Whitney Hite saw the familiar 706 area code flash on his caller ID and picked up the phone immediately. Sure enough, the call was from his old friends in Athens, Georgia—the Lady Bulldogs’ coaching office, to be exact. “Hey,” Georgia assistant Jerry Champer said, “we’re all here in the office. Looks like that 800 free relay you guys swam at Pac-10s was pretty fast.” Hite smiled. The Bears had closed out the first night of an otherwise disappointing Pac-10 Championships by winning the 800-yard freestyle relay in a meet-record time of 7:08.13, and he knew his old colleagues were curious as to how formidable a challenge Cal might present in the event at NCAAs.

“Yeah,” Hite said. “It was okay.”

“Which leg did Natalie swim?”

Hite paused for dramatic effect. “She didn’t.”

Indeed, with Erin Reilly, Micha Burden, Ashley Chandler, and Lauren Medina each recording personal bests for the 200-yard distance, the Bears had been able to cruise to a conference title in the relay without requiring the services of their best swimmer. Now, with Coughlin poised to replace Burden at NCAAs, Cal would have a legitimate shot at breaking the 3-year Georgia/Auburn stronghold over the relay events. The increased workload might jeopardize Coughlin’s chances of defending her titles in the third of her individual events, the 200 backstroke, but at this point she didn’t care. She was so sick of her collegiate winning streak and the accompanying pressure that she just wanted to get that part of her career over with and start preparing for the Olympic Trials. Winning a relay sounded so much better than anything she might accomplish on her own, because, for a change, it wouldn’t be about her.

Finally, after all the dissension of the past 8 months, and before embarking upon the pursuit of individual Olympic glory, this would be Coughlin’s chance to be one of the girls.

As the NCAA Championships approached in mid-March of 2004, the Bears were a team in need of a boost. For the first time all season, they had failed to achieve one of their team goals—to “win the swimming” at Pac-10s. Scoring the most points at that meet, McKeever knew, would be virtually impossible because of Cal’s inferiority in the three diving events. (To put the disparity in perspective, the Golden Bears would score 33 diving points at Pac-10s; the next-lowest total of any team was 180, and the next-lowest after that 290.) So the Bears hoped they could outshine their Pac-10 rivals in the rest of the competition, even if they would be the only ones keeping track of that score.

Though there were some impressive Cal swims at the Belmont Plaza Pool in Long Beach, California, the Bears’ overall performance was somewhat flat. For one thing, the meet was somewhat anticlimactic after the undefeated dual-meet season, and particularly the dramatic victory over Stanford—with the far more important NCAA meet still to come. And with so many Cal swimmers having already made their cuts for NCAAs, there was less of a sense of urgency than normal.

The Pac-10s also served as a sobering reminder that dual-meet success does not necessarily equate to similar prosperity under a different scoring format. Whereas dual meets reward depth and emotionally charged efforts, competitions like Pac-10s and NCAAs winnow out less accomplished swimmers with preliminary rounds and penalize inconsistency. Not only does a swimmer have to be one of the fastest in her event to score a lot of points, but she must prove it twice in the same day: Fail to finish in the top eight in the prelims, and that night the best a swimmer can do is to place ninth, even if her time in the consolation final was faster than that of the winner’s in the championship heat.

Coughlin, of course, was well familiar with that setup. What she wasn’t as accustomed to was—well, virtually everything else going on in her life at the time. She and Ethan Hall were still dealing with relationship issues, and she was also experiencing some sleep deprivation, thanks largely to a faulty fire-alarm system in her condo complex. Several false alarms on one particularly brutal night forced her to make repeated trips down to the lobby. Delirious come morning, she promptly took a psych midterm in the one upper-division class she cared about—and, in her words, “bombed.” (It was a relative term; Coughlin, it turned out, got a B.) Then, on the Friday night before Pac-10s, Coughlin cooked herself some jambalaya and, an hour after dinner, contracted food poisoning, probably courtesy of some spoiled sausage. She spent the next 24 hours, in her words, “vomiting my guts out.”

