Conclusion: Socialism Is

– The future is outside politics, the future soars above the chaos of political and social aspirations and picks out from them threads to weave into a new cloth which will provide the winding-sheet for the past and the swaddling clothes for the new born. Socialism corresponds to the Nazarene teaching in the Roman Empire.

– If one extends the parallel, the future of socialism is not an enviable one. It will remain an eternal hope.

– And in the process will develop a brilliant era of history under its blessing. The Gospels were not fulfilled and there was no need for that – but what were fulfilled were the Middle Ages, and the ages of reconstruction and the ages of revolution, and Christianity penetrated all these manifestations, participated in everything, acted as the guide and pilot. The fulfilment of socialism involves the same unexpected combination of abstract doctrine and existing fact. Life realises only that aspect of an idea that falls on favourable soil, and the soil in this case doesn’t remain a mere passive medium, but gives its sap, contributes its own elements. The new element born of the conflict between Utopias and conservatism enters life, not as one or as the other side expected it – it enters transformed, different, composed of memories and hopes, of existing things and things to be, of traditions and pledges, of belief and science … Ideals, theoretical constructions, never materialise in the shape in which they float in our minds.

Alexander Herzen, From the Other Shore (1851)1

THE CATHEDRALS OF ‘COMMUNISM’

It’s customary for critiques from the left to reproach ‘real socialism’ for its regimentation, its statism, its bureaucracy, its subordination of everything to ideology. It is assumed in this that a ‘real’ socialism would be able to dispense with these things, and dispense, moreover, with the inheritances from the past that so obviously weighed upon the Soviet project – the legacies of combined and uneven development, of Tsarist authoritarianism, of Hapsburg bureaucracy, as you will – unlikely to have any purchase on a socialist experiment attempted under the ideal, Platonic conditions of a Western, industrialized country. Unfortunately, this has never actually occurred, and one of the most striking things about the history of socialism is that a fully developed capitalist class has never once been overthrown anywhere – with, at best, its destruction at the point of Eastern bayonets in East Germany or Czechoslovakia as close as it has ever come. The bourgeoisie’s longevity, their staying power, their ability to transform their system into newer, leaner, if not necessarily fairer shapes, is way beyond what any twentieth-century socialist could possibly have expected. But in the ironic dialogues that make up his From the Other Shore, written in the aftermath of the failed French revolution of 1848, the Russian revolutionary Alexander Herzen suggested that any socialism which would finally emerge would come into being shaped by the inheritances of the past, by all the ‘petrified crap’, as Marx called it, that it should have shaken off. It would not follow any possible blueprint, but be coloured and shaped by unexpected and – if the example of the Middle Ages is to be taken seriously – exceptionally ugly forces. This could be a profoundly depressing conclusion, summed up by the Russian revolution’s transformation into a ruthless personal despotism and eventually an inept gerontocracy; or it could be otherwise. Never mind the blueprints, what could be built with what we’ve got, with the materials that come to hand?

Looking at what they did build, with the materials they had to hand, it’s hard to say that the problems with – or the virtues of – the built environment under ‘real socialism’ were the consequence of it being too ‘capitalist’, or not being socialist enough. Of course, the extreme spatial hierarchies of the jingoistic memorials, boulevards, palaces and secret policemen’s castles of high Stalinism or of Ceauşescu were grotesque, for all their occasionally compelling architectural qualities, and their claim to being in the lineage of any idea of ‘socialism’ is astonishingly tenuous. Yet the immense housing estates, however much they were a negation of the Marxist idea of the ‘self-activity of the working class’, were nothing if not egalitarian, if not a total attack on the notion of urban hierarchy, with all the architectural compositions based on the refusal to let any one object take primacy at any given time, and surrounded with a sea of completely public, free space. Meanwhile, the most ‘unique’ buildings of the era were for the most part the most public buildings: the theatres, squares, ‘wedding palaces’. The reconstruction of historic cities can be seen not so much as a wilfully reactionary project based upon a need to appeal to national nostalgia as a palliative for Russian colonialism, but a reaction to the realization that cities no longer had to undergo the process of continual rebuilding that came with rent-seeking and property speculation. And, most impressive of all, the Metro systems of the USSR or of Prague were a spectacular vindication of public space, of the transformation of the everyday, that went further than any avant-garde ever dared.

The claim that the problem was lack of ‘socialism’ in the sense of ‘self-activity’, of workers’ control,2 is also based on completely ignoring the experience of Yugoslavia, which had the most developed system of workplace democracy yet seen anywhere, and one which had a major role in the economy itself. The results, spatially, were a little more strung out, a fair bit more lively, but not fundamentally, intrinsically different from the more imaginative examples in the Soviet-dominated countries. What killed it, as with the states of the Soviet Bloc itself, was not so much bureaucracy as the International Monetary Fund, which picked off the ‘socialist countries’ as punishment for their running up of enormous debts, much as it punished non-socialist developmental regimes in Latin America and Africa for doing exactly the same thing, at exactly the same time, for exactly the same reasons. Yet while externally, for sure, ‘real socialism’ paid dearly for being integrated into the world market, whether that can always be the culprit for the successes or failures of what happened at home is less clear.

