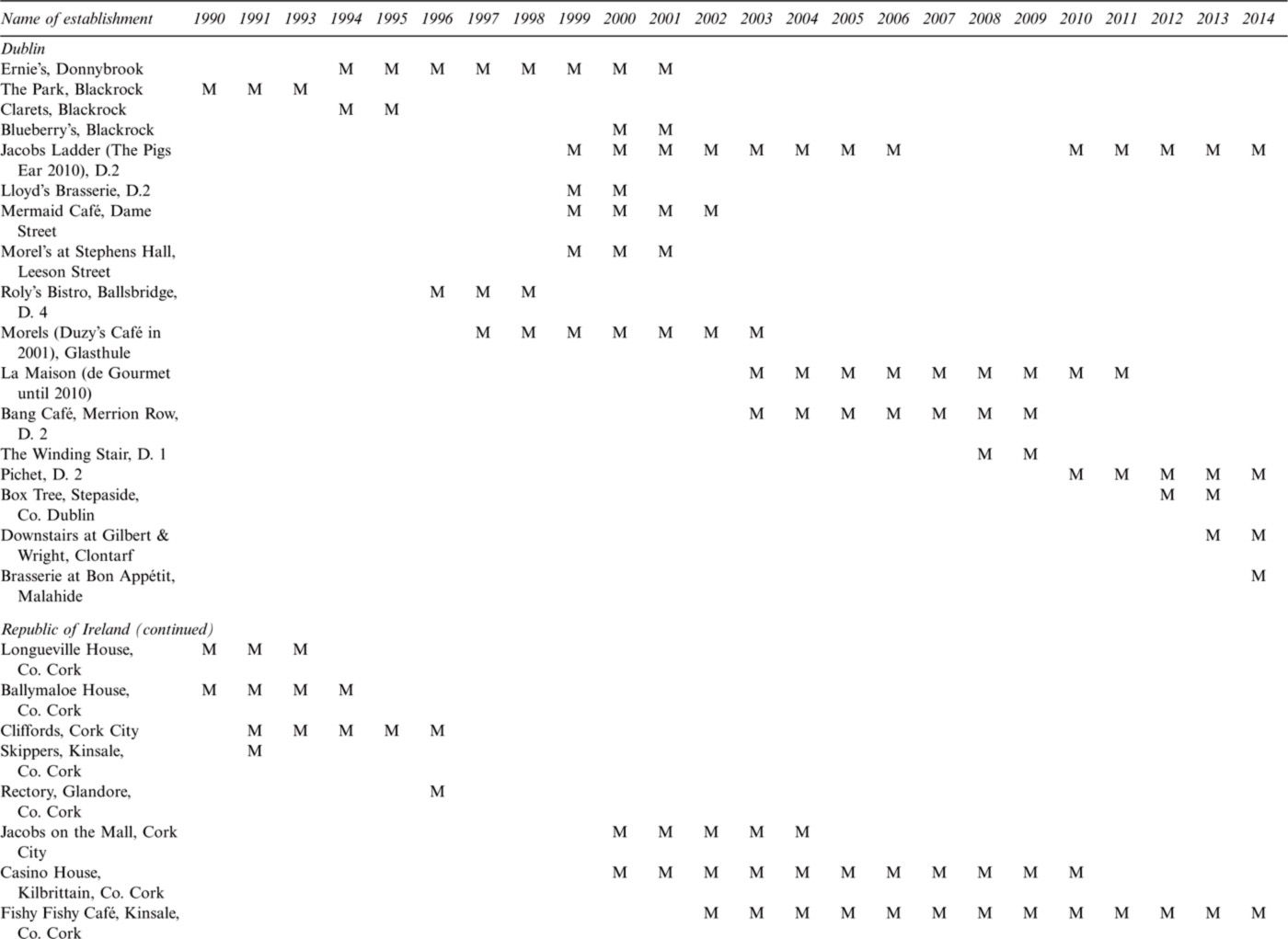

‘New Irish cooking’: a second ‘golden age’ of haute cuisine restaurants (1994–2014)

