Master Bridgetower, son of the African Prince, who had lately figured so much at Bath on the violin, performed a concerto with great taste and execution.

— The Times, 20 Feb, 1790.

The late eighteenth century was an important period for the articulation of the ideas of democracy, the rights of the individual and the injustices of inequalities of wealth and power. But if in the early nineteenth century Lord Palmerston is reputed to have said that “there is no such thing as permanent friends only permanent interests”, he might also have added there is such a thing as a permanent, self-serving flexibility in ethics.

It was not merely that the old landed interests across Britain and Europe held onto power and defended it mercilessly, but when those who overthrew that power in America and France had power themselves, they behaved no better, particularly towards Black people.

Settlers in America waged the War of Independence in 1775 over unfair taxes levied by the colonial power, Great Britain, but showed little concern over the existence and condition of the slaves on the tobacco and cotton plantations. As the French fought for ‘liberté, égalité et fraternité, and aristocratic heads rolled, other bodies remained bound and chained for export from West Africa. Nine years after the French revolution, the 1798 slave uprising in San Domingo, otherwise known as the Haitian revolution, shared the same revolutionary objectives, but the new French government was not prepared to end slavery; the maritime bourgeoisie had too much to lose by recognizing the human rights of Africans. Frequently otherwise at odds with France, Britain supported France in putting down the insurrection. Revenues would decline and spheres of influence shrink if “the black Napoleon”, Toussaint L’Ouverture, were to prevail. The triangular trade of manufactured goods, enslaved human labour and raw colonial produce had been too important to capitalist accumulation in Western Europe.1

Even as a Frenchman, Victor Schoelcher and an Englishman, Thomas Clarkson, were winning popular support for the moral case for abolition, they struggled to be heard above the demands of the West Indian interests for the protection of their investments.

If the creation of the West Indies as plantation societies with imported populations (after the original Amerindian inhabitants had been largely exterminated) was the main legacy of the enterprise of sugar and slavery, there were also lasting impacts on British society and culture. Fortunes were made (and lost) and a good many “noble” families and stately country houses such as the Lascelles and Harewood House outside Leeds in Yorkshire have their origins in the profits of slave-grown sugar and the slave trade.2 Along with these architectural displays of landed wealth, one of the most striking fashion statements for the well-to-do lord or lady was the little black boy who would be in attendance at social functions. In a good many paintings of the landed gentry from the late seventeenth to the late eighteenth century they appear as mascots or pets. Mostly (but not always) shown in deferential poses, these black children reflect a duality in eighteenth century attitudes to race, namely that the African was lauded for his appearance in youth but mistrusted for the threat that he might pose in adulthood. The benign presence of the Negro boy emphasises of the absence of the Negro man.

Young black boys and girls were part of a vogue for exotica that also included the use of fabrics from the Far East as well as perfumes and spices from Asia and the Middle East. Dressing the servant in finery reflected the ample means of the household in which he appeared.

Among the most notable paintings in this manner is Captain Graham in His Cabin by William Hogarth. Painted in 1745, the canvas was intended to celebrate the capture of valuable cargo after Graham had launched a raid on a squadron of French ships outside Ostend in Belgium. The conquering hero is the central focus of the image and his imperious pose – back straight, leg outstretched and gaze firmly trained on the viewer – denotes a man of stature, self-confident in his privileged place in society. Clad in a gold brocade waistcoat, breeches, stockings, white cravat and a red fur-lined cape, Graham is puffing on a long tapered pipe and he affects something of a dandyish demeanour in the way his head is cocked slightly to the side. On a chair in front of him is a small dog, rearing up on its hind legs, head practically drowning in Graham’s cascading white wig, and standing right behind the animal is a Negro boy. He is holding a small naker (kettledrum) under his arched left arm and is beating it with a straight wooden stick.3 The young black is an elegantly attired music-maker. Both the dog and the servant are presented as subservient references to the master, who dominates the picture. The pet, by dint of the wig, is made lordly in a ridiculous way. The boy is decked out in a yellow waistcoat and a blue velvet jacket studded with large gold buttons, a brilliant red cravat round his neck, a beige cap upon his head. Like the Captain, he also has a long pipe hanging from the side of his mouth. Negro boy and dog appear as playthings fashioned in the image of the master and, as much as the painting tells us about hierarchy and the place of blacks among those with power, it also connects to other images of black musicians in British society. Indeed, Graham’s servant vividly recalls the mezzotint engraving of the Negro tambouriner in the Coldstream guards discussed in the previous chapter. It is tempting to think that the difference is that Graham’s player is now outside the military environment, but the location for Hogarth’s painting is a ship, possibly part of the fleet used for raids on the French, which suggests that black drummers were used on British war vessels as much as they were in infantry units.

