1

CARDIOLOGY

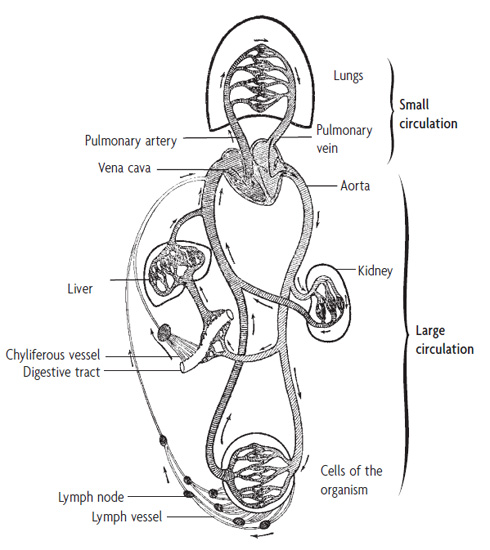

The cardiovascular system is centered in the heart, which is surrounded by a protective sheath called the pericardium. The heart muscle has its own blood vessels—coronary arteries and coronary veins—which keep it well supplied with the oxygen it needs to pump blood to the far reaches of the body, into every cell. The blood circulates from the heart to the organs through the arteries and returns from the organs to the heart in the veins.

HEART

Our discussion of the heart includes the heart wall, the myocardium, and the endocardium.

The Felt Sense of the Biological Conflict

Problems of the heart can manifest if an individual has fears about the emotional or physical strength of his heart. An example is the athlete who told me, “I’m not making it: my heart isn’t strong enough.” Symptoms of the myocardium relate to a conflict of low self-esteem regarding the efficiency of one’s heart. Likewise, a patient with problems related to her endocardium reported of her felt sense: “It’s tearing my heart out.”

Another patient, who had been diagnosed with atrophy in the right auricle, said this of her felt sense: “When my mother was carrying me, she took poison to cause an abortion but it didn’t work. I imagine her with poison in her veins and not being able to move, as with venom. It’s important to slow down circulation so that the poison doesn’t reach me; atrophy of the right auricle is the best solution for my survival.”

Figure 1.1. Circulation of the blood and lymph

Neuronal connection: Brain marrow

PERICARDIUM

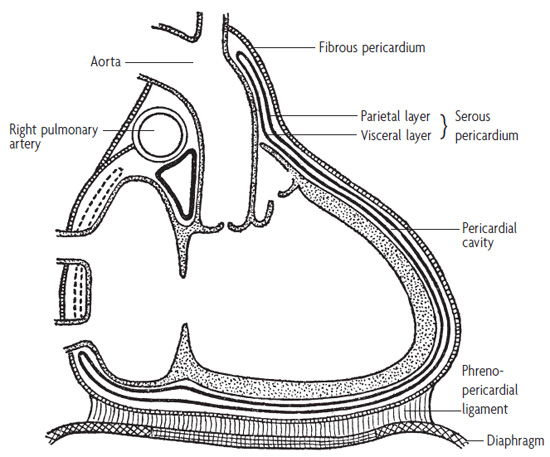

The pericardium is a double-layered, protective sheath that encloses the heart and the roots of the great blood vessels.

Figure 1.2. General structure of the pericardium.

(Vertical and anteroposterior section of the heart)

The Felt Sense of the Biological Conflict

Problems with the pericardium are linked to three main emotional conflicts:

- A perceived direct attack on one’s heart. For example, someone scheduled to have a heart operation may feel that her heart will be under attack.

- Fear for one’s heart or the heart of others—emotionally or physically. Thus the adage to be careful with one’s heart. This fear also relates to concern that pains, palpitations, swollen legs, and other physical symptoms are because of a cardiac problem. In addition, when a loved one has heart trouble, this can be experienced as a personal difficulty, that is, affecting one’s own heart.

- Violation of the integrity of one’s territory.

