3

When a son of the Shakya clan (known later as the “golden sage”) went into the fastness of the Snowy Mountains long ago to begin his first retreat, he cradled secretly in his arms an ancient, stringless lute.1 He strummed it with blind devotion for over six years until, one morning, he saw a beam of light shining down from a bad star, and was startled out of his senses.2 The lute, strings and all, shattered into a million pieces. Presently, strange sounds began to issue from the surrounding heavens. Marvelous tones rose from the bowels of the earth. From that moment, he found that whenever he so much as moved a finger, sounds came forth that wrought successions of wondrous events, enlightening living beings of every kind.3

It began in the Deer Park, where he strummed an old four-strutted instrument from which issued twelve elegant tones. In midcareer, at Vulture Peak, he articulated the perfectly rounded notes of the One Vehicle. At the end, he entered the Grove of Cranes, and from there the sad strains of his final song were heard.4 His repertoire reached a total of five thousand and forty scrolls of marvelously wrought music.

A person appeared who understood. He could grasp these notes at the touch of a single string. He was known as Great Turtle. When his carapace fractured—a sudden blossom-burst of cracks and fissures—the melody was taken up on the strings of twenty-eight mighty instruments. The last of them was a divine, blue-eyed virtuoso with a purple beard. How wonderful he was! With one sweep of the lion strings he swallowed up the voices of all the six schools. Eight times the phoenix strings sang out; eight times the divine lute passed in secret transmission. The source of it all was this man from the land of Kōshi, in south India, who was born the son of a king.5

When he reached the forested peaks of the Bear’s Ears, he amused himself playing on a holeless iron flute. The sounds were magnificent, but he found they were unable to rend people to their deepest souls, so he parceled out his own skin, flesh, bone, and marrow instead.6

Seven steps after him, the transmission stumbled, and a blind lifeless old nag was loosed upon the world.7 He reared up on his hind legs, pawing the air in high spirits. With his three hundred and sixty joints lathered up, throwing deadly milk wildly in all directions and showers of blood and sweat steaming violently up through his eighty-four thousand pores, he stomped the trichilocosmic universe into dust, he smashed the vaults of heaven into atoms with deafening neighs, striking such panic into millions of Mount Sumerus they toppled over each other trying to escape, and he ravaged every land in the six directions, leaving them strewn behind in tiny pieces.

These sounds carried to the foot of Mount Nan-ch’üan, where a divine celestial drum took up the beat of its own accord. Ch’ang-sha and Chao-chou fell into harmony with the mysterious direct pointing and broke into powerful personal renditions of the secret melody. It reached an old ferryman at the Ta-i Ford, who liked to pass the time tapping away on the sides of his boat. He rapped out rough, barbaric tunes that drowned out the notes of more graceful singers.8

Old Elephant Bones sustained the resonance with his wild dances and uncouth ways. At Mount Lo and Mount Su the old tunes, infused with the divine, flowed out in elegant numbers that were regulated perfectly to the Dharma truth. Shou-shan and Tz’u-ming pitched their melodies to the tones of “yellow bell” and “great harmony,” making music that was soft and subtle, yet so stern and unyielding it set country demons scuttling in horror and idle spirits scurrying into hiding.9

The sternest, most trenchant notes that came from the holeless flute reached the abbot’s chambers at the Kuang-t’ai-yüan in Kuang-nan province, where a poison drum was slung upside down. From that drum emerged sounds that drained men’s souls and burst men’s livers, littering the landscape with the bodies of over eighty men, and striking who knows how many others deaf and mute.10

Hsiao-ts’ung restrung the lute and carried it up into the fastnesses of Mount Tung. Ch’ung-hsien clasped it to his bosom and entered Mount Hsüeh-tou.11 From these pinnacles emanated sounds that shook the whole world.

Roarings of an iron lion were heard over the lands west of the river—they would have killed the spirit in a wooden man. Bayings of a straw dog filled the skies over Lake Tzu—they would have started hard sweat on the flanks of a clay ox.12

Another true man emerged. He was a son of the Teung family of Pa-hsi in Mien-chou. Known as Tung-shan Lao-jen, the Old Man of the Eastern Mountain, he devoted himself as a young monk to austere religious discipline at Brokenhead Peak. Later, he concealed his presence inside a clump of white cloud. One morning, he entered a rice-hulling shed, tucked up his hemp robe, and made a single circumambulation of the millstone. The thunder from this voiceless cloth drum rolled angrily out, snarling and snapping, and filled the world with far-reaching reverberations. You would have thought the thunder god himself had been hired to pound a poison drum. It rendered three Buddhas utterly senseless, and it drained all the courage from a quiet man.13

Ta-hui chanted—his voice reached up and down the coasts of Heng-yang. Wu-chun roared—the reports pierced the bottom of the Dragon Pool. Long howls emanating from Hu-ch’iu, Tiger Hill, shook whole forests to their roots. Bitter, soul-rending cries from a Yellow Dragon checked sailing clouds in their tracks.14

Ying-an, Mi-an, Sung-yüan, and Yün-an beat time in conformity to the age-old rhythms with a finesse that placed them head and shoulders above their contemporaries.15

An old farmer in Ssu-ming, who called himself Hsi-keng, Resting Farmer, kept up a constant stream of song as he swung his iron mattock. One day, when he saw an ancient column of light emanate from a large peak and illuminate a memorial tower, the marvelous principle entered his fingertips, inspiring them to move across the strings. The sounds produced shook two forests to their roots, and swept through ten temples.16

Shakyamuni Leaving the Mountains

“Zen practice pursued within activity is a million times superior to that pursued within tranquillity.”

Zen Master Lin-chi

Zen Master Hsi-keng (Sokkō)

Hakuin as Hotei, Doing Zazen

Dragon Staff. Hakuin gave paintings of these Dragon Staffs to people to certify that they had passed his One Hand koan.

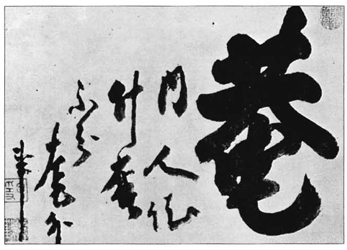

“Mu”

“If you are not there for even an instant, you are just like a dead person.”

