Our feast is, literally, a feast of bold colors and generous gestures. It is driven by an unapologetic desire to celebrate food and its virtues, to display abundance in the same way that a market stallholder does: show everything you’ve got and shout its praise wholeheartedly.

We got started in July 2002, not really sure what was ahead of us, when we opened Ottolenghi—food shop, patisserie, deli, restaurant, bakery. A place with no single description but at the same time a crystal-clear reflection of our obsessive relationship with food. In a small shop in Notting Hill, we began to cook and bake.

We did it while the white paint on the walls was still drying. Together with a small group of friends, and alongside some newly acquired staff (quickly turned friends), we began our experiment with food.

Our partner and designer, Alex Meitlis, supplied us with a blank canvas: “A white space with white shiny surfaces is what’s going to make your concoctions stand out,” he said. We argued a little but were soon persuaded. The white background turned out to be the perfect setting for our party. And we did not intend to be shy about it.

We wanted to start this book with the quip, “If you don’t like lemon or garlic … skip to the last page.” This might not be the funniest of jokes, but, considering lemon and garlic’s prevalence in our recipes, it is as good a place as any to start looking for a portrait of our food. Regional descriptions just don’t seem to work; there are too many influences and our food histories are long and diverse. True, we both come from a very particular part of the world—Israel/Palestine—with a unique culinary tradition. We adore the foods of our childhood: oranges from Jericho, used only to make the sweetest fresh juice; crunchy little cucumbers, full of the soil’s flavors; heavy pomegranates tumbling from trees that can no longer support their weight; figs, walnuts, wild herbs.… The list is endless.

We both ate a lot of street food—literally, what the name suggests. Vendors selling their produce on pavements were not restricted to “farmers’ markets.” There was nothing embarrassing or uncouth about eating on the way to somewhere. Sami remembers frequently sitting bored in front of his dinner plate, having downed a few grilled ears of corn and a couple of busbusa (coconut and semolina) cakes bought at street stalls while out with friends.

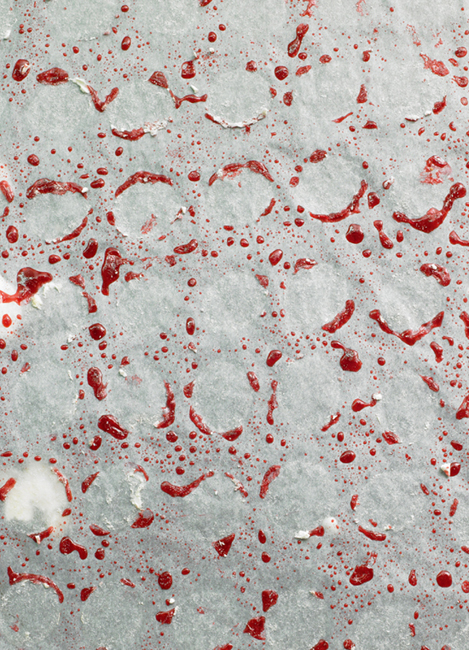

However, what makes lemon and garlic such a great metaphor for our cooking is the boldness, the zest, the strong, sometimes controversial flavors of our childhood. The flavors and colors that shout at you, that grip you, that make everything else taste bland, pale, ordinary, and insipid. Cakes drenched with rose-water-scented sugar syrup; piles of raw green almonds on ice in the market; punchy tea in a small glass with handfuls of mint and sugar; the intense smell of charred mutton cooked on an open fire; a little shop selling twenty types of crumbly sheep and goat’s milk cheeses, kept fresh in water; apricot season, when there is enough of the fruit lying around each tree to gorge yourself, the jam pot, and the neighborhood birds.

These are the sources of our impulse. It is this profusion of overwhelming sensations that inspires our desire to stun with our food, to make you say “wow!” even if you’re not the expressive type. The colors, the textures, and finally the flavors that are unapologetically striking.

Like the market vendor, we make the best of what we have and don’t interfere with it too much. We keep food as natural as possible, deliberately avoiding complicated cooking methods. Take our broccoli, the king of the Ottolenghi jungle. It is mightily popular, but it can’t get any simpler. If you don’t know it, you must try it (recipe); if you do, you will no doubt try it anyway.