Example:

Mrs. P had a blood

pressure of 140/110; the two figures were close, which suggested to me a conflict

linked to the pericardium. From 1965 to 1975, she had struggled to prolong the

life of her father, who had a heart condition. In 1975 her father died, followed

by the tragic death of her mother. Was this because of heart failure? That’s

what Mrs. P came to believe. Since then, she has feared for her own heart whenever

she has pain, which has manifested in a physical problem with the pericardium.

Mrs. P had a blood

pressure of 140/110; the two figures were close, which suggested to me a conflict

linked to the pericardium. From 1965 to 1975, she had struggled to prolong the

life of her father, who had a heart condition. In 1975 her father died, followed

by the tragic death of her mother. Was this because of heart failure? That’s

what Mrs. P came to believe. Since then, she has feared for her own heart whenever

she has pain, which has manifested in a physical problem with the pericardium.

Neuronal connection: Center of the cerebellum

CORONARY ARTERIES

The coronary arteries branch from the aorta and circle the heart like a crown. They infuse the heart with blood, and are therefore called upon in times of stress to increase their output.

To understand the biological conflict, we can imagine an old stag who has been attacked within his territory and must mobilize all his strength to win. He does not economize. He develops an amazing power, which requires a lot of oxygen. He is under stress and in an active conflict stage.

In order to be as mobilized as possible, he must be in a state of permanent crisis, without any phase for rest. This is the best way to have more energy. To give strength to the muscles, he must have a lot of oxygen to feed aerobic combustion. Blood carries the oxygen, so the heart accelerates the arrival of blood. It’s the coronary arteries that feed the heart, so the heart “hyper-arterializes” its cardiac muscle. The order given by the brain is to “scour” the coronary arteries and thereby expand their output. The artery wall becomes thinner since the output of blood is more important. This provokes an ulcer in the coronary artery. Later, during the recovery phase, the artery engages in repair and risks becoming blocked.

The heart is irrigated by about twenty arteries in all. Because of this, it can continue to live in a reduced state even if 60 percent of the arteries are no longer working. The heart is not going to stop working if only one of its arteries is blocked.

During an experiment on a dog weighing 150 pounds, one of the three large arteries was tied. The dog immediately created an infarction in this artery—that is, the artery died for lack of oxygen—but the dog remained alive. Every two weeks, X-rays were taken of the coronary arteries, which showed that the collateral arteries “grew” around the blocked artery. After four months, the dog’s body had readjusted and the blood flow was normal thanks to the arteries that were near the one that had been tied. Later, a second coronary artery was tied; then, later still, a third was tied. The dog survived. There had been no conflict due to loss of territory, so no cerebral pathology had occurred.

In contrast, you can make a wonderful home for a dog and feed him well. But after a certain time, if you chase him away and give his home to another dog, the first dog, who has lost his territory, could very likely develop an infarction (heart attack) in three months’ time. For the stag, this process—from loss of territory to heart attack—takes only a couple of weeks, corresponding to the two-week period of battle over territory that is followed by the rutting season.

This example of the stag shows how, during a territorial conflict, our biology decodes the conflict by transforming it into ulcerations in our coronary arteries. The ulcerations enlarge the arterial channel so that there is more room for blood to move through; in addition, the elasticity of the arterial wall is increased.

In nature, if a young stag confronts the old stag, this stress is an opportunity for the dominant old stag since it increases his vitality. The stress phase allows him to attack the young stag and drive him away. In this way, the old stag holds on to his territory. Once the battle has been won, the body moves into the healing phase with the possibility of the epic crisis, a myocardial infarction (heart attack). We see that nature has arranged two tests: In order to continue to procreate, the stag must win out over the young stag. He then must survive the healing phase. If the conflict lasts for a long time, if he exceeds the biological time, the old stag dies. He must not wait too long to resolve this crisis—otherwise natural selection intervenes.