What seems to have been decisive – or what felt decisive to us, walking in and working in these spaces – was a strange ability to create impressive, socialistic public spaces with two provisos: one, a problem with mass production; and two, a problem with ‘desire’. In trying to explain the Soviet libidinal economy, the Georgian-born philosopher Keti Chukhrov claims that its problem wasn’t ‘things’ as such, but the creation of commodity fetishism.3 Food, as any visit to a Polish milk bar can still make clear, was supposed to be filling and healthy, but no more than that – cheeses would not be based on the various exciting things you could do with cheese but on the essential ‘cheesiness’ of cheese, on what makes it cheese rather than what makes it something else. Cheese ought not to have ‘attracted’ you; you ate cheese because cheese was nutritious. Similarly, housing had to cater for a situation of shortage, so what was needed was housing constructed at speed, unromantically, as a necessity. These things were catered for by a strikingly undeveloped form of mass production, which created famously shoddy goods, at least in part because of lower worker productivity and the absence of any economies of scale; it is plausible that automation and computerization could have eventually solved this, but it is an unknowable possibility. The fact remains that the very mass production which the ‘socialist countries’ should in theory have been best at was the very thing they most conspicuously failed in. But only individual commodities were mass-produced, things you could consume – food, records, clothes, cars and the industrialized housing. Conversely, the most impressive permanent spaces – the Metros, the public buildings – relied on qualities of craft and an enjoyment of surfaces that was acceptable because not commodified or commodifiable. A Metro station, theatre, bathhouse, cinema or club could not be ‘yours’, in the way that even housing could. Some might argue that this is a parody of socialism, and they’re welcome to. Economically, I can’t agree; but politically they’re emphatically correct that a democratically controlled socialism must surely have had different spatial results, with buildings and ensembles that don’t feel quite so flung in people’s faces, that are not quite so monolithic and dominating.

Today, socialism even as an idea, let alone as an allegedly developed fact, largely exists only retrospectively. Some in the early 1990s welcomed the demise of the ‘socialist camp’ (and the apparent defection of China) as a boon for the left, as now it would no longer be associated with a crumbling, dictatorial empire. It didn’t pan out like that. The current world capitalist system – particularly its ‘Atlantic’ part – is sometimes compared to the USSR in the age of stagnation, where the system is obviously bankrupt, no longer able to fulfil its promises, but carries on in a form of economic sleepwalking: 2009 as a 1989 without a rival system to fall into the arms of. Ideologically this has some truth, but economically less so – the Soviet system fell because it no longer satisfied manager or worker, and capitalism can go on for some time making a tiny minority rich and a large minority comfortable. Yet places where its virtues and stability are less clear have seen capitalism threatened for the first time in a long while. There are today countries which are officially ‘socialist’. Not only Cuba, every Western leftist’s favourite, or North Korea as a persisting nightmare, but also the Latin American ‘twenty-first-century socialism’ of Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador; at the time of writing, a similar movement of ‘twenty-first-century socialists’ has just been elected in Greece, and may have been in Spain as well by the time of publication. China, too, has seen controversial attempts to bring back the slogans and practices of Maoism, ending in the deposition and imprisonment on corruption charges of its most prominent neo-communist leader, Bo Xilai.4 Communism today may be merely the ‘relentless criticism of everything that exists’ on the part of academics, the ‘real movement that abolishes the existing state of affairs’ on the part of elective sects, or whichever other aggrandizing quote from Marx that a powerless left wants to cite to reassure itself over its own powerlessness – or it may still be something that existing social movements in power are consciously driving towards. What if the traces of socialism and of the socialist city can be found there, just as much as in protest camps, NGOs or squats?

THE THIRTY-YEAR NEP

Chinese cities actually have many of the components of the ‘real socialist’ city outlined in this book, only in a different order, with a very different history. There was Stalinist architecture, in the form of ‘gifts from the Soviet people’ like the Beijing and Shanghai exhibition centres – both once ‘Palaces of Sino-Soviet Friendship’ – and in indigenous efforts, such as the ‘Ten Great Buildings’ of post-revolutionary Beijing. These were strictly ‘national in form, socialist in content’, i.e. adaptations of Moscow models with Chinese traditional details, and can be seen in Beijing’s main railway station, the Historical Museum, the Great Hall of the People, and so forth. This Sino-Soviet style was, before the Sino-Soviet split in the early 1960s, exported back to Europe, as in the Chinese pavilion at the Zagreb Expo site, or the Chinese Embassy in Warsaw, designed by Polish architects in a style combining Frank Lloyd Wright and Old Beijing. But, here, the immediate urban past that was being rejected by Socialist Realist architects was not ‘Modernism’ as a social democratic or even communist project to technologically improve the built environment, but the combination of slum squalor and luxurious Americanized architecture in Shanghai, or the fascistic stripped classical structures favoured by the American-backed regime of Chiang Kai-shek in Nanjing. Housing under Mao was functional, undemonstrative and unspectacular, but lacked the deliberate futurity of modern architecture. When ‘Modernism’ arrived in the 1980s it was already ‘Postmodern’, and capitalist from the start. But most of the things in this book – the neo-Baroque boulevards, the micro-districts, the grand public buildings, the impressive public infrastructure, the memorials to revolution – are present and correct, only first they are assembled in a different order, and second they could be seen as part of an ongoing project.

