The first thing that these black troops do when they get into camp is strike up some of their unearthly tunes. They have been known to fashion old tin biscuit boxes into a species of wind instrument.

— War correspondent on Sudanese soldiers serving in the British army, 1890s

A well dressed, curly-headed, dark little boy, holding a small violin in one hand and his marbles in the other.

— Early description of the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 1882

As outlined in Chapter 1, the British state had been ready to use black musicians in its armies, with black drummers famed for their pageantry and time-keeping on the parade ground and marching to battle. By the mid-nineteenth century, when the focus of empire had moved to India – and at its peak the British maintained an army of close to one million soldiers – the ruling class cannot have been pleased to discover that British music was being used in a revolt against empire. This occurred in 1857 when the sepoys recruited to the British army in India mutinied over what they believed was disrespect for their religious and cultural practices – the greasing of cartridges with beef and pork fat – and joined battle with British units in Uttar Pradesh. Song was used as a weapon of war by the sepoys, whose command of British culture was shown in their assimilation of the anthems of the day. The reports of war correspondents provide fascinating details:

It is ironic to find them persistently playing British marches ‘as if in defiance’. At Lucknow 10,000 sepoys besieged British troops. They gave a regular morning performance plus an occasional evening encore that included The Standard Bearer’s March, The Girl I Left Behind Me, See the Conquering Hero Come and concluded with God Save The Queen. The bands played the besiegers into action and it must have been a bizarre and fearsome nightmare to see the sepoys, ragged badmarshes and the picturesque retainers of the thalukadars [barons] sweeping in, like so many demons in human form, to some well loved English air.1

As Lewis Winstock has shown in his revealing study, Songs and Music of the Redcoats, this was a potent sign of the psychological and cultural complications that flowed from the expansion of England and the growth of its colonial dominions. Here were former subjects of the realm, whose task had been to combat local resistance to exploitative commercial activity, claiming a British heritage and its romantic and patriotic songs on their own terms. In the context of the mutiny, the songs became bitter mockery. If brown “demons in human form” really wanted to wage psychological warfare against white soldiers, then a verse or two of “See the Conquering Hero” would have unnerved even the most battle-hardened infantry, as the sepoys presented a “bizarre and fearsome nightmare”.

Insurgent sepoys playing “Send Her Victorious, long to reign over us” was an early example of writing back to the Empire, but it also indicates how song was an important part of the British military tradition. British regiments chronicled events in songs that often aired their feelings about their adversaries. For example the “Ceylon Ballad” evoked “the black rebels” of the Indian Mutiny, but granted them a certain respect for their valour in battle.

However, British imperial songs often articulated crudely racist sentiments, employing derogatory terms to describe the natives in various territories. A popular song at garrison concerts and officers’ parties was “Paddy Among The Kaffirs”, yoking the Irish and Black South Africans in common insult. South Africa, which produced fine black choirs, several of which visited Britain in the 1890s, was the site of a protracted and bloody conflict at the end of the nineteenth century, because it was hotly contested by the British, the Dutch and the Zulu nation. To achieve imperial control, the British army fought first against the Zulu Kingship in 1879, and against the Boers of the South African Republic in 1880-81 and again in 1899-1902. Prior to battle, British soldiers sung racially abusive songs such as “Razors in the Air” against their Zulu adversaries:

Don’t you hear de niggers now?

All dem nigs is cut to death

Soon we’ll make us darkeys one2

Chants such as these are shocking for many reasons. The alignment of racial taunt and graphic threat of violence remain familiar to anybody who has either stood on a football terrace or been confronted by skinheads or fascist boot-boys on the streets of postwar Great Britain. There is a clear parallel between political hooliganism and the tradition of insults and intimidation in the history of the British army. There are reports of some white British troops assaulting native recruits in colonial Africa and India for having the audacity to lend their voices to patriotic British tunes.

Racism notwithstanding, music was also a vital part of military recreation and entertainment. Tours of duty, especially in India, were often very lengthy, and the music played by regimental bands was intended to lift the spirits of troops and counter boredom and indiscipline. Inevitably, elements of local music were picked up by British bandsmen, although they were often dismissed for their “crudity”. Even so, the Queen’s Regiment, stationed in Calcutta in 1885, had a composer called J. McKenzie Rogan who based several marches on Indian themes. Another popular song was “Zachmi Dil, The Wounded Heart”, which came from the Pashtuns of Afghanistan. It was a very candid homoerotic lament.