Within the animal world, there is an instinctive need to concern oneself directly with one’s territory and with the content of this territory—spatial access to shelter, food and water, the herd or flock, females, babies, driving away of intruders, etc.—which is in the final analysis just an extension of the nest.

The Felt Sense of the Biological Conflict

In the human world, any of the following can be construed as “territory” and become the object of conflict: workplace and colleagues, spouse, family, home, car, hobby, and so on. The conflict can be a direct attack, leading sometimes to the loss of the familiar locale where you feel at home, where you are accustomed to being at ease. All at once something happens. And you feel right away the risk of having everything turned upside down! From that moment on, you have to struggle on all levels, remain super alert, and all the more since you don’t accept what’s happening. “Bloody hell!” you think to yourself. “This is my place here!”

Sometimes one feels prevented from directing one’s territory in the sense of being able to control one’s own company, the stock of the store, perhaps the household money. Or one has difficulty withstanding the mother-in-law who intrudes in the territory. And, being the boss, it can progress from: “Why did you do that without speaking to me first?” to dictatorship. The physical impact takes place when someone tries as hard as he can to remain the boss of his territory.

In a right-handed person, loss of territory or of the content of the territory (for example, when one’s partner leaves) often results in physical problems with the coronary arteries. This often manifests as a male sexual conflict relating to territory—territory that has been lost or that you no longer have, territory that you are fighting to gain or defend, and territory over which you wish to rule.

Conflicts over territory of a sexual nature may have the following consequences:

- In a right-handed man, physical problems with the coronary arteries

- In a left-handed man, problems with the coronary veins

- In a right-handed woman, problems with the uterine cervix

- In a left-handed woman, problems with the coronary arteries

In left-handed people, the biological conflict with sexual frustration is almost always accompanied by depression.

Conflicts over territory of a nonsexual nature may also engender the following physical consequences:

- In a right-handed man, problems with the bronchial tubes

- In a left-handed man, problems with the larynx

- In a right-handed woman, problems with the left breast

- In a left-handed woman, problems with the right breast

When an individual is at risk of losing his field of action, or his territory, he experiences the following phases.

1. Conflict phase: Mobilization of all the forces in order to restore the previous state of affairs

2. Healing phase: Healing the consequences of this enormous tour de force

If the conflict could not ever be resolved, we see two possible outcomes:

1. The individual continues his struggle and constantly attacks with full force up to the moment when, exhausted, he dies or is killed by his adversary.

2. The individual adapts to his conflict—adapts to a loss of territory. The conflict is transformed, reduced, and remains active but only slightly so, and he can therefore live with it. We call that a conflict in equilibrium. The individual can live to old age, but his vitality is diminished.

In a pack of wolves, a secondary wolf does not have the right to carry his tail in the vertical position, to lift his leg to urinate, or to growl in the presence of the leader. In addition, a secondary wolf no longer has anything to do with the she-wolves, with which he can no longer copulate. But it’s exactly this outcome that nature invented in order to construct the social structure of a group. This outcome then very clearly has its biological sense, particularly under these conditions. Obviously, such an individual will no longer ever be able to assume the position of chief.

Examples:

Mr. A lived in

Paris, in an apartment that belonged to his father. One day he invited in a

homeless person, but soon this person didn’t want to leave, and Mr. A could

no longer even come home! He had lost his territory. Some time later, when Mr.

A finally got back his apartment, he suffered from a heart attack.

Mr. A lived in

Paris, in an apartment that belonged to his father. One day he invited in a

homeless person, but soon this person didn’t want to leave, and Mr. A could

no longer even come home! He had lost his territory. Some time later, when Mr.

A finally got back his apartment, he suffered from a heart attack.

Mr. Y had a conflict

with a female colleague whom he had to oppose ceaselessly. She wanted to take

over his office and relegate him to a different, shabby office. Mr. Y always

wanted to do battle as soon as he saw her, but she was protected by the director

because she was his mistress. This conflict eventually manifested physically

with coronary problems.

