CARYL CHESSMAN, WRITER

BY JOSEPH E. LONGSTRETH AND ALAN BISBORT

For years, Caryl Chessman had no means of reaching the world outside his concrete-and-steel cubicle—the 4½-foot-wide, 10½-foot-long, and 7½-foot-high cage known as Cell 2455, Death Row—other than through the written word. Letters formed the basis on which he maintained human relations and kept in touch with other kindred minds and spirits. He maintained a large correspondence for many years, and his letters, as his correspondents were keenly aware, were lengthy and detailed. They frequently dealt with the problems of the people he was writing to, and his pages of encouragement to other would-be authors reveal a little-known aspect of his personality. His generous and courageous words helped sustain many a falterer; his strengths reached out from the pages of his letters.

One measure of literary success is the number of people an author reaches. In this respect, Caryl Chessman scaled the pinnacle of writing achievement. Through the large sales of his four published books, which were translated into more than a dozen languages, he communicated with millions of people around the world. The impact of his works cannot be denied, and few authors have aroused comparable empathy or antipathy.

If one wished to evaluate a writer merely as a storyteller, the most casual reading of passages from Caryl Chessman’s published books—perhaps most notably Part Two of Trial by Ordeal, “Who Are These Doomed?”—establish the author as a first-rate raconteur. Here, he opens a window onto a world of institutionalized death, bringing to life the collective carcass of capital punishment by introducing us to condemned neighbors like Jerry, Sandy, Gene, Buck, and Honest Mike, as well as to the sixty men who have walked past his cell on their way to the gas chamber: “One was an old dodderer with a persecution complex. Another was a frightened youngster with a harelip who was executed before he really had to shave. They were tall and short and in between; thin and fat; young and old; religious and irreligious; bright and dull. . . . Among them were men of Indian, African, Irish, Spanish, Jewish, Polish, French, Scandinavian, and English blood.” Into this world crept The Incher, “a stunted mouse with distinctive and comical face markings” that won the affection of some of the condemned men. Soon enough, the prison officials put an end to the love-fest, sending out for the exterminator to rid Death Row of its mice. The unfolding scenario would be classic satire if it weren’t heartbreakingly real.

From almost any viewpoint, Caryl Chessman was an author whose written words have left an impression that can’t be ignored. In the twelve years between his sentencing and his execution, Chessman shaped one of the most remarkable bodies of work in American legal history: three wide-selling memoirs (Cell 2455 Death Row [1954], Trial by Ordeal [1955], and The Face of Justice [1957]) and one novel (The Kid Was A Killer [1960]). His books earned the praise and support of some of the most respected figures of his time—from Eleanor Roosevelt to Albert Schweitzer, from Aldous Huxley to Marlon Brando. His face peered out stoically from the cover of Time magazine.

What history and time may glean from the Chessman writings, we cannot determine; and perhaps those of us who were intimately involved with his life and death and his publications are still too close to the whole affair to have a fully objective view. It is the considered view of many that, with the hysteria and dramatics of impending executions removed, and with the truly melodramatic circumstances of Caryl Chessman’s life and death receding into memory, the man’s literary works will gain in stature and significance. Few American prisoners have written as well or as com-pellingly. Chessman was not just a good writer; he was a good thinker, with a clarity of mind and an ability to bring his thoughts directly to the page—given the soul-numbing conditions under which he labored—that have evoked the great humanists. His books should remain in print in perpetuity, as time slowly reveals the depth of which this unique person was capable.

It was by way of writing that I first met and got to know Caryl Chessman. He sent me a letter over the transom. I was in New York, where I had established a literary agency with some friends, Critics Associated. Caryl had sent a manuscript about his life to Simon & Schuster and asked them to send him a list of accredited agents. My name was on that list. Caryl was interested in music, an aspect of his life and personality that no one has commented on in all the accounts then or since. At the same time this was going on, I had translated and arranged a libretto for an opera that was being produced and was running in New York, Mozart’s Don Pedro, as staged by the Lemonade Opera. It was well reviewed by the press, and my work was singled out by name in many reviews. Caryl loved music, and he was reading all these reviews in the New York papers and my name was in the reviews. Upon such a tenuous connection hung the fate of America’s best-known prison writer. He wrote me:

For a long, long time I have known there was a story that cryingly needed to be told, and, after winning a stay of execution approximately 17 months ago that literally jerked me back from the grave and psychologically from beyond, the grave, I set out to tell that story, not, be assured, in a penny dreadful fashion, but still in a fast-paced and thoroughly readable way.

Fortunately, San Quentin’s warden, Harley O. Teets is a modern, progressive penologist. Not only did Harley Teets encourage me to write my book, but he made it possible for me to do so. He permitted me exhaustively to document it, research it. Equally fortunately, his boss, Director of Corrections, Richard A. McGee, who heads one of the best, largest and most enlightened correctional programs in the Nation, has speedily cleared the book and approved my sending it to a publisher. Since it tells a vitally important story of the function of California’s Department of Corrections and the urgency of public understanding and backing of that function, I am confident you will have the cooperation of that department in the publishing and publicizing of Cell 2455, Death Row.