There’s a boy across the river

With a bottom like a peach

But alas – I cannot swim.3

This tune was later adapted as an unofficial march by the North Staffordshire and Liverpool regiments. Global cultural history is nothing if not complex, but to think that hard-as-nails squaddies in the British army, an institution that once punished homosexuality with a court-martial, were playing an Indian ode to a fruity fundament, underlines how the Empire could be subverted in the most surprising ways.

Tempting as it is to dismiss the phenomenon of “Zachmi Dil”, it is nonetheless a sign of how Britain was affected by its engagement with foreign cultures, and not always being able to control the direction of the flow as tightly as it would have liked. What observers called “Native Music” was never segregated from British ears abroad, though the first instinct was to disparage. Of particular offence to European ears was the apparent problem afflicting Sikh brass bands, whose style sometimes deviated from those of Albion. According to a German officer called Sauer, these bands produced “the most discordant… vile music I had ever heard.” British officers explained this as the result of the physical inferiority of the Sepoy musicians. It was both a matter of style and puff. As one officer explained: “The natives are generally slow in adapting their ears to European strains. They seem not to possess that strength of lungs necessary for filling our wind instruments.”4 In the dispatches of war correspondents of the period it is evident that the Indians and Africans who played music in the British colonial army were viewed with a mixture of passing curiosity and begrudging admiration. It was noted by observers that Sudanese who were recruited by the British army in the 1890s had a desire to make music at all available opportunities, but what they played still seemed strange and disconcerting to European ears:

The first thing that these black troops do when they get into camp is strike up some of their unearthly tunes, and in the absence of normal appliances they have been known to fashion old tin biscuit boxes into a species of wind instrument.5

Improvisation such as this, making music without conventional musical instruments, resonates with developments in the West Indies in the 20th century. The precursor to the steel band in Trinidad was the percussion group in which household implements and labourer’s tools were all deployed to create rhythms for carnival parades. The biscuit tin was a much-favoured item in these groups.

But it was not just in the making of unconventional instruments out of serendipitous materials that African and European cultures intersected. The lyre is one of the oldest instruments found in both Sudan and Egypt, with origins as far back as 3000 BC. In Victorian times there were versions of it that provided a fascinating reflection on the way material objects coursed through channels opened up by imperialism and invasion. Some lyres had a circular sounding board with a horizontal bar to which were tied various charms that ensured that the musician could be heard and recognised as he made his way from one recital, mostly at religious ceremonies, to another. Among the charms were beads, bells, amulets and cowrie shells sourced locally, as well as metal levers and cogs culled from steam trains, and ha’penny coins from England. The industrial items and currency most probably denote the interaction of British workers and soldiers with Africans, either employed in civilian or military life.

Among the most musically active of the many “native” musicians conscripted to British colonial regiments were Egyptians and Sudanese, who saw action in Khartoum in the 1890s. Their bands featured a wide range of horns and percussion instruments, though the soldiers were also known to chant heartily on marches, including popular music hall songs taught by their colleagues from England. There was also the 15-piece Sierra Leone Frontier Police Band which, in 1897, greatly impressed at Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations in London. In its ranks was a soldier known as “Little Tom” who was awarded a prize for his bugling. What all these bands demonstrated, with their eclectic repertoires, was how cultures around the world were intermingling in the Empire. Here were units of Africans, enlisted by the British, playing a range of songs that included Arab tunes that had sometimes been arranged by Italian bandmasters. Another piece the Sierra Leoneans had taken to their hearts was “Oh Dem Golden Slippers”, which, as noted in the previous chapter, was the parody that James A. Bland wrote of “Golden Slumbers”, one of the Negro spirituals performed by the Fisk Jubilee Singers. A slave song, born in the realm of the sacred and dragged into the secular world, now linked outposts of the British Empire and Africans to their descendants in the New World.6

The idea of African-American music travelling to Africa via Britain’s armed forces makes the point that even the military apparatus that underpinned Empire was by no means detached from culture. The songs played by British regiments are thus a vital if somewhat overlooked part of the bigger story of Black music in Britain, and their existence underlines the growing complexity that comes with the expansion of a country beyond its natural borders. Just as words from Indian languages became an integral part of standard English – curry, pyjama, bungalow – it is evident too that melodies and rhythms heard in India and other parts of the Empire must have caught the ear of any bandleader with a modicum of curiosity. If “Zachmi Dil” could end up as a march, then it is likely that other compositions, or at least fragments of them, may have been adopted by units who returned to Britain after a tour of duty. Sounds travel.