Mr. Y had a conflict

with a female colleague whom he had to oppose ceaselessly. She wanted to take

over his office and relegate him to a different, shabby office. Mr. Y always

wanted to do battle as soon as he saw her, but she was protected by the director

because she was his mistress. This conflict eventually manifested physically

with coronary problems.

Mr. G met his wife

at the door to their home and she told him, “I’m never coming back.” His house

symbolically became a ruin for him. He experienced a shock in the conflict over

lost territory. In January, some friends told him that his marriage had been

a mistake and that it was better this way. On February 26, Mr. G had a pain

in the chest: heart attack.

Mr. G met his wife

at the door to their home and she told him, “I’m never coming back.” His house

symbolically became a ruin for him. He experienced a shock in the conflict over

lost territory. In January, some friends told him that his marriage had been

a mistake and that it was better this way. On February 26, Mr. G had a pain

in the chest: heart attack.

Other scenarios I have seen in which the felt sense of a loss of territory led to physical problems with the coronary arteries include: the family home being put up for auction, a child having a car accident, a person being “sent out to pasture,” losing a job, and not accepting retirement, an adolescent who was difficult and ran away from the parent.

Neuronal connection: Right peri-insular cortex

CORONARY VEINS

In the animal kingdom, during certain periods of stress there is an instinctive need for the male to pay frequent attention to the female. This may involve coupling with her if she’s in heat or making sure she has enough food and that she is secure in the confines of her spatial areas so that she need concern herself only with the production of babies and the care that they require. The male helps to create the necessary conditions for the future family territory—the nest or cocoon.

The Felt Sense of the Biological Conflict

In the human domain, conflicts of the coronary veins can be inferred from a feeling of lack or frustration in regard to one’s emotional responses, sexual relations, or the sense of one’s own importance. When the emotional impact strikes deeply, and when it involves at the same time a great disappointment—a lack accompanied by a strong element of frustration and a feeling of total abandonment—the coronary veins are affected at the same time as the uterine cervix.

This conflict is one of sexual frustration in the broad sense—that is, lack of relationship or exchange with one’s partner. It can apply to a person who is heartsick, lovesick, or heartbroken. It may also involve conflict over loss of sexual territory, a triangular relationship in which a woman is caught between two men, or feeling powerless to bring a husband back home. In these situations of shock, there is a fear of belonging to no one, of being interesting to no one.

The other critical element, which often appears in a well-defined way and which often affects men, is dependence. An unhealthy dependence appears in relation to the partner that one feels is overly considerate or overly indifferent. This is accompanied in certain cases by a painful physical or psychological context—an illness, for example. A man who has been hospitalized for a long time and who fails to recognize that it’s been his wife who took care of everything can suffer from this conflict when he understands that in normal times he would have been the one to make all the decisions.

Examples:

Mr. T suffered

from an irregular heartbeat (tachycardia). At the age of eighteen, he suffered

his first attack of tachycardia. He wanted to discover sexuality but he felt

guilty. He found himself continually frustrated. At twenty-six, a second crisis

occurred. At this time sex was impossible for him because he experienced pain

in his penis due to a short frenulum of prepuce. He met his future wife and

experienced a rush and a glimpse of something more. Because of the physical

condition that hampered his sex life, he experienced a serious frustration conflict

and suffered from another attack of tachycardia.

Mr. T suffered

from an irregular heartbeat (tachycardia). At the age of eighteen, he suffered

his first attack of tachycardia. He wanted to discover sexuality but he felt

guilty. He found himself continually frustrated. At twenty-six, a second crisis

occurred. At this time sex was impossible for him because he experienced pain

in his penis due to a short frenulum of prepuce. He met his future wife and

experienced a rush and a glimpse of something more. Because of the physical

condition that hampered his sex life, he experienced a serious frustration conflict

and suffered from another attack of tachycardia.

