![]()

Challenges for Society and Governance

IN THE LATE 1990S, GERMANY WAS OFTEN DUBBED THE NEW “SICK man of Europe.”1 And with good reason. Seven years after reunification with the impoverished east, Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s administration was struggling with unemployment near 10 percent, slowing GDP growth, an aging population, and a strained welfare system. The situation worsened over the next several years. Economic growth was less than 0.5 percent a year, the economy went through two brief recessions, and by 2005 unemployment stood at 11 percent.2 Yet less than a decade later, Germany is being hailed as an economic wonder. By 2008, the unemployment rate had fallen to 7.5 percent. As the global recession took hold and millions of workers lost their jobs around the world, Germany’s unemployment rate held steady, then fell further, to 5.4 percent in 2012—despite an even sharper contraction in the country’s GDP.3 World leaders from Barack Obama to Xi Jinping have sought inspiration from Chancellor Angela Merkel and the “German miracle.” How did the sick man recover so quickly?

Between 2003 and 2005, the German government enacted a series of aggressive labor market reforms as part of its Agenda 2010 program. Under the so-called Hartz reforms, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder revamped the German labor market by improving vocational education, creating new job types, and changing unemployment and welfare benefits. The wide-ranging reforms were deeply unpopular. More than one hundred thousand people marched in the Monday demonstrations of 2003 to protest cuts to social welfare benefits.4 Older workers—whose labor force participation rose after the reforms—were not always interested in extending their careers. Chancellor Schröder’s party lost the 2005 elections to Merkel, who subsequently benefited from the German miracle.

In the era of trend breaks, the primary challenge for policy makers is the one Germany’s government faced in the early 2000s. How can governments respond faster and develop the political maturity and leadership needed to help societies navigate changes and ensure their own survival in the process? Those who govern will need to reset their intuition, just as business leaders will. In this chapter, we discuss the political leadership challenge these trend breaks present, and we highlight ways that government is rising—or not—to meet this challenge.

THE CASE FOR CHANGE

Global competition and technological change have sped up creative destruction and outpaced the ability of labor markets to adapt. Job creation is a critical challenge for most policy makers even as businesses complain about critical skill gaps. Meanwhile, graying populations are starting to fray social safety nets—and for debt-ridden societies in advanced economies, the challenge can only get more pressing as the cost of capital starts to rise. Much-needed productivity growth continues to elude the public sector. Income inequality is rising and causing a backlash, in some cases targeted at the very interconnections of trade, finance, and people that have fueled the growth of the past three decades. The disruptive forces and trend breaks discussed in this book pose a unique set of challenges for policy makers, affecting several domains—labor, fiscal, trade and immigration policy, and resource and technology regulation.

Labor Policy in a Time of Global Competition and Technology Disruption

In the aftermath of the 2008 recession, job creation remains among the greatest policy challenges in both advanced and emerging economies. At the same time, continued advances in technology that are now encroaching on knowledge work make it easier for machines to replace human work in a range of new fields. Young workers and low-skilled workers are bearing the brunt of the impact on job creation and skill demand in OECD countries.* At the same time, counterintuitive as it may seem, both advanced and emerging economies are struggling with labor shortages. Faced with an aging workforce, some companies are already worried about the impact of retirement. Many are wrestling with growing skill gaps, particularly in the scientific, technical, and engineering fields.5 Labor market imbalances are worsened by the much lower participation rates of women. In Middle Eastern and North African countries, among the fastest-aging populations in the world, less than a quarter of women participate in the labor force. Such imbalances are evident in some advanced economics as well. In Japan and Korea, for example, while 70 percent of men are in the labor force, less than half of working-age women participate.6

Should these trends continue without major intervention, labor imbalances will, we estimate, lead to a shortage of nearly eighty million high- and medium-skilled workers and a surplus of roughly ninety-five million low-skilled workers by 2020. To close the gap, advanced economies will need to accelerate the number of young people completing post–high school education to 2.5 times the current rate. In addition, they will need to provide better incentives to promote training in job-relevant disciplines. In the United States, where there are typically four to five million job openings every month, only 14 percent of college degrees are in STEM fields. For emerging economies, the challenge is to find creative ways to train hundreds of millions of young adults and catch up on secondary graduation rates. In 2012 it was estimated that in order to meet government targets, India would need to hire twice the number of secondary school teachers and add 34 million secondary school seats by 2016.7

Fiscal Policy in a Time of Aging Populations and Rising Capital Costs

From the United States and Europe to Japan and China, many of the world’s largest economies are dealing with the challenge of an aging population and impending retirements. Social safety nets constructed in the last century will be put to the test as the proportion of people over the age of sixty-five years rapidly increases (to one in four) by 2040 in advanced economies, while the share of children stays at a virtual standstill. China is expected to see public pension expenditures rise from 3.4 percent of GDP today to 10 percent in 2050. Thanks to the amplifying forces of the aging population and health-care inflation, public health-care costs are expected to rise even faster. In the United States, where Medicare and Medicaid already cover a huge swath of the population, public expenditures on health care are expected to more than double, to nearly 15 percent of GDP, by 2050.8

