![]()

Rise of New Competitors and a Changing Basis of Competition

SINCE ITS FOUNDING IN 1995, EBAY, THE ONLINE MARKETPLACE FOR the sale of goods and services, has been at the epicenter of changes in the global competitive landscape. A platform that started out allowing people to trade used Beanie Babies and baseball cards has evolved into an international bazaar where everything from small cities (Bridgeville, California, has been auctioned three times since 2002) to a $28,000 partially eaten grilled cheese sandwich bearing an image of the Virgin Mary changes hands.1 The $2,642 worth of goods that trade on eBay every second symbolizes the peer-to-peer business opportunities it has enabled for small businesses.2

By 2002, when eBay grew to become a $1 billion revenue business, many believed it to be unstoppable.3 With its low transaction costs and overhead, eBay forged a business model that could scale rapidly—and posed a threat to a host of retailers. In 2003, eBay, fresh off its success in the United States, plunged into the nascent Chinese e-commerce market. By 2005, according to Forbes, eBay had one-half of the country’s $1 billion e-commerce market. “A bunch of small competitors are nipping at our heels,” said Meg Whitman, then the chief executive officer.4 Among them was Alibaba, started in the apartment of a former teacher named Jack Ma. Worried that eBay might encroach on its core business-to-business market, Alibaba in 2003 launched a competing consumer-to-consumer auction site named Taobao (“digging for treasure”).5 Since those early days, China’s e-commerce market has evolved into a vast ocean, and Alibaba is now the great white shark at the top of the food chain. In 2006, Taobao overtook eBay’s EachNet and became the leader in the Chinese consumer-to-consumer market, and the company has rolled from strength to strength.6 Alibaba’s blockbuster $25 billion initial public offering, on the Nasdaq in September 2014, attracted hordes of investors.7 According to its IPO filing, Alibaba boasts 231 million active buyers and earned $6.5 billion in revenues in the last nine months of 2013 alone.8 At the end of November 2014, Alibaba’s market capitalization stood above $270 billion, above Facebook’s and quadruple eBay’s.9

Disruptive forces are combining to transform the very nature of global competition in virtually every sector. Online players are no exception, and disruptors such as eBay often find themselves disrupted before they enter adolescence. The industrialization and urbanization of emerging economies is powering a new breed of formidable corporate giant that is rapidly gaining prominence on the world stage. As the world becomes more interconnected, the speed at which emerging-market companies can mount their assault on world markets is accelerating. Technology is shifting the balance of power between large, established companies and smaller, nimbler start-ups, moving value from sector to sector and blurring the boundaries between them, mandating a redefinition of whom you view as competitors. Rather than focus on local rivals you know intimately, start becoming familiar with upstarts you’ve never heard of, based in towns and cities you’ve never visited, working on platforms on which you’ve never stepped, and deploying advantages that may be difficult to replicate.

TREND BREAK

For large parts of the twentieth century, the global competitive landscape resembled a steady, slow-moving game. The terrain was dominated by developed-world giants—especially North American and European companies—that had dueled with their well-known competitors for decades. In those days, it was Ford versus General Motors, Coca-Cola versus Pepsi, Nestlé versus Hershey, Burger King versus McDonald’s, Time versus Newsweek, Barcelona versus Chelsea. Year after year, titans slugged it out for dominance, and the rosters didn’t change much. Roughly two-thirds of the companies listed on the Fortune 500 in the 1960s were still there fifteen years later.10 When a new entrant did come onto the scene, it was most likely a well-known competitor from an adjacent region or country or from an adjacent sector. GM and Ford had long anticipated Volkswagen’s entry into the US market during the 1950s. In Brazil, for example, GM, Ford, Fiat, and Volkswagen together held more than 90 percent of the domestic car market during the 1960s and 1970s.

