4

HEALING THE SOUL

The soul cannot thrive in the absence of a garden. If you don’t want paradise, you are not human; and if you are not human, you don’t have a soul.

THOMAS MOORE

The world over, since the dawn of human experience, we have used plants to replenish lost vital energy and to remove negative spiritual influences—the two principle causes of illness for traditional societies. Neither of these causes have much, if anything, to do with conventional medicine, of course. Instead, ill health or “dis-ease” is seen as one sign of an inner state of disequilibrium or disturbance, which, from a shamanic perspective, will usually arise from two forms of energetic imbalance:

Spirit Intrusion—where forces external to a person find their way into that individual’s energy system, either absorbed and assimilated from people around him or her, or, in some cases, introduced deliberately into it. These forces can result in physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual discomfort.

Soul Loss—where traumatic events, such as accidents, the loss of a family member, natural disasters, or the experience of abuse result in the severe loss of a person’s life force, which, again, creates imbalance and illness.

Both of these conditions can leave a person disinterested in life, with no desire or ability to engage in it, and may eventually lead to physical illness, as well as more psychospiritual problems, because the body as well as the life force is weakened. In this chapter, we look at some of the causes and symptoms of soul loss and spirit intrusion, as well as healing actions and preventive measures we can all take, with the support of our allies in nature.

SPIRIT INTRUSION

Behind the notion of spirit intrusion as a cause of illness is the understanding that human beings, like nature as a whole, are composed of energy, and this energy can become weakened in certain circumstances. When that happens, we become vulnerable, because our innate ability to resist negative or harmful influences is reduced. We then become increasingly susceptible to viruses, infections, accidents, emotional wounds, and mental distress, as well as saladera (bad luck), as our life force is weakened in this way.

These influences (some shamanic traditions call them essences) are around us every day in the form of energy emanations from other people and places, and the subtleties of mood carried on the atmosphere that surrounds us. All of these may affect our outlook and serenity; but under normal circumstances, when our life force is strong and in balance, they do not pose a major problem. When we are not feeling powerful, however, a field of energy greater than our own can easily overwhelm us.

Key among the reasons we lose personal power, and thereby become vulnerable to potentially damaging influences, is allowing ourselves to become disconnected from nature. The world of nature is our first source of power and will normally keep us safe by “recharging our batteries” so we feel strong.

“When a man or woman is out of balance with the natural world, the energies of other people are easily absorbed by their system and can start to attack them,” says Antoine Duvalier, a healer in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. “Because this energy is not natural to him, he does not benefit from a boost of power; it clogs his spirit instead and feeds from it, leaving him drained of power. In some cases, rivalry, jealousy, and the struggle for supremacy mean that a mo [bad energy in the form of a dead spirit] is deliberately sent after a person, with the intention of harming him.”

The latter situation—a deliberate energetic or psychic attack—sounds malicious and extreme, but is far more common than we might think. Malidoma Somé writes of it occurring among the Dagara of Burkina Faso, where magical darts, visible only to shamans, are left on the ground in the path of an enemy so they embed themselves in her spirit when she walks over them.1 Martin Prechtel writes of a similar practice among the people of Mexico and Guatemala.2 And even in Western culture, we know such things are possible. We talk of people “looking daggers at us,” and observe that “if looks could kill” we would be in trouble from those who mean us harm; these expressions are an unconscious acknowledgment of a spiritual fact: that looks and words—energy sent outward in symbolic form—have power. We know from personal experience that in arguments, for example, finger-pointing and unkind words can be physically felt. Who hasn’t been wounded by the words of another person? We feel them in our guts.

“In some ways,” says Michael Harner, “the concept of power intrusion is not too different from the Western medical concept of infection,” and, in fact, instances “occur most frequently in urban areas… people, without knowing it, possess the potentiality for harming others with eruptions of their personal power when they enter a state of emotional disequilibrium such as anger. When we speak of someone ‘radiating hostility’, it is almost a latent expression of the shamanic view.”3

Harner’s words can also be seen as a statement, not on power, but on the powerlessness that people feel in modern society, for if we truly had equality, equilibrium, and inner strength, and our souls were nourished by our world, there would be no need for the jealousy and frustration that leads to eruptions of anger. Spirit intrusions in the West are often energy projections (conscious or unconscious) from the disenfranchised urban man or woman, which are sent to take power from another in the hope of gaining a sense of order in a world that seems out of control. There is always something to envy in a world based on separation and the desire for material wealth, and where consumerism teaches people to want more and remain dissatisfied with what they have in their lives.

This competition, jealousy, or neediness is also at the root of intrusive illness in traditional societies. In many countries, envy is considered to be the cause of spirit intrusion. This may manifest as mal d’ojo (giving someone the evil eye), which is an infection of power in itself. But it may be more insidious: the sending of black magic toward someone, which causes them to become weak and lose whatever they have that has prompted the jealousy, even if the envious person gains nothing from it except the satisfaction of seeing his neighbor suffer.