This, of course, is not to say that the department will be any active partner either in the publication or promotion, but it is to say that its members concerned will permit you and I [sic] freely to work together in bringing my book to the reading public. In turn, it is my voluntary desire to cooperate fully with Director of Corrections Richard A. McGee and San Quentin’s Warden Harley O. Teets. . . .

All of which is one way of leading up to an introduction . . . [but] my manuscript must speak for itself.

Attached to this cover letter was a manuscript: Cell 2455, Death Row.

These letters to book agents and editors are frequently lengthy and boring, expounding on many subjects only vaguely connected with the script in question. After experiencing a few thousand cover letters, one acquires a kind of sixth sense, a feeling about them. The ability to look beneath the cover letter comes to the fore, and one can tell rather quickly whether or not the author is writing seriously, or is a serious writer. Caryl Chessman’s letter was arresting—not just because he stated calmly that he was a condemned man, nor that he had “known every kind of criminal, from the petty and obscure to nationally known killers and ‘public enemies’” and had been psychiatrically diagnosed as an “aggressive psychopathic personality”—but because a sense of real urgency and a ring of sincerity gripped those of us in New York who read it.

That cover letter was written by a writer, a man who was capable of putting words onto paper in a fashion that compelled one to read on: forced one, by the way the words were put together and by the truths they contained, to pay attention to what the writer was saying, and to carefully weigh the meaning in the flow of words. Whether the man had a story of sufficient import to tell, the discipline to sustain a book, or the objectivity to analyze and report convincingly, remained to be seen.

The first steps, after the rewarding and exciting—indeed electrifying, not to say profoundly disturbing—experience of reading the manuscript of Cell 2455, Death Row, were very important. We had to make sure that this unknown, condemned man had actually written this script. Such concrete information was quickly obtained from the very officials mentioned by the author. Warden Teets and Mr. McGee sent letters, upon request, attesting to two important facts: first, that Caryl Chessman was the author of his manuscript, and that they knew this firsthand; second, that Chessman was legally within his rights to negotiate contracts for the disposition of his property, the product of his mind, and that such negotiations had their approval and full awareness. They assured me of their cooperation, and for some time they did cooperate in full.

Since it was almost unbelievable to me, initially, that a man in Caryl Chessman’s position, and with his long record of crime, had actually written such a powerful document—a document that I believed unique in the annals of publishing—I have been able to understand why the question of Chessman’s authorship has come to other minds as well, even after its publication. But I immediately took steps to get at the truth, and I remain shocked that others, especially those in highly responsible positions with the press, made statements questioning Chessman’s writing abilities without any apparent effort to do the same thing I had done. All that it would have required of these journalists was to have made a couple of phone calls.

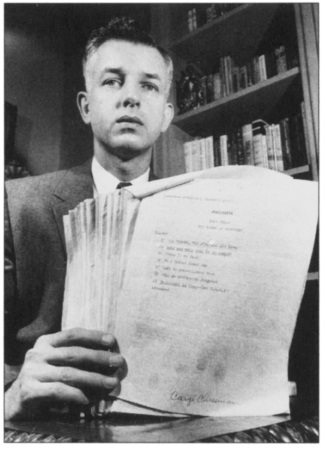

Several leading syndicated columnists accused Chessman of having a “ghost,” and in some instances they made it clear that they believed I had actually written the Chessman books. To curtail these rumors, Chessman eventually took to putting his fingerprints and signature on every page of his manuscripts.

In March 1957, I showed reporters the original manuscript of The Face of Justice. Chessman signed and fingerprinted each page. Courtesy of Peg Longstreth

Let it be understood, categorically and finally, that Caryl Chessman was, at all times, his own writer. Each and every word of all his works is the word of the mind of Caryl Chessman. True enough, he took full advantage of editorial assistance, of suggestions and recommendations. And, to be sure, Chessman needed editorial direction. He was given, for example, to the excessive use of adjectives, and he sometimes interpolated legal questions into dramatic portions his story, where they stopped the flow of his moving tale. Such flaws were quite natural, considering the circumstances under which the author lived and wrote.

Cuts were made in Chessman’s manuscripts by myself and by Monroe Stearns, the editor at Prentice-Hall. The excised passages were, in and of themselves, worthwhile, but added nothing to the story. In fact, they distracted the reader from more significant passages. In almost every case, Chessman saw the necessity for this help, and appreciated the efforts to make his work more effective.

It should be made clear that, when Caryl Chessman did not want something changed, he was adamant. Sometimes he had good reasons; sometimes his reasons were obscure. Sometimes we agreed, and sometimes we disagreed. Chessman could become angry when a suggested change did not meet with his approval, but no more so than most authors, and considerably less than many. An author who meekly permits anyone to do anything to his works cannot have much faith in the material he has produced. Chessman’s expression of his anger, too, could be forceful. For years, he lived in a world that recognized physical force above all other things. The man himself understood this; in one of the last letters he wrote to me, dated April 26, 1960, he stated:

I am deeply and abidingly grateful for your assistance over the last several years as my literary agent and friend. I am well aware of how trying and even at times how seemingly thankless have been your efforts on my behalf Yet, knowing how intensely I felt about the things of which Fd written, you always persevered.