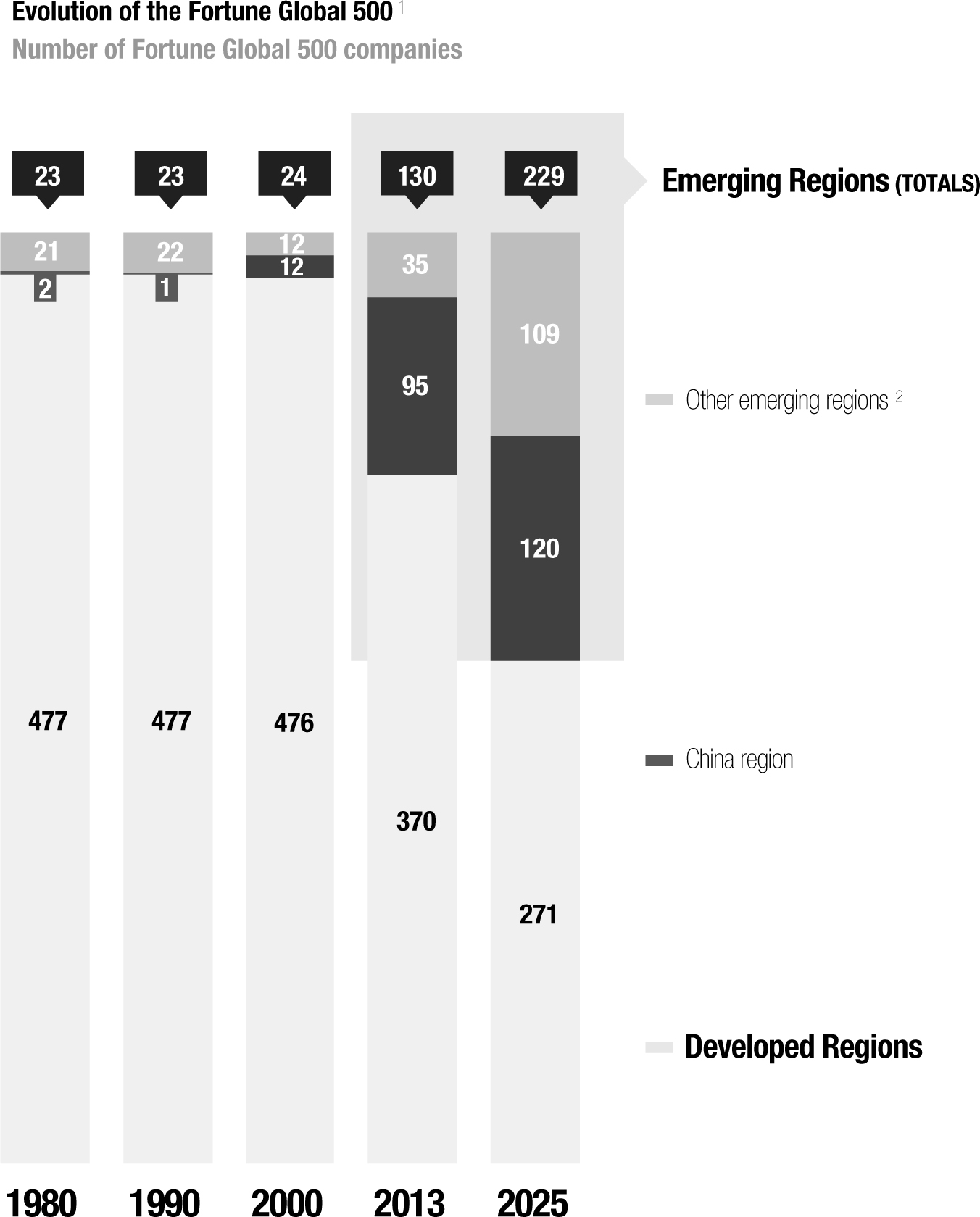

During the last few decades of the twentieth century, however, the dynamic began to change—with a definitive trend break in the first decade of this century. First, emerging-market companies began to grow with the industrialization in their domestic economies, gaining scale and mass. The global ascendance of Japanese firms like Sony, Toyota, and Panasonic in the 1970s preceded the rise of companies from South Korea and Taiwan in the 1980s and China in the late 1990s.11 After holding steady at just over twenty companies between 1980 and 2000, the number of Fortune Global 500 companies headquartered in emerging markets rose 50 percent by 2005, doubled by 2010, and doubled again by 2013, reaching 130.12 MGI’s projections suggest that emerging economies will be home to half of the Fortune Global 500 by 2025. Walmart, IBM, Coca-Cola, and ExxonMobil are still on the list. But so, too, are CNOOC, Cemex, and Petronas. The growth of global trade and financial interconnections is enabling these emerging-market giants to grow and enter new markets around the world.

