EVERYTHING YOU WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT ECONOMIC POLICY

Daniel J. Mitchell

This chapter covers something that should normally fill an entire textbook. We are going to explore the entire history of economics as it relates to public policy. Out of necessity, then, we are going to touch on lots of issues and focus on only the most important implications.

Let me start by explaining a little bit about economic growth, because that is really what this discussion is all about. If you want to know what causes economic growth, there is a consensus among economists. Everyone agrees that the way to get economic growth is through the two factors of production: capital and labor. If you want more economic output in your economy and you want people to have higher living standards, you really have only a handful of options: you can provide more labor to the economy or more capital to the economy, or you can utilize the existing labor or capital more efficiently. But that’s it. There are no other factors of production. Everything that you think might lead to economic growth is in some way tied to those two factors of production.

But what’s important is how you mix those factors of production, and this is where government policy enters into the discussion. Capital and labor are like two ingredients; think about it as if you are making a cake. Who is the chef? How do those two ingredients—capital and labor—get mixed together? Is your chef the private sector, broadly speaking? Are you relying on people like Steve Jobs to be the chef who’s mixing the capital and labor together? Or are you relying on the political class to do it? Are you relying on central planners in Washington? Are you relying on politicians in a national capital? Who is the person who is actually mixing the capital and labor together? Finally, what are the implications of those decisions for economic prosperity? This is the theme of this chapter. We will be figuring out the best way—from a fiscal policy perspective—to ensure the maximum economic output for the given amounts and efficiency levels of capital and labor that are in the economy.

This discussion matters, because economic growth over time makes a big difference in the prosperity of your people. If your economy grows at 7 percent per year, you will double your GDP in ten years. If your economy grows at 1 percent per year, you will double your GDP in seventy years. If you look at the high-growth, “tiger” economies that grow between 5 and 7 percent per year (i.e., some of the Baltic nations like Estonia, Ireland in the 1990s, or Hong Kong over the past fifty to sixty years), you can see by looking at their long-run data that these countries were, within at least our parents’ lifetimes, very poor jurisdictions. However, they became much more prosperous because they managed to have sustained, rapid rates of economic growth for multiyear periods. On the other hand, if you look at some of the stagnating European economies that are in trouble, you will see that they have had between 0 and 2 percent growth for a period of several decades. Perhaps they are still growing, but they are falling behind compared with the rest of the world.

If I were to choose one thing for you to take from this chapter and to remember when evaluating public policy, it would be that long-term trend lines are critical. If an economy is growing at only 1 percent per year over the long run, then regardless of where that economy starts, it will eventually fall behind a country that is growing at between 4 and 6 percent per year. Conversely, if one country starts out richer than the other and has between 4 and 6 percent growth, while the other country has only 1 percent growth, then that country with 1 percent growth is going to fall further and further behind. Another way to think about this is in terms of your own household. Imagine how much better off you are (at least if you’re the typical case) than your grandparents, and how much better off your grandparents were than their grandparents before them. That is all simply a function of how much economic growth there is in a society.

Just by way of background, the United States (for the last one hundred-plus years) has been averaging about 3 percent real growth. (What do I mean by “real growth”? It’s “real” growth in the sense that it is adjusted for inflation. We might have five or ten times as much income as our grandparents, but that number is in nominal dollars. We really want to measure in “real” dollars, because that actually captures things we want to know: how much more purchasing power we have compared with our ancestors, what the living standards are for the average American today versus thirty years ago, etc.) We have had this adjusted-for-inflation 3 percent economic growth going back to about 1870. If you chart the trend line with actual economic growth, the actual economic growth always oscillates around that 3 percent line.

Therefore, the key question is whether or not we could be doing something to get more of the 5 percent–type growth that you see in Hong Kong or Singapore. Also, are there things that we should be doing to avoid the 1 percent growth that you get in a country like Italy? Much of my analysis is centered on these questions. What is the role of public policy in determining why some countries have faster economic growth and better economic performance than other countries?

THE FIVE FACTORS THAT DETERMINE PROSPERITY

The best way to start answering these questions is to look at the different indexes of economic freedom. The Fraser Institute in Canada publishes something called the Economic Freedom of the World Index, my old employers at the Heritage Foundation publish something called the Index of Economic Freedom, and you also have the Global Competitiveness Report from the World Economic Forum. If you look at all of these different measures, you will find that they are very similar. In fact, you can actually break down the building blocks of economic prosperity into five basic categories, and they are: rule of law, trade, regulation, monetary policy, and fiscal policy. I am a fiscal policy economist, so my analysis will mostly focus on the role of taxes and spending. But if you look at these indexes, fiscal policy is only 20 percent of a nation’s “grade.” All of these five categories, roughly speaking, are responsible for 20 percent of how a nation performs economically.

The rule of law doesn’t just refer to “the rule of law” normally understood. It also refers to property rights, the legal system, the presence of corruption versus honest government, etc. There are a whole series of institutional structures that, in some sense, serve as the foundation for an economy. If, for example, you have basically honest rule of law, legal systems, court structure, honest policing, and non-corrupt government, and the citizenry doesn’t have to pay bribes to get things done, etc., then you can build a house of economic policy upon this foundation. But if you don’t get that foundation right, it doesn’t matter what sort of house you build, because the foundation isn’t going to be very strong. When you think about, for instance, why so many countries in the developing world are staying poor, it is not because they have big, bloated governments. It is not because they have heavy regulation. The real problem in the developing world is that they don’t have the right institutions.

