The Great American Eclipse and Beyond

Totality’s eerie light bathes the ring of massive monoliths as robed figures chant and burn their sacrificial offerings. Around them, the gathered throngs raise their voices in joy and smile for the cameras of the CBS Evening News. It is 1979, and the scene is a bizarre roadside re-creation of Stonehenge overlooking the Columbia River in western Washington State. Neo-pagans and curious onlookers have amassed to witness the rare event unfold overhead, and this being Washington (and the 1970s), it’s clear that not all the smiles and good vibrations are due solely to the solar eclipse.

Back in the studio, Walter Cronkite tells us there will not be another total solar eclipse to touch the continental United States this century. Not until the far-off date of 2017 will totality once more be so visible to so many on this continent.

I’ve been waiting to see this eclipse ever since.

The February 26, 1979, eclipse only touched a corner of the United States before swinging up into western Canada, and not even half the population of the United States today was alive for it. A continent-spanning eclipse hasn’t occurred in the United States since 1918, almost 100 years before what is being called the Great American Eclipse of 2017. While this may seem like a long time, consider that when Francis Baily saw his first totality in 1842, Western Europe had gone 109 years without seeing the solar corona at all. Halley’s eclipse in 1715 marked the end of a 500-year drought for England. Australia is currently in the midst of seeing eight total solar eclipses in a period of 64 years (1974 to 2038), but only after having seen none for the previous 52 years. Similarly, when the current American drought of thirty-eight years without a total solar eclipse ends in 2017, it will mark the beginning of a new thirty-eight-year period in which Americans will get to see five (in 2017, 2024, 2044, 2045, and 2052).

While, on average, any one spot on Earth will experience solar totality every 370 years, remote Baker Island in the Pacific Ocean is in the midst of a 3,000-year gap between totalities. Over time, these cycles of bounty and absence come and go, and every place on Earth is crossed eventually. For human beings, with our limited lives and limited means of travel, these vagaries of celestial alignment mean the majority of people on Earth have never seen a total solar eclipse.

THE 2017 SOLAR ECLIPSE

The first total solar eclipse most Americans will have ever seen begins the morning of Monday, August 21, 2017. It will begin two seconds before 10:16 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time (PDT). At that moment, the dark shadow of the Moon touches the Pacific Coast at Yaquina Head lighthouse outside the coastal town of Newport, Oregon. There is no doubt about this. Astronomers have a bad reputation when it comes to predicting amazing sights for the public. Too many “Comets-of-the-Century” turn into faint fuzzy duds that disappoint in the darkness. Too many meteor “storms” wind up being no more than a drizzle once you’ve woken the family at 2:00 a.m. But this eclipse is happening, in the middle of the day, exactly on time, and in exactly the places that are predicted. It is as certain as the sunrise.

The only question is a matter of clouds, and even those can be forecast with some certainty. The region with the best chance of clear skies all along the path of totality on that date is eastern Oregon, which the Moon’s shadow reaches at 10:19 and 36 seconds PDT as it crosses the Cascade Range and flies eastward at a speed of 2,265 miles per hour. The shadow then crosses into Idaho and the southern tip of Montana, where no roads lead into the Beartooth Mountains.

At 11:34:56 a.m. Mountain Daylight Time (MDT), the shadow reaches Jackson Hole Airport in the middle of Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park. This is one of two national parks totality touches, and the only one in the high mountain air of the western United States. Summer storms can be an issue, though. The weather for the week of August 21, 2014 (exactly three years before the eclipse), included rain and sleet; a year later, on August 21, 2015, it was mostly clear and sunny. The eclipse crosses Wyoming diagonally almost entirely along the line of Highway 26. For those looking to avoid any clouds and reach potentially clear skies in their cars, this could be the ideal racetrack for whichever direction it’s necessary to drive.