Other than that, it was a great week.

During those moments when neither her condo’s security system nor her stomach was sounding alarms, Coughlin managed to make some progress on the agent front. She and McKeever, along with their friends at CSI Management, Leland Faust and Steven Clark, interviewed three finalists separately in San Francisco: Octagon’s Peter Carlisle and his posse of associates; Evan Morganstein of Premier Sports Management; and Janey Miller. As McKeever had predicted weeks earlier, Coughlin was taken by Miller’s down-to-earth personality and unpretentious, stripped-down approach. Having repped such prominent Olympians as Michael Johnson, Apollo Anton Ohno, and Amy Van Dyken before she’d left IMG, Miller offered big-league experience with personal service. “I’d be her first client, which is sort of cool, if you think about it,” Coughlin said. “I’d know that whatever she’s doing at a given time, she’d be out there working for me.”

Miller, said McKeever, was “the only one who said she wouldn’t have a problem with Natalie having different agents for Australia and Asia, which are places she could theoretically cash in. It would be sort of exciting to go with Janey, to blaze a trail.”

Coughlin was initially skeptical of Morganstein, who had carved out a niche as a “swimmers’ agent”—he had 20 of the world’s best in the sport and also did some work for coaches, such as McKeever. Coughlin didn’t want to be treated as one of a large group or packaged with others as part of a marketing strategy. But after their meeting, she said, “Evan really surprised me. He had really thought it through. He told me he’d use a specific publicist out of LA, for one thing.” McKeever agreed that “Evan was really impressive. He had a plan for everything, and he told Nat how she was special, how he’d treat her differently, and how she’d be in charge of the big decisions, which is perfect for her personality.” The Octagon crew, by comparison, had seemed stiff and slick. “They had five people there,” McKeever said. “If she were the big-firm type of person, I don’t think she’d have come here to swim in the first place.”

That Coughlin was still an amateur at the 2004 Pac-10s was somewhat of an upset, given the mentality she’d carried into Pac-10s a year earlier. Even McKeever was surprised when Coughlin, during a team meeting the night of the Bears’ arrival in Long Beach, got up to address her teammates—as did each of the seniors—and said, “A year ago at this time I was sitting there listening to the seniors talk and I was sure it was my last Pac-10s. But it worked out that I was able to come back, and I’m really glad I did.” Whoa, McKeever thought.

Though she would be swimming her usual trio of individual events at NCAAs (the 100 and 200 back and 100 fly), Coughlin had chosen a different schedule for Pac-10s. She was intrigued by the notion of going head-up against USC’s Kaitlin Sandeno in the 200-yard individual medley, the event in which Coughlin had shined back in December during the Princeton Invitational. (And yes, the Pac-10 meet, unlike each of the season’s dual meets and NCAAs, would be conducted in yards, rather than meters, if only to further confound those who were trying to derive meaning from the times.) Back in her previous incarnation as a teen phenom, Coughlin had been especially potent in the IM events, but she had largely abandoned them during most of her collegiate career. This, however, was for a good cause: Not only was Coughlin no fan of the Trojans, but she also relished the idea of beating the formidable Sandeno. The showdown took place on the meet’s second day, and it was no contest. Coughlin cruised to victory in 1:54.95—the second-fastest 200-yard IM ever, well ahead of Summer Sanders’s Pac-10 record—while Sandeno was second, in 1:57.53.

“How did you get her to swim the 200 IM?” USC coach Mark Schubert asked McKeever.

“I just asked,” she replied, shrugging.

Coughlin also won the 100 back and 100 free and led off Cal’s meet-closing victory in the 400 free relay. Dramatic swims by breaststrokers Marcelle Miller (in the 200) and Erin Calder (in the 100) pushed the Bears’ total of NCAA qualifiers to 15, an all-time high. Yet Cal fell well short of being the highest-scoring team in the swimming events and finished fourth behind Stanford, UCLA, and Arizona in the overall tally.

For Coughlin, at least there was improvement on one important front: Upon her return to Berkeley, she and Hall had worked through their problems, and their relationship had become stronger than ever.

