Unfettered growth in both domestic and global markets can be risky; managed growth needs to attend to specific contingencies. As with any aspiring firm, there are different trajectories to grow and to internationalize, each with benefits and risks.

—SKOLKOVO Business School–Ernst & Young Institute for Emerging Market Studies, Rough Diamonds: The 4Cs Framework for Sustained High Performance

Their mastery of marketing, operations, and management systems, however, departs in context and intent from firms in developed countries, or even from firms in their own countries that became successful when markets were first opened.

—SKOLKOVO Business School–Ernst & Young Institute for Emerging Market Studies, Rough Diamonds: The 4Cs Framework for Sustained High Performance

Of the Four Cs, growth strategies are among the most complex because the rough diamonds in the different BRIC countries have such diverse histories, legacies, and contingencies. In examining the growth paths, we found that Chinese firms are the most aggressive in diversification, Brazilian rough diamonds tend to take a more gradual stance, Russian companies tend to be more domestically focused, and the Indian rough diamonds are more internationally oriented.

Even with marketing savvy and operational excellence, rough diamonds cannot create sustained advantages without leveraging their competencies into continuous, profitable growth. They are often latecomers in a fairly competitive domestic market that can accommodate only so much demand. In order to take full advantage of their scaled-up operations, rough diamonds have to explore new domestic profit sanctuaries, if not participate in the global market as a whole.

Because rough diamonds have grown faster than most other firms in the past decades, it is important for them to manage growth effectively. To succeed as they expand, these firms have to be able to both build on their local skills and competencies and push those skills into new territories. Unfettered growth in both domestic and global markets comes with risks, including what we call the “growth fetish” or a misplaced goal of companies to grow for the sake of growth but without due consideration of consequences. (We discuss this in chapter 7.) So companies must manage their expansion and diversification well to accommodate market-to-market differences and the ongoing internal challenges of growth.

We posed this question during our research: Is there an optimal method by which rough diamonds in emerging markets manage their sustained growth? This formed the basis for the last of the Four Cs: cultivating profitable growth. In comparing patterns of expansion and diversification with the historical experiences of firms in developed countries, we found that the rough diamonds are particularly attentive to both profitability and growth. This means they must attend to complex trade-offs between sales growth and profits, which we discuss in the next chapter.

Before we get to that point, we look at how companies first cultivate new growth opportunities. For rough diamonds, growth tends to stem primarily from a strategy of product diversification: entering new, related, or even unrelated businesses and markets in anticipation of the growth potential there. Such successful product diversification strategies not only increase the size of these firms; they also lead to improvements in operational efficiency by more effectively allocating resources across the entire value chain.

Our research revealed three primary factors that influence a firm's sustained performance: the direction, the speed and extent, and the mode of product diversification. Rough diamonds might put different weight on each variable for different decisions, but in one way or another, each of them factors into every product-diversification strategy.

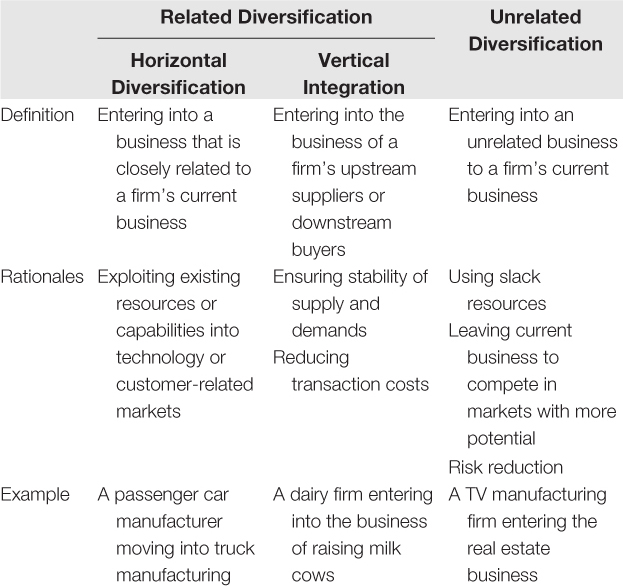

The direction of a product diversification strategy often arises as the first question managers have to answer. These decisions typically break down into one of three categories: horizontal diversification, vertical integration, and diversification into unrelated fields (table 6.1). The direction of diversification is critical because this variable opens up a broad range of both risks and benefits. Moving into an unrelated field or market might test a company's core competencies, while expanding in a similar field can tax a firm's ability to scale its operations.