When I spent a couple of weeks in Shanghai and Nanjing in 2010, in the year of the Shanghai Expo, I couldn’t get out of my head a theory about the People’s Republic of China, voiced most recently in Boris Groys’s intriguing, if historically nonsensical, The Communist Postscript,5 that what seems like merely the administration of capitalism by an oligarchy which is a Communist Party in nothing but name, is actually a gigantic, prolonged version of the New Economic Policy embarked upon by the Bolsheviks throughout the 1920s – the use of a dirigiste, state-planned capitalism to build up productive forces to a level where the population has gone from being poor to being reasonably comfortable, after which the Communist Party could take command of this wealth and use it for the building of full communism, something which can, after all, in ‘stage’ theory only be achieved after the development of a mature industrial capitalism.6 This is at least what Deng Xiaoping always claimed was going on, and maybe this was what Bo Xilai thought he was doing, albeit while putting his fingers in the till. And if this stage of ‘building up the productive forces’ has lasted thirty years – why not? Lenin, for instance, envisaged that the NEP would last a lot longer than the eight years it got before it was replaced by Stalin’s forced collectivization, chaotic industrialization and total suppression of private commerce. In the NEP – as in contemporary China – land remained nationalized, industry essentially state-directed, banks publicly owned, and power held firmly by the Party. Both had a high level of strikes, public discontent and debate, which coexisted with heavy censorship and bureaucracy, and the absence of organizations – like free trade unions – that are completely independent of the state. If the USSR in the 1920s was ‘socialist’ or at least moving towards socialism, then why not China? After all, in Shanghai, 80 per cent of the economy consists of state-owned enterprises.7 If we make what seems with good reason to be a rather extravagant theoretical leap, given the immense scale of worker exploitation, and see twenty-first-century China as a super-NEP, what could the future Full Communist China do with the hypercapitalist infrastructure, the gated communities, the skyscraping office blocks of Shanghai, the largest Chinese (and, in terms of ‘city proper’, largest world) city? If, as is often claimed, China is making the world’s biggest investment in green technology, then what is it going to do with all those flyovers and coal-fired power stations, or those seemingly so capitalist skyscraper skylines? Except, look at one of those skylines from on high, and sometimes you will see something strange – in between and in front of the speculative glass towers, serried ranks of mid-rise blocks of flats, a set of Khrushchevian panel blocks built at the same time as the corporate headquarters.

Shanghai is a city usually associated with Chinese neoliberalism, with its ‘opening to the West’ and the creation of a new ‘socialist’ bourgeoisie, but it has a firm revolutionary pedigree, as historically China’s foremost industrial city, as founding home of the communist movement, as centre of the abortive Chinese revolution of 1926–7, and as home of a Maoist attempt to revive the Paris Commune in 1967.8 Yet Maoism’s base was always rural, and this metropolis, built largely in the first half of the twentieth century as a colonial capital to the designs of French, British and American architects, was deliberately underdeveloped until Deng’s Bukharin-like call to ‘Get Rich!’ It is laced with elevated roads, all built over the last ten years or so, at roughly the same time, but to rather more impressive effect, as the more obviously ‘public’ Metro system – which, on the Western European model, is pleasant, functional, aesthetically forgettable. By contrast, this system of flyovers, for the purposes of private vehicles, is monstrous, dominant. The friend who is showing me round tells me of a conversation he had with a Party member, part of the CCP’s ‘New Left’, critical of the prospect of full capitalist restoration (which they see as a prospect, not a fact9). When global warming really hits, when the oil runs out, and the use of the car has to be curbed, what will the Party do with all this? Can it just ban people from driving? Will people accept it? Yes, was the reply, the Party merely lacks the will. So before I had even seen these constructions, I had in mind the idea of them cleared of the traffic which is too thick and dense even for their astonishing capaciousness, with bicycles and walkers making their way along these lofty elevated roads. They’re one of the most impressive works of engineering I’ve ever seen, for the less than impressive function of moving the private car with its internal-combustion engine from A to B – though, at least for the moment, taxis are so abundant and so cheap, sometimes equalling the levels of private cars, that to call it wholly ‘private’ feels a minor misnomer.

