Together, the pair trekked along a deep valley between two giant mountains. Bear told Olly that being on a glacier meant that beneath them wasn’t solid ground but solid ice, many hundreds of metres thick.

“When it comes to the wild mountains you have to be prepared or you might not survive.” He looked right at Olly. “Out here we are going to fight smart, okay?”

Olly nodded cautiously.

Bear tied one end of his black climbing rope around Olly’s waist, and tied the other end to himself, leaving a long stretch of loose rope between them.

“The danger on a glacier is always what you can’t see beneath you.” Bear tied the final knots. “Together we are stronger. If one of us falls through a hole in the snow into a crevasse beneath, then the other one can stop that fall being fatal.” He coiled the rest of the rope around his shoulder, ready for use if needed.

“What’s a crevasse?” Olly asked with a sense of dread.

“Crevasses are tears in the ice that get formed as the glacier moves around. They can be hundreds of metres deep. Dark scars carved into the glacier, constantly shifting, often hidden, and one of the biggest dangers in the high peaks.” He paused. “I was almost killed in a crevasse many years ago and it taught me a healthy respect for the mountains. That’s why we rope up. Out here you will only get it wrong once.”

Olly looked down at the knot tied to him and pulled it extra tight.

* * *

It was hard going when they set off, and Olly’s legs started to get extra tired, extra quick. The snow was about ten centimetres deep, so he had to lift his foot right out of the snow with every step before he could move it forward and put it down again.

Even though there was a storm coming, they only made their way slowly along the valley, plod, plod, plod. Bear also had a long, carbon-fibre pole and he prodded the ground in front of them with every step.

Olly looked back over his shoulder to check the storm’s progress, and promptly fell flat on his face as his boots hit a buried rock. His knees stung from scraping against it. “Careful, champ.” Bear helped Olly up. “Try to keep looking ahead. We always look forward – in body and mind. It’s also why I use the pole. You never know when there’s something beneath the snow. A hole, crevasse or rock could all break your leg. Try to follow where I walk.”

“Shouldn’t we be hurrying?” Olly asked.

“No. The air’s so thin up here that you’d just collapse because your lungs wouldn’t be getting enough oxygen. And hurrying makes you sweat, then the sweat turns to ice on your skin, and you catch hypothermia. Two more ways to die! So we don’t hurry. We’ll do better if we just keep going, slow and steady.”

“What’s hypothermia?” Olly asked as they pressed on.

“Well, your body always tries to keep itself at the same temperature, thirty-seven degrees. It’s called your core temperature. Hypothermia is when your core drops below thirty-five degrees, and your body has to start pulling in blood from your arms and legs to try to keep your brain and core organs warm. It means your hands and feet stop working properly. And if you still don’t get warm, and your brain starts to cool down, you then lose the ability to make good decisions, until eventually… well, you get the idea.”

Olly thought about that while they walked in silence for a while. Every step was still an effort, though Bear made it look so easy. He tried to copy the way Bear walked, constantly checking out the ground ahead. He walked with a kind of rhythm. Step and lift foot, step and lift foot, step and lift foot …

Because Olly was concentrating so hard it took him a moment to notice Bear was leading them over to the left-hand side of the valley, instead of heading straight down. He snuck another frustrated look back at the storm. It felt like this guy was determined to make them go slow.

“Why are we going this way?” Olly asked. ‘Isn’t it quicker to go straight?”

“The quickest route isn’t always the straightest,” Bear told him. He pointed saw that, near the top, the sides didn’t slope. They went straight up – and then, in places, they started to slope outwards.

“Can you feel the wind?” he asked Olly. “It’s blowing against the right-hand side. That means it carves out the snow on that side of the valley, so it overhangs. When the overhang gets too heavy, it falls. Then you get a thousand tons of snow dropping on your head from five hundred metres, and, well, then it gets messy.”

“Let me guess,” Olly said, “another way to die?”

“You’re getting the hang of it!”

Soon they left the overhang behind them, but the valley was getting narrower. Eventually the steep walls were only about thirty metres apart, and the ground in between was smooth and flat.

“This is good,” Bear told Olly. “We’re off the glacier and back on solid ground. The forest will be down ahead of us now.”