To think about this in more detail, remember the two major ingredients that give us economic growth: capital and labor. People put capital to work in the economy because they expect deferred benefits. When you invest, generally speaking, you are not making money in the first year. You are hoping to make money down the road. But how likely are you to invest in an economy where you can’t trust the institutions of government to treat you fairly? The main problem in the developing world is that the rule of law, property rights, and honest government are usually what is missing. We are lucky in the Western world that even the big, high-tax European welfare states, for the most part, all still satisfy these basic conditions.

Let’s now look at monetary policy, trade policy, regulation, and fiscal policy. Let’s take monetary policy first, because it is the area in which governments are most likely to throw an economy off the tracks. In fact, you will almost always find monetary policy somehow involved when a major dislocation occurs. If you look at some of the big downturns in our economy’s history—the Great Depression, the 1970s, the recent financial crisis—you will almost always find a situation where the Federal Reserve engaged in a boom-bust policy; it initially had a period of too much monetary creation (in other words, creating too much liquidity in the economy), and then, when it realized that it had made a mistake, it pulled back. Unfortunately, the very act of creating too much money inevitably means that it has to pull back and, in effect, bake into the cake some sort of economic dislocation. This dislocation can take the form of a financial crisis, 1970s-style stagflation, something like the Great Depression, etc.

Note that I am not implying there exists one single explanation for these issues at any time. In the Great Depression, for instance, monetary policy may very well have been a triggering factor, but protectionism with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, Hoover’s raising of the income tax rates from 25 percent to 63 percent, a doubling of the burden of federal spending, and all sorts of other government interventions were also important. Anytime that you are looking at a period in our economic history, it is important to keep in mind that you always have those five big factors, and each of those big factors is responsible for 20 percent of a nation’s economic performance.

It is also important to note that monetary policy isn’t noticed when it is going well, and neither is the rule of law. Monetary policy is simply something in the background of an economy, allowing it to function smoothly. If money and purchasing power are stable, and there are no efforts by the politicians to tinker with and use monetary policy for short-term “goosing” of the economy, you don’t notice it. In the same way, you don’t notice honest, sound government and rule of law; it just gives you an environment in which you can function. You notice if you’re in Argentina and inflation is 30 percent, or if you were in Zimbabwe during the hyperinflation. It is under these circumstances that you actually notice monetary policy. Similarly, if you are in a developing country where you can’t open a business without paying bribes to ten different people or ten different departments of government, then you will also notice that the rule of law is missing. If you are an investor and the government expropriates your property, and you have no access to an honest court system, then you notice that the rule of law isn’t there. But the rule of law is the foundation; you ideally never notice it when it’s being done right. Monetary policy is similar. It is like the “oil in the engine” of the economy; you notice monetary policy only if all of a sudden your engine freezes up and you realize that you have a big problem.

Let’s now talk a little about trade. This is another area where there is definitely a consensus. Almost everybody today (with only a few exceptions) understands that free trade is a good idea. All the way back to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (and even before then), there existed the notion that the bigger a market is, the more people are able to specialize, allowing us to trade with one another and become richer as a result. Let’s be very simplistic about it. Imagine if every one of us were responsible for growing our own food, producing our own clothing, and building our own house. We would obviously be a lot poorer, because none of us could be good at all of those things. We would not able to specialize and utilize the efficient allocation of labor and capital on our own. This is why trade is a very good thing.

It used to be that governments were very protectionist, especially in the pre–World War II era; one of the big factors in the Great Depression was protectionism with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. But the notion that free trade as an economic policy is a very good idea also has been around for a long time. Adam Smith wrote his Wealth of Nations back in 1776, but it took a while for that to seep into the political system and the consciousness of policy makers. They began to understand that protectionism necessarily made an economy poorer, and free trade began to take off, first with England as an island trading nation. Then, almost everyone backslid with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff and other protectionist initiatives around the world. After World War II, though, there was a very conscious decision on the part of policy makers. They saw how world trade collapsed by about two-thirds with the protectionism of the 1930s. Of course, there was a depression, so that would have necessarily reduced world trade as well, but the policy makers still learned a very big lesson: when you put protectionism in place, you are going to make your economy poorer.

So this is yet another area where there has definitely been a consensus. For the most part, I think there is a consensus that inflation is a bad idea and that the rule of law is a good idea, so these are some areas where the consensus is that we should move government out of the way, allowing people to trade freely with one another and allowing economies to focus on the areas where they are most efficient. The logic of trade, and the logic of free trade between nations, to be more specific, is the same as the logic for free trade between South Carolina and North Carolina. The argument for this type of free trade is the exact same argument for free trade between the United States and Canada. Or it’s the exact same argument for free trade between you and the local supermarket. In the end, you do not want government hindering people in the economy—whether it’s labor, consumers, or capitalists. You do not want the government hindering people from making the most efficient and effective decision possible for improving their living standards. Trade, in the end, is a big success story.

Let’s look now at the last two issues, where the consensus isn’t quite as strong. Consider the issue of regulation. The simple way of thinking about regulation is as the area where the government steps in to allegedly correct a market failure, or to protect some sort of health and safety goal. A market failure would be something like pollution. If there is no regulation, and I set up some sort of chemical factory to produce something, I might, if I was not a very ethical person, decide to dump some toxic chemicals into the river that runs behind my factory. In theory, and in the era before regulation, the tort system protects against this, because people who live downstream and are damaged by the pollution will go to court. But the tort system was viewed as an inefficient way of doing those things, and so we began to address such things through regulation. In addition, you also have regulation for things like basic safety. You create “school zones,” and ask important questions: Are you going to have a speed limit in front of the school zone? If you’re going to have a speed limit, what is it going to be? Is it going to be five miles per hour, fifty miles per hour, or one hundred miles per hour? These are the decisions that have to be made when looking at the regulatory apparatus.