Khrushchevki and skyscrapers, Nanjing

After I had travelled along and under a few of them in a dazed, numb state once off the plane, the first of these flyovers that I really saw was in a working-class district in the north of the city, near Caoyang New Village, a 1950s housing development which my friend was showing to his students. The area around it was so impossibly dense, the width of its expressways so yawning, the clusters of towers so high, the Metro station toilets so abject (the PRC’s inegalitarian public convenience policy is notable here – in an area where there are likely to be Westerners present the loos are impeccable, elsewhere they’re infernal) and the crowds so massive that I simply gave up and went back to bed.

The flyovers too are hierarchical. While the flyovers in the centre have the smoothest-finished cream concrete you’re ever likely to see, in the suburbs it’s a much more standard material. They still tend to be rather dominant, but they’re not meant to be looked at, and they travel through what is still a heavily industrial landscape, with huge factories on either side of the motorway. While some flyovers are meant for spectacle, these don’t feel like they’re meant for people at all, instead inducing the feeling of being a vulnerable fleshy part of a metallic network of freight, lessened only by the all-too-human aggressive driving that is ubiquitous here. There was one horrible moment on one of these expressways where various container lorries constantly overtook each other, manoeuvring into position to the point where it seemed as if they were actually intent on crushing the pathetic little car we were in. But many of the flyovers really are meant to be seen. Near People’s Square, the former racetrack for the Europeans (‘No Dogs or Chinese’, as the sign ran), transformed after the revolution into a large public plaza, there’s some sort of flyover convention, an intersection which is less spaghetti junction and more the intestines of a terrifying mythological beast. These sorts of organic metaphors tend to come to mind here, because there’s little rationalistic or machinic about this place. The concrete itself is of the very highest grade, and there is planting running half way up the concrete pillars, an effort at civic beautification which is visible to the pedestrian more than to the driver. Presumably it is there as a gesture to ‘The Harmonious Society’, the official line of the CCP, replacing the Maoist fixation with identifying and intensifying ‘contradictions’.10 So nature intersects with technology in a non-antagonistic manner, but it’s far more like the engineers kept in mind the possibility that sooner rather than later these monuments will be obsolete, so made them pre-ruined, with picturesque vegetation creeping up them to simulate what they might look like when they’ve fallen into desuetude.

Flyovers at the Huaihai intersection, Shanghai

They also serve to frame the skyscrapers around, to delineate them, present them in their best light, to let them be seen from a contemplative distance, which gives a Futurist flash to what can often seem crushingly dense and badly made on closer inspection. Except that’s the sort of thing only noticed later on – you don’t notice the details initially. When I first saw the Huaihai intersection, I was absolutely frozen in awe, and then impressed by the fact that everyone else seemed entirely used to it, that it had become normal, just something you’d cross under on the way to work. There’s a general ability to seem completely unbothered by what feels like a bloody steamroller of gigantism and force here which is admirable, although slightly worrying. The flyovers are the main event, works of public infrastructure more impressive than the baubles on top of the towers of capital. Their forcing through areas of already huge density necessitates an extra pedestrian layer being inserted into them – there are plenty of these intersections that have pedestrian walkways running across, blue steel and glass pedways sandwiched between the roads.

You eventually reach ground level among walkways cutting across neon-lit geodesic domes, skyscrapers with searchlights cutting through the ubiquitous fog, and some rather familiar corporate logos. This massive project of state-built infrastructure is the least trumpeted of the major public works in the city. There’s the Metro, of course, with nine lines built in the time it takes to string a line from one side of Warsaw to the other, but there’s also the Magnetic Levitation train. The Maglev might be the one area where the prolonged NEP of the People’s Republic entailed doing something differently, where it put a genuinely advanced technology at the service of a public rather than private means of transport, but compared with these monuments to the hope, as right-wing hack P. J. O’Rourke puts it, that ‘1.8 billion people want a Buick’, it seems paltry indeed.

In 1989, People’s Square, before those intersections were built, was a place of assembly and protest; but it didn’t see any massacres, apparently because of the constant presence of armed forces looming over the plaza. The Shanghai authorities’ handling of the situation earned them a prominent place in government – Shanghai’s secretary, Jiang Zemin, became Party leader, and his ‘Three Represents’ became Chinese neoliberalism’s numerical successor to Mao’s ‘Four Olds’ and Deng’s ‘Four Modernizations’. The square is of course loomed over by dozens of corporate skyscrapers, but also by the far less interesting City Government building. Evidently the Party has little interest in emulating the capitalist delirium all around, instead providing something sober and bland, with perhaps a little hint of the Stalinist skyscraper style, denuded of ornament – a little like a cheaper version of the Hotel Ukrainia in Kiev. Reach the Bund, the famous boulevard where the city meets the Huangpu river, and you find many non-socialist skyscrapers, usually designed by English architects in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of the Bund’s buildings have the Red Flag flying from them, something which forces you into a minor double-take, realizing that it signifies something quite different here, or rather it does now. The Custom House’s chimes play ‘The East is Red’ on the hour. The smaller, earlier public space here is where the notorious ‘No Dogs or Chinese Allowed’ sign once stood, but it did say something very similar in more polite language, and it now has two monuments to the revolution that ended that.