The Irish Times reported in 1996 that Ireland had the most dynamic cuisine of any European country, a place where in the last decade ‘a vibrant almost unlikely style of cooking has emerged’.81 This dynamism was manifesting on both sides of the border. Restaurant Roscoff, opened by Paul and Jeanne Rankin in 1989, won its first Michelin star in 1991.82 According to Rankin, ‘Roscoff was really the first proper restaurant in Belfast. It gave people an excuse to come back to the city—to forget about the Troubles and feel like they could be dining in London or New York’.83 Factors influencing this new dynamism included the rising wealth of Irish citizens which made dining in restaurants a regular pastime rather than an occasional treat, and also the changing tastes of a public who were more widely travelled than any previous Irish generation. In 1996 the year Michelin awarded two stars to Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud; Thornton’s Restaurant in Portobello received its first star. New stars awarded to Shanks and Deane’s in Northern Ireland coincided with an air of hope that emerged following the beginning of the peace process (Table 6). In 1998 another Michelin star was awarded to Conrad Gallagher’s Peacock Alley. By 1999 the chief executive of the Restaurant Association of Ireland declared ‘we have a dining culture now, which we never did before’.84

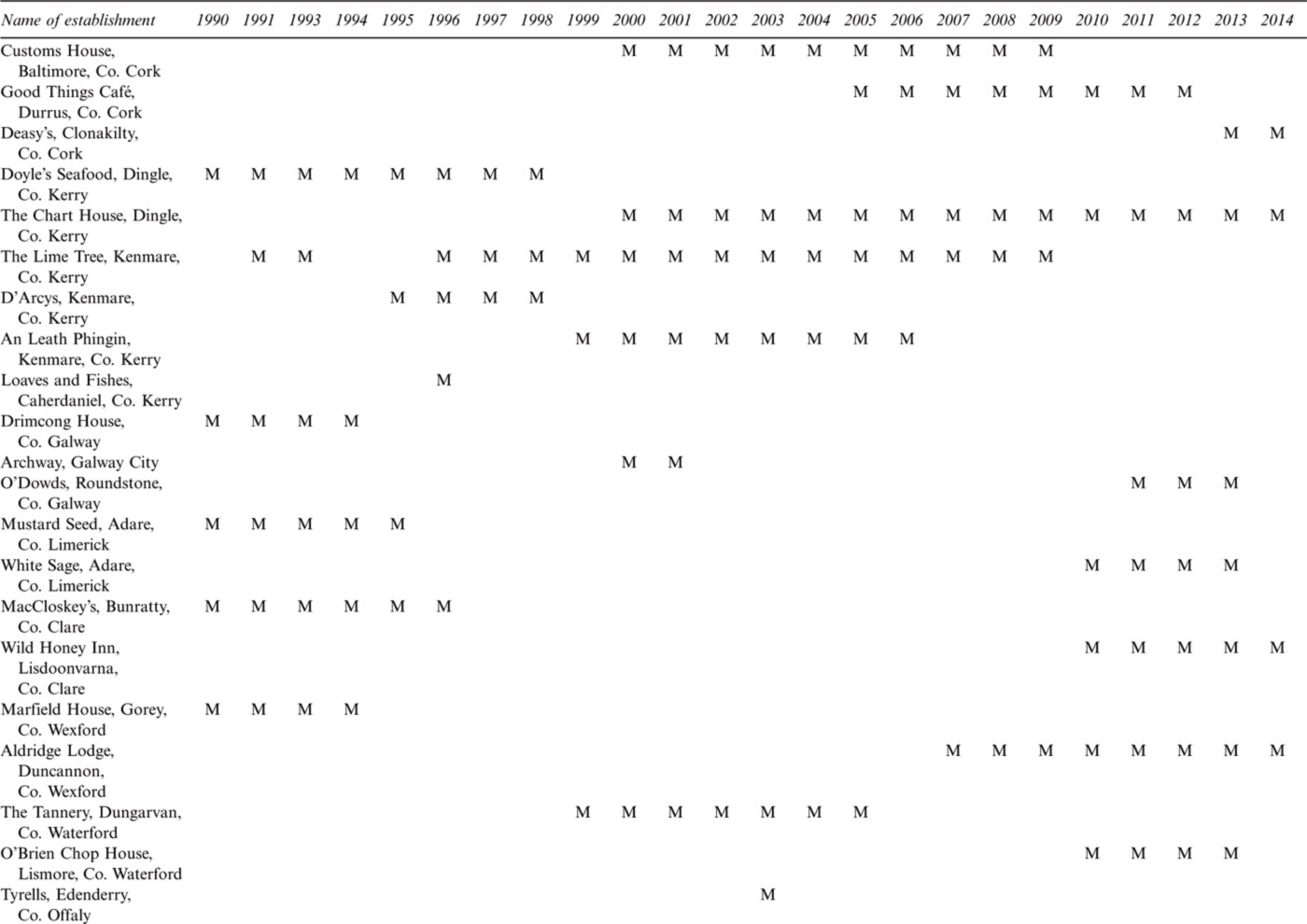

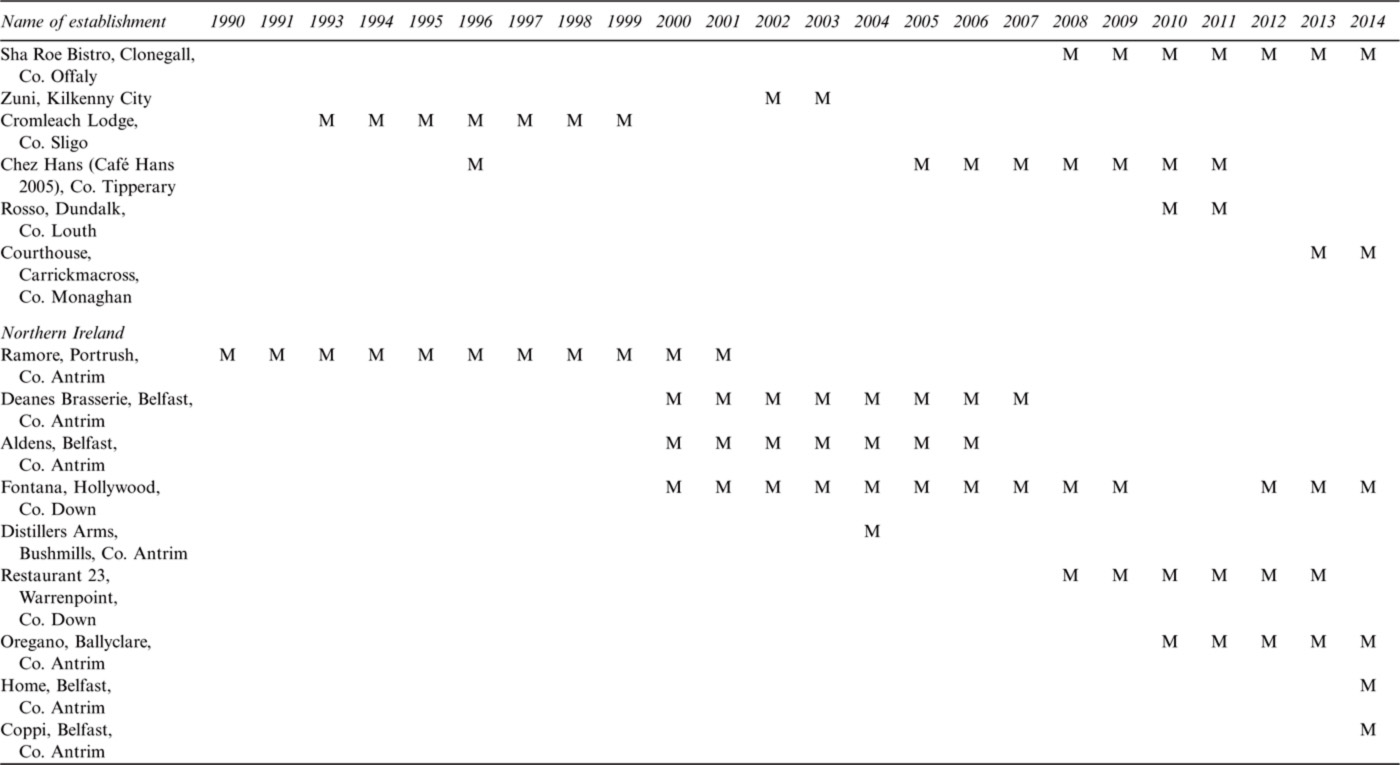

TABLE 5—Restaurants awarded a Michelin red ‘M’ in 1990–2014. (Source: Michelin Guide to Great Britain and Ireland (Watford, Herts, 1990–2014).)