One of the most common things that you should have is cost-benefit analysis. This sounds very simple. And it is, of course, actually a simple concept. But how does it actually work? That’s where things get more challenging.

Everyone (presumably) agrees that there should be speed limits. I gave the example of a school zone, but let’s talk about an interstate highway. There are about 30,000 deaths on the road every year, and let’s assume that thousands of those deaths are caused by accidents on interstate highways. We could eliminate all of those auto fatalities by having national speed limits of five miles per hour. But would that make sense? Even though there’s a clear benefit (we would save thousands of lives every year by having five-mile-per-hour national speed limits), we don’t do that because we recognize that the regulation has a very high cost. Transportation between places would take forever, and there are all sorts of additional costs that the regulation would impose upon the economy.

So instead each state looks at its traffic density, driving patterns, enforcement capabilities, etc., and makes a cost-benefit trade-off. The same procedure exists in other areas as well. For example, there is a division of the Office of Management and Budget in Washington called the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), and one of its responsibilities is to be the regulatory overseer of all the different regulations proposed by different government agencies. One of the things that OIRA looks for is the cost-benefit analysis. Agencies say: “We want to do X. We want a national speed limit of five miles per hour because our job is to reduce highway fatalities.” But an agency like OIRA acts as the adult with oversight in the conversation, saying: “Well, wait. You guys are looking at only one side of the equation. You’re looking at the reduction in highway fatalities, and we have to consider the overall economy.” That’s how, at least in theory, regulatory decisions get made in Washington.

But these decisions still become very controversial, because not everyone makes the same assessments of the costs and benefits. For example, another thing that you may have to add to the equation is the implications of slower economic growth for the health and longevity of your population. There are very clear relationships in economic literature between the income of a country and the life span of its people. If you are in a very poor nation, your life span could be under fifty years. But if you are in a very wealthy nation, life spans are approaching eighty years. Therefore, if you pass a very expensive regulation that harms the economy, even though the intended goal of the regulation is to save a certain number of lives, a potentially resulting drop in GDP can have counterbalancing negative effects. In some of the academic literature, there are data showing that a $13 million drop in economic output causes one premature death, as a relationship over time, through an economy. Most government regulations are intended to prevent premature deaths. We want to limit the sulfur dioxide that comes out of certain coal plants, for instance, because we think that this regulation will prevent premature deaths caused by poor health or other harmful consequences. But if you are reducing deaths at a high cost, and $13 million less of economic output leads to a premature death according to economic research, you have to somehow balance these two factors and decide what your sacrifices will be in terms of economic output and the implications of that same sacrifice.

In summation, the way to think about regulation is that there are always trade-offs. You are never going to completely reduce risk in a society. Every time that you wake up and cross the street, drive a car, or fly in a plane, you always face risk. For example, how many people know that peanut butter is a carcinogen that the federal government measures? Every peanut butter sandwich you eat increases, in some infinitesimal way, your risk of cancer. Obviously, it increases your risk a lot less than every cigarette would, but that’s what regulatory analysis is all about; it’s very complex. In theory, though, it should be very science-oriented, and you should be trying to figure out the costs and benefits.

That’s the way it should work. Oftentimes, however, we get regulations that arguably have no economic benefit. State governments, for example, have passed laws that say you can’t be a florist unless you pass a government exam, or you can’t be an interior decorator without a government license. There are even regulations in different states for funeral homes that require you to purchase caskets to get cremated in. Of course, that’s mostly because the casket-building industry will lobby the state legislators to put in this requirement, even though cremations clearly do not require the purchasing of a casket. In situations like this, you might have regulatory burdens imposed even though there is no measurable benefit. Therefore, when I mention how government regulation should work, keep in mind that this is in a theoretical world. It is also important to consider how regulations actually work in the real world. You will see, in terms of the real world of regulation, that different industries will often use the process to try to obtain unearned wealth. This is the theory that the late George Stigler, a Nobel Prize winner at the University of Chicago, entitled “regulatory capture.” Regulatory capture exists when the government creates a regulatory agency that is supposed to do certain good things for the economy, but over time the regulated industry figures out how to use lobbying resources and take effective control of the regulatory body. Once this happens, the regulatory body will actually pass rules that help the big, powerful companies in the industry.

That is, in reality, what you often see. Regulations wind up benefiting big companies at the expense of small companies. Why is that? If you are a big company, you already have a very big legal staff, accounting staff, compliance staff, etc. If there’s some new regulation that will cost every firm $10 million, it might be an asterisk in the budget of a large corporation. For small competitors, on the other hand, $10 million might put them out of business. In summation, how regulation works in the real world is often different than in theory.

I should also say that regulation is not just about economics. Hang gliding, for example, is a very hazardous hobby to undertake. I suppose if you want to be an actuary or accountant, you could point to how little of an effect hang gliding has on our economy versus how many deaths it causes per year. A regulator might decide, therefore, to ban hang gliding on the premise of saving lives without sacrificing a noticeable amount of economic output. But under this scenario, you have to decide whether other things should be a part of your calculation, namely human liberty, freedom, and the ability to decide for yourself. If you want to go out and surf twenty-foot waves in California, or become a skin diver and take the risk of a shark attack, should you have that choice? There are inherently dangerous activities, and the question is whether or not people should have the freedom and liberty to engage in those activities. In theory, if you just did a completely dispassionate cost-benefit analysis, you might decide that people shouldn’t be allowed to take any risks. For example, in New York City, Mayor Bloomberg wants to ban restaurants from having salt. He also recently made a new decision that stops companies or restaurants from contributing food to homeless shelters if the fat and salt are above a certain level. Isn’t that wonderful? He would rather have homeless people go hungry than, heaven forbid, there be a little bit too much salt in their food. These are some of the different issues that you raise when you look at regulation and how it works on the economy.