One of them is typical figurative hurrah-jingoistic Socialist Realism, with a bronze flag-waver on a red-granite plinth, and aside from a couple of curious snappers, lots of whom must be provincials up for the Expo, the large crowds entirely ignore it. The adjacent Monument to the People’s Heroes, meanwhile, is completely abstract: it could be a monument to practically anything, and it could be admired by a Speer as much as a Shchusev – which doesn’t stop it being a rather powerful sculptural object, its rectitude a contrast with everything around as much as its high-rise form is a complement to it. Whether it still conveys, as intended, the Chinese people’s struggle against imperialism and capitalism is less certain.

Yet the architectural money shot, if you please, the thing that everyone in front of the Bund was taking photographs of rather than of the Bund itself (developmentalism winning an aesthetic victory over imperialism, there), was the skyline view. A clear vista like this is rare in Shanghai, because of the height of everything else and the ubiquitous smog, so when you get it it’s all the more breathtaking. This is the skyline not of Puxi, the only built-up side of the Huangpu river until the early 1990s, but of Pudong, the area that is really an entire new town which sprang up from marshland after Shanghai was designated a Special Economic Zone – something the Chinese government originally refrained from, in order not to encourage the massively uneven development that made parts of Shanghai into one of the most modern cities in the world in the 1930s while horrifying poverty stalked much of the rest of the city, and of China. That the return to fully uneven development should coincide with the notion of the Harmonious Society is one of those ironies of history.

The skyline itself as the lights come on, like the expressways at night, is a joy that only a churl couldn’t be in any way moved by, as if the Empire State Building couldn’t be enjoyed because of the Dust Bowl (some did argue that, of course). To pick out details – the giant illuminated globes, Adrian Smith’s smooth, tapering, gorgeously elegant World Financial Centre, the improbable declaration ‘I Heart Expo’ on the part of the Taiwanese Aurora company’s offices, the pulsating lights extending even to the Expo-sponsored sightseeing boats (replacing much unsightly freight) … and, in the form of the Oriental Pearl TV tower, the curious feeling, once again, that you’ve seen the future somewhere before … that the future resembles very closely the past’s idea of the future. It’s Ostankino or the Berlin Fernsehturm with an extra spiked bollock. There’s no time, evidently, to imagine a new idea of the future. The lights all come on between six and seven, but the concomitant of that is that they all go off at around midnight. The apparent reasoning behind this is derived from environmental imperatives – all that wasted electricity – but the effect is ‘OK, you’ve had your fun, now go to bed.’ The intended effect of the lights might be to present a vibrant and delirious techno city that never sleeps, but it’s hard to be the city that never sleeps when you have to get up first thing in the morning for a day of hard, hard work.

SOCIALIST REALISM WITH CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS

Architectural periodization is completely meaningless here. In Shanghai there wasn’t really a socially engaged Modernism along the lines of Berlin or Moscow in the interwar years, there was ‘Moderne’, i.e. Art Deco; and after the war Stalinist Gothick and unpretentious (but hardly Modernist) utilitarianism prevailed. Now, in the skyline, you can pick out everything from historicism to Pomo to Constructivism to Expressionism to serene Miesian Modernism, with the only logic seeming to be that rather chaotic notion of Harmony and Pluralism. There is one unacknowledged influence on the contemporary skyline, and that’s Socialist Realist, or more precisely Stalinist architecture. The one fully fledged example in central Shanghai of the full-blown Stalin style still exists and is very much in use: the former Palace of Sino-Soviet Friendship, a ‘gift from the Soviet people’ just as much as the Warsaw Palace of Culture and Science – which of course bears the Polish acronym ‘PKiN’, or ‘Peking’. China was never a satellite, though – like Yugoslavia it made its own revolution, and hence was reluctant to accept Soviet tutelage. After the Sino-Soviet split – caused, depending on what side you take, by Mao’s crazy refusal to accept what a disaster nuclear war would be (‘China will still survive!’) or by Khrushchev’s refusal to join it in anti-imperialist struggle, preferring a phone line to Kennedy when the Chinese government wasn’t even allowed a seat at the UN. Either way, the Soviet response, removing all its advisers, engineers and materiel, was quick and vindictive. The building became the Shanghai Exhibition Centre, which still holds trade fairs and the like. It displays a typically Stalinist interest in symmetry, aligned around a great central tower ‘supported’ by columns, with a tall skyscraping spire surmounting the design, as ever of such a scale as to break any previously known rules of classical proportion. Isolate the tower and it could easily be the pinnacle on the Palace of Culture and Science, with the obvious difference that there is still a communist star in place at the top.