Erin Reilly knocked on McKeever’s office door a few minutes after one of the team’s final practices before the NCAA Championships and slipped her slender frame inside. Check that—for a swimmer, Reilly wasn’t slender; she was toothpick thin. Whereas some of the fleshier competitors benefited from Fastskin suits because the tight material constricted their fat and reduced buoyancy, Reilly need not have bothered. The bodysuits actually appeared slightly baggy on her. The pretty strawberry blonde would probably be the skinniest swimmer at NCAAs, not to mention the fairest skinned. She was also one of the more durable, a workhorse willing to literally go the extra mile.

“You wanted to see me?” Reilly asked, thereby doubling the total number of words her coach had heard her utter in the past week.

“Yeah, sit down,” McKeever said, motioning toward the small couch near the door. “Let’s talk about what you’re swimming at NCs.”

Specifically, McKeever wanted to address the second day of the 3-day meet, when Reilly planned to swim the 200-meter freestyle prelims in the morning and then, if she produced one of the 16 fastest times, come back and do it again that night. The catch was, that was also the night of the 800 free relay, meaning she wouldn’t be at her freshest with a national title at stake.

Reilly was set on swimming the 400 free the first day of the meet and the 1,500 free the third day; that left either the 200 free or the 200 fly, and both she and Hite were sold on the former. On the final night of Pac-10s, Reilly had competed in the 1,650 (yard) freestyle, finishing sixth, and the 200 fly back-to-back. It was a vicious double that Reilly had vowed not to repeat at NCAAs, which had a similar schedule on the third and last night of competition. While acknowledging that Reilly, who had the nation’s 17th-fastest seed time in the 200 free going in, was more of a natural fit for that event than she was the 200 fly (for which she was seeded 13th), McKeever asked her to consider making a sacrifice for the good of the team.

“Look, Erin, I really think we have a chance to win a national championship in the relay, and you’ll be part of that,” McKeever told Reilly. “Now, that may happen to you again before you’re done here, and I hope it does, but there are no guarantees. I just want you to understand how incredibly special that could be, something you’ll remember for the rest of your life. I want you to have that experience. We might be able to do it even if you’re not fully rested, but if you’re fresh, it gives us an even better chance.”

Equally important was what McKeever didn’t say: This is what you’re doing, period. Though passionate and secure in her convictions, McKeever simply wasn’t that kind of coach. Just as she would never dream of ordering Coughlin to swim the 200 back rather than the 100 free at Olympic Trials, she wasn’t going to mandate this switch to Reilly. It was going to have to come from her, and in this case, Reilly saw the logic in her coach’s presentation and quickly agreed.

Later that day, McKeever sat in her office, staring up at the scores of mementos on the walls, most of them snapshots of current and former team members during retreats or other group activities. There were also framed magazine covers featuring Coughlin, Haley Cope, Staciana Stitts, and other former Cal stars, and a tray on her desk with paperwork piled up taller than Keiko Amano. “In a way it will be liberating when Natalie finishes,” McKeever confessed, “so I can start really coaching some of these other swimmers, like Erin Reilly. Right now I just tell her how great she is because I think she needs to understand that most of all. But there are so many technical things I’d really like to try with her, because she could end up doing some really amazing things.”

At the same time, McKeever was wistful about the impending end of Coughlin’s collegiate career. “What most of these girls don’t get is that this is the best it will ever be,” the coach said. “Sure, they have classes to go to and papers to write, but they don’t have to work. They get to swim, and they get to be part of a team. Someday, Danielle Becks will have kids, and at some point they’ll start swimming, and they’ll know who Natalie Coughlin is and what she accomplished. And Danielle will tell them, ‘I swam with her for 4 years, and we were on a relay that set an American record, and we beat Stanford together for the first time in 28 years.’ Some of them might sit there now and complain about Natalie—how she always gets to swim in the same lane at practice or how I give her special treatment—but they don’t get what she’s meant to this program or this university. Someday they probably will, and I’ll bet they’ll see things differently.”