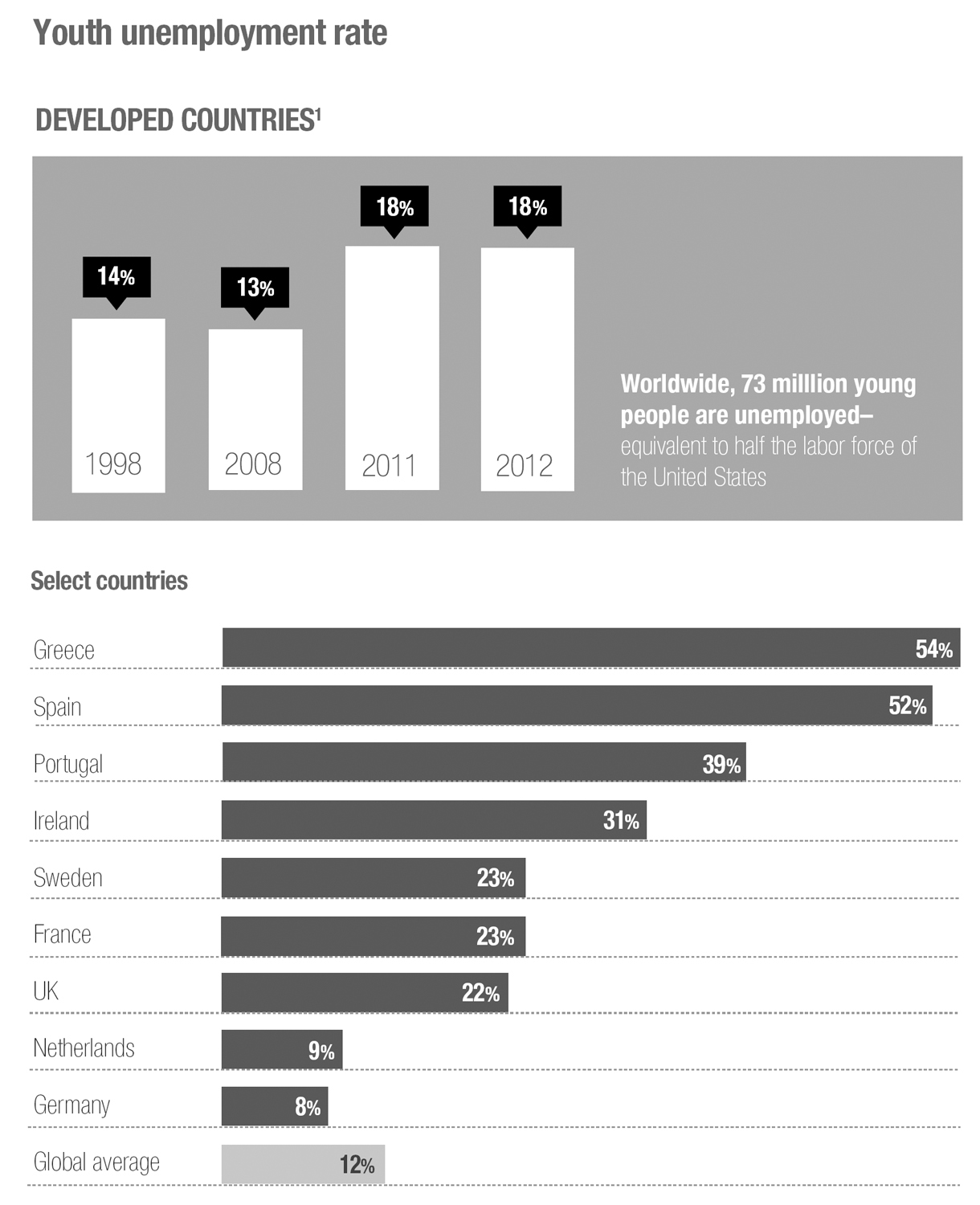

Youth unemployment is high and rising, putting an entire generation at risk

1 Includes the EU-27 and other wealthy economies, such as Australia, Canada, Japan, and the United States.

SOURCE: ILO Global Employment Trends for Youth, 2013; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

The timing of the impending public sector expenditure “bomb” doesn’t help. As the era of historically low interest rates ends, the cost of capital could start to rise. That spells trouble for governments that are presiding over massive pools of floating-rate debt that constantly needs to be rolled over and refinanced. The combined balance of global fiscal deficits was at an unprecedented $4 trillion in 2011, and total government debt stood at 120 percent of GDP, putting pressure on the ability of governments to provide services.9 The European Commission projects that the graying population will impose an additional “off-balance-sheet commitment” of 3 percent of GDP by 2030. Should a higher level of growth fail to materialize, this added debt would require tough fiscal tightening.10