Unfussiness and simplicity in food preparation are, for us, the only way to maintain the freshness of a dish. Each individual ingredient has a clear voice, plain characteristics that are lucid and powerful—images, tastes, and aromas you remember and yearn for.

This is where we differ deeply from both complicated haute cuisine and industrial food: the fact that you can clearly taste and sense cumin or basil in our salad, that there is no room for guessing. Etti Mordo, an ex-colleague and a chef of passion, always used to say that she hated dishes that you just knew had been touched a lot in the preparation.

We love real food, unadulterated and unadorned. A chocolate cake should, first and foremost, taste of chocolate. It doesn’t have to involve praline, raspberries, layers of sponge, sticky liqueur, and hours in the freezer. Give us a clean chocolate flavor, a muddy, fudgy texture, and a plain appearance. Good solid food is a source of ageless pleasure and fun.

This ability to have fun, to really enjoy food, to engage with it lightheartedly and wholeheartedly is the key for us. After centuries of being told how bad their cuisine was, the British have started taking pride in their food in recent years, joining the European set of confident, passionate, and knowledgeable devourers. Then, suddenly, they were made to feel guilty for having fun. All of a sudden it is all about diets, health, provenance, morals, and food miles. Forget the food itself.

How boring, and what a mistake! This shift of focus sets us back two decades, to a time when food in the United Kingdom was just foodstuff, when it was practical instead of sensual, and so we risk once more losing our genuine pleasure in food. People will not care much about the origins of their food and how it’s been grown and produced unless they first love it and are immersed in it. It is, yet again, about having fun. Don’t get us wrong: supporting small farmers around the globe, treating animals humanely, making sure we don’t pollute our bodies and our environment, resisting the total industrialization of agriculture—these are all precious causes. Our wealth and the cheapness of our food give us an added responsibility to eat sensibly and ethically.

But it isn’t a black-and-white choice of good versus evil when it comes to food; you can be well informed and make wise decisions about what to buy and where without turning into a fanatic. Most people’s lifestyles don’t allow them to grow their own vegetables or source all their meat from a local free-range farm. They must compromise without feeling guilty. So they go shopping in a supermarket during the week and visit a farmers’ market on the weekend. They might choose an organic egg alongside a frozen vegetable.

This carefree but realistic approach to cooking and eating is what we try to convey with our food: the idea that cooking can be enjoyable, simple, and fulfilling, yet look and taste amazing; that it mustn’t be a chore or a bore, with lots of complicated ingredients to source and painstakingly prepare, but can be accessible, straightforward, and frank. For us, cooking and eating are not hazy, far-off ideals but part of real life, and should be left there.

One thing immediately evident at Ottolenghi is that you often see the chefs bringing up trays and plates heavily piled with their creations. It is a source of pride for them and for us to see a customer smile, look closely, and then gasp and give them a huge compliment. So many chefs miss out on this kind of immediate response from the diner—the reaction that leads to a leisurely chat about food.

This communication is essential to our efforts to knock down the dividing walls that characterize so many food experiences today. When was the last time you went shopping for food and actually talked to the person who made it? In a restaurant? In a supermarket? It doesn’t happen. And, since cooking at home has become less common, we are deprived of this dialogue. So at Ottolenghi we are simulating a domestic food conversation in a public, urban surrounding.

When you sit down to eat, it is as close as it gets to a domestic experience. The communal dining reinforces a cozy, sharing family atmosphere. What you get is a taste of entering your mother’s or grandmother’s mythical kitchen, whether real or fictitious. Chefs and waiters participate, with the customer, in an intimate moment revolving around food—like a big table in the center of a busy kitchen.

But it’s not only the way you sit; it is also what surrounds you. In Ottolenghi you will always find fresh produce, the ingredients that have gone into your food, stored somewhere where you can see them. The shelves are stacked high with fruit and vegetables from the market. A half-empty box of rutabagas might sit next to a mother with a baby in a buggy, until one of us comes upstairs and takes the vegetable down to the kitchen to cook.

