For much of the afternoon I waited for night to fall, hiding in one of the countless caves in the cliff, a little way uphill from the Valleuse de Vaucotte, clinging like a mussel to the sections of rock face revealed by the swell.

Soaked.

A strip of pebbles about a metre wide was drying out between the sea and the chalk wall, but occasionally bolder waves amused themselves by crashing against the rock and drenching the idiot hiding there with their spray. By way of recompense for my efforts, a compassionate God had offered me the most sumptuous of sunsets, just before I climbed the reddening valley towards Vaucottes.

I waited again before leaving the trees of the Bois des Hogues. Ten minutes. Long enough for the darkness to become more intense, and for my wet clothes to stiffen into an icy shroud.

Still free, but deep frozen.

Grey night. In the gloom, the Valleuse de Vaucottes began to look like a haunted valley. The thirty or so houses lost in the jungle of pines, hazel trees and oaks, seem to have been built after a competition by architects who had been put under a curse. Each villa rivalled the next in baroque invention. Swiss chalet roofs, Tyrolian bell-towers, English bow windows, Moorish façades. I checked that there were no cars about and then climbed up by the beach road. La Horsaine, the villa of Mona’s thesis supervisor, was hidden just past the crossing.

Martin Denain,

123 Chemin du Couchant

“You’ll find the keys under one of the bricks in the coping of the well,” Mona had told me on the phone. “Near the cart. The gardener who looks after the grounds puts it back when he leaves. Make yourself at home. I’ll join you as soon as I can.”

She had given me a virtual kiss and hung up. Without asking me any further questions, settling for the crazed account that I’d given her.

The cops are after me.

I need to hide.

You have to help me.

Mona was an amazing girl.

I found the iron key under the brick, the door opened, I took refuge behind the walls of La Horsaine.

Make yourself at home . . .

First a steaming shower. Then take stock. Tell Mona everything as soon as she gets there . . .

Before finding the bathroom, I wandered the maze of corridors, of tiny but innumerable rooms, staircases that connected three floors with plenty of half-landings. Apparently Martin Denain rarely came here. Not that the house wasn’t well maintained—far from it. A gardener mowed the lawn and pruned the rose bushes impeccably, and a housekeeper must have been paid in gold to get rid of the colonies of spiders and polish the panes of all the windows on the top floor.

A clean villa . . . and an empty one.

It was this contrast that I noticed when I was contorting myself in front of the huge mirror, gilded with gold leaf, to slide my wet jeans along my leg. My prosthesis tapped against the blue Delft tiles. I had a sense that the echo was spreading through the thousand and one rooms of the deserted villa, waking shadows and ghosts.

The jet of water drowned out the noises of the house. I stood on one leg in the shower.

A flamingo-pink toilet! I was sure Mona would have liked the expression.

With my eyes closed, I imagined the interior decoration of La Horsaine. Martin Denain had stuffed the house, that was the right word. He had stuffed it. Flowers on the mantelpiece and the bedheads. Artificial flowers. A basket of fruit on the kitchen table. Also artificial.

Shelves in the corridor with disorderly piles of paperbacks, magazines and games, which looked as if they had been forgotten there for decades.

As I let the hot water run over my naked skin, I reflected that this haunted-mansion décor seemed strange, almost unreal, as if drawn directly from the imagination of a novelist.

Like Mona’s personality . . .

A scientific researcher who had appeared out of nowhere.

Lively. Pretty. Original and shameless.

As if she had sprung from the head of a writer . . . or mine, the head of a bachelor in search of love.

I raised my head to let the jet of water thump against my skin.

No, on reflection, the second hypothesis didn’t stand up. Mona was insanely charming, but if I had to come up with a portrait of the ideal woman, she wasn’t the one I would have drawn.

And as if by enchantment, under the cascade of hot water, it was the washed-out face of Magali Verron that danced in front of my eyes.

Make yourself at home . . .

I attached my prosthesis and grabbed a cream-coloured dressing gown hanging on a hook. A Calvin Klein. I thought of calling Mona. I had to be cautious, the police would be bound to make the connection between her and me. I knew she wouldn’t blow my cover, but they might suspect her and follow her . . .

I banished those ideas from my head. I was still lost in the sequence of empty rooms, avoiding the reality that I had no strategy apart from running away. Not the slightest idea of how to prove my innocence, apart from gaining some time.

After half an hour I started finding my bearings in this baroque labyrinth. Apart from the basement, which was probably as huge as the villa itself, I had visited every room. In the drawing room, copper bottles were lined up on a cast-iron shelf.

Make yourself at home.

I poured myself a calvados, a Boulard. The label said “hors d’âge.”