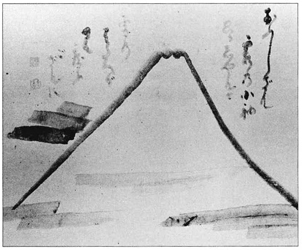

Mt. Fuji from Shoin-ji Temple

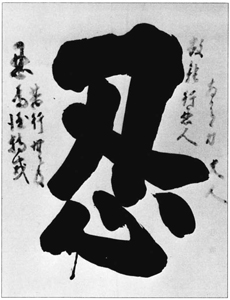

“Perseverance”

Echoes from these sounds, floating eastward, landed in Japan. They startled the golden cock, who clapped his wings and announced the coming dawn, while a jade tortoise sobbed out the sorrows of his heart.17 They brought fine spring warmth to Recumbent Mountain, they danced white flakes of snow over Purple Fields, they sent an auspicious herd of deer darting by so swiftly they made lightning seem slow, and made a bright pearl turn in emptiness with a brilliance that threw the surrounding world into total darkness.18

From there, the music wafted into the flower fields of Hanazono. Eight sounds rang out in succession, striking everyone who heard them speechless—they worked like the great poison-lacquered crocodile drum that destroys all within earshot. Branching out, it formed into four main pillars at Myōshin-ji—large instruments that yielded slow, resonant tones, and smaller ones that played with a quicker and more animated beat.19 Together, their voices rolled throughout the universe, penetrated far beyond the seas.

How sad to see music of such great purity and elegance forgotten, its place taken by these obscene noises pouring forth unchecked. Time-honored classics have been drowned out by the discord these vulgar, degenerate songs produce.

Look at the extraordinary caliber of the patriarchal teachers we have surveyed. How many people today bear any resemblance to them? Most of them have yet to pass through the barrier-koans raised by these illustrious teachers, so the essential core of truth contained in them remains unpenetrated, and the fire still burns restlessly in their minds. They won’t have a moment’s peace as long as they live. They are like someone who suffers at daily intervals from chronic fever. They try to meditate for five days or so, then they give it up and begin prostrating themselves in front of Buddhist images. Five days later, they give that up too, and start chanting sutras. They keep that up for five days or so, and then switch to a dietary regimen, one meal a day. They are like someone confined to bed with a serious illness who can’t sleep and tries to sit up, only to find he is unable to do that either. They stumble ahead like blind mules, not knowing where their feet are taking them. And all because they were careless at the start of their training and were never able to achieve a breakthrough of intense joy and fulfillment.

It frequently happens that someone will take up Zen and spend three, five, perhaps seven years doing zazen, but because he does not apply himself with total devotion he fails to achieve true single-mindedness, and his practice does not bear fruit. The months and years pass, but he never experiences the joy of nirvana, and samsaric retribution is always there waiting if he stops or regresses. At that point, he turns to the calling of Amida’s name and goes all he knows for the nembutsu, eagerly desirous of being reborn in the Pure Land, abandoning his erstwhile resolve to negotiate the Way and to bore his way through to the truth. In China, people of such pedigree began to emerge in great numbers beginning in the Sung dynasty; they continued to appear up through the Ming and on into the present day. They have most of them been of mediocre caliber, weak, limpspirited Zennists.

Anxious to cover up their own failure and lessen their sense of shame, they are quick to cite the rebirth in the Pure Land of Zen priests such as Chieh of Mount Wu-tsu, Hsin-ju Che, and I of Tuanya, and from their examples draw the conclusion that practicing zazen is ineffective.20 What they don’t seem to know is that those men were primarily followers of the nembutsu from the start. Alas! in their eagerness to gain support for their own preconceived and commonplace notions, they rustle up a broken-down reincarnated old warhorse or two whose dedication to Zen practice was weak to begin with, who hadn’t gained even a glimpse of the discernment that comes with kenshō, and they attempt to throw into disrepute the wise saints who have forged the actual living links in the Dharma transmission. They thus pervert the secret, untransmittable essence that these saints have personally transmitted from Dharma father to Dharma son. The gravity of their offenses exceeds that of the five deadly sins. There is no possible way for them to repent.

Basically, there is no Pure Land existing apart from Zen; there is no mind or Buddha separate from Zen. The Sixth Patriarch Huineng manifested himself as a teacher of men for eighty successive lives.21 The venerable master Nan-yüeh was an embodiment of all three worlds—past, present, and future. They were great oceans of infinite calm and tranquillity, great empty skies where no trace remains, within which there is human rebirth, birth in the Pure Land divine birth—and also the unborn. The joyful realm of paradise, the terrifying hells, the impure world, and the Pure Land are facets manifested by a wish-fulfilling mani gem moving freely and easily on a tray. If even the slightest thought to grasp something appears, you become like the foolish man who tried to catch a dragon by scooping up water from a riverbank.

If the First Patriarch, Bodhidharma, had thought the Buddhadharma’s ultimate principle was the aspiration for rebirth in the Pure Land, he could have simply sent a letter to China, one or two lines, telling everyone: “Attain rebirth in the Pure Land by devoting yourselves single-mindedly to repeating the nembutsu.” What need would there have been for him to cross ten thousand miles of perilous ocean, enduring all the hardships he did, in order to transmit the Dharma of seeing into self-nature [kenshō]?

Aren’t the people who think the Pure Land exists apart from Zen aware of the passage in The Meditation Sutra that declares the body of Amida Buddha to be as tall as “ten quadrillion miles multiplied by the number of sand particles in sixty Ganges rivers”?22 They should reflect on that passage. Give it careful scrutiny. If this meditation on the buddha-body is not the way of supreme enlightenment, of enlightening the mind by seeing into your self-nature, then what is it?

The Pure Land patriarch Eshin Sōzu said, “If your faith is great, you will see a great buddha.” Zen practice has you break through so you encounter that venerable old buddha face to face and see him with perfect clarity. When you try to find him somewhere else apart from your self, you join the ranks of the evil demons who work to destroy the Dharma. Hence the Buddha says in The Diamond Sutra: “If you see your self as a form or appearance, or seek your self in the voice you hear, you are on the wrong path, and will never be able to see the Buddha.”