As you know, for the last 12 years, mine has been a harsh world where, if you failed, you didn’t live to get a commendation for a good try and a pat on the back. It has been a world without next-times, and so perhaps the iron disciplines I had to impose on myself to survive against almost impossible odds on occasion gave the impression that I was a. brusque, unfeeling guy who gave no thought to the sensibilities of others in his drive toward, a goal. lam certain, however, you know how far from the truth this is. Time, circumstance and a complex of other difficulties, though, have combined to make it impossible for me always to communicate with a nice regard for diplomacy.

Caryl Chessman, the writer, spent much of his time on extensive legal research, reading and studying, thinking and evaluating. Measuring Chessman’s putting of words on paper, one cannot ignore the vast number of pages of legal documents that he produced during his years on Death Row, for his own legal case and for the many other condemned men he helped in this regard. To count the pages alone would be staggering. Court officials and judges throughout the country were amazed, sometimes awed, and often irked, by Caryl Chessman, the legal writer. One brief alone, the Appellant’s Opening Brief in the Supreme Court of California, dated September 2, 1958, contained 318 pages. And the page entitled NOTE XVI begins with two simple statements:

“There are several different transcripts before the Court on appeal. These total some 60 volumes.”

From this mountain of legal documents grew the oft-repeated charge that “Caryl Chessman made a mockery of the law.” A man facing death does not mock: he fights. Chessman’s wealth of experience in writing legal documents—in fighting, not mocking, death—undoubtedly had a marked influence on his writings in other spheres. Even in personal letters, he could scarcely restrain himself from careful documentation, from citing a source, an authority for a certain remark.

The creative writer, the imaginative writer, also crept into Caryl Chessman’s legal writing. In these works, he was acutely aware of the unfolding drama involved, and his keen sense of the dramatic permeated the pages. Carefully annotated and researched though they were, a Chessman brief always had a sense of scene, a feeling of being staged, being witnessed, being read aloud. One could almost hear the voice behind the powerful words. And in some instances, the dramatics outweighed the facts. How troublesome this must have proved, sometimes, to those who had to read such documents carefully; and yet how refreshing, considering the sterility of most legal documents.

It is from the sense of drama inherent in these legal documents, even those of but a few pages, and from the narrative drive in his books, that I have often speculated about what the possible future of Chessman’s literary skills could have been, had they not been so conclusively terminated.

As my relationship with Caryl Chessman developed, through extensive correspondence and personal visits to San Quentin and Los Angeles to meet his father Serl and his longtime attorney and friend Rosalie S. Asher, I came to know a great deal about Chessman’s literary strivings, their beginnings and their tribulations. In truth, they differed little from those of many people, except that he finally reached his goal and became a success, a published author in many languages.

The urge to write, to be a writer, stirred inside Caryl Chessman many years before his first publication. As a child he wrote poetry, often reading his work to his mother, Hallie. He tried, as he grew older, to write short stories, and as a youth sent his grandiose efforts to magazines, without success. It was frustrating, as it is for all people who are impelled, for whatever reason, to make such efforts and receive only rejection. These literary rejections played their part in forming Chessman’s attitude toward society, for he saw around him inferior works being published constantly, and he knew that he had a talent, although he was also aware of his shortcomings as a writer. But no one took any interest in his work, partly because the people with whom he associated were, with one or two exceptions, hoodlums, dropouts, and/or hellraisers. Chessman, himself a high-school dropout, had no monopoly on the loneliness of the rejected writer. But some others, perhaps, had fewer frustrations in other spheres of their lives; thus, literary rejections loomed large—and out of proportion—for Chessman from his late teen years.

It was not only the need to express himself that drove Chessman to writing; it was also a fierce need, even a demand, for recognition: one of the driving forces in his life, as he put it in this memoir, was to be “a factor.” He knew, deep within his soul, his own worth, his own values, and he fought desperately—from birth, it would appear—to find someone, somewhere, who would recognize that worth.

With the May 1954 publication of Cell 2455, Death Row, and its subsequent critical and commercial success, Chessman found, after six years of life inside his concrete-and-steel cubicle, the recognition that he had always sought. He had followed a strange and twisting path. At last someone knew, someone cared—and there were thousands of someones to whom he had expressed himself. His first royalty statement showed that, in little more than two months, 17,852 copies had sold, as had “condensation rights” to Pageant magazine, “reprint rights” to Argosy, “German serial rights,” and “Swedish book and serial rights.” By March 1955, Cell 2455, Death Row had earned him $23,425.57 in royalties, plus $6,750 from the sale of movie rights to Columbia. Royalties and subsidiary earnings (sales to foreign publishers) brought another $8,297.13.

The tragedy of the situation lay in what apparently had to take place before his worth could be brought into proper focus. The less tragic irony of the situation is that he discovered his own “worth” for himself, through the act of writing and publishing. Perhaps Elizabeth Hardwick, in a Partisan Review essay published at the time of Chessman’s execution, captured the full flavor of his achievement: “With extraordinary energy, Chessman made, on the very edge of extinction, one of those startling efforts of personal rehabilitation, salvation of the self.”