Table 6.1 Types of Product Diversification

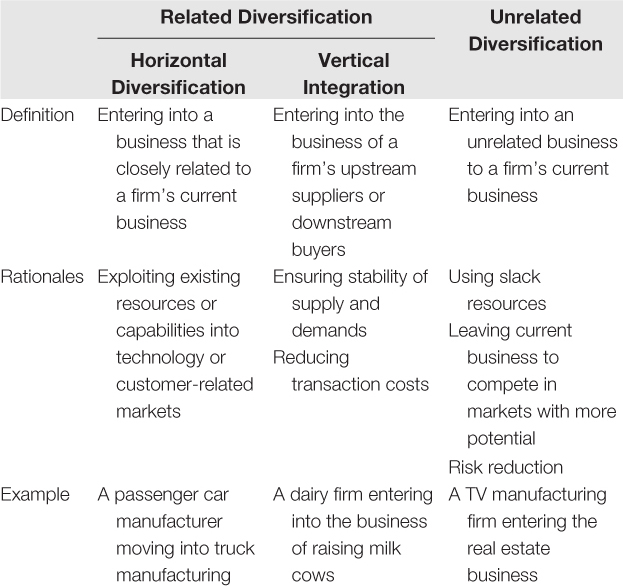

Like many other aspiring firms, rough diamonds must balance the benefits and risks of these moves. After all, the decision to diversify heavily into another business or country can set up a firm for long-term success or send it stumbling into a difficult recovery. It's not the right move for every company. While some rough diamonds have diversified widely and found great success, some of the others have reached their heights by diversifying within their existing fields (table 6.2).

Table 6.2 Product Diversification and Internationalization of Rough Diamonds

In general, we found that the growth management of rough diamonds tends to differ by country. Overall, rough diamonds are actively involved in product diversification. More than 80 percent of these firms diversified into at least one other business, including at least 70 percent of the rough diamonds in each country. Slightly more than half of them diversified into horizontal, related businesses, and 57 percent diversified into vertically integrated businesses. Of the total, 22 percent diversified into unrelated businesses, with more than half of those in China.

Because horizontal-related diversification exploits a firm's existing assets and capabilities, it doesn't require a lot of new resources or capabilities. It's therefore generally considered the easiest and safest strategy among the three. This probably explains the high percentage of firms that have focused on related diversification. However, a closer examination of the data shows that only 42.6 percent diversified firms opted for related diversification as their first move. Instead, 46.3 percent of them chose a vertical integration strategy first, emphasizing the importance that many rough diamonds have put on strategy as a foundation for growth. In all four BRIC countries, more than half of the firms diversified first into vertically integrated businesses, and most of them did so early on.

The relatively underdeveloped market institutions in emerging markets make vertical integration an often necessary early step toward profitable growth. To overcome the lack of regulations that would ensure the sanctity of contracts with outside companies, many successful firms chose to internalize their transactions instead. This also gives a company more control over its inbound and outbound logistics, an especially important issue in countries that lack an established infrastructure. Not only does this allow companies to build scale and extend control across more of the value chain; it allows them to better manage their sales networks and collaborate better with distributors to make sure their products are delivered as promised.