THE ECONOMICS OF FISCAL POLICY

Let’s now shift to fiscal issues. When I say “fiscal issues,” I am really talking about three different things, and I’ll break them down as we continue with this part of the discussion. We are talking about deficits and debt, government spending, and the tax code.

But before I break down those three things, let’s walk through a very abbreviated fiscal history of the United States. Basically, from the founding of our country through the first 130 to 170 years (depending on how you want to calculate it), we had limited government. This is what our Founders envisioned. If you look at the Constitution, and specifically at Article I, Section VIII, you will read the enumerated powers of the federal government. Article I, Section VIII gives the federal government, and more specifically Congress, the power to levy and collect taxes, to do patent and copyright laws, to build post roads, to maintain a national defense, etc. There are about twenty specific clauses outlining the powers of Congress and the federal government.

Powers that you will not find in Article I, Section VIII, include a Department of Agriculture, a Department of Energy, a Department of Education, Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, etc. In fact, most of what the federal government does today would probably cause the Founding Fathers to roll over in their graves, because Article I, Section VIII is very clear in defining exactly what the federal government is authorized to do. The rest of the Constitution is also pretty clear; if the federal government is not specifically given the authority or permission to do something, it is not the business of the federal government.

That system pretty much operated through the 1700s and 1800s and into the 1900s. Probably the first hiccup was the Progressive Era. The Progressive Era (late 1800s to early 1900s) was characterized primarily by a change in the view of the role of government. If you read the Federalist Papers, or any of the early writings, the Founders very clearly believed that government was a dangerous thing. The purpose, originally, of the Articles of Confederation, and later of the Constitution, was to figure out how to balance the necessity of a government with distrust of government. The purpose of the Constitution was to figure out how to fence in government and guarantee individual rights so that people wouldn’t have to worry about this dangerous entity that throughout the history of the world was associated with oppression, tyranny, and abuse. The Founding Fathers took this idea that government is a dangerous and risky, though necessary, thing, and put in place this system that was designed to limit government.

What characterized the Progressive Era was the notion that government is not a dangerous thing that we should curtail, but a wonderful force for good. If we unchain government from the Constitution, we can therefore have government go out and start doing things to make the world a more wonderful place. Something that coincided with the Progressive Era that basically enabled the process to begin was the adoption of the Sixteenth Amendment, which made income tax permissible.

We actually did have an income tax between 1863 and 1872 (it came into place as part of financing the North in the Civil War). We then had an income tax adopted in 1894, but an 1895 Supreme Court decision said that the power to tax income was not authorized by the Constitution. Article I, Section VIII does give government the ability to levy and collect taxes, but they had to be apportioned among the states, and obviously it’s very difficult to design an income tax that collects an equal per capita amount from each state. At the time, that decision pretty much killed the income tax.

I should note that I am an economist, not a lawyer, so the situation is probably much more complicated than my analysis. But what essentially happened is that the politicians then put forth a proposed constitutional amendment, which took two-thirds of both the House and the Senate to get out of Congress, and in 1913 was ratified by three-fourths of the states. The result is that what started out as a fourteen-page law with one two-page tax form with a top tax rate of 7 percent has morphed into the lovely Internal Revenue Code that we all know and love today. That was a very important point in time for the fiscal and economic history of the United States.

The next significant thing was the New Deal. The New Deal was when we began to put in place some of the welfare state, and particularly welfare and Social Security. After that was the Great Society, and the Great Society was when we got Medicare and Medicaid. This was during the 1960s, when we also began the so-called War on Poverty.

To briefly digress, it’s important to understand that these programs have not been very successful. The poverty rate was falling prior to the enactment of Great Society programs in the 1960s. Once the new welfare programs were implemented, however, that progress came to a halt and the poverty rate since then has hovered between 11 percent and 15 percent of the population.

Returning to fiscal history, the next thing that happened was that we had a twenty-year period between 1980 and the end of the century when under both Reagan and Clinton there was a consensus that government was too big and that the burden of government spending should shrink. By and large, policy did move in that direction during the Reagan and Clinton years.

But then we have this century, the Bush-Obama years, which are basically the opposite of the Reagan-Clinton years, because we have seen a fairly constant expansion in the burden of government spending. Indeed, all of the progress that was made during the Reagan-Clinton years has been reversed.

Keep in mind that this is the one area where there is certainly not a consensus. Perhaps there was a consensus during the Reagan-Clinton years about shrinking the burden of government, and then maybe there was a consensus (at least in Washington among politicians) to increase the burden of government during the Bush-Obama years, but a lot of the fiscal fights that we are now seeing in Washington reflect a lack of contemporary consensus. People are fighting over what the proper role, size, and scope of the federal government should be. And not only are we looking at history, we are also considering the future. Everyone is aware of the fact that, because of the demographics of the population (the baby boom generation is beginning to retire) and the structure of the entitlement programs, the very same problems that we are looking at in Greece today are going to happen to the United States unless something changes.

Let’s now look at these three big fiscal policy issues: deficits, spending, and taxes. (Just by definition, deficits are the annual borrowing we do to finance government. We are spending more than we collect in revenue, and the annual borrowing is our “deficit.” “Debt” is simply the collection of all the past deficits, added up.)