All tathagatas, or buddhas, are possessed of three bodies: the Dharma-body, Birushana, which is said to be “present in all places”; the Recompense-body, Rushana, which is called “pure and perfect”; and the Transformation-body, Shakyamuni, described as “great perseverance through tranquillity and silence.” In sentient beings the three appear as tranquillity, wisdom, and unimpeded activity. Tranquillity corresponds to the Dharma-body, wisdom to the Recompense-body, activity to the Transformation-body.23

The great teacher Bodhidharma said,

If a sentient being constantly works to cultivate good karmic roots, the Transformation-body buddha will manifest itself. If he cultivates wisdom, the Recompense-body buddha will manifest itself. If he cultivates nonactivity, the Dharma-body buddha will manifest itself. In the Transformation-body the buddha soars throughout the ten directions, accommodating himself freely to circumstances as he liberates sentient beings. In the Recompense-body the buddha entered the Snowy Mountains, eliminated evil, cultivated good, and attained the Way. In the Dharma-body, the buddha remains tranquil and unchanging, without words or preaching.

Speaking from the standpoint of the ultimate principle, not even one buddha exists, much less three. The idea of three buddhabodies only came into being as a response to differences in people’s intellectual capacities. People of inferior intellectual capacity, who mistakenly strive to gain benefit from performing good deeds, mistakenly see the buddha of the Transformation-body. Those of mediocre capacity, who mistakenly attempt to cut off their evil passions, mistakenly see the buddha of the Recompense-body. Those of higher intelligence, who mistakenly strive to realize enlightenment, mistakenly see the buddha of the Dharma-body. People of the highest intelligence, however, who illuminate themselves within, attain the perfect tranquillity of the enlightened mind, and are, as such, buddhas. Their buddhahood is attained without recourse to the workings of mind.

Know from this that the three buddha-bodies, and all the myriad phenomena as well, can none of them be either grasped or expounded.

Isn’t this what the sutra means when it states that “buddhas do not preach the Dharma, do not save sentient beings, do not realize enlightenment?”24

The great teacher Huang-po said,

The Dharma preaching of the Dharma-body cannot be found in words, sounds, forms, or appearances; it cannot be understood by means of written words. It is not something you can preach; it is not something you can realize. It is self-nature and self-nature alone, absolutely empty, and open to all things. Hence The Diamond Sutra says, “There is no Dharma to preach. The preaching of that unpreachable Dharma is what is called preaching the Dharma.” Although buddhas manifest themselves in both the Recompense-body and Transformation-body to expound the Dharma in response to various conditions, that is not the true Dharma. Indeed, as a commentary says, “Neither the Recompense- nor Transformation-body is the true buddha, nor is what they preach the true Dharma.”25

What you must realize is this: although buddhas appear in response to sentient beings in a limitless variety of sizes and shapes, large and small, they never appear except as these three buddha-bodies. In The Sutra of the Victorious Kings of Golden Light, we find the words, “In this way you attain supreme enlightenment possessed of the three buddha-bodies. Among the three, Recompense-body and Transformation-body describe provisional modes of existence. The Dharma-body alone is true and real, constant and unchanging, the fundamental source of the other two.”26

Hence The Meditation Sutra’s preaching is perfectly clear: “The height of the buddha’s body is ten quadrillion miles multiplied by the number of sand particles in sixty Ganges rivers.” Can someone tell me: Is this colossal body a Recompense-body? Is it a Transformation-body? Or is it a Dharma-body? We saw before that the Recompense- and Transformation-bodies appear to benefit sentient beings in response to their various capacities. Yet how large would a world have to be to accommodate such a buddha? Can you imagine the gigantic size of the sentient beings to whom he would appear? And don’t say that because sentient beings in a Pure Land of such size would be correspondingly large, a buddha would have to manifest himself in a large form too. If that were true, wouldn’t bodhisattvas, religious seekers, and everyone else who inhabited such a world have to be of similar size as well: “ten quadrillion miles multiplied by the number of sand particles in sixty Ganges rivers”?

A river the size of the Ganges measures forty leagues across; its sands are as fine as the smallest atoms. Not even a god or demon could count the sand in a single Ganges river, or in half a Ganges river—or even, for that matter, the sand in an area ten feet square. And we are talking about the sand in sixty Ganges! The all-seeing eyes of the Buddha himself could not count them. These, in essence, are numbers that cannot be reckoned, calculations beyond calculating. Yet they contain a profound truth which is among the most difficult to grasp of all those in the Buddha’s sutras. It is the golden bone and golden marrow of the Venerable Buddha of Boundless Life.

If I had to say anything about it at all, it would be that the sand in those sixty Ganges rivers alludes to the colors and forms, the sounds, and the rest of the six dusts that appear as objects to the six organs of sense.27 Not one of all the myriad dharmas exists apart from these six dusts. When you fully awaken to the fact that all the dharmas perceived in this way as the six dusts are, in and of themselves, the golden body of the Buddha of Boundless Life in its entirety, you transcend the realm of samsaric suffering right where you stand and become one with supreme perfect enlightenment.

At that moment, everywhere, both east and west alike, is the Land of the Lotus Paradise. The entire universe in all directions, not a pinpoint of earth excepted, is none other than the great primordial peace and tranquillity of Birushana Buddha’s Dharma-body. It pervades all individual entities, erasing all their differences, and this continues forever without change.

The Meditation Sutra goes on to say that those who recite the Mahayana sutras belong to the highest class of the highest rank of those who are reborn directly into the Pure Land of Amida, the Buddha of Boundless Life. What is a “Mahayana” sutra? Well, it’s not one of those scrolls of yellow paper with the red handles. No, there’s no doubt about it, it indicates the buddha-mind that is originally furnished in your own home.

What possible basis could there then be for that foolish talk about Zen practice being ineffective?