Getting Cell 2455, Death Row ready for publication was harried and hurried. We were up against the most final of deadlines imaginable: Chessman had a date with the executioner scheduled for May 14, 1954—near the scheduled date of the book’s publication. The officials at San Quentin State Prison and the Department of Corrections were amazingly cooperative throughout this process. They placed rooms at my disposal where I could work in close harmony with Caryl as we went over the edited manuscript. Arrangements were made for speedy handling of mail, beyond the normal routine. Every advantage was given to Caryl Chessman and to the publisher in handling the unusual situation, the publication of a book by a man scheduled to die in the gas chamber.

Chessman did not want some of the changes suggested for the manuscript, but he accepted them and approved them when he had time to consider them. He desperately wanted his book to be a success, and his sense of drama made him acutely aware of the effect that success might well have upon his eventual execution. It should not be forgotten that Chessman earnestly loathed the barbaric institution of capital punishment. He hoped that his books could display its futility to the world, for few have ever known its stupidities so personally, and still fewer have ever been so capable of enlightening an apathetic public to its absurdities. Just prior to his third scheduled death date, the aforementioned May 14, 1954, Chessman told Newsweek: “I’m all ready. I’m a million miles away. It’s difficult to explain but I feel . . . nebulous.”

Having been spared then, as he would ultimately be a total of nine times, he put his fantasy about his own death in the gas chamber down on paper in the prologue to Trial by Ordeal, published in 1957:

You die alone—but watched.

It’s a ritualistic death, ugly and meaningless.

They walk you into the green, eight-sided chamber and strap you down in one of its two straight-backed metal chairs. Then they leave, sealing the door behind them. The lethal gas is generated and swirls upward, hungrily seeking your lungs. You inhale the colorless, deadly fumes. The universe disintegrates soundlessly. Only for an awful moment do you float free. Tor a blackness that is thick and final swiftly engulfs you.

Then—what?

An improbable Heaven?

Another Hell?

Or simply oblivion?

Soon you’ll know. After long, brutal years of fighting for survival, your days are running out.

In a later chapter from the same work, he expanded on his fantasy:

You inhale the deadly fumes. You become giddy. You strain against the straps as the blackness closes in. You exhale, inhale again. Tour head aches. There’s a pain in your chest. But the ache, the pain is nothing. You’re hardly aware of it. You’re slipping into unconsciousness. You’re dying. Tour head jerks back. Only for an awful instant do you float free. The veil is drawn swiftly. Consciousness is forever gone. Tour brain has been denied oxygen. Tour body fights a losing, ten-minute battle against death.

You’ve stopped breathing. Tour heart has quit beating.

You’re dead.

Chessman did not write his first book with any thought that it might save his life, or even affect his situation. Indeed, it was not begun with any thought of actual publication in view. It was begun, continued, and completed at the instigation of prison and departmental officials. Their motives are, of course, best known to themselves—a chance to be seen as progressive, a chance to pacify an otherwise demanding and aggressive prisoner—but I am convinced that they were totally unprepared for the success of Cell 2455, Death Row. Warden Teets told me at one time, prior to publication, that he had begun to read the manuscript, but could not finish it. He thought it unpublishable.

A prison author was nothing new, even an author on Death Row. Indeed, San Quentin was the “home” of David Lamson, who, in 1936, published the famous We Who Are About to Die while serving time on Death Row. (Lamson was eventually acquitted of murdering his wife and freed.) Saint Paul and Cervantes, Bunyan and Defoe, Wilde, Gandhi and Bertrand Russell, Thomas More, Walter Raleigh, Nehru and Frangois Villon were all “prison” writers, and the simple fact of Caryl Chessman’s being in prison did not warrant the uproar which eventually surrounded him. His writings did.

The many reviews of Chessman’s first book were fascinating. It was especially interesting to note that one could almost determine the character of the reviewer by his reactions to Cell 2455, Death Row. Many reviewers had a field day at Chessman’s expense, and few of their reviews were objective. Even some of the most enthusiastic reviews were, it seemed to me, spurred by a need to express sympathy and make public the reviewer’s own “goodness.” Rarely did one sense a real awareness of the awesome spectacle presented by the combination of Chessman’s case and his writing skill. These attitudes on the part of reviewers were worldwide, not merely confined to the American scene.

Few reviewers realized the sheer skill of Chessman’s writing. With his narrative powers, Chessman could easily have written his book with a more careful eye to protecting his own reputation. He could have avoided distasteful episodes, watered down his own version of situations, and walked delicately among the names and dates and people of paramount importance. But he did not. Cell 2455, Death Row, which was eight hundred pages in manuscript form, was assuredly a catharsis. How drained he must have felt when he was done!

Some columnists, reviewers, and reporters stated rather flippantly that it was easy enough to write when you had nothing else to do all day—that Death Row was probably the perfect place for writing. Many prisoners do write, and perhaps the time available to them is a contributing factor. “Outside” authors have to worry about meals, making a living, and the trivia of everyday life. A prisoner, in that sense, has more freedom than a free man. Yet the absurdity of such an attitude is obvious, for having time available does not necessarily give a human being something to say and the skills with which to say it.