We now have a deficit that is roughly 6 percent of GDP. Calculating our debt is a little more complicated, because there are actually several ways of measuring the national debt. There is the gross national debt, publicly held debt, and unfunded liabilities (which is more of an actuarial measure). Simply stated, we have an annual deficit of 6 percent of GDP and a gross national debt of more than 100 percent of GDP. Our publicly held debt is around 75 percent of GDP. The unfunded liabilities of the entitlement programs amounts to nearly 400 or 500 percent of GDP. (This is actually very hard to measure because you have to do calculations of present value, and make an assumption on the interest rate in that calculation. As a result, it is a very amorphous and fuzzy way of trying to define the national debt. In the end, it is simply a measure of how much we have promised to spend in the future versus how much we plan to collect in revenue.)

When discussing deficits and debt, the number one thing that I want to get across to people is that deficits and debt are not actually the problem; they are merely the symptom of the real problem. The problem that we have is the burden of government spending. Government spending, regardless of how revenue is collected, is what diverts resources from the productive sector of the economy. As the level of government spending rises, the politicians increasingly become the chefs who mix the capital and the labor in the economy. Consequently, there are fewer resources in the private sector for the entrepreneurs to mix the capital and the labor.

Sometimes, people will disagree with this assessment because they believe deficits lead to high interest rates. This is because interest rates are the price of borrowing. As the government borrows more and more, traditional supply-demand analysis dictates that there will be more upward pressure on the price of borrowing. Because the price of borrowing is the interest rate, this analysis would indicate that deficits lead to high interest rates.

I’m an economist, so I believe in supply and demand curves, and I agree with that analysis. But here is the key thing: just as it is very interesting and challenging to measure costs and benefits when talking about regulation, it is very interesting and challenging to measure the impact of government borrowing on the price of borrowing. Here is the example that I often use: I sometimes go to McDonald’s and buy McChicken sandwiches, each for a dollar. Sometimes, I may even purchase up to three McChicken sandwiches at a time. In theory, then, my purchase of McChicken sandwiches at McDonald’s has increased the demand for McChicken sandwiches, which should put upward pressure on the price. But if my purchases of McChicken sandwiches are just a tiny drop of water in the “lake of demand” for McChicken sandwiches, then it is going to be very difficult to measure whether my personal purchases are having any effect on the price of McChicken sandwiches. Likewise, in a world capital market of tens of trillions of dollars, even very large amounts of borrowing by the U.S. government might not be enough to have a significant effect on interest rates.

At this point, the smart people reading this chapter will point to Greece. Interest rates in Greece have increased dramatically since its economy’s crisis. But the reason that interest rates in Greece have shot up is not the supply and demand of credit in the global economy. In reality, it is an assessment on the part of international investors that the Greek government is not trustworthy; it may not be able to pay back its loans. That is what is driving the interest rate increases in places like Greece. That is why we are seeing interest rates on government debt for some European nations begin to climb. That is why, historically, there are relatively high interest rates on government debt for developing countries, because these are the countries that have a greater history or likelihood of default. So it is the probability of default that is driving the higher interest rates, not the demand of government to borrow money. In fact, we have more government debt in the world today than ever before, and yet global interest rates are very low.

Of course, as with anything in economics, you always want to look at more than one factor. Interest rates are very low not in spite of government borrowing, but because the overall world economy is not that strong. There is a lot of capital in the world economy, but there is not that much demand for private investment, because governments are making policy mistakes that make it less likely that you can earn a profit by investing. If there are lots of savings and capital being provided (especially by the East Asian economies), but little being demanded, that is going to affect the world interest rate. That is why the cost of capital right now is very low even though the demand by governments to borrow is at record levels. To summarize, I do think that government borrowing puts upward pressure on interest rates, but I think that the reason some countries have very high interest costs is all about their risk of default, not the supply and demand of capital available for government borrowing.

I should probably note that if you had someone from the Congressional Budget Office writing this chapter, he would make a slightly different argument. The CBO would argue that even if interest rates aren’t high, government borrowing has a very negative effect on the economy because it diverts capital from private to public uses. I wouldn’t disagree with that, but the CBO analysis also acts as if this is only thing that matters. If you look at some of the Congressional Budget Office research, it will actually argue that higher tax rates are good for the economy. Why does the CBO argue that higher tax rates are good for the economy? Its argument supposes that if you have higher tax rates, they will lead to less government borrowing (or maybe even a government surplus), and that this means there is going to be more capital for the private sector, leading to more economic growth.

The CBO makes some sound arguments, but to assume that tax rates won’t discourage economic growth is a mistake. I also think that the CBO is a little naive if it thinks that after raising tax rates, politicians will actually use the money to reduce deficits instead of just spending it (we will get to this a little later in the discussion).

There are many problems with the CBO’s argument, but there is also some truth to it. Obviously, at some level, too much government borrowing will get an economy into trouble. Again, however, I want to stress what I said before: it is the diversion of money from the productive sector of the economy by government spending that—whether financed by borrowing or taxes—is what we should worry about.

One last thing about deficits and debt. There is some very influential research, and there are many follow-up studies associated with it, arguing that 90 percent of GDP is a critical level. Government debt, beyond that level, begins to have very negative consequences for economic growth. That analysis is based on cross-country data, aggregated together. I personally do not think that this is a magic number. Japan has government debt of 200 percent of GDP, and it hasn’t hit the brick wall yet. I think that the Japanese will at some point, because of their demographics, but they have 200 percent of GDP as debt and they are still surviving. After World War II, we had 125 percent GDP government debt and it did not stop us from growing. England was over 200 percent GDP in debt after World War II and it did not stop the country from growing. On the other hand, Spain and Portugal have already gotten into trouble and required bailouts when they had government debt of only about 65 or 70 percent of GDP. So 90 percent of GDP might be an average, but you must also consider the characteristics of the country. Some countries will get into trouble at much lower levels; I can guarantee that Argentina would default well before it got to 90 percent GDP, whereas a country like Japan might survive just fine until it got to 300 percent GDP. It’s hard to know.