Bear carefully untied the rope from Olly and re-coiled it, and then the pair kept moving.

Just when Olly felt they were making good progress down and away from the mountains, Bear suddenly stopped and held up his hand.

“See that?” he asked.

Olly peered ahead and tried to see something different.

“Snow?” he said.

“Yes, but it’s completely flat. All the snow we’ve walked on so far has had bumps in it because of the ground underneath. Whenever I see something different I get suspicious. I want to know what’s changed. Wait here.”

Bear walked forward slowly, prodding the snow with his pole as he went. Olly stood where he was. He felt the cold seep into his boots and tramped on the spot to warm his feet up. He just wanted to be moving again. Bear knelt down and brushed the snow away with his glove. Then he beckoned to Olly. “Come and look, but carefully. Only step in my footprints.”

Olly walked forward curiously, carefully putting his feet exactly where Bear’s had been. Where Bear had scraped away the snow, Olly saw smooth, grey ice.

“There’s a frozen lake under us,” Bear said. He waved a hand at the flat snow in front of them. “That’s why it’s so smooth.”

Olly glared at the ground. “Is it safe?’ he asked nervously Suddenly he was afraid to move in case it cracked open beneath him.

“Grey ice like this is usually old and thick,” Bear said. “If it was dark, that would mean it was thinner. If it’s at least five centimetres then it’s safe.” He stood up and rapped on the ice sharply with his pole, three times. “So this should take our weight. Okay. Time to rope up again.”

Bear reattached the rope to Olly, this time with a little more distance between them. Then he studied the smooth snow in front of them carefully.

“It’s never ideal to have to walk on any ice, but there’s no other way around. We’ll stick close to the side, where the ice is stronger. We’ll go steady – just walk exactly where I walk.”

And so they began to make their way carefully along as the rocky mountain faces towered overhead. Every few steps, Bear jammed his pole through the snow to feel the ice underneath. Then he put his foot exactly where the pole had been. He took short steps so that Olly could put his feet in Bear’s footprints.

Now that Olly knew he was walking on thin ice, he thought he could feel it. It trembled and creaked and groaned, like it might be about to snap. Or was that just his imagination? He couldn’t tell. He just knew he would be very glad to get off it.

Up ahead, about twenty metres away, the snowy ground started to go up. That must be the shore of the lake, Olly realised. Once they were there, they would be safe. Olly fixed his eyes on it, watching it get closer, step by step. His legs still trembled at the thought of the fragile ice underneath.

Soon the ground was five metres away, the other side of a few rocks sticking up through the ice. Olly grinned in relief. They were going to make it!

But once again, Bear wasn’t heading straight for the shore. He was walking around in a wide curve. The shore was just metres away. How long was he going to keep them out here?

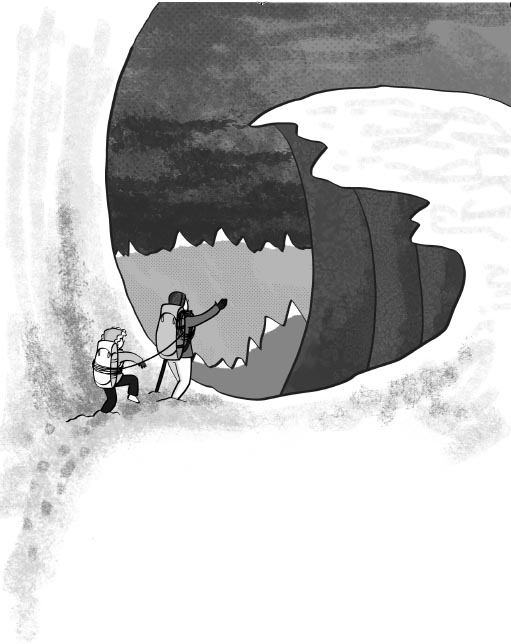

Bear had said stick to the edges, and they were at the edge. Olly decided to make a break for it. He took one, two, three steps. There was a loud crack.

“Olly!” Bear shouted in alarm.

Then the ice gave way.

Olly screamed as he plunged into the freezing, dark water.