To establish the cause of such a spirit-driven illness and find out who has sent it, an Andean shaman may conduct a divination with coca leaves or tobacco (see chapter 1). To remove it, she then needs to see it. Seeing is a practice of looking into the soul of a patient by becoming aware of the subtle emanations of energy that are given off by his physical body, much as you practiced it in the plant-gazing exercise in chapter 1. By doing this, the shaman becomes aware of energy that is out of resonance with the patient’s own, recognizing it because its appearance will be in some way unpleasant for her to look at. Sandra Ingerman puts it this way: to the shaman, “All illness has a spiritual identity. It will look like a fanged reptile, or an insect, or some dark, sludgy material. The illness will show itself in a form that is repulsive.”4

This does not mean, of course, that there is actually a reptile or insect within the patient; the shaman’s seeing, or perception of it in this way, is a diagnostic device that allows her to recognize the intrusive energy so she will not miss or mistake it. Having said that, it is interesting how such energies do take on consistent forms. Ingerman says, for example, that: “Some of the modern work being done with imagery and healing correlates with what shamans have always seen with illness. For example, when patients with cancer draw what their illness looks like, they often draw fanged reptiles and insects. People see on their own what classical shamans have always seen.”5

To test the truth of this, you have only to think back to a recent illness or localized pain of your own and ask yourself, “If I were to draw this, what would it look like?” People with skin irritations, for example, often describe their discomfort as “like an army of ants crawling over me,” and depict it as such, while those with stomach problems say their pain is like “a snake writhing in my guts.” It seems natural to use words and pictures like these to make our illness clear to others.

Once the shaman sees the intrusion, there are various ways he might deal with it in order to remove it. One of these is negotiation.

Eduardo Caldero, a curandero from Cusco, believes that spirit intrusions are not “evil” entities, but energies that are in themselves ambivalent to human beings. The person who sent them may have evil intent, but the energy he directs is often innocent, unaware that it is harming anyone through its presence, and simply trying to survive and live its own life.

These spirits are like a homeless person finding an empty house—the empty house being a person without power. The homeless spirit wants to stay there, of course, and make a home and be happy. It doesn’t intend its home any ill and has no desire to harm it—who would?! If you try to throw it back on the streets though, it will fight to stay where it is. That is only natural.

Caldero gets around this by offering the spirit a new home on the condition that it leaves the body of his patient.

This is taken very seriously. It is a contract we [the shaman and the intrusion] make between us and there is a ceremony that goes with it.

CLEANSING THE SOUL WITH PLANTS

This ceremony takes the form of a limpia—a cleansing—where the patient sits in a wooden chair below which is a bowl of smoking copal incense. This will purify the patient’s body and is relaxing to the intrusion, which is made drowsy by the smoke. As the limpia takes place, don Eduardo circles the patient, chanting, blowing tobacco smoke over her, and stroking her body with flowers (marigolds are often used). The tobacco smoke eases the passage of the intrusion, which is then caught by and rehoused in the flowers.

(Again and again we find that tobacco is used for cleansing negative energy. In the Amazon, tobacco—which is very different from that in your pack of cigarettes—is regarded as one of the most sacred plants. Wild tobacco is rolled up and lit and the smoke blown as a conduit of intention, the curandero engaging with the spirit of the plant as a focus for his energy, in a similar way to the North American Indian custom of using sage and sweetgrass in bundles or smudge sticks. It is never a mechanical action. In fact, when using tobacco, or any plant, to cleanse a space or a person, it is important to be in a state of 100 percent attention so you can see where the smoke goes and where it doesn’t go. If the smoke is drawn into the body, this is often regarded as a healthy sign, but if it is pushed away from the body, the shaman knows that there are negative or blocked energies present to be worked with.)

Sometimes an offerenda is also made in thanks for the healing—or in thanks to the intrusion for leaving—in which case a gift of some kind may be tied up with the flowers. The whole bundle is then taken into nature and buried, so the spirit will not be disturbed and others won’t be infected by it. Coastal shamans may take the flowers to the sea instead and cast them into the waves so the tide takes them away from the shore.

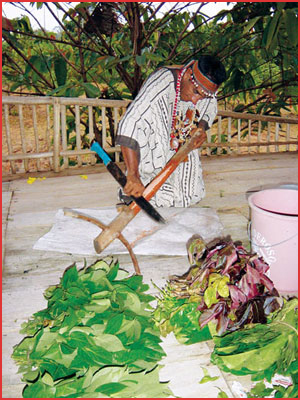

In the Amazon rainforest, the limpia uses not flowers but the leaves of the chacapa bush. (See a photo of chacapa leave on page 2 of the color insert.) These are approximately nine inches long and, when dried, are tied together to make a medicine tool that is used as a rattle during ceremonies. In a healing, the chacapa is rubbed and rattled over or near the patient’s body to capture or brush out the spirit intrusion. Once he has it in his chacapa, the shaman then blows through the leaves to disperse the intrusion into the rainforest where the spirits of the plants absorb and discharge its energy.

Another way of dealing with intrusions is through the use of cleansing leaf baths, a method practiced in Haiti as much as in Peru (also see chapter 6). Loulou Prince explains:

There are specific leaves, strong-smelling leaves, which help people who are under spiritual attack. I mix these leaves with rum and sea water to make a bath for the person, then I bathe her and I pray to the leaves to bless her. I sing songs for the spirits and the ancestors as well, and ask them to come help this person.

The rest of the bath that is left over, I put in a green calabash bowl or a bottle, and before the person goes to sleep at night, I have her rub her arms and legs with it. When that is done, no curse can work on that person and the evil is removed.

How this “evil” comes to infect a patient in the first place also has to do with jealousy. For example, Loulou was asked to perform a healing for a young child brought to him by a woman who had four children, two of whom had already died through the actions of spirits that came to her house at night to suck the life force from them. The woman was a market trader who had made a little money (a rare commodity in Haiti). Her neighbor was jealous and had sent spirits to kill her children.

I bathed the child to break the bad magic. Then I gave him leaves to make his blood bitter, so it would taste and smell bad to the spirits, and they would go away. After that, the child got better; he got fat and he grew. That boy is a young man now.

Intrusive spirits like these are believed, in Haiti, to make their home in the blood, which is why Loulou uses herbs to make the blood taste bitter and the body smell “strong.” This makes the host less appealing to the intrusion, which then finds its way from the body.