Ageless, like the house.

As soon as I had taken a sip, a fire raged in my throat. My coughing bounced off the walls and back into the silence, then drifted away in hiccups towards the upper floors, like a fearful poltergeist disturbed by an intruder. However much I scoured my memory, going back to my childhood in La Courneuve and the succession of flats from T0 to T5 that I had lived in as the family grew, never in my life had I set foot in such a massive dwelling.

It scared me a bit.

I chose to wait for Mona in the room that I’d dubbed the eagle’s nest: it was the tallest room in the villa, built in a little tower that extended several metres beyond the roof and the chimney. From outside, I had seen that kitsch belfry for an architect’s folly, a snobbish substitute for a castle keep. I was mistaken! In that circular eagle’s nest, from every narrow window that looked like a romantic arrow-slit, the view of the Valleuse de Vaucottes, the beach and the sea was stunning.

A lighthouse!

Martin Denain had put his office there. A library at a low level all the way around the edge of the room, encircling two Voltaire armchairs and an oak table covered with thick purple velvet.

I waited there for a long time, between the sky and the sea, perhaps more than an hour. My eyelids were starting to close when Mona’s hands settled on my shoulders.

I hadn’t heard her come in, hadn’t heard her climb the stairs.

A fairy.

She was wearing the star of her wand over her heart.

“Thank you,” I said even before I kissed her.

For a long time.

We stayed there for a moment, enjoying the moon and its quivering twin who was drowning in the Channel.

“Tell me,” Mona said at last.

I didn’t hide anything from her. Piroz’s accusations. My escape. My conviction. I was the victim of a police stitch-up. After listening to me, she interrupted me once. Mona uttered three words, the only ones I wanted to hear.

“I believe you.”

I kissed her again. I untied her golden hair and let it flood through my fingers.

“Why? Why are you doing this for me?”

Her hand slipped between the open flaps of my dressing gown.

“Have a guess? The scent of the unknown? An insatiable greed for unusual stories? An intimate conviction that you wouldn’t hurt a fly . . .”

“Maybe not a fly. But a cop?”

She burst out laughing.

“If I tell you to call a lawyer and hand yourself over to the police tomorrow morning, will you do it?”

I held Mona tightly in my arms.

“No! I don’t want to fall into their trap. I want to work it all out myself.”

“Understand what?”

“Everything! There must be a logical solution. A key to open the door out of this hall of mirrors.”

While Mona unearthed the treasures of the kitchen storeroom—foie gras, confit de canard and a red Bergerac—I opened the “Magali Verron” file that I’d taken from Piroz’s desk.

I swore inwardly, the file contained nothing that I didn’t know already. Her detailed CV, which confirmed the information I had picked up on the internet, her childhood in Canada and then in the Val-de-Marne, the various schools she attended, her work for Bayer France. The other half of the file concerned her rape and murder. Complex medical reports listed each of her contusions, backed up by grim photographs, her blood group, her DNA, the details of her asphyxiation as the result of strangulation, which led to her death.

They were wrong, damn it all! By a few minutes, perhaps, but they were wrong.

I was sorry I hadn’t taken more time to go through the files on Piroz’s desk, to dig out the evidence on the Camus and Avril cases, clues other than the ones that some well-intentioned soul was drip-feeding me.

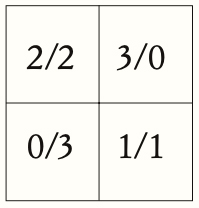

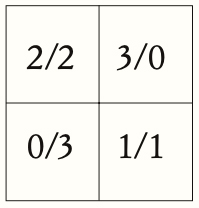

And also to find a clue to that series of figures Piroz was so interested in.

“Dinner is served!” Mona exclaimed, briefly dispelling the swarm of questions buzzing around in my head.

The thesis supervisor’s larder was more than a match for the menu at La Sirène. Mona had merely placed the block of foie gras on the table and heated up the bits of confit in a bain-marie.

“To Martin!” she said, raising her glass of Bergerac. “P@nshee pays him the equivalent of three trips around the world per year. We need to help him clear a bit of space at home.”

I clinked glasses, with a sad smile. My heart wasn’t in it.

“What are you going to do?” Mona asked.

“I don’t know.”

She spread the foie gras on a soft biscuit that she had found in a Tupperware container at the back of a cupboard.

“That’s a shame. They’re bound to catch you in the end. Then you’ll lose everything. Everything I found charming about you.” Her finger caressed the star that she wore pinned to her blouse. “That brilliant idea of hanging five dreams on your life. What . . . what are you going to do with those dreams?”