The unexpected fact is that the style lives on, now in a peculiar alignment with Modernist-oriented planning laws. Everywhere in Shanghai’s southern suburbs are serried, identical towers, with south-facing aspects, generously proportioned windows and breathing space in between, and dressed with clearly machined ornamentation, whether the pitched roofs at the top or in the ‘brick’ coursing at the corners. It’s not the crass, appallingly planned, architecturally illiterate, Zhdanov-goes-to-Vegas Yuri Luzhkov style, but something with rather more conviction and thought behind it; it comes out of a combination of ‘market preferences’ which elsewhere would be regulated (the ubiquitous south-facing orientation), and state edicts – the pinnacles that you find on every block, and which have such an effect on the Shanghai skyline, are the result of state policy, to stop extra floors being built on top, as they were in boomtime Hong Kong. The result is a pictorial skyline, a ‘city-picture’, but it’s the result of dirigisme leading to delirium, rather than a capitalist potlatch. What it really is, is Modernist spatial planning going classicist in detail. It’s the wholly inadvertent successor to the likes of Andrei Burov’s block on the Leningradsky Prospekt, which pioneered the use of prefabricated ornament in monumental construction. Much of contemporary Shanghai is the fusion of Burov’s two preoccupations into a new architecture.

‘Top marques’ at the former Palace of Sino-Soviet Friendship, Shanghai

The block in the photograph below does this with more demented panache than any other I saw there – the sheer length and height of it, slathered in all kinds of prefabricated ‘stone’, with the particular approach coming very, very close indeed to the style of 1950s Moscow; except rather than the boulevard-and-courtyard approach, these are towers geometrically organized in parkland. It’s one of eight identical towers stretching all the way past a main road in the southern suburbs. The lower, retail block in front is part of the same tabula rasa. Not far from here, you can find red-star-topped grand archways straight out of VDNKh, or department stores decorated in high reliefs based on Klimt – the ‘Soviet’ look is one of the many put into the mincer. The approach is redolent of that notorious photograph of a statue factory in the 1970s USSR churning out identical Lenins, the product of an ornamental production line – and mass production in ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ was mastered to the point where it is now the main supplier of commodities to the capitalist world system. Contemporary Shanghai is in many ways the fusion of the two architectures that contemporary urbanists find most uncomfortable – the repetition and lack of any ‘street’ in high Modernism, and the imposingly monumental, obsessively ornamental approach of high Stalinism. It is Le Corbusier meets Lev Rudnev meets neoliberal bling, the Stalinist city gone high tech, its pinnacles and swags slathered in neon. It’s hard to think of it as even remotely ‘socialist’, it just throws communist aesthetics into its Postmodernist whirlpool like everything else.

Prefab neo-Stalinist high-rises, Shanghai

‘BETTER CITY, BETTER LIFE’

At the start of this book, we found at VDNKh, Moscow’s Exhibition of Economic Achievements, a blueprint for the Stalinist city, which would be organized as if it were one continuous Expo. The Shanghai Expo of 2010 had similar ambitions,11 and consciously presented itself as a compendium of potential future cities, advertised by a little blue creature called ‘Haibo’, grinning out from nouveau Socialist Realist ads all over the city, often accompanied by wholesome families. Its site extended across an area on the scale of a decent-sized industrial town, on both sides of the Huangpu, hence necessitating a Metro line to get from the Pudong side (the international pavilions, the bit in the magazines) to the Puxi side (the national and corporate pavilions); this trip comes free with your ticket. My friend suggested we meet outside Venezuela; the route there took me through Eastern Europe. I walked first past Bosnia, one of many retoolings of a basic shed design provided by the Expo authorities for free for those who can’t pay for their own architects. These decorated sheds were more fun the less seriously they took themselves. In the context of demonstrative, good-taste high architecture, there was a certain relief offered by the kitsch painted box housing the pavilion of ‘Europe’s Last Dictatorship’, Chinese ally and CIS state highest on the UN’s Human Development Index, Belarus. It looked inspired in some way by the Belarusian Jew Marc Chagall, with a childlike, warped-perspective cartoon of an old East European city, with its spires and palazzos. It seemed the most popular of the East European sheds for the Chinese tourists photographing it. Nearby were the generically arty pavilion of Poland – popular, because offering free bigos – the cheap-looking green glass dome of Romania, and the Lego squares of the Serbian pavilion, which apparently ‘derives specific code out of multitude’.

Venezuela, our meeting point, had far greater ambitions. Housed in a pavilion by Facundo Baudoin Teran, a dramatic but non-ingratiating sculptural creation, its clashing volumes centred on a steep staircase, in a manner which distantly recalls Melnikov’s similarly politically charged Soviet pavilion at the Paris Expo of 1925. The Bolivarian Republic’s pavilion is next to its comrade in Latin American Socialism, Cuba, but puts it completely in the shade – even within the limits of the free-shed genre, a hell of a lot more could have been done than their sad little red and blue box, which clearly showed the austere grip of the Raúl Castro regime. However, those of us who held out hope for twenty-first-century Socialism found a great deal to admire about the Venezuelan pavilion – in fact, its similarity to Melnikov and Rodchenko’s presence in Paris in 1925 or El Lissitzky’s in Cologne in 1928 is much more than an aesthetic matter. This was the only pavilion that seemed to have political ideas, ideas about the country it represented other than ‘Here we are, we have a dynamic economy and really nice food, please like us’.