Fire baths are often used in these treatments as well, where kleren becomes the base for an herbal mix, which is set on fire and rubbed over the skin. The alcohol burns quickly and doesn’t hurt the patient, but it destroys the intrusion as it makes its way out of the body.

SIN EATING AND SPIRIT EXTRACTION

Dr. Stanley Krippner, professor of psychology at Saybrook Institute, and author of The Realms of Healing,6 concludes from his study of traditional healing that the power of our thoughts alone—whether positive or negative—has a profound effect on our health. When we accept the psychic emanations of others, pick up on their negativity and—crucially—when we allow their negativity to be absorbed within us so we find ourselves in agreement with our enemies, we open ourselves to illness.

This, too, is the basic philosophy of sin eating. In this old Celtic tradition, a sin is viewed as a weight or blemish on the soul that will keep it suffering while alive and Earthbound when the sinner dies. Sin is a powerful force toward illness while we are alive, but it is our knowledge that we have done wrong that really creates the weakness in our souls. The shame and guilt we carry is the spirit intrusion.

This notion of sin as intrusion is also known to Tuvan shamans, who refer to sin as buk—an illness that arises through our malicious actions toward another person or life form. The Tuvan shaman Christina Harle-Salvennenon7 gives the example of two young boys, patients of hers, who got carried away one day while they were playing and castrated a dog. When they came to their senses and realized what they had done, the boys ran home in shock. Both of them immediately became ill, one symptom of which was inflammation of their testicles. Recognizing the illness as buk, Christina demanded that the children tell her what they had done to cause its onset. The children, however, were overcome with guilt at their actions and refused to confess. Had they done so, it would have relieved the traumatic pressure in their bodies and given the shaman a direction for healing, but they simply could not. Both children died.

Spirit extraction (the removal of intrusions) was sometimes performed by the Celtic sin eater by stinging the patient’s body with nettles, paying particular attention to the “corners and angles”—backs of the knees, elbows, back of the neck, and belly—where intrusions tend to congeal. The nettle stings would heat the skin and draw the intrusion to the surface, in a similar way to the fire baths of Haiti. It could then be washed off in a cold bath containing soothing and cooling herbs such as chamomile, lavender, rose water, and mint.

Once this was done, the patient would also be reminded of the need to make reparation to the person he or she had sinned against, or else the patient’s guilt—and so the intrusion—might well return. One simple tradition that has survived as a way of making amends for minor sins, of course, is to send a bunch of flowers.a

HAITIAN EXTRACTION MEDICINE

Pakets kongo are one Haitian method of extraction. To look at, these are similar to mojo bags (see chapter 1), but more highly decorated and containing densely packed magical herbs that are specially blended to make them appealing to the spirits.

The herbal contents are a closely kept secret (though they do vary according to who creates the paket), but it is quite possible to make your own using local herbs once you understand the plant spirit principles behind this medicine tool. The secret is that each paket contains, in equal measure, plants that are (1) healing to the patient, and (2) attractive to the spirit intrusion. As the paket is used on the patient, therefore, intrusive energies are drawn into it, while the patient is soothed by the healing plants.

In Western cultures, soothing and purifying herbs for the patient might include the following:

The herbs that are attractive to spirits tend to be hot and spicy:

A selection of these is made (it is not necessary to use them all, which is what accounts for the variance in paket mixes), and the herbs are mixed with rum and Florida Water and allowed to dry. A roughly orange-sized ball of the mix is then placed in muslin and tied to make a bag. Around this a second skin of silk or satin is created, using colors and decorations such as sequins, feathers, lace, shells, and beads to reflect the qualities and preferences of specific protective spirits, and to energize the package with the ashe (power) of these spirits. The colors used correspond to the archetypal qualities we tend to be familiar with (see chapter 1, on mojo bags), so that red is for Ogoun, for example—the warrior spirit whose particular gift is power—while green is for Gran Bwa, the healing spirit of nature.

In Haiti, pakets are always made at night, usually beneath a full moon, and are dedicated to Simbi Makaya, the spirit of transformational magic. They are used in healing by passing the paket over the body of the patient, slowly, from head to toe, seven times. With each pass, the paket grows heavier as the herbs absorb intrusive energies while transferring healing to the patient. At the end of this, the paket is placed on the altar, which is a gateway between worlds and will discharge the intrusive energy back to the spiritual universe.

Used in this way, the power of each paket will last for seven years and is equally effective when used in a modern urban setting as when it is used in rural Haiti. Deirdre, a therapist from London who made a healing paket during one of our workshops later wrote, for example, that: “I had an amazing session today using the paket! It has powerful and different qualities—clearing and soothing. My clients also comment on it and remark about its powers.”

SOUL LOSS: THE FRACTURED SELF

Soul loss is in many ways the exact opposite of spirit intrusion. In the latter, some alien force is injected into our spirit-selves; in the former, it is a loss of spirit, a depletion of energy, that causes the illness.

In the West, we know something of soul loss, though we use different terms for it. We talk, for example, of “psychological dissociation” and “stress-related syndromes,” which arise as a result of traumatic, abusive, and hurtful experiences and may have a number of physical, mental, and emotional symptoms associated with them. In shamanic cultures, the same symptoms are diagnosed as a fracturing of the soul, or simply as soul loss, where an individual’s spirit, faced with pain, has split into many parts, some of which have taken refuge in the otherworld, away from the harshness of everyday life.

In some ways, then, soul loss can be seen as a positive act of psychological and emotional self-protection in the face of great pain and distress. When we are suffering, of course we do not want to be present, and so our souls and our psyches have found a way for us to take refuge in a world away from our trials.