Once the food is on the counter, we try to limit the distance between it and the diner. We keep refrigeration to a minimum. Of course, chilling what we eat is sometimes necessary, but chilled food isn’t something we’d naturally want to eat (barring ice cream and a few other exceptions). Most dishes come into their own only at room temperature or warm. It is a chemical fact. This is especially true with cakes and pastries. Their textures and flavors are destroyed beyond salvation through refrigeration.

It is a chilling experience to eat a cold sandwich, yet so many of us routinely do and are almost oblivious to it because it is considered a necessary evil. With most things prepared fresh, really fresh, there is no need to chill. Every customer who comes to Ottolenghi and doesn’t hear the soul-destroying hum of a brigade of stainless-steel fridges is another convert to minimal refrigeration. None of us feels much confidence in a refrigerated deli counter full of mayonnaise-based salads that might have been sitting there (in the temperature “safe zone”) for days. Conversely, it is reassuring to know that if there isn’t a fridge, the salads must be fresh.

Not many traditional hierarchies or clear-cut divisions exist in the Ottolenghi experience. You find sweet alongside savory, hot with cold; a tray of freshly baked breads might sit next to a scrumptious array of salads, a bowl of giant meringues, or a crate of tomatoes from the market. It is an air of generosity, mild chaos, and lots of culinary activity that greets customers as they come in: food being presented, replaced, sold; dishes changed, trays wiped clean, the counter rearranged; lots of other people chattering and queuing.

It is this relaxed atmosphere that we strive to maintain. Casual chats with customers allow us to cater to our clients’ needs. We listen and know what they like. They bring their empty dishes in for us to make them “the best lasagna ever” (and if it’s not, we will definitely hear about it). This is what encapsulates the spirit of Ottolenghi: a unique combination of quality and familiarity.

We guess that this is what drew in our first customers. So many of them have become regulars over the years, meaning not only that they come to Ottolenghi frequently but also that we recognize them, know their names and something about their lives. And vice versa. They have a favorite sales assistant who always gets their coffee just right (probably an Italian or an Aussie), their pastry of choice (Lou’s rhubarb tart), their preferred seat at the table. Our close relationship with our customers extends to all of them, whether it’s the bustling city stars forever on their way somewhere; the early riser eagerly tapping his watch at five-to-opening; the chilled and chatty sales assistant from next door; the eternal party organizer with a last-minute rushed order; or a mother on the lookout for something healthy to feed her and the children.

The Ottolenghi cookbook came into existence through popular demand. So many customers asked for it that we simply had to do it. And we enjoyed every minute of it. We also loved devising recipes for our cooking classes at Leiths School of Food and Wine, some of which appear in this book. The idea of sharing our recipes with fans, as well as with a new audience, is hugely appealing. Revealing our “secrets” is another way of interacting, of knocking down barriers, of communicating about food.

The recipes we chose for the book are a nonrepresentative collection of old favorites, current hits, and a few specials. Some of them have appeared in different guises in “The New Vegetarian” column in the Guardian’s Weekend magazine. They all represent different aspects of Ottolenghi’s food—bread, the famous salads, hot dishes, patisserie, cakes, cold meat, and fish—and they are all typical Ottolenghi: vibrant, bold, and honest.

We have decided not to include dishes incorporating long processes that have been described in detail in other, more specialized books—croissants, sourdough bread, stock. We want to stick to what is achievable at home (good croissants rarely are) and what our customers want from the cookbook. We would much rather give a couple of extra salad recipes than spend the same number of pages on chicken stock.

My mother clearly remembers my first word, ma, short for marak (“soup” in Hebrew). Actually, I was referring to little industrial soup croutons, tiny yellowish pillows that she used to scatter over the tray of my highchair. I would say ma when I finished them all, and point toward the cupboard.

As a small child, I loved eating. My dad, always full of expressive Italian terms, used to call me goloso, which means something like “greedy glutton,” or at least that’s what I figured. I adored seafood: prawns, squid, oysters—not typical for a young Jewish lad from Jerusalem in the 1970s. A birthday treat would be to go to Sea Dolphin, a restaurant in the Arab part of the city and the only place that served nonkosher sea beasts. Their shrimp with butter and garlic was a building block of my childhood dreams.