The lunar shadow then sweeps across the plains, reaching the border of Nebraska at 11:46 a.m., and the northeast corner of Kansas at 1:02 p.m. Central Daylight Time (CDT). Twenty-two minutes later, totality engulfs Kansas City, Missouri—the largest city yet along the path—right after lunchtime. A little farther east, at the University of Missouri in the town of Columbia, residents are expected to gather in the 71,000-seat Faurot Field football stadium. It will likely be the largest single gathering of spectators to see totality on the continent this day.

Totality reaches the Mississippi River south of St. Louis at 1:17:08 CDT. People living in Missouri’s largest city will see the Sun disappear above their homes, but only if they live south and west of the line between Creve Coeur Park and the Missouri Botanical Gardens. For those wishing to see totality from Forest Park, home of the famous 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, only the extreme southwestern corner of the park is within the path, and totality there lasts no more than 20 seconds.

At this point, onlookers all along the midline of the path have had at least two minutes of totality, but the residents of Carbondale, Illinois, will get to experience the eclipse’s greatest duration, two minutes and forty seconds. These folks are luckier still, as the very next total eclipse to touch the continent will sweep over their houses in 2024, allowing them to see two eclipses in seven years from their very own doorsteps.

From Illinois, the path leads over Kentucky and then crosses into Nashville, Tennessee—the largest city completely within the shadow of the Moon at 1:27:28 CDT. As totality leaves Tennessee, it crosses the southern half of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the most visited national park in the United States. In 2010, 9.4 million visitors came to this park, more than twice the number that visited the Grand Canyon that year. The highlight of the park is Cades Cove, a spectacularly beautiful valley set amid hardwood forests and rushing streams. Totality reaches here at 2:34:20 Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) and is visible in the park from much, but not all, of Newfound Gap Road as it crosses from Tennessee into North Carolina. The weather here can be hazy, though, especially on a summer’s afternoon. There’s a reason they call them the smoky mountains.

At 2:47 EDT, one hour and thirty-three minutes after coming ashore on the Pacific Coast, the Moon’s shadow crosses out into the Atlantic just north of Charleston, South Carolina. In that time it will have touched thirteen states, five state capitals, and 9.7 million residents, not counting the millions that will travel into the path to see it. For that one day, every man, woman, and child in North America will share in a phenomenon of wonder and joy. Though totality will take only ninety-three minutes to cross from sea to shining sea, during that time everyone on the continent will be within at least the partial shadow of the Moon and experience the eclipse together.

But not all views are equal.

Although the entire continent will witness at least a partial eclipse, the real show is within the zone of total darkness. You must get into the umbra, the darkest part of the Moon’s shadow where the disk of the Sun is totally covered. That is where the eclipse is total. Those in totality’s path see the diamond ring, Baily’s beads, the corona, and any prominences visible on the solar limb. Day becomes night and the brighter stars and planets, such as Venus and Mars, become visible near noon. You will understand the true meaning of awe.

While those near the midline of totality will see the longest darkness, those near the edge—but still just within the umbra—have the chance to see more edge effects, such as Baily’s beads and the deep red chromosphere (including prominences) that appear as the Sun just skirts behind the lunar edge. Those barely outside totality’s path may still see some Baily’s beads (if they are within just a few miles of the band); but, although the day will grow dark and colors will change, day will not become night, and no stars or planets will become visible. Here, outside the path of totality, the Great American Eclipse will be only partial, and special eclipse glasses will be needed for the entire event.

Make no mistake: The difference between being inside and outside the path of totality is the literal difference between day and night.

A GUIDE TO SAFELY VIEWING A SOLAR ECLIPSE

I saw the 1979 eclipse, my first, in complete safety at home: in a darkened room, with all the windows covered, watching it on TV. I missed experiencing the greatest awe-inspiring wonder that Nature has to offer because our local school officials—who felt that eclipse-watching was too dangerous for children and did not want to be held liable in the event of an injury—had issued overly cautious warnings. Regardless of whether those school administrators were right to be wary, not a year has gone by since that I haven’t felt cheated out of a life-changing experience.