*

While the Fisk Jubilee singers, with their sober garments and serious demeanour, presented a wholesome image of the black artist, the raucous drumming of Sudanese soldiers and “half-caste” bandsmen enlisted in the British army in Africa and India were at the other end of the spectrum. Between them they show the vastly differing circumstances in which black musicians operated during the time of Empire.

A marker of a significant change in the artistic scope of those who followed is to be found in a dramatic encounter that occurred in 1905, four years after the death of Queen Victoria. The meeting took place between two men who symbolized a confluence of the worlds of letters and music. One was black, the other white. They sat in an elegant drawing room and drank tea.

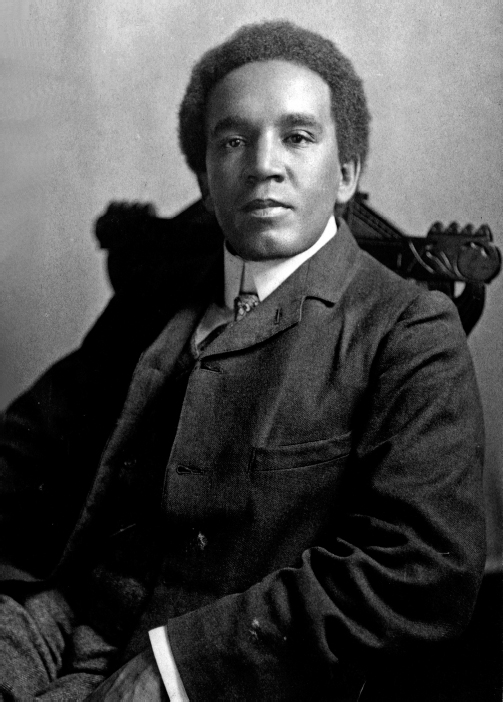

The fair-skinned Englishman was Ernest Hartley Coleridge, the grand nephew of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. His “dark complexioned” acquaintance was Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, the first black British composer to achieve both national and international fame. The twinning of the two names was not coincidental, but reflected the fact that the father of the latter, Daniel Hughes Taylor, a West African, was an avid reader of the poetry of Coleridge, and had paid tribute to him by using his surname as the middle name of his first-born son. The musician was intended to carry something of the spirit of the poet.7

Hence the meeting between Coleridge-Taylor, the composer, and the poet’s descendant both brought personal and wider cultural history into focus. It was not small talk that the two made, either. Ernest Hartley Coleridge read his famous antecedent’s poem “Kubla Khan”8 and the composer subsequently agreed to set the words to music, which was completed and performed on several occasions in 1906. The poem became a rhapsody for soloist, chorus and orchestra and was heard at the Handel Society in London and the Scarborough festival.

It is easy to see why the poem captured the imagination of Coleridge-Taylor, given that it told of a mythical, fantastical palace in strong, bold, rhymes – “it was a miracle of rare device/A sunny pleasure dome with caves of ice” – and the poem made reference to music in the “dancing rocks” and “the damsel with a dulcimer”. The line “Could I revive within me/The symphony and song” is an invitation for any musician minded to use image or metaphor as a launching pad for an overture or a cadenza. But of all the lines that may have struck a chord with the composer, it was quite possibly: “It was an Abyssinian maid/And on a dulcimer she played”. This explicitly African reference would not have gone unnoticed by Coleridge-Taylor, for evocations of Africa and its diasporas were defining features of his substantial body of work.

COLERIDGE TAYLOR

COURTESY WORLD HISTORY ARCHIVE / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

His composition titles tell their own story: Variations on an African Theme; Bamboula Suite, named after a popular West Indian dance; Toussaint L’Ouverture, inspired by the legendary leader of the Haitian slave revolt; I’m Troubled in Mind, based on the Negro spiritual “Nobody Knows the Trouble I See”. These sources were not European, but the last piece was first heard by the composer in Britain, where it had been performed by the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Here then was the beginning of a transatlantic exchange of ideas that developed between musicians of colour throughout the 20th century.