Trade, Immigration, and Monetary Policy in a Time of Global Integration

Rising global prosperity and increased digitization have combined to accelerate the flow of trade, finance, people, and data across borders. And as we’ve noted, the more a country participates in these inflows and outflows, the greater the economic benefit. Growth in economic activity between countries contributes up to 25 percent to global GDP growth each year.11 Yet the public—and certain elements of the business and governing elites—is often wary of participating in such activities, in part because they create obvious dislocations. Global trade is routinely blamed for job losses. Capital flows can be volatile and difficult to manage. Anti-immigration sentiment is high in many countries, developed and emerging alike, and can target legal as well as illegal immigrants. And many policy makers highlight the dark side of increased connectivity in the form of higher exposure to global shocks.12

The strain of the recession, austerity, and the fragile recovery have combined to stretch social safety nets and given rise to anti-immigration sentiment not just in Europe but also in countries traditionally built around migrant workforces. Singapore has historically been friendly to immigrants, and one-third of its residents are born elsewhere, but it is reducing national quotas for foreign workers.13 “What we are doing is to put in place measures to nudge employers to give Singaporeans—especially our young graduates and professionals, managers and executives—a fair chance at both job and development opportunities,” Tan Chuan-Jin, then acting minister (now minister) of manpower, said in 2013. “Even as we remain open to foreign manpower to complement our local workforce, all firms must make an effort to consider Singaporeans fairly.”14 History suggests that these sorts of preferential policies, which are difficult to unwind once established, are likely to reduce potential growth in these locations by hampering immigration of skilled workers.

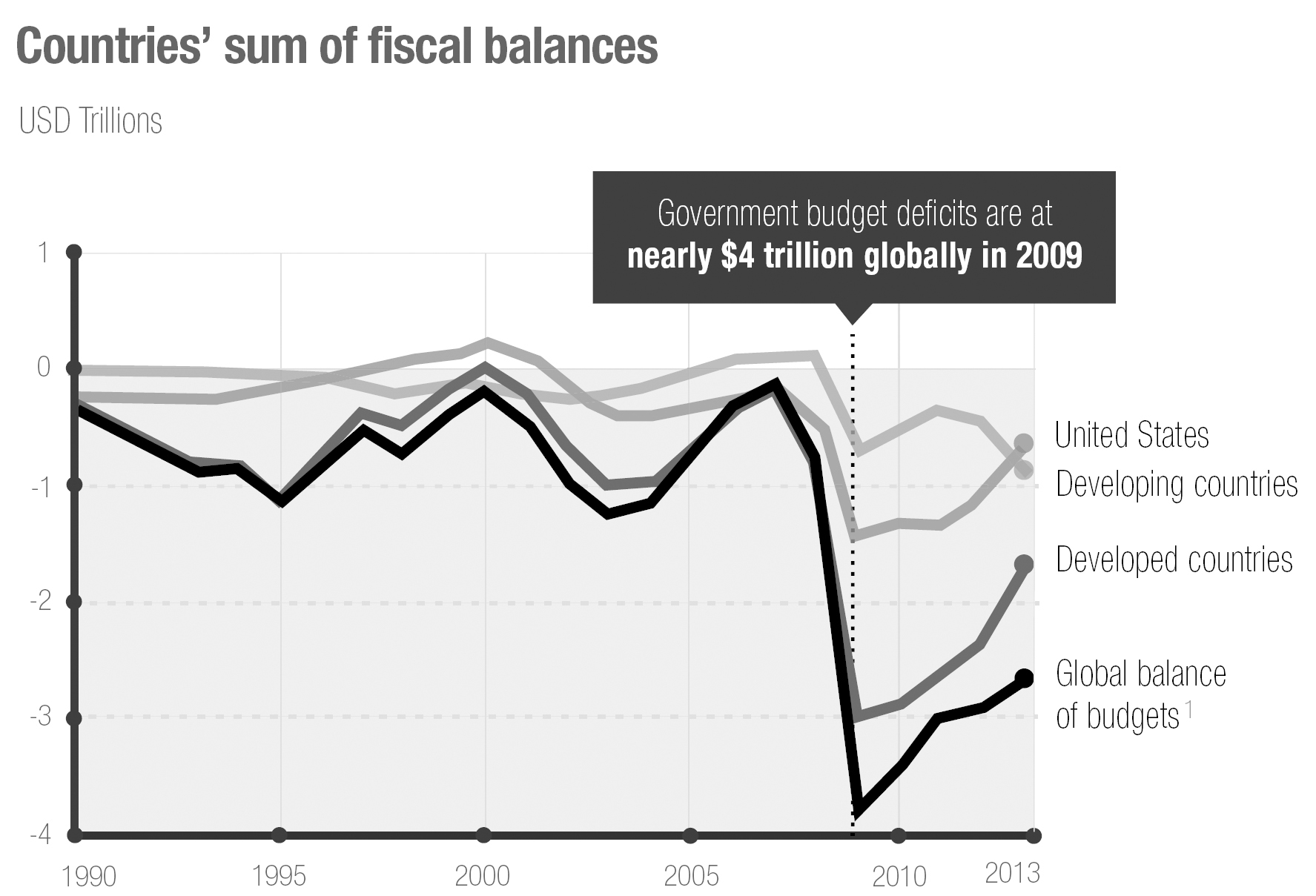

Declining budgets and high levels of government debt are stretching government resources