Let’s now shift to spending. I’ve already mentioned that government spending is the most important variable to consider, since it is government spending that diverts resources from the private sector. As with deficits and debt, there are multiple ways to measure the cost of government spending. There is the “diversion cost” (which, as I mentioned, is the fact that labor and capital are being allocated by politicians in Washington instead of entrepreneurs in the private sector), and there is the “extraction cost” (which is simply the measure of how government spending is financed, via taxes and borrowing). They both have specific negative costs on your economy, but there are other “micro-effects” of government spending as well.

The extraction and diversion costs apply to every single penny of government spending, but it is important to realize that not all government spending is created equal. Public finance economists break down government spending into categories. First, there is basic rule of law and institutional spending (providing the rule of law, the court system, etc.). Those types of spending are actually associated with better economic performance, because government is creating the environment that allows “chefs” in the private sector to mix labor and capital without having to worry about theft, expropriation, invasion, and the like. These core public goods (sound institutions, rule of law) are associated with better economic performance.

Another category is physical and human capital. What are physical and human capital? Roads are an example of physical capital; education is an example of human capital. We need to have a good infrastructure network and an educated workforce in order to achieve a healthy and growing economy.

The problem, though, is that governments usually do these things very inefficiently. Sure, the interstate highway system gave us a good return on our money, but building “bridges to nowhere” gives us a very bad return on our dollars. What do governments tend to do more of today? They tend to do more bridges to nowhere, earmarks, and pork-barrel spending. Thus, even though capital spending can be associated with better economic performance, physical capital spending can also be associated with worse economic performance if politicians misuse their appropriations authority.

Human capital is another example. We spend more per capita than any other country in the world on education. Yet if you measure all the industrialized economies in the world, we have one of the worst performances. It turns out that our monopoly-structured government school system is extraordinarily expensive and gets us a very low rate of return in exchange. If you look at countries like the Netherlands, Germany, and Sweden that have school choice systems, they spend a lot less and get much better results for the amount of money spent.

This is true for anything you do. Depending on how good a negotiator you are, you might go out and buy a car for a great price, or you might get ripped off. The problem with the way that the government is providing physical and human capital is that we, the taxpayers, are getting ripped off. We are paying a lot and getting very poor results. Even though we know that physical and human capital spending are very important for an economy, we should always ask whether it is important that they be provided by the inefficient system of our government.

There are two other types of government outlays: transfer spending and consumption spending.

Most of the academic research indicates that such spending is negatively associated with economic performance, because this is the kind of spending that tells people not to work as much (since the government will replace that income), and not to save or invest as much (since the government will take care of you). This is the type of spending that has terrible inefficiency and systematically encourages dependency. Unfortunately, this is actually the vast majority of what the federal government does.

The government also spends on things like regulatory agencies, which can be deceptively expensive for our economy. Our budget for the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), for instance, is about $1.5 billion dollars. But the cost imposed on the private sector by just one law alone, Sarbanes-Oxley, was approximately the same amount, and it applied to only one segment of the business community. Therefore, the amount of money that we actually spend on a regulatory agency is trivial when compared with the cost that the regulatory agency might be imposing on the overall economy. But, of course, remember our discussion on regulation; you have to figure out if the regulation is efficient or inefficient by looking at the cost-benefit structure.

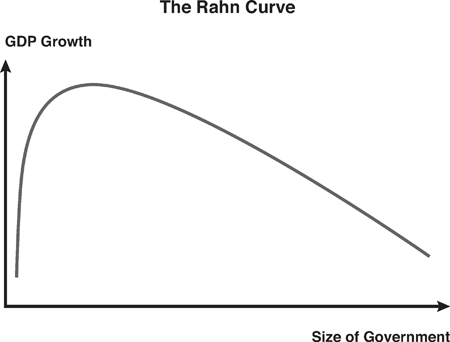

Considering these issues of government spending in aggregate, it is important to consider the Rahn Curve (see below). The Rahn Curve is the spending version of the Laffer Curve; it argues that if government is not spending anything (isn’t providing rule of law, infrastructure, or human and physical capital), then the economy will be very weak. In essence, you need some government spending in order to enable your economy to grow. But when government gets too big, the curve bends downward and government growth is associated with weaker economic performance. The research shows that once total government spending in an economy exceeds approximately 20 percent of GDP, it begins to be negatively related to prosperity. And today, federal, state, and local spending consumes nearly 40 percent of GDP. (I actually think that the cutoff for government spending is empirically closer to 10 percent of GDP, but we don’t have space to get into that.)

Let’s now discuss Keynesianism and stimulus. Basically, the theory of Keynesianism is that you borrow money from some people and give it to other people. Here is a question to determine whether or not any of you are qualified to be a member of Congress: Who thinks that there is more money in the economy when that happens?

Keynesianism is the theory that taking money from the right pocket of your economy and putting it into the left pocket of your economy makes you richer as a result. It doesn’t work. It didn’t work for Hoover or Roosevelt in the 1930s, it didn’t work for Japan in the 1990s, it didn’t work for Bush in 2008, and it didn’t work for Obama in 2009. Keynesianism is simply an excuse that the politicians have come up with, I think, to enable them to do what they truly like doing, which is spending money.