In 2001 Kevin Thornton became the first Irish chef to be awarded two Michelin stars. In the first years of the new millennium Michelin stars were awarded in Dublin to L’Écrivain (Derry Clarke) and to Chapter One (Ross Lewis) which had both held Red ‘M’s from the mid-1990s. Two new Michelin stars were awarded in 2008 to Bon Appétit (Oliver Dunne) in Malahide, and to Mint (Dylan McGrath) in Ranelagh. Both Dunne and McGrath trained in Ireland’s best restaurants, such as The Commons, and Roscoff, then in London with Gordon Ramsay, Tom Aikens and John Burton Race. The food of these award-winning Irish chefs is often described as ‘new Irish cooking’ in that it champions local, seasonal, often artisan ingredients or food and presents them using their own individual flair.

In January 2011 Le Guide du Routard, the travel bible for the French-speaking world, praised Ireland’s restaurants for being unmatched the world over for the combination of quality of food, value and service.85 This second ‘golden age’ has been maintained despite the current difficult economic environment. The 2014 Michelin Guide not only awarded stars to five Dublin restaurants, but also awarded stars to four restaurants outside Dublin—the highest number of starred restaurants in Ireland since the guide was first published in 1974. In 2013, however, a number of Michelin Red ‘M’ restaurants closed; these included O’Brien Chop House in Lismore, Co. Waterford; White Sage in Adare, Co. Limerick; and most notably Paul Rankin’s Cayenne in Belfast which had traded since 1989. The closure of the latter was blamed on Union flag protests and on the change in the Shaftsbury Square area over the last number of years.86

Conclusion

The projection and presentation of Irish cuisine, both foreign-influenced and home-inspired, have given it a notable public profile. Its beginnings were in French haute cuisine; its further progress came in the development of restaurants, especially in the early golden age of Dublin restaurants, the ones so strongly influenced by French families such as the Jammets, Bessons and Rollands, all of whom adopted Ireland as home. The latest important French influence is prospering: Patrick Guilbaud was advised that if his restaurant was half as successful as Jammet’s had been, he would be doing extremely well. Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud, now in its thirtieth year in business, has already outlasted The Russell Restaurant in longevity but has another 37 years to go to equal Jammet’s as the most influential and successful haute cuisine restaurant Ireland has had. There is a neat symbolism involved in Patrick Guilbaud’s purchase of the Harry Kernoff painting of Jammet’s: it signifies both continuity and tradition; it ties haute cuisine to Irish imagery, and it reflects the degree to which French influence has dominated Irish public imagination in that most important area over two centuries.