1 Sum of developing and developed countries’ fiscal balances.

SOURCE: EIU World Database; McKinsey Global institute analysis

Inequality in a Time of Productivity Growth

Global inequality between countries is shrinking as China and other emerging economies grow rapidly. With their newfound prosperity, they continue to reduce the income gap between themselves and advanced economies by increasing productivity. At the same time, however, income inequality within countries is widening. Since the mid-1980s, in all but four of the countries in the OECD, incomes have risen significantly faster for the top decile of households than for the bottom decile. The handful of exceptions that had faster income growth in the bottom decile include Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain, each of which has suffered a remarkably deep recession.15

Advanced economies are not the only ones facing this challenge. The Gini coefficient (a measure of income distribution within a nation) for China and India has also increased in the last two decades, in part due to a wide and growing disparity between rural and urban areas. In China in particular, the cities most connected to global trade and financial flows—Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen—have far outpaced less connected cities in the interior.16 Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, summed up the issue: “Put simply, a severely skewed income distribution harms the pace and sustainability of growth over the longer term. It leads to an economy of exclusion, and a wasteland of discarded potential.”17

Debate rages about the source of the growing inequality and indeed about whether there is even a single source. One thing is certain, however. Productivity plays an often-overlooked role. According to some research, productivity growth confined to a small segment of the population tends to worsen inequality. When only the wealthy become more productive, they reap a disproportionate share of the benefits. Consequently, greater and more widely distributed productivity growth could then be a solution to rising inequality. And yet at a time of weak demand growth, economic policy makers everywhere often face a public perception that productivity kills jobs. History teaches otherwise. In every rolling ten-year period except one since 1929, job growth and productivity growth have gone hand-in-hand in the United States.18 Unfortunately, conventional wisdom that comes to the opposite conclusion has proven difficult to dispel.

The demographic trends discussed in earlier chapters makes the productivity imperative even more critical over the next fifty years. The rapid global GDP growth of the previous half century, about 3.6 percent annually on average, was driven by growth in both the world’s labor force and in its productivity. For instance, an analysis of twenty countries, including the G19 and Nigeria, shows that there are 2.3 times more employed workers today compared to fifty years ago and that each worker generates 2.4 times more in output than he or she did fifty years ago. Today, however, the demographic trends fueling growth are weakening and even reversing in some countries. The rate of global employment growth could drop to just 0.3 percent annually thanks to declining fertility rates and aging populations, and the world is likely to hit peak employment at some point in the coming half century. As a result, productivity gains will be instrumental in driving GDP growth. To sustain the recent growth trajectory, productivity will need to accelerate to nearly twice its historical rate. Simply maintaining the fifty-year historical rate of productivity growth over the coming fifty years will cut the global economic growth rate from 3.6 percent annually to 2.1 percent annually. Rather than expand sixfold, as it did in the past fifty years, the global economy would only expand threefold in the coming fifty years.

Where will this productivity growth come from? In our research, we find that about three-quarters of the needed growth can come simply from “catch-up” improvements, that is the broader adoption of existing best practices. The remaining one-quarter will come from technological, operational, or business innovations that go beyond today’s best practices. But capturing this potential is not easy, as it requires broad and relentless change across industries and countries. Without a supportive environment—flexible labor markets, sufficient investments in skill development—productivity alone won’t overcome the substantial demographic headwinds. We have identified ten enablers required to foster strong productivity growth: the removal of barriers to competition in service sectors; a focus on efficiency and performance management in public and regulated sectors; investment in physical and digital infrastructure, especially in emerging markets; fostering demand for, and R&D investment in, innovative products and services; regulations that incentivize productivity and support innovation; exploiting data to identify improvement opportunities and catalyze change; harnessing the power of new actors in the productivity landscape through open data and digital platforms; encouraging labor-market participation among women, the young, and older workers; adjusting immigration systems to help bolster skills and the labor pool; improving education and matching skills to jobs; and making labor markets more flexible.19

The productivity imperative applies especially to government, and in particular to its impact on the consequences of inequality. In many developed countries, public spending makes up 50 percent or more of GDP, while government employment accounts for between 15 and 20 percent of the total labor force.20 Yet when it comes to productivity gains, the public and quasi-public sectors such as education and health care are laggards. In the G8 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States), improvements in government performance could unlock annual value of $650 billion to $1 trillion by 2016.21 In India, roughly 50 percent of public spending on basic services, including up to two-thirds of spending on health care, family welfare, drinking water, and sanitation, does not reach its intended beneficiaries because of inefficiencies, corruption, and diversion to other projects.22 Public-sector productivity is critical to simultaneously tackle cost inflation in health care, rising public-sector costs, the emerging labor skill gap, and other societal challenges.