For a team intent on finishing in the top five nationally, the Bears seemed oddly vulnerable. “Keiko Amano was in here earlier today,” McKeever said, “and she started crying as she was complaining about her shoulder pain. I said, ‘Keiko, think about where you are. When you came to Cal, did you honestly think you’d make NCAAs?’ She said, ‘I didn’t have any goals.’ I said, ‘You’re 5 foot 2, and you’ve been a huge part of our success. You’ve clocked the fastest time on all those relays—faster than Danielle and Emma, faster than everyone except Natalie. You need to enjoy the moment and get through this last stretch.’ She’s stressed about missing school, which I understand, but I want her to realize what an opportunity this is.”

McKeever, too, was emotional as NCAAs neared. She was jarred by the recent departures of two of her friends in the small community of female swim coaches: Longtime Minnesota mentor Jean Freeman had retired; and Iowa coach Garland O’Keeffe, according to McKeever, had been pushed out after having recently had her first child. “I was a mess last week,” McKeever said. “I got frustrated with someone every single day, to the point where I realized I had to get away. It’s so great having Whitney, because I knew that even at this point of the season, I could leave and he’d have it totally under control. So on Saturday I flew down to LA for the day and saw my brother Mac and his kids, and my sister and her new husband drove up. It was a nice reminder that there’s more to life than swimming, which was exactly what I needed.”

The Bears’ workouts had been especially light since they’d returned from Pac-10s—not that McKeever was using the “T” word. Though her swimmers reduced yardage before big meets, it was erroneous, she felt, to infer that her swimmers tapered before big meets. “I don’t like using the word tapering,” agreed Dave Salo of Irvine Novaquatics, McKeever’s old coaching colleague, “but I’ve succumbed to my athletes’ desire to have it defined that way. It’s probably more psychological than anything. Traditionally, tapering is a methodical approach to cutting back on yardage before major competitions. I think ‘fine-tuning’ is actually a far more accurate term.”

McKeever was not averse to her swimmers engaging in another traditional pre-NCAA ritual: shaving their bodies. Some swimmers in other programs, in an effort to achieve more dramatic results come competition time, accumulated as much body hair as possible until “shaving” time arrived. Coughlin viewed the process far more casually. “I have the hairiest legs in the world, but I only shave once a week,” she said. “I’m so lazy. So, yeah, I’ll shave for this meet, but with the Fastskin suits, it’s really not as big an issue as it used to be.”

Then there was teammate Helen Silver, who, while hanging out with teammates after Pac-10s, impulsively picked up a pair of blunt scissors and sheared off roughly two-thirds of her blond locks. “Hey,” she later explained, “sometimes you just have to feel the moment.”

Four of her teammates were about to, in a big way.

Lauren Medina could feel another panic attack coming on, this one at the least opportune time imaginable. The night session of day 2 at NCAAs in College Station, Texas, was nearing its conclusion, and Medina and fellow swimmers Coughlin, Reilly, and Chandler were getting ready for the 800 free relay, an event they fully expected to win. Yet they were worried, because Medina, their tough-as-dorm-food relay anchor, hadn’t been herself for more than a week, and now she looked shakier than she should have as the start time neared.

Back in December, when Medina had had her anxiety attack at the Princeton Invitational and had to be pulled from the pool by a lifeguard, she figured it was a onetime freak-out and tried to block it from her mind. But while anchoring Cal’s winning 800 free relay at Pac-10s, she’d started to feel the same strain in her breathing, and ever since then at practice, she’d been subject to similar symptoms. A week before NCAAs, Medina had started thinking about the relay during a workout set and become panicked again, eventually clinging to the wall as she hyperventilated. McKeever helped her to the deck, and Medina began bawling. “Teri, I’m terrified,” she finally said. “I’m scared we’ll win. I’m scared I’ll let us down and we’ll lose.”

For the next 7 days, McKeever, Hite, and the other Cal swimmers had attempted to keep Medina loose and calm, but now—well, this was crunch time, and the ebullient junior literally had to sink or swim.