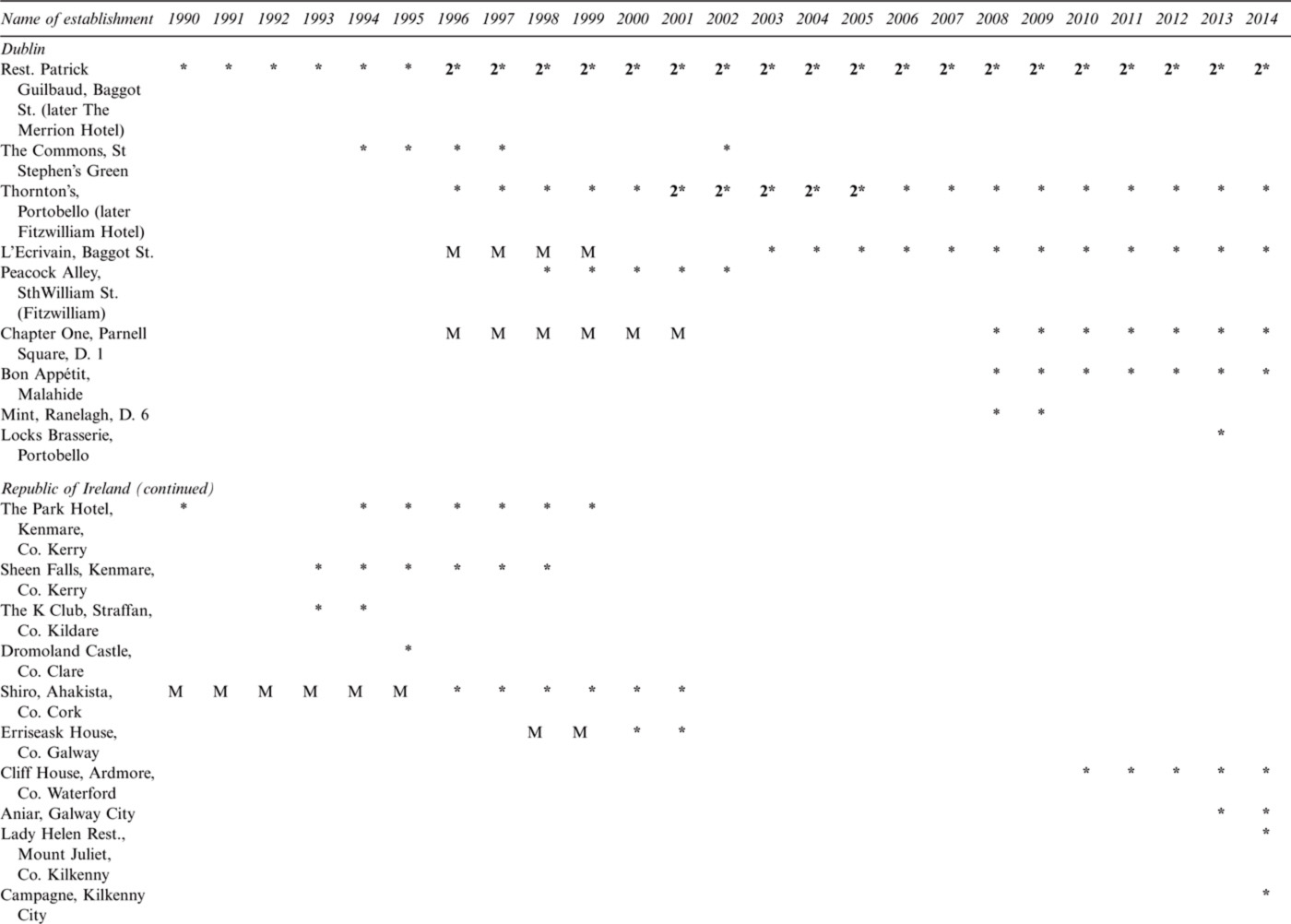

TABLE 6—Restaurants awarded Michelin stars in Ireland 1990–2014. (Source: Michelin Guide to Great Britain and Ireland (Watford, Herts, 1990–2014).)

* Author’s e-mail: mairtin.macconiomaire@dit.ie

doi: 10.3318/PRIAC.2015.115.06

1 Nick Bramhill, ‘Irish chefs best in world’, Sunday Independent, 9 January 2011, available at: www.independent.ie/irish-news/irish-chefs-best-in-world-26612329.html (last accessed 8 February 2015).

2 Ma´irtı´n Mac Con Iomaire, ‘Louis Jammet’, in James McGuire and James Quinn (eds), Dictionary of Irish Biography (9 vols, Cambridge, 2009), vol. 4, 956–8.

3 Irish Times, 7 February 1956, 11.

4 Bramhill, ‘Irish chefs’.

5 For a detailed discussion on Dublin taverns, coffee houses and clubs see Ma´irtı´n Mac Con Iomaire, ‘Public dining in Dublin: the history and evolution of gastronomy and commercial dining 1700–1900’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 25:2 (2013), 227–46.

6 Rebecca L. Spang, The invention of the restaurant: Paris and modern gastronomic culture (Cambridge, 2000), 130–3; Stephen Mennell, All manners of food, 2nd edn (Chicago, IL, 1996), 141–2.

7 Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The physiology of taste, trans. A. Drayton (London, 1994), 267.

8 Mennell, All manners, 155.

9 Mac Con Iomaire, ‘Public dining in Dublin’, 227.

10 Henderson’s Belfast directory and Northern repository 1846–7 (Belfast, 1846), 80; The Belfast directory 1887 (Belfast, 1887), 155, both available at http://streetdirectories.proni.gov.uk/ (8 February 2015).

11 Irish Times, 22 June 1899, 1.

12 The X.L. Vegetarian Restaurant, 27 Cornmarket, Belfast, see the Belfast and Ulster directory (1900), 235, available at: http://streetdirectories.proni.gov.uk/ (8 February 2015); Michael Kennedy, ‘‘‘Where’s the Taj Mahal?’’: Indian restaurants in Dublin since 1908’, History Ireland (July/August 2010), 50–2; the venture lasted less than a year. Note that London’s first ever Indian restaurant was opened in 1810 by a Bengali, Sake Dean Mahomet, who had lived in Cork for 25 years and had an Irish wife, Jane Daly.