Coleridge-Taylor, of whom Elgar, the leading British composer of the day, said, “he is by far the cleverest fellow going among the young men”, exhibited an interest in African and African-American culture from early in his life. He had studied the work of the leading figures of the European classical canon, specifically Antonin Dvorak,9 but his relationship with Black artists was even more important. In 1896, he met Paul Laurence Dunbar10, one of the most accomplished of the post-slavery writers who was pioneering the use of the African American dialects of the South in his poetry. When the latter visited London, they performed joint recitals. The musician wrote scores for several of the writer’s poems such as “The Corn Song”, “At Candle Lightin’ Time” and “The African Romances”.

Born in Holborn, London, in 1875 and raised in Croydon, Surrey, to an English mother and a Sierra Leonean surgeon father, who returned to Africa because of the failure of his progress in the medical profession, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was discovered by a local conductor, Joseph Beckwith. “A well dressed, curly headed, dark little boy, holding a small violin in one hand and his marbles in the other,” was what Beckwith said of the precocious child after happening upon him in the street.11

By the age of seven, Coleridge-Taylor showed ability on the violin, revealed an excellent singing voice and a keen interest in composition – an early indication of which was an arrangement of “God Save the Queen”. Among his first pieces for the Royal College of Music (to which he was admitted in 1890), performed with his fellow students were a clarinet sonata in F minor and Nonet, a piece scored for violin viola, cello, double bass, clarinet, horn, bassoon and piano, an instrument on which he had become proficient in just a few years. It made sense for him to gravitate towards the keyboard, with its rich harmonic and melodic possibilities, because his compositional gifts had been there for all to see from the outset.

Although the RCM was founded in 1883, with the philanthropic aim of making advanced training in music theory and performance available to winners of scholarships, it was, perhaps inevitably, not immune to racial prejudice. George Grove, who became the first director of the college, did not immediately endorse Coleridge-Taylor’s admission. There were concerns at objections from the other students over a ‘nigger’ crossing the threshold of the institution.

Even so, Coleridge-Taylor soon began to fulfil his potential. He found that composition rather than violin was where his heart really lay and, hopefully to the delight of Grove, he availed himself of the performance of his pieces by the RCM orchestra, set up by Grove to develop original work. Little is known of his very earliest compositions, but it is likely that he would have made a start with compositions for small ensembles within RCM rehearsal rooms. And if he was the only black person in the establishment, he may never have been happier than in that setting, surrounded by instruments, manuscripts and music stands.

In spite of, or maybe because of his isolation, Coleridge-Taylor had a marked sense of his blackness and took an explicit pride in it. He referred to himself as a black man rather than the more commonly used term of “coloured”, which would have been addressed to him as a man of mixed race with a light skin tone, and up until the very end of his life, he emphatically insisted on being called a Negro musician, noting on his death bed with a barely concealed degree of distaste: “When I die the critics will call me a Creole.” He was probably using “Creole” in the West African rather than the Caribbean sense, referring to the Westernised, often mixed-race elite in Sierre Leone who regarded themselves as superior to those who were culturally African.

It is probable that his racial pride was fostered by his experiences of racial discrimination. There were the “high jinks” he endured at school when other boys set fire to his “woolly” hair to see if it would burn. And whilst his work achieved great critical acclaim, he was not spared the indignities that stemmed from prevalent assumptions about the African continent. “Do you actually drink tea and eat bread and butter like the rest of us?” one clergyman asked. One can only wonder what the incredulous man of god would have made of the sight of the musician holding a bone china cup in the company of Ernest Hartley Coleridge years later as they discussed music and poetry instead of the pressing need to subject Africans to evangelisation.

He did not allow such indignities to hamper his progress as a composer. Surveying Coleridge-Taylor’s vast output, it is clear that his primary strength was the use of contour and contrast – tonally, metrically, rhythmically – to create music that had a wide spectrum of colours and movement that sometimes creates a carefully wrought mosaic effect.

Of his very early works, Fantasiestucke, five fantasia pieces for string quartets, stands out for its shifting time signatures, with the second movement’s serenade moving quite stealthily between 5/4 and 6/4. Commentators have evoked the “spirited melodies” of other parts of the piece such as “Minuet Trio”, where the volleys of short, curt notes, mostly eighths and sixteenths, have a galvanizing effect on the themes. There was a lively, hearty side to the composer’s character, and it surfaced in the dynamism of his scores.