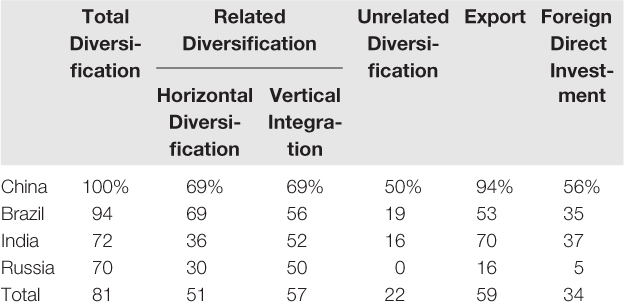

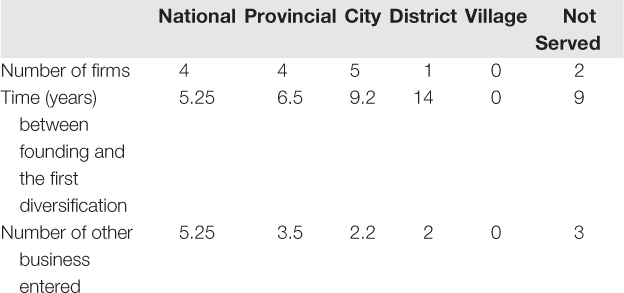

After discerning the direction in which to diversify, companies must ask how far and how fast. The speed and extent to which product diversification takes place has a critical impact on the long-term success of the strategy. Clearly some firms tend to be more aggressive than others (table 6.3). The Chinese rough diamonds diversify faster and further than firms in the other BRIC countries. Rough diamonds in Brazil diversify widely as well, but they tend to deliberate longer before jumping into their first diversification strategy.

Table 6.3 Speed and Extent of Product Diversification for Rough Diamonds

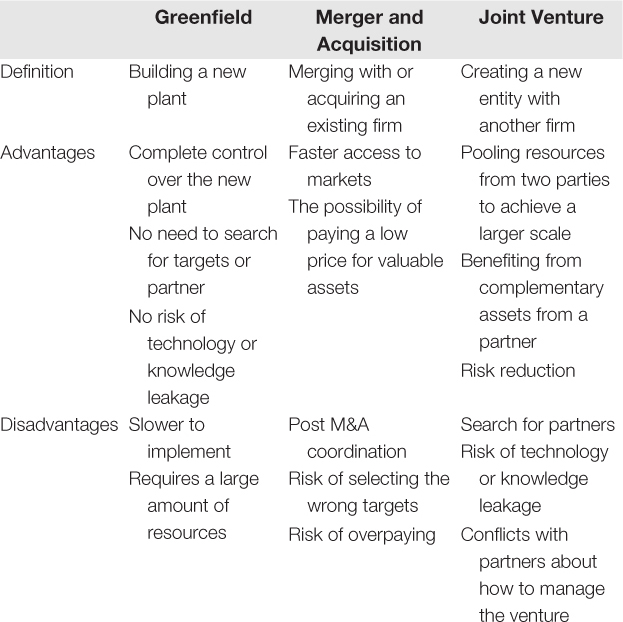

With decisions about the direction, speed, and extent of the diversification strategy in place, companies must then figure out the best mode of diversification to reach those goals. Companies tend to follow three primary modes when they diversify into other businesses: greenfield, merger and acquisition (M&A), or joint venture (table 6.4).1 A greenfield strategy channels investment into something that previously didn't exist, such as an innovative new subsidiary or the construction of new factory, office, or R&D space. In essence, the firm creates a brand-new business from scratch using its own resources and efforts. M&A strategies are what you'd expect: the acquisition or combination of different companies or similar entities. A joint venture is a business agreement in which parties agree to develop, for a finite time, a new entity by contributing equity.

Table 6.4 Modes of Product Diversification

Each of the three modes of diversification has its own benefits and costs. An M&A approach, for example, often proves to be the fastest because a company acquires existing assets and doesn't have to build much, if anything, from scratch. Joint ventures tend to work best for businesses that require large upfront investment because it splits the high costs among multiple parties. Because the selection of diversification mode depends on a firm's own needs, no general rule governs the selection process. Managers need to carefully weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each entry mode. Choosing the wrong one can quickly jeopardize the entire diversification strategy.

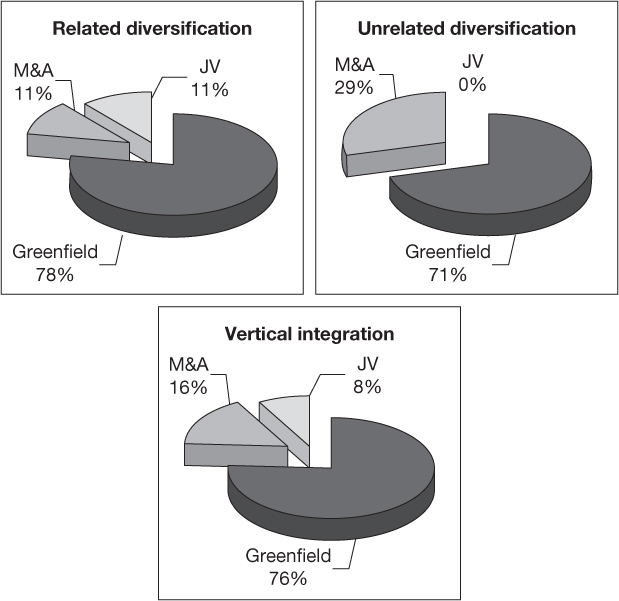

Our research shows that rough diamonds prefer greenfield diversification as the primary mode of entry into a new business, regardless of the type of product diversification they pursue (figure 6.1). This tends to make sense given the low levels of trust and high transaction costs prevalent in emerging markets. Since M&A and joint venture strategies involve an outside party, rough diamonds can reduce their uncertainty by adopting a greenfield mode.