13 A photo of 39 members of the Hotel and Restaurant Proprietors Association of Ireland appeared in the British trade journal The Chef on 23 May 1896; see also D. J. Wilson, ‘The tourist movement in Ireland’, Journal of the Statistical and Social Science Society of Ireland XI (1901), 56–63.

14 Frank Corr, Hotels in Ireland (Dublin, 1987), 58.

15 ‘Celebrated chefs—No. XL: G. Frederick Macro’, The Chef: A Journal for Cooks, Caterers and Hotel Keepers II:44 (1896), 1–2.

16 Note the ‘Braized Ham a` la Irlandaise’ on the menu.

17 Direct comparison between cities is exacerbated by the fact that the listings are no indication of the type or quality of food served. For Dublin, see Ma´irtı´n Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence, development and influence of French Haute Cuisine on public dining in Dublin restaurants 1900–2000: an oral history’, unpublished PhD thesis, Dublin Institute of Technology, 2009, 3 vols, vol. 2, 81–2, 140–4, 185–6.

18 Nearly half of the 32 restaurants listed in the Belfast and Ulster directory 1924 were affiliated with the Irish Temperance League.

19 Based on analysis of the 1901 and 1911 censuses’ search options, see www.census.nationalarchives.ie/search/#searchmore (8 February 2015).

20 Guy’s Cork City and county almanac and directory for 1910 (Cork [1910]), 178, 273, available at: www.corkpastandpresent.ie/places/streetandtradedirectories/1910directory/1910directoryguys/#/273/ (8 February 2015).

21 The most famous chef and hotelier partnership began in 1890 when Escoffier and Ritz accepted an invitation from Richard D’Oyly Carte to his newly opened Savoy Hotel in London.

22 Máirtin Mac Con Iomaire, ‘Searching for chefs, waiters and restaurateurs in Edwardian Dublin: a culinary historian’s experience of the 1911 Dublin Census online’, Petits Propos Culinaires 86 (2008), 92–126.

23 German chefs and waiters were interned during the First World War and this provided opportunities for both Swiss hospitality workers and also for waitresses to serve in hotels and restaurants that had previously been male bastions. See Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 2, 133–82.

24 The 1901 Census shows Everest as a restaurant manager living in Belfast; for more detailed examples of Dublin see Mac Con Iomaire, ‘Searching for chefs’, 92–106.

25 Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 2, 271–325.

26 For more information see Ma´irtı´n Mac Con Iomaire, ‘Zenon Geldof’, in McGuire and Quinn (eds), Dictionary of Irish biography, vol. 4, 46–7; for details on the Gygax and Opperman families, see Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 3, 269–94 and 332–8 (interviews with Fred Gygax and Johnny Opperman).

27 For a full analysis of these establishments see Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 2, 133–398.

28 Other notable chefs who worked for various Lord Lieutenants in the vice-regal lodge in Dublin include Alfred Suzanne, Reginald Bateman and Signor Lama, see Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 2, 71–182.

29 For more detailed information on Restaurant Jammet, see Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 2 or Alison Maxwell, Jammet’s of Dublin (Dublin, 2012).

30 Irish Times, 6 January 1928.

31 ‘One thousand diners in a restaurant’, Dublin Evening Mail, 8 November 1928.

32 Corporation of Dublin, A book of Dublin (Dublin, 1929).

33 Irish Times, 18 January 1930.

34 The Irish Hotel and Club Manager, May 1934.

35 The Regal Rooms opened attached to the reopened Theatre Royal, Dublin; Irish Times, 23 September 1935; see Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 2, 183–245.

36 The Belfast and Ulster directory (Belfast, 1924) was compiled at the Belfast Newsletter office.

37 For oral evidence of ‘gastro-tourists’ to Dublin at this time see Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 3, 176–88 and 313–31. (Interviews with Jimmy Kilbride, Tony and Annie Sweeney, and Garret Fitzgerald.)

