Paul – lead

vocals, bass, piano

John – harmony vocals

George – harmony vocals

Ringo – drums

George Martin – piano

It says something about the quality of Revolver that ‘Good Day Sunshine’ is probably the weakest McCartney track on the album. It is the kind of song which, at any other time, could easily have gone awry – in earlier years developed into a simple pot-boiler and in later years become self-conscious and cloying. Yet Paul was so evidently on a songwriting high in 1966, that you feel whatever he wrote would have a platinum quality hallmark. This delightful, easy-going number sounds as effortless as one of his throwaways, but the song’s myriad of deft musical touches and the exquisite production by all five performers add up to much more.

The track is reminiscent of ‘Not A Second Time’ in being an upbeat, piano-dominated song. Although Paul had used the piano to write songs – more frequently than John – until now he would have translated them into guitar-based Beatle songs. As his proficiency on the piano developed, so the piano became more evident in his songs, leading to the Fats Domino style of ‘Lady Madonna’, the elegant motifs of ‘Martha My Dear’ and ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’, and ultimately the solemn and reflective ‘Let It Be’ and ‘The Long And Winding Road’. The instrumentation on ‘Good Day Sunshine’, in common with most of Paul’s Revolver tracks, shows him seemingly trying to get away with as little assistance from the other Beatles as possible. It is particularly notable that John does not appear on ‘For No One’, contributes backing vocals only on ‘Eleanor Rigby’, ‘Here, There And Everywhere’ and ‘Good Day Sunshine’, and makes a minimal contribution to ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’.

On this track, both John and George supply harmony vocals only, with Paul’s piano and bass being helped out in the middle by George Martin, whose rolling, barrelhouse style piano underlines the song’s old-fashioned setting and adds an element of nostalgia to the piece. The hotch-potch of styles and influences works well – there is no logic behind the addition of the saloon-bar interlude, but, like the Elizabethan solo in ‘In My Life’, George Martin’s contribution is somehow most apt.

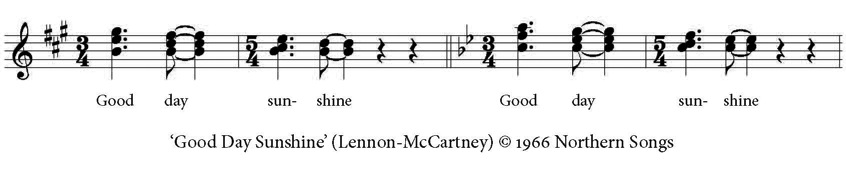

The strength of the song, however, lies in Paul’s skilful use of harmonic and rhythmic changes, the unusual additions executed with confidence and style. The song’s dark, ominous entrance belies its message. We wait patiently for whatever it is to arrive, for four long bars of muted piano/bass crotchets. The syncopation of the refrain, produced from six uneven bars that land four-square after Ringo’s introductory triplets, is suddenly fresh and vibrant. The contrast with the introduction is the effect of the sun bursting through after travelling along a long dark tunnel. The two bars of one-and-a-half beats followed by the two-beat rest anticipates John’s erratic rhythms on ‘Good Morning Good Morning’, particularly the insistent final 5/4 bar of the verse.

But the uneven six-bar/eight-bar structure is as nothing beside the harmonic manoeuvres Paul carries out. The song remarkably and deftly slips between keys, as if having become giddy in the heat of the sun. The pounding four bars of piano and bass in E lead to the joyous refrain in B with switches to F# (V). But immediately, with the onset of the verse, there is a surprising tumble into A by way of the original E major chord that is common between them. The refrain’s F# reappears briefly in the A–F#7–B7–E7–A (I–VI7–II–V7–I in A) turn. After the warmth of the verse, the refrain again breaks out back in the rapturous key of B major, but halfway through the second verse, back in A, the piano chips in for four bars, in D major. The piano’s reverie ends with a jolt as the syncopation of the refrain returns. After the final verse, the refrain repeats twice and then the song modulates up a semitone, the key actually shifting to F major. The syncopation is reinforced as voices echo off one another, spanning the stereo spectrum and spinning into the distance.

The track seems to have been recorded fairly quickly, being one of the last to be taped for the album. On 8 June, in a twelve-hour session ending at 2.30 am, the group recorded the basic track of piano, bass and drums and then overdubbed the lead and harmony vocals. The following day, in under six hours, Ringo taped another drum track (evident in the left channel of the final recording), and George Martin taped his middle piano solo. As well as various handclaps from all four Beatles, Paul, John and George taped the final “Good day sunshine” harmonies that were to be tacked onto the end of the song. About ten seconds before the end of the track, the basic piano/bass/drum combination suddenly disappears from the right-hand channel to allow these harmony vocals to be dropped in.

Paul remembered that the song was “influenced by the Lovin’ Spoonful”, whose song ‘Daydream’ was riding high in the charts at the time. Interestingly, the Lovin’ Spoonful’s follow-up, ‘Summer In The City’, seemed to shun the spate of sunny summertime records – led by the Kinks’ ‘Sunny Afternoon’ – that appeared in mid-1966, and took a rather darker look at the subject.

Originally called ‘A Good Day’s Sunshine’, Paul’s song is pointedly optimistic, equating the glory of a sunny summer’s day with the ecstasy of requited love. The heat of his love leaves him breathless, as the heat of the sun scorches the earth. There is nothing to do but lie in the shade, staring at the sky through the leaves of a tree, and wallow in happiness.

The unambiguous coupling of sunshine with goodness and delight, while simplistic, is undeniably touching. Paul’s “need to laugh” is evidenced in the last verse when, after he sings an upbeat “she feels good”, John quietly mutters a descending, less cerebral “she feels good”. Paul seems to recognise the more physical double meaning of the line that John’s response brings out, and his smile is audible.