Figure 6.1 Types of Diversification and Entry Modes Adopted by the Rough Diamonds Percentage of RDs That Adopt This Specific Type of Entry Percentage

Rough diamonds are more likely to choose an M&A approach when they're pursuing unrelated diversification, which virtually always takes them into a business they're not familiar with. By acquiring or merging with a known, existing firm in that business, companies can often save the time and effort of developing the new expertise required in that field. In the case of vertical integration, companies are typically purchasing an existing supplier or buyer—a firm with which they have a higher degree of familiarity and trust.

Joint ventures are the least adopted entry mode among the three, due mainly to the difficulty in selecting an appropriate partner for investing with. Our research found that six of the eleven rough diamonds that entered into joint ventures did so with foreign partners. In these cases, the foreign partner was generally well known, had an established reputation, and owned advanced technologies. For example, Lakshmi Machine Works, an Indian textile machinery manufacturer, started to produce computer numerical control machine tools through a partnership and technical collaboration with Mori Seiki of Japan.

Rough diamonds in different countries displayed different trends in diversification modes (table 6.5). Compared with their Russian, Indian, and Brazilian counterparts, Chinese rough diamonds tend to be more active in establishing joint ventures when pursuing related diversification and vertical integration strategies. Most of them partnered with foreign companies, reflecting the broader Chinese intention to access advanced technologies and bring them to the domestic marketplace. Although Chinese firms take this aggressive approach to product diversification, they rarely select the fastest mode of entry: M&A. We attribute this to several factors. First, the lack of trust and information forces Chinese rough diamonds to take a more cautious approach to outside firms. Second, they lack appropriate, available, and suitable targets. Many of the available targets are bankrupt state-owned enterprises, and most Chinese business leaders believe that private firms will have difficulty integrating a formerly state-owned business. And third, given the abundant labor and other raw materials in China, greenfield investments can get up to speed faster than in many other countries.

Table 6.5 Entry Modes of Product Diversification for Rough Diamonds

Brazilian rough diamonds tend to adopt an M&A approach more than their counterparts from other countries. Because Brazil has a longer market-based history than other countries, the domestic market is mature and saturated, making many existing firms credible candidates for merger or acquisition.

Despite the fact that Russia, like China, experienced remarkable economic liberalization during the 1990s, Russian companies did not enjoy the same abundant opportunities that Chinese companies had. During the posttransition period from planned economy during 1980s and 1990s in China, privatization led to intense market competition in most sectors. The same level of competition did not occur in Russia, which also suffered from weaker market institutions and a lower level of trust. Because of those factors, the Russian rough diamonds immediately focused on enhancing and solidifying their market positions in their existing markets and areas. Not surprisingly, none of the Russian firms on our list diversified into unrelated businesses.

The external environment has a major influence on how companies select the direction, speed, extent, and mode of their diversification strategies. Different BRIC countries spawn distinctive growth paths and competencies. To be sure, rough diamonds excel at management through transitions no matter the external environment (box 6.1). But part of their success stems from their ability to understand the business environment around them and adopt strategies that account for the environment in which they're operating.

Chinese firms are the most actively diversified in terms of both products and geography. Because many industries in China were not well developed in earlier years, they were not saturated with competitors. As long as these firms can enter these industries, they can become first movers and benefit from such advantages. But not all firms have the capacity to enter these markets efficiently. Companies might see these open opportunities and move quickly to capitalize on them, but sustained success requires the right skills and resources. Still, with so many underserved, potentially huge markets in China, most of the rough diamonds in our study would have the requisite skills to diversify successfully into both related and unrelated businesses quickly.