Secondly, technology is fueling competitive churn and shortening the life spans of established companies. Life at the top of the corporate food chain increasingly resembles the bleak way in which Thomas Hobbes memorably defined human existence without organized communities: “nasty, brutish, and short.” The average company’s tenure on the S&P 500 fell to about eighteen years in 2012, down from sixty-one years five decades earlier.13 It’s no longer sufficient to regard large firms as potential competitors; start-ups with access to digital platforms can be born global, scale up in the blink of an eye, and disrupt long-standing rules of competition in markets ranging from taxi services to hotels and retail. Many of these micro-multinationals are upending competition by bringing about a new “sharing economy” in hospitality (Airbnb), transportation (Lyft), and even home Wi-Fi rentals (Spain’s Fon). Technology has leveled the playing field between large and small players and increased companies’ willingness to enter new markets and expand into new sectors. Microsoft took fifteen years to reach $1 billion in sales.14 Amazon reached that mark in fewer than five years.15 Netflix is no longer merely disrupting content distribution, but is also becoming a formidable force in original content production. Zipcar and other car-sharing upstarts are not only disrupting the car-rental business, they are also challenging traditional car ownership models. This raises an important point about the changing basis of competition. In previous decades, companies didn’t just know their competitors intimately; they recognized the way they did business. At root, General Motors, Volkswagen, and Ford were engaged in the same endeavor—using assembly lines to turn steel, plastic, and rubber into vehicles. Today, however, as technology continually allows for the creation of entirely new platforms, incumbents may not have any familiarity with the mechanics, business models, and competencies of their new competitors.

The acceleration of emerging-economy growth, technological change, and global interconnections since the early 2000s has created a trend break in the world of competition. It is no longer a slow-moving board game played by large firms in adjacent sectors and regions. It now more closely resembles a fast-moving video game in which new competitors emerge, seemingly instantaneously, from any part of the world and any sector of the economy, and can gain mass and scale in a heartbeat. Established firms, long used to the old rules of competition, will need to reset their intuition to compete effectively.

THE RISE OF EMERGING-MARKET COMPETITORS

The first wave of global competitors to Western firms rose out of the ashes of postwar Japan. In the 1960s and 1970s, many US and European incumbents faced the rise of Japanese companies. By 1965, Japanese companies in chemicals, plastics, and other industrial sectors were listed in international rankings of the largest sector participants. By 1980, South Korean groups such as Hyundai and Samsung joined the ranks of global industrial conglomerates.

As companies from Japan and then Korea began to move up the value chain, a second wave of emerging-market competitors entered the global scene, following the early stage of industrialization in these countries. Large companies in natural resources, construction, manufacturing, and commodities appeared on the global playing field during the late twentieth century from China, Brazil, and other emerging countries. Oil and gas companies such as China National Petroleum, Sinopec, Gazprom, and Petrobras took their place alongside giants like ExxonMobil, Shell, and Total. These emerging-markets giants offered a taste of how global the competition in other sectors could become. In mining, basic materials, and minerals, emerging-market companies such as Brazil’s Vale, Russia’s Norilsk Nickel, and China’s Shenhua Group already control about half of worldwide sales. The comparable figure is approximately 40 percent for the global construction and real estate industry.

By 2025, emerging regions are expected to be home to almost 230 companies in the Fortune Global 500, up from 130 in 2013

1 The Fortune Global 500 is an annual ranking of the top 500 companies worldwide by gross revenue in US dollars.

2 Shares of emerging regions excluding China and Latin America combined until 2000.

NOTE: Fortune Global 500 share in 2025 projected from revenue shares of countries in 2025.