In 1898, Coleridge-Taylor wrote a work that met with instant success when it was premièred at the Tin Tabernacle Room at the RCM and it still remains his signature piece: Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. This is the “little oratorio” that captured the imagination of the British public and launched “the coloured composer” internationally. Two sequels, The Death Of Minnehaha and Hiawatha’s Departure were composed in the two years that followed and the complete trilogy was performed at the Royal Albert Hall in 1900.

Based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s narrative poem, the original score has passages of soaring lyricism, tonal contrasts and richness of timbres and the general grandeur of sound that characterizes the late Romantic in classical music. This was the period when Strauss and Mahler created music in which both a yearning sensuality and an evocation of the natural world was able to touch listeners. Coleridge-Taylor caught some of this feeling, though the overt imagery in the succession of tableaux in his composition had something of a “light”, populist touch without being at all vulgar. Listeners may also have been attracted by the exoticism of the “red Indian story” with its array of characters whose names alone – Hiawatha, Minnehaha, Pau-Puk-Keewis, Yenadizze – evoked a “strange adventure” that was far removed from familiar English musical tropes.

Although the movements for orchestra and chorus have moments of majesty, it is the feature for solo voice, “Onaway Awake Beloved”, that represents Coleridge-Taylor at his most engaging. This has become a staple of the repertoire of tenor singers since its first airing at the RCM, and several recent recordings of this song can be found. The piece is a love song in which Hiawatha’s friend Chibiabos, beholding the maidens Minnehaha and Laughing Water, celebrates their beauty by evoking the “wildflower of the forest, lilies of the prairie, wildflowers in the morning.” While the natural imagery of Longfellow’s lyric provides the singer with rich raw material, it is the ingenuity of the composer’s score that catches the ear and conveys the essence of Chibiabos’ performance “in accents sweet and tender” and “in tones of deep emotion”. This is what vocal line and orchestration achieve, particularly in the way that the strings go through myriad shifts from slender and light to dark and thick timbres which convey if not a hint of foreboding, the implication that the blissful nature of the moment is tied to a certain undercurrent of seriousness. Throughout the piece there are many juxtapositions of legato and presto phrases, the effect of which is to have the voice floating bird-like over a forest of activity rustling in the strings and woodwinds. Several vocal lines are punctuated by discreet melodies comprising three to five notes. Coleridge-Taylor also uses the common classical composer’s method of having the same phrase played by several different instruments in the orchestra in turn, so as to anchor the character of the line in the mind of the listener, all the while emphasizing the distinct identity of the components of the ensemble.

Above all, “Onaway Awake Beloved” shows that the young Anglo-African, as he was referred to by many reviewers, understood one of the great maxims of orchestral music – the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The most conspicuous elements of the score – the infusion of brightness wrought by some of the key changes; the descending spiral of short, truncated string phrases that capture the delicacy of images such as “wildflower in the morning”; the chirpy, busy glissando effects that mark a contrast with the tranquil, relaxed glide of the central melody – catch the ear without jumping out too ostentatiously. And upon repeat listening, one hears shifts in the roles assigned to the instruments, such as the growing strength of the piccolos that pierce through the canopy of strings in quite aggressive fortissimo motifs towards the end of the piece, which contrasts with the relative subtlety of earlier lines.

Previous compositions had revealed Coleridge-Taylor’s desire to play with meter, realizing that alternations of an even six beats to the bar to an odd five could lend to a score the kind of wavering pulse that enables music to toy with perceptions of a regular and irregular unfolding of time. Yet with “Onaway Awake Beloved” the composer used a 4/4 rhythm to anchor the long, languorous notes that suggest his professed admiration for the “open air sound” and “the genuine simplicity” of Dvorak, one of his great idols. No doubt, one of the attractions of Dvorak was that the Czech composer had made his own discoveries of African American music in his Symphony No. 9 (the New World Symphony). In the 28 May, 1893 edition of the Boston Herald, Dvorak, who was then the head of the National Conservatory of Music in New York, had stated: “I am now satisfied that the future music of this country must be founded upon what are called the Negro melodies. This must be the foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States.”13