Chinese rough diamonds also tend to participate in international expansion at earlier stages of development. Participating in global competition not only provides them with an important avenue through which to achieve sustainable growth; it also equips them with invaluable knowledge on how to adapt to local environments and operate successfully in foreign countries. Most of these firms started exporting their products within the first decade after their founding, primarily due to the low cost of expansion and their increasing technological competence (box 6.2).

In a landmark study published in 1962, Strategy and Structure, economic historian Alfred P. Chandler studied the growth and evolution of America's seventy largest enterprises. Among his conclusions, which spurred a flurry of follow-up research and similar studies across several continents, Chandler argued that these firms followed a staged progression of growth that's based on their efficiency. Firms adopted strategies and structures that reflected incremental changes, from expansion, to vertical integration, to related and unrelated diversification.

Chandler's conclusions prompted later scholars, notably Jay Galbraith and Daniel Nathanson, to formulate a congruence hypothesis, in which the performance of a firm would depend on the extent to which its structures and efficiencies were aligned with its strategies. In our study of rough diamonds, we confirmed a similar pattern of gradual diversification (although Chinese firms were more aggressive than their peers in other BRIC countries). Even so, some nuanced differences reflect the evolving institutional landscape of emerging markets:

Sources: Alfred P. Chandler, Strategy and Structure (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962); Jay Galbraith and Daniel Nathanson, Strategy Implementation: The Role of Structure and Process (St. Paul, MN: West, 1978).

The Xiwang Group, a Chinese leader in starch and starch-related products, is a good example of broad diversification. Located in Xiwang Village in Shandong Province in northeast of China, it started from the corn processing industry and gradually diversified into related and unrelated businesses. It purchased a technology that processed sugar from cornstarch into glycerol, a soapy sweet fluid. Following a market slump, it also found ways to process that glycerol into the production of glutamate, a type of salt from glutamic acid. Vertically, it expanded further into logistics and heat power. Horizontally, it expanded again, moving into industries such as beverages and biochemical products. And it moved into unrelated industries, including real estate, steel, and investment. All the while, it began its move outside the Chinese market by exporting to Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. The company eventually started its own import and export trading company, with subsidiaries in Hong Kong and South Korea.

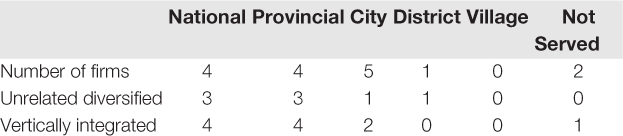

Chinese firms also display a unique ability to leverage their relationships when developing and implementing their marketing and operational strategies. Because relationships are not bounded by industry, Chinese rough diamonds relentlessly use those connections to support their push into unrelated diversification paths. We found that the level to which CEOs rise in the People's Congress, or China's highest legislative body, can serve as a close proxy for the depth and breadth of their relationships. Generally the higher the rise in the People's Congress, the more connected the person is. CEOs who are elected as deputies to the People's Congress are widely seen as especially well-connected businesspeople whose firms could be better suited for diversification strategies (tables 6.6 and 6.7).

Table 6.6 CEOs as Deputies in the People's Congress, by Type of Diversification

Table 6.7 Number of CEOs as Deputies in the People's Congress, by Diversification Time and Other Businesses Entered

As tables 6.6 and 6.7 show, firms that undertake unrelated diversification and vertical integration strategies typically have CEOs who serve as deputies to the national or provincial levels of the People's Congress. Similar patterns can be found in vertical integration. The firms led by these higher-level, connected CEOs take less time before moving into their first diversification, and they tend to enter more different businesses. Although certainly this is not a causal association, this preliminary analysis suggests a fairly strong correlation between greater relational capital and more aggressive diversification patterns.2

Brazil's rough diamonds rank second in terms of diversification. Because most of these firms have long histories and strong brand legacies, they can better establish their advantage in new markets, including in other countries. Thus, a high percentage of Brazilian firms invest in unrelated businesses. Although these firms diversify extensively, they do not rush into these strategies as quickly as their counterparts in China do. Instead, they adopt a gradual diversification strategy that usually starts with related diversification before moving into unrelated businesses. This incremental approach mitigates the risks that come with rapid expansion and allows them to deliberately build on their already established legacies.