Observing a solar eclipse can be dangerous if proper precautions are not taken. In that regard, viewing a solar eclipse is no different from many other sporting activities in which families and schools regularly take part. But unlike bicycle helmets, football pads, or lifejackets, the equipment needed to safely view a solar eclipse costs no more than a dollar or two, and you may even have it sitting around your house already.

First, you may be wondering what the potential harm is. The un-eclipsed Sun is visible every day, yet we don’t warn children to stay indoors on sunny days. While it is true that the Sun doesn’t emit any special rays during an eclipse, how we behave toward the eclipsed Sun does change. On a typical day, very few people willingly stare at the Sun for a prolonged period of time. Our eyes and brains know it isn’t good for us to shine that much light through the lenses of our eyes and focus it on our retinas, so we instinctively look away.

The concern for health officials during an eclipse is that people will stare at the Sun, particularly close to totality when the Sun may look like a crescent. People want to see this phenomenon, and so they will look at a particular sharp feature longer than they should, placing its image on a single part of the retina. Since there are no pain receptors in the retina, the damage that takes place as it burns produces no discomfort. For all its painlessness, the damage can be permanent. And particularly for young children with clear pupils that have not become dulled with age, the increased amount of light on the retina does make for more danger compared with adults.

The solution to this problem is simple: never look directly at the partially eclipsed Sun without proper eye protection. Either look through specially designed, filtered glasses, or project an image of the Sun on a screen, using a pinhole projector made from items found around the house or naturally outdoors. These two methods of seeing the partial phase of a solar eclipse are cheap, safe, and in the case of finding naturally occurring pinhole-projections, an enormous amount of fun.

Filters: The most widely available device for viewing the partial phase of a solar eclipse is simple, commercially available plastic or cardboard safety glasses. These glasses are inexpensive, typically $1 or $2, and are available from a number of websites. Local stores usually sell them in places where total eclipses occur. (See the end of this book for licensed suppliers.)

You should be unable to see anything through the lenses of these glasses other than the Sun. The special solar filter in these glasses can be delicate. Any holes or scratches they develop make them instantly worthless and potentially dangerous. Keep them protected. If you have any doubts, hold them up to a lightbulb: if you see any light at all coming through the lenses, throw them away and use another pair.

What not to use: Stay away from people offering to let you look through makeshift items like dark beer bottles, silver candy wrappers, CDs or DVDs, smoked glass, or dark sunglasses. These may make the Sun look dim, possibly even dim enough to look at without discomfort, but they may do nothing to block infrared or ultraviolet radiation that will cause permanent damage to the retina and possibly lead to blindness.

Projection: The cheapest, simplest, and absolutely safest method of watching a partial solar eclipse is to find a piece of cardboard and poke a small hole in it. Hold this outside and the sunlight passing through the hole produces an image of the Sun wherever the shadow of the cardboard falls. Place a sheet of paper on the ground or on a wall and everyone can see the eclipse progress together. Do not look through the pinhole at the Sun.

FIGURE 7.1. A small hole in a card, hat, colander (or any other item) will project an image of the partially eclipsed Sun. (Image by the author)

One of the most enjoyable parts of watching a partial solar eclipse (or spending time outside in the Sun waiting for totality to begin) is looking around for natural pinhole projectors. You can use leafy trees, woven hats, interlaced fingers, or any other place that tiny holes occur through which the eclipsed Sun shines, casting myriad crescents into their shadows.

Whether using filters or projection, once totality begins with the first diamond ring, you may put the filters and glasses aside and feel free to look at the Sun with the naked eye in complete safety, until the second diamond ring marks totality’s end.

PHOTOGRAPHING SOLAR ECLIPSES

My simplest recommendation for photographing a total solar eclipse is: Don’t do it! Typically, you will have no more than two minutes of totality. That’s 120 seconds. Why spend those precious seconds looking down at your camera’s instruction menu, trying to get your camera to focus, or working to get the exposure right? Reread the quote at the opening of this chapter. Even the very first person to ever photograph a total solar eclipse wished he had the chance to see another without the bother of equipment. If this is your first eclipse and you feel you must have a photo, someone else will take one and it will probably be better than yours.