Another vivid memory: me, aged five, my brother, Yiftach, aged three. We are out on our patio, stark naked, squatting like two monkeys. We are holding pomegranates! Whenever my mom brought us pomegranates from the market, we were stripped and banished outside so we didn’t stain the rug or our clothes. Trying to pick the sweet seeds clean, we still always ended up with plenty of the bitter white skin in our mouths, covered head to toe with juice.

My passion for food sometimes backfired. My German grandmother, Charlotte, once heard me say how much I loved one of her signature dishes. The result: boiled cauliflower, with a lovely coating of buttered bread crumbs, served to me at 2:00 p.m. every Saturday for the next fifteen years.

My other nonna, Luciana, never quite got over her forced exile from the family villa in Tuscany. When I think of it, she never really left. She and my nonno, Mario, created a Little Italy in a small suburb of Tel Aviv, where they built a house with Italian furniture; they spoke Italian to the maid and a group of relatives, and ate Italian food from crockery passed down the family. Walking into their house felt like being teleported to a distant planet. There they were, sipping Italian coffee, nibbling the little savory ciambelline biscuits. And then there was an unforgettable dish, unquestionably my desert-island food: gnocchi alla romana, flat semolina dumplings grilled with butter and Parmesan.

But I started my professional life far away from the world of prawns, pomegranates, and Parmesan. In my early twenties, I was a student of philosophy and literature at Tel Aviv University, a part-time teaching assistant, and a budding journalist editing stories at the news desk of a national daily. My future with words and ideas was laid out for me in the chillingly clear colors of the inevitable—that is, a PhD.

I decided to take a little break first, an overdue gap year that was later extended into one of the longest “years” in living memory. I came to London and, much to my poor parents’ alarm, embarked on a cookery course at Le Cordon Bleu. “Come on,” I told them, “I just need to check this out, to make sure it’s not the right thing for me.”

And I wasn’t so sure that it was. At thirty, you are ancient in the world of catering. Being a commis chef is plain weird. So I suffered a bit of abuse and had a few moments of teary doubt, but it became clear to me that this was the sort of creativity that suited me. I realized this when I was a pastry chef at Launceston Place, my first long-standing position in a restaurant, and one of the waiters shouted to me down the dumbwaiter shaft, “That was the best chocolate brownie I’ve ever had!” I’ve heard this many times since.

I was born to Palestinian parents in the old city of Jerusalem. It was a small and intimate closed society, literally existing within the ancient city walls. People could have lived their entire lives within these confines, where Muslims shared a minute space with Arab Christians and Armenians, where food was always plentiful on the street.

In a place where religion is central to so many, ours was a nonreligious household. Although Arab culture and traditions were important at home, and are still very much part of my psyche, I did not have the identity that comes with a strong belief. I found it hard to know where I belonged, and this was something I could not talk about at home.

From an early age, I was interested in cooking and would spend many hours in the kitchen with my mother and grandmother. Cooking formed the main part of most women’s lives. Men did not cook, at least not like women did. My father, however, loved cooking for pleasure alone. My mother cooked to share the experience with her friends and the food with her family. I believe I have inherited both my father’s love of food and my mother’s love of feeding people.

Some of my earliest memories are of my father squatting on the floor, preparing food in the traditional Arab way. He took endless trouble over preparation, as did my mother. She would spend ages rolling vine leaves, stuffed with lamb and rice, so thin and uniform they looked like green cigarettes. I remember my mother’s kitchen before a wedding, when friends and relatives gathered to prepare. It seemed as if there was enough food to feed the whole world!

My father was the food buyer. I only had to mention his name at the shop selling freshly roasted coffee beans and I got a bag of “Hassan’s mix.” Dad used to come home with boxes piled high with fresh fruit and vegetables. Once, when I was about seven, he arrived with a few watermelons. Being the youngest, I insisted on carrying one of them into the house, just like my brothers and sisters. On the doorstep, I couldn’t hold it any longer and the massive fruit fell on the floor and exploded, covering us all with wet, red flesh.