“Lauren, look at me,” McKeever implored a few minutes before the race. “It’s going to be okay. No matter what happens, I’m here for you. If you need me to walk behind the blocks with you and hold your hand until it’s time to jump in, that’s what I’ll do.”

Medina began to relax. It had been an inspired meet so far for the Bears, who were on pace to reach their goal of a top-five finish. On day 1, Chandler had finished fourth in the 400 free, officially shedding her previous year’s label as a freshman bust. Natalie Griffith had placed 13th in the 200 IM, an event won by Sandeno. Earlier in day 2, Coughlin had defended her titles in the 100 fly and 100 back, while freshman Annie Babicz had placed 15th in the 100 breast, and Chandler (fourth) and Medina (11th) had scored in the 200 free. Medina had gotten through her individual race without incident, but now, with the relay approaching, she looked like a swimmer who wanted to be anywhere other than where she was.

Cal was seeded fifth in the relay based on season-best times, behind Auburn, Michigan, Georgia, and Florida, but everyone knew the Bears would have a lead after the first leg. That was because Coughlin, despite having already swum four races that day (prelims and finals for the 100 fly and 100 back), was primed to lead off with a bang. The question was whether Reilly, swimming second, would be able to hold that lead. Georgia was a particular threat, with star sprinter Kara Lynn Joyce set to swim the second leg. Reilly did not relish her role as the hunted, and she, too, had a serious case of nerves before the race. As she later recalled, “I was warming up in the diving pool, and Nat was standing there in her parka. I was really nervous. Nat looked down and put her hands on my shoulders and said, ‘We can do it. You know we’re gonna win. You know you’ve worked so hard for this.’ It really calmed me down. She’s so good at making me—at making a lot of people—feel comfortable in a situation like that.”

Then Coughlin went out and swam a sizzling 1:55.82 first leg, which really made the Bears feel comfortable. Coughlin’s time was faster than Auburn’s Margaret Hoelzer’s had been in winning the 200 free earlier that night, and it put Cal more than 2½ seconds ahead of Auburn and nearly 3½ ahead of Georgia. Reilly, mindful of Hite’s last-minute instruction not to “blow it in the first 100,” dove in and tried to maintain an even pace, fully expecting Georgia’s Joyce to make her run. “I remember every wall going into my turn and expecting to see Kara Lynn,” Reilly recalled.

She never did—Reilly held her ground against Joyce, swimming a split of 1:57.97 to Joyce’s 1:57.44. It was the equivalent of a freshman basketball player hitting a game-winning three to send his or her team to the Final Four. By race’s end, Reilly had recorded a faster split than two of the women who would join Coughlin on the US 800 free relay at the Olympics—USC’s Sandeno (1:58.15) and Wisconsin’s Carly Piper (2:00.00). When Ashley Chandler came through with an impressive 1:58.60, just 0.61 second slower than the 200 she’d just swum in the individual final, it was pretty much over—provided Medina was able to manage her anxiety.

During Reilly’s leg, Medina had looked into the stands and spotted her brothers and other family members, which sent her heart racing. “Natalie,” she said, turning to Coughlin, “tell me I can do this.”

“Lauren,” Coughlin said forcefully, “you can do this.”

She did, easily. “It was almost like as soon as Lauren jumped in, we were home,” Reilly recalled. One assistant coach from a Pac-10 rival actually walked up to Hite and congratulated him during Medina’s first lap. When Hite reminded him there were seven additional laps remaining, his colleague scoffed and said, “That’s Lauren Medina in the water—you guys have got it.” Sure enough, after cruising home in 1:58.55, Medina joined her teammates in a gleeful and borderline hysterical celebration. The Bears had won in 7:50.94, shattering Arizona’s NCAA record by nearly 5 seconds and beating second-place Georgia by nearly 2½. For the first time since 2000, a team other than Georgia or Auburn had won a relay, and the Cal contingent danced around like it had won a team championship.