Let’s now talk abut taxes. Remember the earlier discussion that not all government spending is created equal? This also applies for taxes; not all taxes are created equal. The Hong Kong flat tax, for instance, collects almost the same amount of money, as a share of GDP, as the U.S. income tax. Yet the Hong Kong flat tax is much less destructive to growth than the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. Hong Kong has a nice and simple 16 percent flat tax. The entire tax code is less than two hundred pages. The United States, by contrast, has this monstrosity of an Internal Revenue Code—74,000 pages of law and regulation, pervasive double taxation between the capital gains tax, corporate income tax, double tax on dividends, and the death tax. A single dollar of income can be taxed four different times.

Good public finance theory says that at any given amount of revenue a government wants to collect, it should collect at the lowest possible rate to achieve that amount. A government should not be double-taxing savings and investment. Every single economic theory (even socialism and Marxism) agrees on the importance of capital formation. If you don’t have capital, labor isn’t going to be productive, and that is what determines the health, prosperity, and vitality of the economy. Yet our tax system goes out of its way to penalize the provision of capital to the economy almost as if we deliberately designed a tax code to reduce our long-term growth rate.

We also have a monstrosity—a Rube Goldberg system of loopholes and exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and shelters that winds up putting industrial policy into our system. In other words, the government, through the tax code, is being the chef, trying to determine how labor and capital get allocated. That necessarily means a less dynamic and less vital economy.

If you fix all of the problems in the tax code—if you have the lowest possible rate and you get rid of the double taxation and loopholes—what do you have? You have a flat tax. Or, to be more accurate, you have a single-rate consumption-based tax system. (When public finance economists refer to consumption-based tax systems, they are really just referring to a tax system in which income is taxed only one time. This is called the “consumption-based tax system.”) The other model of taxation (which unfortunately is followed for the most part in Washington) is called the “Haig-Simons tax system,” and that is the principle that not only should you tax income, but you should also tax net worth, changes in net worth, transfers of net worth, etc. This is where much of the double taxation in the tax code exists. If you want the right type of tax system, where you collect revenue while doing the least amount of damage to the economy, a consumption-based tax system with a low rate is much better than a Haig-Simons–based system of double taxation with high rates.

This, of course, gets into issues like “fairness.” But fairness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Does fairness mean that you treat everyone equally? Or does fairness mean that you impose higher tax rates on individuals who are providing more output for the economy? There is a cost to the second definition of fairness; if you decide to go with the latter definition of fairness, it means that you are going to penalize the entrepreneurs, the people who produce the most per hour of labor they provide to the economy. They generate a much bigger amount of output. (In economics classes, that is known as the value of marginal product of labor. How productive you are per hour of work and how much wealth you can generate for an economy are what determine how much your wages are going to be in the long run.)

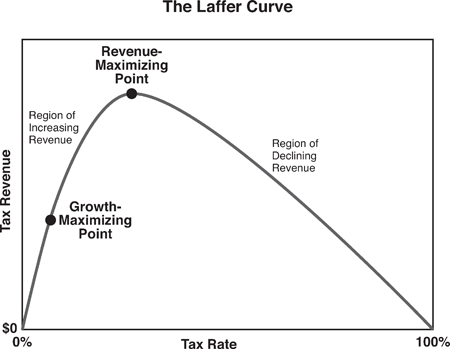

Let’s look at some specific tax issues. Earlier, I mentioned the Laffer Curve. This is simply the notion that tax rates, at some point, can become so high that they are self-defeating. Here’s the theory: at a 0 percent tax rate, the government collects nothing. At a 100 percent tax rate, the government also collects nothing. (Perhaps there are a few genetic socialists in the world who would still work and earn income even if the government took 100 percent of it, but for the most part a 100 percent tax rate would mean no revenue for government, and a 0 percent tax rate would also mean no revenue for government.) (See the Laffer Curve below.)

The real debate is over deciding which tax rate on the Laffer Curve corresponds to the revenue-maximizing point, and, more important, the growth-maximizing point. I personally do not want to maximize revenue for government, so I have never looked at the Laffer Curve and tried to find the point that gives politicians in Washington the most amount of money possible to spend. I care about the growth-maximizing tax rate. The growth-maximizing tax rate, in effect, automatically comes from the Rahn Curve and its growth-maximizing size of government. If the growth-maximizing size of government is 10 percent of GDP, for example, then you simply examine the Laffer Curve and find the least destructive way of collecting 10 percent of GDP. Or perhaps you think that the right level is 20 percent of GDP or 5 percent of GDP. Either way, your decision about what government should do and at what level government should do it should always come from the growth-maximizing point on the Rahn Curve.

If you want to honor what the Founding Fathers had in mind, then you will have a very limited central government. For much of our nation’s history, the federal government spent only about 3 percent of GDP. Most government was at the state and local levels. So you have separate decisions: How does the federal government collect revenue, and how do state and local government collect revenue? In both cases, however, you want them to decide how to collect revenue in a way that minimizes the damage to the economy.

There are still a couple of other issues that I want to touch on quickly. One is the issue of “starve the beast.” There is a big debate in Washington right now about whether taxes should be increased. We have a huge pile of red ink. You can look at the data and see that the reason we have this big pile of red ink is that government spending under Bush and Obama has exploded. If you look at taxes as a share of GDP, even without any extra tax increases, we are soon going to be above our average historical level of 18 percent of GDP. Therefore, I think that there is a very strong argument that 100 percent of the problem is on the spending side. Why on earth, then, would you want to have higher taxes?

But separate from that is the question of whether or not increasing tax rates is even capable of reducing the deficit. It turns out that when you raise taxes, you may simply encourage politicians to spend more money, making the fiscal situation worse. This is in part because the politicians spend more money, but also in part because of the Laffer Curve effects.