Standards in a Time of Technology and Resource Disruption

Major technology disruptions are occurring with increasing frequency. At the same time, new technologies are being adopted faster than before, whether in software, Internet services, or hardware. Companies and individuals are not the only ones involved. Governments play an important role in supporting research and development and in creating basic enablers for the private sector. However, the uncertainty and speed of technological change make it difficult to decide what R&D to support and how and what sort of talent and infrastructure to invest in. Policy makers who understand technology can harness it to improve societal outcomes in a range of ways—from providing health care, education, and other public services to improving productivity and making governance more transparent and accountable.

In addition, governments need to constantly revise legal and regulatory frameworks to ensure their relevance. California legislators are now trying to prepare for advances in self-driving cars; officials from several state departments meet routinely to try to understand all of the ways in which the technology requires legislative changes—such as in liability insurance, drivers’ licenses, safety requirements, and infrastructure needs. They understand that the benefits of being early—especially the potential jobs that could be created in related businesses—are sufficiently large to offset the difficulties of being early.23

Governments around the world are also facing new challenges from increasing global connectivity in data and communication flows. In the wake of the recent NSA scandal in the United States, many countries are rethinking data privacy and protection laws. In Germany, the backlash has been particularly strong, with plans for resuming counterespionage measures and rising enthusiasm for a secure Euro-link network.24 Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, pointedly stated, “We’ll talk with France about how we can maintain a high level of data protection. Above all, we’ll talk about European providers that offer security for our citizens, so that one shouldn’t have to send emails and other information across the Atlantic.”25

The regulatory frontier extends to resources as well. Some technology disruptions directly affect the resource sector. Fracking technologies have unleashed a shale gas revolution in the United States, attracting regulatory attention to the environmental effects of methane emissions, water contamination, and related issues. Globally, resource prices between 2000 and 2013 more than doubled, as a response to demand in emerging economies and rising supply and exploration challenges. At the same time, average annual resource price volatility over the last thirteen years has been roughly three times that witnessed in 1990s.26 The impact of technology disruptions in concert with high and volatile resource prices is increasing pressure on governments to act as efficient regulators.27

IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE GOVERNANCE

The political leadership challenge triggered by these trend breaks is made even more urgent by the growing number of outlets for public expression and participation. Citizens around the world demand that governments deliver public services in shorter time frames, of consistent quality, and often at lower cost. In times of tightening budgets, short election cycles, and instant feedback loops, the room for error by public-sector leaders is small. From Hong Kong to Ukraine, from Egypt to Brazil, it is common to see large groups of citizens, impatient for change, taking to the streets. After a thirty-year decline, sovereign debt in default has been rising (as a share of global debt and global GDP) since 2011, indicating that we may be at the start of yet another default cycle; emerging-market debt crises triggered the last one, in the 1980s.28

Often, the challenge for public sector officials isn’t lack of vision, but short time frames, competing priorities, and flawed delivery. Many governments have risen to the occasion; an Asian country reduced street crime by 35 percent in the first year of a transformation program. A South American government reduced hospital waiting lists by 80 percent and increased by more than 50 percent the number of top graduates choosing to become teachers. An emerging-market government introduced a social-security scheme to hundreds of thousands of workers in two months. In each of these cases, policy makers used what McKinsey calls a Delivery 2.0 approach—a well-designed program with appropriate metrics, experimental “delivery labs,” small and high-powered execution teams, visible support from leaders, and a culture of performance accountability.29 Beyond delivering results, communicating them effectively is vital. Publicly available dashboards that document performance in real time can establish transparency and instigate conversations about how to improve services.

Just as trend breaks have forced many businesses to reassess their strategy and reimagine their business assumptions, government has to do the same. As policy makers try to adapt, these trend breaks raise three interesting questions about the nature of government in the future: the size of government, the degree to which it should be centralized or localized, and its overall role.

Size: The first question relates to the size of government in the future. For the OECD, average government spending is about 45 percent of GDP. But there is wide variation, with government spending accounting for more than 55 percent of GDP in countries such as Denmark, Finland, and France and 30 percent or less in South Korea and Mexico. In Norway, the public sector employs 30 percent of the workforce; in Japan, the proportion is less than 10 percent. Most countries have seen government employment remain the same or shrink marginally over the past decade, and most of the jobs are in general administration—even in countries with large public-sector companies.30 Ultimately, the effectiveness of government matters more than its size. But as policy makers think about the impact of trend breaks, it is worthwhile to ask the question: Is there a “right” size for their government? This matters even for policy makers looking to e-governance as a way to improve delivery. The economies and central government employment of the United Kingdom and Italy are roughly the same size, but the United Kingdom spends four times more per government employee on information technologies than does Italy.31