Another common denominator in these images is the headgear of the two black figures. The Coldstream Guards drummer wears an elaborately designed wrap modelled on a turban and the Graham drummer sports a puffed, voluminous, rounded hat whose provenance is not easy to pinpoint. It may be European. It may be Middle Eastern. Both look exotic. The sophistication of their clothing reveals the convention of adorning slaves in ways which would have enhanced their function either as musicians performing practical duties in the armed forces or entertaining polite society in the drawing room or parlour.

Consider the case of David Marat. He was a servant who absconded from his ‘Master’, one Edward Talbot, known to reside in King Street near Soho in central London. From a broadsheet advertisement issued in early 18th century we learn this:

A black about seventeen years of age, with short wooly hair. He had on a whitish Cloath livery, lin’d with Blew, and Princes-mettal Buttons, with a turbant on his head. He sounds a trumpet.4

Again the contiguity of the exotic and a black musician. Whatever his musical ability, David Marat also reflects the trend of dressing Negroes, or more precisely young Negro boys, in non-western headgear that creates a kind of Ottoman-African continuum in eighteenth century Britain.

If such figures existed on the fringes of cultural history, they nonetheless make the point that black people were playing instruments in various circumstances in the eighteenth century. They were both seen and heard.

Apart from the battlefield and the parade ground, the other setting in which black musicians were present was the street. The picture that emerges of life for Africans in Britain, if they did not have the security of an army or household post, was of a hand-to-mouth existence. For the most part, apprenticeships do not seem to have been offered by distrustful masters, so hawking and entertaining were prevalent trades.

One of the most popular outlets was bare-knuckle fighting. Tom ‘The Moor’ Molineaux, Bill Richmond and James Wharton were among the celebrated black prizefighters who plied their trade in the capital, but for those who were not blessed with the constitution and stamina of a successful pugilist (who had to endure bouts that could last well over an hour), there was the chance of amassing pennies by finding a ‘pitch’, throwing a hat on the pavement and singing songs or ‘scraping the catgut’ i.e. fiddling.

These street musicians should not be seen in the same context as modern day buskers, whose performances have a degree of novelty because they take place in an age when music is widely available by way of recorded media and broadcast communications. As noted in the previous chapter, news and song were much more closely aligned in the days when minstrels and itinerant players wandered the land.5

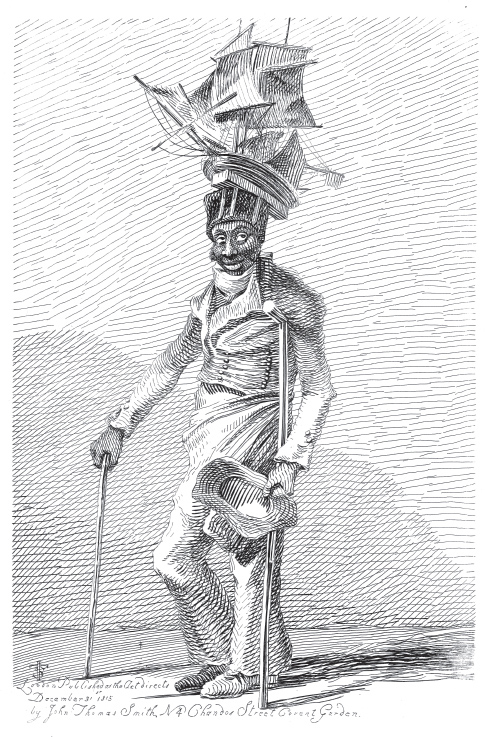

For sheer visual panache, it seems that few black street players could match Joseph Johnson, who worked in rural villages and market towns such as Romford or St. Albans. He sported a model of a ship, the HMS Nelson on his head and cut a striking figure as he performed a number of patriotic songs such as “The Wooden Walls of Old England”, a song that references a naval ship.6 A drawing of Johnson (1817) gives him something of a circus performer’s curiosity by virtue of the ship on his head, as if he was a mythical giant sea dweller who had risen from the depths of the ocean, a dark Neptune carrying mast, sail and hull onto dry land.7

There was a more prosaic reason for the elaborate prop. Johnson was a former merchant sailor who had sustained injury during his working days, as indicated by the wooden crutch under his left shoulder and a walking stick in his right hand. Because his injuries were suffered in peace-time, he was given no pension. Johnson, facing destitution, had no choice but to take to the streets. The existence of black beggars in Britain in the eighteenth century reflected the precarious nature of life for people of colour. Johnson displayed a pragmatic resourcefulness. Whilst the picture with a ship on his head may have freak-show connotations, it was actually part of the tradition of Jonkunnu masquerading in the West Indies, and it becomes a memento of ingenuity when the eye is directed towards the crutch that is holding him up.