38 John Ryan, ‘There’ll never be another Jammet’s’, Irish Times, 11 April 1987, Weekend, 3.

39 Daily Express, 14 November 1943, 1; Christopher Sands, The Gresham for style (Dublin, 1994), 40–1.

40 Shaun Boylan, ‘Timothy ‘‘Toddy’’ O’Sullivan’, in McGuire and Quinn (eds), Dictionary of Irish biography, vol. 7, 983–5.

41 Charles Graves, Ireland revisited (London, New York, 1949); R. Lacoste, ‘Les Cuisiniers Francais Partis: Les Anglais ne mangent plus que des conserves et des soupes en poudre’, Journal l’Epoque, 22 June 1947.

42 Irish Times, 7 February 1956, 11.

43 Egon Ronay, Egon Ronay’s 1965 guide to hotels and restaurants in Great Britain and Ireland with 32 motoring maps (London, 1965), 464.

44 For more information see Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire, ‘Kenneth George Besson’, in McGuire and Quinn (eds), Dictionary of Irish biography, vol. 1, 505–06; for more information see Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire, ‘Pierre Rolland’, in McGuire and Quinn (eds), Dictionary of Irish biography, vol. 8, 594–5.

45 Anon., ‘The Russell Hotel’, The Irish Hotelier (February 1954), 13.

46 Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 3, 147–75 and 189–218. (Interviews with Christy Sands and Arthur McGee.)

47 Ronay, 1965 guide; the 1950s witnessed efforts to boost tourism such as An To´stal, a festival to promote Irish culture and heritage (see Irene Furlong, ‘Tourism and the Irish State in the 1950s’, in Dermot Keogh et al. (eds), Ireland in the 1950s: the lost decade (Cork, 2004), 164–86). Part of this movement was the promotion of traditional Irish food. In 1958 Bord Fa´ ilte E´ ireann, working with Michael Mullen (ITGWU), suggested the inauguration of an Irish Food Festival Week. To bring this idea to fruition, a panel of Dublin’s leading chefs were formed*and named Seanad Co´caire na hEireann: Panel of Chefs of Ireland*see Panel-of-Chefs, Jubilee Stockpot 1958–1983 (Galway, 1983).

48 Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 3, 339–62. (Interview with Ro´ isı´n Hood.)

49 Michael O’Sullivan and Bernardine O’Neill, The Shelbourne and its people (Dublin, 1999), 161.

50 The building was subsequently redeveloped into offices and a shopping arcade*The Royal Hibernian Way.

51 For examples see www.irelands-blue-book.ie/ (8 February 2015) which includes properties throughout the whole island of Ireland.

52 Ronay, 1965 guide, 16.

53 Gregory Houston-Bowden, British gastronomy: the rise of great restaurants (London, 1975), 127.

54 Egon Ronay, Egon Ronay’s guide to 1,000 eating places in Great Britain and Ireland including 250 London pubs (London, 1963), 362, 367.

55 See Tables 2 and 3 for a list of Irish restaurants awarded stars by Egon Ronay from 1963–1994; Ronay, 1965 guide, 464.

56 Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 3, 295–312 (interview with Declan Ryan); voted the best restaurant in 1972 by the Gault Millau restaurant guide Le Nouveau Guide (Paris, 1972).

57 For Claude Troisgros mastery of sauces see Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire, ‘Identified by taste: the chef as artist?’, TEXT Special Issue Website Series No. 26 (April 2014), 1–8, available at: www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue26/MacConIomaire.pdf (8 February 2015).

58 Shannon Airport Restaurant and later the Shannon School of Hotel Management were set up by Brendan O’Regan, a waiter in the Stephen’s Green Club, following a request by Se´an Lemass. See Corr, Hotels in Ireland, 46–51.

59 Joe McNamee, ‘Myrtle Allen’s recipe for success’, Irish Examiner, 2 December 2013, available at: www.irishexaminer.com/lifestyle/features/myrtle-allens-recipe-for-success-251259.html (8 February 2015).

60 Myrtle Allen, The Ballymaloe Cookbook (London, 1977)

61 It is interesting to note that the loss of the Egon Ronay star in 1982 seems to arise from Myrtle focusing her energy on the Parisian restaurant. The same happened to the Ryan brothers when they were awarded a star in Cashel Palace in 1982 only to lose their three-star rating Arbutus in 1983.

62 For further details see Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 3, 92–119. (Interview with Myrtle Allen.)