SOURCE: Fortune Global 500; MGI Company Scope; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

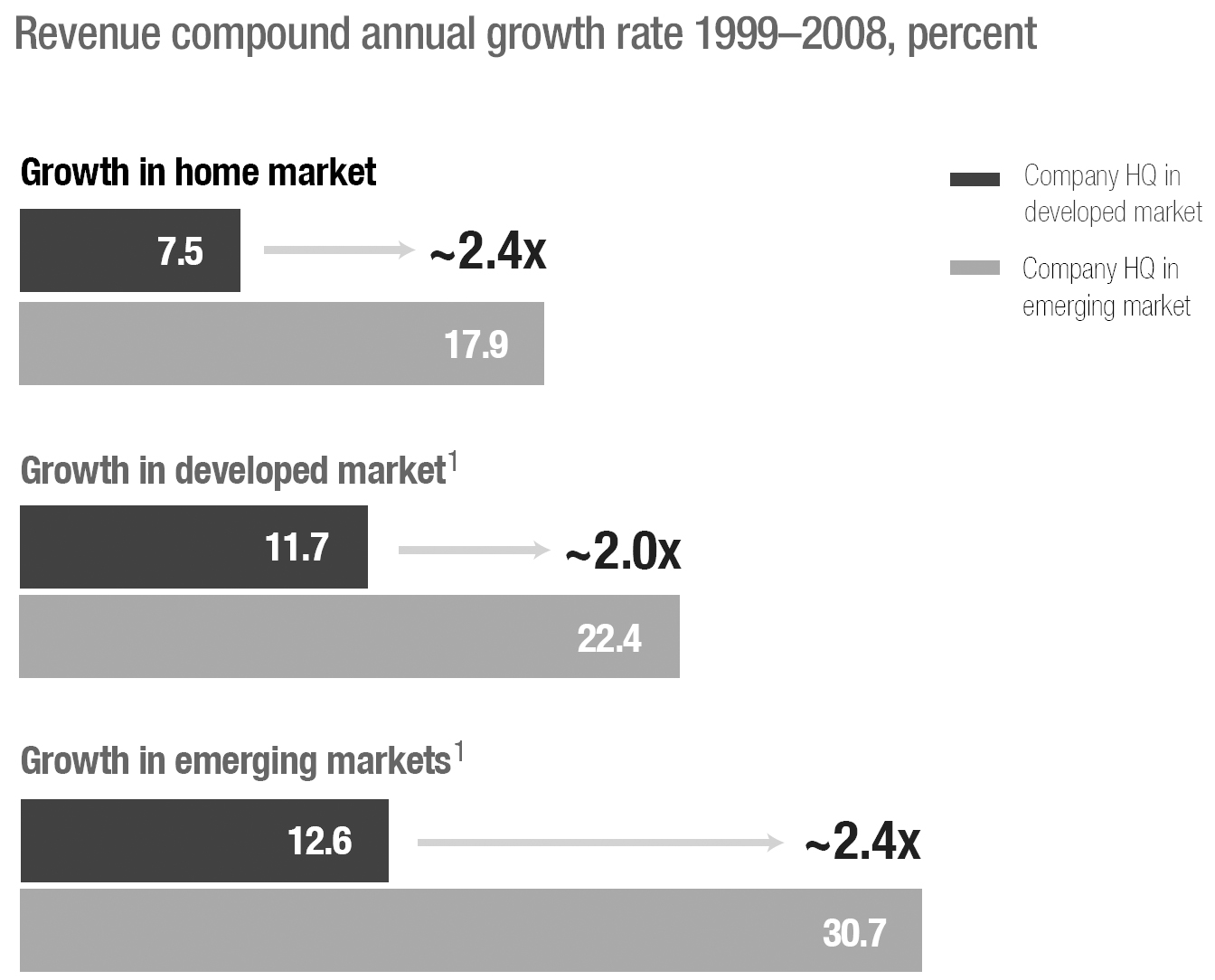

Next came the current, third wave, bigger and fiercer than ever before. Emerging-market companies that grew to dominate hugely populous local markets have already long surpassed the scale of their developed-world counterparts. Bharti Airtel, the largest telecom company in India, has roughly 275 million mobile customers in South Asia and Africa. By contrast, AT&T, the largest telecommunications company in the United States, has 116 million wireless customers.16 Mumbai’s Tata Group employs more than 580,000 people worldwide and is now one of the largest private-sector employers in the United Kingdom, with nineteen companies and over 50,000 workers.17 Our research suggests that emerging-market companies are growing more than twice as quickly as their counterparts in developed economies.18 Over the coming decade, the GDP of emerging markets may increase by a factor of 2.5, which will reset the global competition landscape. Seven out of ten of the new “billion-level” companies—firms with annual sales of more than $1 billion—are likely to be based in emerging regions. The number of large companies based in these countries could increase from 2,200 today to around 7,000. If that holds true, China alone will house more large companies than either the United States or Western Europe by 2025.19