This is the situation in Europe. Forty or fifty years ago, the burden of government spending in Europe was similar to that in the United States. Over time, European countries kept raising taxes, and they also kept raising spending. This is why we have the “starve the beast–feed the beast” debate: Does cutting taxes reduce the size of government? During the Bush years, the answer was definitely no, so I wouldn’t want to argue strongly that “starve the beast” always works, but the other side of the argument is “feed the beast.” The evidence from Europe is clear. When European countries put in place the value-added taxes (which are their European form of a national sales tax), what happened? Before the VAT, and before the tax burden increased, there were southern European economies with medium-size government and big deficits and northern European economies with medium-size governments and small deficits. Now, they all have much higher tax burdens, they all have value-added taxes, and what do you find? You now have southern European economies with big governments and big deficits and northern European economies with big governments and small deficits. The only thing that has changed is that they have higher taxes, which only enabled, for all intents and purposes, a one-for-one trade-off of higher spending. What position you take in the “starve the beast–feed the beast” debate will say a lot about whether or not you think it is appropriate to give the politicians in Washington more revenue.

I just mentioned the value-added tax. I predict that the VAT is soon going to be a giant fight in Washington. Maybe not one year or two years from now, but somewhere in the next five to ten years, there is going to be a major fight over whether we should have this new levy. And the outcome of this battle will determine whether or not the politicians have a giant new source of revenue, as they did when they put the income tax into place in 1913. I fear another giant broad-based source of revenue would facilitate a leap to European-sized government. Whether that is a good leap or a bad leap depends on your underlying philosophy, but I personally think that it would be very unfortunate. We can certainly see what’s happening in Europe now. Why would we want to copy their fiscal policy?

But the argument for a VAT is that, on a per-dollar-raised basis, it does less damage to your economy than higher income tax rates. This is true. If you have a pessimistic view that government will inevitably get bigger and that taxes will climb, a VAT would be the least damaging way for this to happen. But you should ask whether or not giving politicians a VAT will enable them to dramatically increase the size of government and the burden of government spending. In Europe, they enacted the VATs and used them as an excuse not only to raise spending, but also to raise standard income tax rates anyway, because they had to “maintain the distribution of the tax burden,” in order to satisfy the left-wing definition of “fairness.”

In the interest of space, I will discuss one last thing. Let’s bring everything we’ve talked about—the history, the theory—all together and discuss where the political process is right now in Washington. There is basically a fight between the kind of vision proposed by Congressman Paul Ryan (the chairman of the House Budget Committee), which deals with fundamental reform of the entitlement programs, and the vision of those who oppose meaningful spending cuts and entitlement reform. If you look at the long-run forecast for the U.S. government, we are going to be Greece, plus some. Because of the demographics of an aging population, as well as the way our entitlement systems are structured, all the long-run fiscal forecasts show that government will become a far more expensive burden.

When Bill Clinton left office, the burden of federal government spending was 18.2 percent of GDP. Now, we are at 22 percent of GDP, a significant increase in the aggregate burden of government in just eleven or twelve years. Within the next several decades, as the baby boom generation fully retires, the federal government will consume approximately 40 percent of GDP (and perhaps even more, depending on which forecast you believe). Obviously, if you have a doubling in the size of government, it means that we are going to be more like Italy, France, Spain, and Greece, and that almost certainly is going to have very negative consequences on our GDP, employment levels, the amount of red ink that we have, and the type of tax system that we have.

I suppose this is a very pessimistic way to close this chapter. People who will be entering the workforce in the next couple of years face a dismal outlook. Assuming there is no reform, America will endure a period of Greek-style fiscal crisis during their prime earning years. This is why I am discussing the fight between visions. On the one hand, we have the budget prepared by House Budget Committee chairman Paul Ryan that restructures the entitlement programs. On the other hand, we have the vision of Bush and Obama of making government bigger and adding new entitlements. That vision, I think, basically puts us on a path to becoming Greece. But I want to be fair; it could also put us on the path to becoming Sweden. The northern European economies do the welfare state in a much more responsible way. So if you want a welfare state, you had better make sure that we wind up like Sweden, not like Greece. My personal fear is that our political system is much more likely to give us Greek-style results, not Swedish-style results.

But if we happen to do entitlement program reforms—block granting Medicaid to the states, restructuring Medicare so that it resembles a voucher system like what members of Congress have for their own health care, doing personal retirement accounts for Social Security as thirty-plus countries around the world have done—then this projection of ever rising costs of government spending could actually curve downward.

I will leave you with this: the most appropriate way to evaluate fiscal policy is something that I have very humbly named after myself. I call it “Mitchell’s Golden Rule.” Mitchell’s Golden Rule is very simple: government spending should grow more slowly than the private economy. Notice that I am not focusing on balancing the budget. I am not talking about deficits and debt. I am focusing on the underlying disease, not the symptom. If I go to a doctor and I have a headache, and it turns out that I have a brain tumor, I do not want the doctor to give me aspirin for my headache. I want him to deal with the tumor, because I want to actually solve the problem. Likewise, if you have an economy where the private sector is growing faster than the government, sooner or later it is a mathematical certainty that you will balance your budget, even though that should not be your first priority. Your first priority should be making sure that you have government as a small share of the economy. If those two lines are reversed, however, and government is growing faster than the private economy, sooner or later it is a mathematical certainty that you become the next Greece.

And that is really what our future is all about, because there is no way taxes can ever keep up with spending if the public sector is growing faster than the private economy. This is because the private economy is your tax base. Greece got into trouble, the rest of Europe has gotten into trouble, and the United States is on the path to trouble because we all suffer from the same problem: government has been growing faster than the private sector.

In closing, our country needs to go back to the policies under Reagan and Clinton, where those lines of private- and public-sector growth were reversed. At that time, the private economy was growing faster than the government. In my mind, that is the path to virtue.