When the life force remains lost, however, even when the threat to the self is over, this can be equally debilitating. The patient may find himself disconnected from life and out of balance, so that his emotions, thoughts, memories, bodily reactions, and spiritual ambitions are out of alignment with his own true nature and that of the wider world and spiritual universe. This is when problems really begin and when the healing intervention of the shaman is most needed.

Soul retrieval—the recapitulation of life force—is one of the shaman’s most effective healing practices for the restoration of this energy. To understand how it works, we need to remind ourselves of the shaman’s perspective on reality: that it is multidimensional and operates beyond the constraints of time and space. From this perspective, anything that has ever happened to anybody, anywhere, is still happening somewhere. That is, even if a traumatic event occurred ten or twenty years ago, for the person who suffered it, it is still happening now because, if undealt with, it still influences his life and comes out in his behavior, which is an adaptation to the effects of that twenty-year-old event and the soul loss that accompanied it.

For the shaman, there is no “past,” only one vast, awesome, ever-moving now. In his healing approach, he will therefore journey—outside of time and space—to the place where that energetic event is still happening for that individual and find and bring back the life force that is held there. Only when this has been done can the healing of the event and its consequences really begin.

The concept of soul loss, and the ceremonial retrieval of souls in this way, is found in many shamanic cultures. In the Tibetan Bon tradition, for example, one of the most important practices performed by shamans of the Sichen path is lalu (literally, “redeeming” or “buying back” the soul), and chilu, (“re-membering” the life energy). But, of course, this practice is far from restricted to Tibet. Joseph Campbell writes in The Masks of God, for example, that

Sickness, according to shamanic theory, can be caused… by the departure of the soul from the body and its imprisonment in one of the spirit regions: above, below, or beyond the rim of the world.

The Shaman’s clairvoyant vision must discover its lurking place. Then riding “on the sound of his drum,” he must sail away on the wings of trance to whatever spiritual realm may harbour the soul in question, and work swiftly his deed of rescue.9

Although the terminology is different, the idea of soul loss is also well known to psychology. In his memoirs, Jung recounts a fantasy in which his soul flew away from him; that is, his libido withdrew into his unconscious to carry on a secret life there. In this example, the libido is the life force, and the unconscious is the “land of the dead,” where unhappy souls go to hide.10

One of the few differences between shamanic healing and Western psychological systems, in fact, is that soul retrieval focuses on the return and integration of lost life force, rather than the original trauma itself, as psychotherapy tends to do. But soul retrieval and therapy do work very well together. The best combination seems to be: first, the recapitulation of life force, and then a therapeutic approach to support the patient through the process of understanding this newfound energy, the layers of meaning behind it, and the feelings and emotions that return with restored life force and are sometimes raw and uncomfortable.

This release and reintegration of previously subdued emotions can be fundamental to the whole healing process. Afterward, the patient can move forward in life without being anchored to the past and can live with new creativity and productivity.

LISTENING TO THE SOUL: HOW SOUL LOSS FEELS

In the shamanic worldview, power and health go hand in hand. If the body is power-full, there is no room for illness or disease, and no opportunity for these invasive forces to get in.

When we lose soul, however, a number of symptoms may result. These range from feeling “spaced out” (not really present, or a sense that you are observing life as an outsider rather than engaging with it fully) to pervasive life themes, such as fear, inability to trust other people, depression, and chronic illness.

In the sin-eating tradition also, soul is lost, weakened, or damaged through acts of betrayal—either those we have experienced ourselves (for example, when someone who purports to love us treats us cruelly) or those we have inflicted on others (for example, when we treat someone who loves us cruelly). In such circumstances, our shame or guilt becomes acidic, eroding our souls and causing us to lose spiritual integrity until our pent-up feelings are released through confession or action.

One of the sin-eating arts was “active listening,” a way of homing in on the words of patients in the knowledge that the soul speaks in symbols and poetry and will reveal the cause of its own loss or weakness, even if the patient does not consciously know. Expressions such as “I felt like my guts were ripped out” or “I gave her my life” were more than just idle remarks; they were the soul communicating its pain and telling the sin eater that its energy had been lost (and even, in the case of the former, where the energy had been lost from).

Other symbolic expressions suggesting that some deep, intuitive part of us is aware that soul loss has taken place might include the following:

A lot of these expressions have to do with love and emotional attachments. And, in fact, love can be a form of soul loss too, if we give ourselves so completely and love so deeply that we are no longer ourselves and see our lovers as our whole lives. Our hearts can also “break” when someone we love leaves us—literally break, in some cases. Scientists in Vienna have found, for example, that parts of the heart can enter a “sleeping” state when one suffers emotional pain. Doctors in Russia, Japan, and Brazil have apparently uncovered cases where the heart stops altogether in such circumstances, yet the patient goes on living.11

RETURNING THE SOUL THROUGH NATURE

Another way the soul can be lost is by dishonoring nature or ignoring our need for connection with it. Human beings, as parts of nature, need to feel their community with the great world soul. Our health, and invariably our feelings of well-being are rooted in this.

This is not a great mystery; it feels good to be at the edge of the sea, breathing in the fresh air, to experience the peace of a forest walk, or to sense our place in the scheme of things when we stand in awe looking out on the breathtaking view from a mountain. It is in our nature to be in nature and restoring our connection to it is vital if we wish to remain healthy and well.