Screw manufacturer Ciser exemplifies this gradual approach to diversification. In the years after its 1959 launch, Ciser's product portfolio consisted of furniture, electronic hardware, and civil construction. In 1967, it extended its business to screws and nuts for civil construction, railroads, and metal mechanics. In the 1970s, it expanded its product range further. And in 1978, it opened a sales office and a distribution center in São Paulo, which gave it a strong market position for standardized screws and nuts in Brazil.

Only then did the company start to seriously consider other expansion possibilities. Since 1980, it has been aggressively pursuing the transportation business sector, which has the added advantage of providing transportation for a wide range of its products and components. And after vertically integrating its entire value chain, the firm put the lessons it learned to work in new territories. In 1981, it acquired 166 hectares of land in Araquari, in the northern region of Santa Catarina, to breed wild boars, buffalo, and cattle. In 1984, the company managed and sold land, houses, apartments, and areas for commercial, industrial, and agricultural use. It started exporting in 1972 and now sells products in more than twenty countries around the world, including China, the United States, Japan, and Canada. The company's sustained growth reflects the critical balance it has struck between adequate control (vertical integration) and market opportunities (unrelated businesses).

Russian companies did not enjoy the same abundant opportunities that opened up in China during the posttransition period, when privatization led to intense market competition in most industry sectors. Moreover, the weak institutions and the generally low level of trust in Russian society hindered the growth and success of many entrepreneurial Russian firms. The combination forced most firms to focus locally, so they could capture, solidify, and enhance their positions in their own markets and industries. As a result, none of the Russian rough diamonds conducted diversification in unrelated businesses, and even now, only a few of them have exported or pursued foreign direct investment.

Most of the Russian rough diamonds were born, or reborn, as private firms in the mid- to late 1990s, when their markets were competitive, fragmented, and embryonic. Their first phase of growth centered on building competitiveness in the domestic market, mostly through strategies to increase operational scale, achieve cost advantages, or establish brand saturation across different market segments that would allow them to establish pricing advantages. One example is NEP LL, the market leader in tea and coffee production, which scaled up and gained cost and price advantages over its competitors. Its separation from the rest of the pack began between 1999 and 2001, when Leningrad's regional government helped the company expand its tea production volume from 14,400 tons to 30,000 tons, all while doubling its coffee capacity as well.

Velkom, the producer of several hundred different food products, pursued a complex, within-product diversification that adjusted brands and prices for a wide range of quality and income levels within each product category. In this process, the company learned what worked and what didn't at each phase of its expansion. Other rough diamonds increased their visibility and competitiveness by tapping into the resources of a larger conglomerate. These large group companies offer instant access to the logistical services, market intelligence, management skills, and capital possessed by the group as a whole, a coveted asset when pursuing broad cost or differentiation strategies (box 6.3 ).

Russia's rough diamonds pursued regional and product diversification only after securing their competitive advantage in established market niches. Again, unlike the Chinese entrepreneurs that aggressively moved into unrelated areas for new applications and better opportunities, these Russian firms continued to stay within their own familiar areas of expertise when expanding into new markets and regions. For example, Mordovtsement engaged in a focused geographical expansion even as market competition intensified. Throughout the frenzy of privatization, it expanded at a measured pace, opening thirty-one new regional subsidiaries since 1992 in order to stay closer to its core customers.

In short, while Chinese and Brazilian rough diamonds pursued aggressive globalization and diversification into unrelated product areas, their counterparts in Russia remained more conservative and focused on local markets and product categories. In our view, weak formal institutions and lack of trust explain the higher dependence on this greenfield strategy. Even so, this gradual process of internationalization should not be interpreted as exhibiting weak management. The record established by these Russian rough diamonds obviously proves otherwise. Their disciplined management approach merely focuses on related-diversification strategies, reflecting their quest for synergy and organic growth instead of risky international business opportunities.

Alfred Chandler argued in his authoritative study of organizational structure that companies had to design their business in a manner that supports the requirements of its growth strategy. This, of course, is much easier said than done, but MLVZ's decisions reflected the deliberate and purposeful choices that Chandler outlined. “Besides our own unique strengths, we obtained strong brands, powerful support of the company's central apparatus and unique opportunities of intra-corporate interaction with other members of the Synergiya Group,” said Prokhorov Konstantin Anatolevich, the firm's general director. “It is obvious that all mentioned instruments of related diversification are realized in the complex holding structure of ‘Synergiya’ company. In such a way, using related diversification, we remain in our market segment and try to strengthen in it.”