Disability is the common denominator shared by Johnson and another musician who was well known on the streets of London. Billy Waters was an American-born Black, a peg-leg fiddler who plied his trade on the streets around Covent Garden. According to a broadsheet from the 1800s, he was maimed while in “His majesty’s service”, for which he did receive, unlike Johnson, a modest pension. Pictures of Waters show a flamboyant character who, like Johnson, had an eye for millinery. His broad-brimmed cocked hat, its central peak rising high into the air, streamed with ribbons and feathers, the gaiety of which was enhanced by an act that would see the fiddler discard his wooden peg and dance on one leg.8

Waters would sing as well as “scrape the catgut” and from his pitch just outside the Adelphi on the Strand, near Charing Cross in central London, he won the hearts of many passers-by. Whilst he fiddled and sang outside of theatres for most of his life, he actually crossed the threshold of the Adelphi, one of the most modish theatres in the capital, when he appeared as himself in the stage adaptation of Pierce Egan’s Life In London (1821). This was a book that over the next hundred years sold 300,000 copies.

JOSEPH JOHNSON, DRAWN FROM THE LIFE BY JOHN THOMAS SMITH, DECEMBER 31ST, 1815.

From Vagabondiana, or Anecdotes of Mendicant Wanderers through the Streets of London (New Edition, 1874)

His standing among the lower social orders was cemented by his election as “King of the Beggars” before his death. When he passed away in 1823 there was a funeral procession in Covent Garden that drew large crowds. His sending off, as depicted in the press, acknowledged him as part of the traditions of popular entertainment that reflected the seamier side of life in Georgian Britain. Broadsheet illustrations of the event show that there was dignity if not grandeur bestowed upon the deceased, whose casket was covered in a large velvet drape upon which were placed his fiddle and hat. Sewn to the drape over Waters’ coffin was the legend “Poor Black Billy”, and whilst this signals the affection in which he was held, it reminds that he was predominantly defined by his race. Behind the coffin there is a man with no legs who is being carried in what appears to be a sedan chair. Ahead of the pallbearers is a group of seven, most of whom sport black hats with long trailing fabrics. Right in the middle of that group there is a black man with flowing, striped trousers. He is barefoot and wears a turban. The Eastern or Moorish style of the mourner is a reminder that Waters was still living in a time when Africans in Britain were elided with the exotic.

In the background there stands a row of buildings, one of which bears the sign Beggar’s Opera,9 the popular stage show that satirised the upper-classes by casting them in the clothes and culture of the demi-monde of the London poor, “pickpockets, prostitutes and lawyers”, indicating that criminality existed at all levels of society, high and low. It was one of the earliest comic operas, staged in 1728 with a libretto by John Gay and music by the German-born Johann Christoph Pepusch. Its music drew on “already familiar street ballads.” The reference to this opera in the engraving of Billy Waters’ funeral signals his place in the lineage of British entertainment.

Despite the daily hardships it endured, the working class Black community in 18th century Britain was well known for its lively social life, and it is likely that the fiddlers and horn players who took part in the “Black hops”or “Black balls” in city backstreets, were a mixture of civilians and ex-military personnel. Here Negroes “drank, supped and entertained themselves with dancing and music.” Indeed, entertainers such as Waters attained such popularity that they influenced their white peers. Because of the crowds that black musicians attracted they prompted others who were not from Africa or the West Indies to black up in order to grab the browne.10

*

There were also black musicians who moved in very different circles. Whilst Billy Waters and Joseph Emidy (1775-1835) played the same instrument, it was not appropriate to say that the latter was a fiddler. He was in fact a virtuoso violinist, composer and tutor who became the toast of classical music audiences in the South West, in Truro, Cornwall.