In many countries, Japan among them, even today there are roadside shrines (and some in places like shopping malls) where people can rest, pay their respects to the natural world, and receive healing and replenishment from it. The Japanese festival of Obon, which takes place every August, is another way of honoring the ancestors and the spirits of nature. Also known as the Feast of Lanterns, it is a time when the spirits of the dead return to visit living relatives, just as the year is turning and nature begins to rest. Bon odori (folk dances) are held, offerings are left at nature shrines and outside people’s homes, and colorful lanterns are placed at gravesides. The event closes with toro nagashi, when candles are lit inside lanterns and they are set afloat on rivers so the spirits may go free. Another Japanese festival—this one in celebration of life—is Hanami, “flower viewing,” where families come together to sit beneath the trees and watch the cherry blossoms open.

In the modern West, we have few such ceremonies or sacred places left. Festivals such as May Day, originally a fertility ritual to welcome the coming of spring, and Midsummer Day, to celebrate the solstice, have lost much of their purpose and meaning. Our nature-inspired rituals have dwindled or disappeared, and our connection to nature is weakened. In turn, our souls, individually and collectively, have become weak, and despite our great wealth and “power,” many traditional societies regard us as the saddest people on Earth.

Returning the soul, as you might sense from our discussions so far, often involves the shaman reconnecting her patient to nature, so he is restored to balance and his spirit has a safe, strong, whole place to return to.

In Japan, one method is to accompany a patient (or advise her to go on her own) on a walk into nature to find and make contact with a particular tree that calls to her. She then sits down with her back to it and speaks to the tree of her problems and sorrows. If she listens closely, the spirit of the tree—the great gateway to nature—will counsel her on what to do, while at the same time taking and transforming her pains and giving her power and new spirit in return.

This is not unlike the observation of Doris Rivera Lenz (in chapter 1) that Peruvians will go into nature to shout out their problems to the gods. And in Tuva, too, we find that the patient is advised to take a similar walk and make an offering to a nature shrine, in return for which the spirits will bring back his soul. In all cases, the patient is deeply immersed in nature, at one with the trees and held in the peace of the forest, which is itself invigorating and restful.

In the Andes, soul retrieval is a similar but slightly different practice. Here, the shaman will accompany the patient to the physical location where soul was lost, in order to find and bring back its energy. There is always a physical location where trauma occurred, whether an accident black spot where a car crash took place or a home at the center of childhood abuse, and that is where the soul remains locked. The shaman is able to bring back the soul by negotiating for its release with the spirit of this place and by enticing the soul to return by singing to it of the joys that await back in the patient’s body, now that the trauma has ended.

In negotiating with the spirit of place, the shaman may also make an offerenda in exchange for the soul, or simply leave flowers.b If the spirits of nature are satisfied with the offering and reassured that the soul they are protecting will be treated well on its return—and if the soul itself feels loved and safe—it will be released to the patient straight away.

Lenz comments on this Andean practice as follows:

When a child falls suddenly, for example, its soul can leave its body and it may get ill. If this happens, an offering is made in the place of the fall, to heal the child.

There are many ways to “call the soul.” You can get hold of a piece of the child’s clothing and make a little doll and decorate it with flowers or whatever the child likes, and you call his soul in the place where the fright took place. You can also call up and use the energies of herbs, a dove’s nest, feathers, tobacco, coca, or whatever else is needed to help with this healing, but before any session, you must first ask permission from Pachamama, the spirit of the Earth.

If there is no fixed place where the problem began, then you go to the highest mountain or closest river and perform the ritual there.

There is another approach to soul retrieval that also works with flowers, common in countries as diverse as Mexico, Haiti, and Peru. In these traditions it is believed that the soul can sometimes be, not lost exactly, but so loosely attached that it is vibrating inside and outside the body at one and the same time. This can happen as a result of shock, when events that shake our worldviews and undermine all that we thought to be true can also set our spirits shaking. It is as if we have nothing left to hold on to, and all of our balance is gone. Shocks like these can lead to trauma, but if the soul is caught quickly enough it can be healed before deeper wounding occurs, by forcing it back into the body and stabilizing it there so that balance is restored.

Juan Navarro, Andean San Pedro maestro, standing with his mesa (altar).

Ayahuasca ceremony, led by Amazonian shaman, Javier Arevalo.

Leaves of the chacapa bush. These are dried and bound together

to create a natural rattle and healing tool, also known as a chacapa.

Amazonian shaman, Artidoro, preparing chullachaqui caspi by taking shavings from the bark. In the foreground are bundles of guayusa, pinon colorado, and ajo sacha.

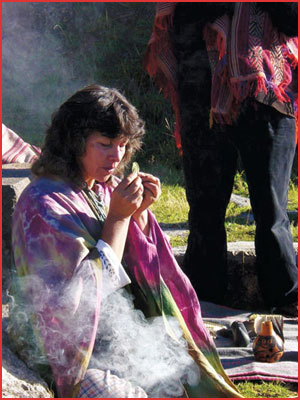

Curandera, Doris Rivera Lenz, divining with coca as she officiates in a ceremonial Andean offerenda.

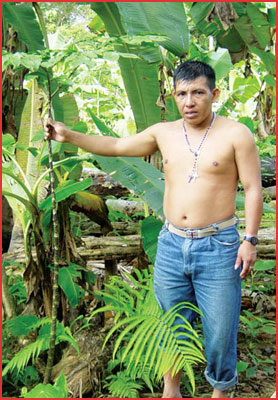

Artidoro, showing the floripondio flower, which grows in an ants’ nest and is used magically to generate work and stop people from being lazy.

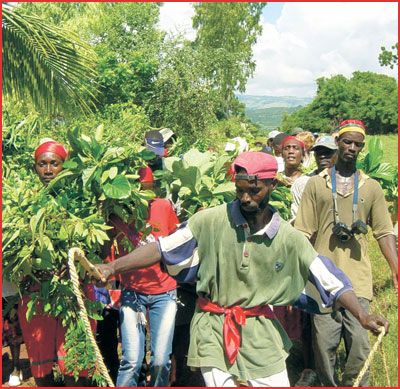

Leaf walk in Haiti to collect magical plants for healing baths. The procession is led by Houngan Babou, who cracks a whip to hold malevolent spirits at bay.