MINNOWS AND SHARKS

Technology is also shifting the balance of power from large, established incumbents to small businesses, start-ups, and entrepreneurs. In global markets, size has typically not only been an advantage—it has been a necessity. In the 1990s, it was virtually impossible for small enterprises to compete in markets around the world or to scale up operations to a global level immediately. In the vast commercial ocean, the sharks would easily mow down the minnows. Today, however, minnows are increasingly chasing and getting the better of sharks, thanks in large part to the rise and power of new technological platforms such as Alibaba and the UK government’s procurement portal.

In an important trend break, technology has allowed small, nimble attackers to compete with large, established companies. Start-ups today can plug into enormously powerful global platforms with the same ease as a large corporation and can expand to millions of customers in a matter of a few years, if not months. The success of “sharing economy” start-ups such as Airbnb and Lyft exemplifies the way technology is removing barriers to entry and scale, allowing part-time individuals to compete with established players. Waze, an Israeli community-based navigation mobile app, grew from zero to more than fifty million users in less than five years.20 In June 2013, Google—the ultimate shark in the app and mapping space—paid a reported $1 billion to acquire Waze. Another example is TransferWise, a UK start-up offering a peer-to-peer money-transfer service in seventeen different currencies.21 TransferWise grew from zero to over $1 billion in transactions in less than four years, threatening the established business model of currency exchanges and money-transfer providers.22

Emerging market companies are growing faster across the board

1 Other than home.

Large institutions often find themselves caught off guard and unable to pivot fast enough. Many find themselves paralyzed by complicated processes and large legacy IT systems that often delay execution for months, if not years. New competitors can buy state-of-the-art systems off the shelf and install them in a matter of weeks. Three-D printing allows start-ups and small companies to “print” highly complicated prototypes, molds, and products in a variety of materials with no tooling or setup costs. Cloud computing gives small enterprises IT capabilities and back-office services that were previously available only to larger firms—and cheaply, too. Indeed, large companies in almost every field are vulnerable, as start-ups become better equipped, more competitive, and able to reach customers and users everywhere.

Because it is so easy for minnows to take on sharks, companies that not that long ago disrupted entire industries must constantly pay attention to other disrupters. Expedia, which launched in 1996, grew to become the largest travel company in the world, reaching $4.8 billion in revenues in 2013.23 By aggregating prices, data, reviews, and payment options, the web-based start-up constituted an important new platform that changed the basis of competition in the industry. But Expedia and its peers now face disruption from a new type of business model represented by Airbnb, the peer-to-peer hospitality site. Airbnb’s millions of customers can research, reserve, pay for, and review lodging at hundreds of thousands of locations without needing to interact with Expedia’s platform. Technology giants such as Facebook and Google must also be aware of new entrants. Snapchat, a photo-messaging app that enables senders to set a time limit for how long receivers can view their “snaps” (pictures), was started in 2011. By 2014, its users had proved more prolific snappers than those on Facebook and Instagram, with four hundred million pictures shared every day.24 WhatsApp reached five hundred million active users and handled over ten billion messages per day in 2014, prompting a $19 billion acquisition by Facebook, a move that was as much defensive as it was a strategic expansion.25

BLURRING LINES

Technology has long blurred the boundaries between physical and online consumption, shifting value from books to Kindles and from CDs to iTunes to Spotify, where users can stream music without ever formally taking ownership of it. As information technology has given consumers an ever-greater ability to compare prices and products, companies have been forced to cut margins in their traditional businesses—and search for new opportunities. Companies are increasingly expanding into new sectors to exploit their privileged access to technology, data, or customers or to simply reinvent themselves in the face of disruption. The endless and rapid disruption imposed by technology is leading to some unlikely pairings. As Carlos Ghosn, the chief executive officer of Nissan, has perceptively noted, “Business schools may prepare people to deal with internal crises. But I think we need to be more prepared for external crises, where it’s not the strategy of the company that is in question; it’s the ability of leaders to figure out how to adapt that strategy. We are going to have a lot more of these external crises because we are living in such a volatile world—an age where everything is leveraged and technology moves so fast. You can be rocked by something that originated completely outside your area.”26