There had been a black presence on the South-west coast since the middle of the eighteenth century, primarily through the arrival of people of colour in the military, including some who were musicians. There were black drummers in the 29th Worcestershire Foot, which was stationed in Plymouth, Barnstaple and Bideford between 1759 and 1843, and also in the 46th South Devonshire Regiment of Foot. Devon was a focus for military recruiters keen to sign up ex-slaves who came to Britain from America after fighting for the motherland in the War of Independence in 1775, for which they were promised freedom. There were precursors even before this. In 1688, the Dutch Prince, William of Orange, landed at Brixham, South Devon before he set off on a march to London to claim the English throne from James II. To bolster his army he travelled with 200 African slaves, former labourers on Dutch plantations in America. Some may have absconded en route.11

In any case, the growth of a black community in Cornwall and Devon coincided with an increased naval presence in Falmouth and the continuing but declining trade links with New World territories such as the West Indies and South America and Old World states like Portugal. Lisbon was the home of the man who would become the most renowned black musician in Cornwall. Born in Guinea but sold to Portuguese traders who took him to their country after he had been a slave in Brazil, Joseph Emidy showed such talent on the violin as a boy that he made a name for himself in Lisbon’s very fashionable opera house by the time he was a teenager. He caught the ear of a British naval commander, Sir Edward Pellew, who instructed his men to kidnap Emidy for use as a fiddler aboard his vessel, The Indefatigable, in 1795. For several years he was forced to “climb down” musically, playing jigs and reels for the entertainment of a raucous crew rather than Haydn and Mozart for Portuguese polite society.12 To the trauma of violent removal from his home was added the indignity of artistic degradation. “Scraping the catgut” was the lot of many Africans who found employment on ships in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, either as fiddlers or drummers, whose purpose was to entertain crew members with ditties or keep time with percussion instruments during the singing of shanties. This was intended as a distraction for crew members who had to contend with boredom and homesickness as well as the lack, on occasion, of exercise. Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851) shows such a scene. On board the Pequod, French, Maltese, Sicilian and Icelandic sailors are just some of an international crew that pitches in with verses, but it is Pip, the young Negro cabin boy, the ‘blackling’, who is given the task of setting the beat for the uproarious jig that is danced by the men.

Pip! Little Pip! Hurrah with your tambourine.

Go it, Pip! Bang it, bell-boy! Rig it, dig it, stig it, quig it, bell-boy! Make fireflies; break the jinglers!13

Note how closely Melville’s language chimes with the lexicon developed for the British military musicians of African descent mentioned in Chapter 1. The name for Pip’s tambourine is the “jingler”; the Turkish percussion played by 18th Century Negro drummers was known as the “jingling Johnnie”.

This was the kind of life Emidy had to live when he was forced to sea. However, after Pellew left The Indefatigable in 1799, Emidy was allowed to go on shore where he settled in Falmouth. It didn’t take long for him to make an impression, since Falmouth and neighbouring Truro were becoming fashionable areas for socialites. Emidy was appointed leader of the Falmouth Harmonic Society, with whom he performed a wide variety of symphonic and chamber music, and also began teaching and composing.

One of his pupils, James Silk Buckingham, took some of Emidy’s original music to an impresario in London and there was talk of the violinist coming to the capital to play. Nothing ever came of this; there were apparently misgivings over the suitability of a black musician in the drawing rooms of the country’s elite. It may also have been because Emidy was described as “the ugliest Negro I have ever seen”, so he did not fulfil the criteria of being ornamental, like the Negro boy in the painting referred to above.

Emidy died in Truro in 1835 at the age of 60, survived by a wife and several children. His gravestone in the town’s Kenwyn churchyard bears a moving epitaph:

Devoted to thy soul inspiring strains, Sweet Music! Thee he hail’d his chief delight. And with fond zeal that shunn’d nor toil nor pain his talent sear’d and genius mark’d its flight in harmony he liv’d, in peace. Took his departure from this world of woe. Here his rest til the last trumpet’s call, shall ‘wake mankind to joys that endless flow’.

Emidy’s story may have ended somewhat sadly, given that his talent was not given the chance to shine on a national scale, but the mere fact that he managed to overcome the adversity of his early years, surviving the trauma of a kidnap to rise to a level of considerable prestige in Cornwall, is a sign of admirable resilience. His place in the pantheon of South West cultural figures is an important one. Had he been able to establish a permanent base in London and enjoy the favour of more of the key powerbrokers in music, he may have gone even further in his career. He nonetheless remains a black Cornishman of note.