Ross Heaven (right), in ritual Vodou costume, opens a ceremony in Haiti. The “mist” behind the two figures is reckoned to be a Lwa (spirit) entering the circle.

Buseta (Eva), a female pusanga plant used to awaken passion in the opposite sex. Buseta (Adan), a male pusanga plant used by men for the same reasons. The man rubs the perfume “Adan” on his penis so women become aroused by him. The “Eva” is ground into powder and used by women for the same purpose.

Artidoro, collecting ingredients to make a ceremonial floral bath. He holds “rosa sisa” (marigolds) and a bottle of plant perfume.

Amazonian shaman, Wilson Montez, holds (left to right): mashushillo, floripondio, and buseta, plants that are all used in plant magic.

Wanga (charm) bottles hanging in a Haitian Makaya House (house of magic). The bottles contain plants and essences to attract good fortune to the person they are made for and remove evil magic or negative energies. Also note the snakes: in plant spirit magic, many shamans recognize a primal connection between serpents and plants and the affinity they have for each other.

The root of the jergon sacha tree, which is used in the snake medicine.

Javier stands next to a jergon sacha tree. The plant has the same markings as the bushmaster snake and is used as an antidote to snake bites.

Day breaks over the Amazon.

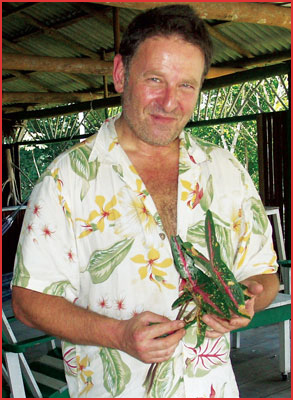

Howard Charing holding lengua del perro leaves. Lengua del perro (“dog’s tongue”) is so called because it resembles a dog’s tongue. By using it (in pusangas, etc.) it is said that a person will be made loyal and faithful.

One method of doing so is to swaddle the patient tightly in sheets or blankets so that the soul is pressed back into the body and held there.c Inside the blanket are placed flower petals, and these may also be sprinkled on top of and around the patient’s recumbent form. As the patient lies in her sweet-smelling cocoon of flowers that soothe the soul, the shaman will sing to her in lullabies and whispers of how beautiful the world is and how much she is loved and wanted by her people. Flower perfumes and essences may also be sprayed over her, their aromas anchoring her memory of the sweet words she is hearing and the prayers for her soul to the spirits of nature. Then she is left there for a while in the gentle heat of a rising sun, before the shaman unwraps her and welcomes her home into a new possibility of life: a rebirth through flowers.

Another method is that related by the Mexican medicine man, don Abraham, who speaks of the alta miza herb, which is used to gently beat the patient to “heal traumas, to make a regression… Alta miza grasps your spirit and moves you backward… until you reach the place which hurts. And then she confronts you with the pain. And she will heal the pain.”12

This is similar, in turn, to the Amazonian use of the chacapa to remove negative energies and restore spirit to a patient (as we saw earlier in this chapter). In both cases, it is the plants, directly, that offer the healing. It is interesting, as well, that alta miza is feverfew, which has long been respected for its properties of healing and purification, and which was widely planted in old England in the belief that it would purify the air and prevent the spread of plague. Gerard said of it that it “cleanseth, purgeth or scoureth, openeth, and fully performeth all that bitter things can do.”13 (Also recall Loulou Prince’s comment on bitter herbs as a means of purifying the blood and rebalancing energies.)

We know from the work of Backster and others (chapter 1) that plants have an affinity to human beings, that they know our pain, and that their intention is to love and to heal. Simply being close to them and their energy fields can be enough to call back the soul.

CASE STUDY: SOUL RETRIEVAL WITH PLANT SPIRITS

When lost soul parts are returned to a patient, old memories, sometimes long forgotten, may also resurface because the energy that held them, repressed due to the shock or trauma of the event, is now back. These memories can be part of the healing process and may lead to new revelations in their own right.

Howard relates an experience in which a message from the plants opened a gateway to a client’s hidden memories. This, in turn, led to the police reopening a forty-one-year-old murder case.

Following a soul retrieval session, Joanne called me in consternation, as certain memories were resurfacing and causing her discomfort. I took a shamanic journey for her [see chapter 1 for a discussion and exercises using this technique] and found myself in the town of Bradford in the north of England, on one of those old-fashioned streets. Around me was a strong scent of lavender, which I recognized as wood wax, a smell I hadn’t experienced in years. I breathed it in and my attention was drawn to a small nearby shop, which I entered. The source of this specific lavender scent was the polish on the wooden floor and cabinets. I was also struck by an aroma of herbs and spices.

In the shop was a thin man, but as I looked closer I could see that it was a woman disguised as a man. I followed her into the street, and outside I saw the child Joanne, whose hand was being held by her grandmother. Her grandmother had the manner of someone who was acting as a “look-out.”

All this time, I was carrying out a simultaneous narration of the journey, and when I returned to the here and now, Joanne was in a state of sadness and relief. She told me she knew my journey was true when I described the particular smell of that old-fashioned lavender-scented wax and the spices. She was aware that this event had happened—that her mother was the woman dressed as a man, and that she had gone to this shop to kill the owner.