Besides, Chessman’s days were anything but empty. Having served as his own counsel since 1948, he spent many long hours researching and writing those many legal briefs. He also read lengthy court reports in order to clarify his own thinking, the better to approach his own desperate situation.

In addition, Caryl Chessman lived facing death, at a specific hour, a specific minute. All the gruesome details of his manner of dying, too, were in his mind. He was forced to recognize, quietly and daily, that he had only a certain number of days remaining. And despite the legal battles, the efforts to gain more stays of execution, he could never really know if he’d get another one until it was actually granted. Then, once more, he could tote up the hours and minutes that remained to him, and the devil’s merry-go-round kept turning.

It would seem, therefore, that only with a total disregard of the facts could one say that Caryl Chessman was in a perfect environment to write. To write meant taking time away from his battle for his very existence. How many authors would take such a gamble?

To fully appreciate the development of Chessman as a writer, it is imperative that one try to understand what his life was like before the publication of Cell 2455, Death Row. For five years, from the time of his sentencing until he contacted Critics Associated, he labored anonymously in his cell. During those years, he read constantly; wrote legal briefs, petitions for writs of prohibition and habeas corpus and rehearings; and fought desperately for his life. All the while, the urge to convey his message was strong, and he was steeling himself for a major effort. Years of watching other unfortunate human beings walk those last dreaded steps past his cell on their way to the gas chamber made Chessman’s need to convey to the public the truth of this barbaric punishment increasingly more urgent. And when his spirits flagged, as the toil seemed pointless and death seemed like blessed relief, Chessman consulted a magazine illustration that he kept on hand. It was an artist’s rendering of San Quentin’s lethal gas chamber, the so-called “Green Room,” located six floors below his cell. One glimpse at this drawing might have made others queasy, but it was like a shot of adrenalin for Chessman.

Caryl Chessman equipped himself for his career in the proper fashion. He played with words constantly, eyeing them, absorbing them, pondering them, putting them on paper and juggling them for every ounce of power and meaning he could draw from them. He had learned the hard way that the pen is, indeed, mightier than the sword. He discovered, painfully, how a sentence must be written and rewritten, cut and changed and altered and turned about in order to make it as effective as possible. He studied punctuation. He had long before learned to type with astonishing speed and almost without error. And at last, Caryl Chessman had a superb command of the tools of his trade.

It has always seemed significant to me that Caryl Chessman wrote the first of the three memoirs that comprise his autobiographical trilogy—Cell 2455, Death Row—in the third person, using a character named Whit as a stand-in for himself. He was literally standing on the outside looking in. In Caryl’s mind, using the third-person Whit was a literary device, and in a sense it certainly was. But it also seems to indicate that the forces at play during the early life of Caryl Chessman—parental relationships and so on—were so powerful, so vivid in his memories, subconscious and conscious, and so compelling, that it was mentally impossible for him to speak of them in the first person. In his mind, he was another person during those years. He was, so to speak, writing, psychologically, of a life with which he could not cope. I do not imply justification of this viewpoint, but merely emphasize the intensity of it for Chessman.

It was not until his first book was published successfully that any semblance of complete objectivity came to Caryl Chessman. The style, the words, the feelings behind his every bit of correspondence changed from the very day he first held a bound and finished copy of his book in his own hands. That day, that moment, Caryl Chessman became his own man. He was no longer “Whit.” He was “I.” Or, rather, “I” and “Whit” were one organic whole.

It is my unalterable conviction that, legalities aside, had it been possible for Caryl Chessman to become a free man at that moment, he would have become one of the most significant crime fighters in history. He would have been one of the greatest single assets to penology and criminology in our times. His one achievement, that one book—the one you now hold in your hands—had undone his past, had jerked him effectively to reality and to a sense of his own place in the world and to an honest desire to contribute to its betterment. I sincerely believe he would have then been as capable of adjusting to a confused and confusing world as any of the rest of us are. No writer ever achieves “the end,” the ultimate, the finished, final work which he feels is an unimprovable masterpiece. With success, Caryl Chessman first realized how much he had to learn, how far he had yet to go.

After the publication of Cell 2455, Death Row, Chessman’s hardened criminal carapace seems to have been molted. Now, without rancor or bitterness, he was capable of understanding the exaggerated and false statements about himself frequently printed in newspapers. He could smile knowingly when sums of money were attributed to his earnings which simply did not exist. Caryl Chessman finally knew tolerance.

For me, as Chessman’s friend and literary agent, it will always remain the great tragedy of his life that, from the moment of his triumph—which is what Cell 2455, Death Row really was, a literary triumph over unimaginable odds—forces began to work to undermine and minimize that accomplishment. Indeed, those forces tried to make it physically impossible for any such success to be repeated. Every possible effort, from then on, was made to stop Chessman from being published, and even from writing. He was forced to resort to legal loopholes, and eventually to subterfuge, even to write, much less publish. The very authorities who had formerly urged his rehabilitation upon him now calmly and deliberately set about undermining its success. Those who held sway over Caryl Chessman’s existence forced him to resort to underhanded means and devious paths in order to sustain any semblance of his success, sincerity, and sanity.