Neuronal connection: Left peri-insular cortex

ARTERIES

In discussing the arteries, we include the carotids, the aortic arch, and the pulmonary arteries.

The Felt Sense of the Biological Conflict

Problems with the carotids relate to a loss of intellectual territory and the feeling of needing to defend one’s ideas. An example is having your copyright or patent stolen. Biologically, the arteries scour themselves and allow more blood to be brought to the brain. When one’s ideas are abandoned, the carotid is stuck.

Symptoms of the artery near the thyroid relate to a conflict of loss of extended territory and an urgency around solving the conflict. For example, a woman who fears that another woman wants to take her man may hurry to marry him for fear of losing him.

Symptoms of the pulmonary arteries and aorta link to the emotional conflict of a loss of extended, peripheral, or terminal territory, or a scattered territory.

Neuronal connection: Right peri-insular cortex

VEINS

Our discussion of the veins applies to all veins except the coronary veins.

The Felt Sense of the Biological Conflict

Symptoms of the veins are linked to a reduction of self-worth: one feels inadequate for being unable to keep oneself going, or to do one’s job. This is related to feelings of having to go back and get rid of bad blood, muck, or other problems, but being unable to go home, unable to return to the center of the family territory linked to blood and to the heart.

Specific Disorders of the Veins

- Angioma: Symptomatic of a mother’s anguish for a part of the body. After the birth of her first child, Mrs. C heard her mother say, “Ugh, his head is abnormal.” Mrs. C was very troubled during the pregnancy of her second child, hoping that his head would be normal. Upon the child’s birth, he had an angioma on his neck.

- Heavy legs: Relates to the feeling of carrying too heavy a load.

- Raynaud’s disease: Involves a constriction of the blood vessels, which makes the extremities white or blue, and “icy.” The failure of the body to transmit the information required to make the oxygenated blood circulate is related to feelings of being ineffective or inefficient. The reduction of self-worth related to Raynaud’s may come from not being able to reach, retain, take, capture, or do something in particular, or from not being able to keep one’s composure. Raynaud’s is also linked to conflicts of loss of territory in cases of separation or death, and the feeling of wanting to hold on to someone or something that is dead. In Raynaud’s disease there is often an additional conflict in the pericardium, related to fear for the heart.

Examples:

A woman who was

raped became pregnant and had an abortion. She developed varicose veins because

a weight had been lifted from her.

A woman who was

raped became pregnant and had an abortion. She developed varicose veins because

a weight had been lifted from her.

Mrs. T suffered

from periphlebitis. She described her felt sense as follows: “Putting up with

my husband is hard. He’s never happy; he sees the dark side of everything. I

have to always be cheering him up. I had a happy childhood—my parents got along

well. Because of this I’m always trying for a united home.” Mrs. T experienced

phlebitis when there was conflict between her husband and her father, who had

just been widowed, and again when conflict arose between her two children. “I’m

always trying to get rid of problems,” she says. “It’s veins that send back

the dirt.”

Mrs. T suffered

from periphlebitis. She described her felt sense as follows: “Putting up with

my husband is hard. He’s never happy; he sees the dark side of everything. I

have to always be cheering him up. I had a happy childhood—my parents got along

well. Because of this I’m always trying for a united home.” Mrs. T experienced

phlebitis when there was conflict between her husband and her father, who had

just been widowed, and again when conflict arose between her two children. “I’m

always trying to get rid of problems,” she says. “It’s veins that send back

the dirt.”

Mrs. A had pain

in the popliteal space (behind the knees). Her doctor told her she had vascular

problems. What was the conflict? Her twenty-five-year-old son lived with her.

He was a secondhand dealer who cleaned out attics and put his “junk” in the

garden, in the garage, and in the living room. It was a never-ending dirty bazaar

in her home. She wanted him to take away all this rubbish. She went on vacation

and just before she was about to return he phoned her and said, “Don’t come

back right away, I haven’t cleaned up enough yet.” Mrs. A experienced a shock

from this conflict—the conflict of a load of dirt that had to be carried up,

a conflict that manifested in her vascular problems.