A few days later, Joanne called to say that more memories of that time had resurfaced. She remembered the motive for the murder: the shopkeeper was a moneylender, and her mother was in serious debt to her. She also told me that she had gone to the police, who had reopened the case, based on what she had told them. Since her mother was terminally ill, however, and the case could not be effectively pursued, the police had decided not to press charges.

Joanne had gone to see her mother, who was close to death. Joanne said to her, “Mum, I know you did it, I know you murdered her.” Her mother could not speak, but she began to cry. Her secret was out. This was a true deathbed confession, which at the very last moment reconciled Joanne with her mother. Shortly after this, her mother went into a coma and died.

The whole story moved me. The beauty of it was that Joanne could at last put this gnawing, hidden secret to rest and move on in her life. I was also touched that her mother could finally unburden herself, at the moment before she died.

One of the magical qualities of this soul retrieval was how the spirit of lavender reached out and drew me to where I needed to be so this healing could take place.

As a concluding note, Joanne later sent some newspaper clippings about the murder, and I was shocked when I looked at the photographs of the shop—it was exactly as I had seen it in my journey.

Soul retrieval is not a one-off act; I see it as the start of a process that leads to the integration or union of life force. From that place, a person can move forward in her life with renewed vigor and passion.

PROTECTING OUR SOULS AGAINST LOSS

To receive initiation truly means to expand sideways into the glory of oaks, mountains, glaciers, horses, lions, grasses, waterfalls, deer. We need wilderness and extravagance. Whatever shuts a man away from [these things] will kill him.

ROBERT BLY

One action that every spiritual system advises in order to strengthen and protect the soul is time spent alone in nature. In some cultures this has been refined into a psychospiritual process known as the vision quest or the sitting out.

In essence it is simple. The student walks out into nature to find a place where he or she will not be disturbed for a period of time—whether for hours (often overnight, in the form of a night vigil) or days (four days is common)—and commits to staying there, no matter what.

The student enters this place with a question in mind: Who am I? Where should my life take me now? and so on. He takes with him a minimal amount of equipment from the material world—perhaps just a bottle of water—and will usually have received a cleansing (a sweat lodge ceremony or purification by smudging) and undertaken a fast before his pilgrimage begins.

The journey into nature is a walk of attention, so he allows the perfect vision-place to call him. When he finds it, he will smudge the area and form around himself a protective circle of stones. Then he will sit quietly, observing nature for the answer to his questions, in the knowledge that nature is alive and talking to us, and that if we only slow down to its pace, we will find all the answers we need.

There is no note taking and no other distracting of the self. The student simply sits and watches for omens. The shape of a cloud, the flight of a bird, the midnight visit of a fox, the wind in the trees, the smell of the pines—all of these can provide answers if we free our minds to receive them and let them speak to our souls.

For those of us raised in the hectic pace of Western culture, with all its distractions from the soul, our first response to this self-imposed regime of sitting in stillness is often irritation. We feel we need to be doing more than we are—instead of being who we are. Such irritation is healthy—it is the spirit freeing itself of toxins and the mind relaxing into a less artificial pace.

Then, after a time, the student enters a state of oneness with nature, his eyes open, and he sees the truth of who he is and what the world is truly about.

This is how Richard, one of Ross’s students, described his quest for vision:

I have recently completed my first Vision Quest and thought I would share some of my experiences and thoughts.

Firstly, I just seemed to “know” that it was going to happen on a certain date, although the weather either side of it was wet and cold (good old British weather!) and I was left wondering if it was the “right time.” I just had this inner feeling that it was right and to trust that it was going to happen, almost like I had made an appointment, and it was also involving so much more than just me, I had no choice but to now keep it.

I also found the fasting easier than expected. Now, I like my food, and have never gone without for very long, but it seemed easy and helped me to focus and plan for my quest.

Now, the place that I selected is on the top of a hill in the middle of the Mendips, quite remote for England, exposed to the weather but a fantastic location to sit and think, and it was my number one choice for the night.

I built my circle of stones and smudged myself and surroundings and settled down. After quite some time in wriggling around and settling myself, I started to slow myself down to the heartbeat of the planet. The one feeling that still remains with me is of my connection to Earth itself.

I find it quite hard to explain, but, from being still up there and watching the sun set in the West and knowing that I was going to see it rise in the East, I swear I could feel the Earth turning in space, with me sitting up there on my hill. The feelings of connection became very strong, and I could then see just how affected by the elements we are, the pull of the moon, the sunlight on our bodies, the rain and clouds, everything.

It was an amazing thing for someone who lives in a society that operates twenty-four hours a day with no changing seasonally or with nature anymore, removing ourselves further and further from the natural ways. It was very enlightening for me and I have taken that lesson with me, and I am now trying to be aware of the moon’s cycle and the seasons/weather and how it affects us all and how we feel.

I also got some messages from the wildlife around me that confirmed my questions that I came out with and when I came down from my hill at the end of the Quest, I felt connected once again with the pulse of the planet, the real clock who I have been removed from for so long. It was an amazing experience and very powerful for me and still is two weeks afterwards as I reflect.

There is no greater protection for the soul than sitting out in nature. Through the power of our experiences and realizations there, we see how trivial our petty human concerns are and how meaningless the jostling for status and control within our cities has become. And once we see this, we understand how we can make other choices, so we never put our souls at risk. Nature, the real world beyond the shadows, will teach us if we listen.

Teach us to care and not to care Teach us to sit still

T. S. ELIOT

The following exercises are an introduction to healing the soul.