Centralization: The second fundamental question relates to the organization of government and whether policy should become more local, more national, or, indeed, more global. In Ireland, the central government accounts for 76 percent of all government spending and 90 percent of public-sector employment. But in Germany and Switzerland, which have more robust state and regional governments, the central government accounts for less than 20 percent of spending and 15 percent of employment. A great deal of decision making has devolved toward cities and states, whether it is for infrastructure project selection in the United States or workforce training in Germany. In the United States, individual states are responsible for nearly 85 percent of all government investment. Spain has become more decentralized in the past decade, Norway has become more centralized—at least as measured by public employment—and most other OECD nations haven’t seen a change.32 Furthermore, as global connections have grown, we have also seen the rise of more global or multilateral decision authorities, such as the European Union’s monetary regulator, the International Criminal Court, and ASEAN’s trade officer. Governments are also increasingly cooperating on knowledge sharing and policy design. The Alliance for Financial Inclusion, now one of the largest developing-world organizations, was founded in 2008 and designed specifically for policy makers from developing countries to share knowledge and discuss policy options for financial inclusion.33 With increasing interconnectivity, the question of which government policy decisions should become more local and which ones more national or supranational is becoming very pertinent.

Role: The third question relates to the future role of government. In general, central governments focus on funding major outlays such as social protection and defense; local governments focus on funding and delivery of education, housing, and other community-related activities. Will we see government getting out of many of its current activities (such as infrastructure construction) and plunging into new areas (such as resource efficiency)? Overall in the OECD, the largest spending category is social protection—pensions, unemployment, disability—which makes up more than 35 percent of total spending. But large emerging economies such as China and India, which have yet to construct robust safety nets, only spend 15 to 20 percent on such social welfare programs. Korea spends only 13 percent of its budget on social protection, while it spends more than 20 percent on economic efforts to promote domestic industry—four times the share in the United Kingdom. The US government spends 21 percent of its budget on health care, but Switzerland spends only 6 percent. Greece spends 8 percent of its budget on education, while Israel and Estonia each spend nearly 17 percent.34 Given these large variations, is there a “right” mix of policy priorities, and how should a government achieve this mix?

Funding is only one way to measure what a government actually does. Broadly, policy actions geared at achieving desired outcomes tend to fall into one of three categories: incentives, regulation, and information. Around the world, governments are employing all three approaches to navigate the changing landscape with agility, innovation, and best-in-class implementation.

Using Incentives to Accelerate Change

Typically, we think about incentives as carrots and sticks that the government provides to the private sector. But government can often craft incentives that induce government itself to work more intelligently. Germany’s Hartz labor reforms used incentives to retool Germany’s labor agency, such as changing performance goals for caseworkers and more targeted placement and training programs. Along with incentives for companies to hire the long-term unemployed and retain workers in periods of weak demand, these efforts played a crucial role in changing the country’s labor market condition.35 Other job-creation initiatives underway that utilize incentives in both advanced and emerging economies range from export promotion to infrastructure, providing social services, and entrepreneurship. The US government’s National Export Initiative seeks to promote job creation in domestic services and advanced manufacturing industries by making it easier for companies to access export markets.36

China, which has the world’s largest diaspora and largest overseas student population, is using incentives to lure high-skilled professionals back home as part of its National Talent Development Plan 2010–2020. The Thousand International Talents Program targets Chinese engineers and scientists living abroad, offering inducements such as large research grants, housing assistance, and tax-free education allowances for the children of those who return and work full-time in China for at least three years. Such incentives, combined with China’s formidable economic momentum, encouraged nearly three hundred thousand students to return in 2012 alone.37

Several countries are using incentives to cope with the demographic and economic challenges of an aging population. One key effort toward bolstering the ranks of the employed is to include more women. In 2012, only 51 percent of working-age women participated in the labor force globally, compared with 77 percent of men.38 Denmark has instituted a host of incentives, including the provision of a child-care facility within three months of a parent’s request, such as day care, kindergarten, or leisure time centers and school-based centers. As a result, over 80 percent of Danish infants and toddlers and over 90 percent of Danish children between the ages of three and five years are in regular child care.39 By 2009, Danish women aged fifteen to sixty-four had a labor participation rate of 76 percent, one of the highest in the OECD.40 Of those women in the labor force, more than 95 percent are employed.41

Conditional cash transfer incentives have proven particularly effective in poverty reduction efforts. In Mexico, Oportunidades has been credited with a 10 percent reduction in poverty within five years of its introduction,42 in part because the program is designed to provide cash payments for families who meet certain conditions such as health clinic visits and school attendance. More significantly, it has created strong financial incentives for families to invest in efforts that boost human capital over the long term.

Government can also provide incentives in the form of forward-looking procurement policies and standards. From the telegraph and railroad to semiconductors and mobile phones, governments have long played a direct role by providing critical early demand for unproven technologies. The US Navy has been a customer of energy-saving technologies, including fuels; it led the shift from coal to oil in the 1900s, then to nuclear in the 1950s. Faced with persistently high oil prices, the Navy is now spurring demand for biofuels and energy-efficient technology. But incentives must be carefully designed to avoid the risk of unintended consequences and creating market distortions, as agricultural subsidies often do.43

Using Regulation to Direct Response to Change

Government’s power to regulate—to set standards and define the rules of conduct and markets—can play a vital role in modernizing economies and preparing for the future. Regulation can prove a particularly effective tool in places where market failures are obvious and structural issues inhibit adoption of best practices. Shareholders of large financial institutions can’t effectively ride herd on the risk-taking actions of executives, so regulators must impose capital standards and supervise them carefully. Making buildings more energy efficient requires owners to make upfront investments that they may not be able to pass along directly to renters. As a result, smartly designed industry-wide standards can be useful.