I was fifteen when I got my first job, as a kitchen porter at the Mount Zion Hotel. This is the lowliest and hardest job in any kitchen. You run around after everybody. I was lucky that the head chef saw my potential and encouraged me to cook. By then I was cooking at home all the time. I knew that this was what I wanted to do in life. It meant making the break from the Arab old city and entering Israeli life on the other side of the walls. I wanted to cook and explore the world outside, and Israeli culture allowed me to do this.

I made the significant move to Tel Aviv in 1989 and worked in various catering jobs before becoming assistant head chef at Lilith, one of the best restaurants in the city at the time. We served fresh produce, lightly cooked on a massive grill. I was entranced by this mix of Californian and Mediterranean cuisines, and it was there that I truly discovered my culinary identity and confidence. I moved to London in 1997 and was offered a job at Baker and Spice. During my six years there, I reshaped the traiteur section, introducing a variety of dishes with a strong Middle Eastern edge. This became my style. Recently I was in the kitchen looking at a box of cauliflower when my mother’s cauliflower fritters came to mind, so that was what I cooked. Only then did I realize how much of my cooking is about recreating the dishes of my childhood.

It was definitely some sort of providence that led us to meet for the first time in London in 1999. Our paths might have crossed plenty of times—we had had many more obvious opportunities to meet before—and yet it was only then, thousands of miles away from where we started, that we got to know each other.

We were both born in Jerusalem in 1968, Sami on the Arab east side and Yotam in the Jewish west. We grew up a few kilometers away from each other in two separate societies, forced together by a fateful war just a year earlier. Looking back now, we realize how extremely different our childhood experiences were and yet how often they converged—physically, when venturing out to the “other side,” and spiritually, sharing sensations of a place and a time.

As young gay adults, we both moved to Tel Aviv at the same time, looking for personal freedom and a sense of hope and normality that Jerusalem couldn’t offer. There, we first formed meaningful relationships and took our first steps in our careers. Then, in 1997, we both arrived in London with an aspiration to expand our horizons even further, possibly to escape again from a place we had grown out of.

So finally, on the doorstep of Baker and Spice in west London, we chatted for thirty minutes before realizing that we shared a language and a history. And it was there, over the next two years, that we formed our bond of friendship and creativity.

We are not the type of systematically thorough chefs who are incredibly well versed in all kinds of exotic ingredients (you could easily embarrass us by naming some French cheese that we haven’t got a clue about). Rather, we have some star ingredients that we feature over and over again, components that we love and feel at home with. These are the building blocks of our recipes.

We like salt, and we are not embarrassed to admit it. It is vital in any dish (cakes as well) and is often underused, meaning much of your culinary effort goes to waste. We recommend salting lightly at the beginning of the cooking process and then once again, after tasting, at the end.

We use ordinary sea salt when the texture is not an issue but recommend using coarse sea salt (our favorite is Maldon) for recipes in which the salt doesn’t totally dissolve during the cooking process, particularly when roasting.

In our mind, you can’t go wrong with garlic, but we are aware that some find it overwhelming, or just plain stinky. We seriously advise that you try to get hooked like us. You won’t look back. Good garlic is fresh, hard, and pale. Cloves that have started growing a shoot and are yellowish do not usually taste of much.

This is another substance prone to foster addiction. Lemon juice can transform boring to exciting in a squirt.

Lemon prevents some ingredients, such as apple and avocado, from discoloring, but others, such as green beans and some fresh herbs, lose their color soon after coming into contact with lemon juice. We often use the zest instead, which gives a wonderful aroma. Unsprayed Italian lemons with their leaves still attached are great (you can tell by the leaves how fresh they are), but they don’t always have much juice.

We use olive oil almost everywhere, even in some cakes, where it adds moisture and a rich depth of flavor. For most things, we use extra virgin oil. We like the Greek Iliada. It is semi-robust, with a light, grassy background aroma. For frying we use light olive oil or a good vegetable oil.

Although it is often associated with pastes and curries, we like to use fresh cilantro in salads and light sauces. If you like the flavor, stir the leaves into roasted vegetables and wet-roasted meats and fish. It is easy and highly effective.