At that moment it was all worth it for Coughlin: the decision to come back for her senior season; the sniping she’d endured from grumpy teammates; the 13 swims over 3 days (nine to this point) that would sap her of precious energy by meet’s end. Because each of her fellow relay swimmers’ journeys resonated with her, and because she recognized them as products of the uncanny McKeever/Hite coaching partnership, Coughlin was overcome by tears as she reveled in their unmitigated joy. “Natalie is a very private, subdued person most of the time, and sometimes we have a hard time seeing her humanity come out,” teammate Helen Silver said. “But the way she was after that relay, you could totally see how much she genuinely cared.”

So, too, did the other relay swimmers, none of whom had ever appreciated Coughlin quite so much as they did at that moment. “Thank you for believing in me!” Medina screamed as she wrapped Coughlin in a Golden Bear hug. Reilly was especially animated; her gesticulating victory dance during Medina’s final lap was captured by ESPN’s cameras on its tape-delayed telecast, allowing swimming fans to watch her, as she described, “looking like such a dork.” Coughlin, too, made fun of her teammate when, a few minutes after the race, Reilly asked, “Do they give us our rings on the award stand?”

“Erin,” Coughlin answered, laughing, “they have to measure us for them first. We get them in like a month or two.”

When Jim Coughlin saw the flameout, he jumped from his seat and instinctively moved toward the pool. His little girl was in distress, and he was ready to jump into the water and save her, right there during the 200-meter backstroke final. “Natalie was born with a heart murmur,” he would later explain. “When I saw her just stop all of a sudden, I didn’t know what had happened, but I feared the worst.”

Later, upon learning of her father’s recollection, Natalie rolled her eyes. “Oh, come on,” she said, laughing. “My heart murmur is not a big deal. Lots of people have them. It’s nothing.”

To her worrywart dad’s great relief, Coughlin was in no physical danger—she was merely dead in the water. After charging to the lead on a pace that would have earned her a seventh world record, Coughlin, with two laps remaining, felt her legs abruptly desert her. Flummoxed by the physical breakdown, Coughlin’s technique went to pieces, and an audible gasp could be heard in the natatorium. This remarkable swimmer, who had never lost a meaningful race in college, who was an unprecedented 11-for-11 in previous NCAA individual finals, was finally going to be beaten. As Coughlin slogged through the final two laps, a pair of Auburn swimmers, Kirsty Coventry and Margaret Hoelzer, swept past her, setting off a rowdy celebration among the eventual team champion’s contingent. McKeever and her swimmers, meanwhile, looked like wax-museum figures. As Swedish swimmer Emma Palsson later told a teammate, “I think I had some sort of a heart attack.”

Drained physically and emotionally after the previous night’s drama, Coughlin had not been in the best space before the race, an event she happened to detest in the first place. Largely because of Helen Silver’s proficiency in the event, Coughlin had swum the 200 back just once all season, in December at the Princeton Invitational, and seemed confused as to how to pace herself once it began. She swam as though she merely wanted to get the race over with—which, in fact, she did. Even as Coughlin was humming, at 75 meters Hite, watching from the stands, had winced: He knew it was over. Sure enough, coming out of the turn at 150, Coughlin suddenly appeared as though she’d been zapped by a Taser gun.

At race’s end, Coughlin pulled off her goggles and gasped for air, draping herself over the lane line like an exhausted preschooler at the end of a swimming lesson. Her legs were throbbing; her heart was pounding; her head was spinning. This was the moment, in theory, that she’d been dreading, yet defeat, that most unfamiliar of concepts, washed over her with a surprisingly gentle touch. The first thing she thought was Thank God it’s over. She braced herself for the next emotion—misery, searing anger, panic—but relief was all she felt.

She walked gingerly to the warm-down pool and began swimming slowly. Her legs felt like wet stacks of all her newspaper clippings, and no one, not even McKeever, felt compelled to bother her. Coughlin had one last race to swim as an amateur, the leadoff leg of the 400 free relay, which would take place in less than an hour. Satisfied that she had rid her exhausted body of enough excess lactic acid to ward off additional pain, Coughlin did an ESPN interview, smiling gracefully throughout the conversation, then got out of the water and entered an adjacent hot tub. “Are you ever going to get out of there?” the coach of an opposing team asked, and Coughlin smiled faintly and shook her head no.