In saying these things I am not referring to those wise saints, motivated by the working of the universal vow of great compassion, who wish to extend the benefits of salvation to people of lesser capabilities. They engage in Pure Land practices themselves in order that they may instill a firm desire for Pure Land rebirth in their followers and enable them to acquire a mastery of the triple mind and fourfold practice.28

I refer rather to people of the Zen school who, being incapable of devoting themselves single-mindedly to Zen practice, neglect their training and then go around telling others that Zen practice is useless, that you get no results if you devote yourself solely to Zen. A person like that cannot be allowed to escape without undergoing scrutiny of the severest kind. He is like a Chinese scholar who is passed over for government appointment because he fails the imperial examination. Reduced to an ignoble existence, drifting around the country and living on others, he points to the examples of a few government officials who have been dismissed and banished to the provinces as proof of the uncertainty and precariousness of government service. He is himself a failure, yet he insists upon belittling others of genuine worth who have passed the examinations with highest honors. He reminds you of someone who doesn’t have the strength to raise his food up to his mouth to eat, yet who insists he isn’t eating because the food is bad.

Adding Pure Land to Zen, someone said, is like fixing a tiger with wings.29 What empty-headed piffle! Zen! Zen! Anyone who would say something like that could never understand Zen, not in his wildest dreams. Why, if you show wise ones of the three ranks or four ranks the slightest glimpse of its working, they topple over in deep shock, their hearts and their livers sapped of spirit. Even saints who have gone beyond them to higher levels of attainment lose all their nerve. The buddha-patriarchs themselves plead for their lives. Zen is not something that has to appropriate expedient teachings like these from other schools to provide for its future generations.

I recently heard about an old clam who has burrowed himself into a riverbank in Naniwa.30 There he slumbers away in a thousand-year sleep, missing any chance he might have to encounter a tathagata when one appears in the world. Somehow, however, these words reached his sleeping ears. He raised himself up in a sleepy huff, sprayed out ten thousand bushels of venomous poison foam, opened his jaws wide, and said, “Adding Pure Land to Zen is like depriving a cat of its eyes. Adding Zen to Pure Land is like raising a sail on the back of a cow.”31 The ravings of a sleep-drunk man? Yet even so, such marvelous ravings they are!

Twenty years ago, a man said that in two or three hundred years all Zennists will have joined the Pure Land schools.32 My answer is, “If a follower of Zen does not devote himself single-mindedly to his practice, he will indeed gravitate to the Pure Land teaching. If a follower of the Pure Land does the nembutsu single-mindedly and is able to achieve samadhi, he will inevitably wind up in Zen.”

I was once told this story by a great and worthy person:33 There were, thirty or forty years ago, two holy men. One was named Enjo and the other Engū. It’s not known where Engū was from or what his family name was, but he devoted himself constantly and singlemindedly to the calling of Amida’s name—he kept at it as relentlessly as he would have swept at a fire on top of his head. One day, he suddenly entered samadhi and realized complete and perfect emancipation. His attainment radiated from his entire being. He immediately set out for Hatsuyama in Tōtōmi province to see old master Tu-chan.34 When he arrived, Tu-chan asked him, “Where are you from?”

“From Yamashiro,” Engū replied. “What Buddhism do you practice?” asked Tu-chan. “I’m a Pure Land Buddhist,” he said. “How old is the revered Buddha of Boundless Life?” “He’s about my age,” said Engū. “Where is he right now?” asked Tu-chan.

Engū made his right hand into a fist and raised it slightly. “You are a true man of the Pure Land,” said Tu-chan.

This substantiates what I just said about Pure Land followers gravitating inevitably to Zen if they can attain a state of samadhi by repeating nembutsu single-mindedly. Unfortunately, Pure Land followers who turn to Zen are harder to find than stars in the midday sky. While followers of Zen who avail themselves of Pure Land practices are more numerous than the stars on a clear night.

Recently someone told me about people who are holding nembutsu meetings in remote Zen temples in the country. It seems they set up gongs and bronze drums like the ones they have in the Pure Land temples, and beat on them as they wail out loud choruses of nembutsu. They raise such a terrible din they startle the surrounding villages.

It terrifies me to think of that prediction about Zen three hundred years from now. Barring the appearance of some great Zen saint like Ma-tsu or Lin-chi, the situation seems to be beyond remedy. It gives my liver the willies every time I think about it.

So, loyal and valiant patricians of the secret Zen depths, gird the loins of your spirits. Make piles of brushwood your beds! Make adversity your daily ration!

In the third section of The Platform Sutra, the one devoted to doubts and questions, the Sixth Patriarch makes the statement, “Considered as a manifestation in form, the Paradise in the West lies one hundred and eight thousand leagues from here, a distance created by the ten evils and eight false practices in ourselves.”35

Yün-ch’i Chu-hung, a Ming-dynasty priest of recent times who lived in Hang-chou during the Wan-li period (1573–1627), wrote in his commentary on The Amida Sutra:36

The Platform Sutra mistakenly identifies India with the Pure Land of Bliss. India and China are both part of this defiled world in which we live. If India were the Pure Land, what need would there be for people to aspire toward the eastern quarter or yearn toward the west? Amida’s Pure Land of Bliss lies west of here, many millions of buddha-lands distant from this world.37

The work we know as The Platform Sutra is comprised of records compiled by disciples of the Sixth Patriarch. We have no assurance that what they have recorded is free from error. We must be very careful to keep such a work from beginning students. If it does fall into the hands of those who lack the capacity to understand it, it will turn them into wild demons of destruction. That would be deplorable.

Faugh! Who was this Chu-hung anyway? Some hidebound Confucian? An apologist for the Lesser Vehicle? Maybe a Buddhist of Pure Land persuasion who cast groundless aspersions on this sacred work because he was blind to the profound truth contained in The Meditation Sutra? Because he simply did not possess the Dharma eye which would enable him to read sutras? Or maybe he was a cohort of Mara the Destroyer, manifesting himself in the guise of a priest—shavenheaded, black-robed, hiding behind the mask of verbal prajna—bent on destroying with his slander the wondrously subtle, hard-to-encounter words of a true Buddhist saint?

These ascriptions seem to fit Chu-hung all too well. Yet someone took exception to them, saying:38

There is no reason to wonder about Master Chu-hung. A good look at him shows that he just lacked the eye of kenshō; he didn’t have the strength that comes from realizing the Buddha’s truth. Not having the karma from previous existences to enable him to reach prajna wisdom if he continued forward, and being afraid to retreat because of the terrible samsaric retribution he knew awaited him in the next life, he turned to the Pure Land faith. He began to devote himself exclusively to calling Amida’s name, hoping that at his death he would see Amida and his attendant bodhisattvas arrive to welcome him to birth in the Pure Land, and in that way would attain the fruit of buddhahood.39

So when he happened to open The Platform Sutra and read the golden utterances of the Sixth Patriarch expounding the authentic “direct pointing” of the Zen school, and he realized they were totally at odds with the aspirations he had been cherishing, it dashed all his hopes. It was this that made him rouse himself indignantly and put together the commentary we now see, as a means of redeeming the pipsqueak notions he had grown so attached to.