63 See www.independent.ie/lifestyle/where-to-eat-without-it-costing-an-arm-and-a-leg-26518881.html (8 February 2015).

64 ‘Nick Healy—accomplished chef and front of house man acclaimed at Dunderry Lodge’, Irish Times, 9 June 2012, obituary, 14.

65 The background to Shiro is available in Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 3, 363–83. (Interview with Frank Corr.)

66 Egon Ronay, Egon Ronay’s Dunlop 1975 guide to Great Britain and Ireland (London, 1974), 721.

67 Georgina Campbell, ‘Development of Irish food and hospitality’, in Georgina Campbell (ed.), Egon Ronay’s Jameson guide 1994 Ireland (London, 1994), 97.

68 Henri Gault, ‘Nouvelle Cuisine’, in Harlan Walker (ed.), Cooks and other people: proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1995 (Devon, 1996), 123–7. Mennell, All manners, 164; Ma´irtı´n Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The changing geography and fortunes of Dublin’s haute cuisine restaurants 1958–2008’, Food, Culture & Society 14:4 (2011), 525–45.

69 Ronay, 1975 guide, 721–2.

70 Ronay, 1975 guide, 722; Egon Ronay, Egon Ronay’s 1974 guide (London, 1974), 679.

71 La Rousse Foods was set up in the early 1990s by Marc Amand, while working as sous chef in Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud; see www.laroussefoods.ie (8 February 2015).

72 Henri Rolland was the son of the famous Pierre Rolland from The Russell Hotel.

73 Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 3, 627–47. (Interviews with Sean Kinsella and Mervyn Stewart.)

74 For a more detailed discussion of Guilbaud’s and the other Dublin Restaurants, see Mac Con Iomaire, ‘The emergence’, vol. 2, 326–98; vol. 3, 593–603 (interview with Patrick Guilbaud).

75 Irish Times, 2 June 1982, 7.

76 A trend re-emerged towards the end of the twentieth century for five-star hotels to entice Michelin-starred chefs to locate their restaurants in the hotels. This was the case with Peacock Alley which moved from SouthWilliam Street to the Fitzwilliam Hotel. It was eventually replaced by Thornton’s Restaurant which moved from Portobello.

77 Paul and Jeanne Rankin built a restaurant empire which once employed 500 staff but by 2008 they had been forced to sell all but one establishment, named ‘Cayenne’, which replaced Roscoff around 2000 (see Table 6).

78 Sandy O’Byrne, ‘Cooking come home: is it time for Irish cuisine to come of age?’, Irish Times, 3 December 1988, 23.

79 Both O’Daly and Clifford’s restaurants went bankrupt; Cafe´ Paradiso, a world renowned vegetarian restaurant opened in October 1993 in the Lancaster Quay building that once housed Clifford’s. O’Daly went on to success with Roly’s Bistro in Dublin.

80 The Irish Food Writers Guild was formed in 1990 to promote high professional standards of knowledge and practice among food writers*see www.irishfoodwritersguild.ie (8 February 2015).

81 John McKenna, ‘Euro nosh’, Irish Times, 26 June 1996, 44.

82 The couple had worked in Albert Roux’s Michelin-starred London restaurant, Le Gavroche. They attracted young keen chefs from all over Ireland, such as Neven Maguire, Robbie Millar and Dylan McGrath, who went on to work or open some of the restaurants listed in Tables 5 and 6. They closed Roscoff and relaunched it as a more casual restaurant Cayenne which won a Michelin red ‘M’ from 2001until it closed in 2013.

83 Interview with Paul Rankin in Daily Mail, 18 March 2010, available at: www.dailymail.co.uk/travel/article-1258134/St-Patricks-Day-Its-Guinness-Belfast-Irishchef-Paul-Rankin.html#ixzz2qWANN100 (8 February 2015).

84 Katherine Holmquist, ‘Take a top chef, place in a swanky location and stir well for a winning restaurant’, Irish Times, 20 October 1999, 43.

85 Bramhill, ‘Irish chefs’.

86 Lesley-Anne McKeown, ‘Celebrity chef Paul Rankin blames flag protests on restaurant closure’, Irish Independent, 26 March 2013, available at: www.independent.ie/irish-news/celebrity-chef-paul-rankin-blames-flag-protests-for-belfast-restaurant-closure-29155782.html (8 February 2015).