George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower (1779-1860) did attract patronage and move in the right metropolitan circles. His story was one of an artist who rubbed shoulders with the aristocracy, enjoyed Royal patronage, and, most significantly for the history of black music in Britain, showed himself worthy of a seat at the high table of European composers such as Haydn, Viotti and Beethoven. Yet what linked Bridgetower, a child prodigy who showed aptitude for the violin as a nine-year-old, to the black mourner at Billy Waters’ funeral was the attire of his father, John Augustus Frederick Bridgetower. The association of people of colour with exotica in the era was widespread:

Appeals to the curious were made by parading minorities of all kinds [ethnic, young, old, handicapped]. Thus the young mulatto violinist George Polgreen Bridgetower was marketed as the ‘son of the African Prince’; his father dressed in extravagant Turkish robes.14

Known as an “Abyssinian from the West Indies”, Bridgetower senior married a Polish woman, while living in Barbados in the early 1770s. It is likely that he was taken to the British colony as a free man serving on a merchant ship, and whether of his own canny devising or not, the sobriquet of “African Prince” was attached to him as he made his way to Europe. He was helped by the law passed in 1772 that decreed that slaves would be free as soon as they set foot in England, even though they could be reclaimed in the West Indies. It was thus in Bridgetower senior’s interest to make his way to the Old World, to reach which he crossed many national borders. George was born in Biala in Poland in 1778 or 1780, and accompanied his father to Austria where he became a page to Prince Nicholas Esterházy, and it was during this time that George first displayed a natural talent on the violin that was quickly identified by music teachers who gave the boy formal lessons. It may have been, though it is not proven, that one of his earliest tutors was Franz Joseph Haydn.

By the age of nine, Bridgetower was playing at a sufficiently high standard to make his debut in Paris. He was presented as a “jeune negre des colonies” when he performed at the Concert Spirituel on 13 April 1789. The consensus was that this was a precocious, prodigious talent. Thereafter, he lived in the other major hubs of European classical music – London, where he was taken under the wing of the Prince of Wales and accommodated at Carlton house, and in Vienna, a key turning point in his musical education. It was there that Bridgetower developed a close friendship with Beethoven who tutored the young violinist and wrote a sonata for him, a notoriously demanding piece that, as a mark of respect, initially bore his name. But the two men fell out, apparently over the affections of the same girl, and Beethoven crossed out Bridgetower’s name on the original manuscript and replaced it with that of Kreutzer.

However, Bridgetower was more than a footnote to Beethoven, since his rise coincided with major developments in the work of the “serious” composers of the day. The resources of the orchestra – strings, woodwind, brass, horns, percussion – are taken for granted as the tools with which all manner of pieces have been written for the past two hundred years, but concertos and sonatas for solo instruments gained greater currency from the 1750s onwards. In particular, Bridgetower’s career dovetailed with the rise of the violin as the most important orchestral instrument in classical music. As a solo instrument capable of producing a quite vocal-like beauty, the development of the sonata form gave skilled players of the violin new prominence, bringing to the fore the role of the virtuoso who could play lines that were more and more demanding. Beethoven was inspired by musicians who could play their instruments to an exceptionally high standard, which is why the violin sonata was written for Bridgetower, because of his ability, or rather as a challenge to it.

Falling out with Beethoven did not halt the success that Bridgetower enjoyed. There were a string of stellar performances in Bath, Bristol and London, where he took part in recitals organized by George III’s court musician, Christopher Papendiek. His most triumphant appearance was a concerto by Feliks Giornovic performed between the opening and second act of Handel’s Messiah at the Drury Lane theatre on 19 February, 1790. A very favourable review was published in The Times the following day;

Master Bridgetower, son of the African Prince, who had lately figured so much at Bath on the violin, performed a concerto with great taste and execution.15

Bridgetower held a number of very notable positions such as first violin for the Prince of Wales Band, the Covent Garden Lenten Oratorios and the Italian Opera at Haymarket. He was also a member of the Royal Society of Musicians.

The prestige of these appointments underlines the fact that the “servant boy groomed in Turkish attire” became a major fixture on the European classical music scene. As a nine-year-old violin prodigy who, in the common parlance of the day, was a “mulatto”, Bridgetower was an artist who performed at a turning point in the history of classical music, playing pieces that stretched the sight-reading ability of the most highly trained musicians.