From the time he left the Royal College of Music in 1906, up until his death in 1912, Coleridge-Taylor continued to compose and travelled widely to perform his work. Apart from many concerts in London, there were recitals in Leeds, Brighton, Middlesbrough, Gloucester and, most significantly, in America. There his reputation spread rapidly to the black intelligentsia. He was one of their own. So the collaboration between Coleridge-Taylor and Paul Laurence Dunbar noted above was not serendipitous. Dunbar knew of Coleridge-Taylor. He wanted to meet him. Here, nationality was second to race. This was borne out by Coleridge-Taylor’s meeting with the Fisk Jubilee singers in Britain in the1890s, when he was greatly inspired by them. The admiration was not one-sided. The group’s manager, Frederick Loudin, sang the young composer’s praises to all who would listen. He took Mamie E. Hilyer, the founder of The Treble Clef club, a group of women music lovers from Washington D.C, to visit Coleridge-Taylor and his wife at their home in Croydon. Such was their mutual empathy that the Treble Clef club became the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Chorale Society upon Hilyer’s return to America. The composer’s work soon crossed the Atlantic. Hiawatha was performed at the Metropolitan Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington on 23 April 1901.

The following year Coleridge-Taylor made the first of three visits to America at the behest of Hilyer. From the moment he stepped off the boat at Boston there were half a dozen eager newspaper reporters waiting to “devour” him and thereafter his schedule took him to major cities such as Washington and New York.

The pleasure that he took in attending an African American church service and having the opportunity to conduct an orchestra with a Black chorus was uppermost in his mind as he explained in a letter to Hilyer: “I don’t think anybody else would have induced me to visit America, excepting the fact of an established society of coloured singers. It is for that first and foremost that I am coming.”

Press reports of the performances were entirely favourable, but what came to the fore very quickly was the socio-cultural significance of the appearance of a black composer in highbrow theatres and concert halls. The regional African-American newspaper, The Georgia Baptist, did not hold back in expressing pride at the achievements of the artist who was less a Briton and more a Black. He was their man from across the water who was made to feel very much at home.

When Samuel Coleridge-Taylor of London walked upon the platform of Convention Hall last Wednesday night, and made his bow to four thousand people, the event marked an epoch in the history of the Negro race of the world. It was the first time that a man with African blood in his veins ever held a baton over the heads of the members of the great Marine Band, and it appeared to me that the orchestra did its best to respond to every movement of the dark-skinned conductor.14

Plans were made for Coleridge-Taylor to be introduced to President Theodore Roosevelt, but he was unavailable when the meeting was supposed to take place. Nonetheless, the fact that such an encounter was proposed indicates how far his star had risen. He was courted by the ruling elite as well as by the Black community.

A sign of his elevation was the name given him by the prestigious New York Philharmonic, with whom he worked on his third trip to America in 1910. They dubbed him the “African Mahler” because Mahler was regarded as the greatest living composer to have ever visited the New World. The fact that Coleridge-Taylor was not referred to as British, or even Black British, underlines the lack of recognition of a black British identity. Elgar was white. He was authentically British. Coleridge-Taylor was seen as an African before anything else, though he was really a South Londoner.

Given the appalling racism Coleridge-Taylor had received from some of the classical music establishment – the renowned conductor Hans Richter expressed disdain for his scores on the grounds that they were the work of a “nigger” – and because he was well aware that his father had returned to Africa because of the difficulties of being a black doctor in London, it is not surprising that Coleridge-Taylor related his achievements to his race, rather than to his geographic location: “I am a great believer in my race.”

He had read The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Dubois’ seminal 1903 treatise on the condition of the Negro in America, and was very much aware of the political resonances that his work acquired. Musical development was not the sole issue. What was at stake was the wider perception of Blacks and their place in society. Any Black music that was able to win the favour of a monarch or moneyed patrons, because it was thought to be on a par with the sophistication of European classical music, would thus gain the greatest accolade. It would show that a supposedly inferior race could reach the level of the superior one. Describing Negro songs as American or British was problematic because Negroes were seen as neither American nor British – an issue that has resonated into the 21st century. Inevitably, Black music was perceived as a phenomenon that fell outside well-established European norms, which is exactly why Coleridge-Taylor was not so much a British composer as an “African” Mahler.