So he was no Confucian, Taoist, or ally of Mara either. He was just a blind priest with a tolerable gift for the written word. We should not be surprised at him. Beginning from the time of the Sung dynasty, people like him have been as common as flax seeds.

If what this person says is in fact true, the course of action that Chu-hung took was extremely ill-advised. We are fortunate that we do have the compassionate instructions of the Sixth Patriarch. Shouldn’t we just read them with veneration, believe in them with reverence, and enter into their sacred precincts? What are we to make of a person who would use his minimal literary talent to try to belittle the lofty wisdom and great religious spirit of a man of the Sixth Patriarch’s stature? Even granting that to be permissible as long as he is deluding only himself, it is a sad day indeed when he commits his misconceptions to paper and publishes them as a book that can subvert the Zen teaching for untold numbers of future students.

We generally regard the utterances of a sage as being at odds with the notions held by ordinary people; people who are at variance with such utterances we regard as unenlightened. Now, if the words of a sage are no different from the ideas the unenlightened hold to be right and proper, are not those words themselves ignorant and unenlightened, and unworthy of our respect? If the ignorant are not at variance with the words of an enlightened sage, doesn’t that make them enlightened men, and as such truly worthy of our reverence?

To begin with, Master Hui-neng was a great master with an unsurpassed capacity for transmitting the Dharma. None of the other seven hundred pupils who studied with the Fifth Patriarch at Mount Huang-mei could even approach him.40 His offspring cover the earth now from sea to sea, like the stones on a go board or the stars in the heavens. A common hedgerow monk like Chu-hung, whose arbitrary conjectures and wild surmise all come from fossicking around in piles of old rubbish, should not even be mentioned in the same breath as Hui-neng.

Are you not aware, Chu-hung, that Master Hui-neng is a timeless old mirror in which the realms of heaven and hell and the lands of purity and impurity are all reflected equally? Don’t you know that they are, as such, the single eye of a Zen monk?41 A diamond hammer couldn’t break it, the finest sword on earth couldn’t penetrate it. This is a realm in which there is no coming and going, no birth and death.

The light emitted from the white hair between Amida Buddha’s eyebrows, in which five Sumerus are contained, and his blue lotus eyes, which hold the four great oceans, as well as the trees of seven precious gems and pools of eight virtues that adorn his Pure Land, are all shining brilliantly in our minds right now—they are manifest with perfect clarity right before our eyes. The black cord hell, aggregate hell, shrieking hell, interminable hell, and all the rest are, as such, the entire body of Amida, the venerable Sage of Boundless Life, in all his golden radiance.

It makes no difference whether you call it the Shining Land of Lapis Lazuli in the East or the Immaculate Land of Purity in the South; originally, it is all a single ocean of perfect, unsurpassed awakening.42 As such, it is also the intrinsic nature in every human being.

But even while it is present in them all, each of them views it in a different way, varying according to the weight of individual karma as well as the amount of merit and good fortune each one enjoys.

Those who suffer the terrible agonies of hell see seething cauldrons and white-hot furnaces. Craving ghosts see raging fires and pools of pus and blood. Fighting demons see a violent battle ground of deadly strife. The unenlightened see a defiled world of ignorance and suffering—all thorns and briars, stones and worthless shards—from which they turn in loathing to seek the Land of Purity. Inhabitants of the Deva realms see a wonderful land of brilliant lapis lazuli and transparent crystal. Adherents of the two vehicles see a realm of transition on the path to final attainment. Bodhisattvas see a land of true recompense filled with glorious adornments. Buddhas see an eternal land of tranquil light. How about you Zen monks? What do you see?

You must be aware that the jeweled nets of the heavenly realms and the white-hot iron grates in the realms of hell are themselves thousand-layered robes of finest silk; that the sumptuous repasts of the Pure Land paradise and the molten bronze served up to helldwellers are, as such, banquets replete with a hundred rare tastes. In all heaven and earth there is only one moon; not two, not three. Yet there is no way for those of ordinary or inferior capacity to know it.

Followers of the patriarch-teachers, monks of superior capacity striving to penetrate the hidden depths, until you release your hold from the edge of the precipice to which you hang, and perish into life anew, you can never enter this samadhi. But the moment you do, the distinction between Dharma principle and enlightened person disappears, differences between mind and environment vanish. This is what the coming of the old buddha to welcome you to the Pure Land is really about. You are those superior religious seekers the sutra says are destined for “the highest rank of the highest rebirth in the Pure Land.”43

Master Chu-hung, if you do not once gain entrance into the Pure Land in this way, you could pass through millions upon millions of buddha-lands, undergo rebirth eight thousand times over, but it would all be a mere shadow in a dream, no different from the imaginary land conjured up in Han-tan’s slumbering brain.44

The Zen master Hui-neng stated unequivocally that the ten evils and eight false practices separate us from the Western Paradise. It is a perfectly justified, absolutely authentic teaching. If the countless tathagatas in the six directions manifested themselves in this world all at one time, they could not, do what they may, change a single syllable of it.

Furthermore, Master Chu-hung, if I said to you, “The Western Paradise is eighteen leagues from here,” “the Western Paradise is seven feet over there,” “the Western Paradise is eighteen inches away,” those too would be perfectly justified, absolutely authentic teachings. How will you lay a hand, or foot, on them! When I make those statements, what village do you suppose I am referring to? And if you hesitate or stop to speculate for even a split second, a broken vermilion staff seven feet long stands ready against the wall.

Resentment at finding the Sixth Patriarch’s ideas different from your own led you to take a true teacher totally dedicated to the avowed Buddhist goal of universal salvation and portray him as a dunce who does not even know the difference between the Pure Land and India. Do you think that is right?