Finally, tentatively, McKeever approached the tub, discerning correctly that she was the last person Coughlin wanted to see. The two women possessed a mother/daughter closeness that, in the wake of this shocking defeat, triggered the first traces of anger in Coughlin, irrational though they may have been. Why did Teri make me swim this event I hate, just because of some stupid streak I have? Why does she want me to swim it in the Olympics, when I’m so much more comfortable with the 100 free?

Within seconds, Coughlin let it all go. By the time McKeever asked, “Are you okay?” the swimmer had regained her swagger. “I’m fine,” she said, slapping the water with her left hand. “Maybe it hasn’t hit me yet, but I’m okay with this.” McKeever, who already knew the answer, asked if she’d be able to go in the relay; Coughlin glared back and said, “Yeah, I’m fine.” She rose from the hot tub and joined her teammates on the pool deck, channeling what was left of her emotional energy.

In terms of reaching their goal of a top-five finish, the Bears were now in a tough spot. Notorious in previous years for disappointing efforts at NCAAs—at least among the Cal men’s swimmers, who often teased them about it—the Bears had altered that pattern during the meet’s first few days and seemed destined to finish no worse than fifth, behind Auburn, Georgia, a surprisingly potent Arizona (a team Cal had defeated in a dual meet), and Florida. Stanford, however, was lurking, and on the third night the Cardinal was closing fast. “I have to give Stanford and Richard (Quick) a lot of respect,” McKeever had said shortly before leaving for the meet. “Every time they have to come up with big swims—at least, until this past dual meet—they’ve done it at key times, for years and years.”

The Bears’ best chance to put away their rivals had been in the night’s first event, the 1,500 free. Chandler, having already produced a pair of individual fourth-place finishes to go with the 800 free relay triumph, was the 13th-seeded swimmer coming in, and another stellar effort would allow Cal to breathe easier. But Chandler, never a fan of the grueling event, simply wasn’t into it; she was overheard telling teammate Kate Tiedeman that “by the end of this race, they’ll never ask me to swim the mile again.” She finished 36th.

Reilly, meanwhile, gave the Bears some solace: Seeded 24th, she shaved several seconds off her best time, to finish 14th. Amazingly, she then turned around and finished 12th in the rigorous 200 fly, capping a freshman season that defied anyone’s reasonable projections, save those of her coaches.

One event earlier, Georgia’s Kara Lynn Joyce had won the 100 free in 53.15 seconds, officially an NCAA record. As the 400 free relay neared, Coughlin flashed back to the previous 2 years. Twice, former Bulldogs star Maritza Correia had set NCAA records in winning the 100 free. On each occasion, just before the start of the relay, Coughlin had stood on the blocks and listened to her grandfather, Chuck Bohn, yell, “Take it back!” Both times she had dutifully complied, meaning that Correia’s collective total of NCAA-record ownership had spanned an hour and 40 minutes.

Taking back this record from Joyce seemed far-fetched, given the way Coughlin’s body had just collapsed in the 200 back. But this was a travesty, she thought. I don’t need to take back this record, because I already own it. Indeed, at the Stanford dual meet, Coughlin’s opening split in the meet-closing 400 free relay had been 52.97 seconds, just off Jenny Thompson’s American record and well below the existing NCAA mark. Yet, she later learned, Stanford officials had neglected to measure the pool, a requirement in order to submit the record for certification. It was another reason to dislike Stanford and, more important, another source of motivation before the final race of her collegiate career.

Standing on the blocks, Coughlin looked to a nearby lane and saw Joyce, whom she liked, getting into her crouch. I’ll kick her ass, Coughlin thought. As the starting gun sounded, she darted into the water like a torpedo, summoning perhaps the best start of her entire season. Four laps later, when she touched the wall, Coughlin was still seething. She looked at the scoreboard and saw her time: 52.81 seconds, a new American record. So much for her demise. “She set that record on guts and anger,”

Whitney Hite said the day after the race. “Physically, she clearly wasn’t in a good place. But she’s tough when she’s angry. Anyone who believes she’s vulnerable now and who questions her dominance will be in for a rude awakening. She’ll use this as fuel to get better, and she’ll channel the anger and go to another level.”