The Pavilion of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Shanghai Expo

The pavilion made very clear that it took the official Expo slogan, ‘Better City, Better Life’, more seriously than do perhaps its originators, only expanding it out rather further, across ‘Mejor Mundo’. The theme of the pavilion is, quite simply, ‘Revolution’ – and bear in mind here that the last ‘revolution’ in China, in the late 1960s, is now held in official governmental opprobrium. Here, as so often with the Bolivarian Republic, they talk such a fantastic fight that if I judged the place purely on this pavilion, I’d probably emigrate there at once. It all sounded more than just a little pointed. ‘Everybody may get involved and take decisions in politics, economy and culture’; ‘a country where all are included’; and, great to hear during the apparent End of History, ‘a revolution makes everything move again’. Cut-out figures give testimonials on all the things the Bolivarian Revolution has done for them – stories of collective ownership, co-operatives, workers’ councils, of expropriation, of non-alienated labour, told by construction workers, teachers, slum youth. My friend points out that ‘nobody reads the signs on anything in the Expo’, so it is perhaps a little misjudged in its heavily textual approach. He does find one gentleman reading them with great intensity, and asks him in Mandarin: ‘So what do you think of all this talk of revolution?’ ‘It’s great – but it’d be a long story to tell you why’ was the response. 60,000 people were displaced from their homes to make way for the Expo.

Architecturally, too, it’s more rigorous than most, its pleasures and surprises discovered through exploration and circulation rather than in an instant hit. The pavilion is a series of rooms with canted stairs going off at angles from them, and on the ground floor, open to the air, there are several definitions of what Revolution might be, printed on cotton blinds. It is, respectively, Individual Revolution, Collective Revolution, World Revolution. The central part of the Venezuela pavilion is where the freebies are given out – here, it’s chocolate and coffee, and on the coffee tables are, in classic national-pavilion style, descriptions of the country’s cash crops; and, in far from classic national-pavilion style, descriptions of its class and historical relations, like the role of the sugar industry in the slave trade. The aspect of the Venezuelan pavilion where all of this suddenly seems to be too good to be true is at the back end, where you get a lovely view of a steelworks, one of the few non-adapted parts of what was once the industrial centre of China’s greatest industrial city. At the back of the pavilion are thousands of red, plastic flowers, with the following message: ‘If the climate were a bank, it would have been bailed out by now.’ True enough, but the Bolivarian Revolution’s reforms and massive poverty reduction programmes have been paid for by oil revenues.

It was extraordinary, though, to find a place, a building, which argues that better cities and better lives aren’t caused by throwing tens of thousands of people out of their homes, or by massive industrial exploitation. Finally, somebody seemed interested in a space that defined what socialism is, what it might mean and why you might want it, rather than one which interpreted it in terms of state power or historic heroism. That list of ‘revolutions’ is an inverse of Kołakowski’s negations, his list of what socialism ‘is not’ – here are a whole series of suggestions of what it might actually be. Whether it accurately describes conditions in Venezuela I could not possibly say, and I doubt it – but how rare, how exciting, to see the city described like this, so far from either ‘real socialism’ or ‘real capitalism’, or China’s current amalgam of both.

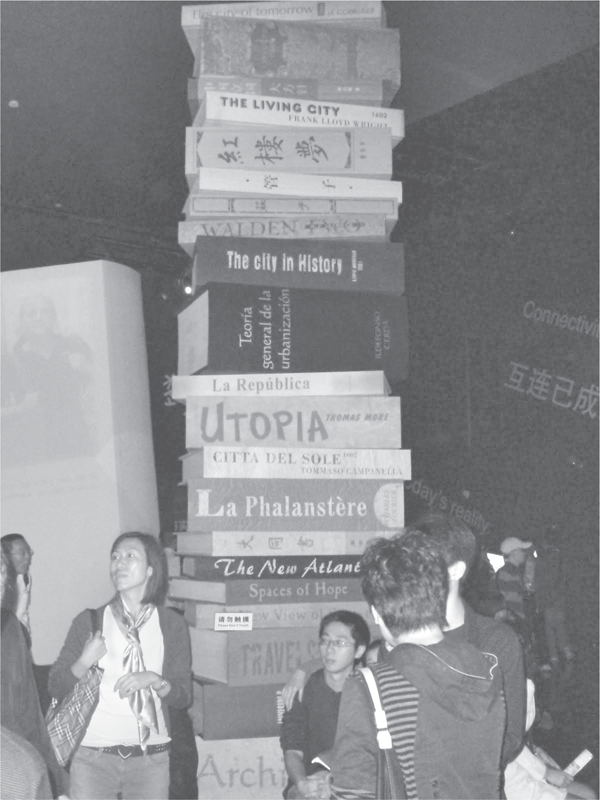

But for anyone expecting contemporary China to offer a viable vision of the future city, there was a pavilion dedicated to exactly that. The Urban Future Pavilion, heralded by a giant illuminated chimney-cum-thermometer, was housed in a converted power station. At its heart was a pile of giant books. In that stack you could find (though not read about) a litany of urban Utopias, many of those that Lenin had printed up and distributed in the first months of the Bolshevik government. Campanella, Plato, Francis Bacon, Charles Fourier, Thomas More – but also Lewis Mumford, Frank Lloyd Wright and, remarkably, the Marxist geographer David Harvey’s Spaces of Hope, sandwiched in just underneath The New Atlantis.