If none of that dissuades you, here are a few tips to keep in mind for taking solar eclipse photos. There are links to specific websites with more detailed information at the end of this book.

1. During the partial phase of the eclipse, do not point your camera at anything you wouldn’t look at with the naked eye. You may be able to safely look at the monitor on the back of your digital camera, but your camera lens is focusing the Sun’s light on your sensitive camera optics. If you need a filter for your eyes, so does your camera.

2. If you are using a filter for your camera during the partial phase, remember to take it off during totality or you won’t capture anything.

3. During totality, the sky darkens enough for the brighter stars to appear. In the days before totality, go outside immediately after sunset and wait until the first, brightest stars appear. This is a fair approximation of how dark it will be. Experiment with taking photos at this time. How do they come out? Do you need a tripod for your camera to successfully take sharp, non-blurry, non-grainy photos under these conditions? If so, this will be another piece of equipment you will need to handle during those precious seconds of totality.

4. It will be dark during totality, but do not use a flash. It will blind everyone around you at exactly the moment they want to see the sky the most. Turn all flashes off.

5. The Full Moon is about as bright as the corona. Try taking photos of the Full Moon to see how long you need for the Full Moon to be properly exposed. Again, does this need a tripod?

6. The Full Moon is also the same size as the Sun and will be the size of the “hole in the sky” during the eclipse. Practice using your camera to photograph the Full Moon. How big does it appear in your image? Is this worth taking a picture of? Many of the best eclipse photos that show details of the corona and prominences use telephoto lenses with focal lengths of at least 500 millimeters (mm), but they cost thousands of dollars.

FUTURE ECLIPSES

If you miss the total solar eclipse of 2017—or, having seen it, you catch the bug and absolutely must see another—don’t worry, there are many more coming. The next total solar eclipse to touch the continental United States is April 8, 2024. On that day in midafternoon, the path of totality starts in Mexico, travels northward into Texas, and then crosses the central United States before passing through eastern Canada. The citizens of southern Illinois in the United States are the lucky ones: they will get to see two total solar eclipses in seven years without having to travel anywhere.

Perhaps the most spectacular views in 2024 will come for those on the US side of Niagara Falls. From the railing beside the water, the totally eclipsed Sun will hang directly above the crashing falls for three minutes and thirty seconds in what is sure to be a wild sensory-overload spectacle of sight and sound—assuming it is clear at that time of year, of course.

For those who like to travel, there are some exotic destinations for future solar eclipses that are tantalizing for the opportunities they afford. In July 2019, totality will sweep off the Pacific Ocean and across the Chilean Andes. The path will cross one of the great astronomical observatories of the Southern Hemisphere, the La Silla Observatory at an elevation of 7,900 feet (2,400 meters), operated by the European Southern Observatory. This is one of the darkest locations on Earth, and since solar eclipses happen at New Moon, those who travel here for the eclipse should stay to see the glories of the southern Milky Way high overhead throughout the night. It is a view unlike any available to us in Europe or North America, particularly with regard to the darkness of the night and the grandeur of our galaxy.

On December 4, 2021, at the height of the Southern Hemisphere’s summer, the totally eclipsed Sun will be visible from Antarctica and no other continent. The Sun and Moon will glide horizontally no more than about 20 degrees off the gleaming ice—about the distance spanned by your thumb and little figure extended at the end of your arm.

Surely one of the most awe-inspiring sights will be the total eclipse of August 2, 2027, from within the Temple of Luxor in Egypt. Totality will last over six minutes, the longest for the next thirty years, and hang in the darkened sky almost at the zenith, directly above the stone pillars and statues below. For those who can’t get to Egypt on that day, this particular path first touches ground passing precisely over the Strait of Gibraltar and the Pillars of Hercules (the Rock of Gibraltar in Spain and Jebel Musa in Morocco). Totality lasts for about four and a half minutes there before continuing over northern Africa to Egypt and across the Red Sea.