The Bears hung tough during the relay, and Medina, in another display of heart, managed to hold off Arizona’s fast-closing Marshi Smith to take third place by 0.03 second. It was an utterly impressive effort, but when the final scores were posted, Cal had lost out to Stanford for fifth place by a mere point and a half.

Disappointed at first, McKeever was nonetheless heartened by the way Coughlin responded to her stunning defeat—and by the message it sent to the other swimmers. “Everyone has to deal with disappointment,” McKeever said in her postmeet address to the team. “It’s how you choose to bounce back from it that’s important. And Natalie’s way of dealing with her disappointment told you everything you need to know about her. As far as our team goals, we fell just short, and now I hope you’ll give Whitney and me the license to push you even harder.”

Different emotions swirled through McKeever’s head in the hours after the meet. She was angry that Stanford’s Tara Kirk, winner of both breaststroke events, had been voted by a panel of coaches in College Station as the NCAA Swimmer of the Year—the first time Coughlin had failed to win the award. She felt guilty that she’d contributed to Coughlin’s defeat in the 200 back, having introduced some new Pilates principles and tinkered with the swimmer’s technique—including the addition of a sideways component to her backstroke kick—so close to NCAAs. Hite, too, questioned his own culpability, having pushed her to do the 800 free relay.

Coughlin, however, was already over it. After having set the American record to start the relay, she said to McKeever, “See, this is a sign—I’m a 100 free swimmer, not a 200 back swimmer”—a reference to the looming decision about which event she’d swim at the Olympic Trials. When she walked past the Georgia swimmers, one of them, in reference to Coughlin’s having broken Joyce’s 100 free record, said, laughing, “You’ve got to stop doing this to us.”

“I didn’t do anything this time,” the smiling Coughlin said, explaining that she’d produced a faster time than Joyce’s during the Stanford meet.

With that, Coughlin left the natatorium and, along with Palsson, walked to a bar called the Salty Dog. It was teeming with agents and sponsors, all of whom were eager to curry the favor of the star swimmer who was celebrating the end of one of the greatest careers any college athlete had ever enjoyed. Palsson later joked to McKeever that she had “saved Coughlin from signing an exclusive apparel deal with Dolfin swimwear—for $2.”

As she soaked up the festive atmosphere, Coughlin noticed that failing to win the 200 back wasn’t bothering her in the least.

Losing was something she didn’t plan on experiencing again for a long while.

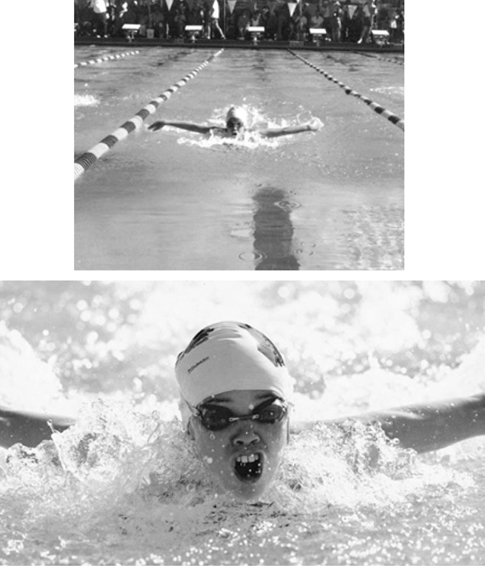

Butterfly anyone?

Young blue and gold.

Nat on her first travel team.

Terrapin teen.

The trophy is as big as Natalie.

Decorating shirts at training camp.

Natalie and Teri buying diamonds in Athens.

Natalie and boyfriend Ethan Hall.

Teri and Nat on a gold-medal night in Athens.

The Today crew giving Natalie a birthday cake.

Ann Curry and Natalie on the Today show.