Can anyone comprehend the inner turmoil that must have tormented Chessman when, having achieved so much and having received acclaim from many quarters for his efforts, he was legally barred from continuing? What went on in his mind and heart when those who had encouraged him earlier now attempted to stamp out forever his chance for acceptance, his right to expression and true rehabilitation? Such attempts might have broken others, might have been the last straw, the penal equivalent of a lobotomy or a premature death penalty. Rather than buckling, however, Chessman went “underground”—writing in secret, writing in code, even during one stretch in an isolation cell, writing on toilet paper, and smuggling his efforts out of the prison to an eagerly waiting outside world.

Eventually, the law upheld Caryl Chessman’s belief that he had the constitutional right to put the creations of his mind on paper and sell them if possible.

Chessman completed the manuscript of his second book, Trial by Ordeal, early in 1955, shortly after another close brush with death in San Quentin’s apple-green gas chamber. He then attempted to convey his second book’s property rights to attorney Rosalie Asher by written assignment and to give Miss Asher physical possession of the manuscript. Acting on the orders of his superior and on the advice of the California attorney general, Edmund “Pat” Brown, Warden Harley O. Teets stepped in. Over Miss Asher’s strenuous protests, Teets confiscated both the written assignment document and the manuscript.

While it was hard to gauge at the time what was going through Chessman’s head over these new restrictions, a singular piece of writing came to light following his execution. Unpublished, never even offered for publication, there existed a series of “interviews” with the convict author. I now have that series of articles in my possession. In them, every aspect of the complex Chessman case is discussed.

The intriguing part of these “interviews” is that Caryl Chessman wrote them himself, but even left a blank space for the name of the “interviewer” to be inserted. In regard to this situation, Chessman wrote:

To famed personal injury lawyer Melvin Belli, himself an author, this confiscation and the writing ban smacked of“thought control.” “Why, even in the Dark Ages, prisoners were allowed to have their works published,” Belli acidly commented. He offered his services to Chessman and Miss Asher. A court fight was launched to pry the manuscript loose from the prison officials. Meanwhile, Clarence Linn, Chief Assistant to the California Attorney General, and a man who has grown older fighting Chessman’s numerous appeals, told the press: “The prison people can take it [the manuscript] out in the back yard and burn it if they choose to do so,” with his inflection suggesting he would approve the idea.

“I made up my mind this would never happen,” Chessman said. “And the claim that the manuscript was really prison property was nonsense.”

The litigation aimed at securing release of the manuscript got temporarily bogged down on a jurisdictional point, and Chessman lost another round in his hectic court struggle for survival. A new execution date was set for July 11.

Then, on May 26, Chessman’s New York publishers, Prentice-Hall Inc., announced they would publish Trial by Ordeal on July 7—just four days before Chessman was scheduled to die.

It appeared Chessman had outwitted the state again. While there was some speculation initially that the manuscript to be published might not be authentic, such speculation was firmly squelched in short order.

Chessman’s literary agent, Joseph Longstreth of New Tork, said, “I have an exact copy of the original Chessman manuscript of Trial by Ordeal held by Warden Teets, and if Teets desires I would be most happy to fly out there and compare it with him, page for page, line for line, word for word.” Teets declined to make this comparison. That ended that. There was no doubt that the manuscript was the real thing.

But how had Chessman managed the “impossible” feat of smuggling the bulky manuscript out of the maximum security confines of San Quentin’s death row? During an exclusive interview, Chessman cleared up the mystery. “When I read that Clarence Linn had said the manuscript could be destroyed, I had to talk with another convict. He may or may not have been a condemned man.” [Chessman spoke in hypothetical terms and refused to name names.] “I must protect the man at all costs.” He did say that there were “five or six” persons involved in the complex scheme and that it was “strictly a convict deal.”

Chessman said he turned a carbon copy of the manuscript over to convict No. 1 in three separate installments and “it might have gone out [of Death Row] in some trash.” Convict No.l turned it over to convict No.2 who was told to hide it within the prison while Chessman waged a legal battle to get the original manuscript released.

For many weeks, Chessman said, the manuscript was hidden in one or another of the prison shops, and it changed hands frequently. A crisis finally arose, he said, when the inmate then guarding it was suddenly changed from one job to another. “He apparently decided the best thing to do was to get the manuscript entirely out of the prison,” Chessman said.

Asked how was this accomplished, Chessman replied: “A minimum security prisoner could have left it lying around and bypre-arrangement an outsider could have picked it up and mailed it.”

Chessman added, “Every day it becomes more apparent how apt a title I picked. I had to fight to stay alive to complete the book. Then I had to find a way that everyone said didn’t exist to protect the book and get the manuscript of it to my publisher and agent. Now I am obliged to combat the efforts of certain self-righteous citizens who are determined to destroy the book’s potential. They aren’t going to succeed.”