Mrs. A had pain

in the popliteal space (behind the knees). Her doctor told her she had vascular

problems. What was the conflict? Her twenty-five-year-old son lived with her.

He was a secondhand dealer who cleaned out attics and put his “junk” in the

garden, in the garage, and in the living room. It was a never-ending dirty bazaar

in her home. She wanted him to take away all this rubbish. She went on vacation

and just before she was about to return he phoned her and said, “Don’t come

back right away, I haven’t cleaned up enough yet.” Mrs. A experienced a shock

from this conflict—the conflict of a load of dirt that had to be carried up,

a conflict that manifested in her vascular problems.

Miss X had circulation

problems in both legs, halfway up both thighs, as well as in her face. Her legs

turned purple from time to time. She’d had capillary problems since grade nine.

She thought of herself as unattractive, as fatter than her girlfriends. When

she wore a skirt that came down to mid-thigh the boys made fun of her. This

shock led to a reduction of esthetic self-worth in the visible skin, which meant

her two legs to mid-thigh and her face. She wanted to eliminate what was unnecessary—fat—and

it is the role of the capillaries to get rid of what is useless.

Miss X had circulation

problems in both legs, halfway up both thighs, as well as in her face. Her legs

turned purple from time to time. She’d had capillary problems since grade nine.

She thought of herself as unattractive, as fatter than her girlfriends. When

she wore a skirt that came down to mid-thigh the boys made fun of her. This

shock led to a reduction of esthetic self-worth in the visible skin, which meant

her two legs to mid-thigh and her face. She wanted to eliminate what was unnecessary—fat—and

it is the role of the capillaries to get rid of what is useless.

Mr. J had pain

in his right calf related to trouble with his veins. His father was not doing

well. Mr. J had eight brothers and sisters and it was up to him to look after

life insurance and inheritance papers. All that kind of thing—inheritance, money—was

perceived as muck by Mr. J. He was the only one who was knowledgeable about

all these papers, and that weighed on him. He had to get by on his own. His

mother was overloaded and everyone depended on him. Speaking of the trouble

with his veins, Mr. J said, “I want to clean up this endless muck.”

Mr. J had pain

in his right calf related to trouble with his veins. His father was not doing

well. Mr. J had eight brothers and sisters and it was up to him to look after

life insurance and inheritance papers. All that kind of thing—inheritance, money—was

perceived as muck by Mr. J. He was the only one who was knowledgeable about

all these papers, and that weighed on him. He had to get by on his own. His

mother was overloaded and everyone depended on him. Speaking of the trouble

with his veins, Mr. J said, “I want to clean up this endless muck.”

Mrs. F had trouble

with her veins and her legs felt heavy. She was always tidying up the mess that

her husband and her son made in the house. This was her regular, programmed

conflict, which had been triggered in her childhood. Her mother worked outside

the home and Mrs. F felt lonely and wished for her mother to return. The home

represents the heart and the veins return toward the heart, toward home. When

Mrs. F talked of pain in her right calf, she associated it with her husband

not being sensible and creating money problems. She said, “We’re sinking; it’s

going to be hard to get out again!” It was going to be difficult to push the

dirty blood back up to the heart, to the lungs, to bring them oxygen.

Mrs. F had trouble

with her veins and her legs felt heavy. She was always tidying up the mess that

her husband and her son made in the house. This was her regular, programmed

conflict, which had been triggered in her childhood. Her mother worked outside

the home and Mrs. F felt lonely and wished for her mother to return. The home

represents the heart and the veins return toward the heart, toward home. When

Mrs. F talked of pain in her right calf, she associated it with her husband

not being sensible and creating money problems. She said, “We’re sinking; it’s

going to be hard to get out again!” It was going to be difficult to push the

dirty blood back up to the heart, to the lungs, to bring them oxygen.