In the early 2000s, UK auto insurers were caught off guard by the rise of price-comparison websites such as Confused.com. By tilting the balance of power away from traditional insurers, the aggregator sites grew their market share from zero to over 50 percent of new insurance policies in a decade.27 With increased price transparency and consumers shopping around, many traditional players have struggled to make money on core underwriting in UK motor insurance ever since. In response to the success of online aggregator sites, nontraditional players such as Google have started to take notice and experiment in the space. In a live poll at a recent Digital Insurer Event in the United Kingdom, 75 percent of responders worried about the likes of Google representing the biggest threat to the industry.28

In addition to the new online players, traditional insurers now also have to worry about car manufacturers encroaching on their playing field. As smart car technology advances, car manufacturers such as Citroën are announcing plans to fit black boxes into all new vehicles of certain models. The use of telematics technology allows companies to monitor driving habits such as distance traveled, speed, and braking behavior—and better understand customer behavior as a result.29 Whether car manufacturers will become major insurance players remains to be seen, but insurers such as Allianz have already entered into partnerships to mitigate the threat.

In media, technology has long shifted value between players and blurred boundaries between adjacent sectors and distribution channels. Netflix is an example of a company that has managed to thrive as the basis of competition shifts quickly. Originally a subscription service sending DVDs of movies through the mail, Netflix quickly pivoted to a content-streaming company when online video caught on. Then, as competition arose in online video distribution, Netflix decided it needed to get into the content creation business. In 2012, eager to give its twenty-four million customers reason to keep subscribing, Netflix partnered with director David Fincher and production firm MRC to air House of Cards, a deeply cynical, high-quality drama series starring Kevin Spacey as an immoral politician. The show, an adaptation of a British series of the same name, attracted audiences that rivaled those of popular cable television shows, with viewership of about three million in the United States alone.30

HOW TO ADAPT

Adapting to the changing nature of competition isn’t easy, particularly for companies that built their culture, strategy, and processes in the old world of global competition. The question for most executives today isn’t if they will get disrupted but when, by whom, and how severely. It is of paramount importance that your business expands its thinking beyond the traditional competitor set, monitors the growth of new competitors, and strives to understand the economics and business models of new industries. In addition, spend the time and mental energy to develop a new clarity about your own assets, core competencies, and competitive advantage. The most successful executives will choose the right allies and be prepared to take decisive action—even if it means disrupting their own businesses.

Understand and Monitor the New Ecosystem

You’ll need to track up-and-coming business hubs in emerging regions. Small- and medium-sized cities across the emerging world pose a particular blind spot. But they are the ones that give rise to the most dangerous future competitors. For example, Hsinchu, in northern Taiwan, may not be a household name, but it is already the fourth-largest advanced electronics and high-tech hub in the China region, home to thirteen large company headquarters. Similarly, Santa Catarina is not yet on the radar of most executives. But the prosperous state in southern Brazil has incubated and housed the biggest chicken processor in the world (BRF), the world-leading maker of refrigeration compressors (Embraco), the leading Latin American clothing textile company (Hering), and the largest Latin American electric motor manufacturer (WEG Indústrias).

Technology-based start-ups pose unexpected challenges to some industries that need to be monitored. But what’s the best way to keep tabs on young upstarts and the revolutionary ways in which they are doing business? Some large companies are using the accelerator model to stay close to potential disruptions. General Electric’s GE Garages is a pop-up lab incubator that provides start-ups with access to high-tech equipment such as 3-D printers, computerized numerical control machines, and laser cutters. The start-ups get access to equipment and GE’s technical and managerial expertise, and GE can move quickly when new technologies reaches maturity.31

GE is not alone. Samsung runs accelerators in Silicon Valley and Tel Aviv. In July 2014, Disney invited eleven technology and media start-ups to join its accelerator program. BMW’s iVentures incubator houses companies such as Life360 and ParkatmyHouse.com. Microsoft Ventures supports start-ups through a community of mentors, providing funding to early stage firms and using seven accelerators around the world to speed up successful launch and scale.