“I have no choice, Mona.”

She stared at me in silence for a long time, without taking the trouble to try and persuade me any further. The way you give up when faced with a stubborn child. Just as she was getting to her feet to pick up the saucepan behind her, the riff of my ringtone exploded into the room.

I picked it up.

“Salaoui?”

Piroz.

“Salaoui, don’t hang up. Don’t be an idiot. Hand yourself over, for fuck’s sake. You will have the right to a lawyer. You will have access to the case file. You will be able to defend yourself.”

I decided to go on listening, for less than fifteen seconds, without saying a word. The bastard was doubtless trying to locate me.

“Salaoui, you’ve messed up badly, but we’ll sort that out later. I’ve contacted the Saint Antoine Institute, all your colleagues, including the professionals, the psychotherapists. You’re not alone! We can help you. Don’t spoil your—”

Twenty-five seconds.

I hung up and turned my phone off, but my arm kept shaking. Gently, Mona rested her hand on mine. She was speaking even more gently than before, as if trying to tame me.

“In his own words, that cop was saying the same as you.”

Hand yourself in.

It would be so easy.

“They want to pin those murders on me, Mona. You heard him, with his shrinks and everything, they’re going to say I’m insane . . .”

She gripped my hand even harder. I went on.

“My prints can’t possibly be on that girl’s body! I didn’t touch her. The cops are lying. They’re cooking something up. Why doesn’t anyone know about Magali Verron’s death?”

“I know about it, Jamal. André Jozwiak knows about it, and he must have passed on the news to all the locals who come to his bar.”

“It wasn’t mentioned in the papers today.”

“It will be tomorrow . . . Jamal, why would the cops take the risk of inventing fake clues?”

“I don’t know, Mona. But if you want to play at riddles, if you want to ask questions, I’ve got boxes full of them! Why is someone going to the trouble of sending me those envelopes that tell me every detail of the Avril–Camus case? Why did Magali Verron take her life after copying Morgane Avril’s life? Why was that red cashmere scarf hanging in my path like a lantern?”

Mona pushed the block of foie gras around in front of her, almost untouched.

“O.K., you win. I’ll hand myself in.”

With a pair of stainless steel tongs she lifted out the two duck legs. Crimson. They made me think of two legs pulled from the body of a new-born baby that had been kept in a jar by a medical examiner. Even though I didn’t bat an eyelid, Mona noticed my disgust. She put a hand on my shoulder.

“I know you’re not a murderer! It hadn’t even crossed my mind. But someone believes it . . .”

The boiled meat made me feel like throwing up.

“Why me, for Christ’s sake?”

Mona took the time to think. I was touched by her expression of extreme concentration, her nostrils twitching, her eyelashes beating, her incisors biting her lower lip.

“Why you . . . That’s the right question, Jamal. Have you ever been to Yport? Before this week?”

“No.”

Her teeth released her lip, ready to bite me.

“I want the truth, Jamal! I’m not a cop. If you want me to help you, stop playing games.”

“No,” I said. “But . . . but nearly.”

“For Christ’s sake, Jamal, tell me what happened.”

“It was about ten years ago. I was chatting on the net with a girl I liked, I’d got off with her one weekend by the sea, she was heading for Étretat, but it was too expensive for me, so I booked a room in the suburb of l’Aiguille. Here, in Yport.”

“And?”

“And, when she saw that her prince charming had only one leg, the cow called off our honeymoon.”

“You hadn’t told her?”

“I’d forgotten to put a webcam under my desk . . .”

“O.K. And you’ve never set foot in Yport?”

“Not even one!”

Mona laughed. She topped up our Bergerac.

“Sorry. I’ll add your lousy date to the list of coincidences! And this week, what on earth brought you here? Wasn’t there anywhere else to prepare for your limping run on the glaciers?”

“A few months ago I did a survey on the phone. Something about tourism in Normandy. There was a lottery attached. I won a week in a hotel in Yport. Half pension included, and all the ups and downs of the Paris Basin as my playground . . . You can see why I didn’t have to think very long before burying myself away down here.”

“I get it.”

Mona drained her glass, walked to the window and then looked up at the tower whose shadow could be made out above the roof.

“We’ll have to be sensible, Jamal, I’m not going to be able to sleep here. The police will quickly make the connection between you and me. They’ll turn up at La Sirène with a warrant for your arrest tomorrow morning.”

I walked over and put my hand on her waist.

“We have time before tomorrow morning, don’t we?”

Her eye slid to the dark hairs on my torso, which contrasted with the pale down of my open dressing gown.

“Not here,” she murmured, staring at the eagle’s nest. “Up there . . .”