As well as his achievements as a soloist, Bridgetower was also a composer, and although there is no comprehensive record of his output, manuscripts of some pieces he wrote have been preserved. One ballad that was penned in 1812 for voice and piano was called “Henry”. The piece was sung by Miss Feron and was eternally dedicated “with permission” to the Princess of Wales – a reminder that patronage was paramount during Bridgetower’s career.

A year before “Henry” was written, Bridgetower was awarded his Bachelor of Music degree at the University of Cambridge and for the next three decades he continued to accept engagements in European capitals such as Rome, where he stayed in 1825 and Vienna (where he had previously studied) and to which he returned in 1845. Things evidently became more difficult for him when he seems to have lost royal support after the death of George IV, and the final years of his life remain shrouded in mystery. He died of synochal fever in Peckham, south London in 1860.

Although the story of Bridgetower is largely defined by his precocious talent, the issue of race is impossible to ignore, primarily because as a violinist and composer he entered a social milieu where people of colour were conspicuously absent. His youth was passed in a world where slavery still existed and where racism began to adopt a distinctively pseudo-scientific mode of discourse about the inferiority of Africans. Such twisted rationales made complete sense to those who sought reasons to justify slavery and colonial rule. If blacks were lesser beings than whites, then they should not enjoy the same rights.

There was even a school of polygenesis in the seventeenth century that argued that blacks were a kind of organic link between whites and primates in the evolutionary chain, while Sir William Lawrence, a proponent of phrenology, would, over a century later, earnestly compare “the Negro structure” to a monkey’s.16 Edward Long’s The History of Jamaica (1774), drew similar conclusions on the basis of black physiognomy:

There are extremely potent reasons for believing that the White and Negro are two distinct species. Instead of hair, black people have a covering of wool, like the bestial fleece.17

The image of the bestial fleece reinforced the idea of the proximity, if not common identity of Negro and animal – an image that chimes with Iago’s description of Othello as “an old black ram”. Hence when an African in Britain was described in a broadsheet advertising an absconded “black about seventeen years of age” with “short wooly hair”18, common parlance coincided with academic writing. When a black man was described as sporting a “Turbant on his head” it was really due to the fashion for Turkish attire, but for anybody who followed Long’s form of “science” it may have been a proper accoutrement for a Negro because it kept the unseemly “bestial fleece” from view.

Such imagery continued into the twentieth century. If the term “fuzzy”, used liberally by writers such as Rudyard Kipling, echoed the earlier “woolly”, then it is interesting to see how a great black artist, Nina Simone, references the roots of such language in the opening verse of her 1965 masterpiece “Four Women”, where she has the matriarch Aunt Sarah wearily declare: “My hair is woolly.”19

Edward Long to Nina Simone is not an incongruous leap when one notes that the issue of “good” hair is still contentious today, and that the psychological scars inflicted by the text of the former and displayed in the music of the latter are by no means fully healed.

A Van Dyck or Hogarth painting in which a Negro boy or servant girl is cast in an ancillary role, under the command of a white mistress or master, conveys a vivid image of powerlessness. Combine that with the kind of overt self-denigration that is recorded in the bible by the Queen of Sheba – “I am black but comely” – and it is not surprising that the Negro has had to struggle to assert his or her aesthetic value in white society.

This is why Bridgetower’s entry into and deft negotiation of the upper classes of 18th century Europe, among those for whom bodily attractiveness, sartorial finesse and proper manners were of the utmost importance, was particularly impressive. A good command of several of the major European languages was also a considerable asset and both Bridgetower and his father were known for their multi-lingual skills. Perhaps even more tellingly, both were noted for their “beauty of person”.

That Bridgetower was a handsome mulatto and not a one-legged black man like Billy Waters, was an advantage, and no doubt made him easier to accept because he was not seen to embody any threat. Even so, Bridgewater’s position brought a level of attention to his colour that could not be played down. He was talked about in an era when few other black men managed to capture such attention. One such was Julius Soubise, born in 1754 in St. Kitts, one of the oldest British colonies in the West Indies, who was brought to England as a ten-year-old in the care of Kitty, the wealthy Duchess of Queensberry. Under her tutelage, he became a fencer and equestrian, but above all a man-about-town famed for his dandyish ostentation – he was known to use the most overpowering perfumes. Although he enjoyed the enduring favour of the Duchess, he had to flee to India to evade the law when he was accused of the rape of one of her maids.