TABLE 7.1. Total and Annular Solar Eclipses Worldwide, 2017–2030

The solar eclipse of July 22, 2028, passes directly over Sydney, Australia, affording three and three-quarter minutes of totality, while South Australia is visited by totality just two years later on November 25, 2030.

Lest we forget total lunar eclipses, there is a special beauty to going out under a night sky brightly lit by a Full Moon. What begins with only a few stars visible against the glare of the Moon slowly turns into a thousand points of light as the eclipsed Moon darkens. By the time totality occurs, the sky is ablaze with stars; if totality occurs near the peak of a meteor shower, the dark-red Moon can be surrounded by shooting stars for the duration of totality. I saw this in August 2007 from Grand Teton National Park immediately after the Perseid meteor shower with the Milky Way arching overhead; it was one of the most magical moments I’ve ever experienced.

For such a night, consider the total lunar eclipse of July 27, 2018. It will occur two weeks before the peak of the Perseid shower, but a few meteors may be visible as the blood-red Moon hangs beside the brightest portion of the Milky Way for witnesses in Europe and Africa through Asia. To find more possibilities, and see the places you’ll need to go to follow the path of totality, visit any of the websites listed at the end of this book.

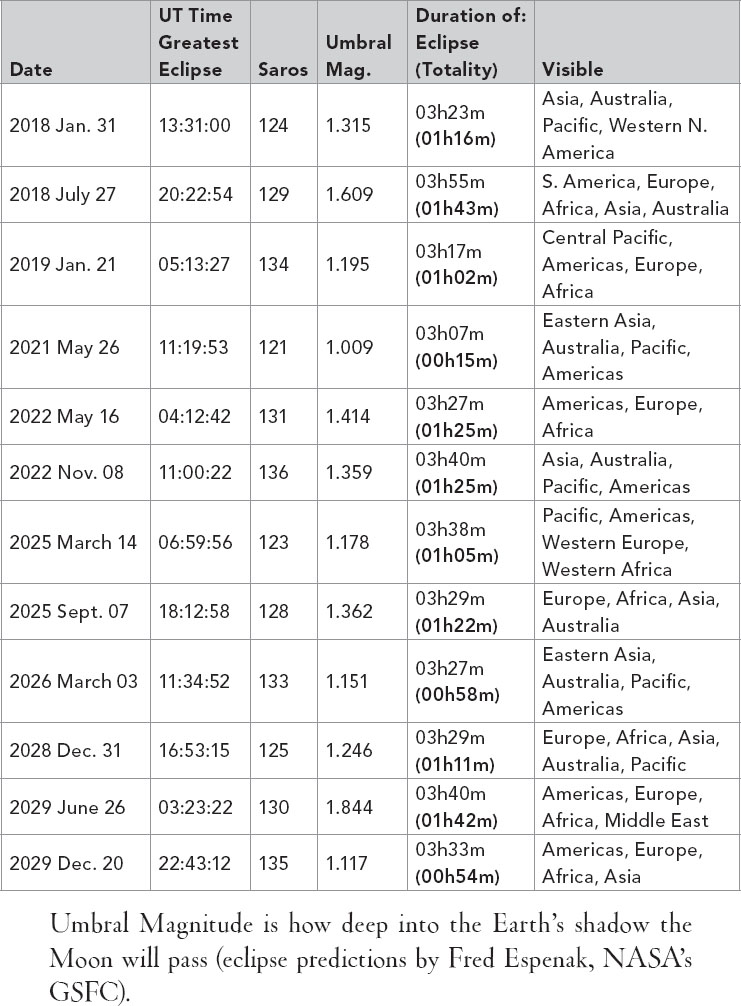

TABLE 7.2. Total Lunar Eclipses Worldwide, 2017–2030

Beyond 2030, I run into the conundrum that all eclipse-chasers eventually face: How many more will life allow me to see?