We can only suppose that some preconception Chu-hung had formed of the Sixth Patriarch led him to think: “It’s really a shame that the Sixth Patriarch, with that profound enlightenment of his, was originally a woodcutter from the uncivilized south. Being illiterate, he couldn’t read the Buddhist scriptures. He was rude, coarse, ignorant; in fact, he was no different from those countrymen who herd cows, catch fish, and work as menials.”45

But is it really possible that even such people wouldn’t know the difference between the Pure Land and India? Even a tiny child of three believes in the Pure Land and will worship it with a sense of reverence. And we are talking about a great Buddhist teacher, one of those “difficult-to-meet, hard-to-encounter” sages who rarely appear in the world. The great and venerable Master Hui-neng was a veritable udumbara flower, blossoming auspiciously in fulfillment of the prophecies of the Buddhist sages.

This genuinely enlightened man, endowed with the ten superhuman powers of buddhahood, appeared in the world riding upon the vehicle of the universal vow and revealed a secret of religious attainment never preached by any buddha or patriarch before him. It was like the Dragon King entering the all-encompassing ocean, turning its salt water to fresh and with perfectly unobstructed freedom making it fall over all the earth as pure, sweet manna to revive parched wastelands from the ravages of long drought. It was like a rich man entering an immense treasure house, emerging with many articles rarely seen in the world, and distributing them to the cold and hungry, giving them a new lease on life by relieving their need and suffering. Such cases cannot be judged by commonsense standards, nor can they be revealed by unenlightened speculation.

Priests of today have woven themselves into a complicated web of words and letters. After sucking and gnawing on this mess of literary sewage until their mouths suppurate, they proceed to spew out an endless tissue of irresponsible nonsense. Men like that shouldn’t be mentioned in the same breath as the Sixth Patriarch.

Shakyamuni Buddha tells us that the Pure Land lies many millions of buddha-lands distant from here. The Sixth Patriarch says the distance is one hundred and eight thousand leagues. Both utterances come from men whose spiritual power—strength derived from great wisdom—is awesomely vast. Their words reverberate like the earth-shaking stomp of the elephant king. They resound like the roar of the lion monarch, bursting the brains of any jackal or other scavenger who shows the slightest hesitation.

Yet Chu-hung delivers the glib judgment that “The Platform Sutra mistakenly regards India as the Pure Land of Bliss.” “The work we know as The Platform Sutra,” he says, “consists of records compiled by disciples of the Sixth Patriarch. We have no assurance that what they have recorded is free from error.” On the pretext of being helpful, what Chu-hung is really doing is disparaging the Sixth Patriarch.

In the Rokusodankyō kōkan, a commentary on The Platform Sutra, the author writes: “According to gazeteers and geographical works I have consulted, the distance from the western gate of Ch’ang-an in China to the eastern gate of Kapilavastu in India is one hundred thousand leagues, so Chu-hung’s criticism of The Platform Sutra for mistaking India for the Pure Land can be said to have a solid basis in fact.”46

Now that’s not even good rubbish. But even allowing (alas!) that the author’s penchant for poking into old books is justified, I want him to tell me: What gazeteer or geography since the time of the Great Yü47 ever stated that India is distant from China by ten evils and eight wrong practices? It’s a great shame, really. Instead of wasting his time nosing through reference books, why didn’t he just read The Platform Sutra with care and respect, and devote himself attentively to investigating Shakyamuni Buddha’s true meaning in preaching about the Pure Land of Amida Buddha? If he had continued to contemplate that meaning, to ponder it this way and that way, coming and going, the time would have arrived when he would suddenly have broken through and grasped it. Then he would have had that “solid basis” he wants. He would be clapping his hands joyfully, howling with laughter—he couldn’t have helped himself. And what, do you suppose, that great laughter would be about?

It is absurd for someone in Master Chu-hung’s advanced state of spiritual myopia to be going around delivering wild judgments on the golden utterances of a genuine sage like the Sixth Patriarch. The same goes for the author of the Kōkan. Like Master Chu-hung, he spends his entire life living down inside a dark cave, inextricably tangled in a jungle of vines. They act like a midget sitting in a crowded theater. He tries to watch the play but is unable to see anything, so he jumps up and down and applauds when everyone else does. They also remind you of a troop of blind Persians who stumble upon a parchment leaf inscribed with Sanskrit letters. They wander off with it into the middle of nowhere, pool their knowledge and attempt to decipher the meaning of the text, but not having the faintest idea what it says, they fail to get even a single word right, and turn themselves into laughingstocks in the bargain.

Actually, such people should not even merit our attention, and yet because I am concerned about the harm they can do by misleading even a few sincere seekers, I find it necessary to lay down a few entangling vines of my own like this.

“The greatest care must be taken to keep such a work from beginning students,” says Chu-hung’s commentary. “If it does chance to fall into the hands of those who lack the capacity to understand it, it will turn them into wild demons of destruction. That would be deplorable.”

My answer to the gross irresponsibility of such a statement is this: we must take the greatest care not to pass stupid, misinformed judgments on a work like The Platform Sutra. If people with unenlightened views judge such a work on the basis of their own ignorance, they will immediately transform themselves into wild demons of destruction. That is what would be deplorable.

To begin with, tathagatas appear in the world one after another for the sole purpose of opening up paths to buddha-wisdom so sentient beings can share their realization. That has always been their primary aim in manifesting themselves. Although the sutras and commentaries contain a variety of Dharma “gates”—abrupt and gradual teachings, verbal and preverbal teachings, exoteric and esoteric teachings, first and last teachings—in the end they all come down to one teaching and one teaching alone: the fundamental self-nature inherent in each and every person.

It is no different in Master Hui-neng’s case. While The Platform Sutra containing his teaching has chapters devoted to his religious career, to his answers to questioners’ doubts, to meditation and wisdom, to repentence, and so on, they are in the end none other than the one teaching of kenshō [seeing into true self-nature]. Wise sages for twenty-eight generations in India and six generations in China, as well as venerable Zen teachers of the Five Houses and Seven Schools who descended from them, have every one of them transmitted this Dharma of kenshō as they strove to lead people to awakening in Shakyamuni’s place, devoting themselves single-mindedly to achieving the fundamental aim for which all buddhas appear in the world. None of them ever uttered one word about the Western Paradise, nor preached a single syllable about birth in the Pure Land. When the students who came after them began their study of the Way and took it upon themselves to read The Platform Sutra, none of them ever transformed into a wild demon. On the contrary, it deepened their attainment and enabled them to mature into great Dharma vessels. So please, Master Chu-hung, stop telling us about what you deplore.