Removing Intrusions in the Body

Removing Intrusions in the Body

Many shamanic traditions believe that all of our body parts have a specific spirit energy to them. And all of these individual spirits, together, are what make up the soul. The Sora Indians, for example, say that our life force is born in the heart and carried by the blood so it touches all parts of the body.d For the Wana of Celebes, our spirit energies are in the fontanel, the liver, and other internal organs. In Mongolia, each body part has its own ezhin or spiritual ruler, while, for the Cuna shamans of Panama, all body parts have a spirit. Thus, in all of these traditions, a physical ache or pain is a message from the soul, bringing us information about more deep-seated spiritual or emotional problems that we are carrying within us.

If you relax with your eyes closed and scan your body, it may be that you become aware of a limb, an organ, or another body part that calls for your attention. If so, journey into that part and hear the message behind this pain. What is it trying to tell you? What is the emotional content beneath the physical ache? This is the message from spirit about the way life has affected you. The spirit may have suggestions, as well, as to how you can change and avoid such pains.

This pain-energy is one form of spirit intrusion. In your journey, see it as an image-being, and note how it appears to you and what it has to say. This is useful information that will take you to a deeper level of understanding.

There will also be a time and a place in which that intrusive energy first entered your body. When and where was it? If you can, visit this place in physical reality (if not, journey to it using your active imagination) and, when there, ask that body part how you should remove this energy now that you have heard its healing message.

The spirit-being may have a request, perhaps a ritual or ceremony such as an offerenda. Or you may simply be told to use your breath to blow this energy into the Earth. Whatever the case for you, when you have performed this healing action, thank the intrusive energy for the information it has given you, and leave flowers at the spot you return it to.

When you reach your home again, take a warm bath with three spoonfuls of salt and one fresh lime chopped and added to it. In almost every culture of the world, salt and lime are used for cutting through magic and will remove any residual energies and pain from your body. If you have them, scatter marigold petals on the surface of the bath water as well, to invigorate your soul.

Returning Soul Energy

Returning Soul Energy

This is an exercise to take back energies you have lost and to find reconnection to the Earth.

Close your eyes and, in a quiet frame of mind, see yourself standing on the threshold of a great forest. When you step into it, you will find yourself in a passageway of trees, at the end of which is a source of light. This is the natural daylight of the otherworld. Walk toward it and enter the realm of nature.

Look around in your environment for a river, a stream, or other body of fresh, running water. Follow this back to its source, and there you will find your plant ally in the form of a spirit teacher. Ask that he or she guide you to the place where your soul parts, lost over the years through the impact of life on the spirit, are waiting to return to you.

When you meet these soul parts, they may appear as symbols, or as sensations, or in the form of children or younger aspects of yourself, and you may see the circumstances leading to their loss. Ask them about themselves, what has led them here, and what actions you can take to ensure that they are safe and happy and will not leave you again. If you are inspired to, promise that you will take these actions of self-healing and protection. Then, when you are ready, hug these soul parts to you and return, via the route you have just taken, back to ordinary awareness. With your arms folded across your chest, feel their energy flow into your body.

For the next few days, drink teas (morning and night) made of gentle herbs such as chamomile and hops, and watch for any unusual experiences, including reveries or dreams that have meaning for you. The energy you have just returned to yourself has its own memories and consciousness and will communicate these to you, giving you insights into yourself as you become more whole again. You may also wish to use a bila or dream pillow (see chapter 2) to amplify these messages from your soul.

Releasing the Soul Parts of Others

Releasing the Soul Parts of Others

We may also be holding on to the soul parts or energy of others even though they are no longer a part of our lives. This can happen, for instance, when a love affair ends: even though our lover has gone, it can still feel as if he or she is present and “haunting” our thoughts. We continue to behave in a way that would please (or hurt) our lover, even though we have nothing to prove anymore. It can also happen when someone we have been close to dies and it is if a part of ourselves has died with them so we are in permanent grief, and, again, our lives are not fully our own. In this way, we give others a part of our power and their energy still guides and controls us.

To explore this, relax and journey back to the forest (as in the preceding exercise) to meet with your spirit ally and ask that he or she show you the energy of others that is still a part of you. This may appear as an image of the person, and you may be surprised at the soul parts that are revealed as you meet this person again who, consciously, you thought you had long let go of.

Now that you see this energy, speak with your ally and ask to be shown the circumstances in which you feel drawn to take power from another person or to let them into your soul. What is the need in you that causes this? And how best can you control this tendency so you draw more beneficial energies from other sources?

When you are ready to return, gather these soul parts in the same way as before and come back to ordinary reality.

To return this energy that you have been holding on to, write down the name of the person this energy belongs to. Put as much concentration and intention as you can into the writing, so that energy as well as ink flows from your pen to the paper. When you are done, fold the paper with their name inward and write across it, “I release you,” then wrap it in flowers, tie it with ribbon, and take it into nature, where you can leave it at the base of a tree or cast it into flowing water. Once this is done, turn around and walk away without looking back.

The Quest for Vision

The Quest for Vision

Simply put, the vision quest is a method of strengthening the spirit through connection to the Earth and the natural order and flow of the universe. Begin it with a question in mind, something you will allow the spirit of nature to clarify for you. Any question you need an answer to is fine. Then commit to a time and a place in nature where you will undertake a vigil to find the answers you seek.

Arrive before sunset on day one and purify your space. Remain in this spot until sunset the next day. Don’t take anything with you that might distract you. Instead, pay careful attention to nature and your own internal processes as you sit quietly with an empty, open, and receptive mind. When it is time to go, clear your space, leaving it exactly as you found it, and thank the spirits for being with you, before you return to your home.

Reflect on the information you have received and watch your dreams for the next week or so, recording them in a dream journal (again, you may also wish to use a dream pillow to assist your dreaming process—see chapter 2). At the end of this time, make your notes.

What have you learned from your quest and how does your soul feel now?