To address the problem of aging populations, some countries have extended the legal retirement age, in some cases by up to two years. That’s a start, but it’s not nearly sufficient to keep pace with the demographic changes the world is seeing. A recent analysis of forty-three mostly developed countries found that between 1965 and 2005 the average legal retirement age rose by less than six months.44 In the same period, male life expectancy rose by nine years. In graying Europe, Danish legislation recognized the impending pension time bomb early, and the country decided to index the pension age to life expectancy and place restrictions on early retirement. As a result, Denmark’s population of people aged fifty-five to sixty-four has a higher labor participation rate (58 percent) than the average EU country (less than 50 percent) and will have the highest retirement age (sixty-nine years) among all OECD countries by 2050.45 In response to the demographic tide, Japan’s government introduced compulsory long-term care insurance contributions by citizens over age forty in the early 2000s.46

Countries—particularly countries with underdeveloped financial institutions or specific risk exposures to global flows—use the regulatory approach to manage their vulnerability to global participation. For instance, governments have crafted various regulatory responses to rising capital inflows, ranging from short-term, high-intervention measures to systemic longer-term changes to their financial markets. Regulation is usually most intrusive when markets are least developed.

Chile, whose economy is relatively modern but disproportionately reliant on copper exports, maintained its openness to foreign capital but maintained a conservative fiscal policy stance. In 2007, the government set up the Economic and Social Stabilization Fund with an initial contribution of $2.6 billion. The fund was set up specifically to reduce Chile’s dependency on global business cycles and revenue volatility from copper price fluctuations.47 It invests primarily in government bonds, and a portion of its assets can be used to finance deficit spending or pay down government debt. The fund’s assets have grown to about $15 billion, and Chile has become one of the most financially deepened* countries in the region. The IMF recently nominated Chile as a representative example of resilience to fluctuations from global flows.48

Governments have used regulation to mandate social, environmental, and other broad outcomes in response to global trends, while letting industries sort out the technologies needed to meet the targets. In these cases, there is a social consensus about what needs to happen but no agreement on how to get there. And getting there is most of the battle, because market participants may be wedded to technologies linked to whatever environment preceded the trend break. For example, the advent of sharply higher energy prices caused the promulgation of sharply higher automobile mileage requirements in the United States. This, in turn, has spurred a host of innovations—electric vehicles, hybrid power trains, replacing steel with aluminum, and integrating start-stop engine technology. New regulatory requirements on food safety and tracking in the EU and the United States are generating industry interest in data platforms and advanced analytics throughout the supply chain.

Examples of regulation abound in the policy response to resources. In the United States, Ohio, Texas, and Pennsylvania allowed the deployment of fracking, which the state of New York bans.49 In Europe, public concerns about the environmental impact of shale gas have led to drilling bans in Bulgaria, France, and Germany.50 To encourage recycling, Sweden has used landfill taxes and the inclusion of recycling costs in the price of goods. As a result, about 99 percent of household waste is either recycled or burned to create electricity and heat.51 The German government is using regulation to hasten the transition to renewables and has mandates for electricity efficiency.52

Harnessing Information to Improve Productivity

Big data isn’t just for apps and e-commerce. Information is a critical tool to improve public-sector productivity, especially in an environment where there is pressure to continually improve productivity and quality of service. Governments are starting to prioritize information as an effective tool for better management of the resources and tasks they steward, such as education, health care, matching labor supply and demand, and even defense and security. And government is supporting industry in providing information that consumers can then use to make better decisions. Central European countries—Austria, Germany, and Switzerland in particular—have long been models of industry-based vocational education. There, vocational programs target over two hundred different occupations and are intended to ensure a match between labor supply and demand. The Swiss government oversees certification, and potential employers help define needed skills and shape curricula. Other countries have similar models, but on a smaller scale and targeting specific sectors. Brazil’s government is taking the lead via Prominp (National Oil and Natural Gas Industry Mobilization Program) to convene firms, universities, and unions to improve education and keep Brazil’s oil and gas sector competitive.53

Under President Nicolas Sarkozy, France launched the General Review of Public Policies. Dubbed “do more with less,” it is aimed to reduce the country’s public expenditure and provide better service quality for citizens as well as promoting a “culture of results.” Among other actions, the review promoted service improvements in high-visibility areas leading to greater citizen satisfaction, such as the introduction of fifteen quality-of-service indicators, including waiting times in accident and emergency departments.54

Another step is identifying and monitoring the economy’s main productivity drivers. Even among the best-performing countries, a wide distribution of performance exists within sectors. Within the quasi-public sector, countries have both excellent and poorly performing hospitals and schools. The best performers have usually understood and implemented practices honed in the private sector—lean principles, data analytics, smart procurement and performance management—to great effect.