It was a sign of his rehabilitation that he did not turn his rancor against those who imposed restrictions upon him; he honestly understood their position. Did they understand his? Did they comprehend, in human terms, what it meant to Chessman, alone in his cell, lights out, to know that having finally achieved something worthwhile in his life, having at last, tortuously, given meaning to an otherwise meaningless existence, he was to be denied the right to continue his efforts? Had the Chessman writings deserved the condemnations of the individuals involved, one might have understood; had the Chessman writings been vitriolic attacks on officials or the system of penology in California, or had they been replete with falsehoods and twistings of truth, one might have understood. As it happened, the reasons for wishing to silence Caryl Chessman were never made perfectly clear. Could they have been? The truth has not yet been told. But that these attempts to silence him were unlawful has been made clear.

Here, again from these unpublished, self-penned “interviews” with himself, Chessman wrote about the suppression of his second book, Trial by Ordeal:

Halfway through Trial by Ordeal, Chessman was jarred to learn that California Director of Corrections Richard A. McGee had banned all publication of all writings by a doomed man.

“I couldn’t believe it at first,” Chessman recalls.

But it was true.

The reason given by McGee: “Invariably books written by condemned men involve their own cases. Consciously or unconsciously they are designed to influence people about the man or the case.

“Under present law, however, cases involving the death penalty are never finally adjudicated until the man is executed. We therefore felt that there should be no attempt made to influence the public as long as the case is pending.”

Second, even if it were true, reporters can interview any doomed man they desire and quote him at whatever length they desire, wherever and whenever and however they desire. What is the difference whether the condemned man’s published words about his case are intentionally spoken to a reporter or written down by the man himself on a typewriter?

Third, what Mr. McGee really means when he says that “no attempt [should be] made to influence the public as long as the case is pending before the courts,” is that no attempt should be made by the doomed man, but that anyone else can say anything they want any time they want. Obviously Mr. McGee has neither the authority nor the ability to silence any citizen, lawyer, public official, groups, crank or crackpot who deserves to have something to say about the doomed man or his case, whether pro or con.

“Another result,” McGee has stated, referring to the ban, Ss that if a [condemned] makes money from a book, it permits him to employ legal talent to fight his case, which other prisoners can’t afford.”

This may be a noble sentiment in the abstract, Chessman replies, but it also is an ominous one in reality. What Mr. McGee actually is contending for among the doomed is an equality of poverty, helplessness and anonymity. In effect, he is conceding that the state can execute and execute quicker and easier if the condemned man is fund-less, friendless and helpless, an advantage which he seems to feel the state should have. Mr. McGee, in consequence, is also saying necessarily that he is willing to use the naked power of his office to keep the state’s doomed broke and silenced. Why?

Press reactions to Caryl Chessman, as a writer, were astonishing. In some instances they were frightening; in some instances sickening. I recall particularly four different members of the fourth estate who talked to me at great length about Chessman as a writer. Each decried his success, attributing it to sensationalist publishing, to the linking of promotion to impending executions. In actual fact, considerable restraint was exercised on the part of everyone concerned in the publication of Caryl Chessman’s works; it would have been simple enough to sensationalize the publications. As his literary agent, I turned down many exploitative offers to milk my client’s notoriety. The works of Caryl Chessman did not need artificial stimulation in that fashion; the press itself provided more than enough sensationalism.

In the instance of these four particular reporters, each one derided the “literary merit” of Caryl Chessman’s books. In two instances, however, I discovered that the people voicing such condemnation had not even read Chessman’s books; and in the other two cases under consideration, both had written unpublished books themselves, without having received so much as a sympathetic letter of rejection from a publisher!

It has always been sad, to me, to receive letters from hopeful or would-be writers saying, “Guess you have to kill somebody, be a reformed alcoholic or drug addict, or get on Death Row before you can write a book anybody will publish!” The lengths human beings will go to to deceive themselves! And this sour attitude, too, helped cloud appreciation of Chessman’s quality as a writer.

It would be impossible, of course, to divorce the Chessman case and the Chessman “situation”—i.e., his Death Row life and the sideshow aspects of his life-and-death struggle as painted in the press—from his literary efforts. But can we divorce any writer, of any genre, from his environment? Shakespeare? Cummings? Faulkner? Dickens? Rilke? It is the essence of futility to speculate on whether or not a given artist would perform—or would have performed—differently under different circumstances. The two can never be separated, and attempting to do so serves little purpose.

The unpublished works of Caryl Chessman were not available for study until after his execution. In most instances, they reveal a struggling writer, an author of undisciplined talent who has not yet found what he wants to write about. And it is no criticism to say that Chessman wanted and needed to write about himself. That he did, and was encouraged to do so, is a fact for which the psychological and penological worlds, society itself, can be eternally grateful—and for which the future will give credit to those to whom credit is due. That concerted efforts were made to suppress Chessman, once he proved he had abilities, will always remain a subject of discussion and suspicion. The real motive can only be guessed.

Caryl Chessman wrote several short stories, some of which remain unfinished. Some are attempts at humor. Most are forced and contrived, for he was writing from the head, not the heart. Some of the stories tried to portray emotional experiences, to convey the meaning of death, of life, of frustration, depression, exaltation, humiliation. Again they do not meet with complete success. They are forced and artificial. But when he wrote about justice, his words burned with fierceness and truth. And when writing of his companions on Death Row, of their frustrations and foibles and peccadilloes, his words touched—even wrenched—the heart.