Alongside lemon, mint epitomizes freshness. A few leaves added to a leafy salad will give it a cleansing vibrancy. Some types of mint, though, can be a little tough and bitter, so you need to chop them finely. Dried mint goes very well with yogurt, and doesn’t discolor as fresh mint does.

Any Ottolenghi fan knows how obsessed we are with yogurt. It has countless magical qualities for us. It adds an appealing lightness that counters the warmth of spicy or slow-cooked dishes. It balances and bridges contrasting flavors and textures. It lends freshness and moisture to dry ingredients. It goes well with almost anything you can think of: fresh vegetables, roasted meat and fish, hearty legumes, meringue, and berries.

For most purposes we use Greek yogurt, with up to 10 percent fat. Because some of the liquid has been drained out, it is creamy and intense. Ordinary plain yogurt, typically with 4 percent fat, produces a less flavorful sauce and you would need to use more of it to get the same result. Using low-fat yogurt doesn’t make sense at all—it is watery in texture and taste. Pure sheep and goat’s milk yogurts are fantastically powerful.

We are not sure that we can take credit for it, but Ottolenghi started using pomegranates well before Marks & Spencer began selling little baskets of the crunchy seeds, and before they won the (ever-fleeting) title of “superfood.”

Pomegranates are easy to deseed (see Fennel and feta with pomegranate seeds and sumac) and make a fantastically attractive garnish for vegetable dishes, some roasted meat and fish, and when scattered over creamy desserts. Pomegranate molasses is cooked-down pomegranate juice. It is intense, a bit like balsamic vinegar, and should be used sparingly in sauces. You can buy it from Middle Eastern grocers and some supermarkets.

Another invaluable item in our kitchen, tahini is a thick paste made from sesame seeds. We make it into a sauce, which we add to vegetables, legumes, meat, or fish, giving them sharpness and a certain richness. We don’t recommend the health-store variety of tahini, where the sesame seeds are left unhulled. It is heavy and overpowering. Use a Greek variety or a Lebanese brand, such as Al-Yaman, available from Middle Eastern groceries.

Sumac is a spice made from the crushed berries of a small Mediterranean tree. A dark red powder, it gives a sharp, acidic kick to salads and roasted meat.

Za’atar is a Middle Eastern blend of dried thyme, toasted sesame, and salt. It is earthy, slightly tangy, and used like sumac. Often the two are mixed together. Both make great garnishes for a plate of hummus or labneh (see this page). Many supermarkets now stock sumac and za’atar with the herbs and spices.

These two syrups made of blossom infusions are basic building blocks in many Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cuisines. They are used to flavor the ubiquitous baklava, as well as other cakes and desserts, and make an unusual addition to savory dishes, mainly poultry. Use an original Lebanese brand like Cortas.

We use maple syrup to sweeten many savory dishes. It has a substantial enough basic depth but isn’t as dominant as honey. It doesn’t need to dissolve, like brown sugar, so can be easily mixed into cold sauces and dressings. Use pure maple syrup, nothing else.

Ideally, you’d make your own stock. Nothing beats it. You can find reliable recipes in most comprehensive cookery books. Make a large amount and freeze in small portions. Our second choice would be purchased house-made stock. Butcher’s shops, delis, and many supermarkets carry them. A third option is to use powder. The only one we can recommend is the Swiss Marigold brand. It isn’t the real thing, but it does (part of) the job.

Moist Greek feta and similar Turkish varieties are invaluable. They enhance any vegetable, some fruits, and all savory baked products. Always look at the cheese counter before going for the vacuum-packed varieties, preferably in a Balkan or Middle Eastern deli. The unbranded chunks, swimming in murky water, are best. Ask to taste!

This is our comfort food of choice. The astonishing thing about sweet potatoes is how easy they are to cook. Throw one in the oven for up to an hour and you can scoop out the tasty, moist, and (obviously) sweet flesh, ready to be scoffed on its own with a little butter, mashed, turned into a pie, added to salads, gratinéed lightly, or served on the side with meat. Select potatoes with the ubiquitous orange flesh. The pale-fleshed ones don’t do the trick.

Not many ingredients taste as great as they look. Passion fruit are luscious and sensual in appearance and also have a sublime flavor. Despite their majestic qualities, they are very simple to use. Passion fruit pulp makes a most convincing sweet garnish (see the jam recipe) and the juice makes a curd almost as good as lemon curd.