It is because of misguided men like you that Nan-hai Tsung-pao of the Yüan dynasty wrote:

The Platform Sutra is not mere words. It is the principle of Bodhidharma’s “direct pointing” (at the mind) that has been transmitted from patriarch to patriarch. Thanks to it, great and venerable masters in the past like Nan-yüeh and Ch’ing-yüan cleared their minds; it cleared the minds of their disciples Ma-tsu and Shih-t’ou. The spread of the Zen school throughout the world today is also firmly rooted in this same principle of direct pointing. Indeed, is it possible that anyone in the future could clear his mind and see into his own nature without recourse to this same direct pointing?48

These words of Tsung-pao represent the accepted norm in Zen temples and monasteries everywhere. Yet there is Master Chu-hung ensconced in some remote temple, giving forth with those partisan hunches of his. The one is as different from the other as cloud from mud.

Since some people are naturally perceptive and some are not, and some have great ability while others have less, there is a correspondingly great variety in the teachings that buddhas impart to them. Buddhas work in the manner of a skilled physician. A physician does not set out to examine his patients with a single fixed medical prescription already in mind; since the ailments from which they suffer vary greatly, he must be able to prescribe a wide variety of remedies.

Take, for example, the desire for rebirth found among followers of the Pure Land school. Shakyamuni, the Great Physician King who relieves the suffering of sentient beings, in order to save Queen Vaidehi from the misery of a cruel imprisonment, converted her to firm belief in the Pure Land of her own intrinsic mind-nature by using good and skillful means that he devised for her particular situation. It was a specific remedy prescribed for the occasion and imparted to Queen Vaidehi alone.49

Men like Chu-hung, not having penetrated the truth of the Buddha’s wonderful skillful means, cling mulishly to the deluded notion of a Pure Land and a buddha that exist separately, apart from the mind. They are incapable of truly grasping that there is no such thing as a buddha with his own buddha-land, that the village they see right in front of them and the village behind them and everywhere else—it is all buddha-land. There is no such thing as a buddha-body either. South and north, east and west, everywhere is the buddha-body in its entirety. When Chu-hung, being incapable of truly grasping such truths, heard a genuine Buddhist teaching such as the one that declared, “You are separated from the Western Paradise by the ten evils and eight false practices in yourself,” he was appalled to find it did not agree with the conception of the Pure Land he had created in his own mind. He figured that if he roundly condemned it, he could keep others from hearing or reading about it.

If we let Chu-hung have his way and keep beginners from reading The Platform Sutra on the grounds that it is unsuitable for them, then The Flower Garland Sutra, and the Lotus, Nirvana, and other Maha yana sutras in which the Buddha reveals the substance of his enlightenment are not suitable for them either. I say this because the great master Hui-neng, having penetrated the profound and subtle principle of the buddha-mind, having broken decisively through the deep ground whence the ocean of Buddhist teaching finds its source, spoke with the same tongue, sang from the same mouth, as all the other buddhas.

Furthermore, a Chinese commentary on The Flower Garland Sutra, the Hua-yen Ho-lun, states that:

aspirants belonging to the first rank recognize the Buddha’s great power, observe his precepts and, by utilizing the power of the vow working in themselves, gain birth in his Pure Land. But that is not a real Pure Land, only a provisional manifestation of one. The reason aspirants seek it is because they have not seen into their own true nature, hence do not know that ignorance is in itself the fundamental wisdom of the tathagatas, and are thus still subject to the working of causation. This is the principle from which a scripture such as The Amida Sutra is expounded.”50

We may be sure if Chu-hung had seen this passage, he would have grabbed his brush and dashed off some lines about the Hua-yen Ho-lun being unfit for beginners. The Hua-yen Ho-lun is fortunate indeed to have avoided the blind-eyed gaze of the “Great Teacher of the Lotus Pond.”51 It saves us from having to listen to warnings about “giving it to people of small capacity,” and “turning them into wild demons.” Tsao-po Ta-shih (author of the Ho-lun), dwelling within the stillness of eternal samadhi, should be absolutely delighted at this stroke of good fortune.

Seen by the light of the true Dharma eye, all people—the old and the young, the high and the low, priests and laypeople, wise and otherwise—are endowed with the wonderful virtue of buddha-wisdom. It is present without any lack in all of them. Not one among them—or even half of one—is to be cast aside and rejected because he is a beginner.

Nonetheless, since students who are first setting out along the Way do not know what is beneficial to their practice and what is not, and can’t distinguish immediate needs from less urgent ones, we refer to them for the time being as beginners. They read the sacred Buddhist writings and entrust themselves to the guidance of a good friend and teacher. Later, upon bringing the Great Matter to completion and fully maturing into true Dharma vessels, they will acquire a wonderful gift for expressing their attainment and, using that ability, will strive to impart the great Dharma-gift to others, holding buddha-wisdom up like a sun to illuminate the eternal darkness, keeping the vital pulse of that wisdom alive through the degenerate age of the latter day. It is these we can call true descendants of the buddhas, those whose debt of gratitude to their predecessors has been repaid in full.

But if they are compelled to practice the nembutsu along with all other students of whatever kind and capacity, on the grounds that they are beginners, we will have all the redoubtable members of the younger generation—those Bodhidharma praised as being “native born to the Mahayana in this land,” people gifted with outstanding talent, who have it in them to become great Dharma pillars worthy to stand in the future with Te-shan, Lin-chi, Ma-tsu, and Shih-t’ou—traipsing along after half-dead old duffers, sitting in the shade next to the pond with listless old grannies, dropping their heads and closing their eyes in broad daylight and intoning endless choruses of nembutsu. If that happens, whose children will be found to carry on the vital pulse of buddha-wisdom? Who will become the cool, refreshing shade trees to provide refuge for people in the latter day? All the authentic customs and traditions of the Zen school will fall into the dust. The seeds of buddhahood will wither, die, and disappear forever.