I have often been asked: “What effect do you believe Chessman’s writings had upon his case?” I am not being evasive when I respond that only history can presume to judge. We can, however, hazard several guesses.

It is unquestionably true that, had it not been for the Chessman books, there would not have been the national and international outcry over the agonizing stays of execution, the seemingly interminable legal battles, and the eventual execution of Caryl Chessman. It was his own writing which turned his case into a cause celebre. Perhaps we should say that it was writing which brought the confusions of the case to the awareness of the public. People took sides because his writings aroused them, one way or another. The public cared because they imagined they knew a great deal about the case. The press, in turn, played the “condemned author” game to the hilt, without regard, in many instances, for the facts involved. People still sometimes say to me: “Well, after all, he was a killer!” The sad truth of this shocking affair of twelve years is that he was not a killer. No life was ever taken—except Chessman’s! And it remains true that, with the publication of his second and third books, and his fourth, almost coinciding with his execution, the press took less and less of a searching look at the writings and more and more of a sensationalist view of the spectacle.

As the public sensation caused by Chessman’s first book subsided, his fate became more important than what he really said as a writer. It could be argued that Chessman failed as a writer, given the relative weakness of the second and third books and their inability to sustain the excitement of the first. But such a view ignores the fact that the three books—Cell 2455, Death Row; Trial by Ordeal; and The Face of Justice—were conceived as a trilogy and written as such. However, each stands alone, for the writer Chessman did not fall into the trap of assuming that every reader had read his previous books. But inevitably, much of the most “glamorous” portion of the searing story had been told, and books two and three demanded more of the reader than had book number one. Neither can one ignore the strained circumstances under which the second and third books were written and published. In actual fact, in the subsequent books, the writing itself improved. Chessman achieved restraint, acquired more finesse and polish, though he had still not shed himself of fiery tendencies which often overstepped the boundaries of need. He had learned much from those reviewers who honestly criticized his writing.

Yet it is important to remember, always, Caryl Chessman’s world was a singularly lonely one—lonely for one who had become a thinking, sensitive man. One has but to read the descriptions of his fellow Death Row inhabitants to know the caliber of this individual who was generally available for discussions and exchanges of ideas. How frustrating it must have been for a man of Caryl Chessman’s capabilities not to have stimulating minds to combat, with which to exchange thoughts and explore searching problems. Even the prison authorities, considerate as some of them were at times, were no match for the keen penetrations of Chessman, the observations of which he was capable, even the wit he often displayed.

Chessman’s own reactions to the press are often expressed in his books. He knew the tendency to slant, the evident willingness to publish half-truths and mere semblances of fact, and the constant pressure under which reporters were forced to produce their stories. Not many human beings ever have the occasion to know firsthand, as did Chessman, how fact can be distorted in order to make a better story. The almost constant refusal of most of the press to be explicit, to state simple truths, was a source of never-ending exasperation for Chessman. And yet, ironically, few figures of notoriety—or infamy— have been as open and forthcoming to the press as Chessman was, even to those who had taken him to task in print.

Again, it was of significance that the press chose to emphasize the smuggling of his manuscript out of the prison, rather than its content. Almost nowhere, even in literary circles and publications supposedly devoted to the well-being of author, publisher, bookseller, did one read editorials or even articles or little news briefs to the effect that something was wrong with the suppression. And the protests from abroad, if reported at all, only brought snide comments that foreigners should mind their own business. Where, in print, was the law prohibiting Chessman from writing seriously challenged?

Few men autobiographically have been able to bare their souls as dramatically as did Caryl Chessman in Cell 2455, Death Row. With swift strokes, he creates a dramatic narrative that stuns the reader, and it is a rare reader who does not have the sense of “There, but for the grace of God, go I”! But it is equally true that, once many have finished reading the book, they begin to rebel. I have known several people who could not finish the book. They said: “It’s evil, and the man is evil.” Better they should have looked into their own soul with equal tenacity and fearlessness to dissect their own weaknesses.

Of singular significance is the fact that Caryl Chessman never asked, and certainly never begged, for sympathy, or even for understanding. There are those who condemn him because, at the last minute, he refused to compromise his soul by hypocritical “acceptances.” Such persons are, in reality, seeking to assuage their own sense of guilt and fear. Caryl Chessman wrote as he felt and believed, the devil take the hindmost. He placed responsibility upon the reader, where it rightly belonged—on the public. Indeed, the very ending of Cell 2455, Death Row crystallizes the essence of Chessman’s dilemma:

Night soon will be here,

For me, it may be a night that will never end.

Does that matter?

Do your Chessmans matter?

The decision is yours.

It is obvious that one cannot divorce Caryl Chessman, the condemned convict, from Caryl Chessman, the published writer.

And it is equally obvious that Caryl Chessman, the writer, will have his day, long after those who executed the condemned convict have passed into oblivion.

Editor’s Note: This essay, written around 1970 by Joseph E. Longstreth—and published posthumously here for the first time—has been updated and completed by Alan Bisbort, author of “When You Read This They Will Have Killed Me”: The Life and Redemption of Caryl Chessman, Whose Execution Shook America (Carroll & Graf, 2006).