Although the internationalization strategies adopted by Russia's rough diamonds were limited in terms of geographical coverage and the extent of their operations, several of them did venture into other Commonwealth of Independent States countries. But most of them, including MLVZ, took gradual steps down this path. MLVZ limited itself to exporting for a while, but with that in place, it moved beyond its comfort zone to pursue what became a richly successful cross-marketing alliance with an international firm, William Grant & Sons, one of the top scotch whisky producers. “We have achieved internationalization as Beluga is sold all over the world,” Prokhorov said. “A significant step to internationalization was forming the alliance with a world leader in the alcohol business, William Grant & Sons. While we cross-market each other's products, we were able to enhance the portfolio of our brands domestically. Whisky is a growing sector in Russia, and it does not compete with vodka. In a word, in everything we do, we try to achieve a synergistic effect to justify and strengthen our brand.”

Much like their Russian counterparts, Indian rough diamonds followed carefully managed diversification plans. Instead of pursuing broad diversification, they chose to remain focused and sought growth by enhancing and solidifying the market positions they had built in their domestic markets. Nevertheless, Indian rough diamonds clearly are more active in some internationalization activities, such as exporting. Moreover, they have maintained a strategy to explore foreign markets with their low-cost products (box 6.4).

Bombay Rayon Fashions, established by Janardhan Agrawal in 1986, started by manufacturing woven fabric in Maharashtra. In 1998, the firm opened another manufacturing facility for woven fabric and began to export its products. In 2001, it became vertically integrated by starting a garment business and in 2003 started exporting garment products. Two years later, it was publicly listed on all the stock exchanges in India.

Bombay Rayon Fashions eventually expanded its manufacturing capacity with seven garment manufacturing facilities in Bangalore that housed seventy thousand machines. It also acquired U.K.-based DPJ Clothing and started supplying garments to high-end retailers in the United Kingdom. In 2007, it acquired Leela Scottish Lace, one of the largest garment-manufacturing firms in India, and LNJ Apparel, making it one of the largest apparel firms in India. The firm added the iconic brand Guru the following year.

Most of India's rough diamonds follow a narrow growth path. They do not expand heavily into other businesses, preferring to stay focused on their primary product markets. They increase capacity and reach market leadership by setting up new facilities or acquiring existing plants. However, their internationalization activities tend to start relatively early in their development. But even here, they take a fairly deliberate approach. They begin by exporting their products, due to the low cost advantage, and only after gaining exporting experience do they begin more radical internationalization through foreign direct investment. They eventually become true global players by acquiring foreign firms.

Perhaps as much in India as in any of the other BRIC countries, the nature of technology also helps determine the path of diversification, whether in related or unrelated businesses. For example, Tata Metaliks pioneered the production of high-quality pig iron, a niche market product at the time. Since then it has moved into a related business, ductile iron pipes, and gradually expanded its presence in foreign markets. Tata Metaliks made a conscious effort not to enter any unrelated businesses or engage in vertical integration that could damage its technological advantage.

What's clear is that Tata Metaliks and the other rough diamonds in all the BRIC countries capitalized on diversification plans that suited both their internal operations and the markets they pursued. While firms in different countries adopted different approaches, all of them capitalized on the advantages afforded them without being burdened by unnecessary risk. Their success at leveraging advantage is reflected in market positions around the world.

When looking across all the Four Cs for sustaining high performance, we can see that the rough diamonds took a similar overarching strategy and adapted it to pave their various paths to success. However, their mastery of marketing, operations, and management systems differs from firms in developed countries and even from many of the large, incumbent firms in their own countries. Admittedly, a number of external factors, such as changed governmental regulations and market liberalization, arrived with serendipitous timing. But rough diamonds took advantage of and capitalized on those opportunities, and they have sustained that success.

1 For a detailed discussion, see Joseph Boyett and Jimmie Boyett, The Guru Guide to the Knowledge Economy: The Best Ideas for Operating Profitably in a Hyper-Competitive World (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2006), 105–106.

2 No causal association is claimed not only because the test itself is not designed to show causality, but because other intervening factors need to be considered. An alternative explanation is that the decisions about diversification tend to be broad and strategic in nature and should be conducted at the highest level of governmental and provincial bureaucracy instead of at the city or village levels.