Tap the Power Within

The disruptive nature of the new competitive landscape means that traditional players need to deploy all assets at their disposal. As a result, it is crucial for incumbents to take another look at their assets and unique positions.

In an environment of increased competition in the automotive industry, German premium car manufacturers have relied on a multifaceted approach—strong brand heritage, superior car quality, strong organization skills, and accelerated innovation in materials, software, and connectivity.

BMW, for instance, enhances the customer experience through features such as remote-control services, including a mobile app that lets users set the interior temperature of the car, find where it’s parked, and check if the doors are locked remotely. The company is the first major OEM (original equipment manufacturer) to produce carbon-fiber cars on a large scale for its i series. The BMW i3’s technical capabilities include a parking assistance feature that allows the car to park itself at the push of a button.32 Daimler’s Mercedes-Benz E- and S-class cars have steering assistance and “stop & go” features that enable the cars to autonomously navigate traffic lights, roundabouts and other vehicles on the road.33 In 2014, Audi introduced Audi Connect—a state-of-the-art software package with 4G connectivity, picture navigation, and multimedia functionality—in its Audi A3 models in 2014, partnering with AT&T in North America to do so.34 Such product enhancements, added to an already powerful brand heritage, have allowed premium German automakers to ward off rising competition, with Mercedes, Audi, and BMW all hitting record sales in 2013.35 Put another way, in an era when automakers around the world can make solid, functional vehicles at a relatively low cost, German automakers have decided to compete on the basis of information technology, apps, software, and customer experience—rather than relying solely on the superiority of their chassis and power trains.

Form Alliances

Finding partners is crucial to thriving in an era in which the basis of competition is shifting rapidly and traditional business models may quickly become uprooted. Smart alliances that can provide a hedge for the future, quick access to new capabilities, or help pivoting the existing business model will be increasingly vital.

The traditional telecommunications industry faces uncertainty, as new competition cuts into margins and new technology brings both challenges and opportunities to existing business. While WhatsApp and similar message mobile apps are increasingly capturing the SMS market, traditional players are struggling to survive. Increasingly, they are seeking to change the basis of competition by viewing their expansive mobile networks and customer bases as platforms for providing other services. This mind-set of traditional players places a higher premium on striking smart partnerships.

In emerging markets, mobile reach often exceeds banking access. In countries like Argentina, Colombia, and Ukraine, for example, virtually everybody has a mobile phone, but less than half the population has bank accounts. As messaging apps threaten to disintermediate their core business, telecommunication companies have partnered with banks to offer new payment channels. In Kenya, Safaricom, East Africa’s largest mobile telecommunications provider, partnered with Commercial Bank of Africa to launch m-pesa, Afric’a first SMS-based money transfer service, in 2007. (The m is for mobile, and pesa is Swahili for “money.”) In its first eigtheen months of existence, m-pesa gained four million users, many of whom don’t have bank accounts and rely on a network of agents they can visit to deposit and withdraw cash in exchange for virtual money. In 2013, m-pesa had fifteen million users, and the company is recognized as one of the most successful financial services innovators in the world.36 In Brazil, the country’s largest telecom player, Oi Telecom, partnered with UK-based data analytics firm Cignifi to generate credit scores for customers based on mobile phone behavior. The information was then used to extend lending services to unbanked customers in Brazil through Paggo, Oi Telecom’s SMS-based virtual credit card system.

In developed markets, health-care players have turned into valuable partners for telecom incumbents. Orange began to offer mobile health services, such as remote monitoring systems for diabetics and cardiac patients, to gain a stake in health-care growth by addressing consumer demand for home care with mobile solutions. Deutsche Telekom teamed up with Germany’s largest health insurance company, Barmer, to develop mobile fitness solutions that track data like heart rates and the distance traveled during workouts and send it to the company’s health portal, which generates new training programs.