I want these great and stalwart students of superior capacity to choose the right path. If, at a crucial time like this, the golden words in the Buddhist canon, all the Mahayana sutras that were compiled in the Pippali cave52 for beginners to use in after ages, everything except the three Pure Land sutras, is relegated to the back shelves of the bookcase and left there untouched to end up as bug-fodder, buried in the bellies of bookworms, it will be no different from stacks of fake burial money piled forgotten in an old shrine deep in the mountains, of absolutely no use to anyone. It would be deplorable! Those people mentioned before—the ones The Meditation Sutra says are “destined for the highest rank of the highest rebirth in the Pure Land, suited to read the Mahayana sutras”—would cease to exist.

In the way that it slanderously rejects anything counter to its author’s own notions, Chu-hung’s commentary can be compared to the book-burning pit of the infamous Ch’in emperor.53 The Ch’in emperor, deeply resentful when he found that his tyrannical policies were totally at odds with the ancient teachings in the Confucian writings, had the Confucian teachers buried alive and all their books consigned to the flames. Chu-hung has perpetrated a disaster of similar magnitude.

The policies the three Wu emperors adopted to suppress Buddhism were undisguised.54 Chu-hung worked to destroy the true teachings secretly. The former did it openly, the latter did it on the sly, yet the crime is one. However, Chu-hung is not really to blame for his transgressions. He did what he did because he had never encountered an authentic master to guide him and was thus unable to open the true Dharma eye that would have enabled him to see through into the secret depths. He did not possess the wonderful spiritual power that comes from kenshō.

Yet Chu-hung is given as “an example for good teachers past, present, and future.” People praise him as “foremost among the great priests of the Zen, Teaching, and Precepts schools.” They must be out of their minds!

The Zen forests of today will be found, upon inspection, to be thickly infested with a race of bonzes very similar to Chu-hung. They are everywhere, fastened with a grip of death to the “silent tranquillity” of their “withered-tree” sitting, which they imagine to be the true practice of the Buddha’s Way. They don’t take kindly to views that don’t agree with their own convictions, so they regard the Buddha’s sutras as they would a mortal enemy and forbid students to read them: they fear them as an evil spirit fears a sacred amulet. They are foolishly wedded to ordinary perception and experience, believing that to be Zen, and they take offense at anything that differs from their own ideas, so they view the records of the Zen patriarchs as they would a deadly adversary and refuse to allow their students near them: they avoid them as a lame hare avoids the hungry tiger.

With adherents of the Pure Land tradition shunning and disparaging the sacred scriptures of the buddhas and followers of Zen trying to discredit them with their slander, the danger to the Buddhist Way must be said to have reached a critical stage.

Don’t get me wrong. I am not urging students to become masters of the classics and histories, to spend all their time exploring ancient Chinese writings, or to lose themselves in the pleasures of poetry and letters; I am not telling them to compete against others and win fame for themselves by proving their superiority. They could attain an eloquence equal to that of the Great Purna, possess knowledge so great they surpassed Shariputra, but if they are lacking in the basic stuff of enlightenment, if they do not have the right eye of kenshō, false views, bred from arrogance, will inevitably find their way deep into their spiritual vitals, blasting the life from the seed of buddhahood, and saddling them with a one-way ticket to hell.

It is not like that with true followers of the Way. They must as an essential first step see their own original nature as clearly as if they are looking at the palm of their hand. When from time to time they read the scriptures that contain the words and teachings of the buddha-patriarchs, they will illuminate those ancient teachings with their own minds. They will visit genuine teachers for guidance. They will pledge with firm determination to work their way through the final koans of the patriarch teachers and, before they die, to produce from their forge a descendant—one person or at least half a person—as a way of repaying their deep debt of gratitude to the buddha-patriarchs. It is such people who are worthy to be called “the progeny of the house of Zen.”

I respectfully submit to the “Great Teacher of the Lotus Pond”: If you wish to plant yourself out in some hinterland where you can be free to finger your lotus-bead rosary, droop your head, drop your eyelids, and intone the nembutsu because you want to be born in the Land of Lotus Flowers, that is no business of mine. It is entirely up to you. But when you start gazing elsewhere with that myopic look in your eyes and decide to divert yourself by writing commentaries that pass belittling judgment on a great saint and matchless Dharma-transmitter like the Sixth Patriarch, then I must ask you to take the words you have written and shelve them away far out of sight, where no one will ever lay eyes on them. Why do I say that? I say it because the great Dragon King, who controls the clouds that sail in the heavens and the rains that fall over the earth, cannot be known or fathomed by a mud snail or a clam.

One of the worthy teachers of the past explained it thus:

The “western quarter” refers to the original mind of sentient beings. “Passing beyond millions and millions of buddha-lands” [to attain rebirth in the Pure Land] signifies sentient beings terminating the ten evil thoughts and abruptly transcending the ten stages of bodhisattvahood. “Amida,” signifying immeasurable life, stands for the buddha-nature in sentient beings. “Kannon” and “Seishi,” the bodhisattva attendants of Amida, represent the incomprehensible working of original self-nature. “Sentient being” is ignorance and the many thoughts, fears, discernments, and discriminations that result from it. “When life ends” refers to the time when discriminations and emotions cease to arise. “Cessation of intellection and discrimination” is the purifying of the original mind-ground, and indicates the Pure Land in the West.

It is to the west that sun, moon, and stars all return. In the same way, it is to the one universal mind that all the thoughts, fears, and discriminations of sentient beings return. It is thus one single mind, calm and undisturbed. And because Amida Buddha exists here, when you awaken to your self-nature the eighty-four thousand evil passions transform instantly into eighty-four thousand marvelous virtues. To the incomprehensible working that brings this about, we give the names Kannon, Seishi, and so on. The uneasy mind you have while you are in a state of illusion is called the defiled land. When you awaken and your mind is clear and free of defilement, that is called the Pure Land.55

Hence in The Essay on the Dharma Pulse Bodhidharma says that “the nembutsu practiced by Buddhist saints in the past was not directed toward an external buddha; their nembutsu practice was oriented solely toward the internal buddha in their own minds. . . . If you want to discover buddha, you must first of all see into your own true nature. Unless you have seen into your own nature, what good can come from doing nembutsu or reciting sutras?”56