Bridgetower, by contrast, was respectable and respected as an artist rather than known for his narcissism and stylistic excess. No greater symbol of the success of the “young African Prince” can be found than his appearance at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1790. He played a concerto by Giornovic which won favourable notices in national newspapers and magazines. This was only fourteen years after the performance of Airs and Ballads in The Blackamoor Wash’d White or A New Comic Opera. This was a transition from blacks as passive objects of ridicule to active performers in one of the most iconic theatre spaces to be found in Britain. After his debut in Paris, a review appeared that did not skirt around the issue of prejudice and presented his performance as a rebuttal of those who would not have considered his kind worthy of playing such refined music. Le Mercure De France stated unequivocally:

It is one of the best answers that can be made to the philosophers who want to deprive those of his nation and his colour of the opportunity to distinguish themselves in the arts.20

While the positive nature of the statement is clear enough, the detail warrants further discussion. What exactly was Bridgetower’s nation, or indeed his nationality? Here was the son of an “Abyssinian from Barbados” and a Polish woman. He was born in Poland and went on to reside in Paris, London, Vienna and Dresden. To talk of Bridgetower as a representative of a nation clearly references a nebulous Africanness, rather than any specific country of origin. What was important was whether one was a freeman or a slave, or whether the economic constituency in which one moved, either in liberty or in bondage, was the West Indies, America or Britain.

Ignatius Sancho, Billy Waters, Joseph Emidy and George Bridgetower form a quadrumvirate of black musicians in 18th century Britain and are notable for the wide stylistic and social spectrum they covered. Between them they played street music among lowlifes and classical concerts for royalty. Emidy and Bridgetower travelled widely, performing in London, Bath and Cornwall, as well as in many major European cities bringing something substantial to European and British concert music. They made the point that people from Africa or the Americas could do more than scrape catgut on street corners. Perhaps of the three, Bridgetower has had the greatest legacy, as film-makers, musicians and poets have been drawn to his story. There is the film, Immortal Beloved (1994) which portrays him with Beethoven, the film, Mulatto Song (1996), directed by Topher Campbell, Rita Dove’s narrative poem, Sonata Mulattica (2009) and a jazz opera, Bridgetower – A Fable of 1807, by Mike Phillips and Julian Joseph.21

Joseph Emidy has more recently been the subject of a multi-media collaboration between composer Tunde Jegede, film-maker, Sunara Begum and dancer-choreographer Ishimwa Muhimanyi in He Who Dared to Dream (2014).

Notes

1. Madison Smartt Bell, Toussaint L’Ouverture: A Biography (Vintage, 2008).

2. Simon Smith, Slavery and Harewood House, BBC Leeds 24.09.2014

3. Naker is derived from the Arabic naquara.

4. The advert for David Marat was reprinted in Roots of the Future, Ethnic Diversity in the Making of Modern Britain (CRE, 1996).

5. Mayerlene Frow, Roots of the Future.

6. The Wooden Walls of Old England is also a common name for many pubs up and down the country.

7. The source of the image of Joseph Johnson is Vagabondiana, or, Anecdotes of mendicant wanderers through the streets of London (1817).

8. Frow, op. cit.

9. The Beggar’s Opera ran for 62 performances, the longest run in theatre at the time, after premièring at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 29 January, 1728.

10. Frow, op. cit., p. 21.

11. Black Cultural Archives, Ephemera 271, Cornwall, 1800s.

12. Black Cultural Archives, 5/1/72 Joseph Emidy.

13. Herman Melville, Moby Dick (1851, Penguin ed.) p. 174-175.

14. Clifford D. Panton, George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower, Violin Virtuoso And Composer Of Colour In Late 18th Century Europe (Edwin Mellen, 2005) p. 31. Much of the information here is courtesy of Panton’s biography.

15. Panton, George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower…, p. 39.

16. William Lawrence, Lectures on Physiology, Zoology and the Natural History of Man (J. Callow, 1819) p. 363.

17. Edward Long, The History of Jamaica: Or General Survey of the Ancient and Modern State of That Island; with reflections on its situation, settlements, inhabitants, climate, products, commerce, laws and governments (T. Lowndes, 1774).

18. The advert for David Marat was reprinted in Roots of the Future, Ethnic Diversity in the Making of Modern Britain (CRE, 1996).

19. Nina Simone “Four Women” featured on the LP, Wild Is The Wind, Phillips, 1966.

20. Panton, op. cit., p. 17.

21. Wikepedia.