Engage the World’s Talent

As new competitors emerge, all businesses will find themselves increasingly competing for the skills they need. According to a survey of senior executives, 76 percent believe their organizations need to develop global-leadership capabilities, but only 7 percent think they are currently doing so very effectively.37 About 30 percent of US companies say they haven’t exploited international opportunities sufficiently because they have too few people with international competencies.

Offering executives from emerging markets global career opportunities is one powerful way to get the best talent. In 2010, Unilever assigned about two hundred managers from its Indian subsidiary to global roles with the parent company, and two of them are now part of the top leadership team. Other companies are finding that the traditional single headquarters model no longer fits their needs. Some have set up secondary headquarters or split head-office functions to align more closely with markets outside their home territory. General Electric and Caterpillar Group have split their corporate centers into two or more locations that share decision making, production, and service leadership. Unilever, whose main headquarters and incubator for executive talent is in London, created a second leadership center for global development in Singapore, aiming to attract and retain leadership talent with a global mind-set. After all, Unilever derives 57 percent of its revenues from emerging markets.38 “Singapore sits at the nexus of the developed and emerging world. It is a leading hub for leadership and innovation and a gateway to the rapidly growing Asian economies,” as Unilever CEO Paul Polman put it. “When our future leaders come here, whichever part of the world they come from, we know they will gain exposure to new insights and perspectives.”39

Avoid Inertia

It’s a point we’ve stressed in earlier chapters, but business leaders will have to become more agile in this new era of competition. They will have to be wary of maintaining the status quo and build new skills, particularly when it comes to capital allocation and technology.

Beyond expanding and monitoring their competitors, business leaders have to train themselves to become more agile in the way they allocate and deploy their capital. In fact, we’ve found that companies that perform well on measures of agility, such as changing their capital reallocation from year to year, post significantly higher performance with lower risk. Based on data from more than 1,600 companies, we found that total return to shareholders of the top one-third most agile companies—those with the highest capital reallocation year over year—was 30 percent higher than that of the least agile companies, whose capital allocation remain fixed year after year.40

In a world where technology is allowing sharks to fall prey to minnows, business leaders have to become fluent in information technology. As companies seek to negotiate the new landscape, as they eye potential rivals and partners, they have to elevate technology to the core of strategic thinking in every business unit. In addition to employing a chief information officer, who generally tends to the nuts and bolts of the technology a company uses, there is a strong argument for having a chief digital officer, who oversees technology as a strategic issue. Technology is becoming the lever through which companies can disrupt their own business models and adapt to the changing basis of competition. Burberry, a British fashion company, rebuilt itself from the inside out to become a technology leader.41 Developing the concept of “democratic luxury”—the strategy of providing universal access to its brand—Burberry launched a cross-platform digital strategy. It integrates its website, social media, other social applications—such as Burberry Acoustic, a YouTube project promoting unknown British musicians—and its technologically innovative flagship stores.42 As then-CEO Angela Ahrendts put it, “walking through the doors [of the Regent Street flagship store] is just like walking into our website.”43 By going digital, Ahrendts said, Burberry “nearly tripled the business in seven years.”44

![]()

Competing in the global economy in some ways resembles the quadrennial soccer World Cup. It’s a high-profile, high-stakes, high-tension tournament in which a team’s fortunes can rise and fall very quickly. A squad may spend years qualifying and building a base that enables it to compete on the world stage, only to falter at an important moment or crash when an unexpected source scores a goal. While upstarts occasionally make a run, the established powers tend to win most of the time. The 2014 semifinalists—Germany, Argentina, Brazil, and the Netherlands—have won eleven of the twenty championships between them. But there’s an important difference between soccer and business. At the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, thirty-two teams competed. All of them used the same ball, played on a field the same size, and had to abide by the same rules. Thanks to the rapidly changing basis of competition, however, the economic World Cup is more like a free-for-all. Competitors can show up from any corner of the earth with skilled strikers and unbeatable goalkeepers, and they bring their own rules with them. Some may field eighteen players at the same time instead of the standard eleven, while others may use a ball that can be manipulated by remote control. To compete, your organization must deploy effective networks of scouts, redouble its training efforts, and mine your culture and workforce to develop the most effective strategy.