Technology and big data provide another avenue for policy makers to unleash productivity improvements across all public services. In Kenya, the national government launched an open data portal to share previously difficult-to-access information spanning realms such as education, health, and energy. This data publication has led to the development of over one hundred mobile applications and an estimated potential savings of $1 billion in procurement costs.55 Estonia’s 1.3 million residents can use electronic ID cards to vote, pay taxes, and access more than 160 services online, from unemployment benefits to property registration; even private-sector firms offer services through the state portal.56 The Brazilian Transparency Portal publishes a wide range of information that includes federal-agency expenditures, elected officials’ charges on government-issued credit cards, and a list of companies banned from contracting work with the government.57

NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR BUSINESSES

As policy makers reset their intuitions and change their approach to governance, the private sector will be affected as well. The rules of the game may change in some areas; in others, new opportunities will present themselves. Already we are seeing examples of companies benefiting from the policy response to deepening global engagement, collaborating on infrastructure and education initiatives, and addressing resource and technology issues.

The government response to technology trends determines the opportunity for new markets for everything from real estate portals to consumer finance. Government regulations on e-commerce and data exchange—and the willingness to share public data with private companies—allow these new markets to develop. Take real estate as an example. Location selection can be optimized through use of geospatial, commuter traffic, and infrastructure data. Portals that aggregate real-time information on property availability, prices, recent transactions, and taxes with other relevant nonfinancial information can help match buyers and sellers effectively. Aggregators such as Zillow are substituting for traditional brokers; they allow users to search for properties based on custom preferences and then generate automatic valuation estimates. Consumer finance is another interesting example. Many new players are emerging and harnessing the power of open data to help consumers better navigate increasingly complex and proliferating financial products. Wallaby, a venture-backed US firm, recommends which credit card to use for different types of purchases in order to maximize rewards. BillGuard pulls together information from all its users’ credit card transactions to highlight transactions and payments that are unwanted or even fraudulent to its users.

The global smart city technology market—smart energy, water, transportation, buildings, and government—is expected to grow from $9 billion in 2014 to $27.5 billion by 2023.58 Companies are already working with pioneering cities such as San Francisco, Barcelona, and Amsterdam. The growth in the global smart city technology market has fueled growth in adjacent sectors, such as video surveillance.

An opportunity also exists to capitalize on the search by governments for partners to provide public services. Such partnerships span countries and sectors. In some of the world’s most water-stressed areas, including parts of Africa and Latin America, Coca-Cola has partnered with international agencies such as the World Wildlife Fund and the United Nations Development Programme to improve access to water and sanitation, protect watersheds, provide water for productive use, and raise awareness about water issues. In the United States, private sector partners are playing a role in high-profile infrastructure projects, including Miami’s port tunnel, Washington, DC’s streetcar line, and Atlanta’s multimodal transport hub. In India, a massive project to train a five-hundred-million strong workforce by 2022 is taking shape under the auspices of the National Skills Development Corporation, a public-private partnership in which the private sector holds 51 percent of equity—including representation from companies in sectors as wide ranging as construction, aerospace, retail, and life sciences.

Danish firms provide a good example of the opportunities resulting from policy changes in resources. As Denmark successfully transitioned from oil to renewables, government demand and clear policy goals allowed Danish companies to make early investments that helped them become world leaders in the sector. Wind turbine maker Vestas capitalized on its home market experience to expand globally—initially in important markets such as the United States, then ramping up across Europe and Asia. The market for renewables has grown in these parts of the world over the past decade, and Vestas has recorded over 20 percent annual revenue growth through the 2000s. Today, the company’s global revenue exceeds €6 billion.59 Other domestic beneficiaries of the Danish government’s energy initiative include Grundfos, the world’s largest pump manufacturer, and Danfoss, a producer of energy-efficient components.60

![]()

The trend break era is imposing uncertainties and pressures on governments and policy makers that are as significant and meaningful as those it is placing on companies and executives. Increasingly, public leadership will be judged by its ability to marshal resources and build consensus to face these challenges head on. Ultimately, it is difficult to prescribe a specific regimen for the appropriate size and shape of government. Each country must make these decisions for itself. But regardless of a government’s situation—expanding or contracting, developed or developing, in surplus or in deficit—it must strive to respond quickly and with agility. Doing so will allow governments to insulate and protect themselves from some potentially threatening trends. More significantly, it will allow the public sector to take advantage of the enormous opportunities being presented. The intelligent deployment of incentives, regulations, and data is a requirement for success.

![]()

*Thirty-four mostly high-income countries, including the United States, Japan, and Western European nations, plus Mexico, Turkey, and Hungary.

*Financial deepening is a term that indicates that financial services and access to capital (along with banks, financial institutions, and capital markets) are becoming more accessible in a country.