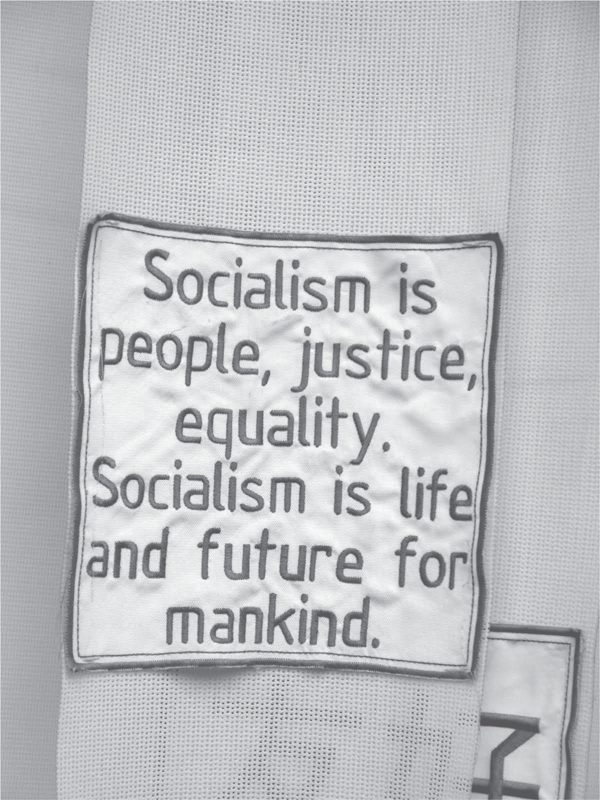

What Socialism Is

The explanation for this collection is found on the opposite wall: ‘In yesterday’s Utopia we find today’s reality.’ That is, they really were implying that contemporary Shanghai is the fulfilment of the hopes of generations, that they come to fruition here, in some manner; but this is not meant as a statement of complacency, far from it. In the room with the stack of books are huge images of various urban Utopias, from Archigram’s Walking City to the Ville Radieuse. There’s a wonderful moment in the exhibit on Le Corbusier when, taking the place in an exhibition in Berlin or Warsaw where you’d find the usual hand-wringing denunciation of all the evils he wreaked on the innocent slums, there’s the line: ‘Sadly, Le Corbusier’s ideas were never fully appreciated in his lifetime.’

The Library of Utopia, Shanghai Expo

Proposals are sometimes set against each other, but arbitrarily. On a screen, a ‘Space City’ is proposed by the Lifeboat Foundation, a Libertarian eschatological think tank. The organization was started after 9/11, and its aim is to preserve the human race, and the entirely unashamed telos of their plan for our survival is to colonize outer space. These really are people who think it’s easier – and more desirable – to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Next to it is Eco City, which essentially appears to propose a ‘sustainable’ industrial revolution. ‘We need to reinvent everything’ is a criterion of Eco City. Near to that is Water City, which proposes that we grow artificial gills. And ‘the views would be great’. The future cities in the Future pavilion rest on certain major assumptions, some more debatable than others. The first is that cities cannot remain as they are; the second is that they will face enormous challenges due to drastic global warming; and the third is that all ideas are of equal value, and that there is no need to set up an opposition between Space City and Eco City. Everything is equally valid – the barest hint of a contradiction and you suspect they’d start worrying they’d end up with a revolution on their hands.

So in the corner, not far away from the underwater aquatic city, was a model that summed up the sheer idleness of this, the idiocy of pretending that all contradictions can be resolved, that technical fixes rather than the conscious seizure of space can solve the mess we’re creating for ourselves. It’s a maquette of a gigantic energy-generating complex, and oil refineries go next to wind turbines go next to oil tankers go next to a cubic power station which goes next to pylons which goes next to serried cooling towers, just like those lining the charred landscape of the Yangtze river delta. There isn’t the slightest hint that this energy-generating complex in its lurid, apocalyptic, radioactive green might lead to the situation described so cheerfully in Water City. Evolution, presumably, will decide for itself. The socialist city, communally owned, democratically run, consciously created, made by its inhabitants, dedicated to their own enjoyment and development, is the missing option, the void around which all these idly apocalyptic speculations revolve. We found all sorts of clues to it, fragments of it, abortive or not-so-abortive attempts at it, but we never found this city in the ‘past’, looking around Eastern Europe. We don’t find it in the present, either, in the blare of China. It remains for the future to build it.