Coleridge-Taylor’s commitment to his blackness led him to materials that emphasised his race. The use of more explicitly African and West Indian elements in the music first emerged between 1904 and 1905 when he wrote Four African Dances and Twenty Four Negro Melodies. Of the latter, Coleridge-Taylor said: “What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music, Dvorak for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for the Negro melodies.”15

The sources of the 24 Negro Melodies were found far and wide: east, west and South Africa, the West Indies, and Black America. For the latter, Coleridge-Taylor turned, perhaps inevitably, to a book of songs used by the Fisk Jubilee Singers as well as to an extensive collection of Jubilee and Plantation Songs and Afro-American folk songs. One might expect the result to be a kind of Afro-classical music, but judging from the analysis of excerpts of available scores, as well as from the insights provided by Coleridge-Taylor himself, the aim was not necessarily a blend or fusion of “ethnic folk” and concert music, but rather an attempt to stay true to his identity as a symphonic composer whilst using a range of materials that was not exclusively European.

Recurrent in the American themes is the emphasis on intervals such as minor thirds, which has the effect of imparting some of the emotional warmth that pervades idioms such as the Negro spiritual. Yet Coleridge-Taylor’s training and education as a European classical composer is what dominates. Ultimately, it can be said that the work is really classical music with mild African and African-American resonances rather than Afro-classical music per se. The title of one of his other works, Symphonic Variations on an African Air, makes his position clear. It is also fair to describe Coleridge-Taylor’s work as accessible and appealing rather than esoteric or dense, and that may well explain why he was able to catch the ear of the general public in the way that he did. In Britain, he was, after all, writing for a white audience.

In 1912, just seven years after the completion of 24 Negro Melodies, Coleridge-Taylor died, at the tragically young age of 37. Although the official cause of death was pneumonia, the sheer weight of his workload was a contributory factor, and that may have been tied to the paltry income he received for his compositions and conducting engagements during his lifetime. Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast was immensely popular, but was sold to a publisher for just three guineas.

A cursory glance through his substantial oeuvre is sufficient to remind us that Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was a serious classical composer, but the immense appeal of some of his works reveals his openness to qualities that were not necessarily taught in the practise rooms of a venerable institution such as the Royal College of Music. Among the letters that Coleridge-Taylor wrote to a friend is one that clarifies his thoughts on the question of musical nature versus nurture. The friend had travelled in Eastern Europe and its border with Asia and was surprised at how good the local gypsy musicians were. To which Coleridge-Taylor replied:

Were they to study such things as harmony, would they be better off?

But I warn you not to allow harmony to cramp your artistic development, because it should be remembered that these things must always be subservient to the beauty of sound. Imagination should be far more thought of than it is in the playing of music.

Technique is not everything and everyone has some small amount of imagination. We must look upon music from a more impersonal standpoint. It is becoming too much admiration for the man, and too little love for his music.

Those words are ironic, because Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s works did not die with him at all. In later years there would be grand revivals of his work, and in the West Indies classical music societies bearing his name were established.

1. Lewis Winstock, Songs and Music of the Redcoats: A History of the War Music of the British Army 1647-1902 (Leo Cooper, 1970) p. 173

2. Songs and Music of the Redcoats, p. 246

3. Ibid., p. 205

4. Ibid., p. 295

5. Ibid,. p. 197

6. Paul Oliver, Black Music in Britain (Open University Press, 1990), p. 88.

7. The account of Coleridge-Taylor’s life is drawn from Jewel Taylor Thompson, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: The Development of His Compositional Style (Scarecrow Press, 1994). The descriptions of the music come from my own listening.

8. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “Kubla Khan Or A Vision In A Dream” (1816) in The Complete Poems (Penguin, 1997).

9. Dvorak, with his admiration for African American music, was a great source of inspiration to Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, so there was a certain symmetry in the declaration.

10. Paul Laurence Dunbar continues to be relevant to black musicians long after his death. In the early 1960s, American jazz vocalists Abbey Lincoln and Oscar Brown Jnr both recorded outstanding versions of his poem “When Malindy Sings”.

11. Jewel Taylor Thompson, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: The Development of His Compositional Style, p. 14

12. Jewel Taylor Thompson, op. cit. p. 116.

13. Jewel Taylor Thompson, op. cit.

14. Jewel Taylor Thompson, op. cit.

15. Jewel Taylor Thompson, op. cit.

16. Quoted in Jewel Taylor Thompson.