You don’t need many of these little red jewels to transform the appearance of a dish and give it a sweet, perfumed, and yet not very peppery taste. We grind them in a pepper mill or with a mortar and pestle.

We are aware of the angst the idea of baking or making desserts evokes in some. Sorry, we are not going to try to convince you that this phobia has no grounds. Cakes and pastries can sometimes go horribly wrong, they are almost impossible to resurrect, and they do take time to prepare.

Still, the gratification of good baking is unbeatable. A great tart or a bowl of homemade biscuits is a clear mark of a mature cook, and we desperately encourage any person who loves breads, cakes, and sweets to try to make them at home.

Most of the recipes we selected for this book should be feasible for beginners. A few require modest baking experience. We suggest that you read through a recipe and embark on it only if you feel relatively confident. Still, we wouldn’t venture into most baking recipes without some basic equipment, some of it not found in every kitchen.

The minimum, really, is a handheld electric mixer. This will allow you to cream butter and sugar, whisk eggs, and whip up cream. A much better option is a proper stand mixer, one with a whisk, a paddle (or beater) attachment, and a dough hook. A solid brand, like Kenwood or KitchenAid, will permit you to try your hand at making brioche, breads, serious meringues, and much more.

Although not essential, a blender is a very handy tool when making fruit purées and puréeing sauces and soups. The handheld immersion blender is exceptionally practical, cheap, and hassle free (saves you lots of washing up).

Having the right baking pans and molds is essential. You can make some allowances with the shape of a cake pan or a tart pan or some of their ornamental features, but essentially you need them to have certain proportions. The risks of using a shallow pan for a recipe requiring a deep one or vice versa are endless. If you have a modest collection of baking pans, you should be fine.

Small tools but absolutely essential if you want to get anywhere. Both straight-blade and offset-blade icing spatulas are handy.

And then there are a few ingredients and techniques that are specific to the patisserie or bakery and need to be understood a little.

All-purpose flour is what we use in most of the recipes. It is relatively soft, or low in gluten, which means it will make products with a short, crumbly consistency like most cakes and cookies. Bread flour is used to make breads and some pastries. It gives the characteristic elastic or chewy consistency. Don’t substitute one type for the other when baking.

Unless we state otherwise, the chocolate used in our recipes should contain 52 to 64 percent cacao solids to yield the right result.

There are three main types of commercial yeast available. Fresh compressed yeast is what professional bakers use. You can find it in some health-food shops and a few supermarkets, or if you happen to have a friendly baker in the vicinity. The best option for a home baker is active dry yeast. It gives perfectly good results, is available in most supermarkets, and is easy to use. Active dry yeast, weight for weight, is twice as strong as fresh yeast.

The third type is quick-acting dry yeast (also known as fast-rising, instant, or quick-rise yeast). It comes as a powder that can be added directly to the flour and does not need hydrating. It is even stronger than ordinary dry yeast. Check the instructions on the packet for the required quantity.

This is the starting process of many cakes and cookies, where you aerate a paste of butter and sugar before adding eggs and flour to it. It is important to incorporate as much air as the recipe specifies. The mix will go whiter and puffier the more you cream it. The eggs should be added a little at a time, proceeding only when the previous addition has been thoroughly incorporated into the butter and sugar. Once this is done, the dry ingredients must be added all at once and you should work the mix just until everything is incorporated, no longer. You can cream with a whisk—or, better, with an electric mixer.

Brush your pans and molds thoroughly with vegetable oil or melted butter and then line with parchment paper that has been cut to the right size. It pays off. The last thing you want is for a cake to stick obstinately to the pan.

The issue of baking times could easily turn into a sore point after a colossal disappointment. People tend to underbake cookies, tarts, and breads and to overbake chocolate cakes and brownies. Keep in mind that baking times can vary a lot depending on your oven, the pan used, how full the pan is, and also on specific ingredients and techniques. Follow the instructions in the recipes but also try to develop an ability to observe and judge. Check often at different stages of the baking process (but don’t open the oven unless absolutely necessary).